Abstract

Offenders who commit sexual offences against children are progressively recognised, prosecuted, assessed and treated. As technology advances, internet child sexual abuse material (I/CAM) offences increase in pertinence to forensic assessment and treatment. A new proposal in I/CAM therapeutics, the Estimated Risk of Internet Child Sexual Offending (ERICSO) is a framework for individualised, risk-relevant treatment formulation based on identified risk factors. An international scoping review of I/CAM treatment programmes was conducted prior to elucidating our proposed treatment model for I/CAM offenders. Combining risk-relevant and compassionate therapies, we propose a treatment framework based on the risk–needs–responsivity model and relevant factors, recognising diversity of I/CAM offenders. Incorporating proven constructs in offender assessment and treatment with specific application to the I/CAM offender cohort, the ERICSO assists professionals to formulate risk-relevant, individual therapy and set meaningful goals. The delivery of compassionate therapeutic interventions to I/CAM offenders will improve rehabilitative outcomes and community protection.

Introduction

Over the past 15 years there has been a rapid change in the nature of serious crime, with a sharp rise in the rate of digital/cyber-related crime compared to a reduction in the rates of face-to-face violent crime, including robbery, homicide and sexual offending (Bryant & Bricknell, Citation2017; Caneppele & Aebi, Citation2019). Child sexual offenders increasingly commit crimes online including, but not limited to, child abuse material (CAM), online interactions through online forums and live-stream webcam sexual offending against children (Bursztein et al., Citation2019). The following summary of the history of internet-based CAM (I/CAM) offences highlights the recency of recognition of these offences from an Australian perspective and the implications for treatment and therapeutic interventions.

Following the historical summary, this paper considers the Australian legal sanctions for I/CAM offences, mandatory reporting and general psychological therapies in Australia. We then focus on the introduction of a new risk assessment and treatment formulation tool for I/CAM offending, and place this in context of an international scoping review of currently available I/CAM treatment programmes.

History of I/CAM offences

In Australia, possession of I/CAM is a state/territory offence. I/CAM offences involving the active use of the internet, such as accessing, trading or making available I/CAM, are commonwealth (or federal) telecommunication offences. An example of the history of the development of I/CAM offences is presented here using the trajectory in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), where CAM offences were first prosecuted as specific offences in 1987 when the employment of people under 18 years for making pornographic material became an offence (Boxall & Fuller, Citation2020; Boxall et al., Citation2014). Four years later, possession of such material was recognised as an offence, and shortly after computer games were included as relevant material. While these offences predate home use of the internet, updated offences include I/CAM, and in 2004 trading in I/CAM was included. Changes in 2018 to the terminology used in relevant legislation resulted in the removal of the term ‘child pornography’, substituted by the term ‘child exploitation material’. reflects the current relevant offences by year of amendment.

Table 1. History and current ACT legislation relevant to I/CAM offences.

highlights the terminology used in Australian legislation and in associated legal proceedings. Although child pornography is no longer a legal term, it remains in common usage in forensic treatment environments. Further, publications use varying terms, including child exploitation material, child abuse material, child sexual exploitation material, online child sexual offending, internet child sexual offending, child sexual abuse imagery and associated abbreviations. While relatively interchangeable, for clarity, this paper will use Internet Child Abuse Material (I/CAM) throughout to clearly specify the focus on the role of the internet in online sexual abuse of children.

While the age of sexual consent in Australia is 16 years, for the purposes of I/CAM offences the Criminal Code (Cth)Footnote1 defines a child as being a person who is under 18 years of age. The definition of child exploitation material encompasses anything representing the sexual parts of a child, or a child engaged in activity of a sexual nature, or someone else engaged in an activity of a sexual nature in the presence of a child; and must be for the sexual arousal or sexual gratification of someone other than the child. I/CAM includes images, videos, digitally altered images/videos, cartoons (traditional and anime) and written stories.

To provide additional protection for children around the world, Australian citizens and permanent residents who commit child sexual offences (including I/CAM-related) outside Australia may be prosecuted under Australian law (Criminal Code s272.8 and 272.9). The intentional importation of I/CAM is an offence (Customs Act 1901, s233BAB (5)).

Mandatory reporting laws

Mandatory reporting of child abuse to government-run, child protection services was first introduced in Australia in 1969 in South Australia (Mathews, Citation2014). Since that time, Tasmania (1975), New South Wales (1977), Queensland (1980), Northern Territory (1984), the Commonwealth (1991), Victoria (1993), the Australian Capital Territory (1997) and Western Australia (2009) have all enacted similar laws (Mathews, Citation2014). Prior to 1984 the states and territories did not detail child sexual abuse; rather, this was encompassed under terminology including ill-treatment, neglect and physical abuse (Mathews, Citation2014). All states and territories of Australia now explicitly mandate the reporting of child sexual abuse. Reports made to government-run child protection services may be referred on to policing agencies for criminal investigation and prosecution.

Mandatory reporting differs between jurisdictions as to whom, of whom and how and when information must be reported. Different jurisdictions mandate reporting of suspicions, beliefs of harm or likely harm resulting in the abuse (including sexual) or neglect of a child (Mathews, Citation2014; Australian Institute of Family Studies; AIFS, Citation2020). Professions with mandatory reporting requirements in all Australian jurisdictions include doctors, nurses, police, teachers, psychologists and a range of other individuals and professions who work with children (AIFS, Citation2020).

Not all countries around the world have mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse (or of I/CAM). Notable countries without mandatory reporting requirements include New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Germany. The absence of such requirements provides an interesting space to consider child sexual offender and I/CAM offender help-seeking and treatment.

General psychological therapies in Australia

Subsidised by Medicare, Australia’s government-funded healthcare scheme, eligible individuals (consumers) can access general and mental health supports, including a range of psychological services at low or no cost (Services Australia, Citationn.d.). In late 2017, Medicare embraced the technology era and commenced subsidising psychological services by telehealth: healthcare consultations conducted using videoconferencing software. Initially targeting consumers in rural and remote areas, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the expansion of the initiative to all eligible mental health consumers (Australian Psychological Society, APS, Citationn.d.). Generally, a consumer can access a maximum of 10 subsidised individual sessions with a psychologist per calendar year. Consumers who choose to pay full fees to access psychological services (i.e. not through Medicare) do not have a session limit. A psychologist may pass the full subsidised cost per session on with no additional cost to a client or may charge a gap payment between the subsidy cost and the full cost per session (which is typical). For a client paying full fees, the APS’s recommended rate is currently AUD$300 per 46-to-60-minute session (APS, Citation2023).

There are professional organisations world-wide dedicated to supporting and providing training for professionals who work with clients who commit sexual offences. These include the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA; USA), the Australian and New Zealand Society for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ANZATSA) and the National Organisation for Treatment of Sexual Abusers (NOTA; United Kingdom). There is no requirement for psychologists providing sexual-offence-specific treatment, including for I/CAM offences, to have completed specific training or be a member of these professional organisations. This highlights the need for structured assessment and treatment of general sexual and I/CAM offenders to ensure delivery of consistent, risk-relevant, evidence-based and individualised pathways.

The Estimated Risk of Internet Child Sexual Offending (ERICSO)

The ERICSO is an empirically developed I/CAM-specific and risk-relevant assessment tool for I/CAM offenders (Garrington et al., Citation2022, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). The risk factors measured in the ERISCO were empirically identified through a rigorous systematic review (Garrington et al., Citation2018). A unique feature of this tool is combination of actuarial risk assessment with structural professional judgement approaches. The ERICSO provides structured guidance to identify dynamic treatment needs and risk variables, to enable and inform treatment programmes focused on changeable treatment issues. Developed using a multi-stage process comprising systematic review, survey of professionals, single-user case study and case series analysis, the ERISCO represents a new assessment/treatment modality (Garrington et al., Citation2022; Garrington et al., Citation2018). Identified risk factors are grouped into domains, namely Demographic, Collection, Nature of Engagement and Social. Preliminary scoring criteria cumulatively consider a higher number of responses selected to indicate more areas of identified risk for treatment formulation. The ERICSO manual and detailed scoring procedures remain in development. Feedback from the professional and user studies combined with existing research has resulted in the ERICSO’s unique contribution to the assessment of the I/CAM cohort.

The single-user case study considered the individual reflections of a male I/CAM offender on the ERICSO items based on his experiences as an I/CAM offender (Garrington et al., Citation2023a). Early indicators from the case series analysis are that the ERICSO has good construct, external and face validity when compared to known assessment tools for the I/CAM and sex offender cohorts, with higher scores on the ERICSO corresponding with higher levels of diversity in online sexual behaviour and increased areas of risk/treatment need (Garrington et al., Citation2023b).

I/CAM offender treatment

Typical treatment for I/CAM offenders is inclusion in general sexual offender group programmes delivered in prison settings or by correctional services rather than I/CAM specific (Magaletta et al., Citation2014). Treatment programmes or treatment plans may not be provided to all offenders, unless offender management departments or agencies have policies to treat all sexual offenders, or offenders are sentenced with attached court orders mandating treatment. Where sexual offenders do not have court-ordered treatment, volunteering for treatment post-conviction without implied coercion (e.g. eligibility for parole may depend on programme completion) can be rare (see Day, Citation2020; Harris & McPhedran, Citation2018). Usually, such treatment occurs when offenders are incarcerated. The authors’ personal experience is that some I/CAM offenders may seek individual treatment from a psychologist, navigating the limitations on sessions, gap fees and full fees as detailed above.

Convictions for I/CAM offending in Australia can lead to a range of imprisonment and/or community supervision orders (see Harris & McPhedran, Citation2018; National Judicial College of Australia, NJCA, Citationn.d.). A sentencing judge may mandate or suggest offence-specific treatment or rely on the supervising authority to offer relevant treatment options. For sentences of imprisonment, judges are generally unable to mandate treatment but can make recommendations. A judge may also sentence an offender to release on a set date with no requirement to apply for parole, thus removing some incentives to participate in a relevant treatment programme (Commonwealth Department of Public Prosecutions, CDPP, Citation2018). State/territory parole boards may take into consideration a detainee’s behaviour and completion of treatment programmes in granting or refusing their release to a parole order.

Treatment in prison has been a particular focus, as incarceration provides a significant opportunity for treatment intervention, and release to a parole order may be dependent on completion of treatment (Crimes Act 1914, s19ALA (1c)). However, a recent commentary by Day (Citation2020) highlighted the challenges facing offender rehabilitation in Australian prisons, noting that it is of highly variable quality. Variations relate to intensity of treatment, quality of treatment and prison social climate as relevant considerations. Arguing for treatment programmes to sit within reintegration and rehabilitation models focusing on family, community and culture, Day highlighted systemic issues facing rehabilitation in correctional environments. In Australia, programmes delivered in prisons may be psychoeducational, motivational or therapeutic, with jurisdictionally different requirements for programme facilitator or therapist qualifications, training and supervision (Heseltine et al., Citation2011). The variation in requirements to work with specific cohorts, such as sexual offenders, does not necessarily ensure a level of competency in therapeutic delivery.

Very few rehabilitation programmes appear to be provided outside correctional services in Australia. The only programme that the authors were aware of in Australia is Owenia House, operated by South Australia Health, providing treatment to community-based adults who have committed or think they may commit a sexual offence against children, including ‘internet-based offences’, although we are unaware whether this includes I/CAM programme content. Consequently, we undertook an international scoping review to identify treatment programmes for I/CAM offenders.

Method

To identify treatment programmes for I/CAM offenders a scoping review of published articles was undertaken. Electronic searches were conducted using available databases including EBSCO Host, Medline, ProQuest, PsychINFO, Google and Google Scholar. Treatment programmes were also identified through reference lists of articles, and several were known to the first author through clinical experience. Search terms used in isolation and combination included internet offender, child abuse material (CAM), internet child abuse material (I/CAM), child pornography, treatment, program and therapy.

Results

A total of five programmes currently delivered world-wide for the I/CAM offender cohort were identified: Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (Germany), Inform Plus (United Kingdom), Troubled Desire (Germany), iHorizon (United Kingdom) and Coping with Child Exploitation Material Use programme (CEM-COPE; Australia). A predecessor to the iHorizon programme, the Internet-Related Sexual Offending Programme (i-SOTP, United Kingdom), was also identified. A review of the programmes, publicly available information, delivery manuals (if available), inclusion and exclusion criteria and relevant publications was undertaken. Relevant to programme entry criteria and this paper, only the iHorizon programme and its predecessor, the i-SOTP, use a risk assessment tool, namely the Risk Matrix 2000 (RM2000). lists the key characteristics of these programmes, and they are described briefly below.

Table 2. Current I/CAM treatment programmes and evaluation/s.

I/CAM treatment programmes

Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (PPD), Germany

Germany provides an interesting comparison point to Australia because it has non-mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse laws. This means men who have or are planning to commit sexual offences against children (including I/CAM) can seek help at any time without fear of prosecution. Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (PPD) is a community-based programme introduced in 2005 by the German Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine. Published research details PPD as providing therapeutic and pharmacological interventions to assist participants to separate desire to commit child sexual offences from offence commission, and to teach control to prevent child sexual fantasy from turning into reality (see Beier, Ahlers, et al., Citation2009; Beier, Neutze, et al., Citation2009). PPD acknowledges that participants may have already committed child sexual offences and provides anonymous and confidential treatments.

Research on PPD programme effectiveness has included individuals who use I/CAM (self-report, undetected by law enforcement) and I/CAM offenders (known to the justice system) but published results do not distinguish between I/CAM and contact child sexual offenders. An internal study by Beier et al. (Citation2015) compared treatment and control groups in the PPD programme, finding that post-treatment effects included decreased emotional deficits and offence-supportive cognitions and increased sexual self-regulation. Specific to I/CAM, 91% (29/32) of the I/CAM participants in treatment and 76% (16/21) of the I/CAM control group (waiting for treatment) relapsed with additional I/CAM use, showing no treatment effect. None of the I/CAM participants had been previously detected by law enforcement. For comparison, 20% (5/25) of the contact child sexual offence treatment group relapsed, and 30% (3/10) of the control group. Of concern, and reflective of the rise in internet sexual offending, 24% (5/21) of the treatment group and 20% (1/5) of the control group admitted to commencing accessing I/CAM during the study period. There is no information provided as to why a quarter of the control group would commence accessing I/CAM while waiting for treatment. A subsequent study on the PPD programme found weak treatment effects (median d = 0.30) across all indicators with none statistically significant (Mokros & Banse, Citation2019).

These results cast doubt on the effectiveness of the PPD programme, highlighting the challenges in providing homogeneous therapy to mixed groups of I/CAM and contact child sexual offenders, as well as potential contagion effects.

Inform plus, United Kingdom

Delivered by the charitable community organisation Lucy Faithfull Foundation since 2005, Inform Plus is a psychoeducational 10-week course to prevent viewing of I/CAM. A single-arm study by Gillespie et al. (Citation2018) found that participants (n = 92) demonstrated significant time effects in increases in positive internet attitudes (distorted thinking, ηp2 = .56, and self-management, ηp2 = .32), social competency emotional regulation (reappraisal, ηp2 = .06 and suppression, ηp2 = .04) and general mental health (depression and anxiety, ηp2 = .08 each, and stress, ηp2 = .12) via improved self-assessment scores on the Depression Anxiety Subscale 21 (DASS–21). A small qualitative study based on self-report and thematic analysis found that I/CAM offenders who completed the Inform Plus programme noted improved self-regulatory behaviours and precipitating feelings to I/CAM offending (Dervley et al., Citation2017).

The evidence for Inform Plus is currently limited to emotional and wellbeing improvements. No publications on rates of reoffending post programme completion have been identified. Interestingly, participation in the Inform Plus programme is paid for by participants and can be delivered in either group or individual format. While no detailed exclusion criteria were identified, the Inform Plus website states that it is only available to people who have been arrested, cautioned or convicted of I/CAM offences.

Troubled Desire, Germany

Also developed by the Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine in Germany, Troubled Desire is an online psychoeducational and self-management programme app. Although the app has been available since 2017, there are no published evaluations available. An internal summary of user demographics and characteristics found that over a 30-month period, 7496 users commenced, and 4161 users completed, the self-assessment module (Schuler et al., Citation2021). Of users who completed the self-assessment module and self-reported a sexual interest in children, 72.8% (n = 2390) admitted accessing I/CAM in their lifetime. This has implications for treatment options, noting that no publicly available information is available on Troubled Desire’s self-management module. No exclusion criteria were identified, and the programme is available online in seven languages.

iHorizon (previously i-SOTP), United Kingdom

The Internet-Related Sexual Offending Programme (i-SOTP) was introduced in 2006 for community-based offenders under the supervision of the National Probation Service (NPS; England and Wales; Middleton, Citation2008). Early outcomes from an internal study (n = 264) included statistically significant (p = .005) increases in socio-affective functioning and decreases in offence-supportive attitudes as assessed using a range of psychometric tools (Middleton et al., Citation2009). This programme ceased in 2017.

Developed by Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) to replace i-SOTP, iHorizon is a group-based programme addressing internet-based offences including possessing, downloading or distributing images of children, but not direct or indirect contact with children. The programme excludes women, participants with severe mental health presentations and/or an IQ under 80 and those scored as low risk (Guide to Group Work Programmes & Individual Interventions, Citation2021, Probation Board for Northern Ireland). iHorizon has not been subject to published evaluation, either internal or external.

Entry criteria are based on assessed risk level using the Risk Matrix 2000 (RM2000), a tool for assessing general risk of sexual reoffending. I/CAM offenders were not included in the original RM2000 development sample, and caution is advised with conservative scoring if applied to this cohort (Thornton, Citation2007).

Coping with Child Exploitation Material Use programme (CEM-COPE), Australia

The CEM-COPE programme was developed in 2019 and delivered through Forensicare (Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health), contracted to Corrections Victoria. CEM-COPE targets offenders who have accessed, possessed or distributed I/CAM material. Offenders who produce I/CAM in the ‘absence of a direct victim’ also meet eligibility criteria; however, CEM-COPE does not include offenders with production of I/CAM or solicitation, nor current or previous contact child sexual offences. Exclusion criteria include those with intellectual disabilities (ID), acquired brain injuries (ABI) or self-harm, suicidal and severe mental health presentations (Henshaw et al., Citation2020).

The programme delivery manual is not publicly available, and programme trials have been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated prison lockdowns (Forensicare, 2021). Thus, no evaluations are yet available.

Identified I/CAM treatment gaps

Of the five current programmes offered worldwide for the I/CAM offender cohort:

three are only available to men who are involved in the criminal justice system (Inform Plus, iHorizon and CEM-COPE),

two are currently only available online (Troubled Desire and Inform Plus),

one is identified as a treatment programme (PPD), and

only one offers pharmacological therapies (PPD).

Three of the five identified programmes (PPD, iHorizon and CEM-COPE) actively exclude participants with significant individual needs such as mental health disorders, intellectual disabilities and acquired brain injuries. The remaining two programmes (Inform Plus and Troubled Desire) do not have publicly available exclusion criteria. The exclusion of participants with significant individual needs from the group context may be necessary for group cohesion and due to facilitator/programme inability to meet individual needs, but is, nonetheless, of significant concern as early research has shown a high level of such needs (e.g. mental health issues) amongst such offenders (Merdian et al., Citation2009).

Three programmes (Troubled Desire, iHorizon and CEM-COPE) have no published evaluation data, and the other two have no robust evidence of effectiveness. This highlights the very early stage of current I/CAM treatment options, the paucity of available treatments and eligible cohorts after exclusionary criteria are applied.

Two further programmes were identified after the scoping review was completed: ReDirection self-help (Healthvillage, Citationn.d.) and Prevent It (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry, Citationn.d.). The programmes were subsequently not included as ReDirection appears to have no published research exploring the efficacy of the programme available and, while Prevent It appears to be subject to ongoing research, it is hosted via the TOR server on the Dark Web (ISRCTN Registry, Citationn.d.) and is unable to be accessed by the present researchers. Given the lack of published research we cannot be certain whether either programme has an effect on reducing risk of I/CAM recidivism for programme participants.

Discussion

Therapeutic approaches

Programmes for sexual offenders generally rely on group-based programme delivery, with Ware et al. (Citation2009) extensively addressing the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. The facilitation of manual-based programmes results in homogenised and modularised psychoeducational or treatment programmes that attempt to address multiple offence types simultaneously. Additionally, the group modality faces the challenge of engaging participants with individual needs, often resulting in exclusion from available programmes. Currently available I/CAM programmes are group based, with a clear gap identified in the availability of individually tailored programme delivery. The need for the development of individual treatment areas is highlighted by Ward et al. (Citation2000). These authors compared and contrasted manual-based treatment (standardised interventions delivered to a cohort assumed to share the same treatment needs) and formulation-based treatment (individualised interventions based on relevant causal factors for clinical phenomena) for sexual offenders. Conclusions for manual-based treatment included the benefits of a standardised approach with less reliance on clinical judgement versus formulation-based treatment advantages for complex clients and/or past treatment failures.

The risk–needs–responsivity model (RNR; Andrews et al., Citation2011) and good lives model (GLM; Ward & Brown, Citation2004) have a significant role in the treatment of individuals in the criminal justice system. RNR promotes the matching of an assessed level of risk to identified needs, delivered in a modality that is responsive to the client’s learning style (Andrews et al., Citation2011). Consequently, an offender assessed as low risk of reoffending with few needs would be provided with a lesser intervention than an offender with high assessed risk and needs. The GLM (Ward & Brown, Citation2004) details 12 areas deemed necessary for an individual to lead a positive, self-fulfilling life. Based on a strengths-based model, GLM focuses on protective factors rather than the RNR focus on risk factors. Arguments have been posited that GLM and RNR both address similar constructs, albeit with different language and approaches (Andrews et al., Citation2011). Mallion et al. (Citation2020) conducted a systematic review (n = 17) into the GLM model and produced mixed findings as to the underlying assumptions. However, they assessed intervention effectiveness to encourage motivation to treatment engagement and change, and were at least as effective as other modalities of treatment.

Two of the identified programmes (iHorizon and CEM-COPE) incorporate the RNR and GLM models, with the remaining programmes being psychoeducational. Psychoeducational models teach information to group participants with the goal of supporting treatment rehabilitation. While this provides an adequate starting point for interventions and may complement treatment, it is not a substitute for psychological interventions (Goldman, 1988, cited in Atri & Sharma, Citation2007).

Tailoring treatment to individual needs

An example of considerations needed for individual differences within I/CAM treatment is provided by persons with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who have accessed I/CAM. Research has found that individuals with ASD can face barriers in accessing mental health treatment, including a lack of therapist knowledge in ASD and the inability or unwillingness of therapists to customise therapy to support an individual’s needs (Adams & Young, Citation2021). An Australian legal analysis focused on a cohort of nine Australians (total 10 cases, including one who faced two trials) with ASD who were charged with I/CAM offences (Allely et al., Citation2019). The analysis considered the interaction between and contribution of diagnosis to online offending behaviour. For the nine individuals, four cases concluded in dismissal of charges, four in sentences of imprisonment and one in a community-based order. The paper highlighted the possible ritual collecting of both legal pornography and illegal I/CAM, absence/reduction in knowledge by the offender as to the illegality and impacts of their actions, and social immaturities, and queried whether possession of I/CAM is always an indication of deviant sexual interests. These considerations are essential in formulating appropriate and targeted treatment to maximise engagement and effectiveness. Although written from a legal standpoint, the paper referred to the necessity to consider the contribution of ASD diagnosis to risk assessment and treatment. While links between ASD diagnosis and I/CAM offending are not clear, the article highlights the need for supportive treatment tailored to individual needs and based on case law; Allely et al. (Citation2019) remarked that this is rare in correctional settings. This is a good example of a cohort with a specific diagnosis who would benefit from individual treatment tailored to specific needs, and yet likely to be excluded from current I/CAM group treatment programmes.

Compassionate therapy

The I/CAM programmes currently available do not, on available information, incorporate a trauma focus, which is critical in this field as co-morbidity is similar for sexual offenders as for members of the community (Aslan & Edelmann, Citation2014). Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) was developed to assist people with chronic and/or complex mental health conditions, recognising the shame and self-criticism often experienced by clients and assisting them to develop a ‘compassionate mind’ (Irons & Lad, Citation2017). Based on internal physiological responses to threat detection and protection, or fight/flight responses, CFT assists an individual to develop social safeness and self-compassion (Gilbert, Citation2009). In the psychological treatment space, CFT practitioners assist clients to firstly recognise and approach their suffering in a supported treatment environment. Secondly, skills development focuses on the client learning to manage symptomology through a range of therapeutic modalities including attention and mindfulness, breathing and body posture work, and developing the compassionate self, all tailored to client need. Recognising the courage and inner strength required by the client to achieve this, CFT recognises the client/practitioner therapeutic relationship as a crucial mechanism to assist change (Irons & Lad, Citation2017).

CFT is transdiagnostic and has been found to have positive effects in increasing self-compassion and reducing mental health symptomology in forensic populations. Results indicate that group CFT had better effectiveness than general individual and self-help interventions (C. Craig et al., Citation2020). There have been several studies of CFT with people who have experienced traumatic events. In a study comparing combined individualised cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and combined CBT/CFT treatment, findings included improved self-compassion and reduction in clinical symptomology over a 12-week period (Beaumont, Citation2012). Although the reductions in clinical symptomology were not significant, and the sample size was small (n = 32), Beaumont (Citation2012) noted the logic of combining the practical, skills-based approach of CBT with the self-compassion of CFT.

Specific to sexual offender cohorts, a 2021 proposal of forensic-CFT (F-CFT) suggests that the harm caused by such offences stems from survival instincts (fight/flight), trauma responses and desire for social inclusion (Taylor & Hocken, Citation2021). Highlighting the positive focus of CFT in forming healthy lifestyles, F-CFT incorporates trauma-sensitive practices into forensic interventions to address risk and enable personal growth. Applying the same concept to men with developmental disabilities who have committed sexual offences, Taylor (Citation2021) applied F-CFT in an active treatment programme. Delivered in a group setting over approximately 18 months, treatment incorporated the phenomenological experiences of participants. At a 12-month follow-up, findings included the reduction of feelings of shame, increased experiences of guilt and insight into participant behaviour. The promising use of F-CFT in sexual offence treatment underscores the potential for increased utility in I/CAM treatment.

There appears to currently be no published research available on individual CFT (or F-CFT), nor on the application of CFT (or F-CFT) to the I/CAM cohort. Recognising the contribution a compassionate approach makes, the authors propose a conceptual framework based on assessed risk factors, incorporating individual needs and delivered from a compassionate therapeutic approach.

Case formulation and link to therapy

Case formulation with sexual offenders is inherent to the management and treatment of risks specific to individuals. Cautioning against assessment for mechanical reasons, Vess et al. (Citation2008) noted the importance of actuarial, static and dynamic risk assessments incorporating causal (developmental and personality) factors. The integration of case formulations in conjunction with risk assessment should be considered in treatment and supervision (Vess et al., Citation2008).

Craig and Rettenberger (Citation2018) published a seminal article on integrating risk assessment measures into the treatment of sexual offenders. They proposed the CAse Formulation Incorporating Risk Assessment (CAFIRA) model. Drawing on the five-factor model of case formulation, CAFIRA links aspects of treatment to specific risk assessment tools, moving from past (static) to offence (stable/dynamic) to present (stable/dynamic) to future (risk monitoring). Though updated versions of the CAFIRA model have been proposed, no research on the efficacy of the model was identified.

Proposed model

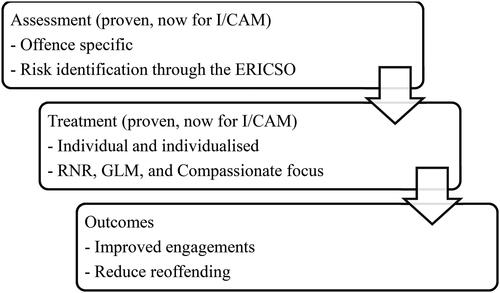

The findings of the scoping study demonstrate the limited number of currently available programmes and even more limited evidence base and clearly evident gaps in the field of I/CAM offender treatment. Based on the scoping study and the development of the ERICSO, shows the key components for a framework for I/CAM assessment and treatment. The first step is an I/CAM-specific assessment to identify risk and, therefore, treatment areas – namely, using the ERICSO. Secondly, treatment formulation and provision must be individually tailored to address the identified risk/treatment areas. This is proposed to result in improved outcomes for I/CAM offender treatment, including better treatment engagement and the reduction of reoffending.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for I/CAM-specific assessment and treatment. I/CAM = internet child abuse material; ERICSO = Estimated Risk of Internet Child Sexual Offending; RNR = risk–needs–responsivity model; GLM = good lives model.

The proposed model (presented below) strongly focuses on the I/CAM offender as an individual with specific treatment needs. While some I/CAM offenders may benefit from group-based, modularised treatment, others, such as those with mental health or psychiatric diagnoses and cognitive disabilities, may not.

The first step, client assessment, expands on existing risk assessment tools for sexual offenders by developing an I/CAM-specific tool, the ERICSO. The authors propose the ERICSO as an assessment tool for the identification of risk factors contributing to I/CAM reoffending and contact child sexual offending. Currently being empirically evaluated, showing good face and external validity to date, the ERICSO is an exciting development in formulating risk-relevant therapies for I/CAM offenders.

The international scoping review identified a small number of I/CAM-specific programmes. The dearth of proven treatments specific to I/CAM risk/treatment areas and exclusionary criteria reveal the importance of the ERICSO’s unique combination of RNR, GLM and compassionate-focused treatment. Clients with backgrounds of trauma, mental health problems and/or cognitive disability may not be comfortable disclosing relevant personal experiences in the group environment. Indeed, this may add to feelings of shame and embarrassment and result in partial participation and inadequate treatment. In comparison, skilled one-to-one treatment, based on both RNR and GLM principles and delivered with a compassionate focus, should enable engagement in targeted treatment and facilitate better outcomes. The incorporation of compassionate therapy techniques into I/CAM treatment both enables and encourages the therapeutic relationship between practitioner and client. The ERICSO supports individual rather than group treatment, providing individualised and supportive therapeutic environments that welcome clients with diverse needs. With an emphasis on inclusivity and supporting individual needs, the ERICSO combines existing concepts and extends them to provide a new framework for I/CAM assessment and treatment.

Conclusion

Mandatory reporting laws in many countries and jurisdictions show the importance of protecting children from sexual abuse. Internet-enabled sexual abuse is a crime that is growing and of increasing concern internationally. Targeted treatment of the diverse range of I/CAM offenders, based on specific assessment and individualised needs identified by the ERICSO, delivered through a compassionate therapeutic style, provides a critically needed opportunity for change for such offenders. Treatment formulation for I/CAM offenders based on the ERICSO draws on established methodologies in sexual offending and mental health cohorts. The authors note that further research and testing of the conceptual framework is required. The authors reiterate that research into the offence pathways and treatment options for I/CAM offenders remains ongoing. Further findings may continue to provide novel contributions to the risk-relevant treatment of the I/CAM cohort.

Reductions in recidivism through effective treatment may see decreased levels of consumption of I/CAM and eventual decreases in the production of such material, which, by its very nature, is predatory and abusive of children. It is our hope that promoting offender behaviour change can directly contribute to reductions in reoffending by I/CAM offenders and enhance the protection of children.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Catherine Garrington has declared no conflicts of interest.

Sally Kelty has declared no conflicts of interest.

Debra Rickwood has declared no conflicts of interest.

Douglas Boer has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Notes

1 Dictionary, Criminal Code (Cth), https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2023C00210/Html/Volume_2; and see also s 3(1) Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), s 4(1), Family Law Act 1974 (Cth)

References

- Adams, D., & Young, K. (2021). A systematic review of the perceived barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in individuals on the autism spectrum. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(4), 436–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00226-7

- Allely, C. S., Kennedy, S., & Warren, I. (2019). A legal analysis of Australian criminal cases involving defendants with autism spectrum disorder charged with online sexual offending. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 66, 101456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101456

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J. S. (2011). The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model: Does adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(7), 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811406356

- Aslan, D., & Edelmann, R. (2014). Demographic and offence characteristics: A comparison of sex offenders convicted of possessing indecent images of children, committing contact sex offences or both offences. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 25(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2014.884618

- Atri, A., & Sharma, M. (2007). Psychoeducation. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 5(4), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.32398/cjhp.v5i4.1266

- Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). (2020). Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/publication-documents/2006_mandatory_reporting_of_child_abuse_and_neglect.pdf.

- Australian Psychological Society (APS). (2023). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://psychology.org.au/psychology/medicare-rebates-psychological-services.

- Australian Psychological Society (APS). (n.d.). Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://psychology.org.au/psychology/about-psychology/what-it-costs#:∼:text=The%20APS%20National%20Schedule%20of,your%20psychologist%20or%20clinic%20manager.

- Beaumont, E., Galpin, A., & Jenkins, P. (2012). ‘Being kinder to myself’: A prospective comparative study, exploring post-trauma therapy outcome measures, for two groups of clients, receiving either cognitive behaviour therapy or cognitive behaviour therapy and compassionate mind training. Counselling Psychology Review, 27(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpr.2011.27.1.31

- Beier, K. M., Ahlers, C. J., Goecker, D., Neutze, J., Mundt, I. A., Hupp, E., & Schaefer, G. A. (2009). Can pedophiles be reached for primary prevention of child sexual abuse? First results of the Berlin Prevention Project Dunkelfeld. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(6), 851–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940903174188

- Beier, K. M., Grundmann, D., Kuhle, L. F., Scherner, G., Konrad, A., & Amelung, T. (2015). The German Dunkelfeld Project: A pilot study to prevent child sexual abuse and the use of child abusive images. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12785

- Beier, K. M., Neutze, J., Mundt, I. A., Ahlers, C. J., Goecker, D., Konrad, A., & Schaefer, G. A. (2009). Encouraging self-identified pedophiles and hebephiles to seek professional help: First results of the Prevention Project Dunkelfeld. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(8), 545–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.002

- Bryant, W., & Bricknell, S. (2017). Homicide in Australia 2012–13 to 2013–14: National Homicide Monitoring Program report. Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Boxall, H., Tomison, A. M., Hulme, S. (2014). Historical review of sexual offence and child sexual abuse legislation in Australia: 1788–2013. Australian Institute of Criminology Special Report. Retrieved May 7, 2022, from https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/special/special-7.

- Boxall, H., Fuller, G. (2020). Brief review of contemporary sexual offence and child sexual abuse legislation in Australia: 2015 update. Australian Institute of Criminology Special Report. Retrieved May 7, 2022, from https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/special/special-9.

- Bursztein, E., Clarke, E., DeLaune, M., Elifff, D. M., Hsu, N., Olson, L., Shehan, J., Madhukar, T., Thomas, K., Bright, T. (2019, May). Rethinking the detection of child sexual abuse imagery on the internet. In The World Wide Web Conference, pp. 2601–2607. https://doi.org/10.1145/3308558.3313482

- Caneppele, S., & Aebi, M. F. (2019). Crime drop or police recording flop? On the relationship between the decrease of offline crime and the increase of online and hybrid crimes. Policing, 13(1), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax055

- Commonwealth Department of Public Prosecution (CDPP). (2018). Sentencing of federal offenders in Australia: A guide for practitioners. Retrieved May 9, 2022, from https://www.cdpp.gov.au/sites/default/files/Sentencing%20of%20Federal%20Offenders%20in%20Australia%20-%20a%20Guide%20for%20Practitioners_300718.pdf.

- Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184

- Craig, L. A., & Rettenberger, M. (2018). An etiological approach to sexual offender assessment: Case Formulation Incorporating Risk Assessment (CAFIRA). Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(6), 43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0904-0

- Day, A. (2020). At a crossroads? Offender rehabilitation in Australian prisons. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 27(6), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1751335

- Dervley, R., Perkins, D., Whitehead, H., Bailey, A., Gillespie, S., & Squire, T. (2017). Themes in participant feedback on a risk reduction programme for child sexual exploitation material offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2016.1269958

- Garrington, C., Kelty, S. F., Rickwood, D., & Boer, D. (2022). The development of the ERICSO – A proposed instrument for internet child abuse material offender assessment. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 24 (4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-07-2022-0033

- Garrington, C., Kelty, S., Rickwood, D., & Boer, D. (2023a). Case study reflections of an internet child abuse material offender informing the development of a proposed instrument. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 13(1), 47–61.

- Garrington, C., Kelty, S. F., Rickwood, D., & Boer, D. (2023b). Case series analysis validation of the ERICSO: A new assessment tool for internet child abuse material offenders. Journal of Forensic Practice, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-12-2022-0066

- Garrington, C., Rickwood, D., Chamberlain, P., & P. Boer, D. (2018). A systematic review of risk variables for child abuse material offenders. Journal of Forensic Practice, 20(2), 91–101. No https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-05-2017-0013

- Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264

- Gillespie, S. M., Bailey, A., Squire, T., Carey, M. L., Eldridge, H. J., & Beech, A. R. (2018). An evaluation of a community-based psycho-educational program for users of child sexual exploitation material. Sexual Abuse, 30(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063216639591

- Guide to Group Work Programmes & Individual Interventions. (2021). Probation Board for Northern Ireland. Retrieved May 15, 2022, from https://www.pbni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-Guide-to-Groupwork-Programmes-and-Interventions.pdf.

- Harris, D. A., & McPhedran, S. (2018). The sentencing and supervision of individuals convicted of sexual offences in Australia. Sexual Offender Treatment, 13(1/2), 1–11.

- Healthvillage, F. I. (n.d.). ReDirection Self-help program. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.mielenterveystalo.fi/aikuiset/itsehoito-ja-oppaat/itsehoito/redirection/Pages/default.aspx#:∼:text=%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8B,you%20away%20from%20using%20CSAM.

- Henshaw, M., Arnold, C., Darjee, R., Ogloff, J. R., & Clough, J. A. (2020). Enhancing evidence-based treatment of child sexual abuse material offenders: The development of the CEM-COPE Program. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice [Electronic Resource], 607, 1–14.

- Heseltine, K., Day, A., Sarre, R. (2011). Prison-based correctional offender rehabilitation programs: The 2009 national picture in Australia. Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved May 9, 2022, from http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30035921.

- Irons, C., & Lad, S. (2017). Using compassion focused therapy to work with shame and self-criticism in complex trauma. Australian Clinical Psychologist, 3(1), 1743.

- ISRCTN Registry. (n.d.). Prevent It: Can internet-delivered psychotherapy reduce usage of online child sexual abuse material? Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN76841676.

- Magaletta, P. R., Faust, E., Bickart, W., & McLearen, A. M. (2014). Exploring clinical and personality characteristics of adult male internet-only child pornography offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X12465271

- Mallion, J. S., Wood, J. L., & Mallion, A. (2020). Systematic review of ‘Good Lives’ assumptions and interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 55, Article 101510. https://awspntest.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101510

- Mathews, B. (2014). Mandatory reporting laws for child sexual abuse in Australia: A legislative history. Sydney: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Retrieved May 4, 2022, from https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/file-list/Research%20Report%20-%20Mandatory%20reporting%20laws%20for%20child%20sexual%20abuse%20in%20Australia%20A%20legislative%20history%20-%20Identification.pdf [Accessed May 3, 2022].

- Merdian, H. L., Wilson, N., & Boer, D. P. (2009). Characteristics of internet sexual offenders: A review. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 2(1), 34–47.

- Middleton D. (2008). From research to practice: The development of the Internet Sex Offender Treatment Programme (i-SOTP). Irish Probation Journal, 5, 49–64.

- Middleton, D., Mandeville-Norden, R., & Hayes, E. (2009). Does treatment work with Internet sex offenders? Emerging findings from the Internet Sex Offender Treatment Programme (i-SOTP). Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600802673444

- Mokros, A., & Banse, R. (2019). The “Dunkelfeld” project for self-identified pedophiles: A reappraisal of its effectiveness. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(5), 609–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.02.009

- National Judicial College of Australia. Sentencing Child Exploitation Offences (NJCA). (n.d.). Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://csd.njca.com.au/principles-practice/categories-of-federal-offenders/sentencing-child-exploitation-offences/.

- Services Australia, Medicare. (n.d.). Retrieved May 5, 2022, from http://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/medicare.

- Schuler, M., Gieseler, H., Schweder, K. W., von Heyden, M., & Beier, K. M. (2021). Characteristics of the users of troubled desire, a web-based self-management app for individuals with sexual interest in children: Descriptive analysis of self-assessment data. JMIR Mental Health, 8(2), e22277. https://doi.org/10.2196/22277

- Taylor, J., & Hocken, K. (2021). Hurt people hurt people: Using a trauma sensitive and compassion focused approach to support people to understand and manage their criminogenic needs. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 23(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-08-2021-0044

- Taylor, J. (2021). Compassion in custody: Developing a trauma sensitive intervention for men with developmental disabilities who have convictions for sexual offending. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 15(5), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-01-2021-0004

- Thornton, D. (2007). Scoring Guide for Risk Matrix 2000.0/SVC. Retrieved May 14, 2022, from www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-les/psych/RM2000scoringinstructions.pdf.

- Vess, J., Ward, T., & Collie, R. (2008). Case formulation with sex offenders: An illustration of individualized risk assessment. The Journal of Behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim Treatment and Prevention, 1(3), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100450

- Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health and Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science, Swinburne University of Technology. (2021). Annual Research Report 2020–2021. Retrieved May 15, 2022, from https://www.forensicare.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CFBS-Annual-Research-Report-2020-2021.pdf.

- Ward, T., & Brown, M. (2004). The Good Lives Model and conceptual issues in offender rehabilitation. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160410001662744

- Ward, T., Nathan, P., Drake, C. R., Lee, J. K., & Pathé, M. (2000). The role of formulation-based treatment for sexual offenders. Behaviour Change, 17(4), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.17.4.251

- Ware, J., Mann, R. E., & Wakeling, H. C. (2009). Group versus individual treatment: What is the best modality for treating sexual offenders? Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 2(1), 2–13.