Abstract

Recent publications and studies propose using decision-making algorithms in choosing the optimal approach for each individual case of tuberculum sellae meningioma (TSM). Minimally invasive endoscopic approaches offer the possibility of early devascularization, reduced brain and nerve retraction and speedy patient recovery. We used the decision-making algorithm proposed in the literature to choose between the extended endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) or the classic transcranial approaches for resection of tuberculum sella/planum sphenoidale meningiomas, based on anatomical landmarks and lateral extension. We describe rates of gross-total resection, visual outcomes, as well as complications in four cases of TSMs, where EEA was used based on the proposed algorithm. Over a period of 15 months, we used the algorithm in nine patients with tuberculum sella/planum sphenoidale meningiomas, in four of whom we used the extended EEA. The mean follow-up duration was 3 months. Gross-total resection was achieved in three out of the four cases, the fourth being a second operation a long period of time after the classical transcranial approach had been used. Visual improvement was achieved in three out of the four cases. One patient had stable vision. There were no cerebrospinal fluid leaks or any kind of neurological postoperative deterioration, although a patient developed pulmonary embolism, but recovered successfully and was discharged. The algorithm proposed in the literature that was explored here is simple, minimally invasive and can produce excellent outcomes in the surgical resection of TSMs in carefully selected cases.

Introduction

The extended endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) for the treatment of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas has been increasingly reported in the last two decades [Citation1–8]. Critical vascular structures (such as the internal carotid and anterior cerebral arteries) and neural structures (such as the optic nerves and the diencephalon – hypothalamus, infundibulum and the pituitary gland) lie in close proximity to the points of origin of these tumours, which are either the tuberculum sella, chiasmatic sulcus or the limbus sphenoidale [Citation9]. The most common clinical symptoms, such as impaired visual acuity and hemianopia, are considered as the primary indication for surgical resection. Radiotherapy is usually reserved for asymptomatic tuberculum sella meningiomas (TSMs) without tumour compression upon the optic apparatus [Citation10].

Using transcranial or endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for resecting these tumours is still a topic of debate [Citation10], although recent publications and studies propose using decision-making algorithms in choosing the optimal approach for each individual case of TSMs, which constitute around 5–10% of all intracranial meningiomas [Citation11]. The surgeon’s experience, tumour location and size, as well as relation with the surrounding neurovascular structures are critical in the selection of the most adequate surgical approach [Citation12]. Here, we used the decision-making algorithm proposed in the literature [Citation13] for using the extended EEA, however sufficient results in large series are still lacking [Citation10, Citation13].

Subjects and methods

Ethics statement

All patients gave informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Subjects

Over a period of 15 months, we used the algorithm in nine patients with tuberculum sella/planum sphenoidale meningiomas, in four of whom we used the EEA. All of the patients were operated in the Clinic of Neurosurgery at the University Hospital ‘Sv. Ivan Rilski’ in Sofia, Bulgaria. The operations included extended transsphenoidal endoscopic transplanum/transtuberculum biportal approach. The patients’ information, variables and tumour information were obtained from the medical records and radiology, pathology and operative reports.

All the four patients who were subjected to the EEA were women, with age distribution between 55 and 67 years (mean 58.75 years).

We describe the rates of resection (gross-total (GTR) 100%, near-total resection (NTR) ≥95% and <100% and subtotal resection <95%), visual outcomes, as well as complications in four cases of TSMs, where EEA was used based on the proposed algorithm. Patients underwent clinical and neuroradiological (MR imaging with and without Gd unless otherwise contraindicated) evaluations at 3 months after surgery and annually thereafter.

Inclusion criteria

The decision-making algorithm for using either the extended EEA or the classic transcranial approach, based on anatomical landmarks and lateral extension, is relatively new [Citation13]. We took into consideration two factors: one being the lateral extension of the tumours, and the other being the anatomical localization according to the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus with >50% of their diameter behind this point to be PS or TS meningioma. According to the authors [Citation13] tumours with extension lateral to the internal carotid artery (ICA), to the anterior clinoid process, or to >5 mm beyond the lamina papyracea undergo a transcranial approach, whereas all other tumours are preferably resected via an EEA.

Representative cases

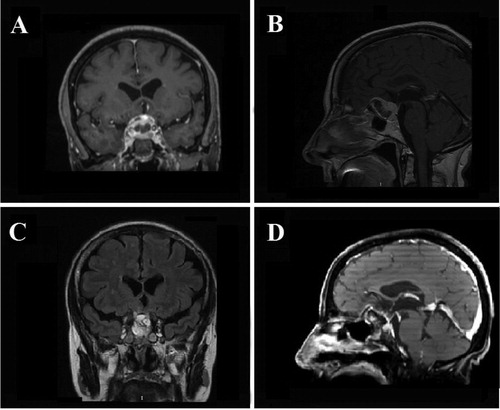

Case 1. A 67-year-old woman was presented with progressive headaches with bilateral loss of visual acuity and bitemporal hemianopia. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a large TSM with superior extension (). Because of the midline location and the fact that there was no extension beyond ICA, an EEA was performed. The tumour was relatively soft and descended easily. A GTR was achieved (). The patient recovered very well without having a CSF leak or any other surgical complication. There were no complications 27 months after the surgery. At the control eye examination test, the patient had improvement in both visual acuity and fields.

Figure 1. Case 1. Preoperative coronal (A) and sagittal (B) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing a large TSM with superior extension. Postoperative coronal (C) and sagittal (D) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing GTR of the TSM.

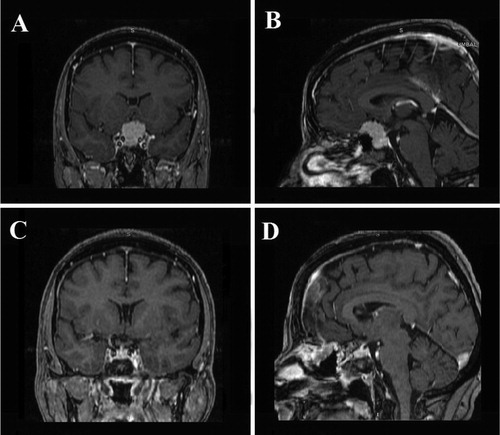

Case 2. A 55-year-old woman was presented with headaches that worsened in frequency and intensity as well as loss of visual acuity and hemianopia. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a TSM with inferior sellar extension and midline location (). An EEA was performed. Intraoperatively, the tumour was found to be very soft and easily dissectible. A GTR was achieved. (). The patient has done well without any complications since her surgery 30 months ago. At her control eye examination test, she had improvement in both visual acuity and hemianopia.

Figure 2. Case 2. Preoperative coronal (A) and sagittal (B) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing a large TSM with inferior sellar extension and midline location. Postoperative coronal (C) and sagittal (D) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing GTR of the TSM.

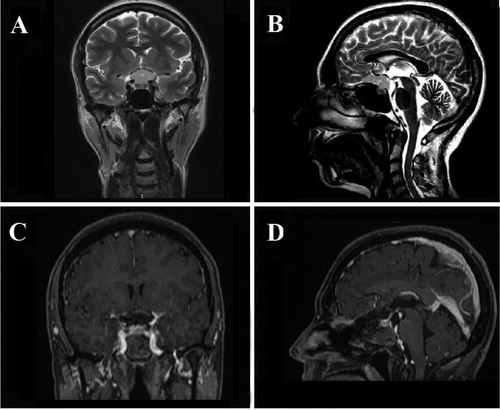

Case 3. A 56-year-old woman was presented with a several-month history of mainly left eye visual loss and headaches. Her workup included MR imaging of the brain, which demonstrated a small midline TS/PS tumour with a large part of it extending towards planum shpenoidale without lateral extension beyond the internal carotid arteries (). A part of the tumour was compressing mainly the left optic nerve. Because the tumour size and location were amenable, an EEA was performed. We achieved GTR (). Repair of the skull base and dural defect was achieved using fat graft and autologous fibrin glue. There were no neurosurgical complications, although the patient developed a mild form of pulmonary embolism 3 days after surgery and had to be moved in ICU. The patient recovered successfully and was discharged without having had any complication since the EEA 9 months ago. At her control eye examination test, she had improvement in visual acuity in her left eye.

Figure 3. Case 3. Preoperative coronal (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted MR images showing a large TS/PS tumor without lateral extension beyond the internal carotid arteries. Postoperative coronal (C) and sagittal (D) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing GTR of the TSM.

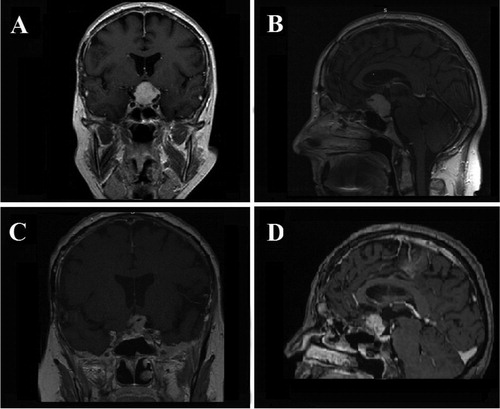

Case 4. A 57-year-old woman was presented with a several-week history of mild visual loss and headaches. She had a TSM surgically removed to an unknown extent 8 years ago using classical transcranial pterional approach. She had not made annual follow-up MRIs after the surgery. Following her complains she did an MRI imaging of the brain, which demonstrated a midline TSM adherent to the brain structures and with mainly suprasellar extension (). Because of the tumour size and location, we decided to try an EEA. The procedure was complicated by extensive adherences around the optic nerves and near the left A1-AcomA-A2 vascular complex as well as left cavernous sinus. Therefore, we managed to achieve sub-total resection (), leaving some parts of devascularized tumour adherent to these vital structures. Repair of the skull base and dural defect was achieved using a fat graft and autologous fibrin glue. There were no neurosurgical complications since the EEA 5 months ago. At the control eye examination test, the patient had stable visual acuity in both eyes.

Figure 4. Case 4. Preoperative coronal (A) and sagittal (B) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing a large midline TSM adherent to the brain structures and with mainly suprasellar extension. Postoperative coronal (C) and sagittal (D) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images showing STR of the TSM.

Results and discussion

The tumours were between 2.5 and 4 cm in size, without optic canal involvement or lateral extension beyond ICA or medial orbital wall. All patients had some visual field or acuity deficit prior to surgery. Gross-total excision was achieved in three patients. In one patient, some residue had to be left behind because of severe adherence of the tumour due to prior transcranial surgery. Following surgery, visual improvement was noted in three of the four patients and in one patient the vision was stable. One patient developed pulmonary embolism, but recovered successfully and was discharged. In all four patients we used fat grafts, fibrin glue (in two of the patients we used autologous fibrin glue) and naso-septal flaps. There were no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks or any kind of neurological postoperative deterioration.

Consideration in surgical practice

Many advances have taken place over the past century in the surgical treatment of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas, however their surgical resection still poses a significant challenge to neurosurgeons. Various microsurgical techniques have been developed in order to improve the treatment, outcome and cure rates of these tumours. One of the main symptoms that the anterior skull base location of these tumours often produces, through compression and elevation for the optic apparatus, is visual impairment, such as bitemporal visual field deficit, especially those that originate in the region of tuberculum sella, chiasmatic sulcus or limbus sphenoidale. Decompressing the neurovascular structures from the neurological mass effect caused by meningiomas through complete resection of the tumour should be the main surgical goal. However, complete surgical extirpation cannot always be obtained. Sometimes in order for the patient to not exhibit neurological deterioration from complete removal, sufficient results can also be achieved with subtotal tumour resection.

Many authors have described the EEA surgical techniques in details [Citation1, Citation14–18]. We successfully used minimally invasive approaches in all four of the presented cases, and we achieved GTR in 75% of the cases and STR in the fourth. To reduce the postoperative risk of intracranial complications, mainly CSF leaks, a posteriorly based naso-septal flap by Hadad et al. [Citation19] was used in all our cases. This flap, based on the posterior septal artery, is raised at the beginning and left pedicled posteriorly towards the nasopharynx during the tumour resection. We used the flap, as well as fat grafts and fibrin glue in all of the four cases with excellent results without any CSF leaks. Recently, there have been some new closure techniques presented using a bioresorbable polydioxanone foil, which is placed between the dura and the bony margins to keep the intrasellar implants in place and to withstand the pressure arising from the intracranial compartment [Citation20], however further study is required.

The main criticism of these minimally invasive approaches is that the rate of Simpson grade I resections may be lower. However, the literature does not support this as highlighted by Ottenhausen et al. [Citation13]. The development of modern neurosurgical tools and the introduction of radiation therapy have made the outcome for all grade resections essentially the same [Citation21–23]. According to some recent reports, GTR is achieved in 84.1% of the cases of PS and TS meningiomas using transcranial approaches [Citation24] with slightly better results in GTR (100%) using EEA [Citation13]. In a series of 41 microsurgically treated patients with long-term follow-up, the vision improved in 83.3% of transcranial resections [Citation25] compared to 97.5% when EEA was used [Citation13]. One of the key factors in selecting the most appropriate approach is the lateral extension of the TSM [Citation26].

Stereotactic radiosurgery is usually reserved for controlling the growth of small- and medium-sized anterior skull base meningiomas, often delivered in fractions over a period of time [Citation27–31], allowing the normal tissue to repair between the doses. Various publications from different authors have successfully described the use of fractionated radiotherapy either by stereotactic delivery or external beam therapy [Citation27–31]. The visual deterioration following fractionated doses of stereotactic radiotherapy in one study was reported to be around 3% [Citation32].

Advantages and disadvantages of EEA over classical transcranial approaches (TCA)

The EEA is the most direct approach to the tuberculum sella [Citation33]. TSMs are vascular lesions that usually receive their blood supply from dural vessels, McConnell’s capsular arteries and sometimes other branches [Citation34]. One of the main advantages over the classical TCA is early tumour devascularization. The lesion is therefore debulked safely and the capsule can be dissected from the surrounding microvascular structures via the extraarachnoidal route with minimal blood loss compared to the TCAs. Using appropriately chosen angled endoscopes after initial tumour removal, produces a lateral view that is proven to find tumour remnants that could not be seen with the microscope. The approach lacks any brain retraction and the use of endoscopic approach allows for little or no manipulation of the neurovascular structures [Citation35]. The classic TCAs usually make it difficult to locate critical subchiasmatic perforating arteries, which can otherwise be kept intact with the EEA [Citation26].

One more advantage is the absence of cosmetic defects with the transsphenoidal extended endoscopic approach. Finally, EEA, which is easier to tolerate, with minimal blood loss and less invasive, could be an alternative for elderly patients or patients that are otherwise not good candidates for surgery [Citation35,Citation36]. In these patients, residual meningiomas can be treated with SRT with low associated complication rates and sufficient results [Citation37,Citation38].

Despite the many advantages offered by the EEA, there are some disadvantages to take into consideration. The most well-known one is the increased risk of CSF leakage, following the removal of anterior skull base bone and underlying dura. Some authors report higher risk of CSF fistulas with EEA, than with a standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar floor [Citation35, Citation39,Citation40]. Another disadvantage of the extended approach is perhaps its own visual and control limitations while removing tumour from over the optic apparatus or lateral to and above the anterior clinoid process. We prefer using EEA for small- to medium-sized TSMs, that is, those smaller than or around 4 cm, because when TSMs grow, they tend to increase away from the visual corridor that the EEA provides [Citation35]. Lateral extension beyond the internal carotid arteries or optic nerves is considered a contraindication for EEA, as well as the presence of brain edoema, suggesting compromised subdural arachnoidal plane. In these cases, TCAs are preferred. It is also important to note that EEA has a gradual learning curve, requiring considerable anatomical skull base anatomy knowledge and transsphenoidal endoscopic surgical experience.

Conclusions

The specific location of TSMs outlines them as a unique subset of tumours. The simple algorithm proposed in the literature that was explored here aims to maximize the use of minimally invasive approaches. This algorithm can produce excellent outcomes in the surgical resection on tuberculum sella meningiomas in carefully selected cases. The presented cases exemplify the situations in which the EEA approach may be implemented to achieve the respective goals of surgery and provide the patient with the best possible outcome.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Conger AR, Lucas J, Zada G, et al. Endoscopic extended transsphenoidal resection of craniopharyngiomas: nuances of neurosurgical technique. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(4):E10.

- Jones SH, Iannone AF, Patel KS, et al. The impact of age on long-term quality of life after endonasal endoscopic resection of skull base meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(5):736–745.

- Khan OH, Anand VK, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas: the significance of a “cortical cuff” and brain edema compared with careful case selection and surgical experience in predicting morbidity and extent of resection. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(4):E7.

- Koutourousiou M, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Wang EW, et al. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for olfactory groove meningiomas: outcomes and limitations in 50 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(4):E8.

- Laufer I, Anand VK, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic, endonasal extended transsphenoidal, transplanum transtuberculum approach for resection of suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(3):400–406.

- Ottenhausen M, Banu MA, Placantonakis DG, et al. Endoscopic endonasal resection of suprasellar meningiomas: the importance of case selection and experience in determining extent of resection, visual improvement, and complications. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(3–4):442–449.

- Schroeder HW. Indications and limitations of the endoscopic endonasal approach for anterior cranial base meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6 Suppl):S81–S85.

- Hayhurst C, Sughrue ME, Gore PA, et al. Results with expanded endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas technical nuances and approach selection based on an early experience. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:662–670.

- Nanda A, Ambekar S, Javalkar V, et al. Technical nuances in the management of tuberculum sellae and diaphragma sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2013;35(6):E7.

- Magill ST, Morshed RA, Lucas CG, et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: grading scale to assess surgical outcomes using the transcranial versus transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(4):E9.

- de Divitiis E, Esposito F, Cappabianca P, et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: high route or low route? A series of 51 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3):556–563.

- Morales-Valero SF, Van Gompel JJ, Loumiotis I, et al. Craniotomy for anterior cranial fossa meningiomas: historical overview. FOC. 2014;36(4):E14.

- Ottenhausen M, Rumalla K, Alalade AF, et al. Decision-making algorithm for minimally invasive approaches to anterior skull base meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(4):E7.

- Attia M, Kandasamy J, Jakimovski D, et al. The importance and timing of optic canal exploration and decompression during endoscopic endonasal resection of tuberculum sella and planum sphenoidale meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(1 Suppl Operative):58–67.

- Banu MA, Mehta A, Ottenhausen M, et al. Endoscope-assisted endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole resection of olfactory groove meningiomas: comparison and combination of 2 minimally invasive approaches. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(3):605–620.

- Greenfield JP, Anand VK, Kacker A, et al. Endoscopic endonasal transethmoidal transcribriform transfovea ethmoidalis approach to the anterior cranial fossa and skull base. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(5):883–892.

- Kulwin C, Schwartz TH, Cohen-Gadol AA. Endoscopic extended transsphenoidal resection of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: nuances of neurosurgical technique. Neurosurg Focus. 2013;35(6):E6.

- Singh H, Essayed WI, Jada A, et al. Contralateral supraorbital keyhole approach to medial optic nerve lesions: an anatomoclinical study. J Neurosurg. 2017;126(3):940–944.

- Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau RL, et al. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal fl ap. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1882–1886.

- Zeden JP, Baldauf J, Schroeder HWS. Repair of the sellar floor using bioresorbable polydioxanone foils after endoscopic endonasal pituitary surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;48(6):E16.

- Ehresman JS, Garzon-Muvdi T, Rogers D, et al. The relevance of Simpson grade resections in modern neurosurgical treatment of world health organization grade I, II, and III meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e588–e593.

- Oya S, Kawai K, Nakatomi H, et al. Significance of Simpson grading system in modern meningioma surgery: integration of the grade with MIB-1 labeling index as a key to predict the recurrence of WHO Grade I meningiomas. JNS. 2012;117(1):121–128.

- Sughrue ME, Kane AJ, Shangari G, et al. The relevance of Simpson grade I and II resection in modern neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade I meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(5):1029–1035.

- Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Raper DM, et al. Endoscopic endonasal versus open transcranial resection of anterior midline skull base meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2012;77(5–6):713–724.

- Bassiouni H, Asgari S, Stolke D. Olfactory groove meningiomas: functional outcome in a series treated microsurgically. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149(2):109–121.

- Gardner PA, Kassam AB, Thomas A, et al. Endoscopic endonasal resection of anterior cranial base meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(1):36–54.

- Brell M, Villà S, Teixidor P, et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy in the treatment of exclusive cavernous sinus meningioma: functional outcome, local control, and tolerance. Surg Neurol. 2006;65(1):28–34.

- Candish C, McKenzie M, Clark BG, et al. Stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy for the treatment of benign meningiomas. Int Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(4):S3–S6.

- Litré CF, Colin P, Noudel R, et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy treatment of cavernous sinus meningiomas: a study of 100 cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(4):1012–1017.

- Trippa F, Maranzano E, Costantini S, et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for intracranial meningiomas: preliminary results of a feasible trial. J Neurosurg Sci. 2009;53(1):7–11.

- Henzel M, Gross MW, Hamm K, et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy of meningiomas: symptomatology, acute and late toxicity. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182(7):382–388.

- Milker-Zabel S, Huber P, Schlegel W, et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy in the management of primary optic nerve sheath meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(3):419–424.

- Frank G, Pasquini E. Tuberculum sellae meningioma: the extended transsphenoidal approach – for the virtuoso only?World Neurosurg. 2010;73(6):625–626.

- Wang Q, Lu XJ, Li B, et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal removal of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a preliminary report. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(7):889–893.

- Couldwell WT, Weiss MH, Rabb C, et al. Variations on the standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar region, with emphasis on the extended approaches and parasellar approaches: surgical experience in 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(3):539–550.

- Kitano M, Taneda M, Nakao Y. Postoperative improvement in visual function in patients with tuberculum sellae meningiomas: results of the extended transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(2):337–346.

- Alexiou GA, Gogou P, Markoula S, et al. Management of meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(3):177–182.

- Fatemi N, Dusick JR, de Paiva Neto MA, et al. Endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole removal of craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5 Suppl 2):269–286.

- Cavallo LM, Messina A, Esposito F, et al. Skull base reconstruction in the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):713–720.

- de Divitiis E, Esposito F, Cappabianca P, et al. Endoscopic transnasal resection of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(6):E8.