ABSTRACT

Bipolar affective disorder has higher frequency among women of reproductive age and can relapse both during pregnancy and immediately after childbirth. The presence of family history is one of the leading risk factors for bipolar affective disorder. A cross-sectional study was performed as part of a large naturalistic study. It included 81 women with pronounced symptoms of bipolar disorder who required hospitalization. The clinical method included comprehensive assessment of patients in the cohort, assessment of the severity of symptoms and the family history. The results showed that more than 50% of the women were at an average age of 25 years and experienced bipolar affective disorder mostly in the first and third trimester, whereas, in the puerperal period, the risk was highest in the first two weeks after childbirth. There was previous history of bipolar affective disorder in about 50% of the women. In 55.6% of the women, there was family history of bipolar affective disorder. The presence of previous history of bipolar affective disorder, first-degree family history and pregnancy at later age were shown to be risk factors for a new relapse during pregnancy and after childbirth. Clinical expression of manic–psychotic symptoms was more typical of the period of lactation than manic symptoms, which were associated rather with younger age and the period of pregnancy. In the studied cohort of patients, the risk of repeatability of affective episodes was significantly higher with each subsequent pregnancy.

Introduction

Bipolar affective disorder has a higher frequency among women of reproductive age and can relapse both during pregnancy and immediately after childbirth. The risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy and after giving birth is 50%.[Citation1] The risk is lower, around 40%, in women with recurrent depression. Significantly more frequent episodes of bipolar affective disorder type I and recurrent depression are observed after giving birth. Their occurrence in the puerperal period is within the first month after childbirth, with symptoms of mania or manic–psychotic symptoms and perinatal episodes equally common across the spectrum of mood disorder.[Citation2] Prior studies have shown that, in fact, one-quarter to one-half of the women who become pregnant and give birth for the first time and who have prior history of a mental disorder, have higher risk of experiencing a new episode during pregnancy and after giving birth.[Citation3]

The presence of family history is one of the leading risk factors for bipolar affective disorder.[Citation4] It has been shown that the heritability of bipolar disorder is about 44%–54% compared to perinatal depression (2%).[Citation5] The presence of genetic heterogeneity and variations of bipolar affective disorder is determined by various characteristics, such as age at onset, family history and existence of other affected family members.[Citation6] Molecular genetic studies can help to gain deeper insight; however, a specific disease-related gene has not been identified yet. The research has mostly focused on different chromosomal regions: 4р16, 12q23-q24, 16p13, 21q22 and Xq25-Q26; and in recent years, there has been interest in chromosome 18. Studies on candidate genes have focused on neurotransmitter systems; however, there are still no positive results.[Citation7] There is evidence that there are significant differences between schizophrenic disorders and bipolar disorder with respect to copy number variations (CNVs), in particular, for large deletions (41 Mb).[Citation8] An increase in the duplication of 16p11.2 and 1q21.1, and deletions of 3q29 has also been reported in bipolar disorder.[Citation9,Citation10] The authors conclude that, in bipolar affective disorder, the large CNVs, particularly 41 Mb deletions, have a smaller contribution than in schizophrenic disorder.[Citation8] Georgieva et al. [Citation10] also showed that de novo CNVs play a lesser role in bipolar affective disorder than in schizophrenia. Patients with a positive family history may also harbour de novo mutations.

The clinical expression of bipolar disorder is characterized mainly by hypomanic and manic symptoms. The clinical profile of women that develop mania includes reduced need for sleep, racing thoughts, increased self-esteem, uncontrolled behaviour, increased physical activity and restlessness, resulting in impaired function. Besides, the well-known clinical symptoms, episodes of worsening proceed with dysphoric mood and aggression or excessive increased activity as well as thoughtless actions and behaviour.[Citation2] An emphasis is placed on cycling and mixed profiles associated with females that occur very quickly and develop within 2–5 days and represent a diagnostic challenge.[Citation11] Within the mixed states, the most common clinical expressions, especially in the puerperal period, are dysphoric mania (subtype of mania) and agitated depression (they are not classified). Agitated depression occurs with marked restlessness, motor agitation and a strong internal tension, distraction, talkativeness, irritability and even risky behaviour.[Citation12]

The goal of research so far and of such that lies ahead is to assess risk factors to be examined in greater detail for predictors of occurrence of bipolar affective disorder in the context of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as to discover and develop modules for intervention and prevention development of mental illnesses occurring during pregnancy or after childbirth. The analysis of the majority of these problems is done using a variety of methods, such as prospective controlled studies, retrospective studies and case studies.

The aim of the present study was to objectify the clinical characteristics and analyse family history as a risk factor in women suffering from bipolar disorder during pregnancy and after birth. The study is part of a larger naturalistic study. It included retrospective and prospective evaluation of the demographic characteristics, clinical diagnosis and clinical profile as well as the family history of women with expressed symptoms of bipolar disorder, who required hospitalization. The diagnostic criteria were defined according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

Subjects and methods

Study cohort

A cross-sectional study was performed as part of a large naturalistic study. The clinical research included 81 female patients with bipolar affective disorder in the period of pregnancy and after childbirth, hospitalized at the Psychiatric Clinic of University Hospital ‘Aleksandrovska’ (Sofia, Bulgaria) in the period 2002–2014. The inclusion criteria were pregnancy or the period after childbirth with expressed severity of manic and mixed episodes (disrupted vital functions, risk of aggression and self-injurious behaviour) that had required hospitalization. The supervision and monitoring of risk groups of women during pregnancy and after childbirth were carried out with the help of a team of psychiatrists, gynaecologists and obstetricians.

Methodology

The following data were retrospectively collected: age at the time of pregnancy and childbirth, history of transient mental suffering, family history. The severity and the characteristics of the clinical symptoms were prospectively evaluated. The clinical method included comprehensive assessment of the patients in the study cohort, the severity of symptoms as well as the family history. Medical history data were collected from the available medical records and the psychiatrist and the diagnosis was confirmed by two specialists in psychiatry.

All patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. The study design was approved by the ethical committee at University Hospital UMBAL ‘Aleksandrovska’ (Sofia, Bulgaria).

Evaluation tools

For reporting the present symptomatology, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) was used. It is a short structured interview for major psychiatric disorders on axis I of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and ICD-10. The interview takes into account the validity and reproducibility of existing psychopathology. The English version 5.0.0 [Citation13] was used.

The distribution of the surveyed women based on age, clinical severity of symptoms and family history was rated with the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) – Item Group Checklist (IGC). It includes 40 groups of questions referring to disorders in the psychoses group, affective disorders and neurotic disorders in ICD-10. The clinical severity of symptoms was evaluated based on duration, frequency, degree of disturbance and distress. SCAN version 2 [Citation14] was used.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using statistical package SPSS 13.01. Descriptive statistics and variance analysis were done, with significance level of 0.05 and 95% statistical probability. The critical level of significance was α = 0.05. The null hypothesis was rejected when the P-value was less than α.

Results and discussion

Age, previous history and family history

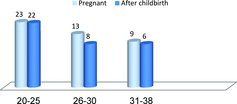

The average age of the 81 women with bipolar affective disorder during pregnancy and after childbirth included in the study cohort was 25 ± 2 years (minimum 20 years and maximum 38 years of age). More than one-half of the women were up to the age of 27 years at the time of examination. The predominant group of patients was those between 20 and 30 years of age (n = 66; 81.5%) and only one-fifth were aged 30–38 years (). It is noteworthy that the mental disorders at young age and during pregnancy are more frequent compared to those after childbirth. Contrary to expectations that women at a later age are at a greater risk of not being able to carry a full-term pregnancy in terms of their overall health, from the perspective of mental disorders, our results indicated that women with early pregnancy are more vulnerable to unlock mental illness. It is well known that there is a link between age and mental disorders in women at reproductive age, with 80.7% of mental disorders occurring particularly at a young age.[Citation15] Our results showed that the frequency of mood disorders at young age was in accordance with that reported by others. Moreover, in our study cohort (), there was almost even distribution of patients between the group of pregnant women (54.3%) and those in the period after childbirth (45.7%).

Table 1. Distribution of patients according to the period of occurrence of an episode of bipolar affective disorder.

The results from our analysis showed that the predominant number of women in the studied cohort experienced the illness during the first and third trimester of pregnancy, whereas, in the period after childbirth, the risk was mostly within the first 15 days to 3 months. Out of the patients in the study cohort, the majority of pregnant women (n = 34) unlocked an episode of mania or depression during the first and third trimester, whereas, the patients after childbirth (n = 16) showed higher risk within the first two weeks after childbirth (). This suggests that the third trimester and the period after childbirth (up to 15 days) could be considered as high risk in this study cohort.

Regarding the relationship between age and the existence of prior history of mental illness, the trend observed in the study cohort was generally positive. Pregnant women with bipolar disorder in the age group of 20–30 years were 81.5%, i.e. the majority of the patients. About 50% of the women aged up to 30 years had already experienced one or two episodes, whereas, 66.7% of the women aged between 30 and 38 years reported preceding history. Specifically, in the age range of 31–38 years, there was a statistically significant association (P = 0.0498) between age and the presence of prior mental illness. This result was not unexpected, since the beginning of bipolar affective disorder is at young age and most of the patients get an attack by the age of 30, with or without puerperium as a trigger factor. Moreover, the frequency of births in Bulgaria is highest between 20 and 30 years, which is why the association of bipolar affective disorder with the age factor is most common.[Citation16] Our results that women at later age with previous history of mental disorder who become pregnant have a higher risk of relapse of their mental disorder () support the suggestion that the period after childbirth is rather a trigger.

Table 2. Distribution of patients by age and previous history of psychiatric disorder.

Thus, the presence of previous history of mental illness is an important biological marker that should be assessed during pregnancy and childbirth. More than half of the monitored patients (n = 42; 53.1%) had prior history of mental disorder. Analysing the results in our cohort, in nearly half of the women who had no prior psychiatric history during pregnancy and after childbirth, these periods were associated with initial mental disorder. Previous episodes of affective disorder become a serious risk factor of a new relapse during pregnancy and after childbirth, and this risk appears to be significantly higher than at any other part of life. However, there is a connection between age, previous history of mental disorder and the presence of pregnancy or childbirth. These results support the idea that pregnancy and childbirth are not etiology, but are trigger factors.[Citation17] Our observations are in agreement with other surveys that explore the role of prior history of bipolar disorder as a significant risk factor and powerful predisposition to relapse of mental disorder during pregnancy and after childbirth.[Citation18] Most studies on the degree of risk of relapse during pregnancy or childbirth report that the post-partum period is a time of increased risk of exacerbation of mental illness, especially in women who have a pre-existing affective disorder. Women who have experienced previous episodes during the post-partum period are at higher risk of unlocking psychotic symptoms, especially if they have bipolar disorder type I.[Citation19–21]

Based on the analysis of the clinical profile, 56 of the 81 patients were identified to have principally manic episodes and the other 25 patients, mainly depressive/mixed episodes. Of the women with manic episodes (n = 56), 25 patients (25/81; 30.9%) experienced psychotic symptoms (). The results showed that the presence of manic–psychotic syndrome complex was more common in the period after childbirth (17/37; 45.9%) and manic symptoms were more common during pregnancy (28/36; 81.8%).

Table 3. Distribution of patients based on diagnosis.

The analysis of the data on the family history () showed that more than half of the patients had a family history of affective disorder (55.6%). Among the patients in the period after childbirth, more than half (54.1%) had a family history mainly based on first-degree relatives. In more than half of the pregnant patients (56.9%), the family history was mainly based on second-degree relatives. Most of the patients in the post-partum period had first-degree relatives (mother or sister) with psychiatric disorders, whereas, the pregnant patients reported grandmothers, aunts, uncles and first cousins with mental disorder.

Table 4. Presence of family history in different age groups of patients during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Based on the type of mental disorder in their family history, the largest group of patients were shown to have a family history of bipolar affective disorder (55.6%), followed by depression (24.1%) and schizoaffective disorder (9.2%). The distribution of the family history nearly repeated the distribution of diagnoses in the study group. Based on these observations, it is worth considering the group with bipolar disorder, where the percentage of heredity was about 50%, compared to the psychotic mood disorders, where it was about 10%. Comparing the heredity based on direct and indirect relations, the analysis showed that first-degree relatives prevailed especially in affective disorders. The results showed relative homogeneity of the clinical characteristics in terms of family history, mainly with affective disorders and the suffering mainly from affective disorder during the period after childbirth. Therefore, the presence of a family history of the affective disorders spectrum could be considered a significant predictor of symptomatic affective deterioration during the period after childbirth.

The analysis of the potential relationship between the age of the patients and the presence of a family history showed no statistically significant correlations with the young age of 20–30 years. Analysing the age range of 30–38 years with regard to the presence of heredity, it was found that late age of pregnancy was statistically significantly correlated with the presence of family history (P = 0.006). This correlation suggests that the presence of a family history of mental disorders in women who become pregnant and give birth after 31 years of age may be a risk factor for unlocking or relapse of mental disorder in the period after childbirth.

Thus, our results suggest that family history and late age could be considered significant risk factors for mental disorder during pregnancy (P < 0.01), but less likely during the post-partum period (). This suggestion is in agreement with the results reported by others.[Citation22] The genetic basis of mental disorders has been studied by many researchers and the accumulating evidence identifies family history as a certain biological marker and predisposition for psychosis in the post-partum period, especially for bipolar affective disorder. In 1996, Warner et al. [Citation23] established that the episodes of affective disorders in the post-partum period were found in 74% of Caucasian women who have family history of affective disorders and around 30% of them are with bipolar affective disorder. Of the biological factors evaluated in our study, the existence of a family history and previous history of mental illness could be considered risk factors for women during pregnancy or after childbirth. Initial periods of mental illness, as well as periods of relapse of an existing mental disorder, can often be related to pregnancy and childbirth. It could be speculated that the identified relationship between the late age of pregnancy and childbirth as well as preceding history of mental disorder is evidence of a correlation between biological markers and mental illness. This suggestion is further supported by the observed relationship between the existence of a family history, pregnancy and childbirth in late age and risk of psychiatric disorders in the period after childbirth.

Pathology and severity of expression

The present pathology and its severity of expression in the group of pregnant subjects and subjects after childbirth were assessed with a semi-structured interview and syndrome data from IGC. The analysis and assessment of symptoms were based on the frequency and association with the presence of pregnancy or the period after childbirth. For each group, an overall score was considered based on the number of component symptoms that were present, the severity of expression and impaired functioning (disability) associated with them. Correlations were identified between variables as well as association with some socio-demographic indicators, mainly with the age of the patients. After evaluation of all groups, it was identified that part of the complex of symptoms is significantly related to pregnancy and the period after childbirth. The observed clinical symptoms indicate some specificity and severity related to the presence of pregnancy or childbirth, and provide more information about the further appearance of mental disorders. It may be noted that the severity of expression in some syndrome complexes is significantly associated with age and the period of pregnancy or childbirth.

Symptoms of mania were found in 56 (69.1%) of the women in the cohort: in 36 patients during pregnancy and in 20 subjects in the period after childbirth; and 73% in total (n = 41) were aged 20–30 at the time of examination (). The well-defined manic symptoms primarily included reduced need for sleep, subjectively increased functioning, elevated mood, increased libido, a flood of thoughts, talkativeness, distraction, agitation, aggression, destructiveness and incoherent speech and thought.

Table 5. Presence of family history in different age groups of patients during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Regarding the severity of the manic syndrome complex and its expression in various age groups, the results showed that a total of 39 women (39/56; 69.6%) had reliable data on the presence of symptoms of mania. The most expressed symptoms were observed at a young age, up to 30 years. Regarding the severity of the symptoms, there was significant correlation between the degree of severity, young age (20–25 years) and the period of pregnancy or during the period after childbirth (P < 0.05). These results are in agreement with other reports.[Citation24,Citation25]

An important part of the manic syndrome complex is psychotic symptoms. In our study, the most common manic–psychotic symptoms were severe delusions and hallucinations, psychotic delusions mood, delusions of influence, etc. They were most prevalent in the post-puerperal period and were most clearly expressed in 17 women (20.9%), but not during pregnancy (P < 0.05). In the three age groups, in nearly all examined women in the period after childbirth, there was definite expression of manic–psychotic symptoms (). The analysis revealed association between severe expression of manic–psychotic symptoms and the period shortly (15 days) after childbirth (P = 0.035), suggesting that women in this period are predisposed to more severe clinical expression of bipolar affective disorder. This suggestion is in agreement with the data reported by Bergink et al.,[Citation18] who identified higher frequency of psychotic manic episodes in periods after childbirth.

Table 6. Distribution of manic–psychotic syndrome complex in patients after childbirth.

The expression of manic symptoms was most common in the first two weeks after childbirth (n = 16) and in the second and third trimester of pregnancy (n = 30). More than a third of the women who developed mania or hypomania after childbirth had symptoms in the last trimester of pregnancy. In our cohort during the studied period, about one-third of the clinical cases had psychotic symptoms within the mood disorder, with similar distribution of depressive–psychotic and manic–psychotic conditions. Clinical expressions other than manic were observed in 30.9% (n = 25) of the patients. Most of them were observed during hospitalization and included continuous anxiety highly expressed in the morning, depressed mood, pathological guiltiness, lowered self-esteem and clouded perceptions.

Based on the patients’ feedback data collected in a period of 12–24 months after discharge from hospital, it was established that the manic episodes relapse within 6 months after delivery. A small part of the patients experienced prodromal symptoms during pregnancy and especially at the end of the third trimester. In women with a previous history of bipolar affective disorder, the possibility of new episode during pregnancy and after childbirth could be considered to be increased by 50%, with episodes of depression being more prevalent in the post-partum period, within the first month after childbirth. Despite frequent depressive episodes observed after childbirth, it appears that this period is rather associated with bipolar affective disorder, whereas, the period immediately (3–7 days) after childbirth, mainly with depressive disorder.[Citation26] Based on previous studies, a connection of high levels of repeatability of affective episodes has been found with each subsequent pregnancy, as well as with the termination of the supportive mood stabilizer therapy.[Citation27]

Final remarks

The treatment requires consideration of many issues and careful assessment of benefit and risk. Cooperation between patient and doctor should be encouraged to continue during pregnancy and in the puerperal period. The medical plans should include not only patients and doctors, but also partners (where applicable and possible), obstetrician-gynaecologists, neonatologists and other institutions that provide care to these women. Mental disorders during pregnancy and childbirth are a dynamical process both from a biological and a psychosocial point of view. Women of childbearing age who suffer from mental illness are potential mothers. The number of women with mental disorders who become pregnant is growing worldwide.[Citation5,Citation28] Prior history of experienced longer episodes of illness, as well the need of discontinuation of medication during pregnancy, is a potential risk factor associated with the risk of worsening of the symptoms of the disease. Identification of all risk factors for relapse of mental illness during pregnancy and after childbirth allows individual risk assessment and opens opportunities for reducing this risk. Women with a history of mental illness who become pregnant need specific advice, assistance and support.

The accumulated clinical experience, observations and surveys can help to develop programmes for early intervention and psychological education that will provide monitoring, assistance and information to women with mental disorders who have an informed decision about planning a pregnancy. This will provide short- and long-term consultative support, in order to control mental illness during pregnancy and after childbirth, and also to control the medical treatment.

Women with serious mental illnesses and, in particular, with bipolar affective disorder, are considered high risk for complications during pregnancy and childbirth as well as after childbirth, which is associated both with the health problems of the mother and with neurodevelopmental problems in the child. Failures in implementation of antenatal care, non-compliance with medication, unhealthy lifestyles and inadequate health solutions can contribute to poor pregnancy outcome. Many women with bipolar disorder continue to maintain contact with psychiatric services while being pregnant.[Citation15,Citation29] Primary prevention aims at developing a network in the community, so that psychiatrists could improve the reproductive health outcomes for women with severe mental illness. Consultations should include discussions of issues with key stakeholders (parents, partners and relatives), evaluation of the environment to assess the status of services, literature review, individual and group meetings with pregnant women, contact with general practitioners and obstetrician-gynecologists. As a method of receiving social support, such women should include child care assistance at home, the so-called ‘Mothers’ groups’, telephone crisis intervention, voluntary support groups, etc.[Citation30] Three main elements could be outlined: early detection and monitoring of pregnancy, offering a reproductive choice (including treatment) and small teams working with pregnant patients (psychologist, social worker, doctor and gynaecologist). Specific programmes are implemented to ensure a supportive environment, assessment of the risk of pregnancy, early detection of pregnancy, monitoring during pregnancy, preparation for childbirth and planning the puerperal period. For example, Canadian psychotherapists have presented a model that integrates the therapy group for mothers with elements of cognitive behavioural therapy and psycho-education.[Citation31] The implementation of such programmes aims at significantly improving the conditions during pregnancy and childbirth and providing conditions for an adequate puerperal period in this high-risk group.

Thus, as pregnancy and childbirth are associated largely with the mental and physical health of the woman and are conditions that correlate significantly with the emergence and course of mental disorders, early diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders are vital. The availability of proven markers may provide a basis for clinicians to educate and treat women affected or identified as being at risk and to learn more about the prevention of further episodes or relapse of mental illness during pregnancy and childbirth.

Conclusions

The obtained results indicate a pathoplastic effect of pregnancy and childbirth on the course of bipolar affective disorder and its clinical expression. Within the studied cohort of patients, women at a younger age were shown to be more susceptible to unlocking bipolar affective disorder. The risk of occurrence or recurrence of bipolar affective disorder was shown to be high during pregnancy and after childbirth, especially in cases of first pregnancy at a later age, and to be associated with the presence of biological predictors such as family history, mostly first-degree, and previous history of mental illness. The affiliation and degree of severity of the particular symptom groups were specifically related to pregnancy and the period after childbirth, with manic–psychotic symptoms being more typical of the period after childbirth. The potentially harmful effects of mental illness during pregnancy and after childbirth on the welfare of women and the development of their child require an individual approach and assessment. The genetic predispositions and interactions between genes and the environment as well as the risk factors such as maternity, biological and behavioural accompanying expressions of severe mental illness are determining factors for increasing reproductive pathology in women. Reducing the risk in these vulnerable groups could be achieved through antepartum and post-partum interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Semple D, Smyth R. Reproductive psychiatry, sexual dysfunction, and sexuality. In: Semple D, Smyth R, editors. Oxford handbook psychiatry. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 461–487.

- Vladimirova R, Stoyanova V, Krastev S, et al. Affective disorders in perinatal period – clinical analysis. GP News. 2009;12(116):5–7. Bulgarian.

- Doyle K, Heron J, Berrisford G, et al. The management of bipolar disorder the perinatal period and risk factors for postpartum relapse. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(8):563–569.

- Milanova V. Affective disorders: interaction of genetic and psychosocial factors. Psychosomatic Med. 2006;14(1):137–158.

- Victorin A, Meltzer-Brody S, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Heritability of perinatal and genetic overlap with nonperinatal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):158–165.

- Lin P, McInnis M, Potash J, et al. Clinical correlates and familial aggregation of age at onset in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:240–246.

- Craddock N, Jones I. Genetics of bipolar disorder. J Med Genet. 1999;36:585–594.

- Jones I, Craddock N. Searching for the puerperal trigger: molecular genetic studies of bipolar affective puerperal psychosis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:115–128.

- Green EK, Rees E, Walters JTR, et al. Copy number variation in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:89–93.

- Georgieva В, Rees Е, Moran J, et al. De novo CNVs in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(24):6677–6683.

- Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, et al. Perinatal episode across the mood disorder spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:168–175.

- Vignera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1817–1824.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Weiller T, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I). The development and validation of a structured, diagnostic psychiatric interview. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;Suppl 20:22–33, 59.

- Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al. SCAN-Schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(6):589–593.

- Dennison C. Teenage pregnancy: an overview of the research evidence [Internet]. Wetherby: Health Development Agency (NHS); c2004 [ cited 2016 Feb 16]. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.wiredforhealth.gov.uk/PDF/bloopregPO.pdf.

- Vladimirova R. Psychiatric disorders during pregnancy and after birth, socio-demographic and clinical characteristics [dissertation]. Sofia: Medical University of Sofia; 2014.

- Robertson E, Jones I, Haque S, et al. Risk of puerperal and non-puerperal recurrence of illness following bipolar affective puerperal (post-partum) psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:258–259.

- Bergink V, Bouvy PF, Vervoort JS, et al. Prevention of postpartum psychosis and mania in women at high risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;101:452–458.

- Chaudron LH, Pies RW. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1284–1292.

- Carter D, Kostaras X. Psychiatric disorder in pregnancy. BC Med J. 2005;47(2):96–99.

- Colom F, Cruz N, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Postpartum bipolar episodes are not distinct from spontaneous episodes: implications for DSM-V. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:61–64.

- Mc Neil TF. A prospective study of postpartum psychosis in a high risk group: relationship to demographic and psychiatric history characteristics. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 1998;78:35–43.

- Warner R, Appleby L, Whitton A, et al. Demographic and obstetric risk factors for postnatal psychiatric morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;28:42–49.

- Freeman MP, Smith KW, Freeman SA, et al. Impact of reproductive events on the course of bipolar disorder in women. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:284–287.

- Vignera AC, Tondo L, Koukopolos AE, et al. Episodes of mood disorders in 2,252 pregnancies and postpartum periods. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1179–1195.

- Sharma V, Pope CJ. Pregnancy and bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1447–1455.

- Misri S, Kendrick K. Treatment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(8):489–498

- Rumans SE, Seeman MV. Women's mental health – a life-cycle approach. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Payne JL, MacKinnon DF, Mondimore FM, et al. Familial aggregation of postpartum mood symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:38–44.

- Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, et al. Perinatal risk of untreated during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):726–735.

- Galbally M, Blankley G, Power J, et al. Perinatal mental health services: what are they and why do we need them? Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21:165–170.