ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study was to investigate doctors' and pharmacists' satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations in cardiology by applying the principles of the tetra-class analysis. The questionnaire was distributed among physicians and pharmacists to evaluate their satisfaction with important medicines' characteristics by classifying them in tetra-class groups. The principles of correspondence analysis were used as statistical methodology. The opinion of both cardiologists and pharmacists coincided in 8 out of the 28 elements of all generic medicines' and fixed-dose combinations' characteristics of satisfaction which were included in the questionnaire. The positive evaluation was more distinctive for doctors, whereas pharmacists were found to be slightly more negatively predisposed, which means that they have a higher risk of being dissatisfied. The tetra-class analysis was found to be suitable for the evaluation of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations in cardiology. It allowed classification of their characteristics, based on their importance for pharmacists and physicians. The results showed that the opinions of doctors and pharmacists differed. Doctors were more satisfied with generic medicines, whereas the satisfaction with fixed-dose combinations was high in both groups of health care specialists.

Introduction

Generic drugs are bioequivalent to a reference product which contains the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), and both are formulated in the same dosage form.[Citation1,Citation2] Generics appear on the market after the expiration of the 20-year-long patent protection of the API.[Citation3,Citation4] By this time, the primary manufacturer has already established trust in the product, by proving its quality, efficacy and safety.[Citation5,Citation6] He has also established a form of loyalty in the consumers (doctors, pharmacists and patients) towards the brand.[Citation7,Citation8] Oftentimes, manufacturers use combination therapies along with fixed doses which contain one or more substances with an expired patent in an attempt to prolong a product's market life and its market competitiveness.[Citation9] This necessitates the application of certain legislative measures and stimulation policies to help the prescribing and dispensing of generic medicines, in order for them to have a stable market share.[Citation10,Citation11] Generics play a certain role in the market – they create a competitive environment, and by having the same quality, efficacy and safety as the parent product, they force prices down, thus reducing the costs.[Citation12] Despite the different educational, legislative and economic measures applied to help generic prescription, many physicians and pharmacists still prefer prescribing and dispensing the original product.[Citation13]

In the cardiology practice, generic medicines and fixed-dose combination therapies are widespread, because of the complexity of illnesses and the presence of a multitude of symptoms and co-morbidities.[Citation14,Citation15] These medicines hold an important place in the therapeutic process, since they reduce treatment costs, provide an opportunity to positively influence more than one symptom or illness and improve patients' approval and compliance to therapy.[Citation16,Citation17] Nonetheless, there is an inconsistency in the way they are being prescribed and dispensed, which indicates that their advantages are either undervalued or their prescribing is influenced by past negative experiences, doubt or patient dissatisfaction.[Citation18]

Evaluation of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations is not conducted regularly, because of the complexity of opinions, as well as the presence of multiple factors, which influence the way generic medicines are perceived by the public or physicians.[Citation19] These factors can be linked to drugs' characteristics, patients, experience and opinion of doctors and pharmacists, as well as to the presence or absence of legislative measures, or to the marketing policy of the original molecule's manufacturer.[Citation20–24]

When evaluating such plethora of factors and their influence on satisfaction, a tetra-class analysis is used in many parts of health care, as well as in production and non-production sectors.[Citation25,Citation26] This inspired us to apply the tetra-class model towards the analysis of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations.

The purpose of the study was to investigate doctors' and pharmacists' satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations in cardiology, by applying the principles of the tetra-class analysis.

There were two main study questions, which were discussed in the article:

– Which characteristics were considered basic, positive, key or secondary by pharmacists and physicians?

– To what extent are physicians' opinions similar to or different from those of pharmacists?

The concept of applying a tetra-class analysis to evaluate satisfaction has been described in a number of studies.[Citation25–29] In the present study, we assumed that satisfaction is cognitive, emotionally defined and manifests itself after the drug has been prescribed and dispensed as an assessment or as an emotional reaction towards the product and its characteristics.[Citation30] These characteristics are classified into four subtypes, based on the tetra-class model ().[Citation28]

– “Basic characteristics” – contribute to the negative satisfaction, when they are evaluated negatively, since these characteristics are defining a product. When they are evaluated positively, their contribution towards the positive satisfaction is insubstantial.

– “Plus characteristics” – strongly contribute towards overall satisfaction, when evaluated positively. When evaluated negatively, these characteristics do not influence the dissatisfaction much.

– “Key characteristics” – strongly contribute towards dissatisfaction, regardless of assessment.

– “Secondary characteristics” – do not play a key role in satisfaction, regardless of assessment.

The distribution of elements is as follows – the upper right quadrant contains the key characteristics (strongly contribute towards dissatisfaction), the upper left quadrant contains plus characteristics (when evaluated positively, they strongly contribute towards satisfaction), the lower right quadrant contains the basic characteristics (when evaluated negatively, they contribute towards dissatisfaction) and the lower left quadrant contains the secondary characteristics (they do not influence satisfaction).

Subjects and methods

Domain of application

We chose cardiology as the sphere of focus for the study, because of the abundance of generic medicines from different therapeutic groups, as well as fixed-dose combination regimens.[Citation31,Citation32] Another reason for this choice was that a significant part of cardiology patients have a secondary (co-morbid) disease, which requires them to be on a combination therapy. Finally, satisfaction with generic medicines is an important subject to evaluate, since they have multiple characteristics, which can influence satisfaction either positively or negatively (both that of physicians and pharmacists).

Study cohort and questionnaire

In order to evaluate satisfaction, we sent a questionnaire to 50 cardiologists and 144 pharmacists. The cardiologists were interviewed by the Bulgarian cardiologists' association both online and in person, whereas pharmacists were interviewed at their workplace.

The questionnaire was discussed beforehand with the cardiologists' association and a pilot interview was undertaken with three cardiologists, after which the questionnaire was finalized. The question form used for pharmacists was evaluated by two practicing pharmacists, and a pilot interview was undertaken with five participants.

The questionnaire contained 12 questions, 7 of which were designed to evaluate satisfaction. Characteristics, which can influence satisfaction, are addressed in the questionnaire as follows:

Effectiveness of generic medicines and their interchangeability.

Safety of generic medicines.

Price and affordability to generic medicines.

Overall satisfaction with generic medicines.

Characteristics of fixed-dose combinations.

Patients' impression of generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations.

Question regarding overall satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations.

For each of the characteristics, important elements have been suggested. These elements have been discussed in the scientific literature,[Citation1–3,Citation6] as well as in a legislative context, and the interviewees were asked to evaluate their perception of them on a scale of 1–5, whereby the numbers correlate to the following statements, described in

Table 1. Evaluation scale meaning.

Statistical analysis

The answers were proceeded through correspondence analysis to determine the pharmacists' and cardiologists' classification of characteristics and their opinions to the presence of each element from the studied characteristics regarding satisfaction. The technique of the analysis is described elsewhere, and this study does not attempt to present it.[Citation25,Citation26] Following the work of Llosa,[Citation28] correspondence analysis was used for the categorization of characteristics of generics and fixed-dose combination. The performances of the different elements of the characteristics were first dichotomized. The dichotomization was made asymmetrically similar to Llosa's work. Answers 1 and 2 were regarded as ‘negative evaluation’, whereas answers 4 and 5 were regarded as ‘positive evaluation.’ Answer number 3 was used as a corrective in cases where there was no positive or negative opinion. The satisfaction scores were also regrouped into two modalities, named ‘positive score’ and ‘negative score.’ Correspondence analysis was then run on a cross-table of two variables – ‘positive’ and ‘negative.’ Each characteristic was attributed two factorial scores, which were the scores of correspondence of its two levels of evaluation (positive and negative) with satisfaction. A factorial chart then displayed each service with its two scores. The horizontal axis shows the scores of correspondence for the negative evaluation. It was interpreted as a contribution of the characteristics on satisfaction when their elements were positively evaluated. The vertical axis represents the contribution of the characteristics to satisfaction in case of positive evaluation of their elements. As a function of the position on the chart, the characteristics were classified as ‘basic’, ‘key’, ‘plus’ and ‘secondary.’ For each of the characteristics, a separate scatter graph was presented.

Results and discussion

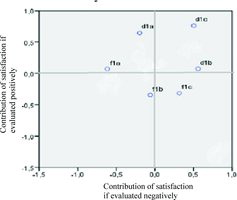

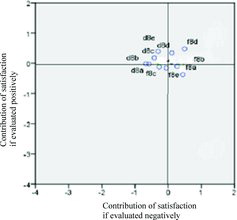

The first question, regarding the effectiveness, had a distribution of elements, described in and

Table 2. Categorization of elements regarding effectiveness.

Categorization of elements, linked with effectiveness, indicated that for doctors the key factors were: how identical the generic product is with the original product (containing the same international non-proprietary name) and how interchangeable they are. Therefore, a negative assessment of these elements will decrease the likelihood of prescribing generic medicines. The equivalent effectiveness was an expected characteristic; therefore, it was categorized as a positive element in both of the interviewed groups. According to pharmacists, the content of the generic, how identical the generic is with the original medicines or how interchangeable the drugs are, have no influence over the satisfaction. The prevalent positive assessments indicated that satisfaction towards all three elements of the effectiveness characteristic was high among both cardiologists and pharmacists, as well as that pharmacists were more inclined to dispense generic medicines.

When categorizing the elements linked to safety, we observed different opinions among pharmacists and doctors ( and ). For pharmacists, it was important that generics have the same safety and the same frequency of adverse effects, as the original product. Therefore, both elements can influence negatively the decision to substitute a drug with a generic, especially when both elements are deemed unsatisfactory. We observed that only 63.5% evaluated the safety positively, which was significantly lower than the other two elements. The possibility of applying a generic drug to the same treatment regime was insignificant for pharmacists, whereas doctors considered it as a positive element, which contributed to the overall satisfaction. A key element that strongly contributed towards dissatisfaction among doctors was the equal safety, whereas the frequency of adverse effects was not considered of primary importance. Satisfaction in the physicians' group was higher than that of the pharmacists' group.

Table 3. Categorization of elements regarding safety.

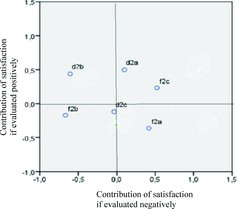

When categorizing the elements linked with affordability, the only elements which were found to impact doctors' opinion negatively and were considered important were the low costs and the access to all patients. For pharmacists, the opinions were not so uniform – they evaluated the quality and manufacturing costs highly as factors, contributing towards their satisfaction, but ultimately they were not of primary importance for them. A key element, which might strongly influence dissatisfaction, was the lack of access to all patients ( and ).

Table 4. Categorization of elements regarding affordability.

When categorizing the elements, linked with overall satisfaction, equal quality with original medicine was shown to be a plus element for pharmacists and physicians, and strongly contributed towards overall satisfaction, especially when evaluated positively. However, the evaluation was generally negative, especially in the pharmacists' group. The equal safety with original medicine was a secondary element and did not have a strong influence over satisfaction. The low price, income and patient compliance were either basic or key elements and they require attention, because a negative assessment of those elements may impact the decision to prescribe and dispense generics negatively ( and ).

Table 5. Categorization of the elements of overall satisfaction with generics.

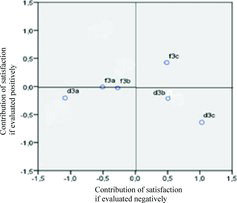

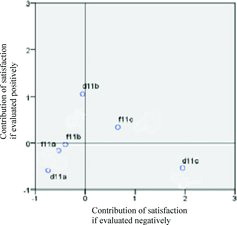

Categorization of the elements of fixed-dose combinations showed little to no difference between pharmacists and doctors. Pharmacists evaluated most of the elements as basic and key, apart from the element ‘to facilitate patients.’ A positive assessment of the basic and key elements might influence positively the practice of recommending combination therapies. On the other hand, doctors largely evaluated all the elements positively, categorizing them as both plus and secondary elements. This suggested that these elements were largely expected by them and they were pleased when they were present ( and ).

Table 6. Categorization of elements for fixed-dose combinations.

Patients' agreement was assessed through the perspective of doctors and pharmacists. Probably because of this, the elements were mainly categorized as either secondary or plus. Both pharmacists and physicians had equivalent results – secondary element, i.e. they were not important for the satisfaction of the individual patients, probably because they did not share the same opinion. Information was rated as a plus element. Health care specialists were more inclined to prescribe and dispense generics when patients had sufficient information about them. Doubts in effectiveness need to be identified and clarified, whether or not they are unfounded, since, as an element, they influence patients' decision to use generic medicines negatively ( and ).

Table 7. Categorization of elements linked to patients' agreement.

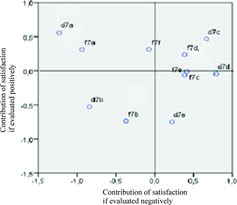

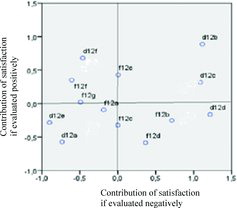

When categorizing the importance of the elements regarding medicines policy, the tendency of patients to use generic medicines was considered a secondary element by both pharmacists and physicians, which is logical, since they presume the generic medicines exist ( and ). Positively categorized elements were: reimbursement of the lowest cost and presence of generic medicines on the market. This indicated that they were important elements in the overall satisfaction. The lack of incentives for doctors and pharmacists was found to be a basic element, because every medicine policy needs to have such incentives. Nonetheless, the lack of those incentives has manifested itself in a negative assessment. The other elements were categorized as either basic or key and, when evaluated negatively, they can influence the satisfaction negatively.

Table 8. Categorization of elements regarding generic medicines policy.

In 8 out of the 28 elements of all characteristics of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations which were included in the questionnaire the opinion of both cardiologists and pharmacists coincided.

A positive evaluation was more characteristic for doctors, whereas pharmacists were slightly more negatively predisposed, which means that they have a higher risk of being dissatisfied. This was a surprising result, considering that pharmacists are more informed with the characteristics of both generic and original medicinal products. We could only assume this was due to the fact that pharmacists tend to be more careful in their judgement, since cardiology medicines need to be prescribed, therefore pharmacists do not have a big influence over utilization and prescription of generic medicines. This hypothesis was slightly confirmed by the similarity in opinion, regarding the benefits of combination products, as well as the importance of drug affordability, which are important factors for the success of a generic medicines policy.

The evaluation of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations in cardiology has not been done up to this moment in details.[Citation32] Its significance lies in the need to clarify the risk of dissatisfaction with effectiveness, safety, affordability and overall medicine policy in this domain. This will help to ensure that adequate measures are undertaken towards the goals of stabilizing the generic medicine policies.[Citation3,Citation33,Citation34]

During the last few decades, cardiology drugs have experienced an active growth in both numbers and variety of molecules, as well as generic equivalent therapeutic groups.[Citation14,Citation16,Citation19] Manufacturers should be familiar with the drug characteristics considered important by doctors and pharmacists when designing a marketing strategy for their distribution.[Citation32] The tetra-class analysis is a marketing analysis of satisfaction, which can successfully be applied in this field.

Conclusions

Тhe tetra-class analysis is suitable for the evaluation of satisfaction with generic medicines and fixed-dose combinations in cardiology. It allows classification of their characteristics based on the importance for pharmacists and physicians. Doctors and pharmacists turned out to have different opinions. Doctors were more satisfied with generic medicines, whereas the satisfaction with fixed-dose combinations was high in both groups of health care specialists.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- European Generic Medicines Association. Generic medicines: a cornerstone of EU healthcare policy. Brussels: EGA [cited 2015 Aug 26]. Available from: http://www.egagenerics.com/images/Website/003_EGA_FS_Generic_medicines_Web.pdf

- King DR, Kanavos Р. Encouraging the use of generic medicines: implications for transition economies. Croat Med J. 2002;43:462–469.

- Garattini L, Tediosi F. A comparative analysis of generic markets in five European countries. Health Policy. 2000;51:149–162.

- Simoens S. Sustainable provision of generic medicines in Europe [Internet]. Brussels: European Generic Medicines Association; 2013 [cited 2015 Nov 10]. Available from: http://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato3090824.pdf

- Perkins MB, Jensen PS, Jaccard J, et al. Applying theory-driven approaches to understanding and modifying clinicians' behavior: what do we know? Psychiatr Services. 2007;58:342–348.

- Swan J, Combs J. Product performance and consumer satisfaction: a new concept. J Mark. 1976;40:25–33.

- Cadotte ER, Turgeon N. Dissatisfiers and satisfiers: suggestions for consumer complaints and compliments. J Cons Satisf Dissatisf Compl Behav. 1988;1:74–79.

- Rust RT, Zahoric AJ. Customer satisfaction, customer retention, and market share. J Retail. 1993;2:193–215.

- Peikova L, Manova M, Georgieva S, et al. Enantiomers novelty protection and its influence on generic market: an example with escitalopram patent protection. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2013;27(4):4044–4047.

- Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Demand-side policies to encourage the use of generic medicines: an overview. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13:59–72.

- Lofgren H. Generic drugs: international trends and policy developments in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2004;27(1):39–48.

- Dylst P, Simoens S. Generic medicine pricing policies in Europe: current status and impact. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(3):471–481.

- Dunne S, Shannon B, Hannigan A, et al. Physician and pharmacist perceptions of generic medicines: what they think and how they differ? Health Policy. 2014;116:214–223.

- Finnegan PM, Gleason BL. Combination ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for hypertension. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003;37(6):886–889.

- Wald SD, Malcolm L, Joan KM, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 1999;122(3):290–300.

- Van Vark LC, Bertrand M, Akkerhuis K, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce mortality in hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors involving 158 998 patients. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(16):2088–2097.

- Dimopoulos K, Salukhe TV, Coats AJ, et al. Meta-analyses of mortality and morbidity effects of an angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with chronic heart failure already receiving an ACE inhibitor (alone or with a beta-blocker). Int J Cardiol. 2004;92(2):105–111.

- Mott DA, Richard CR. Exploring generic drug use behavior: the role of prescribers and pharmacists in the opportunity for generic drug use and generic substitution. Med Care. 2002;40(8):662–674.

- Kesselheim A, Misono A, Lee J, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2514–2526.

- Cadotte ER, Woodruff RB, Jenkins RL. Expectations and norms in models of consumer satisfaction. J Mark Res. 1987;24:305–314.

- Holsclaw SL, Olson KL, Hornak R, et al. Assessment of patient satisfaction with telephone and mail interventions provided by a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk reduction service. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11:403–409.

- Oparah AC, Kikanme LC. Consumer satisfaction with community pharmacies in Warri, Nigeria. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2006;2:499–511.

- Chandra A, Finlay JB, Paul DP 3rd. Overall outpatient satisfaction and its components: perceived changes at the Huntington VA Medical Center over five years. Hosp Top. 2006;84:33–36.

- Hayashi S, Hayase T, Ikegami N, et al. Comparison of viewpoints and awareness between patients with and without a “family pharmacy.” Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126:123–131.

- Clerfeuille F, Poubanne Y. Differences in the contributions of elements of service to satisfaction, commitment and consumer's share of purchase: a study from the tetra-class model. J Target Meas Anal Market. 2003;1:66–81.

- Clerfeuille F, Poubanne Y, Vakrilova M, et al. Evaluation of the consumer's satisfaction using the tetra-class model. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4(3):258–271.

- Bartikowski B, Llosa S. De la théorie du poids fluctuant des éléments dans la satisfaction à la mesure. Comparaison empirique de quatre méthodes, Actes de la Conférence de l'Association Française du Marketing [ The theory of the relative weight of the elements in satisfaction measurement. Empirical comparison of four methods. Issue from the Conference of French Marketing Association, IAE de Caen-Basse Normandie]. Deauville: IAE de Caen-Basse Normandie; 2001.

- Llosa S. L'analyse de la contribution des éléments du service à la satisfaction: un modèle tétra-classe [Analysis of the contribution of elements of services on satisfaction: a tetra-class model]. Décisions Market. 1997;10:81–88.

- Hayashi S, Hayase T, Mochizuki M, et al. Classification of pharmaceutical services from the viewpoint of patient satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2005;125:159–168.

- Garbarino E, Johnson MS. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J Mark. 1999;63:70–87.

- O'Riordan M. One pill to cure them all: single-drug polypharmacy in cardiovascular disease [Internet]. Hamilton, Ontario: Medscape; 2012 [cited 2014 Aug 5]. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/771801

- Figueiras MJ, Marcelino D, Cortes MA. People's views on the level of agreement of generic medicines for different illnesses. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(5):590–594.

- Heikkila R, Mantyselka P, Hartikainen-Herranen K, et al. Customers' and physicians' opinions of and experiences with generic substitution during the first year in Finland. Health Policy. 2007;82:366–374.

- Quintala C, Mendes P. Underuse of generic medicines in Portugal: an empirical study on the perceptions and attitudes of patients and pharmacists. Health Policy. 2012;104:61–68.