Abstract

The purpose of this study was to implement an educational programme for oral hygiene of children with autism. It involved 30 children with autism aged 6–11 years. For their training, Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) images for oral hygiene and tooth-brushing techniques were made. The oral hygiene level was assessed using the Silness & Löe Oral Hygiene Index. The children had poor oral hygiene due to hindered communication and motivation. The practical training of the children with autism included in the study lasted one year and was performed with the help of their parents. At the end of the one-year educational programme in oral hygiene, there was improvement in the oral hygiene habits of the children. The PECS images helped to improve the communication and the oral hygiene habits in the children with autism.

Introduction

Autism is one of the most severe neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood, known for over 50 years. Until recently, it was considered a rare anomaly of the cerebellum and the limbic system [Citation1, Citation2]. In 1943, one of the most influential American clinical psychiatrists of the 20th Century, Leo Kanner, known as the ‘father of child psychiatry’ at The Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic in Johns Hopkins Hospital, formulated symptoms that are characteristic of autism: seclusion, performing ordinary activities with compulsion, exceptional memory, echolalia, sensitivity to irritants and a limited range of interests [Citation3]. Maintaining oral hygiene in children with autism is a very serious problem due to the difficulties children face during interpersonal contact.

There are no accurate statistics on the incidence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It is spread throughout the world in families of all racial, ethnic and social groups. The possibility of its occurrence does not depend on family lifestyle, income and level of education [Citation1]. The World Health Organisation states that the global spread of ASD is 1:160 individuals [Citation4].

The aim of this study was to implement an oral hygiene training programme for children with autism. First, we determined the level of oral hygiene, duration and tooth brushing movements used in the examined children. During the programme, we studied the specifics of children’s behaviour at risk and reported the results of the programme at the 1st, 3rd, 6th and 12th months of the study. Comparisons with the results before the study showed that the programme helped to improve the children’s oral hygiene habits.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The study included 30 children with autism aged 6–11 years attending the Édouard Séguin Special Needs School in Sofia (Bulgaria). Most children were non-verbal and only three of them had minimal communication capabilities with limited vocabulary of 10–20 words.

Ethics statement

Informed consent forms were signed by the children’s parents/legal guardians. The study was approved by the Ethics Commission for Research at the Medical University of Sofia (KENIUMUS).

Oral hygiene training

A 1-year oral hygiene training programme was applied. The programme was based on a picture system showing the sequence of actions involved in maintaining oral hygiene. The level of oral hygiene was assessed through the Silness & Löe index [Citation5]. Children were given the opportunity to demonstrate the way they performed their oral hygiene, taking into account the state, time and type of toothbrushing movements used.

To educate the children in the principles of oral hygiene, we used a picture system for non-verbal communication Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) for a boy/girl, due to the fact that most children were non-verbal. For this purpose, pictures showing the daily routine of the child were drawn, arranged in a strict order representing the sequence of actions involved in tooth brushing ().

In the oral hygiene education programme, the autistic children received instructions by the dentist but their parents were also involved. The programme included the help of the parents, who received training about the purpose of the oral hygiene programme and their role in it. The parents were instructed to work with the child at home very patiently. Individual work at home provides the opportunity for the child to learn and perceive faster. It was explained that the introduction of knowledge has to be done very slowly, step by step, with self-care and special work to memorize the events that happen during the day, as well as to consolidate the order of actions in maintaining oral hygiene.

Additional materials were also used. These included motivational toys, cartoons and slides, colour posters, a set of pictures for each child, and written instructions for parents to follow the scheme at home.

The tell–show–do technique was used during the education. Since autistic children learn very well by imitation, the ‘Just Like Me’ technique was also applied, as parents, brothers, sisters or animated characters show how they brush their teeth. An additional physical stimulus was used in the children's education with the child's hands directed by the parent/family member to perform a certain action. Every successful stage was encouraged with praise. For successful results, children must constantly be praised for the slightest success. The more generous the praise, the greater the likelihood of the child performing the action. Smiles were a compulsory element of the non-verbal way of encouraging the child. As the training progressed, physical assistance, visual incentives and verbal commands were gradually withdrawn, and an attempt was made to teach the child to use dental floss fixed to a holder. Pictures were provided to help follow the instructions.

The final goal of the training was for each child to be able to complete the entire series of oral hygiene activities when he/she received the ‘Brush your teeth’ instruction.

The method of visual pedagogy was also used through PECS, respecting the principles of graduation, support and positive emotion.

Statistical analysis

Mean values and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for each of the eight visits. The nonparametric tests of Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney were also used. The results were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results and discussion

The oral hygiene assessment performed using the Silness & Löe oral-hygiene index (OHI) [Citation5] showed that among the children included in this study, there were no children with good oral hygiene. The children with poor oral hygiene predominated (93.3%) and only a few children had fairly good oral hygiene (6.7%). This fact is very indicative of the enormous difficulties these children and their parents have in implementing oral hygiene care due to the specificity of the neuro-mental disorder.

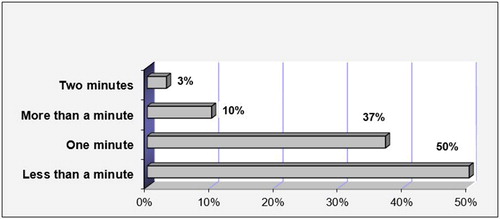

The duration of the oral hygiene in children with autism is presented in . The results showed that half of the children brushed their teeth for less than a minute and the rest, within the range of one to two minutes. This might be due to the hyperactivity of part of the children, the difficulties in placing a brush and toothpaste in the mouth caused by the increased sensitivity of the face and oral cavity, and refusal to perform oral hygiene.

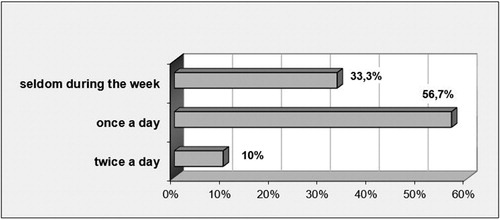

The oral hygiene habits of the children with autism included in this study are presented in . More than half of the children brushed their teeth once a day, others did it rarely during the week, and a small part of them maintained their oral hygiene twice a day. These data showed that the frequency of oral hygiene was at an unsatisfactory level, which once again indicates the difficulties the parents and the specialists working with these children have in building useful skills and habits.

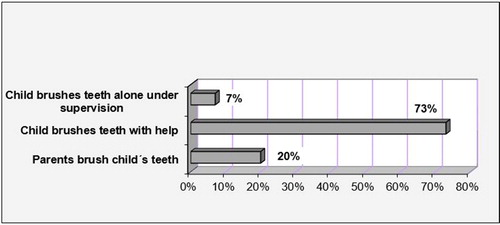

The ways to perform oral hygiene in children with autism are shown in . The data showed that most children brushed their teeth with someone else's help. In other cases, the parents performed the oral hygiene care, while some of the children performed their oral hygiene independently, but under supervision by the parents or a family member. This requires active work on building independence in performing oral care, which will make the children less reliant on help in their daily routine.

The observation of the tooth brushing techniques in children with autism showed, that the children used horizontal (83%) and circular (17%) movements. This requires active work to train and motivate the children to form appropriate skills for maintenance of oral hygiene.

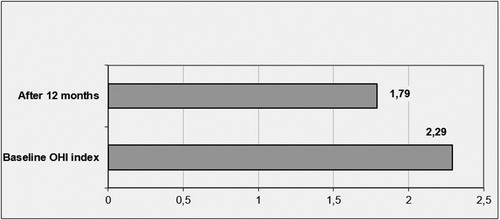

For the one-year study period, the oral hygiene status showed statistically significant improvement compared to the baseline OHI (). One week after the first training, there was a slight decrease in the OHI value, but the difference was not statistically significant. This can be explained by the fact that children become bored of the oral hygiene procedure very quickly, and they also experience difficulties in properly following the instructions of the parents, who are the main trainers in this process.

Table 1. оHI of children with autism during the oral hygiene educational programme.

Advancing through the subsequent observation periods, the children showed a slow trend towards improvement of the oral hygiene. This trend persisted until the end of the programme, although there were no statistically significant differences between the index values at any two successive points in time. However, when comparing with the baseline oral hygiene status, we observed improvement as early as the third month, and this effect was statistically significant. Further, the statistical analysis showed that the oral hygiene index was significantly improved at the ninth and the twelfth months () of the programme as compared to the baseline status, too.

Figure 5. Comparison between the state of oral hygiene at the beginning and at the end of the one-year training programme.

Overall, the obtained results may be considered satisfactory. During the training and observation period, a number of characteristics of the children's behaviour which could explain the obtained results were taken into account. Most of the children have a moderate level of function and needed a significant level of training, help and close observation by their parents. Their behaviour varied widely, from full co-operation to formal implementation of training instruction or firm refusal. Some of them showed anxiety to varying degrees. Most of the children reached a brief period of concentration of attention during the training, but that was very unstable and rapidly changing. Inadequate listening abilities were also observed.

A number of difficulties were observed throughout the entire implementation of the oral hygiene programme. The instructions were memorized mechanically and for a short time. The children had difficulty applying what they had learned in practice. The strong reaction to touch in some of them made it difficult to ‘penetrate’ the oral cavity. Some of the children experienced a skill breakdown, and we began work to restore their achievements. This slow and difficult process of steps forward and backward in the children’s progress required a lot of patience and conviction that the children will eventually prove receptive to training although some may need much more time to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills.

The results obtained showed that maintaining oral hygiene in autistic children is a serious problem because they cannot effectively brush their teeth due to the difficulties in understanding the concept of maintaining good oral hygiene and putting it into practice. This is illustrated in the Supplemental video (see Supplementary materials).

The obtained results are promising in the context of the scarcity of oral health studies in autistic children. The complexity of impairment in ASD makes dental clinical examination and treatment very difficult. Children with ASD exhibit several behavioural symptoms [Citation2] and may have additional risk factors specific to their disorder [Citation6–8]. Some of these factors may contribute to poor oral hygiene. Dentists often rely on verbal communication for behaviour management. However, treatment by dental practitioners that relies on verbal communication is usually not as efficient for children with ASD because of their general condition. Therefore the prevention of oral diseases is essential [Citation9, Citation10].

The efforts of the dental team and the parents of children with ASD should be directed to maintaining good oral hygiene, diet and all other preventative procedures. These goals are extremely difficult to achieve, but parents and all caregivers must actively participate and assist in this process [Citation11–15].

Many children with special care needs have poorer oral health compared to healthy children, since there are a number of barriers which make it difficult for them to receive adequate dental help [Citation16–18]. Stein et al. [Citation19–21] indicate that sensory hypersensitivity and non-cooperative behaviour in the dental office are important factors in children with ASD preventing them from receiving adequate oral care [Citation21]. This was also observed in our patients (see the Supplemental video, Supplementary materials). Poor oral hygiene is one of the risk factors in children with ASD. Maintaining oral hygiene in autistic patients is a problem. They often do not tolerate any ‘penetration’ into their mouth, even with a toothbrush [Citation22]. In cases of limited cognitive abilities of patients, it is even more difficult to develop stable oral hygiene habits [Citation22]. That is why the behaviour problems of children with ASD during the dental visit are considered the biggest barrier to dental practitioners [Citation18, Citation23–25].

The question of the oral hygiene of children with autism is widely discussed and remains open because of some conflicting results reported by different authors. The results for the oral hygiene status in children with autism are largely controversial, varying from very good to very poor. Several studies have reported good oral hygiene in participants with ASD [Citation9, Citation26–28], but others have indicated poor oral hygiene [Citation29–32], which was also supported by our results.

Problems in the training of children with autism in oral hygiene indicate their stereotypical behaviour and their inadequate skills in tooth brushing and poor knowledge of oral hygiene [Citation30]. Our observations showed that the autistic children included in our study were not able to brush their teeth effectively because of the difficulty they had in becoming aware of and applying their knowledge in practice.

Studies have shown that reduced upper limb coordination leads to difficulties in maintaining optimal oral hygiene in children with ASD [Citation30–32]. This was also confirmed by our results, as we identified uncertain and clumsy motions and poor muscle coordination in conducting oral hygiene.

Our results showed that training and maintaining oral hygiene in children with autism is a serious problem. Other reasons for this were: limited communication ability; short-term concentration and unsustainable attention; inability to understand information and rapid boredom. One possible – although presently disputable – approach to help improve the performance of ASD children is dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT). DAT was provided for one of our patients (see the Supplemental video, Supplementary materials). DAT has been used to treat patients with autism, mental retardation and cerebral palsy for more than 25 years [Citation33]. Advocates of DAT support the choice of dolphins based on the positive image of these mammals, which are extremely intelligent, communicative and curious. They are easily trained, love to play and accept physical contact with people easily, such as hugs, caress and kisses. In the therapeutic sessions, the patient swims and plays with dolphins, performing various tasks to improve hand and eye coordination, fine motor skills, cognitive development or verbal response [Citation33]. Supporters of this form of therapy see it as very attractive and believe it to be very useful; however, there have been skeptic views as well [Citation33–37]. According to the parents of our patient who underwent DT, the results achieved after this therapy were satisfactory, although it is difficult to determine the extent to which DT may have contributed to the child’s oral hygiene skills in particular. In our video, we see a serious improvement in the child’s ability to brush his teeth on his own for most of the time (see the Supplemental video, Supplementary materials).

The oral hygiene status studies for children with disabilities are few. Some of them examine the change in the oral hygiene status for a longer period of time. Nowak [Citation38] commented on the difficulties in improving the oral hygiene of children with special needs. Pilebro and Bäckman [Citation39] assessed the oral hygiene of children with autism from 5 to 13 years using the Silness & Löe index [Citation5]. The authors did not conduct training but relied on the images of the training system that parents used at home. After 18 months, most parents said that maintaining oral hygiene was easier, as a result of improved children’s hand skills. The conclusion drawn by the authors that visual pedagogy was a very useful learning method [Citation39] was also confirmed by the results from our study.

Conclusions

The implementation of the training programme improved the oral hygiene in autistic children, but very slowly, with the introduction of knowledge gradually, step by step, and after many repetitions. Our results showed that the non-verbal communication picture system PECS was a suitable visual method for teaching oral hygiene to children with autism, who have difficulty in social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication. Dentists need to show good understanding for the difficulties ASD children meet in their training and communication with others, and have to work with patience to structure the children’s behaviour in cases where the parents are seeking prophylactic or dental treatment.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (64.8 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism spectrum disorders: data and statistics [Internet]. CDC; 2014. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text revision. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Kanner L. Follow-up study of eleven autistic children originally reported in 1943. J Autism Childhood Schizophr. 1971;1:119–145.

- WHO Expert Committee on Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation & World Health Organization. Disability prevention and rehabilitation: report of the WHO Expert Committee on Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation [meeting held in Geneva from 17 to 23 February 1981]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; 1981.

- Sillness J, Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. A correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135.

- Jaber MA. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:212–217.

- Klein U, Nowak AJ. Characteristics of patients with autistic disorder (AD) presenting for dental treatment: a survey and chart review. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:200–207.

- Marshall J, Sheller B, Mancl L. Caries – risk assessment and caries status of children with autism. Pediatr Dent. 2010; 32:69–75.

- Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. The caries experience and behavior of dental patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1518–1524.

- Weil TN, Inglehart MR. Three- to 21-year-old patients with autism spectrum disorders: parents' perceptions of severity of symptoms, oral health, and oral health-related behavior. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:473–479.

- Bhalla J. Autism and dental management. Ontario Dentist. 2006;(July/August):27–29.

- Zakaria ME. Parents' dental knowledge and oral hygiene habits in Saudi children with autism spectrum disorder. Global J Med Res. 2014;14:3–9.

- Capozza L, Bimsten E. Preferences of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders concerning oral health and dental treatment. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:480–484.

- Twoy R, Connolly PM, Novak JM. Coping strategies used by parents of children with autism. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19:251–260.

- Richa YR, Puranik MP. Oral health status and parental perception of child oral health related quality-of-life of children with autism in Bangalore, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2014;32:135–139.

- Brickhouse TH, Farrington FH, Best AM, et al. Barriers to dental care for children in Virginia with autism spectrum disorders. J Dent Child (Chic). 2009;76:188–193.

- Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Auinger P. Dental needs and status of autistic children: results from the national survey of children's health. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:54–58.

- Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:29–36.

- Stein LI, Polido JC, Mailloux Z, et al. Oral care and sensory sensitivities in children with autism spectrum disorders. Spec Car Dentist. 2011;31:102–110.

- Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory concerns in autism. Am J Occ Therapy. 2012;66:73–76.

- Stein L, Polido J, Cermak S. Oral care and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent.. 2013;35:230–235.

- Christensen G. Special oral hygiene and preventive care for special needs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005; 136:(1141–1143.

- Casamassimo PS, Seale NS, Ruehs K. General dentists' perceptions of educational and treatment issues affecting access to care for children with special health care needs. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:23–28.

- Dao L, Zwetchkenbaum S, Inglehart M. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1107–1115.

- Weil TN, Inglehart MR. Dental education and dentists' attitudes and behavior concerning patients with autism. J Dent Educ. 2010; 74:1294–1307.

- Subramaniam P, Gupta M. Oral health status of autistic children in India. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;36:43–44.

- Naidoo M, Singh S. The Oral health status of children with autism Spectrum disorder in KwaZulu-Nata, South Africa. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:165–169.

- Goncalves L, Goncalves F, Nogueira BML, et al. Conditions for oral health in patients with autism. Int J Odontostomat. 2016;10:93–97.

- Kotha SB, AlFaraj NSM, Ramdan TH, et al. Associations between diet, dietary and oral hygiene habits with caries occurrence and severity in children with autism at Dammam City, Saudi Arabia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:1104–1110.

- Anderson KL, Self TL, Carlson BN. Interprofessional collaboration of dental hygiene and communication sciences & disorders students to meet oral health needs of children with autism. J Allied Health. 2017;46:97–101.

- Morales-Chávez MC. Oral health assessment of a group of children with autism disorder. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;41:147–149.

- Popple B, Wall C, Flink L, et al. Brief report: remotely delivered video modeling for improving oral hygiene in children with ASD: a pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:2791–2796.

- Brensing K, Linke K, Todt D. Can dolphins heal by ultrasound?. J Theor Biol. 2003;225:99–105.

- Marino L, Lilienfeld SO. Dolphin-assisted therapy: flawed data, flawed conclusions. Anthrozoos. 1998;11:194–200.

- Marino L, Lilienfeld SO. Dolphin-assisted therapy for autism and other developmental disorders: a dangerous fad. Am Psychol Assoc. 2007; 33:2–3.

- Marino L, Lilienfeld SO. Dolphin-assisted therapy: more flawed data and more flawed conclusions. Anthrozoos. 2007; 20:239–249.

- Fiksdal BL, Houlihan D, Barnes AC. Dolphin-assisted therapy: claims versus evidence. Autism Res Treat. 2012;2012:839792.

- Nowak AJ. Patients with special health care needs in pediatric dental practices. Pediatr Dent. 2002; 24:227–228.

- Pilebro C, Bäckman B. Teaching oral hygiene to children with autism. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:1–9.