Abstract

This study describes our experience with the treatment of cervical degenerative pathology through anterior cervical decompression and fusion technique. We evaluated the clinical outcome and complications after 6-months follow-up and analysed the data to optimize the efficacy and safety of this particular surgical treatment in order to minimize the risks of complications. The presented study included 111 patients (74 men and 37 women; mean age 56.5 years) treated in the Neurosurgical Department of UMBAL Sv. Ivan Rilski Hospital in Sofia, Bulgaria, for cervical degenerative multilevel pathology with myelopathy. The operations included only anterior cervical approach with single-level or multilevel corpectomy, considering the pathology and neurological deficit in each particular case, followed by instrumented fusion with titanium mesh and locking plates. We analysed the data for intraoperative, early and late postoperative complications and the neurological results were examined and compared with the aid of Nurick and mJOA scales for myelopathy. The mean mJOA score preoperatively was 11.37 (SD ± 2.63) and postoperatively the mean mJOA score was 13.27 (SD ± 2.61), p < 0.0001. Since the emerging of this technique more than 50 years ago, it has improved in many ways, although there are still some contradictory results. Still, the most important aspect should be to consider the individual’s pathology in order to better understand the underlying problems and think of ways to resolve them appropriately.

Introduction

Multilevel cervical spondylosis is the most common chronic degenerative disease, leading to progressive myelopathy in people over 55 years of age. Multilevel cervical spondylosis has an indistinctive subtle beginning [Citation1–4]. The progression of cervical myelopathy may remain unnoticed until clinical presentation of severe spinal compression [Citation5]. Although we see degenerative changes in the spine in 20 to 25% of people under 50 years of age and 70 to 95% in 65-year-old patients, comparatively only a few of them have symptoms of cervical stenosis or have transient attacks which may be treated with conservative techniques [Citation6].

The first report on the syndrome of cervical spondylotic myelopathy was in the 1950s by Brain et al. [Citation7]. In the following years, different techniques evolved to treat this type of severe cervical compression surgically. The most common operation was laminectomy with its subsequent contradictory results. Its technically difficult implementation, providing minimal traction of the medially situated spinal cord, required the establishment of different variations for anterior decompression followed by fusion techniques. The first cervical fusion technique was described in the 1950s by Bailey and Badgley [Citation8] and five years later Smith and Robinson [Citation9] reported the discectomy technique, followed by the arthrodesis with horseshoe-shaped bone implant. In 1958 Cloward [Citation10] introduced the technique for disc removal and intervertebral fusion with cylindrical bone implant. All these interventions had their weaknesses, the most common one being the displacement of the implant and failing to achieve the desired fusion. One possible way to prevent this drawback was by adding supplementary fixation in front of the operated level, which led to the development of anterior plates for fixation, the first ones introduced by Bohler in 1964 [Citation11].

The different anterior techniques have different and individual-based approaches, although it has not been proven which surgical technique is optimal for the treatment of this vast pathology in its heterogenous presentation [Citation12,Citation13].

There are still no guidelines that outline the specific management of patients with different type of myelopathy: mild (defined as a modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) score of 15-17), moderate (mJOA = 12–14), or severe (mJOA ≤ 11) or nonmyelopathic patients with evidence of cord compression [Citation14,Citation15].

In our clinic there is predominance in the use of the anterior approach for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy, compared to the posterior ones, such as foraminotomy, laminotomy and laminectomy. The aim of this study was to present our experience with treatment of cervical degenerative pathology through anterior cervical decompression and fusion. The neurological symptoms before and early after the operation were compared with those at the 6-month follow-up. The complications that we encountered were outlined and compared with the literature.

Subjects and methods

Ethics statement

All patients gave informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Subjects

In the study, we included 111 patients for a 5-year period, from January 2011 until December 2015, who were evaluated prospectively. All of the patients were diagnosed with degenerative cervical myelopathy and were operated in the Clinic of Neurosurgery at the University Hospital “Sv. Ivan Rilski” in Sofia, Bulgaria. The operations included anterior decompression technique with one or multilevel corpectomy, compliant with each individual’s pathology and the underlying neurological deficit. As part of the mentioned technique, each operation included fusion with titanium or PEEK meshes and plates from the systems Stryker, Medtronic, Alphatec Spine. The patients included in the present study did not have any preceding operations for other underlying cervical pathology. The minimal period for complaints was 1 month and all patients underwent active conservative therapy, which did not improve significantly the ongoing neurological deficit.

The male to female ratio was 2:1 (74 men and 37 women) with age distribution between 32 and 80 years (mean 56.5 years).

Clinical evaluation

All patients were clinically evaluated according to the myelopathy scales - modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scoring system (mJOA) and Nurick grading system preoperatively and in the early postoperative period, as well as after 3 and 6 months with face-to-face interviews, phone calls and/or mail [Citation14]. We gathered the data needed preoperatively and during the postoperative period. In order to compare Nurick and mJOA we used paired t-test and for the correlations we used non-parametric correlation analyses.

Inclusion criteria

Every patient included in the study had to meet the following criteria for neurological deficit: severe degree of cervical myelopathy with spasticity, hyperreflexia and positive pathological reflexes like Babinski sign or Hoffmann’s sign; severe sensory deficit; motor deficit, including weakness of the four limbs, muscle atrophy, paraparesis, paraplegia, tetraparesis or tetraplegia; sphincter dysfunction.

Imaging techniques

Myelopathy was also confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT of the cervical region, as well as X-ray. Postoperatively we evaluated the results with the aid of an X-ray image on the 3rd day after the operation, as well as performing mandatory follow-up X-rays at 1.5 and 3 months; some cases with complaints underwent CT or MRI.

Measurements

In order to assess the cervical lordosis or kyphosis by measuring the Cobb angle, we measured the angle formed between the lower endplate of C2 and the upper endplate of C7 on X-rays before and after the operations. If we had some suspicion for instability, we made dynamic X-ray - flexion and extension images.

Data analysis

We used Chi-square tests and Levene’s test for equality of variances in intergroup comparisons of categorical variables and categorical variables were expressed as numbers. For nonparametric measure we used Spearman’s rho. Differences were considered statistically significant at a level of p < 0.05. The calculations were performed using a statistical package programme IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0.0.0.

Surgical operation

The surgical operation starts by placing the patient in a supine position under general anaesthesia. Usually we make cervical anterior Smith-Robinson incision on the left side [Citation16]. After careful dissection, we ensure that the levels are correct by using intraoperative C-arm. After reaching the anterior longitudinal ligament, we make incision at the level of the interververtebral discs above and below the level of corpectomy with the aid of a microscope. To ensure that the decompression was adequate, in most of the cases when this is possible, we resect the posterior longitudinal ligament to the limit of the dural sac. After meticulous haemostasis, we reconstruct the vertebra by using a titanium mesh whose size is precisely measured and compliant to the individual’s anatomical characteristics. We finish the vertebrodesis by placing a titanium plate of suitable length and curvature in the adjacent disc space and fix it with six screws.

Results and discussion

Operated levels

The patients who underwent single-level corpectomy were 57, those with two adjacent levels were 40, three levels were operated in 10 patients, and four-level corpectomy was made in 1 patient from the selected group. We had “skip” level technique performed in 3 cases. The total count of levels with corpectomies made was 177 or a mean of 1.59 per intervention. The most common level operated was C5 in 77 patients (69%); followed by C6 in 62 patients (55.8%), C4 in 34 (30.6%) and C7 level in 4 patients (3.6%).

Correlation analysis between mJOA and Nurick myelopathy scales

Only a few studies estimate the functional outcome of patients included by using both myelopathy scales [Citation17]. Vitzthum and Dalitz [Citation18] show improvement in the Nurick score by 33% postoperatively, versus improvement in the mJOA score by 81%. This can be attributed to the fact that mJOA scores the functionality of the upper extremities, whereas Nurick is used for grading the mobility status for the lower extremities. In the present study, we included both myelopathy scales. Nurick before the operation had a mean value of 2.52 with standard deviation (±SD) of 1.13, and after the operation the mean value was 1.98 (SD ± 1.20), p < 0.0001. The mean value for the mJOA scale preoperatively was 11.37 (SD ± 2.63) and the postoperative mean mJOA value was 13.27 (SD ± 2.61), p < 0.0001. Of all 111 patients included, 38 had improvement by two points according to the mJOA score, 35 had imporvement by one point, 26 by three points, three by 4 points and two of them by 5 points. Six patients did not have any change in their preoperative score compared to the postoperative one. Correlation analysis between the mJOA and Nurick scales shows negative correlations, meaning that the greater the results on the mJOA scale, the smaller the values on the Nurick scale. These relations show that a greater value of mJOA preoperatively correlates with a greater value of mJOA after the operation. This indicates that the better the myelopathic status preoperatively is, the better the myelopathic improvement postoperatively will be. This can be acknowledged as a primary prognostic factor for the clinical result of the operation.

Correlation analysis between mJOA score and C2-C7 Cobb angle

A few studies present improvement in the patients’ clinical status postoperatively, when the lordotic curve is preserved. Wu et al. [Citation19] suggest a connection between improvement in the mJOA score and C2-C7 Cobb angle after anterior cervical fusion. Other theories indicate that sagittal misalignment after anterior cervical fusion can lead to cervical instability, postoperative axial pain and progressive neurological deficit [Citation20]. All these factors can affect the neurological improvement.

Cobb angle after operation was negatively correlated with the axial pain before operation

In our cohort, the Cobb angle before the operation had a mean value of 14.00 (SD ± 11.53). The Cobb angle after the operation had a mean value of 14.77 (SD ± 7.86). We used paired t-test with results for p = 0.41. Our results showed that the greater the axial pain before the operation was, the lesser the Cobb angle preoperatively was. The loss of segmental cervical lordosis can affect the whole integrity of the region and can increase the biomechanical pressure of each vertebra, leading to progressive degeneration. That is why the surgeon should always strive to achieve normal cervical lordosis.

Cobb angle after operation was negatively correlated with the number of operated levels

We used Spearman’s test in order to assess the correlations between Cobb angle before and after the operation, as well as the correlations between Cobb angle and the number of operated levels. The results for the Cobb angle before and after the operation were p = 0.000 and Spearman’s ρ = 0.583. There was negative correlation between the Cobb angle after the operation and the number of operated levels: p = 0.002 and Spearman’s rho= −0.409, i.e. the bigger the Cobb angle was, the less the operated levels were.

Complications

Literature data show that the general complications vary from 3% to 48%, with an average number around 31%. The complications reported are more common with older patients, with every decade of life increasing the complications rate 1.6 times [Citation21].

Possible complications from an operation with anterior decompression are related to damage of the surrounding soft tissues, the neural structures or hardware. One of the most serious surgical problems is the oesophageal perforation, according to the literature data − 0.2-0.9% of all cases, which could be observed later during the follow-up period [Citation22]. The most common complication is postoperative dysphagia in 2-48% of all patients [Citation23]. The symptoms are usually transient, but can become chronic in up to 12% of the cases as described in the literature [Citation24]. Its aetiology includes haemotoma in the operative field, continuous intraoperative retraction, denervation of the upper oesophagus or damage of the pharyngeal plexus. Iatrogenic damage of the vertebral artery according to the literature is present in 0.03% of all cases [Citation20].

The rates of total complications according to Wang et al. [Citation25] were 20.1%. They report that C5 palsy, infection, dysphagia, graft subsidence, graft dislodgment and epidural haematoma were 20.1%, 5.3%, 16.8%, 3.7%, 3.4% and 1.1%, respectively.

Intraoperative complications

In the present cohort of patients, we had 3 intraoperative complications: dural lacerations, or 2.7% of all cases. One of the patients had corpectomy on one level (C5) with hypertrophy combined with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Two patients had dural lacerations in two-level corpectomy operation – levels C5 and C6, along with OPLL. All three patients underwent dural plastics with adipose tissue and fibrin glue, without further findings for liquorrhea postoperatively.

Early postoperative complications

During the early postoperative period, from the end of the operation until the day of discharge from hospital, usually 3 to 5 days postoperatively, we had 4 subcutaneous haematomas in a resorption stage, or 3.6% from all patients. We observed transient dysphagy in 11 patients, or 9.9% of all. They all had total recovery by the day of their discharge. We had two patients with persisting dysphagy for a period of over 2.5 years of follow-up, without any other reported complications from the meticulous neurological examination or imaging done.

One patient in our cohort, or 0.9% of all, had a complication not directly related to the operation – pulmonary oedema, with subsequent sepsis and death.

Saunders et al. [Citation26] described 40 cases with perioperative complications of 47.5%. Most of them are due to the approach used and are linked to the mechanical manipulation of the soft tissues. The inadequate avascular dissection of the fascia leads to direct damage to the oesophagus, trachea, the carotid or vertebral arteries or the laryngeal nerve [Citation26]. Most often, the possible damage affects C5 nerve root and is usually transient. In older techniques, where bone grafts are used, the reported complications with the fusion materials are more common compared to the possible damage from the approach only [Citation27].

The definition of C5 palsy is disturbance in the muscle tone of the deltoid or biceps muscle postoperatively without any other neurological deficit. According to the literature the distribution of postoperative C5 palsy is reported between 0% and 30% [Citation28]. Odate et al. [Citation3] studied 459 patients and reported C5 palsy in 7% (32) of the cases. The diagnosis was cervical spondylotic myelopathy for 19 patients and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in 13 patients. One of the theories for possible prevention is the restriction of the width for decompression to be less than 15 mm and avoidance of asymmetric decompression [Citation29].

Five patients from our group had C5 palsy, or 4.5% of the whole group. Two of them had single-level corpectomy, two had two-level corpectomy, and one of them had undergone the “skip” technique. Three patients from this group had total recovery within a month and a half, and two of them within 6 months. Intraoperatively, there are no concerning data that could provide essential information about the underlying pathology or the operative technique used for these particular cases.

Complications linked to the instrumentation system

Another study by Wang et al. [Citation30] reports displacement of the grafts observed in 4 patients out of 95 (4.2% of all) operated for one-level corpectomy; 4 out of 76 (5.2%) operated for two-level corpectomy; 7 (or 9.9%) out of 71 patients operated for three-level corpectomy and one displacement (16.7%) out of a total of six patients operated for four-level corpectomy. In the report by Wang et al. [Citation30], the total complications rate percentage is 16 (6.4%) out of 249 patients.

According to Vaccaro et al. [Citation31], the reported complications linked to the instrumention system are 3 (9%) out of 33 patients after two-level corpectomy and 6 (50%) out of 12 patients operated with three-level corpectomy. Sasso et al. [Citation32] reported instrumented complications in 2 patients (6%) out of 33 operated on two levels and in 5 (71%) operated on three levels.

We had 4 patients (3.6%) who needed revision of the intraoperatively placed instrumentation system. One of them had an operation which included two-level corpectomy - C5 and C6 levels. His preoperative Cobb angle was 21.4о, whereas the postoperative one was 16.6о. He underwent postoperative X-ray imaging, indicating dorsal migration of the titanium mesh, compared to the intraoperative X-ray control pictures. The patient did not have any complaints or complications conserning his overall and neurological status. He had revision made with repositioning of the titanium mesh without subsequent complications in the subsequent follow-up period. Another patient had dorsal migration of the titanium mesh, but the migration was detected on control X-ray at the three-month follow-up. She did not have any complaints or neurological deficit. The operated levels were C4 and C5.

Two patients in our cohort had displacement of the pate in the caudal end with titanium screw extraction but without migration beyond the borders of the fixation points on the plate. One of them had two-level corpectomy: C4 and C5. He had preceding complaints of dysphagia, starting around 3 months after surgery. He had control X-ray, showing displacement of the plate, followed by revision and removal of the implant. The other patient underwent the “skip” technique with corpectomy made at C4 and C6 levels. He also had complaints of dysphagia with preceding X-ray made and total removal of the plate. Both patients had complete recovery.

Adjacent level stenosis

There are still conflicting vies about the progression of adjacent level stenosis after the fusion technique is done [Citation33]. According to Hilibrand et al. [Citation34], the percentage of newly developed pathology adjacent to the operated level is constant at 3% yearly. The most affected levels are C5-6 and C6-7 and are more frequently affected after fusion on one level, than in multilevel stenosis. Kong et al. [Citation35] report a meta-analysis showing that the prevalence of radiographic adjacent segment degeneration (ASD), symptomatic ASD and reoperation ASD after cervical surgery was 28.28%, 13.34%, and 5.78%, respectively. There were reported 2.79%, 1.43%, and 0.24% increase per year of follow-up in the incidence of radiographic ASD, symptomatic ASD, and reoperation ASD, respectively [Citation35].

In our study, adjacent level disease was observed in two patients, representing 1.8% of all (Clinical Case).

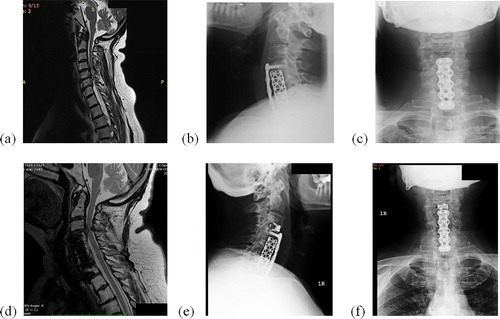

Clinical case

A 66-year-old woman was operated in our clinic for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (). Corpectomy was done on levels C5, C6, followed by fusion with titanium mesh and plate (). The duration of complaints was 2 years; mJOA before the operation was 9, and after the operation 13; the Nurick score before the operation was 3, and after the operation 2. After a 3-year period postopertively the patient came with complaints of progressive myelopathy with an MRI image showing disc herniation on level C3-C4, compressing the spinal cord adjacent to the operated levels (). We did anterior discectomy with implanting PEEK cage Coalition, and the patient had very good recovery ().

Choice of technique

The surgical treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy includes decompression, reconstruction of the anterior spinal column and fusion. Depending on the individual case and the goal of the treatment, the possible surgical options include anterior, posterior or two-stage surgery including both approaches. There are two possible anterior approaches: anterior cervical discectomy or anterior cervical corpectomy, both followed by fusion. They are proven to be effective and safe. When there is neurological deficit indicating cervical spondylosis and myelopathy encompassing more than one level, usually adjacent, the decision as to which approach is most favourable is still disputable [Citation36,Citation37].

When we make anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, we can effectively decompress the anterior spinal cord and preserve the spinal stability. According to some authors, however, this is not the optimal approach for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy because of the inability for optimal decompression behind the vertebral body [Citation38]. Other disadvantages of the approach are the limited visual field and the increased risk for pseudoarthrosis, because of the multiple fusion sides between the single grafts and the recipient. While the anterior corpectomy and fusion minimizes the number of fusion sites, aiding for wider decompression, its disadvantage is having less points of fixation into the stabilizing plate [Citation39].

In a study conducted in 2015 by Darryl Lau, a group of three-level discectomy with fusion including 35 patients is compared to a group of two-level corpectomy with fusion (20 patients). The choice of technique was based on the presence of compression behind the centre of the vertebral body. The authors do not report any statistical difference between the two groups, comparing the duration of the hospital stay, perioperative complications, postoperative cervical lordosis, the adjacent level stenosis, the stages of radiographic pseudoarthrosis or the neurological imporvement [Citation40].

In the past, one of the major contradictions between multiple discectomy with fusion and multiple corpectomy with fusion concerned the lower fusion extent in the multilevel discectomy with fusion group [Citation41]. Literature data show that more than 20 years ago there was pseudoarthrosis in 44% of three-level discectomy with fusion cases [Citation42]. The explanation for these high rates is based on the multiple fusion sides between the grafts and the recipient sides, compared to the corpectomy technique. In some more recent studies [Citation38,Citation43,Citation44], the degree of fusion varies between 88% and 97% and does not differ between the two groups. Other studies claim that three-level discectomy has higher rates of fusion compared to corpectomy (100% vs. 85–90%) [Citation44]. These recent results of pseudoarthrosis should be taken into account as a result of improved surgical technique, equipment and technology.

Conclusions

Although in recent years there are contemporary surgical techniques for the treatment of degenerative cervical myelopathy, there are still some problems that need to be taken into consideration. The complications accompanying the surgical treatment with corpectomy are exceptionally variable. In recent years, there is growing precision in the technological innovations in the available instrumentation systems, as well as refinement in the surgical technique, aiming to optimize the results and the neurological improvement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Boogaarts HD, Bartels RHMA. Prevalence of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(S2):139–141.

- Azimi P, Shahzadi S, Benzel EC, et al. Functional evaluation using the modified Japanese Orthopedic Association score (mJOA) for cervical spondylotic myelopathy disease by age, gender, and type of disease. J Inj Viol Res. 2012;4(3 Suppl 1):42.

- Odate S, Shikata J, Kimura H, et al. Hybrid decompression and fixation technique versus plated 3-vertebra corpectomy for 4-segment cervical myelopathy. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(6):226–233.

- Toledano M, Bartleson JD. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurol Clin. 2013;31(1):287–305.

- Liu S, Yang D, Zhao R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of axial neck pain in patients undergoing multilevel anterior cervical decompression with fusion surgery. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):94.

- Montano N, Ricciardi L, Olivi A. Comparison of anterior cervical decompression and fusion versus laminoplasty in the treatment of multilevel cervical spondilotyc myelopathy: a meta-analysis of clinical and radiological outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:530–536.e2.

- Brain WR, Northfield D, Wilkinson M. The neurological manifestations of cervical spondylosis. Brain 1952;75(2):187–225.

- Bailey RW, Badgley CE. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42(4):565–594.

- Smith GW, Robinson RA. The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40(3):607–624.

- Cloward RB. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J Neurosurgery. 1958;15(6):602–617.

- Burkhardt BW, Müller S, Oertel JMK. Influence of prior cervical surgery on surgical outcome of endoscopic posterior cervical foraminotomy for osseous foraminal stenosis. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:14–21.

- Mardhika PE. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: pathophysiology and surgical approaches. Recent Adv Biol Med. 2017;03:83–91., Marta KKA, Maliawan S, Mahadewa TGB.

- Badhiwala JH, Hachem LD, Merali Z, et al. Predicting outcomes after surgical decompression for mild degenerative cervical myelopathy: Moving beyond the mJOA to identify surgical candidates. Neurosurgery. 2019. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz160

- Tetreault L, Kopjar B, Nouri A, et al. The modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scale: establishing criteria for mild, moderate and severe impairment in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(1):78–84.

- Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Riew KD, et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: Recommendations for patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease and nonmyelopathic patients with evidence of cord compression. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3_suppl):70S–83S.

- Choudhri O, Ryu, S, Kim, DH, et al., editors. 2013. Cervical corpectomy, fusion, and vertebral restoration techniques In: Surgical anatomy and techniques to the spine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA (USA): Saunders Elsevier; 2013. p. 162–181.

- Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Kurpad S, et al. Change in functional impairment, disability, and quality of life following operative treatment for degenerative cervical myelopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3_suppl):53S–69S.

- Vitzthum HE, Dalitz K. Analysis of five specific scores for cervical spondylogenic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(12):2096–2103.

- Wu W-J, Jiang L-S, Liang Y, et al. Cage subsidence does not, but cervical lordosis improvement does affect the long-term results of anterior cervical fusion with stand-alone cage for degenerative cervical disc disease: a retrospective study. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(7):1374–1382.

- Cheung JP, Luk KD. Complications of anterior and posterior cervical spine surgery. Asian Spine J. 2016;10(2):385–400.

- Eleraky MA, Llanos C, Sonntag VKH. Cervical corpectomy: report of 185 cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg: Spine. 1999;90(1):35–41.

- Gaudinez RF, English GM, Gebhard JS, et al. Esophageal perforations after anterior cervical surgery. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13(1):77–84.

- Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Persistent swallowing and voice problems after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(7):677–682.

- Yang Y, Ma L, Liu H, et al. Comparison of the incidence of patient-reported post-operative dysphagia between ACDF with a traditional anterior plate and artificial cervical disc replacement. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;148:72–78.

- Wang T, Tian XM, Liu SK, et al. Prevalence of complications after surgery in treatment for cervical compressive myelopathy: A meta-analysis for last decade. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(12):e6421.

- Saunders RL, Bernini PM, Shirrefks TG, et al. Central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a consecutive series with long-term follow-up evaluation. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(2):163–170.

- Heneghan HM, McCabe JP. Use of autologous bone graft in anterior cervical decompression: morbidity & quality of life analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:158.

- Thompson SE, Smith ZA, Hsu WK, et al. C5 palsy after cervical spine surgery: a multicenter retrospective review of 59 cases. Global Spine J. 2017;7(1_suppl):64S–70S.

- Nassr A, Eck JC, Ponnappan RK, et al. The incidence of C5 palsy after multilevel cervical decompression procedures. Spine 2012;37(3):174–178.

- Wang JC, Hart RA, Emery SE, et al. Graft migration or displacement after multilevel cervical corpectomy and strut grafting. Spine 2003;28(10):1016–1021.

- Vaccaro AR, Falatyn SP, Scuderi GJ, et al. Early failure of long segment anterior cervical plate fixation. J Spinal Disord 1998;11(5):410–415.

- Sasso RC, Ruggiero RA, Reilly TM, et al. Early reconstruction failures after multilevel cervical corpectomy. Spine 2003;28(2):140–142.

- Hashimoto K, Aizawa T, Kanno H, et al. Adjacent segment degeneration after fusion spinal surgery—a systematic review. Int Orthopaed (SICOT). 2019;43(4):987–993.

- Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, et al. 1999. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. Rothman Institute. Paper 8. Available from: http://jdc.jefferson.edu/rothman_institute.

- Kong L, Cao J, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of adjacent segment disease following cervical spine surgery: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(27):e4171.

- Zárate-Kalfopulos B, Araos-Silva W, Reyes-Sánchez A, et al. Hybrid decompression and fixation technique for the treatment of multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:30.

- Badhiwala JH, Witiw CD, Nassiri F, et al. Efficacy and safety of surgery for mild degenerative cervical myelopathy: Results of the AOSpine North America and International Prospective Multicenter Studies. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(4):890–897.

- Song KJ, Lee KB, Song JH. Efficacy of multilevel anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus corpectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a minimum 5-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1551–1557.

- Lin Q, Zhou X, Wang X, et al. A comparison of anterior cervical discectomy and corpectomy in patients with multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(3):474–481.

- Lau D, Chou D, Mummaneni PV. Two-level corpectomy versus three-level discectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a comparison of perioperative, radiographic, and clinical outcomes. SPI. 2015;23(3):280–289.

- Gould H, Sohail OA, Haines CM. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: Techniques, complications, and future directives. Seminars Spine Surg. 2019;100772.

- Bolesta MJ, Rechtine GR, Chrin AM. Three- and four-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate fixation. Spine 2000;25(16):2040–2046.

- Liu Y, Qi M, Chen H, et al. Comparative analysis of complications of different reconstructive techniques following anterior decompression for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(12):2428–2435.

- Guo Q, Bi X, Ni B, et al. Outcomes of three anterior decompression and fusion techniques in the treatment of three-level cervical spondylosis. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(9):1539–1544.