ABSTRACT

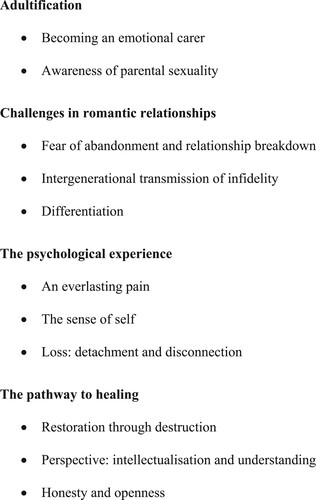

The current study explored the lived experience of parental infidelity; how individuals make sense of this experience and what its' implications are. Qualitative data were collected from individual, semi-structured interviews with six adult participants. An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis methodology was used and a critical realist epistemological stance was taken. Analyses revealed findings of four master themes: adultification, challenges in romantic relationships, the psychological experience and the pathway to healing. These master themes were sub-categorized into super-ordinate themes as follows: adultification – becoming an emotional carer and awareness of parental sexuality, challenges in romantic relationships – fear of abandonment and relationship breakdown, intergenerational transmission of infidelity and differentiation, the psychological experience – an everlasting pain, the sense of self and loss: detachment and disconnection, the pathway to healing – restoration through destruction, perspective: intellectualization and understanding and honesty and openness. Theoretical, research and clinical implications alongside limitations and ideas for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Infidelity has been defined as the ‘breach of trust and/or violation of agreed upon norms’ (Blow & Hartnett, Citation2005, p. 192) within a romantically, sexually and emotionally exclusive monogamous relationship.

Various dimensions of infidelity within the relationship dyad have been researched. Moller and Vossler (Citation2015) have focused on defining infidelity as an empirical, theoretical and therapeutic construct, Stewart (Citation2017) has explored the implications of gender, attitudes and attachment styles on the perception of infidelity and studies have investigated the impact of infidelity on the partner who has been betrayed (Cano & O’Leary, Citation2000) and how couples who have experienced infidelity can be helped therapeutically (Kessel et al., Citation2007; Snyder et al., Citation2008). However, there has been less exploration of the experience of infidelity, for individuals outside of the relationship dyad, such as their offspring.

According to Lusterman (Citation2005), parental infidelity may shatter the expectations children had of their parents; the role models they believed would always provide a feeling of safety and security. Thus, when parents fail to meet these expectations, children are likely to experience distress. However, there remain unanswered questions regarding how this distress may be manifested and what is truly encompassed in the lived experience of parental infidelity.

Adult romantic relationships

A predominant theme elucidated in the existing literature is the implications of parental infidelity for the romantic relationships of adult offspring. Nogales and Bellotti (Citation2009) found that adult offspring who had experienced parental infidelity were likely to experience difficulties in maintaining healthy romantic relationships. The study found that 70% of participants stated that their experience of parental infidelity lessened their abilities to trust their romantic partners. Gottman (Citation2011) highlights the importance of having a strong sense of trust within relationships and the fundamental role it plays, in both partners feeling safe, secure and able to be open with one another. Amongst individuals who have experienced parental infidelity, a weak or an entirely absent sense of trust within their romantic relationships can reduce the level at which they are willing to allow themselves to be guided or supported by their romantic partners and/or are able to experience sexual curiosity. This lessened sense of trust has also been found to be positively correlated with these individuals being more likely to engage in infidelity themselves (Cramer et al., Citation2001) and this intergenerational transmission of infidelity is a theme which has appeared throughout the literature as multiple studies have revealed a significant positive correlation between parental infidelity and having engaged in infidelity behaviours (Havlicek et al., Citation2011; Weiser, Citation2013) or likelihood to engage in infidelity (Platt et al., Citation2008; Weiser et al., Citation2017).

Further exploring the intergenerational influences of parental infidelity on the romantic relationships of adult offspring, a limited amount of research has taken a more systemic approach by adopting the ‘contextual therapy model’ framework and exploring the role of ‘relational ethics’ (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Krasner, Citation1986). This framework explores how the act of parental infidelity, a clear violation of trust and loyalty, may influence adult offspring’s perceptions of relational ethics within their own romantic relationships (Schmidt et al., Citation2016). Relational ethics within relationships of individuals of the same generation, i.e. romantic partners are labelled ‘horizontal’, whilst relational ethics within intergenerational relationships, i.e. parent–child relationships are labelled ‘vertical’ (Hargrave et al., Citation1991).

Schmidt et al. (Citation2016) found a significant correlation between paternal infidelity and lowered levels of ‘horizontal’ relational ethics. Similarly, Kawar et al. (Citation2019) found that participants who had been exposed to parental infidelity scored significantly lower, than participants who had not, on the vertical relational ethics measures and on the horizontal relational ethics measures, indicating that parental infidelity can negatively influence individuals’ relationships with members of their family of origin and their romantic partners.

Topic avoidance

Infidelity is a topic often regarded as ‘taboo’ (Baxter & Wilmot, Citation1985) and has been shown to be completely immersed and entangled in secret keeping, privacy and topic avoidance (Lusterman, Citation2005; Vangelisiti, Citation1994; Vangelisti & Caughlin, Citation1997).

Lusterman (Citation2005) suggests that even if parents haven’t explicitly discussed with offspring the fact that parental infidelity has taken place, the conflict and tension between parents can still negatively impact children. For younger children, there may be an unconscious response to parental anxiety or conflict, which can manifest in their becoming whiny or increasingly irritable. For slightly older children of an adolescent age, the experience may be one of becoming slightly aware of tension but feeling unsure whether or not to question the source of the tension or to reveal any information they have become exposed to. Adult children are much more likely to be fully aware of the tension and explicitly question their parents regarding its source.

Thorson (Citation2009) explored how individuals manage the information they become exposed to, following parental infidelity and the potential enactment of ‘rules’, by offspring, regarding the protecting of information of the providing of access to information, about the parental infidelity. The study found that offspring described enacting two ‘protection rules’ (Petronio, Citation2002), which were categorized as ‘external’; referring to participants’ endeavours to protect information about the infidelity from individuals outside of the family in an attempt to avoid ‘scrutiny’ and ‘internal’; referring to participants’ trying to protect the information about the infidelity, within the family, in order to avoid other family members becoming upset.

Thorson (Citation2017) highlights the fact that the topic-avoidant nature of parental infidelity presents a dilemma for offspring regarding whether to adopt an individual, or a communal style of coping. Furthermore, Thorson (Citation2017) explored how adult children cope with their experiences of parental infidelity and convey their feelings of condemnation or unhappiness, regarding their parents’ behaviour, within a ‘topic avoidant environment’. The study elucidated three strategies of coping: ‘communicative sanctions’ which offspring place upon their parents, ‘acting out’ and ‘setting ground rules’. Firstly, the communicative sanctions were categorized into: ‘withholding address terms’, ‘withholding terms of endearment’ and ‘giving the silent treatment’. Next, acting out was categorized into: ‘using the information’ which referred to participants’ using information about the infidelity to intentionally induce power, hurt or embarrass the unfaithful parent and ‘outbursts’. Whilst the ‘outbursts’ did not address the infidelity and continued to uphold the avoidance of this topic within the family, it manifested in a way which ‘allowed the anxious “fever” to break’ (Thorson, Citation2017, p. 183) and therefore was experienced as a form of relief for participants. Finally, the setting of ‘ground rules’; which was reported by participants as a mechanism to cope with changes in the family structure, for example the developing relationship with a step-parent or relational dynamics between new siblings.

In stark contrast to avoidance of the subject, Brown (Citation2001) suggests that some parents discuss the infidelity incessantly with their children. The reason for this may be that parents are seeking closure, or it may be due to parents using this as a tool to create new bonds and alliances with their children against the other parent. The latter can be particularly problematic as it can result in children being exposed to inappropriate disclosures and/or feeling conflicted regarding their loyalty and thus feeling caught in between their parents; a feeling which has been positively correlated with worsened mental health (Schrodt & Afifi, Citation2007). This highlights that parental infidelity can affect offspring, both, if the infidelity becomes a source of secrecy and topic avoidance or, is discussed continually.

Communication and the role of familial messages

Despite being very limited, there has been some exploration in the literature, of the messages that children receive from members of their family, following parental infidelity, and the role this may play in the experience they have.

Thorson (Citation2014) explored the impact of messages received following the discovery of parental infidelity, on the extent to which offspring experience ‘feeling caught’. The term ‘feeling caught’ has been defined as an occurrence of triangulation; which children find themselves in the middle of parental disputes (Schrodt & Afifi, Citation2007) and experience a ‘loyalty conflict’ when teams begin to form within the family system and are opposing of one another (Emery, Citation1994). The study found that participants described received messages, both passive and active, that were both discouraging of their ‘feeling caught’; these were categorized as: ‘keeping conflict between the parents’, ‘there is no good/bad guy’ and ‘change is good’ and encouraging of their ‘feeling caught’; these were categorized as: ‘uncovering information’, ‘child as mediator’ and ‘managing other family members’ opinions’.

In a similar thread, April and Schrodt (Citation2018) explored the influence of disclosing parental infidelity to offspring, in the style of ‘person-centred messages’, on the way in which offspring then attribute responsibility and their willingness to forgive the infidelity. The ‘person-centredness’ of the messages of disclosure were assessed using an adaption of the ‘person-centred scale’, developed by Jones and Guerrero (Citation2001) and included items rating how sensitive, helpful, understanding, caring, warm and supportive, participants perceived their parents’ messages of disclosure to be. The study revealed a significant negative correlation between participants’ attribution of responsibility to the unfaithful parent and their level of willingness to forgive. However, analyses revealed there to be no significant correlation between the person-centredness of the messages of disclosure and the level of the participants’ willingness to forgive their unfaithful parent and no significant correlation between the person-centredness of the messages and the participants’ attribution of responsibility. In considering why these results may not have been significant, the researchers highlight the fact that the situations in the study were hypothetical; the participants had not experienced parental infidelity in their real lives, which may have influenced the validity of the results.

Exploring a slightly different strand of communication, Thorson (Citation2019) investigated the impact of communication on adult children’s forgiveness of parental infidelity. The study found that the likelihood of adult children forgiving their unfaithful parent is higher if they receive a sincere apology from the unfaithful parent for the infidelity. The study also found that a child’s empathy for the parent and a child’s ‘positively valenced attributions’ for the causality of the parents’ infidelity were significant mediators of forgiveness.

Much of the existing research has taken a quantitative approach; restricting the experience of parental infidelity to quantifiable variables and thus resulting solely in insight into correlative associations in many cases. Taking a quantitative approach can reduce the complexity and multifaceted nature of human experience, which qualitative researchers can gauge the scope of, by immersing themselves into participants’ social worlds and allowing them to communicate the sense they make of their experiences, in their own words (Liamputtong, Citation2013). Amongst the qualitative research in this field, there is a gap in the literature for contemporary research which does not focus on a particular thread or adopt a particular theoretical framework or lens. Though these studies have generated very valuable knowledge, this can be somewhat restrictive of important elements of the overarching experience. In addition, the existing literature predominantly takes a snapshot approach; the majority of the studies are looking at a particular time period; for example, after concluding their research April and Schrodt (Citation2018) have reflected on the fact that the absence of significant results in their study may have in part, been due to the fact that they only explored the experience of parental infidelity at the stage of the infidelity being disclosed to offspring; concluding that an individual’s needs may differ across different stages of the experience of parental infidelity.

These factors elucidate the gap in the literature for phenomenology; an in-depth dynamic exploration of the overarching lived experience of parental infidelity.

In this research, the terms ‘child’ or ‘children’ may refer to offspring of any age, unless specified.

Materials and methods

Methodology

The study adopted an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith, Citation1996) methodology.

This methodology draws on three key theoretical underpinnings: phenomenology, hermeneutics and ideography (Smith et al., Citation2009).

The phenomenological school of thought aims to gain insight into the lived experience of a phenomenon, as it occurs, from the point of view of the subject (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2003a). Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the founder of transcendental phenomenology believed that subjective human experience cannot be isolated from an objective world (Zahavi, Citation2003). He took a critical view of the ‘knowledge claims’ made by science, putting forth that ‘Lebenswelt’; the ‘lifeworld’; which refers to ‘the taken-for granted, every-day life that we lead’ (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 15) is a ‘precursor’ to scientific enquiry (Smith et al., Citation2009). Husserlian phenomenology placed great emphasis on the ‘intentional’ relationship between ‘objects’ and the conscious experience (McIntyre & Smith, Citation1989). Husserl believed that in order to truly understand the essentiality of this subjective experience, one must take on a ‘phenomenological attitude’, which necessitates the reflexive process of attending our gaze to each specific thing as it appears, rather than as a part of a system in which it exists (Husserl, Citation1927). He proposed the ‘phenomenological method’ which consists of ‘epoché’ ‘phenomenological reduction’ and ‘imaginative variation’ (Moustakas, Citation1994). Epoché refers to the concept of ‘bracketing’ individual biases, presuppositions, typifications, in an attempt to ‘invalidate’, ‘inhibit’ and ‘disqualify’ (Schmitt, Citation1959, p. 239) our perceived validity of prior knowledge and experience. Phenomenological reduction refers to the reduction of what is being presented, into ‘mere phenomena’ (Husserl, Citation1925/Citation1977, p. 20); elucidating the content of what is being consciously experienced (Willig, Citation2013). Finally, the ‘imaginative variation’ is a reflective process in which one strives to understand ‘how’ and experience has come to being, by considering various alternative structural elements such as time, spatial and relational qualities (Brann, Citation1991).

Hermeneutics is the theoretical study of interpretation; the implications of which, have significantly impacted the development of IPA; an interpretative approach to phenomenology. Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) believed that description and interpretation are not distinct entities and that an individual’s access to the lived experience is always by way of interpretation (Heidegger, Citation1962). He proposed that the aim of phenomenology is dually perceptual and analytical; it is not only to explore the meanings of what visibly appears before us, but also to examine meanings which may exist latently; a process which requires interpretation (Moran, Citation2000). In contrast to Husserl, Heidegger argues that sense-making is a dynamic and cyclical process. He believes it is impossible to entirely bracket out ‘fore-conception’ each time we encounter a new ‘object’, and whilst these presuppositions can inform our understanding of new things, the new things can also elucidate the nature of these presuppositions (Smith et al., Citation2009). This concept is highlighted in the theory of the ‘hermeneutic circle’ (Gadamer, Citation1990; Schleiermacher, Citation1998) which refers to the circularly process in which; to understand the whole, you must understand the parts, and to understand the parts you must understand the whole; an integral element of the IPA analytic strategy.

Idiography refers to the focus on specifics; the exploration of the phenomenon in great depth, from individual viewpoints, within a given context (McLeod, Citation2015). Researchers argue that nomothetic approaches fail to account for distinctive human dispositions (Allport, Citation1961) or provide a detailed understanding of emotional, behavioural and psychological processes at the individual level (Smith et al., Citation1995).

Rationale for this approach

It was believed that this research would be particularly well-aligned with this methodology because of its compatibility with the theoretical underpinnings. Firstly, phenomenology; the focus of the study is exploring the lived experience of the phenomenon of parental infidelity. IPA allows participants to convey their experience from their own perspective, without imposing restrictions such as preselected theoretical notions. This elucidates the significant aspects of a specific experience in a particular context (Larkin et al., Citation2006). The aim of this methodology is to explore the meanings participants attach to their experience and gain insight into the process involved in their sense-making (Larkin et al., Citation2011). This is consistent with the aims of this research.

Next, hermeneutics; IPA posits that whilst the researcher can gain insight into this experience, analyses will be an interpretation; mediated by the participant, researcher and their interaction (Larkin & Thompson, Citation2012). This is consistent with the researcher’s epistemological stance; as IPA does not deny the existence of a ‘reality’ but is concerned with the nature and meaning of this reality for the subject, which was a core focus of this research. ‘IPA is a version of the phenomenological method that accepts the impossibility of gaining direct access to research participants’ life worlds’ (Willig, Citation2013, p. 87). It aims to gain insight into the subjective, lived experience of a given phenomenon whilst recognizing that the researcher’s views and assumptions will inevitably become constituents of subsequent analyses, which must be acknowledged as an interpretation rather than a direct depiction of the experience. This analytic process is referred to as a ‘double hermeneutic because the researcher is trying to make sense of the participant trying to make sense of what is happen to them’ (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 3).

Thirdly, idiography; the focus of this research was to elucidate a detailed understanding of each individual’s lived experience. This was identified as a fundamental gap in the existing literature which this research aimed to address. This was also important for the potential outcomes of this research by way of clinical implications; for which an understanding of the individual, subjective, lived experience is fundamental.

In addition, IPA has been found to be valuable in the study of subject matter which is ‘emotionally laden’ (Smith & Osborn, Citation2015, p. 1), which it was felt parental infidelity is.

Participants

Data collected from a purposive sample of six individuals who have experienced parental infidelity was analysed. The justification of this sample size is based upon four principles; ‘richness and volume of data’, ‘qualities of the analysis’, ‘pragmatic considerations’ and ‘sample size guidelines’ as outlined by Vasileiou et al. (Citation2018). This is an IPA study, in which ‘small’ sample sizes are advocated for (Vasileiou et al., Citation2018) because the theoretical and epistemological foci is to present an idiographic, intensive analytic account of participants’ lived experiences. The number of participants follows sample size guidelines (Smith et al., Citation2009). It is also explained that in IPA, a larger sample size should not be viewed as ‘better’ as the depth of reflection and time required for successful analyses can be inhibited by larger samples (Smith et al., Citation2009). The data collected from the individual interviews was deemed high in richness and volume, extremely detailed and capturing of the complexity of the experience. Pragmatic considerations were also important; with regard to feasibility due to the significant time dedicated to each participant’s account and reflection and an acknowledgement of the potential challenges to recruitment due to the sensitive nature of the topic.

The demographic profile of the study was dependent upon the willingness of individuals to volunteer their participation, as the aim of IPA studies is to obtain a ‘reasonably homogenous sample’ (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 3) whilst acknowledging pragmatism. In addition, the ‘extent of this homogeneity varies from study to study’ (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 49). For this study, the homogeneity was based upon the experience of parental infidelity and a criterion regarding the time since this experience took place, as these were deemed ‘relevant’ (Smith et al., Citation2009). Criterion regarding other factors such as age, gender and ethnicity were not set as there was no clear rationale elucidated by the existing literature to do so ().

Table 1. Summary of participant demographics.

Inclusion criteria

Parental infidelity could be maternal or paternal infidelity as the existing literature has not revealed sex effects meriting the exclusion of either. Infidelity referred solely to sexual infidelity as emotional infidelity appears to be harder to define (Fenigstein & Peltz, Citation2002).

Participants had to have discovered their parental infidelity at least 10 years prior to data collection. The rationale for this was two-fold. Firstly, upon consideration, a 10-year period was considered to be a sufficient amount of time to have processed the experience, reducing the likelihood of participation inducing distress. Secondly, in order to explore participant’s dynamic experience of parental infidelity, it was felt that a period of at least 10 years since discovery, would have allowed for some reflection upon the experience, which would be valuable for the research.

Participants had to be over 18 as this research is exploring the experience of adults.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals currently suffering from a severe mental health issue(s). It was felt that as parental infidelity is a sensitive topic, the potential risk of harm may be heightened.

Individuals known to the researcher

Data collection

Data was collected using one-to-one semi-structured interviews. This is the favoured method for IPA as it enables participants to voice their individual perspectives by speaking freely about their experiences, resulting in rich, in-depth data and the evolution of narratives in an authentic way as opposed to highly structured interviews which impose a fixed structure, into which participants must constrain their experience (Reid et al., Citation2005). The interview duration ranged between 55 and 95 min. Each participant was interviewed once; multiple interviews were considered but are typically more useful in longitudinal research or ‘before-and-after’ studies (Smith et al., Citation2009). An initial interview schedule (Appendix), outlining a small number of open-ended questions was constructed, to ensure that whilst interviews remained participant-led and the schedule was used flexibly, sufficient data, relevant to the research question, was being collected. To avoid ‘post-positivizing’ (Ponterro, Citation2005) the questions were not literature led. The formulation of each question was evaluated on: relevance to the research, contribution to the interview dynamic and ethicality (Kvale, Citation1996b). The order of questions was guided by Spradley (Citation1979); starting with descriptive questions before inviting an evaluative stance. Prompts were included as a tool. The researcher made notes in the reflexive journal before and after each interview.

Procedure

Individuals interested in taking part contacted the researcher via e-mail. Individuals were screened for suitability as outlined above. All the individuals the researcher was contacted by were eligible to take part. Each person was sent a participant information sheet, an informed consent form and it was requested that they consider their participation for at least 24 h, in order to encourage careful consideration and processing of the information provided. After that time, participants contacted the researcher to confirm their wish to participate and a date, time and location for the interview was set. At this stage, participants were asked to consider if there were any topics they were not willing to discuss and if so, to outline these. No issues arose at this stage. Once participants arrived at the interview, an introduction and an informal discussion about the interview took place. Participants were given an opportunity to ask questions and informed consent was obtained. Once each interview was over, participants were debriefed. Participants were asked to reflect on their experience of participation and if they had any questions. No further support was required at this stage, but if it had been, this would have been arranged.

A reflexive journal was kept by the researcher throughout the entire process of the research; to aid the reflexive process.

Ethics

This research has been conducted in accordance with the British Psychological Society code of human ethics (BPS, Citation2014) and ethical clearance has been obtained. It was recognized that parental infidelity is a sensitive topic, the potential impact of which, was important to address. Prior to the interview, participants were asked if there were any topics they were not willing to address and participant well-being was monitored throughout. At the end of each interview, provided that participants were interested, the potential therapeutic implications this research could have and the way in which it could potentially help other individuals who have also experienced parental infidelity were discussed. This was implemented because participants have shown less aversion to sensitive topics if they feel the outcome will be worthwhile (Lewis & Graham, Citation2007).

It is recognized that interpreting participants’ experiences involves a process of the researcher digesting and metabolizing the original material, which leads to something being added to, i.e. ‘transforming’ said material (Willig, Citation2012) resulting in a ‘blend of meanings, articulated by both participant and researcher’ (Lopez & Willis, Citation2004, p. 703). It is fundamental that the researcher address ‘ownership’. The researcher acknowledges that the interpretations may say an equal amount or more, about the researcher, as they do about the participants. Furthermore, the researcher recognizes the ‘considerable distance’ between the original data and any claims made about its meaning. The researcher honours and values the integrity of participant’s narrative accounts in their own right and endeavours to explore and amplify the layered meanings associated with their experience (Willig, Citation2012).

Analytic strategy

Data was transcribed verbatim. The analytic strategy was guided by the heuristic structure outlined by Smith et al. (Citation2009).

Each transcript was read multiple times. The first time for each, the audio of the interview was simultaneously listened to.

Annotations of elements which felt particularly interesting or important were noted on the right-hand side margin. Annotations were categorized; by noting them in different colours, black, red and blue for three groups: ‘descriptive’, ‘linguistic’ and ‘conceptual’, respectively. Descriptive comments were phenomenological in nature, referring to insight into the content. Linguistic comments were concerned with language, such as metaphors, in relation to conveying content. Here, it was considered whether the meanings of words used by participants were the same as they were for the researcher. Conceptual comments were interpretative in that focus was shifted from the specifics to an overarching understanding.

Next, the identification of ‘emergent themes’, noted in green on the left-hand side margin. The aim here was to map the ‘interrelationships’ between the annotations made during the ‘initial noting’ stage, but not base this solely on concrete chunks of the transcript but rather on the learning obtained through the annotation of the entire transcript. The key at this stage was to: ‘speak to the psychological essence of the piece and contain enough particularity to be grounded but enough abstraction to be conceptual’ (Smith et al., Citation2009).

For each participant, all emergent themes in chronological order, were listed and the process of clustering to develop sub-themes began. To do this, a range of methods were used; abstraction, polarization and numeration. Numeration was explored as it was felt that the frequency at which a theme emerges may reflect the importance to the individual, though this was done tentatively as it was not felt that frequency is a sole reflector of importance. This stage was processed cyclically to ensure generated themes remained representative of the original text. Once emergent themes were clustered, ‘sub-themes’ were given a descriptive label which encompassed all the emergent themes in that cluster and in order to reflect upon internal consistency, were each placed in a table with corresponding page/line numbers and key words. If it was felt that an emergent theme no longer appeared to be directly relevant to the research question, it was not included in any clusters.

The stages outlined above were repeated for each participant.

Each sub-theme was then written out and the researcher assigned a different colour to each participant and marked each post-it which had one of their sub-themes, with that colour. This was so that when clustering the sub-themes was completed, it could easily be detected whether each participant had been included in each cluster, in order to ensure that each ‘master’ theme, was representative of every participant. To get to this stage, one all sub-themes, from each case were laid out, the researcher began to search for patterns; where the connections, commonalities and divergences lay. Once all sub-themes had been clustered, a ‘master’ table of these themes was created.

Results

The data has been clustered into four master themes, each of which is then divided into super-ordinate themes. Each master theme is organized around an exploration of the lived experience of parental infidelity, the sense-making process and the meanings individuals have attached to this experience ().

Adultification

This master theme encapsulates participants’ experiences of early exposure to adult themes or behaviours and/or the adopting of adult-like roles, traits or responsibilities.

Becoming an emotional carer

Participants detailed experiences of having to become an emotional carer for their parent(s) in distress. This role appears to have been a heavy burden for participants; an experience which elicited feelings of fear that something may happen to their distressed parent, guilt if they felt they were not able to attend to their parents’ emotional needs and also anger and retrospective resentment, toward both the unfaithful parent and the betrayed parent, for calling upon them to take on this role. It was also an experience which elicited a dilemma for offspring between attending to their distressed parent, or their own emotional needs, which often resulted in participants internalizing their emotions due to fears of becoming an added stressor for the betrayed parent. The role encompassed children tending to parents’ distress which manifested in different ways, for example, attending to parents’ emotional needs and/or making important family decisions.

I had to look after a depressed mother when I was seven years old, I had to get her out of bed you shouldn’t be doing that when you’re seven. I was worried that she was going to kill herself.

Awareness of parental sexuality

Participants described parental infidelity resulting in their obtaining of information about their parents’ sexual behaviour. This was experienced by participants, as painful and extremely uncomfortable; a pain and discomfort which participants experienced as unknown to, or disregarded by, their parent(s).

I remember a particular row my dad said something of a sexual nature (…), some sort of reference to him in bed or something (…) and I remember feeling quite shackled about that.

Colleagues used to say, ‘your conversation is quite sexualised’ (…) and I used to think why am I so sexualised in my discussion with other people? It clearly comes from being made aware of my parents’ sexuality.

Challenges in romantic relationships

Fear of abandonment and relationship breakdown

Participants described experiencing deep and incessant fears of their romantic relationships breaking down. This experienced encompassed fears of being suddenly abandoned by a romantic partner, difficulties with trusting a romantic partner, concerns about having to overcompensate in relationships due to fears of being labelled with negative identities such as ‘damaged goods’ or ‘daddy issues’ and/or questioning the meaning, necessity and value of marriage.

I do remember being incredibly nervous that he would leave me. I just remember feeling so needy.

I wonder if I wish that I’d not found out, maybe I wouldn’t have hated men so much and mistrusted them so much.

I worry that men would think I’m damaged goods, because I’ve come from the infidelity life.

I’ve never been married, I don’t really have a desire to be (…) because I know how awful it can be if it goes wrong and you’re left.

Intergenerational transmission of infidelity

Participants explored their experiences of infidelity within their own romantic relationships. The narratives fell into two distinct categories: having been unfaithful, or having been cheated on.

It appears that the experience of having been cheated on was one which had a strong, emotional impact on participants who described it as being a difficult, world-ending experience. This experience also appeared to be directly associated with the parental infidelity, as participants described having actively hoped to avoid making the ‘same mistakes’ their betrayed parent. These participants also described the idea of being unfaithful themselves, as unfathomable; a moral issue they strongly oppose.

I would have gone back actually to my 21 year old self (…) in a relationship with someone that was unfaithful and (…) been like ‘get out’ don’t repeat the same mistakes.

I would never cheat on somebody because for me that is one of my morals. I think it’s wrong.

On the other hand, participants who had been unfaithful described their questioning of why they would do this; a confusion surrounding the lack of sense it makes to them and/or revealed feelings of deep guilt and regret.

I was unfaithful to my partner (…) and I felt absolutely dreadful for weeks afterwards.

Differentiation

The analyses elucidated the importance participants placed on differentiating between themselves and their unfaithful parent and/or differentiating between their romantic partners and their unfaithful parent.

It appeared that reflecting on how distinctly different one’s partner is, to their unfaithful parent, can serve as a reassurance for participants that they are in a solid, stable relationship, the breakdown of which, they need not fear.

He is so honest and transparent (…) he’s just worlds away from my father (…) really solid and consistent, and my dad never, ever was.

There were good times, he did remind me of my dad sometimes though (…) he very much liked sport (…) and he watched a few of the same TV programmes (…) which was always really a little bit weird.

I actually got bored which also really worries me because I’m like, oh my God! I must be like my dad in some way.

We’re completely different (…) he’s not like me, therefore I won’t be a cheater (…), I couldn’t put someone else through that.

The psychological experience

An everlasting pain

Participants explored the meanings they have attached to the magnitude of their experiences of parental infidelity and the ever-lasting nature of its consequences. As an overall experience, participants described parental infidelity as having been one of emotional turmoil encompassing: sadness, confusion, isolation, pain, fear, anger, emotional abandonment and trauma and mental health difficulties.

It caused a lot of emotional turmoil (…) I was very upset. I felt confused, isolated and (…) powerless. I remember the feeling of being so scared I’d get stress nose bleeds.

For many, many years I did actually just end up crying every single night (…) I was so depressed I couldn’t get out of bed.

That’s what caused the alcoholism: the emotional abandonment.

It sticks with me so much to this day. It was 100% a factor and the start of what became a very long road of mental health issues.

I’ll never really forget what happened, I don’t think you can. It shaped who I am as a person, without a doubt.

It’s a life-changing thing.

It was the major event of my life and it had a very very negative impact. The pain never really goes away.

The sense of self

Participants explored the influence parental infidelity has had on their sense of self; their identities, their self-esteem and their self-worth.

One dimension of this finding was that participants described feeling that the parental infidelity was a personal attack on them; a betrayal of the family as one entity, rather than solely the betrayed parent. This elicited feelings for participants of being unlovable, not good enough, being worthless and having been replaced; feelings which led to mental health difficulties and were further exasperated if the unfaithful parent had more children following his/her infidelity.

I felt like it was a personal attack, he’s my father (…) if my dad can’t love me then are other people going to love me (…) there must be something wrong with me if my dad can’t stick around at home, he doesn’t like me.

I’m kind of ashamed that I never really saw my father’s perspective on it.

She did blame us actually, ‘if you’d been better behaved, he wouldn’t have left’. It made me feel like a piece of dirt really, it made me feel worthless.

Loss: detachment and disconnection

Participants explored their experiences of loss and detachment. One dimension of this was the loss of, and detachment from, deep relational connections and the understanding of their identity as a family.

For some participants, the detachment from the unfaithful parent was an active choice, which appeared to serve as a means to detach from the negative implications of the infidelity, as a whole. One way in which this manifested itself, was by participants referring to the unfaithful parent by their first name rather than ‘mum’ or ‘dad’, or by these monikers interchangeably. For other participants, the detachment was experienced as having been rejected or forgotten by the unfaithful parent, who would only make time to connect in order to resolve the parent’s own guilt.

I absolutely disconnected from him, I was there in body but not in spirit (…) wouldn’t look at him, I wouldn’t talk to him.

… he’s only going to do things for his self-interest, he might feel better if like ‘I’m doing my daddy duties, seeing my daughter’.

The experience of detachment from deep relational connections was not restricted to the unfaithful parent, but for some participants also included the loss of their connection to the betrayed parent and/or to siblings, as participants experienced having to pick a ‘team’ between the two parents, thus losing connections with those who were not ‘teammates’.

The experience of loss also extended to other family members who had been aware of the infidelity before participants themselves, thus experienced as a further familial betrayal and to peers who participants experienced as being unable to understand or share the pain they were experiencing.

I remember feeling very disconnected from my peers at school, I remember girls being very giggly, and silly, and carefree and I just couldn’t engage with that because I had this other stuff going on that felt a lot more serious.

It completely shatters your trust in people, it puts into question, truths.

The pathway to healing

The study elucidated three factors which participants found to be pivotal in their ability to heal.

Restoration through destruction

The first factor was participants’ experiences of recognizing the positive, restorative consequences of parental infidelity. This had three dimensions. The first, was infidelity leading to resolution of a turbulent marriage, not necessarily the end of the marriage, but the turbulence within that marriage and therefore and end to participants’ experiences of witnessing parental conflict and parental distress; in its place, gaining a sense of freedom to live a happier life.

things are actually better without him, because he was grumpy (…) and self-centred. I guess there was some kind of freedom that came with him leaving.

It’s certainly been a massive learning experience, I’ve learned a lot about me and I’ve learned a lot about relationships (…) what’s healthy, what’s not healthy.

having a mum suicidal and having to get her out of bed when you’re seven (…) I do think it has made me resilient, I can cope.

Perspective: intellectualization and understanding

The second factor was the importance of participants’ intellectualizing their parents’ infidelity in order to gain some understanding of causality and an ability to empathize with the unfaithful parent. This experience had two main dimensions. The first was participants’ evolving understanding of the difficulties within their parents’ marriage which may have led to infidelity.

She found intellectual and emotional and sexual solace in another person.

I’ve accepted it, and I kind of actually understand it, I understand it he’s had health problems and he had a tough background … a tough life. I can see why he’s done it, I don’t like it, but (…) it makes sense.

Honesty and openness

The third factor was the importance of honesty and openness. Once again, this finding had multiple dimensions. The first was participants’ experiences of parents failing to be honest and open about the infidelity and what changes this may elicit within the family. This led to participants feeling confused and disorientated and was the start of many years of seeking clarity elsewhere.

The second was participants’ experiences of having been asking to maintain secrecy surrounding the infidelity, either being asked to keep information provided by the unfaithful parent, from the betrayed parent, or being asked by the betrayed parent to keep the infidelity a secret from peers within the wider circle due to fears of judgement from the community, surrounding this ‘taboo’ topic. This resulted in participants feeling hurt and offended that they were asked, by adults, to do this and/or resulted in participants having outbursts in which they reveal the infidelity and/or internalizing their emotions, one participant attributing responsibility of the development of her self-harming, to this internalization.

The first time I self-harmed was when I was nice and this was the whole ‘you can’t tell anyone’, and I was like oh my God I don’t know what to do with all my feelings. I was just like I can’t handle the emotional pain so I took it out in physical pain.

Discussion

Clinical implications

Adultification

This finding aligns itself with Burton (Citation2007) who theorized four different stages of childhood adultification. The findings suggest that it is important within individual clinical work, family or systemic therapy, to help families recognize that it is inappropriate for children to take on the role of an emotional carer for a distressed parent. Clinicians should encourage parents to maintain appropriate emotional boundaries with children and not call upon them to be carers, confidantes or ‘safety buffers’, as the study shows that for offspring, this can have multiple negative consequences, some of which may be elucidated much later in life.

In clinical work, it will be important to acknowledge that the consequences of infidelity are not restricted to the parameters of the relationship dyad and recognize that the entire family system may be impacted. Thus, it is important to facilitate a safe space in which offspring can express their emotions and do not feel these emotions need to be internalized. Clinicians should be aware that it is common for a distressed parent to become emotionally overwhelmed during this time, which might lead to parents becoming emotionally unavailable and thus, creating a space within which children feel like a burden or an added stressor for the distressed parent. These dynamics can be addressed in systemic/family therapies.

In addition, findings suggest that it is important for children, to have the extent of their distress as a result of the infidelity, acknowledged by both the betrayed and the unfaithful parent. This can be addressed in systemic/family therapies.

Further, it is important to differentiate the relationship between the parents themselves and the relationship between each parent and his/her offspring. Systemic/family therapies can facilitate this distinction and effectively highlight the fact that these two relationships are entirely separate entities and therefore it is important for offspring to feel they hold the right to respond to each parent in the way that feels authentic to them. Clinicians can help families understand that a child’s relationship with each parent should not be dependent on the child’s feelings towards, or relationship with, their other parent.

In addition, it may be effective for clinicians to hold in mind that the assuming of this role in early life, may relate to the way in which an individual responds to the distress of others, later in life, which may relate to difficulties they experience at present.

Next, the current study has found that an awareness of parental sexuality, explicit and/or implicit, can have negative consequences for a child’s emotional well-being, sexual development and relationship with one or both parents. Therefore clinicians can highlight for families that it is important to keep this topic out of children’s awareness. Where this is accidental, for example if a child overhears a conversation between his/her parents with such content, it may be helpful for clinicians to facilitate a space in which parents acknowledge that this will have been an unpleasant experience for the child.

Challenges in romantic relationships

This theme highlights the role parental infidelity can play in the difficulties adult offspring experience in their own romantic relationships. This finding provides support for earlier research which has shown that an experience of parental infidelity may relate to difficulties adult offspring experience in their endeavours to maintain healthy romantic relationships (Cramer et al., Citation2001; Nogales & Bellotti, Citation2009).

Understanding the way in which parental infidelity may relate to specific challenges can be particularly useful knowledge for clinicians working therapeutically with couples or with individuals who are presenting with relationship difficulties.

The findings suggest that it is imperative for offspring to be recognized as their own entity; differentiated from either the parent, betrayed or unfaithful, as comparisons or suggestions of resemblance, can trigger various manifestations of anxiety and concern. Similarly, it has transpired that even the sharing of very general characteristics such as enjoying watching sport on television, between adults’ romantic partners and their unfaithful parent can elicit anxiety for individuals who have experienced parental infidelity, which could in-turn elicit problems within their romantic relationships. Based on the fact that the characteristics which may trigger these concerns appear to be very general, it may remain unknown to individuals and their partners that this is serving as an elicitor of anxiety, thus this knowledge may be particularly valuable for clinicians to hold in mind.

Next, as the findings suggest that parental infidelity can lead to challenging views on marriage, it may be valuable for adults who have experienced parental infidelity, for clinicians to facilitate an open, safe therapeutic space in which they are encouraged to discuss their views on marriage, the meanings they attach to this experience and what their fears and concerns surrounding this long-term commitment may be.

In addition, regarding implications within a broader context, this research also highlights the negative consequences societal labelling such as: ‘damaged goods’ and ‘daddy issues’ can have and elucidates the value of working towards diminishing their existence in our society.

The psychological experience

The findings of this study suggest that the validation of this experience is paramount; the acknowledgement that it can be an enduringly painful trauma experience, potentially impacting various aspects of one’s life, may be a fundamental part of an individual’s process of healing. This is compatible with Lusterman (Citation2005) who suggests that parental infidelity is an experience of trauma and is likely to elicit feelings of pain, fear and confusion. Unique to this study, however, was the highlighting of the ‘ever-lasting’ pain elicited by parental infidelity and the magnitude of the implications of parental infidelity for participants’ entire lives. Therefore, a fundamental element of the therapeutic work with individuals and/or families who have experienced parental infidelity is likely to be empathy and validation of the magnitude of this experience and the long-lasting pain it can elicit.

The findings have also elucidated the influential role parental infidelity can have on a child’s loss of self-esteem. As demonstrated by the participants, this loss of self-esteem and self-worth can have serious negative implications for a child’s mental health. Thus, clinicians should hold in mind that it is imperative for children to understand that they are not one with the betrayed parent; that they are a separate entity and that their parent’s infidelity is not a personal attack nor is it a reflection of their worthiness of love; a belief which can become enacted in their own relationships. To aid this understanding and work towards ensuring children do not feel abandoned, it may be helpful, particularly in family/systemic therapies, for parents, in particular the unfaithful parent, to be encouraged to reassure their children of their love, spend time with the children to the extent to which they did before the discovery of the infidelity and endeavour to build new bonds with children; making them feel included in life changes, such as moving into a new home, or new dynamics such as moving onto a new relationship or having more children.

Moreover, findings also suggest it is important for children to understand and recognize that their parents’ behaviour is not a reflection of their character, personality or determinant of the way in which they will behave in their own relationships. Therefore, it may be important for clinicians to hold in mind that this may be a concern and therefore facilitate a therapeutic space in which this can be explored.

Furthermore, a fundamental part of the therapeutic work should be ensuring that children understand they are not to blame or responsible for the behaviour of their parent(s). It is important to ensure that parents are not blaming children due to their own emotional turmoil and for clinicians to remain aware that children may have a tendency to blame themselves and thus, to address this if it appears these dynamics are arising.

In addition, it is crucially important for clinicians to recognize that for children, the experience of parental infidelity can lead to multiple simultaneous losses, despite this perhaps not being clear for others to recognize, and may take time and therapeutic work, to process.

The pathway to healing

This master theme highlighting three specific elements which participants described as fundamental to their process of healing was a unique finding of the current study. This theme elucidates the fact that regardless of how the positive implications of parental infidelity may manifest themselves in an individual’s life, it may be a crucial piece of the puzzle when it comes to the process of healing. Whilst parental infidelity can be a traumatic time, the current study suggests that there may be restorative elements of the experience and it may be important, particularly for clinicians, to understand, that facilitating a space to recognize, acknowledge and reflect on these elements may be an effective way to re-frame this experience for clients.

Furthermore, it may be helpful for clinicians to encourage clients to intellectualize the infidelity; to explore thoughts about why the unfaithful parent may have behaved in this way. This certainly does not in any way suggest that offspring should avoid the affective response elicited by the infidelity, but rather, to take various perspectives in order to gain a deeper insight which may aid the process of understanding and acceptance to some extent.

In addition, the current study highlights how painful and traumatic having to maintain topic-avoidance and secrecy and thus internalizing emotions, can be for children and as a result, the negative implications this can have for their mental health. Therefore, it may be important for clinicians to hold in mind that honesty is fundamental. Family/systemic therapies may be particularly valuable here; by creating a therapeutic space in which open, honest conversations about the infidelity and its potential subsequent ramifications can be had, without imposing rules on children about keeping secrets or upholding topic avoidance. This can relieve children of negative emotions and protect children from some of the negative implications of the absence of honesty. It is also important to note, that this honesty and openness should be thought-out, to ensure it is always in the best interest of the children and not being used as a tool to relieve the parent(s) of distress or to manipulate children’s loyalties toward either parent.

Limitations of the current study and suggestions for future research

The findings from this study have been derived from a small sample size, therefore the generalization of the findings and/or the making of broader claims need to be approached with caution.

Next, it may be worth noting that all participants had some form of educative experience in Counselling, Psychology or research in the Social Sciences field. This may have increased participants’ willingness to discuss the topic or partake in psychological research, or further, may have increased participants’ knowledge of Counselling and Psychotherapy and/or the emotional processing of traumatic events, which may have influenced the way in which they were able to discuss and reflect upon their lived experience of parental infidelity. Thus, in future, researchers could perhaps utilize a stratified sampling method in order to deliberately ensure a more representative sample of individuals who have experienced parental infidelity.

Moreover, the IPA methodology has been critiqued for being highly dependent on participants’ use of language; their ability to articulate the meanings they have attached to their lived experiences (Willig, Citation2001). Therefore, there may have been elements of participants’ experiences which they were unable to articulate. Thus, this research could perhaps be extended by adopting multiple methodological approaches; triangulating the parental infidelity phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

Informed written consent to take part in the research was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. Data have been anonymized and such alterations have not distorted the scholarly meaning. This study has been approved by City, University of London Research Ethics Committee, [PSYETH (P/L) 16/17/ 40].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allport, G. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

- April, M., & Schrodt, P. (2018). Person-centered messages, attributions of responsibility, and the willingness to forgive parental infidelity. Communication Studies, 70(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2018.1469525.

- Baxter, L. A., & Wilmot, W. W. (1985). Taboo topics in close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407585023002

- Blow, A. J., & Hartnett, K. (2005). Infidelity in committed relationships II: A substantive review. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01556.x

- Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., & Krasner, B. (1986). Between give and take: A clinical guide to contextual therapy. Brunner/Mazel.

- Brann, E. T. H. (1991). The world of imagination: Sum and substance. Rowman & Littlefield.

- British Psychology Society. (2014). Code of ethics. http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/documents/code_of_ethics_and_conduct.pdf.

- Brown, E. (2001). Patterns of infidelity and their treatment. Routledge.

- Burton, L. (2007). Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations, 56(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x

- Cano, A., & O’Leary, K. D. (2000). Infidelity and separations precipitate major depressive episodes and symptoms of nonspecific depression and anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 774–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.774

- Cramer, R. E., Abraham, W. T., Johnson, L. M., & Manning-Ryan, B. (2001). Gender differences in subjective distress to emotional and sexual infidelity: Evolutionary or logical inference explanation? Current Psychology, 20(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-001-1015-2

- Emery, R. E. (1994). Renegotiating family relationships: Divorce, child custody, and mediation. Guildford Press.

- Fenigstein, A., & Peltz, R. (2002). Distress over the infidelity of a child’s spouse: A crucial test of evolutionary and socialisation hypotheses. Journal of the International Association for Relationship Research, 9(3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00021.

- Gadamer, H. (1990). Truth and method (2nd ed.). Crossroads.

- Giorgi, A., & Giorgi, B. (2003a). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhodes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 243–273). American Psychological Association.

- Gottman, J. M. (2011). The science of trust: Emotional attunement for couples. WW Norton.

- Hargrave, T. D., Jennings, G., & Anderson, W. (1991). The new contextual therapy: Guiding the power of give and take. Brunner-Routledge.

- Havlicek, J., Husarova, B., Rezacova, V., & Klapilova, K. (2011). Correlates of extra- dyadic sex in Czech heterosexual couples: Does sexual behavior of parents matter? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(6), 1153–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9869-3

- Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. Blackwell.

- Husserl, E. (1927). Phenomenology. For Encyclopaedia Britannica (R. Palmer, Trans. and revised). https://phenomenologyinstitute.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/husserl_edmund__psychological_and_transcendental_phenomenology_and_the_confrontation_with-heidegger.pdf.

- Husserl, E. (1977). Phenomenological psychology: Lectures, summer semester (J. Scanlon, Trans.). Martinus Nijhoff. (Original work published 1925)

- Jones, S. M., & Guerrero, L. A. (2001). The effects of nonverbal immediacy and verbal person centeredness in the emotional support process. Human Communication Research, 27(4), 567–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2001.tb00793.x

- Kawar, C., Coppola, J., & Gangamma, R. (2019). A contextual perspective on associations between reported parental infidelity and relational ethics of the adult children. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(2), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12331

- Kessel, D. E., Moon, J. H., & Atkins, D. C. (2007). Research on couple therapy for infidelity: What do we know about helping couples when there has been an affair? In P. R. Peluso (Ed.), Family therapy and counseling. Infidelity: A practitioner’s guide to working with couples in crisis (pp. 55–69). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kvale, S. (1996b). Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative research interviewing. SAGE.

- Larkin, M., Eatough, V., & Osborn, M. (2011). Interpretative phenomenological analysis and embodied, active, situated cognition. Theory & Psychology, 21(3), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354310377544

- Larkin, M., & Thompson, A. R. (2012). Interpretative phenomenological analysis in mental health and psychotherapy research. In D. Harper & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners (pp. 101–116). Wiley.

- Larkin, M., Watts, S., & Cliffton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp062oa

- Lewis, J., & Graham, J. (2007). Research participants’ views on ethics in social research: Issues for research ethics committees. Research Ethics, 3(3), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/174701610700300303

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Qualitative research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Lopez, K. A., & Willis, D. G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretative phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14(5), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304263638

- Lusterman, D. D. (2005). Helping children and adults cope with parental infidelity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(11), 1439–1451. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20193

- McIntyre, R., & Smith, D. W. (1989). Theory of intentionality. In J. N. Mohanty & R. M. Williams (Eds.), Husserl’s phenomenology: A textbook (pp. 147–179). University Press America.

- McLeod, J. (2015). Doing research in counselling and psychotherapy (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Moller, N. P., & Vossler, A. (2015). Defining infidelity in research and couple counselling: A qualitative study. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 41(5), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2014.931314

- Moran, D. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge.

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

- Nogales, A., & Bellotti, L. G. (2009). Parents who cheat. Health Communications.

- Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialects of disclosure. SUNY Press.

- Platt, R. A. L., Nalbone, D. P., Casanova, G. M., & Wetchler, J. L. (2008). Parental conflict and infidelity as predictors of adult children’s attachment style and infidelity. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701236258

- Ponterro, J. (2005). Qualitative research in counselling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and Philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126

- Reid, K., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2005). Exploring lived experience. The Psychologist, 18(1), 20–23. https://thepsychologist.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/articles/pdfs/0105reid.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA3JJOMCSRX35UA6UU%2F20210804%2Feu-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20210804T094950Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=Host&X-Amz-Expires=10&X-Amz-Signature=0c5f096755d426080221dc3c231e117044fdf9e73465c07de3727a496611fcaa

- Schleiermacher, F. (1998). Hermeneutics and criticism and other writings (A. Bowie, Trans.). CUP. (Original work published 1838)

- Schmidt, A. E., Green, M. S., Sibley, D. S., & Prouty, A. M. (2016). Effects of parental infidelity on adult children’s relational ethics with their partners: A contextual perspective. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy, 15(3), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2014.998848

- Schmitt, R. (1959). Husserl’s transcendental-phenomenological reduction. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 20(2), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.2307/2104360

- Schrodt, P., & Afifi, T. D. (2007). Communication processes that predict Young adults’ feelings of being caught and their associations with mental health and family satisfaction. Communication Monographs, 74(2), 200–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750701390085

- Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology & Health, 11(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400256

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. SAGE.

- Smith, J. A., Harre, R., & Langenhove, V. L. (1995). Rethinking methods in psychology. SAGE.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. British Journal of Pain, 9(1), 41–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714541642

- Snyder, D. K., Baucom, D. H., & Gordon, K. C. (2008). An integrative approach to treating infidelity. The Family Journal, 16(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480708323200

- Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Wadsworth Publishing.

- Stewart, C. (2017). Attitudes, attachment styles, and gender. implications on perceptions of infidelity. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3172. https://doi.org/10.34917/11889756

- Thorson, A. R. (2019). Investigating the relationships between unfaithful parent's apologies, adult children's third party forgiveness and communication of forgiveness following parental infidelity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(9), 2759–2780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518799978

- Thorson, R. A. (2009). Adult children’s experiences with their parent’s infidelity: Communicative protection and access rules in the absence of divorce. Communication Studies, 60(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970802623591

- Thorson, R. A. (2014). Feeling caught: Adult children’s experiences with parental infidelity. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 15(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/17459435.2014.955595

- Thorson, R. A. (2017). Communication and parental infidelity: A qualitative analysis of how adult children cope in a topic avoidant environment. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 58(3), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2017.1300019

- Vangelisiti, A. L. (1994). Family secrets: Forms, functions and correlates. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(1), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407594111007

- Vangelisti, A. L., & Caughlin, J. P. (1997). Revealing family secrets: The influence of topic, function and relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14(5), 679–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407597145006

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(148). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Weiser, D. A. (2013). Family background and propensity to engage in infidelity: Exploring an intergenerational transmission of infidelity [Doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno].

- Weiser, D. A., Weigel, D. J., Lalasz, C. B., & Evans, W. P. (2017). Family background and propensity to engage in infidelity. Journal of Family Issues, 38(15), 2083–2101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15581660

- Willig, C. (2001). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Open University Press.

- Willig, C. (2012). Qualitative interpretation and analysis in psychology. Open University Press.

- Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology (3rd ed.). Open University Press.

- Zahavi, D. (2003). Husserl’s phenomenology. Stanford University Press.

Appendix

Interview schedule

What prompted you to take part in the study?

Could you tell me a little about your childhood and adolescence – what was growing up like for you?

Can you tell me about your experience of parental infidelity?

What was your initial reaction?

Do you feel there has been a change in how you feel about your experience over time? (If so, how?)

Do you feel your experience has changed you in any way?

Imagine your mother/father had committed the infidelity instead of your mother/father (delete as appropriate), would that feel different?

Are there positive and negative aspects of your experience?

Looking back now, what, if anything, would you say to that [child/adolescent/age dependent on when infidelity was discovered]?

If you were the interviewer, what would you have asked, which I haven’t asked you?