ABSTRACT

In this study, we tested a model connecting the spouses’ assessment of the division of domestic labour and their marital satisfaction. The suggested model was tested in a dyadic study using a sample of heterosexual couples living in Israel and having at least one child (n = 479). The spouses assessed the division of domestic labour in four domains: traditionally feminine chores, traditionally masculine chores, childcare, and emotion work. Husbands who reported doing fewer traditionally feminine chores and less emotion work were more satisfied with their marriage. Wives who reported doing fewer traditionally masculine chores and less childcare and emotion work were more satisfied with their marriage. Simultaneously, husbands who reported doing fewer masculine chores and less emotion work tended to have wives with higher levels of marital satisfaction. Wives who reported doing fewer feminine chores and less emotion work tended to have husbands with higher levels of marital satisfaction. Husbands and wives reported similar levels of marital satisfaction, and their levels of marital satisfaction were strongly positively correlated. The obtained results indicated the existence of two mechanisms connecting the division of domestic labour to marital satisfaction: an egoistic mechanism and the gratitude mechanism.

Marital satisfaction is an essential component of well-being for married or those living with a partner (Karney & Bradbury, Citation2020; Otero et al., Citation2020). It is also crucial for society because happily married individuals provide better care for their children, are more successful in their jobs, have more friends, and volunteer more (Bae & Doh, Citation2020; Cerrato & Cifre, Citation2018; Piechota et al., Citation2022; Xie et al., Citation2018). However, the level of satisfaction in marriages has declined over the last fifty years, and the divorce level has increased (Tavakol et al., Citation2017) Today, in developed countries, 40-50% of first marriages end in permanent separation or divorce (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, Citation2021). Numerous studies have indicated that marital dissatisfaction is one of the reasons for divorce (Putnam, Citation2011; Schoen et al., Citation2002; Waite et al., Citation2002). Therefore, research on the factors affecting marital satisfaction is theoretically and practically important.

In this study, we investigated the role of the division of domestic labour on the spouses’ marital satisfaction. The effect of the division of domestic labour on marital satisfaction has been investigated previously; however, most previous studies have been conducted among men and women separately (Coltrane, Citation2000; Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006). In the present study, we used a dyadic design and analyzed our data using the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM, Kenny et al., Citation2006). This approach permitted us to investigate how each spouse’s assessment of the division of domestic labour in the family affects not only his or her marital satisfaction but also the marital satisfaction of his or her partner.

Division of domestic labour

Domestic labour refers to unpaid work to maintain family members and the home (Coltrane, Citation2000). This concept includes household management, childcare, and emotion work. Household management is further divided into traditionally feminine, e.g. food preparation, tidying, shopping, and laundry, and traditionally masculine chores, e.g. lawn care, car washing, car maintenance, and household repairs (Coltrane, Citation2000). Emotion work refers to ‘activities concerned with the enhancement of others’ emotional well-being and the provision of emotional support’ (Erickson, Citation2005, p. 338). This conceptualization of emotion work captures people’s attempts to manage the positive emotional climate within a relationship. Emotion work includes offering encouragement, showing appreciation, listening closely to what the other spouse says, and expressing empathy for another spouse’s feelings (Erickson, Citation2005).

In all countries, women perform twice as much domestic labour as men; however, the proportion differs across domestic labour domains. The average married American woman does about three times more traditionally feminine chores than the man, 32 vs. 10 h per week, and the average married man does about twice more traditionally masculine chores than the woman, 10 vs. 6 h per week (Sullivan, Citation2018). During the last fifty years, American men have doubled their domestic labour hours, while women have cut their domestic labour hours almost in half; however, American women still spend nearly twice as much time on domestic labour as men (García Román, Citation2021).

The connection between the division of domestic labor and marital satisfaction

Two theories explain the connection between the division of domestic labour and marital satisfaction: the power theory and the companionate theory of marriage (Coltrane, Citation2000; Erickson, Citation2005; Hochschild, Citation2003). These theories are based on different assumptions, and their predictions are mutually exclusive. The power theory of marriage considers domestic work unpleasant and, therefore, assumes that when a spouse does a lesser part of domestic work, they feel that the marriage enables them to achieve their goals – to do less of the unpleasant domestic work. Therefore, the spouse is more satisfied with their marriage. The theory further assumes that a more powerful spouse participates less in domestic labour and experiences higher marital satisfaction because the other spouse does a larger part of the unpleasant work. Finally, the theory claims that since men have more power in society, they participate less in domestic labour and experience higher marital satisfaction than women.

The second is the companionate theory of marriage (Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006). This theory stipulates two complementary assumptions: 1) The exercise of authority and power associated with inequality in the division of domestic labour is associated with a larger social distance and, therefore, more frequent conflicts in the family. On the other hand, more equal family relationships are characterized by more interpersonal closeness, trust, communication, and mutuality, which may increase the marital satisfaction of both spouses. 2) Sharing domestic labour is supposed to increase the quality of relationships by providing husbands and wives with shared experiences and interests around which they can build conversations, empathetic regard, and mutual understanding. The companionate theory of marriage further assumes that when one spouse senses that the other bears a larger share of domestic labour, he/she is grateful and expresses his/her gratitude by different means that make his/her spouse happier in the relationship. On the other hand, less equal division of domestic labour leads to unhappiness in the spouse who does the larger part. In turn, he or she makes his/her spouse unhappy (Bahr & Bahr, Citation2001; Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006). Thus, the companionship theory predicts a positive connection between equality in the division of domestic labour and marital satisfaction for both husbands and wives. The theory further assumes that the spouses’ marital satisfaction levels should be similar because the inequality in the levels of marital satisfaction contradicts the principles of mutuality and companionship that, according to this theory, govern family relations (Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006).

Studies conducted in different cultures have found that a more equal division of domestic labour, i.e. greater participation of husbands and lesser participation of wives in domestic work, was associated with the wives’ higher marital satisfaction (Bahmani et al., Citation2013; Lavee & Katz, Citation2003; Qian & Sayer, Citation2016; Yoo, Citation2022). Thus, previous studies corroborated the power theory of marriage for wives. For husbands, most studies did not find a connection between participation in domestic labour and marital satisfaction (for rare exemptions, see Coltrane, Citation2000); thus, they did not support either the power or companionate theories of marriage (Coltrane, Citation2000; Erickson, Citation2005; Hochschild, Citation2003; Qian & Sayer, Citation2016). However, all these studies analyzed data for wives and husbands separately, each time including the variables reported by one spouse and excluding the variables reported by the other spouse. The only study that included the variables of husbands and wives in the analysis (Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006) found that when wives sensed that the division of domestic labour was unfair either for them or their husbands, marital satisfaction of both husbands and wives was lower. Thus, the study results supported the companionate theory. However, this study used multiple regressions for statistical analyses. This method does not account for the dependency of data obtained from husbands and wives and, therefore, might lead to incorrect results.

In all countries, wives do a much higher share of domestic work than husbands; however, most studies found either no or only a minimal difference between the spouses’ levels of marital satisfaction (Wendorf et al., Citation2011). Moreover, all studies found a high positive correlation between the levels of marital satisfaction of the spouses (Bradbury et al., Citation2000; Jackson et al., Citation2014; Lawrence et al., Citation2008; Rabin & Shapira-Berman, Citation1997; Stevens et al., Citation2005; Wilkie et al., Citation1998). These findings support the companionate theory of marriage.

Summarizing, we may note that the results of empirical studies are inconsistent: some support the power theory, while others support the companionate theory of marriage. Moreover, the results often differ for husbands and wives. However, it is important to note that in most previous studies, the connection between the division of domestic labour and marital satisfaction has been tested separately for husbands and wives (Lavee & Katz, Citation2003; Qian & Sayer, Citation2016; Yoo, Citation2022). Therefore, the effects of one spouse’s assessment of the division of domestic labour on the marital satisfaction of the other spouse have not been investigated.

Theoretical model and main hypotheses of the present study

In the present study, we measured the husbands’ and wives’ assessments of their shares in domestic labour using a dyadic design. This design permitted us to investigate how the wives’ and husbands’ assessments of the division of domestic labour are connected to the spouses’ marital satisfaction. We analyzed our data using the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM, Kenny et al., Citation2006). In the APIM, variables representing both spouses are included in the analysis, reflecting potential reciprocity in relationships. Thus, we could examine how each spouse’s assessment of the division of domestic labour affects his/her marital satisfaction and the marital satisfaction of the partner. The following three hypotheses were formulated:

Following the companionate theory of marriage and the results of previous studies (Bae & Doh, Citation2020; Bahr & Bahr, Citation2001; Bradbury et al., Citation2000; Otero et al., Citation2020), we hypothesized that the spouses’ marital satisfaction levels would be similar and positively correlated.

Following the power theory of marriage (Hochschild, Citation2003), we hypothesized that for each spouse, his/her lower assessment of his/her share in domestic labour would be associated with his/her higher level of marital satisfaction.

Following the companionate theory of marriage (Bahr & Bahr, Citation2001; Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006), we hypothesized that for each spouse, his/her lower assessment of his/her share in domestic labour would be associated with a higher level of marital satisfaction of his/her spouse.

Method

Sample

Four hundred seventy-nine heterosexual couples participated in the study. presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, separately for husbands and wives. On average, the couples were married for 14.5 years and had 2 or 3 children. For about 90% of the participants, it was their first marriage. On average, husbands were slightly older than wives (40.8 vs. 38.4). The level of wives’ education was similar to that of their husbands (71% of wives and 67% of husbands had tertiary education). In addition, there was no difference in the wives’ and husbands’ levels of religiosity (2.35 vs. 2.31 on a 5-point scale). However, on average, the per-hour salary of wives was lower than that of husbands ($18 vs. $22 NIS). Also, wives worked fewer hours per week (35.5 vs. 45.4), and their monthly net salary was lower ($2,439 vs. $3,759).

Table 1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Sample.

To assess whether the sample was representative, we compared its sociodemographic characteristics with those of the Jewish population in Israel (CBS, Citation2020). The sample differed significantly from the population in several sociodemographic characteristics. Compared to the population, a higher proportion of the study participants were born in Israel (86% vs. 75%). The study participants were more educated (70% vs. 37% having tertiary education), less religious (68% vs. 44% secular), and had fewer children (2.27 vs. 3.09). The study participants worked more hours per week, both men (45.4 vs. 42) and women (35.5 vs. 33.1), and their net monthly income was higher than the population for both men ($3,758 vs. $3,175) and women ($2.439 vs. $2.125). Thus, the sample over-represented the middle-class, well-educated, and secular part of Jewish Israeli society.

Procedure

The Tel-Aviv University Review Board approved the study. Students participating in a senior research seminar distributed the questionnaires to their acquaintances, personally or through e-mail. Students participating in the seminar lived in different areas of Israel, thus ensuring a geographically heterogeneous sample. Heterosexual couples married or living together and having at least one child were invited to participate in the study. The anonymity of the participants was ensured, and measures were taken to guarantee the confidentiality of the participants’ reports (e.g. the participants were instructed to complete the questionnaire privately, not to discuss it with their spouse, and to hand or mail it directly to the interviewer). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Instruments

Division of domestic labour. Division of domestic labour was measured in four domains: traditionally feminine chores (5 items; e.g. preparing meals), traditionally masculine chores (4 items; e.g. household maintenance), childcare (11 items; e.g. playing with the children), and emotion work (14 items; e.g. offering encouragement). The items were adopted from the questionnaires developed by Demo and Acock (Citation1993) and Erickson (Citation2005). The participants were asked to assess who does the work on a 7-point scale, from 1 (only me) to 4 (me and my partner to an equal degree) to 7 (only my partner). The mean score was calculated for each domestic labour domain separately for husbands and wives. The wives’ answers were reversed; thus, for both spouses, a lower score means a larger share of husbands, and a higher score indicates a larger share of wives in domestic labour. Cronbach’s alphas for the four domains of domestic labour were as follows for husbands/wives: traditionally female chores .76/ .78, traditionally male chores .85/ .84, childcare .85/ .84, and emotion work .89/ .86.

Marital satisfaction. Marital satisfaction was measured by The Satisfaction with Married Life Scale, SWML (Johnson et al., Citation2006). The SWML is a modified version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Citation1985), in which the word ‘life’ was replaced by ‘married life.’ The SWML requires participants to agree or disagree with five statements about married life on a seven-point scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item is, ‘In most ways, my married life is close to ideal.’ The scale’s validity and reliability were confirmed in previous studies (Johnson et al., Citation2006; Ward et al., Citation2009). In the present study, the internal consistency of the SWML, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was .93 for both husbands and wives.

Data analysis

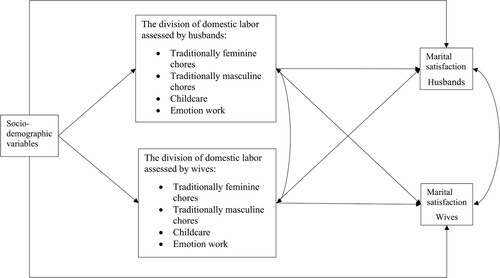

We analyzed our data using the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM, Kenny et al., Citation2006). In our study, the APIM includes variables representing both spouses, thus reflecting potential reciprocity in relationships where each spouse may influence his/her partner. presents the research model, which includes the husbands’ and wives’ assessments of their shares in the four types of domestic labour and the spouses’ marital satisfaction. Four sociodemographic characteristics of husbands and wives (age, education, weekly work hours, and the number of children in the family) were included in the model as control variables. They were connected to the spouses’ assessment of the division of domestic labour in four domains and marital satisfaction. Other sociodemographic variables were not correlated with marital satisfaction or division of domestic labour in the sample; therefore, they were not included in the research model.

Following the rule of 10–15 cases per variable, the number of couples in the sample (n = 479) was enough to cover the number of variables in the analyzed model (Geiser, Citation2012; Kelloway, Citation2014). In addition, we used the A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models to calculate the minimum required number of cases for testing our model (https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89). The minimum recommended sample size was 232, indicating that our sample was enough to test the research model.

Research hypotheses related to the connections between the study variables were tested by Structural Equation Modelling using Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2012). Full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to deal with missing data (Little & Rubin, Citation2019). The covariance structure of the model was evaluated with multiple fit indexes, and the following values were regarded as indicating a good fit: CFI > .95, TLI > .95, RMSEA < .05, and SRMR < .05 (Geiser, Citation2012; Kelloway, Citation2014).

Results

presents descriptive statistics for husbands and wives. On average, husbands and wives had a similar level of marital satisfaction (M(SD)H = 5.30(1.20); M(SD)W = 5.24(1.22); t(478) = 1.21; p = .227), and their marital satisfaction scores were highly positively correlated (r = .63, p < .001). Thus, the first hypothesis of the study was confirmed.

Table 2. Pearson Correlation Coefficients, Means, and Standard Deviations.

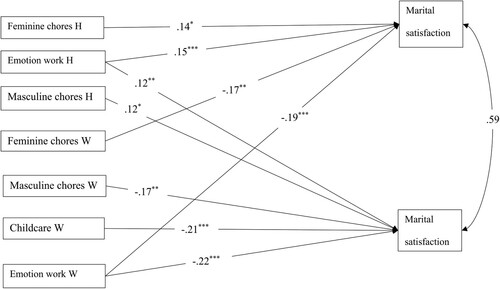

The research model demonstrated excellent fit: χ2(27) = 49.7, p = .005; RMSEA (CI) = .042 (.023; .060); CFI = .986; TLI = .939; SRMR = .029. The proportion of variance explained in the marital satisfaction was 10% for husbands and 14% for wives. presents standardized estimates, standard errors, and p-values for all connections in the model. presents all significant connections between variables in the model. To avoid clattering, connections with sociodemographic variables are not presented.

Figure 2. The Research Model (Significant Effects).

Note: H - husband’s assessment of the division of domestic labour, W – wives’ assessment of the division of domestic labour. Positive coefficients indicate a larger share of wives; negative coefficients indicate a larger share of husbands in the division of domestic labour.

Table 3. Standardized Estimates, Standard Errors, and P-Values for All Connections in the Research Model.

The study’s second hypothesis claimed negative connections between the shares in all domains of domestic labour as assessed by a spouse and his/her marital satisfaction. The results demonstrated that husbands who reported doing fewer traditionally feminine chores (β = .14, p = .037) and less emotion work (β = .15, p = .001) reported higher levels of marital satisfaction. In addition, wives who reported doing fewer traditionally masculine chores (β = -.17, p = .003), less childcare (β = -.21, p < .001), and emotion work (β = -.22, p < .001) reported higher levels of marital satisfaction. Thus, the study’s second hypothesis was partially confirmed for both husbands and wives.

The third hypothesis claimed that each spouse’s lower assessments of his/her share in domestic labour would be associated with higher levels of marital satisfaction of his/her spouse. The results demonstrated that husbands who reported doing fewer traditionally masculine chores (β = .12, p = .028) and less emotion work (β = .12, p = .011) tended to have wives with higher levels of marital satisfaction. In addition, wives who reported doing fewer traditionally feminine chores (β = -.17, p = .010) and less emotion work (β = -.19, p < .001) tended to have husbands with higher levels of marital satisfaction. Thus, the third hypothesis of the study was partly confirmed for both husbands and wives.

To compare the effects of husbands’ and wives’ assessments of the division of domestic labour in different domains on the spouses’ marital satisfaction, we compared two models – one with the equality constraint and another – without (Ledermann et al., Citation2011). The husbands’ and wives’ assessments of the division of domestic labour in all domains had similar effects on the husbands’ marital satisfaction. However, the husbands’ and wives’ assessments of the division of domestic labour in two domains had significantly different effects on the wives’ marital satisfaction: childcare (Difference Estimate = .261, SE = .091, p = .004) and emotion work (Difference Estimate = .259, SE = .130, p = .047). In both domains, the wives’ assessment of the division of domestic labour affected the wives’ marital satisfaction more than the husbands’ assessment did.

The effect of sociodemographic variables on the division of domestic labour in several domains was significant. The older age of husbands was associated with a larger share of wives in emotion work as reported by wives (β = .48, p = .001), and the older age of wives was associated with a larger share of husbands in emotion work as reported by wives (β = -.42, p = .004). A larger number of children in the family was associated with a larger wives’ share in traditionally feminine chores, as reported by both husbands (β = .16, p = .001) and wives (β = .10, p = .037). The husbands’ higher level of education was associated with a larger share of husbands in childcare, as reported by both husbands (β = -.12, p = .012) and wives (β = -.14, p = .005). The wives’ higher level of education was associated with the husbands’ larger share in traditionally feminine chores, as reported by wives (β = -.20, p < .001), and with the husbands’ larger share in childcare, as reported by wives (β = -.14, p = .005). Longer work hours of husbands were associated with the husbands’ larger self-reported share in emotion work (β = -.12, p = .007), masculine chores (β = -.11, p = .030), and a smaller self-reported share in traditionally feminine chores (β = .17, p < .001), self-reported childcare (β = .24, p < .001), and wife-reported childcare (β = .13, p = .007). Finally, longer working hours of wives were associated with the wives’ smaller self-reported share in traditionally feminine chores (β = -.17, p < .001), traditionally masculine chores (β = -.15, p = .003), childcare (β = -.16, p = .001), and emotion work (β = -.13, p = .008).

The indirect effects of several sociodemographic variables on the spouses’ marital satisfaction were significant. Higher wives’ education was associated with higher marital satisfaction among husbands (β = .050, p = .010). Higher wives’ education was associated with higher marital satisfaction among wives (β = .058, p = .006). Finally, the older husband’s age was associated with lower marital satisfaction among wives (β = -.133, p = .020).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated connections between husbands’ and wives’ assessments of the division of domestic labour and their levels of marital satisfaction. We based our study on the companionate and power theories of marriage and used a dyadic design to account for the mutual influence of the spouses in the family.

The results demonstrated that husbands and wives had a similar level of marital satisfaction. Moreover, the spouses’ levels of marital satisfaction were strongly positively correlated. These findings reflect the spouses’ interdependence and demonstrate that a spouse cannot be happy at the other spouse’s expense. Thus, these results support the companionate theory and contradict the power theory of marriage (Bae & Doh, Citation2020; Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006).

For each spouse, one’s smaller self-assessed share in the division of domestic labour was associated with a higher level of one’s marital satisfaction. Specifically, husbands who reported doing fewer traditionally feminine chores and less emotion work were more satisfied with their marriage. In addition, wives who reported doing fewer traditionally masculine chores, less childcare, and less emotion work were more satisfied with their marriage. Thus, the results obtained corroborated the power theory of marriage, which claims that each spouse strives to do as little domestic labour as possible, and those who do less are more satisfied with their marriage (Bahmani et al., Citation2013; Coltrane, Citation2000; Hochschild, Citation2003; Rabin & Shapira-Berman, Citation1997).

However, the results also indicated that not all domains of domestic labour were equally important for the spouses’ marital satisfaction. Specifically, the self-assessment of one’s share in traditionally masculine chores did not affect husbands’ marital satisfaction, and the self-assessment of one’s share in traditionally feminine chores did not affect wives’ marital satisfaction. These results probably indicate that each spouse accepts the socially normative inequality in these domains of domestic labour. Therefore, their share in these domains does not affect their marital satisfaction.

Interestingly, the self-assessed division in childcare was not related to marital satisfaction among husbands. Cultural norms may explain this finding. Israel is a country with a high level of gender equality (Fuwa, Citation2004). It is also a child-oriented country with significant involvement of both spouses in childcare (Bystrov, Citation2012; Lavee & Katz, Citation2003; Okun, Citation2013). The high value of children and the normative involvement of husbands in childcare may explain why the larger share of Israeli husbands in childcare does not decrease their marital satisfaction. This finding also corroborates previous studies that demonstrated that childcare is a source of joy and pride for many fathers, and thus it may be associated with their marital satisfaction (Trahan & Cheung, Citation2012).

Confirming our hypothesis, for each spouse, one’s smaller self-assessed share in the division of domestic labour was associated with a higher level of marital satisfaction for the other spouse. Specifically, husbands who reported doing fewer masculine chores and less emotion work tended to have wives with higher levels of marital satisfaction. In addition, wives who reported doing fewer feminine chores and less emotion work tended to have husbands with higher levels of marital satisfaction. Thus, the obtained results corroborated the companionate theory of marriage that assumes that when one spouse senses that the other bears a larger share of domestic labour, they feel gratitude and finds various ways to express this gratitude, thus making the other spouse happier in the relationships (Bahr & Bahr, Citation2001; Horne et al., Citation2018; Wilcox & Nock, Citation2006).

The obtained results corroborated our assumption regarding the simultaneous existence of two mechanisms connecting the division of domestic labour and the spouses’ marital satisfaction. The first is an egoistic mechanism (Kroska, Citation2003). When a spouse feels relief from domestic labour (i.e. they assess that their partner bears a larger share of domestic labour), they are more satisfied with the marriage. The second mechanism is the gratitude mechanism, which in a previous study has been called ‘an enchanted logic of gift exchange’ (Bahr & Bahr, Citation2001, p. 1243). This mechanism assumes that the sense of relief from domestic labour (when one spouse senses that the other spouse bears a larger share of domestic work) may cause the first spouse to do something pleasant to the other spouse (e.g. to verbally express gratitude, give presents, or provide more emotional support), which makes the second spouse more satisfied with her/his marriage. In the present study, we did not investigate how the gratitude mechanism works. Further research is required to understand better the phenomena found in the present study.

The results of our study indicate that both egoistic and gratitude mechanisms are essential for the spouses’ marital satisfaction because, in most domains of domestic labour, the differences between the effects of the husbands’ and wives’ assessment of the division of household labour on marital satisfaction were not significant. However, in two domains of domestic work, childcare and emotion work, the wives’ assessment had a stronger effect on their marital satisfaction than the husbands’ assessment. This finding may indicate the pivotal role of these two domains in women’s family life. However, further studies on this issue are required.

The spouses’ sociodemographic variables affected the division of domestic labour in several domains. The spouses’ age was associated with their share in emotion work, as assessed by wives: an older age of husbands was associated with a larger share of wives, while an older age of wives was associated with a larger share of husbands in emotion work. The larger number of children was associated with the wives’ larger share in traditionally feminine chores and thus increased inequality in this domain of domestic labour. The wives’ higher level of education was associated with a more equal division of work in traditionally feminine chores and childcare. Similarly, the husbands’ higher level of education was associated with a more equal division of labour in childcare. Finally, longer working hours for both wives and husbands were associated with their smaller shares in all domains of domestic labour. Similar to previous studies, these findings indicate that situational demands (e.g. the number of children), egalitarian ideology related to the spouses’ age and education, and time-availability/constraints of both wives and husbands affect the division of domestic labour in the family (Coltrane, Citation2000; Wiesmann et al., Citation2008; Yoo, Citation2022).

Two sociodemographic variables indirectly affected the spouses’ marital satisfaction through their effect on the division of domestic labour: wives’ education indirectly affected the marital satisfaction of both spouses (positively), and husbands’ age indirectly affected wives’ marital satisfaction (negatively). These findings indicate that the gender norms of participation in the division of domestic labour may be affected by education and age, and through them, they may affect marital satisfaction.

Limitations and suggestions for further research

Several limitations of this study must be considered. First, the study was correlational; therefore, causal inferences cannot be drawn from the obtained results. Future experimental or longitudinal research would substantially advance the current findings. The second limitation of the present study relates to its sample, which, although large, was not random and was drawn from a specific population. Further studies conducted in other countries or including different socio-economic, religious, and ethnic groups must test the results’ generalizability. The third limitation of the study relates to the measurement of the division of domestic labour. In the present study, we used the spouses’ subjective assessment of their shares in different domains of domestic work. Further studies may use other measurement instruments, e.g. daily diaries, to assess how much time each spouse spends doing different domestic work. In addition, measurements of some domains of domestic labour probably needed to be more specific. This might be especially relevant for the childcare scale, which measured care for children of different ages. Finally, further studies may include psychological variables (e.g. value preferences, self-esteem, communication styles, variables related to social exchange in the family, and general satisfaction with life) as mediating or moderating the connection between the division of domestic labour and the spouses’ marital satisfaction.

Conclusion

The present study advanced our understanding of family processes by investigating the connection between the spouses’ subjective perception of the division of domestic labour and marital satisfaction. Using the actor-partner interdependence model, we demonstrated that one’s and the spouse’s perception of the division of domestic labour affect the marital satisfaction of each spouse. The present study resolves the contradiction between the power and companionate theories of marriage by revealing the previously unknown aspects of the connection between the division of domestic labour and marital satisfaction. Specifically, we demonstrated that the marriage satisfaction of each spouse depends not only on his/her assessment of the division of domestic labour in the family but also on the other spouse. These findings advance our understanding of the complex interaction processes in the family. In addition to their theoretical importance, they may be used in family counselling for resolving conflicts and increasing the spouses’ marital satisfaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bae, J. Y., & Doh, H. S. (2020). Actor-partner effects of marital satisfaction, happiness, and depression on parenting behaviors of parents with young children. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 41(3), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.5723/kjcs.2020.41.3.65

- Bahmani, M., Aryamanesh, S., Bahmani, M., & Gholami, S. (2013). Equity and marital satisfaction in Iranian employed and unemployed women. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 421–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.578

- Bahr, H. M., & Bahr, K. S. (2001). Families and self-sacrifice: Alternative models and meanings for family theory. Social Forces, 79(4), 1231–1258. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2001.0030

- Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 964–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00964.x

- Bystrov, E. (2012). The second demographic transition in Israel: One for all? Demographic Research, 27, 261–298. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.10

- Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01330

- Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1208–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x

- Demo, D. H., & Acock, A. C. (1993). Family diversity and the division of domestic labor: How much have things really changed? Family Relations, 42(3), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.2307/585562

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Erickson, R. J. (2005). Why emotion work matters: Sex, gender, and the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00120.x

- Fuwa, M. (2004). Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. American Sociological Review, 69(6), 751–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900601

- García Román, J. (2021). Couples’ relative education and the division of domestic work in France, Spain, and the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 52(2), 245–270. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs-52-2-005

- Geiser, C. (2012). Data analysis with Mplus. Guilford Press.

- Hochschild, A. R. (2003). The commercialization of intimate life: Notes from home and work. University of California Press.

- Horne, R. M., Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L., & Krahn, H. J. (2018). Time, money, or gender? Predictors of the division of household labour across life stages. Sex Roles, 78(11), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0832-1

- ICBS, Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Statistical Abstract of Israel 2019. https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/publications/Pages/2019/Statistical-Abstract-of-Israel-2019-No-70.aspx.

- Jackson, J. B., Miller, R. B., Oka, M., & Henry, R. G. (2014). Gender differences in marital satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(1), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12077

- Johnson, H. A., Zabriskie, R. B., & Hill, B. (2006). The contribution of couple leisure involvement, leisure time, and leisure satisfaction to marital satisfaction. Marriage & Family Review, 40(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v40n01_05

- Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2020). Research on marital satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: Challenging conventional wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12635

- Kelloway, E. K. (2014). Using Mplus for structural equation modeling: A researcher’s guide. Sage Publications.

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford.

- Kroska, A. (2003). Investigating gender differences in the meaning of household chores and child care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 456–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00456.x

- Lavee, Y., & Katz, R. (2003). The family in Israel: Between tradition and modernity. Marriage & Family Review, 35(1-2), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v35n01_11

- Lawrence, E., Bunde, M. A. L. I., Barry, R. A., Brock, R. L., Sullivan, K. T., Pasch, L. A., White, G. A., Dowd, C. E., & Adams, E. E. (2008). Partner support and marital satisfaction: Support amount, adequacy, provision, and solicitation. Personal Relationships, 15(4), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00209.x

- Ledermann, T., Macho, S., & Kenny, D. A. (2011). Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor-partner interdependence model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(4), 595–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.607099

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (Vol. 793). John Wiley & Sons.

- Marini, M. M., & Shelton, B. A. (1993). Measuring household work: Recent experience in the United States. Social Science Research, 22(4), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1993.1018

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). MPlus user’s guide (7th edition).

- Okun, B. S. (2013). Fertility and marriage behavior in Israel: Diversity, change, and stability. Demographic Research, 28, 457–504. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.17

- Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2021). Marriages and divorces. https://ourworldindata.org/marriages-and-divorces.

- Otero, M. C., Wells, J. L., Chen, K. H., Brown, C. L., Connelly, D. E., Levenson, R. W., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2020). Behavioral indices of positivity resonance associated with long-term marital satisfaction. Emotion, 20(7), 1225. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000634

- Piechota, A., Ali, T., Tomlinson, J. M., & Monin, J. K. (2022). Social participation and marital satisfaction in mid to late life marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(4), 1175–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211056289

- Putnam, R. R. (2011). First comes marriage, then comes divorce: A perspective on the process. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52(7), 557–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2011.615661

- Qian, Y., & Sayer, L. C. (2016). Division of labor, gender ideology, and marital satisfaction in East Asia. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(2), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12274

- Rabin, C., & Shapira-Berman, O. (1997). Egalitarianism and marital happiness: Israeli wives and husbands on a collision course? The American Journal of Family Therapy, 25(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926189708251076

- Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., Rothert, K., & Standish, N. J. (2002). Women’s employment, marital happiness, and divorce. Social Forces, 81(2), 643–662. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0019

- Stevens, D. P., Kiger, G., & Mannon, S. E. (2005). Domestic labor and marital satisfaction: How much or how satisfied? Marriage & Family Review, 37(4), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v37n04_04

- Sullivan, O. (2018). The gendered division of household labor. In B. J. Risman Handbook of the sociology of gender (pp. 377–392). Springer.

- Tavakol, Z., Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A., Behboodi Moghadam, Z., Salehiniya, H., & Rezaei, E. (2017). A review of the factors associated with marital satisfaction. Galen Medical Journal, 6(3).

- Trahan, M. H., & Cheung, M. (2012). Fathering behavior within the context of role expectations and marital satisfaction: Framework for studying fathering behavior. Journal of Family Strengths, 12(1), 1–24.

- Waite, L. J., Browning, D., Doherty, W. J., Gallagher, M., Luo, Y., & Stanley, S. M. (2002). Does divorce make people happy? Findings from a Study of Unhappy Marriages. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Linda-Waite/publication/237233376_Does_Divorce_Make_People_Happy_Findings_From_a_Study_of_Unhappy_Marriages/links/00b4953c8f423514b7000000/Does-Divorce-Make-People-Happy-Findings-From-a-Study-of-Unhappy-Marriages.pdf.

- Ward, P. J., Lundberg, N. R., Zabriskie, R. B., & Berrett, K. (2009). Measuring marital satisfaction: A comparison of the revised dyadic adjustment scale and the satisfaction with married life scale. Marriage & Family Review, 45(4), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494920902828219

- Wendorf, C. A., Lucas, T., Imamoğlu, E. O., Weisfeld, C. C., & Weisfeld, G. E. (2011). Marital satisfaction across three cultures: Does the number of children have an impact after accounting for other marital demographics? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(3), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362637

- Wiesmann, S., Boeije, H., van Doorne-Huiskes, A., & Den Dulk, L. (2008). ‘Not worth mentioning’: The implicit and explicit nature of decision-making about the division of paid and domestic work. Community, Work & Family, 11(4), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800802361781

- Wilcox, W. B., & Nock, S. L. (2006). What’s love got to do with it? Equality, equity, commitment and women’s marital quality. Social Forces, 84(3), 1321–1345. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0076

- Wilkie, J. R., Ferree, M. M., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1998). Gender and fairness: Marital satisfaction in two-earner couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 577–594. https://doi.org/10.2307/353530

- Xie, J., Zhou, Z. E., & Gong, Y. (2018). Relationship between proactive personality and marital satisfaction: A spillover-crossover perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 128, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.011

- Yoo, J. (2022). Gender role ideology, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and marital satisfaction among Korean dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues, 43(6), 1520–1535. doi:10.1177/0192513X211026966