Abstract

Medical and legal professionals are increasingly involved in probate disputes in which the validity of a will due to a lack of testamentary capacity in older adults is frequently challenged. The legal test for testamentary capacity under common-law jurisdiction was established in the famous case of Banks v Goodfellow (1870). The High Court of Hong Kong recently issued new practice guidance for legal professionals on the preparation of a will for older adults. This paper discusses the dilemmas and competing issues among different parties on this medicolegal interface based on recent literature and local examples. We recommend a risk-based pragmatic framework for legal and medical professionals to minimise potential disputes in testamentary capacity assessment.

Introduction

Testamentary capacity is a specific legal construct and legal determination that represents the mental capacity required for a person to execute a will.Footnote1 Testamentary capacity is unique among various mental capacities, such as dealing with financial affairs, giving a gift, litigating, entering into a contract, voting and giving consent.Footnote2 Unlike other forensic examinations, the legal standard for establishing testamentary capacity requires a relatively low threshold to respect the testator/testatrix’s autonomy.Footnote3 The overriding legal test for testamentary capacity under common law remains enunciated in the well-known Banks v Goodfellow (1870) case, which has withstood the test of time.Footnote4 On the other hand, courts have to presume an adult to have mental capacity unless proven otherwise. Simultaneously, they must balance legal rights and the risk of abuse of vulnerable adults.Footnote5 Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) upholds these principles and entered into force for China, including Hong Kong, in August 2008.Footnote6

CRPD Article 12 – Equal recognition before the law

States parties reaffirm that persons with disabilities have the right to recognition everywhere as persons before the law.

States parties shall recognize that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life.

States parties shall take appropriate measures to provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity.

States parties shall ensure that all measures that relate to the exercise of legal capacity provide for appropriate and effective safeguards to prevent abuse in accordance with international human rights law. Such safeguards shall ensure that measures relating to the exercise of legal capacity respect the rights, will and preferences of the person, are free of conflict of interest and undue influence, are proportional and tailored to the person’s circumstances, apply for the shortest time possible, and are subject to regular review by a competent, independent and impartial authority or judicial body. The safeguards shall be proportional to the degree to which such measures affect the person’s rights and interests.

Subject to the provisions of this article, States parties shall take all appropriate and effective measures to ensure the equal right of persons with disabilities to own or inherit property, to control their own financial affairs, and to have equal access to bank loans, mortgages, and other forms of financial credit, and shall ensure that persons with disabilities are not arbitrarily deprived of their property.Footnote7

Legal framework in Hong Kong

As a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR is subject to the Basic Law – the Commonwealth law system’s continuity. Article 8 of the Basic Law of Hong Kong states the following: ‘The laws previously in force in Hong Kong, that is, the common law, rules of equity, ordinances, subordinate legislation, and customary law, shall be maintained, except for any that contravene this Law, and subject to any amendment by the legislature of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’. Hong Kong SAR maintains the legal structure of common law supplemented by local legislation.Footnote8 The common ordinances for probate law and practice are the Probate and Administration Ordinance, Wills Ordinance and Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependents) Ordinance.Footnote9 The Wills Ordinance governs any will written in Chinese or English. The Probate Registry of the High Court is the hub for all related applications and provides the legal right to deal with the deceased’s estate. When the deceased has an estate in both mainland China and Hong Kong SAR (which is increasingly common), the estate in the mainland that is included in the will is governed by the Law of Succession of the People’s Republic of China. Local lawyers with the qualification of ‘China-appointed attesting officer’ are among the notary agencies. The content and spirit of China’s relevant legislation are similar to those in other countries.Footnote10

Legal tests in the probate court

Like many Western countries, an adult’s (aged 18 years or older) testamentary capacity is, until proven otherwise, presumed to be intact in Hong Kong SAR. The legal principles used in the probate court emphasise that the proponent of the will has the persuasive burden of proof in regard to a balance of probabilities of the following:

that there was due execution of the will;

that the testator was of testamentary capacity; and,

that the testator knew and approved the content of the will.Footnote11

In Hong Kong SAR, the most commonly cited court case is the record-breaking series of hearings involving the families and the renowned multi-millionaire estate of Nina Kung.Footnote12 Additionally, judges and lawyers in court have been referring to ‘Assessment of Mental Capacity: A Practical Guide for Doctors and Lawyers’, published by the British Medical Association and the Law Society, as well as the relevant paragraphs in legal textbooks.Footnote13 In short, the legal test for testamentary capacity in Hong Kong SAR is based on common law and the Banks v GoodfellowFootnote14 case with reference to the totality of evidence such as medical evidence (which will be elaborated on in the literature update). The learned judges have concluded the following:

‘In assessing testamentary capacity, the Court will consider the rationality, but not morality, of a testator’s disposition under the will as a relevant factor. … Rationality must be evaluated together with all the available evidence, factual and medical’.Footnote15

Dilemmas in Chinese families

It has been suggested that myriad individual, familial, cultural and socioeconomic factors increase the risk of probate litigation in Hong Kong SAR.Footnote16 The local population’s life expectancy has become the longest in the world.Footnote17 The proportion of older adults aged 65 years or older of the total population is predicted to rise from 16.6% in 2016 to 31.1% by 2036, and more than 90% of the Hong Kong SAR population is Chinese.Footnote18 The wealth and property of baby boomers and the subsequent cohorts of older adults in China are substantial. For example, the house of an older adult is said to be a ‘house of gold’ in the ever-rising property market, and Chinese older adults tend to depend on their children for financial decisions under a filial culture.Footnote19

Historical reasons have also played a role. There were several waves of Chinese migration from mainland China to Hong Kong related to the Sino-Japanese war and civil war in mainland in the first half of the nineteenth century. Hong Kong as a British colony at that time, the border was highly restricted and people in Hong Kong had limited communication with their relatives in mainland China until the border was opened in the late nineteenth century. The self-made testator was married through traditional rites in mainland China before the border was closed and ‘remarried’ under the law after he came to Hong Kong. Both marriages are recognised by the probate court in Hong Kong SAR. The testator’s spouses, children and grandchildren may end up challenging the unfavourable wills.Footnote20 A common finding in court hearings is that older adults (and their relatives) often lack basic knowledge and underestimate the risk of disputes in will-making. One of the children may accompany the older adult to sign a prepared will with or without legal assistance.Footnote21 The long-term conflicts among the testator’s families become heightened and unearthed, and legal and medical professionals are often called to testify during lengthy probate hearings.Footnote22

Honourable Judge Poon, Judge of the Court of First Instance, in Chiu Man Fu and others v Chiu Chung Kwan Ying, 2012, remarked on the dilemmas, sufferings and damage to the families in probate disputes in the first paragraph of his judgement:

This is a sad case. This (It) demonstrates once again that contentious probate proceedings, where the drama of the family rifts unfolds with all the ill-feelings, resentment and animosity between the protagonists climaxing on public display, are unavoidably destructive to (of) what is left of the testator’s family. Win or lose, the family will most likely be torn further apart irretrievably.

Challenges for legal and medical professionals

The number of legal challenges to the validity of wills, especially on the grounds of lack of testamentary capacity, has been increasing over the last two decades.Footnote23 Dementia has become a popular ground for disputes, partly because of its high prevalence rate of up to 10% in local older adults aged 70 years or over.Footnote24 It is apparent that the evolution of medical science in understanding mental capacities, the high prevalence of dementia and recognition of Article 12 of the CRPD give room for probate disputes as the legal right of older adults with cognitive impairment is respected, and the older adults, their relatives and even some local professionals may regard dementia as part of normal ageing.Footnote25

Due to different backgrounds, training, terminology and practice between legal and medical practitioners, local professionals who ‘speak different languages’ and sometimes lack mutual communication face unprecedented challenges when they come together in handling this multidimensional and interlocking financial issue of will-making for older adults.Footnote26 In clinical practice, it is not uncommon for older adults or their children, who know little about will-making, to be instructed by the staff of a legal firm to obtain a ‘medical certificate’ before making the first appointment with their lawyer. Additionally, people with conflicts of interest regarding wills tend to provide limited information and cherry-pick professionals when the wills are being executed.Footnote27 Learned judges in the High Court of Hong Kong have made several recommendations, including that

‘the local law schools and the Law Society [should] pay particular attention to their practice and procedure courses on the solicitor’s role in the preparation and execution of a will’

for older adults.Footnote28

Role of legal professionals

Internationally, it is the lawyer representing an older adult who decides whether the client has the capacity to give instructions, allows disclosure of confidential information and executes the will under the local jurisdiction.Footnote29 Legal professionals have a duty to uphold a client’s rights, determine legal capacity and arrange appropriate measures to assist their older clients with disability

‘to own or inherit property, to control their own financial affairs, and to have equal access to bank loans, mortgages, and other forms of financial credit’

under Article 12(5) of the CRPD.Footnote30 This implies that legal professionals act as the ‘gatekeepers’ for older clients who may show signs of impaired capacity. In the case of doubt or complexity, clients should be referred for medical examination and mental capacity assessment.

Good practice for solicitors in Hong Kong SAR

The Choy Po Chun caseFootnote31 highlighted good practice for legal professionals taking instructions for older adults in will-making. In this case, the Justice of Appeal stated the following:

The solicitor should not regard the task as merely a formal act. Although in Hong Kong instructions to prepare a will may often be given by the adult children of the testator who is elderly and not in good health, it behoves the solicitor who wishes to discharge his duty properly to meet the testator personally for the purpose of taking instructions or confirming the instructions. He should do this well before the day appointed for the execution of the will which by then is already prepared on the instruction given by someone other than the testator.

The enquiries made by the solicitor at such an appointment should, subject to the circumstances of each case, include the following, namely,

the age of the testator,

his health condition,

whether he has a surviving spouse,

the number of children and grandchildren he has,

whether there is someone other than his immediate family member dependent on him for support,

the beneficiaries he would like to provide for in his will,

his properties,

whether he has made a previous will,

whether he understands (that) the new will will revoke the previous will,

whether he understands the difference between the new and the previous will.

The list is, of course, not exhaustive, and the extent of the inquiry will depend on the circumstances of the case.

These procedures and legal requirements are also relevant to various medical professionals in Hong Kong SAR, including specialists and general practitioners who are entitled to carry out testamentary capacity assessments.Footnote32 Both legal and medical professionals should keep up with advances in the field, carry out a proper examination and record the detailed findings for potential probate dispute months or years later.Footnote33

Role of medical professionals

Like in other ageing societies, local older adults who have accumulated wealth also develop health and family problems during their lives.Footnote34 Medical professionals are increasingly involved in the preparation of wills because of the so-called Golden Rule formulated by the judge in Kenward v Adams:Footnote35

‘in the case of an aged testator or a testator who has suffered from serious illness, there is one golden rule which should always be observed, however straight-forward matters may appear, and however difficult or tactless it may be to suggest that precautions be taken. The making of a will by such a testator ought to be witnessed or approved by a medical practitioner who satisfies himself of the capacity and understanding of the testator, and records and preserves his examinations and findings’.

Notably, while a court will rely on the quality of medical evidence, a person’s testamentary capacity is ultimately decided by the court.Footnote36

Case example

A young native couple moved to England and earned their living by running a Chinese takeaway shop. They returned to Hong Kong SAR permanently after retirement. The couple had agreed on how to distribute their current and future properties before returning to Hong Kong SAR because their land and village houses had been purchased for redevelopment by a local property group in Hong Kong SAR. The wife passed away in 2002, and her will settled part of their properties, compensated by the villagers’ property group. The husband executed an English will in 2002 and 2004, in which his eldest son was the sole beneficiary. The husband suffered from terminal cancer and died at 81 years of age at a general hospital in late November 2008. The husband executed a Chinese will at the hospital eight days before his death. The will was changed from the previous family agreement and named one of their grandchildren, who took care of the husband in his last few years of life, as the major beneficiary.Footnote37

Testamentary capacity is presumed

The man’s eldest son challenged the last will, and a series of probate hearings began, lasting from mid-2009 until early 2015. The physician in charge at the general hospital provided medical evidence by stating that the testator was orientated to time, place and person after a routine medical check. After reviewing the medical records, the physician testified that

‘there was no impairment whatever of the mind of the deceased’ and certified that ‘the deceased was fully conscious, mentally sound and stable to arrange and decide on his financial affairs’.Footnote38

Both parties invited a specialist in psychiatry to give expert opinions on the testator’s testamentary capacity during the execution of his last will in 2008. The judge held that with the acceptance of the evidence that had included the expert opinions and referring to Sutton v Sadler,Footnote39 the 2008 will was duly executed and rational on its face.

Deathbed will

The eldest son understandably did not accept the ruling and appealed in 2014 through his lawyers. The counterargument was related to traditional Chinese values regarding family order and male descendants, as well as the fact that a deathbed will seemed to be operating in this case. With the expert opinions, the eldest son’s lawyer also challenged the physician’s evidence that a ‘task-specific mental capacity assessment’ had not been performed and did not fulfil all the requirements of Banks v Goodfellow.Footnote40 The Appeal Court did not accept counterarguments because the trial judge had considered the arguments in previous hearings.Footnote41

Case discussion

This example illustrates the typical life history of self-made Chinese couples. This includes their cumulative wealth on land properties and the dilemmas of the family members who hold traditional Chinese family values – that the eldest son is the expected next patriarch and the values discussed above – against the testamentary autonomy and freedom of the testator despite there being a drastic change in the beneficiary in the last will. The learned judges placed more weight on the presumption of testamentary capacity and upheld the legal rights and capacity of older adults with disabilities under Article 12 of the CRPD and his representing lawyer’s observation and experience during the execution of the will in the hospital.Footnote42 This case also illustrates that the learned judges in Hong Kong SAR have been applying not only the legal principle of Banks v GoodfellowFootnote43 to determine testamentary capacity, but also the available totality of the evidence. The need for further training for legal and medical professionals working in this area has been emphasised in the court and medical literature.Footnote44

Literature update

Autonomy as a human right

Autonomy is respected at every level in modern society. For testamentary capacity, the important principle presented by Lord Chief Justice Cockburn in Banks v GoodfellowFootnote45 was that unless a mental impairment (‘disorder of mind’) directly affected the testator’s mind concerning the particular will, it was not relevant to testamentary capacity. It is the nature and degree of the disordered thoughts that matter.Footnote46

According to General Comment No 1 (2014) on the CRPD,Footnote47 legal and mental capacities are distinct concepts. Legal capacity is divided into legal standing and legal agencies. Legal standing is the ability to hold rights and duties, and legal agency is exercising these rights and duties. Mental capacity refers to the decision-making ability of a person, which varies from one person to another and depends on different factors for a given person. Under Article 12 of the CRPD, perceived or actual deficits in mental capacity must not be used as justification for denying legal capacity. There is a paradigm shift from substitute decision-making to supported decision-making in Article 12 of the CRPD.Footnote48

The World Psychiatric Association and International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) stated that older adults with mental disabilities should maintain their right to make decisions and should be supported through appropriate measures in the decision-making process.Footnote49 Furthermore, the IPA Task Force on Mental Capacity advocated promoting the autonomy and freedom of older adults with cognitive or mental impairment.Footnote50 In a recent provincial population-based survey in South Korea, the public supported older adults’ autonomy with dementia and preferred medical examination by specialists to safeguard testamentary capacity before the execution of a will.Footnote51

Functional approach in mental capacity assessment

In contrast to legal capacity, which is driven by fact-finding, rationality and emphasis on understanding the nature and effect of a decision,Footnote52 the contemporary clinical construct of mental capacity (that is, medical capacity) is multidimensional and medicolegal.Footnote53 The assessment of mental capacities should not be confined to a clinical diagnosis but should be specific to time, situation, and task.Footnote54 The basic principles in all capacity assessments remain the same: older adults must demonstrate their cognitive capacity to understand specific and relevant information. They should show the ability to appreciate and reason based on the given information, make the decision and communicate the decision to the relevant people. These principles have been upheld by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in the United Kingdom and are adopted by most practitioners in the field.Footnote55 Shulman et al. suggested that the standard of mental capacity should vary proportionately with the complexity of the situation and the cognitive level (or emotional stability).Footnote56 For example, a man with mild dementia may be able to provide consent for simple surgical procedures. However, he may be incapable of making decisions regarding his health and welfare needs upon hospital discharge because of the complexity of the issues.Footnote57

Neuropsychiatric disorders

Great progress has been made in the development of medicine, particularly neuroscience in psychiatry, psychology, neurology and the law, during the twentieth century.Footnote58 In addition to the classic ‘insane delusions’ in Banks v Goodfellow,Footnote59 clinical experiences and studies have shown that mental disorders with cognitive, mood or psychotic symptoms can impair mental capacity to different degrees.Footnote60 Notably, cognitive deficits can impair a testator/testatrix’s testamentary capacity, especially for complex attention, memory, language and executive function.Footnote61 Consequently, the contemporary interpretation of delusions can be applied to mental or cognitive disorders as a form of neuropsychiatric disorder.

Dementia has become a major public health problem in ageing societies. Roked and Patel found that in testators with mild Alzheimer’s disease, the language function and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 20 to 26 predicted positive testamentary capacity accurately when compared to testators with moderate and severe Alzheimer’s disease.Footnote62 However, the MMSE score must be adjusted according to the educational and cultural backgrounds. Recent studies have shown that very early stages and certain subtypes of dementia may impair the testator/testatrix’s executive functions, impulse control and rational judgement formation.Footnote63 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is a better instrument for testing executive function than the MMSE.Footnote64 Clinical diagnosis and global cognitive tests serve as indicators of specific capacity assessment. Sullivan suggested that capacity assessment should include a two-stage process that taps into general cognitive abilities and specific knowledge or ability, sometimes divided into decisional and executional capacity.Footnote65

Undue influence

Undue influence is a distinct legal construct and, although there is no presumption of undue influence on testamentary dispositions, it has become a popular challenge in probate courts.Footnote66 Over the course of the last decade, an increasing number of articles have reviewed undue influence and testamentary capacity.Footnote67 In most jurisdictions, there must be an element of coercion, compulsion or restraint to affect the free/true wish of the testator, who must have the required testamentary capacity.Footnote68

Several risk factors, such as uneven cognitive deficits, dementia, sensory loss, multiple medical problems, drugs and social isolation, are common in older adults and may put them at risk of being influenced.Footnote69 Therefore, the role of medical professionals in identifying vulnerable older adults is crucial.Footnote70 Despite the practical difficulty, probate courts seem more likely to accept the presence of undue influence in cases of drug intoxication and serious physical or mental disorders which result in diminished mental capacity and require a lesser burden of proof when there is an association with fraud.Footnote71

Risk-based framework for testamentary capacity assessment

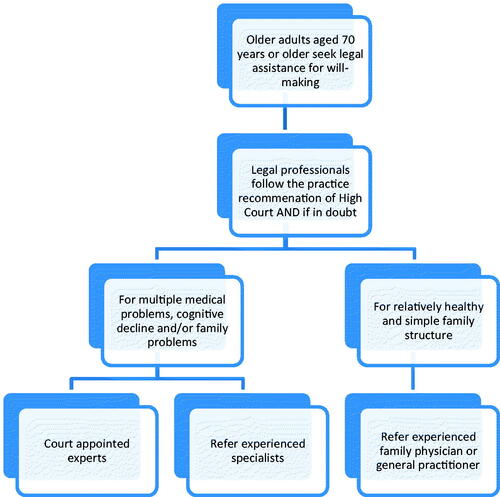

We recommend a risk-based framework for contemporary testamentary capacity assessment which follows the principles of CRPD, the Golden Rule and court recommendations for legal and medical professionals by division of labour. The framework is pragmatic in the current situation of Hong Kong SAR.Footnote72 In line with the high court’s recommendation, literature findings and experiences, the following framework and procedures can be used to safeguard older adults’ rights, screen for neuropsychiatric disorders and reduce the risk of financial abuse and potential legal disputes (). The procedures are pragmatic in relieving the practical difficulties faced by busy professionals. In short, advancing age, complicated family structure and physically weak or mentally ill testators raise the risk of disputes. A relatively young and healthy testator/testatrix may consult their usual family physician or general practitioner to assess testamentary capacity.Footnote73 On the other hand, the older testator/testatrix with chronic medical problems, cognitive decline or family disputes should always require appropriately qualified and experienced specialists for assessment. The practical guide for doctors and lawyers is a good reference.Footnote74 Medical professionals may rely on a representative lawyer, who should always check the facts and provide information on the legal test for capacity assessment. They should be careful not to take instructions in the presence of anyone who may benefit under the will before the medical examination.Footnote75 A neutral interpreter may be necessary when language or dialect is a barrier.

Figure 1. Pathway for legal professionals after taking instructions from older adults to execute a will.

We highlight the key elements of the framework for medical professionals because the relevant literature is limited.Footnote76

What to prepare

Medical professionals should be alert when there is an informal request to provide a memo on diagnosis and decisional capacity in an ordinary consultation. We recommend that the doctor always ask the patient or their relatives to make another appointment and obtain formal instructions from the representative lawyer. Written consent from the testator/testatrix for the testamentary capacity examination is highly recommended. The doctor should then review the medical notes, vital signs, investigation results and current medications of the testator/testatrix before the examination. The examination should be conducted in a supportive and nonthreatening environment, and the testator/testatrix should be interviewed alone to minimise undue influence. The doctor should provide assistive devices where necessary, such as a sensory aid or pen and paper, to maximise the testator/testatrix’s potential because of the principles in Article 12 of the CRPD and the fact that the presence of sensory loss, speech impairment or dialect can profoundly affect the perception of mental capacity.Footnote77

How to examine

The doctor shall allow social conversation and open questions to break the ice. With the testator/testatrix’s clinical history and medications in mind, clarification with the testator/testatrix is required for medical problems and treatment compliance. Doctors need to assess the effects of acquired neurological injuries such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, developmental disorders (such as intellectual disability and autistic spectrum disorder) and the effects of drugs and alcohol, which may cause different degrees of cognitive impairment in the testator/testatrix. The examination should include a cognitive screening test for possible undetected neurodegenerative disorders, such as early Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment. In case of doubt or inadequate information or if the testator/testatrix becomes tired, a follow-up examination with collateral information provided by a reliable informant may be necessary.Footnote78

A mental state examination should detect overt mental disorders, such as mood or psychotic disorders. The doctor must then look for specific components of the principles enunciated in Banks v Goodfellow to establish testamentary capacity.Footnote79 The limbs of the Banks v Goodfellow test are as follows:Footnote80

Capable of understanding the nature and effect of a will

Aware of the nature and extent of his/her estate in general

Knows the claims of those who might expect to benefit from the will (those included in and excluded from the will).

A common pitfall is when the representing lawyer does not provide clear instructions, does not check for any previous wills or does not provide an outline of the testator/testatrix’s estate for functional capacity assessment. The doctor also needs to determine whether the testator/testatrix has a mental, cognitive or physical disorder that may affect them in making testamentary dispositions. An older testator/testatrix with a severe mental disorder, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, may exclude potential beneficiaries under psychotic influence. It is preferable to write down the reason (ideally in their own words) why the testator/testatrix excludes a particular potential beneficiary from the will. The reason need not be wise, but it must not be affected by mental disorders. Making a referral to an experienced psychologist for neurocognitive testing can be an option, and the use of modern technology, such as voice or video recording, is increasingly common in complicated situations.Footnote81 All information should be kept confidential.

Jacoby and Steer summarise that the process of assessment should include the following steps:Footnote82

What else to look for

The doctor responsible for the testamentary capacity examination should observe the professional code of conduct and always act in the patient’s best interests. Older patients with diminished capacity are at a risk of abuse and financial exploitation. In the private sector, ‘doctor or lawyer shopping’ is not uncommon.Footnote83 A high-risk situation for probate disputes is a deathbed will, as illustrated by the case example and the article reviewed by the IPA taskforce on mental capacity.Footnote84 Hospitalised older adults may develop hypoactive, hyperactive or mixed delirium that temporarily disturbs their complex attention and cognitive functions and has arguable lucid intervals.Footnote85 We suggest that prior consent and arrangement with the testator/testatrix, their lawyer and the hospital are essential; otherwise, doctors may put themselves at risk of receiving complaints or being challenged in subsequent legal disputes.Footnote86 The risk-based framework can raise the quality of testamentary capacity assessments, reduce potential family disputes and expedite probate hearings, such as in the case example.

Conclusion

The ageing population is rapidly increasing worldwide. The number of physically frail and ‘mentally incapacitated’ older adults may increase sharply in the coming decades. Such individuals are at risk of being financially abused and unduly influenced during wealth transfer within disharmonious families. Professionals working with older adults, especially those in the medical and legal fields, should receive timely education and training for contemporaneous capacity assessment as required by law and safeguard older adults’ best interests.Footnote87 Medical professionals should consider medical, legal, ethical and family issues in clinical examinations of older adults via an evidence-based framework.Footnote88 Finally, it is important to note that testamentary capacity is a legal test based on Banks v GoodfellowFootnote89 and ‘whether an individual has or lacks the capacity to do something is ultimately for a court to answer’.Footnote90

Ethical standards

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Dr Chi-Leung Lam has declared no conflicts of interest.

Dr Bonnie WM Siu has declared no conflicts of interest.

Mr Victor CK Yau has declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Robin Jacoby, Emeritus Professor of Old Age Psychiatry at Oxford University, for his support and expert advice in the preparation of this article.

Notes

1 Martyn Frost, Stephen Lawson and Robin Jacoby, Testamentary Capacity: Law, Practice, and Medicine (Oxford University Press 2015); American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging – American Psychological Association, Assessment of Older Adults with Diminished Capacity: A Handbook for Psychologists (American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging – American Psychological Association 2008) <www.apa.org/pi/aging/programs/assessment/capacity-psychologist-handbook.pdf> accessed 1 June 2019.

2 British Medical Association and the Law Society, Assessment of Mental Capacity: A Practical Guide for Doctors and Lawyers (Law Society 2015) vi–viii and 81–95.

3 WM Regan and SM Gordon, ‘Assessing Testamentary Capacity in Elderly People’ (1997) 90 Southern Medical Journal 13; Thomas G Gutheil, ‘Common Pitfalls in the Evaluation of Testamentary Capacity’ (2007) 35 Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 514.

4 Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1) 29–35.

5 British Medical Association (n 2); Carmelle Peisah, Jenna Macnab and Nick O’Neill, Capacity and Dementia: A Guide for Health Care Professionals in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (AACEPD and the State of NSW 2015).

6 United Nations, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) <https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf> accessed 1 October 2018; British Medical Association (n 2); Peisah, Macnab and O’Neill (n 5).

7 United Nations, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (n 6).

8 Peisah, Macnab and O’Neill (n 5).

9 Law and Technology Centre, University of Hong Kong, Community Legal Information Centre (2019) <https://www.clic.org.hk/en/topics/probate/> accessed 1 October 2019.

10 Yan-Xia Pang and others, ‘Advanced Investigation of Testamentary Capacity of the Mentally Disordered (Chinese)’ (2009) 25 Journal of Forensic Medicine (Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi) 208.

11 Chiu Man Fu v Chiu Chung Kwan Ying [2013], [2012] HCAP 9/2005, [2013] CACV 40/2012; Lee Wai Ho v Fung Kui Chuen [2014], HCAP 21/2011.

12 Chinachem Charitable Foundation Ltd v Chan Chun Chuen [2011], HCAP 8/2007, CACV 62/2010, FAMV 20/2011.

13 The Judiciary, Hong Kong Government SAR, ‘Legal Reference System’ [n.d.] <https://legalref.judiciary.hk/lrs/common/ju/judgment.jsp> accessed 1 October 2019.

14 Banks v Goodfellow [1870], LR 5QB 549, 565.

15 Chiu Man Fu (n 11).

16 Chi-Leung Lam and Helen Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap: Assessing Financial Capacity for the Elderly’ [2015] CME Bulletin: Hong Kong Medical Association; Chi-Leung Lam and Helen Chiu, ‘Assessing Financial Capacity for the Elderly in Hong Kong: A Review and the Way Forward’ (Second International Capacity Conference for the IPA International Congress, Berlin, Germany, October 2015); Chi-Leung Lam, ‘The Era of Mental Capacity Assessment for Financial Affairs for the Older Adults in Hong Kong’ [2016] Hong Kong Psychogeriatric Association Newsletters 1.

17 World Bank Group, Population Indicators (The World Bank Data 2016) <https://databank.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN/1ff4a498/Popular-Indicators> accessed 1 August 2019.

18 Census and Statistics Department, ‘Thematic Report: Ethnic Minorities’ [2012] <https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1120062/att/B11200622012XXXXB0100.pdf> accessed 30 March 2021; Census and Statistics Department, ‘Hong Kong Population Projection 2017–2066, Hong Kong SAR’ [2017] <https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp190.jsp?productCode=B1120015> accessed 1 September 2019.

19 Rating and Valuation Department (The Government of Hong Kong SAR), ‘Property Market Statistics’ [n.d.] <https://www.rvd.gov.hk/en/property_market_statistics> accessed 1 September 2019; Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

20 The Judiciary (n 13).

21 Choy Po Chun and another v Au Wing Lun [2018], CACV 177/2017, HKCA 210.

22 Chiu Man Fu (n 11).

23 The Judiciary (n 13).

24 Linda CW Lam and others, ‘Prevalence of Very Mild and Mild Dementia in Community-dwelling Older Chinese People in Hong Kong’ (2008) 20 International Psychogeriatrics 135; Ruby Yu and others, ‘Trends in Prevalence and Mortality of Dementia in Elderly Hong Kong Population: Projection, Disease Burden, and Implication for Long-term Care’ [2012] International Journal of Alzheimer Disease 1.

25 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

26 Kelly Purser, Eilis S Magner and Jeanne Madison, ‘A Therapeutic Approach to Assessing Legal Capacity in Australia’ [2015] 38 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 18.

27 Lam and Chiu, ‘Assessing Financial Capacity’ (n 16); Lam, ‘Era of Mental Capacity Assessment’ (n 16); Chi-Leung Lam, ‘A Practical Guide to Testamentary Capacity Assessment in Will-Making for Older Adults’ [2019] Self Study CME Series No 195 Hong Kong Doctor Union <http://cme.hkdu.org/cmeQuizzes/take/selfStudy/772> accessed 1 October 2019.

28 Choy Po Chun (n 21).

29 American Bar Association (n 1); British Medical Association (n 2).

30 United Nations, General Comments on Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2014] <https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/031/20/PDF/G1403120.pdf?OpenElement> accessed 1 April 2021; British Medical Association (n 2).

31 Choy Po Chun (n 21).

32 Kenward v Adams [1975, November 29], The Times, CLY 3591.

33 Lam, ‘Practical Guide to Testamentary Capacity Assessment’ (n 27); Chi-Leung Lam and Bonnie Siu, ‘A Risk-based Approach to Testamentary Capacity Assessment for Older Adults in Hong Kong’ (poster session presented at the 19th WPA World Congress of Psychiatry, Lisbon, Portugal, August 2019).

34 Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1); Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

35 Kenward v Adams (n 32).

36 British Medical Association (n 2); Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1); Re: LHHK [2020], HCMH 121/2019.

37 Cheung Wai Lan v Kwok Chung Chee [2015], [2014] HCAP 9/2009, [2015] CACV 128/2014.

38 Cheung Wai Lan v Kwok Chung Chee.

39 Sutton v Sadler [1857], 3 CBNS 87.

40 Banks (n 14).

41 Cheung Wai Lan v Kwok Chung Chee (n 37).

42 Cheung Wai Lan v Kwok Chung Chee (n 37).

43 Banks (n 14).

44 YL Yu and David Kan, ‘Medicolegal Issues Concerning Testamentary Capacity’ (2009) 15 Hong Kong Medical Journal 399; Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16); Choy Po Chun (n 21).

45 Banks (n 14).

46 American Bar Association (n 1).

47 United Nations, General Comments (n 30).

48 United Nations, General Comments (n 30).

49 C Katona and others, ‘World Psychiatric Association Section of Old Age Psychiatry Consensus Statement on Ethics and Capacity in Older People with Mental Disorders’ (2009) 24 International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 1319.

50 Peisah, Macnab and O’Neill (n 5); Lam and Chiu, ‘Assessing Financial Capacity’ (n 16).

51 Jung-Young Kim and others, ‘A Provincial Population-based Survey on Attitudes Towards Will and Testamentary Capacity of Individuals with Dementia’ (2016) 55 Journal of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 245.

52 Warren F Gorman, ‘Testamentary Capacity in Alzheimer’s Disease’ (1996) 4 The Elder Law Journal 225; Kelly Purser and Tully Rosenfeld, ‘Assessing Testamentary and Decision-making Capacity: Approaches and Models’ (2015) 23 Journal of Law and Medicine 121.

53 British Medical Association (n 2); Purser, Magner and Madison (n 26); Kenneth I Shulman and others, ‘Contemporaneous Assessment of Testamentary Capacity’ [2009] International Psychogeriatrics 433.

54 American Bar Association (n 1); British Medical Association (n 2); Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16) (emphasis added).

55 National Care Association, Making Decisions: A Guide for People Who Work in Health and Social Care (4th edn, Mental Capacity Implementation Program 2009); British Medical Association (n 2); Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1).

56 Kenneth I Shulman, Carole A Cohen and Ian Hull, ‘Psychiatric Issues in Retrospective Challenges of Testamentary Capacity’ (2005) 20 International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 63.

57 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

58 Lauren B Alloy, Joan Ross Acocella and Richard R Bootzin, Abnormal Psychology: Current Perspectives (6th edn, McGraw-Hill 1993) ch 1; Pamela Champine, ‘Expertise and Instinct in the Assessment of Testamentary Capacity’ (2006) 51 Villanova Law Review 25; Francis X Shen, ‘Law and Neuroscience 2.0’ (2012) 48 Arizona State Law Journal 1043.

59 Banks (n 14).

60 H Berry, ‘A Neuropsychiatric View of Testamentary Capacity’ [1988] Advocate Quarterly 11; American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn, American Psychiatric Association 2013); Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1); H Bennett, ‘Neurolaw and Banks v Goodfellow (1870): Guidance for the Assessment of Testamentary Capacity Today’ (2016) 35 Australian Journal on Ageing 289.

61 Frost, Lawson and Jacoby (n 1); Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16); Kenneth I Shulman and others, ‘Cognitive Fluctuations and the Lucid Interval in Dementia: Implications for Testamentary Capacity’ (2015) 43 Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 287.

62 Fayaz Roked and Abdul Patel, ‘Which Aspects of Cognitive Function are Best Associated with Testamentary Capacity in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease?’ (2008) 23 International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 552.

63 Shulman and others, ‘Contemporaneous Assessment’ (n 53); Shulman and others, ‘Cognitive Fluctuations’ (n 61).

64 KM Kennedy, ‘Testamentary Capacity: A Practical Guide to Assessment of Ability to Make a Valid Will’ (2012) 19 Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 191.

65 Karen Sullivan, ‘Neuropsychological Assessment of Mental Capacity’ (2004) 14 Neuropsychology Review 131.

66 Gutheil (n 3); Kennedy (n 64); Yeung Yuen King v Kong Wai Ha [2014], HCAP 19/2010; LexisNexis, ‘Actual Undue Influence’ in Halsbury’s Laws of Hong Kong, Wills, Probate, Administration and Succession (LexisNexis, division of RELX [Greater China] Ltd 2015) 425.

67 C Peisah and others, ‘The Wills of Older People: Risk Factors for Undue Influence’ (2009) 21 International Psychogeriatrics 7; Sherif Soliman, ‘Undue Influence: Untangling the Web (Legal Digest)’ (2013) 41 Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 4; C Peisah and others, ‘Deathbed Wills: Assessing Testamentary Capacity in the Dying Patient’ (2014) 26 International Psychogeriatrics 209; Thomas E Simmons, ‘Testamentary Incapacity, Undue Influence, and Insane Delusions’ (2015) 175 South Dakota Law Review 60.

68 IN Perr, ‘Wills, Testamentary Capacity and Undue Influence’ (1980) IX Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 15; Edwards v Edwards [2007], All ER (D) 46; Peisah and others, ‘The Wills of Older People’ (n 67).

69 Kenneth I Shulman and others, ‘Assessment of Testamentary Capacity and Vulnerability to Undue Influence’ (2007) 164 American Journal of Psychiatry 722; Peisah and others, ‘Deathbed Wills’ (n 67); Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

70 Peisah and others, ‘The Wills of Older People’ (n 67); Kennedy (n 64).

71 The Judiciary (n 13); Li Chi Loy v Li Lai Lan Candiac [2008], HCAP 4/2003; Soliman (n 67).

72 Lam, ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27); Lam and Siu (n 33).

73 Ibid.

74 British Medical Association (n 2).

75 Robin Jacoby and Peter Steer, ‘How to Assess Capacity to Make a Will’ (2007) 335 British Medical Journal 155; Howard Smith, ‘A Review of Testamentary Capacity’ (2015) 160 Solicitors Journal 19-04-16; Choy Po Chun (n 21).

76 Lam, ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27); Lam and Siu (n 33); Yu and Kan (n 44).

77 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16); Lam, ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27); Lam and Siu (n 33).

78 Lam, ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27); Lam and Siu (n 33).

79 Banks (n 14).

80 Jacoby and Steer (n 75); Kennedy (n 64); Smith (n 75).

81 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

82 Jacoby and Steer (n 75).

83 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

84 Peisah and others, ‘Deathbed Wills’ (n 67).

85 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16); Shulman and others, ‘Cognitive Fluctuations’ (n 61); Kelly Purser and Tully Rosenfeld, ‘Too Ill to Will? Deathbed Wills: Assessing Testamentary Capacity Near the End of Life’ (2016) 45 Age and Ageing 334.

86 Lam, ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27); Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16).

87 Yu and Kan (n 44); Alan Doris, ‘Understanding Testamentary Capacity’ (2012) 20 Medical Protection Society Casebook (New Zealand) 8; Purser and Rosenfeld, ‘Assessing Testamentary and Decision-making Capacity’ (n 52).

88 Lam and Chiu, ‘Mind the Gap’ (n 16); Lam, ‘Era of Mental Capacity’ (n 16); Lam ‘Practical Guide’ (n 27).

89 Banks (n 14).

90 British Medical Association (n 2).