ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted work and family life around the world. For parents, this upending meant a potential re-negotiation of the ‘status quo’ in the gendered division of labour. A comparative lens provides extended understandings of changes in fathers’ domestic work based in socio-cultural context – in assessing the size and consequences of change in domestic labour in relation to the type of work-care regime. Using novel harmonized data from four countries (the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands) and a work-care regime framework, this study examines cross-national changes in fathers’ shares of domestic labour during the early months of the pandemic and whether these changes are associated with parents’ satisfaction with the division of labour. Results indicate that fathers’ shares of housework and childcare increased early in the pandemic in all countries, with fathers’ increased shares of housework being particularly pronounced in the US. Results also show an association between fathers’ increased shares of domestic labour and mothers’ increased satisfaction with the division of domestic labour in the US, Canada, and the UK. Such comparative work promises to be generative for understanding the pandemic’s imprint on gender relations far into the future.

Introduction

Across industrialized countries, traditional gender norms emphasize mothers’ primary role as caregiver and fathers’ primary role as breadwinner. However, there is considerable flexibility – mothers have increased their time in paid work and fathers have increased their time in childcare and housework in recent decades (Bianchi et al., Citation2012; Dermott & Miller, Citation2015). Accordingly, support for mothers’ employment and increased father engagement at home has also strengthened (Dermott, Citation2008; Scarborough et al., Citation2019). Greater emphasis on father involvement is due in large part to the numerous benefits that paternal involvement has for fathers, mothers, and children (Chung, Citation2021; Lamb, Citation2010). For example, men’s involvement in, and more equal sharing of, domestic tasks is associated with greater relationship satisfaction (Carlson et al., Citation2016; Carlson et al., Citation2018; Schieman et al., Citation2018) and can help to facilitate mothers’ paid labour force participation (Petts et al., Citation2021). Despite the positive effects of father involvement and the desire for fathers to be more engaged parents, fathers still spend considerably less time on these tasks than mothers – contributing to a stalled gender revolution (Altintas & Sullivan, Citation2016; England, Citation2010; Goldscheider et al., Citation2015; Wishart et al., Citation2019).

The social contexts surrounding work and care became amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic represents a shock event that upended work and family life, potentially altering the ‘status quo’ in the division of domestic labour. Children were unable to attend school and all forms of nonparental childcare were largely unavailable. Many parents were also working from home, perhaps for the first time. This dramatically disrupted families’ routines, as there was more childcare to perform at home and more housework to do – often while balancing paid work responsibilities. Gendered parenting norms may have led to mothers shouldering a larger burden of this additional work given the expectations that they are primarily responsible for domestic labour. Yet, the pandemic also provided an opportunity for fathers to increase their shares of housework and childcare given their increased available time at home during the early days of the pandemic. Indeed, studies show that mothers increased their time spent in domestic tasks early in the pandemic, but fathers also spent more time in housework and childcare resulting in more equal divisions of domestic labour (Carlson et al., Citation2021b; Chung et al., Citation2021; Craig & Churchill, Citation2021; Shafer et al., Citation2020; Yerkes et al., Citation2020; see Waddell et al., Citation2021 for an exception).

Single-country studies suggest parallel trends of fathers doing more at home during the pandemic, perhaps due to similarities across conditions early in the pandemic (March–May 2020); schools were closed, workplaces were closed (or recommended to be closed) for all but essential workers and working from home was required or strongly recommended (Hale et al., Citation2021). But comparative analyses hold promise for increased understanding about the malleability of the gendered division of labour in the home. The gender gap in housework and childcare is linked to social policies associated with work and care (Nieuwenhuis & Van Lancker, Citation2020). As such, we expect the gender gap in domestic labour to vary across countries. The pandemic offered different opportunities and constraints for couples due to existing work-care policy frameworks and cultural norms around work and gender roles (Rush, Citation2015; Seward & Rush, Citation2016). These pre-existing differences across countries may have resulted in variation in the impact of the pandemic in changes in couples’ division of housework and childcare as well as how these changes were perceived by couples, with regards to satisfaction in the division of domestic work.

This study uses harmonized data from four countries with different work-care regimes (Crompton, Citation1999) – the United States (US), Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and the Netherlands – to examine potential cross-national variability in the extent to which fathers’ shares of domestic labour (e.g., housework and childcare tasks) changed during the early months of the pandemic. We also consider whether these changes are associated with parents’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour, and how this relationship may vary across countries. In doing so, this study considers how changes during the early pandemic may be experienced differently across contexts with different institutional support for work-care reconciliation and normative views towards father’s roles at home and in the labour market. These types of cross-national analyses deepen our understanding of how the intersection of broader cultural and institutional contexts shape family dynamics, here specifically relating to behavioural outcomes and attitudes towards gendered division of labour ideals (Rush, Citation2015; Seward & Rush, Citation2016).

Conceptual framework

Work-care regimes

To better understand potential variation in the division of domestic labour during the early pandemic and how it relates to satisfaction with the division of domestic labour across countries, we need to consider how employment and caregiving practices are embedded in the social and institutional fabric of our case countries – i.e., the work-care regimes within each country (Crompton, Citation1999). With respect to employment, all four case countries emphasize the importance of paid employment for both men and women (Gornick & Meyers, Citation2002; Lewis & Giullari, Citation2005), but key differences also exist. In the US and Canada, there is an emphasis on full-time work with over 75% of men and women in these countries working full-time as opposed to part-time (Statistics Canada, Citation2018; US Department of Labor, Citation2020). In contrast, the Netherlands has high rates of part-time work, with 70% of women (compared to 26% of men) working less than 35 h a week (van den Brakel et al., Citation2020). Dutch mothers are particularly likely to reduce their hours or stop working after the birth of the first child. The UK tends to reflect a mix of these patterns; long work hours are expected of fathers, while mothers generally work part-time or leave the labour market post-childbirth (Chung & Van der Horst, Citation2018).

Mothers are expected to perform the majority of childcare tasks in all four countries, yet there are variations in policies supporting caregiving roles. The US has no paid parental leave policy and no universal childcare system, subsidizing childcare largely through tax credits to parents (Palley & Shdaimah, Citation2014). In contrast, Canadian mothers have access to over one year of paid (combined maternity and parental) leave (Koslowski et al., Citation2021). The UK provides 9 months of paid leave for mothers, although income replacement rates are low. The UK further provides 30 h of free childcare for children over 3 years of age (for 38 weeks of the year, limited to working parents), yet childcare remains expensive for many families given the structure of the UK tax and benefit system (Koslowski et al., Citation2021). Similar childcare affordability issues exist in the Netherlands, where income-related childcare benefits are provided to working parents only (Yerkes & Javornik, Citation2019). The Netherlands offers comparatively short paid maternity leave of 16 weeks and 26 weeks of unpaid parental leave (Koslowski et al., Citation2021).

National policies that promote fathers’ engagement in childcare are limited or nonexistent across all four countries. There is no paid paternity leave policy in either the US or Canada (except in Québec), although fathers can share parental leave with mothers in Canada. Paid paternity leave in the UK is limited to 1–2 weeks, but fathers can take up unused maternity leave under the ‘Shared Parental leave’ scheme (Koslowski et al., Citation2021). Paid paternity leave of 1 week was introduced in 2019 in the Netherlands and extended to 5 weeks in 2020 with partial pay (70%). Fathers can also access up to 26 weeks of unpaid ‘gender neutral’ parental leave (Koslowski et al., Citation2021). The lack of policies supporting fathers’ engagement in childcare reinforce the idea that domestic labour is primarily mothers’ responsibility, although there are certainly more structural constraints to father involvement in the US and Canada as compared to the UK and the Netherlands.

Overall, these subtly different approaches to work and care translate to the UK and the Netherlands being classified as one-and-a-half-earner work-care regimes, emphasizing fathers’ primary role as breadwinners and secondary role as caregivers (Aboim, Citation2010; Yerkes & Hewitt, Citation2019). In contrast, the US and Canada most closely typify adult worker work-care regimes because care policies are more limited and work tends to be more strongly emphasized than care in these countries (although family supports exist to a larger extent in Canada than in the US) (Gornick & Meyers, Citation2002; Shafer et al., Citation2021). However, there are also variations within work-care regimes. For example, beliefs surrounding traditional gendered divisions of paid and unpaid labour (i.e., mothers should stay home or work part-time when children are young while fathers work full-time) in the UK (89% agree) are more similar to the US (81% agree) and Canada (76% agree) than to the Netherlands (52% agree) (ISSP, Citation2012). In the Netherlands, 44% of respondents agree part-time work for both parents is optimal, although in practice this ideal does not materialize (van den Brakel et al., Citation2020). Such norms, and work-care regimes more generally, may not only colour perceptions of what constitutes an equal division of housework, but may also link to how the gendered division of labour is associated with satisfaction with this division of labour (see also Milkie et al., Citation2002). Because a work-care regime framework acknowledges the role of cultural beliefs, policies, and practices (Collins, Citation2019), it is likely that the effects of the pandemic on parents’ division of labour is shaped by the norms and structural constraints both across and within work-care regimes.

The culture of fatherhood and father involvement

Limited structural support for father involvement across our four case countries is due in part to a persistent connection between hegemonic masculinities and ideal worker norms, suggesting that male workers should prioritize work over their family responsibilities (Acker, Citation1990; Connell, Citation2005; Williams, Citation1999). Male-breadwinner norms remain prevalent in many industrialized countries (Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, Citation2021; Thébaud, Citation2010) and many men believe that providing financially for children is central to a father’s role (Offer & Kaplan, Citation2021). So, even fathers who are motivated to be more involved at home may still feel the ‘pressure to be earning’ that work-centered cultures continue to elicit (Doucet & Merla, Citation2007, p. 463). This pressure to prioritize gendered work expectations exists in all our case countries but is likely most pronounced in adult worker work-care regimes. In adult worker regimes, such as the US and Canada, fathers face both structural and cultural barriers that limit their opportunities to be engaged in the domestic realm (Hook, Citation2006; Rush, Citation2015; Seward & Rush, Citation2016). Specifically, opportunities to take parental leave or other forms of time away from work to spend time with family (e.g. vacation time) are more limited in the US and Canada than they are in the UK or the Netherlands (Koslowski et al., Citation2021; Shafer et al., Citation2021).

At the same time, cultural norms and expectations around men’s domestic participation, especially related to father involvement, have shifted throughout Western countries. Norms increasingly emphasize fathers’ roles as engaged parents (Dermott, Citation2008; Doucet & Merla, Citation2007; Seward & Rush, Citation2016). Direct nurturance and emotional closeness are more closely associated with involved fathering (Dermott, Citation2008; Marsiglio & Roy, Citation2012), and fathers often desire to be with their children more than they are able to (Milkie et al., Citation2019). Unfortunately, an obstacle to acting on involved fathering norms, and a driver of these time deficits with children, is the lack of structural opportunities that enable fathers to spend more time at home (Rush, Citation2015). These differential opportunities are reflected in variations in men’s domestic involvement across work-care regimes. For example, the gender gap in time spent in unpaid labour is smaller in the Netherlands (men spend 35% less time doing unpaid work than women) than the US (39% less time for men than women) (OECD, Citation2021). Yet, there are also notable variations within work-care regimes; fathers are more engaged in domestic work in Canada as compared to the US due to greater family supports and less emphasis on traditional gender norms (Shafer et al., Citation2021), and the gender gap in time spent in domestic labour is particularly high in the UK (44% less time for men than women) due to traditional views on mothers’ and fathers’ roles (OECD, Citation2021). These variations suggest changes to fathers’ domestic participation during the pandemic may be uneven across countries due to structural and cultural variations.

Changes in domestic labor during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically disrupted work and family life across all four countries. In the early months of the pandemic (March 2020–May 2020), all four countries experienced a lockdown. This meant that schools and all formal childcare facilities were closed in each country (with only some small exceptions for those in essential occupations), increasing parents’ childcare responsibilities (Chung et al., Citation2021; Hale et al., Citation2021; Petts et al., Citation2021; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). Additionally, in all countries, non-essential workers were either required or strongly recommended to work from home (Hale et al., Citation2021). Consequently, a much greater proportion of parents across all four countries – 40–50 percent – worked from home early in the pandemic (Brynjolksson et al., Citation2020; Eurofound, Citation2020; Statistics Canada, Citation2020). However, there were also some variations across our case countries. For example, unemployment rates increased much more dramatically in the US and Canada than in the UK and the Netherlands due to variations in economic responses to the pandemic such as more generous furlough schemes in the European countries (Bennett, Citation2021). Overall, changes in the early pandemic likely led more parents to spend significantly more time at home – especially within the US and Canada.

These changes may have important implications for fathers’ involvement in domestic labour. On the one hand, gender norms emphasizing fathers’ responsibility for breadwinning and mothers’ responsibility for caregiving combined with higher rates of women’s unemployment in the US and Canada (Landivar et al., Citation2020; Oian & Fuller, Citation2020) may mean that the pandemic increased gender gaps in domestic labour. On the other hand, many men in the US and Canada also lost their jobs or were furloughed during the pandemic, and a large proportion across all four countries began working exclusively from home. Unemployment and remote work may increase fathers’ time availability, and thus provide fathers with the opportunity to spend more time with their family. Indeed, remote work both before and during the pandemic has been associated with increases in fathers’ domestic performance (Carlson et al., Citation2021a; Chung et al., Citation2021; Shafer et al., Citation2020; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). Although unemployment does not often translate to greater domestic work among men (e.g. Rao, Citation2020), this general trend may vary during particularly stressful times when multiple aspects of life are disrupted. Given that the pandemic disrupted all aspects of work and family life, parents may have been less likely to rely on gendered scripts to divide domestic labour and instead allocate work based on which parent has time to complete tasks – something that fathers had more of due to higher levels of remote work or unemployment. Indeed, there is evidence that men’s domestic labour increased in other crises such as the Great Recession despite high rates of unemployment (Berik & Kongar, Citation2013). Additionally, greater time at home may lead fathers to develop greater awareness of domestic demands, subsequently increasing their contributions and narrowing the gender gap in domestic labour (Shafer et al., Citation2020).

Recent evidence suggests that fathers’ involvement in housework and childcare increased in the early months of the pandemic across each case country (Carlson et al., Citation2021b; Chung et al., Citation2021; Shafer et al., Citation2020; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). Although mothers experienced substantial increases in time spent in domestic labour early in the pandemic, fathers’ time in these tasks also increased. Given that fathers spend considerably less time in housework and childcare than mothers, numerous studies (see Waddell et al., Citation2021 for an exception) show that fathers’ increased involvement at home resulted in smaller gender gaps in the division of domestic labour early in the pandemic (Carlson et al., Citation2021b; Chung et al., Citation2021; Craig & Churchill, Citation2021; Shafer et al., Citation2020; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). Comparatively, while there are some subtle differences, the numerous similarities in pandemic conditions (e.g. lockdowns, etc.) may have led to convergence in fathers’ domestic participation patterns across countries. However, the culture of part-time work among mothers in one-and-a-half-earner regimes (the Netherlands and UK) may have led to more stability in divisions of domestic labour during the pandemic because mothers had more time at home to begin with, compared to adult worker regimes that emphasize full-time work for all (US and Canada). Additionally, higher rates of unemployment in the US and Canada as compared to the Netherlands and UK may have contributed to more dramatic changes in the division of domestic labour. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1a: Fathers will perform a greater share of domestic labor early in the pandemic across all four countries.

H1b: This shift will be more pronounced in the US and Canada compared to the Netherlands and the UK.

Satisfaction with the division of domestic labor

Fathers’ involvement in domestic labour has consequences for both fathers’ and mothers’ relationships. Findings from the US, Canada, the UK and other OECD countries indicate that women rate their relationships as more equitable, report greater satisfaction with their divisions of labour, report greater closeness and communication, and are more satisfied with their relationships overall, when fathers are more involved in domestic work and when housework and childcare are shared more equally (Carlson et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Carlson et al., Citation2020; Hu & Yucel, Citation2018; Schieman et al., Citation2018; Schober, Citation2012). As such, we might also expect that a more equal division of domestic labour is associated with greater satisfaction with the division of domestic labour for mothers. Research is more equivocal regarding fathers’ feelings of satisfaction in egalitarian relationships, however. Men generally report that equal divisions are more equitable to both partners than other arrangements (Carlson et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). Nonetheless, compared to conventional divisions of labour, some studies show that men’s satisfaction with their overall relationship is greater in egalitarian relationships where domestic labour is more equally divided between partners (Carlson et al., Citation2016; Schieman et al., Citation2018), while others show no difference (Barstad, Citation2014; Blom et al., Citation2017; Carlson et al., Citation2018; Schober, Citation2012) or that men’s satisfaction is lower in relationships where they perform a greater share of domestic tasks (Wilkie et al., Citation1998). Thus, it is possible that fathers’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour may not necessarily be higher when fathers share domestic tasks equally with mothers.

The degree to which fathers’ greater participation in domestic labour during the pandemic is associated with increased satisfaction with the division of domestic labour may vary by work-care regime. Parallel with our first set of hypotheses, similarities in conditions across countries – and the stresses associated with these conditions – may lead to convergence in these associations, with parents across all four countries being more satisfied with how domestic labour is divided when fathers perform greater shares of domestic work during the pandemic (as parents may feel as though they are sharing the burdens and are ‘in it together’). However, such associations may also be more pronounced in adult worker work-care regimes where fathers were more likely to become unemployed early in the pandemic and where fathers’ greater involvement in these contexts may be more conspicuous and appreciated. That is, in the US and Canada (to a lesser extent), there are more structural constraints limiting fathers’ ability to be engaged in domestic labour as compared to the Netherlands and the UK. Interestingly, although the UK is classified as a one-and-a-half earner regime, attitudes surrounding care seem to be more similar to the US and Canada than the Netherlands (ISSP, Citation2012). As such, it is possible that the association between fathers’ increased shares of domestic labour and satisfaction with the division of domestic labour is more pronounced in the UK than in the Netherlands. Regardless, we hypothesize:

H2a: Increases in fathers’ shares of domestic labor will be associated with increases in parents’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labor across all four countries.

H2b: This association will be more pronounced in the US and Canada compared to the Netherlands and the UK.

Data and methods

Data

Data for this study comes from four separate surveys conducted in the US, Canada, the UK, and the Netherlands in the early months of the pandemic when lockdowns were common in all countries. The US survey was collected in April 2020 from Prolific, an opt-in online panel designed for academic surveys (N = 1,157 parents).Footnote1 Data from Canada were collected in May 2020 using a Qualtrics online panel (N = 1,245 parents). The UK survey was collected in May-June 2020 from Prolific, social media channels, and targeted partner organizations (N = 884 parents). Data for the Netherlands were collected in April 2020 from the LISS panel, a representative online panel (N = 868). Although only the Netherlands data is nationally representative, results using non-probability samples are often similar to those using probability samples after accounting for demographic variables (Levay et al., Citation2016). Ethics approval was obtained for each data collection from the appropriate institutions within each country (details available upon request). Data from each survey were harmonized and combined into a single dataset. The final sample was restricted to parents who resided with a spouse/partner and one or more children.Footnote2 Listwise deletion was used for missing data, resulting in a final sample of 3,307 parents (US = 968; Canada = 1128; UK = 676; the Netherlands = 535).

Variables

Division of domestic labor

Respondents reported on the division of domestic labour between themselves and their partners both before and during the pandemic. In the US, Canada, and UK surveys, respondents reported on a variety of tasks (e.g. laundry, cooking, reading to child, physical care) each with the following response options: 1 = I do/did it all; 2 = I do/did more of it; 3 = We share it equally; 4 = My partner did/does more of it; 5 = My partner did/does all of it.Footnote3 In the Dutch survey, respondents were asked summary questions about the division of housework and childcare (response options were: 1 = I did almost everything; 2 = I did a lot more than my partner; 3 = I did more than my partner 4 = We both did approximately the same share; 5 = My partner did more than me; 6 = My partner did a lot more than me; 7 = My partner did almost everythingFootnote4). To construct our measures, we created gendered indicators of the division of domestic labour before and during the pandemic based on respondents’ reports (ranging from 1 = mother does it all to 5 = father does it all). We then created a mean scale ranging from 1 to 5 (US, Canada, and UK respondents; single summary questions used for the Netherlands). In our analyses, we focused on the division of housework and childcare prior to the pandemic, with higher values indicating greater shares performed by fathers (these variables are only included in models predicting changes in the division of domestic labour). We also constructed indicators of change in housework/childcare during pandemic by subtracting the before-pandemic measures from the during-pandemic measures. We also created categories of the division of domestic labour both before and during the pandemic to classify couples as: (a) traditional, which is defined as mothers performing the majority of housework/childcare (scale score less than 2.6), (b) egalitarian, which equates to each parent contributing relatively equally (scale score 2.6–3.4), and (c) counter-conventional, which is defined as fathers performing most of the housework/childcare (scale score greater than 3.4).Footnote5

Satisfaction with division of domestic labor

In the US, Canada, and UK surveys, respondents reported on satisfaction with the division of housework and childcare before and during the pandemic (ranging from 0 = not at all satisfied to 10 = completely satisfied). We use information from these questions to construct indicators of satisfaction with division of housework and satisfaction with division of childcare prior to the pandemic.Footnote6 To assess change in satisfaction with division of housework/childcare, we constructed change scores similar to those for housework/childcare previously described. In the Dutch survey, respondents reported on disagreements with their partner about housework and childcare prior to the pandemic and how disagreements changed during the pandemic. We acknowledge that relationship conflict and satisfaction may coincide, particularly when partners are doing little (i.e. low satisfaction and low conflict), or that there may be high satisfaction and high conflict (e.g., with some mothers happy that fathers are doing more, but arguing more during the pandemic). But, previous empirical findings provide evidence that satisfaction and conflict are generally inversely related, and both satisfaction and conflict are commonly used to measure relationship quality. That is, higher quality relationships among couples exist when they argue less and are more satisfied (Carlson et al., Citation2018; Lavner, Citation2017; Suitor, Citation1991). To address the variations across the datasets, we recoded the questions from the Dutch survey so that higher values equated to less conflict (1 = almost daily to 5 = never for pre-pandemic; 1 = a lot more often to 5 = a lot less often for change during pandemic), and analyse the Dutch data separately for analyses focused on satisfaction with the division of labour to avoid conflating satisfaction with conflict (results are largely similar when analysed together using standardized measures; results available upon request).

Control variables

Control variables included respondent gender, age, relationship status (married vs. cohabiting), whether respondent has a college degree, age of youngest child, number of children, household income (standardized to US dollars), respondent’s essential worker status, parents’ employment status before the pandemic (both employed, mother employed and father not, father employed and mother not, both parents not employed), and parents’ work from home status during the pandemic (both can work from home, father can and mother cannot, mother can and father cannot, neither can work from home). Respondents in each survey were also asked questions about gender role attitudes (e.g., ‘it is a man’s job to earn money and a woman’s job to look after the home’), and our measure was coded such that higher values indicate more traditional attitudes. We accounted for country context by including dummy variables for each country (reference group: US), which equates to country-level fixed effects. Finally, in models predicting change, we included controls for pre-pandemic levels of each indicator to better assess change.

Analytic strategy

We first present a descriptive overview of how the division of domestic labour changed within each country during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. We then use OLS models to consider whether there are variations in changes in housework and childcare across countries and whether changes in parents’ division of housework and childcare are associated with changes in parents’ satisfaction with the division of each type of domestic labour. Finally, we incorporate interaction terms to consider whether the association between parents’ division of domestic labour and parents’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour varies across the three countries with similar measures (US, Canada, and UK). We present separate models for the Netherlands, which focus on conflict about the division of domestic labour.

Results

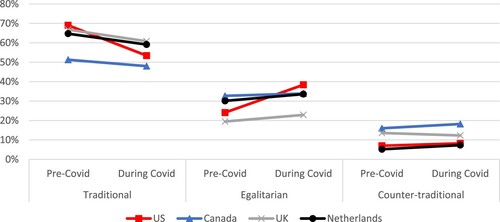

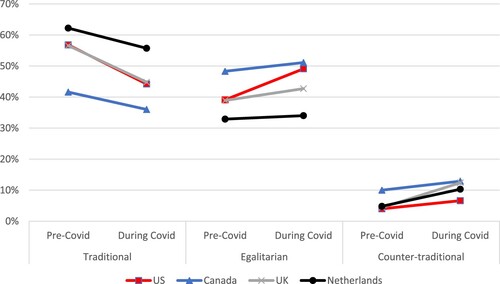

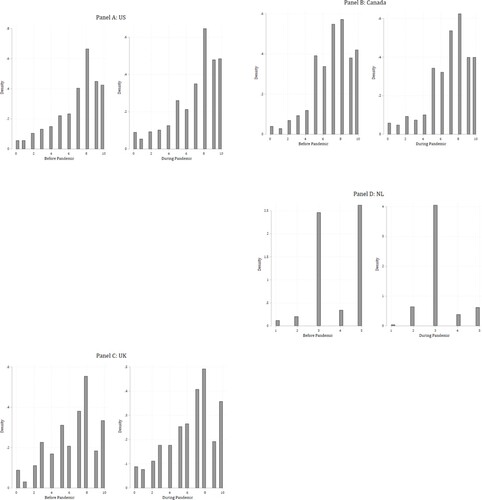

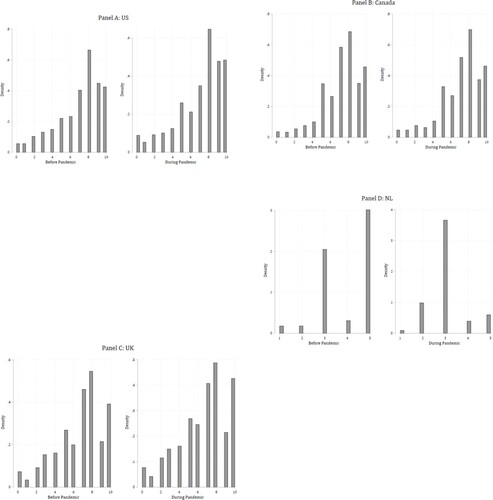

Summary statistics are presented in with changes in the division of domestic labour further illustrated in and . Prior to the pandemic, fathers performed the greatest shares of housework and childcare in Canada, followed by the US and UK. Fathers’ shares of both housework and childcare increased in all four countries while the proportion of traditional couples where mothers perform the majority of domestic labour decreased in all countries early in the pandemic. Increases in domestic labour were more pronounced in the US – particularly for housework tasks. Specifically, as shown in , the proportion of ‘traditional’ families where mothers do most of the housework decreased from 69% pre-pandemic to 53% during the pandemic in the US (51% to 48% in Canada, 67% to 61% in the UK, and 65% to 59% in the Netherlands), whereas the proportion of ‘egalitarian’ couples increased from 24% to 38% in the US (33% to 34% in Canada, 20% to 22% in the UK, and 30% to 34% in the Netherlands). There was less change in ‘counter-traditional’ arrangements (from 7% to 8% in the US, 16% to 18% in Canada, 14% to 16% in the UK, and 5% to 7% in the Netherlands). Similar patterns are found for childcare as shown in . Specifically, the proportion of couples where mothers did most of the childcare decreased in all countries (from 57% to 44% in the US, 42% to 36% in Canada, 57% to 45% in the UK, and 62% to 56% in the Netherlands), whereas there was a slight increase in egalitarian arrangements (from 39% to 49% in the US, 48% to 51% in Canada, 39% to 43% in the UK, and 33% to 34% in the Netherlands). Results also show more substantial increases in counter-traditional childcare arrangements in the UK (from 4% to 12%) and the Netherlands (from 5% to 10%), whereas changes were smaller in the US (from 4% to 7%) and Canada (from 10% to 12%). However, it is important to note that mothers continue to perform a larger share of housework and childcare than fathers in all four countries, as illustrated by the mean values in all being less than 3.

Table 1. Summary statistics.

Multivariate models were used to further test whether changes in the division of domestic labour varied by country. Results are presented in . Consistent with the descriptive results, shows that the increase in fathers’ shares of housework is more pronounced in the US than in the other three countries. Additional analyses show that increases in fathers’ shares of housework are greater in Canada and the UK compared to the Netherlands. However, we find no variation by country in changes in the division of childcare. Overall, we find that fathers’ shares of housework and childcare increased in the early pandemic in all countries, supporting H1a. We also find partial support for H1b, since increases in fathers’ shares of housework are most pronounced in the US and least pronounced in the Netherlands.Footnote7

Table 2. OLS regression model predicting changes in division of domestic labour during pandemic.

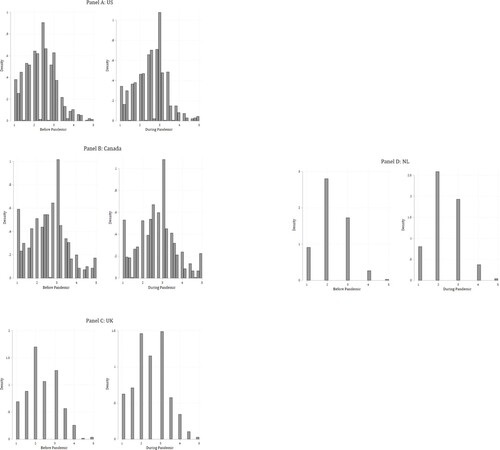

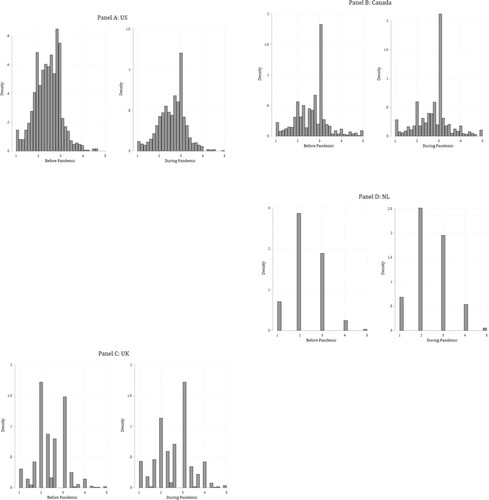

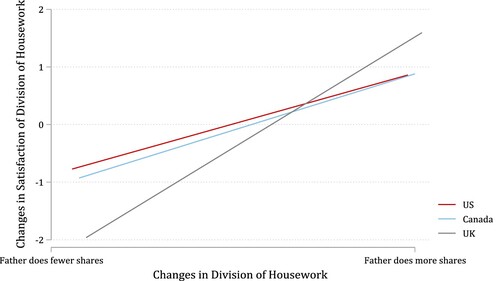

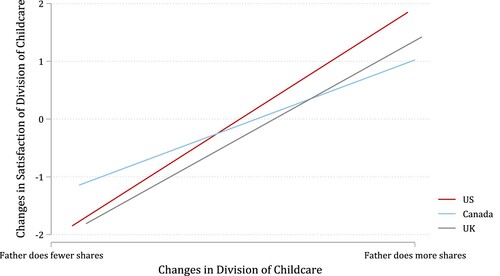

Finally, we analysed whether changes in the division of domestic labour are associated with changes in parents’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour. Initial bivariate analyses provided some support for H2a, showing that shifts to a more egalitarian division of domestic labour was associated with increased satisfaction in the division of domestic labour in most countries (no relationship in the Netherlands), whereas shifts toward a more traditional division of domestic labour were associated with decreased satisfaction in the division of domestic labour (see in the appendix). For a more robust test of our hypotheses, we present results from multivariate models in and . Consistent with H2a, we find fathers’ increased participation in housework is associated with greater satisfaction with the division of housework in the US, Canada, and UK (Model 1 of and ) and fathers’ increased participation in childcare is associated with greater satisfaction with the division of childcare (Model 3 of and ). Further analyses show that these associations are driven mostly by mothers’ satisfaction with the division of childcare, whereas no significant relationship was found for fathers’ satisfaction (results available upon request). Evidence surrounding H2b is a bit more mixed. In contrast to H2b, the association between increases in fathers’ shares of housework and changes in parents’ satisfaction with the division of housework is strongest in the UK (see Model 2 of and ).Footnote8 Yet, in support of H2b, as shown in , there is a negative association with changes in the division of housework and satisfaction with the division of housework in the Netherlands, and no association between changes in the division of childcare and satisfaction (or lack of conflict) with the division of childcare.Footnote9

Figure 3. Parents’ satisfication about division of housework by changes in division of housework and country.

Figure 4. Parents’ satisfication about division of childcare by changes in division of childcare and country.

Table 3. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic.

Table 4. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour in the Netherlands during pandemic.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic abruptly shifted how parents across the world worked, cared for children, and divided paid and unpaid labour in the spring of 2020. Families spent much more time together at home with social activities shut down and many parents were either pushed to work from home or forced out of work temporarily. Children were displaced from their schools and daycares, and other forms of nonparental childcare became largely unavailable. This shock to families’ routines meant more childcare to perform at home, meals to cook, and messes to clean. These changes created the opportunity for family responsibilities to be renegotiated, with gender divisions potentially moving toward egalitarianism. Fathers had greater availability to do unpaid domestic work due to lockdowns. Workload readjustments among parents during this social upheaval also meant that satisfaction with the division of labour within relationships might shift. Although there has been much concern that the pandemic may increase gender inequality (e.g., Landivar et al., Citation2020), our study showed that in all countries, fathers increased their share of housework and childcare during the early days of the pandemic, thus moving toward egalitarianism and echoing research from many scholars across the globe (Margaria, Citation2021). Consistent with previous research focused on the divisions of labour and the quality of relationships, these shifts were associated with mothers feeling more satisfied with this new division of domestic labour, although we do not find the same for fathers (Carlson et al., Citation2018; Schieman et al., Citation2018). It is possible that fathers struggled more with balancing working from home and increased involvement in domestic labour, particularly given breadwinning expectations (Aumann et al., Citation2011). In contrast, because mothers are more likely to already shoulder more domestic responsibilities, greater sharing of these tasks was more appreciated.

Our study also found variations in how gender renegotiations within families occurred across work-care regimes. We expected that adult-worker countries characterized by long working hours would show a larger shift toward equality as well as a stronger shift in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour. Indeed, the US witnessed the biggest shift in fathers’ shares of housework and childcare, perhaps because the overwork of American fathers in early 2020 shifted more dramatically and placed them in a better position to share domestic tasks. Canadian fathers already did more unpaid work than American fathers, perhaps due to shorter work hours than their American counterparts (OECD, Citation2019; Shafer et al., Citation2021). But, as expected, we found a bigger shift toward fathers doing more in Canada compared to the Netherlands (a one-and-a-half earner regime).

We also found some differences between our one-and-a-half earner countries. Increases in fathers’ shares of housework were more pronounced in the UK than in the Netherlands. Moreover, the associations between fathers’ increased shares of domestic labour and mothers’ satisfaction with these divisions were similar (or more pronounced, in the case of housework) in the UK as in the US and Canada. We expected the associations between fathers’ shares of domestic labour and parents’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour to be more pronounced in adult-worker countries. However, the long work hour culture for men and the strong belief that fathers should be the primary breadwinners in the UK (ISSP, Citation2012), may have led fathers’ modest increased contributions to be more appreciated, particularly by part-time working mothers (given that the UK sample is comprised of dual-earner households). In contrast, we do not observe any association between fathers’ shares of childcare and parents’ satisfaction with the division of childcare in the Netherlands, and a negative association between fathers’ shares of housework and parents’ satisfaction with the division of housework, which coincided with smaller increases in fathers’ shares of housework in this country. Even before the pandemic, there were fewer structural barriers to father involvement in the Netherlands as compared to the US, Canada, and the UK, as well as more support for parents both working part-time in the Netherlands than in the other three countries (ISSP, Citation2012). Therefore, greater sharing amongst mothers and fathers during times of need such as a pandemic may have been more expected in the Netherlands than in the other countries. As such, fathers’ greater shares of domestic labour during the pandemic may not have led to greater satisfaction with the division of domestic labour in the Netherlands to the same extent as we see in the other countries where increases in fathers’ participation in childcare and housework may have been more unexpected and thus more appreciated. However, we interpret the Dutch results with some caution. While surveys from the US, UK, and Canada asked respondents about their satisfaction with the division of domestic labour, respondents from the Netherlands were asked about conflict surrounding divisions of domestic labour. Satisfaction and conflict are closely related, yet distinct aspects of relationship quality (Carlson et al., Citation2018; Suitor, Citation1991). Given the large amount of domestic labour that was thrust back upon families during the early pandemic, couples may have been increasingly satisfied with men’s larger shares of housework and childcare while they simultaneously struggled to organize and arrange their divisions of labour (i.e., argued more frequently) given the substantial increase in new domestic responsibilities.

The study has several limitations. First, we observe a brief period during the lockdowns in spring 2020. While this allows us to uniquely capture how abrupt work-family shocks may have facilitated a small movement toward egalitarianism and increased satisfaction with divisions of domestic labour, the ability to assess the ‘staying power’ of such changes is truncated by the short window. Future research should examine whether changes in the division of domestic work and relationship quality persist. We also note that there are some notable differences across the four surveys used in this study, which prevented a full analysis with all four countries for all outcomes. Data from the US, Canada, and UK also come from non-probability samples; future studies should use nationally representative data to further explore the associations between parents’ divisions of domestic labour and satisfaction with the division of labour. The UK sample is also unique, including only dual-earner couples. Supplementary analyses suggest that the main results are largely consistent for both dual-earner couples and couples where fathers are the sole earner (Tables A5–A8), but future research should further explore the impact of work status on parents’ divisions of domestic labour and perceptions of these divisions of labour.Footnote10

Overall, the analysis underscores how displacement from workplaces, schools, and social life in spring 2020 recast the gendered division of domestic labour. Fathers increased their share of housework and childcare during this time in all four countries, and mothers became more satisfied with the division of domestic labour during this unique ‘coming together’ period. It is impressive that mothers’ satisfaction with the division of domestic labour could be improved quickly upon more equal sharing – suggesting strong benefits for policies and workplace practices (e.g., flexible working) that enable and encourage fathers’ involvement in domestic work. Such policies and practices are critical when we consider the disproportionate stressors that mothers face both prior to, and during, the pandemic (Banks & Xu, Citation2020; Ruppanner et al., Citation2019). Though there were some similarities in the changes in divisions of domestic labour observed across countries, these changes and their associations with parents’ satisfaction were particularly pronounced in work-care regimes where full-time work is prioritized, as these regimes likely experienced larger shifts in fathers’ awareness and opportunity to perform domestic labour with work conditions changing due to lockdowns and working from home. The study contributes to the existing literature by providing evidence of how the intersection of policy, gender and work cultures not only shaped how couples utilize sudden ‘opportunities’ as those provided by the pandemic, but also how these changes were experienced by parents. Such comparative work promises to be generative for understanding the pandemic’s imprint on gender relations far into the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Detailed information about the US survey is available online (Carlson & Petts, Citation2022).

2 The UK sample included only parents in dual-earner couples, and the Netherlands sample required that at least one partner was employed.

3 Respondents reported on 5 housework and 8–9 childcare tasks (depending on child age) in the US, 6 housework and 8 childcare tasks in Canada, and 2 housework and 3 childcare tasks in the UK. Only routine tasks are included.

4 Response options 2 and 3, as well as options 5 and 6, were combined (i.e., doing ‘a lot more’ and ‘more’) to create a five-point range that is consistent with the US, Canada, and UK data (indicating whether respondent/partner does ‘more’).

5 Scale scores between 2.6 and 3.4 are used to approximate a relatively equal division of labour, as they equate to fathers doing between 40 and 60% of the housework and childcare (using a scale ranging from 1–5 where 3 equates to fathers doing 50% of domestic labour). Similar cutoff points have been used in previous research (e.g., Carlson et al., Citation2021b).

6 Bivariate analyses examining the association between division of domestic labour and satisfaction with the division of domestic labour can be found in the appendix ().

7 Results using the categorical measures of divisions of domestic labour are largely consistent with those presented in (see in the appendix).

8 This appears to be most pronounced in couples with a traditional division of labour pre-pandemic (see in the appendix).

9 Results are similar when categorical measures of change in the division of domestic labour are used (see Tables A3 and A4 in the appendix).

10 The exception is that the association between increases in fathers’ shares of childcare and satisfaction with the division of childcare is weaker in the UK than in the US for couples where only the father is employed. However, given the small number of father sole earner families in the UK sample (N = 45), we avoid making any strong conclusions about this finding.

References

- Aboim, S. (2010). Gender cultures and the division of labour in contemporary Europe: A cross-national perspective. The Sociological Review, 58(2), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01899.x

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

- Altintas, E., & Sullivan, O. (2016). Fifty years of change updated: Cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research, 35, 455–470. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.16

- Aumann, K., Galinsky, E., & Matos, K. (2011). The new male mystique. Families and Work Institute. https://www.familiesandwork.org/research/2011/the-new-male-mystique.

- Banks, J., & Xu, X. (2020). The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Fiscal Studies, 41(3), 685–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12239

- Barstad, A. (2014). Equality is bliss? Relationship quality and the gender division of household labor. Journal of Family Issues, 35(7), 972–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522246

- Bennett, J. (2021). Fewer jobs have been lost in the EU than in the U.S. During the COVID-19 downturn. Pew Research Center.

- Berik, G., & Kongar, E. (2013). Time allocation of married mothers and fathers in hard times: The 2007-09 US recession. Feminist Economics, 19(3), 208–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.798425

- Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos120

- Blom, N., Kraaykamp, G., & Verbakel, E. (2017). Couples’ division of employment and household chores and relationship satisfaction: A test of the specialization and equity hypotheses. European Sociological Review, 33(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw057

- Brynjolksson, E., Horton, J. J., Ozimek, A., Rock, D., Sharma, G., & TuYe, H. (2020). COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US Data. NBER working paper 72344. http://www.nber.org/papers/w27344.

- Carlson, D. L., Hanson, S., & Fitzroy, A. (2016). The division of child care, sexual intimacy, and relationship quality in couples. Gender & Society, 30(3), 442–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243215626709

- Carlson, D. L., Miller, A. J., & Rudd, S. (2020). Division of housework, communication, and couples’ relationship satisfaction. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120924805

- Carlson, D. L., Miller, A. J., & Sassler, S. (2018). Stalled for whom? Change in the division of particular housework tasks and their consequences for middle- to low-income couples. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118765867

- Carlson, D. L., & Petts, R. J. (2022). Study on U.S. parents’ divisions of labor during COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.3886/E166961V5.

- Carlson, D.L., Petts, R.J., & Pepin, J.R. (2021a). Flexplace work and partnered fathers’ time in housework and childcare. Men and Masculinities, 24(4), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X211014929.

- Carlson, D. L., Petts, R. J., & Pepin, J. R. (2021b). Changes in US parents’ domestic labor during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociological Inquiry, 92(3), 1217–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12459.

- Chung, H. (2021). Shared care, father’s involvement in care and family well-being outcomes: A literature review. Report for the government equalities office. UK Cabinet Office.

- Chung, H., Birkett, H., Forbes, S., & Seo, H. (2021). COVID-19, flexible working, and implications for gender equality in the United Kingdom. Gender & Society, 35(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211001304

- Chung, H., & Van der Horst, M. (2018). Women’s employment patterns after childbirth and the perceived access to and use of flexitime and teleworking. Human Relations, 71(1), 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717713828

- Collins, C. (2019). Making motherhood work: How women manage careers and caregiving. Princeton University Press.

- Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities. University of California Press.

- Craig, L., & Churchill, B. (2021). Dual-earner parent couples’ work and care during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S1), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12497

- Crompton, R. (1999). Restructuring gender relations and employment: The decline of the male breadwinner. Oxford University Press.

- Dermott, E. (2008). Intimate fatherhood: A sociological analysis. Routledge.

- Dermott, E., & Miller, T. (2015). More than the sum of its parts? Contemporary fatherhood policy, practice and discourse. Families, Relationships and Societies, 4(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674315X14212269138324

- Doucet, A., & Merla, L. (2007). Stay-at-home fathering: A strategy for balancing work and home in Canadian and Belgian families. Community, Work & Family, 10(4), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701575101

- England, P. (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender & Society, 24(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475

- Eurofound. (2020). Living, working and COVID-19, COVID-19 series. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x

- Gonalons-Pons, P., & Gangl, M. (2021). Marriage and masculinity: Male-breadwinner culture, unemployment, and separation risk in 29 countries. American Sociological Review, 86(3), 465–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224211012442

- Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. K. (2002). Building the dual earner/dual carer society: Policy developments in Europe (Working paper no. 82).

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global pandemic database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

- Hook, J. L. (2006). Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965-2003. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 639–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100406

- Hu, Y., & Yucel, D. (2018). What fairness? Gendered division of housework and family life satisfaction across 30 countries. European Sociological Review, 34(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx085

- International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). (2012). Family and changing gender roles IV. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12661.

- Koslowski, A., Blum, S., Dobrotić, I., Kaufman, G., & Moss, P. (2021). International review of leave policies and related research 2021. https://www.leavenetwork.org/annual-review-reports/review-2021/. https://doi.org/10.18445/20210817-144100-0.

- Lamb, M. E. (2010). The role of the father in child development (5th ed.). Wiley.

- Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., Scarborough, W. J., & Collins, C. (2020). Early signs indicate that COVID-19 is exacerbating gender inequality in the labor force. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120947997.

- Lavner, J. A. (2017). Relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples: Review, methodological critique, and research agenda. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 21(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1142348

- Levay, K. E., Freese, J., & Druckman, J. N. (2016). The demographic and political composition of mechanical Turk samples. SAGE Open, 6(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016636433

- Lewis, J., & Giullari, S. (2005). The adult worker model family, gender equality and care: The search for new policy principles and the possibilities and problems of a capabilities approach. Economy and Society, 34(1), 76–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308514042000329342

- Marsiglio, W. & Roy, K. (2012). Nurturing dads: Social initiatives for contemporary fatherhood. New York: Russell Sage.

- Margaria, A. (2021). Fathers, childcare and COVID-19. Feminist Legal Studies, 29(1), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-021-09454-6

- Milkie, M. A., Bianchi, S. M., Mattingly, M. J., & Robinson, J. P. (2002). Gendered division of childrearing: Ideals, realities, and the relationship to parental well-being. Sex Roles, 47(1/2), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020627602889

- Milkie, M. A., Nomaguchi, K., & Schieman, S. (2019). Time deficits with children: The link to parents’ mental and physical health. Society and Mental Health, 9(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318767488

- Nieuwenhuis, R., & Van Lancker, W. (Eds.) (2020). The palgrave handbook of family policy. Palgrave MacMillan.

- OECD. (2019). Average annual hours actually worked per worker. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode = ANHRS.

- OECD. (2021). Time spent in paid and unpaid work, by sex. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid = 54757.

- Offer, S., & Kaplan, D. (2021). The “new father” between ideals and practices: New masculinity ideology, gender role attitudes, and fathers’ involvement in childcare. Social Problems, 68(4), 986–1009. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab015

- Oian, Y., & Fuller, S. (2020). COVID-19 and the gender employment gap among parents of young children. Canadian Public Policy, 46(S2), S89–S101. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2020-077

- Palley, E., & Shdaimah, C. (2014). In our hands: The struggle for U.S. Child care policy. NYU Press.

- Petts, R. J., Carlson, D. L., & Pepin, J. R. (2021). A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents' employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S2), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12614

- Rao, A. H. (2020). Crunch time: How married couples confront unemployment. University of California Press.

- Ruppanner, L., Perales, F., & Baxter, J. (2019). Harried and unhealthy? Parenthood, time pressure, and mental health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(2), 308–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12531

- Rush, M. (2015). Between two worlds of father politics: USA or Sweden? Manchester University Press.

- Scarborough, W. J., Sin, R., & Risman, B. (2019). Attitudes and the stalled gender revolution: Egalitarianism, traditionalism, and ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gender & Society, 33(2), 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243218809604

- Schieman, S., Ruppanner, L., & Milkie, M. A. (2018). Who helps with homework? Parenting inequality and relationship quality among employed mothers and fathers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9545-4

- Schober, P. S. (2012). Paternal child care and relationship quality: A longitudinal analysis of reciprocal associations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(2), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00955.x

- Seward, R. R., & Rush, M. (2016). Changing fatherhood and fathering across cultures toward convergence in work-family balance: Divergent process or stalemate? In I. Crespi, & E. Ruspini (Eds.), Balancing work and family in a changing society (pp. 13–31). Palgrave McMillan.

- Shafer, K., Petts, R. J., & Scheibling, C. (2021). Variation in masculinities and fathering behaviors: A cross-national comparison of the United States and Canada. Sex Roles, 84(7-8), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01177-3

- Shafer, K., Scheibling, C., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). The division of domestic labor before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Stagnation versus shifts in fathers’ contributions. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 57(4), 523–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12315

- Statistics Canada. (2018). Who works part time and why? https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-222-x/71-222-x2018002-eng.htm.

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Canadian perspectives survey series 1: COVID-19 and working from home, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200417/dq200417a-eng.htm.

- Suitor, J. J. (1991). Marital quality and satisfaction with the division of household labor across the family life cycle. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(1), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/353146

- Thébaud, S. (2010). Masculinity, bargaining, and breadwinning: Understanding men’s housework in the cultural context of paid work. Gender & Society, 24(3), 330–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210369105

- US Department of Labor. (2020). Full-time/part-time employment. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/latest-annual-data/full-and-part-time-employment.

- van den Brakel, M., Portegijs, W., & Hermans, B. (2020). Emancipatiemonitor 2020. Accessed via https://digitaal.scp.nl/emancipatiemonitor2020/.

- Waddell, N., Overall, N. C., Chang, V. T., & Hammond, M. D. (2021). Gendered division of labor during a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown: Implications for relationship problems and satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(6), 1759–1781. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407521996476

- Wilkie, J. R., Ferree, M. M., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1998). Gender and marital satisfaction in two-earner couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.2307/353530

- Williams, J. C. (1999). Unbending gender: Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. Oxford University Press.

- Wishart, R., Dunatchik, A., Speight, S., & Mayer, M. (2019). Changing patterns in parental time use in the UK. Natcen.

- Yerkes, M. A., André, S., Beckers, D. G. J., Besamusca, J., Kruyen, P. M., Remery, C., van der Zwan, R., & Geurts, S. A. E. (2020). Intelligent’ lockdown, intelligent effects? Results from a survey on gender (in)equality in paid work, the division of childcare and household work, and quality of life among parents in The Netherlands during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0242249. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id = 10.1371/journal.pone.0242249.

- Yerkes, M. A., & Hewitt, B. (2019). Part-time work strategies of working parents in The Netherlands and Australia. In H. Nicolaisen, H. C. Kavli, & R. S. Jensen (Eds.), Dualisation of part-time work: The development of labour market insiders and outsiders (pp. 265–288). Policy Press.

- Yerkes, M. A., & Javornik, J. (2019). Creating capabilities: Childcare policies in comparative perspectives. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(4), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718808421

Appendix

Table A1. Bivariate associations between changes in division of domestic labour and changes in satisfaction with the division of labour (N = 3307).

Table A2. Multinomial logistic regression model predicting changes in division of domestic labour during pandemic.

Table A3. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic.

Table A4. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic in the Netherlands.

Table A5. Summary statistics for dual earner couples and couples where only father is employed.

Table A6. OLS regression model predicting changes in division of domestic labour during pandemic separately for dual earner couples and couples where only father is employed.

Table A7. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic separately for dual earner couples and couples where only father is employed.

Table A8. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour in the netherlands during pandemic separately for dual earner couples (N = 421) and couples where only father is employed (N = 93).

Table A9. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic, by division of labour pre-pandemic.

Table A10. Predicting changes in satisfaction with the division of domestic labour during pandemic in the netherlands, by division of labour pre-pandemic.