ABSTRACT

This study explores how health-tech small and mid-size enterprises (SMEs) could better utilize the entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) around them in developing their business within this fast-growing yet under-researched industry. Based on the qualitative empirical study, we examine actor roles and related dynamics in the health-tech ecosystem to understand how firms could benefit from the ecosystem's resources. The study contributes to EE research by providing an empirically grounded typology of ten actor roles and examining how an individual company could change and develop its role in the network to grow and succeed. Moreover, it extends the current research on role typologies by explaining the various roles in EEs and underlines the importance of ecosystem dynamics. Managerially, the study highlights the importance of recognizing the company’s role(s) and the roles of other ecosystem members, which further aids in their strategic decision-making and future planning.

Introduction

Health technology is in many ways an important and rapidly developing business field, providing various new business opportunities for firms, especially for high growth SMEs, and creating significant health-related innovations and cash flows for society and the economy. To understand and enhance the growth and success of the companies involved, paying attention to the business environment becomes crucial. Here, the concept of the EE comes forward.

Entrepreneurial ecosystems have recently attracted a lot of research interest (Stam, Citation2015; Stam & Spigel, Citation2017). A seminal study by Stam (Citation2015) defines EEs broadly as ‘a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship' (p. 1765). Closely related to this, the recent study of Van Rijnsoever (Citation2020, p. 2) defines an EE as ‘a set of actors that interact and exchange resources in a network under an institutional regime and an infrastructure'. Hence, looking through the lenses of EEs, the concepts of entrepreneurship, network, interaction, and the exchange of resources can be used as a starting point to examine health-tech SMEs. Furthermore, high-growth businesses with innovative R&D are at the heart of an EE discourse (Bosma & Stam, Citation2012). EEs are also often industry-specific (e.g. the pharmaceutical cluster in Copenhagen and the mobile cluster in North Jutland) and emerge in locations that have place-specific assets (Mason & Brown, Citation2014). Thus, the EE approach provides a fruitful approach to study the development of health-tech SMEs.

Although EE research has been increasing significantly, there is still a limited theoretical, empirical, and conceptual understanding of the related phenomena (Colombo et al., Citation2019). Previous studies have focused on, for example, defining the EE concept (Isenberg, Citation2010; Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Stam, Citation2015), examining the roots of EEs in terms of their antecedents in the literature (Acs et al., Citation2017), developing a process perspective on EEs (Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018) and studying the governance structure of EEs (Colombo et al., Citation2019). The existing studies have concentrated mainly on macro-level aspects (Cunningham et al., Citation2019) such as environmental factors (Suresh & Ramraj, Citation2012) various social, cultural, and material attributes of EEs (Spigel, Citation2017), and environmental sustainability (Cohen, Citation2006), leaving micro-level perspectives related to, for example, interactions of various EE actors, with less attention. In addition, as the study of Tabas et al. (Citation2020) argues, there is a need for more empirical research on EEs.

To narrow down this apparent research gap, this study explores how the health-tech SMEs could better utilize the EEs around them in developing their business and what these SMEs do to facilitate collaboration in the ecosystem. More specifically, we focus on defining a typology of roles actors take to benefit from the ecosystem's resources. This is closely related to EE dynamics, i.e. how an individual company could change and develop its role in the network to grow and succeed. Thus, the study aims to answer the following research questions: What are the main roles of SMEs in the EE? What kinds of dynamics in those roles can be identified in the EE?

As mentioned earlier, to understand the functioning and dynamics of the EE from the single firms’ business development perspective, there is a need for more micro-level investigation. For that purpose, the network approach (e.g. Håkansson & Ford, Citation2002) provides a concept of role that can be applied to understand the dynamics within business networks (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation1998; Knight & Harland, Citation2005). Hence, theoretically, this study uses EE research as a basis for exploration but utilizes network research as a complementary approach to enrich the current EE discussion by adding the concepts of role and position in the debate. We chose to use EE as the central concept of the study as the focus here is on the ecosystem in which the health-tech SMEs operate. However, we acknowledge that the concepts of (business) networks and (business) ecosystems, for instance, are somewhat similar and could in many cases be used interchangeably.

Our study contributes to EE research by providing an empirically grounded typology of the roles of SMEs in the health-tech ecosystem. The resulting typology identifies a total of ten roles that can be divided into broader categories of dominant, supporting, and passive roles. Identifying these roles enables a better understanding of the context the health-tech firms are embedded in, which in turn aids in managing their relationships and thus changing the roles towards the desired direction. Furthermore, we bring in a micro-level perspective that has mostly been lacking in the extant EE studies. Emphasizing the perspective of individual companies provides new insights into understanding the functioning of the EE. More specifically, it helps to understand how individual companies could better utilize the ecosystem around them. Here it is important to note that entrepreneurs in EEs use the resources available, whilst also participating in generating those resources; relating, sharing and providing resources for other members in the EE. Thus, they can simultaneously play several roles as they interact with other actors in the ecosystem. Managers can use the findings as a guiding tool when deciding what role to position around and when analyzing the whole ecosystem.

The empirical context of the study is an ecosystem built around health technology in the Oulu region, a fast-developing technology district located in Northern Finland. In this study, we first, based on the literature review, develop a loose theoretical framework to build our qualitative empirical analysis. The data consists of 19 interviews with the managers of health-tech SMEs, including Medtech and Health services, from the same health-tech ecosystem and other archival material. Based on the analysis, the typology of roles is presented and discussed in connection to the positions of the health-tech SMEs and identified network dynamics in the ecosystem. Finally, the conclusions section presents the theoretical contributions, managerial implications, limitations, and future research suggestions.

Theoretical background

The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems

The EE concept gained momentum through the pioneering studies of Cohen (Citation2006), Isenberg (Citation2010) and Feld (Citation2020). In an EE, the focus is on creating new business opportunities or new knowledge (Valkokari et al., Citation2017). The EE approach recognizes that entrepreneurship is fundamentally mediated by the local context (Brown & Mason, Citation2017) and that the context influences how entrepreneurship progresses in the marketplace (Ratten, Citation2020a). In addition, discussion around EE places emphasis on interactions (Ratten, Citation2020b).

To understand the functioning of the ecosystem, it is vital to know the organization's definition of its network role. This, in turn, shows how an organization interprets its position in each network and highlights its network behaviour (Abrahamsen et al., Citation2012). However, it is not only how the organization itself defines its role but also how other organizations see each other’s roles. Next, the essence of the role concept is discussed in connection to the closely interrelated concept of position.

Defining the concept of role and its relatedness to actor’s position

Role

The term ‘role’ emanates from theatre, meaning the part that an actor or actress played ( Biddle & Thomas, Citation1966). The concept of role has long been featured in the research on relationships and inter-organizational networks (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation1998; Knight & Harland, Citation2005; Montgomery, Citation1998). These studies apply that concept to make meaning out of dynamics within business networks (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation1998; Knight & Harland, Citation2005). For example, Anderson et al. (Citation1998) define role ‘as a concept for describing the intentions of a business actor, construction of the meanings in their situations and construction of their preferences of changing it by acting in a role'. Nyström et al. (Citation2014, p. 484) see role as the ‘behaviours expected of parties in particular positions'.

Role influences SME’s activities in the ecosystem in many ways. First, it is a means to claim, bargain for, and gain membership and acceptance in a social community (Winship & Mandel, Citation1983). Second, it grants access to social, cultural, and material capital that actors exploit to pursue their interests (Baker & Faulkner, Citation1991). Finally, it is also essential to note that actors may play different roles in the various ecosystems they belong to (Iansiti & Levien, Citation2004).

Several studies have identified different roles for actors in other contexts. A seminal study by Mintzberg (Citation1980) categorized managerial work in ten roles in three groups: 1) interpersonal roles of figurehead, leader, and liaison, 2) informational roles of monitor, disseminator, and spokesman, and 3) decisional roles of entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator and negotiator. In their study on managerial action-based roles for managing in business nets, Heikkinen et al. (Citation2007) found ten different roles for managers in total. In contrast, Nyström et al. (Citation2014) suggested 17 role-related tasks for actors in a living lab. More recently, Dedehayir et al. (Citation2018) have highlighted various roles seminal to innovation ecosystem birth. Coming close to the context of our study, the discussion of EEs emphasizes the essential roles of mentors (Lafuente et al., Citation2007; Ozgen & Baron, Citation2007) and dealmakers (Feldman & Zoller, Citation2012). Iansiti and Levien (Citation2004) identify three (business) ecosystem strategies/roles that a firm can choose: keystone, dominator, or niche.

Thus, there is quite a large variety of identified roles in different contexts. Yet, there seems to be a gap in the current understanding of what kinds of roles SMEs operating in EEs can have and how they relate to the positions those firms have in the EE. Enhancing this understanding can further identify the roles and related positions, aiding the SMEs to better utilize the EE to reach their business goals. For that purpose, the concept of position and the interrelated nature of role and position is elaborated on next.

Position

SMEs’ in EEs are strongly linked with the actors’ positions within the network structure, central or peripheral. Therefore, the role is closely related to firms’ positions in particular EEs. As mentioned, roles are a collection of behaviours expected from an actor with a specific position (Nyström et al., Citation2014), determining the capacity and result of behaviour in a given structure (Heikkinen et al., Citation2007). The position is, thus, based on the different types of resources the actor owns; if resources are valuable to the ecosystem, the position is stronger and vice versa. Furthermore, actors’ positions determine the roles in which they can act. Therefore, actors’ perceptions of their roles must be seen in relation to their position interpretations.

Relationships are also seen as valuable resources strengthening actors’ position. Turnbull et al. (Citation1996, p. 12) see network position as ‘ … a description of a company's portfolio of relationships and the rights and obligations that go with it. Thus, network position is both an outcome of past relationship strategy and a resource for future strategy'. Traditionally, a company's position in a business network has been described in terms of its location in the marketing channel, but in a network context, it connotes an actor's connection to others in a network of actors (Easton, Citation1992; Turnbull et al., Citation1996). Thus, a company’s network position is a sum of all its relationships (Abrahamsen et al., Citation2012) and other resources such as IPRs and technological skills.

An actor’s position is a matter of intentions and interpretations of the actors in a network (Johanson & Mattsson, Citation1992), which implies different interpretations of this position (Gadde et al., Citation2003). Therefore, understanding one actor's position may conflict with the other actors’ interpretations (Abrahamsen et al., Citation2012). The same applies to the roles; they are dependent on the interpretations and actors making these interpretations.

Network positions generally are concerned with expected activities that come with a network position, such as keeping your existing suppliers, maintaining your wholesaler functions or being the market leader (Anderson et al., Citation1998). According to Gulati (Citation1998), the most valuable network asset could be traced to a firm's position with a network structure. A firm with a robust network position can quickly identify and explore knowledge resources within its network (Tsai, Citation2001; Zaheer & Bell, Citation2005) for innovation and better performance (Ahuja, Citation2000; Wang et al., Citation2018).

Network dynamics

Networks are dynamic entities because ‘actors are constantly looking for opportunities to improve their position in relation to important counterparts and are therefore looking for opportunities to create changes in the relationships’ (Håkansson & Snehota, Citation1995, p. 275). This notion of network dynamics and change processes leads us further to consider how identifying the roles can aid in understanding these dynamics. Managerially, it connects the role concept to the strategic decision making of the companies by offering a means to change the role and related position towards the desired direction and better utilizing the opportunities provided by the EE.

There have been many studies applying the concept of role to understand the dynamics within business networks (e.g. Anderson et al.,Citation1998; Knight & Harland, Citation2005). To understand network changes, it is vital to note that a company has a position but acts in a role, which implies that it must consider how an actor interprets its role and position and decides to enact them (Anderson et al., Citation1998). Thus, it is crucial to know the organization's definition of its network role, as this will show how an organization interprets its position in a given network (Abrahamsen et al., Citation2012). As further suggested by Abrahamsen et al. (Citation2012), network dynamics may be understood in terms of actors seeking to change their network position. Therefore, their networking behaviour must be seen in relation to the actors’ roles in that process. Actors’ role conceptualizations in themselves impact network change, as actors try to shape and align role interpretations to create changes in their network. However, their ability to change their positions depends on a shared understanding of roles between the actors in the network; it is how the organization comprehends itself and how collaborating actors interpret the situation.

To sum up the above discussion, it can be concluded that the role and position are highly interrelated concepts influencing each other. As Anderson et al. (Citation1998) put it, ‘there are no positions without roles and no roles without positions'. In addition, they are both always subjectively interpreted, context-dependent, and connected to the actors’ intentions, which implies that they are also related to the strategic decision making of the company. Finally, and very importantly, both the role and position are highly dynamic concepts. This dynamism enables us to explore the changes needed to be able to reach the actors’ future business goal. The following part, we will empirically explore the roles of the health-tech SMEs within their EE as well as the related positions and dynamics taking place in the EE. However, before the empirical study, the methodological issues of the study are shortly described.

Methodology

This paper is conducted as a qualitative exploratory study (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008). Qualitative methods help describe, understand, and explain the human interactions, meanings, and processes creating real-life organizational settings (Gephart, Citation2004), which is the focus of this study. To answer the research questions, we use the inductive approach. The inductive approach provides an easily used and systematic set of procedures for analyzing qualitative data to produce reliable and valid findings (Thomas, Citation2006).

The health-tech ecosystem explored in this study is a combination of stakeholders across academia, private and public sectors such as firms, universities, public sector agencies, financial bodies, researchers, university hospitals, and entrepreneurs. health-tech is a part of the larger health sector, including for example pharmaceuticals, the public health care and social services system and private health care services. The health-tech industry uses the latest technology such as the internet of things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and services associated with clinical research and regulations. Based on the Health-tech Finland (Citation2019) report, health-tech is the largest high tech export segment, with an estimated export of 2.3 billion euros in 2019 and over 13,000 employees in Finland. In order to ensure as versatile and comprehensive data as possible, we choose firms from health-tech that are in different stages of their growth; some of the companies have become the established high growth firms, some of them are in the middle stage, while few companies are in the starting stage, recently receiving medical certificate approval (e.g. the European Conformity (CE) mark and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval). However, the common denominator was their ambitions to grow and develop their business.

Data collection

The data was collected through semi-structured interviews, allowing some improvisation and thus providing important insights that may arise during the interview (Myers, Citation2013). Primary data consists of 19 semi-structured interviews with the CEOs, Chief Executive Officers, Marketing Directors, Executive Vice Presidents, Vice Presidents, Sales and Marketing Managers, and Managing Directors of SMEs members of the same local health-tech ecosystem in Northern Finland. We deliberately interviewed the top management as they could provide the best information regarding all the aspects of the company.

Interviews were conducted during September-December in 2019. They were audio-recorded and lasted between 47-100 min. Interviews were transcribed word-for-word and generated over 200 pages of manuscripts. In addition to interviews, which form the primary data for this study, we have also used secondary data (e.g. internal documents, information from the websites, and press releases) providing a general understanding of the health tech business and companies’ operations within it. Therefore, the secondary data was not directly utilized in the analysis, but it has supported the researchers’ understanding of the research phenomenon on a general level. presents the profile of the interviewees and data collection.

Table 1. List of interviews.

Data analysis

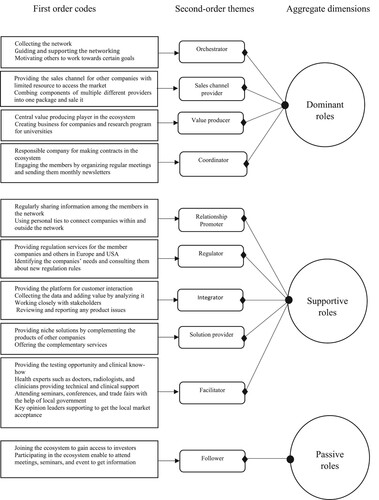

The data were analyzed by using the Gioia method. It is built on a constructivist approach and develops new concepts (Gioia et al., Citation2013). The approach relies on the notion of knowledgeable actors who actively construct their reality and can explain their thoughts, intentions, and actions (Gioia et al., Citation2013). First, the authors read each interview and listed all terms, categories, and codes related to the actor roles. Next, the similarities and differences among the categories were identified, leading to the generation of first-order codes. Then, based on the first-order codes, we developed the second-order themes. Finally, we further investigated the similarities and differences of the second-order themes to draw out the aggregate dimensions. The data structure related to actor roles is illustrated in . In addition, actors’ positions and dynamism in roles were further analyzed based on the roles.

Findings

The empirical data shows that the companies play different roles in the health-tech ecosystem and these roles are closely connected to the positions companies hold. The roles may be based on overlapping positions and there are lots of dynamics involved due to changing roles and positions of the actors involved in the EE. We found that companies can simultaneously play several roles and those roles can be classified under three main categories: dominant, active, and passive (see aggregate dimensions in ). Various, more specific roles were identified (i.e. second-order themes) based on the first-order codes described in more detail. More precisely, first-order codes depict the main activities of the companies involved in EE and based on those, the roles were recognized and named as ‘orchestrator’, ‘sales channel provider’, ‘producer’, ‘integrator’, ‘coordinator’, ‘relationship promoter’, ‘regulator’, ‘data collector’, ‘solution provider’, ‘facilitator’ and ‘follower’. The roles, however, are not entirely exclusive. Although having different core meanings, some of them can be closely connected. Next, these roles are further elaborated with the help of quotations from the interviews. After that the positions behind these roles are discussed, followed by analysis of general dynamics of changing positions and roles.

The roles of the SMEs in the health-tech ecosystem

Dominant roles

Companies in dominating roles have a significant influence on other EE member companies. These firms can, for example, provide resources (e.g. industry know-how, funding, employees), connect other companies to the markets, share information about the production processes, and give a sort of platform for other members facing resource constraints to accessing to market. Dominant firms are primarily established companies and have already achieved a high growth rate and international sales. Therefore, we classified them as orchestrator, sales channel provider, value producer connector, and contractor.

Orchestrator

A network orchestrator coordinates and empowers the ecosystem companies and motivates them to act entrepreneurially. The orchestrator plays a leadership role in pulling together the dispersed resources and capabilities of ecosystem members. Furthermore, the orchestrator tries to establish trust in the network to enhance collaboration, supporting its functioning. Our findings also suggest that the network orchestrator often establishes a big network to get more customers and market share. This is how one of the orchestrator firms describes its role in the ecosystem:

‘We are the starter; we are the ones who collected the network. We are the orchestra leader; I think in the ecosystem together, we can be stronger. For example, I need to have a network behind me to target huge customers.' (Omicron).

Sales channel provider

Due to their small size and limited resources, SMEs are often confronted with the liability of newness (Hymer, Citation1976) and foreignness (Zaheer, Citation1995). To overcome these challenges, many companies see it highly important to be a member of the health-tech ecosystem to access resources, knowledge, know-how, and market. According to our data, the companies in the EE can play a sales channel provider role in the sense that they are helping other member companies access customers and markets. This is one of the critical roles companies play in the EE since it influences the viability of the whole EE. The following quotation reveals how the company adopting a sales channel provider role acts as a link between other companies.

‘We are connecting companies that do not have access to the end customers and the market. Then we act as the link in between. We are a kind of pathway for commercialization to the other companies in the ecosystem.' (Xi)

Value producer

In the health-tech ecosystem, few established companies can be identified as value producers. However, these companies have a lot of resources and thus, they can influence other EE players. They can, for instance, create business for other companies or be the starter for research programmes for universities. Based on our data, the value producer role can be described as follows:

‘We are the one who manufactures the product that helps to take care of the patients. So, for example, we have research partners in the network who give ideas for manufacturing and creating those tools—the vendors we can then add to our solution. So, I would say that we are a kind of central value-producing player in the ecosystem.' (Tau)

Coordinator

Norms and rules facilitate the efficient functioning of the network. Our data indicate that some of the hub firms can act in a coordinator role and set the rules and regulations for other member firms in business contracts, which lead the members to commit to certain obligations. The importance of contracts and formal roles in the network was highlighted in one of the interviews as follows:

‘In the Finnish network, we are the company responsible for making the contracts. The network is not a kind of illusion network where everybody comes and goes as they please. We need to have actual business contracts.' (Epsilon).

Supportive roles

According to our data, some companies play a supportive role in helping and assisting other companies (usually the smaller ones) by providing them e.g. information about the market, financial help and know-how. We classify these companies as supporting relationship promoters, regulators, integrators, solution providers, and facilitators.

Relationship promoter

The relationship promoter has a strong network and hierarchical power to drive a project, provide resources, and help others overcome obstacles (e.g. by regularly sharing information). Here, personal relationships and network assets are as important as personal know-how.

‘I regularly share information about my activities with the network. If I see someone in my network who needs help, I try to give support. I have many years of experience in the health business, and I know many different stakeholders. I use my links because I want to help.' (Kappa)

Regulator

The health sector is a highly regulated business area and almost all companies require different licences and permits to operate. Regulation requirements also vary across other countries. A company playing the regulator role provides regulatory services for the ecosystem members and actively consults them about new regulations. In the words of one of these companies’ representatives:

‘We have a pretty important role in the ecosystem since we have regulatory topics. Most companies need to get the medical device regulatory approval, such as European Conformity Mark (CE) and Mark Food and Drug Administration (FDA). We help them with this.' (Theta)

Integrator

The integrator provides the platform for interaction for other firms and with customers as well. Integrators can also collect, maintain, share data, and evaluate product/service usability by getting detailed customer information. As a result, the product or service can be improved.

‘I would say that we indeed see ourselves as providing the platform for customer interaction. For example, we have the interface, and, in this case, the nurse would be the user. Also, the others in the ecosystem could be integrated into our platform.' (Beta)

Solution provider

Companies playing a solution provider role are often highly innovative and complement other companies’ offerings in the ecosystem. They can work as customers and as sellers for the international players or combine components from multiple providers into one package.

‘We are providing niche solutions which, we believe, can complement the product portfolios of others. Our message for them is that we have something that is not competing with their existing portfolio but rather we complement their portfolio and bring value for their customers.' (Sigma)

Facilitator

The facilitator role was identified as one of the key supportive roles in the EE. The facilitator and the orchestrator roles have some similarities, but whereas the orchestrator is responsible for directing the whole network towards the goal, the facilitator supports a specific group of companies. The facilitator role can be multifaceted and involve various aspects. We identified three actors who act as facilitators: health sector experts, university hospitals and local government. Health sector experts can provide, on the one hand, testing opportunities and clinical know-how to the members of the ecosystem and, on the other hand, they can act as a key opinion leader to facilitate the company to sell their solutions and products to the market. In our sample, doctors and clinicians work in close collaboration with companies in their various phases of product development, so they act as both co-developers and users. In addition, references and acceptance from doctors and university hospitals are crucial.

‘The critical element is to get references […] through that, and we will get names and acceptance. If the big-name says it is okay to use our product anywhere, it will be good for us. Thus, we need the name to be able to be recognized.’ (Mu).

‘The university hospital provides the testing opportunity for our small company […] If you have some idea about the product and you created some sort of prototype, you could buy time from a hospital expert and test it in a test lab.' (Pi).

‘MedTech start-ups are very time consuming and money consuming. Maybe also the ecosystem should be more selective of who they support. To concentrate on those that have the potential to become internationally successful.' (Zeta).

Passive roles

The third main category of roles was identified as passive members of the health-tech ecosystem. Typical of these companies was their passive attitude towards operating in the network, simply following what was going on in the ecosystem around them without active participation. Based on the data we named this passive role as a follower.

Follower

Not all firms explored in this study found the ecosystem very important for them. These companies did not identify any close collaboration between other ecosystem members, but they still indicated their willingness to be a member of the ecosystem. Reasons for this were things like getting access to investors through the ecosystem or attending meetings, seminars, and events to get helpful information.

‘We try to make the best use of the ecosystem by participating in the seminars and events and gaining access to external stakeholder resources such as an investor.' (Iota)

The positions behind the roles in the EE

Based on their role in the ecosystem, each company has a distinctive position. First, we found that companies playing dominant roles such as orchestrator, sales channel provider or value producer usually have a central position in the ecosystem and provide valuable resources for other EE members. Operating in such a leading position, they typically gather and connect the network members, lead its operations, provide advice and empowerment to other ecosystem members, and help them to access new markets.

Secondly, apart from the central players, we identified other companies with an intermediate position in the ecosystem. For example, they can provide the ecosystem members with resources such as information, services, or networks. In addition, these companies typically play supportive roles, e.g. relationship promoter, integrator, or facilitator. In practice, this means, for instance, connecting companies to customers, gathering and analyzing data from the markets and customers, sharing some of the best practices with other ecosystem partners and providing regulatory support to others.

Finally, some companies have a kind of bystander position on the fringe of the health-tech ecosystem. These companies are not actively involved in the ecosystem and they have adopted a simple follower role. This means that they are hanging around the ecosystem to get information, access external stakeholders such as investors, and participate in events, seminars, and conferences.

Network dynamics in the health-tech ecosystem

As the final aspect, network dynamics became evident in our empirical analysis. The health-tech ecosystem is not stable or static, but it takes new forms as new actors come in and some existing actors leave the business. However, and even more importantly, dynamics are due to changing roles and positions of the actors involved in the EE. These changes can be intentional or unintentional. For some companies, the dynamics of the ecosystem around them happen despite their actions or intentions. Their role may change due to unexpected and indirect changes in the network relationships around them. For example, if other companies form a joint venture together, it may strongly influence the single company’s situation without its actions.

On the other hand, companies may be very determined to change their role and have a clear idea of how to develop their business in the future. Many companies stated that they see their role to be bigger and the position to be more central in the forthcoming years as they aim to grow their business. Although not all the companies explicitly expressed their willingness to grow or change their role/position, it became clear from the data that most of them aimed at developing their current role. For example, the company acting in a supportive role as a relationship promoter may want to change its role to a more dominant one in the future. Then, in some cases, dominant players reduce their involvement in the local ecosystem as it does not provide them enough resources and business opportunities, and they become more interested in the other national and international ecosystems instead. This is demonstrated in the following quotation:

‘Maybe in five years, when we are growing, then we could be a significant international player. But at this point, we have all the ingredients to be in the role that we have, as we are working as a customer and as a seller for the international players.' (Eta)

‘We have a central role and kind of manage different partners in the network. We formed that network because those other companies are connected through us. The network is continuously expanding.' (XI)

‘We are building our product here and then you start thinking, ‘Okay, I must go out, because if you create a health-tech product in Finland, you should be targeting the international markets. So, you can find some help here [in the current EE], but you will also need a network somewhere else.' (Mu)

Conclusions

This study explored how the health-tech SMEs could better utilize the EE in developing their business by identifying actor roles and related dynamics in the health-tech ecosystem. More specifically, we defined a typology of roles actors take to benefit from the ecosystem’s resources and facilitate operations within, and examined how an individual company could change and develop its role in the network to grow and succeed.

To answer the first research question, our typology identified ten actor roles that were further classified into three broader categories. First, dominant roles include ‘orchestrator’, ‘sales channel provider’, ‘producer’, ‘integrator’, and ‘coordinator’. Secondly, ‘relationship promoter’, ‘regulator’, ‘data collector’, ‘solution provider’, and ‘facilitator’ emerged as the supportive roles. Thirdly, few companies in their initial growth stage played a passive ‘follower’ role in the ecosystem. This typology aids in understanding the context the heath tech SMEs are embedded in, which in turn is important for managers to be able to analyze the surrounding ecosystem in-depth and consequently to develop the company’s current role in it. As an answer to the second research question, we found that changes in the role and related position cause EE dynamics, both intentional and unintentional. In the preferable situation, a company has clear visions and plans to develop its current role and position, typically meaning change from supportive towards a more dominant role. This proactive and determined stance means that the company can change its role and thus develop its business in a desirable direction. However, in some cases, the changes come from ‘outside', and individual firms have fewer chances to influence the development of their roles. Overall, our findings underline that network dynamics are the primary means for health-tech SMEs to change their role in the EE if they wish to develop and grow their business.

Theoretical contributions

Theoretically, this study contributes to the current literature on EEs that is primarily conceptual (Tabas et al., Citation2020). Generally, it concentrates on the macro-level aspects (Cunningham et al., Citation2019) with limited empirical research on the micro-level. This study takes on this issue and explores the role and position of companies based on the resources they possess in the health-tech ecosystem. This empirical study conducted in a timely and under-researched context of health-tech ecosystems thus provides new insights to EE literature by explaining how the health-tech SMEs could better utilize the EE around them in developing and growing their business.

Our findings also extend the current research on role typologies (Heikkinen et al., Citation2007; Nyström et al., Citation2014; Valkokari et al., Citation2017) by explaining the various types of roles in an EE in the context of health technology. By examining the actor roles in the ecosystem, we found that the company's position is dynamic and changes over time. This dynamism is the key to developing the health-tech SMEs’ future business, for example, towards a more dominant role in the current EE or other national or international ecosystems. Furthermore, our findings suggest that companies can play different roles at the same time. Thus, we share the view of Heikkinen et al. (Citation2007), according to which roles are dynamic and change rapidly over time.

Managerial implications

For the managers of health-tech SMEs, this study provides several implications. First, our study highlights the need for managers to profile their own company’s role and related position in the ecosystem around them. The typology of ten actor roles aids managers in analyzing their role and analyzing the ecosystem, which in turn helps in better utilizing the resources provided by the ecosystem. Moreover, the suggested role typology enables the companies to better understand the capabilities required for any specific role, which could prevent them from enacting roles they cannot master. Furthermore, recognizing the role(s) the company itself plays and the roles of other ecosystem members helps in strategic decision-making and planning the future, such as changing the role towards the desired direction. Our findings thus underline the importance of ecosystem dynamics; the managers need to remember that the roles are dynamic, and this change is the key in developing the company’s business.

Finally, our findings are important for policymakers who strive to boost the regional entrepreneurial ecosystems. For example, in targeting initiatives such as Startup Europe (SE) the key task is to create a strategy where start-ups as ecosystem actors are central. This study can contribute to understanding of the roles relevant in these ecosystems, likewise actor positions and dynamics influencing collaboration within entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Limitations and further research

Finally, this study has some limitations that may inspire future research. First, our findings are based on a study of the local health-tech ecosystem that may restrict the generalizability of the study. Therefore, future research could focus on other industries to enrich and confirm our insights. Second, we adopted a cross-sectional perspective to study the dynamic nature of actor roles in the ecosystem. However, since the roles in the EE are evolving, related dynamics could be studied over time through other methods in longitudinal studies. Finally, a related issue that requires attention in forthcoming studies is the ability of an ecosystem’s members to address the challenges of changing their role within the ecosystem and how other ecosystem members might react to these changes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahamsen, M. H., Henneberg, S. C., & Naudé, P. (2012). Using actors’ perceptions of network roles and positions to understand network dynamics. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.01.008

- Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8

- Ahuja, G. (2000). Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: A longitudinal study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(3), 425–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667105

- Anderson, H., Havila, V., Andersen, P., & Halinen, A. (1998). Position and role-conceptualizing dynamics in business networks. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 14(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00037-7

- Baker, W. E., & Faulkner, R. R. (1991). Role as resource in the hollywood film industry. American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 279–309. https://doi.org/10.1086/229780

- Biddle, B. J., & Thomas, E. J. (1966). Role theory: Concepts and research. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Bosma, N., & Stam, E. (2012). Local policies for high-employment growth enterprises. Report prepared for the OECD/DBA International Workshop on ‘‘High-growth firms: local policies and local determinants’’.

- Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9865-7

- Cohen, B. (2006). Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.428

- Colombo, M. G., Dagnino, G. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Salmador, M. (2019). The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9952-9

- Cunningham, J. A., Menter, M., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem governance: A principal investigator-centered governance framework. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9959-2

- Dedehayir, O., Mäkinen, S. J., & Ortt, J. R. (2018). Roles during innovation ecosystem genesis: A literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.028

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). The landscape of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage Publication.

- Easton, G. (1992). Industrial networks: A review. In B. Axelsson, & G. Easton (Eds.), Industrial networks: A new view of reality (pp. 3–27). Routledge.

- Feld, B. (2020). Startup communities: Building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. John Wiley & Sons.

- Feldman, M. P., & Zoller, T. D. (2012). Dealmakers in place: Social capital connections in regional entrepreneurial economies. Regional Studies, 46(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.607808

- Gadde, L. E., Huemer, L., & Håkansson, H. (2003). Strategizing in industrial networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(5), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(03)00009-9

- Gephart, R. P. (2004). Qualitative research and the academy of management journal. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<293::AID-SMJ982>3.0.CO;2-M

- Håkansson, H., & Ford, D. (2002). How should companies interact in business networks? Journal of Business Research, 55(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00148-X

- Håkansson, H., & Snehota, I. (1995). Developing relationships in business networks. Routledge.

- Health Tech Finland. (2019). Health Tech Finland. Retrieved 2020 from http://healthtech.citrus.dev/en/healthtech-industry-finland.

- Heikkinen, M. T., Mainela, T., Still, J., & Tähtinen, J. (2007). Roles for managing in mobile service development nets. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(7), 909–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.05.014

- Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms. MIT Press.

- Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage: What the New dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard Business School Press.

- Isenberg, D. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 41–49.

- Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. G. (1992). Network position and strategic action — An analytical framework. In B. Axelsson, & G. Easton (Eds.), Industrial networks: A new view of reality (pp. 205–2017). London: Routledge.

- Knight, L., & Harland, C. (2005). Managing supply networks:. European Management Journal, 23(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2005.04.006

- Lafuente, E., Vaillant, Y., & Rialp, J. (2007). Regional differences in the influence of role models: Comparing the entrepreneurial process of rural catalonia. Regional Studies, 41(6), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120247

- Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth-oriented entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD, Paris, 30(1), 77–102.

- Mintzberg, H. (1980). The nature of managerial work. Prentice-Hall.

- Montgomery, J. D. (1998). Toward a role-theoretic conception of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 104(1), 92–125. https://doi.org/10.1086/210003

- Myers, M. D. (2013). Qualitative Research in business and management (2nd ed). Sage.

- Nyström, A. G., Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., & Kortelainen, M. (2014). Actor roles and role patterns influencing innovation in living labs. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(3), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.12.016

- Ozgen, E., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.001

- Ratten, V. (2020a). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. Thunderbird International Business Review, 62(5), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22164

- Ratten, V. (2020b). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Future research trends. Thunderbird International Business Review, 62(5), 623–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22163

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

- Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1268

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. In R. Blackburn, D. De Clercq, J. Heinonen, & Z. Wang (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of small business and entrepreneurship (pp. 407–422). London: SAGE.

- Suresh, J., & Ramraj, R. (2012). Entrepreneurial ecosystem: Case study on the influence of environmental factors on entrepreneurial success. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(16), 95–102.

- Tabas, A. M., Komulainen, H., & Arslan, A. (2020). Internationalisation in entrepreneurial ecosystem and innovation system literatures: A systematic review. International Journal of Export Marketing, 3(4), 314–334. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEXPORTM.2020.109527

- Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

- Tsai, W. (2001). Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 996–1004. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069443

- Turnbull, P., Ford, D., & Cunningham, M. (1996). Interaction, relationships and networks in business markets: An evolving perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 11(3/4), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858629610125469

- Valkokari, K., Seppänen, M., Mäntylä, M., & Jylhä-Ollila, S. (2017). Orchestrating innovation ecosystems: A qualitative analysis of ecosystem positioning strategies. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(3), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1061

- Van Rijnsoever, F. J. (2020). Meeting, mating, and intermediating: How incubators can overcome weak network problems in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Research Policy, 49(1), 103884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103884

- Wang, M. C., Chen, P. C., & Fang, S. C. (2018). A critical view of knowledge networks and innovation performance: The mediation role of firms’ knowledge integration capability. Journal of Business Research, 88, 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.034

- Winship, C., & Mandel, M. (1983). Roles and positions: A critique and extension of the blockmodeling approach. Sociological Methodology, 14, 314–344. https://doi.org/10.2307/270911

- Zaheer, A., & Bell, G. G. (2005). Benefiting from network position: Firm capabilities, structural holes, and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 26(9), 809–825. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.482

- Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341-363. https://doi.org/10.5465/256683