Abstract

Deliberation is classically understood as a communication process where equal participants justify their positions in a respectful, reciprocal, argumentative manner. However, critical scholars have argued for a concept of deliberation that incorporates other forms of communication beyond argumentation, for example, expressions of emotions. While previous research focused on differences between positive and negative emotions, we introduce a distinction between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions. Whilst constructive emotions focus on the discussed issue, non-constructive emotions refer to other participants. We draw on a quantitative relational content analysis of user comments written in an online-participation platform. The results show a positive effect of constructive expressions of emotions on the deliberative quality of interactive user comments and a negative effect of non-constructive expressions of emotions. Overall, we conclude that emotions can promote the deliberative quality of interactive user comments if they are not focused on other participants but on the discussed issue.

Introduction

Deliberative democracy scholars have shown great interest in citizens discussing politics online. As a result, empirical studies have found variance in the deliberative quality of different online publics (e.g. Esau, Fleuß, and Nienhaus Citation2021; Janssen and Kies Citation2005). At the same time, the question of what exactly represents deliberative quality remains a controversial subject. From a classic point of view, deliberation is understood as a demanding communication process where equal participants justify their positions in a respectful, reciprocal manner, always willing to accept the force of the better argument. From this perspective, deliberation is seen as rational discourse via argumentation (Habermas Citation1975, Citation1984, Citation1996). This focus on argumentation has been criticised for bypassing different citizens’ skills and speech styles, excluding some more than others (Sanders Citation1997; Young Citation2000). From the criticism a more tolerant perspective has developed, arguing that deliberation research should shift to a form of discourse that incorporates values, personal experiences and emotions through, for example, emotional expressions, storytelling, or humour (Basu Citation1999; Bickford Citation2011; Black Citation2008a; Young Citation2000). Although the critique has been convincing, the effort to give emotions a place in deliberation is more complex and constitutes one central challenge for democracy theory and empirical research (Bächtiger et al. Citation2010; Dryzek Citation2000). What role emotions play in public deliberation remains one of the most controversial issues in political theory (Hall Citation2005; Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012; Nussbaum Citation2015).

Emotions are part of human reality and cannot be excluded from deliberation. However, they also cannot be included without further theorising on the relationship between emotions and crucial norms of deliberative quality. Regarding the norm of rationality, emotions communicated to others can be seen as implicit moral judgements and can take the role of reasons comparable to observations (Habermas Citation2005). Emotions can stimulate empathy and perspective taking and therefore contribute to impartiality (Krause Citation2008) and mutual understanding (Morrell Citation2010). The latter requires reciprocity: the give and take of reasons that others respond and reflect on (Graham Citation2008, Citation2010; Gutmann and Thompson Citation1996). While reciprocity counts as a core norm of deliberation (Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen Citation2013), we lack a theoretical understanding of deliberative reciprocity that incorporates emotions.

Although emotions play an important role in online political discussions (Barnes Citation2015), we know little about the relation between emotions and reciprocity. Empirical studies have found emotions to be correlated with argumentation and reciprocity (Esau Citation2018; Esau, Frieß, and Eilders Citation2019; Graham Citation2010). Beyond correlations, there is scarce empirical knowledge on what types of emotions promote reciprocity online (Esau Citation2022; Esau and Friess Citation2022; Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2019; Ziegele et al. Citation2020). The research gap can be explained by previous theories focusing on positive and negative emotions (Hoggett and Thompson Citation2002; Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000). Given the limited theoretical and empirical research on emotions and reciprocity, we seek to explore the problem by answering the following overarching research question: How do different types of expressions of emotions affect the deliberative quality of interactive user comments in online political discussions?

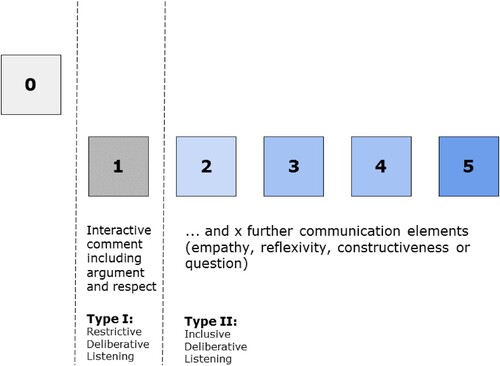

Referring to the lack of a theoretical underpinning on the relationship between emotion and reciprocal deliberation, we firstly argue for an understanding of reciprocity that incorporates emotions. For this, we draw on previous theoretical accounts that conceptualised reciprocity either as closely tied to rationality (Gutmann and Thompson Citation1996) or as a combination of interactivity and respect (Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen Citation2013; Gutmann and Thompson Citation2004) and combine them with concepts of listening (Dobson Citation2012; Goodin Citation2000; Krause Citation2008). Against this backdrop, we distinguish between three types of reciprocity: simple replying, restrictive deliberative listening (reciprocity, respect, rationality) and inclusive deliberative listening (reciprocity, respect, rationality, communicative empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, questions).

Secondly, we introduce a distinction between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotion. We draw on political theory and argumentation theory to build new links between different types of emotions and reciprocity (Bickford Citation2011; Dryzek Citation2000; Krause Citation2008; Walton Citation1992). On this basis, we argue that certain expressions of emotion, can promote reciprocal communication, however this is not aligned with previous research on the sheer existence or non-existence of emotions or on differences between positive and negative emotions. Instead, we proceed distinguishing emotions depending on what they are related to in the communication process: Whilst constructive emotions focus on the discussed issue, non-constructive emotions refer to other participants, e.g. to their personality or credibility.

Thirdly, the paper aims at making an empirical contribution by investigating the relationship between emotions and different forms of reciprocity in online discussions. We provide operationalisations for the concepts of (non-)constructive emotions and inclusive listening and apply them on a sample of user comments (N = 903) written on an online participation platform. We argue that constructive expressions of emotion are more likely to receive response comments of high deliberative quality than non-constructive expressions of emotion. Further, we argue that the distinction between constructive and non-constructive emotions provides a better explanation of deliberative quality than the distinction between positive or negative emotions.

Before discussing the findings of our empirical study and their implications, we start by developing our theoretical understanding of inclusive listening.

From a Restrictive to an Inclusive Concept of Deliberative Reciprocity

Deliberative democracy refers to a discursive form of democracy in which a demanding form of a communication process, deliberation, is put into the centre of the decision-making process (Habermas Citation1994). From this normative view, public deliberation should ideally produce decisions through the transformation of preferences based on mutual understanding rather than mere aggregation of preferences. Beyond these core assumptions, the definitions of deliberation itself and therefore the conceptualisations of what characterises deliberative quality of a communication process vary greatly between scholars and traditions (e.g. Black Citation2008a; Polletta and Lee Citation2006; Steenbergen et al. Citation2003). A central point of contention is the question, which place emotions can be given in deliberation.

The literature is broadly divided into two camps: those that hold a more classic or restrictive (Type I-) view on deliberation and those with a more expansive or inclusive (Type II-) view (Bächtiger et al. Citation2010). From a classic point of view, the deliberative quality of communication can be characterised by respectful, reciprocal, and argumentative communication (Cohen Citation1989; Habermas Citation1975, Citation1996). Alongside this, the classic concept of deliberation has been suspicious of emotions and their manipulative and coercive power. Emotions, subsequently, took a subordinate or ambivalent role in classic deliberative democracy theory. Criticising this point of view for being too restrictive, other deliberative democrats have argued for a more expansive concept of deliberation. For example, Sanders (Citation1997) has pointed out that “material prerequisites for deliberation are unequally distributed” and some “are more likely to be persuasive than others, that is, to be learned and practiced in making arguments that would be recognised by others as reasonable ones” (2). Young (Citation2000) argued that the form of argumentation preferred in the classic concept is not characterised by reasonableness, but by articulateness and dispassionateness. This is not necessarily connected to mutual understanding but reflects communication styles associated with higher formal education, as well as with Western and male-dominated culture. Consequently, this style of communication carries hegemonic elements and does not adequately reflect alternative communication cultures within subpopulations beyond elitist groups.

The problem in a nutshell is that what counts as “rational” is primarily negotiated by white Western men (Dahlberg Citation2007; Fraser Citation1990) disadvantaging those without access to or knowledge on elitist speech conventions. While one popular demand is to increase basic argumentation skills of all citizens (e.g. Nishiyama Citation2018), an alternative solution is to widen the repertoire of speech styles taken as appropriate in political discussions. Hereby, people from different social backgrounds are empowered to voice their standpoints in their own words, meaning an authentic speech style, which they think is best suited to represent their social reality. These alternative speech styles may include—among others—storytelling, humour, and expressions of emotion (Basu Citation1999; Bickford Citation2011; Sanders Citation1997; Young Citation2000).

Critical voices have struggled for the rehabilitation and inclusion of emotions in deliberative democracy theory, but synthesis steps to translate the criticism into new theoretical concepts have yet to follow. In this context, Krause (Citation2008) has noted that “theorists who do incorporate affect into deliberation tend to lack convincing criteria for precisely how affect should be incorporated and when its contributions are sound” (152). In the current state, it is unclear which and how emotions should be expressed and replied to. Bickford (Citation2011) gets to the heart of this matter: “one central puzzle is that because we are habituated in a context of difference, conflict, and inequality, it is particularly difficult to distinguish which emotions and what kind of emotion talk we should listen to” (1026). Krause (Citation2008) has also argued that we lack an understanding of reciprocity that incorporates emotions and affective elements of perspective-taking. Building on this, we argue that to contribute to solving the puzzle of what emotions to listen to, we first need a better understanding of how emotions and listening function together in public deliberation.

A Shared Understanding of Reciprocity: Inclusive Listening

In the previous part, we discussed arguments on why both, the restrictive, as well as the tolerant view on the deliberative quality of communication, need further theoretical adjustments. We acknowledge that there are good reasons to understand public deliberation as a distinguished communication process that should be immunised against coercion and manipulation. However, the exclusion or disregard of emotions in deliberation processes does not remove these problems and furthermore it bears the risk of excluding perspectives. Addressing Youngs’, Sanders’, and Krause’s arguments, we suggest beginning with an understanding of reciprocity that integrates the expression of emotions and therefore can be accepted by both camps. While the norm of rationality has been a central point of disagreement, the norm of reciprocity has been held up high by most deliberative democrats and is considered a key element of deliberation (Kies Citation2010; Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen Citation2013). Not only does reciprocity provide a basis for understanding and common ground inside deliberation, but also in deliberation research, creating a bridge between the different views on what characterises deliberation. If certain forms of emotional communication can be shown to stimulate or hinder reciprocity in online political discussions, then strong empirical arguments would be provided to both, restrictive and tolerant, views on deliberation.

But what does a shared understanding of reciprocity that both camps can accept look like? Starting with the classic understanding, reciprocity has been connected to interactivity, respect, and rationality (Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen Citation2013). In its general form, reciprocity has been conceptualised as a “mutual exchange” (Gutmann and Thompson Citation1996, 55). For deliberation this means that speech acts are interrelated and take the form of discourse or dialogue. Specifically, Bohman (Citation1996) defined deliberative dialogue as “the give and take of arguments among speakers” (42). Gutmann and Thompson (Citation2004) added to this understanding and pointed out that the ideas of mutual respect and mutual reason giving are both interconnected parts of reciprocity. As a baseline of respect is needed for the mutual process of reason giving, respect can be considered a precondition for deliberative reciprocity. In summary, reciprocity has been classically defined as a mutual exchange that requires respect and provides rationality through reason-giving.

Compared to the classic concept of deliberation, the inclusive one never proposed a common understanding of reciprocity. Instead of developing an understanding of reciprocity, they stressed the value of listening. Sanders (Citation1997), concerned about the unequal distribution of speaking and listening, concludes that those who are usually left out of public discussions should learn to speak and those who usually dominate should learn to hear. Bickford (Citation2011) including emotions into her understanding of deliberation argued that certain cases might, when the substance of a sentence requires an emotion, but no emotion is expressed, lead to confusion on the side of the listener. She does not explicitly state this, but expressions of emotions seem to fulfil the function of promoting reciprocity by appealing to listeners’ emotions. According to Young (Citation2000), not only the give and take of arguments but also different forms of emotional communication can express mutual respect and encourage reciprocity. Referring to Levinas (Citation1991), she states that “the speaker responds to the other person’s sensible presence […] but without promise of reciprocation” (58, emphasis added). The norm of reciprocity, while still important, appears to be elusive and harder to predict when compared to the classic understanding. Earlier, Young (Citation1997) argued that theorists should give more attention to the asymmetry of speakers by focusing on “questions as uniquely important communicative acts. Questions can express a distinctive form of respect for the other, that of showing an interest in their expression and acknowledging that the questioner does not know what the issue looks like for them” (55). In summary, the core norm in inclusive concepts of deliberation seems to be respectful listening to others, their perspectives, and emotions. However, how exactly the listener should act, apart from listening, remains undefined.

In classic concepts of deliberation more attention has been paid to speaking and less to listening (Dobson Citation2010). One notable exception is Barber (Citation1984) who gives “the mutualistic art of listening” a central role in his concept of a “strong democracy”. However, in recent years, both classic and tolerant scholars started highlighting the importance of listening. Gastil and Black (Citation2008) described deliberation as both an analytic and social process. Consequently, the give and take of arguments, can be called analytic reciprocity, while demonstrating mutual respect and listening refers to social reciprocity. Hendriks, Ercan, and Duus (Citation2019) have presented the most extensive discussion of listening in public deliberation and pointed out that “good” listening can be associated with openness, respect, and empathy. Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen (Citation2013) pointed out that reciprocity describes participants’ effort to listen to and respond to the demands and arguments of other participants. Against this background, Morrell (Citation2018) argues that listening and reciprocity are closely connected: “Without listening to others and understanding their concerns, it would be impossible for citizens to demonstrate reciprocity” (238). However, Morrell concluded that there is no comprehensive theory of how listening should function in deliberation processes. “Beyond developing a clear theory, scholars must continue to explore the factors that might promote good deliberative listening” (12). We agree and argue that this is especially true for online discussions where listening can only be demonstrated by responding to other users’ comments.

It might seem counterintuitive to search for listening, a concept assigned to face-to-face interactions, in online political discussions. However, after reviewing classic and inclusive concepts of reciprocity and listening, we argue that compared to interactivity and reciprocity the concept of listening is a more powerful bridge between the two camps. So far, the results of studies on engagement, interactivity and reciprocity online have barely contributed to deliberative democracy theory. One reason for this is that previous research has focused on technical structure of online interaction (Aragón, Gómez, and Kaltenbrunner Citation2017; Himelboim Citation2008; Wilhelm Citation1998). However, the simple fact that an online message “is reciprocal does not necessarily imply that this message is deliberative” (Kies Citation2010, 45). Therefore, we distinguish simple replying, the formal fact that user comments are connected through the technological infrastructure (e.g. tree structure, reply button, @-sign, quote function), from more substantial replies that indicate the speaker has read and listened to the perspective of the other.

Some scholars have differentiated types and dimensions of substantial replying or reciprocity online (Graham Citation2008; Graham and Witschge Citation2003; Kies Citation2010; Stromer-Galley Citation2007). According to Kies (Citation2010) reciprocity online implies that participants should listen and react to the comments formulated by other participants. Further, “negative deliberative value should only be given when the lack of reciprocity discloses an absence of disposition to listen to each other” (45). Kies prefers a “nuanced interpretation of the presence of reciprocity that would take into account the scores realised by other deliberative criteria—in particular reflexivity, justification, and empathy” (46). Graham and Witschge (Citation2003) defined reciprocity online as “the taking in (listening, reading) of another’s claim or reason and giving a response” (176). The authors pointed out that this concept of reciprocity alone is not enough, but that reflexivity and empathy are also needed to stimulate mutual understanding.

To round out the concept of deliberative listening we include constructiveness and questions. Questions are included because asking questions can be a marker of reciprocity and listening (Young Citation1997). Stromer-Galley (Citation2007) agrees’ that questions are reciprocal, if they indicate the genuine will for reflection on a statement that has been made in the discussion. As for constructiveness, it appears when participants reflect on problems that arise during the discussion and propose ideas for solutions to the problem at hand. Constructive contributions can replace moderators in unmoderated online discussions. They can solve conflicts and blockades during the discussion and can give summaries in the end of a thread so that new users don't lose track. Because they require reflection about previous utterances in the discussion, they contribute to the process of mutual understanding. Although constructive contributions require reflection, they differ from the reflexivity concept used in this study, as reflexivity generally refers to the process in which the speaker refers to their own thoughts or statements in light of what others have said, for example adjusting a statement or changing one’s opinion because of information that somebody provided (Graham and Witschge Citation2003).

Against this background, we propose an inclusive understanding of listening in online political discussions. Thereby, we differentiate between three types of reciprocity online: simple replying, restrictive deliberative listening (Type I-listening) and inclusive deliberative listening (Type II-listening). We define simple replying as a formal interaction among online users, which is interactive but does not necessarily fulfil quality criteria. Compared to simple replies, restrictive deliberative listening is a more demanding concept defined as a substantial response to another comment, which is on topic, includes an argument and is respectful. The concept therefore lives up to the norms of reciprocity, rationality, and respect (Bohman Citation1996; Gutmann and Thompson Citation1996, Citation2004; Pedrini, Bächtiger, and Steenbergen Citation2013). Addressing the more tolerant perspectives on reciprocity and listening (Bickford Citation2011; Young Citation1997, Citation2000), we include communicative empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, and questions as dimensions of inclusive deliberative listening.

We argue that the deliberative quality of user comments can only be grasped through a multi-dimensional concept such as inclusive deliberative listening. Given that the concept integrates both classic and expansive understandings of the norms of reciprocity and listening we think that it provides a common ground between the two camps in deliberative theory.

Constructive and Non-Constructive Emotions in Deliberation

To assess the role of emotions for public deliberation, we draw on findings from neuroscience, psychology, political theory, and argumentation theory. In order to understand what types of emotions are constructive, and which are non-constructive for deliberation, we first show why emotions can be functional in the process of deliberation. According to research in neuroscience, emotions, along with the physiological processes underlying them, assist in dealing with uncertain situations, planning actions, and making decisions (Damasio Citation1994; LeDoux Citation1996). According to psychology, the basic function of emotions is to address or overcome problems in general and social problems in particular (Fischer and Manstead Citation2016; Lazarus Citation1991). On an interpersonal level, emotions enable social relationships and prevent social isolation (Fischer and Manstead Citation2016). Further, emotions provide a better understanding of others’ beliefs and intentions while at the same time serving as incentives for social behaviour (Keltner and Haidt Citation1999). Furthermore, it has been argued in political psychology that emotions are functional for political thinking, behaviour, and communication (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Citation2000). For example, fear can stem from the feeling of not being able to assess a situation, which may lead to discomfort, the will to change the situation and due to this to the endeavour to obtain new information and to think (Marcus Citation2003). Similarly, anger can stem from conflicting interests or values and angry participants in deliberative processes can provide more arguments and listen more to arguments of others.

Theoretical thoughts on the role of emotions in public deliberation have so far either focused on the sheer existence or non-existence of emotions or on differences between positive and negative emotions (Bickford Citation2011; Dryzek Citation2000; Hoggett and Thompson Citation2002; O’Neill Citation2002; Saam Citation2018). For example, Bickford (Citation2011) and Black (Citation2008a) argued that the existence of emotions in deliberation can promote mutual understanding. According to Black (Citation2008a), the improved understanding gained through expressions of emotion can lead to the emergence of so-called dialogic moments. A state in which discussion partners reveal their motives, discuss them respectfully and form a common identity. Dialogic moments enable others to adopt a perspective and, at the same time, to rethink one's own attitudes. Against this background, expressions of emotions can be seen as crucial communication elements in deliberation processes and attempts to exclude emotions may suppress “particular ways of making a point” (Dryzek Citation2000, 53).

However, in theory emotions do not exclusively offer potential for deliberation but can also potentially damage the process and steer it in undesirable directions. Dryzek (Citation2000, Citation2010) emphasised the coercive and manipulative power of emotions and implied that expressing them may not always lead to mutual reflection, only when emotions can be linked to more general principles (e.g. social justice). Hoggett and Thompson (Citation2002) illustrated based on recorded notes of a citizen forum that group emotions can be instruments for political opportunists to attack and shut down voices in public. Saam (Citation2018) argued that the “emphasis on emotional expression actually serves to perpetuate social inequality rather than to eliminate it” (755). She argues that emotional speech can have the effect of humiliating others and that feelings of shame and humiliation can be problematic if they silence the voices of participants of lower social background. Concluding from these points of view, not all expressions of emotions may have a positive effect on the course of public deliberation.

Against this background, the question which expressions of emotions may have a positive or negative effect on the course of deliberation remains open. We argue that we need a normative account of affective deliberation. Therefore, we introduce a new distinction between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions. Whilst constructive emotions focus on the discussed issue; non-constructive emotions refer to other participants. In developing our theoretical argument, we build on Krause (Citation2008) and her understanding of affective reciprocity and Walton (Citation1992) and his concept of emotional arguments.

Krause (Citation2008) argued that expressions of emotions “can contribute in valuable ways to public deliberation even when they do not take an explicit argumentative form” (118). Regarding the need to incorporate emotions into deliberation, she says that previous theoretical attempts to do so were not successful. From her point of view, “invoking rational justification to establish the criteria for legitimate affect” is not a satisfying approach because “there is no such thing as rational justification in the absence of affective modes of consciousness” (155). Instead, Krause argues for other normative criteria to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate emotions in deliberation. She does not explicitly provide criteria that help to decide when emotions are legitimate or illegitimate, but she thinks that the “object of the emotion” (154) is crucial. In favour of relational theoretical approaches, we argue that to evaluate emotions within deliberation we should focus on the object of the expressed emotion. When we think of deliberation processes, there are usually two types of objects about which participants feel and express emotions: the discussed issue or other participants.

In online discussions, it is common for speakers to express emotions to other participants with whose opinion they agree or disagree. This can lead to a situation where speakers become the target of other participants’ emotions. Krause (Citation2008) problematises emotions that reflect “bigotry”, “personal animosity” or “mistakes of fact” (165–166). For example, she argues that emotional reactions of racists have no place in public deliberation: “we should discount, on reflection, the pain the racist feels in the face of anti-discrimination laws” (166). Instead of discounting the “pain” as Krause requests, we want to put the focus on the object of the emotion. If it is indeed pain about the law that is being discussed, that is expressed by a racist, or anyone in the deliberation process, then it has a legitimate place in deliberation. It can trigger empathy, reflection, and reciprocity in others. If the “pain” manifests itself as an expression of anger or hate towards other individuals or groups and is aimed at humiliating speakers, shutting down voices and building coalitions against others then it becomes a non-constructive emotion. All of which have no place in deliberation as all of which are not helpful for reciprocity and listening.

In argumentation theory, Walton (Citation1992) analysed cases of everyday conversation and distinguished between different types of emotional arguments that are either used as fallacies or constructively to support critical discussion and conflict resolution. According to his theory, arguments based on emotions offer a way of expressing attitudes towards the discussed issue—as “commitments that reflect the arguer's deeper, underlying convictions or position” (27)—which can otherwise be difficult to express. Walton shows that both negative and positive emotions that refer to other dialogue partners can be used to manipulate or attack others and therefore can lead away from critical dialogue. This becomes evident with the example of ad hominem arguments and the discussion dynamic that can follow from them. An ad hominem argument is “an argument that uses a personal attack against an opposing arguer to support the conclusion that the opposing argument is wrong” (3). Walton argues that such personal attacks are easy to construct but hard to respond to, as they put pressure on the speaker to respond strongly and therefore are likely to lead to verbal combats:

Indeed, one of the main problems of using an ad hominem argument is that it has a way of making a discussion into a quarrel. Once the ad hominem is used, it is often used by the attacked person again, in tu quoque fashion, and as personalization of the argument deepens, it becomes difficult to turn back to a less personalized discussion of the issue. (Walton Citation1992, 192)

Based on the theoretical arguments presented above we believe that the distinction between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions, depending on the object that the emotion is related to, provides a useful lens to study deliberation. Emotions that refer to the discussed topic, for example a social conflict, a law or political decision, are defined as constructive emotions and expressions of emotions that refer to other participants, for example their political standpoint, person, or credibility, as non-constructive.Footnote1

Research Questions

Addressing the calls for a more inclusive concept of deliberative quality, previous empirical studies could show that expressions of emotions go hand in hand with classic characteristics of deliberative quality: respect, rationality, and reciprocity (Esau Citation2018; Black Citation2008b; Graham Citation2008, Citation2010; Jaramillo and Steiner Citation2014; Polletta and Lee Citation2006; Steiner et al. Citation2017). Thereby, the results suggest that both, positive and negative emotions can have positive effects on the course of deliberation (Graham Citation2010; Jaramillo and Steiner Citation2014; Steiner et al. Citation2017). However, other empirical studies have demonstrated no effects or negative effects of expressions of emotions on other characteristics of deliberative quality (Esau Citation2018; Mansbridge et al. Citation2006; Roald and Sangolt Citation2011). The state of the art provides only little knowledge on the relationship between the expression of emotions and deliberative quality beyond correlations. For example, we do not know which emotions and which types of expressions of emotions stimulate or impede deliberative quality. As described in the theoretical part above we distinguish between constructive emotions that refer to the discussed issue and non-constructive emotions that refer to other participants. Given the lack of empirical research on these different types of emotion expression, our study addresses the following two research questions:

How do constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions affect inclusive deliberative listening?

Does the distinction between constructive and non-constructive emotion expression provide a better explanation of inclusive deliberative listening compared to the distinction between positive and negative emotions?

Methodology

Sample

To answer the research questions a quantitative relational content analysis of online user comments written on an official citizen participation platformFootnote2 at the regional level of politics was conducted. The topic of the public online discussions was the future of coal mining in the Rhenish mining district in Germany. The subject of the discussion involved the future of coal mining, possible resettlements of residents and job losses. Between September and December 2015 overall 1215 registered users participated, writing a total of 1216 comments, and producing 17,300 comment votes. Citizens, businesses, and representatives of municipalities had the opportunity to comment on four key decisions provided on the platform. The platform was manually pre and post moderated by a service provider but the numbers of prefiltered comments as well as moderator comments were very low (less than 2 per cent). The data gathering and majority of the coding process took place between August and September 2017. A full sample of 1216 user comments was coded. For the analysis in this study, the largest thread, a sample of 903 subsequent user comments has been selected. The discussion thread was chosen because of the lively participation providing a good basis for analysis. It was further suitable to investigate effects of emotions due to its relevance to individuals’ living conditions.

Coding

An innovative method of quantitative relational content analysis was developed, tested, and applied by the first author to analyse the content and structure of online discussions (Esau Citation2022). Both, the content of the user comments and the relations between the comments were coded manually. This relational approach allows new analysis strategies for the explanation of the deliberative quality of interactive user comments. For the coding process the BRAT annotation tool has been used (Stenetorp et al. Citation2012; Strippel et al. Citation2022). The tool allows for text span annotations for the coding of content in user comments, relation annotations for coding the relations between comments and relations between content in comments.

The coding scheme for the analysis was developed by the first author based on previous deliberation research (e.g. Esau Citation2022; Black Citation2008a; Black et al. Citation2011; Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017; Graham Citation2008; Steenbergen et al. Citation2003; Stromer-Galley Citation2007). From a first coding scheme (Esau Citation2022) 11 manually coded variables were used for this study. Additionally, two new variable characteristics for constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions were added and codedFootnote3 (for an overview of all variable descriptions cf. ). Further, two variables have been coded automatically (comment length and comment position in the thread).

TABLE 1 Coding scheme: dimensions, measures and definitions

Different Types of Emotions. Expressions of emotions, emojis and appeals to the emotions of others were coded in four different variables. The first classification of emotions refers to the valence of the expressed emotion, distinguishing positive and negative emotions. Emotions like joy, enthusiasm or hope were coded as positive emotions and emotions like anger, fear or sadness were coded as negative emotions. Accordingly, for a user comment with at least one expression of positive emotion the variable positive emotion was coded as 1. If the comment did not include positive emotions the variable was coded as 0. The same coding procedure was applied to negative emotions. The second classification of emotions distinguishes between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions depending on the reference point of the emotion. In line with our theoretical concept, we conceptualise expressions of emotions as constructive if the emotion refers to the topic of the discussion, for example the emotion is expressed in relation to a social conflict, a law or political decision. Expressions of emotions that refer to other participants, for example their political standpoint, person, or credibility, are defined as non-constructive. Accordingly, for a user comment with at least one expression of emotion related to the topic the variable constructive emotion was coded as 1, if the comment did not include an expression of an emotion related to the topic it was coded as 0. In contrast, comments containing an emotion related to other participants were coded as 1 in the variable non-constructive emotions and 0, if the comment did not include these types of emotions. Note that in case of more than one emotional expression per comment, comments may contain both, constructive and non-constructive elements, at the same time. However, this was true for only 3 per cent of comments containing emotional expressions.

Inclusive Listening Index (IncLI). As indicator for the deliberative quality of interactive user comments a graded index was constructed. The index follows a theoretical approach, meeting the requirements of restrictive deliberative listening as well as including further communication elements suggested by inclusive concepts (comparable to the Type I- and Type II-views on deliberation, see Bächtiger et al. Citation2010). The index was only calculated for comments that were on topic and showed signs of interactivity (e.g. through the tree structure, @-signs, quotations of previous comments). We distinguished between simple replies and substantial interactive comments meeting basic requirements in terms of the restrictive concept of deliberative reciprocity (argumentation and respect). User comments that showed signs of interactivity but did not meet the other basic requirements (no argumentation and/or not respectful) were coded as 0. Accordingly, comments showing at least one argument and being respectful were coded as 1 (). Further, the index included communication elements suggested by an inclusive concept of deliberative listening (communicative empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, and questions). We added plus 1 to the index for every one of these communication elements (). The result is a metric quality index for interactive comments (IncLI, M = 0.8, SD = 0.569) ranging from 0 (simple reply of insufficient deliberative quality) to 1 (restrictive deliberative listening) to 2, 3, 4 and 5 (inclusive deliberative listening).

Control variables. The comment length (in characters) was coded automatically and categorised as very long, long, medium, short, very short based on previous research (e.g. Ziegele, Breiner, and Quiring Citation2014). The categories are 1 = very short (1–70 characters), 2 = short (71–200 characters), 3 = medium (201–350 characters), 4 = long (351–1500 characters), 5 = very long (1501–5525 characters). On average, the user comments consisted of 1020 characters (min: 8 characters, max: 5952). In comparison interactive comments consisted of 734 characters on average (min: 8 characters, max: 5940 characters). Furthermore, the position of the comment in the discussion thread was calculated. We categorised all 903 comments into start (comment no. 1–301), middle (comment no. 302–602) and end of the thread (comment no. 603–903). It was also controlled for other forms of communication with regards to inclusive concepts of deliberation. A narrative from a personal or reported perspective was coded as storytelling. Witty, playful, or clearly not seriously meant statements that were supposed to make other users laugh were coded as humour. All control variables were binary re-coded.

Intercoder reliability. For the coding of most variables the full sample of user comments (N = 1216) has been split between five coders. The two independent variables constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions have been coded by three coders exclusively for the sample analysed in this study (N = 903). As common procedure in communication science, before both coding processes, a test set has been coded to validate the coding scheme (Krippendorff Citation2004, Citation2018). The test set for the first coding process included 62 comments. For the coding of constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions a test set of 40 comments was used. Intercoder reliability was measured using Holsti’s percentage agreement (PA) and Krippendorff’s α. The reliability scores for all categories led to satisfying results (Holsti Citation1969; Krippendorff Citation2004) reported in . All variables except respect (α = .66) had a Krippendorff’s α above .72, the overall Krippendorff´s α was = .80.

TABLE 2 Frequencies and intercoder reliability for all variables

Results

Overall, the sample contained 436 (48.2 per cent) interactive user comments. Among these interactive comments, there were 119 (13.2 per cent) showing insufficient deliberative quality, 286 (31.7 per cent) met the basic standards of restrictive deliberative listening (interactivity, argumentation, and respect) and 31 (3.4 per cent) comments met at least one extra characteristic of inclusive deliberative listening (communicative empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, and questions). In terms of expressions of emotions, 95 (10.5 per cent) comments expressed positive emotion and 221 (24.5 per cent) negative emotion, 237 (26.3 per cent) expressed constructive emotion and 78 (8.6 per cent) non-constructive emotion.

To answer the research question of how constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions affect inclusive listening, we computed the first regression model to examine the effect of constructive and non-constructive emotions on the full range of the Inclusive Listening Index (Model 1, ). The results show that while constructive expressions of emotions have a significant positive effect on the IncLI (b = .15, p < .05) non-constructive expressions of emotions have a negative effect (b = –.14, p < .1). However, the model also shows that the comment length had the strongest positive effect on IncLI: very long comments had a highly significant positive effect (b = .48, p < .001) and very short comments a highly negative effect (b = –.53, p < .001). Storytelling and humour, as well as the position of the comment in the thread, had no significant effect on IncLI.

TABLE 3 Regression Model 1 with constructive, non-constructive expressions of emotions

To answer the question of whether the distinction between constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions provides a better explanation of IncLI compared to the distinction between positive and negative emotions, we compared the first regressions model (Model 1, ) with a second model in which the variables constructive emotion and non-constructive emotion were replaced by positive emotion and negative emotion (Model 2, ). The results of Model 2 show a significant positive effect of negative emotions on IncLI (b = .13, p < .05) and no significant effect of positive emotions. Comparing the two models, the results show that the inclusion of constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions in the model leads to a significant increase in explained variance of IncLI (Alteration R2 = .016, p < .05), 27.4 per cent of the variance can be explained by Model 1 (). Compared to this, the inclusion of positive and negative emotions showed a lower explained variance (Alteration R2 = .008, p < .1): 26.6 per cent of the variance can be explained by Model 2 (). From this, it can be concluded that the distinction of constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions indeed provides a better explanation of inclusive listening than does the distinction between positive and negative emotions.

TABLE 4 Regression Model 2 with positive, negative expressions of emotions

Discussion

The aim of this study was threefold: First, the study suggested that the restrictive understanding of deliberative quality, as mainly respectful, reciprocal argumentation, should be expanded to capture deliberative quality triggered by expressions of emotions. To achieve this, an inclusive understanding of deliberative listening has been developed, including empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, and questions. Second, we drew attention to the research gap on the effects of different types of emotions in public deliberation. Previous research focused either on the existence or the valence of emotional expressions, providing contradictory results on their effect on interactive user comments. Against this background, we proposed the distinction between constructive emotions, that refer to the discussed issue, and non-constructive emotions, that refer to other participants. Thirdly, we constructed a graded Inclusive Listening Index (IncLI) to measure both restrictive and inclusive deliberative listening and applied it to user comments written by citizens in an online participation platform.

The results of the analysis show a significant positive effect of constructive emotions and a negative effect of non-constructive emotions on IncLI. The results also show that negative emotions have a positive effect on IncLI. The comparison of the two regression models demonstrates that constructive and non-constructive expressions of emotions when compared to positive and negative emotions provide a better explanation of the IncLI variance. Further, the analysis reveals that expressions of positive emotions, storytelling and humour have no significant effects on IncLI.

Some of the findings are consistent with previous studies, others are not. In line with this study, it has been demonstrated that a confrontational environment can coexist with the exchange of rational arguments (Balcells and Padró-Solanet Citation2016). Expressions of negative emotions showed positive effects on user engagement although previous studies only found them at a marginal level of significance (Esau, Frieß, and Eilders Citation2019; Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2019). Expressions of positive emotions have been found to have either positive effects on reciprocity (Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2019) or negative effects on both reciprocity and argumentation (Esau, Frieß, and Eilders Citation2019). Storytelling has been previously shown to have positive effects on the deliberative quality of interactive user comments (Black Citation2008a; Polletta and Lee Citation2006). Humour had a positive effect on the quantity of user comments (Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2019), but also was associated in a negative way with respect (Esau, Frieß, and Eilders Citation2019). Against this background, the distinction between constructive and non-constructive can not only be applied to expressions of emotions, but also to storytelling, and humour. However, future research would have to define what constructive and non-constructive storytelling and humour entails.

The findings of this study have implications for deliberative democracy theory and on the theoretical understanding of online deliberation. The most important result is the positive association between constructive expressions of emotions and listening. First, this demonstrates that emotions have a place inside deliberation and gives a guide as to which emotions these should be. The empirical evidence supports the idea to focus on the object of the emotion and with this contributes to a normative understanding of affective deliberation (Krause Citation2008). If expressions of emotions are not of the non-constructive type, they can be seen as an important factor that promotes “good deliberative listening” (Morrell Citation2018). Furthermore, the study shows that by coding interactivity, arguments, respect, empathy, reflexivity, constructiveness, and questions a reliable measurement of deliberative listening is possible. We believe that the IncLI is a good first step from the Discourse Quality Index (DQI) (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003) into the direction of a more inclusive measurement of overall DQ.

However, we also think that there are more criteria that can indicate good deliberative listening. For example, the plurality of interactions (Kies Citation2010). Especially when emotional reactions are expressed from different political standpoints, it is interesting to know whether the different sides are listening to each other. In the case of this study the online discussions had a high share of interaction across lines of political difference, which is in line with previous studies (Balcells and Padró-Solanet Citation2020; Stromer-Galley and Muhlberger Citation2009). For more criteria we suggest a look into Witkin and Trochim (Citation1997), where 98 distinct items related to the process of listening have been listed. However, a deliberative concept of listening that would take all possible items into account seems excessive. Instead, future research should examine the most promising items and aim for a core of deliberative listening variables.

Beyond theory, this study’s results provide implications for online participation practice. Moderators in online discussions could pay more attention to the reference point of emotional expressions and encourage participants to share their emotions on the discussed topic instead of expressing emotions related to other participants. However, to gain a deeper understanding of such discussion dynamics, future research should continue to provide more in-depth analysis of the content and structure of online deliberation through the combination of content and network analysis. Instead of using regression analysis to search for associations in the overall data, an alternative strategy that future studies could implement would be to examine various ideal types of emotional expressions directly in relation to the subsequent course of the discussion. Sequence analytical approaches will be fruitful for this.

In the end when it comes to the questions “what kind of emotion talk we should listen to” (Bickford Citation2011, 1026), and which contributions are sound (Krause Citation2008) we can conclusively say that expressions of emotion referring to others, that are aimed at humiliating speakers, shutting down voices and building coalitions against others have no place in deliberation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The article is the result of a joint effort of the authors. The research question, conception, design of the study, and most of the data collection were developed and carried out as part of the first author’s PhD project. She is grateful to Professor Christiane Eilders for her supervision and invaluable support in all stages of the project. The first author would also like to thank Sarah Nienhaus and Tanja Tix for their support in coding the data. The coding of “constructive vs non constructive emotions” and data analysis was carried out as part of a joint student project by Lena Wilms, Janine Baleis and Birte Keller and was supervised by the first author. We would like to thank Dr. Lala Muradova, Prof. Nicole Curato and Dr. Dannica Fleuß and the other participants of the ECPR 2019 panel on the role of emotions in public deliberation for their constructive comments on a first draft. Further, we want to thank the editor and anonymous reviewer for their important work in times of a pandemic.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All analysed online discussions were saved and annotated for the purposes of the research project and can be requested from the first author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katharina Esau

Katharina Esau is a postdoctoral research associate in the Digital Media Research Centre at the Queensland University of Technology. She conducted the research presented in this article at the University of Dusseldorf.

Lena Wilms

Lena Wilms is a research associate at the Dusseldorf Institute for Internet and Democracy. Email: [email protected]

Janine Baleis

Janine Baleis is a research assistant in the German Federal Parliament; former research associate (until 09/2020) at the Chair Communication and Media Studies I of the Institute of Social Sciences at University of Dusseldorf. Email: [email protected]

Birte Keller

Birte Keller is a research associate at the Chair Communication and Media Studies I of the Institute of Social Sciences at the University of Dusseldorf. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 We do not label all emotions related to other participants as destructive. It would be premature to do so. We think that our concept of non-constructive emotions is not closed to further theorising. At this point, we cannot be sure that certain emotions related to other participants in the discussion can be indeed constructive contributions to deliberation that we may have overseen. However, this warrants further discussion and thinking in another place.

2 https://www.leitentscheidung-braunkohle.nrw/; The online platform was shut down after the 2017 state elections and the change of government and is no longer publicly available. All user comments on the platform were saved and annotated for the purposes of the research project and can be requested from the first author.

3 These two variable characteristics have been coded by Janine Baleis, Birte Keller and Lena Wilms.

REFERENCES

- Aragón, Pablo, Vicenç Gómez, and Andreas Kaltenbrunner. 2017. “Detecting Platform Effects in Online Discussions.” Policy & Internet 9 (4): 420–443. doi:10.1002/poi3.158.

- Balcells, Joan, and Albert Padró-Solanet. 2016. “Tweeting on Catalonia’s Independence: The Dynamics of Political Discussion and Group Polarisation.” Medijske Studije 7 (14): 124–141. doi:10.20901/ms.7.14.9.

- Balcells, Joan, and Albert Padró-Solanet. 2020. “Crossing Lines in the Twitter Debate on Catalonia’s Independence.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (1): 28–52. doi:10.1177/1940161219858687.

- Barber, Benjamin R. 1984. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Barnes, Renee. 2015. “Understanding the Affective Investment Produced Through Commenting on Australian Alternative Journalism Website New Matilda.” New Media & Society 17 (5): 810–826. doi:10.1177/1461444813511039.

- Basu, Sammy. 1999. “Dialogic Ethics and the Virtue of Humor.” Journal of Political Philosophy 7 (4): 378–403. doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00082.

- Bächtiger, André, Simon Niemeyer, Michael Neblo, Marco R. Steenbergen, and Jürg Steiner. 2010. “Disentangling Diversity in Deliberative Democracy: Competing Theories, Their Blind Spots and Complementarities.” Journal of Political Philosophy 18 (1): 32–63. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00342.x.

- Bickford, Susan. 2011. “Emotion Talk and Political Judgment.” The Journal of Politics 73 (4): 1025–1037. doi:10.1017/S0022381611000740.

- Black, Laura W. 2008a. “Deliberation, Storytelling, and Dialogic Moments.” Communication Theory 18 (1): 93–116. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00315.x.

- Black, Laura W. 2008b. “Listening to the City: Difference, Identity, and Storytelling in Online Deliberative Groups.” Journal of Public Deliberation 5 (1): 1–35. doi:10.16997/jdd.76.

- Black, Laura W., Howard T. Welser, Dan Cosley, and Jocelyn M. DeGroot. 2011. “Self-Governance Through Group Discussion in Wikipedia: Measuring Deliberation in Online Groups.” Small Group Research 42 (5): 595–634. doi:10.1177/1046496411406137.

- Bohman, James. 1996. Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cohen, Joshua. 1989. “Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy.” In The Good Polity: Normative Analysis of the State, edited by Alan Hamlin and Philip Pettit, 17–34. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dahlberg, Lincoln. 2007. “The Internet, Deliberative Democracy, and Power: Radicalizing the Public Sphere.” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 3 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1386/macp.3.1.47_1.

- Damasio, Antonio R. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

- Dobson, Andrew. 2010. “Democracy and Nature: Speaking and Listening.” Political Studies 58 (5): 752–768. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00843.x.

- Dobson, Andrew. 2012. “Listening: The New Democratic Deficit.” Political Studies 60 (4): 843–859. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00944.x.

- Dryzek, John S. 2000. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dryzek, John S. 2010. “Rhetoric in Democracy: A Systemic Appreciation.” Political Theory 38 (3): 319–339. doi:10.1177/0090591709359596.

- Esau, Katharina. 2018. “Capturing Citizens’ Values: On the Role of Narratives and Emotions in Digital Participation.” Analyse & Kritik 40 (1): 55–72. doi:10.1515/auk-2018-0003.

- Esau, Katharina. 2022. Kommunikationsformen und Deliberationsdynamik. Eine relationale Inhalts- und Sequenzanalyse politischer Online-Diskussionen auf Beteiligungsplattformen [Communication Forms and Deliberation Dynamic]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Esau, Katharina, Dannica Fleuß, and Sarah-Michelle Nienhaus. 2021. “Different Deliberative Arenas, Different Deliberative Quality? Using a Systemic Framework to Evaluate Online Deliberations on Immigration Policy in Germany.” Policy & Internet 13 (1): 86–112. doi:10.1002/poi3.232.

- Esau, Katharina, and Dennis Friess. 2022. “What Creates Listening Online? Exploring Reciprocity in Online Political Discussions with Relational Content Analysis.” Journal of Deliberative Democracy 18 (1): 1–16. doi:10.16997/jdd.1021.

- Esau, Katharina, Dennis Friess, and Christiane Eilders. 2017. “Design Matters! An Empirical Analysis of Online Deliberation on Different News Platforms.” Policy & Internet 9 (3): 321–342. doi:10.1002/poi3.154.

- Esau, Katharina, Dennis Frieß, and Christiane Eilders. 2019. “Online-Partizipation Jenseits Klassischer Deliberation [Online Participation Beyond Classic Deliberation].” In Politische Partizipation im Medienwandel, edited by Ines Engelmann, Marie Legrand, and Hanna Marzinkowski, 221–245. Berlin: Digital Communication Research.

- Fischer, Agneta H., and Antony S. R. Manstead. 2016. “Social Functions of Emotion and Emotion Regulation.” In Handbook of Emotions, edited by Lisa Feldman Barrett, Michael Lewis, and Jeanette M. Haviland-Jones, 424–439. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Fraser, Nancy. 1990. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” Social Text 25/26: 56–80. doi:10.2307/466240.

- Gastil, John, and Laura W. Black. 2008. “Public Deliberation as the Organizing Principle of Political Communication Research.” Journal of Public Deliberation 4 (1): 1–47. doi:10.16997/jdd.59.

- Goodin, Robert E. 2000. “Democratic Deliberation Within.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 29 (1): 81–109. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.2000.00081.x.

- Graham, Todd. 2008. “Needles in a Haystack: A New Approach for Identifying and Assessing Political Talk in Nonpolitical Discussion Forums.” Javnost-The Public 15 (2): 17–36. doi:10.1080/13183222.2008.11008968.

- Graham, Todd. 2010. “The Use of Expressives in Online Political Talk: Impeding or Facilitating the Normative Goals of Deliberation?” In Electronic Participation. ePart 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, edited by Efthimios Tambouris, Ann Macintosh, and Olivier Glassey, 26–41. Berlin: Springer.

- Graham, Todd, and Tamara Witschge. 2003. “In Search of Online Deliberation: Towards a New Method for Examining the Quality of Online Discussions.” Communications 28 (2): 173–204. doi:10.1515/comm.2003.012.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. 1996. Democracy and Disagreement: Why Moral Conflict Cannot Be Avoided in Politics, and What Should Be Done About It. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. 2004. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1975. Legitimation Crisis. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action: Volume 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1994. “Three Normative Models of Democracy.” Constellations 1 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8675.1994.tb00001.x.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2005. Truth and Justification. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hall, Cheryl. 2005. The Trouble with Passion: Political Theory Beyond the Reign of Reason. New York: Routledge.

- Heiss, Raffael, Desiree Schmuck, and Jörg Matthes. 2019. “What Drives Interaction in Political Actors’ Facebook Posts? Profile and Content Predictors of User Engagement and Political Actors’ Reactions.” Information, Communication and Society 22 (10): 1497–1513. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1445273.

- Hendriks, Carolyn M., Selen A. Ercan, and Sonya Duus. 2019. “Listening in Polarised Controversies: A Study of Listening Practices in the Public Sphere.” Policy Sciences 52 (1): 137–151. doi:10.1007/s11077-018-9343-3.

- Himelboim, Itai. 2008. “Reply Distribution in Online Discussions: A Comparative Network Analysis of Political and Health Newsgroups.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14 (1): 156–177. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.01435.x.

- Hoggett, Paul, and Simon Thompson. 2002. “Toward a Democracy of the Emotions.” Constellations 9 (1): 106–126. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00269.

- Hoggett, Paul, and Simon Thompson, eds. 2012. Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies. New York: Continuum.

- Holsti, Ole R. 1969. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Janssen, Davy, and Raphaël Kies. 2005. “Online Forums and Deliberative Democracy.” Acta Politica 40 (3): 317–335. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500115.

- Jaramillo, Maria Clara, and Jürg Steiner. 2014. “Deliberative Transformative Moments: A New Concept as Amendment to the Discourse Quality Index.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10 (2): 1–22. doi:10.16997/jdd.210.

- Keltner, Dacher, and Jonathan Haidt. 1999. “Social Functions of Emotions at Four Levels of Analysis.” Cognition & Emotion 13 (5): 505–521. doi:10.1080/026999399379168.

- Kies, Raphaël. 2010. Promises and Limits of Web-Deliberation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Krause, Sharon R. 2008. Civil Passions: Moral Sentiment and Democratic Deliberation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. “Reliability in Content Analysis.” Human Communication Research 30 (3): 411–433. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lazarus, Richard S. 1991. Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- LeDoux, Joseph E. 1996. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1991. Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Academic Publishing.

- Mansbridge, Jane, Janette F. Hartz-Karp, Matthew Amengual, and John Gastil. 2006. “Norms of Deliberation: An Inductive Study.” Journal of Public Deliberation 2 (1): 1–47. doi:10.16997/jdd.35.

- Marcus, George E. 2003. “The Psychology of Emotion and Politics.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by David O. Sears, Leonie Huddy, and Robert Jervis, 182–221. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marcus, George E., W. Russel Neuman, and Michael MacKuen. 2000. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Monnoyer-Smith, Laurence, and Stéphanie Wojcik. 2012. “Technology and the Quality of Public Deliberation. A Comparison between on and Offline Participation.” International Journal of Electronic Governance, 5 (1): 24–49.

- Morrell, Michael E. 2010. Empathy and Democracy: Feeling, Thinking, and Deliberation. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Morrell, Michael E. 2018. “Listening and Deliberation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren, 237–250. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nishiyama, Kei. 2018. “Enabling Children’s Deliberation in Deliberative Systems: Schools as a Mediating Space.” Journal of Youth Studies 22 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1080/13676261.2018.1514104.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2015. Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- O’Neill, John. 2002. “The Rhetoric of Deliberation: Some Problems in Kantian Theories of Deliberative Democracy.” Res Publica 8: 249–268. doi:10.1023/A:1020899224058.

- Pedrini, Seraina, André Bächtiger, and Marco R. Steenbergen. 2013. “Deliberative Inclusion of Minorities: Patterns of Reciprocity Among Linguistic Groups in Switzerland.” European Political Science Review 5 (3): 483–512. doi:10.1017/S1755773912000239.

- Polletta, Francesca, and John Lee. 2006. “Is Telling Stories Good for Democracy? Rhetoric in Public Deliberation After 9/11.” American Sociological Review 71 (5): 699–721. doi:10.1177/000312240607100501.

- Roald, Vebjørn, and Linda Sangolt. 2011. Deliberation, Rhetoric, and Emotion in the Discourse on Climate Change in the European Parliament. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers.

- Saam, Nicole J. 2018. “Recognizing the Emotion Work in Deliberation. Why Emotions Do Not Make Deliberative Democracy More Democratic.” Political Psychology 39 (4): 755–774. doi:10.1111/pops.12461.

- Sanders, Lynn M. 1997. “Against Deliberation.” Political Theory 25 (3): 1–17. doi:10.1177/0090591797025003002.

- Steenbergen, Marco R., André Bächtiger, Markus Spörndli, and Jürg Steiner. 2003. “Measuring Political Deliberation: A Discourse Quality Index.” Comparative European Politics 1 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110002.

- Steiner, Jürg, Maria Clara Jaramillo, Rousiley C. M. Maia, and Simona Mameli. 2017. Deliberation Across Deeply Divided Societies: Transformative Moments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stenetorp, Pontus, Sampo Pyysalo, Goran Topić, Tomoko Ohta, Sophia Ananiadou, and Jun’ich Tsujii. 2012. “BRAT: A Web-Based Tool for NLP-Assisted Text Annotation.” In Proceedings of the Demonstrations at the 13th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 102–107. Avignon.

- Strippel, Christian, Laura Laugwitz, Sünje Paasch-Colberg, Katharina Esau, and Annett Heft. 2022. “BRAT Rapid Annotation Tool.” M&K Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 70 (4): 446–461. doi:10.5771/1615-634X-2022-4-446.

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2007. “Measuring Deliberation's Content: A Coding Scheme.” Journal of Public Deliberation 3 (1): 1–31. doi:10.16997/jdd.50.

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer, and Peter Muhlberger. 2009. “Agreement and Disagreement in Group Deliberation: Effects on Deliberation Satisfaction, Future Engagement, and Decision Legitimacy.” Political Communication 26 (2): 173–192. doi:10.1080/10584600902850775.

- Walton, Douglas. 1992. The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wilhelm, Anthony G. 1998. “Virtual Sounding Boards: How Deliberative Is On-Line Political Discussion?” Information, Communication & Society 1 (3): 313–338. doi:10.1080/13691189809358972.

- Witkin, Belle Ruth, and William W. K. Trochim. 1997. “Toward a Synthesis of Listening Constructs: A Concept Map Analysis.” The International Journal of Listening 11 (1): 69–87. doi:10.1207/s1932586xijl1101_5.

- Young, Iris Marion. 1997. “Asymmetrical Reciprocity: On Moral Respect, Wonder, and Enlarged Thought.” Constellations 3 (3): 340–363. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8675.1997.tb00064.x.

- Young, Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ziegele, Marc, Timo Breiner, and Oliver Quiring. 2014. “What Creates Interactivity in Online News Discussions? An Exploratory Analysis of Discussion Factors in User Comments on News Items.” Journal of Communication 64 (6): 1111–1138. doi:10.1111/jcom.12123.

- Ziegele, Marc, Oliver Quiring, Katharina Esau, and Dennis Friess. 2020. “Linking News Value Theory with Online Deliberation: How News Factors and Illustration Factors in News Articles Affect the Deliberative Quality of User Discussions in SNS’ Comment Sections.” Communication Research 47 (6): 860–890. doi:10.1177/0093650218797884.