Abstract

In this paper, we outline a new way of thinking about the purpose and practice of mediation. We propose that mentalizing-inspired mediation can be an effective tool for understanding the interpersonal conflict behaviours that often perpetuate disputes, inhibit their resolution, and promote the likelihood of new disputes emerging in the future. By adapting the theory of mentalizing and the mentalization-based treatment (MBT) model, we introduce a scientifically grounded approach, which we call MBT-M, to inform and elevate mediation education and practice. MBT-M offers a neat and modern reframe on the purpose and practice of mediation as a process that can assist parties to identify, and recover from, impaired mentalizing in order to understand, or ‘mentalize’, the conflict behaviours that are preventing the meaningful resolution of their dispute. Future work will outline how the MBT-M model can offer a robust, evidence-based platform from which to guide mediation interventions, research and scholarship.

Mediation is a unique dispute resolution process: a process that has been widely utilised over time and across cultures (Folberg, Citation1983; Lederach, Citation1996). Introducing a mediator to facilitate a conversation between disputing parties appears to alter the course of the dispute and the relationship between parties, which will likely have some bearing on the outcome (Wall et al., Citation2001). In this paper, we present a contemporary explanation for why the resolution of disputes, both legal and non-legal, may require the assistance of a mediator in the first place and, in turn, how this explanation might inform the purpose and practice of mediation processes. By adapting the theory of mentalizing and the mentalization-based treatment (MBT) model, we introduce a current and scientifically-grounded approach, which we call MBT-M, to inform and elevate mediation education and practice.

At the outset, it is important to acknowledge that we are not the first to recognise that an understanding of mentalizing and the MBT model may be valuable tools for any practitioner, educator or scholar concerned with interpersonal processes. Interpersonal processes exist at the core of many disciplines, and the principles of mentalizing and the MBT model have been used in fields as diverse as the arts (Head & Orme, Citation2023), the modern world (Campbell & Allison, Citation2022; Locati et al., Citation2023), child rearing (Lavender et al., Citation2022), pharmacy (Schackmann et al., Citation2023) and of particular relevance to this paper, the legal profession (Drozek et al., Citation2021; Howieson, Citation2023).

In our experience as mediation educators, mediation practitioners are seldom taught, and thus rarely use, a theoretically-driven, evidence-based lens to describe or interpret party behaviour, instead relying on assumptions, intuition and practice-informed knowledge. We see this as problematic. Others have similarly remarked on the need for coherent conceptual models that can assist mediation practitioners, researchers and educators in their work, and have opined that a shift from idiosyncratic or ideological theories of practice to evidence-based theories could have benefits for the field (Coleman, Citation2011; Coleman et al., Citation2015; Kressel, Citation2013; Kressel & Pruitt, Citation1985; Wall & Dunne, Citation2012).

To address this gap in knowledge and practice, we propose following the lead of other evidence-based and interpersonally oriented professions, specifically the disciplines of psychology and psychiatry. These disciplines, through organised scientific research, have developed neuro-bio-psycho-social frameworks to help professionals make sense of complex behaviours and interpersonal dynamics, such as those exhibited when engaging with an unresolved dispute (Braun & Braun, Citation2021; Yamada et al., Citation2000). Based on these frameworks, treatment or intervention models have been developed that enable practitioners to make informed diagnostic and treatment decisions, and permit standardised and skilful practice (Allen et al., Citation2008).

Mentalizing is not the first theory that mediation scholars and practitioners have examined to better understand the internal processes that influence the emotional states of parties in a mediation process. For example, the science and theory of dysregulation have been used to provide insight as to how the impaired internal processes of parties may act as a barrier to productive interactions (Conway & Stannard, Citation2016). Our contention is that the theory of mentalizing retains similar principles to other psychologically informed theories that have been applied to mediation, but is particularly useful as, when applied via MBT, which is derived from mentalizing theory, it can assist practitioners to not only understand complex behaviours and interpersonal dynamics, but also modify them through informed interventions. In further support of the use of mentalizing theory and MBT, there is a compelling argument that impaired mentalizing is fundamentally implicated in emotion dysregulation (Schwarzer et al., Citation2021). Thus, we consider MBT to be an intervention model that, if appropriately adapted, could be particularly helpful for the mediation field (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016).

We begin this paper by outlining the psychological theory of mentalizing, which has traditionally been employed to understand and treat personality disorders in a range of contexts (Fonagy & Allison, Citation2014). Personality disorders are usually characterised by impaired mentalizing, expressed as non-organic temporary or global impairments in social cognition, emotional dysregulation and frequent interpersonal conflict (National Health & Medical Research Council, NHMRC, Citation2013). The experience of impaired mentalizing, however, is not reserved only for people with psychopathologies. Below, we elaborate the argument that, for all people, when mired in the unpleasant experience of an unresolved dispute, mentalizing is often impaired, leading to conflict behaviours that mirror a number of the symptomatic behaviours associated with personality disorders, albeit temporarily. We suggest that it is these behaviours that perpetuate disputes, inhibit their meaningful and sustainable resolution, and promote the likelihood of new disputes emerging in the future. As such, we believe that an understanding of mentalizing, and how its impairment can influence mental processes and subsequent behaviour, is fundamental to the understanding of ongoing disputes. Further, we believe that an understanding of the importance of mentalizing directly informs the purpose and practice of mediation – namely, to assist parties to recover from impaired mentalizing to understand, or ‘mentalize’, the conflict behaviours that are preventing the meaningful resolution of their dispute.

In the dispute resolution literature, to characterise the utility of a mediation, metrics such as ‘reached settlement, agreement or resolution’, and subjective assessments such as a practitioner’s ‘overall perceptions of success’ have tended to be employed (Saundry et al., Citation2018; Wall & Kressel, Citation2017). These metrics have contributed to the perception that outcomes, particularly settlement, constitute mediation’s ultimate purpose. While we acknowledge the importance of outcomes, here we caution against their use as indicators of success and against the perception that assisting parties to reach settlement, agreement or resolution constitutes mediation’s ultimate purpose. In part, our reasoning looks to one of the most robust findings in the conflict resolution literature, namely that the likelihood of parties accepting and cooperating with agreements or decisions, regardless of their nature, hinges on their perceptions of the process that led to their creation and endorsement (Howieson, Citation2011; Tyler et al., Citation1992). The implication is that the outcome reached might not hold much weight in and of itself if one or more of the parties are unlikely to accept or cooperate with it. As such, when attempting to characterise the utility or success of a mediation, we suggest that it might be more appropriate to look to party’s perceptions of the process.

We propose that MBT-M offers a theory-informed approach to mediation that has been intentionally designed to increase the likelihood that parties will accept and cooperate with any outcomes reached. In summary, MBT-M seeks to achieve this by first facilitating and encouraging meaningful self and other understanding, particularly in relation to any unresolved or otherwise ignored interpersonal conflict that has been generated by impaired mentalizing and the associated conflict behaviours, followed by the creation of what we call mentalized options for resolution and, subsequently, the making of mentalized decisions. Further, as a scientifically derived approach, the MBT-M process lends itself to evaluation and refinement using similar methodologies to high-quality evaluations of MBT (Malda-Castillo et al., Citation2019).

A theoretical framework for understanding conflict behaviours

Our hope here is to illustrate how integrating mentalizing into the mediation field could help to sharpen mediation thought and action, and ground its research in science. MBT is an evidence-based model derived from theory and research in psychology, psychiatry, philosophy and neuroscience, which was developed within a therapeutic context where patients presented with personality disorder diagnoses, primarily borderline personality disorder (BPD) and antisocial disorders (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). The restricted patterns of mental processing that people with these disorders evidence tend to resemble those temporarily encountered by all of us when experiencing heightened emotion, such as is often the case when we are in a dispute with another. In a mediation context, we refer to the behaviours that flow from these restricted patterns of mental processing as conflict behaviours, and see the potential benefits of an understanding of mentalizing theory as follows:

Adapted for mediation, mentalizing theory offers a framework that mediators can use to make sense of complex dynamics of conflict behaviour that perpetuate disputes and prevent resolution.

Adapted for mediation, the MBT-M model can support mediators to make intentional intervention decisions that can help parties to explore, understand and shift these behaviours.

Researchers can use the MBT-M model to make testable predictions about the effect of chosen mediator interventions for specific conflict behaviours and make modifications and updates to the model as new findings emerge.

In this paper, we outline the framework that provides the prerequisite knowledge that underpins further practical and research applications.

An introduction to mentalizing theory

Mentalizing is a primary human capacity. It involves a complex set of mental processes that enable us to interpret our own and others’ behaviour in terms of the internal mental states that might be motivating the behaviour (Fonagy & Target, Citation2006). Mental states can include thoughts, feelings, beliefs, goals, desires and purposes, and reasons can relate to external stimulation (e.g. seeing, hearing), internal signals (e.g. feeling, thinking, imagining) or previous experience (i.e. memory). When we are reflecting on the mental states of ourselves and/or others, we are mentalizing. This active process allows us to appreciate, to varying degrees, that behaviour, both ours and others, is understandable and purposeful. Thus, to facilitate adaptive social communication and navigation of the social world, our minds must constantly generate hypotheses or inferences about mental states (Fonagy et al., Citation2019). Depending on physiological or emotional arousal, our minds undertake this task in several ways, including automatically (when arousal is relaxed), actively (when arousal is optimal) or by bypassing the mentalizing system altogether (when arousal is too low or too high).

The capacity to mentalize varies both between and within individuals. Variability between individuals is thought to be partly attributable to the early attachment environment, where secure attachment relationships help children to find their own mind in the minds of their significant caregivers (Freeman, Citation2016). Disruptions to early attachment relationships, such as trauma or low-quality caregiving, can impair the development of one’s emerging mentalizing capacity (Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). The development of personality disorders, mental health issues or later exposure to trauma can have similar effects on one’s capacity (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019). These disruptions have potentially lifelong implications: specifically, an increased vulnerability to poor mentalizing and the constellation of psychological and social impairments that occur as a consequence of a reduced capacity to make sense of the states that motivate the behaviour of oneself and others (Livesley & Larstone, Citation2018). An understanding that not all people share the same capacity to mentalize is important for practitioners, particularly for those who work with high-risk clients (e.g. borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, trauma history or schizophrenia) where the capacity to mentalize is frequently impaired (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009).

Variability within individuals also emphasises the dynamic nature of people’s capacity to mentalize in response to moment-by-moment experiences and contexts. One may be able to access their ‘full’ mentalizing capacity when they are functioning well, in a familiar context that is free from threat (real or perceived). For example, someone talking with a trusted colleague at a team meeting about the type of work that they do is unlikely to invoke any arousal that would reduce their capacity to mentalize to the best of their ability. However, this same person may have a quite different mentalizing experience in a situation where there is a perceived threat, or when they not functioning well. A common situation that may induce a period of elevated psychosocial distress and impair one’s mentalizing capacity is an interpersonal conflict. For example, this person’s capacity to mentalize might be momentarily diminished if, unexpectedly, another colleague at the meeting accuses them of lying and being unprofessional and demands an apology. In this situation, the perception of threat (i.e. embarrassment, shame, potential employment ramifications) may constrain the ability to make sense of, or mentalize, the situation, perhaps resulting in a sub-optimal outcome (e.g. an argument, refusal to apologise, or accusing the colleague of being the liar).

Automatic (implicit) mentalizing

Much of the time, our level of physiological or emotional arousal is relatively relaxed, and our own and others’ behaviours are relatively predictable. At these times, mentalizing is a largely automatic process (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009). Automatic (or implicit) mentalizing utilises pre-cognitive neural systems that rely on simple, tried-and-tested mental heuristics (shortcuts) to enable perception and action without encumbering attentional resources (Satpute & Lieberman, Citation2006; Schneider & Low, Citation2016). Simply put, for much of our time in the social world, we interact, respond and communicate successfully, guided by fast and instinctive interpretations of our own and others’ mental state motivations. In a mediation, this might look like parties engaging in small talk or casual discussions about topics unrelated to the dispute with each other or other people in the room.

Active (explicit) mentalizing

In other instances, where we, or others, act in unpredictable or unexpected ways, automatic mentalizing may not serve us well. At these times, to best understand our own or another person’s mental state motivations, we focus our attention on the behaviour, and imagine and hypothesise about what mental states might be driving it (Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). Fortunately, experiences that breach the usefulness of heuristics tend to provoke an increase in arousal, which, in turn, signals a need to engage the neuro-circuitry governing the control of our attentional processes and executive functions, including the mentalizing system. Once activated, these brain regions focus attention and gather information, enabling us to form a thoughtful and complex comprehension of observed behaviour and its possible intention (Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). In other words, we can begin to make sense of complex social situations in depth. Taken together, this is referred to as explicit mentalizing (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009).

For example, during an otherwise banal exchange in a mediation, one party offers an unexpected apology for their behaviour. This may engage explicit mentalizing in the other party and the mediator, presenting an opportunity to work through the meaning and intention of this offering. Explicit mentalizing might take the form of focusing attention on external sources of information (such as the body language of the person offering the apology, verbal cues and environmental factors) or internal sources of information (such as beliefs and feelings about the person and their motivations) to make sense of the apology. For instance, as the party was issuing the apology, they might have also been tearful and exhibiting signs of genuine remorse. Engaging with this explicit form of mentalizing can help the party receiving the apology and the mediator, to correct any erroneous assumptions they had formed while either their automatic or pre-mentalizing processes were engaged (Evans et al., Citation2011).

Good mentalizing

When our physiological or emotional arousal is optimal, we can shift between implicit and explicit mentalizing processes, interact meaningfully, and make sense of our own and others’ behaviour in simple and sophisticated ways, as appropriate for the situation and within the parameters of our capacity (Howieson & Priddis, Citation2015). We observe good mentalizing when we can recognise complex possibilities, such as that people might disguise their mental states to mask their true intentions, express their mental states in a tempered manner to meet normative social expectations, or separate the target of behaviour from the origin of feelings (such as when one takes a hard day at work out on a friend or partner). When our mentalizing is good, we can also recognise that mental states evolve and change across time as people learn new information, and that the mental states of others might differ from our own (Allen et al., Citation2008).

In a mediation, this might look like parties taking a stance of inquisitiveness to discover the complex and dynamic intentions, desires and beliefs that might have produced certain behaviours, past or present, and accept new information as legitimate. Or parties might reflect on and forgive misunderstandings, or express an openness to the changeability of people or circumstances (Li & Lu, Citation2017).

Impaired mentalizing

In instances where we encounter behaviour that is substantially outside our expectations, such as an act of spontaneous verbal aggression, or we encounter information that challenges our existing knowledge structures, such as an accusation that we are untrustworthy, the associated experience of threat or vulnerability can elevate arousal above optimal levels. In contrast to instances where piqued arousal is beneficial in recruiting explicit mentalizing processes, in instances where arousal is too high, our ability to engage explicit mentalizing processes is interrupted. This appears to be a consequence of our mind attempting to contain the dysregulation and down-regulate the mental load by only engaging implicit mentalizing processes. This is referred to as impaired mentalizing (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2004; Fonagy et al., Citation2016).

Relegation to impaired mentalizing can influence the way we navigate uncomfortable or overwhelming experiences (Fonagy & Allison, Citation2014). In a mediation, this might look like parties finding it difficult to take an active, curious interest in the mental state motivations of others (perspective taking) and themselves (self-reflection) or being less able to shift from fixed views of reality to consider the complexity of situations. Rather than this being seen as deliberately inflexible behaviour, we can understand it as behaviour emanating from impaired mentalizing. Being less proficient at regulating their emotions, parties might also exhibit emotion-driven behaviour and reasoning (Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). In a mediation, this often involves a retreat to positional bargaining, or responses and behaviours that are reactive, rigid and lacking in consideration of another’s perspective. Further, when mentalizing is impaired, any judgements that parties make about their own motivations are likely to be prone to inaccuracy and self-benefiting cognitive biases (Dunning et al., Citation2018; Luyten, Citation2019; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015).

Pre-mentalizing modes

In moments of impaired mentalizing, if we are unable to regain a means of actively mentalizing the situation, we might find ourselves distanced from our own and others’ mental states and begin to experience a sense of interpersonal isolation. Enveloped in the ensuing feeling of an absence of connection and support, and lacking full control of our emotions, the associated increase in arousal will likely overwhelm our capacity to tolerate emotional dysregulation, and our mind will need to employ a new strategy to curtail the unpleasant experience.

Specifically, our minds are likely to divert resources away from the neuro-circuitry governing the control of our attentional processes and executive functions, including the mentalizing system, and redirect them toward the neuro-circuitry governing reflexive responses to threat, including the limbic system (amygdala, hippocampus), posterior cortex (occipital, parietal and temporal cortices) and the brainstem (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009). Once activated, these brain regions work to rapidly generate attacking or withdrawing behaviours that are intended to protect the physical, psychological or emotional self and share commonalities with fight, flight, fawn and freeze taxonomies (Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). Importantly, the non-mentalizing, or pre-mentalizing, processes that underpin these behaviours do not permit the formation of a thoughtful and complex comprehension of observed behaviour and its possible motivation. In other words, we are unable to make sense of social behaviours, dynamics or situations with any real depth and, in turn, are only able to ready un-mentalized responses. We call these un-mentalized responses conflict behaviours.

In a mediation, these might look like interactions that seek to frighten, undermine, frustrate, distress or coerce the other (Bleiberg, Citation2013). By conceptualising these predictable reflexive behaviours as un-mentalized conflict behaviours, we can look to the mentalizing literature for insights into the type of mental processing that motivates them.

Mentalizing theory posits that when our minds are processing information via pre-mentalizing processes, it tends to employ one (or more) of the three primary modes of social cognition that developmentally pre-date full mentalizing. These modes are referred to as teleological, psychic equivalent and pretend or pseudo-mentalizing, and each endows us with unsophisticated, but crucial, strategies for interpreting behaviour from very early in life, before we have fully developed the mature cognitive functions required for ‘good’ mentalizing (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019; Gergely & Csibra, Citation2003). These strategies include rapid assessments of behaviour and situations, and the rapid readying of responses, with the goal of stabilising or containing our sense of self and temporarily downregulating our emotional arousal (Fonagy & Allison, Citation2014). We outline these three modes below.

Mode 1: teleological/action mode

The teleological or action mode is an ‘I’ll believe it when I see it’ or ‘I/they/we need to do something’ type of thinking. When the mind is in this mode, in order to experience certain mental states, we must first have concrete, tangible indicators in the physical world (Fonagy & Target, Citation2006). By narrowing subjectivity to the mental states that have tangible indicators, the complexity and opaqueness of an emotionally arousing situation or dynamic is reduced, which in turn temporarily downregulates the emotional arousal (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). For example, if a colleague failed to acknowledge that we stayed late at work to help them meet a tight deadline, we might begin to feel angry and unappreciated. The associated increase in emotional arousal might shift our mind into a pre-mentalizing state. In this state, we might not be able to generate the feeling that our actions were appreciated (mental state) via our own mental processing. Rather, we might first need to observe a tangible indicator of appreciation from our colleague, such as a public ‘thank you’ or a gift.

It is worth noting that emotional responses to behaviour and the desire to see particular outcomes or changes in behaviour are natural and often entirely reasonable and appropriate. Where these can become problematic, however, is when our arousal is extreme enough that our mind is mired in an inability to experience certain mental states in the absence of these tangible indicators. Where this is the case, we say the person is ‘stuck’ in teleological or action mode.

In a mediation context, tangible indicators often include demands or evidence connected to money, property, time allocations, contracts, and so on. These foci become important for the ‘stuck’ party who is unable to access their explicit mentalizing. For example, if one party feels significant distrust for the other, they might demand that a contract be signed (perceived as a tangible indicator of commitment) before they are willing to engage further. While in this pre-mentalizing state, in the absence of the signed contract, nothing the other party says or offers will engender a sense of their commitment in the mind of the affected party. Importantly, there is also no guarantee that the signing of the contract will engender this mental state either.

In many instances, the tangible indicator can act as a ‘container’ for a party, holding all the un-mentalized thoughts, beliefs, hurt, rage, upset, anxiety or sense of loss associated with a particular situation. The party can then act upon or demand action in relation to this container with the hope of regulating the associated emotions (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). For example, in the context of a family dispute, Party A might be using the house as a container for several powerful and distressing mental states associated with Party B (e.g. the belief that Party B does not care about them or their children). Rather than mentalizing these mental states, or sitting with the uncomfortableness of ambiguity, Party A might demand that Party B agree that they can stay in the house with the children, hoping to use Party B’s response as ‘clear evidence’ of a less distressing mental state (i.e. ‘He does actually care about us’). However, if Party B does agree to the request, Party A may face a predicament if the action does not resolve the distressing mental states, and the container (the house) is no longer available. Rather than accepting that Party B does care, Party A’s mind will likely seek a new container into which to propel the un-mentalized affect. As such, Party A might then shift the focus of the conflict to a new dispute, such as the best school for the children (the new container). Party A might now argue that Party B does not care about them unless their children are enrolled in a new school.

Others are likely to experience teleologically motivated conflict behaviours as frustrating, superficial or nonsensical. However, the only concern of the mind of the person in action mode is to seek immediate psychological, emotional or physical safety, control or containment, potentially at the expense of well-considered and longer lasting options.

Mode 2: psychic equivalence/certainty mode

The psychic equivalence or certainty mode is characterised by the conviction that ‘The way I feel/think/believe it is, is the way it is’. When in this mode, people mistake their subjective mental states (internal reality) for objective, external reality (what actually is), and have limited ability to accept that the external reality could be different from what they are experiencing internally (Flavell, Citation1999). In contrast to action (teleological) mode, certainty (psychic equivalence) mode is characterised by an appreciation that mental states can exist in the absence of tangible indicators (Wellman et al., Citation2000). By reducing subjectivity to only what we think, feel or believe, and then holding these as certainties, our minds can reduce the complexity and opaqueness of a situation or dynamic. This can then promote perceptions of emotional and cognitive containment, which, in turn, can temporarily downregulate emotional arousal (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016).

Using the same example as above, if after having completed the task for a colleague we believe that we have been exploited and begin to feel angry, the increase in emotional arousal might shift our mind into a pre-mentalizing state. In this state, we might hold this belief as fact with conviction, ‘I was exploited’, and become impervious to any mental states or evidence to the contrary. Where this is the case, we say the person is ‘stuck’ in psychic equivalence or certainty mode.

In a mediation, parties might appear to have stopped listening, tuned out, or remain ‘dug in’ on their position or belief. Others might give up trying to get their point across because they are certain that the other party will misunderstand them, ‘I feel misunderstood, therefore I am misunderstood’. Others might remain quiet and uninvolved, with the belief that ‘I already know what will happen, therefore there is no point contributing what I really think’ held as fact.

The conflict behaviours from those stuck in psychic equivalence are likely to be experienced by others in the mediation as stubbornness, selfishness or wilful ignorance. However, as with action mode, the mind of the person in certainty mode is only concerned with seeking immediate psychological, emotional or physical safety, control or containment.

Mode 3: pretend and pseudo-mentalizing modes

The pretend and pseudo-mentalizing modes might be best thought of as ‘just talk’ (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019). In these modes, a person’s mind temporarily downregulates emotional arousal by distancing them from distressing emotions and navigating situations and relationships intellectually. It can be an efficient way for people to reduce the affective friction and stress that a situation is stirring in them. Further, by engaging with others in a manner that does not have any meaningful depth or connection to authentic experience, the person is able to avoid any additional emotional impact that might come from challenges to their understandings of the world (knowledge stability) or sense of self (Luyten et al., Citation2012). In other words, they ‘pretend’ to engage with the world and others.

For example, in a mediation, a party might appear to be participating earnestly in discussions or negotiations only to snap back to a point that they had made much earlier, without any fresh insight, additional complexity or interest in analysis. In this instance, both the mediator, and possibly the other party, might feel a sense of disappointment, frustration or surprise in the face of what may feel like a regression to an earlier point in the process. Alternatively, a party might become distant and withdrawn, nodding along with whatever is being said, or claiming that they do not care about the outcome, and thus not engaging with the proceedings in a genuine way. Understanding that parties in pretend mode may ‘say all the right things’ to manage feelings of discomfort can help mediators to pinpoint the origins of difficulties in the later stages of the mediation process.

Another way of engaging when in this mode can be the use of ‘hyper-mentalizing’, whereby a party can over-analyse or intellectualise a situation or relationship, claim to understand what others think and why, ‘correct’ perceived errors in others’ understanding of their own mental states or describe chains of causation that likely skew or test the limits of reality (Luyten et al., Citation2012). Here, the party is able to maintain knowledge stability and their sense of self by deftly painting any challenging information ‘out of the picture’. This is referred to as pseudo-mentalizing.

Returning to the earlier example of not being acknowledged by a work colleague after staying late at work to help them meet a tight deadline, the feelings of anger and unappreciation may sufficiently increase our emotional arousal to shift our mind into the pre-mentalizing state of pretend or pseudo-mentalizing. In this state, we might disengage from our anger and claim that we do not care that our colleague did not think to acknowledge us because the real reward was being able to assist someone else (pretend). Or we might disengage from our anger and construct an elaborate list of causal mental states that have motivated their behaviour, such as that our colleague is likely stressed, and because of a difficult upbringing, when they are stressed they become petty, and thus might be intentionally snubbing us to get back at us for something that happened in the past, so there is no reason to get upset about their unfortunate behaviour (pseudo-mentalizing).

In a mediation, we might see parties using reasonable, glowing, articulate or reflective language, or seemingly reasonable attempts at engagement and perspective-taking, to paint a picture of themselves, others or a situation in a particular light. Parties in this mode might also use learnt terms such as ‘listening to each other’ or ‘best interests of the child’, but hold only a superficial understanding of the concept or no genuine desire to implement the principle. Because of the deftness, and because pretend mode and pseudo-mentalizing can at times sound like good mentalizing, these modes can be quite difficult to detect. Parties, and the mediator, might experience these modes as an absence of genuine conviction in the speaker, or might have the impression that what the speaker is feeling or experiencing does not match the intensity that the discourse or situation warrants (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). Further, in both pretend and pseudo mode, the speakers’ behaviours can become unconstrained because of the distance they have from their own or the other’s real experiences (Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2016). This might engender boredom, frustration, scepticism or a sense of unease in others and may lead to prolonged or ineffective mediation processes that don’t reach any meaningful outcomes.

Reciprocal impairments in mentalizing

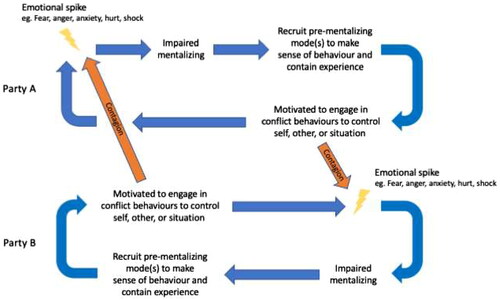

Above, we have outlined good mentalizing, impaired mentalizing and pre-mentalizing processes with respect to an individual’s experience. Mentalizing, however, often takes place in the dynamic, bi-directional context of interpersonal interactions, whereby the mentalizing and resultant behaviour of one can influence the mentalizing and resultant behaviour of another, and vice versa. In a mediation context, we see that it is often a cascade of reciprocal impairments in mentalizing that produces the range of conflict behaviours that restricts the parties’ capacities to engage their explicit mentalizing to generate mentalized options and make mentalized decisions about their futures. , following from Bleiberg (Citation2013), depicts this reciprocal restriction in mentalizing capacities. We see that once one party’s arousal is spiked (Person 1), their actions become motivated by impaired mentalizing, and impaired mentalizing becomes ‘contagious’, spreading to the other party (Person 2). A perpetual loop of increasingly impaired mentalizing can be elicited, and the parties are said to be ‘in conflict’. Parties caught in this loop will likely struggle to successfully resolve their disputes independently, and might require the assistance of a third party, such as a mediator, to help them regain their ability to mentalize explicitly in order to gain an appreciation of the mental states that each is experiencing.

Approaching dispute resolution via a mentalizing-based model (MBT-M)

As mediators, we are invited to facilitate discussions and negotiations between two (or more) parties who have not been able to successfully resolve their disputes independently. As outlined above, for most parties, the experience of being mired in an unresolved dispute leads to elevated physiological and emotional arousal that exceeds tolerable limits and results in impaired mentalizing (Howieson & Priddis, Citation2012). In this state, reciprocal impairments to mentalizing are likely to perpetuate any misunderstandings and disagreements, and expressions of associated conflict behaviours are likely to further exacerbate the situation and entrench the sense of being ‘in conflict’ (Howieson & Priddis, Citation2015). Simultaneously, good mentalizing, which we believe is necessary for addressing any misunderstandings and disagreements, and motivating cooperative behaviour, is unlikely to be possible. Thus, we posit that a major reason people require the assistance of a mediator to resolve their disputes is that they have been unable to mentalize the portion of the affect that has been stirred by the underlying conflict that frequently accompanies a dispute.

With disputes framed in this theoretically driven, evidence-based way, the purpose and practice of mediation can be articulated with renewed focus and can be approached in a manner that does not rely upon assumptions, intuition or purely practice-driven knowledge. Namely, the purpose of mediation becomes the creation of a process and environment where parties will be able to engage in good mentalizing and, in this mind-state, self-determine a range of mentalized options and decisions regarding their dispute. Thus, the practice of mediation becomes: (a) developing an understanding of the complex dynamics of conflict behaviour that sit underneath the dispute, (b) providing targeted interventions that assist parties to ameliorate the chronic patterns of arousal that are preventing good mentalizing, (c) facilitating parties to understand, or ‘mentalize’, the conflict behaviours that are preventing the meaningful resolution of their dispute, and (d) facilitating cooperative mental-state-focused negotiations on the path toward making mentalized decisions.

Above, we have outlined how mentalizing theory offers a framework that mediators can use to generate an understanding of the neuro-psychological processes that occur when we are in a state of heightened physiological or emotional arousal, such as when we find ourselves ‘in conflict’ with another. It can also assist mediators to make sense of the complex dynamics of conflict behaviour, driven by impaired mentalizing, that often perpetuate both legal and non-legal disputes, inhibit their resolution, and increase the likelihood of new disputes emerging in the future.

It is our view that, while it might be possible to a resolve dispute where one or more parties are operating in action mode without addressing the un-mentalized mental states of the affected party(s), doing so is unlikely to improve the parties’ relatedness, or prevent future discontent or relationship breakdown, as parties will likely revert to seeking new tangible indicators in the hope of mitigating their heightened affect. Similarly, while it might be possible to resolve a dispute where one or more parties are operating in certainty mode without addressing the un-mentalized mental states of the affected party(s), any agreements are unlikely to prove satisfying or sustainable in the long term, as they are likely to have been based on feelings, beliefs or assumptions that were held at the time as narrow facts. Finally, while it might also be possible to resolve a dispute where one or more parties are operating in a pretend or pseudo-mentalizing mode, any agreements made in this state are unlikely to be experienced as genuine or meaningful by either party and are likely to be superficial and temporary in nature.

In sum, where impaired mentalizing blocks the parties’ ability to integrate new information regarding one another’s motivations and behaviours, a vacuum is created whereby any decisions that the parties make are likely to be devoid of any real understanding and appreciation of the dynamics of the dispute. As such, we suggest that mediators work to slow these interactions, create emotional safety and assist parties to engage explicit mentalizing to seek clearer understandings of the full complexity of the genuine internal experience that is aroused by the conflict and dispute. Once explicit mentalizing has returned, mutually acceptable solutions and adaptations will likely emerge, as each party will have been able to gain new perspectives and understandings about what the blocks to resolution might be and why the dispute has continued. Specific interventions to facilitate these goals will be addressed in future work.

Conclusion

Mediation can offer a rare opportunity for people to come together, give voice to their hopes and concerns in a neutral forum, reach new understandings about a dispute and the conflict underlying it, and make wise (mentalized) decisions as to how best to resolve the dispute, while holding in mind the experience and perspective of the other. Our hope is that the mediation field might look deeper into the process and purpose of mediation and see it as the multidimensional tool that it is – namely, a tool that can assist parties to engage in a process that will yield an understanding of the interpersonal conflict behaviours that often perpetuate both legal and non-legal disputes, inhibit their resolution and promote the likelihood of new disputes emerging in the future, and provide a means for parties to resolve their disputes and grievances in ways that hold each other in mind and are genuine, meaningful and durable in the long term.

In this paper, we have offered a current and scientifically-grounded conceptualisation of the way that interpersonal conflict can interfere with effective dispute resolution in mediation. We have suggested that mentalizing processes are at the heart of navigating conflict, regardless of whether or not mediators identify these processes and work with them intentionally. We have applied mentalizing theory to mediation and offered an evidence-based approach to practice that mediators can use to make sense of unhelpful party behaviours, which are often driven by impaired mentalizing.

To ensure that we uphold mediation as the important and multidimensional conflict and dispute resolution tool that it is, we propose that the mediation field could benefit from a ‘good practice’ revolution. We see MBT-M as a part of that revolution. Further, we see that the re-conceptualisation of the purpose of mediation to one of creating a process and environment where the mentalizing of interpersonal conflict can take place could release the pressure valve of the drive toward settlement that presently exists in the mediation system, and could simultaneously inform and elevate mediation education and practice.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Jill A. Howieson has declared no conflicts of interest.

Vincent O. Mancini has declared no conflicts of interest.

Matt Ruggiero has declared no conflicts of interest.

Darren Moroney has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Allen, J. G., Fonagy, P., Bateman, A. W. (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice. American Psychiatric Publishing. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=upyvBAAAQBAJ

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2004). Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780198527664.001.0001

- Bateman, A., Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=WeJOCwAAQBAJ

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=DB2VDwAAQBAJ

- Bleiberg, E. (2013). Mentalizing-Based Treatment with adolescents and families. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 22(2), 295–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.01.001

- Braun, W. V., & Braun, A. N. (2021). A biopsychosocial model – the new approach to dispute resolution and conflict analysis for mediators. Dispute Resolution Review, 1(1), 35–53. https://drr.scholasticahq.com/article/29861-a-biopsychosocial-model-the-new-approach-to-dispute-resolution-and-conflict-analysis-for-mediators

- Campbell, C., & Allison, E. (2022). Mentalizing the modern world. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 36(3), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2022.2089906

- Coleman, P. (2011). The five percent: Finding solutions to seemingly impossible conflicts. PublicAffairs. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=PRk4DgAAQBAJ

- Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K. G., Mazzaro, K., Gozzi, C., El Zokm, N., & Kressel, K. (2015). Putting the peaces together: A situated model of mediation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 26(2), 145–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-02-2014-0012

- Conway, H., & Stannard, J. (2016). The emotional dynamics of law and legal discourse. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Drozek, R. P., Bateman, A. W., Henry, J. T., Connery, H. S., Smith, G. W., & Tester, R. D. (2021). Single-session mentalization-based treatment group for law enforcement officers. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 71(3), 441–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2021.1922083

- Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2018). Reflections on self-reflection: Contemplating flawed self-judgments in the clinic, classroom, and office cubicle. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 13(2), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616688975

- Evans, S., Fleming, S. M., Dolan, R. J., & Averbeck, B. B. (2011). Effects of emotional preferences on value-based decision-making are mediated by mentalizing and not reward networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(9), 2197–2210. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2010.21584

- Flavell, J. H. (1999). Cognitive development: Children’s knowledge about the mind. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.21

- Folberg, J. (1983). A mediation overview: History and dimensions of practice. Mediation Quarterly, 1983(1), 3–13. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/cfltrq1983&i=5 https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.39019830103

- Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 51(3), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036505

- Fonagy, P., & Luyten, P. (2009). A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 21(4), 1355–1381. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579409990198

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Allison, E., & Campbell, C. (2019). Mentalizing, epistemic trust and the phenomenology of psychotherapy. Psychopathology, 52(2), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501526

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Moulton-Perkins, A., Lee, Y. W., Warren, F., Howard, S., Ghinai, R., Fearon, P., & Lowyck, B. (2016). Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire. PLOS One, 11(7), e0158678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158678

- Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2006). The mentalization-focused approach to self pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(6), 544–576. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2006.20.6.544

- Freeman, C. (2016). What is mentalizing? An overview. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 32(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12220

- Gergely, G., & Csibra, G. (2003). Teleological reasoning in infancy: The naive theory of rational action. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(7), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00128-1

- Head, J. H., & Orme, W. H. (2023). Applying principles of mentalizing based therapy to music therapy methods. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 83, 102017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2023.102017

- Howieson, J. (2011). The professional culture of Australian family lawyers: Pathways to constructive change. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 25(1), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebq017

- Howieson, J., & Priddis, L. (2012). Mentalising in mediation: Towards an understanding of the’mediation shift. Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal, 23(52), 2013–2021.

- Howieson, J., & Priddis, L. (2015). A mentalizing-based approach to family mediation: Harnessing our fundamental capacity to resolve conflict and building an evidence-based practice for the field. Family Court Review, 53(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12132

- Howieson, J. A. (2023). A framework for the evidence-based practice of therapeutic jurisprudence: A legal therapeutic alliance. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 89, 101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2023.101906

- Kressel, K. (2013). How do mediators decide what to do: Implicit schemas of practice and mediator decisionmaking. Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution, 28(3), 709–736. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ohjdpr28&i=727

- Kressel, K., & Pruitt, D. G. (1985). Themes in the mediation of social conflict. Journal of Social Issues, 41(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb00862.x

- Lavender, S. R., Waters, C. S., & Hobson, C. W. (2022). The efficacy of group delivered mentalization-based parenting interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(2), 761–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221113392

- Lederach, J. P. (1996). Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures. Syracuse University Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=G_6NcdYs1ZoC

- Li, H., & Lu, J. (2017). The neural association between tendency to forgive and spontaneous brain activity in healthy young adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 561. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00561

- Livesley, W. J., & Larstone, R. (2018). Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. Guilford Publications. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=qgs5DwAAQBAJ

- Locati, F., Milesi, A., Conte, F., Campbell, C., Fonagy, P., Ensink, K., & Parolin, L. (2023). Adolescence in lockdown: The protective role of mentalizing and epistemic trust. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 969–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23453

- Luyten, P. (2019). Assessment of mentalization. In A. W. Bateman & P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=DB2VDwAAQBAJ

- Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2015). The neurobiology of mentalizing. Personality Disorders, 6(4), 366–379.

- Luyten, P., Fonagy, P., Lowyck, B., & Vermote, R. (2012). Assessment of mentalization. In Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (pp. 43–65). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Malda-Castillo, J., Browne, C., & Perez-Algorta, G. (2019). Mentalization-based treatment and its evidence-base status: A systematic literature review. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 92(4), 465–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12195

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). (2013). Clinical practice guideline for the management of borderline personality disorder. National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Satpute, A. B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2006). Integrating automatic and controlled processes into neurocognitive models of social cognition. Brain Research, 1079(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.005

- Saundry, R., Bennett, T., & Wibberley, G. (2018). Inside the mediation room - efficiency, voice and equity in workplace mediation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(6), 1157–1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1180314

- Schackmann, L., Copinga, M., Vervloet, M., Crutzen, S., van Loon, E., Sterkenburg, P. S., Taxis, K., & van Dijk, L. (2023). Exploration of the effects of an innovative mentalization-based training on patient-centered communication skills of pharmacy staff: A video-observation study. Patient Education and Counseling, 114, 107803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2023.107803

- Schneider, D., & Low, J. (2016). Efficient versus flexible mentalizing in complex social settings: Exploring signature limits. British Journal of Psychology (London, England: 1953), 107(1), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12165

- Schwarzer, N.-H., Nolte, T., Fonagy, P., & Gingelmaier, S. (2021). Mentalizing and emotion regulation: Evidence from a nonclinical sample. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 30(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2021.1873418

- Tyler, T. R., Lind, E. A., & Zanna, M. P. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 115–191). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60283-X

- Wall, J. A., & Dunne, T. C. (2012). Mediation research: A current review. Negotiation Journal, 28(2), 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2012.00336.x

- Wall, J. A., & Kressel, K. (2017). Mediator thinking in civil cases. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 34(3), 331–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.21185

- Wall, J. A., Stark, J. B., & Standifer, R. L. (2001). Mediation: A current review and theory development. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(3), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002701045003006

- Wellman, H. M., Phillips, A. T., & Rodriguez, T. (2000). Young children’s understanding of perception, desire, and emotion. Child Development, 71(4), 895–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00198

- Yamada, S., Greene, G., Bauman, K., & Maskarinec, G. (2000). A biopsychosocial approach to finding common ground in the clinical encounter. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 75(6), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200006000-00017