ABSTRACT

This study explores intergenerational co-residence, explicitly focusing on the decision-making factors of older adults and their adult children. While previous research has touched on this topic, only a few studies have truly evaluated the factors driving both generations’ willingness to embrace this living arrangement. This study systematically reviews the factors influencing older and younger adults’ willingness to live in intergenerational households. Systematic searches were conducted through five databases: CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus; all studies until September 2022. Of the 467 articles initially identified, 17 articles were retained for data extraction. Extracted data were divided into two groups: older people’s and adult children's perspectives. Data extraction revealed six factors influencing older adults’ decision to live with their children, encompassing financial circumstances, health conditions, kinship systems, marital status, level of education, and number of family members. Similarly, these factors are relevant for adult children, except for health conditions. The interconnection between these factors and their dynamics is contingent upon the specific context of each region’s population.

Introduction

The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations (Citation2020) reported that there are three standard living arrangements for older adults: living alone, living with children, and living in institutions. Other arrangements also exist, including living with extended family, skip generation, and non-relative persons. However, most older people prefer to live with their adult children, even in the more developed countries (Ruggles, Citation2007). Co-residence between the two generations mainly occurs during the later life of older people (Reher & Requena, Citation2018). Older people tend to protect their autonomy by living alone to have the freedom to manage their daily activities (Meng et al., Citation2017). However, their health conditions may require them to live with a caregiver, more often their adult child (Gonzales, Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation1995; Reher & Requena, Citation2018).

In Asian cultures, there is a strong emphasis on filial piety, where adult children are obligated to provide a place to live with their parents (Chen & Jordan, Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2022; Chu et al., Citation2011; Kim et al., Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2014). Moreover, some countries have limitations on social protection programmes due to government regulations that make co-residence the best solution for giving intergenerational support. Living together allows adult children to support their parents, and older people can support their children with their daily responsibilities (Beard & Kunharibowo, Citation2001; Casares & White, Citation2018; Chen & Jordan, Citation2019; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Citation2020; Ward & Spitze, Citation2007; Zhang et al., Citation2014).

This mutual support between older people and their adult children can impact both generations positively and negatively. Co-residence can help both generations to assist each other (Chen & Lewis, Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2018; Meng et al., Citation2017; Yasuda et al., Citation2011), which helps older people maintain their psychological well-being (Kim et al., Citation2017; Setiyani et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2014) and life satisfaction (Chen et al., Citation2021; Chen & Jordan, Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2018). Conversely, co-residence can also negatively impact the parent–child relationships. Too much support from adult children can reduce the autonomy of older people and lower their psychological well-being (Silverstein & Bengtson, Citation1994). Co-residence may also influence the quality of the relationship between parents and their adult children. [edited for anonymous review] shows that the detrimental dynamics between older people and their adult children exert more influence on their psychological well-being compared to the positive aspects.

Furthermore, a review by Zhao (Citation2023) found that the welfare management policies for older people play an important role in influencing the living arrangements of older people in China. Similarly, intergenerational co-residence in the United States has been shown to be influenced by shifts in social welfare policies and ethnic demographics (Keene & Batson, Citation2010). Along with this result, a review of intergenerational co-residence in North America also highlighted the importance of demographic, economic, and ethnic identities in influencing intergenerational co-residence (Mazurik et al., Citation2020). Roy et al. (Citation2018) conducted a systematic review highlighting the role of older people’s health conditions as a determinant of intergenerational co-residence in countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, and various European nations. However, health deterioration prevents older people in Indonesia from living with their children (Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011).

Hence, we assume that intergenerational co-residence is a complex issue that can be influenced by various factors, including demographic, economic, social, and cultural circumstances. A factor that significantly impacts intergenerational co-residence in one geographical area may not necessarily yield the same impact in another region. Also, we suspect that ageing parents and adult children will have different considerations regarding this living arrangement. Ward and Spitze (Citation1992) reviewed many studies about co-residence by parents and adult children and suggested further research on the motivations that influence the decision of older adults and their children to live in intergenerational households was required. Thus, the primary objective of this study is to find the determinant factors behind the participation of older people and adult children in intergenerational co-residence. This will be achieved through an extraction of empirical studies with a systematic review approach.

Design and methods

This study uses a systematic review framework to identify and retrieve the evidence on factors influencing the engagement of older people and adult children in intergenerational co-residence. The authors screened and ensured that all the studies in this systematic review followed the inclusion criteria. All the processes of this systematic review were conducted through Covidence. An expert librarian from The University of Queensland, Australia, also reviewed the search strategy in this study. In addition, we registered this systematic review with PROSPERO (CRD42022361694).

Ethics approval

This is a systematic review; as such, it involves secondary data analysis of published material and does not require ethics committee approval.

Search strategy and study selection

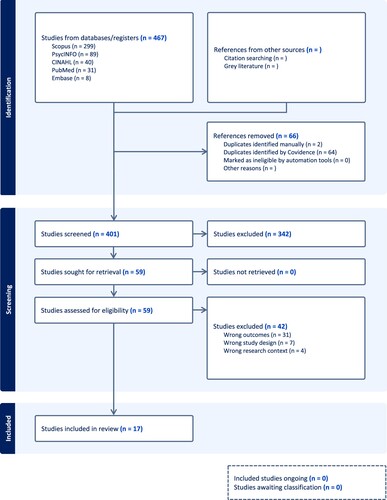

This systematic review had three steps in searching and selecting studies. The first was a comprehensive search of several databases to ensure that this review located studies from multiple countries and research fields related to intergenerational co-residence between older people and adult children. The databases included CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus. We searched all studies until September 2022.

Search terms included a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) indicative of (1) intergenerational relations, (2) co-residence, (3) parent-adult child co-residence, (4) adult children, (5) elderly, and (6) well-being. Studies were included in this systematic review if they met the following criteria: (1) the study's primary focus was the intergenerational co-residence dynamics between older people and their adult children; (2) original empirical studies with research methods explicitly reported; (3) all study designs, except systematic, scoping, and literature reviews; (4) the full-text article was accessible. In total, we retrieved 467 articles from the five databases.

Next, titles and abstracts were screened, and duplicates were removed. A further 342 articles were removed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, including studies focused on young child populations. Due to the aim of this study, we excluded research involving older adults facing terminal illnesses or psychological disorders like depression and anxiety. The existence of an illness in an aged parent tends to heighten the social expectations on adult children to provide more intensive care. Consequently, intergenerational co-residence is likely to be influenced by the parents’ health conditions rather than the voluntary choice of adult children to share a residence. Also, we excluded studies about ageing stigma, neurocognitive problems, and older people who lived in the institutions. We omitted studies that included adult–child participants with developmental issues. These exclusion criteria aimed to ensure that the included studies were focused on a representative sample of older people and adult children. That is, engagement in intergenerational co-residence was not due to the need to assist another generation's disability.

The full-text review consisted of 42 articles. This review defined intergenerational co-residence as between ageing parents and their adult children who were otherwise old enough to live independently. We excluded all publications that were book chapters and dissertations and only included peer-reviewed articles. We give preference to research that has undergone a rigorous peer review process to ensure its quality. Hence, our priority is to utilise empirical research published in academic journals over other formats. Two authors, LH and TR, conducted review processes independently, with the second author (PN) resolving any disagreements. In the end, 17 studies were retained for data extraction. outlines these steps.

Extraction and data analysis

A data extraction form was created through Covidence with the following components: research location, research objective, methods, participants, indicators of intergenerational co-residence for older people, and indicators of intergenerational co-residence for adult children. In addition, we also completed a quality assessment for every study we reviewed with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 (Hong et al., Citation2018). For example, the clarity of the research question, the data collection process following the research question, the appropriateness of the study design to answer the research question, and whether the interpretation of the results was sufficiently substantiated by the data. This data extraction process was led by the first author (LH) and checked by the third author (TR). Disagreements were resolved by a second author (PN).

Findings

This study aimed to identify the factors influencing older people's and adult children's engagement in intergenerational co-residence. From the 17 articles initially identified for this systematic review, we found that only eight provided data about the factors that motivated adult children to participate in intergenerational co-residence; 16 of these articles evaluated the willingness of older people to live with their adult children. Most of the studies included in this systematic review focused on community-based populations in rural and urban areas, with one study focused solely on the adult child population in rural areas (VanWey & Cebulko, Citation2007). summarises the 17 articles included in this systematic review.

Table 1. The studies summary.

Intergenerational co-residence arrangements can stem from diverse determinants, including cultural values that foster the expectation of ageing parents to live with their adult children. Due to this variation, our data interpretation involved a thematic analysis based on the regions of each study’s population to see the dynamic of the factors influencing both generations’ decision to engage in intergenerational co-residence. We divided the regions into four areas: Americas, Europe, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. The determinants factors of intergenerational co-residence based on regions can be seen in .

Table 2. Intergenerational co-residence based on regions.

Financial circumstances

shows that financial circumstances are seen as one of the factors motivating intergenerational co-residence in every region. Studies by Gerber et al. (Citation2019) and Gonzales (Citation2007) in the United States found that financial stability can motivate older people to live with their adult children, as well as studies in East Asia (Johar et al., Citation2015; Takagi et al., Citation2007; Won & Lee, Citation1999). Conversely, Smits et al. (Citation2010) revealed that financial strain has become the main determinant for older people living with their adult children in the Netherlands. Lee et al. (Citation1995) also showed a similar result in Taiwan. Parents’ financial stability can be measured through job ownership (Smits et al., Citation2010), wealth (Johar et al., Citation2015; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; VanWey & Cebulko, Citation2007), and home ownership (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Gonzales, Citation2007; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012). The stability of their financial situation can facilitate the parents in supporting their adult children, especially those children who lose their income resources (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Gerber et al., Citation2019; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Smits et al., Citation2010; Takagi et al., Citation2007).

Isengard and Szydlik (Citation2012) investigated intergenerational co-residence in 11 European countries and found that parents’ income had no significant effect on co-residence. However, home ownership can encourage ageing parents and adult children to live together. The size of the parental house appears to correlate positively with the likelihood of adult children residing there. This, combined with soaring housing prices, makes it challenging for the younger generation to attain home ownership. In urban areas, where housing tends to be smaller compared to rural areas, this discourages parents and adult children from living in the same house (Chen, Citation2019). In contrast, a study in Indonesia showed that homeownership did not affect intergenerational co-residence (Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011).

From the perspective of adult children, financial strain is the main factor in deciding to co-reside with their parents (Choi, Citation2003; Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Smits et al., Citation2010). However, no East Asian studies that have mentioned financial strain as the motive for adult children to participate in intergenerational co-residence could be found. Moreover, financially well-off children in Southeast Asia and Europe tend to live independently (Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Smits et al., Citation2010). However, adult children in Europe who are self-employed or receive ongoing disability benefits tend to engage in an intergenerational co-residence to share their household expenses with their parents (Smits et al., Citation2010). Similarly, the eldest sons in Japan receive financial help from their parents since older Japanese people endorse the primogenital family system, motivating the children to live with their parents (Johar et al., Citation2015).

Health condition

On the one hand, most studies in this systematic review found that health deterioration can be a determinant for leading older people to live with their adult children (Choi, Citation1995, Citation2003; Gonzales, Citation2007; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Johar et al., Citation2015; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation1995). On the other hand, their health conditions can also prevent them from living with their children due to their inability to exchange support (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Gonzales, Citation2007; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation1995). Poor health conditions can prevent older people from assisting their children and engaging in support exchange between generations. A study in the United States showed that ageing parents prefer living in an institution rather than intergenerational co-residence when their health impairment worsens (Choi, Citation2003). A similar situation was also found to exist in Indonesia, where Johar and Maruyama (Citation2011) revealed that ageing parents were more reluctant to be involved in intergenerational co-residence when their health condition decreased.

However, three studies in the Americas region showed that older people with low ADL/IADL scores were more likely to participate in intergenerational co-residence (Choi, Citation1995, Citation2003; Gonzales, Citation2007). Similarly, Isengard and Szydlik (Citation2012) found that in Europe, older people’s health impacted the decision for them to live with their adult. Likewise, three studies in East Asia (Chen, Citation2019; Johar et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation1995) and two in Southeast Asia (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Ken & Teerawichitchainan, Citation2015) revealed that health deterioration was one of the main factors that influenced ageing parents to live with their adult children.

No studies were found to directly attribute parents’ health conditions as the trigger for adult children to co-reside with their ageing parents. However, adult children seemed to realise that as their parents age, they become more vulnerable to health deterioration, prompting them to evaluate their ability to provide care. Typically, middle-aged children may feel more reluctant to care for their parents due to their parents’ physical limitations than younger adult children (Choi, Citation2003; Smits et al., Citation2010). Further, financially capable children often prefer to care for their parents by recruiting a professional caregiver (Choi, Citation2003).

Kinship systems

In East Asian countries, such as Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, there is a cultural value known as filial piety, which emphasizes the responsibility of adult children to care for their ageing parents (Johar et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation1995; Takagi et al., Citation2007; Won & Lee, Citation1999). This value develops expectations for older people to be taken care of by their children in later life, usually leading to the practice of intergenerational co-residence. Similarly, Gonzales (Citation2007) also found that filial responsibilities were important in determining older adults’ decision to cohabitate with their adult children in the United States. For example, this could occur if a parent's health worsens, leading adult children to feel more responsible for taking care of them as they get older. Additionally, Chen (Citation2019) revealed that parents who are used to living in multigenerational families usually choose to continue living with their family when they get older.

In some countries, filial piety is also associated with the gender of adult children, where sons are attributed to having greater filial responsibilities towards their parents. It can be seen from the studies in South Korea (Won & Lee, Citation1999), Japan (Takagi et al., Citation2007), and Vietnam (Teerawichitchainan et al., Citation2015), where parents choose to live with their sons rather than their daughters. However, research conducted in the Philippines indicated that the nature of the relationship between parents and children is more significant in determining their living arrangements than gender preferences associated with filial piety (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995). Parents tend to choose the children with whom they feel most comfortable, and this preference often leans towards daughters (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Teerawichitchainan et al., Citation2015). Conversely, a negative relationship quality between older people and their children can result in a sense of rejection in parents and make them less likely to be involved in intergenerational co-residence (Lee et al., Citation1995).

Furthermore, adult children across all regions also considered kinship systems in their decisions regarding living arrangements (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Lee et al., Citation1995; Smits et al., Citation2010; VanWey & Cebulko, Citation2007). This indicates that adult children recognize their obligation to care for their parents in later life. One factor that may influence this is the increasing age of parents and the decline in their health, which makes them increasingly reliant on assistance for their daily routines. A study by VanWey and Cebulko (Citation2007) showed that daughters in Brazil were concerned about their parent’s ability to handle housework, so they assisted their parents in completing daily household chores as their parents got older. Domingo and Asis (Citation1995) also mentioned the debt of gratitude as the motive of adult children to co-reside with their parents. These adult children see their parents’ old age as an opportunity to repay the care and support their parents provided in nurturing them.

Marital status

Ageing parents consider their marital status when deciding to participate in intergenerational co-residence. Widowed parents, in particular, are motivated to cohabitate with their children in all regions (Choi, Citation2003; Johar et al., Citation2015; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Ren & Treiman, Citation2015; Smits et al., Citation2010; Takagi et al., Citation2007; Won & Lee, Citation1999); while Smits et al. (Citation2010) discovered a positive correlation between parental divorce and intergenerational co-residence in the Netherlands. In contrast, divorced parents in the United States prefer to live independently even though they experience health deterioration (Choi, Citation2003). It is still to be determined why divorced parents are more inclined to live in institutions as their last resort to have better care for their physical limitations. Still, Choi (Citation2003) argued that institutions can provide more adequate care, which may not be available in a home setting.

Research suggests that widowed mothers with a lower level of education tend to live with their children when they get older (Smits et al., Citation2010; Takagi et al., Citation2007; Won & Lee, Citation1999). It is similar to widowed fathers who choose to live in intergenerational co-residence to receive daily assistance, especially in fulfilling the spouses’ roles that were absent after their wives passed away (Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011). In contrast, older people with spouses may prefer to live independently (Chen, Citation2019; Won & Lee, Citation1999). A study in China showed that living with their spouses resulted in better mental health for older people compared to their counterparts who lived in two-generation households (Ren & Treiman, Citation2015). Likewise, a study from the United States also showed that married parents were more likely to live independently than engage in intergenerational co-residence (Choi, Citation1995). However, in a sample of Mexican-Americans living in the United States, older adult couples were more likely to invite their children to live with them, as the children could provide better support for the parents, occasionally leading to the phenomenon of boomerang children (Gonzales, Citation2007). Boomerang children is a term to describe a phenomenon where adult children who have previously left their parental home for extended periods for various reasons return to live with their parents (Casares & White, Citation2018).

As for adult children, marital status significantly affects their decision to participate in intergenerational co-residence. Many studies in all regions found that married children tend to live independently with their spouses, while unmarried children, especially women, will choose to live with their parents (Choi, Citation2003; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Johar et al., Citation2015; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Smits et al., Citation2010; VanWey & Cebulko, Citation2007). They will try to maintain their independence until their parents experience a decline in health that requires them to need help in their daily activities (Choi, Citation2003). Meanwhile, divorced children usually return to their parent's houses to receive financial and psychological support. The presence of young children also leads adult children in Europe and Asia to seek intergenerational co-residence and the assistance of their older parents in parenting their young children (Smits et al., Citation2010).

Level of education

Another indicator that can protect older people from their vulnerability to engage in intergenerational co-residence is the level of education. Studies in America and East Asia indicate that older adults with higher education levels are less likely to live with their adult children (Chen, Citation2019; Choi, Citation1995; Gonzales, Citation2007). With a high level of education, older people are more likely to have the financial means to support themselves and their families independently (Chen, Citation2019; Gonzales, Citation2007). Likewise, a high level of education gives adult children greater opportunities to advance their careers and improve their quality of life, thereby enhancing their economic capabilities (Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012). A study in Brazil also showed that male children with low education tend to cohabitate with their parents more often than those with higher levels of education (VanWey & Cebulko, Citation2007). Hence, a high level of education enables both generations to sustain their independence in their living arrangements.

Number of family members

Some studies showed that the number of children in the family also influences older people’s opportunities to engage in intergenerational co-residence. Studies in the United States, Philippines, Indonesia, and Japan show that older adults who have many children will likely be living with one of their adult children (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Gonzales, Citation2007; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Takagi et al., Citation2007). However, Johar and Maruyama (Citation2011) also showed that older people with one child probably do not receive filial support unless the child has a high level of education or a sound economic foundation. A study conducted across 11 European countries showed that having more children in a family can prevent older people from living with them (Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012). This may be due to cramped living conditions or to adult children feeling less responsible for their parents due to the presence of their siblings (Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012; Smits et al., Citation2010).

Discussion

This systematic review has identified factors that influence the inclination of older people and their adult children to participate in intergenerational co-residence across various regions, including America, Europe, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Financial circumstances, health conditions, the kinship system, marital status, level of education, and the number of family members have emerged as considerations for ageing parents. Similarly, these factors were also considered by adult children, except for health conditions. Together, these factors interplay to determine the co-residence between ageing parents and adult children.

Broadly, across all regions, the decision of parents to reside with their adult children often arises from their desire to support their offspring. Conversely, adult children cohabiting with their parents usually need assistance fulfilling their needs. The factors influencing these two generations to live together are relatively similar. We found that financial circumstances play a significant role. Parents with stable economic conditions are more inclined to offer financial support to their children by cohabiting with them (Gerber et al., Citation2019; Gonzales, Citation2007; Johar et al., Citation2015; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011). This aligns with adult children who indeed require assistance from their parents to meet their economic needs (Choi, Citation2003; Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Smits et al., Citation2010).

Caring for ageing parents toward their adult children is an altruistic behaviour, wherein they express attention and support without anticipating reciprocity (Keene & Batson, Citation2010). While ageing parents technically no longer bear the responsibility to care for their adult children, globally, many still extend assistance, such as aiding with financial matters, parenting support, and managing household affairs to help the children pursue their careers (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Smits et al., Citation2010). This situation often leads ageing parents to resist the idea of cohabitating with their adult children as they age and their physical abilities decline (Choi, Citation2003; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011). They tend to feel incapable of providing support, which makes them fear becoming burdens rather than a support system for their children.

Indeed, we found that parents’ health conditions were one of the factors that influenced the decision of ageing parents and adult children in all regions to be involved in intergenerational co-residence. However, declining health can also lead parents to resist cohabitation because they feel unable to reciprocate the care provided by their adult children (Choi, Citation2003). Living together between ageing parents and their adult children undoubtedly facilitates the exchange of support (Zhao, Citation2023). However, this dynamic can leave parents with health deterioration feeling vulnerable, as they may perceive themselves as trouble for their children due to their inability to reciprocate the care provided by their children (Jennings et al., Citation2014). Indeed, adult children may want to show their filial piety by caring for their parents in their old age without expecting anything in return (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Zhao, Citation2023).

We presume that filial piety, traditionally considered a Confucian value prevalent in East Asia, extends beyond this region and is embraced by people in other countries as well, such as the United States (Gonzales, Citation2007) and the Philippines (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995), as evidenced by our systematic review findings. This value teaches children a sense of devotion towards their parents, particularly in their old age (Chen et al., Citation2022). It often manifests through actions such as inviting parents to live with them or the adult child becoming ‘a boomerang child’ to care for their parents. However, intergenerational co-residence is not the sole means of demonstrating devotion to parents. At times, parents cohabitating with their children can sometimes be lonely due to the low quality of the relationship between generations (Chen et al., Citation2021; Ha & Carr, Citation2005; Xu et al., Citation2019). Hence, various studies also highlight that parents consider the quality of their relationship with their children when choosing those who will cohabitate with them (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Lee et al., Citation1995; Seltzer et al., Citation2012).

Also, the implementation of filial piety may differ across regions. For example, in East Asia, parents put higher expectations on their sons to take care of them when they are old (Johar et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation1995; Takagi et al., Citation2007; Won & Lee, Citation1999). Meanwhile, older people in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand are more flexible in choosing their adult children to engage in intergenerational co-residence (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995; Johar & Maruyama, Citation2011; Ken & Teerawichitchainan, Citation2015). They prefer the adult child with whom they have the closest relationship, usually the youngest child (Domingo & Asis, Citation1995). If we compare between genders, parents typically choose to reside with their daughters rather than their sons (Ken & Teerawichitchainan, Citation2015; Won & Lee, Citation1999). They perceive daughters as more caring for fulfilling their daily needs, such as preparing meals, managing their medication, and doing household chores.

In this systematic review, we also observed that residential characteristics can influence parents’ decisions regarding intergenerational co-residence. In regions that are friendly toward older people, ageing parents often have lower expectations of co-residing with their adult children. They feel capable of living independently, thus reducing the need to rely on their adult children for support. However, such policies are not universally implemented across all regions. Only one study in this review was found to evaluate the impact of residential characteristics on intergenerational co-residence (Takagi et al., Citation2007).

In conducting this systematic review, we used five databases, including CINALH, Embase, PsycINFO, Scopus, and PubMed. These databases were chosen by our literature review, focusing on previous systematic reviews in Geropsychology, particularly those exploring intergenerational relationships between older people and adult children (Gualano et al., Citation2018; Wang & Lai, Citation2022; Zhong et al., Citation2020). To ensure the chosen databases met high-quality control standards, offered a wide range of scholarly articles, were regularly updated, and provided full-text access, consultations were conducted with expert librarians. Although we encountered numerous studies on intergenerational co-residence from diverse global regions, upon closer analysis, it became apparent that this review did not successfully identify studies discussing intergenerational co-residence in specific areas, such as Africa and South Asia.

Study limitation

While this systematic review has achieved its objectives, it is not without certain limitations. First, keywords related to intergenerational co-residence were utilized in literature searches. Despite employing terms established through Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), it remains possible that the six terms used might not encompass all research about intergenerational co-residence. Another limitation is that the review included no African and South Asian studies. Indeed, several African studies were initially identified in the search. However, these primarily focused on intergenerational relationships (Nauck, Citation2014) or living arrangements in a broader sense (Bongaarts & Zimmer, Citation2002; McKinnon et al., Citation2013; Ralston et al., Citation2019) rather than motivations. That is, these studies did not provide specific insights into intergenerational co-residence determinants, making it challenging to extract relevant factors for inclusion in this systematic review.

Conclusion

This systematic review reveals multiple factors shaping the inclination of older people and adult children to engage in intergenerational co-residence. Beyond the health conditions of ageing parents, considerations such as financial circumstances, kinship systems, marital status, level of education, and number of family members. Moreover, these factors often interact with one another, ultimately determining the outcome of whether to participate in intergenerational co-residence. For example, while health decline may prompt ageing parents to live with their adult children, this may not be the case for mothers, who may choose to live independently due to challenges in supporting their adult children as their health deterioration.

This review has highlighted the complexity and multidimensionality in the decision of ageing parents and adult children to be involved in intergenerational co-residence. The factors identified in this review are interconnected and their dynamics vary depending on the specific context of each population’s region. While similarities exist across regions, the willingness of both generations are also influenced by cultural values and local government policies. Parents’ expectations regarding intergenerational co-residence not only encompass considerations of filial piety but also intersect with government policies related to the care for older people. Therefore, future research should aim to assess these factors and specifically examine their impact on the conditions of both parents and children participating in intergenerational co-residence.

Declaration of contributions of authors

All authors have contributed substantially to designing, analysing, interpreting data and writing this publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beard, V. A., & Kunharibowo, Y. (2001). Living arrangements and support relationships among elderly Indonesians: Case studies from Java and Sumatra. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.202

- Bongaarts, J., & Zimmer, Z. (2002). Living arrangements of older adults in the developing world: An analysis of demographic and health survey household surveys. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), S145–S157. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.3.S145

- Casares, D. R., & White, C. C. (2018). The phenomenological experience of parents who live with a boomerang child. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 46(3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2018.1495133

- Chen, T. (2019). Living arrangement preferences and realities for elderly Chinese: Implications for subjective wellbeing. Ageing and Society, 39(8), 1557–1581. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000041

- Chen, J., & Jordan, L. P. (2019). Psychological well-being of coresiding elderly parents and adult children in China: Do father–child and mother–child relationships make a difference? Journal of Family Issues, 40(18), 2728–2750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19862845

- Chen, H. M., & Lewis, D. C. (2015). Chinese grandparents’ involvement in their adult children’s parenting practices in the United States. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-014-9321-7

- Chen, Y. J., Matsuoka, R. H., & Wang, H. C. (2022). Intergenerational coresidence living arrangements of young adults with their parents in Taiwan: The role of filial Piety. Journal of Urban Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2022.07.004

- Chen, F., Shen, K., & Ruan, H. (2021). The mixed blessing of living together or close by: Parent–child relationship quality and life satisfaction of older adults in China. Demographic Research, 44, 563–594. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2021.44.24

- Choi, N. G. (1995). Racial differences in the determinants of the coresidence of and contacts between elderly parents and their adult children. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 24(1-2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083V24N01_07

- Choi, N. G. (2003). Nonmarried aging parents’ and their adult children's characteristics associated with transitions into and out of intergenerational coresidence. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 40(3), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v40n03_03

- Chu, C. Y. C., Xie, Y, & Yu, R. R.. (2011). Coresidence with elderly parents: A comparative study of Southeast China and Taiwan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00793.x

- Domingo, L. J., & Asis, M. M. B. (1995). Living arrangements and the flow of support between generations in the Philippines. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 10(1-2), 21–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00972030

- Gerber, A., Heid, A. R., & Pruchno, R. (2019). Adult children living with aging parents: The association between income and parental affect. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 88(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415018758448

- Gonzales, A. M. (2007). Determinants of parent-child coresidence among older Mexican parents: The salience of cultural values. Sociological Perspectives, 50(4), 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2007.50.4.561

- Gualano, M. R., Voglino, G., Bert, F., Thomas, R., Camussi, E., & Siliquini, R. (2018). The impact of intergenerational programs on children and older adults: A review. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021700182X

- Ha, J. H., & Carr, D. (2005). The effect of parent-child geographic proximity on widowed parents’ psychological adjustment and social integration. Research on Aging, 27(5), 578–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505277977

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues Feijóo, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O'Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Isengard, B., & Szydlik, M. (2012). Living apart (or) together? Coresidence of elderly parents and their adult children in Europe. Research on Aging, 34(4), 449–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511428455

- Jennings, T., Perry, T. E., & Valeriani, J. (2014). In the best interest of the (adult) child: Ideas about kinship care of older adults. Journal of Family Social Work, 17(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2013.865289

- Johar, M., & Maruyama, S. (2011). Intergenerational cohabitation in modern Indonesia: Filial support and dependence. Health Economics, 20(S1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1708

- Johar, M., Maruyama, S., & Nakamura, S. (2015). Reciprocity in the formation of intergenerational coresidence. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9387-7

- Keene, J. R., & Batson, C. D. (2010). Under One roof: A review of research on intergenerational coresidence and multigenerational households in the United States. Sociology Compass, 4(8), 642–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00306.x

- Ken, Y., & Teerawichitchainan, B. (2015). Living arrangements and psychological well-being of the older adults after the economic transition in Vietnam. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 957–968. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv059

- Kim, J., Choi, Y., Choi, J. W., Nam, J. Y., & Park, E. C. (2017). Impact of family characteristics by marital status of cohabitating adult children on depression among Korean older adults. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(12), 2527–2536. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13066

- Lee, M.-L., Lin, H.-S., & Chang, M.-C. (1995). Living arrangements of the elderly in Taiwan: Qualitative evidence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 10(1-2), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00972031

- Liu, J., Guo, M., Mao, W., & Chi, I. (2018). Geographic distance and intergenerational relationships in Chinese migrant families. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 27(4), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1520167

- Mazurik, K., Knudson, S., & Tanaka, Y. (2020). Stuck in the nest? A review of the literature on coresidence in Canada and the United States. Marriage & Family Review, 56(6), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1728005

- McKinnon, B., Harper, S., & Moore, S. (2013). The relationship of living arrangements and depressive symptoms among older adults in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health, 13(1), Article 682. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-682

- Meng, D., Xu, G., He, L., Zhang, M., & Lin, D. (2017). What determines the preference for future living arrangements of middle-aged and older people in urban China? PLoS One, 12(7), Article e0180764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180764

- Nauck, B. (2014). Affection and conflict in intergenerational relationships of women in sixteen areas in Asia, Africa, Europe, and America. Comparative Population Studies, 39(4), 647–678. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2014-16

- Ralston, M., Schatz, E., Madhavan, S., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., & Collinson, M. A. (2019). Perceived quality of life and living arrangements among older rural South Africans: Do all households fare the same? Ageing and Society, 39(12), 2735–2755. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000831

- Reher, D., & Requena, M. (2018). Living alone in later life: A global perspective. Population and Development Review, 44(3), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12149

- Ren, Q., & Treiman, D. J. (2015). Living arrangements of the elderly in China and consequences for their emotional well-being. Chinese Sociological Review, 47(3), 255–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2015.1032162

- Roy, N., Dube, R., Despres, C., Freitas, A., & Legare, F. (2018). Choosing between staying at home or moving: A systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults. PLoS One, 13(1), e0189266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189266

- Ruggles, S. (2007). The decline of intergenerational coresidence in the United States, 1850 to 2000. American Sociological Review, 72(6), 964–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200606

- Seltzer, J. A., Lau, C. Q., & Bianchi, S. M. (2012). Doubling up when times are tough: A study of obligations to share a home in response to economic hardship. Social Science Research, 41(5), 1307–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.008

- Setiyani, R., Sumarwati, M., & Ramawati, D. (2019). Future living arrangement for aging parents and its associated factors. Jurnal Keperawatan Soedirman, 14(3), https://doi.org/10.20884/1.jks.2019.14.3.1196

- Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (1994). Does intergenerational social support influence the psychological well-being of older parents? The contingencies of declining health and widowhood. Social Science & Medicine, 38(7), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90427-8

- Smits, A., van Gaalen, R. I., & Mulder, C. H. (2010). Parent-child coresidence: Who moves in with whom and for whose needs? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(4), 1022–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00746.x

- Takagi, E., Silverstein, M., & Crimmins, E. (2007). Intergenerational coresidence of older adults in Japan: Conditions for cultural plasticity. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(5), S330–S339. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.5.S330

- Teerawichitchainan, B., Pothisiri, W., & Long, G. T. (2015). How do living arrangements and intergenerational support matter for psychological health of elderly parents? Evidence from Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. Social Science & Medicine, 136-137, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.019

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. D. (2020). World population ageing 2020 highlights: Living arrangements of older persons (ST/ESA/SER.A/451). U. N. Publication. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/

- VanWey, L. K., & Cebulko, K. B. (2007). Intergenerational coresidence among small farmers in Brazilian Amazônia. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1257–1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00445.x

- Wang, J., Chen, T., & Han, B. (2014). Does co-residence with adult children associate with better psychological well-being among the oldest old in China? Aging & Mental Health, 18(2), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.837143

- Wang, J. J., & Lai, D. W. L. (2022). Mental health of older migrants migrating along with adult children in China: A systematic review. Ageing and Society, 42(4), 786–811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001166

- Ward, R. A., & Spitze, G. (1992). Consequences of parent-adult child coresidence. Journal of Family Issues, 13(4), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251392013004009

- Ward, R. A., & Spitze, G. D. (2007). Nestleaving and coresidence by young adult children. Research on Aging, 29(3), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506298225

- Won, Y. H., & Lee, G. R. (1999). Living arrangements of older parents in Korea. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 30(2), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.30.2.315

- Xu, Q., Wang, J., & Qi, J. (2019). Intergenerational coresidence and subjective well-being of older adults in China: The moderating effect of living arrangement preference and intergenerational contacts. Demographic Research, 41, 1347–1372, Article 48. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.48

- Yasuda, T., Iwai, N., Yi, C.-C., & Xie, G. (2011). Intergenerational coresidence in China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan: Comparative analyses based on the east Asian social survey 2006. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42(5), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.42.5.703

- Zhang, Z., Gu, D., & Luo, Y. (2014). Coresidence with elderly parents in contemporary China: The role of filial piety, reciprocity, socioeconomic resources, and parental needs. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(3), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9239-4

- Zhao, L. (2023). China's aging population: A review of living arrangement, intergenerational support, and wellbeing. Health Care Science, 2(5), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/hcs2.64

- Zhong, S., Lee, C., Foster, M. J., & Bian, J. (2020). Intergenerational communities: A systematic literature review of intergenerational interactions and older adults’ health-related outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 264, 113374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113374