Abstract

Vaccination is one of the most powerful and affordable means in the history of public health. It is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases, as immunizations save millions of people from disease, disability and death each year. Vaccines are also now available against a number of non-infectious, autoimmune and even oncological diseases. A significant number of combination vaccines (mainly for pediatric use) have also been developed, which save parents’ time and are less traumatic for the child compared to the administration of several individual vaccines. Public healthcare authorities are involved in controlling and investigating each case of vaccine-related adverse effects or complications. Lifelong immunization (also known as life course immunization) is a process involving immunization with mandatory and recommended vaccines from birth throughout a person’s life, including vaccines that are recommended for adult patients. Better use of existing vaccines and the development of new ones are successful solutions to reduce the incidence of preventable diseases and subsequent deaths.

Introduction

Constant efforts are being made to invent new vaccines to prevent and treat significant health threats such as HIV infection, malaria and tuberculosis. The list of vaccines for human use has been growing steadily. For example, the first anticancer vaccine – the vaccine against cervical cancer – has been used since 2006 and already around 4 million doses of the two known vaccines have been administered worldwide without significant adverse effects. Although antibiotics prevent a large proportion of deaths every year and are still the main treatment option for potentially fatal bacterial infections, prescription rates related to their misuse or overuse have led to drug resistance becoming a global health emergency. It should be noted that it is much more difficult and expensive to treat antibiotic-resistant infections from which patients do not always recover. Therefore, the role of vaccines is also important in the fight against antibiotic resistance to prevent complications from vaccine-preventable diseases [Citation1–3]. Vaccine-preventable diseases can in some cases cause life-threatening complications, hospitalization, etc. Vaccination provides the longest-lasting and most effective protection against disease at any age. Vaccinating children on time is important and helps ensure that they get the protection they need as early as possible to fight diseases before they are exposed to them, but immunization is also important in adults to help promote healthy aging. We must not forget that childhood immunization does not guarantee lifelong immunity against certain diseases such as tetanus and diphtheria. Adults need booster doses to maintain immunity. Vaccinations for adults may also be recommended to protect against a disease common in adulthood (e.g. herpes zoster) [Citation4]. Adults with inadequate and insufficient vaccine types and doses in childhood may be at risk of infection from otherwise vaccine-preventable diseases and infect incompletely immunized infants with diseases such as measles, whooping cough or mumps, for example [Citation5].

Lifelong vaccination (also known as life-course vaccination) is a process that involves starting immunization with the first mandatory vaccines after the birth of a child and continuing throughout a person’s life with the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in adolescents and, later, vaccines against influenza, which are recommended for adult patients. Immunization in childhood is the necessary solid foundation for immunization during adulthood and old age. Reimmunizations (e.g. the tetanus vaccine) are also part of the lifelong vaccination process.

In the European Union, each country has its own national policy in the field of public health, including the national immunization program and vaccination scheme. Information on national vaccination schedules in EU countries can be found via European Center for Disease Control (ECDC’s) immunization schedule visualization tool (https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/). The vaccination schedules in different EU countries are similar, but not identical. Differences concern the age and the target population group (e.g. all children of a particular age or just children at risk), the type of vaccine (some ingredients may differ), the number of doses and the intervals between them and also whether the vaccine is administered alone or in combination with other vaccines. Factors explaining such differences may include disease severity, incidence rates and trends across countries, resources and structure of health care systems, political and cultural factors and vaccination program sustainability. The existence of differences between vaccination schedules does not mean that some schedules are more effective than others. Rather, different circumstances and health systems were taken into account when compiling them. The same level of protection is provided in every EU country. Vaccines in national schemes are administered according to schedules that ensure adequate protection. All EU countries recommend vaccination against seasonal influenza in the elderly and in the main risk groups [Citation6].

The EU continues to examine the possibilities of harmonizing national vaccination schemes. On 7 December 2018, the Council of Europe issued recommendations to strengthen cooperation in the fight against vaccine-preventable diseases, which included the task of exploring the feasibility of establishing a core EU immunization schedule. Together with national public health authorities in the EU, ECDC is developing an assessment. The aim is to make national vaccination schemes more compatible and to promote equal access to vaccination in the EU. As a result, problems can be solved for people moving from one EU country to another, for example adjusting to different vaccination schedules (including the number and intervals between booster doses) or missing a vaccination [Citation6]. Here, we outline some features and differences between the immunization practices in EU countries () and the Bulgarian immunization calendar ().

Table 1. Childhood vaccination schedules in the EU [Citation6].

Table 2. Recommended vaccines in Bulgaria (from https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/).

Public attitude to vaccines and trends in attitude

Despite established and time-proven benefit of vaccines to protect public health, a quite alarming trend to reducing vaccination coverage has been observed recently. The World Health Organization reported that global coverage dropped from 86% in 2019 to 83% in 2020. An estimated 23 million children under the age of 1 year did not receive basic vaccines, which is the highest number since 2009. In 2020, the number of completely unvaccinated children increased by 3.4 million. Only 19 vaccine introductions were reported in 2020, less than half of any year in the past two decades. In 2020, 1.6 million more girls were not protected against HPV in 2020, compared to the previous year [Citation7].

A major factor for continuing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases nowadays is the low immunization coverage of available effective vaccines. A survey on the importance of vaccines, their safety and effectiveness has shown that currently the highest percentage of negative responses to questions in the survey was in the European region, showing highest level of vaccination hesitancy compared with other regions [Citation8]. During the last decade, the phenomenon of vaccination hesitancy has become a worrying trend in Bulgaria as well. A study of immunization practices among parents of children up to the age of 7 years reveals a number of factors that influence the formation of vaccination attitudes: such as opinions and information from the Internet, parent forums and other sources of non-scientific information. A survey among general practitioners (GPs) shows that hesitant parents create difficulties for doctors, as well as the existence of vicious practices to avoid vaccination [Citation8].

The control of infectious diseases via vaccines in developed countries has generated anti-vaccine movements. There are emerging non-scientifically based opinions that since the incidence of diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, measles, rubella and mumps is extremely low today (precisely due to mass immunizations), vaccines are no longer necessary [Citation9]. Unfounded claims are made that vaccines may be harmful by trying to associate any ‘reaction’ following administration of a vaccine with the vaccine itself. Such claims lead to public hesitation whether to vaccinate both children and adults. There are also population groups that refuse vaccination for religious or philosophical reasons, or who believe that vaccination (as a compulsory procedure) interferes with the right to personal choice. A lot of people have doubts about the safety and efficacy of vaccines or consider that vaccine-preventable diseases are not a serious health risk. This leads to negative consequences as shown by data from several developed countries where reduction of immunization coverage has been allowed. As early as 1974, due to complication concerns, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Japan restricted the use of the pertussis vaccine, which lead to an epidemic of pertussis with 100,000 cases and 36 deaths in 1978 in the UK, 13,000 cases with 41 deaths (compared to 393 cases in 1974) in Japan and a fivefold increase in pertussis cases in Sweden in 1985 compared to 1981 [Citation9]. Another example is the outbreak of diphtheria in the former Soviet Socialist Republics (1994) with 50,000 cases (1,700 deaths). As a result of a drop in vaccination coverage to 87% in 2008, i.e. slightly below the WHO recommended minimum of 90%, a poliomyelitis epidemic recently occurred in Tajikistan [Citation9]. These examples demonstrate that infectious agents must be continuously under control to protect public health and prevent reintroduction of diseases that are considered already managed.

The negative trend of distrust and avoidance of vaccinations has become particularly prominent in Bulgaria, regarding COVID-19 vaccines as well. A study by Popova et al. from 2022 on the attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination in Bulgaria shows that only about 25% of respondents have completed a COVID-19 vaccination series and only 34% have a positive attitude to vaccination. The respondents who had a negative attitude to vaccination were 66% and half of them stated that they would not be vaccinated under any circumstances [Citation10].

WHO recognizes that the COVID-19 pandemic and related disruptions are causing overload on healthcare systems, resulting in 23 million children in 2020 being prevented from receiving their regular childhood vaccines, which is 3.7 million more than in 2019 and is definitely the highest number reported since 2009 [Citation7]. In 2020, 83% of babies worldwide (113 million) were fully vaccinated with a three-valent diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis vaccine (DTP3), providing protection against infectious diseases that have the potential to cause serious illness and injury or to be fatal [Citation7].

These alarming data, as well as the increasing popularity of anti-vaccine attitudes in society, should be addressed by well-structured immunization programs and evidence-based public awareness campaigns to be able to raise awareness of the benefits of vaccines for each individual, irrespective of their level of education. The main obstacles to vaccination should be overcome such as [Citation11]:

Communication problems: disinformation and ‘fake news’ that disrupt confidence in vaccines widen the gap in health information, calling for health education that targets people with chronic conditions.

Lack of political unity: differences in vaccination policies across EU member states, different cultural environments and health infrastructures in Europe, as well as the lack of channels/policies contributing to data sharing and investments in immunization, make it even more difficult to achieve stable levels of routine vaccination in both the region and individual countries, especially in countries with lower economic status.

Structural barriers: unavailability, surcharge costs, lack of commitment from health professionals.

Personal hesitancy in vaccination: mistrust in vaccines, uncertainty in efficacy and disinterest due to lack of health awareness and lack of communication by health professionals [Citation11].

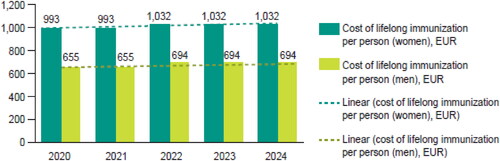

Cost-effectiveness of vaccination in healthcare systems: direct and indirect savings

Vaccination is among the most cost-effective public health interventions. According to a number of studies, no other health intervention saves more than 10 times its original cost [Citation12] or routinely provides lifelong protection against up to 17 infectious diseases (including prevention of certain types of cancer) at a total cost between EUR 328 and EUR 2,352 (vaccine costs only) and between EUR 443 and EUR 3,395 (with administrative costs included) [Citation13] for an individual’s life span (the lowest range is for a healthy middle-aged individual and the highest range is for a female patient with concomitant diseases) [Citation13].

In Europe, life expectancy is increasing and birth rates are decreasing, which inevitably leads to an ageing population. Therefore, prevention of morbidity among adult population has the potential to reduce the social and economic burden on health systems [Citation14]. It may as well be noted that protecting the health of the younger generation is not only an investment in health but also an economic investment, since national wealth naturally depends on the productivity and capabilities of young generations [Citation12]. It is therefore necessary to invest in immunization programs and seek ways of promoting available vaccines to protect the population’s life and health from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Vaccination coverage had a peak at the end of the twentieth century and its utmost peak was in 1990, and then it started to decline, especially in developing countries [Citation9]. In developing countries, about 2 million children die from vaccine-preventable diseases, despite the huge successes of immunoprophylaxis. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, approximately 40% of children are not immunized against measles, and it is one of the main causes of infant mortality in this continent [Citation9]. Significant vaccine problems in third world countries led to the establishment of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations in 2000, aimed to improve the organization of vaccinations, to expand the vaccination coverage of cost-effective vaccines, support research, development and introduction of new vaccines, especially against HIV, malaria and tuberculosis [Citation9].

Currently, WHO data show that global immunization coverage in 2020 reached the following levels:

Vaccination against pneumonia- and meningitis-causing Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) was introduced in 192 countries by the end of 2020, with a global coverage of around 70% but with great variation between regions (83% coverage in WHO South-East Asia region and only 25% in WHO Western Pacific) [Citation7].

Hepatitis B vaccine for infants was introduced in 190 WHO member states and its coverage is 83%, and 113 countries have introduced 1 dose of hepatitis B vaccine to newborns within the first 24 h of life. Global coverage is 42% and reaches 84% in the WHO Western Pacific Region and only 6% in the WHO African Region [Citation7].

MenAfriVac was introduced against meningitis serogroup A in 2010 and 11 countries had included it in their routine immunization schedule until 2020 and almost 350 million people in 24 of the 26 countries in the African meningitis belt were vaccinated [Citation7].

84% of children under 2 years of age have received a measles vaccine (1 dose); 179 countries included a second dose as part of routine immunization and 70% of children received 2 doses of the measles vaccine according to national immunization schedules [Citation7].

Mumps vaccine has been introduced nationwide in 123 countries [Citation7].

Pneumococcal vaccine had been introduced in 151 countries by the end of 2020, including 3 dose regiment in some countries, and global third dose coverage was estimated at 49%.

In 2020, 83% of infants around the world received 3 doses of polio vaccine. Poliomyelitis has been stopped in all countries (except for Afghanistan and Pakistan); until poliovirus transmission is interrupted in these countries, all countries remain at risk of importation of poliomyelitis, especially vulnerable countries with weak public health and immunization services and travel or trade links to endemic countries [Citation7].

Rotavirus vaccine was introduced in 114 countries by the end of 2020 and its global coverage was estimated at 46% [Citation7].

Rubella vaccine was introduced nationwide in 173 countries by the end of 2020, and its global coverage was estimated at 70% [Citation7].

Maternal and neonatal tetanus persist as public health problems in 12 countries, mainly in Africa and Asia [Citation7].

As of 2019, yellow fever vaccine has been introduced in routine infant immunization programs in 36 of the 40 countries and territories at risk for yellow fever in Africa and the Americas. In these 40 countries and territories, the coverage is estimated at 45% [Citation7].

The most common viral infection of the reproductive system causing cervical cancer in women, other cancers and genital warts in men and women is HPV. HPV vaccine was introduced in 111 countries by the end of 2020, although the global coverage with the final dose of HPV is only around 13% (as opposed to 15% in 2019) [Citation7].

Vaccination of girls, boys and young women prior to sexual intercourse and therefore prior to exposure to HPV infection provides an excellent opportunity to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer over time [Citation15]. As these vaccines protect against the types of HPV that cause 70% of all cervical cancers, screening vaccinated and unvaccinated women is necessary. Therefore, a comprehensive approach to the prevention and control of cervical cancer should include vaccination of girls, boys and women prior to sexual debut and screening of women for pre-cancerous lesions and treatment prior to progression to invasive disease. It should be noted that investments in HPV prevention are important for public health, as this is already a well-established cause of cervical cancer, and especially HPV types 16 and 18, which are responsible of about 70% of all cervical cancers worldwide. On average, 369 women die and 1,112 women are newly diagnosed with cervical cancer in Bulgaria every year [Citation16,Citation17]. It is also the 4th leading cause of cancer in women in Bulgaria, as well as the 2nd most common cancer in women aged 15–44 years in Bulgaria [Citation16]. According to reports of the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), about 3,000 girls are vaccinated against HPV in Bulgaria each year [Citation18]. Investment in vaccine prophylaxis has definitely paid off as cervical cancer has been shown to decrease ∼80%–90% [Citation19]. There are potential economical benefits based on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita [Citation17,Citation20] and savings from cervical cancer therapy to the amount of BGN 101,702,304.00. The average investment (payments to the Ministry of Health) amounts to BGN 322.56 (per patient) [Citation21]. In other words, as reported in a study by Petrova et al. in 2010 [Citation19], HPV vaccination is cost effective in countries with high incidence of cervical cancer, including Bulgaria. In the Bulgarian healthcare system, vaccination has the lowest cost, followed by screening and passive management [Citation19]. The cost per saved life is in line with the costs considered effective in EU member states and the benefits of vaccination in terms of reducing mortality are three times higher than the cost of each life saved [Citation19]. The study confirmed the cost-effectiveness of vaccination programs and in particular HPV vaccination in Bulgaria [Citation19] and this is just an example of vaccination savings for only one disease.

There are a number of further examples of other vaccine-preventable diseases, such as rotavirus gastroenteritis (RGE). Rotaviruses are the most common cause of severe acute gastroenteritis in early childhood and are the main cause of hospitalization due to diarrhoeal diseases. In Europe alone, RGE accounts for 231 deaths of children, 700,000 outpatient visits and up to 87,000 hospitalizations [Citation4,Citation22–24]. Despite the proven efficacy of rotavirus vaccines, 40% of European countries do not use rotavirus vaccines [Citation4]. Rotavirus vaccination reduced RGE hospitalizations by 70%–90% in children under 1 year of age. Building up herd immunity through universal rotavirus immunization is key to achieving a significant reduction in rotavirus-associated diarrhea [Citation25]. Barriers to more widespread use of these vaccines are misconceptions of low burden and low profitability [Citation4,Citation24]. Coverage with this vaccine can be improved with the help of informed healthcare professionals. It can be concluded that more than 10 years after their introduction, the benefits and acceptable safety profile of rotavirus vaccines and vaccination programs in babies have been proven by available data. Europe benefits significantly from rotavirus vaccines in terms of reducing the use of health resources and related costs for both vaccinated individuals and their unvaccinated siblings by building up group immunity [Citation4,Citation24].

In Bulgaria, 51,730 children have been vaccinated against rotavirus since April 2017. This investment (payments to NHIF, Ministry of Health) amounts to BGN 170 (per patient per year), but its rate of return is much higher, considering that due to it the incidence of RGE has decreased by ∼50%. Up to 91% of parents of children with RGE are absent from work between 2.3 and 7.5 business days to care for their child, and absence from work has been reduced due to vaccinations [Citation4,Citation22–Citation24].

The National Program for Prevention of RGE in Bulgaria aims to achieve the following results: (1) raising the level of awareness about the importance and severity of RGE, diagnosis and modern treatment of diseases, as well as about registered rotavirus vaccines and their benefits: to physicians and healthcare professionals; to parents of new-borns; (2) achieving high vaccination coverage of the target group; (3) increasing the detection and registration of RGE cases in children up to 5 years of age; (4) genotyping of rotavirus strains detected in various regions in Bulgaria; (5) improving and standardizing treatment approach in children with RGE [Citation26].

Prevention costs as part of health budgets of EU countries

There is a significant difference in healthcare costs per capita in various countries as share of GDP and trends. Overall health spending grew by 4.1% per year in real terms in OECD countries over the period 2000–2009, but it went down to 0.2% in the period 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 due to the economic crisis, as a number of countries reduced their healthcare costs to help reduce government deficits and debt, particularly in Europe. Outside of Europe, health spending continues to increase, but in many cases at a reduced rate, especially in Canada and the United States. Different areas of spending are affected in different ways: in 2010–2011 spending on medicines and prevention decreased by 1.7% and hospital costs increased by 1.0% [Citation27,Citation28].

Reducing investment in disease prevention leads to severe consequences for the health of the population. That leads to a strain on healthcare systems with higher costs for the treatment of diseases that could be avoided through vaccinations.

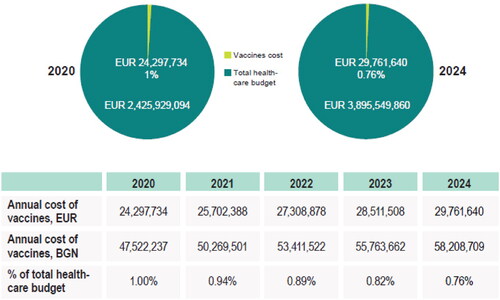

There are quite a few differences in healthcare costs in the Eastern and Western European countries [Citation29]. Germany has the highest healthcare budget in the EU (11.5% of GDP) and the highest vaccination budget, respectively. Estonia and Poland spent less than USD 5 per capita on immunization in 2015, while Iceland, Germany and Sweden spent over USD 20 [Citation12]. In contrast, in Bulgaria, only 1% of the total healthcare budget in 2020 was allocated to vaccines, with a downward trend of –0.76% estimated spending in 2024 [Citation28].

Quilici (Vaccines Europe) notes that considering that more than 20 infectious diseases can be prevented via vaccination [Citation15]; a healthcare budget for immunization of less than 0.5% (including infrastructure, education, campaigns, vaccine procurement) is quite inadequate: ‘Sustainable immunization financing is critically needed if you want sustainable and performant immunization programs’.

COVID-19 has become a threat to the health and longevity of different groups in society, such as older people and those with several comorbidities across Europe. It is a well-known fact that 25% of European adults have two or more chronic diseases, which makes vaccination vital during the pandemic [Citation11]. Yet, when it comes to routine vaccination for other diseases like influenza, the vaccination coverage in Europeans with chronic diseases is concerningly low. Less than half of Europeans with polymorbidity (45%) were vaccinated against influenza in 2018, while vaccination for pneumococcal infection is even lower and ranges between 20% and 30% [Citation11]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the main barriers affecting the uptake of routine immunization and to outline the following recommendations for stakeholders at a local, national and EU level [Citation11]:

Vaccination information must be improved. Better data-sharing on vaccination uptake and tailored information for specific chronic conditions is needed across Europe.

Engagement of local resources is needed to encourage vaccination, including healthcare professionals, local organizations and charities that need to work together to allow people with chronic conditions to get vaccinated.

Barriers to access must be removed: making vaccination free of charge, as well as improving accessibility, is vital to ensure equal access to routine vaccination.

Life-course vaccination approach means that vaccination is given through certain phases of life and prevents potential risks at a certain age [Citation30].

The Coalition for Life-Course Immunization (CLCI) was established in 2007 as a network of expert individuals made up of associations from civil society, representing public health, patients, non-governmental organizations and other advocacy groups, along with academics and health professionals from across Europe and around the world, and is committed to improving the prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases at all ages and stages of life through the promotion of health and economic benefits of wide-scale immunization. The CLCI announces in its 2020 Manifesto that it has long been recognized that vaccination is a public good. Today more than 100 million children worldwide are vaccinated annually against diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, tuberculosis, polio, measles and hepatitis B, but the Coalition participants believe that vaccines are not just for children. Vaccines are an important part of health management and well-being at all ages and stages of life and call for a holistic approach when designing vaccination programs [Citation30].

The Manifesto for 2020 of the CLCI sets out the necessary steps to ensure a sustainable approach to life-course vaccination [Citation30]:

Strong and effective leadership at all levels to implement the approach. The voice of policy and guideline makers, healthcare professionals who do vaccinations and those who receive vaccines should be heard.

Vaccination – a public good. Vaccination at all ages and stages of life must become the ‘norm’ through education and information provided through appropriate communications and platforms that strengthen individual and public benefits and make vaccinated individuals informed and demanding users.

Mobilization of healthcare professionals to reduce hesitancy and achieve optimal coverage. Healthcare professionals remain the most trusted group to convey positive messages about vaccination – they need to be involved to build public confidence in vaccination. Use social media as influencers and influencers are engaged in counteracting vaccine supporters. Social media should be used, and influencers and people with influence should be engaged in counteracting antivaccination supporters.

Innovative solutions should be developed to increase access. Vaccination at all ages and stages of life requires innovative actions to increase access for citizens by broadening opportunities to receive information about vaccines and for receiving vaccines in education, work and recreation settings.

Development of robust comprehensive data collection systems and models to support healthcare – providers and strategic decision makers who make tactical and operational decisions. Improved post-immunization monitoring, data collection and research on the benefits of the approach, including new economic models, to support effective decision-making.

Bringing all stakeholders together to ensure success. Increased vaccination coverage at all ages and stages of life requires a change in behaviour and commitment from all stakeholders, including industry, healthcare professionals, policy makers, patient groups and the general public.

Budget for prevention. Vaccination is a powerful and cost-effective primary prevention among the general population, as well as for people with chronic diseases, reducing lost working time and hospitalizations – and most important suffering and death! At a time when healthcare budgets are under strong and continuing pressure, vaccination budgets need protection [Citation30].

Vaccine costs and proportion of vaccine costs in Bulgaria’s healthcare budget (2020–2024)

Analysis of results, related to Vaccine Coverage Rate [Citation31] in Bulgaria show that healthcare investments for vaccines in Bulgaria remain relatively low ().

Despite the increased vaccination coverage of several vaccines and inclusion of a new vaccine in the National Vaccination Schedule (NVS), vaccine costs in the total healthcare budget have decreased over the 5-year analysis period ().

Increase in vaccination coverage and inclusion of new vaccines in the National Vaccination Schedule will support effective utilization of funds.

In conclusion, it should be noted that a lifelong immunization approach contributes to improving public health, supports healthcare system sustainability and promotes national economic prosperity. The European Commission not only recognizes its importance, but also recommends that it should be implemented by each member state as the only working solution for combating infectious diseases and as a method providing huge health and economic benefits. This model will help solve low vaccination coverage of preventable diseases, especially with a focus on the aging population, i.e. it will allow healthy aging of the general population and improve productivity of the working population. The Lifelong Vaccination Model is a tool to combat antimicrobial resistance, i.e. it also reduces the cost of inpatient treatment and medicines, and helps to prevent unnecessary use of antibiotics. The introduction of this new approach must be based on analyses and data, including ineffective practices and models [Citation5,Citation6,Citation32–34].

Recommendations for clinical practice: to maintain the model of mandatory and recommended vaccines, but change the operation of national immunization programs

Having in mind the low vaccination rate and all mentioned above, some recommendations could be made to the policy makers, as follows:

Transfer of budget for the National Vaccination Schedule by the Ministry of Health to the NHIF;

Recommended vaccines should be supervised, delivered, reported and paid for in the same way as mandatory vaccines, i.e. the mechanism of operation of the National Vaccination Schedule should be exactly the same as with mandatory vaccines, which will reduce the administrative burden for the general practitioners who administer vaccines and will increase their readiness to engage in the process of vaccination with recommended vaccines;

Introduction of Declaration of Paent Refusal of Recommended Vaccination in order to increase parents’ responsibility on their children’s health;

Introduction of additional providers to administer specific recommended vaccines in adolescents and adults, such as influenza vaccines, human papilloma virus vaccines and pneumococcal vaccines. Such providers who administer vaccines can be specialist physicians in obstetrics and gynaecology, pneumology and phthisiology, as well as pharmacists working in pharmacies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Galev А. Importance of vaccines to reduce antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance. Prev Med. 2018;7(2/14):4–6.

- WHO. Antibiotic resistance [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; [cited 2021 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/qa/vaccination-antibioticresistance/en.

- WHO. Antibiotic resistance: why vaccination is important. Q&A [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; [cited 2016 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/antibiotic-resistance-why-vaccination-is-important.

- Swain P. Hitting new heights: improving vaccination uptake among patients with chronic conditions across Europe [Internet]. International Longevity Centre; 2022. Available from: https://ilcuk.org.uk/hitting-new-heights-report/.

- Immunize Canada. What is immunization? [Internet]. Available from: https://immunize.ca/what-immunization.

- Shemi za vaksinatsia v darzhavite ot ES/EIP [Vaccination schedules in the EU/EEA]. Bulgarian. Available from: https://vaccination-info.eu/bg/vaksinaciya/koga-da-se-napravi-vaksinaciya/skhemi-za-vaksinaciya-v-drzhavite-ot-eseip.

- WHO. Immunization coverage [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage.

- Hadzhieva S, Pancheva P, Usheva N, et al. Prouchvane na naglasite za imunizirane I vaksinirane sred roditelite na detsa do 7 godini [study of attitudes towards immunization and vaccination among parents of children up to 7 years of age]. Pediatria. 2016;56(1):29–31.

- Argirova R. Za vaksinite i vaksinatsiyata [On vaccines and vaccination]. Sofia (Bulgaria): Bulgarian Association for Family Planning and Sexual Health (BASP); 2013.

- Popova T, Georgieva S, Blagoeva D. The vaccination process against COVID-19 – present and future. Inform Nurs Staff. 2022;54(2):33–38.

- CLCI [Internet]. Brussels (Belgium): Coalition for Life Course Immunisation. Available from: https://www.cl-ci.org/.

- UNFPA. Huge potential for economic growth requires fulfilling the promise of youth, flagship report says [Internet]. United Nations Population Fund; 2014. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/news/huge-potential-economic-growth-requires-fulfilling-promise-youth-flagship-report-says.

- Ethgen O, Cornier M, Chriv E, et al. The cost of vaccination throughout life: a western european overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(8):2029–2037.

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe – looking at the lives of older people in the EU [Internet]. Eurostat; 2019. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_looking_at_the_lives_of_older_people_in_the_EU.

- Quilici S. Realising the full value of vaccination [Internet]. Vaccines Europe - a specialised group of EFPIA. Available from: https://www.vaccineseurope.eu/news/articles/realising-the-full-value-of-vaccination.

- Human papillomavirus and related diseases report, Bulgaria [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 17]. Available from: www.hpvcentre.net.

- Natsionalen rakov registar [National Cancer Registry]. Bulgarian. Available from: https://www.sbaloncology.bg/index.php/bg/структура/национален-раков-регистър.html.

- Otcheti na Natsionalnata zdravoosiguritelna kasa [National Health Insurance Fund Report]. Bulgarian. Available from: https://portal.ncpr.bg/registers/pages/register/list-medicament.xhtml.

- Petrova G, Stoimenova A, Tsenov A. Rentabilnost na vaksinatsiyata protiv HPV. Svetovna praktika i prilozhenie za Bulgaria [Profitability of vaccination against HPV. World practice and applications]. MedInfo. 2010, 8. Bulgarian. Available from: https://www.medinfo.bg/spisanie/2010/8/statii/rentabilnost-na-vaksinacijata-protiv-hpv-svetovna-praktika-i-prilojenie-za-bylgarija-965.

- Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, et al. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human–bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):23–33.

- Preventing Cervical Cancer in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. United Nations Population Fund; 2015. Available from: https://eeca.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/21592%20UNFPA%20Cancer%20brief_web_V2.pdf.

- Gleizes O, Desselberger U, Tatochenko V, et al. Nosocomial rotavirus infection in european countries: a review of the epidemiology, severity and economic burden of hospital-acquired rotavirus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(1 Suppl):S12–S21.

- NCIPD Bulletin. Sofia (Bulgaria): National Centre for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases; 2019. Available from: https://www.ncipd.org/index.php?option=com_biuletin&view=view&month=14&year=2019&lang=bg.

- Poelaert D, Pereira P, Gardner R, et al. A review of recommendations for rotavirus vaccination in Europe: arguments for change. Vaccine. 2018;36(17):2243–2253.

- Toczylowski K, Jackowska K, Lewandowski D, et al. Rotavirus gastroenteritis in children hospitalized in northeastern Poland in 2006–2020: severity, seasonal trends, and impact of immunization. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;108:550–556.

- Natsionalna programa za control i lechenie na rotavirusnite gastroenteritis v republika Bulgaria 2017-2021 godina [national programme for control and treatment of rotavirus gastroenteritis in the republic of Bulgaria. 2017–2021]. Bulgarian. Available from: https://www.mh.government.bg/bg/politiki/programi/aktualni-programi/?page=3.

- Shefer Z, Wenger C, Messonnier M, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Paediatrics. 2014;133(4):577–585.

- OECD. Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators [Internet]. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2013 [cited 2015 Jan 13]. Available from

- Largeron N, Lévy P, Wasem J, et al. Role of vaccination in the sustainability of healthcare systems. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3:10.3402/jmahp.v3.27043.

- WHO. Working together: an integration resource guide for immunization services throughout the life course [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276546.

- Petrova E, Todorov S, Todorov N, et al. POSC67 vaccination budget trends in Bulgaria for 2020–2024. Value in Health. 2022;25(1):S99.

- Privor-Dumm L. Life-course immunization: building the consensus for adult vaccination. Switzerland: IFPMA; 2019.

- Results for Development. Immunization financing: a resource guide for advocates, policymakers, and program managers. 2017. Available from: https://www.r4d.org/wp-content/uploads/Immunization_Financing_Resource_Guide_2017_FULL.pdf.

- WHO. Global vaccine action plan 2011–2020. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; 2013. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-vaccine-action-plan-2011-2020.