ABSTRACT

When, how, and which disciplines started to deal with which forms and aspects of LGBT+ parenthood is not a coincidence but is linked to occasions of discussion as well as to visibility, acceptance, and recognition in the wider social and political contexts. This particularly applies to sociological contributions which look at families and parenting involving relations to social institutions and their impact and shaping of forms, challenges, and meanings of parenting and family life. In Italy, issues about LGBT+ parenting began to appear in the sociological literature some thirty years ago. Since then, the debate has seen different waves and shifts, which show both how external movements, occasions, and discussions influenced the sociological debate and how the latter has, in turn, contributed to the construction and recognition of the phenomenon. Against this background, using a data mining approach, the article presents an analysis of the most recent sociological literature on LGBT+ parenting, highlighting the main dimensions of the debate and outlining expressions, concepts, and words most used on this topic. Using Italian sociology as an example, the critical analysis of these findings shows how issues of topicality and (in)visibility are both reflected and reiterated by contextual sociological discourses and debates.

Introduction: families under the sociological lens

The study of families and kinship relations is an interdisciplinary and dynamically developing field, which relates to the various forms and processes of forming, being, and doing families over time and in different cultural and societal contexts. Among the various disciplinary perspectives, it is the sociological perspective that looks at the social significance of family as a social institution and examines how family models and family relationships are influenced by and related to social values and structures and how they change in the light of wider sociocultural and sociostructural contexts and developments (Starbuck & Lundy, Citation2016; Treas et al., Citation2017). A sociology of families looks at intimacies, kinship relations and forms of family lives, parenting practices and values, the changing nature of childhood, parenthood, intragenerational and care responsibilities, divisions of labour, and reproductive decisions and practices with respect to changing gender relations and within the framework of wider societal developments (Chambers, Citation2012; Naldini & Saraceno, Citation2013; Satta et al., Citation2020). What is of particular concern under a sociological lens is how ideas, values, approaches, and concerns (for instance anxieties and rhetorics of ‘family decline’) impact defining, displaying, and studying families (Chambers, Citation2012). Accordingly, it is important to see a sociology of families within the wider frames of visibility, acceptance, and recognition in social and political contexts to understand how the sociological debate has developed over time and which families it has considered, as well as when and how (Chambers, Citation2012; Naldini & Saraceno, Citation2013; Starbuck & Lundy, Citation2016).

Italian sociology has for a long time mainly focused on the dominant family model made up of heterosexual spouses living with children, compatible with the capitalist way of Fordist production and the traditional gendered and social division of labour (Naldini & Saraceno, Citation2013; Zanatta, Citation2011). Since the late sixties of the last century, however, the questioning of life and family models with their phases and rites of passage, that until then seemed almost prescriptive or even ‘natural,’ has fundamentally changed discourses and directions of family research in the social sciences. There has been a gradual transition from the static idea of ‘having a family’ to more dynamic concepts of ‘making a family’ in which the logic of belonging to an identity has been replaced by processes of negotiation, while compliance with given rules and duties has given way to the idea of taking care and assuming responsibilities (Chambers, Citation2012; Naldini & Saraceno, Citation2013; Treas et al., Citation2017). Family and its depictions have moved from a standardized traditional model to more plural family models regarding family composition as well as roles, relationships, and practices of ‘doing family’ (Jurczyk, Citation2014; Morgan, Citation2011; Saraceno, Citation2008; Satta et al., Citation2020). In this context, Italian sociology has also progressively shifted its focus to the plural and dynamic character of intimate ties and practices of caring as the crucial elements of doing family (Barbagli, Citation1984, Citation1990, Citation2004; Barbagli & Saraceno, Citation1997, Citation2002; Bimbi & Trifiletti, Citation2000; Naldini & Saraceno, Citation2013; Ruspini, Citation2012; Ruspini & Luciani, Citation2010; Saraceno, Citation2017; Satta et al., Citation2020).

When it comes to families involving LGBT+ parents, both the evolution of the sociological literature and the impact of this scholarship have only recently become the subject of scientific analysis and reconstruction (Chambers, Citation2012). This is particularly evident in the Italian literature which started to consider families involving LGBT+ parents only some thirty years ago (Trappolin, Citation2016; Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2015). As Trappolin pointed out for the case of Italy, there has been quite a rapid shift from the mere awareness of the existence of such families to their inclusion in the debate on families and parenthood and, eventually, to their becoming the object of specific attention within the sociological literature (Trappolin, Citation2016).

Against this background, this article aims to illustrate how LGBT+ parenting has been under the lens of Italian sociology by reconstructing and contextualizing the development of the debate. The article especially focuses on the most recent Italian sociological literature, presenting the findings of a content analysis of sociological articles and publications produced between 2013 and 2019. During this period, sociology in Italy showed a renewed interest in LGBT+ parenting due to specific events which also led to a wider public debate on the topic. Based on a data mining method, which allows for the extraction of information from a textual corpus, the findings highlight the main dimensions of the current sociological debate on LGBT+ parenting and the vocabulary most frequently used to discuss issues of LGBT+ parenting. Beyond illustrating the national debate, the critical analysis and contextualization of these findings show how issues of topicality and (in)visibility are both reflected and reiterated by the development and the choices of contextual sociological agendas and discourses.

Families involving LGBT+ parents: taking stock of and reviewing debates

Research on families involving LGBT+ parents as an interdisciplinary field has grown exponentially and widely progressed both within and across different disciplines and research strands (Goldberg & Allen, Citation2020). Various contributions have traced the development of the research field taking stock of and reviewing the debates at different points in time (Biblarz & Savci, Citation2010; Farr et al., Citation2017; Fitzgerald, Citation1999; Goldberg & Gartrell, Citation2014; Lytle, Citation2019; Patterson, Citation2000, Citation2006; Reczek, Citation2020; Trappolin, Citation2016; van Eeden-Moorefield et al., Citation2018). Having their origins mainly in the field of family psychology, research areas and debates have progressively extended from parent–child relationships and challenges and the effects of LGBT+ parenting to wider questions of family formation and recognition by social institutions and within legal, policy, and practice frameworks (Goldberg & Allen, Citation2020).

Research on LGBT+ parenting was initially developed mostly in the psychological and psychoanalytic field (Field, Citation2002; Gross, Citation2003; Scallen, Citation1982; Tasker & Golombok, Citation1997) to satisfy two major aims, namely analyzing the parental suitability of LGBT+ parents, and the emotional, psychosocial, and behavioural adaptation of their children. As with sociology, interest in LGBT+ parenting within the scientific debate has been more recent and has remained rather marginal in studies of family transformation before the turn of the century (Allen & Demo, Citation1995; Trappolin, Citation2016). First research from a more sociological perspective appeared in the late 1970s and early 1980s and focused mainly on trajectories and experiences of lesbian mothers and gay fathers who had divorced from heterosexual marriages, with a particular focus on their struggles to gain custody and on social conflicts arising from being homosexual and holding a parenting role (Beck, Citation1983; Bozett, Citation1981; Miller, Citation1978). Only during the 1990s did the debate turn to questions of planned parenthood of same sex-couples (Trappolin, Citation2016). Due to the driving force of associations, international sociological research also began to consider issues more properly related to family and parenting rights of lesbian and gay couples focusing on legal recognition and protection of couples and parental relationships outside of marriage (Ainslie & Feltey, Citation1991; Plummer, Citation1992). With the new millennium ahead, the focus had again shifted to new themes, such as reproductive practices and parental relationship arrangements, with specific attention toward different paths that could lead to parenting (Hicks, Citation2011) such as surrogacy (Stacey, Citation2004), foster care and adoption (Mallon, Citation2004), artificial insemination, and other medically assisted reproduction techniques (Dunne, Citation2000; Ryan-Flood, Citation2009; Sullivan, Citation2004). Recently, international sociology has also paid attention to transgender parenting (Fortier, Citation2015; Gross, Citation2015; Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2019; Hines, Citation2007; Ruspini, Citation2010), deepening its understanding of, among other issues, fertility preservation and the realization of parenthood despite gender transitions (De Sutter et al., Citation2002; Hérault, Citation2014; Poure, Citation2013).

Different reviews have pointed out the evolution and shifts of the debates as well as under-researched and neglected areas concerning less visible parents and parenting practices, intersectionalities, and new normativities (Biblarz & Savci, Citation2010; Reczek, Citation2020; Trappolin, Citation2016; van Eeden-Moorefield et al., Citation2018). They have highlighted thematic and methodological issues and developments but also discussed the inclusiveness of the debate, its often defensive approach (Lytle, Citation2019), and its role in constructing, making visible, or neglecting different families involving LGBT+ parents (Biblarz & Savci, Citation2010; Reczek, Citation2020; Trappolin, Citation2016; van Eeden-Moorefield et al., Citation2018).

In their seminal review published in 2010, Biblarz and Savci pointed out the major advances in LGBT family studies over the preceding decade highlighting (a) the move beyond an overly unified picture of white middle-class lesbian motherhood towards the exploration of the substantial diversity of families involving LGBT parents, (b) the unpacking of diverse pathways of planned gay fatherhood and gay male family formation, (c) an upcoming discussion on bisexual, transgender, and sexually fluid parents, (d) ongoing research on all dimensions of children's adjustment and achievement resulting in the conclusion that children raised by lesbian couples do as well or even better than those raised by heterosexual couples, and (e) a diminishing timidity to cover more controversial issues such as differences, inequalities, conflicts, and violence due to – as the authors assume – the fact that ‘an interest in research that could serve the community began to outweigh worrying too much about what anti-gay advocates might latch onto from the literature’ (Biblarz & Savci, Citation2010, p. 492). As to future research, the authors underlined the need to conduct more specific studies on families involving bisexual and transgender people over the life course, as well as more sexually fluid parents, families involving LGBT+ people of colour and those across the socioeconomic spectrum (to better focus on specific social locations and intersectionalities), and differences in parent–child relationships and children's adjustments and development. What is particularly interesting in the context of this article is the authors’ recommendation to better consider the broader symbolic and institutional aspects of family, kinship, parenting, and childhood and the sociopolitical and historical context in which research on different families is taking place.

Similar conclusions were drawn by van Eeden-Moorefield et al. (Citation2018) in their content analysis of LGBT research published in high-ranking general family journals between 2000 and 2015. Analyzing theoretical foundations, methodologies, and the inclusiveness of contributions, these authors highlight the marginal coverage of LGBT-related issues in top-ranking journals, the atheoretical character and purposive cross-sectional sampling in many studies, and the dominant focus on lesbian and/or gay couples including primarily white and middle-class individuals. Similarly, Farr et al. (Citation2017) pointed out the lacking theoretical grounding of many contributions characterized by a predominantly applied focus on addressing public debates on sexual minority parent families. Pointing out directions for further research, Goldberg and Gartrell (Citation2014) suggested including how race, ethnicity, social class, and geographic factors shape the experiences of LGB-parent families.

A recent review by Reczek (Citation2020) of contributions from 2010 to 2020 highlighted three main gaps in the last decade's research, namely (a) a predominant focus on gay, lesbian, and same-sex parent families (and to a lesser extent bisexual and transgender parenthood) and a lack of attention to the diverse family ties of single sexual and gender minority people as well as to intersex, asexual, queer, gender non-binary/non-conforming, polyamorous, and other sexual and gender minority families, (b) an ongoing emphasis on white, socioeconomically advantaged sexual and gender minority people and the failure to account for racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity, and (c) a lack of integration of sexual and gender minority experiences across the life course (Reczek, Citation2020).

Focusing specifically on sociological contributions, Moore and Stambolis-Ruhstorfer (Citation2013) delineated four main topics that had dominated the sociological research on families involving LGBT parents. The topics included (a) who counts as family and whether and how changing definitions of family incorporate LGBT people, (b) how lesbian women and gay men come to be parents, focusing on biological, social, and legal obstacles to family formation, (c) outcomes for children and youth raised by openly gay parents, and (d) family dynamics including relationship quality, dissolution, and custody in same-sex and transgender parenting, as well as aspects of facing stigma and legal obstacles as barriers to full recognition as families. Regarding directions of future research, these authors underlined the need to produce high-quality data on LGBT parents and their children. Given increasing legal recognition in many contexts, the authors also invited investigation into the warnings that marriage equality for lesbians and gay men might eventually result in new exclusions of those who fall outside of new normativities and to learn more, generally, about the effects of ongoing legal changes also in terms of inequalities and well-being among families across the lines of race, class, gender, and sexual identity. Furthermore, to foster and better integrate research within the field, the authors recommended ongoing analyses of the link between research and policies for LGBT-parent families. According to the authors, ‘sociology can make a unique contribution to this question by examining how research on lesbian and gay families is funded, institutionalized, conducted, and used in the policy sphere’ (Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, Citation2013, p. 503). Finally, the authors stressed that more attention, including theoretical effort, needed to be paid to families standing on the margins and outside the couple norm in order to ‘push forward a rich research agenda that avoids taking the meanings of family for granted’ (Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, Citation2013, p. 503).

Trappolin (Citation2016) provided an analysis of the construction of lesbian and gay parenthood in sociological research, examining how forms of parenthood under the lens of qualitative social research conducted in the US and the UK had changed over time, which issues had been addressed, and which sampling and methodological choices had been made. The strength of this review is its critical analysis of how sociological investigation had constructed and highlighted parenthood experiences of lesbian mothers and gay fathers as its object of study, both lending relevance to political motives outside the field and to research questions inside it. The author traced the path to the current predominant focus on same-sex couples with children and its connection to questions of social change and conflict triggered by lesbian and gay communities, thereby addressing the difficult topic of how movements and communities induce researchers to study issues on their agenda and what effects research, in turn, has on these communities. In this context, the author stated that

the fight for recognition induces gay and lesbian communities to represent themselves as a cohesive whole centered on a specific aspect of identity – sexuality – regardless of all internal distinctions. Sexual orientation thus defines the boundaries of a quasi-ethnic dimension that distinguishes individuals and collectivities. Studies on same-sex families with children observe how the reference communities evolve through the family demands they express. But we should also reflect (as we propose to do with our analysis) on how these same studies reinforce the assumption of a self-defining identity – the homosexual one – that is adopted for contrasting the exclusion suffered by lesbian and gay people. From this perspective, the history of the social forms of homosexual parenthood written by research is part of the history of the polarization between homosexuality and heterosexuality. (Trappolin, Citation2016, p. 55)

Contextualizing Italian sociological contributions on LGBT+ parenting

Accordingly, the Italian scientific debate on LGBT+ parenting, especially within the field of sociology, must also be seen in its specific context. In recent years, Italy has seen issues of sexual politics at the forefront of political and societal debates (Franchi & Selmi, Citation2020). While there has been an increasing pluralization of arrangements of intimacies and family lives, as well as growing visibility of LGBT+-related questions including LGBT+ parenting issues and further processes of de-traditionalization of gendered relations, Italy has simultaneously been witnessing a strong heterosexist backlash with conservative Catholic organizations and right-wing populist parties taking large space and attention in public debates (Franchi & Selmi, Citation2020; Scandurra et al., Citation2020). They argue that the recognition of same-sex couples and, in particular, their parenting rights is a threat against a ‘natural order’ (Garbagnoli, Citation2014) or the ‘natural family’ (Lasio & Serri, Citation2017), reaffirming heterosexuality as the prerequisite to good parenting. At the core of these groups’ protests stands, more broadly, an attack on what they term as ‘the ideology of gender,’ referring to any feminist and LGBT+ claims ranging from anti-discrimination education and legislation to gender equality and reproductive and parenting rights (Garbagnoli & Prearo, Citation2018; Selmi, Citation2015). The attention these positions have received in public debate shows how determinist understandings of gender, sexuality, and family and the primacy of heterosexuality as the premise for full citizenship rights can still find consensus in public opinion and politics (Corbisiero & Monaco, Citation2020).

These positions have received a boost in the context of the reopening of a parliamentary debate on the legal recognition of same-sex partnerships. After various unsuccessful attempts, there has been a new effort since 2013 to relaunch the discussion on the issue and to discuss a bill aimed to legally recognize same-sex couples. In May 2016, the bill was approved and finally became law. While defined by some as a milestone in the legal recognition of same-sex couples in Italy, for others it is a watered-down recognition of rights (Mancina & Vassallo, Citation2016). A central point of contention in the political debate has been the legal recognition of parenting rights. In its original version, the bill had included so-called stepchild adoption, granting the right to adopt the children of one's partner to partners of same-sex couples legally recognized under the new law. Eventually, this clause was stripped to get a solid majority for the approval of the law. During the months that preceded the approval, LGBT+ parenting rights came to the forefront of a broad political and societal debate and received new attention within the scientific debate as well.

Italian local and regional governments have likewise been involved in implementing anti-discriminatory practices in opposition to the protest and actions of a conservative part of Italian society (Corbisiero & Monaco, Citation2017; Franchi & Selmi, Citation2020), playing a crucial role in the battle for the recognition of parenting rights. The mayors of many cities are now transcribing the birth certificates of children born abroad to same-sex parents and re-issuing the birth certificates of children born in Italy from same-sex couples, adding the name of the parent without biological bonds with the child. Together with a series of rulings on parenting rights issued by several courts, local authorities are playing a key role in filling the equality gap between heterosexual and LGBT+ parents and their families (Franchi & Selmi, Citation2020).

Concerning Italian research on LGBT+ parenting, the most visible contributions internationally have undoubtedly come from the field of psychology. During the last decade, there has been extensive scientific production by some Italian scholars and study groups on topics like attitudes towards gay and lesbian parenting (Baiocco et al., Citation2013, Citation2020), gay men and lesbian women who became parents in former heterosexual relationships (Giunti & Fioravanti, Citation2017), sexual orientation and desires and intentions to become parents (Baiocco & Laghi, Citation2013), family functioning, dyadic satisfaction, child well-being in lesbian mother and gay father families (Baiocco et al., Citation2015), child health outcomes and parental dimensions in same-sex and different-sex parent families (Baiocco et al., Citation2018), narratives of lesbian mothers (Zamperini et al., Citation2016), co-parenting (Carone et al., Citation2017), donation of gametes and surrogacy (Carone, Citation2016), gay father surrogacy families (Carone et al., Citation2018), and child attachment security in gay father surrogacy families (Carone et al., Citation2020).

With some exceptions, the Italian sociological debate has long been largely disinterested in LGBT+ parenting and related issues. However, as in the debate in other contexts, it is possible to trace different waves or generations of the few sociological studies on lesbian and gay parents since the 1990s (Monaco & Nothdurfter, Citation2020; Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2019).

The first generation of research appeared as references in the wider context of research on gay and lesbian communities in Italy and consisted of a series of studies referring mainly to lesbian mothers – and, to a lesser extent, to gay fathers – who became parents during previous heterosexual relationships (Barbagli & Colombo, Citation2001; Bertone et al., Citation2003; Bonaccorso, Citation1994; Danna, Citation1998; ISPES, Citation1991). Studies of this generation first discovered that these parents existed and subsequently started only timidly and little by little to establish lesbian and gay parenthood as a research topic (Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2019).

It has been, in fact, only with the turn of the new millennium that LGBT+ parenthood and LGBT+ parenting issues have gained their own autonomy in the Italian sociological debate and that more specific research has been carried out. An important catalyst for this shift and the following second generation of studies was the foundation of Famiglie Arcobaleno (Rainbow Families), the first association of gay and lesbian parents, in 2005, which aimed to make parenthood and family life as a planned project and reality of same-sex couples and their children more visible. Accordingly, the attention of this second generation of studies shifted to these ‘gaie famiglie’ (‘gay families’), as defined by Bottino and Danna (Citation2005), analyzing first their different paths to parenthood but increasingly also their daily lives, parenting experiences, and strategies of care (Bertone, Citation2009; Cavina & Danna, Citation2009; Lelleri et al., Citation2008; Sonego et al., Citation2005).

Finally, the relaunching of the parliamentary discussion about the legal recognition of same-sex partnerships in 2013 brought the issue of LGBT+ parenthood and parenting rights to the centre of the Italian public debate, giving rise to a renewed sociological interest in families involving LGBT+ parents. This has led to the publication of several contributions by Italian sociologists, which together constitute what could be called the third generation of sociological studies on LGBT+ parenting in Italy.

Exploring the third generation through data mining

The following paragraph presents the findings of an analysis of the most recent Italian sociological literature published between 2013 and 2019. Although LGBT+ parenting is, as already described, an interdisciplinary and dynamically evolving field of study, the analysis is focused on sociological contributions to LGBT+ parenting research to map the debate within Italian sociology. Despite the more national character and reach of the Italian sociological debate on these issues, it is mostly within this debate that social and political questions of visibility and recognition are reflected and discussed. The analysis included chapters of both edited books and monographs (41) and articles (36) in both national and international journals written by Italian sociologists or research teams in which at least one sociologist was present (see ). Only contributions with their main focus on different forms and topics of LGBT+ parenting were included.

Table 1. Analyzed corpus.

The selected articles and book chapters were analyzed by a data mining approach using T-Lab (Lancia, Citation2012), a textual data analysis software. Data mining as a technique of analysis eliminates the redundancy of information, reducing the dimensionality of the data included in the textual corpus (Assefa & Rorissa, Citation2013; Krippendorff, Citation2004; Waltman et al., Citation2010). The result of the analysis is a sort of compromise between statistical synthesis and hermeneutic analysis of the text since the automated approach allows significant text and themes to emerge and to be represented graphically in a system of Cartesian axes, which are, in a subsequent phase, subject to qualitative interpretation (Lancia, Citation2004; Nigris, Citation2003; Tuzzi, Citation2003).

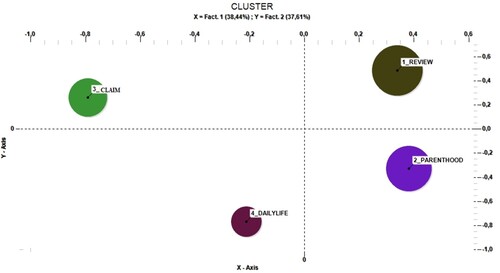

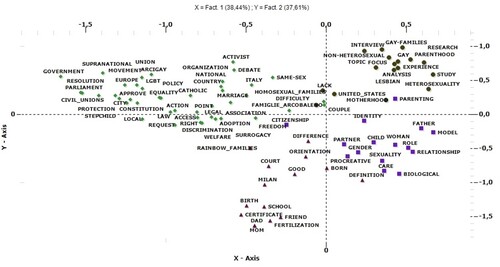

For this study, before proceeding with the analysis of the collected textual corpus, it was subject to an automated normalization. The software standardized the words contained in the text, placing all the nouns in the singular form, all the verbs in the infinitive, and grouping words with the same root into semantic families. Furthermore, so-called empty words (indefinite adjectives, articles, adverbs, exclamations, interjections, prepositions, pronouns, auxiliary and modal verbs) were excluded from the analysis. A thematic analysis of the elementary contexts was then carried out on the normalized text. The result is a mapping of the isotopies – the macro-themes in the various publications (Raister et al., Citation2002) – characterized by the co-occurrence of semantic features. In other words, the contents of the textual corpus were projected on a factorial level and grouped in significant clusters. This way, the analysis of third-generation sociological contributions regarding LGBT+ parenting has made it possible to identify, based on the first two main factors that explain 76% of the overall variability, four clusters (see ). As can be seen in , each cluster has a different weight in percentage terms, since they contain different numbers of elementary contexts.

Table 2. Percentage distribution of elementary contexts in the 4 clusters.

Each cluster summarizes a core theme and consists of a relatively homogeneous set of text fragments, described through the most frequent words (with the highest Chi-square values) (see ).

Proceeding with the semantic analysis, cluster 1 (REVIEW), which contains the highest percentage of elementary contexts corresponding to syntagmatic units (31.42%), is made up of contributions that review what has already been produced and published on the topic, both internationally and in Italy, offering an analysis of the existing literature and review articles (Bertocchi & Guizzardi, Citation2017; Bertone, Citation2015; Danna, Citation2018; Monaco, Citation2017; Trappolin, Citation2016, Citation2017). The most frequent words that characterize this thematic core mostly refer to the field of social research, such as ‘interview,’ ‘research,’ ‘study,’ ‘experience,’ ‘topic,’ and ‘focus.’ The prominence of this cluster refers to an important stocktaking and review of existing literature in the context of the Italian sociological debate.

The vocabulary used, however, reveals some linguistic inaccuracies or even misuses of certain terms in these texts. The word analysis of the first cluster shows that various scientific texts speak about LGBT+ parenting in oppositional terms, so it is not unusual that families involving LGBT+ parents are referred to using the expression ‘non-heterosexual families.’ This approach would somehow legitimize the idea that the reference parameter would be the family with partners of the opposite sex, and all other analyses must start from this consideration. At the same time, this improper expression somehow implicitly proposes a high degree of generalization as if parents who are not heterosexual could be studied as a whole risking to cancel or to minimize different identities – which instead exist and must be claimed and deepened – between gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people and their way of becoming parents and conceiving and living their parental roles.

Other improper expressions frequently used in the reviewed literature are ‘LGBT families’ and ‘homosexual families.’ The use of these expressions is unsuitable as homosexuality is attributed to the family and no longer refers to the individual, as it should. As Saraceno (Citation2012) pointed out, the term ‘homosexual family’ (like ‘heterosexual family’) evokes a closed and somehow normative model, in which all the family components are assimilated with each other even in the most intimate dimension of sexual orientation.

The second cluster (PARENTHOOD), which includes 27.74% of elementary contexts, concerns paths leading to parenthood and issues related to parental identity and its redefinition (Danna, Citation2015; Grilli, Citation2019; Parisi, Citation2018; Ruspini, Citation2015; Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2015). The most frequently used terms highlighted by data mining are ‘identity,’ ‘gender,’ ‘care,’ ‘procreation,’ ‘sexuality,’ ‘biologic,’ ‘role,’ and ‘model.’ The text analysis indicates that the most recent literature on parenting promotes the idea that becoming parents today is part of a wider process of interaction amongst individuals who are not necessarily biologically related to the child but are involved in a shared parenting experience.

It should also be noted that the recent literature on LGBT+ parenting is increasingly giving new meaning to traditional words. In some of the analyzed contributions, for example, the term ‘parents’ is used not only for those biologically related and/or legally recognized as such, but also for other actors who by choice assume parental functions, or who are identified as parents by children who are – biologically and legally speaking – not their own. Likewise, talking about ‘mothers’ and ‘fathers’ in the context of families involving same-sex partners gives these titles an unprecedented meaning, socializing readers with the idea that there may be more than one mom or dad within the same family or that one of these two figures may be missing, in what is nonetheless considered a family in all aspects.

The thematic core of the third cluster (CLAIM), which contains 23.27% of the elementary contexts, focuses on claiming both legal and social recognition of LGBT+ parenting. The most frequent words in this cluster refer to civil unions, policies, recommendations from the European Union, and initiatives and laws implemented in other national contexts to promote full integration and citizenship to all citizens regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity (Bosisio & Ronfani, Citation2015; Corbisiero, Citation2014; Corbisiero & Monaco, Citation2013, Citation2014; Corbisiero & Ruspini, Citation2015; Monaco, Citation2016; Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2015). These contributions also give voice to LGBT+ parents who make their stories and claims visible to change both legal and social recognition of their parental roles and responsibilities. These contributions point out what is best summarized with the concept of ‘living law,’ highlighting that rules are never only abstract but concretized in daily life. Texts within this cluster illustrate gaps and mismatches between parents’ needs and expectations while also portraying mechanisms and possibilities of legal recognition. This kind of literature also documents different actions by LGBT+ parents and their associations such as advocacy, legal actions, and appeals to the courts to change the legal framework even without direct legislative intervention. In this context, the sociological literature also points out the role of families taking to the streets and displaying themselves as families to make their claims visible and heard.

Within this cluster, the analysis shows some critical aspects as well. First, the words (not) used indicate the under-representation of some identities and groups. Recent Italian sociological literature seems to have dealt rather exclusively with same-sex couples who decided to become parents after the couple was formed. Gay and lesbian people who became parents in previous heterosexual relationships, the subjects the first generation of sociological literature was concentrated on, are now almost absent. Similarly, other identities subsumed under the acronym LGBT+ are rather invisible and not considered in the literature. The debate does not cover narratives of single, bisexual, or transgender parents and their claims for recognition and protection of parenting rights. They are already excluded from public discourse and, as this analysis shows, do not find space even within the most recent sociological literature. Although less common, they deserve better insights since their identities entail and present specific challenges on which sociological reflections are completely lacking. However, the successful advocacy of the association Famiglie Arcobaleno and the media exposure of its members have favoured a kind of improper overlap in the collective imagination between LGBT+ parenting and the same-sex couple family of first constitution.

Finally, the fourth cluster (DAILY LIFE), which includes 17.82% of the elementary contexts, presents characteristic words that refer to the everyday life of LGBT+ parents and their children. There are studies on the work–family balance of same-sex parents, their discrimination in taking advantage of leave policies and benefits linked to marriage (Marotta & Monaco, Citation2016), lesbian mothers’ relationships with public institutions and services (Corbisiero & Monaco, Citation2017), children's representations of their family and external influences to family life (Bosisio & Ronfani, Citation2016), and parents’ strategies to include their parenting experiences in different contexts of their social life, such as their families of origin or in the context of childcare services (Trappolin & Tiano, Citation2019).

Studies in this cluster also confirm that Italian sociology has taken up the concept of doing family, understanding families as contexts of the practices of caring and taking responsibility (Gabb, Citation2008; Gabb et al., Citation2019; Hicks, Citation2011; Morgan, Citation2011). In this view, the sense of family is not given by the shape it takes, but by what people do, the meaning attributed to practices, and the ways roles are redefined and spaces for family life and care are created. A critical element found also in this part of third generation literature is, however, the fact that empirical accounts almost exclusively refer to families belonging to associations and their surroundings, mainly to those associated with Famiglie Arcobaleno. This expedient strategy brings about at least two methodological problems: first, the reported narratives and accounts are partial, since they do not take into consideration all those fields that escape from activism and visibility and leave out parents who avoid associations and rely on other channels and networks. At the same time, referring only to a single association to recruit families risks giving voice only to parents with similar characteristics, experiences, and stories.

Last but not least, in a context in which the sphere of family, which is affective, moral, and intimate, is highly dependent on the political and institutional sphere, research on LGBT+ parenting is conditioned by these circumstances. When law and policies establish that only some individuals, based on specific characteristics, can take care of children while other people who do not have the required characteristics cannot be or be recognized as parents (Pratesi, Citation2017), associations of advocacy and their affiliates aim to demonstrate their being as capable as other parents. A likely inevitable consequence of this situation is a lacking debate, even in scientific production, on more problematic dimensions of parenting and family life such as conflict, violence, moments of crisis, and stress due to internal family dynamics. These themes and issues are still largely left out in the Italian sociological literature on LGBT+ parenting.

Conclusions

Until recent years, issues related to LGBT+ parenting have found limited space in Italian sociology and the debate has been characterized by few contributions, published with discontinuity and in most cases by the same few research groups and their affiliates. However, reviewing sociological contributions is particularly relevant to understand the contextualized nature of the debate against its wider social and political background and to point out how the sociological debate takes up and contributes to the construction of LGBT+ parenting issues, especially during particular historical moments when certain groups and issues occupy a prominent position in public debates.

As this analysis has shown, the recent relaunch of the parliamentary debate on the legal recognition of same-sex couples and contentious public debates about same-sex couples as parents have given life to what has been called a third generation of studies and scholarly literature on LGBT+ parenting within Italian sociology.

The analysis has also shown that the debate has turned its interest to a variety of issues leading to a scientific production that is, although limited in quantity, characterized by a vivid and heterogeneous debate with interesting contributions in both theoretical and empirical respects and by a critical discussion of (lacking) policies and forms of recognition. At the same time, many issues still appear too infrequently or are not considered at all. So far, most studies have focused on same-sex couples problematizing their parenting challenges and difficulties in contexts of lacking recognition. Unlike the international scientific production, the Italian literature produced since 2013 is still far from providing a comprehensive view of different parents, parenting issues, and experiences subsumed under the acronym of LGBT+ parenting.

Despite these limitations, the scientific production in this field is important and to be encouraged, since scholarly literature and debates – thanks to the vocabulary used and the dimensions empirically investigated – contribute to socializing the idea that there are different ways of understanding parenting and doing family, as opposed to a standardized, ideological, and still too widespread vision of a ‘traditional’ family. In this sense, sociological work on LGBT+ parenting also has the merit of implicitly encouraging and promoting social change that, eventually, may also lead to better recognition and legal improvements, in Italy and elsewhere.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainslie, J., & Feltey, K. M. (1991). Definitions and dynamics of motherhood and family in lesbian communities. Marriage & Family Review, 17(1-2), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v17n01_05

- Allen, K. R., & Demo, D. H. (1995). The families of lesbian and gay men: A new frontier in family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/353821

- Assefa, S. G., & Rorissa, A. (2013). A bibliometric mapping of the structure of STEM education using co-word analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(12), 2513–2536. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22917

- Baiocco, R., Carone, N., Ioverno, S., & Lingiardi, V. (2018). Same-sex and different-sex parent families in Italy: Is parents’ sexual orientation associated with child health outcomes and parental dimensions? Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(7), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000583

- Baiocco, R., & Laghi, F. (2013). Sexual orientation and the desires and intentions to become parents. Journal of Family Studies, 19(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2013.19.1.90

- Baiocco, R., Nardelli, N., Pezzuti, L., & Lingiardi, V. (2013). Attitudes of Italian heterosexual older adults towards lesbian and gay parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0129-2

- Baiocco, R., Rosati, F., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Carone, N., Ioverno, S., & Laghi, F. (2020). Attitudes and beliefs of Italian educators and teachers regarding children raised by same-sex parents. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17(2), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00386-0

- Baiocco, R., Santamaria, F., Ioverno, S., Fontanesi, L., Baumgartner, E., Laghi, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2015). Lesbian mother families and gay father families in Italy: Family functioning, dyadic satisfaction, and child well-being. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(3), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0185-x

- Barbagli, M. (1984). Sotto lo stesso tetto: mutamenti della famiglia in Italia dal XV al XX secolo. Il Mulino.

- Barbagli, M. (1990). Provando e riprovando: matrimonio, famiglia e divorzio in Italia e in altri paesi occidentali. Il Mulino.

- Barbagli, M. (2004). Lo stato delle famiglie in Italia. Il Mulino.

- Barbagli, M., & Colombo, A. (2001). Omosessuali moderni. Gay e lesbiche in Italia. Il Mulino.

- Barbagli, M., & Saraceno, C. (1997). Lo stato delle famiglie in Italia. Il Mulino.

- Barbagli, M., & Saraceno, C. (2002). Separarsi in italia. Il Mulino.

- Beck, E. T. (1983). The motherhood that dare not speak its name. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 11(4), 8–11.

- Bertocchi, F., & Guizzardi, L. (2017). We are family. Same-sex families in the Italian context. Italian Sociological Review, 7(3), 271–273. https://doi.org/10.13136/isr.v7i3.191

- Bertone, C. (2009). Le omosessualità. Carocci.

- Bertone, C. (2015). Il fascino discreto delle famiglie omogenitoriali. Dilemmi e responsabilità della ricerca. Cambio, V(9), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.13128/cambio-19188

- Bertone, C., Casiccia, A., Saraceno, C., & Torrioni, P. (2003). Diversi da chi? Gay, lesbiche, transessuali in un’area metropolitana. Guerini & Associati.

- Biblarz, T. J., & Savci, E. (2010). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00714.x

- Bimbi, F., & Trifiletti, R. (2000). Madri sole e nuove famiglie. Declinazioni inattese della genitorialità. Edizioni Lavoro.

- Bonaccorso, M. (1994). Mamme e papà omosessuali. Editori Riuniti.

- Bosisio, R., & Ronfani, P. (2015). Le famiglie omogenitoriali. Responsabilità, regole, diritti. Carocci.

- Bosisio, R., & Ronfani, P. (2016). ‘Who is in your family?’ Italian children with non-heterosexual parents talk about growing up in a non-conventional household. Children & Society, 30(6), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12148

- Bottino, M., & Danna, D. (2005). La gaia famiglia. Che cos’è l'omogenitorialità. Asterios.

- Bozett, F. W. (1981). Gay fathers. Identity conflict resolution through interactive sanctioning. Alternative Lifestyles, 4(1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01082090

- Carone, N. (2016). In origine è il dono. Donatori e portatrici nell'immaginario delle famiglie omogenitoriali. Il Saggiatore.

- Carone, N., Baiocco, R., Ioverno, S., Chirumbolo, A., & Lingiardi, V. (2017). Same-sex parent families in Italy: Validation of the Coparenting Scale-revised for lesbian mothers and gay fathers. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(3), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1205478

- Carone, N., Baiocco, R., Lingiardi, V., & Kerns, K. (2020). Child attachment security in gay father surrogacy families: Parents as safe havens and secure bases during middle childhood. Attachment & Human Development, 22(3), 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1588906

- Carone, N., Lingiardi, V., Chirumbolo, A., & Baiocco, R. (2018). Italian gay father families formed by surrogacy: Parenting, stigmatization, and children’s psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 54(10), 1904–1916. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000571

- Cavina, C., & Danna, D. (2009). Crescere in famiglie omogenitoriali. Franco Angeli.

- Chambers, D. (2012). A sociology of family life: Change and diversity in intimate relations. Wiley.

- Corbisiero, F. (2014). Omogenitorialità: azioni, politiche e strategie europee per le famiglie arcobaleno. Voci. Annuale di scienze umane, XI, 11–23.

- Corbisiero, F., & Monaco, S. (2013). Città arcobaleno. Politiche, servizi e spazi Lgbt nell’Europa dell’uguaglianza sociale. In F. Corbisiero (Ed.), Comunità omosessuali. Le scienze sociali sulla popolazione LGBT (pp. 263–283). Franco Angeli.

- Corbisiero, F., & Monaco, S. (2014). European rainbow citizens: The extent of social inclusion. In A. Amodeo & P. Valerio (Eds.), Hermes - linking network to fight sexual and gender stigma (pp. 103–119). Liguori Editore.

- Corbisiero, F., & Monaco, S. (2017). Città arcobaleno. Una mappa della vita omosessuale nell’Italia di oggi. Donzelli Editore.

- Corbisiero, F., & Monaco, S. (2020). The right to a rainbow city: The Italian homosexual social movements. Society Register, 4(4), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.14746/sr.2020.4.4.03

- Corbisiero, F., & Ruspini, E. (2015, December 28). Famiglie a metà. L’omogenitorialità in Italia. InGenere.

- Danna, D. (1998). Io ho una bella figlia. Le madri lesbiche raccontano. Zoe Media.

- Danna, D. (2015). Contract children: Questioning surrogacy. Stuttgart.

- Danna, D. (2018). The Italian debate on civil unions and same-sex parenthood: The disappearance of lesbians, lesbian mothers, and mothers. Italian Sociological Review, 8(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.13136/isr.v8i2.238

- De Sutter P., K., Verschoor A, K., & Hotimsky, A. (2002). The desire to have children and the preservation of fertility in transsexual women: A survey. International Journal of Transgenderism, 6, 836.

- Dunne, G. A. (2000). Opting into motherhood. Lesbians blurring the boundaries and transforming the meaning of parenthood and kinship. Gender & Society, 14(1), 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124300014001003

- Farr, R. H., Tasker, F., & Goldberg, A. E. (2017). Theory in highly cited studies of sexual minority parent families: Variations and implications. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(9), 1143–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1242336

- Field, S. S. (2002). Coparent or second-parent adoption by same-sex parents. Pediatrics, 109(6), 1193–1194. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.109.6.1193-a

- Fitzgerald, B. (1999). Children of Lesbian and Gay parents. Marriage & Family Review, 29(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v29n01_05

- Fortier, C. (2015). Transparentalité: Vécus Sensibles de Parents et D’enfants. Enfances, Familles, Générations, 23(23), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.7202/1034205ar

- Franchi, M., & Selmi, G. (2020). Same-sex parents negotiating the law in Italy: Between claims of recognition and practices of exclusion. In M. Digoix (Ed.), Same-sex families and legal recognition in Europe (European Studies of Population, Vol. 24, pp. 73–94). Springer.

- Gabb, J. (2008). Researching intimacy in families. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Gabb, J., McDermott, E., Eastham, R., & Hanbury, A. (2019). Paradoxical family practices: LGBTQ+ young people, mental health and wellbeing. Journal of Sociology, 56(4), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319888286

- Garbagnoli, S. (2014). L’ideologia Del Genere: L’irresistibile Ascesa Di Un’invenzione Retorica Vaticana Contro La Denaturalizzazione Dell’ordine Sessuale. AG About Gender, 3(6), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.15167/2279-5057/ag.2014.3.6.224

- Garbagnoli, S., & Prearo, M. (2018). La crociata “anti-gender”. Dal Vaticano alle manif pour tous. Kaplan.

- Giunti, D., & Fioravanti, G. (2017). Gay men and lesbian women who become parents in the context of a former heterosexual relationship: An explorative study in Italy. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(4), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1191244

- Goldberg, A. E., & Allen, K. R. (2020). LGBTQ-parent families: Innovations in research and implications for practice. Springer.

- Goldberg, A. E., & Gartrell, N. K. (2014). LGB-parent families: The current state of the research and directions for the future. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 46, 57–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800285-8.00003-0

- Grilli, S. (2019). Antropologia delle famiglie contemporanee. Carocci.

- Gross, M. (2003). L’homoparentalité. PUF.

- Gross, M. (2015). L’homoparentalité et la transparentalité au prisme des sciences sociales: révolution ou pluralisation des formes de parenté? Enfances familles générations, 23, 1–37.

- Hafford-Letchfield, T., Cocker, C., Rutter, D., Tinarwo, M., McCormack, K., & Manning, R. (2019). What do we know about transgender parenting?: Findings from a systematic review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1111–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12759

- Hérault, L. (2014). La parenté transgenre. Presses universitaires de Provence.

- Hicks, S. (2011). Lesbian, gay and queer parenting. Families, intimacies, genealogies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hines, S. (2007). Intimate transitions: Transgender practices of partnering and parenting. Sociology, 40(2), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038506062037

- ISPES. (1991). Il sorriso di Afrodite. Rapporto sulla condizione omosessuale in Italia. Vallecchi Editore.

- Jurczyk, K. (2014). Doing Family – der Practical Turn der Familienwissenschaften. In A. Steinbach, M. Hennig, & O. Arránz Becker (Eds.), Familie im Fokus der Wissenschaft (pp. 117–138). Familienforschung. Springer.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Lancia, F. (2004). Strumenti per l'Analisi dei Testi. Franco Angeli.

- Lancia, F. (2012). Strumenti per la ricerca psico-sociale: di base e applicata. Franco Angeli.

- Lasio, D., & Serri, F. (2017). The Italian public debate on same-sex civil unions and gay and lesbian parenting. Sexualities. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717713386

- Lelleri, R., Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2008). Omogenitorialità: i risultati di una ricerca italiana. Difesa Sociale, 4(8), 71–83.

- Lytle, M. C. (2019). LGBT parenting. In J. S. Schneider, V. M. B. Silenzio, & L. Erickson-Schroth (Eds.), The GLMA handbook on LGBT health (pp. 185–202). Praeger Pub Text.

- Mallon, G. P. (2004). Gay men choosing parenthood. Columbia University Press.

- Mancina, C., & Vassallo, N. (2016). Unioni civili? Un dialogo sulla legge approvata dal Parlamento italiano. Iride, 29(79), 551–564.

- Marotta, I., & Monaco, S. (2016). Napoli Rainbow? Famiglie omogenitoriali: politiche e buone prassi nel capoluogo Campano. StrumentiRES, 8(4), 1–16.

- Miller, B. (1978). Adult sexual resocialization. Adjustments toward a stigmatized identity. Alternative Lifestyles, 1(2), 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01082414

- Monaco, S. (2016). I nuovi alfabeti delle famiglie arcobaleno: tra diritti e rovesci. In F. Corbisiero & R. Parisi (Eds.), Famiglia, omosessualità, genitorialità. Nuovi alfabeti di un rapporto possibile (pp. 35–41). PM Edizioni.

- Monaco, S. (2017). Le unioni civili nelle parole (a stampa) dei sindaci. In F. Corbisiero & S. Monaco (Eds.), Città arcobaleno, una mappa della vita omosessuale inItalia (pp. 103–122). Donzelli.

- Monaco, S., & Nothdurfter, U. (2020). Genitorialità LGBT+: parole e riflessioni della sociologia italiana. In M. Coppola, A. Donà, B. Poggio, & A. Tuselli (Eds.), Genere e R-Esistenze in Movimento. Soggettività, azioni, prospettive (pp. 197–209). GSG – University of Trento.

- Moore, R. M., & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, M. (2013). LGBT sexuality and families at the start of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology, 39(1), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145643

- Morgan, D. H. J. (2011). Rethinking family practices. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Naldini, M., & Saraceno, C. (2013). Sociologia della famiglia. Il Mulino.

- Nigris, D. (2003). Standard e non-standard nella ricerca sociale. Riflessioni metodologiche. Franco Angeli.

- Parisi, R. (2018). Filiazione e genitorialità tra pratiche, rappresentazioni e diritto. Il caso dell’omogenitorialità in Italia. EtnoAntropologia, 5(2), 1–19.

- Patterson, C. (2000). Family relationships of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1052–1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01052.x

- Patterson, C. J. (2006). Children of lesbian and gay parents, current directions. Psychological Science, 15(5), 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00444.x

- Plummer, K. (1992). Modern homosexualities. Fragments of lesbian and gay experience. Routledge.

- Poure, V. (2013). Vers un statut familial de la personne transsexuelle? Recherches Familiales, 10(1), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.3917/rf.010.0175

- Pratesi, A. (2017). Doing care, doing citizenship: Towards a micro-situated and emotion-based model of social inclusion. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Raister, F., Cavazza, M., & Abeillé, A. (2002). Semantics for descriptions. CSLI.

- Reczek, C. (2020). Sexual- and gender-minority families: A 2010 to 2020 decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 300–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12607

- Ruspini, E. (Ed.). (2010). Monoparentalité, homoparentalité et transparentalité en France et en Italie. L’Harmattan.

- Ruspini, E. (Ed.). (2012). Studiare la famiglia che cambia. Carocci.

- Ruspini, E. (2015). Diversity in family life. Gender, relationship and social change. Policy Press.

- Ruspini, E., & Luciani, S. (2010). Nuovi genitori. Carocci.

- Ryan-Flood, R. (2009). Lesbian motherhood. Gender, families and sexual citizenship. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Saraceno, C. (2008). Fare famiglia, letteralmente. Parolechiave, 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.7377/70502

- Saraceno, C. (2012). Coppie e famiglie. Non è questione di natura. Feltrinelli.

- Saraceno, C. (2017). L’equivoco della famiglia. Laterza.

- Satta, C., Magaraggia, S., & Camozzi, I. (2020). Sociologia della vita famigliare: Soggetti, contesti e nuove prospettive. Carocci.

- Scallen, R. M. (1982). An investigation of paternal attitudes and behaviors in homosexual and heterosexual fathers. Dissertation Abstracts International, 42(9-B), 3809.

- Scandurra, C., Monaco, S., Dolce, P., & Nothdurfer, U. (2020). Heteronormativity in Italy: Psychometric characteristics of the Italian version of the Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00487-1

- Selmi, G. (2015). Chi ha paura della libertà? La così detta ideologia del gender sui banchi di scuola. AG About Gender, 4(7), 263–268. https://doi.org/10.15167/2279-5057/ag.2015.4.7.291

- Sonego, A., Podio, C., Benedetti, L., Pierri, M., Buonapace, N., Vismara, P., & Conti, R. (2005). Gruppo Soggettività Lesbica e Libera Università delle Donne di Milano. Cocktail d’amore. 700 e più modi di essere lesbica. DeriveApprodi.

- Stacey, J. (2004). Cruising to familyland: Gay hypergamy and rainbow kinship. Current Sociology, 52(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392104041807

- Starbuck, G. H., & Lundy, K. S. (2016). Families in context: Sociological perspectives. Routledge.

- Sullivan, M. (2004). The family of woman. Lesbian mothers, their children and the undoing of gender. University of California Press.

- Tasker, F. L., & Golombok, S. (1997). Growing up in a lesbian family: Effects on child development. Guilford Press.

- Trappolin, L. (2016). The construction of lesbian and gay parenthood in sociological research. A critical analysis of the international literature. Interdisciplinary Journal of Family Studies, XXI, 41–59.

- Trappolin, L. (2017). Pictures of lesbian and gay parenthood in Italian sociology. A critical analysis of 30 years of research. Italian Sociological Review, 7(3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.13136/isr.v7i3.193

- Trappolin, L., & Tiano, A. (2015). Same-sex families e genitorialità omosessuale. Controversie internazionali e spazi di riconoscimento in Italia. Cambio, 5(9), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.13128/cambio-19189

- Trappolin, L., & Tiano, A. (2019). Diventare genitori, diventare famiglia. Madri lesbiche e padri gay in Italia tra innovazione e desiderio di normalità. CEDAM.

- Treas, J., Richards, M., & Scott, J. L. (2017). The Wiley Blackwell companion to the sociology of families. Wiley.

- Tuzzi, A. (2003). L’analisi del contenuto. Carocci.

- van Eeden-Moorefield, B., Few-Demo, A. L., Benson, K., Bible, J., & Lummer, S. (2018). A content analysis of LGBT research in Top family journals 2000-2015. Journal of Family Issues, 39(5), 1374–1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X17710284

- Waltman, L., Van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. M. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics, 4(4), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.07.002

- Zamperini, A., Testoni, I., Primo, D., Prandelli, M., & Monti, C. (2016). Because moms say so: Narratives of lesbian mothers in Italy. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2015.1102669

- Zanatta, A. L. (2011). Nuove Madri e Nuovi Padri: Essere Genitori Oggi. Il Mulino.