Abstract

In NSW Local Courts, defendants with a mental health impairment or a cognitive impairment may be diverted into treatment. The current study aimed to understand the factors that influence courts when making diversion decisions. Our approach involved a survey of magistrates and an analysis of the treatment plans and reports provided to courts. The issues with the highest importance ratings were the quality and detail of the treatment plan, the seriousness or violence involved in the offence/s, the availability of treatment and the severity of impairment. Opinions among magistrates on the percentage of applications for diversion without merit varied, but the average was 44%. The analysis of treatment reports revealed that defendants were more likely to be diverted if the report had been written by the Statewide Community Court Liaison Service, or if the defendant was currently receiving treatment or had been diagnosed with schizophrenia or a cognitive impairment.

Introduction

The prevalence of mental illness in populations coming into contact with the criminal justice system has been shown to be consistently high internationally (Al-Rousan et al., Citation2017; Bebbington et al., Citation2017; Tyler et al., Citation2019) and in Australia (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, AIHW, Citation2019, Citation2021; Baksheev et al., Citation2010; Butler et al., Citation2011; Forsythe & Gaffney, Citation2012; Jones & Crawford, Citation2007; Ogloff et al., Citation2015; Vanny et al., Citation2009). Most Australian States and Territories have attempted to address this overrepresentation via legislation that enables courts to dismiss the charges against a defendant and divert them into mental health treatment.

Up until 2020, in New South Wales (NSW) the power to dismiss a charge and refer a defendant to mental health treatment was exercised under Sections 32 and 33 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW) (hereafter referred to as the MHFPA). Section 32 enabled a magistrate to dismiss the charge/s and discharge a defendant with a mental health or cognitive impairment into the care of a person or place in the community (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). A particularly important factor for diversion via Section 32 was a treatment plan provided to the court by a mental health clinician such as a psychologist or psychiatrist. This necessity and importance of treatment plans, particularly for more serious offences, is well established in the case law (DPP v Albon, Citation2000; DPP v El Mawas, Citation2006; DPP v Saunders, Citation2017; Perry v Forbes, Citation1993). Section 33 applied to defendants considered ‘mentally ill’ under the Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). Mentally ill individuals are defined in section 14 of that Act as those who need ‘care, treatment and control’ to protect themselves and/or others, and a section 33 order enabled a person to be involuntarily detained in a mental health facility for assessment and treatment (Buchanan, Citation2020).

In 2020, the MHFPA was repealed and replaced by the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020 (NSW) (hereafter referred to as the MHCIFPA). The equivalent parts for sections 32 and 33 in the new legislation are Part 2 Division 2 and Part 2 Division 3, of the new Act respectively. The discretion to dismiss a charge and divert a defendant into treatment appears in sections 14 and 19 of the MHCIFPA. The main changes in the new legislation are an increase in the enforcement period for a section 14 (formerly section 32) order from 6 months to 12 months, the inclusion of ‘mentally disordered persons’ in sections 18, 19 (formerly section 33; in addition to ‘mentally ill’ persons) and a list of factors that a magistrate may consider when dealing with a section 14 application, all of which were already established in case law or the prior legislation (Sanders, Citation2021). These factors, as laid out in the MHCIFPA are:

The nature of the mental health impairment or cognitive impairment.

The nature, seriousness and circumstances of the alleged offence.

The sentencing options available if the defendant is found guilty of the offence.

Relevant changes in the circumstances of the defendant since the alleged commission of the offence.

The defendant’s criminal history.

Whether the defendant has previously been dismissed via orders in MHFPA or the MHCIFPA.

Whether a treatment or support plan has been prepared and the content of that plan.

Whether the defendant is likely to endanger themselves or others.

Other relevant factors.

Magistrates exercise a great deal of discretion when making decisions under sections 32 or 33 of the MHFPA (or equivalent sections of the MHCIFPA; Judicial Commission of New South Wales, Citation2023). The criteria laid down in legislation for making these decisions are only advisory. The broad discretion enjoyed by the Local Court arises from the fact that, in reaching a decision, a magistrate must balance two competing interests. The first is that defendants in criminal proceedings should experience the ‘full weight of the law’ (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). The second is the need to treat those whose crimes are due to mental illness in the interest of protecting the community (Fernandez, Citation2007; Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008).

The range of factors a magistrate may consider and the requirement to balance competing considerations have had measurable effects on who is diverted into mental health treatment and who is not. Soon et al. (Citation2018) analysed court outcomes for 8317 individuals assessed as eligible for diversion via the NSW State-wide Community and Court Liaison Service (SCCLS)Footnote1 and found that only 57.3% of defendants eligible for diversion were diverted by magistrates. Of the 57.3% who were diverted, only 25% were diverted via Section 32 or 33. Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) used data from NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research’s (BOCSAR) Re-offending Database (ROD) and linked it with administrative health data to identify anyone who had been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder and who had been accused of at least one criminal offence between 2001 and 2012. Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) found that only 26% were diverted and that those diverted included a higher proportion of defendants who were older, non-Indigenous, married, Australian born, residing in a higher socioeconomic status area at the time of most recent diagnosis, and who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (as opposed to an affective or substance-related psychotic disorder).

Research has also found considerable variation between magistrates in their willingness to divert mentally ill or cognitively impaired defendants into treatment. Macdonald and Weatherburn (Citation2023) utilised a sample of individuals represented by Legal Aid and linked this data with BOCSAR’s reoffending database (ROD). They found substantial variation in the willingness of magistrates to divert defendants seeking a dismissal of charges and referral into mental health treatment, even after controlling for the factors magistrates are required to consider when making mental health treatment referral decisions. Macdonald and Weatherburn (Citation2023) also found a number of non-legal factors correlated with the decision to refer (or not refer) a defendant into mental health treatment. Male defendants and Indigenous defendants, for example, were found to be less likely to be diverted via Section 32 than female defendants or non-Indigenous defendants.

The studies by Soon et al. (Citation2018), Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) and Macdonald and Weatherburn (Citation2023) have provided considerable insight into what happens to defendants seeking to have charges dismissed on the grounds of mental health impairment or cognitive impairment (hereafter referred to as ‘mental health diversion’). At the same time, these studies were necessarily limited by the information that could be extracted from official criminal justice and health information systems. In this article, we analyse two other valuable sources of information bearing on this issue. The first is a survey of magistrates that was conducted to obtain a better understanding of the factors they rate as important in making decisions about mental health diversion. The second (referred to hereafter as the treatment report study) is an analysis of the reports and treatment plans submitted by psychiatrists, psychologists and other mental health clinicians in support of applications for mental health diversion. Both sources are valuable because both contain information not routinely captured in the information systems of the justice and health departments. In this study we utilise both of these sources of information. Our aims in conducting the two studies are fourfold:

To rank the importance to magistrates of a set of legal and non-legal factors in making decisions about mental health diversion.

To measure the level of agreement between magistrates on the relative importance of these factors.

To quantify the percentage of applications for mental health diversion that magistrates regard as ‘without merit’.

To identify the features of treatment plans correlated most strongly with the decision to grant an application for mental health diversion.

The magistrate survey

Method

Survey content

The content of the survey was developed in consultation with senior magistrates and staff from the Chief Magistrate’s office. These consultations were very helpful in identifying the issues likely to be salient to magistrates when making mental health diversion decisions. Many of the factors we asked magistrates about are included in the list of considerations that have been added to the recent legislation, as we previously outlined. To determine the relative importance of various factors in making decisions under section 32 or 33 of the MHFPA (or section 14 or section 19 of the MHCIFPA), each magistrate was sent an online questionnaire and was asked to rate the importance of 14 matters (on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 = not very important, and 10 = very important):

The availability of treatment.

The quality/detail of a treatment plan.

The violence of an offence.

The seriousness of the offence.

The defendant’s criminal history.

The defendant’s prior mental health dismissal outcomes.

The 6-month enforceable limit under the old act (the MHFPA).

The penalty of the offence.

The prevalence of the offence.

The severity of the defendant’s mental health or cognitive impairment.

Whether the defendant’s mental health or cognitive impairment involved drug use.

Whether the defendant’s mental health or cognitive impairment involved depression.

Whether the defendant’s mental health or cognitive impairment involved schizophrenia.

The credibility of the specialist advising the court on a defendant’s mental health or cognitive impairment.

To allow for the possibility that ratings of the relative importance of these matters might vary depending on the age, experience and gender of the magistrate, respondents in the survey were asked about these factors, as well as their location (regional vs. metropolitan) and whether they worked in the NSW Childrens Court or the NSW Local Court. To gauge interest in receiving more feedback on the outcomes of diversion decisions, magistrates were also asked the following questions:

Have you ever received feedback from treatment staff on the outcome of a case where you have made an order that a defendant be detained in a mental health facility?

Have you ever received feedback from treatment staff on the outcome of a case where you have made a community treatment order?

Would it be of benefit to you to receive feedback from treatment staff on the outcome of cases where you have made a detention order or a community treatment order?

Would it be of benefit to you to receive feedback on the effectiveness of treatment orders under the MHFPA or the MHCIFPA in reducing re-offending?

Magistrates were also asked to choose a number between 1 and 100 to represent their view of the proportion of applications under section 32 or section 33 of the MHFPA or section 14 or section 19 of the MHCIFPA that, in their view, are ‘without merit’. In the final section of the survey, magistrates were given an open-ended question inviting them to offer any other pertinent comment they wished.

Survey administration

The survey was delivered online using the platform Qualtrics. All magistrates currently working in NSW Local and Children’s Courts were eligible to participate and were informed of the survey and provided with a link to it via email from the Office of the Chief Magistrate. Approximately two weeks after the initial email, all magistrates were sent a follow-up email reminding them of the survey to encourage participation. Magistrates were advised that the survey was entirely voluntary and the results completely anonymous. They were also advised that they may withdraw from the survey at any time and that if this course of action was chosen, their survey data would be destroyed. The survey was approved by UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The nominal response rate to the survey was 44%, although some of those who did not respond may have been on leave, two were appointed judges of the NSW District Court, and six retired during the year of the survey.

A total of 62 magistrates completed the survey. Forty-seven per cent were female, and 52% were male (1 participant preferred not to state their gender). The largest age group comprised those aged 61–75 years old (45%). The majority (89%) worked in the Local Court and in metropolitan areas (58%).Footnote2 Most of the sample had been a magistrate for either 11–20 years (39%) or 1–5 years (37%). The overwhelming majority (84%) of the sample had dealt with more than 40 section 32 or 33 cases.

The treatment report study

Method

Data source

There are two data sources for the treatment report study. The first consists of the court record data – the reoffending database (ROD) – provided by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) for use in the study conducted by Macdonald and Weatherburn (Citation2023). The second consists of the treatment plans held in court files maintained by the NSW Local Court office.

Data linkage

Each person who has appeared in a NSW court has a unique code, known as their H-number. Following approval from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Human Research Ethics Committee, the procedure for linking these two datasets proceeded as follows:

Step 1: The first author selected all cases (n = 156) dealt with in the Downing Centre Court ComplexFootnote3 between 2017 and 2019 and involving applications for dismissal under section 32 or section 33. The H-numbers for each of these cases were forwarded to BOCSAR.

Step 2: BOCSAR used the H-numbers to obtain the names and case numbers of persons seeking charge dismissal under section 32 or section 33 and forwarded this information to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the NSW Local Court.

Step 3: The CEO of the NSW Local Court then arranged retrieval of the relevant files and made them available to the first author on condition that these files were coded on-site, and that no identifiable information was recorded. Although 156 cases were identified, only 95 of the treatment reports could be matched to the corresponding ROD records.Footnote4 The small number of treatment reports limited the analysis to cross-tabulations between treatment report feature and section 32 outcome.

Coding of treatment reports

It is firmly established in case law that ‘clear and effective’ treatment plans must be available to magistrates before making section 32 decisions (Gotsis & Donnelly, Citation2008). Our analysis of treatment plans was primarily designed to identify features of the treatment plan that count toward it being viewed as ‘clear and effective’ in the expectation that this would shed more light on the decision to refer a defendant for treatment. In addition, two psychiatrists with forensic experience were consulted to obtain their views on features of a treatment report that they consider particularly relevant to section 32 or section 33 decisions. Appendix Table A1 provides a copy of the coding sheet developed following these consultations. The key items of information collected are listed below:

Whether the report was written by the SCCLS.

If the report was written by the SCCLS, whether the report was supplemented by information from treating clinician/place.

Profession of clinician writing the report (psychiatrist, psychologist, other).

Professional experience (in years) of clinician.

Whether the clinician knew and had treated the client before their offence.

Whether the clinician notes a clear link between the client’s offending and their mental health or cognitive impairment.

Whether the clinician mentions current or recent substance use.

Whether the clinician mentions either prescribing or continuing medication.

Whether the clinician mentions clear treatment goals for the client.

Whether the clinician mentions clear responsibilities for the client as part of their treatment plan.

Whether the client/defendant is currently receiving mental health (MH) treatment.

Number of mental health or cognitive impairments the client/defendant is said to have.

Type(s) of mental health or cognitive impairment experienced by the client.

Whether the clinician recommends diversion via section 32 or 33.

Whether the clinician mentions the potential benefits of diversion.

Length of treatment report (in pages).

Analysis

Due to the small number of linked treatment reports available, the analysis was restricted to the bivariate association between variables drawn from the treatment report and the outcome of the dismissal application. Due to the small cell frequencies in many tables, significance testing was carried out using Fisher’s exact test for some comparisons.

Results: magistrate survey

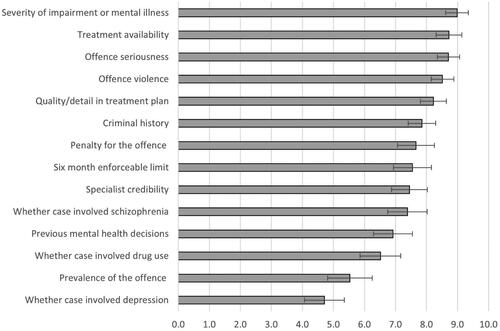

Ratings of importance

shows the mean ratings given to each of the items 1–14, listed above. The issues have been ranked from least to most important. The whiskers on each bar show the 95% confidence intervals surrounding each estimate of importance. The five issues with the highest mean importance rating are the quality and detail of the treatment plan, the seriousness of the offence, whether the offence/s involved violence, the availability of treatment and the severity of the mental health or cognitive impairment.

We found no significant impact of age or gender on ratings of importance for any of the issues we asked magistrates about. Magistrates with more than 20 years of experience rated drug use as a more important consideration than did magistrates with 1–5 years of experience (5.52). Magistrates aged 61–75 years of age rated specialist credibility as more important than did younger respondents, but this difference was only significant when compared with magistrates aged 51–60 years of age. No other demographic correlates of rated importance were found.

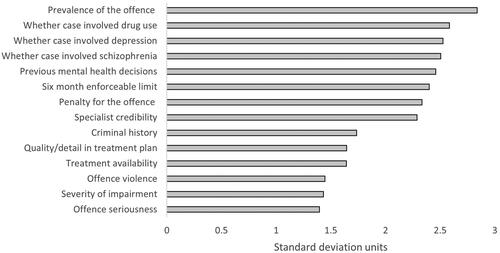

Magistrate variation in importance ratings

provides information on the rated importance of various issues to magistrates making mental health diversion decisions. It does not, however, provide any insight into the extent to which magistrates agree on the relative importance of those same issues. One way to measure the level of disagreement is to calculate the standard deviation of importance ratings for each issue. A high standard deviation indicates a high level of disagreement. shows the level of disagreement between magistrates on the relative importance of the issues listed in .

As can be seen from , the issues on which there is the greatest level of disagreement are prevalence of the offence, whether the offence involves drug use and whether the claimed mental health problem involved depression or schizophrenia. There are also moderate levels of disagreement in relation to the importance of previous mental health decisions, the 6-month enforceable limit, the penalty for the offence and specialist credibility. Consensus on rated importance is most noteworthy in relation to offence seriousness and violence, severity of the mental health or cognitive impairment, treatment availability and the quality of the treatment plan.

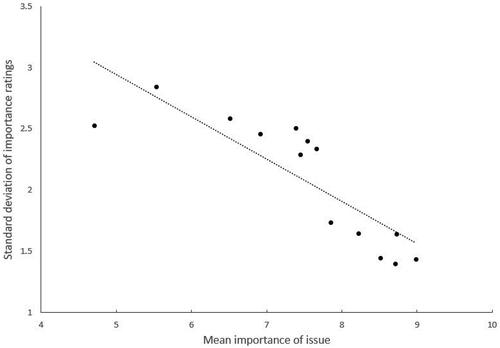

Relationship between level of importance and level of agreement

There is clearly less to be concerned about when magistrates differ in their rating of an issue that has a low average importance rating than when they differ in their rating of an issue that has a high average importance rating. This can be explored by plotting the relationship between the mean importance rating of each issue and the level of disagreement (standard deviation) of ratings. If there is greater consensus on important issues, an inverse relationship would be expected. In other words, the higher the average importance rating, the smaller the standard deviation of the ratings. shows a scatterplot of this relationship. There is clearly an inverse relationship between the mean rating of importance and the standard deviation of ratings. Put simply, magistrates agree more on what is important when making diversion decisions than they do on matters they regard (on average) as less important.

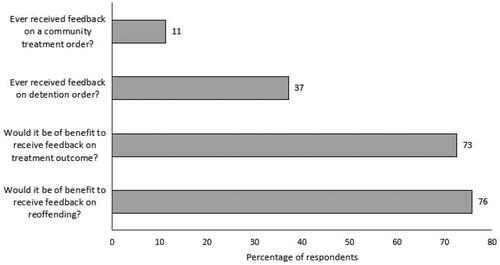

Importance of feedback

The first two bars in show the percentage of respondents in the survey who have ever received feedback on a community treatment order they have made (top bar) or on a detention order they have made (second top bar). Magistrates appear to receive very little feedback on the orders they make. Fewer than 12% of those surveyed had received feedback on a community treatment order, most of which would have involved section 32 decisions. A little over a third (37%) had received feedback on the outcome of a detention order. There is, by contrast, strong interest in obtaining feedback on treatment outcomes (73%) and reoffending (76%).

Percentage of applications without merit

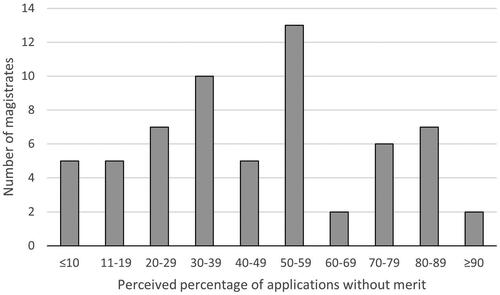

On average, magistrates reported that 44% of applications for dismissal of charges on mental health grounds were categorised as ‘without merit’. It is important to note that there was considerable variation amongst magistrates in relation to the proportion of applications they believed were without merit, with responses ranging from 5% to 91% (as shown in ), and a standard deviation of 24. Eleven of the 62 magistrates indicated that 50% of the applications they dealt with were without merit.

Free responses

Unmeritorious applications

The issue of unmeritorious applications also attracted a number of comments in the free response section of the questionnaire. According to one respondent:

Applications for diversion are too prevalent and made in many cases without any real merit and almost as a matter of routine. The over and inappropriate use of the applications is adding to both the workload of the Court and is extending the time required to finalise matters, as adjournments are required to obtain the supporting reports, often more than one, and the applicant invariably wants to proceed directly to sentence if the application is refused. In the larger metropolitan court complexes that run separate sentence lists it has almost become the norm in each matter to be confronted with an application for diversion and then the sentence if the applications fails, which substantially increases the time required to complete each matter and which in turn limits the number of matters that can be listed on any day. The applications are also now commonly made in fine only and driving offences, including PCA, seemingly motivated by nothing more than a desire to retain a driver’s licence, which is also delaying the time to resolution and clogging up general lists. Applications for diversion should be limited to more serious offences.

The incidence of non-meritorious applications weakens the entire system and perhaps leads to a degree of unconscious resistance on the part of magistrates. The applications take a lot longer to determine than a matter proceeding according to law. In busy lists, a non-meritorious application, which you still have to read in full, and hear submissions on, attaches an unnecessary stigma to applications in general. It would be useful, for example, if there was a higher threshold. For example, a practitioner must have a certain degree of experience or qualification (not a first-year psychologist) and warrant that the application has merit under the Act. Just as legal practitioners must certify when commencing proceedings.

Lack of feedback

The absence of any feedback on the outcomes of referrals to treatment also concerned a number of magistrates. As one survey respondent commented:

Neither the new or the old legislation has a credible and effective method of reporting breach of an order under s 32 or s 14. The method set out in each is via Community Corrections. Community Corrections are not in any way involved in the granting of the order or the monitoring of it, so do not have any mechanism in place regarding oversight of same.

The biggest issue is the lack of response from health professionals that there has been a breach of the conditions. I have never received notice over hundreds of applications.

Section 33 referrals

Three magistrates commented specifically on section 33 referrals. All were concerned with the fact that defendants sent to a mental health care facility under section 33(1)(b) were (as they saw it), frequently returned to court with no explanation provided other than that the accused was not mentally ill. These free responses are below:

If we make a 33(1)(b) order to send accused to mental health facility and the accused comes back some reasons beyond the bare minimum would be helpful (beyond not found to be mentally ill). Often, we find sending the accused to a different facility often results in admission.

Section 33/19 orders are unworkable. The intention of the section is to have a person detained in a mental health facility if they appear to be mentally ill. I had an individual who was clearly delusional, medical reports provided to the court confirming this. Legal Aid were unable to obtain proper instructions from the individual. I made two orders referring the individual to a mental health facility. On each occasion the defendant was referred back to the court within days indicating with a statement by Psychiatrists saying he was not mentally ill. When the defendant was brought before court, he again expressed delusional thoughts. Legal Aid still cannot obtain proper instructions. What is the court to do with the matter? In my view the court should be able to refer the defendant to the Mental Health Review Tribunal rather than a psychiatrist who provides no proper report to the Court. At present there is no mechanism for MHRT to potentially consider a Community Treatment Order under Section 51 of the Mental Health Act. As a consequence, defendants who should be dealt with within the mental health processes are dealt with within the criminal justice system and are often imprisoned and their mental health worsens.

In my view s 33 referrals are not being properly addressed by NSW Health. I have seen defendants who are floridly mentally ill sent back to court without admission despite credible presentation of significant mental illness. To me this is negligent and should be addressed. I appreciate that there are limited beds, but Magistrates do not frivolously refer defendants for assessment with a possibility of detention. It is done with great care and consideration. In my experience including before I became a Magistrate, I have not seen a single person kept in a psychiatric treatment ward of a hospital. In my view the assessing staff are routinely not discharging their duty of care in relation to these patients.

Mental health impairments and illicit drug use

In earlier research, individuals whose mental health problem was associated with the use of illicit drugs were less likely to be diverted into mental health treatment than those whose mental health problem was not associated with such use (Macdonald et al., Citation2023). The comments on this issue in the open-ended section of the report suggest a rather sceptical view of drug-related mental health impairment as evidenced in the following two comments (from different magistrates):

It is difficult to work out in some cases whether or not illicit drug use is the major factor rather than a mental health problem. It is generally more often than not a combination of both. More inclined to grant an application if no drug use and it is a straight-out mental health problem.

The diversionary scheme is an essential tool/outcome. It can be misused, e.g. – where for example very common offences (possession of drugs/supply of drugs) are linked with anxiety and depression for no apparent reason other than a one-off report from a favourable psychologist. This is when it becomes difficult – given that conditions like that are so common and so readily diagnosed within the community. I do favour psychiatrists’ input, rather than a Counsellor/psychologist – perhaps reflects my age/some cynicism. Frankly an industry has grown up around these applications. I have developed a sense of which applications fit into that category however, and, as above, those cases are the exception rather than the rule.

Results: treatment report

Descriptive statistics

Of the 95 treatment reports that could be matched to the dataset, 52% of the sample reportedly had only one mental health/cognitive impairment diagnosis, while 44% reportedly had two or more diagnoses. The most common diagnoses were schizophrenia (50%), substance-related mental illnesses (34%) and cognitive impairments, including intellectual disability (25%). Additionally, 24% of people were coded as ‘other’ for their mental health or cognitive impairment. The majority of these people were described as having a personality disorder. The majority of reports (64%) were written by staff at the SCCLS. Almost all (88%) were said to be receiving mental health treatment at the time the report was written. The majority (63%) were dismissed via section 32. The remainder were prosecuted. No-one in the sample had their charge(s) dismissed via section 33. Interestingly, only 19% of reports described a link between the offending and the mental health or cognitive impairment. Only 17% outlined treatment goals for the individual.

Bivariate correlates of charge dismissal

shows the bivariate relationship between each of the items coded from the treatment reports and whether or not the defendant was referred for treatment.

Table 1. Bivariate relationships between treatment plan characteristics and diversion.

No significant relationship was found between diversion and whether the clinician knew the client, whether the report mentioned clear treatment goals, whether the report mentioned that the clinician had prescribed medication or whether the report noted that the defendant suffered from depression, bipolar disorder, a substance-related mental disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). There was also no relationship between dismissal and the length of the report.

Defendants were more likely to be diverted into treatment if the report had been written by the SCCLS, if it noted that the defendant was currently receiving treatment or if the defendant had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, a cognitive impairment or an intellectual disability. They were significantly less likely to be diverted into treatment if the report mentioned a link between the offending and mental health or cognitive impairment, though it is important to note that almost 80% of reports did not mention a link.

Discussion

Overall, magistrates rated most of the factors they were asked about as highly important. The five most important issues were the severity of the mental health or cognitive impairment, treatment availability, offence seriousness and violence, and the quality and detail in the treatment plan provided to the court. Surprisingly, for all but one of the factors they were asked about, no differences emerged across any of the demographic variables in the ratings of importance. That is, being an older magistrate or working in a regional court compared to a metropolitan court did not affect how important an issue was regarded. Similarly, magistrates who had been working in their role for a longer period of time did not differ significantly from magistrates with less experience, except for the issue of how important drug use was.

We found that magistrates disagreed somewhat on how important they rated the various factors, but that the more important an issue was, the more magistrates tended to agree with one another. For example, magistrates tended to agree with one another on the importance of offence seriousness and the severity of mental health or cognitive impairment, but disagreed more with one another on the importance of the prevalence of the offence or whether a case involved drug use. In its report on people with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system, the NSW Law Reform Commission recommended that greater legislative guidance be given to the courts on the exercise of their discretion in relation to such people (New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Citation2012, pp. 252–253). The newly enacted MHCIFPA now lists factors that magistrates may consider when making diversion decisions. The list, however, remains advisory. It will be interesting to see whether the inclusion of these factors in legislation reduces the level of disagreement evident in the lower half of .

It is not surprising that magistrates disagree more on matters they rate as less important than on matters they rate as more important. A more troubling finding is that 19 of the 62 magistrates indicated that more than 50% of the applications they dealt with were without merit. This is not because these magistrates had dealt with comparatively few cases. Seventeen of them had dealt with more than 40 applications for charge dismissal on mental health grounds. The remaining two had dealt with more than 11 applications.

The overwhelming majority of magistrates would clearly appreciate greater feedback on reoffending and treatment outcomes, so it is troubling to see that 40% report never having received it. Feedback on the outcomes of court orders relating to mental health is arguably crucial to building judicial confidence in the mental health diversion process, especially given the broad discretion vested in magistrates when deciding whether or not to dismiss the charges against a defendant and divert them into treatment. While the survey itself did not ask magistrates to identify the form and types of feedback they would like, it is useful to distinguish between feedback on individual cases and feedback on the overall operation of the scheme. The first issue was discussed in NSW Law Reform Commission Report 135 (New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Citation2012, pp. 257–260). Submissions received by the Commission raised several concerns about any proposed requirement to report individual non-compliance with the court’s orders. They include the possibility that formally requiring reporting of patient non-compliance with treatment plans may limit the number of services willing to carry out treatment plans under section 32, the possibility that such reporting would harm the therapeutic relationship between clinician and patient, and the possibility that it would place defence lawyers at odds with their duty to protect the interests of their clients (New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Citation2012, pp. 257–260).

It is hard to see a principled objection to routine monitoring and evaluation reports, especially if they involve regular reports on the percentage of cases involving significant non-compliance with the court’s order (e.g. not attending treatment) and reasonable consensus can be reached on what constitutes serious non-compliance. At present, public data on diversion into mental health treatment are extremely limited. The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research publishes statistics on the number of cases finalised via section 14 or section 19 of the MHCIFPA but keeps no record of the number of applications for such dismissal. It is therefore impossible to monitor the percentage of Section 14 or 19 applications that are successful, identify changes in the characteristics of cases that are successful or to determine what happens to those whose applications for charge dismissal are unsuccessful. Feedback on these issues would surely be of interest to all those concerned about the way the criminal justice system deals with those who have a mental health or cognitive impairment.

The treatment report study, albeit limited by the small sample size, is the first study to examine the treatment plans and clinician reports provided to the courts in section 32 or 33 applications. The importance of treatment plans is well established in caselaw, and the reports contain information likely to influence decision-making, such as mental health and cognitive impairment diagnoses. These reports, however, are an important source of information that is inaccessible via current databases like the ROD. The results of the treatment report study build upon and complement past research and the magistrate survey in a number of ways.

Firstly, 50% of the sample had schizophrenia, and 25% had a cognitive impairment or intellectual disability. Both of these conditions were associated with an increased likelihood of diversion. These results reinforce the idea that many people coming before the Local Court have complex mental health issues and/or needs and emphasises the importance of affording such individuals with legal representation and clinical assessment. The fact that schizophrenia was associated with an increased likelihood of diversion in the treatment reports data is in-line with the results of past research as well as the results of the magistrate survey. The survey revealed that whether a case involves schizophrenia is an important consideration for magistrates, with those completing the survey rating it an average of 7.5 out of 10 in importance. In past research, Albalawi et al. (Citation2019) and Macdonald et al. (Citation2023) found that those with schizophrenia were more likely to be diverted than those who had a substance-induced psychotic disorder.

The evidence of the treatment reports showed that section 32 diversion was higher for people assessed by SCCLS as opposed to private clinicians. Previous studies have found differing results regarding the SCCLS. In a study of individuals diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, Macdonald et al. (Citation2023) found a significant but modest positive effect of the SCCLS on the odds of diversion (odds ratio, OR = 1.25). In the broader sample from which the current treatment report study is drawn, Macdonald and Weatherburn (Citation2023) only found an effect of the court liaison service on section 33 cases. The difference between the previous studies and the present one is that in the present case, we had information on whether the defendant actually utilised the court liaison service. The current results therefore indicate that the SCCLS is a valuable service for people presenting to court, especially for those with serious mental health or cognitive impairments and those who experience economic disadvantage. These results are particularly encouraging given that the NSW Government has committed $13.4 million to expanding the SCCLS to more Local Courts across the State (NSW Government, Citation2022).

The result regarding the SCCLS raises some questions about why reports written by SCCLS clinicians are more favourable than those of private clinicians. In the magistrate survey, magistrates rated the specialist credibility at about 7.5 out of 10. Perhaps clinicians working at the SCCLS appear more credible to magistrates than private clinicians. Part of this perceived credibility may be due to magistrates’ familiarity with SCCLS clinicians. As the same clinicians work at the same courts and write and provide many reports to magistrates, this familiarity may encourage confidence within magistrates. The survey results also revealed that there is a lot of variation in magistrates’ beliefs about how many applications are unmeritorious, and a number of free responses expressed opinions to this effect. It could be that reports written by SCCLS clinicians are perceived as more legitimate by magistrates, as presumably many of the defendants utilising the service are impacted by socioeconomic disadvantage, and thus utilising this service is perceived as a genuine need for mental health assessment and assistance.

The results of the current research must be considered in light of its limitations. Firstly, although the response rate to the survey was acceptable, we cannot be sure that the views of those who participated in the survey are representative of all magistrates. Secondly, although the survey was voluntary and anonymous, we have no means of checking the responses to the survey and have of necessity had to take those responses at face value. Thirdly, the small sample size of the treatment report study limited the analyses that could be conducted, as there were not enough data points to utilise relevant information in the reoffending database, such as offence seriousness or criminal history. As such, it was not possible to examine whether factors such as the SCCLS or being in current treatment were independent predictors of section 32 dismissal. Future research could improve upon this research by utilising a larger dataset.

Conclusions and recommendations

As mentioned previously, the Statewide Community Court Liaison Service increases the likelihood of diversion and is being slowly expanded but is still not available in every NSW Local Court. This needs to be addressed. Another key point to emerge from this study is that courts clearly want more feedback on the outcome of their referral decisions, particularly when treatment staff conclude that the person referred does not have a mental illness, and the person referred is sent back to the court. Treatment staff (and defence counsel) may be reluctant to report non-compliance with treatment obligations if they believe the person in question will be imprisoned or otherwise sanctioned as a result. At the very least, however, it should be possible to develop a system that provides regular statistical feedback to courts on the number applying for diversion under the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020 (NSW), the proportion of applications granted or made and the outcomes of diversion (e.g. treatment completion, reoffending). The free-form responses to the magistrate survey also suggest that magistrates would appreciate knowing more from treatment staff on the kinds of treatment available, the evidence supporting their efficacy and the way staff handle situations where the client fails to comply with their treatment obligations. The research reported here focuses on what happens in the courtroom in cases where a defendant is being considered for diversion on mental health grounds. Future research should focus on what happens outside the courtroom after referral takes place.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Christel Macdonald has declared no conflicts of interest.

Don Weatherburn has declared no conflicts of interest.

Julia Lappin has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HC210769 and HC210030), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all magistrates completing the online survey. For the treatment report study, informed consent was not obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Note that although the treatment report study was an analysis of deidentified health and court records, it was not an in vivo experiment with human participants. It was also not feasible to obtain consent. The whereabouts of individuals convicted is not generally known, and the numbers involved were too large to track down. We obtained a waiver of consent by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HC210030).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The SCCLS is a service by which a mental health nurse or psychiatrist provides psychiatric assessment and triage of individuals at court or in police holding cells, and prepares a report that is given to magistrates, defence lawyers and police prosecutors. These clinicians then assist magistrates, lawyers and other court staff with the diversion of eligible individuals by referring them to appropriate mental health services in the community (Greenberg & Nielsen, Citation2002).

2 There are too few cases to separately analyse the results for Childrens and Local Courts; however, it is important to note that different sentencing principles apply to matters dealt with in the Children’s Court. They include the principle that the least restrictive form of sanction is to be applied against a child who is alleged to have committed an offence and that criminal proceedings are not to be instituted against a child if there is an alternative and appropriate means of dealing with the matter (NSW Young Offenders Act ss 7a and 7c).

3 The Downing Centre Court Complex was selected because it would have been prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to examine treatment reports in the 155 Local Courts scattered across NSW. The Downing Centre Complex is the largest court complex in NSW and is conveniently located in the Sydney CBD.

4 The linkage of some cases failed for a variety of reasons including the fact that (a) the case was finalised in a court other than the Downing Centre Local Court, (b) a case of mental health dismissal could not be found in the court record, (c) the defendant was already in supported care, prison or a hospital and (d) multiple reports were used by the court.

References

- Al-Rousan, T., Rubenstein, L., Sieleni, B., Deol, H., & Wallace, R. B. (2017). Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: A prevalence study in a state prison system. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4257-0

- Albalawi, O., Chowdhury, N. Z., Wand, H., Allnutt, S., Greenberg, D., Adily, A., Kariminia, A., Schofield, P., Sara, G., Hanson, S., O'Driscoll, C., & Butler, T. (2019). Court diversion for those with psychosis and its impact on re-offending rates: Results from a longitudinal data-linkage study. BJPsych Open, 5(1), e9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.71

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2019). The Health of Australia’s Prisoners, 2018, Supplementary Tables—Mental health - States & territories. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/population-groups/prisoners/data

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Mental health services in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services/interactive-data

- Baksheev, G. N., Thomas, S. D. M., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2010). Psychiatric disorders and unmet needs in Australian police cells. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(11), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048674.2010.503650

- Bebbington, P., Jakobowitz, S., McKenzie, N., Killaspy, H., Iveson, R., Duffield, G., & Kerr, M. (2017). Assessing needs for psychiatric treatment in prisoners: 1. Prevalence of disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1311-7

- Buchanan, D. (2020). A practical guide to mental health issues in the NSW Local Court Part 1 Sections 32 and 33 Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW). Legal Aid. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/41899/A-Practical-Guide-to-MH-Issues-in-the-NSWLC-Part-1-ss-32-33-MHFPA.pdf

- Butler, T., Indig, D., Allnutt, S., & Mamoon, H. (2011). Co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder among Australian prisoners. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00216.x

- DPP v Albon. (2000). NSWSC 896. https://jade.io/article/182562

- DPP v El Mawas. (2006). NSWCA 154. http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/nsw/NSWCA/2006/154.html

- DPP v Saunders. (2017). NSWSC 760. https://jade.io/article/533868

- Fernandez, L. (2007). Section 32 Mental Health (Criminal Procedure) Act – Summary of principles. Legal Aid NSW. https://www.legalaid.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/6099/Section-32-Summary-of-Principles-.pdf

- Forsythe, L., & Gaffney, A. (2012). Mental disorder prevalence at the gateway to the criminal justice system (Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice, Issue 438). Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Gotsis, T., & Donnelly, H. (2008). Diverting mentally disordered offenders in the NSW Local Court. Judicial Commission of New South Wales.

- Greenberg, D., & Nielsen, B. (2002). Court diversion in NSW for people with mental health problems and disorders. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin, 13(7), 158–160. https://doi.org/10.1071/nb02064

- Jones, C., & Crawford, S. (2007). The psychosocial needs of NSW court defendants (Crime and Justice Bulletin, Issue 108). NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

- Judicial Commission of New South Wales. (2023). Inquiries under the Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020. In Local Court Bench Book. https://www.judcom.nsw.gov.au/publications/benchbks/local/mental_health_and_cognitive_impairment_forensic_provisions.html

- Macdonald, C., & Weatherburn, D. (2023). What matters to magistrates when considering diversion into mental health treatment? Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2023.2243321

- Macdonald, C., Weatherburn, D., Butler, T., Albalawi, O., Greenberg, D., & Farrell, M. (2023). Who gets diverted into treatment? A study of defendants with psychosis. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2023.2175070

- New South Wales Law Reform Commission. (2012). People with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system: Diversion. New South Wales Law Reform Commission.

- NSW Government. (2022, June 21). NSW Budget 2022-23. $2 Billion Investment in the State’s Justice System. https://www.budget.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-06/20220620_01_SPEAKMAN-2-billion-investment-in-states-justice-system.pdf

- Ogloff, J. R. P., Talevski, D., Lemphers, A., Wood, M., & Simmons, M. (2015). Co-occurring mental illness, substance use disorders, and antisocial personality disorder among clients of forensic mental health services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000088

- Perry v Forbes. (1993). NSWSC, unreported.

- Sanders, J. (2021). What’s new with section 32? Diversion under the new Mental Health and Cognitive Impairment Forensic Provisions Act 2020. May 2021 update. https://criminalcpd.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Whats-new-with-section-32_-May-2021-edition.pdf

- Soon, Y.-L., Rae, N., Korobanova, D., Smith, C., Gaskin, C., Dixon, C., Greenberg, D., & Dean, K. (2018). Mentally ill offenders eligible for diversion at local court in New South Wales (NSW), Australia: factors associated with initially successful diversion. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(5), 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1508487

- Tyler, N., Miles, H. L., Karadag, B., & Rogers, G. (2019). An updated picture of the mental health needs of male and female prisoners in the UK: prevalence, comorbidity, and gender differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(9), 1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01690-1

- Vanny, K. A., Levy, M. H., Greenberg, D. M., & Hayes, S. C. (2009). Mental illness and intellectual disability in Magistrates Courts in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 53(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01148.x