Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 has disseminated rapidly, resulting in one of the most severe pandemic outbreaks in decades. Countries around the world have been working hard to acquire legislative authorization for vaccination and its subsequent distribution. However, some members of the European Union registered very low uptake of vaccines. Students in the healthcare field could act as contributors to the conflict resolution of vaccine hesitancy. This study investigated the awareness, knowledge and attitudes of Bulgarian medical, dental and pharmacy undergraduate students toward vaccines against COVID-19. In the period 24th Apr – 10th May 2021, a cross-sectional survey was conducted online. A total of 480 students answered the questionnaire form. Only 27% of the responders were negative regarding the vaccination against COVID-19. About 73% of the responders were either already vaccinated or were on the waiting list. Both groups of students believed that the type of vaccine is important, regardless of their vaccination status. Our findings demonstrate a general positive attitude of Bulgarian medical university students toward coronavirus vaccination. The barriers to vaccinations were mainly related to concerns related to the effectiveness of the vaccines consistent with studies in other countries. Government authorities must oppose barriers to vaccination by introducing pro-vaccination campaigns with the help of a multidisciplinary approach in higher education. Thereby, the positive attitudes of medical students can be successfully formed and further increased. This could be utilized to increase the public trust in the immunization process, which would help to oppose the spread of disinformation.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2, or coronavirus (COVID-19), pandemic has aggressively spread around the world, leading to one of the most serious human pandemic cases in decades [Citation1]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the virus has spread all over the world, and as of 17th September 2021, it has caused 4,666,334 deaths worldwide [Citation2]. Countries have been rushing to develop and receive governmental approval for the distribution and vaccination of their residents [Citation1]. As reported by Strizova et al. (2021) the vaccination against COVID-19 may not result in disease elimination but will very surely reduce disease-related mortality and morbidity [Citation3]. The pressing necessity for vaccines has put a lot of pressure on developers and regulators to guarantee the quality, efficacy and safety of the COVID-19 vaccines by responsibly adapting to allow for a more rapid assessment and licensure without compromising the evaluation [Citation4]. European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued guidance for medicine developers to aid in the development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as marketing and post-authorization guidance [Citation5]. By the end of 2020, the first vaccines to complete the phase 3 trial, were authorized and distributed around the world [Citation6,Citation7].

Vaccine development has traditionally been a process that takes at least 10-15 years on average, and the expedited development of vaccines against COVID-19 created obstacles to communicating their safety and efficacy [Citation8]. Over 300 vaccine candidates are now under development in pre-clinical or clinical settings on several different platforms around the world [Citation9]. Vaccines based on viral vectors and proteins, genetic vaccines and attenuated vaccines have been the main types of vaccines tested in clinical trials up to this point [Citation3]. COVID-19 vaccine developers were able to reach Phase I clinical studies in 65 days due to RNA and vector-based vaccines, which were already in clinical development for several other purposes [Citation10]. Currently, the European Commission has given four conditional marketing authorizations for the vaccines developed by BioNTech and Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca/Oxford, and Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Three other vaccines, developed by CureVac, Sanofi-GSK and Novavax are at different stages of assessment by EMA. As of 10 September 2021, 72.1% of the European adult population is fully vaccinated against COVID-19. With over 70% fully vaccinated adults, the European Union (EU) has reached a significant milestone [Citation11].

However, some members of the European Union registered very low uptake of vaccines. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Bulgarian unified information portal [Citation12], from the first case on 8th March 2020 until the time of writing this paper (November 2021), there have been 668 363 confirmed cases in Bulgaria. For the past year and a half Bulgarians have witnessed three major outbreak waves during which the SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in 26 985 deaths. Bulgaria’s vaccination program began in late December 2020, and almost a year later, just 25% of the population was fully vaccinated. Although there are four approved and available vaccines, the interest is poor and the vaccination rate is low [Citation2].

According to researchers from the USA, the overall percentage of vaccination hesitancy among 19,991 students and trainees in the healthcare field worldwide was 18.9%, a rate similar to that in practicing healthcare providers [Citation13]. One of the main obstacles to tackling the COVID-19 pandemic is disinformation about vaccines and the immunization process. One out of every ten Indian medical students were found to be hesitant of the vaccine due to concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy, a lack of awareness about their eligibility for vaccination, and a lack of trust in government agencies [Citation14]. Only 1.26% of Pakistani students believed the vaccine formula may not be as effective as other well-tested vaccines because it was prepared in a short time and only 16.4% believed in conspiracy theories [Citation15]. Long-term complications are the most common concern among medical and non-medical students in Poland, followed by fever and malaise in medical students, as opposed to conspiracy theories in non-medical students. Conspiracy theorists can be both medical and non-medical students; for example, both groups express similar concerns about the link between vaccination and autism [Citation16]. The claim that COVID-19 vaccination can cause infertility was rejected by 54.6% of Jordanian students [Citation17].

The attitude and motivation of patients to make a change in their lifestyle are influenced by the health-related behavior of health professionals, since the most powerful predictor for advising patients on prevention matters is when health professionals themselves practice healthy behavior [Citation18]. Vaccine hesitancy refers to the refusal or delay in accepting a vaccine despite the availability of vaccination services and anti-vaccination involves the attitude and behavior against vaccines, which may be due to exacerbation of vaccine hesitancy [Citation19,Citation20]. This poses a significant risk and has been identified as one of the top ten global health threats [Citation21]. There is a strong association between healthcare professionals’ vaccine knowledge and attitudes and vaccine recommendations to their patients, according to studies. Those who are vaccine-hesitant can erode trust and contribute to the global health threat [Citation22]. In France, almost one-third of students in their final year of study feel inadequately prepared to deal with communication of vaccine hesitancy [Citation23].

Students in the healthcare fields, particularly medicine, pharmacy and dentistry, but not limited to these, may play a critical role in the conflict of vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination movement. Healthcare professionals are the most credible source of vaccine information, and students, as future healthcare providers, can also be included in this group. Therefore, it is essential to understand medical university students’ awareness, knowledge and attitudes toward vaccination. Medical, pharmacy and dentistry students can be role models of a healthy lifestyle in their communities. They might be faced with the task of consulting vaccine-hesitant people and anti-vaxxers, which will only be possible if the importance of vaccines is emphasized during their studies at the respective universities [Citation24,Citation25].

This study aimed to investigate the awareness, knowledge and attitudes of Bulgarian medical, dental and pharmacy undergraduate students toward vaccines against COVID-19 and to discuss the results in the light of similar studies in other countries, as this is the first study of such type conducted in Bulgaria.

Materials and methods

In the period from 24th Apr to 10th May 2021, a cross-sectional survey was conducted online among medical university students in Bulgaria. A total of 480 medical university students completed the questionnaire form. The online questionnaire collected socio-demographic characteristics, attitudes, risk perceptions and beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy, rejection and acceptance were determined by the self-reported views of students. The questionnaire was prepared using evidence from prior studies on vaccine acceptance by students performed in other countries [Citation1, Citation13–17, Citation22–30]. The questionnaire was distributed online via Google forms. No financial or any other reward was offered to students who completed the survey. There was no control group, as all participants in the study completed the same survey.

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software v.25. Chi-square analysis with two variables was performed. Differences were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. Independent Sample T-test was used to compare the differences in the attitude of vaccinated vs. unvaccinated students.

Results and discussion

Published studies on vaccination acceptance amongst medical universities students in other countries

Many studies published results regarding the vaccination acceptance amongst medical and other students for other countries. The overall acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine in the Czech Republic among university students was 73.3%. The COVID-19 vaccines were most readily accepted by sixth-year healthcare students, whereas first-year students had the most hesitancy [Citation29]. The year of study affects the willingness to get vaccinated among medical students in Poland: the median year of study for students who wanted to get immunized as early as possible was year three [Citation16]. About 22.5% of dental students from 22 different countries were hesitant about taking the vaccine, and 13.9% completely rejected it. According to the same study, interns were the least accepting, while fifth-year students were the most accepting; clinical students, on the other hand, were far more accepting than pre-clinical students [Citation28]. Nearly half of the Egyptian medical students were hesitant but despite their hesitation, most respondents (71%) plan to vaccinate [Citation30]. More than a third of medical students were hesitant about COVID-19 vaccination, according to a study conducted in Turkey [Citation27]. In Romania, when compared to their colleagues, medical students are more likely to support vaccination (91.9% vs. 81.9% of those in dental medicine, 77.1% of those in pharmacy) [Citation24]. In Jordan, 34.9% had a positive attitude toward their decision to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while 39.6% had a negative attitude and 25.5% did not rule out the possibility [Citation17].

An Italian study did not find a statistically significant difference between the responses of healthcare students and those from non-healthcare students; 86.1% of students reported that they would choose to have a vaccination for the coronavirus [Citation26]. In comparison with Poland, we can observe that most students expressed a desire to be vaccinated, with medical students being more likely than non-medical students to do so (91.99% vs. 59.42%) [Citation16] Czech and Pakistani healthcare students were almost twice as likely as non-healthcare students to accept the vaccine [Citation25, Citation29]. The main sources of information for medical students from Egypt concerning COVID-19 were social media, scientific websites and healthcare providers; magazines and newspapers were the least popular [Citation17, Citation30].

Results from the study amongst Bulgarian medical university undergraduates

A total of 480 students from all medical universities in the country responded to the survey. The mean age of the responders is 22 years (min. 18-max. 38 years). About 83% of them study medicine. Detailed description of the cohort is shown in .

Table 1. Description of the sample.

Additionally, our survey sought to obtain information about the vaccination status of the participants. The findings revealed that 27% of the responders were negative regarding the vaccination against COVID-19. More than 70% of the responders were either already vaccinated or were on the waiting list. This rate corresponds with the rates reported for the medical students from the Czech Republic (73.3%) [Citation29], while the acceptance rate amongst the medical university students in Poland and Romania are significantly higher (91.99% and 91.9% respectively) [Citation16, Citation24]. The acceptance rate for some non-EU countries was reported very low (i.e. 34.9% in Jodan and Egypt [Citation17, Citation30]). A significantly higher percentage of COVID-19 vaccines acceptance amongst medical students in Bulgaria in comparison with the general population could be explained with the medical background and related knowledge as well as with the university educational activities and vaccination campaigns [Citation31–42].

Other interesting findings from our frequency analysis show that 9% of the responders did not recognize vaccines as an effective tool for overcoming the pandemic. Additionally, 9% believed that vaccines could lead to infertility and 25% were neutral. About 66% of the responders rejected the claim that COVID-19 vaccination can lead to infertility, which is higher than the medical students in Jordan − 54.6% [Citation17]. Only 7% believed that vaccines can cause Alzheimer’s, autism or other illnesses, which corresponds with the results from the study in Poland [Citation16]. About 40% of the responders did not believe that the vaccines protect them from infection. Only 4% of the medical university students believed that COVID-19 vaccines could permanently alter their DNA ().

Table 2. Likert’s scale assessments.

The results of the chi-square analysis (Х2 =11, (df = 2), р = 0.981) did not show a statistically significant difference between the percentage of vaccinated and unvaccinated students by their field of study, i.e. the decision to vaccinate was not influenced by the type of specialty (). On the contrary, there was a statistically significant difference (Х2=44, (df = 5), р=0.001) between the percentage of vaccinated and unvaccinated students and the year of study. Those who were the most proactive in terms of vaccination were the students in the third and fourth years of study. This could be due to the fact that the students in the pre-clinic are not so familiar with the situation in the hospitals (while studying online), while 3rd and 4th-year students spend part of their study in the hospitals and therefore have been vaccinated.

Table 3. Vaccinated/unvaccinated students per specialty, year of study and gender.

There was not any statistically significant difference (Х2=3, (df = 2), р=0.99) between the percentage of vaccinated and unvaccinated male and female respondents, i.e. the decision to vaccinate was not influenced by gender. The type of vaccine was important for 301 (63%) of the students. About 67% of the responders preferred RNA vaccines and 201 (42%) of them had had COVID-19. However, only 8% of the responders had decided not to get vaccinated because they had already had COVID-19, whereas 74% of them would recommend vaccination to another person ().

Both groups of students believed that the type of vaccine is important, regardless of whether they had been vaccinated or not. There was a statistically significant difference between the attitudes of vaccinated and unvaccinated students toward the particular type of vaccine (Х2=119, (df = 2), р=0.001).

Similarly, about 40% of unvaccinated students and 23% of the vaccinated students declared that the type of vaccine is of importance to them (Х2=105, (df = 2), р=0.001). Interestingly, preferences in both groups favored the vector vaccines (67%), whereas RNA vaccines were preferred among 14% of the students ().

Table 4. Preference on the type of vaccine.

Additionally, Independent Sample T-test was used to check the differences in the attitudes of vaccinated vs. unvaccinated students ( and ). In general, results revealed that unvaccinated students considered vaccines as inefficient tool to combat the pandemia in contrast with the vaccinated students (t = 10, (df(471), p < 0.001). More specifically, differences in both groups showed contrast in popular belief-related statements that circulate in Bulgarian society. For example, unvaccinated students considered coronavirus vaccines as dangerous (t = 9, (df(470), p < 0.001), leading to infertility (t = 7, (df(468), p < 0.001) or causing illnesses such as autism and Alzheimer (t = 7, (df(468), p < 0.001). They disbelieved the fact that vaccines could protect them from the infection (t = 4, (df(467), p < 0.001) and strongly supported the non-scientific conspiracy belief that vaccines would permanently alter human’s DNA (t = 7, (df(467), p < 0.001) (see ).

Table 5. Independent samples T-test (only statistically significant results).

Table 6. Comparison of attitudes by groups (vaccinated vs. unvaccinated) - descriptive statistics.

Table 7. Willingness to get vaccinated.

Surprisingly, the opinions of students in both groups showed similarities regarding statements related to the public rules and measures recommended by the national and international health authorities. Such examples are related to the obligation to wear a mask if a person is vaccinated and the certainty that vaccines protect people from coronavirus infection. More importantly, worrisome similarities were found in their opinions regarding popular myths such as the link between vaccines and infertility or other chronic illnesses, the better immunity if a person has had the disease, or that if a person has had COVID-19 further vaccination was not needed ().

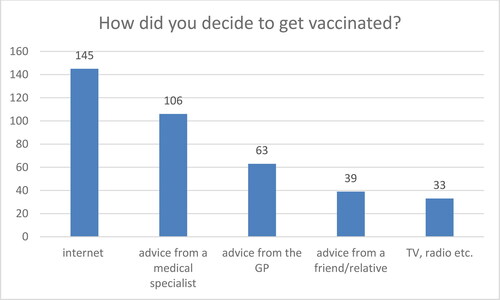

The main sources of information with relation to the decision of getting vaccinated are presented in . Other answers are too fragmented to be presented in detail but include medical education (n = 16) and results of clinical trials (n = 8).

Our study also tested the willingness and attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination based on their experience with the infection. The results revealed a solid group of students, both among survivors of the infection (30.8%) and the non-experienced responders (24%) to be unwilling to get vaccinated (X2=29.1, p = 0.001) ().

Interestingly, the opinions and knowledge about COVID-19 did not differ significantly among respondents who have had COVID-19 and those who have not (). They agreed that vaccines lead to infertility (t=-1.575, p = 0.116) and other diseases such as autism and Alzheimer (t = 2.215, p = 0.027), yet they considered vaccines to be an effective way to deal with the pandemic (t = 1.028, p = 0.305), to be rather safe (t = 0.842, p = 0.400) and to protect from the COVID-19 (t = 0.181, p = 0.857) ().

Table 8. Differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination based on students’ experiences with COVID-19.

Limitations

This study has some limitations, including an online sample with no random selection and weak generalizability.

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate a general positive attitude of Bulgarian medical university students toward immunization. Considering the level of vaccination hesitance in the general population in Bulgaria, this is an important result that indicates that medical university students are important participants in future public health campaigns and can be used in promoting vaccinations. Multidisciplinary education, pro-vaccination awareness campaigns, and focused health seminars must be introduced by government authorities to further increase the positive attitude toward vaccines amongst medical students who could be used to increase the trust of the general public in the immunization process and to counteract the dissemination of misinformation.

Conclusions

This is the first study of vaccine acceptance among university students – particularly medical students – in Bulgaria. This study highlighted that the level of acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines is relatively high − 73% and much higher than in the general Bulgarian population. The ones most proactive in terms of vaccination are the students that are in third and fourth years of study.

The level of acceptance of some conspiracy theories about the vaccines (alteration of DNA, infertility, etc.) amongst the Bulgarian medical university undergraduates is low. The barriers to vaccinations are mainly related to concerns related to the effectiveness of the vaccines, consistent with studies in other countries. The main sources of information regarding the vaccines against COVID-19 are the Internet, medical specialists and relatives. Both groups of students (vaccinated and unvaccinated) believe that the type of vaccine is important.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed significantly to this study. Conceptualization and proposal writing was done by MM. KZ supervised data collection and administrated the project. AS, DZ, KZ, MM and NB managed the data and wrote the draft manuscript. SN performed the statistical analysis, contributed to the discussion and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AS, upon reasonable request.

References

- Hafizh M, Badri Y, Mahmud S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine willingness and hesitancy among residents in Qatar: a quantitative analysis based on machine learning. J Human Behav Soc Environ. 2021;32(1):1–24.

- World Health Organization. Bulgaria: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data; 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://covid19.who.int/.

- Strizova Z, Smetanova J, Bartunkova J, et al. Principles and challenges in anti-COVID-19 vaccine development. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021;182(4):339–349..

- Wagner R, Meißner J, Grabski E, et al. Regulatory concepts to guide and promote the accelerated but safe clinical development and licensure of COVID‐19 vaccines in Europe. Allergy. 2022;77(1):72–82.

- Guidance for medicine developers and other stakeholders on COVID-19. European medicines agency. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/guidance-medicine-developers-other-stakeholders-covid-19. Accessed September 19, 2021.

- European Commission. Questions and answers: COVID-19 vaccination in the EU. European Commission - European Commission. n.d. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_2467.

- Schaffer DeRoo S, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2458–2459.

- Petousis-Harris H. Assessing the safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a primer. Drug Saf. 2020;43(12):1205–1210..

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccine tracker and landscape; 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines.

- Black S, Bloom DE, Kaslow DC, et al. Transforming vaccine development. In: Seminars in immunology. Elsevier, Academic Press; 2020. p. 101413.

- Safe COVID-19 vaccines for Europeans [Internet]. European Commission - European Commission. 2021. [cited 2021 Sep 19]. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/safe-covid-19-vaccines-europeans_en.

- COVID-19 EDINEN INFORMATSIONEN PORTAL. Ofitsialen Iztochnik Na Informatsiya Otnosno Merkite Za Borba s Razprostranenieto Na COVID-19 v Balgariya, Vklyuchitelno Zdravnite, Ikonomicheskite i Sotsialnite Posleditsi Ot Epidemiyata [COVID-19 Unified information portal. Official source of information on measures to combat the spread of COVID-19 in Bulgaria, including the health, economic and social consequences of the outbreak]. XXXX. Retrieved September 20, 2021 from https://coronavirus.bg/bg/merki/ogranichitelni-merki. (Bulgarian).

- Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, Biswas N. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in students and trainees of healthcare professions: a global assessment and call for action. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100289.

- Jain J, Saurabh S, Kumar P, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students in India. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149:E132.

- Usman J, Arshad I, Fatima A, et al. Knowledge and attitude pertinent to COVID-19 and willingness to COVID vaccination among medical students of University College of Medicine & Dentistry Lahore. JRMC. 2021;25(1):61–66.

- Szmyd B, Bartoszek A, Karuga FF, et al. Medical students and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: Attitude and behaviors. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):128.

- Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, et al. Low covid-19 vaccine acceptance is correlated with conspiracy beliefs among university students in Jordan. IJERPH. 2021;18(5):2407.

- Frank E. Physician health and patient care. JAMA. 2004;291(5):637–637.

- MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164.

- Pullan S, Dey M. Vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination in the time of COVID-19: a google trends analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39(14):1877–1881.

- Qayum I. Top ten global health threats for 2019: the WHO list. [editorial]. J Rehman Med Inst. 2019;5(2):1–2.

- Kose S, Mandiracioglu A, Sahin S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy of the COVID-19 by health care personnel. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(5):e13917.

- Kernéis S, Jacquet C, Bannay A, et al. Vaccine education of medical students: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):e97–e104.

- Bălan A, Bejan I, Bonciu S, et al. Romanian medical students’ attitude towards and perceived knowledge on COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccines. 2021;9(8):854.

- Sadaqat W, Habib S, Tauseef A, et al. Determination of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17283.

- Barello S, Nania T, Dellafiore F, et al. Vaccine hesitancy’ among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):781–783.

- Kaya MO, Yakar B, Pamukçu E, et al. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine and role of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on vaccination willingness among medical students. Eur Res J. 2021;7(4):417–424.

- Riad A, Abdulqader H, Morgado M, on behalf of IADS-SCORE, et al. Global prevalence and drivers of dental students’ COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):566.

- Riad A, Pokorná A, Antalová N, et al. Prevalence and drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Czech university students: National cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(9):948.

- Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021;93(7):4280–4291.

- Chesto zadavani vaprosi pri vaksinatsiya [Frequently asked questions at vaccination]. Medical University of Sofia. n.d. https://mu-sofia.bg/mu-sofia-covid-19/faq-pri-vaksinitsiya/. (Bulgarian)

- Kasabov B. Dezinformatsiya - COVID-19 i vaksinite. Ofitsialen sayt na Studentski savet - Medical University of Varna. 2021. https://students.mu-varna.bg/dysinformation_vaccine_covid19/.

- Meditsinski Universitet Varna MU-Varna osiguryava vazmozhnost za vaksinirane na vsichki svoi studenti, sluzhiteli/prepodavateli i tehnite rodstvenitsi [Medical University of Varna MU-Varna provides opportunity for vaccination to all its students, employees/faculty and their relatives]. 2021. Medical University of Varna. https://www.mu-varna.bg/BG/Pages/vaksini-covid-mu-varna.aspx. (Bulgarian)

- Merki pri COVID-19 [COVID-19 Measures]. n.d. Medical University of Sofia. https://mu-sofia.bg/mu-sofia-covid-19/. (Bulgarian)

- MU – Plovdiv s grizha kam studentite [MU-Plovdiv with care for students]. n.d. Medical University of Plovdiv. https://mu-plovdiv.bg/mu-plovdiv-s-grizha-za-studentite/. (Bulgarian)18.

- MU-Plovdiv v usloviyata na COVID-19 » Informatsionni materiali. [MU-Varna in COVID-19 conditions]. n.d. Medical University of Plovdiv. https://mu-plovdiv.bg/mu-plovdiv-v-usloviyata-na-covid-19/informatsionni-materiali/. (Bulgarian)

- MU-Sofia predostavi vazmozhnost za vaksinatsiya na studentite si [MU-Sofia provided opportunity for vaccination to its students]. 2021. Medical University of Sofia. https://mu-sofia.bg/mu-sofia-predostavi-vazmojnost-za-vaksinacia-na-studentite-si/. (Bulgarian)

- MU-Sofia vaksinira 55% ot prepodavatelite i sluzhitelite si [MU-Sofia vaccinated 55% of its faculty and employees]. 2021. Medical University of Sofia. https://mu-sofia.bg/mu-sofia-vaksinira-55-ot-slujitelite-i-prepodavatelrte-si/. (Bulgarian).

- Priziv za vaksinatsiya [Call for vaccination]. Priziv za vaksinatsiya [Call for vaccination]. 2021. July 9). Medical University of Plovdiv. https://mu-plovdiv.bg/priziv-za-vaksinatsiya/. (Bulgarian)

- Vaksina S. antitela ili otritsatelen PCR se dopuskat studenti v MU-Plovdiv, glasi zapoved [Students with vaccination, antibodies or negative PCR are allowed in MU-Plovdiv, according to Order]. 2021. August 22). Bulgarian National Television https://bntnews.bg/news/s-vaksina-antitela-ili-otricatelen-pcr-se-dopuskat-studenti-v-mu-plovdiv-glasi-zapoved-1166472news.html. (Bulgarian)

- SU i Covid-19 - Sofiyski universitet “Sv. Kliment Ohridski.” [SU and COVID-19 – Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski]; 2020. Sofia University. https://www.uni-sofia.bg/index.php/bul/universitet_t/su_i_covid_19. (Bulgarian)

- Zapoved na Rektora na MU – Pleven, vav vrazka s razprostranenie na koronavirus “Kovid-19 “i programite za mobilnost [Order of the Rector of MU-Pleven regarding the spread of COVID-19 and mobility programs]; 2020. Medical University of Pleven. http://www.mu-pleven.bg/index.php/bg/2019-04-30-16-14-17/285-2014-04-15-15-01-54/5476-19. (Bulgarian)