Abstract

Research indicates that indirect exposure to trauma can have a detrimental psychological impact on professionals working within, and interfacing with, law enforcement and the criminal justice system. This systematic review aimed to explore the extent and predictors of work-related distress amongst community corrections personnel. A search of five databases identified 19 papers eligible for inclusion; 16 addressed burnout, and the remainder investigated secondary trauma, vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue. Synthesis revealed that community corrections personnel reported burnout at levels akin to those of other professions working in forensic contexts, though reports of secondary trauma appeared higher. Predictive factors encompassed personal, role-based and organisational factors. Research reporting work-related distress in correctional officers is focused on burnout but uses divergent models of stress, reveals methodological weaknesses, and to date has little examined responses to indirect trauma. The limitations of this review are discussed, alongside clinical implications and areas for future research.

Community corrections personnel

Community correction personnel, encompassing both parole and probation officers, primarily supervise offenders within the community. Parole officers’ duties include supervision of offenders either after completing a prison sentence or once released on license. Probation officers, by contrast, largely work with individuals who have been sentenced to non-custodial sanctions within the community or who are awaiting sentencing. These distinct roles can vary across locations and often overlap dependent on policies and provisions applied in differing global contexts and legislatures.

Common to both roles are the supervision and management of offenders within the community. This requires ensuring that offenders fulfil the conditions of their sanction and rehabilitative activity, supporting them to adjust to community life and social and behavioural changes (Hsieh et al., Citation2015). This latter role has parallels with social work (Ohlin et al., Citation1956; Raynor & Vanstone, Citation2016), reliant on officers building a therapeutic and facilitative relationship with their clients (J. Miller, Citation2015; Spiess & Johnson, Citation1980).

In such multi-faceted roles, exposure to emotionally charged materials is inevitable; assessments of offenders’ criminal and social backgrounds necessitate reading of police reports and victim "statements. Given extensive trauma in offenders’ histories (e.g. Wilson et al., Citation2013), and its association with criminal behaviour (e.g. Kirk & Hardy, Citation2014), community correction officers (CCOs) may regularly be exposed to details of traumatic and violent crimes committed either by or towards their client. Home visits and establishing relationships with family members of the offenders expose CCOs to the wider impact of offenders’ crimes (diZerega & Verdone, Citation2011; Lewis et al., Citation2013), as well as intergenerationally transmitted trauma on offenders themselves (Halsey, Citation2018; Will et al., Citation2016). Such consistent indirect contact with trauma may render CCOs vulnerable to experiencing work-related distress (WRD), impeding their ability to carry out their roles effectively.

Work-related distress

Substantial literature over the last three decades has revealed that trauma’s impact extends beyond direct exposure (e.g. Beck, Citation2011; Greinacher et al., Citation2019). Burgeoning numbers of studies highlight that indirect experiences of trauma can also have adverse effects, suggesting that those in contact with a traumatised individual are at risk of developing significant emotional and psychological difficulties (Cocker & Joss, Citation2016; Elwood et al., Citation2011; Sinclair et al., Citation2017).

The impact of indirect exposure to trauma on professionals has been operationalised through a number of concepts, the most notable of which are described here. ‘Burnout’ communicates the physical, emotional and psychological impacts of chronic exposure to work stress from working with others during intensely emotive situations (e.g. Pines & Aronson, Citation1988). Symptoms include emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced perceived personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Subsequent conceptions of WRD include ‘secondary traumatic stress’ (STS), a trauma response arising through engagement with another’s trauma and suffering (CitationFigley, 1995). The symptoms echo those of post-traumatic stress disorder (CitationFigley, 2002), including hypervigilance, flashbacks and nightmares (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Similar to STS, the term ‘vicarious trauma’ (VT) describes a response to prolonged empathic engagement with a trauma survivor, altering cognitive schemas regarding the self, others and the world (Pearlman & Mac Ian, Citation1995). Finally, ‘compassion fatigue’ (CF), often used interchangeably with STS and VT, encapsulates emotional and physical fatigue as a consequence of chronic use of empathy when working with trauma survivors (CitationFigley, 2002).

Whilst the proliferation of concepts describing and explaining WRD has led to increased awareness of the impact of indirect exposure to trauma, they are critiqued as often applied interchangeably, creating confusion about their distinctive character and their precise phenomenology. CF and STS have been viewed as substitutable, yet other research describes CF as comprising characteristics of both STS and burnout (Adams et al., Citation2008). Construct validity has also been criticised (Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, Citation2003; Sinclair et al., Citation2017), with some researchers suggesting that CF is ill-defined and ambiguous (Fernando & Consedine, Citation2014; Ledoux, Citation2015). Given the range in terminology used within the literature, and the absence of a broad-ranging review of correctional officer stress, the current review will adopt the use of ‘work-related distress’ (WRD) to encompass all forms of consequences of exposure to another’s traumatic material at work, such as CF, STS, burnout and VT, to ensure a comprehensive analysis of the literature. Use of WRD also moves away from implying that the constructs are unique risks to specific occupations, such as the ‘caring’ professions (Newell & MacNeil, Citation2010).

Evidence of work-related distress

Regardless of the terminology used, professionals working with trauma survivors are susceptible to developing WRD, particularly in the caring professions across diverse healthcare settings (Huggard et al., Citation2017; Sorenson et al., Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2019), first-responders (Greinacher et al., Citation2019), and emergency service personnel including firefighters (Jo et al., Citation2018), ambulance officers (Regehr et al., Citation2002) and police officers (Sherwood et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the prevalence of WRD has been evidenced by non-clinical staff groups within the criminal justice system, notably judges (Lustig et al., Citation2008), lawyers (Levin et al., Citation2011) and jurors (Lonergan et al., Citation2016). Given CCOs’ exposure to offenders, victims of crime and a context of trauma, it seems timely to examine how they might be affected.

Through CCOs’ exposure to offenders, victims of crime and a context of trauma, any WRD that CCOs experience has significant implications for the criminal justice system. For instance, WRD is associated with increased turnover and staff sickness (Kim et al., Citation2020); recent turnover rates amongst UK probation officers were at 6.3% (Ministry of Justice, MOJ, Citation2019b), an increase of around 50% since 2016, which has the potential to compromise recruitment and retention. Increased sickness absence at 10.7 days is 67% higher than the UK average (Murphy, Citation2020), conferring significant societal impacts. If remaining staff have higher caseloads, increased care burden and reduced time for client supervision, their own compromised effectiveness may undermine offender rehabilitation and reduce public safety. It therefore seems key to systematically examine WRD amongst this staff group, understand its extent and determinants, and consider how best to address distress.

Predictor variables

As extent of WRD for professionals’ exposure to traumatogenic material becomes more evident, factors that might increase risk of distress have come under greater scrutiny, notably previous and unresolved trauma history, empathic engagement with clients and client narratives focused on childhood trauma (CitationFigley, 1995). Additionally, six key organisational domains have also been advanced: control; rewards; workload; community; fairness; and values (Leiter & Maslach, Citation2004), as well as managerial responses to trauma and social support predictive of WRD in mental health professionals (Turgoose & Maddox, Citation2017), midwives (Suleiman-Martos et al., Citation2020), first-responders (Greinacher et al., Citation2019) and lawyers (Maguire & Byrne, Citation2017).

Previous literature reviews

Despite community corrections officers arguably engaging in more frequent and sustained contact with clients than other professionals within the criminal justice system (Slate et al., Citation2003), there appears no published systematic reviews examining WRD amongst this population. A previous narrative review examining generic stress amongst probation officers described workplace stress as associated with personal (including financial concerns and family matters) and organisational factors (including unnecessary paperwork and lack of time; Slate et al., Citation2000). However, the review neither adequately defined WRD nor was systematic in approach (offering no clarity regarding search process, inclusion criteria or quality appraisal).

Two reviews have more systematically examined correlates of stress and burnout in correctional officers, but only within closed correctional settings. Schaufeli and Peeters (Citation2000) reported elevated levels of stress and burnout, somewhat higher than other professional groups, with high workload, lack of role autonomy and role ambiguity predicting stress. Similarly, Finney et al. (Citation2013) reviewed the relationship between organisational stressors, stress and burnout amongst correctional officers working in adult facilities, finding that an absence of administrative and organisational support was correlated with higher levels of stress and burnout. Neither review examined work-related responses to client trauma, highlighting that a more recent and wider review of impacts within community settings is needed.

The current review

Given the potential vulnerabilities of this key professional group and absence of any previous systematic appraisal and synthesis, the current review aims to systematically review existing published literature examining the extent of WRD in CCOs, as well as predictive psychosocial factors. In doing so, this review seeks to increase understanding of the factors that might potentiate vulnerability, to both screen for and determine potential preventative or supportive strategies to mitigate distress at work. Given the relative infancy of this research field and an initial scoping review that suggested a circumscribed literature base, the review aims to explore the following questions:

What is the extent of WRD in community corrections personnel?

What psychosocial factors appear to predict WRD?

Method

Protocol

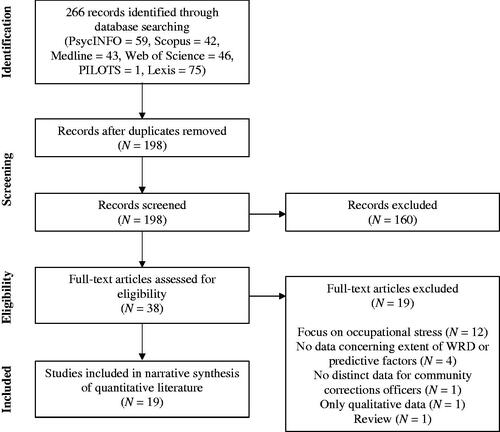

The present systematic review was undertaken following guidance by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD, Citation2009) for conducting reviews in health care and the PRISMA framework for improving transparency in systematic reviews (Moher et al., Citation2009). PROSPERO was consulted to avoid duplication, with no salient reviews recorded, though the present review was not registered. The search strategy was developed using the PICOS statement (Santos et al., Citation2007), as presented in .

Table 1. PICOS statement.

Search strategy

An initial scoping search was undertaken on Google Scholar, with a senior dedicated University librarian, to determine relevant literature reviews and provide an overview of the quantity of existing literature. This supported the focus of the current review and enabled identification of search terms typically used in the research area. On 2 September 2019, the following electronic bibliographic databases were systematically searched using both University of Leicester and NHS Athens access: PsycINFO, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, PILOTS and Lexis. The databases were selected as they cover a broad range of research from multidisciplinary professions, including psychology, medicine and law. The following search terms were employed in each database: (‘burnout’ OR ‘burn-out’ OR ‘second* trauma*’ OR ‘compassion fatigue’ OR ‘vicarious trauma*’ OR ‘PTSD’ OR ‘post-trauma*’ OR ‘trauma’ OR ‘distress’) AND (‘parole officer*’ OR ‘probation* officer*’ OR ‘community correction*’). A title, abstract and keyword search was undertaken. Filters were applied to limit included papers to those published in the English language and peer-reviewed journals.

Selection criteria of studies

Following the database searches, the remaining articles were transferred to RefWorks, and duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were then examined for relevance by the first author, guided by these eligibility criteria:

Inclusion criteria

A reported measure of WRD.

Data concerning the extent of WRD, and similar terminology, amongst CCOs.

Data concerning factors associated with or predicting WRD, and similar terminology, amongst CCOs.

Quantitative articles and mixed methods papers with clearly distinct quantitative data, to allow for the identification of data relating to the extent and predictive factors of WRD.

English language publication.

Peer-reviewed published articles.

Exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies.

Articles investigating primary forms of trauma, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), following scanning of full papers for relevance. Primary traumatisation occurs through direct first-hand experience of trauma, such as threat to life or directly witnessing threat to a loved one’s life (Branson, Citation2019). This review specifically examines the effects of indirect, rather than overt, exposure to trauma through others (WRD), which is not anticipated in the job role and is therefore inadvertent and potentially unacknowledged.

Articles investigating occupational stress, following scanning of full papers for relevance. Occupational stress is defined as a change in an individual’s physiological or psychological state in response to work-related factors that can result in negative consequences, though not necessarily (Richardson & Rothstein, Citation2008). It is not specific to work-related factors concerning the emotional toll of working with people or being exposed to indirect trauma.

Articles in which data for community corrections officers are not distinctly recorded.

Theses, dissertations, conference papers or editorial papers.

Intervention studies in which no relevant pre-intervention data are presented.

Articles not using validated measures of WRD and similar terminology.

Data extraction and synthesis

The authors created a data extraction tool adapted from previous reviews on the prevalence and predictors of WRD in other professional groups (Brooks et al., Citation2016; Sage et al., Citation2018). Shortlisted articles were read in full by the first author, and data were then extracted and tabulated using the data extraction tool, encompassing the following variables where reported: publication year, country of study, study design, the type of WRD investigated, sample size, demographics, measures used to assess WRD, relevant statistics (such as reliability coefficients and measures of association) and statistical analysis method. Key information from each article’s main aims, findings and conclusions was also extracted where relevant to the review question.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

All shortlisted articles employed a cross-sectional design. Whilst there are a range of validated tools for assessing the quality of other study designs, such as randomised-controlled trials, observational and case-control studies, the number of tools for appraising cross-sectional studies is limited (Sanderson et al., Citation2007; Zeng et al., Citation2015). Those employed to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies, such as ROBINS-I and STROBE, have questionable validity and appropriateness, particularly with regard to their specificity, applicability and generalisability (Downes et al., Citation2016). Thus, the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS; Downes et al., Citation2016) was selected to appraise the quality of all included articles. The quality appraisal was used to provide further insight regarding the research rather than to exclude articles. Four studies were randomly selected and independently assessed by the second author to compare for consistency and ensure consensus. There was agreement in ratings on all four papers.

Appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies

The AXIS is a twenty-item critical appraisal tool, developed in light of an increasing evidence-base employing cross-sectional designs and a flourishing number of systematic literature reviews utilising this study design (Downes et al., Citation2016). Created using Delphi methodology and following recommended reporting guidelines and assessment tools, AXIS pays particular attention to the methodology and results reported within a study. This provides a comprehensive and applicable tool to gauge the quality of reporting within studies, as well as the design quality and potential bias risk. Its questions cover three key aspects of research (Kiss et al., Citation2018), focusing on the design quality, reporting quality and introduction of bias.

The AXIS does not provide a numerical scale to assess overall quality of papers (Downes et al., Citation2016), and such scales have been critiqued for their lack of uniformity and consistency when weighting papers (Greenland & O’Rourke, Citation2001; Jüni et al., Citation1999). Each question in the tool was assessed individually as being met (‘yes’) or not being met (‘no’ or ‘not known’), similar to other studies (Kiss et al., Citation2018; Schoth et al., Citation2019); Questions 13 and 19 were exceptions to this rule, and reverse scoring was utilised, with a ‘no’ meeting the criteria for quality assessment. Comments were also provided when context was needed. Quality was determined based on the total number of criteria met (total = 20, ≥16 = high quality), in accordance with other studies employing AXIS (Henderson et al., Citation2019; Wong et al., Citation2018).

Results

Overview

Following the selection process, 19 papers were elicited that investigated WRD in CCOs. Of these articles, 12 included data regarding the extent of WRD, and 15 examined predictive variables. However, different definitions of WRD were investigated across the papers, as well as different measures and statistical analyses, precluding a meta-analysis of the data. The statistical analysis undertaken was explicitly stated in all but two studies (Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986; Whitehead, Citation1985). Statistical analyses varied across the articles, dependent on their aims. provides a summary of the shortlisted study characteristics.

Table 2. Study characteristics.

Selected studies characteristics

Several different terms were utilised to assess evidence of WRD amongst CCOs: burnout; emotional exhaustion; secondary trauma; VT; and CF. The majority of studies, 14 in total, operationalised WRD using the term burnout, whilst one study interchangeably used burnout and CF (Lewis et al., Citation2013). Two studies examined one specific dimension of burnout, emotional exhaustion (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018), whereas the remaining two studies investigated secondary trauma (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016) and VT (Merhav et al., Citation2018).

All studies employed purposive sampling and were recruited through various community correctional agencies and organisations, though none of the articles explicitly stated the sampling method used. Studies were conducted across the USA, Israel, China and Australia. Sample size considerably varied across the studies, ranging from 43 (Anson & Bloom, Citation1988) to 968 (Whitehead, Citation1985). Although not explicitly stated, two studies appeared to investigate different data collected from the same sample (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016, Citation2017), whilst another two studies explicitly stated that the same survey data were utilised (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018). Therefore although 19 articles were included, the present review is founded on 17 discrete samples. None of the studies described an a priori power calculation, tempering definitive conclusions regarding the generalisability of the data.

Given that studies were conducted across different countries and states, the type of community corrections role investigated also varied: five exclusively examined probation officers; five investigated a mix of probation and parole officers; two studied probation, parole officers and residential officers; three examined juvenile probation officers; one explored probation officer managers; and three referred to participants broadly as CCOs. Furthermore, three studies compared professions within the sample: between probation and parole officers; a sample of institutional correction officers and officers working in a specific ‘Supervised Intensive Restitution’ programme (Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986); between police officers and probation officers (Anson & Bloom, Citation1988); and between probation officers and a sample group of ‘human service workers’ (Whitehead, Citation1985).

Survey data collection methods were utilised by all the studies: online, face-to-face or through postal communication. All studies reported response rates, varying from 45.04% (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016, Citation2017) to 96% (Jin et al., Citation2018). Most studies (N = 12) included a greater number of females, consonant with probation services proportionately having more female staff (Ministry of Justice, Citation2019a), though seven studies reported more males within the sample.

All studies reported the measures used to gather data. In line with the present review’s aims, specific attention is paid to measures that assess WRD. All studies utilised self-report questionnaire measures, albeit diverse, partially as a result of the varied terms employed to define WRD. For burnout, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981) was most commonly adopted, assessing both the frequency and intensity of three aspects of burnout: emotional exhaustion; depersonalisation; and personal accomplishment. The MBI has excellent internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of .90 (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Two studies (Dir et al., Citation2019; White et al., Citation2015) utilised a variation of the original MBI, the MBI–General Survey (MBI–GS; Schaufeli et al., Citation1996), designed for use with occupational groups other than human services. This version of the inventory assesses emotional exhaustion, cynicism and professional efficacy; research has demonstrated that the inventory has satisfactory internal consistencies (Leiter & Schaufeli, Citation1996). Contrastingly, Lewis et al. (Citation2013) assessed both compassion fatigue and burnout by employing the Compassion Satisfaction/Fatigue Self-Test for Helpers (CFST; CitationFigley & Stamm, 1996), used to measure compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout.

Two studies (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018) investigating only one dimension of burnout, emotional exhaustion, utilised measures adapted from scales in the Children’s Services Survey (Glisson & James, Citation2002), which has good reliability (Glisson & Durick, Citation1988; Glisson & Hemmelgarn, Citation1998). Merhav et al. (Citation2018) assessed VT using the Trauma and Attachment Belief Scale (TABS; Pearlman, Citation2003), demonstrated to have good validity and good internal consistency for the total scale (α = .96), though this has ranged across the subscales (α = .67 to .87; Pearlman, Citation2003). The only study assessing secondary trauma (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016) utilised the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS; Bride et al., Citation2004), demonstrated to have excellent internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Bride et al., Citation2004).

Methodological quality of included studies

Across the included studies, quality ranged from 11 to 19 criteria met, with seven papers meeting the high-quality threshold (≥16 criteria met). See for a summary of the quality appraisal of included studies.

Table 3. Quality appraisal using AXIS checklist.

Criteria related to reporting quality were most frequently met (range = 4–7, M = 6.1). All studies clearly reported the target population and adequately described the basic data. However, nine studies did not discuss their methodological limitations, making it difficult to establish the validity of the research.

Criteria regarding study design were met less frequently (range = 2–7, M = 5.2). In all studies, the cross-sectional design was appropriate for the stated aims, whilst the outcome variables and risk factors measured were appropriate to these aims. Furthermore, all studies’ samples were taken from an appropriate population base to ensure they were representative of the population of interest. Nevertheless, only three of the studies justified sample size, and none reported on power analysis. Information regarding ethical approval or funding sources was limited.

Across the studies, criteria relating to the risk of bias were rated less well (range = 3–5, M = 3.5). Only Jin et al. (Citation2018) addressed the bias of potential non-responders within the sample, whilst Rhineberger-Dunn et al. (Citation2017) was the only study to provide any information regarding non-responder characteristics. However, across all studies the samples appeared representative of the target population, and all measures used to assess outcome variables had been trialled, piloted or published previously.

Extent of WRD

Twelve studies included information concerning the levels of WRD amongst CCOs. Irrespective of the definition, all of these studies found evidence of WRD amongst CCOs, though limited detail was provided regarding clinical significance.

The three studies exploring burnout amongst juvenile probation officers reported similar findings. Dir et al. (Citation2019), a high-quality study, reported mild to moderate levels of burnout amongst juvenile probation officers, whilst White et al. (Citation2015) reported moderate levels. Holloway et al. (Citation2019), another high-quality study, provided mean scores across the three burnout constructs that were almost identical to those reported by Dir et al. (Citation2019), suggesting similar mild to moderate levels. Whitehead and Lindquist (Citation1985), reporting on burnout, found that the majority of probation and parole officers reported emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation ‘once a month or less’, though 16% and 8%, respectively, reported experiencing them ‘once a week or more’, indicating high levels of burnout for some. In contrast, two studies (one of high quality) focusing specifically on extent of emotional exhaustion found that probation and parole officers reported high levels (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018).

In addition to reporting levels of WRD in CCOs, three studies also compared levels of WRD with those in other professions, utilising the MBI, though findings appeared equivocal. Anson and Bloom (Citation1988) investigated the difference in mean scores across the subscales of the MBI between probation officers and police officers, finding no significant difference. Similarly, Lindquist and Whitehead (Citation1986) looked at the frequency and intensity of each subscale of burnout and found no significant difference in levels of burnout between probation and parole officers compared with institutional correction officers and those working on a ‘Supervised Intensive Restitution’ programme. In contrast, Whitehead (Citation1985) reported that probation officers experienced each aspect of burnout more frequently and intensely than a sample group of human service workers (p < .05), with the exception of frequency of emotional exhaustion where human service workers reported higher levels (p < .05). Of the three studies comparing professions, Whitehead (Citation1985) was the only one to attempt to interpret their findings, concluding that probation officers were experiencing burnout on an infrequent and ‘less than intense’ level. Notably, sample demographics differed between the professional groups in these studies across gender, years of experience, age and education, and these potential confounds limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

Three studies also explored levels of WRD between different CCO roles, again with equivocal findings. Whitehead’s (Citation1986b) study of probation managers found no significant difference in levels of burnout between administrators and supervisors. Two studies of high quality also compared levels of WRD between probation and parole officers, with residential officers. Rhineberger-Dunn et al. (Citation2017) found that probation and parole officers were significantly more likely to report symptoms of emotional exhaustion (p < .05) and depersonalisation (p < .01) than residential officers, but with no difference in levels of personal accomplishment. Similarly, Rhineberger-Dunn et al. (Citation2016) reported that probation and parole officers reported a significantly greater number of STS symptoms than residential officers (p < .05).

Predictive factors of WRD

Fifteen studies reported at least one predictive factor of WRD, with similar findings across many of the papers. Only one study (Whitehead, Citation1985) did not use regression analysis or path analysis to find predictors of WRD, and seven studies also analysed correlations to demonstrate relationships between WRD and other variables.

Eleven studies identified personal characteristics; gender was found to predict WRD in three high-quality studies, though they reported conflicting findings. Both Gayman and Bradley (Citation2013) and Rhineberger-Dunn et al. (Citation2017) found that female gender predicted higher levels of emotional exhaustion, whereas Jin et al. (Citation2018) found that male gender predicted higher levels of burnout. Race was also reported as a predictor, with findings suggesting that Caucasians were likely to report higher levels of burnout than other ethnic groups (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; White et al., Citation2015). Age was another widely identified factor, with a younger age predictive of increased emotional exhaustion (Whitehead, Citation1987) and depersonalisation (Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986; Whitehead, Citation1987; Whitehead & Lindquist, Citation1985).

Respondents’ health also appeared predictive. Regarding mental health, higher reported current depression was significantly associated with higher levels of emotional exhaustion (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018), and lower physical health was a significant predictor of elevated burnout (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2017) and secondary trauma (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016) in high-quality studies. Only one study reported on personality type (Holgate & Clegg, Citation1991), with higher levels of emotionality, linked to neuroticism, predicting higher levels of emotional exhaustion. Insecure attachment style and previous human-induced trauma history were also found to significantly predict higher levels of VT (Merhav et al., Citation2018).

Organisational predictive factors were identified in 10 studies. Greater number of hours of direct contact with clients and increase in length of time in role were significantly associated with higher levels of emotional exhaustion and secondary trauma (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018; Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986; Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016; Whitehead, Citation1985, Citation1986a). Yet two studies reported that greater client contact had no relationship with emotional exhaustion but was associated with sense of personal accomplishment; Whitehead (Citation1987) found that an increase in tenure was associated with higher feelings of personal accomplishment and lower levels of burnout, whereas Rhineberger-Dunn et al. (Citation2017), a high-quality study, found that greater years in the field significantly predicted a lower sense of personal accomplishment. A further predictor, lesser job satisfaction, predicted increased burnout (White et al., Citation2015; Whitehead, Citation1986a, Citation1987).

Caseload size was explored by two studies (Gayman et al., Citation2018; Whitehead, Citation1986a), suggesting that higher caseloads were predictive of elevated burnout. Additionally, Gayman et al. (Citation2018) found that caseloads with increased numbers of those with mental health difficulties predicted higher levels of emotional exhaustion amongst probation and parole officers; yet when clients received mental health service support, staff reported decreased emotional exhaustion. Lewis et al. (Citation2013) investigated the relationship between WRD and client recidivism in caseloads, noting that those who supervised individuals who re-offended against children or committed sexual offences experienced significantly higher levels of compassion fatigue and burnout. Moreover, CCOs who received threats of harm were also likely to report significantly higher levels of fatigue and burnout.

Eight studies also evidenced role-based predictive factors, with all identifying role conflict (Allard et al., Citation2003; Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Holgate & Clegg, Citation1991; Jin et al., Citation2018; Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986; Whitehead, Citation1986a, Citation1987; Whitehead & Lindquist, Citation1985), and those experiencing higher levels of role conflict reporting higher levels of burnout. Examination of role ambiguity revealed equivocal findings. Whilst Gayman and Bradley (Citation2013), a high-quality study, reported increased role confusion related to reduced emotional exhaustion, Holgate and Clegg (Citation1991) found the obverse, that increased role ambiguity was correlated significantly with increased emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment.

Discussion

The aims of the current review were to systematically interrogate published literature on the extent and predictors of WRD amongst CCOs. Nineteen articles met inclusion criteria utilising disparate conceptualisations of WRD, with the majority of papers examining burnout and proportionately few examining trauma-related responses.

All but three studies investigated burnout (Lewis et al., Citation2013; Merhav et al., Citation2018; Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016), an understandable but narrow focus when considering WRD from a perspective of sustained, intense work with a substantial client caseload. A consistent finding across studies demonstrated burnout at mild to moderate levels and commensurate with other professionals working with offenders, notably institutional corrections officers and police officers (Anson & Bloom, Citation1988; Lindquist & Whitehead, Citation1986). However, across most papers it was unclear how the extent of burnout was determined, and explicit comparison to population norms would contextualise the extent of distress that CCOs report. That burnout as an outcome is assessed in 16 papers suggests a significant and growing awareness of the deleterious impacts of distress engendered through work with offenders, and such a body of research offers a substantial basis on which to consider and develop supportive interventions.

Regarding dimensions of burnout, high levels of emotional exhaustion (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Gayman et al., Citation2018) were prominent, mirroring levels widely reported by social workers (Morse et al., Citation2012; Paris & Hoge, Citation2010). Aspects of CCO roles are akin to social work, relying on effective therapeutic rapport building, and involving regular exposure to emotionally complex situations. The findings suggest that the CCO role takes an emotional toll, adversely affecting mental health, and potentially increasing sickness rates and reducing quality of support to offenders. Therefore, greater consideration should be afforded to systematic supports for CCOs, potentially through peer support assuming familiarity with roles, and their inherent complexities.

Yet whilst burnout is privileged in research reviewed herein, and can capture the cumulative impacts of work as a CCO, the relative paucity of papers examining secondary trauma may reflect a more limited awareness of the traumatogenic exposure inherent in the work. In the one study to explicitly investigate prevalence of secondary trauma (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016), CCOs were found to report greater secondary trauma than did residential officers. Significant levels of secondary trauma are reported in other legal professionals (James, Citation2020), police (Brady, Citation2017) and social workers (Bride, Citation2007), and are associated with reduced work performance and higher rates of absenteeism (Ludick & Figley, Citation2017), and interventions are now advanced to tackle this distress (James, Citation2020). Thus further research seems warranted to assess whether CCOs are as vulnerable to this form of distress as similar professional groups, and develop strategies to mitigate, and retain staff and their expertise.

Synthesis of studies in this review revealed predictors across personal, organisational and role-based domains. Of those investigating burnout, nine reported personal variables including age and gender (Gayman & Bradley, Citation2013; Jin et al., Citation2018; Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2017). Fewer papers, eight in total, investigated organisational variables, concentrating narrowly on hours of contact, caseloads and years in role. The three papers investigating alternative forms of WRD also reported predictive factors across personal and organisational-based domains, demonstrating that attachment style and previous trauma history were predictive of VT (Merhav et al., Citation2018), whilst caseload size and type significantly predicted secondary trauma (Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2016) and CF (Lewis et al., Citation2013), respectively. Across all studies there was an absence of exploration into organisational factors known to impact on levels of WRD amongst other professions, such as workplace and co-worker support (Hensel et al., Citation2015; A. Miller et al., Citation2017). The findings suggest that future research should examine organisational predictive factors recognised in other professions (McFadden et al., Citation2015), and promote organisational strategies to enhance resilience rather than taking a solely individual narrative, potentially blaming and shaming for staff. Increased focus on the sustained challenges for CCOs may promote their organisational value, particularly during times of austerity with limited resources and a lack of psychological safety: factors associated with increasing WRD, as reported in similar professions (Alarcon, Citation2011; Grootegoed & Smith, Citation2018).

That studies differed in extent of distress reported and predictive factors may be attributed to diversity in how studies conceived and measured WRD. Even when studies utilised the same construct, notably burnout in 14 studies, they applied them differently. Some studies combined scores of frequency and intensity from the MBI across the three dimensions of burnout, rather than keeping them separate, likely contributing to disparities in extent of burnout reported. Additionally, Jin et al. (Citation2018) used a modified version of the MBI measure in which a single scale of burnout was calculated rather than three separate scales, despite recommendation that they are not combined (Panagioti et al., Citation2017).

Implications

Synthesised findings across the majority of studies indicate that CCOs experience burnout as a result of their work, at levels similar to those of other professionals working in criminal justice settings. In the very few studies that examined trauma responses, levels of secondary trauma were elevated, and indicate a need to examine not only the extent and manifestations of trauma-presenting WRD, but strategies and processes to identify and manage distress, at both individual and organisational levels, as well as to build resilience.

Findings in this review highlighted predictive organisational factors for burnout, and interventions to mitigate WRD should address these to complement those targeting the CCOs individually. Organisational structures should be made aware of the detrimental impact of excessive contact hours and large caseloads to direct sufficient available work resources. Furthermore, as role conflict was frequently cited as a predictive factor, organisations should be advised to consider the impact of the range of roles that CCOs have to fulfil. Clinical interventions at an organisational level could involve psychoeducation for all staff regarding the impact of chronic work distress with the aim of breaking down cultural barriers and attitudes towards mental health difficulties. Organisational approaches to wellbeing are advised, perhaps adopting employee assistance programmes, designed to support staff to manage difficulties that may impact on work, or similar to the Blue Light Wellbeing Framework (Coleman et al., Citation2018) applied nationally in UK police organisations, promoting regular organisational self-assessments.

Strengths and limitations

The present review was rigorously systematic in its approach and offers an up-to-date synthesis reporting on extent of WRD amongst CCOs. However, the findings of the review were limited to articles reported in English, with most papers specific to service delivery in Westernised countries, particularly the USA. Community corrections systems vary across countries and cultures, limiting the generalisability of the findings. Most noticeably, not one study included a sample from the UK, indicating a clear need for future research to address this gap.

There were various methodological frailties evident. All designs were cross-sectional, precluding establishing firm conclusions regarding causality (both independent and dependent variables were assessed at the same time, giving no evidence of a temporal relationship between them; Bowen & Wiersema, Citation1999), and longitudinal designs are needed to explore causal relationships further. All 19 included studies utilised self-report data, which are prone to bias and can increase the risk of overstated associations between factors (Theorell & Hasselhorn, Citation2005). Furthermore, papers were excluded from this review investigating PTSD and other forms of direct traumatisation, given that the focus was to explore inadvertent WRD that is not anticipated in the job role and therefore is potentially unacknowledged as a form of risk to wellbeing at work. However, it can be difficult to distinguish between responses to primary and secondary trauma, and all but one paper (Merhav et al., Citation2018) did not consider participants’ own trauma histories during investigations; it is therefore possible that findings were influenced by participants’ experiences of direct trauma. It is recommended that a review evaluates the literature concerning direct trauma in CCOs, to increase greater awareness in this area.

Study quality varied; whilst seven papers met the criteria threshold to be considered high quality, the majority were at best moderate with common flaws evident. Only more recent studies attempted to address or define characteristics of non-responders (Jin et al., Citation2018; Rhineberger-Dunn et al., Citation2017), perhaps reflecting a key difficulty with cross-sectional designs and opportunistic sampling. Non-responders may have had higher WRD and felt unable to engage in the study as a result of distress. Future research could address this through requesting organisations to provide basic characteristics of all employees to aid the consideration of non-response bias. Furthermore, sample size was only justified in two studies (Allard et al., Citation2003; Jin et al., Citation2018), whilst none reported power analysis or effect sizes. Further research in this area should address this issue by completing a priori calculations and ensuring these are reported, to enable transparency of methodology.

Conclusions

The systematic review of WRD identified evidence of mild to moderate levels of burnout amongst CCOs, akin to those in other professions within law enforcement. A number of predictive factors were found for this population ranging across personal, organisational and role-based domains. The review also revealed circumscribed evidence of elevated secondary trauma comparable to that in similar professions. This warrants further research on vicariously transmitted distress for these staff groups, given the sustained engagement with vulnerable clients. Given predictors of WRD in both individual and organisational domains, clinical interventions can target both, with regard to identification of distress and interventions to mitigate.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interests

Jessica Page has declared no conflicts of interest

Noelle Robertson has declared no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Adams, R. E., Figley, C. R., & Boscarino, J. A. (2008). The compassion fatigue scale: Its use with social workers following urban disaster. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(3), 238–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507310190

- Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

- Allard, T. J., Wortley, R. K., & Stewart, A. L. (2003). Role conflict in community corrections. Psychology, Crime and Law, 9(3), 279–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316031000093414

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

- Anson, R. H., & Bloom, M. E. (1988). Police stress in an occupational context. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 16(4), 229–235.

- Beck, C. T. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress in nurses: A systematic review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 25(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2010.05.005

- Bowen, H. P., & Wiersema, M. F. (1999). Matching method to paradigm in strategy research: Limitations of cross‐sectional analysis and some methodological alternatives. Strategic Management Journal, 20(7), 625–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199907)20:7<625::AID-SMJ45>3.0.CO;2-V

- Brady, P. Q. (2017). Crimes against caring: Exploring the risk of secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among child exploitation investigators. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 32(4), 305–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-016-9223-8

- Branson, D. C. (2019). Vicarious trauma, themes in research, and terminology: A review of literature. Traumatology, 25(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000161

- Bride, B. E. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.63

- Bride, B. E., Robinson, M. M., Yegidis, B., & Figley, C. R. (2004). Development and validation of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731503254106

- Brooks, S. K., Dunn, R., Amlôt, R., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. (2016). Social and occupational factors associated with psychological distress and disorder among disaster responders: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 4(1), 18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0120-9

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. Author.

- Cocker, F., & Joss, N. (2016). Compassion fatigue among healthcare, emergency and community service workers: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(6), 618. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060618

- Coleman, R., Kirby, S., Birdsall, N., Cox, C., & Boulton, L. (2018). Wellbeing in policing: Blue light wellbeing framework. The University of Lancashire and Lancashire Constabulary. https://oscarkilo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BLWF-Interim-Report-1.pdf

- Dir, A. L., Saldana, L., Chapman, J. E., & Aalsma, M. C. (2019). Burnout and mental health stigma among juvenile probation officers: The moderating effect of participatory atmosphere. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(2), 167–174.

- diZerega, M., & Verdone, J. (2011). Setting an agenda for family-focused justice reform. Vera Institute of Justice.

- Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Elwood, L. S., Mott, J., Lohr, J. M., & Galovski, T. E. (2011). Secondary trauma symptoms in clinicians: A critical review of the construct, specificity, and implications for trauma-focused treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.004

- Fernando, A. T., & Consedine, N. S. (2014). Beyond compassion fatigue: The transactional model of physician compassion. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.014

- Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel.

- Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10090

- Figley, C. R., & Stamm, B. H. (1996). Psychometric review of the compassion fatigue self test. In B. H. Stamm (Ed.), Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Sidran Press.

- Finney, C., Stergiopoulos, E., Hensel, J., Bonato, S., & Dewa, C. S. (2013). Organizational stressors associated with job stress and burnout in correctional officers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-82

- Gayman, M. D., & Bradley, M. S. (2013). Organizational climate, work stress, and depressive symptoms among probation and parole officers. Criminal Justice Studies, 26(3), 326–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2012.742436

- Gayman, M. D., Powell, N. K., & Bradley, M. S. (2018). Probation/parole officer psychological well-being: The impact of supervising persons with mental health needs. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-017-9422-6

- Glisson, C., & Durick, M. (1988). Predictors of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in human service organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392855

- Glisson, C., & Hemmelgarn, A. (1998). The effects of organizational climate and interorganizational coordination on the quality and outcomes of children’s service systems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(5), 401–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00005-2

- Glisson, C., & James, L. R. (2002). The cross‐level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 767–794. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.162

- Greenland, S., & O’Rourke, K. (2001). On the bias produced by quality scores in meta‐analysis, and a hierarchical view of proposed solutions. Biostatistics, 2(4), 463–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/2.4.463

- Greinacher, A., Derezza-Greeven, C., Herzog, W., & Nikendei, C. (2019). Secondary traumatization in first responders: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1562840–1562821. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1562840

- Grootegoed, E., & Smith, M. (2018). The emotional labour of austerity: How social workers reflect and work on their feelings towards reducing support to needy children and families. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(7), 1929–1947. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx151

- Halsey, M. (2018). Child victims as adult offenders: Foregrounding the criminogenic effects of (unresolved) trauma and loss. The British Journal of Criminology, 58(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw097

- Henderson, S. E., Brady, E. M., & Robertson, N. (2019). Associations between social jetlag and mental health in young people: A systematic review. Chronobiology International, 36(10), 1316–1333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2019.1636813

- Hensel, J. M., Ruiz, C., Finney, C., & Dewa, C. S. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21998

- Holgate, A. M., & Clegg, I. J. (1991). The path to probation officer burnout: New dogs, old tricks. Journal of Criminal Justice, 19(4), 325–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(91)90030-Y

- Holloway, E. D., Mootoo, C., Kırbıyık, U., & Aalsma, M. C. (2019). The role of education, participation in departmental decisions, and burnout in social support and consulting networks in juvenile probation departments. European Journal of Probation, 11(2), 72–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220319868023

- Hsieh, M. L., Hafoka, M., Woo, Y., van Wormer, J., Stohr, M. K., & Hemmens, C. (2015). Probation officer roles: A statutory analysis. Federal Probation, 79(3), 20–37.

- Huggard, P., Law, J., & Newcombe, D. (2017). A systematic review exploring the presence of vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress in alcohol and other drug clinicians. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 21(2), 65–72.

- James, C. (2020). Towards trauma-informed legal practice: A review. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law : An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(2), 275–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1719377

- Jin, X., Sun, I. Y., Jiang, S., Wang, Y., & Wen, S. (2018). The impact of job characteristics on burnout among Chinese correctional workers. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(2), 551–570. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16648419

- Jo, I., Lee, S., Sung, G., Kim, M., Lee, S., Park, J., & Lee, K. (2018). Relationship between burnout and PTSD symptoms in firefighters: The moderating effects of a sense of calling to firefighting. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 91(1), 117–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-017-1263-6

- Jüni, P., Witschi, A., Bloch, R., & Egger, M. (1999). The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA, 282(11), 1054–1060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.11.1054

- Kim, Y., Lee, E., & Lee, H. (2020). Correction: Association between workplace bullying and burnout, professional quality of life, and turnover intention among clinical nurses. PLoS One, 15(1), e0228124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228124

- Kirk, D. S., & Hardy, M. (2014). The acute and enduring consequences of exposure to violence on youth mental health and aggression. Justice Quarterly, 31(3), 539–567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.737471

- Kiss, R., Schedler, S., & Muehlbauer, T. (2018). Associations between types of balance performance in healthy individuals across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01366

- Ledoux, K. (2015). Understanding compassion fatigue: Understanding compassion. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(9), 2041–2050. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12686

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2004). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In P. Perrewe & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well being: Vol. 3. Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (pp. 91–134). Press/Elsevier.

- Leiter, M. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1996). Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety Stress, and Coping, 9(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809608249404

- Levin, A. P., Albert, L., Besser, A., Smith, D., Zelenski, A., Rosenkranz, S., & Neria, Y. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress in attorneys and their administrative support staff working with trauma-exposed clients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(12), 946–955. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182392c26

- Lewis, K. R., Lewis, L. S., & Garby, T. M. (2013). Surviving the trenches: The personal impact of the job on probation officers. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-012-9165-3

- Lindquist, C. A., & Whitehead, J. T. (1986). Correctional officers as parole officers: An examination of a community supervision sanction. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 13(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854886013002005

- Lonergan, M., Leclerc, M. È., Descamps, M., Pigeon, S., & Brunet, A. (2016). Prevalence and severity of trauma and stressor-related symptoms among jurors: A review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 47, 51–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.07.003

- Ludick, M., & Figley, C. R. (2017). Toward a mechanism for secondary trauma induction and reduction: Reimagining a theory of secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology, 23(1), 112–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000096

- Lustig, S., Delucchi, K., Tennakoon, L., Kaul, B., Marks, D. L., & Slavin, D. (2008). Burnout and stress among United States immigration judges. Benders Immigration Bulletin, 13, 22–30.

- Maguire, G., & Byrne, M. K. (2017). The law is not as blind as it seems: Relative rates of vicarious trauma among lawyers and mental health professionals. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1220037

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The Maslach burnout inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- McFadden, P., Campbell, A., & Taylor, B. (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1546–1563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct210

- Merhav, I., Lawental, M., & Peled-Avram, M. (2018). Vicarious traumatisation: Working with clients of probation services. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(8), 2215–2234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx162

- Miller, A., Unruh, L., Wharton, T., Liu, X. A., & Zhang, N. J. (2017). The relationship between perceived organizational support, perceived coworker support, debriefing and professional quality of life in Florida law enforcement officers. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 19(3), 129–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355717717995

- Miller, J. (2015). Contemporary modes of probation officer supervision: The triumph of the “synthetic” officer? Justice Quarterly, 32(2), 314–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2013.770546

- Ministry of Justice. (2019a). Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) annual staff equalities report 2018/19. Author.

- Ministry of Justice. (2019b). Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) workforce statistics bulletin, as at 30 June 2019. Author.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. British Medical Journal, 151(4), 264–269.

- Morse, G., Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., Monroe-DeVita, M., & Pfahler, C. (2012). Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 39(5), 341–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0352-1

- Murphy. (2020). Absence rates and costs survey 2020. London: XpertHR. Retrieved 22 January 2021 from https://www.xperthr.co.uk/survey-analysis/absence-rates-and-costs-survey-2020/165503

- Newell, J. M., & MacNeil, G. A. (2010). Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(2), 57–68.

- Ohlin, L. E., Piven, H., & Pappenfort, D. M. (1956). Major dilemmas of the social worker in probation and parole. National Probation & Parole Association Journal, 3, 211–225.

- Panagioti, M., Panagopoulou, E., Bower, P., Lewith, G., Kontopantelis, E., Chew-Graham, C., Dawson, S., van Marwijk, H., Geraghty, K., & Esmail, A. (2017). Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674

- Paris, M., & Hoge, M. A. (2010). Burnout in the mental health workforce: A review. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37(4), 519–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-009-9202-2

- Pearlman, L. A. (2003). Trauma and Attachment Belief Scale (TABS). Western Psychological Services.

- Pearlman, L. A., & Mac Ian, P. S. (1995). Vicarious traumatization: An empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26(6), 558–565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.26.6.558

- Pines, A., & Aronson, E. (1988). Career burnout: Causes and cures. Free Press.

- Raynor, P., & Vanstone, M. (2016). Moving away from social work and half way back again: New research on skills in probation. British Journal of Social Work, 46(4), 1131–1147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv008

- Regehr, C., Goldberg, G., & Hughes, J. (2002). Exposure to human tragedy, empathy, and trauma in ambulance paramedics. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.72.4.505

- Rhineberger-Dunn, G., Mack, K. Y., & Baker, K. M. (2016). Secondary trauma among community corrections staff: An exploratory study. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 55(5), 293–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2016.1181132

- Rhineberger-Dunn, G., Mack, K. Y., & Baker, K. M. (2017). Comparing demographic factors, background characteristics, and workplace perceptions as predictors of burnout among community corrections officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(2), 205–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816666583

- Richardson, K. M., & Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69

- Sabin-Farrell, R., & Turpin, G. (2003). Vicarious traumatization: Implications for the mental health of health workers? Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 449–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00030-8

- Sage, C. A., Brooks, S. K., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Factors associated with Type II trauma in occupational groups working with traumatised children: A systematic review. Journal of Mental Health, 27(5), 457–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370630

- Sanderson, S., Tatt, I. D., & Higgins, J. (2007). Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(3), 666–676. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym018

- Santos, C. M. D. C., Pimenta, C. A. D. M., & Nobre, M. R. C. (2007). The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 15(3), 508–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023

- Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey (MBI-GS). In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), MBI Manual. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Peeters, M. C. (2000). Job stress and burnout among correctional officers: A literature review. International Journal of Stress Management, 7(1), 19–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009514731657

- Schoth, D. E., Blankenburg, M., Wager, J., Broadbent, P., Zhang, J., Zernikow, B., & Liossi, C. (2019). Association between quantitative sensory testing and pain or disability in paediatric chronic pain: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(10), e031861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031861

- Sherwood, L., Hegarty, S., Vallières, F., Hyland, P., Murphy, J., Fitzgerald, G., & Reid, T. (2019). Identifying the key risk factors for adverse psychological outcomes among police officers: A systematic literature review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(5), 688–700. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22431

- Sinclair, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Venturato, L., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J., & Smith-MacDonald, L. (2017). Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 69, 9–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003

- Slate, R. N., Johnson, W., & Wells, T. L. (2000). Probation officer stress: Is there an organizational solution? Federal Probation, 64(1), 56–59.

- Slate, R. N., Wells, T. L., & Johnson, W. W. (2003). Opening the manager’s door: State probation officer stress and perceptions of participation in workplace decision making. Crime & Delinquency, 49(4), 519–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128703256526

- Sorenson, C., Bolick, B., Wright, K., & Hamilton, R. (2016). Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A review of current literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 48(5), 456–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12229

- Spiess, G. J., & Johnson, E. H. (1980). Role conflict and role ambiguity in probation: Structural sources and consequences in West Germany. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 4(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.1980.9688704

- Suleiman-Martos, N., Albendín-García, L., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Vargas-Román, K., Ramirez-Baena, L., Ortega-Campos, E., & De La Fuente-Solana, E. I. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of burnout in midwives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020641

- Theorell, T., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2005). On cross-sectional questionnaire studies of relationships between psychosocial conditions at work and health-are they reliable? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 78(7), 517–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-005-0618-6

- Turgoose, D., & Maddox, L. (2017). Predictors of compassion fatigue in mental health professionals: A narrative review. Traumatology, 23(2), 172–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000116

- White, L. M., Aalsma, M. C., Holloway, E. D., Adams, E. L., & Salyers, M. P. (2015). Job-related burnout among juvenile probation officers: Implications for mental health stigma and competency. Psychological Services, 12(3), 291–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000031

- Whitehead, J., & Lindquist, C. (1985). Job stress and burnout among probation/parole officers: Perceptions and causal factors. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 29(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X8502900204

- Whitehead, J. T. (1985). Job burnout in probation and parole: Its extent and intervention implications. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 12(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854885012001007

- Whitehead, J. T. (1986a). Gender differences in probation: A case of no differences. Justice Quarterly, 3(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07418828600088791

- Whitehead, J. T. (1986b). Job burnout and job satisfaction among probation managers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 14(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(86)90024-3

- Whitehead, J. T. (1987). Probation officer job burnout: A test of two theories. Journal of Criminal Justice, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(87)90074-2

- Will, J. L., Loper, A. B., & Jackson, S. L. (2016). Second-generation prisoners and the transmission of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(1), 100–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555127

- Williams, A. M., Reed, B., Self, M. M., Robiner, W. N., & Ward, W. L. (2019). Psychologists’ practices, stressors, and wellness in academic health centers. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 27(4), 818–829. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-019-09678-4

- Wilson, H. W., Berent, E., Donenberg, G. R., Emerson, E. M., Rodriguez, E. M., & Sandesara, A. (2013). Trauma history and PTSD symptoms in juvenile offenders on probation. Victims & Offenders, 8(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2013.835296

- Wong, J. N., McAuley, E., & Trinh, L. (2018). Physical activity programming and counseling preferences among cancer survivors: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0680-6

- Zeng, X., Zhang, Y., Kwong, J. S., Zhang, C., Li, S., Sun, F., Niu, Y., & Du, L. (2015). The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: A systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 8(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12141