Abstract

The current study aimed to identify factors that influence the likelihood of mental health diversion under s.32 and s.33 of the NSW Mental Health (Forensic Procedures) Act using a sample of 2,922 individuals represented by NSW Legal Aid who sought to have their charges dismissed. Multilevel logistic regression was used to identify the factors correlated with diversion. Higher odds of s.32 diversion were found for women, non-Indigenous defendants, those with no prior court appearances and those who committed less serious offences. Higher odds of s.33 diversion were found for those who were older, those who had been previously imprisoned or those who had prior mental health dismissals. Almost 12% of the variation in s.32 dismissal decisions is attributable to the magistrate hearing the case.

Introduction

The high prevalence of mental illness amongst those coming into contact with the criminal justice system is well documented both overseas (Al-Rousan et al., Citation2017; Bebbington et al., Citation2017; Tyler et al., Citation2019) and in Australia (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, AIHW, Citation2019, Citation2021; Baksheev et al., Citation2010; Butler et al., Citation2011; Forsythe & Gaffney, Citation2012; Jones & Crawford, Citation2007; Ogloff et al., Citation2015; Vanny et al., Citation2009). In response to this overrepresentation, most Australian States and Territories have introduced legislation that, in certain circumstances, allows courts to dismiss the charges against a defendant and divert them into mental health treatment. In NSW, almost all cases of diversion under ss. 32 and 33 occur in the Local Court. Local Court proceedings are presided over by a magistrate (rather than a judge and jury) and deal with offences where the maximum penalty is two years or less.

Until recently, individuals appearing before New South Wales (NSW) Local Courts with a mental illness or cognitive impairment could be diverted via Sections 32 and 33 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). Section 32 enabled a magistrate to dismiss the charge/s and discharge a defendant with a mental illness or cognitive impairment into the care of a person or place (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). Section 33 allowed a magistrate to order that a defendant be taken to and detained in a mental health facility for assessment. Section 32 applied to defendants with a mental illness or cognitive impairment, while Section 33 applied to defendants considered ‘mentally ill’ under the Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). Mentally ill individuals were defined in the legislation as those who need ‘care, treatment and control’ in order to protect themselves and/or others (Buchanan, Citation2020). Both Section 32 and Section 33 were limited to those who have been charged with a summary offence or an indictable offence deemed triable summarily, and both were enforceable for six months.

Recent law reform saw the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW) repealed and the provisions carried over into the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020 (NSW) (MHCIFPA). This Act received assent on 23 June 2020 and commenced on 27th of March 2021 (Sanders, Citation2021). The equivalent sections for Sections 32 and 33 in the new Act are Part 2 Division 2 and Part 2 Division 3, respectively. The changes made in the MHCIFPA are minor and involve new definitions, an increase in the enforcement period for a s.32 order from six months to 12 months, the inclusion of ‘mentally disordered persons’ under Section 33 (in addition to ‘mentally ill’ persons) and, finally, a list of factors a magistrate may consider when dealing with a Section 32 application, all of which were reflected in existing caselaw (Sanders, Citation2021).

Previous research has found that only a small fraction of those who have a serious mental illness are being diverted in NSW Local Courts. Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) found that only 26% of those previously diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder received a treatment order, with the remainder being prosecuted and dealt with according to the law. They also found that defendants who had been previously diagnosed with schizophrenia or related psychosis were far more likely to be diverted into treatment than those who had been diagnosed as having a substance-related psychosis. To date, very little research has been conducted into why the diversion rate is low or, more generally, what factors magistrates consider when deciding whether or not to dismiss the charges against a defendant under s.32 (or s.33) and divert the person into treatment. The purpose of the present study is to shed some light on these questions. Before reviewing the limited past research on factors that influence magistrate decision making under s.32 and s.33, we begin with a brief summary of what the law requires magistrates to consider.

What magistrates must consider

The first requirement when a magistrate is considering issuing a Section 32 or 33 order is to determine whether the individual is eligible for such an order. In the case of Section 32, the individual must be suffering from a mental illness or cognitive impairment, either at the time of the offence or during court proceedings (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). To be eligible for a Section 33 order, an individual must be a mentally ill person during court proceedings (Buchanan, Citation2020). Although the legislation enables a magistrate to divert a defendant into treatment if they are deemed eligible, much of the guidance around these decisions comes from case law, most of which concerns Section 32 rather than Section 33.

Once a defendant is deemed eligible to be dealt with via Section 32, a magistrate must determine that diversion is a ‘more appropriate’ action than dealing with the defendant according to the law (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). This question of appropriateness is a ‘balancing exercise’, in which the magistrate must weigh up two public interests that may, at times, be at odds with one another (Fernandez, Citation2007). The first public interest concerns the need to ensure that defendants in criminal proceedings experience the ‘full weight of the law’. The second concerns the need to treat those whose crimes are due to mental illness in order to protect the community. (Fernandez, Citation2007; Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008).

In addition to the concept of appropriateness, the case law requires magistrates to consider several factors when making a Section 32 order. These include the seriousness and circumstances of the alleged offence(s), the defendant’s criminal history, the existence and content of a treatment plan, the duration of the order and the sentencing options available if the defendant is dealt with according to the law (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). An individual accused of a serious offence may be diverted via Section 32, as long as diversion is considered the ‘more appropriate’ option and is more beneficial to the defendant and the community than dealing with the defendant according to the law (Fernandez, Citation2007). Although treatment plans are not stipulated in the legislation, it is established in case law that magistrates must be provided with ‘clear and effective’ treatment plans when considering Section 32 cases (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008).

Past research

There is limited research on mental health diversion in NSW, particularly regarding the factors or characteristics that are associated with a magistrate’s willingness to divert a person under Section 32 or 33. As noted earlier, Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) examined court diversion in a sample of individuals diagnosed with a psychotic disorder in an analysis that was primarily focused on the effect of diversion on risk of reoffending. They found that 9% of individuals diagnosed with a substance-related psychosis were diverted into treatment, compared with around 30% of those diagnosed with an affective psychosis (30.3%) or schizophrenia. Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) also found that a significantly smaller proportion of Indigenous Australians were diverted than non-Indigenous Australians. Whether these differences would hold up in the presence of controls for other relevant factors (e.g. level of violence in the alleged offence) remains unclear.

In a study of individuals assessed as eligible for mental health diversion by the Statewide Community and Court Liaison Service (SCCLS), Soon et al. (Citation2018) found higher odds of diversion among women, those aged 40 years or older, those who were neither Aboriginal nor Torres Strait Islander and those who had been diagnosed as having a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or some other form of psychosis. Although this study highlighted some factors relevant to mental health diversion in the Local Court, Soon et al. (Citation2018) defined ‘diversion’ to include treatment as a condition of bail and bonds. This makes it difficult to determine whether their findings hold true of diversion involving Section 32 and/or 33. Soon et al. (Citation2018) also lacked the information required to control for offence seriousness or violence or criminal history, all of which could confound the relationship between mental illness diagnosis and a court’s willingness to dismiss a charge under s.32 or 33.

Based on the case law, we would expect individuals accused of violent or more serious offences to be less likely to be diverted than those accused of minor, non-violent crimes. Given the requirement for ‘clear and effective’ treatment plans and the relative lack of treatment services in rural and remote areas (Mental Health Commission of New South Wales, Citation2018), we would also expect lower rates of diversion in regional or remote areas. We examined these expectations in a previous study using a sample of 7283 individuals with a psychotic disorder accused of at least one offence after their diagnosis (Macdonald et al., Citation2023). We found defendants were less likely to be diverted if they were Indigenous, living in a regional or remote area, had at least one court appearance in the past and had a substance-induced psychotic disorder. Contrary to expectations, we found that those accused of violent or more serious offences were significantly more likely to be diverted than those accused of less violent or less serious offences (odds ratio, OR, 2.0 and 1.4, respectively).

Although our previous study provided insight into the factors that influence magistrate decision making in relation to mental health referral, that study had several limitations. Firstly, the sample was limited to persons known to have a psychotic illness. Since having a psychotic illness is not a precondition of s.32 or s.33 referral, such cases cannot be regarded as typical or representative of all cases where a s.32 or s.33 application is made or determined by a court. Secondly, we were not actually able to determine whether individuals in the previous sample sought to have their charge or charges dismissed under s.32 or s.33. This is unfortunate because the correlates of decisions under these two sections may differ. Thirdly, because we had no information on the identity of the magistrate making the decision, we had no way of determining the variation in magistrate willingness to divert after adjusting for characteristics of the defendant.

The current study

The current study improves on past research in three ways. First, we examine a large sample of individuals represented in Section 32 or 33 proceedings by the NSW Legal Aid Commission. The Commission represents many eligible individuals seeking a Section 32 or 33 dismissal. This ensures we have a more representative sample than in Macdonald et al. (Citation2023). Second, we conduct separate analyses of the correlates of s.32 and s.33 decisions. Thirdly, as the dataset we use in this study contains an anonymised identity code for each magistrate making each s.32 or 33 diversion decision, we can determine how much of the variation in s.32 or 33 dismissals is attributable to the magistrate hearing the case, after adjusting for legally relevant characteristics of the defendant. The research questions, then, are as follows:

Do offence seriousness and type (violent vs. non-violent) exert similar effects in a larger and more representative sample to those observed in Macdonald et al. (Citation2023)?

Are there any material differences in the correlates of s.32 and s.33 decisions?

How much of the variation in s.32 or 33 decisions is attributable to the magistrate after adjusting for characteristics of the defendant?

Method

Sample

The current study utilised a sample of 3796 individuals represented by Legal Aid between 2017 and 2019 who sought to have their charges dealt with via Section 32 or 33. These data were provided to the researchers by Legal Aid NSW. The dataset contained a code number assigned by police that uniquely identifies a group of charges belonging to the same individual. This number is also present in the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) Re-offending Database (ROD; Hua & Fitzgerald, Citation2006) and was used to link the data in the Legal Aid dataset to ROD data. The ROD data contains information on whether the person has been given a treatment order under s.32 or s.33 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). It also includes data on offence type, age, gender, Indigenous status (Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous) and criminal history, including prior offence type. Of the 3796 Legal Aid records provided to BOCSAR, 138 were unable to be matched due to errors in recording case numbers or outcomes, outcomes not being finalised in the system or charges being dismissed via Youth Conference. This resulted in a total sample of 3658 records.

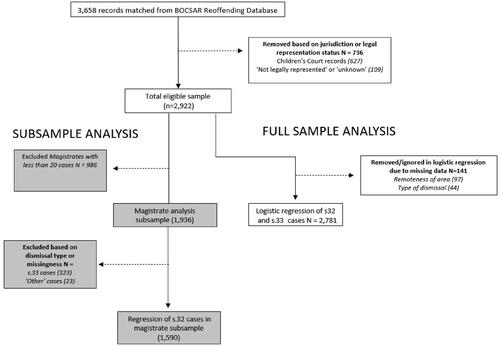

Because we hypothesised that dismissal via Sections 32 or 33 in the Children’s Court may operate differently to cases dealt with by the Local Court, defendants under 18 years of age and those appearing in court cases not finalised in the Local Court were removed (n = 627). Furthermore, because we wanted to analyse a sample in which we knew the defendant’s legal counsel had sought a dismissal, we also removed individuals whose legal representation was listed as ‘not legally represented’ (n = 108) or ‘unknown’ (n = 1). This resulted in a total sample of 2922. For the purposes of logistic regression, individuals with missing data on remoteness of residence (n = 97) and those whose court outcome was recorded as ‘other’ (n = 44) were excluded. This resulted in a total sample of 2781.

The study comprised two samples: the full sample and a subset of the full sample. The full sample was employed to examine the correlates of s.32 and s.33. The subsample was employed to examine the differences between magistrates in their willingness to divert individuals via s.32. Further detail is provided in the analysis section and in the flowchart in .

Dependent variable

The outcome of interest was mental health referral under s.32 or 33 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). We examined Section 32 and Section 33 orders separately, by creating two dummy variables for each category. The Section 32 dummy variable was coded ‘1’ if the defendant was diverted via Section 32 and ‘0’ if they were prosecuted according to the law or if their charges were dropped or their case was otherwise disposed of. Those dismissed via Section 33 were treated as missing. The Section 33 dummy variable was coded ‘1’ if the defendant was diverted via Section 33 and ‘0’ if they were prosecuted according to the law or if their charges were dropped or their case was otherwise disposed of. Those dismissed via Section 32 were treated as missing.

Independent variables

As discussed earlier, offence violence and offence seriousness, the prior criminal history of the defendant and the existence of a treatment plan are all established in the caselaw as key factors for magistrates to consider when choosing whether to divert a defendant into treatment. Offence seriousness was measured using the NSW BOCSAR median severity ranking (MSR; MacKinnell et al., Citation2010). Offences were categorised into ‘less serious’ or ‘more serious’, according to whether they were below, or at or above the median MSR score (56). The Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC) was used to classify offences as violent or non-violent (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2011). Violent offences were coded as any offence in Divisions 01–03 or 05–06. Offences under Division 04 ‘Dangerous or negligent acts endangering persons’ were categorised as non-violent, as they include offences such as negligent driving, which may result in injury or harm, but do not involve a plan to do so.

The prior criminal history of the defendant was measured using two variables in ROD. The first was a count of the number of prior proven court appearances (i.e. court appearances at which at least one offence was found proved). The second was a binary variable capturing whether the defendant had previously been imprisoned. As there was no direct measure of whether the defendant had a treatment plan available, and as mental health treatment may be limited in regional and remote areas, we used remoteness as a proxy measure of treatment availability. The remoteness measure used was the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) – developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021).

We also examined variables that are not reflected in case law, but which have been found to be significant factors in Section 32 or 33 decisions in past research. In our previous study, we found that Indigenous defendants and defendants whose cases were heard in a Local Court without the SCCLS had significantly lower odds of diversion, whilst controlling for all other variables in the model (Macdonald et al., Citation2023). As with offence violence and offence seriousness, we wanted to examine these variables in a more representative sample of people with a mental illness. We also included variables that are expected to influence Sections 32 and 33 on a priori grounds. Age and gender are both considered relevant factors in sentencing at common law (Gelb, Citation2010; Judicial Commission of New South Wales, Citation2021) and therefore may be relevant when making Section 32 or 33 decisions. See for independent variables and their coding.

Table 1. List of included variables and their coding.

Analysis

Analyses of the full sample and the subset were conducted in Stata 16.0. To analyse the correlates of s.32 and s.33 decisions we began by conducting a series of bivariate analyses to determine which variables were significantly associated with mental health diversion. The significant variables from the bivariate analyses were subsequently entered into separate logistic regression models to determine which variables independently predicted diversion under s.32 and s.33.

To examine the influence of the magistrate, we employed a two-level logistic regression model with random intercepts. The first level involved factors associated with the defendant. The second level involved the (coded) identity of the magistrate and allowed the outcome of cases dealt with by the same magistrate to be correlated. More importantly, it allowed each magistrate to have their own baseline (intercept) willingness to divert a defendant, even if they all respond similarly to the defendant characteristics measured at Level 1. We restricted the sample to include only magistrates who had dealt with at least 20 s.32 cases. The model we constructed is focused on s.32 because the number of cases involving s.33 was too small to conduct a multi-level analysis.

To test the appropriateness of a multilevel model for s.32, we began by comparing a simple logistic regression model in which magistrate is the only covariate with a multilevel model where the magistrate is entered as a variable in Level 2. If a multilevel model is warranted, there should be a significantly lower log likelihood for a model that includes a second (magistrate) level than for a simple logistic regression model where magistrate is the only covariate. If a multilevel model is warranted, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which measures the correlation among observations within the same magistrate, should also be larger than .05. If these criteria are met, we need to control for factors that magistrates consider when deciding whether to divert a defendant. The Level 1 factors employed for this purpose are those found to be independent correlates of the decision to divert under s.32 (see left-hand panel of ).

Results

Sample description

provides descriptive statistics for the sample. A total of 70% were male, and 62% were aged 30 years or over. The majority were non-Indigenous (79%). Overall, 48% were not dismissed (n = 1412). Of these, a small proportion (0.05%) had their charges withdrawn (n = 23), were found not guilty (n = 43) or had their case otherwise disposed of (n = 6). A total of 39% were given a Section 32 dismissal (n = 1143), and 11% were given a Section 33 dismissal (n = 323). The remaining 44 were diverted, but whether this was via Section 32 or Section 33 was not specified in their records.

Table 2. Sample description.

Bivariate analyses

The results of the bivariate analysis for Sections 32 and 33 are shown in . Gender, age, Indigenous status, prior court appearances, prior prison, and offence violence and seriousness were all significantly correlated with diversion via Section 32. Defendants were more likely to be diverted via Section 32 if they were female, older, non-Indigenous, had no prior court appearances and had not previously been imprisoned. They were also more likely to be diverted if they had committed either a non-violent or less serious offence. Variables not significantly associated with mental health diversion via s.32 were remoteness of area, prior mental health dismissals and whether the court where the defendant appeared had a court liaison service.

Table 3. Bivariate comparisons of variables associated with s32 and s.33 dismissal.Table Footnotea

The pattern for s.33 is similar, except that none of gender, Indigenous status or type of offence (serious vs. non-serious; violent vs. non-violent) were significant.

Multivariate analyses

The results of the logistic regression for Section 32 and Section 33 dismissals are shown in . In the case of s.32, controlling for other factors, males were significantly less likely to be diverted than female defendants, as were Indigenous defendants, those who had had one or more prior court appearances and those accused of more serious offences. We found no impact of age or prior prison on the odds of diversion under s.32. Nor did the fact that the principal offence involved violence have any significant effect on the odds of diversion under s.32.

Table 4. Models of Mental Health Dismissal via s.32 and s.33.

The results for Section 33 dismissals differ in several respects from those involving s.32. Age had no effect on the likelihood of diversion under s.32; however, older defendants were more likely to be diverted under s.33. Prior imprisonment had no effect on the likelihood of diversion under s.32 but increased the likelihood of diversion under s.33. Prior court decreased the likelihood of diversion under s.32 but had no effect on the likelihood of diversion under s.33. Individuals were significantly more likely to be diverted if they had previously had charges dismissed under ss.32 or 33 and if they presented to a court with a court liaison service, though neither of these variables had a significant impact on s.32 diversion.

Multi-level model analysis

shows the results of a multilevel model that includes no explanatory variables. There were 48 magistrates in the sample who had dealt with at least 20 cases, with an average of 33 cases per magistrate (min = 20, max = 90). The row labelled _cons is the grand mean of the magistrate intercepts on prosecution. The row labelled Magistrate var(_cons) shows the estimated variance of the Level 2 variable (magistrate) intercepts. The chi-square test underneath the table compares a simple logistic regression model against a multilevel model. The difference is statistically significant, indicating that the multi-level model explains significantly more of the variation in mental health dismissal. The ICC (proportion of overall variance explained by magistrate) is .093.

Table 5. Multilevel logistic regression model (Level 2 only).

Magistrate level variation

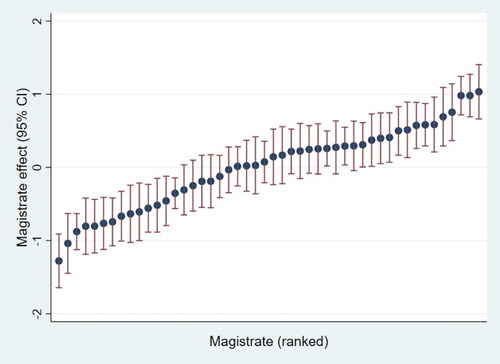

shows the full model, including both Level 1 and Level 2 covariates. The ICC for the full model is .115 (an increase of .022), indicating that, even after controlling for a wide range of legally relevant factors, almost 12% of the variation in s.32 dismissal decisions is attributable to the magistrate hearing the case. Some of the Level 1 variables that were significant in the logistic regression remained significant in the multi-level regression, and others did not. Gender and Indigenous status were no longer significant, while prior court and offence seriousness were significant and in the same direction of effect as the logistic regression, except for one prior court appearance, which was no longer significant.

Table 6. Multi-level logistic regression model (Levels 1 and 2).

The variation among magistrates is illustrated graphically in . This graph shows the deviation of each magistrate from the mean likelihood of diversion across all magistrates with more than 20 cases, after controlling for relevant legal factors. The majority (56.25%) of the magistrates are significantly above or below the average for the group as a whole, with approximately half of these significantly below the group average, and half significantly above the group average.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to determine whether offence seriousness and type (violent vs. non-violent) exert similar effects in a larger and more representative sample to those observed in Macdonald et al. (Citation2023), whether there are any material differences in the correlates of s.32 and s.33 decisions and how much of the variation in s.32/33 decisions is attributable to the magistrate.

The results of the current study revealed no similarities in the correlates of decisions under Sections 32 and 33. Being male, Indigenous, having more prior court appearances and being charged with a more serious offence were all associated with a lower likelihood of charge dismissal under s.32. Age had no significant effect on Section 32 dismissal. Conversely, for Section 33 cases, gender and offence seriousness did not impact diversion, while individuals aged 30 or over who had been previously incarcerated or who appeared before a court with a liaison service had higher odds of diversion.

When considering these differences, it is important to remember that Sections 32 and 33 differ from one another in terms of whom they apply to. Section 33 caters to a subset of individuals who are unwell at the time of their court appearance and who are believed to ‘need care, treatment or control’ to protect either themselves or others from ‘serious harm’ Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). Section 33 is also used less often than Section 32; in past research, Soon et al. (Citation2018) found that of those diverted, only 9.43% were done so via Section 33, compared to 16.5% via Section 32. In the current study, only 11% of the sample were dismissed via Section 33, compared to 39% for Section 32. Thus, the fact that the two dismissal types revealed different predictive factors is unsurprising and highlights the importance of examining these two dismissal types separately. However, it is interesting that in this dataset, factors such as age and the SCCLS were more important for s.33 than s.32 decisions. These results are intriguing and warrant further examination.

In a previous study of defendants diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, we found that those accused of more serious or violent offences were more likely to be diverted than those accused of less serious or non-violent offences (Macdonald et al., Citation2023). In the current study, after adjusting for other factors, we found that those charged with more serious offences were less likely to be diverted under Section 32 than those accused of less serious offences. This is in line with case law, which holds that more serious offences may be less appropriate for diversion. Somewhat surprisingly, however, we found no effect of offence seriousness or violent offending in connection with the Section 33 cases. This result is surprising because defendants dealt with under this section are more likely to be suffering from a psychotic disorder. Macdonald et al. (Citation2023) found that individuals diagnosed with such a disorder who are charged with a violent and/or serious offence are more likely to be diverted. It is not clear what accounts for the difference between past research and the present study, but it is important to remember that in our previous study we had no information on whether the case was dealt with under s.32 or s.33. Had we been able to conduct separate analyses of cases under these sections, we may have found results in accord with the current findings.

The positive impact of the court liaison service on Section 33 diversion emphasises the importance of this service in identifying acutely unwell individuals at court and facilitating their diversion into treatment. The fact that we did not find an impact of this service for the Section 32 defendants warrants a further explanation of how these cases differ in practice and how assessment and referral for s.32 and s.33 operate. Defendants without legal representation must make their own case for dismissal – a challenging task given the reliance of the court on clinical expertise when making s.32 decisions. One possibility worth exploring is whether those who are unable to access the court liaison service end up engaging (at considerable cost) the service of a private psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

Another interesting finding was that in the s.33 analysis only, individuals who were previously dismissed under Sections 32 or 33 had increased odds of diversion compared to those who had not had charges dismissed before. This is in the opposite direction to what we had hypothesised, which was that a previous dismissal might appear to the court that past treatment has not been effective, and thus might be disadvantageous for a defendant. It may be that previous dismissals increase the perceived validity of individuals presenting as unwell at the time of their court appearance. The fact that we did not find an effect of previous dismissals on s.32 dismissal is intriguing. It would be of benefit to obtain perspectives of legal and mental health professionals regarding this finding.

Our multilevel analysis shows that even when accounting for variables such as offence violence, seriousness and criminal history, the individual magistrate significantly impacts the odds of diversion. This is the first study, as far as we are aware, to have examined the independent impact of an individual magistrate on mental health diversion in the criminal justice system. We found that almost 12% of the variation in s.32 dismissal decisions is attributable to the magistrate hearing the case. We also found wide variation between magistrates in their willingness to divert similar cases (as judged in terms of our covariates). A total of 56% of the magistrates in the subsample were either significantly above or significantly below the average in their odds of diversion.

This result is open to two interpretations. The first is that there are factors influencing magistrate decision making under s.32 that we have been unable to measure and include in our analysis. The second is that there is a substantial degree of unwarranted disparity in the way magistrates exercise their discretion under s.32. The first interpretation is suggested by the wide degree of discretion enjoyed by magistrates in making s.32 decisions. Our controls, however, do not capture all of the legal factors that courts are invited or required to consider. Indeed, there is one key factor that may explain the variation between magistrates in s.32 decisions and variable results concerning the effect of violence and offence seriousness. It is firmly established in case law that ‘clear and effective’ treatment plans must be available to magistrates before making Section 32 decisions (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). Our analysis included no controls for differences between cases in the quality of the treatment plans provided to the court.

The points just made highlight a significant limitation in the current study. The area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.66 and 0.70 for the s.32 and s.33 regression models, respectively, are acceptable (Hosmer et al., Citation2013), but suggest there are likely other important predictors of s.32 and s.33 decisions that are not captured by our covariates. The absence of a control for the quality of the treatment plan is one, but there may be others. It is conceivable, for example, that magistrates differ in the weight they assign to offence seriousness when balancing public safety against the needs of the defendants. It is also possible that those who were diverted exhibited more serious mental health conditions or cognitive impairments than those who were not diverted. Among these, the nature of the mental illness or cognitive impairment and the character and quality of the treatment plan are the most critical. Future research in this area should focus on the influence of these factors.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that, although the NSW Legal Aid Commission funds more than 50% of criminal cases in New South Wales (Richards & Trevallion, Citation2023), defendants represented by the Legal Aid Commission are not a random sample of all cases. Access to publicly funded legal aid is strictly means tested. The patterns observed in this study, therefore, may not be true of defendants who are wealthy enough to secure private legal representation.

The current study has two important implications for future research. Firstly, on the evidence presented in this article, there is considerable disparity among magistrates in their willingness to divert a mentally ill defendant into treatment. This variation does not appear to be explicable in terms of legal factors that magistrates may or must consider. Further research is clearly required to gain a better understanding of this disparity. Secondly, in cases involving s.32, the court liaison service appears to have no effect on the likelihood of diversion. We need to understand why this is the case, especially given that support from a court liaison service is clearly of benefit when a s.33 diversion is under consideration by the court. Information on these issues would help ensure that all those who meet the criteria for diversion under ss.32 and 33 are in fact receiving the treatment they need.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Christel Macdonald has declared no conflicts of interest.

Don Weatherburn has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HC210030), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Note that although the study was an analysis of deidentified health and court records, it was not an in vivo experiment with human participants. It was also not feasible to obtain consent. The whereabouts of individuals convicted is not generally known, and the numbers involved were too large to track down. We obtained a waiver of consent by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HC210030).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude for the assistance provided by Legal Aid NSW in conducting this project. Particular thanks are due to Brendan Thomas, former CEO of Legal Aid and Monique Hitter, current CEO of Legal Aid, who made the project possible. Special thanks are also due to Kim Chow for provision of the data and Paul Johnson for advice on the operation of the Legal Aid system in New South Wales.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Rousan, T., Rubenstein, L., Sieleni, B., Deol, H., & Wallace, R. B. (2017). Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: A prevalence study in a state prison system. BMC Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4257-0

- Albalawi, O., Chowdhury, N. Z., Wand, H., Allnutt, S., Greenberg, D., Adily, A., Kariminia, A., Schofield, P., Sara, G., Hanson, S., O’Driscoll, C., & Butler, T. (2019). Court diversion for those with psychosis and its impact on re-offending rates: Results from a longitudinal data-linkage study. BJPsych Open, 5(1), e9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.71

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Australian and New Zealand standard offence classification (ANZSOC). Australian Bureau of Statistics Canberra, ACT, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/australian-and-new-zealand-standard-offence-classification-anzsoc/latest-release

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Remoteness structure. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2019). The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Mental health services in Australia. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services/interactive-data

- Baksheev, G. N., Thomas, S. D. M., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2010). Psychiatric disorders and unmet needs in Australian police cells. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(11), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048674.2010.503650

- Bebbington, P., Jakobowitz, S., McKenzie, N., Killaspy, H., Iveson, R., Duffield, G., & Kerr, M. (2017). Assessing needs for psychiatric treatment in prisoners: 1. Prevalence of disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1311-7

- Buchanan, D. (2020). A practical guide to mental issues in the NSW local court part 1. Sections 32 and 33 Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). Legal Aid NSW. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/41899/A-Practical-Guide-to-MH-Issues-in-the-NSWLC-Part-1-ss-32-33-MHFPA.pdf

- Butler, T., Indig, D., Allnutt, S., & Mamoon, H. (2011). Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder among Australian prisoners. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00216.x

- Fernandez, L. (2007). Section 32 Mental Health (Criminal Procedure) Act – Summary of principles. Legal Aid NSW. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/6099/Section-32-Summary-of-Principles-.pdf

- Forsythe, L., & Gaffney, A. (2012). Mental disorder prevalence at the gateway to the criminal justice system (Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice Issue 438). Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Gelb, K. (2010). Gender differences in sentencing outcomes. Sentencing Advisory Council. https://www.sentencingcouncil.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-08/Gender_Differences_in_Sentencing_Outcomes.pdf

- Gotsis, T., & Donnelly, H. (2008). Diverting mentally disordered offenders in the NSW Local Court. Judicial Commission of New South Wales.

- Hosmer, D. W., Jr., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. X. (2013). Applied logistic regression (Vol. 398). John Wiley & Sons.

- Hua, J., & Fitzgerald, J. (2006). Matching court records to measure reoffending. BOCSAR NSW Crime and Justice Bulletins, 12, 1–12.

- Jones, C., & Crawford, S. (2007). The psychosocial needs of NSW court defendants (Crime and Justice Bulletin, Issue 108). NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

- Judicial Commission of New South Wales. (2021). Subjective matters taken into account (cf s 21A(1)). Sentencing Bench Book. https://www.judcom.nsw.gov.au/publications/benchbks/sentencing/subjective_matters.html

- Macdonald, C., Weatherburn, D., Butler, T., Albalawi, O., Greenberg, D., & Farrell, M. (2023). Who gets diverted into treatment? A study of defendants with psychosis. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 1–14. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2023.2175070

- MacKinnell, I., Poletti, P., & Holmes, M. (2010). Measuring offence seriousness. Crime and Justice Bulletin, (142), 1–12.

- Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). https://legacy.legislation.nsw.gov.au/#/view/act/2007/8/chap3/part1/sec14

- Mental Health Commission of New South Wales. (2018). Mental Health Commissions Submission - Mental health services in rural and remote Australia. https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/sites/default/files/old/documents/mental_health_commissions_submission_-_mental_health_services_in_rural_and_remote_australia.pdf

- Ogloff, J. R. P., Talevski, D., Lemphers, A., Wood, M., & Simmons, M. (2015). Co-occurring mental illness, substance use disorders, and antisocial personality disorder among clients of forensic mental health services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000088

- Richards, S., & Trevallion, J. (2023). The impact of stagnant legal aid rates on access to justice in Australia. https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2023/05/richards-trevallion-legal-aid-rates-australia/

- Sanders, J. (2021). What’s new with section 32? Diversion under the new Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020. May 2021 update. https://criminalcpd.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Whats-new-with-section-32_-May-2021-edition.pdf

- Soon, Y.-L., Rae, N., Korobanova, D., Smith, C., Gaskin, C., Dixon, C., Greenberg, D., & Dean, K. (2018). Mentally ill offenders eligible for diversion at local court in New South Wales (NSW), Australia: Factors associated with initially successful diversion. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(5), 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1508487

- Tyler, N., Miles, H. L., Karadag, B., & Rogers, G. (2019). An updated picture of the mental health needs of male and female prisoners in the UK: Prevalence, comorbidity, and gender differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(9), 1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01690-1

- Vanny, K. A., Levy, M. H., Greenberg, D. M., & Hayes, S. C. (2009). Mental illness and intellectual disability in Magistrates Courts in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 53(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01148.x