Abstract

Public Service Media remains at the centre of the public sphere in Northern Ireland. Public Service Media organisations such as the BBC broadcast in a society that remains politically and culturally divided. This has been the case for decades, even if the worst of the violence in Northern Ireland has now dissipated. The Northern Ireland media system includes local media provision, along with provision from the rest of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. This article identifies Northern Ireland’s media system as sharing characteristics with what Puppis (2009) defines as a small media system, under slightly different conditions. This article takes a Critical Political Economy approach to Public Service Media organisations operating in Northern Ireland, in order to argue that while there is prominence in the place of PSM in the media system, there is also vulnerability inherent.

Introduction

Public Service Media (PSM) (Donders Citation2021) remains at the centre of the public sphere in Northern Ireland (NI), with PSM making a crucial contribution to news and journalism, the arts and broader culture. PSM services remain very popular within NI, and reach a very large proportion of the population on a weekly basis. Despite this, there are a few areas where the PSM organisations’ (PSMs) performance and delivery in NI are underperforming. This article commences by addressing the history of broadcasting in NI, and the current social and political context that means that broadcasting still operates in a divided society. This article identifies NI’s media system as sharing characteristics with what Puppis (Citation2009) defines as a small media system, under slightly different conditions. Having outlined the analytical framework, the article then proceeds to an assessment of PSM services in NI. To do so, empirical data is analysed, and set into context. The article argues that while PSM remains very prominent in NI, it is vulnerable in various ways.

Public Service Media in Northern Ireland—History, Contemporary Conditions and Theory

Public Service Broadcasting (PSB)—the forerunner of PSM—has existed in NI since 1924. BBC radio was first broadcast from September 1924, with television following from 1953 onwards (BBC Citation2023a). As was the case across the UK, the BBC had the monopoly on television broadcasting until the 1954 Television Act: Ulster Television (UTV) was then broadcast on Channel 3 from 1959 onwards (Lafferty Citation2014). Two areas will be covered in this section: first, a brief history of broadcasting in NI will be set out, and the characteristics of the divided society that PSM operates in will be outlined; second, the theoretical framework will be further developed with reference to media systems in small nations.

The origins of PSB in NI occurred almost conterminously with the establishment of the state. Following centuries of conflict, the partition of Ireland gave way to new constitutional arrangements on the island, with NI established in 1921. However, as NI was in the words of one of its Prime Ministers, James Craig, to be “a Protestant Parliament and Protestant State” (CAIN Citation2023), it was mired in social strife. This was partly due to the levels of discrimination faced by the minority Catholic-Nationalist community. Subsequently, the Civil Rights movement from the 1960s attempted to bring about a change in living and working conditions for this group. The Troubles—that period of conflict from the late 1960s to the late 1990s, that saw some 3500 people killed—largely ended with the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. However, given instability in the devolution settlement that followed, and sporadic violence—with a number of high-profile sectarian murders (Community Relations Council Citation2018)—means that NI exists to the present day in a very uneasy settlement. For example, NI retains many aspects of social, cultural and administrative division (Nagle Citation2022; Ramsey and McDermott Citation2020) such as in schooling and housing. As Hayward, Komarova, and Rosher (Citation2022) show, NI is a society in transition in areas such as on national identity and in relation to public opinion on its constitutional future, though support for Irish reunification still trails that of support for remaining in the UK. Later this article will return to this theme, when addressing the prospects for PSM in a potentially reunified Ireland.

The recent political history of NI has been a turbulent one. The devolved institutions that were setup following the 1998 Good Friday Agreement to enable cross-community power-sharing have been continually in flux. NI’s devolved Executive and Assembly were most recently suspended between January 2017—January 2020 and February 2022—February 2024, periods during which one or other of the main political parties pulled out of power-sharing. Since 1998, there has been more than ten years when the institutions have not functioned. When power-sharing was restored in 2024, an Irish Nationalist took position of First Minister for the first time in history. While technically first elected to the role in May 2022, Michelle O’Neill MLA of Sinn Féin had to wait until 2024 to take up the position due to the impasse. O’Neill’s status as First Minister is largely symbolic, as the office is jointly held with the Democratic Unionist Deputy First Minister—and yet, what it represents in a changing NI is seismic, given that it when it was established it was designed to have a permanent Unionist hegemony (Garry, Brendan, and Pow Citation2022).

The lack of a functioning democracy in NI throughout various periods means that local opportunities have been missed for government and the legislature to feed into various aspects of the broadcasting regulatory process. For example, an MOU from 2015 gives the NI Executive and NI Assembly a part to play in BBC Charter renewal (McCallion Citation2021; UK Government Citation2015), and when these institutions do not function they are not able to play the full role afforded to them. More generally, when the NI Assembly is running, politicians have questioned BBC Executives in the past in committee formats (see Ramsey Citation2015). Now devolved government has been restored, the NI Assembly may yet come to play a role in relation to media policy, but recent experience regarding the lack of stability in devolved government means there have been sizeable gaps in this democratic provision.

As a theoretical frame through which to view PSM in NI, we can situate it as a place where PSM operates in a divided society (Ramsey Citation2016; Reilly Citation2021; Rice and Taylor Citation2020; Citation2023). In this environment, the BBC’s position as the “British” public broadcaster has come under pressure from all sides since its inception. This was especially the case as the Troubles commenced, as successive British Governments sitting in London felt the Corporation should represent the interests of the British state—in the mould of a state broadcaster, as opposed to that of a public service broadcaster. Throughout the Troubles, there were a number of standout incidents, where the Corporation’s activities came under intense scrutiny (Savage Citation2022; Seaton Citation2017). In some senses NI today still bears the legacy of these days; the way the BBC reports on almost all matters of public importance is subject to near-continual scrutiny—a phenomenon that extends to the media more generally (e.g. Rice and Taylor Citation2023). For PSM, this is not a unique or unusual situation: instead, PSMs operate in many countries, regions and territories around Europe and further afield under similar conditions of division (Harding Citation2015). Indeed, in places such as Belgium, Spain (in the autonomous region of Catalonia), Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia, where there are variously linguistic, social, ethnic and cultural divisions, PSM operations continue to serve their communities (see Ramsey Citation2016, 147 for an overview). In NI, specific provision is made for minority language provision in Irish and Ulster-Scots, with various funding schemes operating that intersect with NI’s broader policies in relation to minority languages (Ramsey and McDermott Citation2020, 451–453).

Methodology and Analytical Framework

The methodological approach taken in this article is qualitative document analysis (Atkinson and Coffey Citation2004), through the use of a Thematic Analysis approach (Herzog, Handke, and Hitters Citation2019) to a series of policy reports, statistical reports, broadcaster annual reports and corporate webpages. This article primarily draws on the evidence that Ofcom gathers through its UK-wide Media Nations (Ofcom Citation2023a) and NI-specific Media Nations: Northern Ireland (Ofcom Citation2023b) publications. It also addresses a range of other documentation (total n = 21), in order to examine trends and highlight policy directions, to contribute to a critical policy studies analysis (Cairney Citation2021) on the place of PSM in NI’s media system. In conducting this analysis, the framework is driven by a critical political economy (CPE) approach to media and communication, in terms of how “the political and economic organisation […] of media industries affects the production and circulation of meaning, and connects to the distribution of symbolic and material resources that enable people to understand, communicate and act in the world” (Hardy Citation2014, 9). As such, this article addresses how regulatory structures give rise to a certain organisation of providers, where PSM remains very prominent. In the field of media policy studies, CPE approaches have been used to “place significant attention on systems, infrastructures and processes, and are highly useful in identifying their effects” (Picard Citation2020, 192). This article will commence its analysis of the media system in NI with a focus on the effects of the regulatory system, as seen in PSM provision for NI. News and current affairs as a broader subject—i.e. Taking into consideration newspapers (both print and online)—is not a key consideration in the article, given the focus on PSM services themselves. The subject does factor later in the discussion in part, but for a wider analysis of this see Ramsey (Citation2023).

Northern Ireland as a Small Media System?

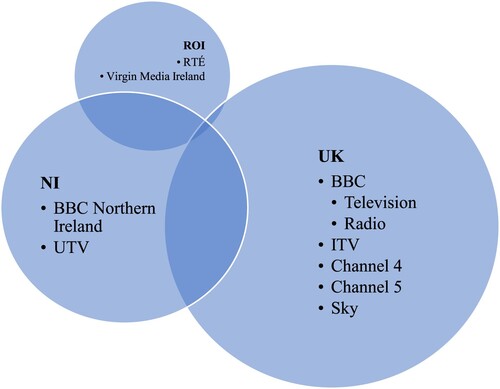

When analysing NI’s media system, the first research obstacle is to locate it vis-à-vis the UK and the ROI media systems, as NI sits at the intersection of the two nation states.Footnote1 This is an under researched area, as most research addresses NI simply within the UK, or addresses the island of Ireland, but without referring to media systems. One way to proceed is to view NI’s media system partly through the prism of media systems in small states. Initially, it is important to say that NI is a region with a population of almost 2 million, which is part of the UK with a population of 67 million people. And yet, it also inhabits the island of Ireland alongside the ROI. In that regard, the NI media system is not one which functions at the level of its own nation state; rather NI audiences consume content that comes principally from two national media systems (the UK and the ROI), and one (regional) “small media system” (locally-based television, radio and news provision). Turning to Puppis (Citation2009, 10–11), who outlines four characteristics of small media systems, allows for an analysis of aspects of the NI media system, allowing for the elucidation of various key political-economic features within it: (i) Shortage of resources; (ii) Small audience markets and small advertising markets; (iii) Dependence; (iv) Vulnerability. Viewing NI within the four-fold Puppis framework, the following observations can be made with particular reference to PSM:

On (i), a ‘shortage of resources’, this is somewhat true of NI media system, at least in terms of local media resources. However, this is ameliorated given how embedded the NI media system is into the wider UK media system, with BBC funding in particular injecting a very significant amount of money (see below, £109 m). NI is served by four main UK-based PSMs: BBC, UTV (under its parent company ITV), Channel 4 and Channel 5. Other major UK broadcasters such as Sky/Comcast NBCUniversal then also compete with the main Subscription Video-on-Demand (SVoD) platforms, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video. The BBC in NI one of the Corporation’s “nations” services and operates out of its own headquarters. BBC One Northern Ireland and BBC Two Northern Ireland are channels which broadcast both network and local opt-out programming (i.e. that which is commissioned and made for NI audiences). NI audiences access the other network television channels (e.g. BBC Four), but they have no opt-outs. On radio, BBC Radio Ulster (all of NI) (and BBC Radio Foyle, aimed at the Derry-Londonderry region) operates at the level of “nations stations,” akin to BBC Radio Scotland and BBC Radio Wales. Audiences then have access to all other BBC network radio stations (e.g. BBC Radio 4) and BBC Sounds. UTV is the main commercial PSM in NI, as owned and operated by ITV plc in 2015. Finally, Channel 4 and Channel 5 both broadcast in NI, with their catch-up services operating on the same basis as the rest of the UK (see ). As discussed later in this article, reporting of their NI-based activities is very limited, though both do spend on PSM services in the region. As such, there is no particular shortage of resources at the macro level. Puppis (Citation2009, 10) also identifies a shortage of “professionals in the media” in this category, and on that point NI has a very small pool of media professionals working in TV and radio broadcasting (though its film and television production sector is burgeoning).

TABLE 1 SVoD and BVoD Usage in NI – 2023

On (ii), an ability to gain from economies of scale in the context of “small audience markets and small advertising markets,” this point can be said to apply variously depending on whether or not the national or regional picture is being addressed: nationally, NI benefits from being part of a UK-wide advertising market (in 2022 the television advertising market alone was worth £5.4bn) (Ofcom Citation2023a, 4). However, regionally, the advertising market is mature, yet ultimately quite small (though as noted below, commercial radio revenues in NI are high on a per capita basis).

On (iii), Puppis (Citation2009, 11) points out that in relation to dependence that “political decisions of bigger neighbour states and the EU tend to influence the media systems and the media regulation of small states without taking their peculiarities into account.” In the case of NI, this point applies to an extent: in particular, as broadcasting powers are not devolved to NI (Ramsey Citation2015) and so it entirely relies on the UK for setting the legislative and regulatory framework that broadcasting can operate within. But as it is not a state in its own right, it is technically not dependent in the same way.

Finally, on (iv), in terms of vulnerability, Puppis (Citation2009, 11) outlines areas such as through “foreign takeover” of broadcasters, or through how “national media” tend to conform to foreign media. In these regards, these points do not well apply to NI. However, as Puppis (Citation2009, 11) also refers to broadcasts into the small state from a larger neighbouring country, there is a point to be made here about the availability of ROI television and radio consumption in NI. At present there is a series of legislative and policy arrangements, and informal fixes, which allow for consumption of broadcasting content from each jurisdiction on either side of the Irish border (Ivory Citation2014; Ramsey Citation2015). Later in this article this point is returned to, in order to discuss how PSM might be organised in the event of Irish reunification. Getting reliable data for the extent to which this happens is difficult, but used to be more accessible: for example, Ofcom (Citation2018, 19) noted that the four main Irish channels—RTÉ1, RTÉ2, TV3 (which later became Virgin Media One) and TG4—had between 33% and 21% of the NI population watching them at least monthly. Similarly, in that report, 9% of radio listening in NI was to stations in the “other” category, which excludes all UK or NI radio provision (Ofcom Citation2018, 39)—the vast majority of this (some 6 percentage points higher than the UK average). This can be clearly attributed as being listening to ROI stations, though it is not within Ofcom’s remit to say that. However, within the context of Puppis’ point on vulnerability, the NI media system is not really made vulnerable by cross-border media consumption. Indeed, as illustrated in , there is a great disparity in the extent to which the UK’s media system intersects with that of NI’s, as compared to the ROI. In terms of broadcast provision, it is either NI-based television and radio services or UK-based television and radio services which predominate.

As things are currently constituted, there are two national media systems (the UK and the ROI) and one regional media system. However, this picture would dramatically change in the event of a future referendum leading to Irish reunification. While there is no firm prospect that such a referendum will happen in the short term, such a vote in the medium-to-long term is a distinct possibility. Currently, there is policy and academic lacuna on how PSM would be constituted in such an event, and so it is apposite for policy options to be set out. As noted above, there is cross-border consumption of services from the opposite jurisdiction on the island of Ireland. While the Good Friday Agreement, and subsequent policy agreements and collaborative working solutions between the UK and ROI have ensured that the broadcast services from TG4 and RTÉ remain accessible in NI, BvoD services can differ: while most programmes on the RTÉ Player are accessible in NI, RTÉ advises that “some RTÉ programming is restricted to the Republic of Ireland or Island of Ireland for rights or legal reasons” (RTÉ Citation2023). But a fundamental question remains as to how PSM would constituted in a reunified Ireland: would RTÉ be granted the assets of BBC NI, with the latter subsumed into the former?; would an entirely new PSM be established?; how would funding operate, with the current funding settlement for RTÉ massively compromised (BBC News Citation2023a)? Noting from below that the BBC currently spends 111% of what it receives in licence fee income in NI, it is highly unlikely that this would be replicated in any new all-Ireland service.

The closest approximation for what could happen in a reunified Ireland comes from the Scottish Government’s (Citation2013) White Paper on how PSM would have been setup in an independent Scotland (which didn’t come to pass following the 2014 referendum). At that stage it was suggested that a new PSM would have been set up—the Scottish Broadcasting Service (SBS)—which “initially [would have been] based on the staff and assets of BBC Scotland” (Scottish Government Citation2013, 20). It was envisaged that the service would have been licence fee funded, but through working with the BBC as a “joint venture” Scottish audiences could have access to BBC programming such as EastEnders (Scottish Government Citation2013, 20). It is perhaps instructive that at that point it was suggested that the SBS would “inherit” (Scottish Government Citation2013, 318) a proportion of the BBC’s commercial ventures and the profits that they generate. It is possible that such a situation could be proposed for the case of a reunified Ireland. However, it is worth noting that the NI population is just over one-third of the size of Scotland’s population, so NI would inherit a much smaller proportion than an independent Scotland might have done. Any new PSM being setup to serve the whole island of Ireland would face massive if not insurmountable challenges: these would include issues of resourcing and finance. As noted, this is unlikely to be a short-term issue, but possibly affects the future of PSM as currently constituted in NI.

PSM Services in Northern Ireland

To better understand the functioning of PSM services in NI, we now turn to an analysis of how PSM is currently performing and delivering, in the areas of television, radio and streaming platforms. Following that, we turn to some of the outcomes from the current regulatory system.

Television

PSM consumption on television in NI is broadly in line with the wider trends across the UK. While linear television viewing is falling as a whole, PSM’s share within this remains very significant (Ofcom Citation2023a). In NI, PSM television channels have an audience share of just more than half (52.5%) (Ofcom Citation2023b, 13). Within this, viewing is dominated by BBC One and UTV, with BBC Two, Channel 4 and Channel 5 making up a much smaller proportion of the total. However, UTV’s share of the total is higher in NI than the ITV channels in England and Wales, and STV in Scotland (STV), reflecting the long-standing appetite for UTV/ITV services in NI; by contrast, BBC One’s share is lower in NI than in the other nations (Ofcom Citation2023b, 14). Satisfaction rates for the PSM channels in NI remain strong, with 69% of those who watch PSM on a regular basis stating they are “very” or “quite” satisfied (Ofcom Citation2023b, 14), which is comparable to figures from the rest of the UK. Overall, PSM television is very prominent within the NI media system, with substantial reach and audience satisfaction.

Radio

Radio listening trends in NI are something of an outlier compared to the rest of the UK—a phenomenon that has been the case for some years (see Ramsey Citation2016). Generally, radio in NI reaches a higher proportion of the population (91.6%) than anywhere else in the UK (average: 88.2%). Moreover, commercial radio revenues on a per capita basis are substantially higher in NI (e.g. £10.39 per capita in NI; £4.99 per capita in Wales) (Ofcom Citation2023b, 32). The reach of local commercial radio and BBC nations/local radio are both substantially higher than elsewhere in the UK, which comes at the expense of listening to BBC Network Radio (e.g. BBC Radio 4), and national commercial stations (Ofcom Citation2023b, 33). The main BBC radio station in NI, Radio Ulster has a weekly reach of 29.6% (market share: 18.1%), while the leading regional commercial radio station Cool FM has a weekly reach of 31.7% (market share: 12.3%) (Ofcom Citation2023b, 34). Taking BBC Radio services collectively, these reach 55% of those in NI over the age of 16 each week (BBC Citation2023b, 162), and so the Corporation’s radio offering in NI has a large reach. Overall, PSM radio is the central player in NI’s media system, albeit alongside a strong commercial radio presence.

Streaming Platforms

The growth of SVoD services globally has been matched in NI, with 68% of households subscribing to at “least one” service (Ofcom Citation2023b, 16),Footnote2 a fall of 2% percentage points since the previous year. Broadcast Video on Demand (BVoD) services is used extensively in NI, with the BBC iPlayer reaching 80% of people in NI over the age of thirteen (Ofcom Citation2023b, 18). The usage of the iPlayer in NI is eleven percentage points ahead of Netflix. Comparing other SVoDs and BVoDs in order of popularity in NI, Amazon Prime Video is used by 56% of the population, with ITVX used by 52% (See ). Overall, the notion that the BVoDs are still competing so strongly with the SVoDs, runs very strongly counter to what we could call the “Netflix narrative”—the notion that the global streamers have swept all before them, and that PSM is therefore obsolete.

Regulatory Outcomes

Having addressed the performance of PSM services in NI, in terms of audience consumption, and audience perception, and the way in which the PSMs are continuing to compete strongly with the SVoDs, we now turn to the outcomes from the regulatory framework that the PSMs operate within. As noted in the methodology, CPE is useful for “identifying [the] effects” of regulatory systems and frameworks. In this section we turn to the effects of the UK PSM regulatory framework, in the areas of how it relates to programming made for NI, and made from NI intended for the rest of the UK. To apply this approach, one key area is to address the regulatory category of “first-run UK originations,” which is a key area where it can distinguish itself from other non-PSM broadcasters. Indeed, it is an area that reveals the extent to which PSM providers are contributing on the characteristic that PSM be “original” (Ramsey Citation2017). This category is defined by those programmes which are those “commissioned by or for a licensed public service channel with a view to their first showing on television in the United Kingdom in the reference year” (Ofcom Citationn.d.). In other words, monitoring the performance of PSMs in the first-run UK originations category helps to reveal the extent to which they are delivering the kinds of content which substantially differentiates them from other non-PSMs, such as commercial rivals.

In the made for NI category 2022 data shows a 16% increase on the previous year in spending on content for audiences in NI (Ofcom Citation2023b, 21). However, as shown in , across the period 2016–2022 there has been a fluctuation in spending in this category, with spending now below the 2019 peak (Ofcom Citation2023b, 22). At the BBC and ITV/UTV, spending in this category has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels. When addressed in terms of hours of production in the category, BBC first-run originations for NI audiences have fallen 11% since 2016; while at UTV there was a more marginal fall of 2.5% ().

TABLE 2 First run spending and hours produced for NI – annually

Though the BBC and UTV’s operations in NI are vastly larger than the activities of Channel 4 and Channel 5, it is nevertheless worthwhile addressing their position within the NI media sytem—in line with Picard’s (Citation2020, 192) assertion that CPE allows placing “significant attention on systems, infrastructures and processes.” Channel 4 announced a two-year partnership with screen support body NI Screen in June 2022, in order to “help forge stronger ties between Northern Ireland indies and Channel 4’s commissioners” (Channel Citation4 Citation2022)—in other words, leading to a sectoral development role for the PSM. This partnership led to two programmes being commissioned in 2023 (McLaughlin Citation2023). Channel 4, like the other PSMs, spends its budget partly on a regional basis. Of the £713 m spent on content by Channel 4 in 2022, £228 m of this was spent in the outside of London (Channel Citation4 Citation2023, 28). In the “originated content” category of spending in Scotland, Wales and NI (£45 m), £5 m of this was spent in NI—which equates to 11.2% of all spending in this category (Channel Citation4 Citation2023, 84). However, NI makes up 18% of the UK’s population distributed among the nations,Footnote3 and so NI is underrepresented in this category.

In the case of Channel 5, it increased hours and spending on “qualifying network production in Northern Ireland” from 2021–2022 (Ofcom Citation2023b, 27). However, there is overall very limited information published by the broadcaster in relation to its activities in NI. The broadcaster refers to its activities around “Made Outside of London/Regional productions” on its parent company Paramount’s corporate website (Paramount Citation2023), but there is no NI-specific information provided. More generally, there is in fact a dearth of information published by both broadcasters regarding the detail of how they operate in NI, though the Channel 5 situation is more pronounced than the case of Channel 4.

Another key area for scrutiny relates to how much content is the made from NI—that is productions made for the PSMs for UK-wide consumption. In this area, NI makes a tiny fraction of such content: while the NI population makes up 2.8% of the wider UK population (ONS Citation2022),Footnote4 the 1.5% of hours and 2.1% of spending, as “Proportion of qualifying network hours and spend outside London, all PSBs combined” (Ofcom Citation2023b, 26) means that NI is somewhat under-represented in the network activities among the PSMs. For the BBC specifically, “as a percentage of eligible spend,” 3.9% of the BBC’s network television budget was spent in NI (while 4% of “PSB staff”—i.e. those working in licence fee funded jobs—are based in NI) (BBC Citation2023b, 34–35). In its submission to Ofcom’s Small Screen: Big Debate, the Ofcom Advisory Committee for Northern Ireland (Citationn.d.) addressed the point that the NI population is underrepresented in network production in NI, stating: “We believe that there is every reason at this stage to set more stretching targets for production spend in NI by the PSBs and develop the conditions in which these can be delivered.” That said, while the BBC estimates it collects £98 m in licence fees from NI, it spends £109 m on services there (BBC Citation2023b, 164), which equates to the Corporation spending 111% of what it receives in licence fee income.

Among the reported network production spending, we can also question how “qualifying network production” is defined. For example, Ofcom stated that the BBC programme Sunday Morning Live “returned to Belfast in 2022 after two years of being managed in Manchester” (Ofcom Citation2023b, 27, my emphasis). While the programme is edited and produced from Belfast by Tern TV Belfast and Green Inc, it is “broadcast live from a London studio, using producers and directors in Glasgow, Manchester and Sheffield” (Bell Citation2022), and as such saying that it “returned” to Belfast needs context given. Production companies are required to meet two out of three criteria set out in the relevant regulatory guidelines (Ofcom Citation2019, 2): for Sunday Morning Live, the programme meets the criteria and is allocated to NI under “Substantive base region” and “Off-screen talent region” (Ofcom Citation2022b, 23). As such, a production company can comply with these conditions, and the work be counted within the “qualifying network production in Northern Ireland” figures, despite being physically broadcast from London. In short, further analysis is required of the headline figures in order to fully ascertain which elements of a programme are being produced in what location—so as to better appreciate the actual geographical spread of PSM production.

Wider Issues Regarding the BBC in Northern Ireland

BBC Northern Ireland (BBC NI)—as the dominant PSM—is an organisation somewhat in flux. The addition of Michael Smyth as a Non-Executive Director to the BBC Board (Member for Northern Ireland) (HM Government Citation2023) was a major step forward for PSM in NI. As this role had been left unfilled since 2017, this had left NI under-represented as a region within the wider BBC in governance terms. BBC NI has endured a turbulent time in the past 3–5 years, which has included a highly publicised employment tribunal related to one of its best-known female presenters, Donna Traynor. It faces a range of other issues that mainly relate to the near-continuous accusation that the BBC in NI over-represents one side of the community over the other, fails to be impartial in its coverage, or contributes to community division rather than alleviating it. Much of the opprobrium is focused on the activities of the Corporation’s Stephen Nolan,Footnote5 and his radio programme The Nolan Show (and to a lesser extent, Nolan Live, which airs on television). Key moments over the last few years have included radio show boycotts by both Sinn Féin and the SDLP (NI’s two leading Nationalist parties), Nolan winning significant damages after libel judgements against two Twitter users (Erwin Citation2021), and the announcement in July 2023 that the radio show would be subject to a content review (Graham Citation2023)—though this is not an exhaustive list. Much of the situation around Nolan’s role at the BBC NI and in the wider public sphere is debated in a highly politicised and charged environment, and it is exceptionally difficult to untangle genuine concerns from political point scoring given the wider divided and fractious nature of politics in the region. For his part, Nolan has offered various defences of his role in the public sphere, telling the Irish News:

People convince themselves that I’m doing particular stories about one side of the community until the next day or the next month, when I’ve moved onto the other side. For anyone to suggest I favour one side over the other is ludicrous. (Nolan as cited in Coleman Citation2021)

Indeed, BBC services are extensively consumed in NI, with 84% of adults in NI consuming some aspect of BBC content, and 60% consuming content made by BBC NI in any given week (BBC Citation2023b, 32). The 84% weekly reach makes it “the most used brand for media in Northern Ireland” (BBC Citation2023b, 162). On issues of perception, the BBC in NI is rated highly by the public in categories such as on the extent to which it delivers on its mission of informing, educating and entertaining people (64% effective, 14% ineffective); on the extent to which audience think the BBC reflects “people like them” (53% effective, 20% ineffective); and on the extent to which the audience thinks the BBC sets high standards in terms of the quality of its content and services (61% effective, 15% ineffective) (BBC Citation2023b, 162).

Discussion and Conclusion

Having scrutinised a range of factors in relation to PSM in NI, we now turn to a discussion of the implications of what has been set out. In so doing, we can see that while there is prominence in the place of PSM in the media system, there is also vulnerability (Puppis Citation2009, 11) inherent:

As we have seen, PSM (originally PSB) began at roughly the same time as NI was created, a little over one hundred years ago, and so the histories of the two entities are shared, and intertwined. While NI was created to be a “Protestant State” (Craig as cited CAIN Citation2023) for a Unionist people, today it has an Irish Nationalist First Minister. Despite much social change, NI remains divided in many ways, and it is in that space that PSM services operate. Yet despite this context, on perception rates among NI audiences are as good if not better than they are in Scotland and Wales: e.g. in the “effective at reflecting people like them,” the NI population thinks the BBC is marginally more effective at this than audiences do on the same measurement in the two other nations (BBC Citation2023b, 154, 158, 162). In terms of BBC consumption levels, and on how it competes with the SVoDs, it remains noteworthy that the Corporation still garners such high levels. This is despite the continual refrain in large sections of the British Press that the BBC, and the wider concept of PSM, is obsolete (Ramsey Citation2023, 4–5), in an environment where PSM services are often written off by their critics as being irrelevant (e.g. Hoffman Citation2023).Footnote6 Rather, on the whole, people want more, not less of the BBC in NI; they want a Corporation that produces locally relevant content, that reflects their community. This may seem counterintuitive, and yet the data bears this out. In terms of the overwhelming majority of BBC NI’s ongoing output, there is no groundswell of opposition to it, and no great clamour for the BBC to be greatly reduced—or even abolished—in NI. This can be evidenced in many ways, but not least in the way that when changes at BBC Radio Foyle were announced, amounting to cut backs, there was a very significant amount of opposition locally (BBC News Citation2023b). Moreover, while consumption of PSM does of course not necessarily equate approval or support for the provider, nevertheless it is arguable that audiences would switch off in much greater numbers then is currently the case if the disapproval was more widespread. As such, there is a prominence to PSM in NI, especially in relation to the BBC, and yet vulnerabilities are also present. However, as is argued here, these are mitigated against by various factors;

As noted above, much of the criticism that the BBC in NI does generate is focused on a small section of its current affairs-based phone-in programmes. If BBC NI abandoned its current affairs-based phone-in programmes, it is perhaps inarguable that while a public sphere may remain that is closer to their personal preferences of those who oppose these programmes—it would nevertheless be a reduced public sphere. This can be seen at the most basic level in the fact that it would first and foremost have less news and information circulating within it. The BBC’s detractors rarely offer a vision of what the public sphere would be like with the absence of BBC NI’s more controversial programmes. Indeed, there is no reasonable prospect that commercially funded news broadcasters would replace anything like the same level of news and current affairs content within NI, currently broadcast by BBC NI. This has of course been extensively seen elsewhere in the UK, where stations like LBC and Times Radio now produce extensive news and current affairs programming in a commercial context, alongside leading podcasts like The News Agents and The Rest is Politics. Without programming like this provided by the BBC there might be less controversy, but there would also be fewer opportunities for the issues of the day to be debated on a widespread basis. Indeed, the Corporation will never have an understated role to play within politics and society in NI—the work of the Corporation simply is too bound up within the wider issues in NI’s public sphere to mean that it will ever exist quietly; and it will illicit passionate responses from across society for the foreseeable future. As we know from many decades of the BBC generating a very heated reaction in NI, primarily from its contested role during the Troubles (Savage Citation2022), this is an ever-present feature of the NI media system. With that come ever-present vulnerabilities, which—if critical voices grow louder—may begin to substantially erode the position of the BBC in NI. At this point of strife for the Corporation in NI, good governance and accountability is crucial;

A key component of the PSMs retaining their prominence, is based on their performance in certain key areas, discussed in this article: as such, the fact that the BBC’s first run spending and hours produced for NI audiences has not recovered to 2019 levels is concerning; while at UTV the high-water marks were 2017 (spending) and 2018 (hours), even if spending has been increasing in recent years. If arguments are to be sustained for PSM—in terms of its very raison d'être—then PSMs must ensure that audiences in a region like NI can continually see the value of such services. Of course, the BBC can point to the 111% spending in NI of what it receives in licence fee income, where NI is a net beneficiary—and yet such nuances will be lost on audiences if they feel underserved. As we have seen, while aspects of Channel 4’s performance in NI are strong, in the “originated content” category of spending Channel 4 underrepresents NI. And finally, in the made from NI category, NI PSM’s productions for network audiences have scope for expansion. Overall, while there is not yet vulnerability in this category, there is a sense in which decline across these measurements could lead to that situation.

Finally, on the potential for Irish reunification, there is some vulnerability regarding the uncertainty of how PSM would be constituted in the event of a referendum leading to constitutional change. As noted, there has been very limited scrutiny of the issues, and more questions remain than answers that are offered. Academics and policy makers looking at the situation, as has been commenced in Ramsey (Citation2023), need to start mapping out the areas in need of resolution, and start putting policy options on the table regarding things like funding: perhaps a new PSM in a reunified Ireland could pioneer a new type of funding, not yet seen in Ireland, such as household media funding. More learning from the Scottish and Welsh cases needs undertaken, with additional addressing of international case studies such as where PSM organisations have been substantially overhauled or merged required. The present policy lacuna leads to uncertainty, and thus vulnerability.

Many issues remain unresolved, and as a result vulnerabilities are inherent. And yet, the prominence of PSM means that it is at the centre of the public sphere in NI. Its future, whether within the UK, or in a reunified Ireland, will be central to the functioning of whatever media system remains.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Phil Ramsey

Phil Ramsey (corresponding author) is a Lecturer in the School of Communication and Media and a member of the Centre for Communication, Media and Cultural Studies, at Ulster University, UK.

Notes

1 This article specifically addresses PSM and wider broadcasting, but doesn’t place a focus on NI’s newspaper market.

2 Survey population and question: “Online adults/teens aged 13+, Northern Ireland. Question: Q1a. Can you tell us which of the following services you have personally used to watch programmes, films or other video content in the past 3 months?” (Ofcom Citation2023b, 16).

3 Calculation derived from ONS (Citation2022). Nations' Populations: NI—1.9 m; Scotland—5.5 m; Wales—3.1m: Total: 10.5 m.

4 The NI population of 1.9 m people as a proportion of the UK population of 67 m (ONS Citation2022).

5 Stephen Nolan also has a national presence on the BBC through his broadcasts on BBC Radio 5 Live.

6 Writing in The Sun, Noa Hoffman (Citation2023) called the television licence fee a “controversial fee,” where a government source was quoted as saying that “The licence fee model is becoming unsustainable.”

REFERENCES

- Atkinson, Paul, and Amanda Coffey. 2004. “Analysing Documentary Realities.” In In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice, edited by David Silverman, 56–75. London: SAGE.

- BBC. 2023a. “Our Story: The History of the BBC in Northern Ireland.” BBC. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/northernireland/heritage/our-story.

- BBC. 2023b. BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2022/23. BBC: London.

- BBC News. 2023a. “RTÉ ‘Will Be Insolvent by Spring’ Without Funding.” BBC News. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/clld9jz0pdmo.

- BBC News. 2023b. “Radio Foyle: Politicians and BBC Hold Talks About Cuts.” BBC News. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-64397271.

- Bell, Matthew. 2022. “How BBC's Sunday Morning Live Became a UK-Wide Production.” Royal Television Society. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://rts.org.uk/article/how-bbcs-sunday-morning-live-became-uk-wide-production.

- CAIN. 2023. “Quotations on the Topic of Discrimination.” CAIN. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/issues/discrimination/quotes.htm.

- Cairney, Paul. 2021. The Politics of Policy Analysis. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Channel 4. 2022. “Channel 4 and Northern Ireland Screen Join Forces to Boost Nation’s Broadcast Industry”. Channel 4. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.channel4.com/press/news/channel-4-and-northern-ireland-screen-join-forces-boost-nations-broadcast-industry.

- Channel 4. 2023. “Channel Four Television Corporation Report and Financial Statements 2022.” Channel 4. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://assets-corporate.channel4.com/_flysystem/s3/2023-07/Channel%204%20Annual%20Report%202022%20-FINAL%20Accessible.pdf.

- Coleman, Maureen. 2021. “Stephen Nolan: To Suggest I Favour One Side Over the Other Is Ludicrous.” The Irish News, February 1, 2021.

- Community Relations Council. 2018. “Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report – Number Five.” Community Relations Council. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.community-relations.org.uk/files/communityrelations/media-files/NIPMR-5.pdf.

- Donders, Karen. 2021. Public Service Media in Europe: Law, Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Erwin, Alan. 2021. “BBC’s Stephen Nolan Receives Further Five-Figure Sum in Damages After Tracking Second Twitter Troll.” Belfast Telegraph, July 2, 2021.

- Garry, John, O’Leary Brendan, and James Pow. 2022. “Much More Than Meh: The 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly Elections.” LSE British Politics and Policy. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2022-northern-ireland-assembly-elections/.

- Graham, Seanín. 2023. “BBC Orders ‘Content’ Review of Stephen Nolan Radio Show in North Amidst Nationalist Boycott.” The Irish Times, July 5, 2023.

- Harding, Phil. 2015. “Public Service Media in Divided Societies: Relic or Renaissance?” Policy Briefing #15. BBC Media Action. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08996e5274a27b200015d/psb-in-divided-societies-sept-2015.pdf.

- Hardy, Jonathan. 2014. Critical Political Economy of the Media: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hayward, Katy, Milena Komarova, and Ben Rosher. 2022. “Political Attitudes in Northern Ireland After Brexit and Under the Protocol.” Access Research Knowledge. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.ark.ac.uk/ARK/sites/default/files/2022-05/update147_0.pdf.

- Herzog, Christian, Christian Handke, and Erik Hitters. 2019. “Thematic Analysis of Policy Data.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research, edited by Hilde Van den Bulck, Manuel Puppis, Karen Donders and Leo Van Audenhove, 385–401. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- HM Government. 2015. “Revised Memorandum of Understanding - BBC Charter Review/NI Executive.” Accessed August 30, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/520002/NI_MoU.pdf.

- HM Government. 2023. “Michael Smyth CBE KC (Hon) Appointed as Northern Ireland Member of the BBC Board.” HM Government. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/michael-smyth-cbe-kc-hon-appointed-as-northern-ireland-member-of-the-bbc-board.

- Hoffman, Noa. 2023. “Beeb Under Scrutiny: BBC Faces Formal Review Over ‘Unsustainable’ Licence Fee Model With Ministers Poised to Intervene.” The Sun, July 18, 2023.

- Ivory, Gareth. 2014. “The Provision of Irish Television in Northern Ireland: A Slow British–Irish Success Story.” Irish Political Studies 29 (1): 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2013.875894.

- Lafferty, Orla. 2014. “From Fun Factory to Current Affairs Machine: Coping with the Outbreak of the Troubles at Ulster Television 1968-70.” Irish Communication Review 14 (1): 48–64. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7T14H.

- McCallion, Karen. 2021. “What’s Next for Public Service Broadcasting in Northern Ireland?” Northern Ireland Assembly. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.assemblyresearchmatters.org/2021/06/21/whats-next-for-public-service-broadcasting-in-northern-ireland/.

- McLaughlin, Sophie. 2023. “Channel 4 Commissions Two New Series from Northern Ireland Production Companies.” Belfast Live. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/tv/channel-4-commissions-two-new-26174505.

- Nagle, John. 2022. “Northern Ireland: Still a Deeply Divided Society?” The Foreign Policy Centre. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://fpc.org.uk/northern-ireland-still-a-deeply-divided-society/.

- Ofcom. 2018. Media Nations: Northern Ireland 2018. London: Ofcom.

- Ofcom. 2019. “Updated Guidance: Regional Production and Regional Programme Definitions: Guidance for Public Service Broadcasters”. Ofcom. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/152155/annex-1-updated-guidance.pdf.

- Ofcom. 2022a. Media Nations: Northern Ireland. London: Ofcom.

- Ofcom. 2022b. “Made Outside London Programme Titles Register 2022”. Ofcom. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/265541/Made-Outside-London-Register-2022.pdf.

- Ofcom. 2023a. Media Nations. London: Ofcom.

- Ofcom. 2023b. Media Nations: Northern Ireland. London: Ofcom.

- Ofcom Advisory Committee for Northern Ireland. n.d. “Submission to Ofcom Small Screen: Big Debate Consultation on the Future of Public Service Broadcasting”. Ofcom. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/218036/Ofcoms-Advisory-Committee-for-Northern-Ireland.pdf.

- Ofcom. n.d. “Glossary.” Ofcom. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/130719/Glossary.pdf.

- ONS. 2022. “Population Estimates for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid-2021.” ONS. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2021.

- Paramount. 2023. “Business Affairs: Useful Documents.” Paramount. Accessed August 17, 2023 https://www.viacomcbs-mediahub.co.uk/corporate/channel-5-programme-production/business-affairs.

- Picard, Robert G. 2020. Media and Communications Policy Making: Processes, Dynamics and International Variations. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Puppis, Manuel. 2009. “Media Regulation in Small States.” International Communication Gazette 71 (1-2): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048508097927.

- Ramsey, Phil. 2015. “Broadcasting to Reflect ‘Life and Culture as We Know It’: Media Policy, Devolution, and the Case of Northern Ireland.” Media, Culture & Society 37 (8): 1193–1209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715591674.

- Ramsey, Phil. 2016. “BBC Radio Ulster: Public Service Radio in Northern Ireland’s Divided Society.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 223(1): 144–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529.2016.1155027.

- Ramsey, Phil. 2017. “BBC Radio and Public Value: The Governance of Public Service Radio in the UK.” Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio 15(1): 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.15.1.89_1.

- Ramsey, Phil. 2023. “Public Service Broadcasting in Northern Ireland: Research Monitoring Report – 2023.” Belfast: Ulster University. Accessed April 9, 20234. https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/128036793/Ramsey-PSB-Report-2023-Final.pdf.

- Ramsey, Phil, and Philip McDermott. 2020. “Local Public Service Media in Northern Ireland: The Merit Goods Argument.” In In Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by Agnes Gulyas and David Baines, 448–456. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Reilly, Paul. 2021. Digital Contention in a Divided Society: Social Media, Parades and Protests in Northern Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Rice, Charis, and Maureen Taylor. 2020. “‘Reconciliation isn’t Sexy’: Perceptions of News Media in Post-Conflict Northern Ireland.” Journalism Studies 21 (6): 820–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1724183.

- Rice, Charis and, Maureen Taylor. 2023. “Trust in Media: Relevance, Responsibility, and Epistemic Needs in Divided Societies.” In Responsible Journalism in Conflicted Societies: Trust and Public Service Across New and Old Divides, edited by Jake Lynch and Charis Rice, 141–155. Abingdon: Routledge.

- RTÉ. 2023. “Frequently Asked Questions.” RTÉ. Accessed September 5, 2023. https://www.rte.ie/player/en_IE/profile/faq.

- Savage, Robert J. 2022. Northern Ireland, the BBC, and Censorship in Thatcher's Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scottish Government. 2013. Scotland’s Future: Your Guide to an Independent Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Seaton, Jean. 2017. Pinkoes and Traitors: The BBC and The Nation, 1974–1987. London: Profile Books.