Abstract

“Fake news” has emerged as a global buzzword. While prominent media outlets, such as The New York Times, CNN, and Buzzfeed News, have used the term to designate misleading information spread online, President Donald Trump has used the term as a negative designation of these very “mainstream media.” In this article, we argue that the concept of “fake news” has become an important component in contemporary political struggles. We showcase how the term is utilised by different positions within the social space as means of discrediting, attacking and delegitimising political opponents. Excavating three central moments within the construction of “fake news,” we argue that the term has increasingly become a “floating signifier”: a signifier lodged in-between different hegemonic projects seeking to provide an image of how society is and ought to be structured. By approaching “fake news” from the viewpoint of discourse theory, the paper reframes the current stakes of the debate and contributes with new insights into the function and consequences of “fake news” as a novel political category.

Introduction

“Fake news” has become a global buzzword. A simple Google search for the term literally returns millions upon millions of hits. Though misinformation and propaganda are certainly not new phenomena (Floridi Citation2016; Linebarger Citation1955) public attention towards these topics has grown exponentially in recent times. The epicentre of current debates has been the 2016 American elections where news media across the globe reported on the potential democratic problems posed by “fake news.” As The Huffington Post wrote in November 2016, “social media sites have been flooded with misinformation in the past few months” (Masur Citation2016).

The issue of “fake news” has been approached and discussed in mass media from a number of perspectives, focusing on the difficulty for users to spot fake news online (Shellenbarger Citation2016; Silverman Citation2016b), its distribution through partisan social media pages (Silverman et al. Citation2016), the responsibility of social media companies and search engines to take action against it (Cadwalladr Citation2016; Stromer-Galley Citation2016), and the underlying economic incentives for those creating it to generate advertisement revenue (Higgins, McIntire, and Dance Citation2016; Silverman and Alexander Citation2016). Some commentators have gone as far as speaking of the emergence or consolidation of a “post-factual” or “post-truth” era, in which scientific evidence and knowledge are being replaced by “alternative facts” (Norman Citation2016; Woollacott Citation2016). This trend has even been acknowledged by the Oxford Dictionaries, designating “post-truth” as the international word of the year in 2016 (Flood Citation2016).

While these perspectives on “fake news,” “post-truth politics” and “post-factuality” have provided rich explanations for these phenomena, they nonetheless tend to be locked in a very specific framework. They all seek to address the question of what can be labelled as valid, proper or “true information” online, and what should be counted as “fake news” or disinformation. Where should the boundary between true and false be drawn? And how can “fake news” be stopped? This paper takes a different approach. Instead of asking how and why “fake news” is produced, we showcase how the concept of “fake news” is being mobilised as part of political struggles to hegemonise social reality. In doing so, the paper contributes with new knowledge on the consequences of “fake news” as an increasingly ubiquitous signifier circulating within the public sphere.

Existing Research: Typologies of False Information

Within the academic literature on false information in the digital era, the large majority of research is centred around questions of how and why misleading content is produced, disseminated and accepted as legitimate. Scholars have argued that digital media provide the basis for new types of disinformation connected to so-called infostorms (Hendricks and Hansen Citation2014), infoglut (Andrejevic Citation2013) or information overload (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2011). Other researchers have provided narrower and more empirical studies focusing on topics such as misleading health information (Eysenbach Citation2008), governmentally organised propaganda (Aro Citation2016), Wikipedia hoaxes (Kumar, West, and Leskovec Citation2016) or disguised racist propaganda (Farkas, Schou, and Neumayer Citation2017, Citation2018; Skinner and Martin Citation2000).

A widely adopted and discussed terminology within the research on false information distinguishes between disinformation and misinformation. While a few scholars use these terms interchangeably (Floridi Citation1996; Skinner and Martin Citation2000), most use them to distinguish between intentional and unintentional forms of misleading information. Some scholars refer to misinformation as all types of misleading information and disinformation as only the intentional production and circulation of such information (Karlova and Fisher Citation2013; Keshavarz Citation2014; Tudjman and Mikelic Citation2003). Others use misinformation in a narrower sense to encompass only unintentional forms of misleading content, thus being the opposite of disinformation, which encompasses only intentional forms (Fallis Citation2015; Giglietto et al. Citation2016; Kumar, West, and Leskovec Citation2016). In both typologies, an example of disinformation could be a political group spreading false information in order to affect public opinion, or a website creating fake news articles in order to attract clicks (and ad revenue). In contrast, false information shared unknowingly by a social media user would be a case of misinformation. Building on this conceptual distinction, the predominant analytical questions posed within this literature concern the distinction between “truthful” and “false” information. This simultaneously implies an on-going focus on the intentionality behind the production and circulation of fake news. While these discussions are significant in their own right, they nevertheless miss part of the broader picture. In seeking to answer and describe how to properly define true and false information, scholars tacitly accept an underlying premise: namely that the question of false information or “fake news” is in fact a question of “fake” versus “true” news. To put it in the words of Presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, they accept the premise that fake news is solely a question of misleading information and “isn’t about politics or partisanship” (Clinton Citation2016).

In this article, we provide a different analysis of the rise of “fake news” as a pervasive and increasingly global signifier. Instead of entering the terrain of what defines “truthfulness” or “falsehood,” a battleground in which a multiplicity of agents struggle to define what counts as valid or deceitful, we seek to understand “fake news” as a discursive signifier that is part of political struggles. We take a step back and look at how different conceptions of “fake news” serve to produce and articulate political battlegrounds over social reality. In this regard, our goal is not to define the correct definition of fake news, but to analyse the different, opposing and conflicting understandings of the concept. We move beyond a preoccupation with the misinformation threats posed by fake news and instead ask: what does the proliferation of “fake news”-signifiers signify? What kinds of ethico-normative struggles do they bring to the foreground?

By excavating three key contemporary moments of “fake news,” we argue that the term has increasingly evolved to become what the post-Marxist philosopher Laclau (Citation2005) defines as a floating signifier. That is to say a signifier used by fundamentally different and in many ways deeply opposing political projects as a means of constructing political identities, conflicts and antagonisms. Instilled with different meanings, “fake news” becomes part of a much larger hegemonic struggle to define the shape, purpose and modalities of contemporary politics. It becomes a key moment in a political power struggle between hegemonic projects. In this way, we argue that “fake news” has become a deeply political concept used to delegitimise political opponents and construct hegemony.

We develop this argument in three stages. Starting out, we account for Laclau’s discourse theoretical conception of floating signifiers and its link to hegemonic struggles. Using this conceptual framework as our underlying theoretical lens, we proceed to analyse three competing moments in the recent production of “fake news.” We showcase how the term has been articulated in three different ways: (1) as a critique of digital capitalism, (2) as a critique of right-wing politics and media and (3) as a critique of liberal and mainstream journalism. Through this analysis, we highlight how “fake news” has gradually become a key component within hegemonic struggles to reproduce or challenge existing power struggles in civil society. Based on this small excavation, we proceed to discuss the political implications of “fake news” as a floating signifier. How can viewing “fake news” in this light help illuminate current discussions of post-factuality and post-truth?

Floating Signifiers and Hegemony

This paper takes its point of departure in post-Marxist discourse theory, particularly as it has been developed by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe as part of the so-called Essex School of Discourse Analysis (Howarth, Norval, and Stavrakakis Citation2000; Laclau Citation1990, Citation1996, Citation2005; Laclau and Mouffe [Citation1985] Citation2014). Since the publication of Hegemony and Socialist Strategy in 1985, a work sparking both controversy and breaking new theoretical ground (Sim Citation2000), a rich body of literature has emerged around discourse theory as an intellectual and philosophical project (Smith Citation1998; Torfing Citation1999). While Mouffe has particularly focused on democratic theory and radical democracy, Laclau has engaged in on-going theoretical reflections on concepts useful for understanding the construction and sedimentation of political projects. In this paper, we mainly draw on Laclau’s work as it provides a central resource for understanding the construction and fixation of meaning. Before turning to the notion of the floating signifier, central to the argumentation laid out in this paper, we will briefly describe some of the main theoretical arguments provided by Laclau.

Anchored in insights from post-structuralism, deconstruction and Marxist theory, Laclau’s work stresses the political and contingent dimensions of meaning, arguing that social reality is the product of continuous hegemonic struggles rather than innate essences or immanent laws. According to Laclau (Citation1990, Citation1996), social reality acquires its meaning through the practice of articulation in which moments are positioned relationally and differentially within a systematised totality called a discourse. The meaning of any particular moment is always relational insofar as it arises from its connection to other moments (whether textual or material). Discourse theory stresses that discourses are contingent and historical constructs, emerging through struggles and contestation over time. In privileging difference and contingency, discourse theory builds on Derrida’s ([Citation1967] Citation2016) argument that the closure of meaning always relies on exclusion and the production of a constitutive outside. Meaning, in other words, depends upon the creation of limits and the drawing of boundaries between insiders and outsiders. In this way, all discourses are based on a fundamental lack: a radical negativity that hinders their ability to fully fixate meaning (Laclau Citation1996, Citation2005). What appears as objective, neutral, or natural structures must be considered as the result of particular fixations of meaning resulting from political struggles that have repressed alternative pathways over time.

By identifying the original moment of repression as “the political,” discourse theory emphasises “the political not as a superstructure, but as having the status of an ontology of the social” (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2014, xiv, original emphasis). This means that Laclau (and Mouffe) awards a primary position to “the political” as the instituting moment in which a contingent decision is made between what is included and excluded from particular discourses. For discourse theory, the political is thereby not limited to particular expressions of the institutionalised political system but the name for the precarious and always lacking ground instituting any given discourse through acts of inclusion–exclusion. The political is not a regional category but applies to social reality in its entirety (Marchart Citation2007).

The adherence to contingency and undecidability means that Laclau eschews any attempt to approach discourses as “natural,” “normal” or “neutral.” Indeed, the core of Laclau’s political practice consists in providing a radical critique of the closure of meaning, the ideologisation of contingency and the naturalisation of domination (Schou Citation2016). Laclau’s understanding of normativity takes its point of departure in a deconstruction of the classic distinction between the descriptive and the normative, between the being and the ought (Laclau Citation2014, 127). This is a division that traces back to Kant’s separation between theoretical and practical reason, norms and facts. For Laclau, however, this distinction implodes, as meaning always relies on exclusion, and the “one” always relies on the “other”:

There are no facts without signification, and there is no signification without practical engagements that require norms governing our behaviour. So there are not two orders—the normative and the descriptive—but normative/descriptive complexes in which facts and values interpenetrate each other in an inextricable way. (Laclau Citation2014, 128)

For Laclau, as is evident in this quote, the factual can never be separated from the normative, as it is only on the basis of the normative that the factual can emerge as fact. If this is the case, and the factual is always given in relation to the normative, then this must simultaneously mean that social reality is at its core always normative. Normativity is not a regional category but applies to the totality of meaning. Laclau (Citation2014) is not invoking normativity as a universal or transcendental category given from nowhere. Norms are instead sedimented practices, signifying systems and a practical relationship to the world. To put it in Laclau’s terms, norms are always given within and through discourses that have come into being over time through practices, struggles and institutionalised conflicts (Laclau Citation1990). This is also why, according to Laclau, it is impossible to simply move or deduce certain normative orders directly from the ethical. Indeed, there cannot be established any direct relation between the ethical—as the grasping of the radical contingency of social reality—and the normative.

It is within this theoretical framework that Laclau introduces the notion of the floating signifier. This concept denotes situations in which “the same democratic demands receive the structural pressure of rival hegemonic projects” (Laclau Citation2005, 131, original emphasis). In being simultaneously articulated within two (or more) opposing discourses, a floating signifier is positioned within different signifying systems of conflicting political project. If the signifier’s meaning later appears stable or fixed, this will be the result of one particular discourse’s ability to successfully hegemonise the social, in other words winning the struggle against other discourses and repressing other forms of meaning (Laclau Citation2005). Thus, a floating signifier is not simply a case of polysemy, i.e. a particular signifier that is attached several independent meanings at the same time. Nor does it equate with what Laclau (Citation1996) terms as an empty signifier, designating the antagonistic positioning of a universalised particular signifier within a chain of equivalence. Instead, the concept is used to describe a precise historical conjuncture in which a particular signifier (lodged in-between several opposing, antagonistic, hegemonic projects) is used as part of a battle to impose the “right” viewpoint onto the world. According to Laclau (Citation2005, 132), floating signifiers first and foremost emerge in times of organic crises; historical periods in which the underlying symbolic systems are radically challenged and eventually recast. Whether the current epoch qualifies as such an organic crisis in the Laclauian sense is perhaps best left up to historians of the future to decide. However, as right-wing nationalism and protectionism sweeps over most of Europe and the United States, a certain structural and symbolic dislocation (Laclau Citation1990) does indeed seem to be present (see Jessop Citation2017 for further reflections on this issue).

Fake News—Three Contemporary Moments

Having outlined our theoretical basis, the following sections proceed to excavate three concurrent discourses in which “fake news” has been mobilised as a signifier supporting particular political agendas. The discourses have been identified based on data material published between November 2016 and March 2017. The data material consists of social media content from President Donald Trump as well as journalistic articles and scholarly commentaries published in the following American and British newspapers and magazines: The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Guardian, The Conversation, CNN, Monday Note, Business Insider, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Buzzfeed News, Mashable, Slate, Gizmodo and Time Magazine. Data sources were selected exploratorily by closely following media debates around “fake news” throughout the five-month research period and locating central actors within these debates. Subsequently, we searched through the selected sources in order to find additional content that might have been missed while following the debates. The collected data were analysed using discourse theoretical concepts in order to uncover and map emergent discourses found throughout the data. As all sources are either American or British, the identified discourses are all located within an American (and more broadly Western) political context. By showing how different and in many ways deeply opposing political actors have articulated the same signifier within diverging discourses, we are able to showcase how “fake news” has gradually become a floating signifier used within different discourses to critique, delegitimise and exclude opposing political projects. The three moments focus on “fake news” as (1) a critique of digital capitalism, (2) a critique of right-wing politics and media and (3) a critique of liberal and mainstream journalism. A fourth moment, which is not included in the analysis, includes mobilisations of the “fake news”-signifier as part of techno-deterministic critiques of digital media technologies (e.g. Facebook is bad for democracy). As our analysis specifically focuses on fake news as part of political discourses and antagonisms, the scope has deliberately been limited to the three moments presented above. These moments are approached horizontally as three simultaneous fragments of present-day political struggles to achieve hegemony. The article does thereby not seek to locate the genesis or historical origins of each of these moments or evaluate their relative dominance. Rather, we seek to examine and nuance how fundamentally opposing discourses simultaneously mobilise the “fake news”-signifier as part of political struggles.

Moment 1: Fake News as a Critique of Digital Capitalism

Misinformation in digital media is certainly not a new phenomenon (Floridi Citation1996). Nevertheless, the issue has recently gained traction in public discourse where opposing political actors have fought over its meaning and, most importantly, the explanation for its cause. Within one particular discursive construction of “fake news,” the term has been articulated as intrinsically connected to digital capitalism. Thus, a widespread explanation raised by scholars, journalists and commentators alike points to the economic structure of the Internet as the primary reason for the circulation of fake news (Filloux Citation2016; Silverman and Alexander Citation2016; Zimdars Citation2016b).

Within this discourse, it is argued that in the context of digital media, as in all commercial media, content providers generate advertisement revenue based on the amount of readers, listeners or viewers they have. Crudely put, if a website can attract a lot of visitors, the owner can potentially make money on advertisement. This economic incentive for digital content production has been highlighted as the key reason for the proliferation of “fake news.” As Professor of Communication, Papacharissi (Citation2016), for example argues, “controversy generates ratings, and unfortunately controversy is generated around facts vs. propaganda battles.” According to this discourse, false information feeds controversy and controversy feeds capital. This argumentative chain has, for example, been put forth in the work conducted by Buzzfeed News, showing that “fake” news-stories generated more engagement on social media during the American elections than “real” news stories did (Silverman Citation2016a).

A related economic explanation for the cause of “fake news” concerns the lower production costs of false information in comparison to “real news”: “Fake news is cheap to produce—far cheaper than real news, for obvious reasons—and profitable” (Zimdars Citation2016b). “Fake news” is, in other words, difficult to stop because it is linked to low production costs and potential high revenue, continuously motivating new outlets. This position is supported by articles in both The New York Times and Buzzfeed News (Higgins, McIntire, and Dance Citation2016; Silverman and Alexander Citation2016), portraying Eastern European website owners as deliberately producing “fake news” for capital gains. These fake news producers designate profit as their primary motivation and argue that high levels of user activity are the only reason why they create fake news articles concerning American elections and political system. According to this discourse, widely shared false claims about e.g. Pope Francis’ endorsement of Donald Trump or the surfacing of Barack Obama’s “real” Kenyan birth certificate were not primarily the results of partisanship but of digital capitalism. From this position, articulated by both scholars and media professionals, “fake news” is thus constructed as deeply connected and interwoven with the capitalist media economy. If “fake news” is to be eradicated, capitalist incentives and economic structures need to be reshaped too. The critique of “fake news” simultaneously becomes a critique of digital capitalism as a structure that promotes the circulation of the lowest common denominator of news content.

This discursive construction of “fake news”—as an unavoidable, negative outcome of the capitalist media economy—resembles previous media criticism of low standard in news content for the “common people.” For example, it resembles the critique of tabloid journalism, which has also been widely attacked for lowering the standards of public discourse and even posing a “threat to democracy” (Örnebring and Jönsson Citation2004, 283). The connection between “bad news content” and the capitalist media economy is in other words not new. The principal signifier used to name this connection does, however, seem to have increasingly shifted towards “fake news.” As such, “fake news” becomes the particular signifier mobilised by political actors wishing to criticise the capitalist media economy and promote publicly funded media platforms. A vivid example of this discourse can be found in an article in The New Yorker, arguing that the only long-term solution to “fake news” is increased funds to public service media, i.e. the removal of capitalist incentives (Lemann Citation2016). What we can see, then, is how the “fake news”-signifier not solely becomes a way of labelling particular outlets. It also becomes implicated in a much broader political project concerned with intervening in capitalist modes of production, promoting funding for public institutions and critiquing the cultural implications of the capitalist system. In this sense, “fake news” becomes part of a systemic critique of (digital) capitalism. Capitalism is rotten, this line of reasoning goes, and “fake news” is yet another example of its detrimental consequences.

Moment 2: Fake News as Critique of Right-Wing Politics and Media

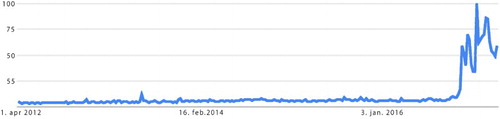

During the 2016 American elections, the term “fake news” went from being marginal to near ubiquitous. As a Google trend search reveals (), the circulation of the concept took off just before the Election Day and reached a peak around Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th President of the United States (Google Citation2017a).

This pattern is no coincidence, as the term was mobilised to critique and delegitimise political opponents from the outset, acting as a key component in a political power struggle between the American left and right. In Google’s search history, this is evident from the fact that both Americans and users worldwide predominantly coupled their searches for “fake news” with searches for “Trump CNN fake news” (i.e. a mainstream media platform) and “Breitbart News” (i.e. a right-wing media platform) (Google Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

In this context, one prevalent discourse has sought to mobilise “fake news” by connecting it to the right-wing of the American political spectrum. This position, establishing right-wing partisanship as the primary cause of “fake news,” has been articulated by a number of different scholarly and journalistic actors. A prominent example dating back before the proliferation of the “fake news”-signifier is an opinion letter in The New York Times written by Professor and Nobel Prize Winner in Economy, Paul Krugman:

… in practice liberals don’t engage in the kind of mass rejections of evidence that conservatives do. Yes, you can find examples where “some” liberals got off on a hobbyhorse of one kind or another, or where the liberal conventional wisdom turned out wrong. But you don’t see the kind of lockstep rejection of evidence that we see over and over again on the right. (Citation2014)

At the same time as these “fake news”-lists started to circulate, Gizmodo magazine ran a widely shared article claiming that Facebook did in fact have various solutions to the “fake news”-problem but avoided to instil them during the American elections due to “fear of conservative backlash” (Nunez Citation2016). This article played directly into the discursive connection between “fake news” and the American right. The claims put forth in the article were based on anonymous sources from Facebook that were quickly denounced by officials from the company (Heath Citation2016). As Slate journalist, Will Oremus, duly noticed, the story thereby became “an epistemologically fascinating case in which Facebook is claiming that a news story about its efforts to crack down on false news stories is, in itself, a false news story” (Oremus Citation2016a).

By unpacking this second discursive position, we can see how media corporations, scholars and liberal figures all (re)produce a significantly different conception of “fake news” than that provided by critiques of digital capitalism. Instead of linking “fake news” to economic incentives and structures of the capitalist system, this second political project seeks to couple “fake news” with the American right-wing, particularly Donald Trump and his supporters. “Fake news,” within this discourse, becomes intrinsically linked to right-wing politics, implicating that the solution to the “fake news”-problem has to be found in the battle against right-wing media corporations and politicians. In December 2016, Oremus addressed this issue head-on in another Slate article. As he critically wrote, “some in the liberal and mainstream media” have begun to “blur the lines between fabricated news, conspiracy theories, and right-wing opinion by lumping them all under the fake news banner” (Oremus Citation2016b). This, Oremus argued, had sparked a counter-reaction where Trump supporters attacked the very same liberal and mainstream media by designating them as “fake news.” As became clear, this discursive counter-attack was not limited to Trump supporters but went all the way to the newly elected President himself and his (now former) White House Chief Strategist, Steve Bannon, the former executive chair of the designated “fake news” platform, Breitbart News.

Moment 3: Fake News as Critique of Liberal and Mainstream Media

Trump had not even been in office for a single full day before he declared that he had “a running war with the media” (Rucker, Wagner, and Miller Citation2017). Prior to this, Trump had insinuated that the term “fake news” was a political construct created in order to attack and delegitimise his presidency. On 11 January 2017, Trump wrote on Twitter: “FAKE NEWS - A TOTAL POLITICAL WITCH HUNT!” (Citation2017a). Soon after, he began what would become a continuous and highly systematic use of the “fake news”-signifier in reverse. He used it to attack and delegitimise what he saw as his direct opponents: mainstream media. Trump started using the term to lash out at media companies such as CNN (Trump Citation2017b), The New York Times (Trump Citation2017c) and Buzzfeed News (Trump Citation2017d), all of whom had previously brought stories linking “fake news” to the American right and Donald Trump. Trump, in other words, attempted to rearticulate and re-hegemonise the term by situating it in a fundamentally opposing discourse, linking “fake news” intimately to mainstream media platforms:

“The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!” (Trump Citation2017f)

Within this discourse, fake news is constructed as a symptom of a fundamental, democratic problem, namely that mainstream media companies are biased and deliberately attempting to promote liberal agendas instead of representing “The People.” This discourse is not new, as right-wing media platforms have long claimed that “mainstream media” is corrupt, liberally biased, systematic liars, and in need of replacement (Berry and Sobieraj Citation2014). Two platforms long promoting this discourse are Breitbart News and InfoWars, both of which hosted exclusive interviews with Donald Trump during the American elections. Within this discourse, mainstream media and their “endless propaganda” will soon be replaced due to digital media, allowing Americans to communicate and become “aware that we don’t need the mainstream media to define what reality is for us after all” (Snyder Citation2014). “Fake news” thus became a key signifier in an already existing discourse promoted by right-wing media platforms and President Donald Trump: “Don’t believe the main stream (fake news) media. The White House is running VERY WELL. I inherited a MESS and am in the process of fixing it” (Citation2017e). Within this discourse, the signifier represents the exact opposite of what it did within the previous one. “Fake news” is made equal to mainstream media. In March 2017, Trump elaborated on this position:

The country’s not buying it, it is fake media. And the Wall Street Journal is a part of it … I won the election, in fact I was number one the entire route, in the primaries, from the day I announced, I was number one. And the New York Times and CNN and all of them, they did these polls, which were extremely bad and they turned out to be totally wrong. (Time Staff Citation2017)

Consequences and Implications—An Organic Crisis?

Let us recall Laclau’s important suggestion that “the ‘floating’ dimension becomes most visible in periods of organic crisis, when the symbolic system needs to be radically recast” (Citation2005, 132). Are we witnessing, we should ask, the birth of an organic crisis? And if we are, is “fake news” then the cause or outcome of this crisis? Can we use the sudden emergence of “fake news” as a floating signifier, deployed as a part of a political struggle, as a tool for diagnosing the present time? To address this question, we should proceed cautiously in considering the implications of the exposition provided above. If, indeed, “fake news” has gradually become a floating signifier, then what are the consequences of this? Both politically, but also for future research.

The least radical answer to this question might simply be that what we are observing is a gradual pluralisation of fake news. While the concept used to signify a set of more or less confined phenomena, opposing discursive positions now use it to criticise and name a heterogeneous array of events. This can, in other words, be described as a situation in which different political projects seek to define the meaning and conditions of what should be termed as “fake.” Within this line of reasoning, the proliferation of the “fake news”-signifier might not signify anything radical but simply remind us that this concept—as with for all other discursive moments—has no meaning exterior or prior to discursivity. The term can, in other words, mean different things in different contexts.

While there is undoubtedly some truth in the above position, it nonetheless fails, in our view, to capture the proper significance of the transformation of “fake news” into a floating signifier. More than simply a gradual pluralisation or growth in signifying complexity, we argue that the de-fixation of fake news has significant implications and consequences. In this context, we should remember that while “fake news” may be seen as multiple and contingent from the outside, within each of its particular usages this is not necessarily the case. From the viewpoint of the anti-capitalist or the Trump-camp, “fake news” does not denote a floating signifier. It is instead used very deliberately within a specific hegemonic project. And likewise, from the perspective of the established mass media, the label of fake news is not simply accepted as lodged in-between several opposing and contingent project. Each of the discourses holds their own distinct worldview, which does not translate unaltered across hegemonic projects. From each of these projects, “fake news” does not float. It only starts floating when considered in its relational dynamism, as showcased in this article.

In this regard, it is important to remember how the floating signifier not solely encompasses a pluralisation of meaning (Laclau Citation2005). From a discourse theoretical perspective, it implies the articulation of fundamentally different hegemonic projects. In this way, the pluralisation of “fake news” suggests that it has become the centre of contemporary political struggles, used as a discursive weapon within competing discourses seeking to delegitimise political opponents. In the case of President Donald Trump, this becomes vividly clear. Trump’s use of the term not only serves to construct himself within a particular hegemonic project. In an equally radical manner, it simultaneously seeks to delegitimise critical journalists. It is precisely by labelling these as “fake news” that he seeks to invalidate their position within the field of power, deconstruct their public authority and re-hegemonise their position. “Fake news” is meant as a frontal attack on traditional core values of journalistic practice, such as critical investigations of those holding power. In this way, the gradual transformation of “fake news” into a floating signifier comes to represent a power struggle between the journalistic field and the political field. What is ultimately at stake within this struggle is who obtains the power to define what is deemed as truthful, who can portray social reality accurately, and in what ways. In this sense, there is a partial attempt at recasting the existing symbolic systems, of overthrowing one particular hegemony in favour of another. So perhaps we are, indeed, seeing the emergence of an “organic crises”—a period in which the pre-existing symbolic structures no longer seem to hold any validity.

Contemporary descriptions of “post-truth” and “post-factual” democracy partially bear witness to this potentially emerging crisis. What the “post-factual” diagnosis attempts to describe is the overcoming or neglect of truth, scientific knowledge, and evidence in the current epoch. Notions of post-factuality and post-truth thus seem to point to the current dislocation or representational crisis in which the existing discourses are no longer deemed applicable or valid. Yet, in attempting to provide a description of the current state of affairs, the prophets of the post-factual enter into the very same terrain as that which they seek to describe. Rather than simply describing the current era, the post-factual diagnosis is a deeply normative discourse concerned with how society, democracy and truth “should” be defined. In this way, those seeking to define and understand the “post-factual” and “post-truth” era become part of the hegemonic struggles instituted by the floating character of “fake news.” Post-factual and post-truth both become a testimony of the potential organic crisis and a stake in the battle to produce new modes of representation.

The discourse theoretical approach applied in this article challenges these descriptions on multiple fronts. Instead of entering into the battle of what may be counted as valid information, we have instead foregrounded the contextual, historical and political conditions for the emergence of such claims of validity in the first place. Rather than arguing that truth no longer matters within politics, we have applied a perspective that showcases how negotiations about what may be counted as truthful are in and of themselves part of a political struggle to hegemonise the social. In doing so, we can begin to see that the turn towards an era in which facts “do not matter” might instead be a turn towards an era in which the concept of factuality is centre of discursive struggles. This may even be labelled as a hyper-factual era concerned obsessively with defining what is and counts as factual, and what counts as false. Through the circulation of labels such as “fake news,” entangled in multiple and oftentimes opposing hegemonic projects, it is the floating character of truth that should be foregrounded, not its ultimate withdrawal or vaporisation.

This also implies that any attempt to categorise, classify and demarcate between “fake” and “true” must be a deeply political practice, whether conducted from the context of journalism or academic interventions. It is part of larger political struggles to define the current shape and modality of contemporary society. Future research might begin to unpack and further develop this politics of falsehood by attending to how conceptions of “fake news” and “factuality” serve to carve out the stakes of current political crises. Accounts of the broader social, political and journalistic consequences of “fake news” might do well to consider the highly politicised and hence precarious character of the term. And systematic empirical investigations remain vital in this respect: both in terms of exploring the historical roots of the discourses excavated in this article, but also by tracing the circulation of different “fake news” discourses across cultural and political boundaries. Research would do well to examine how particular discourses come to partially dominate and silence other (subaltern) voices. What kinds of power relations do these representations serve to produce and consolidate?

For scholars, journalists and citizens alike, primacy should in all cases be given to the political dimensions of labels such as “fake news.” Instead of simply lamenting and condemning the spread of false information, research might try to explore and understand how and why such information gains traction. Is it because it resonates and reproduces already existing fears and doubts (Farkas, Schou, and Neumayer Citation2017, Citation2018)? Or does it testify to the deep-seated organic crises facing our contemporary society? Is there a need to recast and produce new political imaginaries that can fascinate, repulse and rebuild political collectivities? These are some of the central questions that future research on the politics of falsehood can hopefully uncover.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johan Farkas

Johan Farkas is a PHD Fellow at Malmö University. His research interests include political participation and disguised propaganda in digital media.

Jannick Schou

Jannick Schou is a PhD fellow at the IT University of Copenhagen. He is part of the research project “Data as Relation: Governance in the age of big data” funded by the Velux Foundation and conducts research on digital citizenship, discourse theory and political struggles. Email: [email protected]

REFERENCES

- Andrejevic, Mark. 2013. Infoglut: How Too Much Information Is Changing the Way We Think and Know. New York: Routledge.

- Aro, Jessikka. 2016. “The Cyberspace War: Propaganda and Trolling as Warfare Tools.” European View 15 (1): 121–132. doi:10.1007/s12290-016-0395-5.

- Berry, Jeffrey M., and Sarah Sobieraj. 2014. The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cadwalladr, Carole. 2016. “Google, Democracy and the Truth about Internet Search.” The Guardian, December 4. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/dec/04/google-democracy-truth-internet-search-facebook?CMP=share_btn_tw.

- Clinton, Hillary. 2016. “What to do About Viral ‘Fake News’.” CNN, December 11. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://money.cnn.com/video/media/2016/12/11/how-can-journalists-discredit-fake-news.cnnmoney/index.html.

- Delgado, Arlene J. 2015. “20 Reasons Why It Should Be Donald Trump in 2016.” Breitbart News, October 22. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.breitbart.com/big-government/2015/10/22/20-reasons-donald-trump-2016/.

- Derrida, Jacques. (1967) 2016. Of Grammatology. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Eysenbach, Gunther. 2008. “Credibility of Health Information and Digital Media: New Perspectives and Implications for Youth.” In Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility, edited by A. J. Flanagin and M. Metzger, 123–154. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Fallis, Don. 2015. “What Is Disinformation?” Library Trends 63 (3): 401–426. doi:10.1353/lib.2015.0014.

- Farkas, Johan, Jannick Schou, and Christina Neumayer. 2017. “Cloaked Facebook Pages: Exploring Fake Islamist Propaganda in Social Media.” New Media & Society. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1461444817707759.

- Farkas, Johan, Jannick Schou, and Christina Neumayer. 2018. “Platformed Antagonism: Racist Discourses on Fake Muslim Facebook Pages”. Critical Discourse Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/17405904.2018.1450276.

- Feldman, Brian. 2016. “Here’s a Chrome Extension that will Flag Fake-News Sites for You.” New York Magazine, November 15. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://nymag.com/selectall/2016/11/heres-a-browser-extension-that-will-flag-fake-news-sites.html.

- Filloux, Frederic. 2016. “Facebook’s Walled Wonderland Is Inherently Incompatible with News.” Monday Note, December 5. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://mondaynote.com/facebooks-walled-wonderland-is-inherently-incompatible-with-news-media-b145e2d0078c#.v0txzx82e.

- Flood, Alison. 2016. “‘Post-Truth’ Named Word of the Year by Oxford Dictionaries.” The Guardian, November 15. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/nov/15/post-truth-named-word-of-the-year-by-oxford-dictionaries.

- Floridi, Luciano. 1996. “Brave.Net.World: The Internet as a Disinformation Superhighway?” The Electronic Library 14 (6): 509–514. doi:10.1108/eb045517.

- Floridi, Luciano. 2016. Fake News and a 400-year-old Problem: We Need to Resolve the “Post-Truth” Crisis.” The Guardian, November 29. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/nov/29/fake-news-echo-chamber-ethics-infosphere-internet-digital.

- Giglietto, Fabio, Laura Iannelli, Luca Rossi, and Augusto Valeriani. 2016. Fakes, News and the Election: A New Taxonomy for the Study of Misleading Information within the Hybrid Media System. Convegno AssoComPol 2016.

- Google. 2017a. Google Trends – “Fake News” (globally). Accessed March 28, 2017. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?q=%22fakenews%22.

- Google. 2017b. Google Trends – “Fake News” (in the US). Accessed March 28, 2017. https://trends.google.dk/trends/explore?geo=US&q=fakenews.

- Heath, Alex. 2016. Facebook Didn’t Block Fake News Because It was Reportedly Scared of Suppressing Right-Wing Sites. Business Insider. November 14. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-didnt-block-fake-news-because-of-conservative-right-wing-sites-report-2016-11?r=US&IR=T&IR=T.

- Hendricks, Vincent, and Pelle G. Hansen. 2014. Inforstorms: How to Take Information Punches and Save Democracy. New York: Springer.

- Higgins, Andrew, Mike McIntire, and Gabriel J. X. Dance. 2016. “Inside a Fake News Sausage Factory: ‘This Is All About Income’.” The New York Times. November 25. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/25/world/europe/fake-news-donald-trump-hillary-clinton-georgia.html?smid=tw-share&_r=1.

- Hinchlife, Emma. 2016. Download These Chrome Extensions that Flag Fake News on Your Parents’ Computers. Mashable. November 16. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://mashable.com/2016/11/16/fake-news-alert-chrome-extension/#v.PMgLS2pSqn.

- Howarth, David R., Aletta J. Norval, and Yannis Stavrakakis. 2000. Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies and Social Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jamieson, Amber. 2017. “‘You are Fake News’: Trump attacks CNN and BuzzFeed at Press Conference.” The Guardian, January 11. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/11/trump-attacks-cnn-buzzfeed-at-press-conference.

- Jessop, Bob. 2017. “The Organic Crisis of the British State: Putting Brexit in its Place.” Globalizations 14 (1): 133–141. doi:10.1080/14747731.2016.1228783.

- Karlova, Natascha A., and Karen E. Fisher. 2013. “A Social Diffusion Model of Misinformation and Disinformation for Understanding Human Information Behaviour.” Information Research 18 (1). http://www.informationr.net/ir/18-1/paper573.html.

- Keshavarz, Hamid. 2014. “How Credible is Information on the Web: Reflections on Misinformation and Disinformation.” Infopreneurship Journal 1 (2): 1–17. http://eprints.rclis.org/23451/1/How%20Credible%20is%20Information%20on%20the%20Web.pdf.

- Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2011. Blur: How to Know What’s True in the Age of Information Overload. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Krugman, Paul. 2014. “On the Liberal Bias of Facts.” The New York Times, April 18. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/18/on-the-liberal-bias-of-facts/?_r=0.

- Kumar, Srijan, Robert West, and Jure Leskovec. 2016. Disinformation on the Web: Impact, Characteristics, and Detection of Wikipedia Hoaxes. WWW “16 - Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2872427.2883085.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1990. New Reflections on the Revolution of Our Times. London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1996. Emancipation(s). London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2014. The Rhetorical Foundations of Society. London: Verso.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. (1985) 2014. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. 2nd ed. paperback. London: Verso.

- Lemann, Nicholas. 2016. “Solving the Problem of Fake News.” The New Yorker, November 30. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/solving-the-problem-of-fake-news.

- Linebarger, Paul MA. 1955. Psychological Warfare. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Combat Forces Press.

- Marchart, Oliver. 2007. Post-Foundational Political Thought: Political Difference in Nancy, Lefort, Badiou and Laclau. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Masur, Matt. 2016. “Bernie Sanders Could Replace President Trump With Little-Known Loophole.” The Huffington Post, November 15, Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/bernie-sanders-could-replace-president-trump-with-little_us_5829f25fe4b02b1f5257a6b7.

- Norman, Matthew. 2016. “Whoever Wins the US Presidential Election, We’ve Entered a Post-Truth World – There’s No Going Back Now.” The Independent, November 8. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/us-election-2016-donald-trump-hillary-clinton-who-wins-post-truth-world-no-going-back-a7404826.html.

- Nunez, Michael. 2016. “Facebook’s Fight Against Fake News was Undercut by Fear of Conservative Backlash.” Gizmodo, November 14. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://gizmodo.com/facebooks-fight-against-fake-news-was-undercut-by-fear-1788808204.

- Oremus, Will. 2016a. “Did Facebook Really Tolerate Fake News to Appease Conservatives?” Slate, November 14. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2016/11/14/did_facebook_really_tolerate_fake_news_to_appease_conservatives.html.

- Oremus, Will. 2016b. “Stop Calling Everything ‘Fake News’.” Slate, December 6. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2016/12/stop_calling_everything_fake_news.html?wpsrc=sh_all_dt_tw_top.

- Örnebring, Henrik, and Anna Maria Jönsson. 2004. “Tabloid Journalism and the Public Sphere: a Historical Perspective on Tabloid Journalism.” Journalism Studies 5 (3): 283–295. doi:10.1080/1461670042000246052.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2016. “ News Tips - Week of Nov. 21, 2016.” Office of Public and Government Affairs. University of Illinois at Chicago. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://uofi.uic.edu/emailer/newsletter/111748.html.

- Rucker, Phillip, John Wagner, and Greg Miller. 2017. “Trump Wages War Against the Media as Demonstrators Protest his Presidency.” The Washington Post, January 21. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-wages-war-against-the-media-as-demonstrators-protest-his-presidency/2017/01/21/705be9a2-e00c-11e6-ad42-f3375f271c9c_story.html.

- Schou, Jannick. 2016. “Ernesto Laclau and Critical Media Studies: Marxism, Capitalism, and Critique.” TripleC 14 (1): 292–311. http://www.triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/740. doi: 10.31269/triplec.v14i1.740

- Shellenbarger, Sue. 2016. “Most Students Don’t Know When News Is Fake, Stanford Study Finds.” The Wall Street Journal, November 21. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/most-students-dont-know-when-news-is-fake-stanford-study-finds-1479752576.

- Silverman, Craig. 2016a. “This Analysis Shows How Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News on Facebook.” Buzzfeed News, November 16. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook.

- Silverman, Craig. 2016b. “Most Americans Who See Fake News Believe It, New Survey Says.” Buzzfeed News, December 7. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/fake-news-survey?utm_term=.kdNMQZ6aD6#.obj74yp1zp.

- Silverman, Craig, and Lawrence Alexander. 2016. “How Teens in the Balkans are Duping Trump Supporters with Fake News.” Buzzfeed News, November 4. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo?utm_term=.ebrpdWyymW#.ijbg9Q44YQ.

- Silverman, Craig, Lauren Strapagiel, Hamza Shaban, Ellie Hall, and Jeremy Singer-Vine. 2016. “Hyperpartisan Facebook Pages Are Publishing False And Misleading Information At An Alarming Rate.” Buzzfeed News, October 20. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/partisan-fb-pages-analysis?utm_term=.an82QeMMJe#.wb8jdLOOqL.

- Sim, Stuart. 2000. Post-Marxism: An Intellectual History. London: Routledge.

- Skinner, Sally, and Bill Martin. 2000. “Racist Disinformation on the World Wide Web: Initial Implications for the LIS Community.” The Australian Library Journal 49 (3): 259–269. doi:10.1080/00049670.2000.10755925.

- Smith, Anna Marie. 1998. Laclau and Mouffe: The Radical Democratic Imaginary. London: Routledge.

- Snyder, Michael. 2014. “Is The Mainstream Media Dying? Ratings at CNN, MSNBC and Fox News Have All been Plummeting in Recent Years.” InfoWars, May 20. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.infowars.com/is-the-mainstream-media-dying/.

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2016. “Three ways Facebook Could Reduce Fake News Without Resorting to Censorship.” The Conversation, December 2. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://theconversation.com/three-ways-facebook-could-reduce-fake-news-without-resorting-to-censorship-69033.

- Times Staff. 2017. “Read President Trump’s Interview with TIME on Truth and Falsehoods.” Time Magazine, March 23. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://time.com/4710456/donald-trump-time-interview-truth-falsehood/.

- Torfing, Jacob. 1999. New Theories of Discourse: Laclau, Mouffe and Žižek. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Trump, Donald. 2017a. “FAKE NEWS - A TOTAL POLITICAL WITCH HUNT!” Twitter, January 11. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/818990655418617856.

- Trump, Donald. 2017b. “.@CNN is in a Total Meltdown with their FAKE NEWS Because Their Ratings are Tanking Since Election and Their Credibility Will Soon be Gone!”. Twitter, January 12. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/819550083742109696.

- Trump, Donald. 2017c. “Somebody with Aptitude and Conviction Should Buy the FAKE NEWS and Failing @nytimes and Either Run it Correctly or Let it Fold with Dignity!” Twitter, January 29. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/825690087857995776.

- Trump, Donald. 2017d. “‘BuzzFeed Runs Unverifiable Trump-Russia Claims’ #FakeNews.” Twitter, January 11. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/819000924207251456.

- Trump, Donald. 2017e. “Don’t Believe the Main Stream (Fake News) Media. The White House Is Running VERY WELL. I Inherited a MESS and am in the Process of Fixing it.” Twitter, February 18. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/832945737625387008.

- Trump, Donald. 2017f. “The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People!” Twitter, February 17. Accessed May 16, 2018. https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/832708293516632065

- Tudjman, Miroslav, and Nives Mikelic. 2003. “Information Science: Science about Information, Misinformation and Disinformation.” Proceedings of Informing Science and Information Technology Education Joint Conference, Pori, Finland.

- Woollacott, Emma. 2016. In Today’s Post-Factual Politics, Google’s Fact-Check Tag May Not Be Much Help. Forbes. October 14. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/emmawoollacott/2016/10/14/in-todays-post-factual-politics-googles-fact-check-tag-may-not-be-much-help/#5844ff822395.

- Zimdars, Melissa. 2016a. False, Misleading, Clickbait-y, and/or Satirical “News” Sources. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://docs.google.com/document/d/10eA5-mCZLSS4MQY5QGb5ewC3VAL6pLkT53V_81ZyitM/preview.

- Zimdars, Melissa. 2016b. “My “Fake News List” Went Viral. But Made-Up Stories are Only Part of the Problem.” The Washington Post, November 18. Accessed June 27, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/11/18/my-fake-news-list-went-viral-but-made-up-stories-are-only-part-of-the-problem/.