ABSTRACT

Managers perform an important role at incubators by coordinating and managing operations while facilitating, and often delivering, services that support tenants’ business growth. Less is known about the relationship between managers and tenants at incubators, and how they support tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing. In this study, in-depth interviews with incubator managers (n = 28) and tenants (n = 12) were conducted to examine the role of managers in supporting tenant’s positive psychological wellbeing, focusing on the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The qualitative data provided consistent insights about the integral role of managers in supporting tenant’s positive psychological wellbeing, by facilitating their hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Managers are essential in supporting tenants at a critical point in their business development. Consideration is given to the role that incubator managers fulfil at incubators and the provision of support they offer tenants, to meet their business and psychological needs.

Introduction

Business incubators are contemporary facilities designed to encourage nascent business development within a supported and protective environment, fostering independence and self-sustainability in preparation for the wider business world (Aernoudt, Citation2004; Bliemel el., Citation2014; Robinson & Stubberud, Citation2014). Since they were first established in the USA in the 1950s, business incubators have flourished throughout the world.

An integral feature of the incubator model is the support offered to tenantFootnote1-businesses to assist their business development and growth from within a community that endorses an ‘entrepreneurial culture’ (Ayatse et al., Citation2017, p. 3; Redondo-Carretero & Camarero-Izquierdo, Citation2017). The role of managers at incubators is vital for operationalising these facilities, and in the provision and delivery of services to tenants and their businesses (e.g. Apa et al., Citation2017; Bruneel et al., Citation2012; Monsson & Jørgensen, Citation2016; Redondo & Camarero, Citation2017) to support and enable new business success (e.g. Lewis et al., Citation2011; Redondo & Camerero, Citation2017; Breivik-Meyer et al., Citation2020). Research evidence consistently attests to the importance of managers in creating incubator environments that generate trust (Vedel & Gabarret, Citation2014; Redondo-Carretero & Camarero-Izquierdo, Citation2017), that foster professional networks and collaborations within the incubator and external to it (Ahmad, Citation2014; Apa et al., Citation2017; Meyer et al., Citation2016; Tottenham & Sten, Citation2005), and deliver professional business support and advice to tenants (e.g. Monsson & Jørgensen, Citation2016), thus expanding tenants’ knowledge (Bruneel et al., Citation2012).

The established understanding of managers at incubators is associated with enabling new business success however, very little research has been conducted examining the relationship between incubator managers and incubator tenants and what influence their interactions and support may have on tenants’ psychological wellbeing.

The contribution of managers in supporting the psychological needs of tenants as they approach and grow their businesses has been largely overlooked in the published literature. This is despite the importance of psychological wellbeing and the constructs associated with it. These are constructs that lead to positive benefits that can enhance workplace and entrepreneurial activities and success (e.g. Baluku et al., Citation2016; Baluku et al., Citation2018; Friend et al., Citation2016).

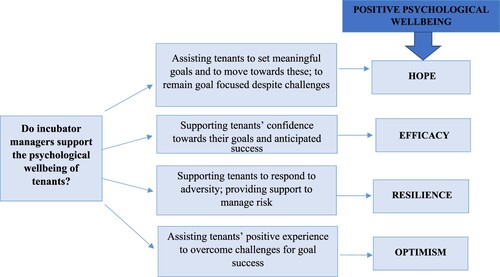

This research will investigate the relationship between managers and tenants at incubators through a positive psychology lens. It will examine the role of managers in supporting, and provisioning services that foster tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing. This will occur through an examination of the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism by collecting in-depth insights from the perspective of both incubator managers and tenants.

This research is unique in its approach. It is cross-disciplinary and applies qualitative research methods to extend the existing body of research about entrepreneurship and business incubators with an emphasis on the incubator manager-tenant relationship and the constructs associated with tenants’ positive psychology.

Positive psychology

Research on positive psychology informs the importance of, and mechanisms for developing positive psychological constructs that both protect and enhance an individual’s organizational attitudes and behaviours (Luthans et al., Citation2015). An empirical and conceptual exploration of positive behaviour within organizations identifies the importance of building hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism (Dawkins et al., Citation2013; Lorenz et al., Citation2016).

Together, and in synergy, hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism are the ‘building blocks’ for psychological capital; a higher-order construct in which positive, internal resources are leveraged toward success (Luthans et al., Citation2010; Luthans et al., Citation2004; Luthans et al., Citation2007) by directing and controlling an individual’s approach and pursuit towards goals, even when they experience inevitable challenges (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, Citation2017). Understanding the potential relationship between these constructs and tenants at incubators requires further exploration.

Hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism represent four important positive constructs that guide an individual’s current and future cognitions, emotions, and behaviours for positive gain and output. Each construct, which is derived from a strong theoretical foundation, offers many holistic benefits. Hope enables an individual to plan for, and direct a course of action to support goal achievement, while avoiding or addressing challenges or threats that prevent goal achievement (Luthans, Citation2002; Luthans et al., Citation2004; Snyder, Citation2000). Two reciprocal cognitive processes are associated with this construct: ‘pathways’ and ‘agency’ (Luthans & Jensen, Citation2002; Snyder et al., Citation2000). The former assists with planning and directing behaviours towards goals and redirecting pathways when challenges occur; the latter provides the impetus for individual to pursue their goals. Individuals with high levels of hope demonstrate direct and clear goals for achievement and can pivot to identify and implement new pathways for goal achievement (Snyder, Cheavens & Sympson, Citation1997) where barriers to goal achievement are perceived as potential challenges.

Efficacy guides cognitions, behaviours, and motivations, influencing and directing an individual towards successful outcomes (goals) and is synonymous with confidence and the commitment of one’s abilities to direct and action change, and control events (Bandura, Citation1993; Luthans et al., Citation2015). Efficacy assists with regulating motivation and guiding the processes and actions associated with anticipating proposed outcomes. It requires the individual to establish actions for guiding cognitive motivation (Bandura, Citation1993) and is influenced by successful past performance which informs experience and future expectations for success (Bandura, Citation1977).

Resilience enables an individual to positively adapt to adverse circumstances that optimize personal outcomes while utilising assets that can provide protection in response to adversity (Garcia-Dia et al., Citation2013; Masten, Citation2014). A range of internal and external factors protect against the stress or adversity being experienced. These factors include maturity, access to available resources, personality (Garcia-Dia et al., Citation2013; F. Luthans et al., Citation2015), while assets (such as relatives and friends) provide support in developing an individual’s resilience and cushioning adversity (Garcia-Dia et al., Citation2013). Being resilient facilitates positive outcomes, including personal growth and understanding, greater psychological control and strength or adjustment that can influence how an individual integrates into their environment and responds to adversity as a component of healthy functioning (Bonanno, Citation2004; Garcia-Dia et al., Citation2013).

Optimism represents the positive expectation for success that directs an individual’s behaviours towards their goals, despite inevitable challenges (Carver et al., Citation2010). Theoretically, optimism is associated with expectancy whereby the motivation for goal achievement, and the value attributed to the goal, propels behaviours (Carver et a., Citation2010). Expectancy is closely aligned with confidence for obtaining success, which in turn incites an individual towards their goals (Carver et al., Citation2010).

Published research offers compelling evidence for the positive influences of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Hope is associated with goal achievement (Friend et al., Citation2016) and positive workplace performance, commitment, and satisfaction (e.g. Reichard et al., Citation2013; Youssef & Luthans, Citation2007). Efficacy can support goal setting and job satisfaction (Luthans et al., Citation2015). Resilience is an important construct for employees in challenging, high-demand settings (Luthans et al., Citation2015; McGarry et al., Citation2013) while mitigating burnout (Mealer et al., Citation2012). Optimism is associated with elevated levels of motivation and hard work (Luthans, Citation2002), and persistence towards goals (Carver et al., Citation2010; Monzani et al., Citation2015).

Positive psychology and new businesses

Entrepreneurs and businesses face unique challenges when establishing new enterprises, including contextual and situational factors (Zahra et al., Citation2014). It is well documented that new business owners undergo intense and life-changing experiences that are often highly stressful (e.g. Shepherd et al., Citation2021). Researchers (e.g. Cooper et al., Citation2012) have proposed that the facilitation of tenants’ networking and social connections in the incubator may moderate tenant stress associated with establishing a new business. Networking for tenants, both within and external to the incubator, develops their expertise through exposure to business support and activities (e.g. Bergek & Norrman, Citation2008; Bøllingtoft, Citation2012; Hackett & Dilts, Citation2004; Peters, Rice, & Sundararajan, Citation2004). Networking within these settings also creates social capital (Scillitoe & Chakrabarti, Citation2005). Incubators must therefore be responsive to the holistic as well as business needs of tenants.

Hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism are important within the entrepreneurial context, and are associated with successful entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g. Baluku et al., Citation2016; Baluku et al., Citation2018). Research also offers evidence that psychological capital is associated with entrepreneurship (Bockorny, Citation2015; Contreras et al., Citation2017; Hasan et al., Citation2019; Jensen & Luthans, Citation2006; Pease & Cunningham, Citation2016). These constructs provide the scaffolding to support and protect their holistic and psychological wellbeing.

Despite extensive research having examined positive psychology in organizational settings, there remain gaps in the knowledge in understanding tenants’ positive psychology at business incubators. Researchers have suggested that incubators may influence the psychological development of tenants, offering benefits to tenants (e.g. Ford, Citation2015). However very little is known about this relationship, despite calls for greater clarity about the ‘mental preparation’ of tenants to drive their own business (Shepard, Citation2013, p. 228). Further exploration of the constructs of positive psychology within incubator tenants is critical given the global value attributed to these facilities in supporting new business owners to be strong, resilient and to remain positive.

Incubator managers and tenants’ business support and psychological needs

The published literature highlights the important and significant role of managers in informing and provisioning the business supports and services that tenants receive at incubators (e.g. Apa et al., Citation2017; Monsson & Jørgensen, Citation2016; Redondo-Carretero & Camarero-Izquierdo, Citation2017). Incubator managers must establish robust, quality relationships with tenants; the strength of which is fundamental to the process of incubation (A.J. Ahmad & Ingle, Citation2011, p. 639). Incubator managers who engender a strong professional connection with their tenants have the greatest impact within an incubator (Rice, Citation2002).

Managers are thus uniquely placed, through their interaction with, and in the provision of services for tenants, to directly and indirectly provide support to tenants to address both their business and psychological needs. However, the composition and quality of the professional relationship between managers and tenants in supporting positive psychology is not well understood. The role of managers in supporting tenants’ psychological wellbeing, specifically through the positive psychology constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism, has been under-explored in the published literature. Research is needed to understand the role of incubator managers in their interactions with tenants, especially given the pervasive challenges faced by new business owners and the spread of incubators as facilities for fostering new businesses to grow and thrive.

Synthesis

A considered approach to research is required that incorporates positive psychology through the representative constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The published literature has identified that (1) managers at incubators perform wide-ranging roles including the provision of support and services to assist tenants in growing their businesses, (2) the interactions of managers and tenants are important and far reaching, and (3) constructs linked to positive psychology within occupational settings can be beneficial for individuals in their work place, and entrepreneurial activities. However, there is a dearth of published research examining the role of incubator managers in supporting tenants positive psychology in these facilities.

The aim of this research was to examine the role of managers at incubators in supporting tenants' positive psychology by conducting cross-disciplinary research, using qualitative research methods, to examine the role of incubator managers in the delivery of services that support tenants’ positive psychology, through the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The model guiding this research is conceptualized in .

Materials and methods

Sample

In-depth interviews were conducted with incubator managers (n = 28) and incubator tenants (n = 12) from the USA, UK, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand.

Measures

A semi-structured interview schedule consisting of nine open-ended questions was developed for incubator managers. It comprised questions asking managers to reflect on their perceptions and insights about their professional role and relationship in supporting tenants' psychological wellbeing by examining the attributes associated with the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism.

The interview schedule commenced with questions about the type of incubator and the role they were employed in at their incubator, and the advantages and disadvantages for tenants in operating their business within the incubator. The interview schedule included questions that explored whether the incubator had supported tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing linked to the attributes associated with the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism (see Appendix). This included the contribution and influence in building tenants’ business confidence (efficacy), in progressing and succeeding at their business goals while addressing challenges that can derail goal achievement (hope), the ways in which they approach and direct current and future business activities (optimism) and how challenges have been met and overcome (resilience) for them and their business. The final question in the interview schedule asked what role incubator managers had in supporting tenants’ wellbeing as they develop their businesses.

A semi-structured interview schedule for incubator tenants was also developed. It consisted of 14 open-ended questions about tenants’ experiences at the incubator. The questions were similar in focus and content to the interview schedule used with the incubator managers to obtain insights from tenants about their experiences at the incubator. The interview schedule commenced with questions about the type of incubator tenants were located in, the reasons for moving to and growing their business at a business incubator, and the contribution and influence of the incubator on their business and whether the incubator had met their expectations.

The interview schedule also included questions about how the incubator had supported tenants’ psychological wellbeing by examining the attributes associated with the constructs of hope (succeeding at their business goals despite challenges), efficacy (building their business confidence), resilience (how challenges have been met and overcome), and optimism (the ways in which they approach and direct current and future business activities with positive expectancy). These questions are included in the Appendix. Tenants were also asked about the role of incubator managers and staff in delivering activities and services at the incubator that supported tenants, their wellbeing and how this may have contributed to, and supported their business. The interview questions were developed by the researchers and broadly informed by previous research (i.e., Al-Mubaraki & Busler, Citation2010; Albort-Morant & Orghazi, Citation2016; Cohen, Citation2013; Gerlach & Brem, Citation2015; Kemp, Citation2013; Monsson & Jørgensen, Citation2016; Roseira et al., Citation2014; Schwartz & Hornych, Citation2010; Tavoletti, Citation2013).

Procedure

Emails about the research were sent to peak incubator associations (n = 31) in 23 countries including Armenia, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, New Zealand, Poland, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, The Netherlands, UK, USA. The peak incubator associations were identified from a) publicly accessible directories, b) public resources available from the International Business Innovation Association website, and c) a search of the internet.

Emails about the research were also sent to individual incubators (n = 822) located in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Singapore, UK, USA. A database for individual incubators was compiled by the lead researcher using publicly accessible directories and internet searches. Individual incubators and peak organizations were only contacted if their website was written in English.

The email invitations included information about the research and requested assistance in contacting incubator managers and incubator tenants. Managers and tenants were invited to participate in an online survey. At the conclusion of each survey, tenants and managers were invited to participate in an interview. A convenience sample was adopted for this study: the inclusion criteria for participants were being aged 18 years or older and being employed at/being a tenant located in a business incubator.

Semi-structure, in-depth interviews were conducted either in person (n = 3), via telephone (n = 35), or using video-enable software such as Skype for Business (n = 2). Interviews were recorded and later transcribed verbatim as written documents for coding and analysis. The average duration of interviews was 51.65 minutes for incubator managers and 55.66 minutes for incubator tenants.

Ethics approval was granted from a University Human Research Ethics Committee. Written and/or verbal consent (recorded) was obtained for all participants completing the interviews.

Qualitative data analysis

Interview transcripts were coded to enhance the manageability of the raw text and to identify patterns in the data (such as similarities or differences in the ideas presented), thus enabling data to be categorized for greater meaning (Saldana, Citation2016). Coding also provided the foundation from which constructs were developed from the theoretical narrative (Auerbach & Silverstein, Citation2003). The procedure for coding was consistent with the methods outlined by Auerbach and Silverstein (Citation2003). This approach shares similarities with structural coding methods where data is coded to detect significant phrases or content in the interviews that align with the research areas under examination. This approach to coding is also well-suited for semi-structured methods of data collection and hypothesis testing (Saldana, Citation2016). The interview transcripts, and subsequent themes, were coded separately for managers and tenants.

Results

Twenty-eight directors, managers or CEOs at incubatorsFootnote2 (males, n = 16; females, n = 12) located in the USA (n = 15), UK (n = 6), Australia (n = 5), Ireland (n = 1), and New Zealand (n = 1), participated in interviews. Interviews were also conducted with 12 tenants (males, n = 5; females, n = 7) from incubators located in Australia (n = 6), the USA (n = 4) and the UK (n = 2).

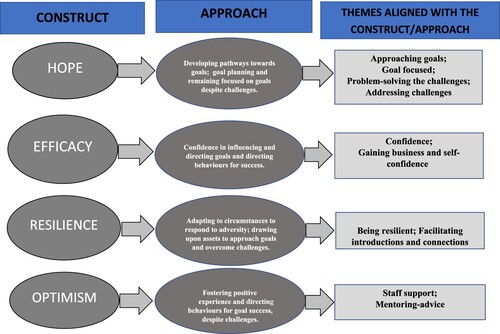

A total of ten themes were identified following separate analyses of the manager and tenant interview data; these are summarized in . Each theme is associated with the delivery of services and support by incubator staff and the contribution this support had on tenants, personally and professionally.

Table 1. The themes identified from interviews with managers (n = 28) and tenant (n = 12) about the role and contribution of incubators and the supports and services provided to tenants aligned with the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism.

The themes offer evidence of managers supporting tenants’ hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The variation in themes between managers and tenants reflects their perspectives about incubators based upon their different roles within the incubator, with the data having been themed to the constructs themselves. These include:

HOPE: Four themes including ‘goal focused’ and ‘problem-solving the challenges’, and ‘approaching goals’ and ‘addressing challenges’ support tenants’ goal development, despite challenges, and are representative of the attributes aligned to the construct of hope;

EFFICACY: Two themes including ‘confidence’ and ‘gaining business and self-confidence’, support tenants’ confidence and share similarities with the attributes associated with the construct of efficacy;

RESILIENCE: Two themes ‘being resilient’ and ‘facilitating introductions and connections’ support tenants to draw upon resources (assets) to overcome challenges and shares similarities with the attributes associated with the construct of resilience;

OPTIMISM: Two themes including ‘mentoring-advice’ and ‘staff support’ build tenants’ positive expectancy and share similarities with the attributes aligned with the construct of optimism.

A detailed description of the variant themes is presented in (managers) and (tenants). Representative quotes from managers and tenants provide evidence drawing upon the narrative experiences from tenants and managers about the incubator and the support and services received. depicts the themes identifed through this research, linked to the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism.

Table 2. The themes and representative quotes from manager interviews (n = 28), categorized into the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism.

Table 3. The themes and representative quotes from tenant interviews (n = 12) categorized into the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism.

Discussion

Research was conducted to examine whether managers support tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing, through the constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The research provides evidence that managers perform an important role by providing substantive support to tenants. Their reach is expansive and the assistance they provide is often holistic, supporting tenants professionally and personally, with their business. The narrative insights from interviews with managers and tenants consistently demonstrate the breadth of the interactions between managers and tenants, highlighting the practical business support, assistance and advice offered which also supports tenants’ psychological wellbeing, hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. This research confirms that the provision of managerial support at incubators contributes to tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing.

The breadth of management support for tenants

The qualitative data consistently demonstrates the role of managers and the impact they have on tenants. Managers deliver support to tenants which is wide-ranging, comprising professional advice to practical solutions and delivered as mentoring and advice or through the sharing of skills. They also provide assistance with establishing contacts and networks to enable tenant businesses to flourish. The narrative experiences of tenants and managers in the themes of ‘staff support’ and ‘mentoring-advice’ offer consistent insights that support this finding, while also highlighting that the support delivered to tenants by managers is nuanced to meet the unique needs of tenants.

The provision of advice and support delivered by managers is thus tailored to tenants’ individual business needs and their own unique circumstances. Furthermore, the support from managers is informed, personable and empathic indicating a deep level of consideration for tenants and their business needs. The role of incubator managers necessitates their support and guidance, both personally and professionally, to overcome the challenges the tenant is experiencing. This study corroborates previous research about the importance of establishing strong relationships between incubator managers and tenants (A. J. Ahmad & Ingle, Citation2011) that have the potential to have a significant impact within an incubator (Rice, Citation2002). The breadth of advice, the strength of the relationships established, and the demonstrated understanding and support delivered by managers to tenants are evident in each of the themes identified in this research.

Tenants’ narrative experiences indicate that this support is well received and valued. This finding is consistent with the published literature (e.g. Apa et al., Citation2017; Bruneel et al., Citation2012; Monsson & Jørgensen, Citation2016; Redondo & Camarero, Citation2017) highlighting that incubator managers are integral in providing assistance to tenants and their businesses which includes the provision of support and advice for business development and growth. Their interactions with tenants, the individuality of the advice, and the consideration and support provided to tenants are consistent with published research evidence.

However, there is a notable expansion to knowledge identified in the present study: that of the ubiquitous role and influence of managers in supporting tenants’ positive psychological needs. The present research shows a clear relationship between managers and tenants, which supports the constructs that constitute positive psychological wellbeing, specifically hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. This area of research has received very little attention in the published literature to date.

Tenants’ hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism

The thematic evidence suggests the breadth of the support delivered directly and indirectly by managers, is addressing tenants’ psychological wellbeing and is empowering tenants in their business. Managers consistently provide tenants with support and services that guide them to approach and achieve their business goals, to be confident and remain realistic and positive, to address challenges, and to develop assets and resources that aid them and their businesses. These are the building blocks that comprise the important psychological constructs of hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. Developing and enhancing these constructs are targeted through the strategies that managers adopt when interacting with and supporting tenants.

The thematic evidence demonstrates that managers guide, advise, and support tenants to remain focused on, and to achieve, their business goals despite challenges as exemplified in the themes ‘approaching goals’ and of being ‘goal focused’ ‘problem-solving the challenges’ and ‘addressing challenges’. These themes are aligned with the attributes associated with the construct of hope and of planning a course of action, or pathways that support goal achievement while avoiding or directly addressing barriers that can prevent goal achievement (Luthans, Citation2002; Luthans et al., Citation2004; Snyder, Citation2000).

The consistent methods employed by incubator managers to empower tenants’ to be confident in themselves and their business, provides further evidence of the contribution of managers in supporting the psychological needs of tenants. The themes ‘gaining business and self-confidence’ and ‘confidence’ share similarities with the attributes associated with the positive psychological construct of efficacy. This includes influencing and directing an individual towards successful outcomes and is synonymous with confidence and the commitment in one’s abilities to direct and action change, and control events for a desired outcome (Bandura, Citation1993; Luthans et al., Citation2015).

Resilience enables an individual to positively adapt to adverse circumstances that optimize personal outcomes while utilising assets that can provide protection in response to adversity (Garcia-Dia et al., Citation2013; Masten, Citation2014). The theme ‘being resilient’ provides evidence that incubator managers actively support and encourage tenants to be resilient particularly when faced with challenges and problems. The provision of staff support is an asset that tenants can draw upon for assistance with overcoming difficulties in their business. The theme ‘facilitating introductions and connections’ offers further evidence of the support of staff in building tenants’ connections, both within the incubator and with other tenants, and to businesses that are external to the incubator. Establishing the connections for tenants through these networks further strengthens the resources and assets (which include other tenants and managers/staff at incubators) that tenants can then draw upon and access. This provides tenants with assets, such as colleagues and connections to peers, that can assist with, or act as a buffer when challenges arise. Resilience is particularly important for incubator tenants as they navigate the challenges of a new business, providing a mechanism to assist them in responding positively to the challenges they are experiencing.

Managers provide tenants with advice and support, through mentoring and coaching, that engenders a sense of positivity and optimism for tenants and their businesses. The themes ‘staff support’ and ‘mentoring-advice’ describe similarities consistent with the construct of optimism and an expectation for success which directs an individual towards their goals despite inevitable challenges (Carver et al., Citation2010).

These findings demonstrate that incubator managers are providing substantial support, addressing the business and wellbeing needs of tenants through their hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. These four constructs lead to positive behaviours and attitudes within organizational settings. Evidence shows that these constructs manifest in various ways, including goal achievement (Friend et al., Citation2016) and positive workplace performance, commitment, and satisfaction (e.g. Reichard et al., Citation2013; Youssef & Luthans, Citation2007), effective goal setting and job satisfaction (Luthans et al., Citation2015), of managing challenging, high-demand work settings (Luthans et al., Citation2015; McGarry et al., Citation2013) and having elevated motivation (Luthans, Citation2002) and goal persistence (Carver et al., Citation2010; Monzani et al., Citation2015).

Collectively, the research evidence highlights that incubator staff are influential in the positive psychological development of tenants. This finding extends the existing understanding of the importance of incubators in supporting new business owners. Only a handful of previous studies have made connections between psychological constructs and tenants at incubators (e.g. Baluku et al., Citation2016; Ford, Citation2015) with this research now offering deeper insights into the substantive, holistic role of incubator managers.

This research offers important new insights demonstrating that incubator managers offer tenants greater support, beyond that which is centred solely on their business. The breadth of support delivered by managers is far-reaching, providing an essential and albeit lesser recognized role of (a) actively supporting tenants to approach their goals and provide assistance to overcome challenges to goal approach (hope), (b) actively developing tenants’ confidence (efficacy) in themselves, (c) providing connections with other tenants and businesses who then provide support and resources to guide tenants when they experience challenges (resilience), and (d) enabling positivity and expectation in tenants (optimism) as they progress their business.

Entrepreneurs and new businesses face unique challenges associated with contextual and situational factors (Zahra et al., Citation2014) and as such, the support for fostering these positive psychological constructs may provide the scaffolding that protects and supports tenants’ holistic wellbeing, including their psychological wellbeing. In constructed environments such as business incubators, which have been established to support and foster entrepreneurship and new businesses, there is much potential for managers to continue to foster these constructs in tenants to maximize their benefits.

Industry implications

This research highlights that incubator managers are instrumental in supporting tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing. It is therefore essential that greater provision and access to information is given to managers to optimize the support they provide to tenants. Incubator managers must continue to provide the support that they are already effectively delivering to tenants but with the incorporation of additional methods that will extend the assistance they provide tenants to approach goals, to have the ability to overcome challenges, to remain positive, and to draw upon their assets to overcome problems and go beyond. Training to support managers to enable them to continue to foster and expand the support they provide tenants, and which addresses tenants’ business as well as psychological wellbeing, is recommended.

The evidence from this study emphasizes that the role of incubator managers is diverse, complex, and expansive and involves close and strong interactions with tenants (and others internal and external to the incubator), to meet and address their needs. The importance of the manager-tenant interactions necessitates greater recognition of the role that incubator managers assume, and the necessity for time preservation to ensure they can effectively interact with tenants to support their business and psychological needs.

There is much potential for implementing a consistent and integrated model of support at all incubators that is promoted throughout the industry. This would recognize the significant contribution of managers in supporting tenants’ and optimising their holistic needs for business success. This has the potential to expand the broader outcomes linked to success that many of today’s incubators strive for, including enhanced economic development, jobs growth, skills creation, and network building (Ayatse, Kwahar, & Iyorsuun, Citation2017; Isabelle, Citation2013; Tang, Baskaran, Pancholi, & Lu, Citation2013; Tavoletti, Citation2013).

Many of the managers in this study had previous entrepreneurial and business experience. This was identified in the narrative reflections indicating that this previous experience brings advantages to the manager role at incubators. This knowledge informs and guides the support and advice they provide tenants. This is consistent with previous research whereby managers with entrepreneurial experience have greater influence and have the capacity to effect personal and business assistance, and networking for tenant-businesses (Redondo & Camarero, Citation2017).

Indeed, the importance attributed to establishing tenant networking and trusted relationships, both within and external to the incubator, is identified in this study. While past research attests to the value of networking for tenants at incubators (e.g. Bergek & Norrman, Citation2008; Scillitoe & Chakrabarti, Citation2005), this research provides evidence that networking can facilitate hope by developing and supporting tenants’ business goals. Building connections within and external to the incubator may also assist in supporting tenants’ resilience by establishing the connections and assets that may help buffer challenges that tenants may experience.

Likewise, establishing trusted relationships is essential to the support delivered by managers to tenants. Generating trust at incubators is necessary and important for healthy-functioning incubators but in this study, trust contributes to the wellbeing of tenants. Developing trust within the incubator is essential in these deeply constructed settings in which there is potential for conflict, suspicion, and distrust to occur between tenants and where tenants may consider other tenants as potential or actual competition, especially when they share similar business markets (McAdam & Marlow, Citation2007). The managers’ role is thus essential in establishing trust and generating strong, mutually supportive and cohesive networks between incubator tenants (e.g. Schwartz & Hornych, Citation2010; Tottenham & Sten, Citation2005).

It is therefore recommended that previous entrepreneurial and business experience is a pre-requisite of business incubator managers and senior incubator staff. Likewise, the personal qualities and attributes of managers in their interactions with tenants - that includes showing respect, empathy, and facilitating trust - should be a pre-requisite when selecting and employing managers and support staff at incubators. Similarly, in recognition of the importance and breadth of the role that incubator managers provide to tenants’ in supporting their positive psychological wellbeing, it is recommended that these duties are formally and closely aligned with the support and activities that promote tenant’s hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism.

Limitations and future research

Further research is now required to explore the benefits of incubators on tenants’ positive psychological development. Managers play an integral role at incubators in supporting tenants’ wellbeing. Further examination to determine the extent of this relationship, and to identify the most valued styles and methods for delivering this support to tenants is required. The present findings offer significant new insights but now require verification and expansion to identify other potential incubator factors that enhance or diminish tenants’ psychological wellbeing.

Likewise, future research should also explore the relationship between tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing and their potential business success. Research could be undertaken to examine tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing, as fostered through the incubator, and the impact on small business performance and success using measures that include business revenue, jobs creation, and innovation outputs (e.g. Lukeš et al., Citation2019; Sedita et al., Citation2019). This research would complement and extend the present findings, documenting the impact of tenants’ positive psychology on the success, growth and longevity of new and small businesses located within incubators.

In this study, convenience sampling was adopted and all tenants and managers from any incubator were included in the study, irrespective of variations in the composition of incubators and the countries from which they originate. The differences and similarities between incubators were not explicitly examined in the research. It is therefore recommended that future research further explores the characteristics of incubators to identify if this influences the level and scope of support provided to tenants.

The qualitative research design adopted in this research deviates from the traditional, quantitative research approaches frequently used when examining incubators. Interviews provide an important mechanism for collecting in-depth narratives from incubator tenants and managers about their experiences, providing the foundation for deeper understanding and learning. This approach is recommended for future research, alone or in tandem with quantitative methods, to further examine the relationships between managers and tenants in supporting wellbeing.

Finally, hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism are the building blocks for psychological capital; a higher-order construct enabling individuals to develop and thrive as they move, in a dynamic and adaptable way, towards their desired outcomes, enabling them to assess, respond to, and overcome the challenges that they will inevitably experience (Avey et al., Citation2010). Exploring the potential relationship between psychological capital, managers and tenants at incubators necessitates an important step in extending entrepreneurial research.

Conclusion

This study offers new evidence that incubator managers are supporting tenants’ positive psychological wellbeing. Interviews with managers and tenants provide detailed, narrative insights that managers are effectively interacting with and supporting tenants. Importantly the study demonstrates the contribution of incubator managers in fostering tenants’ approaches to their goals (hope), their confidence in their business (efficacy), their ability to overcome and avoid negative challenges through the development and utilization of assets (resilience) and being realistic and positive in their approach to their business (optimism). The evidence offers new insights into the importance of the incubator manager during their interactions with tenants. The findings have broad implications for the sector and in operationalising the role of managers particularly in preserving and fostering the important daily interactions they have with tenants which support their business and psychological wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank the incubator managers and tenants who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For this research, tenants refers to participants of business incubator programs, including new business owners, and entrepreneurs. In the USA, tenants are often referred to as incubatees.

2 While participants were employed in roles at incubators with different titles, the collective term ‘manager’ will continue to be used, reflecting the seniority in the roles that they hold at incubators.

References

- Aernoudt, R. (2004). Incubators: Tool for entrepreneurship?. Small Business Economics, 23(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000027665.54173.23

- Ahmad, J. A. (2014). A mechanisms-driven theory of business incubation. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 20(4), 375–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2012-0133

- Ahmad, A. J., & Ingle, S. (2011). Relationships matter: Case study of a university campus incubator. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 17(6), 626–644. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551111174701

- Al-Mubaraki, H. M., & Busler, M. (2010). Business incubators: Findings from a worldwide survey, and guidance for the GCC states. Global Business Review, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215090901100101

- Albort-Morant, G., & Orghazi, P. (2016). How useful are incubators for new entrepreneurs? Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2125–2129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.019

- Apa, R., Grandinetti, R., & Sedita, S. R. (2017). The social and business dimensions of a networked business incubator: The case of H-farm. Journal of Small Business & Enterprise Development, 24(2), 198–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-07-2016-0103

- Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York University Press.

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2010). The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(2), 430–452.

- Ayatse, F. A., Kwahar, N., & Iyorsuun, A. S. (2017). Business incubation process and firm performance: An empirical review. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 7(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0059-6

- Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., Bantu, E., & Otto, K. (2018). Psychological capital and entrepreneurial outcomes: The moderating role of social competences of owners of microenterprises in East Africa. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(26), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0113-7

- Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., & Kibanja, G. M. (2016). Psychological capital and the startup capital-entrepreneurial success relationship. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 28(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2015.1132512

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy. Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

- Bergek, A., & Norrman, C. (2008). Incubator best practice: A framework. Technovation, 28(1-2), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2007.07.008

- Bliemel, M. J., Flores, R. G., Hamilius, J., & Gomes, H. (2014). Accelerate Australia Far: Exploring the emergence of seed accelerators within the innovation of ecosystem Down-Under (Research Paper No 2014 MGMT 02). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2422173.

- Bockorny, K. M. (2015). Psychological capital, courage, and entrepreneur success. (Doctoral thesis), Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (ProQuest No: 3725236).

- Bøllingtoft, A. (2012). The bottom-up business incubator: Leverage to networking and cooperation practices in a self-generated, entrepreneurial-enabled environment. Technovation, 32(5), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.11.005

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience. American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

- Breivik-Meyer, M., Arntzen-Nordqvist, M., & Alsos, G. A. (2020). The role of incubator support in new firms accumulation of resources and capabilities. Innovation, 22(3), 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2019.1684204

- Bruneel, J., Ratinho, T., Clarysse, B., & Groen, A. (2012). The evolution of business incubators: Comparing demand and supply of business incubation services across different incubator generations. Technovation, 32(2), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.11.003

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006

- Cohen, S. (2013). What do accelerators do? Insights from incubators and angels. Innovations: Technology, governance. Globalization, 8(3/4), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1162/inov_a_00184

- Contreras, F., de Dreu, I., & Espinosa, J. C. (2017). Examining the relationship between psychological capital and entrepreneurial intention: An exploratory study. Asian Social Science, 13(3), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v13n3p80

- Cooper, C. E., Hamel, S. A., & Connaughton, S. L. (2012). Motivations and obstacles to networking in a university business incubator. Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(4), 433–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9189-0

- Dawkins, S., Martin, A., Scott, J., & Sanderson, K. (2013). Building on the postives: A psychometric review and critical analysis of the construct of social capital. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(3), 348–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12007

- Ford, C. (2015, September 10–13). Beyond a social capital agenda: Exploring metrics and motives inside business incubators in Arkansas. Paper presented at the 5th international conference on engaged management scholarship, Baltimore, MD. Paper http://ssrn.com/abstract=2676288.

- Friend, S. B., Johnson, J. S., Luthans, F., & Sohi, R. S. (2016). Positive psychology in sales: Integrating psychological capital. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 24(3), 306–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2016.1170525

- Garcia-Dia, M. J., DiNapoli, J. M., Garcia-Ona, L., Jakubowski, R., & O’Flaherty, D. (2013). Concept analysis: Resilience. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(6), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.003

- Gerlach, S., & Brem, A. (2015). What determines a successful incubator? Introduction to an incubator guide. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 7(3), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2015.071486

- Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M. (2004). A systematic review of business incubation research. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011181.11952.0f

- Hasan, M., Hatidja, S., Nurjanna, N., Guampe, F. A., Gempita, M. I., & Maruf, M. I. (2019). Entrepreneurship learning, positive psychological capital and entrepreneur competence of students: A research study. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(1), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.7.1(30)

- Isabelle, D. A. (2013). Key factors affecting a technology entrepreneur's choice of incubator or accelerator. Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(2), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/656

- Jensen, S. M., & Luthans, F. (2006). Entrepreneurs as authentic leaders: Impact on employees’ attitudes. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 27(8), 646–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730610709273

- Kemp, P. (2013). The influence of business incubation in developing new enterprises in Australia (Master of Management: Research, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia). https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1865&context=theses.

- Lewis, D. A., Harper-Anderson, E., & Molnar, L. A. (2011). Incubating Success. Incubation best practices that lead to successful ventures. http://edaincubatortool.org/pdf/Master%20Report_FINALDownloadPDF.pdf .

- Lorenz, T., Beer, C., Putz, J., & Heinitz, K. (2016). Measuring psychological capital: Construction and validation of the compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12). PLoS One, 11(4), e0152892–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152892

- Lukeš, M., Longo, M. C., & Zouhar, J. (2019). Do business incubators really enhance entrepreneurial growth? Evidence from a large sample of innovative Italian start-ups. Technovation, 82-83, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.07.008

- Luthans, F. (2002). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2002.6640181

- Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Peterson, S. J. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20034

- Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2002). Hope: A new positive strength for human resource development. human Resource Development Review, 1(3), 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484302013003

- Luthans, F., Luthans, K. W., & Luthans, B. C. (2004). Positive psychological capital: Beyond human and social capital. Business Horizons, 47(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2003.11.007

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 339–366. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113324

- Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press.

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford University Press.

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives of resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205

- McAdam, M., & Marlow, S. (2007). Building futures or stealing secrets? Entrepreneurial cooperation and conflict within business incubators. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 25(4), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607078563

- McGarry, S., Girdler, S., McDonald, A., Valentine, J., Lee, S.-L., Blair, E., … Elliott, C. (2013). Paediatric health-care professionals: Relationships between psychological distress, resilience and coping skills. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 49(9), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12260

- Mealer, M., Jones, J., Newman, J., McFann, K. K., Rothbaum, B., & Moss, M. (2012). The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(3), 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.015

- Meyer, N., Meyer, D. F., & Kot, S. (2016). Best practice principles for business incubators: A comparison between South Africa and the Netherlands. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 5(19), 1110–1117.

- Monsson, C. K., & Jørgensen, S. B. (2016). How do entrepreneurs’ characteristics influence the benefits from the various elements of a business incubator? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(1), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-10-2013-0158

- Monzani, D., Steca, P., Greco, A., D’Addario, M., Pancani, L., & Cappelletti, E. (2015). Effective pursuit of personal goals: The fostering effect of dispositional optimism on goal commitment and goal progress. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.019

- Pease, P., & Cunningham, J. (2016, September 4–8). Entrepreneurial psychological capital: A different way of understanding entrepreneurial capacity. Paper presented at the British academy of management conference: Thriving in turbulent times, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Paper http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/29241/.

- Peters, L., Rice, M., & Sundararajan, M. (2004). The role of incubators in the entrepreneurial process. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011182.82350.df

- Redondo-Carretero, M., & Camarero-Izquierdo, C. (2017). Relationships between entrepreneurs in business incubators. An exploratory case study. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 24(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051712X.2016.1275826.

- Redondo, M., & Camarero, C. (2017). Dominant logics and the manager’s role in university business incubators. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 32(2), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2016-0018

- Reichard, R. J., Avey, J. B., Lopez, S., & Dollwet, M. (2013). Having the will and finding the way: A review and meta analysis of hope at work. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(4), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.800903

- Rice, M. P. (2002). Co-production of business assistance in business incubators: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00055-0

- Robinson, S., & Stubberud, H. A. (2014). Business incubators: What services do business owners really use? International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 18, 29–39.

- Roseira, C., Ramos, C., Maia, F., & Henneberg, S. (2014). Understanding incubator value. A network approach to university incubators. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2686/0fbe777ab5e7aa254c4f7e14664283a8e188.pdf.

- Saldana, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed). Sage.

- Schwartz, M., & Hornych, C. (2010). Cooperation patterns of incubator firms and the impact of incubator specialisation: Empirical evidence from Germany. Technovation, 30(9-10), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.05.001

- Scillitoe, J. L., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (2005). The sources of social capital within technology incubators: The roles of historical ties and organizational facilitation. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 2(4), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2005.008089

- Sedita, S. R., Apa, R., Bassetti, T., & Grandinetti, R. (2019). Incubation matters: Measuring the effect of business incubators on the innovation performance of start-ups. R&D Management, 49(4), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12321

- Shepard, J. M. (2013). Small business incubators in the USA: A historical review and preliminary research findings. Journal of Knowledge-Based Innovation in China, 5(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKIC-07-2013-0013

- Shepherd, D. A., Souitaris, V., & Gruber, M. (2021). Creating new ventures: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 47(1), 11–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319900537

- Snyder, C. R. (2000). Handbook of hope. Academic Press.

- Snyder, C. R., Cheavens, J., & Sympson, S. C. (1997). Hope: An individual motive for social commerce. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 1(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.1.2.107

- Snyder, C. R., Feldman, D. B., Taylor, J. D., Schroeder, L. L., & Adams, V. H. (2000). The roles of hopeful thinking in preventing problems and enhancing strengths. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 9(4), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(00)80003-7

- Tang, M., Baskaran, A., Pancholi, J., & Lu, Y. (2013). Technology business incubators in China and India: A comparative analysis. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 16(2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2013.10845635

- Tavoletti, E. (2013). Business incubators: Effective infrastructures or waste of public money? Looking for a theoretical framework, guidelines and criteria. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 4(4), 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-012-0090-y

- Tottenham, H., & Sten, J. (2005). Start-ups: Business incubation and social capital. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 23(5), 487–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242605055909

- Vedel, B., & Gabarret, I. (2014). The role of trust as mediator between contract, information and knowledge within business incubators. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 23(4), 509–527. DOI: hal-01886222. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2014.065685

- Youssef, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2007). Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management, 33(5), 774–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307305562

- Zahra, S. A., Wright, M., & Abdelgawad, S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 32(5), 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613519807