ABSTRACT

This study examined the expectations of expectant first-time parents on coparenting in a Finnish two-parent family. Thirty expectant couples were individually interviewed (N = 60) during the third trimester of pregnancy. The semi-structured interviews focused on participants’ expectations and hopes on future coparenting. Thematic analysis revealed that the expectant first-time mothers and fathers saw coparenting as multidimensional. They talked about coparenting in terms of 1) division of labour issues, 2) management of family dynamics, 3) childrearing agreement, 4) coparental support, and 5) learning and developing. Thus, the expectant couples hoped for a coparenting relationship in which both parents become experts in parenting. Ideally, coparenting involves mutual respect, equality, flexibility, and consideration for the other parent. Coparenting was also seen as an opportunity to grow and learn together in the parenting and coparenting process, e.g. finding one’s own way both as a parent and as a couple and giving space to the other parent. While the expectant first-time parents expressed optimistic hopes and ideals about coparenting, they also raised concerns and challenges regarding interparental collaboration. The findings are discussed from the viewpoint of further elaborating and developing Feinberg’s (2003) model of the internal structure of coparenting.

Introduction

Coparenting describes the ways how parents relate to each other in the role of parent (Feinberg, Citation2003), and work together sharing their child-raising responsibilities (Feinberg, Citation2002; Hock & Mooradian, Citation2013). Research (Durtschi et al., Citation2017; Feinberg, Citation2003; McHale et al., Citation2004) has demonstrated that entering parenthood and combining parental and work roles gender equally is much easier if the parents work together as a team, sharing duties, supporting each other, agreeing about childrearing and planning family life together. However, the degree of equality in parenting roles is formed according to the participants influenced by their social and cultural context (Feinberg, Citation2003). Furthermore, families are not static, but change over time, owing partly to individuals’ developmental processes and between-family differences (Feinberg, Citation2003; Kotila & Schoppe-Sullivan, Citation2015). Some researchers (Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017) suggest that a coparenting relationship starts already before childbirth in terms of early representations and expectations. Parents’ beliefs, expectations, values, and wishes nevertheless influence the construction of coparenting (Feinberg, Citation2003).

Utilizing interviews with 30 couples during the third trimester of pregnancy, this qualitative study investigated the meanings expectant first-time parents attribute to coparenting, including the elements comprising coparenting, and their expectations of the coparenting relationship. The study was conducted in the social and cultural context of Finland, a country with a relatively high level of gender equity where social policies influence individuals’ orientation to work and family formation. (Miettinen et al., Citation2011). In Finland, age at first birth and unmarried cohabitation have both increased over the past decade (OSF, Citation2020). In 2020, the mean age of first-time mothers was 29.7 years and that of fathers 31.6 years (OSF, Citation2021). The findings of this study are also used to further elaborate Feinberg’s (Citation2003) widely used model of the internal structure of coparenting. While many researchers have supported the model, others have challenged some of its elements (Feinberg et al., Citation2012). Kotila and Schoppe-Sullivan (Citation2015) have called for researchers to further develop coparenting theory to gain a deeper understanding of all aspects of coparenting.

This study aimed to provide new information on the early stages of coparenting. The study draws on the family systems and life course theory (Elder, Citation1998), according to which the birth of a firstborn is considered a significant stage in the life course of individuals in which, in their social contexts, they move through time, relationship and interactions with each other. The family system theory (FST) sees coparenting as the centre around which family processes start and develop (Weissman & Cohen, Citation1985). The FST defines a family as a dynamic, ever-changing system of interdependent individuals (Allen & Henderson, Citation2017). The transition from couplehood to parenthood carries with it a more intense and conscious relationship between the partners (Grunow & Evertsson, Citation2021), in which new parents also face challenges in parental equality in terms of their child-caring responsibilities (Lévesque et al., Citation2020). Increasing pressures on family and working life partly explain why parents have difficulties in starting a family (Mills et al., Citation2011) or end up in divorce or separation during the first years of parenthood (Pruett et al., Citation2014). Understanding different prenatal coparenting expectations could help support new mothers and fathers in working together as parents and mitigate the risk of family dissolution during the transition to parenthood. Spouses’ expectations and visions of a coparenting relationship are often optimistic, but they seem to shape postpartum experiences in the face of major changes in the family system (Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017). Thus, knowing what each parent thinks is important when considering families and development.

Preparing for new parental roles, expectations for a new stage of life

Becoming a parent and preparing for the birth of the first child is a major developmental transition in adulthood. According to the life-course theory, this transition is characterized by dynamic interaction between individuals and their families (Allen & Henderson, Citation2017), and one where individuals make meanings in their social contexts (Bengtson & Allen, Citation1993). The transition to parenthood is manifested in the gender gap in parenting, which reflects cultural expectations, norms, and ideals ‒ sometimes contradictory ‒ that are related to mother- and fatherhood (Allan, Citation2008; Milkie, Citation2011). During pregnancy, the baby is mentally represented in the partners’ minds, and the couple live through and seek to reconcile various ideals related to their family roles and responsibilities (Allan, Citation2008; Dew & Wilcox, Citation2011) and their future as a family. Successful preparation for this new stage of life leads to individuality in psychological processes and perceived experiences of adequate parenting (Pinto et al., Citation2016).

Expectant parents often have optimistic expectations about parenthood despite the many challenges presented by this transition (Harword et al., Citation2007; Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017). Sevón (Citation2012), for example, reported that women talked optimistically and positively about their partner, relationship, commitment, and future parental involvement during pregnancy. Harword et al. (Citation2007), in turn, found that women’s perceptions of their relationship with their partner and confidence in their ability to care for their infant affected their level of optimism about their parenting role. Less research has incorporated fathers’ prenatal perceptions. However, new fathers face expectations of active fatherhood nowadays, even if most new mothers remain the primary caregivers of their newborn baby (Olsavsky et al., Citation2020).

Previous research (Riggs et al., Citation2018) has found that prenatal expectations influence postnatal experiences of parenthood. Expectant couples’ prenatal perceptions of their cooperation skills as well as family relations are closely reflected in the postnatal quality of parenting (Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017). Couples must learn, share, and negotiate new things: their responsibilities and tasks, family routines, work and family roles, and childrearing ideals (see Allan, Citation2008). The way new parents navigate this stage has important implications for the wellbeing of the whole family (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Citation2016). Some families may operate along traditional family lines, while others may try to share caretaking and household duties more equally. After childbirth, according to the family systems theory, family relationships and patterns become unstable for a while (Allen & Henderson, Citation2017). Lévesque et al. (Citation2020) noted that since finding a balance between one’s various roles and identities (e.g. parent, partner, professional) is challenging, it is beneficial to share tasks, divide parental leave and view parenthood in a gender-neutral way, thereby increasing the parents’ awareness of possible difficulties and solutions. Furthermore, in their relationship, parents can also learn by experience and adapt their behaviour (McHale et al., Citation2004).

Dimensions of coparenting

Coparenting is an integral aspect of family life, which affects parenting experiences, children, and parental roles (Feinberg, Citation2003). Coparenting consists of much more than adult's taking responsibility for the upbringing of a child (McHale, Citation1995). Coparenting can be a source of support for parents, enhancing the wellbeing of the child and the whole family (McDaniel et al., Citation2017). Effective coparenting between spouses might also ease the transition to parenthood (Durtschi et al., Citation2017; McHale et al., Citation2004; Van Egeren, Citation2004). Coparenting has also been highlighted as a key process in adult development (McHale et al., Citation2004; Van Egeren & Hawkins, Citation2004).

According to Feinberg’s (Citation2003) model, coparenting comprises four domains: childrearing agreement, division of labour, support versus undermining, and joint family management. The outcomes of each component influence the success of parental adjustment, the interparental relationship, parenting, and child adjustment. A childrearing agreement consists of mutually accepted rules and behavioural expectations regarding the child’s safety, emotional needs, and couple’s moral values. Division of labour refers to the distribution between parents of the daily routines involved in childcare, including household tasks and responsibilities. (Feinberg, Citation2003; Feinberg et al., Citation2012). Support encompasses positive behaviours that help the other partner’s parenting efforts, such as seeing them as a competent parent and acknowledging and respecting their contribution (Feinberg, Citation2003; McHale, Citation1995). Undermining is the opposite of support, and refers to negative criticism, blame or disparagement (Feinberg, Citation2003) behaviours which can lead to competitive coparenting (McHale, Citation1995). Joint family management (called joint management of family dynamics by Feinberg et al., Citation2012) refers to family interaction, where the parents’ primary responsibility is controlling their mutual interparental behaviours and communication, as these affect their parenting and children. Problematic communication and conflicts are risky as they might disturb the balance and affect interaction in the whole family (Feinberg, Citation2003; Feinberg et al., Citation2012). Feinberg et al. (Citation2012) subsequently added the further dimension of coparenting as parenting-based closeness, (termed coparenting solidarity by Van Egeren & Hawkins, Citation2004), which refers to shared joy in the child's development and the experience of working together as a team.

Coparenting is significantly associated with the couple relationship and parenting experiences (Sheedy & Gambrel, Citation2019). Couples’ positive representations of their future coparenting relationship during prenatal triadic interactions may predict better postpartum functioning (Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017). Van Egeren (Citation2004) pointed out that the quality of the marriage before childbirth sets the stage for coparenting. Couples who are satisfied with their relationship are also likely to experience parenting satisfaction. Moreover, if mothers’ experience of the division of childcare and housework meets their expectations, they are more satisfied with the coparenting relationship. If these expectations are not met, coparenting may be experienced as less supportive by mothers than fathers. Nevertheless, higher expectations of shared childcare are related to greater equality in childcare in parenthood (Almqvist & Duvander, Citation2014).

Previous studies have also demonstrated differences between mothers and fathers in coparental behaviours and dynamics. Several studies (Hock & Mooradian, Citation2013; Murphy et al., Citation2017; Olsavsky et al., Citation2020; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Citation2008) have found that the quality of coparenting influences parents’ behaviours. For example, a strong coparenting relationship is associated with lower parental negativity and more positive parent-infant interactions (Hock & Mooradian, Citation2013). Murphy et al. (Citation2017) found that fathers support their partners more, but mothers are more involved in parental decision-making. It is noteworthy that the encouragement of fathers by mothers increases father involvement with infants and positively influences coparenting quality, although only when mothers’ criticism of fathers is minor (see Schoppe-Sullivan et al., Citation2008).

International research on coparenting has burgeoned over the past few decades, and the coparenting theory has increasingly focused on describing the phenomenon during the child’s early years. Fewer studies have approached coparenting using a qualitative design with traditional coparenting partners (Kotila & Schoppe-Sullivan, Citation2015). Even in the Nordic countries, despite the increased interest in shared and equal parenting styles, coparenting research remains very limited. This qualitative study focuses on the period preceding the birth of the child and investigates first-time parents’ prenatal expectations about coparenting, interviewing couples each partner individually. The study is part of an international research project (Learning to coparent: A longitudinal, cross-national study on construction of coparenting in transition to parenthood) aimed at finding out how coparenting develops in the transition to parenthood among first-time parents.

This study

The aim of this qualitative study is to add knowledge on the early stages of coparenting with particular focus on the meanings attributed to coparenting by expectant first-time parents. According to Feinberg (Citation2003), the development of the coparenting relationship has not been adequately researched. In identifying this process during the transition to first-time parenthood, we think that it is important to start from the time before childbirth. Previous studies (Murphy et al., Citation2017; Olsavsky et al., Citation2020) have also found that differences between mothers’ and fathers’ coparenting relationship dynamics and behaviour influence the quality of coparenting. Therefore, we compared mothers’ and fathers’ expectations about their coparenting relationship. The research questions were 1) What expectations of coparenting are described by expectant first-time parents? and 2) What elements of coparenting can be identified from their descriptions? The findings identified from the data were compared with Feinberg's (Citation2003) model of the internal structure of coparenting.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 30 expectant heterosexual married or cohabiting couples (N = 60 individuals). The purposive sampling protocol comprised Finnish-speaking parents expecting their first child and living together at the time of recruitment. Mean length of relationship was 7 years (range 1–15 years). One-fifth of the couples were cohabiting and the remainder married. Mean participant age was 30.5 years (range 23–42 years for fathers and 23–39 years for mothers). Participants’ socio-economic characteristics are listed in . Participants were mostly highly educated meaning that 70% of the men and more than 80% of the women had at least a bachelor’s degree.

Table 1. Participantś characteristics during pregnancy.

Procedures

To participate in the study, couples had to be expecting their first child. The data were gathered from semi-structured individual interviews (N = 60) conducted during the third trimester of pregnancy during the year 2020. Recruitment for the study was implemented via advertisements in maternity health clinics in four Finnish municipalities. Parents were also recruited via virtual family classes where the first author briefly advertised the study. Participants were recruited as a part of a larger longitudinal, cross-national research project focusing on the development of coparenting throughout the transition to parenthood and the drivers and barriers in the family, community, and larger society and culture enhancing or impairing coparenting. The present couples will be followed until their child reaches the age of one and a half years. According to the guidelines of the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity (2012), the project was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Jyväskylä.

Due to the corona pandemic, the interviews were conducted via a video link (n = 46) or by telephone (n = 14). Participants performed the online or phone interviews independently of their partner. To avoid the effects of spouses influencing each other (Daly, Citation2003), partners were interviewed individually and consecutively on the same day. The first author conducted 44 of the 60 interviews. The remaining interviews were conducted by other researchers of the project. The researchers observed no appreciable difference between the phone and video methods in their ability to build rapport with the participants. The interviews lasted for 35–70 min.

Participation was voluntary. Before giving their consent, all participants were informed about the study, its purpose, their rights as participants, privacy, and told that they would be kept informed about progress of the research. Before beginning the interview, participants were informed about confidentiality, audio recording, data security, and anonymization. The semi-structured interviews comprised three main themes: 1) current life situation (work, home responsibilities) e.g. ‘How do you currently share your home responsibilities with your partner?‘ 2) expectations for coparenting (cooperation, support, division of labour, use of parental leave) e.g. ‘How would you wish your cooperation as parents to be like when the baby is born?’ 3) supporting and other people’s meaning on coparenting (social network, services) e.g. ‘Thinking about the way your own parents working together as parents, would you like to follow their example or do something differently?‘ At the end of the interview, the participants were sent, via email, a link to a short online questionnaire on background factors and their present life situation. The data collection aimed at reaching diversity and qualitative richness. After 20 couple interviews, no notable new meanings were identified. However, due to the longitudinal research design and possible attrition, the data collection was continued until 30 couples had been interviewed. Couples were rewarded with gift cards for 20 euros for their participation.

Data analysis

All the interviews were voice-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions were pseudonymized for the analyses. The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), which is a systematic and structured way to code and thematically organize data (Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017) and to view the phenomenon more broadly. The analysis was a combination of inductive and abductive approaches (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) utilizing all the interview data. The Atlas.ti software programme (Silver & Lewins, Citation2014), was used in organizing and categorizing the qualitative data.

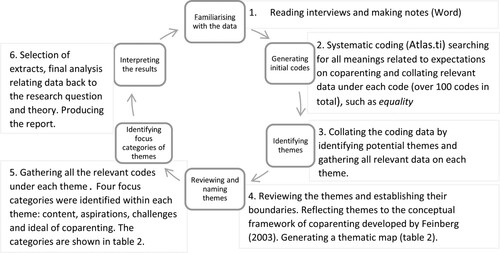

Thematic analysis process was conducted in six phases, as described in . The approach to coding was primarily data driven, although the initial understanding of coparenting was influenced by theoretical background. Hence, the interpretation process and ways of seeing patterns were central to the analysis. The principal researcher promoted the first three phases of the analysis by familiarizing herself the data, generating codes and identifying themes in the interviews. Open coding was used, meaning that the codes were developed and modified during the process. Due to the broad research question, every data segment was coded from the perspective of coparenting expectations. In phase four, the analysis switched to abductive when reviewing, naming, and identifying the boundaries of each theme. Themes were compared to the conceptual framework of coparenting developed by Feinberg (Citation2003): four of the themes corresponded to Feinberg’s domains. A fifth important theme on coparenting expectations was also identified. collates all the relevant codes and extracts under the five themes. In this process, four focusing categories were identified within the themes: content, aspirations, challenge and a coparenting ideal. The table was constructed based on these categories. Finally, the results were interpreted, e.g. the results for mothers and fathers were compared.

Table 2. The five components of coparenting expectations.

Results

Five overarching themes and four categories were identified from the data. The themes describe the components of coparenting, which were refined according to the four categories. The analysis of the interviews revealed that the expectant first-time mothers and fathers saw coparenting multidimensionally. Participants characterized their coparenting expectations as: 1) division of labour issues, 2) management of family dynamics, 3) childrearing agreement, 4) coparental support, and 5) learning and developing. presents descriptions of these components according to the four categories. These are 1) content, 2) coparental aspirations, 3) concern or challenge, and 4) ideal of coparenting. Below, the results are first presented component by component in the study participants’ voices. The outcome is then compared to Feinberg’s (Citation2003) model of coparenting, creating a new model of coparenting components based on the present interview data. The sources of the verbatim extracts are as follows: EF = expectant father, EM = expectant mother plus their interview number.

Division of labour issues

The expectant first-time parents’ hopes and expectations for interparental cooperation included the issues of the division of labour related to baby-care and division of duties and responsibilities involved in childcare and household tasks. The majority of the participants talked about the participation and attendance of both parents, aimed at fairness in the sharing of duties and childcare when both are working at the same time or alternating in caring for the baby. Some expectant parents hoped to assign fixed parental roles in which the responsibilities of each parent are defined. Most of the participants wished for flexibility in the division of labour, as this was seen as reducing conflicts. Mothers, especially, wished that their spouse would also be able to feed the child.

Plans for the division of parental leave were raised as a factor affecting the division of labour. The participants expressed a desire to share parental leave in some way. They usually talked about planning it so that the mother would be with the child during the first six months in order to breastfeed the baby. The father would then stay home with the baby for the same or a shorter length of time. Most parents were interested in the equal division of parental leave and highlighted both parents’ possibility to participate in parental leave and working life. However, half of the mothers still were willing to undertake a larger share of childcare. Many fathers, in turn, spoke of arranging their holidays so that the whole family would have plenty of time together during the first few postnatal months. As one expectant father stated:

EF6: ‘We do have quite similar ideas in many respects, I mean we’re seriously looking forward to the baby and both want to stay home, and even now I left some summer holidays for later … so that we can keep our heads those couple of months first and see how it goes and then plan … and I could imagine my wife also says we do it together and share tasks equally and give both a chance to be with the baby, but both should also have a chance for, say, career progress and work.’

EM33: ‘My husband wants to stay at home and it’s important to him that he gets to be with the child, and we've thought to share this infancy as equally as possible … he already sees himself as an equal parent and not as some kind of helper, and I think it’s really great, but perhaps, briefly, what we’ve thought is that we’ll aim for as equal and fair parenting as possible.’

Management of family dynamics

The majority of the expectant first-time parents discussed interaction and communication regarding the interparental relationship. Both fathers and mothers considered discussion and negotiation important and meaningful for effective cooperation. The participants agreed that making joint plans and decisions about childrearing and family life sometimes leads to disputes and demands the ability to compromise. The main goals of good interparental cooperation were responsibility and commitment to family life by both parents and their working together to achieve work/family balance.

EF60: ‘I mean we could experience those things together in a way for the first time, such as going to the child health clinic or changing nappies, but she is such that she might still like to take care of this baby more than I; anyway, we’ve talked about this so that we’ll try to find some balance to it.’

EF50: ‘ … some sort of dynamic changes when two become three and, in a way, life’s priorities perhaps change: earlier you could perhaps think that when you make some important decisions, you always think of it from your partner’s perspective and weigh it again, but in future this little child cuts in and you somehow consider things from the baby’s perspective. And I’d believe it of course changes the dynamics radically, in a way it can be a strengthening and uniting factor in a relationship, so that I could see it as another important shared thing.’

Childrearing agreement

Expectant first-time parents hoped for a consensus on childrearing and childcaring issues. Most of the couples had discussed these issues during pregnancy. Their childrearing agreements focused on unanimity on mutual goals, values, and behavioural expectations. They hoped both parents would have similar ideas about how to behave and proceed in matters concerning the child. The goal was for both parents to become experts in parenting. The participants talked about playing by the same rules in childrearing tasks. These rules would be based on joint discussions and decisions, as described in the next two extracts:

EM19: ‘It’s clear, I hope, we’ve already discussed how we, more or less, intend to bring up our child and make them good human beings, and that we both then have about similar rules so that the child needn’t be confused because one says this and the other says that.’

EM11: ‘When they say that a little baby understands or that when you are consistent and act in similar ways, a child might feel somehow safe; and when we, so to say, pull together and our cooperation as a couple works, of course, such seamlessness with no conflicts among ourselves, and when we have clear rules, means that neither of us needs to feel that we are in a position different from the other’

The participants shared their concerns about childrearing disagreements. For example, one first-time father pointed out that different experiences in their families of origin could affect spouses’ views on childrearing issues and trigger interparental conflict. Sleep deprivation was also further factor that could change behavioural patterns with the child. Family life would be smoother if both parents had time and energy in everyday life. The ideal and value of a childrearing agreement was seeing the child as the priority.

Coparental support

The expectant first-time parents hoped for interparental support, both emotional and practical. Participants expected the spouses to listen, understand, and feel sympathy for each another. Showing consideration for the other parent was seen as the mainstay of coparental support. They also discussed the importance of giving and receiving encouragement and positive feedback when caring for the baby and ‘taking the leap into their new world’ as one expectant mother expressed it. Even the equality appeared to be a value strongly held by the participants: almost half of the first-time mothers and fathers described their somewhat different roles how they would support their partner in the first few postnatal months. Mothers intending to breastfeed saw support from the father as crucial. Fathers were also expected to provide support in other areas like preparing meals and other household tasks. However, helping and doing for the other was the most common form of practical support mentioned by all participants. Additionally, expectant fathers hoped the spouses would share their knowledge on childcare and advise each other, as described by one expectant father:

EF32: ‘It’s certainly so that a mother spends much more time with a child especially in the early days, and already in that time she gains much more experience of childcare … so that when we start balancing childcare, it’s certain – as long as she doesn’t keep any secrets about childcare – that she advises and gives instructions on how the child reacts if I don't have experience of every situation at that point.’

EM25: ‘I certainly hope we’d manage to consider each other’s energy level and coping and remember to ask how the other one is doing or if one of us needs a nap … if one of us then takes more responsibility for a moment, so that the other gets some rest … or ask if the other one is hungry and then bring or make some food … that we’d manage to take each other into account also there and remember to thank each other even for little things and be polite to each other … but I believe we certainly have all the chances to reach this.’

Learning and developing

Another area raised by the expectant parents was related to learning and growing together as parents. Many participants saw having a child as a mutual project and site for growth on both the individual and couple-relationship level. The first few months would be dedicated to practice and the mutual learning of something new together, not only about childcare, but also about each parent’s personal characteristics, including impatience and susceptibility to stress in the face of challenges. Good discussion styles were seen as promoting collective learning. The early months were also seen as a rewarding time, as described by this expectant father:

EF18: ‘Hmm, well, certainly fulfilling, I’d like it to be sort of educational and such that both of us would have a chance for these great experiences and amazing situations and would learn through this process of bringing up a child and take responsibility for it together.’

Many participants said that they want to learn together as a couple and find their own ways of caring for the child and home, meaning that they don’t have to take patterns of parental roles outside their family. Instead, they wanted to develop their individual approaches, doing things with the child in their own way, and not necessarily in the same way as their spouse. Women, especially, emphasized that they wanted to develop their own parenting style and that this also applied to their spouse. Furthermore, giving oneself, and especially the father, space as a parent appeared to be important to the women in this study. Some of the expectant mothers (and fathers) mentioned some women’s tendency to control childcare and spoke openly about what they want to avoid when ‘hormones take over’. They were aware of possible role as a gatekeeper, which could challenge or even threaten coparenting, as this first-time mother explained:

EM15: ‘When the baby’s born, if I become a mother that doesn’t dare let the father take care of the child, or if I get such strong surges of hormone that, in a way, letting even the father take care of the baby becomes somehow hard or overcontrolling … so, I’ve said that if this happens, naturally people are allowed to tell me about it, but then of course – if I’m having a terrible attack of hormones – I don’t know if it helps at all … but we’ve talked it’s kind of seen as a threat to this coparenting..’

Comparison with Feinberg’s (2003) model

These five overarching components identified from the interview data were compared to the components in the model of coparenting by Feinberg (Citation2003). 1) Division of labour issues (named division of labour by Feinberg) gave frames to parental roles and sharing of duties and responsibilities. In this study, the expectant parents emphasized the attendance and participation of both parents, flexibility, fairness of sharing, including arrangements for parental leave. Feinberg (Citation2003) states that the degree of flexibility is a potentially important factor in how parents manage the division of labour. 2) Management of family dynamics (named joint family management by Feinberg) related to interactions between parents where the child unites parents to a family. The expectant parents underlined the importance of responsibility and commitment to family life and team working. Feinberg emphasizes that parents are responsible for controlling their behaviour and communication with each other. Prenatal expectations were also targeted responsibility concerning the child where both parents are affecting their behaviour. In line with Feinberg, this component consists of interparental discussions, making plans and decisions, and striving for balance when working together as parents. 3) Childrearing agreement. This term remains the same as in Feinberg's model. During pregnancy, expectant parents wanted to plan mutual goals and similar rules on the childrearing issues on the assumption that both partners would become experts in parenting. Consensus on childrearing issues promotes trust in the other spouse’s behaviour with the child. In line with Feinberg’s earlier observation (Feinberg, Citation2002), findings of this study also suggest that differences in parents’ family of origin could be a challenge in negotiating a childrearing agreement. 4) Coparental support (named support and undermining by Feinberg), refers mostly to each parent’s expectation of postnatal support by the other parent. Helping and doing for one’s spouse was the most commonly cited form of support. Support was seen as emotional as well as practical. The participants’ talk did not include undermining: instead, the participants hoped that the division of labour would not be subject to close accounting or analysis. This more closely resembles McHale’s (Citation1995) notion of competitive coparenting. 5) Learning and developing were identified from the data and did not correspond to any component in Feinberǵs model. According to prenatal expectations, first-time parents see parenting as an opportunity to develop that is a process for themselves both individually and together. The expectant parents wanted to work and learn together with their firstborn. While past experiences can help with learning, one needs to find one’s own ways of acting as parents. This component describes the development of coparenting through both the child–parent relationship and the parent-parent relationship. Shared parenting is on a firm foundation if each partner allows the other room for growth as a parent .

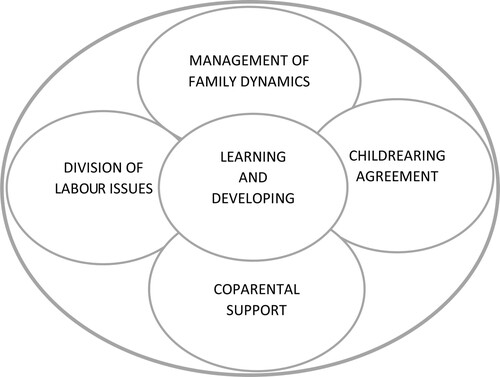

The five components are interrelated and affect each other, as shown in . As Feinberg (Citation2003) indicates, the four peripheral components are both partially associated and partially distinct and there is variability across families in the degree of linkage across these four components. The component of learning and developing is located in the centre, combining all four coparenting components together. Thus, growth in the central component affects growth in the surrounding components. Moreover, challenges in one component may complicate cooperation in another.

Discussion

This study makes an important contribution to understanding the role of coparenting from the perspective of new coming parents in two-parent families in Finland. The expectant first-time mothers and fathers saw coparenting multidimensionally. The couples’ descriptions of their coparenting expectations could be divided into five interactive areas. 1) division of labour issues, including parental roles and the sharing of duties and responsibilities and an emphasis on the attendance and participation of both parents; 2) management of family dynamics, including interparental communication and an emphasis on the importance of responsibility and commitment to family life and team working; 3) childrearing agreement, including mutual goals and rules on childrearing issues that enable both parents to meet the child’s needs; 4) coparental support, consisting of mutual encouragement, sympathy, and positive feedback allowing parents to help each other; and 5) learning and developing, related to learning and growing together as parents and to sharing and also giving the other parent space to develop. As well as describing coparenting content, the expectant parents talked about coparental aspirations, challenges, and the ideal of coparenting (see ).

This study strengthens and elaborates Feinberg’s (Citation2003) theoretical model of coparenting. It is noteworthy that these components were identified in the prenatal expectations of first-time parents. The study also updates the model by adding an important novel component, labelled learning and developing. The fifth dimension, describing coparenting as an opportunity to grow and learn during the parenting process through a collaborative parental relationship, finding one’s own way both as a parent and as a couple, giving the other parent space, and avoiding maternal gatekeeping, is possibly pertinent to expectant couples. The present results show that the ability to grow, develop and learn is needed in order to implement parenting in a slightly new way than society or one's own parents might expect. The talk about coparenting by the expectant mothers and fathers indicated that learning can be seen as collective communication between parents. For their part, Feinberg et al. (Citation2012) added a new dimension to their model, labelled parenting-based closeness, which refers to parents’ shared joy over the child’s development and the experience of working together that bring the partners closer together. Although the present expectant parents also hoped that their closeness and intimacy in a relationship would last during the early years, shared joy in watching the child’s development is not visible likewise in the prenatal stage.

Most of the present participants hoped to experience equal and shared parenting in which both parents can become experts in parenting. For them, equality meant wanting to work together in their own way and develop their own parenting style. They highlighted both parents’ possibility to participate in parental leave and working life. Successful cooperation did not necessarily mean that parents had to do the same things in the same way as their spouse or in exactly same amounts. Previous researchers (Hodkinson & Brooks, Citation2020; Miller, Citation2011) have reported that fathers are willing to share tasks and responsibilities as part of an interchangeable equal partnership where caregiving tasks are allocated based on factors other than gender, and thus transcend the differentiated roles of mothers and fathers. However, these expectations are challenged by the structural arrangements of society and the demands of working life making the parenting context more complex (Miller, Citation2011). Both partners in this study emphasized the importance of joint discussions and decisions to achieve parenting in harmony with their values and aspirations. It is worth noting that to facilitate coparenting quality, egalitarian values need to be clearly recognized not only at the family level but also in the structures of society. Entering a new stage of life and experiencing changes in family dynamics after childbirth necessitates new strategies for cooperation (Allan, Citation2008). It is important that both parents understand that they can better learn if they work together and share duties in a way of good cooperation.

This interview data focused on expectations of coparenting. Expectant parents’ prenatal hopes for ideal coparenting are also informed by their current couple dynamics (Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017). While they expressed optimistic ideals about their coparenting, they also raised concerns about interparental collaboration owing to differences in the partners’ temperaments, needs and background, exhaustion associated with childcaring, disagreements, time- and resource-consuming work, the mother’s potential gatekeeping role, and changes in the couple relationship. Previous studies (e.g. Solmeyer & Feinberg, Citation2011) have typically dealt with this issue from the viewpoint of the child’s temperament. This study, in turn, revealed that expectant parents are worried about the possible negative effects of their different temperaments on coparenting cooperation. In earlier research, researchers (Talbot & McHale, Citation2004; Van Egeren, Citation2003) have also asked how individual personality traits might influence coparenting. Another interesting concern raised in this study was the possible role of mothers as gatekeepers. Schoppe-Sullivan et al. (Citation2008) argue that mothers may limit fathers’ involvement by acting as gatekeepers, and that a supportive coparenting relationship combined with an encouraging partner is the most likely condition for promoting involved, competent fathering behaviour. Thus, these findings showed that expectant first-time parents were already aware of possible challenges stemming from their current relationship.

The desire of the expectant first-time parents for mutual and supportive interaction and cooperation was evident. Showing consideration for the other parent was seen as the mainstay of coparental support. Helping and doing for the other parent was described as a desirable way to support one’s spouse that was appreciated already during the pregnancy. In addition to being sensitive to the child’s needs, the spouses hoped to be sensitive to each other. It is beneficial for coparents to actively recognize their partner’s support and determine what kind of support suits them best, e.g. offering emotional support, encouraging breaks away from the baby, and self-care (Sheedy & Gambrel, Citation2019). The present results also emphasize the importance of flexibility in the parental role where both parents work together or alternate in childcare. Talbot and McHale (Citation2004) and Van Egeren (Citation2003) found that parents’ psychological flexibility was important, e.g. in how capably parents incorporate their child and their partner into the family dynamic. Parents may experience little motivation for flexibility if their partner shows inflexibility or criticizes them (McHale et al., Citation2004). Learning how to be fluid and flexible within the coparenting relationship makes for successful coparenting. Flexibility in parental roles also appeared to help couples navigate the stress of coparenting. (Feinberg & Kan, Citation2008; Sheedy & Gambrel, Citation2019.)

Finally, this study highlighted coparenting as a field of learning and growing up. Previous studies have also found a developmental perspective, but it has not been identified as a dimension of coparenting. The coparenting relationship, like other adult relationships, develops too (McHale et al., Citation2004) during the life course. Furthermore, families are not static, but change over time, along with other developmental processes (Feinberg, Citation2003; Kotila & Schoppe-Sullivan, Citation2015). Coparenting has been identified as a central feature (McHale et al., Citation2004; Van Egeren & Hawkins, Citation2004) and as an interpersonal and intrapsychic process (Weissman & Cohen, Citation1985) in adult development. Parents who successfully cooperate and collaborate in raising children also value and respect each other’s involvement with the child, and desire to communicate with each other (Weissman & Cohen, Citation1985). This study also shows that successful coparenting involves mutual respect, equality, discussion and negotiation, enabling both partners to grow as a parent and a coparent. Cooperation was seen as a value an interactional family system where the child is the priority. Equal parenting seems to be strengthened by coparenting, at least in the expectations of our informants. As in previous studies (see Kuersten-Hogan, Citation2017), this study indicates that coparenting begins during pregnancy when parents start to plan and discuss the dimensions of coparenting together.

Limitations and future directions

The findings of this study highlight prenatal expectations on coparenting. However, it has its limitations. First, the participants were heterosexual couples who were cohabiting or married, and childless. It is noteworthy that family forms have more recently diversified to include, e.g. same-sex couples, who were not included here. The number of single women is also growing, meaning that firstborns are found in very different family situations. Second, as is typical in family research, the participants were largely well-educated volunteers (Rönkä et al., Citation2014). To some extent, the findings on shared parenthood may be biased towards more egalitarian values. The idea of parenting as an equal and shared commitment in caring and work tasks has most clearly been observed among highly educated couples (Grunow & Evertsson, Citation2021). Couples struggling in their relationship during pregnancy are not likely to participate in a study of this kind (Rönkä et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, the pursuit of effective parental collaboration may have motivated some couples to participate. Thus, the educated middle class seems to be determining the most likely future model of parenthood. Third, the interviews and qualitative analysis focused on prenatal coparenting in general rather than on specific domains (see Feinberg et al., Citation2012) and thus warrant comparison with other groups across cultures. It is possible that utilizing Feinberg’s model in the study influenced our interpretations of the data. However, we only used the model after the data-driven phase of the analysis. In addition, the research questions may have led the interviewees to reflect more on their ideals and aspirations than concerns and challenges. However, the number of participants was sufficient to elicit expectations of coparenting in a qualitative study. Moreover, the age and family type distribution of the couples was representative of first-time parents in Finland (OSF, Citation2021).

Finally, as the context for this study was Finland, the results can best be generalized to similar countries with a relatively high level of gender equity (EIGE, equality index 74.7, Citation2020). Linking learning to coparenting may also be an important aspect in which equal parenting can be achieved. However, parents need support in how to negotiate with each other and learn together in cooperation. Riggs et al. (Citation2018) suggest that a stronger focus in parental education programmes on the social and emotional (intra- and interpersonal) rather than physical changes may be a useful strategy to help couples navigate the transition to first-time parenthood. This study showed that having a child can be seen as a mutual project and site for growth on both the individual and couple-relationship level. Van Egeren and Hawkins (Citation2004) noticed that studies in relationship processes before childbirth are excellent predictors of some aspects of coparenting quality. However, decisions that are made during prebirth discussions are often at odds with postnatal reality. For example, the expectations of couples who decide to share caregiving equally are likely to be violated, with mothers usually doing more and fathers less of the caregiving than earlier agreed (Miller, Citation2011). Clearly, more research is needed to find out whether these assumptions are any longer realistic in the present cultural framework. It is necessary to consider how society could support new parents to achieve their new parenting style aspirations.

Practical implications

These findings can be best utilized by professionals who work with families, first-time parents, and parents with young children, e.g. in maternity clinics and family centres. It is important that practitioners who work with couples during the transition to parenthood not only regard both expectant mothers and fathers as equally important, but also promote their clients’ understanding of the importance of both parents in the day-to-day care of their child. The findings may also have relevance in other cultures where equality and shared parenthood are displacing the traditional roles of mother and father.

Becoming a parent is a meaningful period of great adjustment for couples. This study suggests that it is important for new parents to discuss, share experiences and obtain knowledge about coparenting, and learn to work together as a team. Awareness of the two spouses’ thoughts about parenthood, cooperation, and childrearing may facilitate a good beginning to parenthood. Coparenting changes over time, and thus it is important to identify all the factors that drive good coparenting behaviour. In the future, the developmental dimension is likely to be one of the most important areas of coparenting research. If, as posited by the family system theory, coparenting is the centre around which family processes start and develop (Weissman & Cohen, Citation1985), then further study of the developmental dimension of coparenting is called for. Hence, to clarify what factors promote or hinder the development of interparental cooperation during the transition to parenthood, we will collect post-natal follow-up data on our participants until their child reaches the age of one and a half years. Learning is an important part of coparenting research, as it facilitates the implementation of parenting on an equal and collaborative basis. The opportunity to learn and grow and find one’s way both as a parent and as a couple is needed to implement parenting in their own way. When parents see parenting as a teamwork, they may see its similarities with the skills required in today’s working life. When cooperation and the division of labour proceed smoothly, and both parents grow into experts, a common approach to parenting may result. Challenges in coparenting cannot, however, be avoided, and coping with these also requires flexibility in everyday practices.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank the respondents participating in this study. Financial support was received from the Academy of Finland, grant number 323492.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allan, G. (2008). Flexibility, friendship, and family. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00181.x

- Allen, K. R., & Henderson, A. C. (2017). Family theories: Foundations and applications. Wiley Blackwell.

- Almqvist, A., & Duvander, A. (2014). Changes in gender equality? Swedish fathers’ parental leave, division of childcare and housework. Journal of Family Studies, 20(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2014.20.1.19

- Bengtson, V. L., & Allen, K. R. (1993). The life course perspective applied to families over time. In P. Boss, W. J. Doherty, R. LaRossa, W. R. Schumm, & S. K. Steinmetz (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 469–499). Plenum.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Daly, K. (2003). Family theory versus the theories families live by. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00771.x

- Dew, J., & Wilcox, W. B. (2011). If momma ain't happy: Explaining declines in marital satisfaction among new mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00782.x

- Durtschi, J. A., Soloski, K. L., & Kimmes, J. (2017). The dyadic effects of supportive coparenting and parental stress on relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(2), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12194

- Elder, G. H., Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(19), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender equality index 2020 for Finland. [referred: 10.5.2021]. Available at https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2020/FI.

- Feinberg, M. (2002). Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(3), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019695015110

- Feinberg, M., Brown, L., & Kan, M. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.638870

- Feinberg, M., & Kan, M. L. (2008). Establishing family foundations: Intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent–child relations. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253

- Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting, 3(2), 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01

- Grunow, D., & Evertsson, M. (2021). Relationality and linked lives during transitions to parenthood in Europe: An analysis of institutionally framed work-care divisions. Families, Relationships and Societies, 10(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674321X16111601582694

- Harword, K., McLean, N., & Durkin, K. (2007). First-time mothers’ expectations of parenthood. Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.1

- Hock, R. M., & Mooradian, J. K. (2013). Defining coparenting for social work practice: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Family Social Work, 16(4), 314–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2013.795920

- Hodkinson, P., & Brooks, R. (2020). Interchangeable parents? The roles and identities of primary and equal carer fathers of young children. Current Sociology Review, 68(6), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392118807530

- Kotila, L. E., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2015). Integrating sociological and psychological perspectives on coparenting. Sociology Compass, 9(8), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12285

- Kuersten-Hogan, R. (2017). Bridging the gap across the transition to coparenthood: Triadic interactions and coparenting representations from pregnancy through 12 months postpartum. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00475

- Lévesque, S., Bisson, V., Charton, L., & Fernet, M. (2020). Parenting and relational well-being during the transition to parenthood: Challenges for first-time parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 1938–1956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01727-z

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J, 9, 3351.

- McDaniel, B., Teti, D., & Feinberg, M. (2017). Assessing coparenting relationships in daily life: The daily coparenting scale (D-Cop). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2396–2411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0762-0

- McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 985–996. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.985

- McHale, J. P., Kuersten-Hogan, R., & Rao, N. (2004). Growing points for coparenting theory and research. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADE.0000035629.29960.ed

- Miettinen, A., Basten, S., & Rotkirch, A. (2011). Gender equality and fertility intentions. Evidence from Finland. Demographic Research, 24, 469–496. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2011.24.20

- Milkie, M. A. (2011). Social and cultural resources for and constraints on new mother’s marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00784.x

- Miller, T. (2011). Falling back into gender? Men's narratives and practices around first-time fatherhood. Sociology (Oxford), 45(6), 1094–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511419180

- Mills, M., Rindfuss, R. R., McDonald, P., & Velde, E. T. (2011). Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Human Reproduction Update, 17(6), 848–860. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr026

- Murphy, S. E., Gallegos, M. I., Jacobvitz, D. B., & Hazen, N. L. (2017). Coparenting dynamics: Mothers’ and fathers’ differential support and involvement. Personal Relationships, 24(4), 917–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12221

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Births [e-publication]. ISSN = 1798-2413. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 18.5.2021]. Available at Statistics Finland - Population - Births.

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Changes in marital status [e-publication]. ISSN = 1797-643X. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 8.4.2021]. Available at Statistics Finland - Population - Changes in marital status.

- Olsavsky, A. L., Yan, J., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Kamp Dush, C. M. (2020). New fathers’ perceptions of dyadic adjustment: The roles of maternal gatekeeping and coparenting closeness. Family Process, 59(2), 571. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12451

- Pinto, T. M., Figueiredo, B., Pinheiro, L. L., & Canário, C. (2016). Fathers’ parenting self-efficacy during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 34(4), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2016.1178853

- Pruett, M. K., McIntosh, J. E., & Kelly, J. B. (2014). Parental separation and overnight care of young children, part I: Consensus through theoretical and empirical integration. Family Court Review, 52(2), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12087

- Riggs, D. W., Worth, A., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2018). The transition to parenthood for Australian heterosexual couples: Expectations, experiences and the partner relationship. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 342. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1985-9

- Rönkä, A., Sevõn, E., Malinen, K., & Salonen, E. (2014). An examination of nonresponse in a study on daily family life: I do not have time to participate, but I can tell you something about our life. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.729401

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Brown, G. L., Cannon, E. A., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Sokolowski, M. S. (2008). Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Settle, T., Lee, J., & Kamp Dush, C. M. (2016). Supportive coparenting relationships as a haven of psychological safety at the transition to parenthood. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141281

- Sevón, E. (2012). My life has changed, but his life hasn’t’: Making sense of the gendering of parenthood during the transition to motherhood. Feminism & Psychology, 22(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353511415076

- Sheedy, A., & Gambrel, L. E. (2019). Coparenting negotiation during the transition to parenthood: A qualitative study of couples’ experiences as new parents. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 47(2), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2019.1586593

- Silver, C., & Lewins, A. (2014). Using software in qualitative research: A step-by-step guide (2nd edition.). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473906907.

- Solmeyer, A. R., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: The roles of infant temperament and coparenting relationship quality. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006

- Talbot, J., & McHale, J. (2004). Individual parental adjustment moderates the relationship between marital and coparenting quality. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADE.0000035627.26870.f8

- Van Egeren, L., & Hawkins, D. (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADE.0000035625.74672.0b

- Van Egeren, L. A. (2003a). Prebirth predictors of coparenting perception trajectories in early infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(3), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.10056

- Van Egeren, L. A. (2004). The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25(5), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20019

- Weissman, S., & Cohen, R. (1985). The parenting alliance and adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 24–45.