Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine a self-developed tool for the evaluation of the impact of chronic periodontitis on quality of life (QoL) among 228 individually interviewed patients. All participants were clinically diagnosed with chronic periodontitis. A new original tool was designed and developed for the assessment of the disease impact on the individuals’ QoL. A pilot study was conducted for the assessment of face and content validity of the scale (initial version α = 0.882, final version α = 0.883). The tool contained nine items. The answers to every question were coded in a five-degree ranked scale: insignificant influence, weak influence, moderate influence, strong influence, extremely strong influence. The points of all answers were summed up to give a total score, which was used as a base for comprehensive assessment of the impact of periodontitis on QoL. The results were processed with SPSS v.13. This study revealed that the negative aspects were more prevalent among individuals with severe chronic periodontitis – 41% of the patients with severe chronic periodontitis reported strong influence of the disease and 29% of the patients reported extremely strong influence. The most prevalent domain of periodontitis’ influence was general health – 91.67%, followed by self-esteem and appearance, and the least affected function was speaking – 28.51%. The results stated clearly that the QoL of most patients with severe chronic periodontitis was worsened. The tool can be successfully utilized in practice, which will help dentists to easily evaluate the QoL of patients with periodontitis.

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of periodontal diseases is 5%–20% in the adult population. Periodontitis is the second largest oral health problem, affecting 10%–15% of the world's population.[Citation1] The most severe forms of periodontal disease significantly affect adults, which are 35–44 years of age with a prevalence of 19%. According to the American Academy of Periodontology, chronic periodontitis is more prevalent among adults; the amount of bone loss is compatible with local characteristics; subgingival calculus is a common finding; and the disease usually has slow to moderate progression.[Citation2,Citation3]

A number of studies show that periodontitis influence the quality of life (QoL) of patients. It affects negatively the physical, functional and psychological well-being, as well as the social activity of individuals.[Citation4–12] The more severe stages of periodontitis, associated with greater depth of the periodontal pockets, mobility and displacement of teeth, have a greater negative impact.[Citation2,Citation5] In this type of studies, different, already established tools for assessment of oral health-related quality of life, such as oral health impact profile (OHIP), general oral health assessment, oral impact of daily performance (OIDP) have been applied.[Citation6,Citation7,Citation11] Although they have been widely used through the years and have proved their worth in evaluation, it is difficult to determine, which of those tools is most effective.

In Bulgaria, no studies have been conducted so far on the QoL of patients with periodontitis. This fact, as well as the negative trends in the oral health conditions of Bulgarians, gave occasion to the authors to develop their own scale for evaluating the impact of periodontitis on QoL.

The aim of this study was to test a self-developed tool in order to evaluate the impact of chronic periodontitis on QoL among sample of individuals.

Subjects and methods

Patients

From November 2010 to February 2011, a cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the impact of chronic periodontitis on QoL. The sample was a group of patients, enrolled for care at the Department of Periodontology, Faculty of Dentistry, Plovdiv, Bulgaria and from various city dental surgeries. The selected patients by convenience were 228. The minimum sample size of patients was established based on power analysis for sample size calculation. Age <20 years was an exclusion criterion. Patients were between 20–80 years of age, from both genders. All of the patients were informed about the purpose of the research and gave their agreement to participate. All participants were clinically diagnosed with chronic periodontitis. The diagnosis was established through records of periodontal parameters (clinical attachment level and probing depth) and periapical radiographs. The degree of chronic periodontitis was classified as mild periodontitis, in which there was an attachment loss from 1 to 2 mm, moderate periodontitis, when the attachment loss was from 3 to 4 mm and severe periodontitis, when the attachment loss was 5 mm or more. Direct individual interviews were performed with all of the 228 patients.

Pilot study

A pilot research was conducted for the assessment of face and content validity of the scale. The internal and external consistency of the scale was tested. Thirty patients were interviewed (n = 30), by using a pilot version of the tool. The minimum sample size of 30 people has been established, based on a power analysis. After three months, the same patients were interviewed again with the same questionnaire for the purpose of testing the stability of the scale and its reliability during the whole period of research.[Citation13]

Data gathering

The tool originally designed in the pilot research [Citation13] was used. The design phase of the scale included defining its content (writing of items) and construction of its format (type of the scale). The initial version contained 11 items.

The above 11 items were grouped into the following 3 subscales:

Choice of food/nutrition, chewing, swallowing, talking; (Do you consider that the condition of your gums/teeth influences your choice of food; chewing of harder food; cause problems with swallowing; cause speaking difficulties).

Social relations, friends and family, professional life; (Do you consider that the condition of your gums/teeth has an influence on your self-esteem; your outlook; family life; professional and social contacts. Have you ever received negative comments from your friends and relatives in regards to your gums/teeth).

Overall health (Do you consider that the condition of your gums/teeth has an influence on your general health).

Coding of the answers for the influence of periodontitis on individual's QoL: answers to every question were coded in a five-degree ranked scale, depending on the degree of their influence.

point – insignificant influence;

points – weak influence;

points – moderate influence;

points – strong influence;

points – extremely strong influence.

The points of all answers were summed up to give a total score, which was used as a base for a comprehensive assessment of the impact of periodontitis on QoL. The maximum total score could not reach 45 points. In case of gathering 11 points – the periodontitis had an insignificant influence. When gathering up to 18 points – its impact on QoL was small. When the points were up to 27 – the influence was moderate. Gathering up to 33 points meant that the influence was strong and gathering over 34 points showed an extremely hard impact on the QoL. The overall rating (the sum of the points from the answers of all questions) varied from 0 (when the patient considered that the periodontitis did not have any influence) to 45.

Statistical processing

The results were processed statistically with the help of SPSS ver.13. First, the internal consistency was assessed with the coefficient of Cronbach (Cronbach's alpha). Second, the changing factors were researched by using the coefficients of Pearson (r) and Spearman–Brown (rsb). Afterwards in the research, the reliability of the result was checked by performing the test–retest analysis. The next step was to conduct an item analysis and to calculate the difficulty and discrimination power of all questions. The authors measured the difficulty as a proportion, in which the average value refers to the maximum value, as the lowest level of response was coded with ‘0’. The discrimination power was measured by the coefficient of linear correlation between the item rating and the overall unprocessed rating, from which the according item was excluded.

Results and discussion

Sample description

The study involved 228 patients distributed in 3 age groups (). The mean age of the participants was 50.35 ± 9.85. Male patients were 97 (42.54% ± 3.27%) and female patients were 131 (57.46% ± 3.27%) ().

Table 1. Characterization of the patients.

The patients with mild periodontitis were 34.2%, those with moderate chronic periodontitis were 24.6% and those with severe chronic periodontitis were 41.2%. When assessing the type of chronic periodontitis, according to the demographic variables, a statistically significant difference was found with regards to the age – 59% of those with severe chronic periodontitis were over 60 years old ().

Table 2. Assessment of the type of periodontitis, according to the age groups.

Reliability and validity

The pilot research [Citation13] confirmed the face and content validity of the instrument. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) value in the initial version of the pilot research was 0.882 and the Spearman–Brown coefficient (rsb) was 0.998. Two of the questions had to be excluded from the initial questionnaire.

After the second processing of the rest nine questions, the received results were as follows: the coefficient of Cronbach (α) was 0.883, the coefficient of Spearman–Brown (rsb) was 0.998, the value of the average inter item correlation coefficient was R = 0.507; the values for difficulty of questions were: min = 0.287, max = 0.757. Furthermore, the authors defined the discrimination power values as follows: the lowest was 0.524 and the highest was 0.809.[Citation13]

Assessing the impact of periodontitis on individual's QoL by using the self-developed tool

The evaluation of the impact of chronic periodontitis on QoL, according to the overall sum of points for each patient and the degree of the disease, is presented in .

Table 3. Assessment of the influence of periodontitis on the QoL of patients in the sample, based on the scale.

The results showed that the severe chronic periodontitis had strong (41%) and extremely strong (29%) negative impact on QoL.

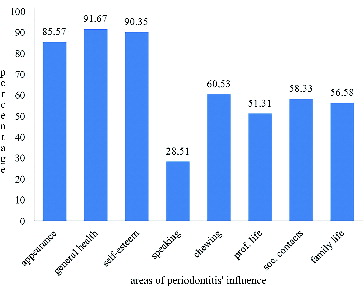

Through the study process, the areas of periodontitis’ influence with the highest impact on QoL have been researched ().

The most prevalent domain was general health – 91.67% followed by self-esteem and appearance and the least affected function was speaking – 28.51%.

The pilot study was the first research to use such an instrument in measuring the oral health related QoL in Bulgaria. The scale is a disease specific instrument that is precise, valid and reliable. The high value of the coefficient Cronbach's alpha in the present case, which is equal to 0.882, proved the reliability of the instrument.[Citation13] The question, related to the ‘swallowing problems’ and the one, related to the ‘negative comments by the closest friends and relatives’ occurred to be problematic during the research.[Citation13] Both questions were logically connected with previously asked questions. In the first case, the chewing of harder food and the process of swallowing were in a close relation. In the other question, the negative comments of the closest friends and relatives were directly related to family life and social contacts, which the patients had already commented. This was the logical ground on which these questions were eliminated from the second statistical processing of the data. Thus, the final version of the instrument consisted of nine questions.

This study, which included a much larger cohort, confirmed that the scale can be successfully utilized in practice. Based on the larger number of patients observed, more reliable and detailed results were obtained. For example, this study included greater number of women in the sample. This observation is a common finding in institutional samples that may be explained by cultural moorings that hinder the adoption of self-care practices in males.[Citation1]

The questions of the self-developed tool are formulated on the basis of literature analysis exploring various aspects of the periodontitis impact on QoL.[Citation2,Citation12,Citation14] The evaluation of the periodontitis influence on the QoL of patients was done by summing the number of points that bring the answer to each of the nine questions. Higher score means a stronger negative impact and, thus, deteriorated QoL. After calculating the total score points of each of the respondents, it was found that periodontitis had small or no effect on QoL only in 18% of the cases and in the remaining 82%, it had varying degrees of influence – strong and very strong in 32% of the respondents and moderate in 24% of them. This study on the impact of chronic periodontitis on the QoL revealed that the negative aspects were more prevalent among individuals with severe chronic periodontitis – 41% of the patients with severe chronic periodontitis reported strong influence of the disease and 29% reported extremely strong influence (). These results stated clearly that the QoL of most patients was worsened. The result coincided with the conclusions of other authors, who also demonstrated the negative impact of periodontitis on QoL but by using different (OHIP, OIDP) approaches than the current self-developed instrument.[Citation1,Citation2,Citation14]

The literature review showed that among patients with periodontitis, the functional limitations were problems with chewing and swallowing.[Citation7] Those authors reported that eating disorders usually occur in older patients.[Citation15–20] In this study, the results were different. The physical aspect of the periodontitis influence had the most profound impact on the researched contingent (appearance and general health), followed by the psychological discomfort – reduced self-esteem. The outcome can be explained by the dominance of women in the survey, who are more conscious about those factors. The least affected function was speaking. Large part of the patients had already recovered their orthopaedic defects in tooth rows and, therefore, did not report disturbance of speech function.

This study exhibited some limitations. The sample consisted of periodontally compromised patients, who sought treatment in specialized clinics, with no control group of healthy patients for the comparison of results. The participants in the study could have also had other oral cavity diseases (tooth loss, caries, malocclusions) that may have had negative effects on the quality of life.

Conclusions

The evaluation of QoL of patients with chronic periodontitis, based on the developed tool, showed that chronic periodontitis had an impact on the quality of life. The most prevalent negative aspects were found in patients with severe chronic periodontitis. The most strongly affected areas were the appearance, self-esteem and overall health of individuals. The scale can be successfully utilized in practice, which will help dentists to quickly and easily evaluate the QoL of patients with periodontitis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Palma P, Caetano P, Leite I. Impact of periodontal diseases on health related quality of life of users of the Brazilian Unified Health Systems. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:150357.

- Fereira Lopes M, Gusmao E. The impact of chronic periodontitis on quality of life in Brazilian subject. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2009;43(2):89–98.

- Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(1):1–6.

- Kiselova A, Krastev Z, Kolarov R. Oral medicine. Sofia: Angel Sapundzhiev EOOD; 2009.

- Saito A, Hosaka Y, Kikuchi M, et al. Effect of initial periodontal therapy on oral health-related quality of life in patients with periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2010;81(7):1001–1009.

- Wandera M, Astrom A, Engebretsen I. Peridontal status; tooth loss and self-reported periodontal problems effects on oral impacts on daily performances; OIDS in pregnant women in Uganda. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:89–93.

- Araujo AC, Gusmao ES, Batista JE. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life. Quintessence Int. 2010 41(6):111–118.

- Karlson E, Lymer U, Hakeberg M. Periodontitis from the patients perspective, a qualitative study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:23–30.

- Needleman I, McGrath C, Floyd P. Impact of oral health on the quality of periodontal patients. J Clin Periodontal. 2004;31(6):457–467.

- Sam NG, Leung K, Keung W. Oral health related quality of life and periodontal status. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(2):114–122.

- Drumond Santana T, Costa FO, Zenobio EG. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life for dentate diabetics. Cad Saude Pub. 2007;23(3):637–644.

- Gerritsen A, Finbarr PA, Witter D, et al. Tooth loss and oral health related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:126.

- Musurlieva N, Stoykova M, Boyadjiev D. Validation of a scale assessing the impact of periodontal diseases on patients quality of life in Bulgaria (pilot research). Braz Dent J. 2012;23(5):570–574.

- Caglayan F, Altun O, Miloglu O. Correlation between oral health related quality of life and oral disorders in a Turkish patient population. Med Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14(11):573–578.

- Shanbhag S, Dahiya M, Croucher R. The impact of periodontal therapy on oral health-related quality of life in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(8):725–735.

- Ritchie CS, Joshipura K, Hung HC. Nutrition as a mediator in the relation between oral and systematic disease: associations between specific measures of adult oral health and nutrition outcomes. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:291–300.

- Мillwood J, Heath MR. Food choice by older people. The use of semi-structured interviews with open and closed questions. Gerodontology. 2000;17:25–32.

- Sheiham A, Steele J, Marcenes W, et al. Prevalence of impacts of dental and oral disorders and their effects on eating among older people; a national survey in Great Britain. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001 28:195–203.

- Chambrone LA, Chambrone L. Tooth loss in well-maintained patients with chronic periodontitis during long-term supportive therapy in Brazil. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33(10):759–764.

- Irani FC, Wassall RR, Preshaw PM. Impact of periodontal status on oral health-related quality of life in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. J Dent. 2015;43(5):506–11.