Abstract

Forensic risk assessments are used to determine sanctions, identify recidivism risk and inform implementation of risk reduction strategies. The best way to gather reliable data to inform decisions is important and the focus of this mixed-method study. Forty-five experienced professionals performed a risk assessment involving a young person who sexually offended (YPSO). They read a good-quality or a poor-quality interview and collateral information. Under half (42.2%) of participants provided the expected risk ratings. Some participants misidentified elements of good-quality interviewing (e.g. rapport, open questions). Ratings of fairness of the forensic interview were positively associated with increased sense of perceived interview quality. Confidence in risk-assessment decisions tended to be higher in the good-quality than the poor-quality interview group. Practitioners involved in the risk assessment of YPSO should receive effective/robust training in best practice interviewing so they can identify and implement empirically based interviewing techniques for care provision for YPSO.

Youth forensic risk assessments are considered a key component in the prevention of young people’s sexual offence recommission (Hempel et al., Citation2013). The accuracy of information gathered during a forensic interview directly impacts the appropriateness of any risk-assessment strategies put in place (Martschuk et al., Citation2022). Inaccurate predictions can lead to high-risk offenders being released or undertreated (false negatives), or low-risk offenders receiving unnecessarily intense treatment or lengthy detention (false positives; Craig & Beech, Citation2010). While the negative consequences of inaccurate risk assessments are quite evident when a high-risk offender is rated a low risk, negative consequences also result when a low-risk offender is rated as high risk. For example, a low-risk offender might receive unnecessary intensive mental health treatment (Monahan et al., Citation2001), be placed in foster care (English & Pecora, Citation1994) or be detained in the juvenile justice system (Hoge, Citation2002). Many studies demonstrated an iatrogenic effect (inadvertent increase in recidivism) of over-treating low-risk offenders with intensive treatments (Andrews & Bonta, Citation2010; Hanley, Citation2006; Petersilia, Citation2003). Thus, accurate risk assessments that lead to reliable predictions (fewest false positives and negatives) are vital to determine the most appropriate treatment and mitigate the risk of any further offending (Hempel et al., Citation2013).

This paper combines two overarching areas pertinent to the forensic risk assessment of young people who sexually offend (YPSO): (a) forensic interviewing (including procedural justice within the interview); and (b) risk assessment (including structured professional judgement). In this paper, practitioners are professionals involved in the risk assessment of YPSO.

Investigative and forensic interviewing

In the context of risk-assessment interviewing, little research exists to guide practitioners in obtaining the most reliable information possible (Leach & Powell, Citation2020). Advice, however, can be taken from the related field of investigative interviewing, which suggests that, in the context of interviewing sex offenders, obtaining a narrative account of events is critical for maximising accurate and elaborate detail (Read & Powell, Citation2011). To facilitate this, the offender’s perception that they are being treated fairly leads to their willingness to provide case-related detail (Beauregard et al., Citation2010; Griffiths & Rachlew, Citation2018). Best practice elements of all investigative interviews include: (a) building rapport, (b) introducing the topic of concern, (c) obtaining a narrative account of the offence or situation, (d) asking clarification questions, and (e) concluding the interview in a supportive way (Read et al., Citation2009). The types of questions asked in an investigative interview have been shown to impact the reliability and thus usefulness of any information gathered (Lavoie et al., Citation2021; Martschuk et al., Citation2022). A number of studies demonstrated the importance of asking non-leading, open-ended questions (e.g. ‘Tell me everything that happened from beginning to end’, Wright & Powell, Citation2006) to elicit a richer narrative and gain fuller detail in an interview (Hyman Gregory et al., Citation2022; Lavoie et al., Citation2021; Powell & Snow, Citation2007), as opposed to closed-ended questions (e.g. ‘Did you play a computer game?’) that require a simple yes/no response or a selection of two or more choices. Asking appropriate questions is important when interviewing young people and vulnerable witnesses with more limited linguistic and cognitive capabilities (Agnew & Powell, Citation2004). However, follow-up specific questions can be asked to obtain specific information about an event (especially towards the end of an interview) to pick up any missing critical details (Hershkowitz et al., Citation2007; Powell & Guadagno, Citation2008). This approach to information gathering is consistent with advice from other interviewing protocols, such as the Cognitive Interview (CI) developed by Fisher and Geiselman (Citation1992; Köhnken et al., Citation1994), the Standard Interview Method (SIM) developed by the Centre for Investigative Interviewing (Powell & Brubacher, Citation2020) or the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) protocol (Orbach et al., Citation2000).

In the context of forensic interviewing with youth, studies consistently show that best practice techniques are often not adhered to (Benson & Powell, Citation2015; Faller, Citation2014; Lamb, Citation2016; Powell et al., Citation2010). For example, Powell and colleagues reported a lack of compliance with the recommended use of open-ended and non-leading questions (Milne & Powell, Citation2010; Powell et al., Citation2022). The dangers of this are apparent. When practitioners gather unreliable information as a basis for their decision-making, it follows that their subsequent decisions on risk level will also likely be unreliable and may lead to young people being unfairly deprived of their freedom, or to the waste of limited mental health and correctional resources (Harris, Citation2006). Such concerns highlight the importance of examining how the quality of an interview influences risk-assessment decisions. Another important consideration is procedural justice within an interview.

Procedural justice within an interview

Procedural justice relates to individuals’ perceptions of the fairness of their treatment and any related decisions by those in authority (Murphy et al., Citation2014). To foster trust and confidence in authority, those in positions of power should act in ways that individuals perceive as fair (Murphy et al., Citation2014; Tyler & Huo, Citation2002). For instance, prisoners who felt anxious or uncertain about what was occurring in their assessment interview, because they perceived their treatment as not procedurally just or fair, were less likely to disclose information to assist in their risk assessment (Tyler & Huo, Citation2002).

The four key ingredients that underpin procedural justice in interviewing are voice, respectful treatment, trustworthiness and neutrality (Goodman-Delahunty, Citation2010). Such approaches to interviewing have been shown to increase voluntary compliance (Goodman-Delahunty & Martschuk, Citation2020). For example, in suspect interviews, use of rapport and procedural justice were associated with more complete disclosures (Goodman‐Delahunty et al., Citation2014) and led to more voluntary compliance and cooperation with authorities (Langley et al., Citation2021).

Despite the evidence supporting the practice of interviewing in a procedurally fair manner, to our knowledge research that considers the applicability of procedurally just interviewing to the context of YPSO risk assessment has been lacking. Further, prior studies have usually considered interview fairness from the perspective of the citizen (victim, witness or detainee), without consideration of the practitioners’ perspective.

Risk assessment

Risk assessments are typically used to determine sanctions, identify likelihood of repeat offending and inform implementation of appropriate risk reduction strategies in the form of interventions and/or treatments (Hempel et al., Citation2013; Rich, Citation2015). Further, they inform the intensity and targets of those strategies or treatments (Rich, Citation2015). To inform decisions on risk, practitioners should consider data from multiple sources, such as ‘clinical interviews, psychological tests, behavioural observation, medical examinations, and reviews of previous case records and reports’ (Worling & Curwen, Citation2001, p. 1). During an assessment, risk assessors typically use a standardised risk-assessment tool to both reduce dispositional decision-making and aid in the gathering and synthesising of information regarding the youth and offence (Schwalbe et al., Citation2006; Vincent et al., Citation2011).

Most current risk assessments are led by the principles of the Risk–Need–Responsivity (RNR) framework developed in 1980 (formalised in 1990; Andrews et al., Citation1990). As the name suggests, three principles guide the RNR approach to assessment (Bonta & Andrews, Citation2007; Brogan et al., Citation2015). The risk principle asserts that offending can be predicted based on identifying factors known to be associated with offending, and subsequently matching level of treatment to level of risk. That is, high-risk offenders should receive more resources than low-risk offenders. The needs principle asserts that the treatment targets criminogenic needs, which are most strongly associated with offending and amenable to change. Finally, the responsivity principle focuses on tailoring treatment to offenders’ individual needs based on factors that may impact their response to treatment, considering, for example, intellectual functioning, literacy and mental health.

Structured professional judgement

For the risk assessment of YPSO, clinicians currently use a structured professional judgement approach. In a structured professional judgement approach, clinician judgement is informed by the guidelines of an evidence-based, risk-assessment tool (Hart et al., Citation2016) that helps clinicians understand and mitigate the risk of sexual violence (Judge et al., Citation2014). An example of a widely used structured professional judgement tool for the risk assessment of sexually abusive youths is called the Estimate of Risk of Adolescent Sexual Offense Recidivism (ERASOR; Hempel et al., Citation2013; Worling & Curwen, Citation2001). The predictive validity of the ERASOR tool for sexually offending youth was supported by a meta-analysis, which found that the ERASOR outperformed more general assessment tools for the prediction of sexual reoffending (Viljoen et al., Citation2012). Final decisions on risk level, however, are based on practitioner discretion (Skowron, Citation2005).

Practitioner discretionary decision-making is compromised by factors such as time constraints, emotions, cultural differences and lack of adequate information (Proctor, Citation2002). For example, a study within the child protection system found that social workers’ decision-making varied considerably across different offices, leading to the potential unfair allocation of limited resources (Berrick et al., Citation2015). In another study, personal factors such as job role, level of experience, personal perspective and preferences or motivations were linked to social workers’ decision-making (Taylor, Citation2012). With so many individual factors influencing risk decision-making, it is important that practitioners are led by best practice interview guidelines and the use of appropriate structured professional judgement tools, so they can gather the best data upon which to base their risk-level decisions.

Another important factor to consider in risk-assessment interviews is practitioners’ confidence in their risk-assessment decisions for both ‘moral and ethical’ reasons (Murray & Thomson, Citation2010, p. 160). For example, if a practitioner’s confidence is low, it would be unethical for them to stand behind their recommendations. Further, when practitioners are not confident in their risk assessments, decisions are more prone to inaccuracy (Douglas & Ogloff, Citation2003; McNiel et al., Citation1998). Clearly, practitioner confidence is important in risk-assessment decision-making generally, yet to our knowledge no research has considered the specific impact of practitioner confidence in the context of risk assessment of YPSO.

The present study

The identified gaps in the literature warrant further research to determine whether interview quality, and practitioner perspective of interview quality and fairness, impact subsequent decisions and/or confidence in the risk assessment of YPSO. The present study, underpinned by the following four hypotheses, aimed to address this dearth of literature.

It was predicted that interviews considered more procedurally just are associated with increased confidence in subsequent risk-assessment decisions, compared to those considered less procedurally just (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, it was expected that good-quality interviews (GQIs) are perceived as more procedurally just than poor-quality interviews (PQIs; Hypothesis 2). It was assumed that confidence in risk-assessment decision-making is higher in GQIs than in PQIs (Hypothesis 3). Lastly, it was projected that PQIs are more likely to lead to unreliable risk-level decisions than GQIs (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Data collection was conducted between May 2021 and October 2023, as part of a larger, ongoing study which aimed to improve forensic interview skills for risk assessment.

Participants

Thirty-seven women and eight men (Mage = 36.84 years, SD = 10.36, range = 22–61 years) participated in this study. To be eligible, participants had to be mental health clinicians who undertook young people’s risk assessments. Most were psychologists (55.6%, n = 25); others were social workers (20.0%, n = 9), occupational therapists (8.9%, n = 4), mental health nurses (13.3%, n = 6) and one speech pathologist (2.2%, n = 1). The majority held post-graduate qualifications (73.0%, n = 33), while the remainder had achieved an undergraduate degree. Their professional experience ranged from less than 1 to 32 years (M = 9.38, Mdn = 8, SD = 6.89); the number of years in current job role ranged from 1 month to 13 years (M = 2.59 years, Mdn = 2, SD = 2.50). Although only three participants reported previous experience using the ERASOR risk-assessment tool (Worling & Curwen, Citation2001), all reported experience with other forensic risk-assessment tools.

Research design

This study used a between-participants design with interview quality (good vs. poor) as an independent measure, and perception of interview quality, risk level, procedural justice and confidence in their decisions as dependent measures. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups: either the good quality interview (GQI), or the poor-quality interview (PQI) group. They were asked to complete a risk assessment before the semi-structured interview and short survey.

Study materials

Mock case scenarios

Participants read one of four mock risk-assessment interview transcripts (average length 2,386 words) and collateral information (i.e. police files and information from the mother about the young person’s home and school life) that held constant across the case studies. The interview transcripts were between a psychologist and a young person convicted of sexual abuse, using two case scenarios that were similar in terms of the provided information and the risk level. One case involved a male adolescent convicted of sexually abusing his 7-year-old male cousin while supervising him during a weekend afternoon. The other case involved a male adolescent convicted of sexually abusing his neighbours’ two younger girls (7 and 8 years old) while supervising them. Excerpts from the interview scenarios are in online supplementary material.

The scenarios were developed by a forensic psychologist from a forensic youth mental health service, as follows. Initially, the ERASOR was used to create two moderate risk profiles, with a different set of factors for each. Next, case scenarios were written to fit the moderate profiles, to ensure a genuine moderate risk. The interviews drew from questions used by participants in a prior study who undertook a mock risk-assessment interview about an adolescent sexual offence (Leach et al., Citation2022). An objective criterion from the investigative interviewing literature was used to determine which interview questions constitute good and poor quality, where GQIs consist of more open-ended questions, and PQIs of more specific, closed-ended and/or leading question types (Leach et al., Citation2022).

The two different cases were used to counterbalance the gender of the victims, and both cases were designed to have a similar level of detail and number of questions in the GQI and PQI conditions. Interviews did not differ other than in the question types. Finally, both cases were considered as a moderate risk without notable differences between the conditions.

Risk assessment tool

Participants used the ERASOR structured risk-assessment tool, intended for use with boys from 12 to 18 years of age who have committed a sexual offence, to aid their decisions on level of risk of sexual re-offence (Worling & Curwen, Citation2001). During an assessment, evaluators rate a convicted youth’s risk based on their coding of 25 factors of risk that come under five overarching headings empirically shown to correlate with sexual re-offence: (a) sexual interest, attitudes and behaviours; (b) historical sexual assaults; (c) psychological functioning; (d) family/environmental functioning; and (e) treatment. Items are coded as 0 (Unknown); 1 (Not Present); 2 (Possibly/Partially Present); and 3 (Present). Participants determine overall risk as low, moderate or high, based on their scoring of the ERASOR, and their consideration of related collateral information (Worling & Curwen, Citation2001). Several studies showed adequate inter-rater reliability for the ERASOR, with coefficients ranging from .75 to .92 (Hersant, Citation2006; Rajlic & Gretton, Citation2010; Viljoen et al., Citation2009).

Semi-structured interview

Interviews, conducted by the first two authors, consisted of two sections. First, participants were asked demographic questions about their professional background, time in their current profession and role, previously-completed interview training, their gender identification and age. Next, participants were asked questions relating to the risk assessment they completed and the interview transcript. The interview questions are in Appendix A. The present study focused on survey questions in relation to level of risk, confidence in practitioners’ risk assessment on a scale of 1 (not at all confident) to 7 (extremely confident), their rationale for their confidence and overall impression of the interview.

Online questionnaire

The procedural justice scale was developed for the purposes of this study based on the four key elements that underpin procedural justice in interviewing (Goodman-Delahunty, Citation2010). Nine items measured participants’ agreement on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The survey was designed specifically for this study to measure perceptions of the procedural justness (fairness) of the risk-assessment interview (e.g. The interviewer gave the young person the opportunity to provide his story; The interview was fair; The interview obtained sufficient information.). Six items related to perceptions of procedural justice within the interview (e.g. The interview was fair), one of which was negatively worded (The interview tactics violated the rights of the young person). Three items pertained to the interviewer (e.g. The interviewer was respectful to the young person), with one negatively phrased (The interviewer was judgemental). A principal component analysis confirmed that all items loaded on one component, including the three negatively loaded items that were reverse coded for further analyses. Reliability analyses revealed Cronbach’s α = .88, with no items that significantly reduced the reliability. The online questionnaire is presented in Appendix B.

Procedure

Various approaches were used to recruit participants, using snowball sampling. First, existing networks were approached. Email invitations were sent to contacts of the research team and to Australian organisations known to have expertise in the risk assessment of justice-involved youth. Second, email invitations were distributed around professional groups such as the Australian Psychological Society (APS) or the APS College of Forensic Psychologists. Participants were not offered any financial incentive for their participation; however, they were offered a training programme, adapted for clinicians who work with justice-involved youth, created by the Centre for Investigative Interviewing. This evidence-based training programme is designed to enhance forensic interview skill in eliciting accurate and detailed information from young people.

Prior to being interviewed about the case study, participants were asked to complete a risk assessment for an adolescent convicted of committing sexual offences against a minor. Therefore, they reviewed the collateral information and the interview transcripts between an interviewer and the convicted young person. Next, they filled out the ERASOR structured professional judgement tool (Worling & Curwen, Citation2001) scoring dynamic risk factors that are more open to interpretation based on the interview, while static factors were prefilled. Based on this information they indicated the overall risk level, ranging from low to high.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams. Immediately after the interview, participants completed an online survey in relation to procedural justice questions. Interviews lasted on average 17.81 min (SD = 5.27, range = 9.24–38.31 min). These were recorded and professionally transcribed.

Data analysis

A mixed-methods approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data, from which interpretations can be drawn from the strengths of each methodological approach (Creswell, Citation2014), was employed. A mixed-methods approach, as opposed to a qualitative or quantitative approach alone, is a superior means of uncovering unique insights into a phenomenon as it combines both types of data and permits one type of data to compensate for the weaknesses of the other (Kadushin et al., Citation2008).

Participants’ responses to the qualitative interview question about overall impression of the interview quality were analysed using data-driven thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Therefore, the first two co-authors created codes from the interview data to interpret any patterns of meaning relevant to the research question (Clarke et al., Citation2015). Participants’ overall impressions of interview quality were coded as negative, neutral or positive. Coding was based on participants’ comments/remarks in response to the open-ended question ‘What is your overall impression of the interview quality?’. Initial themes developed related to indicators of interview quality.

Next, the qualitative responses were transformed into quantitative codes on perceived interview quality (−1 = negative, 0 = neutral, 1 = positive). provides examples of what were coded as positive, neutral and negative perceptions of interview quality. To assess inter-rater reliability, 20% of the responses were coded independently by the first two authors of the paper. Inter-rater reliability was Krippendorff’s α = .87. Discrepancies were discussed until full agreement was achieved.

Finally, the integrated qualitative and quantitative data (derived from both the interview and survey) were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Data screening indicated that the assumptions for parametric tests were violated. Therefore, nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used for group comparisons and Spearman’s ρ for correlational analyses.

Results

Perceived and manipulated interview quality

Analysis was initially performed to investigate whether participants’ perceptions of the overall quality of their assigned interview (positive, neutral, negative) aligned with their experimental group (good-quality interview, GQI vs. poor-quality interview, PQI, group). This revealed that 60.0% (n = 27) of participants’ perceptions of the interview quality aligned with the experimental group to which they were assigned, and 40.0% (n = 18) of participants misjudged this. More participants in the GQI group (70.9%, n = 17), than in the PQI group (52.0%, n = 11) accurately identified the quality of their assigned interview (see ).

Perceptions of risk assessment interview quality

Perceptions of interview quality were negative (n = 14, 31.1%), neutral (n = 10, 22.2%) or positive (n = 21, 46.7%). Themes that emerged from participant responses include, question type, level of detail, topic change, rapport and consideration of the developmental stage or situation of the interviewee. gives an overview of the identified themes and subthemes that illustrate participant perceptions of interview quality.

Question type

The most prevalent theme identified was the presence of question type (n = 27, 60.0%; see ). Participants identified different question types (i.e. closed, open and leading) as being either present or absent. The most prevalent question type identified was closed-ended questions (n = 12, 26.7%). Participants identified an equal number in the GQI and PQI (n = 6, 13.3%), as illustrated in the following examples: ‘The questions asked, they’re quite direct and sometimes quite closed questions’ (Participant 26, PQI); ‘they’re quite closed questions, . . . I felt that those aspects, there was a lot more opportunity to expand on those and really understand the behaviour and the motivation a bit better’ (Participant 21, GQI).

The second most identified characteristic was the presence of open-ended questions (n = 11, 24.4%), most of which were identified in the GQI group (n = 9), as illustrated in the following quote: ‘I thought that it was good that they started . . . with that open question, and a fairly neutral approach . . . ’ (Participant 21, GQI). Conversely, three participants from the PQI group noted a lack of the use of open-ended questions. Finally, four participants (8.9%) noted the presence of leading questions (3 in GQI, 1 in PQI) – for example, ‘I think that’s a very leading question’ (Participant 8, GQI), while six noted their absence (5 in GQI, 1 in PQI) – for example, ‘There didn’t seem to be any leading questions’ (Participant 7, PQI).

Level of detail

Level of detail (n = 25, 55.6%) refers to participants’ perceptions of whether adequate detail was gleaned from the risk-assessment interview with the young person (see ). It was the most recurring theme across the sample, with 19 participants (42.2%) remarking that more detail was needed. Most of those comments were made by participants in the PQI group (n = 15, 33.3%). The following quote provides an example of this: ‘I would have liked to have tried to get more elaboration out of the person’ (Participant 4, PQI). Some similar comments, however, were made by participants in the GQI group (n = 4). For example, ‘There was one point where I did think more questions could have been asked around a certain area’, indicating that more specific information around the topic would have been necessary (Participant 6, GQI). By contrast, a few participants (4 in the GQI and 2 in the PQI groups) mentioned that they believed adequate detail was obtained (n = 6, 13.3%).

Topic change

A further recurring theme was topic change, which refers to a sudden change from one subject to the next without permitting the young person sufficient time to appropriately respond. One quarter of the participants (n = 11, 24.4%) noted that the interviewer jumped from one question to the next (GQI, n = 5; PQI, n = 6; see ). The following examples illustrate this concept: ‘ . . . but then it just went onto a different subject’ (Participant 6, GQI) and ‘ . . . you took your cousin for a shower, and then immediately there’s a comma . . . I don’t know how old he is. It doesn’t give the young person time to answer those questions. It goes on to another subject . . . ’ (Participant 3, PQI). Some participants suggested it was because the interview was part of a study, as evidenced in the following quote:

So, we’re talking about the phone calls, for instance, and then all of a sudden it was like, ‘Did you have an erection when you were calling them?’ It kind of just jumped a little bit. I know it’s been condensed for this purpose, but it kind of jumped in terms of level of questioning quite quickly for me. (Participant 21, GQI)

Rapport

Rapport was another important theme identified by participants (n = 13, 28.9%). Nine participants (20.0%) identified the presence of rapport between the interviewer and the interviewee, the majority of which were made by participants in the GQI group (n = 8, 17.8%; see ). For example, ‘There’s been rapport built previously’ (Participant 5, GQI). Conversely, three participants noted an absence of rapport in the interviews, one from the GQI and two from the PQI groups. For example, Participant 9 (PQI) remarked, ‘But maybe in a perfect world, things maybe could have been phrased a little bit differently or a bit more rapport built initially to establish a bit more trust . . . ’. One participant stated that they were unable to discern whether rapport was present in the interview (Participant 1, PQI).

Consideration of the developmental stage/situation of the interviewee

Finally, consideration of the developmental stage/situation of the interviewee was also identified as a recurring theme (n = 8, 17.8%). Six participants (13.3%; GQI, n = 3; PQI, n = 3) highlighted that the interviewer was not considerate of the developmental stage of the young person during the assessment interview (see ). The following are examples:

The interviewer asked, ‘Is there any sexual assault in the porn that you watch?’ Then the interviewer asked, ‘Is there anything that’s a bit out there?’ I thought for a young person both those terms are a little bit vague. A young person might not consider, say, like child exploitation material, they might not consider that sexual assault if they have preconceived understanding of sexual assault as being violent and physically coercive. (Participant 27, PQI)

[The interviewer] asked a few questions that were quite blunt and kind of put the person off, which might have influenced things a bit. (Participant 29, GQI)

Perceived procedural justice

Procedural justice items were first explored in relation to each other. Second, in order to address Hypothesis 1, procedural justice items were explored in relation to confidence. An inspection of Spearman’s rho correlations identified significant and strong correlations among the procedural justice items (see ). For example, there was a significant positive correlation between fairness and voice (the interviewer provided the young person opportunity to provide their story), ρ(43) = .71, p < .001, fairness and neutrality, ρ(34) = .74, p = .001, and sufficient information and fairness, ρ(43) = .60, p < .001.

Strong negative correlations were identified between procedural justice items judgemental (negatively worded) and neutrality, ρ(43) = −.56, p < .001, indicating that, as perceptions of the interviewer being judgemental increased, the sense of the interviewer being neutral in their treatment of the young person decreased. Similarly, a negative correlation between dissatisfaction with questions (negatively worded) and voice, ρ(34) = −.546, p < .001, indicated that the more participants considered the interviewer could have phrased questions in a better way, the less they thought the young person was provided with the opportunity to share his story.

Further, the correlation between the procedural justice element fairness and confidence approached significance, ρ(43) = .22, p = .077, showing a small effect (Cohen, Citation1988, pp. 79–81). The correlation between the remaining procedural justice elements and confidence was not significant (see ). This finding provides limited support for the first hypothesis.

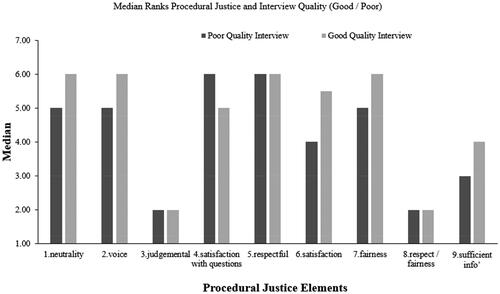

Procedural justice as a function of interview quality

Hypothesis 2 stated that GQIs are perceived as more procedurally just than PQIs. Two separate analyses were used to examine perceptions of procedural justice in relation to both the experimental group (GQI and PQI) and perception of interview quality. First, inspection of median scores indicated that for five of the procedural justice items in the GQI group, median scores were higher than in the PQI group (see ). The following findings were identified: voice with a medium effect size (U = 347, p = .019, r = −.35), and dissatisfaction with questions (negatively worded), also with a large effect size (U = 121, p = .002, r = −.46; see ). According to Cohen (Citation1988) r = .24 is a medium and r = .44 a large effect. These findings show support for the second hypothesis.

Second, to investigate whether perceptions of interview quality were associated with perceptions of procedural justice within interviews, a Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted. For a summary of the findings, see . A statistically significant difference was identified for the fairness item across the three different perceptions of interview quality groups (positive, neutral, negative), χ2(2) = 12.66, p = .002. Pairwise comparisons indicated that interviews considered better quality were perceived more procedurally fair (Mdn = 6) than those considered in a neutral (Mdn = 4.5, p = .011) and negative light (Mdn = 4.5, p = .002).

Further, a statistically significant difference across the three perceptions of interview quality groups was identified for the procedural justice item sufficient information, χ2(2) = 15.22, p = .001. Pairwise comparison indicated that participants who perceived the interview as positive were more likely to agree that the interviewer obtained sufficient information (Mdn = 5) than those who perceived the interview as negative (Mdn = 2, p = .001). These findings show further support for Hypothesis 2.

Confidence in risk assessment

Hypothesis 3 proposed that GQIs increase participant confidence, while PQIs reduce their confidence in decisions on risk level. A Mann–Whitney U Test was conducted to investigate the relationship between experimental group and confidence. No significant difference in confidence levels was identified between the GQI (Mdn = 4, n = 24) and PQI groups (Mdn = 4, n = 21, U = 313.50, z = 1.46, p = .144). According to Cohen (Citation1988) the effect size (r = .2) is small to medium. These findings do not support Hypothesis 3. Similarly, correlational analyses showed that confidence was not associated with their professional experience (number of years working in their profession or current position, all ps > .20).

Risk level

Hypothesis 4 stated that PQI is more likely to lead to unreliable risk-level decisions than GQI. To test this hypothesis, the risk-level variable was coded into (1) correct for assigned moderate risk and (0) incorrect for high or low risk. Chi-square test for independence indicated that 50.0% (n = 12) of participants in the GQI group made an accurate assessment, compared to 33.3% (n = 7) in the PQI group, showing a non-significant association, χ2(1) = 1.28, p = .259, Cramer’s V = .168.

To further explore this hypothesis, a series of chi-square analyses investigated whether PQIs are more likely to lead to either higher or lower perceived risk levels than GQIs. Results showed a tendency to rate risk as higher in the PQI than the GQI group, although the effect was not significant, χ2(1) = 2.51, p = .285, Cramer’s V = .234. In the PQI group, 23.8% of participants assessed risk level as high – nearly triple the amount that assessed the risk as high in the GQI group (8.3%). Conversely, almost as many participants assessed the risk as low in the PQI group (42.9%) as in the GQI group (41.7%).

Further analyses investigated whether participants’ perception of interview quality was associated with decision-making in the risk assessment of YPSO. A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed no differences between decisions on risk level across the three different perceptions of interview quality groups, χ2(2, n = 45) = 0.736, p = .692, rejecting Hypothesis 4.

Correlational analyses showed that risk level and perceptions of interview quality were not associated with practitioners’ experience (number of years working in profession or current position, all ps > .10).

Discussion

Risk assessments of YPSO aim to divert lower risk offenders out of the system, and higher risk offenders to treatment or sanction (Letourneau et al., Citation2013). This study investigated whether the quality and perceived fairness of risk-assessment interviews is associated with participant confidence in their risk assessment of YPSO. The results revealed that participants’ perception of procedural justice in risk-assessment interviews was associated with their perceptions of the quality of the assessment interview. and marginally associated with confidence in their subsequent risk-assessment decisions.

Perceived interview quality

The present study showed that nearly half of the participants (40.0%) inaccurately identified the objective quality of the interviews. It can be argued that participants who do not recognise an objectively good quality interview (GQI) will also have difficulty implementing a GQI in practice, and, subsequently, base risk-level decisions on information gathered from poor-quality interviews (PQIs) with problematic questions.

More detailed analysis of the participants’ responses showed that, while most participants accurately noted the presence, or absence, of some of the key elements of a GQI, such as non-leading or open-ended questions, several participants misidentified them. For example, some participants noted the presence of closed-ended questions in the GQI and identified open-ended questions and rapport in the PQI. It should be noted that closed-ended questions may be used in a GQI towards the end of the interview for clarification (Powell & Guadagno, Citation2008). It stands to reason that participants who misidentified the key elements of good-quality interviewing technique might misuse them in practice. This finding also aligns with research that has concluded that best practice techniques are often not adhered to in forensic interview situations with youth (Benson & Powell, Citation2015; Lamb, Citation2016), and, as such, practitioners may not gather the most accurate data possible to support their risk decisions.

Together these findings indicate a necessity for practitioner training in evidence-based practices, so they are better informed about quality interviewing. As practitioners learn to gather more accurate data, their risk-level decisions will be more knowledge based and likely more accurate. More accurate risk assessments can lead to fewer false-positives and false-negatives, reducing the negative consequences of inaccurate risk assessments, such as increased likelihood of reoffending (Hempel et al., Citation2013).

Perceptions of procedural justice and confidence in decisions

Hypothesis 1 contended that interviews considered more procedurally just increase confidence in subsequent risk-assessment decisions, compared to those considered less procedurally just. This study found that most procedural justice elements were not associated with confidence; however, an increased sense of the interviewee being treated fairly tended to be associated with increased participant confidence in their risk-assessment decisions, showing a small effect. Based on this finding, a fair approach to interviewing may be important for participants’ confidence in their risk assessments. As was noted above, practitioner confidence in risk-assessment decision-making is important. For example, in courtroom contexts, practitioners must be able to stand confidently behind their risk-assessment decisions (Douglas & Ogloff, Citation2003). Further, and in line with Goodman-Delahunty and Martschuk (Citation2020), the findings highlight the importance of the interviewee having a sense of being interviewed in a procedurally just manner for voluntary cooperation. Finally, we found that when participants perceived that questions were phrased poorly, they believed that young people did not get the opportunity to share their story (voice). This finding corresponds with other studies that highlighted a need for further professional development and training around effective questioning (Leach et al., Citation2022) so that young people are afforded the opportunity to share their full story.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that GQIs are perceived as more procedurally just than PQIs. Results showed both manipulated interview quality and perceptions of interview quality to be associated with perceived procedural justice, in particular for voice and satisfaction with questions. This finding reinforces Hypothesis 1, showing additional support for the role of procedural justice in risk-assessment and other interview settings. For example, a meta-analysis revealed that police interactions, adopting procedural justice principles, promoted satisfaction with encounters, along with willing cooperation and compliance (Mazerolle et al., Citation2013).

Hypothesis 3 stated that GQIs increased participant confidence in decisions on risk level, while PQIs reduced confidence in risk-level decisions. While the findings did not support this hypothesis, they showed a trend toward increased confidence in the GQI group. It is possible that with a larger sample size, findings might have been significant (Pallant, Citation2011). Another explanation for the lack of support for this hypothesis may relate to participants having had to base their decisions on an interview transcript between a risk assessor and the young person, a short interview with his mother and a police report. In a real-life context, practitioners would ask questions themselves, contact relevant people and gather as much information as they felt was necessary to feel more assured in their risk-assessment decisions. This is supported by the fact that confidence in risk-level decisions was not related to professional experience.

Lastly, Hypothesis 4 that PQIs are more likely to lead to unreliable risk-level decisions than GQIs was not supported by the study. While this finding conflicts with other research that demonstrates a positive association between GQIs and more reliable decision-making (Lavoie et al., Citation2021), the present findings are likely due to the relatively small sample size. However, a tendency to rate risk as higher in the PQI and lower in the GQI was identified that warrants further investigation with a larger sample. A plausible explanation for the higher risk rating in the PQIs may be that our participants tended to be more cautious when deciding on risk level with information elicited using PQIs.

The present study demonstrated the benefits of improving practitioner interview techniques. Use of GQI technique, as already noted, will result in more accurate data upon which practitioners can base their risk-level decisions. This improvement would lead to practitioners having increased accuracy in their risk-assessment decisions, increased confidence in those risk decisions and, finally, increased sense of the fairness of the interviews upon which they base their risk decisions. In sum, it is advisable that practitioners receive evidence-based training in the use of GQI technique.

Strengths, limitations and suggestions for further research

This study is one of the first to investigate whether practitioners’ perceptions of interview fairness influence risk-assessment outcomes. As outlined previously, most studies on forensic interviewing considered interview fairness as perceived by the interviewee (Murphy et al., Citation2014; Tyler & Huo, Citation2002). The present study, in considering an alternative perspective, builds upon current knowledge and provides a more rounded picture of the factors that influence risk-assessment outcomes.

As with most research, there are limitations. First, this study used a small sample size; thus, the power of the research was low (Pallant, Citation2011), which may have led to the non-significant findings. It is possible that other risk-assessment practitioners may vary in their perceptions of, for example, the procedural justness/fairness of the forensic information gathering process. This, in turn, may affect confidence in risk-assessment decisions and overall outcomes. Hence, results are not generalisable across the broadest spectrum of practitioners involved in the forensic risk assessment of YPSO.

A second limitation pertains to participant lack of experience with the ERASOR tool. It is possible that those more familiar with the ERASOR may be more confident in their risk-assessment decisions than the participants in this study. However, the impact on these findings was expected to be negligible, given that all participants were experienced in youth risk assessment, and in using other risk-assessment tools.

Finally, as participants were personally interviewed, responses may have been impacted by social desirability bias. For example, in response to the question ‘what is your overall impression of the interview?’, responses might not accurately reflect participants’ overall impressions. It is possible that participants did not want to appear negative and, as such, gave a more positive impression of the interview quality than they thought it to be. To minimise this, participants were given the assurance of anonymity, which has been shown to elicit more open and honest responses (Robertson et al., Citation2018).

Despite these shortcomings, the present study adds valuable knowledge around how interview quality impacts the subsequent risk-assessment outcomes of YPSO. These findings could be used for the development of training programmes to address specific skill shortfalls in future.

Implications

Inaccurate risk assessment of YPSO can inadvertently increase recidivism through both the release of high-risk offenders back into the community and the over-treatment of low-risk offenders. Although a need for accurate risk-assessment decisions is evident, research on practitioners’ interviewing skills for the risk assessment of YPSO is scarce. Important opportunities exist for scholars to extend our approach and investigate the impact of interview quality and perceptions of interview quality and fairness on risk-assessment outcomes in larger scale studies. Subsequently, training organisations can draw on such research to develop informed interview-skills training for risk-assessment practitioners.

This study overall may be useful to close the knowledge gap between what the literature identifies as best practice and fair treatment of interviewees, and what eventuates in practice. The specific finding that practitioners’ perception of procedural justice in risk-assessment interviews is associated with their perceptions of interview quality is novel and should inform the development of training programmes. Such training ought to consider: (a) quality interviewing and use of appropriate question types (Powell & Snow, Citation2007); (b) building rapport between interviewer and interviewee (Goodman‐Delahunty et al., Citation2014); and (c) procedural justice in interviewing (Goodman-Delahunty, Citation2010).

Conclusion

The present study revealed that almost half of participants mis-identified the objective quality of their assigned interview and that while most participants correctly identified elements of best practice interviewing technique, some did not. Together, these findings highlight a lack of clarity around what constitutes best practice interviewing (e.g. appropriate use of open-ended and non-leading questioning).

The present results also showcased that a practitioner’s sense of procedural fairness in assessment interviews is important to perception of interview quality and may be important to practitioner confidence in risk decisions. First, in this study, practitioners who perceived that interviewees were treated fairly tended to have increased confidence in their risk-assessment decisions. Second, practitioners strongly associated an increased sense of interview quality with an increased sense of procedural fairness in the interview. Altogether, these findings indicate the importance of a procedurally just approach to interviewing. In conclusion, effective best practice interview-skills training that incorporates a procedurally just approach is necessary for practitioners to provide more reliable risk assessment.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Catherine Clancy has declared no conflicts of interest.

Natalie Martschuk has declared no conflicts of interest.

Chelsea Leach has declared no conflicts of interest.

Martine B. Powell has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee [Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number HREC/21/QCHQ/78485 and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number GU Ref No: 2021/444] and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Griffith University and Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service. Natalie Martschuk is the recipient of a Griffith University Postdoctoral Fellowship. We thank Sonja Brubacher for her comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Agnew, S. E., & Powell, M. B. (2004). The effect of intellectual disability on children’s recall of an event across different question types. Law and Human Behavior, 28(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:lahu.0000029139.38127.61

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct. Routledge.

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854890017001004

- Beauregard, E., Deslauriers-Varin, N., & St-Yves, M. (2010). Interactions between factors related to the decision of sex offenders to confess during police interrogation: A classification-tree approach. Sexual Abuse : a Journal of Research and Treatment, 22(3), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210370707

- Benson, M. S., & Powell, M. B. (2015). Evaluation of a comprehensive interactive training system for investigative interviewers of children. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000052

- Berrick, J. D., Peckover, S., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2015). The formalized framework for decision-making in child protection care orders: A cross-country analysis. Journal of European Social Policy, 25(4), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928715594540

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation, 6(1), 1–22.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brogan, L., Haney-Caron, E., NeMoyer, A., & DeMatteo, D. (2015). Applying the risk-needs-responsivity (RNR) model to juvenile justice. Criminal Justice Review, 40(3), 277–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016814567312

- Craig, L. A., & Beech, A. R. (2010). Towards a guide to best practice in conducting actuarial risk assessments with sex offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(4), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2010.01.007

- Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. Sage Publications.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Douglas, K. S., & Ogloff, J. R. (2003). The impact of confidence on the accuracy of structured professional and actuarial violence risk judgments in a sample of forensic psychiatric patients. Law and Human Behavior, 27(6), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:lahu.0000004887.50905.f7

- English, D. J., & Pecora, P. J. (1994). Risk assessment as a practice method in child protective services. Child Welfare, 73(5), 451–473.

- Faller, K. C. (2014). Forty years of forensic interviewing of children suspected of sexual abuse, 1974–2014: Historical benchmarks. Social Sciences, 4(1), 34–65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010034

- Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory-enhancing techniques for investigative interviewing: The cognitive interview. Charles C Thomas, Publisher.

- Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2010). Four ingredients: New recipes for procedural justice in Australian policing. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 4(4), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paq041

- Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Martschuk, N. (2020). Securing reliable information in investigative interviews: Coercive and noncoercive strategies preceding turning points. Police Practice and Research, 21(2), 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2018.1531752

- Goodman‐Delahunty, J., Martschuk, N., & Dhami, M. K. (2014). Interviewing high value detainees: Securing cooperation and disclosures. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(6), 883–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3087

- Griffiths, A., & Rachlew, A. (2018). From interrogation to investigative interviewing: The application of psychology. In A. Griffiths & R. Milne (Eds.), The psychology of criminal investigation: From theory to practice (pp. 154–178). Routledge.

- Hanley, D. (2006). Appropriate services: Examining the case classification principle. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 42(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v42n04_01

- Hart, S. D., Douglas, K. S., & Guy, L. S. (2016). The structured professional judgement approach to violence risk assessment: Origins, nature, and advances. In D. P. Boer, A. R. Beech, T. Ward, L. A. Craig, M. Rettenberger, L. E. Marshall, & W. L. Marshall (Eds.), The Wiley handbook on the theories, assessment and treatment of sexual offending (Vol. 2, pp. 643–666). Wiley.

- Harris, P. (2006). What community supervision officers need to know about actuarial risk assessment and clinical judgment. Federal Probation, 70(2), 8–14.

- Hempel, I., Buck, N., Cima, M., & Van Marle, H. (2013). Review of risk assessment instruments for juvenile sex offenders: What is next? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X11428315

- Hersant, J. L. (2006). Risk assessment of juvenile sex offender reoffense. Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

- Hershkowitz, I., Fisher, S., Lamb, M. E., & Horowitz, D. (2007). Improving credibility assessment in child sexual abuse allegations: The role of the NICHD investigative interview protocol. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(2), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.005

- Hoge, R. D. (2002). Standardized instruments for assessing risk and need in youthful offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 29(4), 380–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854802029004003

- Hyman Gregory, A., Wolfs, A., & Schreiber Compo, N. (2022). Witness/victim interviewing: a survey of real-world investigators’ training and practices. Psychology, Crime & Law, 29(9), 957–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2022.2043312

- Judge, J., Quayle, E., O'Rourke, S., Russell, K., & Darjee, R. (2014). Referrers’ views of structured professional judgement risk assessment of sexual offenders: A qualitative study. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 20(1), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2013.767948

- Kadushin, C., Hecht, S., Sasson, T., & Saxe, L. (2008). Triangulation and mixed methods designs: Practicing what we preach in the evaluation of an Israel experience educational program. Field Methods, 20(1), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X07307426

- Köhnken, G., Thürer, C., & Zoberbier, D. (1994). The cognitive interview: Are the interviewers’ memories enhanced, too? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350080103

- Langley, B., Ariel, B., Tankebe, J., Sutherland, A., Beale, M., Factor, R., & Weinborn, C. (2021). A simple checklist, that is all it takes: A cluster randomized controlled field trial on improving the treatment of suspected terrorists by the police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17(4), 629–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09428-9

- Lamb, M. E. (2016). Difficulties translating research on forensic interview practices to practitioners: Finding water, leading horses, but can we get them to drink? The American Psychologist, 71(8), 710–718. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000039

- Lavoie, J., Wyman, J., Crossman, A. M., & Talwar, V. (2021). Meta-analysis of the effects of two interviewing practices on children’s disclosures of sensitive information: Rapport practices and question type. Child Abuse & Neglect, 113, 104930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104930

- Leach, C. L., Brown, F., Pryor, L., Powell, M., & Harden, S. (2022). Eliciting an offence narrative: What types of questions do forensic mental health practitioners ask? Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 30(4), 536–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2022.2059029

- Leach, C. L., & Powell, M. B. (2020). Forensic risk assessment interviews with youth: How do we elicit the most reliable and complete information? Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(3), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1734982

- Letourneau, E. J., Henggeler, S. W., McCart, M. R., Borduin, C. M., Schewe, P. A., & Armstrong, K. S. (2013). Two-year follow-up of a randomized effectiveness trial evaluating MST for juveniles who sexually offend. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 27(6), 978–985. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034710

- Martschuk, N., Powell, M. B., Blewer, R., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2022). Legal decision-making about (child) sexual assault complaints: The importance of the information-gathering process. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 34(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2021.1978213

- Mazerolle, L., Bennett, S., Davis, J., Sargeant, E., & Manning, M. (2013). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: A systematic review of the research evidence. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(3), 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9175-2

- McNiel, D. E., Sandberg, D. A., & Binder, R. L. (1998). The relationship between confidence and accuracy in clinical assessments of psychiatric patients’ potential for violence. Law and Human Behavior, 22(6), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025754706716

- Milne, B., & Powell, M. (2010). Investigative interviewing (pp. 208–214). Cambridge University Press.

- Monahan, J., Steadman, H. J., Silver, E., Appelbaum, P. S., Robbins, P. C., Mulvey, E. P., Roth, L. H., Grisso, T., & Banks, S. (2001). Rethinking risk assessment: The MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, K., Mazerolle, L., & Bennett, S. (2014). Promoting trust in police: Findings from a randomised experimental field trial of procedural justice policing. Policing and Society, 24(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2013.862246

- Murray, J., & Thomson, M. E. (2010). Applying decision-making theory to clinical judgements in violence risk assessment. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 6(2), 150–171.

- Orbach, Y., Hershkowitz, I., Lamb, M. E., Sternberg, K. J., Esplin, P. W., & Horowitz, D. (2000). Assessing the value of structured protocols for forensic interviews of alleged child abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(6), 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00137-x

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using the SPSS program. Allen & Unwin.

- Petersilia, J. (2003). When prisoners come home: Parole and prisoner reentry. Oxford University Press.

- Powell, M. B., & Brubacher, S. P. (2020). The origin, experimental basis, and application of the standard interview method: An information‐gathering framework. Australian Psychologist, 55(6), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12468

- Powell, M. B., Goodman-Delahunty, J., Deck, S. L., Bearman, M., & Westera, N. (2022). An evaluation of the question types used by criminal justice professionals with complainants in child sexual assault trials. Journal of Criminology, 55(1), 106–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/26338076211068182

- Powell, M. B., & Guadagno, B. (2008). An examination of the limitations in investigative interviewers’ use of open-ended questions. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 15(3), 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710802101621

- Powell, M. B., & Snow, P. C. (2007). Guide to questioning children during the free‐narrative phase of an investigative interview. Australian Psychologist, 42(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060600976032

- Powell, M. B., Wright, R., & Clark, S. (2010). Improving the competency of police officers in conducting investigative interviews with children. Police Practice and Research: An International Journal, 11(3), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260902830070

- Proctor, E. K. (2002). Decision-making in social work practice. Social Work Research, 26(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/26.1.3

- Rajlic, G., & Gretton, H. M. (2010). An examination of two sexual recidivism risk measures in adolescent offenders: The moderating effect of offender type. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(10), 1066–1085. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810376354

- Read, J. M., & Powell, M. B. (2011). Investigative interviewing of child sex offender suspects: Strategies to assist the application of a narrative framework. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 8(2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.135

- Read, J. M., Powell, M. B., Kebbell, M. R., & Milne, R. (2009). Investigative interviewing of suspected sex offenders: A review of what constitutes best practice. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 11(4), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2009.11.4.143

- Rich, P. (2015). Assessment of risk for sexual reoffense in juveniles who commit sexual offenses. In National criminal justice association, sex offender management assessment and planning initiative (juvenile section) (pp. 269–301). Office of Justice Programs.

- Robertson, R. E., Tran, F. W., Lewark, L. N., & Epstein, R. (2018). Estimates of non-heterosexual pralence: The roles of anonymity and privacy in survey methodology. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1069–1084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1044-z

- Schwalbe, C. S., Fraser, M. W., Day, S. H., & Cooley, V. (2006). Classifying juvenile offenders according to risk of recidivism: Predictive validity, race/ethnicity, and gender. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33(3), 305–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806286451

- Skowron, C. (2005). Differentiation and predictive factors in adolescent sexual offending [Doctoral dissertation]. Carleton University.

- Taylor, B. J. (2012). Models for professional judgement in social work. European Journal of Social Work, 15(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.702310

- Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Viljoen, J. L., Elkovitch, N., Scalora, M. J., & Ullman, D. (2009). Assessment of reoffense risk in adolescents who have committed sexual offenses: Predictive validity of the ERASOR, PCL: YV, YLS/CMI, and Static-99. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(10), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809340991

- Viljoen, J. L., Mordell, S., & Beneteau, J. L. (2012). Prediction of adolescent sexual reoffending: a meta-analysis of the J-SOAP-II, ERASOR, J-SORRAT-II, and Static-99. Law and Human Behavior, 36(5), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093938

- Vincent, G. M., Chapman, J., & Cook, N. E. (2011). Risk-needs assessment in juvenile justice: Predictive validity of the SAVRY, racial differences, and the contribution of needs factors. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810386000

- Worling, J. R., & Curwen, T. (2001). Estimate of risk of adolescent sexual offense recidivism (ERASOR; Version 2.0). Coding Manual. Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services.

- Wright, R., & Powell, M. B. (2006). Investigative interviewers’ perceptions of their difficulty in adhering to open-ended questions with child witnesses. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 8(4), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2006.8.4.316

Appendix A:

Interview questions

Demographic questionnaire

Before we begin the interview, I’d like to learn a bit about yourself, who you are, your background. If you’re happy to begin, I’ll start with some demographic questions.

What is your professional background?

What is your highest level of qualification?

What year did you complete the above training?

For how many years have you been working in your profession?

For how many years have you been working in your current position?

Have you done a training course in interviewing before? (If yes, please describe briefly)

Have you used the ERASOR before? (If not, any other risk assessment tools?)

What is your age?

What is your gender? Male/female/other

Case study questions

Now, I’m going to ask you some questions about the transcript of the case study that you read.

Did you read the Hunter or Rowan case study?

What was the overall risk level that you gave (Hunter/Rowan)?

What are the main factors you took into account in making your judgement about the risk of (Hunter/Rowen)?

How confident, would you say you are, in your risk assessment of (Hunter/Rowan) on scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely) confident?

What are your reasons for rating (Hunter/Rowan) a (X) out of 7?

What other information could have aided your decision?

How would that information have influenced your assessment of (Hunter/Rowan’s) risk?

What was your overall impression of the interview?

How did your impression of the interview impact your decision on (Hunter/Rowan’s) risk level?

Before we finish for today, I would like you to answer a few scale questions in the link that I am going to give you in the chat option. Please indicate to what extent you disagree or agree on a scale of 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (fully agree) with each of the statements. Please let me know when you’re done.

Appendix B.

Online survey questions

Please indicate to what extent you disagree or agree with the following statement:

(1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Somewhat disagree; 4 = Neutral; 5 = Somewhat agree; 6 = Agree; 7 = Strongly agree)

The interviewer was neutral in their treatment of the young person.

The interviewer gave the young person the opportunity to provide his story.

The interviewer was judgemental.

The interviewer could have phrased questions in a better way.

The interviewer was respectful to the young person.

The interviewer acted in the best interest of the community.

The interview was fair.

The interview tactics violated the rights of the young person.

The interview obtained sufficient information.

Table 1. Perception of interview quality and experimental group.

Table 2. Participant perceptions of the risk assessment interview.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and Spearman’s rho correlations for procedural justice items and confidence.

Table 4. Association between procedural justice elements and confidence levels.

Table 5. Difference between perception of procedural justice and experimental group.

Table 6. Association between perception of interview quality and procedural justice.