ABSTRACT

Using data from the Generations and Gender Survey, this study explores the association between men’s fields of education and the gender division of unpaid work among co-residential heterosexual couples in Norway, Austria and Poland. Fathers’ relative contribution to childcare is higher than it is to domestic work in all three countries, suggesting that men have increasingly become more involved fathers than egalitarian partners. Moreover, the scant contribution to housework is lower for men when they are fathers in Austria and in Poland, not in Norway. Also the impact of the field of education is context-embedded. Although the results are not clear-cut and diverge among countries, men choosing ‘softer’, more nurture-oriented and more female-dominated fields tend to exhibit a more symmetrical division of housework and childcare. These associations persist after controlling for his and her labour-market position, suggesting that field of education captures something more than time availability, cost opportunity and monetary returns. Yet Polish men are those most differentiated by level and field of education. In Poland, gender segregation in education is high, and support for the dual earner-dual carer model is still very low both institutionally and culturally, so that men studying in typically female fields are highly selected.

Introduction

There is by now a substantial body of research showing that the last 40 years have seen a significant shift in the gender division of labour in Western countries, with women more engaged in paid employment also when they become mothers and men contributing more to housework and especially to childcare (Coltrane, Citation2000; Craig & Mullan, Citation2011; Sullivan, Citation2021). These changes have been the outcome of not only new gender models but also of new models of fathering and fatherhood (Marsiglio et al., Citation2000; Musumeci & Santero, Citation2018).

Within the wider literature on the division of housework and childcare, there is also a substantial body of research which has focused on differences among subgroups of the population – distinguished by employment status, income, social class or educational attainment – and among welfare contexts (Bühlmann et al., Citation2010; Geist, Citation2005; Hook, Citation2010; Pailhé et al., Citation2021; Sullivan et al., Citation2014; Van der Lippe et al., Citation2011). This body of research shows that men in Scandinavian countries contribute more to the domestic economy than do others, in particular men in Southern and Eastern Europe. The contributions of men in the liberal (English-speaking) countries and the corporatist countries of Continental Europe fall somewhere in between. In the post-communist welfare regime, the gender gap in unpaid work is wide but women spend more time on paid work than in the Mediterranean and conservative regimes. This body of research also shows that everywhere highly educated couples have more egalitarian values and practices (England et al., Citation2012; Sullivan et al., Citation2014), but their gap with less educated men and women is institutionally and culturally embedded. It is lowest in social-democratic countries, where both attitudes and practices are less traditional and where institutions support new gender and family models (Geist, Citation2005; Solera & Mencarini, Citation2018; Steiber et al., Citation2016): that is, in those countries where the gender revolution is at an advanced stage (Pailhé et al., Citation2021).

In parallel, since the 2000s a new stream of research has shown that not only the level but also the field of education, both of the woman and of the man, matters in shaping decisions about fertility and union formation (Hoem et al., Citation2006; Martín-García et al., Citation2017; Oppermann, Citation2014). But does the field of education also matter in shaping gender divisions of unpaid work? Are men trained in what have been traditionally considered ‘women’s fields’ more prone to assume everyday tasks of housework and childcare? Alternatively, do men in male-dominated technical fields contribute to core domestic work and childcare as much (as little) as men trained in fields in which the large majority of students are women and where traditional stereotypical female qualities prevail? Are these effects different across different policy and cultural contexts? These are still unexplored questions in the literature.

By drawing on the first wave of the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), our study contributes to filling this research gap: it analyses the association between a man’s field of education and his share of domestic and care work in co-residential (heterosexual) couples in three countries belonging to different gendered welfare regimes – Norway for the social-democratic welfare regime, Austria for the conservative regime, and Poland for the post-communist regime –.Footnote1

As many feminists argue, to ‘complete the gender revolution’ not only paid work but also care needs to be redistributed and valued (no longer coded as feminine) so as to reach the ‘universal caregiver ideal’ (Fraser, Citation1994) or achieve the ‘dual earner-dual carer’ society (Crompton, Citation1999; Gornick & Meyers, Citation2005). This new gender equity would benefit not only women but also men and children. Men would be free from the pressure of fulfilling the male breadwinner-unconditional worker role; children could build an intimate relation with both parents, with established life-long positive effects on their emotional and cognitive capacity (Pleck, Citation2010). Thus, putting men at the centre of analysis of the gender division of housework and care and extending it, in a cross-country comparative framework, to underexplored factors such as the educational field – factors that capture differences not only in labour market positions and prospects, but also in gender, family and career orientations – might make a major contribution to understanding how to boost men’s involvement in the reproduction sphere.

The role of field of education: theories and hypotheses at the micro-level

Possible mechanisms: self-selection, socialization, and labour market prospects

Three theories have been mainly used to explain couple’s time allocation between the family and the labour market: ‘specialisation’ and ‘bargaining or economic dependency’ theories – centred on the importance of relative resources and time availability – and ‘doing gender’ theories, centred on the importance of attitudes and ideals, of the so-called gender ideologies (Aassve et al., Citation2014; Carlson & Hans, Citation2020). Either because education gives better positions in the labour market, and thus yields better earnings with which to keep working and externalize care or to bargain for a greater involvement of the partner, or because it encourages different gender and motherhood-fatherhood ideals, in all three approaches the level of education is given crucial importance.

As a new line of demographic research has recently pointed out, not only the educational enrolment and attainment, but also the field of study is important in shaping men’s and women’s family and work choices and outcomes. According to these studies (Begall & Mills, Citation2012; Hoem et al., Citation2006; Martín-García & Baizán, Citation2006), education is not just an instrument to accumulate human capital that can be later sold in the labour market and hence a mere indicator of the opportunity costs of childbearing and childrearing. Education may also be a proxy for the symbolic rewards of housework and childcare, given that individuals do not value children and careers equally. Three diverse mechanisms may be responsible for this association.

First, educational fields may capture anticipated future roles and practices, i.e. they may be indicative of preferences for certain gender roles, family models and work-family combinations. The same attitudes and personality traits that induce a man to choose a specific field of education may also induce him to be more an egalitarian partner and/or an involved father. For instance, a nurturing personality or a preference for less competitive jobs may push men into some particular fields and later into ‘softer’ occupations that facilitate a more symmetric allocation of domestic and care duties and that allow for new models of masculinity and fatherhood (Lappegård & Rønsen, Citation2005; Martín-García et al., Citation2017). Thus, women and men with a notable preference for family life and caring for other family members may be overrepresented in certain fields due to this self-selection (Lesthaeghe & Moors, Citation2002).

Second, the choice of a specific discipline entails a different socialization during the formative years and adult life. The environment, experiences and ideas transmitted in the educational system while women and men are enrolled on a particular study programme shape their values, attitudes and aspirations in life, with a possible impact on their future gender attitudes and practices (Van Bavel, Citation2010).

Third, different fields of study are linked to different (perceived or actual) labour market conditions and prospects. Each field conveys differences in the chances of finding a job, in the (mis)match with available occupations, or in the time that it takes to become established in the labour market. Additionally, different fields of study vary regarding the type of job to which they lead, in terms of job content, employment security, wages, or family-friendly working conditions (such as those in the public sector). According to the gender role theory, compared to women men tend to choose competitive fields with more economic capital and quantitative skills that lead overwhelmingly to occupations with higher income and prestige (Ochsenfeld, Citation2014). But there are differences not only between men and women but also within men and women. As Hoem et al. argue (Citation2006), family-oriented women are more likely to opt for fields with smaller penalties for career breaks and family investments even if they lead to lower wages.

The consequent question, much less addressed in the literature, is whether the same heterogeneity can be observed for men. We argue that the field of education captures such heterogeneity also for men, and that it affects their adult participation in unpaid work. We thus formulate the following general (context-less) hypothesis:

H1 Men studying ‘health, welfare and teaching’ and ‘humanities and arts’ participate more in unpaid work than do men studying ‘engineering, manufacturing and construction.’

Men trained in disciplines in which the large majority of students are women not conforming to rigid gender norms may have value orientations that are more favourable to new models of masculinity and fatherhood and of family-work combinations; hence they may display greater involvement in housework and childcare when they are in co-residential (heterosexual) couples. These men are expected to be more involved because of a combination of the above three mechanisms underlined in the literature: partly because of their pre-existing values and perceptions of masculinity, fatherhood and gender roles, but also because of a more nurturing and gendered equal field-specific socialization during their years in education and of lower opportunity costs in their (future or actual) occupations.

Housework as distinct from childcare

Specialization occurs not only between unpaid and paid work but also within types of unpaid work. Evidence shows that women tend more than men to do housework tasks that are less time flexible and discretionary. Time-inflexible tasks, such as cooking, are more likely to limit paid work and leisure opportunities than are time-flexible tasks that can be put off or done at any time (Coltrane, Citation2000). Moreover, men tend to prioritize childcare over housework, and especially those childcare tasks that are less essential but more creative (such as playing and reading stories compared to feeding or bathing) (Almqvist & Duvander, Citation2014; Borràs et al., Citation2021). Routine housework activities (cleaning, laundry, shopping for groceries) are indeed perceived as the least preferable and enjoyable due to their monotonous, uninteresting and solitary nature, whereas childcare is an intrinsically more rewarding activity. Furthermore, the implications of living in a dirty house are less dire than those of neglecting to care for children. Finally, the positive relationship between father’s level of education and time spent on childcare is more mixed than time spent on housework. The same applies to relative resources: while fathers who earn more money do less housework, they do not necessarily engage in less childcare. The ideal of intensive parenting seems quite widespread, so that participation in childcare is more affected by time availability, in particular his and her quantity and distribution of working hours (Hewitt et al., Citation2012).

Since the rewards, the implications, the trends and also the correlates of participation in them differ (Craig & Mullan, Citation2011; Pailhé et al., Citation2021; Sullivan, Citation2013; Citation2021), we opt for analysing housework as distinct from childcare. And, on the basis of previous evidence and the arguments just summarized, we formulate the following second (context-less) hypothesis:

H2 The effect of field of study is stronger for housework than for childcare.

Since the ideal and practice of being an involved father are more widespread than those of being an egalitarian husband, we expect to find that the effect of education, and also of field of education, are stronger for the performance of housework than childcare: men trained in ‘women’s fields’ are a group more self-selected in regard to domestic work than to childcare.

The role of field of education: theories and hypotheses at the macro-level

What contextual factors matter? The debate

Although trends toward gender convergence in unpaid work are observed across Europe and the United States, a large amount of cross-national studies indicate that allocations of paid work, housework and childcare are determined by complex relationships between micro-level characteristics and macro-level factors (Bühlmann et al., Citation2010; Geist, Citation2005; Hook, Citation2010; Pailhé et al., Citation2021; Sullivan et al., Citation2014; Van der Lippe et al., Citation2011). To capture the role of such macro-level factors, several typologies of welfare regimes have been developed in the past two decades. The first was the typology drawn up by Esping-Andersen (Citation1990), which focused on the state-market relation and on the degree and type of de-commodification. There followed less gender-blind typologies calling attention to the family and its relationship with the state and the market in the production of public welfare (through more or less ‘de-familialising’ measures). Thus the notion of social citizenship was expanded to incorporate reproduction and care (also as a right and duty for men, towards a ‘universal caregiver ideal’) by comprising the influence of ideas, discourses and ideologies alongside political ideologies (for an overview, see Ciccia & Sainsbury, Citation2018). Regardless of the approach chosen, there is consensus that the type of welfare regime matters in producing, reinforcing or de-powering gender inequalities because it influences access both to concrete resources and opportunities, and to normative definitions of what kinds of care and family are ‘best for the child’ and of what are acceptable ways to be a mother or a father.

Instead of looking at the overall regime, or at overall policy and cultural configurations (Altintas & Sullivan, Citation2016; Bühlmann et al., Citation2010; Geist, Citation2005), many recent studies have identified and measured specific dimensions of the macro-context, such as economic development, women’s employment, social norms about gender and work and about motherhood and fatherhood, availability of childcare services, and leave also for fathers. These studies find that there is more gender equality in housework and childcare in countries with higher levels of female labour-force participation, greater provision of publicly funded childcare, high-paid paternity leave or parental leave with reserved quotas for fathers rather than maternity leave programmes (especially if long), and with more egalitarian gender attitudes and more diffusion of new family forms (Hook, Citation2010; Pailhé et al., Citation2021; Van der Lippe et al., Citation2011).

In line with Pailhé et al. (Citation2021), in this study we analyse differences among countries with respect to public policies, social norms and gender relations in the spheres of the labour market and the family, adding also the education dimension. The underlying idea is that gender is a social structure (Risman, Citation2004), constructed and performed at all levels (macro, meso and micro) and in all spheres (economic, cultural, institutional). Thus, to ‘undo gender’ and ‘complete the gender revolution’, new values and practices at the micro level need to be extended to the private sphere and to be supported by practices and discourses at the macro level. Some scholars have indeed suggested that the gender revolution has ‘stalled’ since women’s participation in paid work has increased much more than men’s participation in unpaid work, and since such new practices are still restricted to the most educated social groups (England, Citation2010; Esping-Andersen, Citation2009; Hochschild & Machung, Citation1989). Yet countries differ in the stage of the gender revolution that they have reached. In Scandinavian countries, where the gender revolution has started the second phase – that is, where housework and care are done and valued also by men and are ‘de-commodified’ and ‘de-familialised’ through proper universal state policies – gender allocations of time and responsibilities are proved to be more symmetric and more ‘universal’, that is, less confined to specific self-selected ‘innovative’ groups such the most educated ones (Pailhé et al., Citation2021).

To our knowledge, to date no-one has analysed the link between macro contexts and polarization by field of education in gendered work-family practices. Like Bühlmann et al. (Citation2010), we argue that the division of labour importantly depends on what individuals think and want (in particular, on their values regarding gender relationships, masculinity/femininity, and what is best for the child) and that the translation of these values into behaviours/practices is moderated and shaped by structures of opportunities and constraints. If men’s choice of a specific field of study reflects their values heterogeneity, it is reasonable to assume that in countries where the gender revolution is less advanced (and also gender segregation in education is higher), the ‘few’ men that enter and achieve typically female-dominated fields are more likely to exhibit distinct self-selected characteristics than are the majority of men entering mixed or male-dominated fields, who more closely follow the ‘norm’. Such higher selectivity is likely to produce distinct behaviours also later in men’s future participation in unpaid work when they become partners or fathers. In other words, in more traditional countries, one should observe a stronger effect of field of education on men’s share of domestic and care work compared to the case in less traditional countries.

The profile of our countries

shows the profile of our three countries – Norway, Austria and Poland – according to various indicators in the spheres of education, labour-force participation, welfare and gender relations emphasized in the literature as relevant to shaping men’s and women’s work and family practices.

Table 1. Contextual indicators for Norway, Austria and Poland.

Norway is classified as a social-democratic welfare regime (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990; Citation2009) or a ‘dual earner-dual carer’ gender arrangement (Crompton, Citation1999; Fraser, Citation1994; Gornick & Meyers, Citation2005) that promotes gender equality, as well as the balance among work, family and personal life by redistributing the costs and responsibilities of raising children between families and the state (‘de-familisation’), and within families, between men and women (‘de-motherisation’) (Mathieu, Citation2016). Indeed, Norway offers affordable and universal early childhood education, the protection of working mothers and fathers with children, and, already since the 1990s, parental leave and other conciliation measures that favour shared parenting (Bjørnholt & Stefansen, Citation2018).Footnote2

shows that in Norway also the approval of traditional gender roles records the lowest rate, with for example only 1% of the population agreeing that a ‘a man’s job is to earn money and a woman’s job is to look after the home and family', as opposed to 27% in Austria and 38% in Poland. The result, in terms of behaviour, is less segregated fields of study (for example, men constitute 39% of the students in ‘humanities and arts’ as opposed to 34% in Austria and 24% in Poland), the highest female participation in paid work and male participation in unpaid work, the shortest working hours for both men and women, and the largest amount of ‘new’ family forms.

Austria – an example of the conservative, or corporatist, welfare cluster – not only relies mainly on the principle of subsidiarity but also assumes and favours the traditional family model of ‘one earner and half-female caregiver’. In fact, one out of three working women has a part-time job; one out of two if they are mothers. The ‘explicit familialistic’ orientation of Austria’s social policies (Leitner, Citation2010) is particularly evident in a level of public spending on families which is as high as in Scandinavian countries but mainly directed towards income transfers rather than towards ‘de-familising’ childcare services and shared parenting.Footnote3

Poland – an example of the post-communist welfare cluster – has experienced since 1989 a move from ‘de-familisation’ to ‘re-familisation’ or ‘implicit familialism’ (Bjørnholt & Stefansen, Citation2018; Szelewa & Polakowski, Citation2008). Poland spends only about 2% of GDP on family policies: enrolment rates of children aged 0–2 years in early childhood education and care services are around 4% (the lowest level of formal childcare enrolment in the EU); paid maternity leave is long (20 weeks, as opposed to 16 in Austria and 0 in Norway) coupled with parental leave as a family and not individual entitlement and one week of paid paternity leave.Footnote4 In parallel, in Poland both attitudes and behaviours are strongly traditional: as shown in , the gender gap in the average amount of time spent on unpaid work is only slightly higher than in Austria (3.44 as opposed to 3.35 in Austria and only 1.36 in Norway) but female labour-force participation, although mainly on a full-time basis, amounts to only 57% (compared to 69% in Austria and 77% in Norway); consensual unions constitute only 3% of all family nuclei; the idea that women’s full-time employment is detrimental to the well-being of the child or the family is less widespread than in Austria (a stronger part-time country) but more widespread is approval of female housewifery. Overall, societal gender equality is the lowest among the three countries examined, placing Poland, according to the index developed by the United Nations Development Programme across 162 countries, in 39th position – Austria in 16th position, and Norway in 6th.

Given the different profiles of our three countries as just summarized, in particular, the different support given to ‘the universal caregiver’ model and the different level and stage of their ‘gender revolution’, we can formulate the following third (context-embedded) hypothesis:

H3 The effect of field of study is the strongest in Poland, medium in Austria, and the weakest in Norway.

Men choosing traditional female fields are a more restricted and selected group in countries that are at an initial or stalled phase of the gender revolution, not supporting the ‘dual earner-dual carer’ model. Hence, in Poland, where we observe lower levels of female labour-force participation, of provision of publicly-funded childcare and of high-paid paternity leave or parental leave with quotas reserved for fathers, as well as lower adherence to egalitarian gender attitudes and to new family forms, we expect to find a stronger association between man’s field of education and his share of domestic and care work when living in a (heterosexual) couple.

Data and method

Data sources and samples

We used data from the first wave of the GGS in Norway (2007/2008), Austria (2008/2009) and Poland (2010/2011). Our interest centred on the contributions to domestic work and childcare made by men/fathers in couples. Our first analytical sample comprised all the respondents aged between 18 and 46 years old and living with a married/cohabiting partner of the opposite sex [n = 2209 (Norway); 3076 (Austria); and 5286 (Poland)].Footnote5 Then we restricted the sample to respondents aged 18–46 years in married/cohabiting heterosexual couples with young children under 15 years old to study the allocation of domestic and care work after the arrival of a child [n = 2016 (Norway); 2030 (Austria); and 3879 (Poland)].

Dependent variables

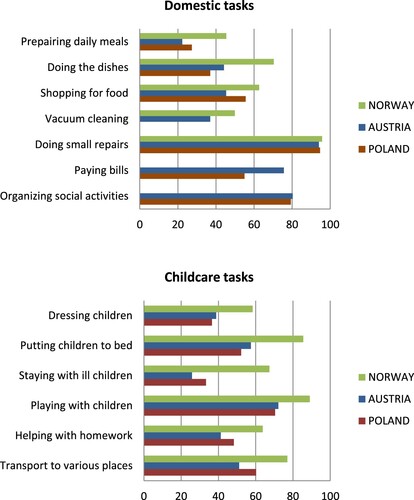

We used two variables to capture the distribution of unpaid work: men’s share of domestic work and men’s share of care work within the couple. Core domestic work was divided into 4 tasks: (a) preparing daily meals; (b) doing the dishes; (c) shopping; and (d) cleaning.Footnote6 In line with many studies separating domestic work into core housework and discretionary housework (Coltrane, Citation2000; Sullivan, Citation2013; Citation2021), we excluded tasks such as doing small repairs, paying bills, and organizing social activities. These are the tasks mostly performed by men, but not on a daily basis, that can be scheduled so that they fit with other commitments more easily than core housework (Pailhé et al., Citation2021). Hence, while their exclusion certainly leads to an underestimation of men's overall contribution, on the other hand it enables better capture of the truly ‘innovative’ men who perform and share domestic work on a daily basis. ‘Childcare’ refers to 6 tasks: (a) dressing children; (b) putting the children to bed; (c) staying at home with the children when they are ill; (d) playing with the children; (e) helping the children with homework; and (f) taking the children to/from different places (school, day care centre, babysitter or leisure activities).

The GGS does not include information on time spent on housework and childcare by each member of the couple.Footnote7 It only provides information on the relative share of housework and childcare between them as reported by one of them (the respondent). The possible answers are (1) always respondent; (2) usually respondent; (3) respondent and partner about equally; (4) usually partner; (5) always partner; (6) always or usually other persons in the household; and (7) always or usually someone not living in the household. As the respondent could be of either gender, we transformed the answers into (1) always the woman; (2) usually the woman; (3) the woman and the man about equally; (4) usually the man; (5) always the man. Following previous research, we included ‘outsourcing’ – categories (6) and (7) – in (3) since it implies the willingness and possibility to reduce the partner’s workload (Riederer et al., Citation2019; Solera & Mencarini, Citation2018). We linearly transformed the categorical answers (always respondent = 100%; usually respondent = 75%; respondent and partner about equally = 50%; usually partner = 25%; always partner = 0%), calculated the average score among the various items for each dependent variable, and then transformed it into share percentages that the man did (from 0 to 100 of domestic work and childcare). Consequently, the lower the share percentage, the greater the gender inequality in the division of unpaid work, with the woman doing most of the various core domestic chores and care tasks within the couple.

Independent variables

The focus of our analysis was on the effect of field of education. To better capture the net effect of the field regardless of educational attainment, we included two separate variables for level and field of education. Similarly, to better capture the effect of the man’s education regardless of his partner’s (the woman’s) education, we included two separate individual variables for each member of the couple. Given the evidence that what really makes the difference is being most educated or not, his and her level of education was measured into two categories: tertiary, which included bachelor, master and doctoral degrees (ISCED 5–6); and not tertiary (ISCED 0–4). As coded in the GGS survey and in line with the predominant categorization in the literature (Hoem et al., Citation2006; Martín-García et al., Citation2017; Martín-García & Baizán, Citation2006), the variable field of education for the man and his partner was distinguished into 8 categories: (1) basic programmes; (2) humanities and arts; (3) social sciences, business and law; (4) science; (5) engineering, manufacturing and construction; (6) agriculture; (7) health, welfare and teaching;Footnote8 and (8) services (such as police, hotel and restaurant worker, office assistant, beautician, etc.). Engineering, manufacturing and construction served as the reference category. These fields, traditionally male-dominated, are associated with higher aspirations in the labour market and with skills typically coded as masculine, which may result in a lower contribution to the daily routine tasks of housework and to childcare.

Control variables

We selected other independent variables to capture the dimensions that previous research had described as significant and see whether the effect of field of education remained after controlling for them. To grasp time availability for domestic and care work, we constructed an indicator of the man’s and his partner’s labour-force participation (if working, whether s/he was on ma/paternity leave, parental leave or childcare leave,Footnote9 part-timeFootnote10 or full-time employed).

Part-time employment is widely viewed as a female choice that inhibits men’s share of domestic and care work, promoting a ‘one earner and half-female carer’ model rather than a ‘dual earner-dual carer’ model. We also distinguished his and her occupational class. We considered five macro-classes: service, routine non-manual, petty bourgeoisie, agricultural, and working class. In the absence of information on available income or greater details on family-friendly working conditions,Footnote11 class seemed to be a good measure of the resources available. Finally, to capture different needs connected to different family life course stages, we also included the man’s age, his partner’s age, the number of children, the age of the youngest child and the gender of the respondent. The sample distribution of all variables that were part of the linear regression models is described in .

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample of men aged 18–46 (percentages and mean values for dependent and independent variables).

Field of education and the allocation of housework and care duties: results

Descriptive results

corroborates a gender asymmetry at home in the countries covered by the study, with men contributing less to housework and care than their female partner. However, as expected, Norwegian men do more unpaid work than their counterparts in Austria and Poland. Moreover, fathers contribute less to housework than non-fathers in Austria and Poland, although not in Norway, which is in line with the finding of previous cross-country comparative research that this ‘traditionalisation’ around childbirth is institutionally and culturally embedded (Grunow & Evertsson, Citation2019). also shows that in all three countries fathers’ relative contribution to childcare is greater than it is to housework. Hence core routine housework, generally perceived negatively and as among the least desirable of all activities because of its boring, repetitive and solitary nature (Hochschild & Machung, Citation1989; Sullivan, Citation2021), remains a more feminized task even in countries where gender practices and attitudes are comparatively non-traditional: Norwegian men assume 40% of the domestic workload; Austrian and Polish men around 29%. Childcare is more symmetric: Norwegian fathers are closer to an equal sharing of care (44.11) than are Austrian (33.13) and Polish ones (32.47).

On distinguishing by type of tasks, some common patterns emerge. Regarding domestic work, what men choose most is doing the dishes and shopping in all three countries, whether or not they have children. The least they do is cleaning (in Norway) and cooking (in Austria and Poland). With respect to the distinct spheres of care, in all three countries, what men do most is play with the children, put the children to bed, and take the children to/from different places, whereas they rarely stay at home with the children when they are ill (especially in Austria and Poland).

includes some information additional to the means presented in by showing the percentage of ‘involved’ men in each country, i.e. the proportion of men who always, usually, or on equal terms with the partner, participate also in non-routine domestic tasks at home. Women are mainly involved in activities that must be done for the well-being of other people. Meanwhile, men are mainly involved in activities that are flexible in terms of time throughout the day or that are not core everyday tasks (which is why we excluded them from the calculus of our dependent variable). In fact, everywhere the tasks most frequently performed by men are small repairs, paying bills, and organizing social activities. Preparing daily meals and staying at home with the children when they are ill (which entails taking hours/days off from paid work) are two of the least equal tasks in Norway, Austria and Poland, particularly in the latter two. Among the three countries, Austria is one where the allocation of these duties is more asymmetric.

Figure 1. Involved men in each country (i.e. percentage of men in ‘equally’, ‘usually man’ and/or ‘always man’ responses to the distribution of tasks between partners). Source: Own calculations on GGS, 1st wave.

Notes: No info on vacuum-cleaning for Poland. No info on paying bills and organizing social activities for Norway.

Multivariate regression results

presents the coefficients derived from linear regression models of men’s share of domestic and childcare work. In Model 1, we consider the man’s level of education alone, while, in Model 2, we consider his field of education alone (always controlling for the woman’s level or type of education). Model 3 runs level and field of education together to see whether the effect may be levelled off.Footnote12 Models 2a and 2b consider field of education alone (without level) but add information on the labour-market position regarding (a) part-time vs. full-time, and (b) the occupational class, to see whether the effect of field of education remains after controlling for the time availability and available resources.

Table 3. OLS regression models of men’s share of housework and childcare (men aged 18–46 in a couple with children under 15).

Our study confirms that education plays a significant role in the allocation of household and care duties, but that this effect is mediated by the institutional and cultural context in which parents live (Grunow & Evertsson, Citation2019). Model 1 shows that better-educated men are those more involved at home in Norway and particularly in Poland, and that the effect of the man’s level of education is much greater for domestic labour than for childcare in Poland. In Poland, where approval of gender traditional roles is still the norm, it seems that it is only being highly educated that breaks the norm, encouraging more equal attitudes and practices not only in the more enjoyable and interactive childcare but also in the more boring and solitary housework. However, no association between the man’s educational level and the distribution of chores, either housework or care, is observed in Austria.

For the men’s partners, the results confirm the well-known finding that there is a positive association between a woman’s level of education and a man’s share of core domestic work and childcare in all three countries. In general, the higher a woman’s level of education, the less housework she does and the greater her power within the couple when negotiating on housework and childcare responsibilities, particularly in contexts of unequal gender power. In fact, we observe that the positive effect of a more highly educated female partner is greater in Austria and Poland (the size of the coefficients are almost three times higher in both countries than in Norway), and more so for housework than for childcare. In Norway, where overall gender equality at a societal level is higher and where gender allocations at home have already reached quasi-parity (Bühlmann et al., Citation2010), the woman’s level of education differentiates less.

The inclusion of the covariate ‘field of study’ in models 2 and 3 adds nuances to the analysis. The empirical evidence does not provide clear support for hypotheses 1 and 2, that is, a link between men’s studying in traditional female fields – disciplines in which the large majority of students are women and that entail more ‘feminine perceived’ qualities – and a more symmetrical division of family work, especially housework. Yet, in line with hypothesis 3, interesting differences among countries emerge.

In Norway, men in traditional female fields such as healthcare do not exhibit a higher involvement in caring and household responsibilities.Footnote13 It is Norwegian men within the category ‘humanities and arts’ – the second most feminized discipline – who are more involved in both domestic and care work as compared to those with technical studies, and the difference is especially marked for childcare. Furthermore, Norwegian men trained in ‘social sciences, business and law’ and ‘science’ show a greater involvement in domestic work, and those trained in ‘agriculture’ – also a highly feminized field in the sample – show a greater involvement in domestic work and childcare respectively. So do men with ‘basic programmes’ concerning caring. By contrast, men trained in ‘services’ do less childcare than men with male-dominated technical studies. These associations persist after controlling for his and her type of labour-market position (whether full-time or part-time in model 2a; and the occupational class in model 2b), suggesting that field of education captures something more than time availability, cost opportunity and monetary returns. Difference is not especially marked for housework (thus disconfirming hypothesis 2 for Norway).

As said, no significant associations of men’s educational level with their share of both domestic and care work is discernible in Austria. However, in line with hypothesis 1, men trained in ‘basic programmes’ and especially in ‘health, welfare and teaching’ show a significantly greater involvement in domestic work compared to men in ‘engineering, manufacturing and construction’, also after controlling for time and class in the labour market (models 2a and 2b). Austrian men trained in ‘science’ do less housework, whereas men trained in ‘services’ do more, but these effects disappear when we introduce the labour-market covariates. With respect to childcare, men in ‘basic programmes’ and ‘humanities and arts’ show a significantly higher involvement compared to men in technical fields. The higher involvement of men trained in the ‘basic programmes’ category concerning the two dimensions could be possibly due to the relatively worse employment prospects faced by these men. Moreover, given the ‘explicit familialistic’ orientation of Austrian social policies and a still prevalent traditional gender culture (such as the widespread idea that women’s full-time employment is detrimental to the well-being of the child or the family), among Austrian men, the categories ‘health, welfare and teaching’ and ‘humanities and arts’ suggest a plausible relation between the choice of ‘softer’ (and possibly more nurture-oriented) and more female-dominated educational fields and a more symmetrical division of housework and childcare respectively, especially for housework (thus confirming hypothesis 2 for Austria).

Most interestingly, in line with hypothesis 3, Polish men appear to be the ones most differentiated by both level and field of education. Poland is the country where the division of unpaid and paid work should depend more on individuals’ economic resources, given the country’s relatively worse position in terms of employment levels, economic opportunities, and social welfare. More than anywhere else, employment stability is important to Polish men not just because of income prospects, but because it may also be associated with deep-rooted cultural and societal expectations of what being a ‘good husband and father’ means. We observe that, of the three countries examined, Poland is the one in which the field of education has a stronger differentiating influence because, in the most stalled gender revolution context, men choosing specific atypical fields are highly selected. In fact, the size of the education-related coefficients is the highest in Poland. Despite a threat to their ‘breadwinning’ capacity, some Polish men opt out of rigid gender boundaries, choosing certain ‘feminine’ disciplines which may later translate into ‘softer’ occupations such as teaching, healthcare or social work, involving qualities labelled as feminine, and normally leading to more family-friendly and lower-paid jobs. Polish men trained in ‘humanities and arts’, ‘social sciences, business and law’ and ‘science’ are those most involved in both domestic work and childcare, even after controlling for his and her labour market position, since (with the exception of ‘science’) the differentiating effect is stronger for domestic than for childcare work (in line with both hypothesis 1 and 2). Polish men trained in ‘health, welfare and teaching’ also show a significantly higher involvement in housework and care compared to men in technical fields, but this positive association disappear for childcare after controlling for his and his partner’s educational attainment and labour market position (hypothesis 1 partially disconfirmed). Moreover, men trained in ‘agriculture’ participate less in housework than men with male-dominated technical studies.

Although it is only a control variable, the effect of the type of labour-market participation is interesting. Part-time vs. full-time employment is one of the most crucial determinants of both domestic and care work in couples with children, but in a gendered way. For men, being engaged in a part-time job does not have a positive incidence on their involvement at home in any of the three countries: to borrow Bittman et al. (Citation2003)’s expression, gender seems to trump time availability. In contrast, men’s full-time jobs reduce their participation in family work, and they do so more in certain structural and cultural contexts (almost twice as much in Austria and Poland). For women, working part-time discourages a more balanced distribution of family work in all three countries, but particularly so in the two most gender-unequal ones (Austria and Poland).

Occupational class also yields important insights into the distribution of chores. In general, working-class men are shown to emphasize their gender-normative role by contributing less to housework and childcare, particularly in Austria and Poland, where ‘dual earner-dual carer’ models are not the norm, and are supported neither institutionally nor culturally. In contrast, men with professional/managerial partners who belong to the service class do more housework and care than others, particularly in these two more traditional contexts.

Discussion

Nowadays, men are doing more around the home than previous generations, but gender segregation persists, especially in the share of domestic work. By putting men at the centre of the analysis of gender allocations of domestic and care work, and by including, in a cross-country comparative framework, underexplored factors such as field of study – a factor that captures not only differences in labour-market positions and prospects, but also in gender, family and career value orientations – our study contributes to the understanding of the production and reproduction of gender divisions.

Our results corroborate that men’s contribution to childcare, perceived as more enjoyable and rewarding, is indeed higher than their contribution to domestic work in all three countries, suggesting that changes over time in men’s increasing input into family work concern more being an involved father than an egalitarian partner (Fuochi et al., Citation2014; Grunow & Evertsson, Citation2019). Moreover, the findings confirm that practices are context-embedded. In fact, as expected, men are more involved in Norway than their counterparts in Austria and in Poland: almost one in two Norwegian fathers share care equally, whilst only one-third of Austrian and Polish men do so. However, even in Norway where the gender revolution is at an advanced stage, policies encourage ‘a dual-earner dual-carer model’ and gender relations and attitudes are comparatively non-traditional, what men do most is playing with the children. As previous research has suggested, fathers may seek ways to maximize time with their children by including children in their own leisure time (Bianchi et al., Citation2006; Sullivan, Citation2021). Staying with the children when they are ill, which involves more nurturing fathering and co-parenting practices, is less frequent, especially in Austria and in Poland, but also in Norway.

The analysis of education across countries adds further evidence that gender practices are institutionally and culturally embedded, not only in their ‘average’ frequency but also in their ‘distribution’ across social groups. We find that Poland, which ranks worst in terms of overall level of gender inequality, is the country with the strongest association between education (both level and field) and men’s involvement at home, especially in domestic work. A high education seems to significantly increase the contribution to childcare also in Norway, whilst it does not matter in Austria. Interestingly, and not surprisingly, what matters in all three countries and for the share of both housework and childcare, is the woman’s level of education, although the magnitude of the incidence also varies depending on the institutional and cultural context. As a proxy for stronger labour-market attachments and earning potentials and for weaker home-centred attitudes, women’s high educational attainments seem to give them the necessary power to reach more equal divisions with their male partners, regardless of their level and field of education. So does women’s full-time paid work, which has a strong positive and unequivocal effect on men’s share of family work in all three countries but especially in Austria and Poland, where traditional gender norms remain pronounced.

Our results are therefore in line with previous research highlighting that women’s high education and full-time status are the key drivers behind men’s adaptation within partnerships towards advanced levels of gender egalitarianism (Esping-Andersen, Citation2016). A more equitable and symmetric allocation of household and care duties is indeed found in Norway, where both women and men are expected to participate in the labour market, and therefore full-time employment is normatively expected for, and by, any woman. Full-time employment, be it for men or women, is also the norm in Poland, but the lack of support from the welfare state and traditional attitudes in allocating family responsibilities, together with an economy in difficulties, lead to a still too low level of women’s employment that blocks progression along the gender egalitarian path. Similarly, as long as the woman works but mainly as a part-timer (as in Austria), a conventional gender imbalance largely persists. This finding demonstrates that work-family policies matter, but so too do cultural norms. Work flexibility helps women only if it applies also to men, defining male household labour and care commitments as normal, as occurs in Norway.

In addition to reinforcing already-known evidence, this study has underscored the importance of looking beyond educational attainment and strict instrumental cost–benefit reasoning to grasp attitudes and ideals, and thereby gain a better understanding of gender dynamics and outcomes. Despite differences among countries, with the inclusion of the field of education, our study has shown that men do not form a homogenous group. Indeed, either because of their pre-existing ideals of masculinity and of fatherhood, or because of a more nurturing and equitable field-specific socialization during their years in education and lower opportunity costs in their occupations, there is an association between the choice of non-technical male-dominated fields and less traditional behaviours at home. Men trained in fields associated with stereotypical female qualities – such as those concerned with the care of individuals and/or which emphasize interpersonal skills (e.g. ‘health and welfare’, ‘teaching’ or ‘humanities and arts’) – maintain greater amounts of domestic and childcare work, irrespective of their educational attainment and labour-market participation. But this association for share of unpaid work appears to be less strong and less uniform across countries than what was previously reported for other outcomes such as fertility or union formation. This suggests that ‘undoing gender’ in the private sphere is more challenging because socially ingrained ideas about men and women and what is best for the child are often acted out through family work without great awareness (Carlson & Hans, Citation2020).

In fact, we find only partial support for hypothesis 1 (men trained in ‘health, welfare and teaching’ are more involved in Austria and Poland, but not in Norway; men trained in ‘humanities and arts’ are more involved at home in all three countries); mixed evidence for hypothesis 2 (a stronger differentiating effect of the field of education for domestic rather than childcare work in Poland and Austria but a lesser effect in Norway); and clear support for hypothesis 3 (it is in Poland that the association between men’s field of study and their contribution to housework and childcare is stronger, also after controlling for level of education or for labour-market position). The more the ‘dual earner-dual carer’ model is supported and widespread (for instance, by giving also fathers – not just mothers – the right to take parental leave and to obtain working-time flexibility), the more it is accepted that men may not be the only (or the main) providers, and the less their involvement at home may be perceived as a threat to their ‘breadwinning’ capacity and their masculinity (Gornick & Meyers, 2005).

Poland promotes paternal care neither institutionally through father-friendly policies, nor culturally through a general approval of new gender roles. Hence in Poland self-selection is higher: those few men choosing atypical paths, such as studying in traditionally feminine-defined fields, have very specific characteristics that lead also to different behaviours in many spheres. This lends support to the idea that certain groups may work as ‘innovators’ and that education may be conceived as a mechanism to spread ideologies and practices that promote the egalitarian division of domestic labour and care, but that this ‘social diffusion’ effect needs to be supported at all levels and spheres, through less gendered family-market-state institutions (Esping-Andersen & Billari, Citation2015).

Although innovative because it addresses a hitherto unexplored question, our study suffers from some limitations. First, as noted above, men’s performance of housework and childcare is based on the relative share between each member of the couple as reported by the respondent. This may be problematic if women systematically underestimate men’s relative responsibility for various activities and if such underestimation is context-embedded, although we have controlled for the respondents’ gender in order to mitigate precisely this potential bias. Second, doing the laundry – one of the most gender-stereotyped tasks of the core housework – is absent from the data. Third, we have not proved whether men end up by working later on in the specific fields in which they are trained. Thus, we cannot disentangle the various possible mechanisms identified in the literature (e.g. pre-existing values, socialization in male-dominated, mixed or female-dominated fields vs. working conditions). Fourth, our results should be considered as exploratory since GGS data on educational fields make it difficult to gauge clear-cut associations due to a high degree of variation and inconsistencies in the grouping of fields across countries. We would need harmonized data and a standardized categorization of educational fields. Moreover, the relatively small size of the different educational field categories may have precluded the detection of statistically significant associations. Future data collection should reduce these limitations.

Even with these limitations, our study suggests some ‘policy lessons’. As emphasized by feminist scholars, if the gender revolution is completed, not only paid work but also care and reproductive work should become a universal right, for both women and men. But not only the labour market, the family and the welfare state – that is, the welfare regime – needs to be re-thought and re-designed. Efforts should also be addressed towards less gender segregation and greater equity in educational choices and outcomes. In particular, with the closing and then reversal of the gender gap in tertiary education, more attention should be paid to educational fields. Indeed, our study shows that a larger decline in gender segregation in the choice of lines of education could be crucial for changing patterns of gender specialization within families.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A country from the Mediterranean regime could not be included in the analysis because Spain, Greece and Portugal are not in the GGS and Italy does not provide information on field of study.

2 Norway introduced a four-week non-transferable and well-paid paternity quota of parental leave in 1993, extended by an additional week in 2005. In 2018, Norway had two weeks of paternity leave, with payment dependent on collective agreements, plus a further 15–19 weeks of father’s quota. The remaining 16 or 18 weeks was a family entitlement and could be taken by either parent (Koslowski et al., Citation2019).

3 In Austria in 2018 there was no statutory entitlement for paternity leave, and parental leave was a family entitlement, but ‘bonus’ paid weeks were offered if both parents used a certain portion of the family entitlement. Assuming that the family wished to maximize the total length of leave on offer, this implied a certain number of weeks effectively ‘reserved’ for fathers or the ‘second’ parent (Koslowski et al., Citation2019).

4 Paternity leave was introduced in 2010, lasting one week until the child was 12 months old, extended to two weeks in 2012.

5 Austria included only individuals aged 18–46 years in its sample of the first wave. Consequently, we restricted the analysis to those ages in all countries.

6 Vacuum cleaning is not recorded in the Polish survey.

7 Time use data are widely considered to be the most reliable measure of domestic work and childcare, but they do not provide information on field of study.

8 Not applicable are data on ‘teacher training and education science' in Norway.

9 Given the very low numbers of men on leave, we merge this category with not working men.

10 Following the OECD, part-time workers were defined as people in employment (whether employees or self-employed) who usually worked less than 30 h per week in their main job.

11 Data on wages and income are not available in the first wave of the GGS for the specific countries studied, and some sampling issues may have distorted the results for public/private employment. According to national data, the percentage of public employment was 29.3, 11.4 and 9.7 for Norway, Austria and Poland respectively around the years of the GGS. In parallel, corresponding figures for gender equality in public sector employment are 68%, 58.5% and 59% for those years. However, the share of employees in the public sector is much larger among men than among women in the Polish sample (49.65% vs. 24.23%), while the opposite is the case in Norway, where the share of public employees is quite large for women (48.72%) but not for their male counterparts (22.93%). In the Austrian sample, 20.23% of men and 18.01% of women were engaged in a public job. As seen, national differences in employment in general government and public corporations or in gender equality in public sector employment could not explain these substantial differences in the samples. Hence we excluded the covariate from the analysis due to its lack of reliability.

12 We replicated the analysis with inclusion of the covariate field of education for each educational level in order to identify differences by field in the share of domestic and care work among men within the same educational level. Neither the magnitude nor the significance of the effects changed substantially with respect to the results presented here. Hence, we opted to keep the two variables separate (results available upon request).

13 There are no applicable data on ‘teacher training and education science’ in the Norwegian GGS. Moreover, some sampling issues concerning the health and welfare category could explain this substantial difference in the results. According to Eurostat, 82.5% of graduates (ISCED 5–6) in the health and welfare field were females in 2008, the year of the first wave of the GGS in Norway (2007/2008). The corresponding figure was only 36% in the Norwegian sample.

References

- Aassve, A., Fuochi, G., & Mencarini, L. (2014). Desperate housework: Relative resources, time availability, economic dependency and gender ideology across Europe. Journal of Family Issues, 35(8), 1000–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522248

- Almqvist, A. L., & Duvander, A. Z. (2014). Changes in gender equality? Swedish fathers’ parental leave, division of childcare and housework. Journal of Family Studies, 20(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2014.20.1.19

- Altintas, E., & Sullivan, O. (2016). Fifty years of change updated: Cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research, 35, 455–470. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.16

- Begall, K., & Mills, M. C. (2012). The influence of educational field, occupation, and occupational sex segregation on fertility in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 720–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs051

- Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bittman, M., England, P., Folbre, N., Matheson, G., & Sayer, L. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109(1), 186–214. https://doi.org/10.1086/378341

- Bjørnholt, M., & Stefansen, K. (2018). Same but different: Polish and Norwegian parents’ work-family adaptations in Norway. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718758824

- Borràs, V., Ajenjo, M., & Moreno-Colom, S. (2021). More time parenting in Spain: A possible change towards gender equality? Journal of Family Studies, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2018.1440618

- Bühlmann, F., Elcheroth, G., & Tettamanti, M. (2010). The division of labour among European couples: The effects of life course and welfare policy on value-practice configurations. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp004

- Carlson, M. W., & Hans, J. D. (2020). Maximizing benefits and minimizing impacts: Dual-earner couples’ perceived division of household labor decision-making process. Journal of Family Studies, 26(2), 208–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2017.1367712

- Ciccia, R., & Sainsbury, D. (2018). Gendering welfare state analysis: Tensions between care and paid work. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1(1–2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1332/251510818X15272520831102

- Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labour: Modelling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1209–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x

- Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2011). How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review, 76(6), 834–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411427673

- Crompton, R. (1999). Restructuring gender relations and employment: The decline of the male breadwinner. Oxford University Press.

- England, P. (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender & Society, 24(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475

- England, P., Gornick, J., & Shafer, E. F. (2012). Women’s employment, education, and the gender gap in 17 countries. Monthly Labor Review, 135, 4: 3–12.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). Incomplete revolution: Adapting welfare states to women's new roles. Polity Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2016). Families in the 21st century. SNS Förlag.

- Esping-Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00024.x

- Fraser, N. (1994). After the family wage: Gender equity and the welfare state. Political Theory, 22(4), 591–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591794022004003

- Fuochi, G., Mencarini, L., & Solera, C. (2014). Involved fathers and egalitarian husbands: By choice or by constraint? A study on Italian couples with small children (Collegio Carlo Alberto Notebooks, n.370).

- Geist, C. (2005). The welfare state and the home: Regime differences in the domestic division of labour. European Sociological Review, 21(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci002

- Generations and Gender Surveys (GGS) Wave 1. https://www.ggp-i.org/data/

- Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. K. (2005). Supporting a dual-earner / dual-carer society. In J. Heymann & C. Beem (Eds.), Unfinished Work: Building Equality and Democracy in an Era of Working Families. New York: The New Press, pp. 371–408.

- Grunow, D., & Evertsson, M. (Eds.). (2019). New parents in Europe. Work-care practices, gender norms and family policies. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hewitt, B., Baxter, J., & Mieklejohn, C. (2012). Non-standard employment and fathers’ time in household labour. Journal of Family Studies, 18(2–3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2012.18.2-3.175

- Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Penguin.

- Hoem, J. M., Neyer, G., & Andersson, G. (2006). Education and childlessness. The relationship between educational field, educational level and childlessness among Swedish women born in 1955–59. Demographic Research, 14, 331–380. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2006.14.15

- Hook, J. (2010). Gender inequality in the welfare state: Sex segregation in housework, 1965–2003. American Journal of Sociology, 115(5), 1480–1523. https://doi.org/10.1086/651384

- Koslowski, A., Blum, S., Dobrotić, I., Macht, A., & Moss, P. (Eds.). (2019). International review of leave policies and research 2019. https://www.leavenetwork.org/fileadmin/user_upload/k_leavenetwork/annual_reviews/2019/2._2019_Compiled_Report_2019_0824-.pdf

- Lappegård, T., & Rønsen, M. (2005). The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population, 21(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-004-6756-9

- Leitner, S. (2010). Germany outpaces Austria in childcare policy. The historical contingencies of ‘conservative’ childcare policy. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(5), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710380482

- Lesthaeghe, R., & Moors, G. (2002). Life course transitions and value orientations: Selection and adaptation. In R. Lesthaeghe (Ed.), Meaning and choice: Value orientations and life course decisions (pp. 1–44). NIDI/GBGS Publication, Monograph 37.

- Marsiglio, W., Amato, P., Day, R. D., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1173–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01173.x

- Martín-García, T., & Baizán, P. (2006). The impact of the type of education and of educational enrolment on first births. European Sociological Review, 22(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci056

- Martín-García, T., Seiz, M., & Castro-Martín, T. (2017). Women’s and men’s education and partnership formation: Does the field of education matter? European Sociological Review, 33(3), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx047

- Mathieu, S. (2016). From the defamilialization to the ‘demotherization’ of care work. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 23(4), 576–591. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxw006

- Musumeci, R., & Santero, A. (Eds.). (2018). Fathers, childcare and work: Cultures, practices and policies. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Ochsenfeld, F. (2014). Why do women’s fields of study pay less? A test of devaluation, human capital, and gender role theory. European Sociological Review, 30(4), 536–548. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu060

- Oppermann, A. (2014). Exploring the relationship between educational field and transition to parenthood – an analysis of women and men in western Germany. European Sociological Review, 30(6), 728–749. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu070

- Pailhé, A., Solaz, A., & Stanfors, M. (2021). Gender and unpaid work in Europe and the United States. Population and Development Review, 47(1), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12385

- Pleck, J. H. (2010). Paternal involvement: Revisited conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In M. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed.) (pp. 67–107). John Wiley & Sons.

- Riederer, B., Buber-Ennser, I., & Brzozowska, Z. (2019). Fertility intentions and their realization in couples: How the division of household chores matters. Journal of Family Issues, 40(13), 1860–1882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19848794

- Risman, B. (2004). Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender & Society, 18(4), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265349

- Solera, C., & Mencarini, L. (2018). The gender division of housework after the first child: A comparison among Bulgaria, France and the Netherlands. Community, Work and Family, 21(5), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1528969

- Steiber, N., Berghammer, C., & Haas, B. (2016). Contextualizing the education effect on women's employment: A cross-national comparative analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12256

- Sullivan, O. (2013). What do we learn about gender by separating housework from childcare? Some considerations from time use evidence. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(2), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12007

- Sullivan, O. (2021). The gender division of housework and child care. In N. F. Schneider & M. Kreyenfeld (Eds.), Research handbook of the sociology of the family (pp. 342–354). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sullivan, O., Billari, F. C., & Altintas, E. (2014). Father’s changing contributions to child care and domestic work in very low-fertility countries: The effect of education. Journal of Family Issues, 35(8), 1048–1065. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522241

- Szelewa, D., & Polakowski, M. P. (2008). Who cares? Changing patterns of childcare in central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 18(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928707087589

- Van Bavel, J. (2010). Choice of study discipline and the postponement of motherhood in Europe: The impact of expected earnings, gender composition, and family attitudes. Demography, 47(2), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0108

- Van der Lippe, T., de Ruijter, J., de Ruijter, E., & Raub, W. (2011). Persistent inequalities in time use between men and women: A detailed look at the influence of economic circumstances, policies, and culture. European Sociological Review, 27(2), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp066