Abstract

Lawyers experience disproportionately high levels of poor mental health outcomes compared to other professions. This persistent problem can be explained, at least in part, by the fact that current initiatives are not adequately addressing the impact of trauma (from clients and lawyers). The legal profession is yet to embrace trauma-informed practice in the same way other human services have. In this qualitative study, 6 lawyers from Legal Aid describe what trauma-informed practice would ideally look like in their workplace. Many of the recommendations made by the participants such as training for staff, reduction in workloads, mental health leave, supervision, reflective practice, and debriefing are echoed in the literature. However, participants added valuable details about what service provision for clients, and the role of managers in bringing about change. The study provides employers with practical strategies to implement trauma-informed practice and manage the impact of trauma on their lawyers.

Introduction

Mounting evidence reveals that lawyers around the world experience high levels of mental illness such as depression, anxiety and burnout (Fah, Citation2021; International Bar Association, IBA, Citation2021; Kelk, Citation2009). The rates have been found to exceed those found in other professions (Beaton Consulting for Beyond Blue, Citation2007, Citation2011; Iversen & Robertson, Citation2021), even the mental health profession (Levin & Greisberg, Citation2003; Maguire & Byrne, Citation2017). In response, employers have implemented well-being initiatives such as providing several free counselling sessions a year (employee assistance program, EAP), but studies reveal that these measures have been limited in their impact (Chan et al., Citation2014; Fah, Citation2021; Poynton et al., Citation2018; Vlahos, Citation2021). Primary interventions that empower the employee to manage their own mental health (such as being able to take days off, flexible work practices, having control over their work) have been found to be more effective than measures that are reactive and are designed to treat, compensate and rehabilitate workers (Chan et al., Citation2014; Poynton et al., Citation2018).

One key to mental health management for those in the legal aid profession is being equipped to deal with the impact of past trauma of both clients and themselves. Although the definition of trauma continues to be contested throughout the literature, this paper uses the definition adopted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration in the USA (SAMHSA), ‘individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being’ (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMHSA, Citation2014, p. 7). Unlike everyday stress, the threat (from an event or series of events) triggers the survival flight/fight response as a protective mechanism. If the trauma is not processed, the person can experience long-term negative effects on their functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional and spiritual well-being (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, Citation2016; SAMHSA, Citation2014, p. 7).

Many lawyers (especially those working for public legal assistance organisations like Legal Aid Commissions) work with distressed clients whose interpersonal skills and behaviour are affected by their experience of trauma. Legal Aid Commissions are funded by the State and Federal Government, and this funding is allocated to specific areas of law, such as criminal law, family law or civil law (this includes mental health, elder abuse, National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and projects such as helping people engage with a Royal Commission). The lawyer is usually responsible for meeting with the client, collecting information, facilitating the financial aid process, taking instructions and then providing advice and/or representation through the courts or a tribunal. There are often high workloads and funding and time restraints on what can be provided (James, Citation2020). Accessing legal assistance through legal aid is restricted to those who cannot afford a private lawyer or those that belong to a specialist group that the Government thinks need additional assistance navigating the legal system – for example, elderly people experiencing abuse.

Legal aid clients usually come from low socio-economic backgrounds, face a number of complex issues in addition to their legal matter (such as mental health issues and homelessness) and are often emotionally heightened at the time they approach legal aid, and their cases often relate to stressful events such as those in criminal or family law proceedings. In addition to these factors, the work of lawyers in Legal Aid Commissions is more regulated than that in private practice, with greater surveillance and less face-to-face time with clients (Cooke, Citation2021).

All of this can expose the lawyer to traumatic material and difficult interactions with clients impacted by trauma, giving rise to a significant risk of vicarious trauma. Vicarious trauma is defined by McCann and Pearlman (Citation1990) as a range of psychological effects from engaging with traumatic material that can include changes in the person’s beliefs about safety, trust, control, esteem and intimacy. Whilst the definitions of vicarious trauma, and other common conditions such as compassion fatigue and burnout, remain hotly contested in the literature (Iversen & Robertson, Citation2021; James, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2022; Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Pirelli et al., Citation2020) and are not mentioned within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, APA, Citation2013) used to diagnose clients, they refer to various aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and are often comorbid with conditions like depression and anxiety (Bride et al., Citation2007), all of which are clear and empirically valid constructs.

The risk of vicarious trauma is higher if the lawyer has personal unprocessed trauma that they bring to their work with clients (Leclerc et al., Citation2020; Maguire & Byrne, Citation2017; Vrklevski & Franklin, Citation2008). The risk is also heightened by general characteristics of the legal profession such as the stigma attached to experiencing mental illness, the competitive and adversarial nature of the profession, and the traditional lack of training, self-care and supervision (James, Citation2020).

The impact on lawyers in the sector was seen in a recent case where a Victorian Public Prosecutor sued the Victorian Government after she developed a psychiatric injury (PTSD and depression) from her exposure to trauma at work (and received insufficient support from her employer). The matter went to Australia’s High Court which emphasised the responsibility of employers to implement proactive measures to protect the mental health of their staff where there are known risks (Kozarov v Victoria, Citation2022) (‘Kozarov’). This case highlights the need for legal workplaces to address the impact of trauma to meet their duty of care to provide a psychologically safe workplace.

Unfortunately, research on trauma and lawyers is limited to a few studies considering vicarious trauma and other conditions such as compassion fatigue (Leclerc et al., Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2021; Levin et al., Citation2011, Levin & Greisberg, Citation2003; Rønning et al., Citation2020; Vrklevski & Franklin, Citation2008), especially in criminal law (Burton & Paton, Citation2021; Iversen & Robertson, Citation2021; Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Leonard et.al., 2021; Vrklevski & Franklin, Citation2008). Whilst a couple of studies focus on lawyers working with clients seeking asylum (Piwowarczyk et al., Citation2009; Rønning et al., Citation2020), there is a lack of research to date that specifically looks at the incidence of vicarious trauma in Legal Aid Commissions.

Many other human services (such as the mental health profession) have responded to the growing body of trauma research over the last 20 years by trying to become what Harris and Fallot (Citation2001a, Citation2001b) first described as a ‘trauma-informed service system’. Trauma-informed practice essentially involves helping staff to recognise and understand how trauma might be impacting upon their clients and themselves and adjusting the way services are provided to ensure the safety of both (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, Citation2016; SAMHSA, Citation2014). The definition of trauma-informed practice used here has drawn from the approaches of SAMHSA (Citation2014) and Kezelman and Stavropoulos (Citation2016) from the Blue Knot Foundation in Australia:

Every member of an organisation acknowledges the prevalence of trauma and understands how it can affect a person’s thoughts and behaviours, recognising that the person’s behaviours may have been an adaptive coping mechanism at some point (‘trauma response’), and that trauma is something that ‘happened to them’, not something that is ‘wrong’ with them (see also Bloom & Sreedhar, Citation2008). In our context, this point means acknowledging that everybody involved in the legal process (including clients and lawyers) may be impacted by past trauma.

Every person in the organisation is committed to bringing about a trauma-informed workplace, and actively integrates knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures and practices (SAMHSA, Citation2014, p. 9). This includes adjustments at every level of the organisation, from service delivery and workplace practices, so that every person involved (staff and clients) feels safe and is not retraumatised (or experiences vicarious trauma) during their work (lawyers) or contact with the service (clients). This includes recognising and promoting each person’s strengths and resilience (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, Citation2016; Randall & Haskell, Citation2013, p. 509); and making referrals to organisations that provide interventions/support to address trauma if this cannot be provided by the organisation.

Whilst there is no model of trauma-informed practice that has been developed for the legal assistance sector, each of the various models of trauma-informed practice that exist for other areas requires implementation of a set of principles. SAMHSA (Citation2014) identify these as: ‘safety, trustworthiness & transparency, peer support, collaboration & mutuality, empowerment & voice & choice, and culture/historical/gender issues’ (p. 10). Whilst these principles can appear abstract, ongoing discussion of how they can be better integrated into every level of the organisation is essential to bringing about a trauma-informed workplace.

There are numerous instruments available to measure whether an organisation is trauma informed (Thirkle et al., Citation2021), and some studies demonstrate that particular models of trauma-informed practice have in fact had a positive impact on the well-being of staff (James, Citation2020, p. 285; Manian et al., Citation2021). But what this looks like in practice varies, because there are a number of different models (James, Citation2020), and these have been adapted to specific professions and cohorts of clients. Whilst there is no one clear model that has been advanced, and there are no reports of applying one of these models to the legal context (James, Citation2020), the basic tenets of trauma-informed practice are consistent across the board and are very relevant to the legal profession.

A decade ago, Randall and Haskell acknowledged that ‘the idea that law . . . should be trauma informed is novel and, as a result underdeveloped’ (Randall & Haskell, Citation2013, p. 501). Three years later, Kezelman and Stavropoulos (Citation2016) identified the need for a paradigm shift where ‘everyone involved will experience a profound and comprehensive shift in existing ways of operating’ (p. 7). Despite repeated calls to action (James, Citation2020; Vlahos, Citation2021), there is no research that explores what a trauma-informed legal workplace could look like and whether this would improve the mental health and safety of lawyers, other staff and clients. This study seeks to begin to address this gap by asking lawyers (within the specific setting of legal aid) to describe what a trauma-informed workplace would ideally look like from their perspective. There is no model of trauma-informed practice that has been tailored to the legal profession, so it is proposed that the data collected here would be used in further research to develop a model that can be implemented and assessed for its effectiveness at improving the mental health and safety of lawyers, other staff and clients.

Method

Study participants and recruitment

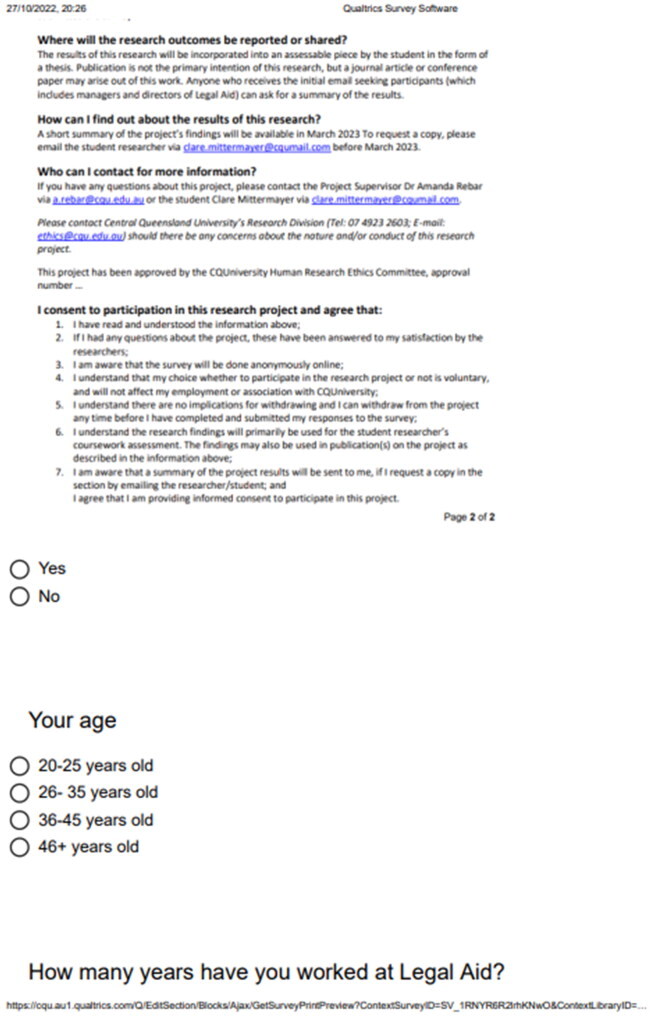

The study used a purposive sampling strategy to select participants that can speak to the research topic (Tie et al., Citation2019). Lawyers working for legal aid in two Australian States received an email from their director inviting them to consider participating in the study. To be eligible to participate, lawyers needed to have worked for legal aid and with clients within the last 10 years. The email directed the potential participant to read an attached Summary of Trauma Informed Practice (Appendix A) before clicking on a link to be taken to the information and consent form. They needed to provide their consent to continue (by ticking a box) before being able to answer the 14 questions in a Qualtrics Survey (Provo, UT; Appendix B), which was all expected to take about 20 minutes to complete. Once the researcher had received sufficient responses, the Qualtrics survey was closed to further participants due to time constraints in completing the project.

The researcher chose the grounded theory method in the collection of data. This would normally require the researcher to continue to collect data (and not limit the sample size) until the researcher achieved theoretical saturation of the emerging concepts (i.e. they find no new properties emerging from the data; Charmaz & Thornberg, Citation2021). In this case, however, the project sample was limited (and the number of times those participants were contacted was only once). This was justified using the description of saturation put forward by Guest et al. (Citation2020) who used bootstrapping analysis to find that ‘typically 6–7 interviews will capture the majority of themes in a homogenous sample (6 interviews to reach 80% saturation)’ (pp. 13–14).

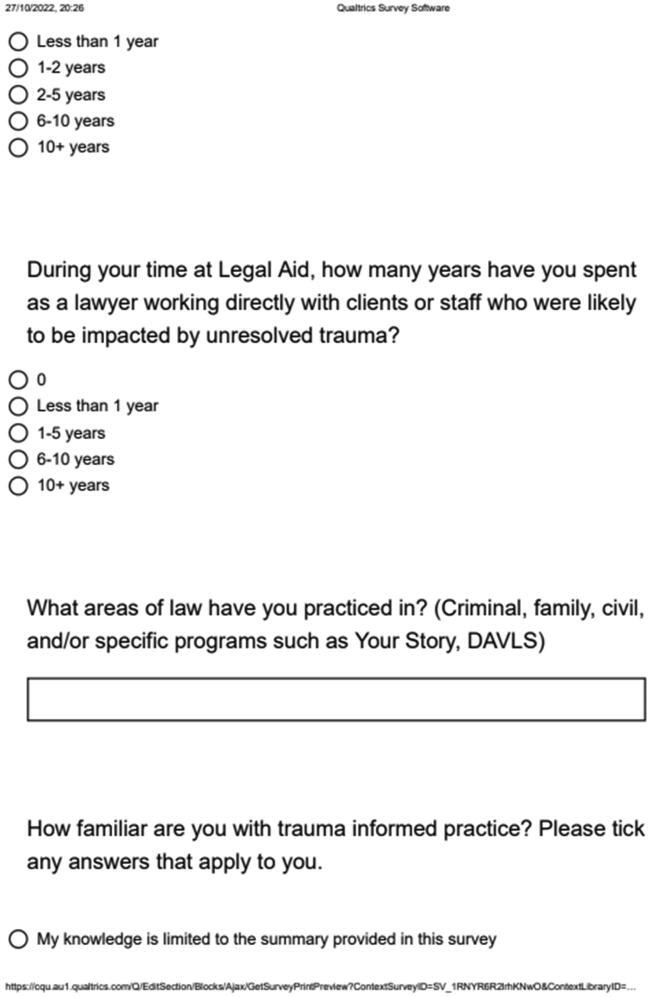

Lawyers working for legal aid who had not had direct contact working with clients in the last 10 years were excluded from the study because they may not have recently experienced the challenges of working with clients impacted by trauma and managing their own mental health (in terms of personal or vicarious trauma). The study was also restricted to lawyers and did not include support/administration staff and other employees within legal aid such as those working in policy, human resources and information technology. Whilst there is evidence to suggest that support staff in legal aid workplaces may also be impacted by trauma (Iversen & Robertson, Citation2021), this study was confined to lawyers because the roles (and exposure to clients) can be quite different. The study did not extend to lawyers in private practice (i.e. law firms and barristers) for the same reason. Whilst lawyers in firms (and barristers) may see clients that are funded by legal aid, it is usually only a part of their work; their firm is not publicly funded, and their working conditions are often different (e.g. billable hours). Lawyers working in areas where research has identified as involving risk of vicarious trauma, such as criminal law (see above), were not specifically targeted because it was assumed that any lawyer working with legal aid clients could be exposed to the risk of vicarious trauma given the inherent nature of the work and clients.

Though nine lawyers participated in the survey, the results of only six were recorded because three participants failed to sign (tick the box for) the informed consent form, and their data were therefore omitted from analysis. Whilst the response rate was low, it is hypothesised that those that did respond were likely to be people who had knowledge and an interest in the subject, which is helpful for the project.

Study design

The Qualtrics survey used open-ended questions to collect qualitative data from six lawyers who work for Legal Aid Commissions in Australia. A qualitative design was adopted because it allowed the clients to go beyond prescriptive answers and contemplate what changes they thought would improve the service for themselves and their clients (in terms of being trauma informed). This was important because there is no trauma-informed framework or model that has been adapted to the legal profession yet, and any attempt to create one in the future would benefit from the personal perspective of lawyers who are working in the field and are going to have insight into what is needed for their workplace to be trauma informed.

Grounded theory method was used to gather, synthesise and analyse the data. This systematic yet responsive method, developed by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), was initially thought to be a good fit for this study because it is flexible and can analyse human experience in a field where there has not been any prior similar research (Charmaz, Citation2008, p. 107). Additionally, it does not start with a specific hypothesis that is then tested. Instead, it uses an inductive approach that allows the data from lived experience to form the theory, enabling the participants’ contribution to determine the outcome (Tie et al., Citation2019). Starting with a predetermined theory or hypothesis was not possible in this case because, as noted above, there is no trauma-informed model or framework that has been fitted to the legal profession yet. Using this method allowed the researcher to begin with asking the participants to describe trauma-informed practice (and the implementation of the principles) in their specific setting. The researcher was then guided by these perspectives and those recommended in the literature. Therefore, the resulting constructed idea or picture of what a trauma-informed legal aid workplace would ideally look like was grounded in the data. Using this method meant that another researcher could follow up with the same questions with other Legal Aid Commissions, conduct a comparative analysis (Tie et al., Citation2019) and allow the new set of data to continue to inform the theory or construct. Alternatively, future researchers can use this material to develop a specific trauma-informed model that is suitable for legal aid. With hindsight, the authors believe that using the method of reflexive thematic analysis would have been a more appropriate method. This is discussed in the Limitations section later.

Data collection

The survey contained 14 questions (including the question about providing informed consent to participate). The use of open response options gave the participants the ability to provide rich data from their own lived experience. Responses ranged from a few words to a paragraph. This was important in this case, because one of the aims of the study was to collect concrete data of what trauma-informed principles could look like in practice within a legal aid workplace. This also meant that if a participant made a recommendation and it was not ‘strong’ in terms of the frequency with which it was mentioned by others, it was still a valuable contribution to the overall results and may in fact offer insights that writers in the field may not have considered.

The one-page Summary of Trauma Informed Practice (Appendix A) that was attached to the email inviting lawyers to participate was based upon the model used by SAMHSA (Citation2014) and an article by Kezelman and Stavropoulos (Citation2016) from the Blue Knot Foundation in Australia. The approach of the SAMHSA was adopted because it is often used, has been empirically validated (Manian et al., Citation2021) and has been considered in a legal context (James, Citation2020; McKenna & Holtfreter, Citation2021; Swanson, Citation2019). The work of Kezelman and Stavropoulos (Citation2016) was also incorporated because their article considered trauma-informed practice within the Australian legal context.

To manage the small potential risk of discomfort that may have arisen for participants when they were prompted to think about stressful circumstances at their workplace or with clients (e.g. where they may not have felt safe or supported in a trauma-informed way), the participants were provided with a list of local and national support services in the initial email and at the end of the survey. They were also provided with the contact details of the researcher and supervisor if they had any questions or concerns.

No identifying information was collected, and if a participant was interested in obtaining a summary of the results from the study, they were directed to contact the researcher’s supervisor. These steps ensured that the researcher had no way of knowing who had participated in the study. Anonymity meant the participants were more likely to feel comfortable disclosing aspects of their workplace that they believed needed to change, and/or their own personal experiences on the subject. This was particularly important in this context, due to the evidence that there is a stigma in the legal profession about speaking out about mental illness (Fah, Citation2021; IBA, Citation2021; Kelk, Citation2009; Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Poynton et al., Citation2018).

There was a potential risk of influence by the researcher on participants because she was a lawyer in legal aid at the time of collecting data. To minimise this risk, her role in legal aid was declared to participants in the invitation to participate, and this invitation was sent out by the directors of legal aid (instead of the researcher). Participants were advised that their participation was anonymous and would have no impact upon their relationship with legal aid (nor would their managers be informed of their involvement), and they could withdraw at any point (without consequence). The researcher’s role in legal aid arguably also raised the potential risk of bias during the stages of interpretating and analysing the data. This risk was minimised by including participants from workplaces that included, but were not limited to, her place of employment. Furthermore, the researcher’s supervisor engaged the strategy of triangulation, by checking her work during the analysis stage to ensure that the results reflected the data and had not been impacted by researcher bias. Having said this, the researcher’s profession in legal aid provided content knowledge that was an advantage in interpreting what the participants were referring to in their answers.

Data management and analysis

Once the survey was closed, the responses remained on a secured Qualtrics site, and were downloaded and stored on a password-protected Word document file that could only be accessed by the researcher. The computer the file was stored on was also password protected. The only person that had access to the data during analysis was the researcher’s supervisor who reviewed the process of analysis to ensure there was no researcher bias. The data will be stored indefinitely on CQUniversity electronic, password-protected servers.

Once the surveys had been completed, the results were printed. This included a list of the participants’ answers under each question. Each of the answers to the questions were read carefully and coded for relevant recommendations under each of the questions. Often the participants made the same recommendations, and the frequency was noted next to the recommendation as part of the coding process. Salient quotes from the participants were recorded during the coding process and were later used in results to support thematic assertions (Tie et al., Citation2019).

The second stage of analysis involved a more advanced process of intermediate coding (Birks & Mills, Citation2015). All the comments across the questions were analysed, and similar-themed comments were combined under a particular category. This category was a specific recommendation (see the list below) that now included relevant comments and quotes of the participants. This was an active process of synthesising the data without compromising it. Each recommendation reflected a concrete suggestion that emerged from the data, creating a picture of what a trauma-informed workplace would look like for the participants.

Suggestions for the physical environment that reflect trauma-informed principles

Recommendation that all staff receive training in trauma-informed practice and mental health

Noticing the impact of trauma on lawyers – screening, check-ins and reflective practice

Debriefing and discussion at team meetings

Supervision for lawyers

Support for lawyers from management

Cultural change in the workplace

Organisational policies and practices, e.g. leave

Trauma-informed service for clients

Trauma-informed practice of third parties

Organisational obstacles to becoming a trauma-informed workplace: time restraints, workload, budget restraints and inadequate technology.

At this point the second author checked the recommendations and associated comments and quotes against the initial data collected from the survey. This process of triangulation ensured that the data were accurately presented in the findings after analysis.

The final aspect of analysis required the researcher to compare this picture to what is suggested in the literature (Charmaz & Thornberg, Citation2021). The literature was reviewed to identify suggestions for trauma-informed practice in a legal context, including interventions to reduce the risk of vicarious trauma. As mentioned above, there were not specific studies that address the first of these specifically, but there is a growing body of literature that includes articles, tool kits and guidelines. In this paper, these contributions were compared with the data in each of the categories above. The results under each of these final categories from the participants and literature were then summarised and added to the next section.

Results and discussion

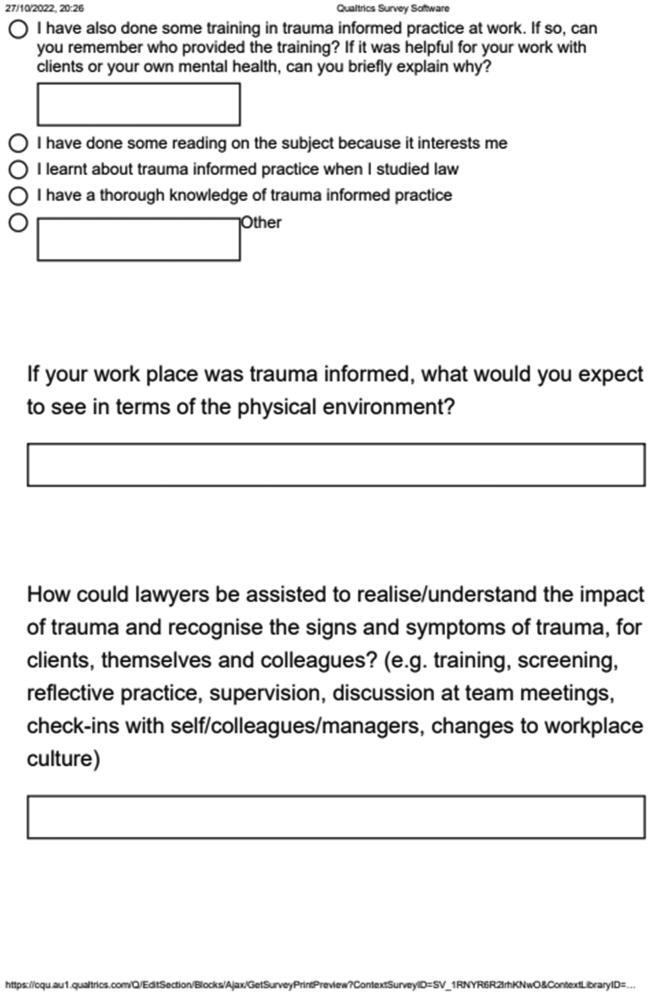

In terms of participant demographics, three of the six participants were between 26 and 45 years old, and three were older than 45 years of age. Half had worked at legal aid for 1–2 years and half for 6+ years. Four participants had spent 1–5 years working directly with clients or staff likely to be impacted by trauma and 2 for 10+ years. The legal practitioners work in civil, criminal and family law. Four participants had done training in trauma-informed practice, and one explained that they had a thorough knowledge of trauma-informed practice.

What follows is a synthesis of the data from the participants (concrete suggestions they made) with the recommendations found in the literature. The discussion of these results is integrated in each recommendation. The first 11 recommendations were advanced by the participants. The final three recommendations feature prominently in the literature, though not in the data from the participants in this study.

Suggestions for the physical environment that reflect trauma-informed principles

The participants made quite a few recommendations about how the physical environment can support a trauma-informed service, most of which related to ensuring their clients feel safe and supported. It was recommended that to be trauma informed, upon entering the building, the client should feel safe and welcomed, which included approachable reception staff and a safe waiting area (Participants 4 and 5). Participants 1 and 3 recommended that there should be no large barriers between clients and lawyers in the initial meeting room, and this space should be open, safe and welcoming so the client feels comfortable. There should be ‘thoughtful design of the décor’ (Participant 5), and the room should be large, calm, quiet and soundproof, and have good ventilation, calm colours on the walls and no harsh lighting (Participant 3). Participants 3 and 4 suggested that tissues and water should be available for the client, with Participant 1 also recommending they be offered tea or coffee too. One of the participants recommended that there is provision of care for children so the children do not have to sit in and listen to their parents speak to the lawyer about subjects that may not be appropriate for them (Participant 4). It was also suggested that clients should be able to leave the session and take a break, going to an inviting place, with easy access to toilets (Participants 1 and 6). Overall, the participants clearly articulated that for them, trauma-informed practice went beyond interpersonal relations and extended to the physical environment.

In relation to lawyers, Participants 1 and 2 recommended that they know about the organisation’s emergency procedures and have access to alert/duress alarms. Mention was also made of not being physically isolated from colleagues and the value of having an open plan that would facilitate regular conversations/debriefing opportunities between lawyers (Participant 1). Participant 4 recognised the constraints of having to use badly designed buildings such as courts. There is a growing body of literature that describes how to create environments that enable trauma-informed services (Covington, Citation2016; Homes & Grandison, Citation2021).

Recommendation that all staff receive training in trauma-informed practice and mental health

The participants were unanimous in advocating for all staff (and not just lawyers) in the workplace to receive training in trauma-informed practice. Individual participants recommended the training be tailored to the workplace (Participants 4 and 5); that it should be offered at the outset of employment (Participant 3); that it should be mandatory (Participants 2, 3 and 4); that additional refresher skills training is offered (Participant 3); and that training should be provided regularly (Participant 2). Participants 3 and 4 were specific that the training should include teaching lawyers to recognise signs and symptoms of trauma (and respond appropriately). ‘People need specific personalised examples to start to develop an idea of the complexity of trauma, especially when it is inflicted by a family member or other ongoing relationship’ (Participant 4).

In response to several questions, participants reiterated the need for training to be reviewed by management – for example, ‘follow-up from management as to how they found the training or how to incorporate TIP into daily practice’ (Participant 6). The participants were not asked about whether any initiatives (such as training) were currently in place in their workplace, but Participant 3 did confirm that some education in trauma-informed practice and self-care is being facilitated, and another said managers had not been investing in staff training across the board (Participant 2). The data revealed that whilst some training is being provided, more was needed, and it required engagement from management afterwards.

Training was one of the recommendations made by the High Court in the Kozarov case (2022), and it finds resonance in the literature (Field et al., Citation2016; Hodge & Williams, Citation2021; James, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2022; Sutton et al., Citation2022). Several sources discussed the need for training in trauma-informed practice that extended to training in mental health (Burton & Paton, Citation2021; Field et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2022; Niebler, Citation2019). Field et al. (Citation2016) recommended the training include equipping lawyers with the skills and resilience to manage stressors. The study by Poynton et al. (Citation2018) showed that staff in an organisation like legal aid rated training as more effective when it included ‘real practical strategies they could implement to help them manage stress on a day-to-day basis’ (p. 612). The same study also said training was more effective when the organisation supported its implementation (p. 613), which is consistent with the findings in this study.

Noticing the impact of trauma on lawyers – screening, check-ins and reflective practice

There was strong support from participants for lawyers to receive support in noticing the impact that trauma may be having on them. This included calling for initiatives such as having access to screening for negative impacts of trauma (Participants 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6); check-ins (all six participants); and integrating reflective practice into daily work (all six participants). No comments were added to the recommendation from five participants for screening; however, in relation to check-ins, participants proposed this go beyond checking in with oneself to receiving check-ins from colleagues and managers (Participants 4 and 5). One participant added that the check-in should extend beyond ‘checking up on the well-being of the lawyer to ensure the employee was engaging in trauma-informed practices’ (Participant 1). Outside of this study, ‘welfare checks’ were one of the measures proposed by the High Court in the Kozarov case (2022). Furthermore, Nomchong (Citation2017) suggested the ‘well-being checks’ should be done by mental health professionals, and Poynton et al. (Citation2018) found that check-ups needed follow-up so as not to be seen as a ‘tick the box’ exercise.

All the participants mentioned the need for reflective practice in the workplace (Burton & Paton, Citation2021, and M’baku, Citation2021, support this). Participant 5 said, ‘cultural change would be needed to make it common place’, and ‘it needs to be supportive by management’, but no comments were made about what reflective practice meant for them personally. The researcher proposes the participants may have been thinking of opportunities to reflect back on their work and assess their response and any impact upon themselves. In relation to team meetings, one person wrote, ‘we could discuss what trauma responses we experienced in clients and ourselves and how we responded’ (Participant 1). If this is true, reflective practice could theoretically include the screening and check-ins mentioned here, but also the debriefing opportunities, discussion at team meetings and supervision – all of which are covered in the next two recommendations. It was interesting that one of the participants suggested lawyers might need prompting to engage in reflective practice. ‘Reflective practice is essential but not everyone is equipped to do this without prompting, that’s when appropriate management should be involved’ (Participant 6). Another person wrote, ‘it needs to be ok for a manager or colleague to highlight when we look stressed’ (Participant 1). The comments and support for the general idea of reflective practice arguably warrant further exploration of what reflective practice means for lawyers and how they can be encouraged to use it as part of their work.

Debrief and discussion at team meetings

Participants supported the practice of including a discussion about trauma-informed practice into team meetings: ‘We could discuss what trauma responses we experienced in clients and ourselves and how we responded’ (Participant 1). Another participant said it would give staff an opportunity to update their knowledge of trauma-informed practice and consider how it relates to themselves and their work in a practical way (Participant 4). A third person surmised, ‘it helps staff integrate what they have learnt’ (Participant 1). The idea of discussing the impact of trauma at team meetings was also proposed in the Kozarov case (2022), but is rarely mentioned in the literature (James, Citation2020).

Having opportunities to debrief after a challenging experience at work was mentioned by participants in this study (and several commentators: Burton & Paton, Citation2021; Niebler, Citation2019; Nomchong, Citation2017). ‘There needs to be better networks internally that includes regular opportunities to debrief’ (Participant 2), where you have the ‘ability to talk to colleagues without feeling like you are wasting time’ (Participant 1). However, caution was expressed by one participant about who lawyers debrief with, due to the risk of traumatising the other person (Participant 3), which leads into the next recommendation.

Supervision for lawyers

Whilst supervision could be considered part of reflective practice and debriefing, it has been given its own recommendation in the results due to the strength of support from both participants in this study and the literature. Whether it was internal or external, all the participants supported the provision of supervision in their workplace. One person added that it needed to be supported by management (Participant 3). Participants 1 and 3 clarified that the supervision should be available regularly and with a psychologist, and one of these added that the supervision should be mandatory (Participant 3). One person acknowledged the funding challenges this could involve for legal aid (Participant 1).

Supervision has been found to be an effective intervention for vicarious trauma (James, Citation2020; Sutton et al., Citation2022). Burton and Paton (Citation2021) recommend supervision takes place with a psychologist. There is also support for related initiatives in the literature such as mentoring (Chan et al., Citation2014; see also Kozarov v Victoria, Citation2022). Staff in the Chan et al. (Citation2014) study rated similar initiatives such as health check-ups (41%) and EAP counselling (30%) as less effective. Though EAP counselling was rated more positively in the Poynton et al. (Citation2018) study, it was only accessed by 25–30% of the staff, which may indicate that it is only a helpful measure for a limited proportion of the workforce. These studies could be used to support the argument that the nature of supervision or regular professional support for lawyers needs to be both comprehensive and regular.

Support for lawyers from management

The need for support from management was a common theme across the survey. Participants clearly believed that management support was necessary for measures to be successful. This included supervision, reflective practice, discussion at team meetings, check-ins with peers and managers and general support. It was suggested that this support included going beyond referring an employee to a support service such as EAP counselling, and providing a warm referral to a reliable service and follow-up with the employee afterwards (Participant 6).

This was the only category in the results where participants shared their own experiences in the workplace. One participant wrote, ‘I felt gaslit by management, as if I was making too big a fuss and causing inconvenience . . . my manager still makes reference to how I coped during that stressful period, as if it were a weakness, rather than a natural response to an unnatural amount of stress’ (Participant 6). Another participant said managers seemed reluctant to support struggling staff except in the case where the employee is experiencing domestic violence (Participant 1). Participants were keen for managers to go beyond supporting them and to be guided by trauma-informed principles themselves: ‘Trauma-informed practice needs to be led by the managers, not just those at the coalface of service delivery . . . the managers need to commit to embedding trauma-informed practice . . . they need to lead from the top and by example’ (Participant 6).

Interestingly, there were not many references to management support in the literature. However, there is a call for managers to receive training to be able to identify warning signs and be able to respond (Chan et al., Citation2014; James, Citation2020; Poynton et al., Citation2018). The High Court mentioned responding to high workloads and interpersonal issues; the need for resources; and learning to consult meaningfully (Kozarov v Victoria, Citation2022). It was also clear in the research that staff thought managers need to do more (Vlahos, Citation2021) and that there was a lack of confidence in managers to respond (Beaton, 2011; Fah, Citation2021).

Cultural change in the workplace

Five of the six participants in this study said that cultural change was needed to imbed trauma-informed practices. This cultural change included two main efforts. The first was ensuring that trauma-informed practices ‘become our locus’ (Participant 6) and ‘inform everything we do’ (Participant 6). This included open recognition of the risk of vicarious trauma (Participant 4). The second is related and involves removing the stigma associated with experiencing mental illness in the workplace. ‘It needs to be okay for a manager or colleague to highlight when we look stressed’ (Participant 1). We need a ‘culture that is open to discussing and supporting struggling staff’ (Participant 1). Participants described how some lawyers may hold the view that they just need to ‘toughen up’, that there is a reluctance to be vulnerable and share mental illness, and there is still concern about how this will impact upon their career and perceived resilience (Participant 4). In sum, the participants were eager to see their workplaces develop a culture where trauma-informed practices are embraced and practised, and there is no longer a stigma or fear associated with experiencing or talking about mental illness in the workplace.

Howieson (Citation2011) describes how cultural change requires an understanding of the psychology of lawyers, before enabling, encouraging and engaging with them to change. This understanding of cultural change would certainly include the need to address any stigma to bring about the cultural change needed to implement trauma-informed practices. The need to address the current stigma against mental illness in the legal profession is widely recognised (Fah, Citation2021; Field et al., Citation2016; James, Citation2020; Kelk, Citation2009; Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Poynton et al., Citation2018). Other related fields, such as correctional care, have demonstrated that the implementation of trauma-informed practice can bring about a workplace with a culture of safety for clients and workers (Miller & Najavits, Citation2012).

Organisational policies and practices – for example, leave

Whilst participants mentioned the need for changing policies to account for trauma-informed practices (Participants 2 and 6), descriptions of what this might include were limited to recommendations about being able to take time off. This included being able to take sick leave or a mental health day when work becomes overwhelming (Participant 1).

Various articles in the literature emphasised the importance of having organisational policies and practices that support and facilitate the implementation of trauma-informed practices (James, Citation2020; SAMHSA, Citation2014). In Chan et al. (Citation2014), having time off was rated as highly or quite effective by 76% of the workforce. The call for mental health days (Hodge & Williams, Citation2021) and being able to take a break from work (M’baku, Citation2021; Nomchong, Citation2017) is defensible given the research that reveals a strong correlation between the level of trauma exposure and vicarious trauma levels (Iversen & Robertson, Citation2021) – this includes longer hours (Leclerc et al., Citation2020; Levin et al., Citation2011; Rønning et al., Citation2020) and years on the job (Leonard et al., Citation2021).

Trauma-informed service for clients

Interestingly, the participants had more to say about what could be done in practice to ensure a trauma-informed service for clients rather than for themselves. Five of the participants recommended having a social worker present and available to clients in all teams. Participant 1 mentioned that it was important for clients to feel welcome and heard at reception (and not have to wait too long), and another mentioned the need for an organisation-wide policy with standard practices (Participant 2). The rest of the comments about how to provide a trauma-informed service for clients related to the attitudes/beliefs, knowledge and skills of the lawyer. The following list reveals examples of each of these provided by participants:

The lawyer’s attitudes or beliefs about the client:

‘Accept the client, be understanding, and non-judgemental’ (Participant 1); ‘Treat client with respect’ (Participant 3); ‘Be conscious of building a rapport’ (Participant 4); ‘The most important shift is an underlying attitude shift. Lawyers need to see being trauma-informed as a key part of fulfilling their professional obligations and doing a good job as a lawyer (rather than seeing complex clients as being more time-consuming or a bit more inconvenient, etc.)’ (Participant 4).

It is essential that the lawyer has knowledge about the potential impact of trauma.

The lawyer’s skills in trauma-informed practice:

‘If it is appropriate, encourage the client to bring a support person to their meeting with the lawyer’ (Participant 6).

‘Ensure clients are triaged, and urgent needs are met first’ (Participant 4).

‘Welcome client face-to-face and not from a distance, walk with client to the room, give clients options of where to sit’ (Participant 3).

Adjusting general service delivery: It should be a ‘human-centred service so that the onus is not on clients to have all their papers in order before receiving a service’ (Participant 5). The ‘lawyer should ask what supports are needed and if there is anything that can be done to make the conversation easier for the person’ (Participant 3). ‘The client should feel heard and safe in terms of their culture’ (Participant 1). Participant 3 recommended being mindful of the language used and that communication is accessible (so they understand, feel safe and respected). Use plain English, ‘check that the client understands the advice and ask if they would prefer a different method for receiving the information e.g. written down’ (Participant 3). Repeat advice if necessary (Participant 1).

Taking information: ‘Give client your full attention, actively listen to what is shared, clarify what is not understood, give the client time to tell their story, be empathic and ensure the client feels heard and understood’ (Participant 1). ‘Maintain eye contact if appropriate’ (Participant 3). ‘Can you read their story somewhere else, so they don’t have to retell it to you? Do not ask personal questions unnecessarily and when you do – only once – and explain why. If taking personal information explain the organisation’s privacy and safe storage policy/practice’ (Participant 3).

Providing advice: ‘Be clear about what can be done and can’t be done’ (Participant 3), ‘give accurate information about options and risks’ (Participant 4).

Ensure the ‘client is empowered to choose what to do next and they feel like the lawyer trusts them to make decisions’ (Participant 1), and you are ‘mutually working to give clients real choices’ (Participant 3).

Referrals: Get permission to pass on the client’s story so that they don’t have to retell it. ‘Make connections easy but have good practices around confidentiality’ (Participant 3). ‘Know where the client can access psychological services or other supports and make warm referrals’ (Participant 3). ‘Staff should have an up-to-date list of legal and non-legal services to refer to and know what they can provide’ (Participant 3). Ensure organisations you refer to are trauma informed (Participants 1,2,3 and 6).

‘Thank them for using the service, if they agree, get feedback as to whether they felt safe or traumatised’ (Participant 3). ‘Follow through and do what you say you are going to do, on time. Report back and check in with the client’ (Participant 3), ‘efficiently transfer and call back’ (Participant 4).

‘Increased oversight and awareness to ensure that skills are evident, and training provided where not’ (Participant 6).

Sue and colleagues (Sue et al., Citation1982) have long argued that beliefs/values, knowledge and skills form the criteria for cultural competency in therapeutic interventions. What is required for lawyers varies depending on the Solicitor Conduct Rules in each state. The data here could arguably be used to develop the concept of competency in trauma-informed practice for lawyers.

Trauma-informed practice of third parties

Five of the participants recommended that private practitioners, court staff and members of the judiciary have training in trauma-informed practice, one going a step further to ask whether funding to private practitioners (who take on legal aid clients) could be contingent upon such training. One of the participants also recommended that legal aid meet with third parties to share deidentified feedback from clients to improve as a sector (Participant 6). Another participant suggested that Legal Aid Commissions could learn from each other and other legal assistance providers (Participant 2).

Organisational obstacles to becoming a trauma-informed workplace: time restraints, workload, budget restraints and inadequate technology

Four of the participants in this study raised heavy workloads as an obstacle to trauma-informed practice. They explained that this was true in terms of how the load impacted upon the lawyer and the risk of burnout (mentioned by two participants, one of whom called for increases in staffing to reduce the risk of burnout), but also on the quality of the service that the lawyer was able to provide the client. The lawyer may lack time to make a referral to a support service, cited one participant. Another added, ‘managing workload is huge and needs input and active management from leaders’ (Participant 3). This last comment emphasises the important role that managers play when allocating and managing the work of their team.

It is clear from the research that organisational factors contribute to the risk of vicarious trauma (Chan et al., Citation2014; Poynton et al., Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2022). One of the most frequently cited factors for lawyers is excessive workloads that lack diversity (Bergin & Jimmieson, Citation2014; Fah, Citation2021; Katz & Haldar, Citation2016; Nomchong, Citation2017; Poynton et al., Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2022; Tristan Jepson Memorial Foundation (TMFJ), Citation2015). Cooke (Citation2021) highlights that recent changes in legal aid organisations have meant that lawyers are having to do more administrative work, putting pressure on them to get their legal work done in less time. Managing workloads was considered a primary intervention in the Chan et al. (Citation2014) study where 70% of participants noted that the redistribution of work to other colleagues and being given extra time to complete work was effective at reducing stress levels. The same study emphasised the importance of having control over work.

Another obstacle connected with workload, noted by three participants, was time restraints: ‘We cannot afford to always listen to the backstory’ (Participant 1), ‘it helps if one does have time to be available and then to follow through . . . when time is short it can be tempting to just do things with minimal client input, because that is faster, but that does nothing to empower the client, give them choices in the moment or get them into a position where they can make good choices by themselves in future’ (Participant 4).

One participant mentioned that the limit in funding is a barrier if supervision and social workers are too expensive to be made available to staff (Participant 3). One other participant considered that limited communication resources (non-text based) was also a barrier (Participant 4). The impact of budget constraints is mentioned in the literature (Cooke, Citation2021; James, Citation2020).

Self-care for lawyers

Self-care is frequently recommended in the literature to reduce the risk of vicarious trauma (Burton & Paton, Citation2021; James, Citation2020; Katz & Haldar, Citation2016; Leonard et al., Citation2021; Pirelli at al., 2020) and was one of the recommendations by the High Court in the Kozarov case (2022). There was only one mention of self-care in this study, and the participant called for managers to facilitate self-care in the workplace. Sandra Bloom (Citation2003) has identified a number of different types of self-care, and these included the professional and work settings, both of which require support of managers to put into practice (Participant 3). In a study by Bober and Regehr (Citation2006), participants supported the idea of self-care, but this did not translate into time devoted to practising self-care. It may be helpful for managers promoting self-care to consider what obstacles might exist for their lawyers to practise self-care. Additionally, Kim et al. (Citation2022) warned that when teaching self-care, it needed to address the symptoms of vicarious trauma and not just stress management.

Psychosocial risk assessment

The participants in this study did not refer to the value of doing a risk assessment. However, in the Kozarov case (2022), the High Court recommended that organisations engage in psychosocial risk assessments for hazards. Pirelli et al. (Citation2020) also highlight the importance of identifying potential risk factors. In terms of factors that relate to the individual employee, research has identified the following: prior personal trauma (Leclerc et al., Citation2020; Maguire & Byrne, Citation2017; Vrklevski & Franklin, Citation2008), prior history of mental illness and negative coping strategies (Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Leonard et al., Citation2021; Poynton et al., Citation2018) and certain personality traits (Maguire & Byrne, Citation2017). This paper has already referred to other risk factors in the workplace such as budget restraints, policies, ineffective management and working conditions for staff.

Any workplace assessment would arguably need to look at lawyers working from home (which has increased since the onset of the recent health pandemic; IBA, Citation2021) and how this impacts upon risk to the lawyer or client. Trauma-informed practices may need to be adjusted to this alternative setting to ameliorate risks. In this study one participant wrote, ‘remote work arrangements may remove informal debriefing/supports for frontline workers or reduce the work/life separation’. Nomchong (Citation2017) referred to a presentation by Bradley where she suggested that lawyers working from home should have a designated room for sensitive files to create distance from the material. Working from home is an area that needs further research.

It can also be argued that any assessment needs to recognise the strengths and resilience of the staff (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, Citation2016; Randall & Haskell, Citation2013), which can be considered a protective factor. One example that could be unique to organisations like legal aid is the tendency for employees to be compassionate (Gilbert, Citation2005; James, Citation2020) and have shared values around social justice (Cooke, Citation2021). Whilst these values may be a risk because the lawyers’ work has such a significant impact on people’s lives (Verney, Citation2018), they can also facilitate solidarity and a sense of collectivism when staff work through precarious conditions together (Cooke, Citation2021).

Peer support networks

Whilst none of the participants in this study mentioned the need for strong peer support networks specifically, it may be implied from recommendations like, ‘better office structure to open plan to facilitate regular conversations/debriefing opportunities’ (Participant 3). The need for strong peer support networks is more evident in the research, which identifies that having strong interpersonal relationships inside and outside of work is a protective factor against the impact of trauma (James, Citation2020; Ko & Memon, Citation2022; Leonard et al., Citation2021; Sutton et al., Citation2022). Cooke (Citation2021) adds that these connections improve culture and productivity. The Poynton et al. (Citation2018) study revealed that flexible work practices and family and community services leave (which help facilitate family and other relationships outside of work) were identified as effective by more than 90% of the employees (see also James, Citation2020).

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. Firstly, it had a small sample size of six. Future researchers are encouraged to contact all the Legal Aid Commissions around Australia and other similar organisations in the public legal assistance sector such as community legal centres, refugee legal services, Aboriginal legal services and specialist law pro bono services. The advantage of reaching out to a greater number of services is not just increasing the sample size, but also the diversity of the sample of participants. In this study, the sample was homogeneous, which is helpful when making recommendations specific to legal aid lawyers, but a more diverse sample is likely to identify other recommendations (such as specific suggestions for how to respect the culture of the lawyer or client) that are still relevant to the public legal assistance sector of which legal aid is a part.

Another limitation to this study that bears mentioning is the fact that data collection was limited to the responses a participant could provide in a survey. On two occasions, participants expressed frustration about the limitation of how they were asked to answer the question. In response to what service delivery could look like for clients, one participant wrote, ‘This needs an entire paper, not just a box of text!’ (Participant 4). Furthermore, using a survey meant the researcher was unable to clarify or explore the responses as would have been possible if in-depth interviews had been conducted. Additionally, this project could have benefited from focus groups where participants could be prompted by colleagues to recall and articulate more about what they see as important for trauma-informed practice in their workplace.

Whilst triangulation was used to check the process of analysis, if time permitted, this study would have benefited from adding additional processes such as member checking – sending the findings back to the participants to check that it has accurately reflected their contribution and to give them an opportunity to change or add to their data. Furthermore, the survey only listed eight trauma-informed principles for the participants to reflect upon. This is a limitation to this study, because had they been given a more comprehensive list (as is mentioned in the Summary of Trauma Informed Practice, sent to participants with the survey), participants may have made further recommendations that would add to the findings.

Finally, the authors acknowledge that using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) developed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2019) would have been a better fit for this study than grounded theory. The purpose of this study was not to arrive at a ‘theory’ grounded in the data of participants (nor did we repeatedly interview participants until the result emerged). Instead, themes were identified that gave rise to specific recommendations for trauma-informed practice. RTA is useful for identifying meaningful patterns in qualitative data to form codes and themes, and it is useful for under-researched areas (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). It also has the advantage of recognising when analysis of data is influenced by the researcher’s reflexive perspective (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019), which in this case was her experience as a lawyer in the legal assistance sector.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to gather data from lawyers working in legal aid about what their workplace would look like ideally if it were trauma informed. In response, the participants put forward the following initiatives: adapting the physical environment; staff training in mental health and trauma-informed practice; noticing the impact of trauma on lawyers (screening, check-ins and reflective practice); debriefing and discussion of trauma-informed practice at team meetings; supervision for lawyers; support and leadership from management; cultural change in the workplace; trauma-informed organisation policies and practices; adjustments to service delivery for clients; adjustments in the way legal aid works with third parties; removal of organisational obstacles (excessive workloads that lack diversity, time and budget constraints and inadequate technology); and self-care for lawyers. These recommendations satisfy the aim of the study in that they paint a compelling picture of what a trauma-informed legal aid workplace would look like from their perspective.

Participants provided rich detail when describing some of these initiatives (especially the physical environment and service delivery for clients), which is not found in the literature (M’baku, Citation2021; Niebler, Citation2019; Swanson, Citation2019). This is one of the advantages of using a qualitative design and selecting lawyers who are in a unique position to provide their perspective of what is needed. Additionally, participants were strong about the need to have support from management for their own well-being, but also to enable initiatives to be implemented, and lead by example. It was thought that this was one of the necessary components to changing culture and removing the current stigma around mental illness. This assertion about the importance of the role of management was not as strongly identified in the literature. These insights from the participants are a valuable contribution to research for the legal profession and trauma-informed practice.

Participants did not place the same emphasis on the value of peer support, risk assessments and self-care that can be seen in the literature. James (Citation2020) has highlighted that the legal profession has a poor historical record with practising self-care, and, along with Cooke (Citation2021), he suggested that the nature of the legal profession may be impeding strong peer networks (that it is competitive, there are heavy workloads, staff often work independently rather than collectively, and departments can tend to be siloed). However, the failure to mention these factors could simply have been an oversight from a small sample. Participants did support the cited examples of recommendations provided in the questions (to prompt their response), but these three were not put to the participants, which may explain why they were not mentioned. It is recommended that future research employs methods that provide participants with greater opportunities to reflect upon their experience and thoughts such as focus groups or in-depth interviews.

This study highlights the need for further research and study in a number of directions. As mentioned above, further study with a greater number and diversity of participants in the legal assistance sector to provide more comprehensive data would be helpful. The data provided in this study lay the groundwork for such research. The legal profession would also benefit from the development of a trauma-informed model that is tailored to the profession. It is recommended that such a model take into account the nuanced settings within which lawyers work, such as legal aid. Finally, this paper calls for future researchers to implement such a model (or even the initiatives proposed here) and assess the impact upon the well-being and safety of lawyers and clients.

The participants in this study were evidently passionate about the need to integrate trauma-informed practice into their workplace. The importance of their recommendations becomes more evident when considered in the context of the current mental health crisis in the legal profession, the legal risk of not providing a psychologically safe workplace for staff and the increase in productivity and effectiveness that lawyers could achieve in a trauma-informed workplace (Katz & Haldar, Citation2016; M’baku, Citation2021).

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Clare Pike has declared no conflicts of interest.

Amanda Rebar has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Central Queensland University Human Research Ethics Committee (4 November 2022, Application Reference: 2022-075), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Amanda Rebar for her patience, and expedient feedback and advice on my drafts. I also want to acknowledge Sarah Campbell, Jane Green and Liz Dunlop who are also passionate about the legal profession being trauma informed for clients and lawyers – thank you all for your encouragement and support. I am grateful for all the work people like Colin James have done to highlight the issues of stress and trauma for lawyers. Finally, I extend my thanks to the Legal Aid Commissions who invited their staff to participate in this study. We need more brave souls in our profession to embark upon research projects that can contribute to improvements in service for our clients and working conditions for our staff.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Beaton Consulting for Beyond Blue. (2007). Annual professions survey, research summary. Beyond Blue.

- Beaton Consulting for Beyond Blue. (2011). Annual professions survey- research summary. Beyond Blue.

- Bergin, A. J., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2014). Australian lawyer well-being: workplace demands, resources and the impact of time-billing targets. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 21(3), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2013.822783

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: a practical guide. (2nd Edition) . Sage Publications.

- Bloom, S. L., & Sreedhar, S. Y. (2008). The sanctuary model of trauma-informed organisational change. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 17(3), 48–53.

- Bloom, S. L. (2003). Caring for the caregiver: Avoiding and treating vicarious traumatization in sexual. In E. Giardino, E. Datner, & J. Asher (Eds.), Sexual assault across the lifespan- a clinical guide (pp. 459–470). GW Medical Publishing.

- Bober, T., & Regehr, C. (2006). Strategies for reducing secondary or vicarious trauma: Do they work? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhj001

- Bride, B. E., Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35(3), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0091-7

- Burton, K., & Paton, A. (2021). Vicarious trauma: Strategies for legal practice and law schools. Alternative Law Journal, 46(2), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X21999850

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Chan, J., Poynton, S., & Bruce, J. (2014). Lawyering stress and work culture: An Australian study. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 37, 1062.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory. In Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 81–110) Sage Publications, Inc.

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

- Cooke, E. (2021). The working culture of Legal Aid Lawyers: Developing a ‘Shared Orientation Model’. Social & Legal Studies, 31(5), 704–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639211060809

- Covington, S. S. (2016). Becoming trauma informed: Tool kit for women’s community service providers. Center for Gender and Justice.

- Fah, E. (2021). Wellbeing and resilience: Perfectionism, excessive workloads and lack of senior support: Survey reveals mental health and wellbeing challenges for SA lawyers. Bulletin (Law Society of South Australia), 43(7), 22–23. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.213528183055290

- Field, R., Duffy, J., & James, C. (Eds.) (2016). Promoting law student and lawyer well-being in Australia and beyond. Emerging Legal Education Series. Routledge.

- Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion and cruelty: A biopsychosocial approach. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9–74). Routledge.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One, 15(5), e023076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.023076

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001a). Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 89(89), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23320018903

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001b). Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey-Bass.

- Hodge, S. D., & Williams, L. (2021). Vicarious trauma: A growing problem among legal professionals (pp. 60–64). The Practical Lawyer.

- Homes, A., & Grandison, G. (2021). Trauma-informed practice: A toolkit for Scotland. NHS, Scottish Government.

- Howieson, J. (2011). The professional culture of Australian family lawyers: Pathways to constructive change. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 25(1), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebq017

- International Bar Association (IBA). (2021, October). Mental wellbeing in the legal profession: A global study. https://www.ibanet.org/document?id=IBA-report-Mental-Wellbeing-in-the-Legal-Profession-A-Global-Study

- Iversen, S., & Robertson, N. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of secondary trauma in the legal profession: A systematic review. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 28(6), 802–822. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1855270

- James, C. (2020). Towards trauma-informed legal practice: A review. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(2), 275–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1719377

- Katz, S., & Haldar, D. (2016). The pedagogy of trauma-informed lawyering. Clinical Law Review, 22(2), 359–393.

- Kelk, N. (2009). Courting the blues: Attitudes towards depression in Australian law students and legal practitioners. Brain & Mind Research Institute, University of Sydney.

- Kezelman, C. A., Stavropoulos, P. (2016). Trauma and the Law: Applying Trauma-Informed Practice to legal and judicial contexts. Blue Knot Foundation. https://professionals.blueknot.org.au/resources/publications/trauma-and-the-law/

- Kim, J., Chesworth, B., Franchino-Olsen, H., & Macy, R. J. (2022). A scoping review of vicarious trauma interventions for service providers working with people who have experienced traumatic events. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 23(5), 1437–1460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021991310

- Ko, H., & Memon, A. (2022). Secondary traumatization in criminal justice professions: A literature review. Psychology, Crime & Law, 29(4), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.2018444

- Kozarov v Victoria. (2022). 273 CLR 115.

- Leclerc, M. E., Wemmers, J. A., & Brunet, A. (2020). The unseen cost of justice: Posttraumatic stress symptoms in Canadian lawyers. Psychology, Crime & Law, 26(1), 1–21. 2019.1611830 https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X

- Leonard, M.-J., Vasiliadis, H.-M., Leclerc, M.-È., & Brunet, A. (2021). Traumatic stress in Canadian lawyers: A longitudinal study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 15(Suppl 2), S259–S267. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001177

- Levin, A. P., Albert, L., Besser, A., Smith, D., Zelenski, A., Rosenkranz, S., & Neria, Y. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress in attorneys and their administrative support staff working with trauma-exposed clients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(12), 946–955. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182392c26

- Levin, A., & Greisberg, S. (2003). Vicarious trauma in attorneys. Pace Law Review, 24(1), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.58948/2331-3528.1189

- Maguire, G., & Byrne, M. K. (2017). The law is not as blind as it seems: Relative rates of vicarious trauma among lawyers and mental health professionals. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1220037

- Manian, N., Rog, D. J., Lieberman, L., & Kerr, E. M. (2021). The organizational trauma-informed practices tool (O-TIPs): Development and preliminary validation. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1), 515–540.https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22628

- Miller, N. A., & Najavits, L. M. (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246

- M’baku, V. (2021). Trauma-informed lawyering. National Centre on Law & Elder Rights.

- McCann, L., & Pearlman, L., A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140

- McKenna, N. C., & Holtfreter, K. (2021). Trauma-Informed Courts: A review and integration of justice perspectives and gender responsiveness. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 30(4), 450–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2020.1747128

- Niebler, R. (2019). The cost of bearing witness: Vicarious trauma in the legal profession. Proctor, 39(10), 18.

- Nomchong, K. (2017). Vicarious trauma in the legal profession. The Journal of the Nsw Bar Association, Summer, 79, 35–36.

- Pirelli, G., Formon, D. L., & Maloney, K. (2020). Preventing vicarious trauma (VT), compassion fatigue (CF), and burnout (BO) in forensic mental health: Forensic psychology as exemplar. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(5), 454–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000293

- Piwowarczyk, L., Ignatius, S., Crosby, S., Grodin, M., Heerenm, T., & Sharma, A. (2009). Secondary trauma in asylum lawyers. Benders Immigration Bulletin, 14(5), 1–9.

- Poynton, S., Chan, J., Vogt, M., Grunseit, A., & Bruce, J. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of wellbeing initiatives for lawyers and support staff. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 41(2), 584–619. https://doi.org/10.53637/AVJM9953

- Randall, M., & Haskell, L. (2013). Trauma-informed approaches to law: Why restorative justice must understand trauma and psychological coping. The Dalhousie Law Journal 36(2), 501–533.

- Rønning, L., Blumberg, J., & Dammeyer, J. (2020). Vicarious traumatisation in lawyers working with traumatised asylum seekers: A pilot study. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(4), 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2020.1742238

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014, July). Concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Sue, D. W., Bernier, J. E., Durran, A., Feinberg, L., Pedersen, P., Smith, E. J., & Vasquez-Nuttall, E. (1982). Position paper: Cross-cultural counselling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000082102008

- Sutton, L., Rowe, S., Hammerton, G., & Billings, J. (2022). The contribution of organisational factors to vicarious trauma in mental health professionals: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2022278–2022278. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.2022278

- Swanson, K. (2019). Providing trauma-informed legal services. Los Angeles Lawyer, 42(2), 15–15.

- Thirkle, S. A., Kennedy, A., & Sice, P. (2021). Instruments for exploring trauma-informed care. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 44(1), 30–44. 2021, Vol

- Tie, C. Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

- Tristan Jepson Memorial Foundation (TMFJ). (2015). Workplace wellbeing: best practice guidelines for legal profession. https://www.publicdefenders.nsw.gov.au/Documents/TJMFMentalHealthGuidelines_A4_140427.pdf

- Verney, A. (2018). Lessons on vicarious trauma and wellbeing from a Royal Commission. Law Society Journal, 41, 26–27.

- Vlahos, D. (2021). Practice: Workplace health and safety: Call to action on wellbeing at work. Law Institute Journal, 95(8), 69. https://doi.org/10.3316/agispt.2021082705245

- Vrklevski, L. P., & Franklin, J. (2008). Vicarious trauma: The impact on solicitors of exposure to traumatic material. Traumatology, 14(1), 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765607309961

Appendix A.

Summary of trauma-informed practice

Appendix B.

Survey questions (and information and informed consent form)