Abstract

Campylobacter infection is a serious health problem worldwide. There is still insufficient information in Bulgaria about the spread and course of the infection. Data on campylobacteriosis in adults are particularly scarce. In our study, we performed a comparative analysis in patients in different age groups, including the resistance of isolated strains. In the period 2018-2020, a total of 1,120 patients hospitalised with acute diarrhoea syndrome, aged 0-97 years, were studied, and a total of 1,120 faecal samples were examined by culture techniques and multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The antimicrobial resistance of some of the isolates was determined. A total of 385 (34.37%) isolates belonged to Campylobacter spp.: 340 (88.31%) to Campylobacter jejuni and 45 (11.68%) C. coli, respectively. The highest incidence was observed in the youngest (< 5 years of age) and the oldest (≥ 65 years of age) patients. Elderly adults are most likely to present with poor and non-specific symptoms despite the severe course of the infection. We observed severe antimicrobial resistance to tetracycline in both young children and older adults (about 40%). In older adults, we observed high resistance to ciprofloxacin. Regarding the C. jejuni strains, the resistance was 19.07% in the youngest, but it reached 59.15% in older adults. The mimicry of the symptoms in older adults can be misleading for the clinician with regard both to the diagnosis and the severity of the infection.

Introduction

Acute gastroenteritis caused by thermophilic Campylobacter spp. is a health problem in humans and animals on a global scale [Citation1]. Campylobacteriosis is the most reported food-borne infection in the European Union (EU) and has been so since 2005 according to EU One Health Zoonoses Report 2020, with an annual number of cases estimated at more than 200 thousand. Campylobacteriosis has a seasonal peak during early/mid-summer in many countries [Citation1, Citation2]. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States (US) reported Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli as the most common causes of human campylobacteriosis, especially in younger children, but also in older adults [Citation1–3]. Potential sources of infection with Campylobacter spp. are the consumption of contaminated milk, undercooked chicken and contact with pets or birds [Citation2–5]. Reports associate Campylobacter spp. with conditions ranging from acute gastroenteritis to severe post-infectious complications such as sepsis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Henoch-Schonlein purpura and other autoimmune conditions [Citation1, Citation5]. The incidence of campylobacteriosis has increased significantly in recent years. In 2020, 120,946 confirmed cases of human campylobacteriosis were reported by the 27 EU member states [Citation2]. Notwithstanding, the official reports in Bulgaria are still rare. According to ECDC data for 2019, in the group of the EU and Great Britain, Germany ranked first with over 61,254 cases and Great Britain, second with over 58,718 cases, while Bulgaria reported only 292 cases [Citation6, Citation7]. While in Germany, the most affected age group is that of adults (25–60 years of age), in Bulgaria it is children under 5 years of age [Citation6]. The cases of campylobacteriosis reported annually in the US range from 0.8 million [Citation4] to about 0.1 million [Citation8, Citation9]. According to some studies, the rate of gastrointestinal hospitalisations and deaths is highest among adults [Citation4, Citation6, Citation9].

In Bulgaria, due to the labour-intensive isolation techniques, testing for Campylobacter in patients with diarrhoea syndrome is not yet a routine procedure. This could be one of the reasons behind the limited data on the prevalence of campylobacteriosis. According to a few retrospective studies, Campylobacter spp. is one of the leading causes of diarrheal diseases and children are most affected [Citation7, Citation9].

In severe cases, especially in adults and immunosuppressed patients, where antibiotic treatment is necessary, it is severely compromised by the growing antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter isolates globally [Citation10]. The antimicrobial resistance to macrolides in the US and Europe is low in C. jejuni, but there are relatively common mutations in the 23S rRNA gene in C. coli, resulting in macrolide resistance [Citation11]. In the US there is reportedly higher resistance of Campylobacter spp. to ciprofloxacin (77.4%) than to azithromycin (4.9%) [Citation12]. Growing resistance to tetracycline, which is often overused in farm animals, is a global problem [Citation13]. Here we report our results from monitoring the incidence and clinical course of campylobacteriosis in hospitalised patients of various ages, as well as the antibiotic resistance of the studied isolates.

Subjects and methods

Statement of ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000 and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Prof. Iv. Kirov’.

Patients

This study was performed at the biggest hospital for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases in Bulgaria, the University Hospital “Prof. Iv. Kirov” in the city of Sofia, and at the National Reference Laboratory (NRL) of Enteric Pathogens at the National Centre of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases in Sofia. For the period 2018-2020, a total of 1,120 patients hospitalised with acute diarrhoea syndrome, aged 0-97 years (mean age 43.2 years) were studied. To compare the clinical course and the antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates, we divided the patients into different age groups (under 5 years, between 5 and 64 and over 65 years).

Demineralisation (dehydration) studies were also performed in hospitalised patients. In our severe patients, infants and the oldest adults, we started empirical treatment with macrolide immediately after the detection of Campylobacter.

Sample collection

A total of 1,120 diarrhoeal faecal samples were collected at the University Hospital “Prof. Iv. Kirov” in Sofia from January 2018 to mid-December 2020. Samples were collected in sterile containers, tested by rapid antigen tests, after that stored at 4 °C till transported to NRL of Enteric Pathogens for phenotypic and molecular identification.

Campylobacter detection and bacteriological examination

The presence of Campylobacter antigen was prospectively tested using enzyme immunochromatographic assay (EIA) (CerTest, Spain) at the clinic, immediately after defecation.

At the NRL, each EIA-positive faecal sample was cultured on 10% sheep blood agar (MkB Test a.s. Slovac Republic) by membrane filtration technique with 47 mm nitrocellulose membrane disks (GVS North America, Stanford, USA) at microaerophilic conditions, obtained by atmosphere generation system (CampyGenTM) in an anaerobic jar 2.5 litres (OxoidTM, UK), at 42 °C for 48-72 h. All strains obtained were identified by a biochemical test for hydrolysis of sodium hippurate and indoxyl acetate, oxidase (+) and catalase (+) and by an automated matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) system.

DNA extraction

Total DNA was extracted from the faecal samples using the PureLinkTM Genomic DNA Mini Kit (INVITROGEN, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Carlsbad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final elution volume of the obtained DNA was 75 µL. Extracted DNA samples were stored at −80 °C till multiplex polymerase chain reaction (mPCR) analysis.

Multiplex PCR assay

Multiplex PCR assays were applied for simultaneous identification and differentiation of C. jejuni and C. coli detecting conservative genes: hipO, typical of hypuricase (C. jejuni); asp, aspartokinase gene for C. coli and cadF (16SpDNA) for Campylobacter spp. The primers and their sequences are described in [Citation14, Citation15].

Table 1. Sequences of the primers and their amplicon sizes.

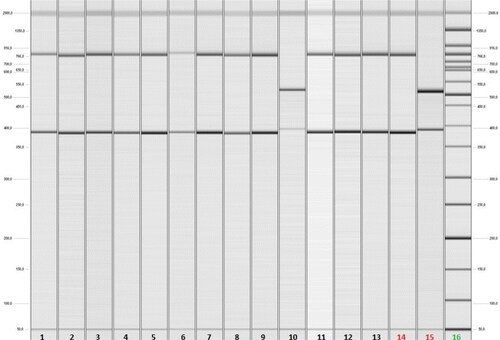

We also included two reference strains: C. coli (provided by WHO-EQAS 2016, SSI, Danmark) and C. jejuni (ATCC 33560) as positive controls for PCR analysis and ddH2O as a negative control. As previously described [Citation16], multiplex PCR was optimised to function in a final reaction volume of 25 µL with these primers and under these conditions: 1 Taq DNA polymerase buffer; 4 mmol/L MgCl2; 0.2 mmol/L dNTPs; 0.03 U/µL DNA polymerase Superhot Taq DNA polymerase (AppliChem GmbH kit, Germany); 0.6 µmol/L cadF-F/R; 0.2 µmol/L asp-F/R; 0.2 µmol/L hipO-F/R. The analysis was performed using a Real-Time PCR System (Gentier 96, TIANLONG) under the following cycle conditions: initialisation step - denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; then 35 cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, hybridisation at 52 °C for 45 s and elongation at 72 °C for 60 s; the final step was elongation at 72 °C for 2 min. The dimensions of the amplicons produced were 735 bp, 500 bp and 400 bp, belonging to Campylobacter spp., C. coli and C. jejuni, respectively. The amplicons were visualised using capillary electrophoresis (QIAxcel, DNA QIAGEN sample manual and Assay Technologies, 2008) ().

Figure 1. Results of capillary gel electrophoresis after Multiplex PCR analysis of clinical faecal samples from hospitalised patients with acute diarrhoea. Lanes 1 up to 9 and 11up to 13 - positive faecal samples for C. jejuni by detection of cadF (400 bp) and hipO (735 bp) genes. Lane 10- а positive faecal sample for C. coli by detection of cadF (400 bp) and asp (500 bp) genes. Lane 14 - C. jejuni ATCC 33560 as a positive control. Lane 15 - C. coli reference strain provided by WHO-EQAS 2016, SSI, Danmark as a positive control. Lane 16 - DNA ladder (50-2 000 kb).

Antimicrobial susceptibility screening

The antimicrobial susceptibility of the confirmed Campylobacter isolates was tested via the disc diffusion tests in compliance with EUCAST, for tetracycline (TE, 30 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 µg), erythromycin (E, 15 µg) and azithromycin (AZM, 15 µg). Classification of isolates as resistant (R) was based on criteria from the EUCAST (https://mic.eucast.org/). The tested 4 antimicrobial agents are the ones most commonly used in Bulgaria for the treatment of Campylobacter infection.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as percentages for categorical variables and as mean and median values for continuous variables. Age ranges and clinical characteristics were analysed for all studied patients with proven campylobacteriosis. Differences were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. The SPSS software package, version 11 (SPSS), was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Of 1,120 clinical faecal samples, 385 (34.37%) isolates belonging to Campylobacter spp. were obtained using bacteriological examination followed by multiplex PCR (). Of all isolates, 340 (88.31%) belonged to Campylobacter jejuni and 45 (11.68%) to C. coli. The distribution of campylobacteriosis by age group is presented in . The highest incidence of infection was observed in the youngest (< 5 years of age) and in the oldest (≥ 65 years of age), and there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.021) compared to the intermediate age group (5-64 years). The distribution of C. jejuni and C. coli was relatively uniform in the age groups.

Table 2. Distribution of campylobacteriosis among hospitalised patients at the University Hospital “Prof. Iv. Kirov” in Sofia for the studied period, 2018–2020.

Based on the clinical course of the infection, we divided the patients into the same three age groups. Diarrhoea, which is the major symptom of intestinal campylobacteriosis, occurred in 100% of the hospitalised children under 5 years of age, and the frequency was high in the group of older children and active adults (5-64 years of age) − 99.24%. In contrast to the previous two groups, in older adults (≥ 65 years of age), there were a number of hospitalised patients with proven campylobacteriosis but without diarrhoea - a total of 5% did not have diarrhoea syndrome (however, these differences were not statistically significant - p > 0.05). The incidence of bloody diarrhoea, which is a common feature of the infection, decreased with age, and only 48.75% of the older adults had hemocolitis (statistically significant difference - p < 0.038). Abdominal pain was most reported in 5- to 64-year-olds and was a relatively rare symptom in both youngest and oldest (p < 0.041). Vomiting was a relatively rare symptom in all patients. Most young children and adults were febrile, but among older adults, there was a high incidence of afebrile patients − 35% (p < 0.033). Regarding dehydration, which we detected by the degree of demineralisation by testing electrolytes in the blood, among all hospitalised patients, young children were most severely dehydrated (93.6%), followed by older adults (97.5%) ().

Table 3. Clinical symptoms in patients by age groups.

We studied the antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates from the two extreme age groups (). We observed severe resistance to tetracycline (TE) in both C. jejuni and C. coli strains in the young children group (approximately 40%). In older adults, the strains of C. jejuni resistant to TE again were about 40%, but we did not find resistance in C. coli. We also found high resistance to ciprofloxacin (CIP). Regarding C. jejuni strains, the resistance was 19.07% in the youngest, but it reached 59.15% in older adults. C. coli showed relatively low resistance to CIP. The resistance of C. jejuni to erythromycin in adults was negligible (2.81%). In children, no resistance to erythromycin was observed; there were also no isolates resistant to azithromycin. A high rate of cross-resistance of C. jejuni to TE + CIP was found in children (13.81%) and a much higher rate in older adults (26.76%). We did not find cross-resistance of C. coli or multidrug-resistant strains.

Table 4. Profiles of antimicrobial-resistant C. jejuni and C. coli isolates recovered from clinical faecal samples.

Discussion

Infection with Campylobacter continues to be a serious health issue worldwide, in terms of both morbidity and economic burden for the health systems. In 2019, the EU reported as many as 220,682 proven cases. One-third of the patients (30.2%) were hospitalised [Citation6]. With the increasing use of molecular methods in many microbiological laboratories in Bulgaria, labour-intensive microaerophilic culturing is giving way, thus increasing the frequency of specified and reported cases of campylobacteriosis. There are still only a few studies in our country regarding the prevalence and clinical characteristics of this infection, most of which are in children [Citation16, Citation17]. We have made the first attempt to systematically review the features of campylobacteriosis in different age groups, including the resistance of clinical isolates.

There are controversies in the literature with respect to the etiological treatment of intestinal campylobacteriosis. Some authors define it as a self-limiting disease that does not require antibacterial treatment in immunocompetent individuals [Citation1, Citation8]. Other authors recommend antibacterial treatment in patients with a more severe course or prognosis - hemocolitis, diarrhea for more than seven days, immunocompromised, infants or oldest adults [Citation7, Citation11].

Although diarrhoea is extremely common in children and is the second leading cause of mortality in childhood after pneumonia globally, our study shows that its incidence is very high in the oldest (≥ 65 years of age) as well. It can be concluded that campylobacteriosis is most common in the extreme age groups, which is probably due to peculiarities in the hygiene standards of nutrition in young children and older adults, especially those with severe concomitant pathology and living in social institutions, as well as due to some imperfections of systemic and local immunity [Citation16–19].

Regarding the clinical course, many authors claim that the infection is most severe in the oldest patients, followed by the youngest [Citation12, Citation17]. According to our study, older adults were less likely to show symptoms that are considered to aggravate the course, such as bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain and fever. These symptoms were relatively mild in older adults, although their general condition was often severe, with severe dehydration and demineralisation. The youngest children tended to show the most serious symptoms - hemocolitis and fever, but rarely reported abdominal pain, probably due to the fact that it is a rather subjective symptom. Severe dehydration was relatively common in all three age categories, but it was most common in the oldest, followed by the youngest. Patients with less pronounced symptoms and a low degree of dehydration are likely to be treated in an outpatient setting, thus leaving campylobacteriosis etiologically unspecified. Despite the less pronounced symptoms in older adults, in recent years hospitalisations have increased with age and the disease has become more severe [Citation1, Citation12, Citation20]. This mimicry of symptoms can be misleading for the clinician in terms of both diagnoses - especially in the absence of diarrhoea and fever, and the severity of the infection - due to the absence of hemocolitis and fever. Diagnostic problems and underestimation of the severity of campylobacteriosis are less common in early childhood.

The growing antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter is a worrying global trend. The resistance to TE is especially common due to its wide use in livestock breeding [Citation10, Citation12]. High resistance to TE has been described in Bulgaria by other authors as well, including by us in the study of isolates from children [Citation16, Citation17]. There are serious discrepancies in isolates from children and adults regarding the sensitivity to CIP. The reason behind the high resistance of strains isolated from adults is probably the fact that the treatment of bacterial intestinal infections in our country very often begins empirically with CIP, even before their etiological interpretation, and is most often performed in an outpatient setting or without medical advice [Citation7]. The approach of using antibiotic treatment in children with diarrhoea syndrome is now much less common. This study places Bulgaria among the countries in the EU with the highest incidence of resistance of strains to TE and CIP, including combined resistance.

As in other studies, we observed a rapid response in patients after the start of etiological treatment, especially if it started in the first 24-48 h after the onset of symptoms [Citation5, Citation12]. According to our studies, the disease is severe in older adults, but with atypical and protracted symptoms. This should encourage clinicians to specifically suspect Campylobacter and, if present, to initiate antimicrobial therapy.

Conclusions

Although there is still no serious enough review of campylobacteriosis in Bulgaria, this study shows a high incidence of this infection among the youngest and oldest patients. The clinical course of the infection is different in different age groups. In older adults, a severe course of the infection combined with relatively poor and non-specific symptoms is possible. This can result in serious diagnostic and therapeutic failures. The sensitivity of Campylobacter to macrolides in our country is still preserved and this gives rise to some optimism, but, in practice, there are no other available alternatives. The best approach is to use macrolides in severe infections in adults and children. Mild forms should be considered self-limiting.

Statement of ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000 and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Prof. Iv. Kirov’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement (DAS)

The data are available upon reasonable request from the author for correspondence (V.V.)

Additional information

Funding

References

- Liu F, Ma R, Wang Y, et al. The clinical importance of Campylobacter concisus and other human hosted Campylobacter species. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8(24):243.

- EFSA scientific network for zoonoses monitoring data and of the ECDC food and waterborne diseases and zoonoses network. The European Union One Health 2020 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2021;19(12):6971.

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(1):7–15.

- Szosland-Fałtyn A, Bartodziejska B, Królasik J, et al. The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in Polish poultry meat. Pol J Microbiol. 2018;67(1):117–120.

- Fitzgerald C. Campylobacter. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(2):289–298.

- Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. Available at https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx. [cited 2019].

- Ivanova K, Marina M, Petrov P, et al. Campylobacteriosis and other bacterial gastrointestinal diseases in Sofia, Bulgaria for the period 1987–2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(4):19474.

- White A, Ciampa N, Chen Y, et al. Characteristics of Campylobacter, Salmonella infections and acute gastroenteritis in older adults in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(9):1545–1552.

- Pavlova MR, Dobreva EG, Ivanova KI, et al. Multiplex PCR assay for Identification and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolates. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2016;58(2):95–100.

- Shen Z, Wang Y, Zhang Q, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6(2).

- Logue CM, Danzeisen GT, Sherwood JS, et al. Repeated therapeutic dosing selects macrolide-resistant Campylobacter spp. in a turkey facility. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109(4):1379–1388.

- Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, et al. A Meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(5):696–700.

- Padungton P, Kaneene JB. Campylobacter spp. in human, chickens, pigs and their antimicrobial resistance. J Vet Med Sci. 2003;65(2):161–170.

- Nayak R, Stewart TM, Nawaz MS. PCR identification of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni by partial sequencing of virulence genes. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19(3):187–193.

- Linton D, Lawson AJ, Owen RJ, et al. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(10):2568–2572.

- Pavlova M, Alexandrova E, Donkov G, et al. Campylobacter infections among Bulgarian children: molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2020;34(1):1038–1042.

- Boyanova L, Gergova G, Spassova Z, et al. Campylobacter infection in 682 bulgarian patients with acute enterocolitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other chronic intestinal diseases. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;49(1):71–74.

- Scallan E, Crim SM, Runkle A, et al. Bacterial enteric infections among older adults in the United States: Foodborne diseases active surveillance network, 1996-2012. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12(6):492–499.

- Ignatova D, Kamusheva M, Petrova G, et al. Costs and outcomes for individuals with psychosis prior to hospital admission and following discharge in Bulgaria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(11):1353–1362.

- Lund BM, O’Brien SJ. The occurrence and prevention of foodborne disease in vulnerable people. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8(9):961–973.