Abstract

In an ageing world with a growing prevalence of neurodegenerative disease and recent voluntary assisted dying laws in New Zealand and several Australian states, healthcare professionals are increasingly being relied upon to conduct decision-making capacity (DMC) assessments. There is no legislation in New Zealand or Australia to provide clear guidance on conducting DMC assessments. This systematised review aimed to examine the current processes, issues and debates within DMC assessments as detailed in Australasian literature. Six databases were searched: CINAHL, Scopus, Embase, Medline, PsycINFO and Google Scholar following PRISMA guidelines. A total of 33 articles were included in the review and, following a quality assessment, an inductive approach was used to determine key topics which were synthesised in the review. Five distinct issues were revealed, namely a lack of standardisation and guidelines in approaching DMC assessments, training and knowledge of DMC, professional roles, medical and psychiatric complexities and the medico-legal interface.

Introduction

Decision-making capacity (DMC) is the ability of an individual to make a specific decision (Moye & Marson, Citation2007) as judged by a physician or other healthcare professional. Prior to receiving treatment, informed consent must be obtained from patients. Consent is only deemed valid when accurate information has been provided to a competent patient who then makes a voluntary choice (Appelbaum, Citation2007). Therefore, an important step in the provision of healthcare is ensuring a patient has the capacity to make the decision to provide consent for that treatment (Raymont, Citation2002; Raymont et al., Citation2007).

The world’s population is ageing (Usher & Stapleton, Citation2020), and Australia and New Zealand (NZ) are no exception. With greater ageing populations there is a corresponding increase in the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia, in older adults. Neurodegenerative diseases are often linked to increased difficulties in everyday functioning, including the ability to make decisions, leading to an increased need to assess DMC (Moye & Marson, Citation2007). Assessment of DMC is also a requirement for an individual requesting voluntary assisted dying (VAD), which has recently become legal in New Zealand and some Australian states (Cheung et al., Citation2022). Healthcare professionals in New Zealand and Australia are therefore increasingly being relied upon to conduct DMC assessments.

Assessing DMC is often complex and requires both clinical and ethical knowledge (Kane et al., Citation2022). Healthcare professionals conducting these assessments must have the skills required to balance respect for the autonomy of people who have capacity, while protecting those who lack capacity or require support for decision-making (Appelbaum, Citation2007). A person who has capacity is able to make whatever health decisions they like, even decisions that may be deemed imprudent or unwise by a healthcare professional. A person is also entitled to refuse or withdraw from treatment at any time, so determining their DMC is essential prior to treatment occurring. However, for a person to require a DMC assessment a trigger should have been identified prior to a request or referral (Parmar et al., Citation2015). Triggers for an assessment can be broad and can occur in a range of circumstances including brain injury, substance abuse or misuse, dementia and/or delirium, or mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or depression (Birchley et al., Citation2016; Candia & Barba, Citation2011).

The assessment of DMC spans across disciplines and involves knowledge of the law, ethics and a range of medical issues (Moye & Marson, Citation2007). As ratifying nations of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), both Australia and NZ must fulfil their commitment and adhere to all requirements of the Convention (United Nations, n.d.). Of relevance for DMC, this entails following Article 12, which states that ‘persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life’ (CRPD, n.d.). While not invalidating the need for assessing DMC, it undoubtedly increases the complexity of this already challenging concept. Additionally, when an individual is deemed to not have DMC there are significant medio-legal consequences for them and their family. Given the complexity and potential implications, it is critical that those assessing DMC are well trained and confident in conducting the assessments. However, it appears that DMC assessments are not being conducted with the rigour, validity and reliability that is arguably warranted. A systematic review of tools found as many as 19 different instruments are available for healthcare practitioners to use in the assessment of DMC (Lamont et al., Citation2013). Each of these instruments has some limitations across the domains they assess, their ease of use or their validity and reliability. In addition, studies frequently comment on the lack of formal training available to healthcare professionals conducting capacity assessments (Scott et al., Citation2020; Usher & Stapleton, Citation2022).

Given the ageing population, recently legalised VAD laws and the considerable complexity of conducting DMC assessments, it is important to shed light on how they are currently being done and the knowledge and skills of the professionals involved in the assessments. Hence the current review. A similar review was conducted in the UK (Jayes et al., Citation2020), but the assessment of DMC in the UK is guided by the Mental Capacity Act (2005), which provides a legislative framework and assessment principles. Without such legislation in Australasia the assessment approach is likely to vary considerably, and it is important to understand this issue at a local level. This review aims to answer the following questions: What can be learnt from the research about how DMC has been assessed in New Zealand and Australia? And what issues exist within the assessment of an individual’s DMC?

Method

There were a number of possible forms this literature review could have taken. A systematised review was deemed most appropriate because it includes many elements of a systematic review process (i.e. a detailed search, followed by appraisal and synthesis of the findings), but not all authors were available to independently review all articles, so it was not fully systematic. We applied additional rigour (by employing an independent reviewer during the quality review stage) as we sought to examine the current processes, issues and debates within DMC assessments.

Stage 1: developing the search criteria

The search criteria were developed with the guidance of a subject-specific university librarian and reviewed through a consultation process with all authors. The terms ‘decision-making’, ‘capacity’ or ‘competence’ were used, alongside ‘assess’ or ‘measure’. shows the details of the search criteria for each database. The search was undertaken for relevant empirical peer-reviewed and non-empirical grey literature across six databases: PsycInfo, Embase, Medline, Scopus, CINAHL and Google Scholar. No date range exclusions were applied. Additional literature was gathered from experts in the field and a hand search of the reference lists of included articles.

Table 1. Database search criteria.

Stage 2: screening of research

The first author reviewed all returned articles for any duplications and screened the title and abstract of the unique articles. All research on DMC assessments (at least in part) within New Zealand or Australia were included unless they met any of the following exclusion criteria: research conducted entirely outside of the two regions; research only about non-healthcare-related capacity (e.g. returning to work, testamentary); research on children and youth (i.e. under 18 years of age); research on DMC solely within the context of Mental Health Acts; and languages other than English. While not required for a systematised review, it was decided that 25% of the selected articles (at the title and abstract stage) would be reviewed by the second author to confirm agreement of the included and excluded articles. There were no disagreements between the two authors. The first author then reviewed all articles in full to decide on meeting the criteria outlined above. Next, all the articles deemed suitable by the first author were checked by the second author to ensure they met the eligibility criteria. A meeting was held with all four authors to revise the selection until a consensus was reached on all articles to include. Initially, literature reviews were included in the search of studies but subsequently excluded because the studies that formed a part of those reviews were not subject to the same country-specific inclusion criterion as the current study. The literature search was conducted in late 2021; the search was replicated using the exact same criteria in January 2023 to search for any additional articles that had been added to each database since the last search. Google Scholar does not allow searching by date added so the search for this database was repeated exactly as before from 2021 onwards. The replicated search in January 2023 returned a total of seven additional articles that met the criteria at abstract level. Following screening of the full articles by N.M. and C.M.C., five of the seven met the inclusion criteria and have been included as ‘late additions’ in the PRIMSA diagram.

Stage 3: synthesis of topics covered in publications

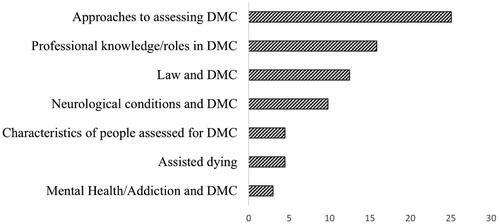

Using an inductive approach to determine the main topics reported in the literature on DMC assessments, shows the frequency of each topic appearing across the articles. Approaches to assessing DMC was the most commonly discussed topic, appearing in 76% of articles. Around 48% of articles discussed professional involvement in DMC assessments, in particular exploring their knowledge or the role different professions play in these assessments. Given the legal implications of DMC assessment, legal issues were discussed in nearly half of all publications. Characteristics of the individuals requiring a capacity assessment was not a topic that many publications were dedicated to. Although assisted dying is becoming more prevalent in recent literature, this topic was covered in an article as far back as 2010, despite this being illegal in Australia and New Zealand at the time.

Results

Summary of literature

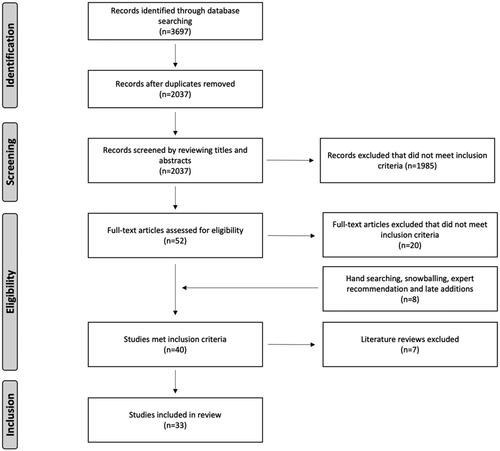

As illustrated in , database searches resulted in 3697 records, with 2037 unique records after duplicates were removed. The screening of titles and abstracts removed a further 1985 records, leaving 52 to be read in full to determine eligibility. After a full text screen, 20 articles were found to not meet eligibility criteria. Three further articles were found through additional sources, and three articles were included from the replicated search in January 2023, resulting in 38 relevant articles. Literature reviews were then excluded at this stage (five of the 38 were literature reviews), leaving 33 articles to be included in the systematised review.

Quality review of literature

Of the 33 articles included in the review (), 17 were empirical peer-reviewed studies, and 16 were non-empirical studies made up of opinion pieces, articles and case studies. The 17 empirical articles were reviewed for quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Version 2018; Hong et al., Citation2018). The MMAT is a critical appraisal tool allowing for the review of mixed empirical studies through assessment of specific criteria appropriate for the methodology of the study. The empirical studies that met all of the appraised criteria achieved a score of 100%, whereas a study that did not meet all the assessed criteria received a lower score representing the proportion of criteria that were met (see ). N.M. completed the quality review process, and then a neutral reviewer (who was blind to N.M.’s review but familiar with this subject) carried out an independent review. C.M.C. then reviewed both of the quality assessments and reconciled the two disagreements that had occurred between N.M. and the independent reviewer.

Table 2. Empirical literature from search of DMC assessment articles.

Characteristics of publications

describes the characteristics of the 17 empirical publications along with the quality review score. provides the characteristics of the 17 non-empirical publications and the contributions they have made to the body of literature. As reported above, no date restrictions were applied to the database searches. Interestingly, the earliest eligible article on the assessment of DMC was in 2001, and there was a substantial increase in the number of publications on this topic from 2014.

Table 3. Non-empirical literature from search of DMC assessment articles.

Discussion

This discussion follows the evolution of approaches to DMC assessment over the time period of the review as well as the issues still present in how assessments are approached today. This is followed by a detailed discussion of four further issues and how they impact on the process of conducting a DMC assessment: namely, training and knowledge of DMC, professional roles, medical and psychiatric complexities and the medico-legal interface. Above all the issues and debates that surround DMC assessments, there is a constant and unanimously expressed concern among healthcare professionals and lawyers to ensure a balance between respecting an individual’s personal choice and autonomy, and the duty of care to protect them when they may be lacking in DMC or refusing treatment (Mullaly et al., Citation2007; Restifo, Citation2013). Ultimately, it is agreed that DMC exists as the central determinant when deciding how to balance respect for the individual’s right to choose and not overriding this right to provide a duty of care (Restifo, Citation2013). This discussion begins by answering the first question: ‘what can be learnt from the research about how DMC has been assessed in New Zealand and Australia?’

The evolution of approaches to DMC assessment

Before 2010

Biegler and Stewart (Citation2001) recognised the importance of including formalised testing as part of DMC assessments. They discussed the inclusion of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., Citation1975) but argued it should only be used as a screening tool given that it is limited to measuring cognition and is not synonymous with capacity. The fastest and more valid approach for assessing capacity was argued to be a series of simple questions covering understanding, appreciation, weighing and choice. On completion of the assessment Biegler and Stewart believed that the findings should be documented in patient health records, clearly stating whether the individual is competent or not, with a justification for that decision.

Young (Citation2004) who used competence and capacity interchangeably, defined competence as ‘the ability to make an autonomous, informed decision that is consistent with the person’s lifestyle and attitudes, and to take the necessary action to put this decision into effect’ (p. 41). Importantly, he highlighted that a compelling reason is required to doubt an individual’s capacity and conduct a DMC assessment. Young proposed a procedure for assessing competence that consists of asking eight questions as part of an interview. His argument was that by following this procedure the assessing doctor should be able to determine whether the individual is competent to make the decision.

Mullaly et al. (Citation2007) examined the approaches used by neuropsychologists and found that a variety of methods were being implemented. Almost all included history-taking and a file review, but there was variation in the assessment approach taken, with just over two thirds including a semi-structured interview, only a third interviewing family member(s) and just over two thirds discussing it with their team. The majority (83%) used standardised tests, but on closer inspection it was clear that a broad range of tests were being used. The authors did find agreement, with the majority of neuropsychologists stating that assessing DMC is challenging and time consuming, and the majority wrote up their findings into a formal report. Mullaly et al. argued that an approach that is too formulaic is unlikely to be appropriate when assessing the nuances within an individual case. They also recognised the potential for neuropyschological assessments to add further complexity due to the potential for conflicting and competing information that can arise from different assessment tasks and interview answers.

The variation seen between clinical assessors and legal decision-makers was raised as a cause for concern by Parker (Citation2008) who undertook a case series review and found that there was no set framework being consistently followed by assessors of DMC. Most prominent was the use of what Parker (Citation2008) called psychometric testing ‘such as the MMSE’ (p. 31) and clinical interviews, with psychologists more commonly including formal testing: however, the variance seen among assessors was considerable. Parker highlighted the weakness of an interview for assessing DMC, citing subjectivity and lack of reliability that is involved. Overall, he argued that the key issues facing DMC assessments are time, efficiency and education but a standardised combination of interviewing and testing would be superior to the ‘random’ approach currently being implemented.

2010–2015

In 2010 it was recognised that the approach to assessing a person’s DMC must consider the balance between respecting an individual’s autonomy and overriding this autonomy to provide a duty of care in situations where capacity is not present (Darzins, Citation2010). Historically, Darzins (Citation2010) argued, medical practitioners prioritised what they deemed to be best in their duty of care, sometimes overriding autonomy, which could be causing harm. However, the patients’ active participation in their healthcare had been steadily increasing in the preceding years (Mullaly et al., Citation2007).

Astell et al. (Citation2013) added to the earlier argument that attempts have been made to standardise capacity assessments in the hope of improving the inter-rater reliability of structured tools such as the Aid to Capacity Evaluation and MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (MacCAT; Grisso et al., Citation1997). However, due to limitations of these tools (e.g. the scenarios used being hypothetical), Astell et al. questioned their clinical applicability and concluded that using a semi-structured clinical interview may be the best approach. This discussion was echoed by Restifo (Citation2013), who argued that standardising DMC assessments through the use of instruments limits the flexibility to explore specific nuanced situations and can increase stress and performance anxiety for the individual being assessed.

Consistency and transparency were argued by Purser and Rosenfeld (Citation2014) to be important factors for DMC assessment, noting the potential significant legal implications and consequences of an individual’s rights if a person is deemed to not have capacity. However, as argued by Purser and Rosenfeld (Citation2014, Citation2015), the current approaches were still unsatisfactory, as they relied on an ad hoc implementation of assessment methods modified by the individual practitioner to suit their personal knowledge and skill level. The lack of a ‘gold standard’ assessment tool and modifications being made by practitioners called into question the rigour of the overall capacity assessment process. Purser and Rosenfeld (Citation2014) argued that this variability in approach may mean that the outcome of a person’s DMC assessment could be determined by who administers the assessment rather than the individual’s own decision-making abilities.

Purser et al. (Citation2015) supported this argument, highlighting that there was no formally recognised standard for assessing DMC in Australia. As a result, DMC assessments continued to be conducted in an ad hoc manner, relying on the skill level of the assessor, with the variety of tests and tools available to an assessor further adding to these inconsistencies. While recognising the challenges in creating a clinical assessment tool, they suggested that, as a minimum, a nationally recognised set of guidelines should be created to underpin DMC assessment. A standard guideline was argued to help improve consistency of approach whilst balancing the need for flexibility.

2016 to present

It appears that little has changed since Parker’s (Citation2008) research and suggestions. Young et al. (Citation2018) conducted a survey among hospital doctors and General Practitioners (GPs) in New Zealand to understand what they knew about assessing DMC. The authors found that a wide range of approaches to DMC assessment were being utilised. Only 6% of hospital doctors and 16% of GPs stated that they used a capacity assessment protocol in their assessments, with 9% of hospital doctors stating they assess DMC based on informal general discussion and intuition. They highlighted the need for any future training to include a more standardised approach or toolkit. Newton-Howes et al. (Citation2019) added that across New Zealand, doctors and other healthcare professionals determine a patient’s decision-making abilities on a daily basis. Their determination was sometimes a result of intuition or from assessments that were not specifically discussed with the patient.

Kiriaev et al. (Citation2018) considered DMC assessments within the context of advanced care planning. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the MMSE and scores on Trail Making Tests A and B for the group of participants found to be competent and those found to be non-competent. They highlighted the complexity of DMC assessments stating that they do not easily lend themselves to a straightforward ‘screening methodology’ and concluded that these tools cannot be reliably used to differentiate individuals with and without capacity. The authors argued that the complexity of DMC assessments means that a degree of clinical judgement is likely to be required. However, they state that a lack of any standardised approach or methodology will impact inter-rater reliability and the quality of assessments leading to a wide range of approaches. They concluded that clinicians should be routinely discussing and explaining advanced care planning to older patients to ensure that they fully understand it before engaging in the planning itself. This was supported by John et al. (Citation2020) who found that the very people most likely to require a DMC assessment were those without any advanced care plan, in the form of enduring power of attorney, enduring guardian or advanced care directives.

Newton-Howes et al. (Citation2019) proposed that authenticity, described as an individual’s values as reflected in their choices, is a fundamental component to be included in DMC assessment. They recognised that this goes beyond a standard approach, which can emphasise the avoidance of making value judgements. The standard assessment will tend to focus on the process of decision-making while the content of the decision is not a direct consideration. Their argument was that this approach failed to include the significance of a person acting on their own values and beliefs. Further to this, Newton-Howes et al. discussed situations where a patient refuses medical treatment that is viewed by most to be clearly in their best interests. They argued that the DMC would be held to a different standard than for a patient who agreed to the treatment, creating an imbalance, whereby a patient’s autonomy is much more likely to be considered intact only if it reflected the normative perspective.

Several recent studies have looked at approaches to capacity assessment with Lamont et al. (Citation2019) conducting a survey among healthcare practitioners working in a hospital in New South Wales. They found considerable variance in approach among those conducting capacity assessments. Only 31% used a capacity assessment tool, and 52% used a cognitive screening tool. Interestingly, 77% of those conducting DMC assessments selected professional judgement as part of how they assessed DMC, which suggests that the remaining 23% are relying purely on results of the tools. Given that some are not using tools at all, this is problematic because it suggests that in some cases entirely different approaches are being used. Vara et al. (Citation2020) undertook qualitative interviews with GPs who conduct DMC assessments and found some agreement in approaches with all 12 GPs stating that they would involve family members or other sources of collateral information to determine capacity. In addition, 10 of the 12 GPs mentioned that they use cognitive testing as part of the assessment. However, variation was found in the weight each GP placed on cognitive testing with some misunderstanding of the ability of testing to determine the presence/absence of capacity. Many GPs stated that they wish to learn a standardised approach to help simplify the process of DMC assessments.

Logan et al. (Citation2020) conducted a retrospective case audit for patients referred for a DMC assessment at a hospital in Australia. The assessments were all conducted by a consultant geriatrician. Detail was not provided about all the tools used, but the authors commented that the decision-making tools varied. This is surprising given that all were conducted by the same profession. Logan et al. highlighted the importance of DMC being presumed to be intact (even with a diagnosis of dementia) and the need to approach DMC assessments as decision-specific and not a representation of global decision-making abilities. Connolly and Peisah (Citation2022) retrospectively analysed case notes of inpatients referred for guardianship applications in Australia and found that 33% of cases had no evidence of a DMC assessment. Further thematic analysis highlighted issues of delays and uncertainties with DMC assessments among healthcare professionals. Of those who did have a documented DMC assessment, a consultant geriatrician was the most common profession undertaking them (80%). Overall the authors argued there is still a great deal to be done in this space including education to target DMC assessment.

We can now turn to our second research question (namely ‘what issues exist within the assessment of an individual’s DMC?’). It is evident that our understanding of DMC and approaches to assessment has come a long way since Biegler and Stewart’s commentary in 2001. However, more recent research suggests that distinct issues still exist, namely a lack of standardisation and guidelines on conducting DMC assessments. We discuss this, along with the other issues that were found in this review, around training and knowledge of DMC, professional roles, medical and psychiatric complexities and the medico-legal interface, which this review now discusses in detail.

Training and knowledge of DMC assessment among healthcare professionals

Parker (Citation2008) highlighted that a key issue in DMC assessments is the deficiency in DMC assessment training. He discussed this in the context of the ageing populations of Australia and New Zealand and the increasing frequency that doctors, and other healthcare professionals, are being called upon to conduct such assessments. The argument by Parker was that capacity assessments should be regarded as a fundamental critical skill to be mastered by all doctors and should demand equal educational attention to that for other skills (e.g. examining the cardiovascular system). This was supported in an earlier study by Mullaly et al. (Citation2007) who surveyed neuropsychologists and found that only 8% agreed with the statement ‘my training prepared me well for carrying out DMC assessments’. These early findings have been consistently supported in the continued research on DMC assessments.

Astell et al. (Citation2013) commented that training for medical and nursing professionals does not usually include information on how to conduct DMC assessments, leaving many professionals lacking the knowledge needed to conduct them despite this task being part of their scope of practice. Purser and Rosenfeld (Citation2015) furthered this, stating that education is needed for both legal and medical practitioners on the various assessment models and approaches.

More recently, studies have looked specifically at the training and knowledge among healthcare professionals who conduct DMC assessments. Young et al. (Citation2018) found key areas of knowledge lacking in their survey among hospital doctors and GPs, with 18% of hospital doctors and 19% of GPs incorrectly answering the question on what to do when a patient lacks capacity, stating they could get consent from the next of kin. In addition, 33% of hospital doctors and 54% of GPs were unaware that DMC assessments are decision-specific and cannot be generalised to other decisions. It was commonly reported by both hospital doctors and GPs that a lack of knowledge and skill in doing DMC assessments was an issue alongside uncertainty with legal aspects and difficulty in more complex cases. A third of doctors surveyed stated that they did not feel sufficiently confident in their ability to do a DMC assessment such that it would stand up in court. Agreement was seen in both hospital doctors and GPs in favour of further training in the form of short courses, online protocols, tutorials or teaching sessions.

In a cross-sectional survey with healthcare workers in a hospital setting, Lamont et al. (Citation2019) found that less than a quarter of respondents were able to identify the three legal elements to a DMC assessment, while just over a quarter were not able to identify any. Over a third thought that patient consent was only required for specific, more invasive treatments. They concluded overall that there appears to be a substandard level of knowledge and understanding of DMC assessments, legislative frameworks and that consent is a legal construct.

A recent qualitative study by Vara et al. (Citation2020) found that none of the GPs who were interviewed received training on DMC assessments as part of their pre-registration studies; instead training was purely on-the-job through peers or attendance at conferences. Most participants reported a lack of confidence in conducting these assessments. Answers to the interview questions showed greater focus on the legal requirements of capacity than the four abilities that are required during an assessment. GPs also expressed a lack of knowledge with the legal requirements. In a similar study in Australia, Alam et al. (Citation2022) interviewed GPs around advance care planning. They found a common theme in that GPs struggled with assessing capacity in dementia with difficulty knowing whether a patient with dementia was competent or not. Vara et al. went a step further to understand what is needed to help GPs in this area and found that further training was required primarily in the form of blended trainings such as e-learning, webinars and face-to-face training. Vara et al. concluded by highlighting the critical nature of DMC assessments in an ageing world that will see healthcare workers increasingly encountering DMC assessments. They argued that DMC assessments are complex, and there is a need to develop specific training with resources and a curriculum to help improve GPs’ knowledge and confidence, thereby improving the quality of these assessments.

Professional roles in DMC assessments

Medical practitioner roles

One of the key issues commonly debated in the literature is who is best placed to conduct these assessments. In the earliest local article found on DMC assessments, Biegler and Stewart (Citation2001) argued that the treating doctor is the best person to conduct the capacity assessment given their knowledge of the likely consequences of treatment refusal and potential factors that may be present to impair competence. However, Parker (Citation2008) argued that if the person providing the treatment is also the person conducting the assessment there is a conflict of interest. Young (Citation2004) argued that an individual’s ‘regular doctor’ is in the best position to assess DMC given they would also have the best chance of convincing the courts to approve the necessary intervention. However, he argued that all doctors should have an understanding of the concept of competence, and when there are suspected complexities, a specialist practitioner may be useful to include.

Within the New Zealand context, it has historically been the responsibility of psychiatrists to conduct DMC assessments; however, with the number of capacity assessments growing, both geriatricians and GPs have been increasingly performing them (Astell et al., Citation2013; Young et al., Citation2018). GPs often have the closest relationships and most knowledge about the views and medical conditions of the patient, but they lack the time required to do these assessments in full (Astell et al., Citation2013). Despite this, Astell et al. (Citation2013) found that the majority of DMC assessments were being performed by GPs, usually after a request for a medical certificate by a family lawyer due to family concerns of capacity. They argued that the ease of access that patients have to their GP means a reduction in the wait time to see a specialist, and a referral to a specialist is only required in more complex cases where there may be neglect or abuse.

Barry and Lonie (Citation2014) argued that medical practitioners may be no better placed than solicitors to conduct capacity assessments, citing a lack of knowledge of both the legal and cognitive tests as well as the functional implications of the assessment in the medical field. They acknowledged the consistency in the conceptual framework of assessing capacity but given the variation in context that capacity issues emerge, differing clinical skill sets are required. It was argued that experience with the particular medical issues that the patient presents with is the most important, alongside training and skills to conduct the assessment.

Ambiguity was also found in the study by Young et al. (Citation2018) with 24% of GPs and 30% of hospital doctors believing that responsibility for conducting DMC assessments did not necessarily sit with them. Some resident hospital doctors were unsure whether they were even permitted to assess capacity. Reasons for this included not knowing the patient well enough, potential conflicts of interests due to family dynamics and the potential for an adverse finding to compromise the relationship with the patient and the family. Concerns were also raised about being the sole person responsible for an assessment and the potential legal implications. Conversely, qualitative interviews conducted by Vara et al. (Citation2020) found that most GPs acknowledged responsibility for conducting DMC assessment, with their long-established relationships with their patients putting them in a suitable position to conduct these assessments. For more complex cases a referral to a specialist might be required; however, these services can be hard to access, especially for those working rurally.

Neuropsychologists

Mullaly et al. (Citation2007) found that 71% of the neuropsychologists involved in DMC assessment agreed with the statement ‘Neuropsychology is ideally suited for assessing decision-making capacity’ (p. 184). In contexts where neuropsychologists are involved it appears their work is highly valued with 98% of survey participants agreeing with the statement ‘The role that the neuropsychologist plays in assessing decision-making capacity in my work setting is valued’ (p. 184). However, Mullaly et al. recognised that the absence of a standardised model to predict DMC presents a challenge for neuropsychologists.

Barry and Lonie (Citation2014) argued that geriatric neuropsychology is uniquely positioned to provide objective assessment of a person’s cognitive ability. The combination of knowledge of progressive neurological disorders and sound training and skills in the administration and interpretation of neuropsychological tests allows for a comprehensive assessment that probes deeper into the likely required legal areas. This was supported by Snow and Fleming (Citation2014), who discussed a case study of a woman who refused lifesaving surgery due to the cultural implications of a scar on her neck, concerns about voice changes and the need for lifelong medication as a result. Although she held an alternative viewpoint, every practitioner regarded her to be competent to make the decision. A neuropsychologist was enlisted to provide formal documentation of her capacity prior to discharge. To everyone’s surprise the neuropsychological assessment found the woman to be impaired in aspects of her executive function and did not possess the ability to weigh up the risks and benefits with underlying cognitive impairment. In this situation the legal counsel considered neuropsychology to be the most relevant expert opinion in competence assessment (Snow & Fleming, Citation2014).

Occupational therapists

Darzins (Citation2010) discussed the role of occupational therapists (OTs) in DMC assessment, with their unique position allowing them to make important contributions when discussing a patient’s return home. If specific personal care risks are identified in the assessment but dismissed by the patient, it needs to be determined whether they have the DMC to choose to live with those risks. In 2013, a dedicated Decision-Making Capacity Assessment Support role for OTs was established in a large metropolitan hospital in Australia to facilitate their contribution to DMC assessment (Matus et al., Citation2020). The authors interviewed a range of OTs who had accessed this support role over a period of six months. All 12 OTs reported positive experiences with the DMC assessment support role as it facilitated their on-the-job learning by providing a structured journey of learning, tailored guidance and fostering a supportive learning environment. Prior to engaging with the support role many OTs stated they had little to no knowledge of DMC assessments, felt inadequately prepared to perform the role (which was described as complex and challenging) and reported that without this role there was a lack of support, resources and information to assist in their learning. Additionally, Matus et al. found that the interaction with the support role varied depending on the appreciation each OT had for the seriousness of DMC assessments and the value they placed on their own contribution to the management of these cases.

Speech-language therapists

Aldous et al. (Citation2014) explored the practices of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) involved in DMC assessments with patients who have aphasia or related neurogenic communication disorders. Their study found that 86% of the SLPs surveyed had been involved in a DMC assessment but the majority said this aspect of their role took up less than 10% of their time, suggesting it is not something they are doing with much frequency. Aldous et al. argued that as our understanding of the relationship between cognitive functioning and verbal communication has developed, DMC assessments have become more complex, requiring greater input from different medical and allied health professionals. They noted that the involvement of SLPs is required across a wide range of diagnoses with the varying characteristics of the decisions that patients were needing to make. A requirement of further training and guidance were again highlighted by the SLPs working in this space.

Wider team involvement and consultation

In a case review by Parker (Citation2008) it was found that 44% of DMC assessments involved more than one healthcare professional. Interestingly, 29% of those were found to disagree on whether the patient either had or lacked capacity. Parker argued that it is understandable for disagreements to arise in complex, borderline cases due to uncertainties around different cognitive function. However, this highlights the importance of consultation with a range of healthcare professionals. In their audit review (over a 30-month period) Logan et al. (Citation2020) found that of the 98 patients referred for a capacity assessment, 41% were referred by doctors, 19% by social workers and 16% by OTs. The roles that different healthcare professionals play in DMC assessment are not well defined, but as highlighted by Logan et al., OTs and social workers are playing a particular role in identifying the need for an individual to have a DMC assessment and often making a referral for this to occur. This suggests that knowledge of DMC assessment is likely to be required by a range of healthcare professionals (even if they are not conducting the assessment themselves).

Medical and psychiatric complexities in DMC assessment

Capacity is a variable and complex construct to measure (Purser et al., Citation2015) even for the more straightforward presentations. However, more complex presentations are common and require additional time and attention to determine DMC. The section below is not an exhaustive list but summarises the issues at play outside of the standard assessment process, as reported in the 33 articles included in this literature review.

Dementia

A diagnosis of dementia can often be a trigger for people requiring the services of a lawyer to put their affairs in order (Barry & Lonie, Citation2014). Importantly, a diagnosis of dementia does not provide sole evidence that a person lacks capacity (Astell et al., Citation2013; Barry & Lonie, Citation2014; Logan et al., Citation2020) because initially its impact can be mild, and the illness has broad manifestations (Logan et al., Citation2020). Some forms of dementia preserve memory function alongside abstract thought and the ability to hold and manipulate information in the mind, which Barry and Lonie (Citation2014) argued are more important determinants of capacity. However, Kiriaev et al. (Citation2018) argued that DMC assessments are especially important for individuals with a neurodegenerative disorder and should be conducted prior to the onset of any cognitive impairments. They argue that for those with dementia, capacity is often lacking, and this leads to a healthcare professional consulting with family members instead, such that individual care preferences are often compromised. Advance care planning is argued to be particularly relevant for individuals with dementia given the likelihood of them eventually being unable to take part in their medical decisions (Alam et al., Citation2022). In their retrospective audit Astell et al. (Citation2013) found no difference in the appointment of an enduring power of attorney (EPOA) between those patients with dementia and those without, but they did highlight the need for increased awareness on the importance of appointing an EPOA in early dementia. Logan et al. (Citation2020) supported this with their audit results showing that a diagnosis of dementia was a predictive factor for an individual to not have capacity, with 67% of patients with a diagnosis of dementia being found to lack capacity (compared with 24% without dementia).

Ries et al. (Citation2020) investigated the inclusion of people with dementia in research studies from the perspective of the researchers. The respondents (who were all experienced in dementia research and assessing the capacity of participants to consent) reported a variety of approaches in how and who assesses a potential participant’s DMC. Only 38% stated that an external health professional is ‘very often’ or ‘always’ involved, and 59% stated that a research team member is ‘very often’ or ‘always’ involved in determining whether the participant has capacity to consent. Only 36% stated that a tool was used to assess the capacity of participants to consent. Given the variance reported earlier in clinical settings, it is not surprising that a broad range of assessment approaches is also used for research purposes.

Mental illness

Another area that adds complexity to capacity assessments is a mental illness. Mental disorders are complex and heterogenous (Howe et al., Citation2005). In their study Howe et al. (Citation2005) found that competence was similar among patients meeting the criteria for different acute diagnoses – schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder – but symptoms such as conceptual disorganisation and poor attention were found to impact competence. More obvious symptoms such as hallucinations did not have any significant relationship with competence. They argued that the phase of illness an individual is in plays a part in competence, with cognitive dysfunction being a key indicator of lack of competence in the acute stages, reinforcing the view that competency should be viewed as a neurocognitive concept.

Milne et al. (Citation2009) found that among a sample of 10 participants under a Mental Health Act Community Treatment Order (CTO), seven were found to have a deficit in one of the subscales assessing competence, compared with two in the sample of participants not under a CTO. They highlighted the interesting issue of people being deemed competent to make decisions while under a CTO. In contrast to this, some of the voluntary service users were found to have deficits in competence with potential implications on their ability to consent to treatment. Ultimately, they argued that any mental health legislation law reform would need to give careful consideration to competence given the unique issues facing mental health clinicians.

Davidson et al. (Citation2016) discussed DMC within the context of changes in Victoria, Australia to increase the prevalence of supported decision-making as a replacement for substitute decision-making, to minimise non-consensual treatment. The Mental Health Act 2014 (Department of Health, Victoria Australia (Citationn.d.).) provides guidance to assess capacity, including information that an individual who is a compulsory patient may not necessarily be wholly lacking capacity, and assessments are required for each decision surrounding their treatment. Similarly, all patients requesting voluntary assisted dying (VAD) require a capacity assessment as a central component, but there may be the presence of a mental illness such as depression, delirium or a psychotic disorder (Peisah et al., Citation2019). Peisah et al. (Citation2019) argued, therefore, that doctors assessing capacity also need the ability to recognise undiagnosed mental illness and refer to a psychiatrist.

Temporary or transitory illness

Although alcoholism is not necessarily temporary, a chronic alcoholic may experience rapid changes in their mental state, from intoxication to withdrawal and sobriety. This brings in additional questions around the suitable timing to conduct a DMC assessment or the potential requirement for additional assessments (Restifo, Citation2013). Given the potential within alcoholism for continued abstinence there is also the question of how long to wait to conduct a definitive assessment. More recently, Kumar et al. (Citation2022) argued that there is a distinct shortage of psychometrically sound DMC assessments for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD). Although their study had several limitations, they provided promising data to suggest that the Compulsory Assessment and Treatment–Capacity Assessment Tool (CAT–CAT), a tool they designed to assess DMC within SUD populations, had good reliability and may fill a need to improve DMC assessment among this population.

Aphasia/communication issues

Aldous et al. (Citation2014) highlighted that the process of assessing a patient’s ability to make a decision is highly variable and complex and can be compromised by the presence of aphasia. When a patient’s ability to produce or understand spoken or written language is impaired, the ability to determine their DMC may be affected. They highlight that an extensive assessment of a patient’s receptive and expressive language along with reading and writing competence is required in circumstances where an individual with aphasia is undergoing a DMC assessment. In particular, careful administration of DMC assessment tools that were developed and standardised for other clinical populations needs to be considered in order to preserve the validity of the assessment (Aldous et al., Citation2014).

The medico-legal interface

Capacity bridges the fields of law and medicine. Assessments are generally clinical and sit within the responsibility of medical professionals, but the outcome determines an individual’s legal rights (Darzins, Citation2010; Parker, Citation2008; Purser & Rosenfeld, Citation2015; Young et al., Citation2018). As such, this gives rise to potential challenges where the medical world intersects with the legal world. The full extent of these challenges goes far beyond the remit of the current review. However, the sections below summarise the key considerations and issues highlighted in the research on DMC assessments from both the medical and legal sides.

Medical practitioner involvement

Given that DMC is a legal construct, it is important that those assessing DMC have a working knowledge of the legal implications of someone who is found to not have DMC (Young et al., Citation2018). It is argued that GPs in particular should be required to have a working knowledge of the relevant Acts (e.g. the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988, in New Zealand; Vara et al., Citation2020). The authors found that GPs required clarification of the legal frameworks and documents, along with increased feedback from the legal system to enable their learning around DMC assessment. It is imperative that healthcare practitioners are aware of how the law relates to their work in DMC assessment because consent must be obtained prior to any treatment being undertaken (Lamont et al., Citation2016). Lamont et al. (Citation2016) stated that within Australia there is no single definition for DMC, and instead the process relies on a range of common laws and statutory definitions.

A further consideration for medical practitioners working in this space is the increasing liability that practitioners may experience, not only with the outcome of the decision but also the assessment process itself being under scrutiny (Purser & Rosenfeld, Citation2014). If medical practitioners are reluctant to participate in DMC assessments, as requested by a lawyer it is likely due to an uncertainty in the potential outcome of such involvement and fear of litigation (Purser et al., Citation2015).

Lawyer involvement

Barry and Lonie (Citation2014) reported that the Office of the Legal Services Commission (OLSC) saw an increase in complaints whereby lawyers accepted instructions from older adults who lacked DMC. Guidance does exist for lawyers in Australia to ensure clients have capacity, in the form of the New South Wales Attorney-General’s ‘Capacity Toolkit’ and the New South Wales Law Society’s ‘Guide for Solicitors When a Client’s Capacity is in doubt’ (Barry & Lonie, Citation2014). Although these guides exist, it appears that some lawyers either are not aware of them or do not routinely apply them. Barry and Lonie suggested that lawyers should seek a medical opinion to assess a client’s DMC in order to protect their client’s decision-making rights against potential future challenges and disputes from their own family. Another consideration facing lawyers is the ongoing debate in the law as to whether specifications are required to recommend that some decisions require more competence than others (Snow & Fleming, Citation2014). For example, it may be that a patient is competent to consent to a minor procedure but not competent to consent to a major one.

Medico-legal relationships

It is clear that both medical and legal professionals have a role to play in an individual’s DMC assessment (Parker, Citation2008) and are increasingly being required to assess the capacity of clients who wish to make a will, an advanced care directive and/or an EPOA (Purser & Rosenfeld, Citation2014) with legal professionals frequently looking to healthcare professionals for expert opinion in this regard. At the centre of the legal interface, therefore, is the relationship between legal and medical professionals including communication and language use (Purser et al., Citation2015). A good example of this is the terms competency and capacity which are often used interchangeably (including in this review). This can increase confusion within and between the professions about what is being assessed (Purser et al., Citation2015). Restifo (Citation2013) further highlighted the disparity in terminology used between the medical and legal systems, with very few Australian states and territories having guardianship Acts with specific criteria for ‘decision-making capacity’. His suggestion is that familiarisation with DMC assessment and the legal requirements should occur from all sides so that those involved can act both clinically and as a facilitator.

The relationship can be further compromised by legal professionals not providing an adequate explanation of the legal capacity that needs to be assessed. In Australia, the laws differ across states and territories, which means that assessment may also differ to meet the specific legal requirements. This, combined with the already ad hoc nature of capacity assessments by medical professionals, may worsen the relationship between the professional groups (Purser et al., Citation2015). Communication between these professions is essential to determine the roles each profession should and is playing in the assessment of an individual’s capacity. Legal professionals do not always have the training to assess the impact of medical conditions such as dementia on DMC assessment, and medical professionals often lack the required knowledge to assess the notion of legal capacity (Purser et al., Citation2015; Purser & Rosenfeld, Citation2014). In combination, however, using an interdisciplinary approach, these professions possess the skills to provide a comprehensive assessment of a person’s capacity thereby decreasing the fear of litigation experienced by medical practitioners (Purser et al., Citation2015). Vara et al., (Citation2020) found widespread concern during their interviews with GPs that their clinical practice may be criticised by the legal system due to the legal framework being viewed at odds with clinical practice.

Purser et al. (Citation2015) argued the need for additional training for both legal and medical professionals, suggesting that compulsory training should be considered for these two professions if working in a space where competence/capacity assessments are required. It is clear that both professions would benefit from increased training to understand more about the work required in each other’s profession and increased communication to develop clear roles.

Voluntary assisted dying/euthanasia

The complexities around VAD are immense, and not surprisingly the mental capacity of the individual requesting euthanasia is central to this issue (Stewart et al., Citation2011). Assisting someone to die can have varying consequences. In Australia, for example, if the person is competent, the crime of assisted suicide may be given to the person assisting; however, the charge could be murder should the person be deemed not competent (Stewart et al., Citation2011). Stewart et al. (Citation2011) argued that as the controversy of assisted suicide becomes more prevalent throughout the western world, a legally defined test of mental competence is required. They proposed a test that could be used in cases of assisted suicide as a guide for healthcare professionals and lawyers and argued that in the case of depression, which does not automatically mean incompetence, a more nuanced approach is needed in clinical end-of-life settings. Overall, Stewart et al. suggested that it is still possible to continue with the assumption that an individual is competent (as is the case when assessing capacity) but a more rigorous and cautious approach is required to determine the impact that mental illness may have on an individual’s competence in deciding on euthanasia.

The Victorian Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 (Vic) commenced on 19 June 2019, and this Act required that an adult must have DMC to be eligible to receive assistance to die (Peisah et al., Citation2019), hence making the assessment of an individual’s DMC in this state a critical skill for clinicians. Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania have all followed suit and recently passed Voluntary Assisted Dying laws (Cassidy et al., Citation2022), highlighting the recent growth of this legislation. Peisah et al. (Citation2019) noted in their commentary that it is a requirement for both of the independent doctors involved in the assessment of a patient’s DMC to undertake a government-approved training before beginning their role. The decision to end one’s life is arguably the biggest decision a person can make, and caution should be taken when assessing a patient’s capacity for this purpose. It is not the case though that less caution or care should be taken when assessing a patient’s DMC for other life decisions such as surgery (Peisah et al., Citation2019). It is good to see the inclusion of compulsory training for those assessing DMC with regard to VAD but it is clear from studies included throughout this review that this is needed across all contexts in which DMC is assessed.

The End of Life Choice Act 2019 was approved in NZ, meaning that from November 2021 VAD became lawful. To be eligible for VAD in NZ an individual must be competent to give their informed consent, and so their DMC must be assessed (Casey & Macleod, Citation2021; Cassidy et al., Citation2022). The authors commented on the extensive requirements of a competency assessment within this context and argued that given the finality of ending one’s life, those conducting the assessments need to be skilled at these assessments, be aware of their own bias and take a considered approach. Although they state the usefulness of tools such as the MacCAT, they also discuss their limitations and highlight the dynamic nature of DMC and the relevance of relationships and context, including cultural and social contexts. Of particular relevance are the principles surrounding tikanga Māori and taha whānau where a relational autonomy approach may be required to incorporate a person’s interpersonal context into the assessment (Casey & Macleod, Citation2021).

In New Zealand if there are concerns about mental illness a psychological and/or psychiatric evaluation is required (Cassidy et al., Citation2022). However, in the survey by Cassidy et al. (Citation2022) among NZ psychiatrists, 53% stated they were ‘unwilling’ or ‘unlikely’ to consider providing VAD services. Understanding of psychiatrists’ obligations under the Act was very low, with only 8% stating they had a very good understanding, and only 9% felt that there was an adequate legal framework to support clinicians to assess competence for assisted dying.

Capacity assessment model of practice

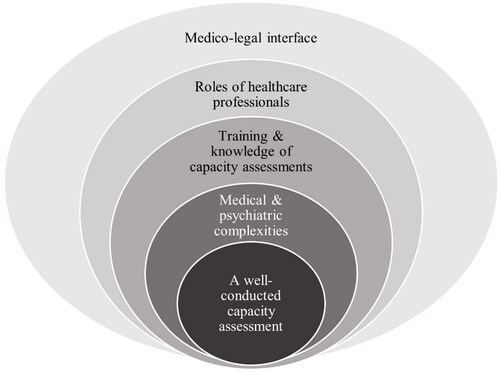

With an ever-increasing population and people living for longer (with or without long-term health conditions), coupled with emerging laws around assisted dying, there is a burgeoning interest in the area of DMC. This systematised literature review has highlighted the need for all medical and legal professionals involved in DMC assessment to have at least foundation knowledge of the intersecting areas of each profession. To synthesise this literature, we propose a model that summarises the process of a well-conducted DMC assessment. The Capacity Assessment Model of Practice (CAMP) is illustrated in . DMC assessments should consider all these elements, and comprehensive training for the medical and legal professionals who conduct capacity assessments should cover all of the topics. The concentric circles in the CAMP model illustrate the increasing levels of knowledge required to ensure a successful and well-conducted capacity assessment.

Conclusion

Although the amount of research into DMC assessment has increased significantly in the last 10 years, it is evident that a number of substantial issues still remain. This systematised review has highlighted the wide variation in approaches and processes underlying the current assessment of a patient’s DMC and is the first to synthesise literature from New Zealand and Australia with relevant findings to Australasian practice. A limitation of this study is the unavailability of all authors to conduct a comprehensive and independent review at each stage of the study, therefore this became a systematised review and not a systematic review. In addition, with limiting the location to Australasian research, the relevance of this review is limited to this geographical area.

Recent local research has looked specifically at those who conduct capacity assessments and has found issues with education, training and, not surprisingly, confidence, in doing DMC assessments. It is not clear who is best placed to conduct these assessments and the different roles healthcare professionals can play. There is very limited research on the roles allied health professionals are currently playing in DMC assessments. Individual research articles exist that focus on specific health professions (e.g. neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, speech-language therapists) and the potential contribution they could make, but little has been done to understand the roles they are currently playing and how they could best contribute to this complex assessment at a broader level. Given the ageing population and increasing demand for healthcare professionals to conduct capacity assessments, it is imperative that those involved in DMC assessments are well trained, confident, aware of the legal implications and consistent in their approach. This is particularly important given the approval of the End of Life Choice Act in New Zealand and similar Acts across Australian states. Future research is needed to understand more about the opinions of multi-disciplinary healthcare professionals and how those involved in DMC assessments could be better trained to increase the prevalence of well-conducted DMC assessments. Additionally, any recommended changes to the current DMC assessment processes and any changes to Australia and NZ laws must consider human rights standards and adhere to the CRPD.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Nicola Mooney has declared no conflicts of interest

Clare M. McCann has declared no conflicts of interest

Lynette Tippett has declared no conflicts of interest

Gary Cheung is an author on one of the included empirical studies in this review and quality appraisal. They were not involved in the quality appraisal process of the articles.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Alam, A., Barton, C., Prathivadi, P., & Mazza, D. (2022). Advance care planning in dementia: A qualitative study of Australian general practitioners. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 28(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY20307

- Aldous, K., Tolmie, R., Worrall, L., & Ferguson, A. (2014). International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology Speech-language pathologists’ contribution to the assessment of decision-making capacity in aphasia: A survey of common practices. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(3), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.871751

- Appelbaum, P. S. (2007). Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(18), 1834–1840. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp074045

- Astell, H., Lee, J.-H., & Sankaran, S. (2013). Review of capacity assessments and recommendations for examining capacity. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 126(1383), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-133

- Barry, L., & Lonie, J. (2014). Capacity, dementia and neuropsychology. Law Society of Nsw Journal, 2014(5), 78–79. https://doi.org/10.3316/agispt.20151912

- Biegler, P., & Stewart, C. (2001). Assessing competence to refuse medical treatment. The Medical Journal of Australia, 174(10), 522–525. https://doi.org/10.5694/J.1326-5377.2001.TB143405.X

- Birchley, G., Jones, K., Huxtable, R., Dixon, J., Kitzinger, J., & Clare, L. (2016). Dying well with reduced agency: A scoping review and thematic synthesis of the decision-making process in dementia, traumatic brain injury and frailty. BMC Medical Ethics, 17(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0129-x

- Candia, P. C., & Barba, A. C. (2011). Mental capacity and consent to treatment in psychiatric patients: The state of the research. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(5), 442–446. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328349bba5

- Casey, J., & Macleod, S. (2021). The assessment of competency and coercion in the End of Life Choice Act 2019. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 134(1547), 114–120. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/assessment-competency-coercion-end-life-choice/docview/2618170968/se-2

- Cassidy, H., Sims, A., & Every-Palmer, S. (2022). Psychiatrists’ views on the New Zealand End of Life Choice Act. Australasian Psychiatry , 30(2), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/10398562221077889

- Connolly, J., & Peisah, C. (2022). Waiting for guardianship in a public hospital geriatric inpatient unit: A mixed methods observational case series. Internal Medicine Journal, 2022, 5916. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15916

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). (n.d.). Article 12 – Equal recognition before the law. Retrieved April 6, 2023 from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-12-equal-recognition-before-the-law.html

- Cheung, G., Frey, R., Young, J., Hoeh, N., Carey, M., Vara, A., & Menkes, D. B. (2022). Voluntary assisted dying: The expanded role of psychiatrists in Australia and New Zealand. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(4), 319–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674221081419

- Darzins, P. (2010). Can this patient go home? Assessment of decision-making capacity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57(1), 65–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1440-1630.2010.00854.X

- Davidson, G., Brophy, L., Campbell, J., Farrell, S. J., Gooding, P., & O’Brien, A.-M. (2016). An international comparison of legal frameworks for supported and substitute decision-making in mental health services. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 44, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.029

- Department of Health, Victoria Australia (n.d.). Mental Health Act 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2023 from https://www.health.vic.gov.au/practice-and-service-quality/mental-health-act-2014

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Grisso, T., Appelbaum, P. S., & Hill-Fotouhi, C. (1997). The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatric Services, 48(11), 1415–1419. https://doi.org/10.1176/PS.48.11.1415

- Howe, V., Foister, K., Jenkins, K., Skene, L., Copolov, D., & Keks, N. (2005). Competence to give informed consent in acute psychosis is associated with symptoms rather than diagnosis. Schizophrenia Research, 77(2–3), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.005

- Jayes, M., Palmer, R., Enderby, P., & Sutton, A. (2020). How do health and social care professionals in England and Wales assess mental capacity? A literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(19), 2797–2808. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1572793

- John, S., Schmidt, D., & Rowley, J. (2020). Decision-making capacity assessment for confused patients in a regional hospital: A before and after study. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/AJR.12540

- Kane, N. B., Ruck Keene, A., Owen, G. S., & Kim, S. Y. H. (2022). Difficult capacity cases – The experience of liaison psychiatrists. An interview study across three jurisdictions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 946234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.946234

- Kiriaev, O., Chacko, E., Jurgens, J. D., Ramages, M., Malpas, P., & Cheung, G. (2018). Should capacity assessments be performed routinely prior to discussing advance care planning with older people? International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1243–1250. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002836

- Kumar, R., Berry, J., Koning, A., Rossell, S., Jain, H., Elkington, S., Nagaraj, S., & Batchelor, J. (2022). Psychometric properties of a new decision-making capacity assessment tool for people with substance use disorder: The CAT-CAT. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology , 37(5), 994–1034. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acac010

- Lamont, S., Jeon, Y. H., & Chiarella, M. (2013). Assessing patient capacity to consent to treatment: An integrative review of instruments and tools. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(17-18), 2387–2403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12215

- Lamont, S., Stewart, C., & Chiarella, M. (2016). Decision-making capacity and its relationship to a legally valid consent: Ethical, legal and professional context. Journal of Law and Medicine, 24(2), 371–386. https://anzlaw.thomsonreuters.com/Document/I9a0191d5683911ea9466e69956ff701d/View/FullText.html?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&VR=3.0&RS=cblt1.0

- Lamont, S., Stewart, C., & Chiarella, M. (2019). Capacity and consent: Knowledge and practice of legal and healthcare standards. Nursing Ethics, 26(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016687162

- Logan, B., Fleury, A., Wong, L., Fraser, S., Bernard, A., & White, B. (2020). Characteristics of patients referred for assessment of decision-making capacity in the acute medical setting of an outer-metropolitan hospital – A retrospective case series. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 39(1), e49–e54. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12693

- Matus, J., Mickan, S., & Noble, C. (2020). Developing occupational therapists’ capabilities for decision-making capacity assessments: How does a support role facilitate workplace learning? Perspectives on Medical Education, 9(2), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-020-00569-1

- Milne, D., O’Brien, A., & McKenna, B. (2009). Community treatment orders and competence to consent. Australasian Psychiatry, 17(4), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560902721572

- Moye, J., & Marson, D. C. (2007). Assessment of decision-making capacity in older adults: An emerging area of practice and research. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(1), P3–P11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.1.P3

- Mullaly, E., Kinsella, G., Berberovic, N., Cohen, Y., Dedda, K., Froud, B., Leach, K., & Neath, J. (2007). Assessment of decision-making capacity: Exploration of common practices among neuropsychologists. Australian Psychologist, 42(3), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060601187142

- Newton-Howes, G., Pickering, N., & Young, G. (2019). Authentic decision-making capacity in hard medical cases. Clinical Ethics, 14(4), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750919876248

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Parker, M. (2008). Bioethical issues – Patient competence and professional incompetence – Disagreements in capacity assessments in one Australian jurisdiction, and their educational implications. Journal of Law and Medicine, 16(1), 25–35. https://anzlaw.thomsonreuters.com/Document/I183ca547683a11ea9466e69956ff701d/View/FullText.html?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&VR=3.0&RS=cblt1.0

- Parmar, J., Brémault-Phillips, S., & Charles, L. (2015). The development and implementation of a decision-making capacity assessment model. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 18(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.18.142

- Peisah, C., Sheahan, L., & White, B. P. (2019). Biggest decision of them all – Death and assisted dying: Capacity assessments and undue influence screening. Internal Medicine Journal, 49(6), 792–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/IMJ.14238

- Purser, K., Magner, E. S., & Madison, J. (2015). A therapeutic approach to assessing legal capacity in Australia. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 38, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.01.003

- Purser, K., & Rosenfeld, T. (2014). Evaluation of legal capacity by doctors and lawyers: The need for collaborative assessment. The Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 483–485. https://doi.org/10.5694/MJA13.11191

- Purser, K., & Rosenfeld, T. (2015). Assessing testamentary and decision-making capacity: Approaches and models. Journal of Law and Medicine, 23(1), 121–136. https://auckland.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/64UAUCK_INST/3mftp2/cdi_pubmed_primary_26554203

- Raymont, V. (2002). Not in perfect mind’ – The complexity of clinical capacity assessment. Psychiatric Bulletin, 26(6), 201–204. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.26.6.201

- Raymont, V., Buchanan, A., David, A. S., Hayward, P., Wessely, S., & Hotopf, M. (2007). The inter-rater reliability of mental capacity assessments. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 30(2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.09.006

- Restifo, S. (2013). A review of the concepts, terminologies and dilemmas in the assessment of decisional capacity: A focus on alcoholism. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(6), 537–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856213497812

- Ries, N. M., Mansfield, E., & Sanson-Fisher, R. (2020). Ethical and legal aspects of research involving older people with cognitive impairment: A survey of dementia researchers in Australia. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 68, 101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101534

- Scott, J., Weatherhead, S., Daker-White, G., Manthorpe, J., & Mawson, M. (2020). Practitioners’ experiences of the mental capacity act: A systematic review. The Journal of Adult Protection, 22(4), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-02-2020-0005

- Snow, H. A., & Fleming, B. R. (2014). Consent, capacity and the right to say no. The Medical Journal of Australia, 201(8), 486–488. https://doi.org/10.5694/MJA13.10901

- Stewart, C., Peisah, C., & Draper, B. (2011). A test for mental capacity to request assisted suicide. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.037564

- United Nations. (n.d.). Conventions on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved April 6, 2023 from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-12-equal-recognition-before-the-law.html

- Usher, R., & Stapleton, T. (2020). Occupational therapy and decision-making capacity assessment: A survey of practice in Ireland. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12629

- Usher, R., & Stapleton, T. (2022). Assessment of older adults’ decision‐making capacity in relation to independent living: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(2), e255–e277. https://doi.org/10.1111/HSC.13487

- Vara, A., Young, G., Douglass, A., Sundram, F., Henning, M., & Cheung, G. (2020). General practitioners and decision-making capacity assessment: The experiences and educational needs of New Zealand general practitioners. Family Practice, 37(4), 535–540. https://doi.org/10.1093/FAMPRA/CMAA022

- Young, G. (2004). How to assess a patient’s competence. New Ethicals Journal, 41–45. Sourced from hard copy in library.

- Young, G., Douglass, A., & Davison, L. (2018). What do doctors know about assessing decision-making capacity? New Zealand Medical Journal, 131(1471), 58–71. http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/what-do-doctors-know-about-assessing-decision/docview/2053258369/se-2