?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

While the killing of one’s own infant is an undoubtedly harrowing crime, there exists little research exploring attitudes toward these individuals. Such work has focused primarily on depictions of mothers, yet U.K. government data indicate that the majority of infant homicide cases involve paternal suspects. A sample of U.K. residents (n = 245) participated in a mixed-methods design to explore attitudes toward mothers and fathers who have been accused of murdering their infant child and whether parental mental health issues impacted these judgements. Results aligned with the chivalry hypothesis wherein maternal suspects were evaluated more leniently. Qualitative analyses uncovered hidden gender expectations: mothers were ascribed blame when the father was accused of infant homicide, a finding that was not present in the reverse scenario. This suggests that traditional views of motherhood conflict with a shifting social landscape that is seeing an increase in stay-at-home fathers and working mothers.

Introduction

Infant homicides in the media

In 2017, shortly after giving birth to her daughter Mia Kelly in the bathroom of their flat, Rachel Tunstill fatally stabbed the newborn with a pair of scissors 14 times before wrapping the body in a plastic bag and disposing of it in the kitchen bin (BBC News, Citation2017). News of the unusual and brutal offence generated national headlines, which highlighted her apparent lack of remorse, her claim that her recollection of the event was hazy and multiple emotion-laden reactions from the police inspector and the trial judge (BBC News, Citation2019; Grafton-Green, Citation2019). The case drew even more attention when it was announced that Tunstill had successfully appealed her 20-year sentence for the murder of her newborn daughter, arguing that a lesser charge of infanticide should have been considered at the initial trial (BBC News, Citation2018). Despite the backing of two psychiatrists supporting the defense of infanticide, Tunstill was again found guilty of murder and sentenced to 17 years in prison (Rodger, Citation2019).

One year after Tunstill’s retrial, another child homicide case involving a father and his 3-month-old daughter began to make waves in the news after paramedics were called to the home when the baby was found unresponsive (BBC News, Citation2021; Cheshire Constabulatory, Citation2021). Medical scans indicated that the newborn had sustained prior and recent rib fractures and was also suffering from massive bleeding of the brain and a fractured neck, which contributed to her ultimate passing (Crown Prosecution Service, Citation2021). Although neither parent could provide a reason for how the child could have sustained the injuries, her father, Anthony Miley, was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 13 years’ incarceration (Dobson, Citation2021). Like the Tunstill case, media coverage of the Miley homicide repeatedly emphasized the degree of injury as well as Miley’s remorselessness (who still professes his innocence) and the affective responses of criminal justice personnel (BBC News, Citation2021; Cheshire Constabulatory, Citation2021; Dobson, Citation2021).

Prevalence of infant homicide

While the Tunstill and Miley cases garnered considerable media attention, it followed the pattern of news coverage overemphasizing graphic crimes. According to the latest Office of National Statistics (ONS) Homicide in England and Wales report, the killing of children under 1 year of age is, fortunately, quite rare. Between 2009–2010 and 2019–2020, the number of newborn homicide victims in the ranged between 12 and 30 each year (ONS, Citation2021). This is dwarfed by much higher numbers among youth and young adults, whose frequencies often exceed 100 deaths annually. However, when examining the proportion of homicides across age groups (rather than overall frequency), the rate of infant homicide emerges as higher than for any other age bracket reported by the ONS, a finding that has been consistent across the past decade. For instance, in 2019–2020, the rate of infant homicides was 28 per 1,000,000, which was seven times higher than for children aged 1–4 years, 14 times higher than for children aged 5–15 years, and moderately higher (1.2 times) than for youth aged 16–24 years (ONS, Citation2021). Unlike traditional homicide, there does not appear to be a clear gender divide among victims.

Infant homicide is also unique in that it is often cited as the only type of homicide that appears to be predominantly perpetrated by females (generally the infant’s mother; Dawson, Citation2015; Kunz & Bahr, Citation1996; Sorenson & Peterson, Citation1994). A recent Freedom of Information request by the authors to the U.K. Home Office (Citation2022) confirmed that homicide cases involving a victim under the age of one involved almost exclusively parental suspects. However, the obtained figures indicated that 62% of the 143Footnote1 infant homicides that have taken place in England and Wales in the last decade involved a male suspect. Of the 88 cases where a male was accused, only three identified a suspect that was not the father; mothers were identified in 43 of the 55 cases that involved a female suspect. These figures run somewhat contrary to what was found by earlier researchers and align with the general trend of men accounting for the vast majority of homicide perpetrators (ONS, Citation2021). Interestingly, filicide – the killing of one’s child, regardless of age – does not tend to have a gender imbalance with respect to perpetrators, although some have suggested that fathers may be more often culpable in the deaths of older children (Little & Tyson, Citation2017; Stöckl et al., Citation2017). Indeed, Dawson’s (Citation2015) analysis of 1,612 Canadian filicide cases that took place between 1961 and 2011 found that fathers were accused in a growing majority of filicide cases as the child’s age approached 18. This gender divide also appears to be widening: for the 1974–1983 period there was only a four-point gap between males and females accused of filicide, which ballooned to 22 points in the 2004–2011 period (Dawson, Citation2015). This may be driven by an increase in the proportion of killings by stepfathers, which doubled between the 1974–1993 and 1994–2011 periods.

Child-killing terminology

Properly naming modern-day infant killing is difficult due to the gendered nature of the term infanticide and its legal connotations. In many jurisdictions, infanticide is recognized as its own offence that is exclusive to mothers who kill their child within the first year of life while suffering from some form of mental impairment on account of the birthing process or lactation (Infanticide Act, Citation1938; see Moseley, Citation1986, for a review). Other terms used to describe the killing of one’s child(ren) are either too short in duration (neonaticide, referring to infants killed during the first 24 hours after birth) or too long (filicide, referring to children of any age killed by their parents). For the purpose of this study, we will use the term infant homicide, which will capture infants under one year of age who have been killed by their parent(s).

The gendered nature of infant homicide media coverage

Despite the severity and tragedy of child killings, there is a dearth of research on how members of the community respond to and evaluate those who commit these acts. This omission is noteworthy as understanding what situational and personal factors may influence judicial decisions is paramount to ensuring a fair trial – especially in cases that may evoke considerable emotions. Much of the literature in this area focuses on the way these individuals, particularly mothers, are portrayed in the media. This is informative as the way the media portrays justice-involved persons has been implicated in the public’s attitudes toward them and the degree of punishment that they endorse (Malinen et al., Citation2014; Spiranovic et al., Citation2012). More broadly, news reports (and the media more broadly) are seen as both reflections and curators of cultural scripts (Ochs, Citation1993), suggesting that these depictions may have considerable overlap with how members of that society view this group of offenders. With research exploring public attitudes toward perpetrators of infant homicide lacking, exploration of the ways in which they are portrayed in the media may be the best means of gauging broader societal judgements.

Much of the research that has explored media portrayals of mothers who have killed their children has taken place outside of the UK. Such work has emphasized the contrast between the violent acts and the societal expectations of femininity and motherhood, aligning with the good/bad woman dichotomy that is present in broader social discourses (Ballinger, Citation2007; Easteal et al., Citation2015; Edwards, Citation1984). Others have expanded upon this, finding that females who kill are presented as ‘bad, mad or sad’ (e.g. Cavaglion, Citation2008; Easteal et al., Citation2015). Motz (Citation2016) has also noted that press coverage of maternal filicide cases tends to be reductive and stereotypical. As discussed below, these issues are apparent in coverage of mothers who have committed acts falling under the broader filicide domain as well as the more specific neonaticide category.

Bad mothers

Saavedra and Cameira (Citation2018) explored 26 cases of maternal neonaticide reported in a Portuguese newspaper. In nine of these cases, media coverage mentioned that the mothers concealed their pregnancy from friends and family, dismissing the notion that neonaticide was carried out in a spontaneous manner under the influence of an acute psychiatric episode. The carrying out of a preconceived neonaticide in such a cold, business-like manner as presented clearly clashes with societal expectations of motherly warmth (Stangle, Citation2008; Wilczynski, Citation1991). Similarly, the emphasis on the violent means of killing their newborn child – which included one depiction of a mother incinerating her late child’s corpse – is presented in contrast to the warm, gentle ideals of both femininity and motherhood (Saavedra & Cameira, Citation2018). Barnett (Citation2006) categorized the frequency of select terms that were used in American coverage of 10 maternal filicides to depict the mothers as ‘flawed’. Among the more frequently terms used to describe the mothers were abusive/neglectful (22%), deceptive/devious (17%) and callous (12%). Naylor (Citation2001) reported that in the wake of killing her 18-month-old son, press coverage of Rosa Richards emphasized her supposed impatience, proneness to vulgarity, violence and promiscuity. Cavaglion’s (Citation2008) analysis of Israeli media coverage of high-profile maternal filicide cases also found support for this ‘bad’ characterization. Interestingly, this discourse only appeared to take place in the cases where the accused women were of Arabic descent, despite these women having experienced hardships and difficulties that served as mitigating factors (both in the media and in the legal outcome) when a Jewish girl was on trial for killing her newborn (see Sad mothers below).

Mad mothers

According to Allen (Citation1987), the infanticide legislation found in England and other countries are both examples of and perpetrators of the ‘psychiatrization’ of maternal infant killing. That the media latches on to this stereotype in their coverage of infanticide and other child-killing stories is thus not surprising, given their propensity of adhering to simplified, mythical explanations (Motz, Citation2016). This is particularly noteworthy, as multiple studies have reported relatively low rates of mental health problems among women who have killed their newborns (e.g. Ciani & Fontanesi, Citation2012; Hatters Friedman & Resnick, Citation2007; Lewis & Bunce, Citation2003), while prevalence rates among filicidal mothers tend to range between one third and two thirds (Poteyeva & Leigey, Citation2018). Despite this, the term mentally ill/insane was the most frequently used descriptor of filicidal mothers in Barnett’s (Citation2006) analysis. Depression (postpartum or general) was also highly prevalent (37%) in Rock’s (Citation2020) review of maternal filicide case coverage in Canadian media, while posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were also mentioned. Again, this indicates that the linkage between infant homicide and mental illness is overemphasized in the media. Although Israel does not have specific legislation regarding infanticide, evidence suggests that the stereotype of the unbalanced or insane mother still exists. Cavaglion (Citation2008) analysed Israeli media coverage of six high-profile cases of maternal filicide across multiple outlets. In confirmation of Motz’s (Citation2016) argument that press coverage falls back on stereotypes, news articles of the cases highlighted – often in the title – the apparent mental illness or insanity of the accused mother. Although in multiple instances this was perpetuated by interviews with the respective women’s husbands, one of the women had actually undergone a psychiatric evaluation the day before she killed her child, which found no grounds for hospitalization. In another case, the judged ordered a psychiatric evaluation, which did not confirm their suspicions. Wilczynski’s (Citation1991) analysis of 22 infanticide cases identified the mad mother narrative in the majority of cases. Although this combined newspaper accounts with court records and interviews with probation officers (and thus it is impossible to determine the presence of each narrative in each form of information), it does suggest that this discourse extends beyond the newsroom and into the courtroom. Indeed, mental illness is more likely to be considered as an explanatory factor when women are accused of killing their children rather than men (Orthwein et al., Citation2010).

Sad mothers

The concept of sad mothers is based on the notion that they were victims of poor circumstance, which forced them to act out the killing of their child. This has been imported from the broader female homicide perpetrator literature (see Coughlin, Citation1994, for a review). While recognizing the external pressures that mothers face that may contribute to the deaths of children is important and worth consideration (especially in the legal context), this has been criticized as being too paternalistic (Morissey, Citation2003; Nagel & Johnson, Citation1994). Dubbed the chivalry hypothesis, it suggests that women (especially those that adhere to traditional gender norms) may receive less severe punishments on account of paternalistic attitudes that diminish their culpability by being seen as less agentic (Cavaglion, Citation2008; Nagel & Johnson, Citation1994). Cavaglion (Citation2008) highlights one case of this in the Israeli news of Merav Edri, a young Jewish woman of low socioeconomic status whose pregnancy was the result of a sexual assault and whose parents were unable to provide her with the psychological support needed. It was noted in the analysis that ensuing stories became more forgiving of the young woman, with both the judge and investigators stressing the external pressures she faced. Cavaglion (Citation2008) interprets this ‘transformation’ as undermining the woman’s agency by presenting the child killing as inevitable rather than the result of her own deliberation. This also seems to have been the case for Richards, who Naylor (Citation2001) indicated was first presented as a ‘bad’ mother before later press coverage shifted to the ‘sad’ mother narrative. In this instance, Richards was reframed as a woman suffering from an intellectual disability and a victim of previous abuse that left her unable to cope with everyday stressors. Here, too, Naylor notes the lack of agency presented in the new media portrayals. Rapaport (Citation2005) also notes how the cases of two American teenagers who committed neonaticide incorporated aspects of the sad narrative; specifically, they were portrayed (at least by some media outlets) as depraved teenagers who lacked the maternal resources that would have been available to adult women.

Fathers

There is considerably less literature exploring media depictions of fathers who have killed their children relative to mothers. Even when cases are covered, they tend to receive less attention than cases of maternal filicide (Grau, Citation2013). In one of the few articles to examine media coverage of paternal filicide, Cavaglion (Citation2009) reported that ‘there was a process of oversimplification and polarisation that emphasised the fathers’ negative traits and actions, and mitigated the positive ones’ (p. 131) in the 45 articles analysed. Unlike their previous analysis (Cavaglion, 2008) of maternal filicide coverage, this pattern did not appear to differ based on the perpetrator’s race or circumstance. In all but one instance, the men’s agency was accentuated rather than diminished. The faces and facial expressions of the fathers were also the subject of considerable analysis. The men were demonized for appearing indifferent or aloof during court proceedings while their faces themselves were described as monstrous, evil and inhuman. Thus, rather than a ‘bad fathers’ narrative, it appears as though the press is more concerned with constructing a ‘bad’ narrative where the man’s relationship to their deceased child is not central to their public identity.

Grau (Citation2013) notes that the fatherhood aspect is often downplayed in media coverage; despite its obvious relevance to readers, 42% of news article headlines in their analysis did not include a parental identifier. The articles themselves also appeared to downplay this relationship, referring to the men’s connection to the deceased child’s mother or outright neglecting to mention the paternal role that they occupied. Grau (Citation2013) argues that this is a deliberate attempt to minimize the men’s role as paternal figures in exchange for a solitary ‘killer’ label. In one instance, a case of paternal filicide was justified in the news by the man’s claim that he did not believe he was the biological father (Grau, Citation2013). The subtle acceptance of the media in accepting that this may serve as a rationale belies the cultural scripts ascribed to stepfathers and raises questions about how they may be portrayed when killing their non-biological children. This is important as stepfathers are responsible for a disproportionate number of filicide cases (Dawson, Citation2015), with one analysis finding that stepfathers with a history of violence were over 740 times more likely to kill their child than an age-matched male in the general population (Pritchard et al., Citation2013). Recently, Little (Citation2021) looked at how filicidal stepfathers were portrayed in Australian media. In two of the three cases explored, however, the stepfathers served as accessories to filicide, helping conceal bodies and directing police attention elsewhere through calls to the public for information. Once discovered, these men were portrayed as stepfathers who were submissive to their female counterparts that outdid them in ‘performing masculinity’. This is a stark contrast to the (extreme) masculinity-on-display narrative that was the hallmark of the articles Cavaglion (Citation2009) analysed.

Participant characteristics that may influence attitudes

Traditional gender norms and boundaries are imbued in the media’s defining and contrasting of mothers and fathers who have committed some form of filicide (inclusive of infanticide and neonaticide). It is likely, then, that subscribing to these beliefs may impact societal reactions to this group of offenders. This has been demonstrated previously in cases of violent crime such as sexual assault and homicide (Angelone et al., Citation2012; Tuncer et al., Citation2018). It may be particularly damning for mothers, as acts of aggression transgress what is considered traditional femininity (Koons-Witt et al., Citation2014). However, a recent dissertation study by Sandoval (Citation2021) found no association between gender role attitudes and punitiveness toward a filicidal mother, even when the vignette aligned with a motherhood trope. Thus, gender role attitudes may only be influential when a clear transgression of traditional gender norms occurs.

Moreover, an emerging body of literature from our group has highlighted the importance of measuring psychopathic personality traits within research that explores judgements of offending behaviour (e.g. Fido et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Psychopathic personality, a constellation of traits associated with shallow emotion processing, low empathy and aggressive and antisocial behaviour (Viding & McCory, Citation2019), has also been a focal point in the prediction of judgements of offending behaviour over the last decade. Although psychopathy can be discussed from a clinical perspective as being a taxon (i.e. the viewpoint that either individuals are a psychopath or they are not; see Harris et al., Citation1994), it is common for research to explore psychopathy on a continuum due to its greater relevance for tailoring discussions in public (as well as criminal justice) arenas (see Reidy et al., Citation2015). Individuals in the general population with higher levels of psychopathic traits not only report more lenient judgements of physical (Peace & Valois, Citation2014) and digital (Fido et al., Citation2022) offending behaviour, but are also more likely to endorse and enact deviant behaviour themselves (Fido et al., Citation2022). Results of the studies documented above might be explained by persons demonstrating a greater degree of psychopathic traits having a diminished emotional response to criminal events, including such events that are violent or disturbing in nature. Indeed, psychopathy has been linked with lower levels of victim empathy and higher levels of victim empathy (Jonason et al., Citation2017). As emotional responses to crime have been linked to a desire for increased punitiveness (Hartnagel & Templeton, Citation2012), it follows that psychopathic traits may be linked to a greater degree of leniency. Further, it has been associated with a willingness to adopt more utilitarian strategies in personal dilemma situations via lower victim empathy (Takamatsu, Citation2018). Greene (Citation2008) argues that judgements of infanticide cases are universally negative due to the high socio-emotional response and the weakness of a practical justification: could psychopathic traits be the fly in the ointment?

Current study

Despite the evocative nature of infant homicide cases and the relatively high rates in which it occurs (which often only captures the most obvious, easily detectable instances; Beyer et al., Citation2008), it has rarely been explored in psychological discourse. Though there have been some studies that have explored the profiles of individuals convicted of infant homicide and what precursors may have facilitated the offence (e.g. Craig, Citation2004; Resnick, Citation1969; Shelton et al., Citation2011), to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has been no research published that explores people’s attitudes toward this group of offenders. This is particularly curious, given the prominence that these cases serve in the news media, which has in itself become a growing body of literature. It is also a concerning oversight that makes it difficult to ensure the impartiality of juries in infant homicide cases.

In this explorative paper, we begin to fill this gap in the literature by using comparative statistics to first explore the role of participant and perpetrator sex on the leniency of offence-related judgements. Second, we seek to explore whether personality traits previously implicated in lenient offence-related judgements (e.g. psychopathy) will also map onto infant homicide cases, and whether this relationship might be further moderated by the sex of the perpetrator. Variables likely to impact such outcomes – namely, age, mental health stigma, mental well-being and beliefs about gender roles – will be controlled for (see Fido et al., Citation2022; Maroño & Bartels, Citation2020; Yin et al., Citation2022). Third, we explored participants’ narratives about infant homicide with open-ended questions.

Method

Participants

To determine our target sample size, we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power (Version 3.1.9.2). Assuming an anticipated medium effect size (d = 0.50; Cohen, Citation1992, ensuring any observed effects were of practical importance) and an adjusted alpha level of .025 to account for the two moderation analyses, a minimum of 104 participants would be required to have 95% power in our planned analyses. We aimed to recruit upwards of 200 participants to account for incidents of missing data and participant withdrawals.

A total of 245 U.K. participants (Mage = 37.17 years, SD = 12.83; 49.4% female) responded to an online advertisement placed on the crowdsourcing website Prolific, which featured details about the study and provided an online link to participate. This approach boasts comparable data to that obtained through lab and face-to-face means (Peer et al., Citation2017), allows for data representative of the U.K. census and also ensures equal sex representation for the purposes of data analysis. Inclusion criteria suggested that participants should be of English nationality, be fluent in English, be aged 18 years or over, have no criminal convictions and be heterosexual. In line with our other work into judgements of offending behaviour as a function of sex (e.g. Fido et al., Citation2021, Citation2022), we opted to use this latter inclusion criterion as a means of controlling for sexuality in our work, which might otherwise convey unknown variability within our data. It is our intention of exploring wider socio-sexual factors in future studies within this programme of research. Participants provided written informed consent in accordance with approved central university research protocols and national ethical guidelines by ticking a box on both the first and last pages of our online survey. To ensure a moral compliance, all completers were reimbursed with £1.10 for their participation. There are no data to suggest that this payment had any adverse impact on participation.

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their age, sex and nationality.

Materials

Vignettes and judgements of infanticide (adapted from Bothamley & Tully, Citation2018)

Participants were randomly split into two groups before being asked to read one of two researcher-created vignettes outlining an incident of filicide based on typical media reports. Half received a vignette where the perpetrator was male, and half received a vignette where the perpetrator was female. An example of a vignette used is shown below:

After the birth of their first baby two months ago, Sarah and Mark have recently been struggling to adjust not only to the financial implications of parenthood, but to the lack of sleep, time for self-care, and the near-constant crying of their newborn. Neither parent had a diagnosis of any mental illness. One evening, Sarah was left alone with the baby after Mark was unexpectedly called out to work. Sarah tried for hours to get the baby to sleep, but everything she did seemed to frustrate and upset the baby even more. In a fleeting moment; tired, hungry, and angry at her inability to sooth the baby, Sarah lashed out by shaking the baby suddenly whilst shouting ‘Just why won’t you go to sleep?’. The baby fell silently into their crib. As short as it was, the shaking was enough to kill the baby. Sarah felt instant regret and was disgusted with her sudden, reckless behaviour. She called an ambulance immediately.

The Stigma-9 Questionnaire (STIG-9; Gierk et al., Citation2018)

The STIG-9 comprises 9 items that measure perceived mental health stigma (e.g. ‘I think most people consider someone who has been treated for a mental illness to be dangerous’) using a 4-point scale. Each item is rated using a scale anchored from ‘0 – disagree’ to ‘3 – agree’ (Cronbach’s α = .91). High scores indicated greater levels of mental health stigma.

Gender Role Beliefs Scale (GRBS; Brown & Gladstone, Citation2012)

The GRBS comprises 10 items that measure beliefs about gender roles (e.g. ‘It is disrespectful to swear in the presence of a lady’) using a 7-point scale. Each item is rated using a scale anchored from ‘1 – strongly agree’ to ‘7 – strongly disagree’ (Cronbach’s α = .77). High scores indicated greater levels of non-traditional role beliefs.

Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM; Patrick, 2010)

The TriPM comprises 58 items that measure psychopathy using a 4-point scale. The TriPM can be divided into meanness (19 items, e.g. ‘I don’t mind if someone I dislike gets hurt’), boldness (19 items, e.g. ‘I enjoy a good physical fight’) and disinhibition (20 items, e.g. ‘I jump into things without thinking’) subscales. Each item is rated using a scale anchored from ‘False’ to ‘True’ (Cronbach’s α = .91). High scores indicated greater levels of psychopathy.

The Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS; Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009)

The SWEMWBS consists of 7 items measuring recent (i.e. past 2 weeks) psychological functioning and emotional and mental well-being (e.g. ‘I have been dealing with problems well’). Participants are asked to rate their experience of each statement on a 5-point scale from ‘1 – None of the time’ to ‘5 – All of the time’, where higher scores are indicative of greater mental well-being (Cronbach’s α = .87).

Procedure

Participants initially entered their demographic information. Following this, the GRBS, STIG-9, TriPM and SWEMWBS were presented in a randomized order to reduce the likelihood of order effects influencing the data. Finally, participants were presented with one of two vignettes (differing only by the sex of the parents) and were asked to complete both the judgement questions and rationale for the responses they made. On average, the study took about 10 min to complete.

Analysis plan

Pearson correlations were computed between the focal predictor (psychopathy), the dependent variable (judgements of incidents of filicide), the moderator variable (sex of the offending parent) and covariates (age, mental health stigma, mental well-being and beliefs about gender roles) in relation to the whole sample, as well as within each sex. We then used Model 1 of the PROCESS plugin for SPSS (Version 3; Hayes, Citation2018) to run two moderation models (one each for male and female responders). All reported beta values are unstandardized (Hayes, Citation2018).

Text data were analysed using content analysis, with the software IRaMuTeq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires; Ratinaud, Citation2009). The text materials were organized in two corpora, one for the male/father perpetrator vignette and one for the female/mother perpetrator vignette. These were analysed through descendant hierarchical classification (DHC), similarity analysis, word cloud and confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA). In this analysis, segments of text (ST) are classified according to their lexicon, based on frequency and χ2 of words. Segments of text were automatically generated by the programme and typically have three lines, which represent the context of words that are classified in the analysis. The segments with a common lexicon are then grouped into classes called elementary context units (ECUs), which organize the STs based on vocabulary similarities within each class and differences in vocabulary between classes. The classes were then analysed taking in consideration typical STs and word cloud – a procedure that provides a graphic representation where most frequent words are represented by a larger font size (Camargo & Justo, Citation2013).

Results

Sex differences

A 2 × 2 analysis of variance was used to test the main effects of participant sex (male vs. female) and perpetrator sex (male vs. female) and their interaction on judgements of filicide. Despite a lack of statistically significant main effect of participant sex, F(1, 239) = 0.279, p = .598, = .00, and the interaction, F(1, 239) = 0.364, p = .547,

= .00, there was a statistically significant main effect of perpetrator sex on judgements, F(1, 239) = 18.694, p < .001,

= .07, such that on average, participants reported harsher judgements of incidents of filicide involving male than of female perpetrators, t(241) = 4.36, p < .001, d = 0.56. Next, independent t tests were used to delineate sex differences within our sample (see ). Males reported higher scores on measures of psychopathy, t(241) = 15.91, p < .001, d = 0.84, than females, and females reported higher gender role beliefs, t(243) = 1.20, p = .004, d = 0.37, than males. There were no significant differences in age, judgements of filicide, mental health stigma and mental well-being between sexes.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for male and female questionnaire scores.

Pearson correlations

We computed bivariate Pearson correlations between the predictor variable (psychopathy), the dependent variable (offence-related judgements) and covariates (age, mental health stigma, mental well-being and beliefs about gender roles) across the whole sample, and as a function of the moderator variable, the sex of the perpetrator (see ). Psychopathy was positively associated with mental health stigma in all groups and was associated with more lenient judgements in the female perpetrator subgroup specifically. Moreover, mental health stigma was negatively associated with mental well-being in all groups.

Table 2. Pearson correlations between variables for the whole sample, as well as within males and females, specifically.

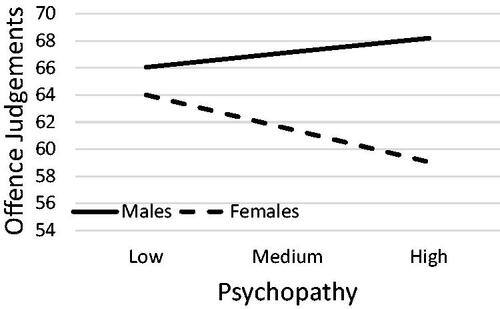

Moderation analyses

We conducted two moderation analyses using Model 1 of the PROCESS plugin for SPSS (Hayes, Citation2018). In each analysis, psychopathy was the focal predictor (X), and judgements of incidents of filicide was the dependent variable (Y). The moderator variable was the sex of the offending adult (W). The variables of age, mental health stigma, mental well-being and beliefs about gender roles were controlled for as covariates. Model coefficients are presented in and , and moderated regression trends are presented in .

Figure 1. Moderation analysis output of the effects of psychopathy on judgements of infant homicide offences as a function of offender sex.

Table 3. Moderation coefficients for male responders.

Table 4. Moderation coefficients for female responders.

Model 1: male participants

The moderation model for male responders accounted for 14% of the variance in judgements of incidents of filicide, and was statistically significant, F(7, 115) = 2.67, p = .010. As indicated in , harsher judgements (e.g. more severe crimes, more impactful) of incidents of filicide were reported when the offender was the father than when the offender was the mother. Moreover, although there was no main effect of psychopathy on judgements, there was a significant interaction between psychopathy and perpetrator sex, such that psychopathy was associated with more lenient judgements of filicide when the offender was the mother, but not the father (see ). No covariates were statistically significant.

Model 2: female participants

The moderation model for female responders accounted for 10% of the variance in judgements of incidents of filicide, and was not statistically significant, F(7, 110) = 1.77, p = .100. As indicated in , harsher judgements (e.g. more severe crimes, more impactful) of incidents of filicide were reported when the offender was the father than when the offender was the mother. There was neither a main effect of psychopathy on judgements nor a significant interaction between psychopathy and offender sex, nor were any covariates statistically significant.

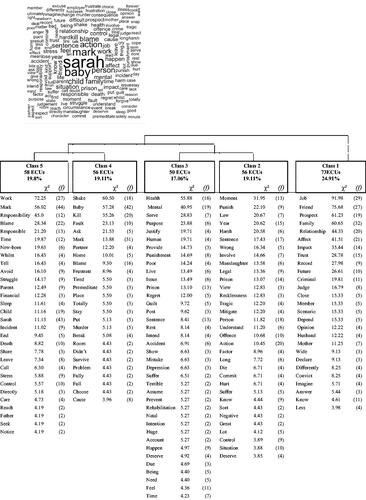

Content analysis male perpetrator

The corpus analysed contained 120 answers of participants who read this vignette, which were decomposed into 342 text segments. The DHC utilized 62% of the segments with a common lexicon to form the classes. Class 1 grouped 23.5% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Sentence and punishment’; Class 2 grouped 16.4% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Emotional control’; Class 3, labelled ‘Intention and blame’, grouped 16.4% of text segments; Class 4 grouped 20.7% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Social punishment’; finally, Class 5, labelled ‘Mother’s role’ grouped 23% of the text segments. An example extract of each class is presented in . shows the five identified classes, words in each class, chi-square values and frequency of each word. The most frequent words in each class, respectively, were sentence, baby, child, relationship and work.

Figure 2. Descendant hierarchical classification (DHC) dendrogram: male perpetrator. Note. Class 1: Sentence and punishment; Class 2: Emotional control; Class 3: Intention and blame; Class 4: Social punishment; Class 5: Mother’s role. ECUs = elementary context units.

Table 5. Representative extracts of each class.

The word cloud () provides a graphical representation of the most frequent words for this vignette. The names of the two main characters were frequently mentioned, and also the words baby, child, action, control and kill. These words were typically mentioned in the context that the act of losing control led to killing the baby.

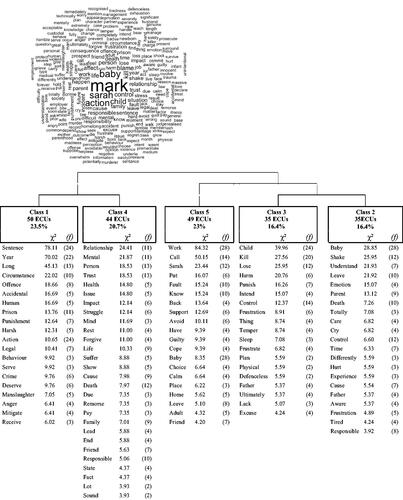

Content analysis female perpetrator

The corpus analysed contained 123 answers of participants who read this vignette. shows the five identified classes, words in each class, chi-square values and frequency of each word. The DHC analysed 357 segments of text, with a rate of utilization of 82%. The most frequent words in each class were, respectively, job, moment, health, shake and work. Class 1 grouped 24.9% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Impact’; Class 2 grouped 19.1% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Sentence and punishment’; Class 3, labelled ‘Mental health’, grouped 17.1% of text segments; Class 4 grouped 19.1% of the text segments and was labelled ‘Blame’; finally, Class 5, labelled ‘Social support’ grouped 19.8% of the text segments. Examples of extracts of each class are presented in . The most frequent word in each class were, respectively, job, moment, health, shake and work.

Table 6. Representative extracts of each class.

The word cloud in provides a graphical representation of the most frequent words for this vignette. The names of the two main characters were frequently mentioned, and also the words baby, person, child, family, action, blame, sentence. This indicates that, when analysing the situation, participants focused not only on the act, but also on the sentence and blame attribution.

Discussion

Overview of key findings

The present empirical study is likely the first of its kind to assess attitudes toward both mothers and fathers who have killed their infant child. Results indicated that regardless of participant sex, fathers who are accused of infant homicide are judged more harshly than their maternal counterparts. Moderation analyses revealed that for male participants, the differences in mother versus father offender judgements were partially a product of psychopathy, where males with higher levels of psychopathy are more forgiving of mothers who have committed infanticide. Interestingly, this did not appear to be an artifact of mental health stigma or gender role beliefs, as psychopathy was not associated with either among the male participants (but was among females). Textual analyses of participant responses also indicated some key differences between the mother (Sarah) and father (Mark) perpetrator conditions. For instance, when Mark was presented as the person responsible for the child’s death, one of the largest response categories centred around Sarah and her relation to the event, with some insinuating that she failed in her duty as a mother by not being on parental leave and accepting a work shift when Mark was tired. Such comments were not made about Mark when Sarah was presented as the child’s killer, although some suggested that he could have been more supportive. The Sarah-as-perpetrator scenario also elicited some unique comments from participants, namely surrounding her mental health and the impact that her actions will have on others.

Interpretation of findings

The overall pattern of results of this study is consistent with the suggestion that infant homicide is viewed through a chivalric lens, wherein females are treated more leniently than men (Brennan, Citation2018; Nagel & Johnson, Citation1994). Written responses from participants emphasizing the mothers’ (but not the fathers’) mental illness are also aligned with the ‘mad mothers’ stereotype that is often present in news coverage of such cases (Barnett, Citation2006; Rock, Citation2020). This is particularly interesting given that the vignette explicitly stated that neither offending parent had a mental health diagnosis, suggesting the salience of the mad mothers trope. Evidence for the ‘bad mothers’ narrative was also present, but was interestingly most apparent in the paternal perpetrator condition, where Sarah was seen as callous, neglecting her supposed motherly duties for the sake of her career. Thus, even when Mark committed the act, some blame was directed at Sarah for deviating from cultural scripts and expectations that emphasize soft femininity and nurturing motherhood (Easteal et al., Citation2015; Edwards, Citation1984). Interestingly, there did not appear to be any meaningful quantitative relationship between gender role beliefs and judgements of Sarah or Mark. Further, both male and female participants scored well above the scale midpoint on the gender role beliefs scale, indicating more feminist viewpoints. This suggests that the measures used may not capture the subtle ways in which gender role beliefs influence perceptions of individuals accused of killing their own children, similar to recent work identifying a discrepancy between quantitative and qualitative rape myth acceptance (Zidenberg et al., Citation2022).

That the results of the present study offer qualitative support for judgements that reflect potentially gender-biased evaluations of mothers and fathers who have perpetrated infant homicide. This was not unexpected; however, it raises serious concerns about how these individuals may be treated in a social landscape, which although might potentially be underpinned by extant experiences, is shifting away from traditional work and parenting norms (Park et al., Citation2013). A greater number of employed mothers are becoming the breadwinners in their families, while stay-at-home fathering, while rare, is also on the rise (Taylor et al., Citation2010; US Census Bureau, Citation2013). Many countries are also expanding their parental leave to encourage both parents to take time off to care for their child (Duvander & Johansson, Citation2012; Geisler & Kreyenfeld, Citation2019). The amount of time fathers spend with their child has also increased drastically since the 1970s (Sullivan, Citation2010). Similarly, in 2010, Swedish men accounted for 23% of parental leave days taken, a considerable increase from the 0.5% that they accounted for in 1974 (Duvander & Johansson, Citation2012). While men report not taking parental leave due to stigma, a recent survey indicated that roughly two thirds of men would consider resigning their job or taking a lower paid role in order to spend more time with their newborn child (Larbi, Citation2018). The practice and desire of fathers taking more active roles in their childrearing is coming about at a time when paternal perinatal mental health is being recognized as a legitimate issue (Fletcher et al., Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2016). This led to an investigation by the BBC in Scotland, which indicated that there were no standardized or routine check-ins on the mental health of newborns’ fathers (McCaul, Citation2022). Thus, it appears as though societal attitudes toward both mothers’ and fathers’ roles, as measured by reactions to infant homicide cases, reflect traditional perspectives that no longer align with newer, more complex family models (Kalil et al., Citation2014).

The results suggesting that psychopathy was not associated with overall judgements but was a moderator in male judgements of maternal and paternal infant homicide (such that males scoring higher in psychopathy judged Sarah more leniently than Mark) indicates that its role in judgements of infant homicide may be complex and sporadic. This was also evidenced in Peace and Valois (Citation2014), where psychopathy was not directly related to any of the main study outcomes, except that those high in psychopathy were more likely to endorse that a sexual assault victim was making a false allegation when they displayed little emotion in court transcripts. Taken together, the pattern of results indicates that psychopathy likely interacts with other contextual factors in producing judgements. In Peace and Valois (Citation2014), psychopathy emerged as a relevant factor only when the victim in their vignette did not act in a way that is associated with traditional victimhood. In the present study, high levels of psychopathy were associated with male participants treating Sarah – who was portrayed as a loving, albeit frustrated, caregiver – more leniently. In essence, it aligned with traditional maternal tropes. These two studies provide preliminary support that psychopathy may be influential when sociocultural expectations are explicitly met (as in the present study, infant homicide notwithstanding) or unmet (as in Peace & Valois, Citation2014). Indeed, there is evidence that individuals high in psychopathy do make moral judgements, despite some theories indicating that psychopathy is akin to a deficit in making such evaluations (see Borg & Sinnott-Armstrong, Citation2013, for a review). Regardless, it would be remiss to not highlight the disparity between these results and those recently published in similar samples and methodology (Fido et al., Citation2021, Citation2022), which indicate that members of the general population who self-report higher levels of psychopathy report more lenient offence-related judgements. However, owing to these studies focusing on non-contact crimes (i.e. image-based sexual abuse such as so-called revenge pornography) and using qualitatively different measures of psychopathy, it is apparent that more work is required to tease apart this nuance.

Limitations and future directions

As with any study, the current study is not without limitations. The first is that the vignettes, while likely more reflective of actual infant homicide cases, were also comparatively tamer than those found in news coverage of such cases. This makes it difficult to determine whether the same pattern of results would emerge when people are consuming said media. Second, the vignettes presented potential mitigating factors for the offending parents’ actions, such as their lack of sleep and prolonged efforts to soothe their child in more acceptable ways. These details may not be present in media depictions that aim to present infant homicide offenders as callous, negligent or mentally unstable. Third, despite gender role beliefs not being associated with overall judgements, it was clear from the textual analysis that such attitudes played a role in the evaluation of the offenders. It is possible that, similar to rape myths, quantitative measures may not capture some of the subtle ways that gender-biased beliefs are expressed (Zidenberg et al., Citation2022). We also did not explore the potential motives (if any) that may underpin infant homicide, which previous research has suggested may influence responses (Orthwein et al., Citation2010). Finally, despite us having a strong rationale for exploring the role of psychopathic personality traits within our study, we must also acknowledge the potential roles that political beliefs, previous life experiences and broader demographics might play on our judgements of offending behaviour (for example, see Fido & Harper, Citation2020). Sadly, there was not the scope to capture these within the current study.

The present study has also identified a number of avenues for future research. That the mother’s role was identified as a theme in discussion of Mark’s homicide suggests that transcending traditional gender boundaries (with Mark as the caregiver and Sarah as the income-earner) may result in blame being ascribed to parents (i.e. mothers) for abandoning their traditional role. Thus, future studies that explore attitudes toward perpetrators of infant homicide would be wise to measure perceptions of the victim child’s mother more explicitly, even if they were not implicated in their death. As fewer children are living with both biological parents (and children are more likely to be killed by a step-parent; Dawson, Citation2015), it would be worthwhile exploring perceptions of infant homicides in more complex family structures that reflect the makeup of a growing number of family units (Kalil et al., Citation2014). Lastly, given the recent recognition of paternal perinatal mental health struggles, determining its impact in mock juror decision-making could be a fruitful endeavour with potential policy implications.

Impact and conclusion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to empirically test public perceptions of infant homicide among both maternal and paternal perpetrators with and without mental illnesses. This is a particularly timely study given the recent evidence that fathers may be responsible for more infant homicides than previously thought (Home Office, Citation2022). Overall, we found differential effects in judgements as a function of both participant and victim sex that reflect and ascribe gender role beliefs. Psychopathy was also implicated in a limited capacity, further suggesting that it holds a theoretically relevant, albeit complex, role in evaluating perpetrators of violent offences. While further research is needed before any definitive statements can be made, the results of the present study identified a number of mock juror and offender characteristics that may influence judgements of infant homicide. For instance, infant homicide cases were judged as more severe when the perpetrator was the father. Similarly, males higher in psychopathy rendered more lenient judgements toward mothers accused of infant homicide. In addition to jury judgements, this could have implications for arrest and charging decisions among police officers, who are often predominantly male and display psychopathic traits (Falkenbach, Balash, et al., Citation2018; Falkenbach, Glackin, et al., Citation2018; Police.uk, Citation2023). The sexism directed toward the working mother whose husband was accused of infant homicide also suggests that mothers who forgo traditional gender stereotypes may experience stigma and be attributed responsibility for the father’s actions; this could have implications for their personal and professional well-being beyond dealing with the trauma of losing their child and having their responsible spouse incarcerated.

It is hoped that this work will serve as a catalyst for future research in this domain, the volume of which does not currently reflect the relevant situational and characteristic elements (e.g. parent, mental health status) that may influence judgements in potentially typical circumstances, nor the severity and importance that infant homicide plays in society. Further, the present study offers an opportunity to explore the discourse around the media representations of parents who kill their children and how different elements may factor into the public’s judgement of these cases – issues that are particularly relevant when it pertains to juror selection.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Brandon Sparks has declared no conflicts of interest

Katia Vione has declared no conflicts of interest

Dean Fido has declared no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Health, Psychology and Social Care College Research Ethics Committee at the University of Derby (ETH1920-0990) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study and supplementary analyses are openly available via the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/qw6mv/?view_only=82e77a6422cf470e961e660af126fddc

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Excluding cases where no suspect was charged.

References

- Allen, H. (1987). Justice unbalanced. Open University Press.

- Angelone, D. J., Mitchell, D., & Lucente, L. (2012). Predicting perceptions of date rape: An examination of perpetrator motivation, relationship length, and gender role beliefs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(13), 2582–2602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512436385

- Ballinger, A. (2007). Masculinity in the dock: Legal responses to male violence and female retaliation in England and Wales, 1900–1965. Social & Legal Studies, 16(4), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663907082731

- Barnett, B. (2006). Medea in the media: Narrative and myth in newspaper coverage of women who kill their children. Journalism, 7(4), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884906068360

- BBC News. (2018, July 19). Burnley mum’s newborn baby murder conviction quashed. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lancashire-44886357

- BBC News. (2017, June 19). Rachel Tunstill: Mother murdered baby with scissors. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lancashire-40330268

- BBC News. (2021, August 4). Ivi Miley death: Man jailed for killing baby daughter. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-manchester-58089819

- BBC News. (2019, February 6). Burnley mum gets life term for scissors baby murder. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lancashire-47141508

- Beyer, K., McAuliffe Mack, S., & Shelton, J. L. (2008). Investigative analysis of neonaticide: An exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(4), 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854807313410

- Borg, J. S., & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2013). Do psychopaths make moral judgments. In K. A. Kiehl & W. P. Sinnott-Armstrong (Eds.), Handbook on psychopathy and law (pp. 107–128). Oxford University Press.

- Bothamley, S., & Tully, R. J. (2018). Understanding revenge pornography: Public perceptions of revenge pornography and victim blaming. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 10(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-09-2016-0253

- Brennan, K. (2018). Murderous mothers & gentle judges: Paternalism, patriarchy, and infanticide. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism, 30, 139–195.

- Brown, M. J., & Gladstone, N. (2012). Development of a short version of the gender role beliefs scale. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 154–158. bs.20120205.05. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijp

- Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). IRAMUTEQ: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513–518. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2013.2-16

- Cavaglion, G. (2008). Bad, mad or sad? Mothers who kill and press coverage in Israel. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, 4(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659008092332

- Cavaglion, G. (2009). Fathers who kill and press coverage in Israel. Child Abuse Review: Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, 18(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1028

- Cheshire Constabulatory. (2021, August 4). Father of three-month-old girl jailed for 13 years following her death. Cheshire Constabulatory. https://www.cheshire.police.uk/news/cheshire/news/articles/2021/8/father-of-three-month-old-girl-jailed-for-13-years-following-her-death/

- Ciani, A. S. C., & Fontanesi, L. (2012). Mothers who kill their offspring: Testing evolutionary hypothesis in a 110-case Italian sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(6), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.001

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155

- Coughlin, A. (1994). Excusing women. California Law Review, 82(1), 1–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/3480849

- Craig, M. (2004). Perinatal risk factors for neonaticide and infant homicide: Can we identify those at risk? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 97(2), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680409700203

- Crown Prosecution Service. (2021, August 4). Cheshire man jailed for killing his three-month-old baby. Crown Prosecution Service. https://www.cps.gov.uk/mersey-cheshire/news/cheshire-man-jailed-killing-his-three-month-old-baby

- Dawson, M. (2015). Canadian trends in filicide by gender of the accused, 1961–2011. Child Abuse & Neglect, 47, 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.010

- Dobson, C. (2021, August 4). Dad who killed three-month-old daughter after leaving her with ‘catastrophic’ injuries jailed. Manchester Evening News. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/dad-who-killed-three-month-21224606

- Duvander, A. Z., & Johansson, M. (2012). What are the effects of reforms promoting fathers’ parental leave use? Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712440201

- Easteal, P., Bartels, L., Nelson, N., & Holland, K. (2015). How are women who kill portrayed in newspaper media? Connections with social values and the legal system. Women’s Studies International Forum, 51, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2015.04.003

- Edwards, S. S. (1984). Women on trial: A study of the female suspect, defendant and offender in the criminal law and criminal justice system. Manchester University Press.

- Falkenbach, D. M., Balash, J., Tsoukalas, M., Stern, S., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2018). From theoretical to empirical: Considering reflections of psychopathy across the thin blue line. Personality Disorders, 9(5), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000270

- Falkenbach, D. M., Glackin, E., & McKinley, S. (2018). Twigs on the same branch? Identifying personality profiles in police officers using psychopathic personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 76, 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.08.002

- Fido, D., & Harper, C. A. (2020). Non-consensual image-based sexual offending: bridging legal and psychological perspectives. Springer Nature.

- Fido, D., Harper, C. A., Davis, M. A., Petronzi, D., & Worrall, S. (2021). Intrasexual competition as a predictor of women’s judgments of revenge pornography offending. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 33(3), 295–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219894306

- Fido, D., Rao, J., & Harper, C. A. (2022). Celebrity status, sex, and variation in psychopathy predicts judgements of and proclivity to generate and distribute deepfake pornography. Computers in Human Behavior, 129, 107141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107141

- Fletcher, R., Garfield, C. F., & Matthey, S. (2015). Fathers’ perinatal mental health. In J. Milgrom & A. W. Gemmill (Eds.), Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: Evidence-based practice in screening, psychosocial assessment, and management (pp. 165–176). John Wiley & Sons.

- Geisler, E., & Kreyenfeld, M. (2019). Policy reform and fathers’ use of parental leave in Germany: The role of education and workplace characteristics. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718765638

- Gierk, B., Löwe, B., Murray, A. M., & Kohlmann, S. (2018). Assessment of perceived mental health-related stigma: The Stigma-9 Questionnaire (STIG-9). Psychiatry Research, 270, 822–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.026

- Grafton-Green, P. (2019, February 6). Rachel Tunstill: Mother who stabbed newborn baby to death with scissors jailed for life. Evening Standard. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/crime/rachel-tunstill-mother-who-stabbed-newborn-baby-to-death-with-scissors-jailed-for-life-a4059586.html

- Grau, A. B. (2013). The epitome of bad parents: Construction of good and bad parenting, mothering, and fathering in cases of maternal and paternal filicide [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cincinnati.

- Greene, J. D. (2008). The secret joke of Kant’s soul. Moral Psychology, 3, 35–79.

- Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Quinsey, V. L. (1994). Psychopathy as a taxon: Evidence that psychopaths are a discrete class. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.387

- Hartnagel, T. F., & Templeton, L. J. (2012). Emotions about crime and attitudes to punishment. Punishment & Society, 14(4), 452–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474512452519

- Hatters Friedman, S., & Resnick, P. J. (2007). Child murder by mothers: Patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 137–141.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Home Office. (2022). Freedom of information 67810. Author.

- Infanticide Act 1938, c. 36. (1938) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/1-2/36/contents

- Jonason, P. K., Girgis, M., & Milne-Home, J. (2017). The exploitive mating strategy of the Dark Triad traits: Tests of rape-enabling attitudes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 697–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0937-1

- Kalil, A., Ryan, R., & Chor, E. (2014). Time investments in children across family structures. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214528276

- Koons-Witt, B. A., Sevigny, E. L., Burrow, J. D., & Hester, R. (2014). Gender and sentencing outcomes in South Carolina: Examining the interactions with race, age, and offense type. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 25(3), 299–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403412468884

- Kunz, J., & Bahr, S. J. (1996). A profile of parental homicide against children. Journal of Family Violence, 11(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02333422

- Larbi, M. (2018, June 13). Only 2% of new dads are taking paternity leave. Metro. https://metro.co.uk/2018/06/13/dads-want-access-paternity-leave-7626727

- Lewis, C. F., & Bunce, S. C. (2003). Filicidal mothers and the impact of psychosis on maternal filicide. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 31(4), 459–470.

- Little, J. (2021). Filicide, journalism and the ‘disempowered man’ in three Australian cases 2010–2016. Journalism, 22(6), 1450–1466. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918809739

- Little, J., & Tyson, D. (2017). Filicide in Australian media and culture. In H. N. Pontell (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 1–24). Oxford University Press.

- Malinen, S., Willis, G. M., & Johnston, L. (2014). Might informative media reporting of sexual offending influence community members’ attitudes towards sex offenders? Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(6), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2013.793770

- Maroño, A., & Bartels, R. M. (2020). Examining the judgments of pedophiles in relation to a non-sexual offense. Psychology, Crime & Law, 26(9), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1742339

- McCaul, S. (2022, February 10). Post-natal depression in men: ‘The darkest time of my life.’ BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-60319568

- Morissey, B. (2003). When women kill: Questions of agency and subjectivity. Routledge.

- Moseley, K. L. (1986). The history of infanticide in Western society. Issues in Law & Medicine, 1(5), 345–361.

- Motz, A. (2016). The psychology of female violence: Crimes against the body. Routledge.

- Nagel, I. H., & Johnson, B. L. (1994). The role of gender in a structured sentencing system: Equal treatment of female offenders under the United States sentencing guidelines. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), 85(1), 181–221. https://doi.org/10.2307/1144116

- Naylor, B. (2001). The ‘bad mother’ in media and legal texts. Social Semiotics, 11(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330120018292

- Ochs, E. (1993). Constructing social identity: A language socialization perspective. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 26(3), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi2603_3

- Office of National Statistics. (2021). Homicide in England and Wales: Year ending March 2020.

- Orthwein, J., Packman, W., Jackson, R., & Bongar, B. (2010). Filicide: gender bias in California defense attorneys’ perception of motive and defense strategies. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 17(4), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710903566987

- Park, A., Bryson, C., Clery, E., Curtice, J., & Phillips, M. (2013). British social attitudes: The 30th report. National Center for Social Research.

- Peace, K. A., & Valois, R. L. (2014). Trials and tribulations: Psychopathic traits, emotion, and decision-making in an ambiguous case of sexual assault. Psychology, 05(10), 1239–1253. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.510136

- Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

- Police.uk. (2023). Workforce diversity in Metropolitan Police Service. Police.uk. https://www.police.uk/pu/your-area/metropolitan-police-service/performance/workforce-diversity/

- Poteyeva, M., & Leigey, M. (2018). An examination of the mental health and negative life events of women who killed their children. Social Sciences, 7(9), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090168

- Pritchard, C., Davey, J., & Williams, R. (2013). Who kills children? Re-examining the evidence. British Journal of Social Work, 43(7), 1403–1438. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs051

- Rapaport, E. (2005). Mad women and desperate girls: Infanticide and child murder in law and myth. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 33, 527–570.

- Ratinaud, P. (2009). Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires. IRaMuTeQ. http://www.iramuteq.org.

- Reidy, D. E., Kearns, M. C., DeGue, S., Lilienfeld, S. O., Massetti, G., & Kiehl, K. A. (2015). Why psychopathy matters: Implications for public health and violence prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.018

- Resnick, P. J. (1969). Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126(10), 1414–1420. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.126.3.325

- Rock, K. (2020). A decade of maternal filicide in Canadian news: An ethnographic content analysis [master’s thesis]. Athabasca University.

- Rodger, J. (2019, February 6). Mum Rachel Tunstill found guilty of murdering newborn baby with scissors after retrial. Birmingham Mail. https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/midlands-news/mum-rachel-tunstill-found-guilty-15786840

- Saavedra, L., & Cameira, M. (2018). Deconstructing idealized motherhood: the extreme case of neonaticidal women. Feminist Criminology, 13(5), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085116688779

- Sandoval, J. R. (2021). Impact of gender role attitudes on punitive judgments and perceived mental illness in maternal versus paternal filicide (Doctoral dissertation). Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

- Shelton, J. L., Corey, T., Donaldson, W. H., & Dennison, E. H. (2011). Neonaticide: A comprehensive review of investigative and pathologic aspects of 55 cases. Journal of Family Violence, 26(4), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9362-8

- Sorenson, S. B., & Peterson, J. G. (1994). Traumatic child death and documented maltreatment history, Los Angeles. American Journal of Public Health, 84(4), 623–627. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.84.4.623

- Spiranovic, C. A., Roberts, L. D., & Indermaur, D. (2012). What predicts punitiveness? An examination of predictors of punitive attitudes towards offenders in Australia. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 19(2), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2011.561766

- Stangle, H. L. (2008). Murderous Madonna: Femininity, violence, and the myth of postpartum mental disorder in cases of maternal infanticide and filicide. William & Mary Law Review, 50, 699–734.

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

- Stöckl, H., Dekel, B., Morris-Gehring, A., Watts, C., & Abrahams, N. (2017). Child homicide perpetrators worldwide: A systematic review. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 1(1), e000112. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000112

- Sullivan, O. (2010). Changing differences by educational attainment in fathers’ domestic labour and child care. Sociology, 44(4), 716–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510369351

- Takamatsu, R. (2018). Turning off the empathy switch: Lower empathic concern for the victim leads to utilitarian choices of action. PloS One, 13(9), e0203826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203826

- Taylor, P., Fry, R., Cohn, D., Wang, W., Velasco, G., & Dockterman, D. (2010). Women, men and the new economics of marriage. Pew Research Center.

- Tuncer, A. E., Broers, N. J., Ergin, M., & de Ruiter, C. (2018). The association of gender role attitudes and offense type with public punitiveness toward male and female offenders. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 55, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.10.002

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Current population survey, America’s families and living arrangements. U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/cps2012.html

- Viding, E., & McCrory, E. (2019). Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. The Lancet: Psychiatry, 6(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30049-5

- Wilczynski, A. (1991). Images of women who kill their infants: The mad and the bad. Women & Criminal Justice, 2(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J012v02n02_05

- Wong, O., Nguyen, T., Thomas, N., Thomson‐Salo, F., Handrinos, D., & Judd, F. (2016). Perinatal mental health: Fathers–the (mostly) forgotten parent. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry : Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists, 8(4), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12204

- Yin, X., Hong, Z., Zheng, Y., & Ni, Y. (2022). Effect of subclinical depression on moral judgment dilemmas: a process dissociation approach. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 20065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24473-2

- Zidenberg, A. M., Wielinga, F., Sparks, B., Margeotes, K., & Harkins, L. (2022). Lost in translation: A quantitative and qualitative comparison of rape myth acceptance. Psychology, Crime & Law, 28(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1905810