ABSTRACT

In the global turn to rights, courts are often reified as central actors in processes of social transformation. In this respect, it is worth recalling the clear-eyed and grounded perspective of Andrea Durbach, who emphasised both the potency and limitation of litigation, as well as the diverse functions of courts. This Festschrift essay assesses the transformative power of socio-economic rights litigation. It begins by setting out the different reasons as to why we would expect (or not) judicial intervention on socio-economic rights to engender social change and then distils some central methodological parameters for assessing and undertaking empirical research. This is followed by an overview of the literature with case studies on housing rights litigation in South Africa and education rights in the United States. This reveals significant variance in material and political outcomes for applicant individuals, communities and social movements but points to key determinants of ‘success’—especially the role of social mobilisation, creation of broad-based alliances, and smart remedies.

Introduction

In reviewing an assessment of Nelson Mandela’s apartheid-era Rivonia trial for sabotage,Footnote1 Andrea Durbach concluded poignantly on the promise of turning to courts for social transformation. Reflecting on the trial's political, legal and performative aspects, she noted that the appraisal was ‘an opportune reminder of the limitations of law's offerings and the potency of its aspirations, and the role of the courtroom as a site for rendering the boundaries of law's progressive application’ (Durbach Citation2018, 269). Her remark, in my view, captures well the central underlying tensions in the scholarship on the impact of courts.

The reason for this prescience is two-fold. First, the idea of courts as a ‘site’ for struggle rather than just as a producer of judgments and orders is central to the aims of much strategic litigation. Courts are leveraged as a political space to shift bargaining relations, articulate demands, shape public opinion. Yet, such a political perspective has often taken a backseat in scholarly research on the role and effects of courts—with a strong material focus on compliance and delivery of public goods. Second, Durbach's focus on litigation's ‘limitation’ and ‘potency’ is welcome in a field that often swings between Panglossianism and scepticism, a relentless battle to prove or disprove that courts can ‘change the world’. This is partly due to an insufficient focus on the methodological choices and normative inclinations that generate diverging results and polarised interpretations. Being willing to see the ‘impact glass’ as both half full and half empty requires a critical empiricism (Redhead Citation2005; Langford Citation2020), with a focus on ‘feasible transformation of the existing world’ (Cox Citation1981, 130).

It is not surprising though that Andrea Durbach's view of the law is grounded and nuanced. The coalface of courtroom litigation has been as much her habitat as the halls of academia. Andrea's career began in the crucible of anti-apartheid criminal defence work in South Africa and continued with her leadership of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) in Australia, where I worked as an intern for her in 1996. Her raucous optimism and critical reflex is not only a striking hallmark of her personality, which triggered a long friendship and many collegial discussions, but it is also a feature of her work in practice and broad-ranging research in academia (see, e.g. Durbach Citation2008; Durbach and Geddes Citation2017; Durbach Citation2017). Whether it has been poverty, legal aid, sexual assault, culture heritage, or human rights commissions, Andrea has drilled down to find, in her words, where law lies ‘between the idea and the reality’ (Durbach Citation2017).

This essay investigates this dissonance in the case of constitutional socio-economic rights, a burgeoning field of jurisprudence, which Andrea has also analysed (see Durbach Citation2008). In the last two decades, the volume of judgments on these rights has risen dramatically—as applicants seek to vitiate their rights to education, housing, health, food, water, social security and work, amongst others. Despite traditional reservations about the justiciability, feasibility and legitimacy of the judicial review of socio-economic rights, decisions can now be found in all regions of the world (see, e.g. Langford Citation2008; Coomans Citation2006; Rossi and Filippini Citation2009; ICJ Citation2008; Langford and Rosevear Citation2022; Liebenberg Citation2008). Applicants have obtained orders that halt evictions, regulate the conditions for water privatisation, require the review of benefit levels, and provide access to medicines. The causes of this phenomenon are diverse. Put simply, it has been driven by a remarkable expansion of the recognition of constitutional socio-economic rights (with Australia constituting a significant exception), the willingness of courts to exercise judicial review powers and facilitate access to justice, closing political opportunity structures and expanding civil society structures, and, to put it more cynically perhaps, the reification of law and litigation in the fields human rights and social justices.

The primary scholarly response to this emergent field has been normative and doctrinal (e.g. Vierdag Citation1978; Fabre Citation2000; Dennis and Stewart Citation2004; Waldron Citation2011; Bilchitz Citation2007; King Citation2012; Gargarella, Domingo, and Roux Citation2006; Abramovich and Courtis Citation2001; Young Citation2008; Liebenberg Citation2010). Nonetheless, the post-judgmental phase of litigation has received increasing attention, and some scholars point to the impact of ground-breaking judgments in a range of countries (Abramovich and Courtis Citation2001; Rebell Citation1998; Winkler and Mahler Citation2013). Yet, others have raised the concern that a significant number of judgments on socio-economic rights remain unimplemented (Wachira and Ayinla Citation2006; Berger Citation2008; CEJIL Citation2003; Byrne and Hossain Citation2008, 143). Others have cast doubt on the relevance and effectiveness of socio-economic rights adjudication as a framework and apparatus for ensuring social justice (Hirschl and Rosevear Citation2012; Thompson and Crampton Citation2002; Pieterse Citation2007), raising the spectre of Hazard’s (Citation1969, 712) prediction that the contribution of courts to social change will be ‘diffuse, microcosmic and dull’.

The essay begins by sketching the different reasons in theory why we would expect (or not) judicial intervention on socio-economic rights to catalyse social impact. It then distils some central methodological parameters and conundrums in undertaking impact research, especially as to how we define impact, set baselines for measurement, and determine causality. This is followed by an overview of the literature with two case studies on education rights in the United States (a representative of the first wave of socio-economic rights litigation in comparative perspective) and housing rights litigation in South Africa (an archetypal representation of the second). As both case studies hail from common law lands, the analysis is complemented by use of examples from elsewhere in the world throughout the paper.

Before beginning though, one caveat should be noted. While the article takes a broad perspective as to what constitutes impact and social transformation, it does not analyse closely to what extent courts might engender or disturb distributive equality for socio-economic rights merely through the form of their orders. For example, there is an extensive scholarly debate over whether Brazilian and other Latin American courts have, in practice, favoured expensive medicines for the middle class rather than basic socio-economic rights for the poor. This is the subject of a separate (and voluminous) branch of scholarship (see, e.g. Ferraz Citation2011; Brinks and Gauri Citation2014; Versteeg Citation2018), which I have also analysed elsewhere (Langford Citation2019).

Explaining adjudicative impact

Reasons for compliance and broader impact

Why would we expect that judicialising socio-economic rights would produce social transformation? Could small and fragmented complexes of lawyers rupture the social policy fabric? Beginning with a focus on the compliance dimension of impact, the presumption that courts possess this transformative potency commonly stems from the assumed coercive power of law and, by extension, judicial institutions. As Bentham (Citation1833) stated, ‘a law by which nobody is coerced’ is a ‘contradiction in terms’ (cited in Yankah Citation2008, 1203). If courts possess the authority to constrain the options of any actor as to how they respect, protect, or fulfil socio-economic rights, and thus force them to do something against their will, implementation of judgments should, ipso facto, follow.

This classical (and realist) conception of law focuses on the judiciary's power to both order sanctions and enforce them (Yankah Citation2008). The latter power—of enforcement—has been visible and manifest in some social-economic rights adjudication. In India, the Supreme Court threatened in M.C. Mehta v Union of India (Citation1998), with some success, to imprison officials if they failed to implement an order to convert motor vehicles to cleaner fuels to protect the right to environmental health (Muralidhar Citation2008; Gauri Citation2010; Shankar and Mehta Citation2008). In Argentina, Bergallo (Citation2011) found that a quarter of sampled right to heath judgments were only implemented only after courts imposed fines on defendant health insurers, providers and authorities. In South Africa, the Constitutional Court has opened the door to money-based claims being made against the assets of the state, which has had consequences for cases concerning medical negligence and failure to pay social security benefits (Nyathi v Member of the Executive Council for the Department of Health Gauteng & Ors (Citation2008)).

However, this coercive view of implementation has been long challenged. Hart (Citation1961) argued that the role of law is primarily normative, providing reasons to act; and Raz (Citation1994) claimed that law affects the calculus of our practical reason and action. While coercion may establish the peculiarity and force of the authoritative institution of law, it may not primarily account for all (or much) of its behavioural influence. According to these accounts, law is persuasive.

Moreover, sociological perspectives point to the cultural function of law. At is simplest level, non-compliance may invite stigmatisation if others are complying—regardless as to whether their motivation is coercive or persuasive. More subtly, the expressive role of law may change social meanings of acceptable behaviour (McAdams Citation2000); and legal norms may be acculturated (Goodman and Jinks Citation2008). How this function works is a matter of debate, but law may affect prevailing ‘civility norms’, which exert significant social and psychological power; or reinforce an ‘already existing normative order’ (Kagan and Skolnick Citation1993). For example, it may explain why Portugal responded so quickly and dramatically in a quasi-judicial finding of the European Committee on Social Rights on failure to take effective steps to prevent child labour (ICJ v Portugal (Citation1998)). The body carries only persuasive authority and child labour is generally considered completely unacceptable, at least amongst the states to which Portugal compares itself.

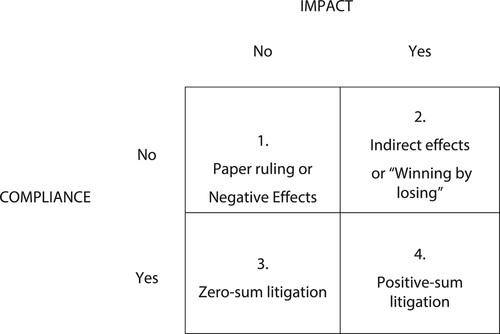

Impact, however, is a broader concept than compliance and thus some additional features of post-litigation effects are needed to complete the picture of potential social transformation. Impact constitutes the total influence or effect of a decision: the result may be greater than mere implementation of the court order or net negative due to unintended consequences. Litigation is an institutional and social process that may trigger additional material, political and symbolic effects. This can be seen in , which is taken from Rodríguez-Garavito and Kauffman (Citation2014), and counterpoises binary scenarios for compliance and overall impact.

In Quadrant 1, a judgment is not enforced and its impact is non-existent or negative. In Quadrant 2, the judgment is not enforced (or even obtained) but the decision has indirect positive effects, so-called ‘winning by losing’. This would also cover a case in which there was no successful judgment, but the litigation itself produced various effects which are considered positive. In Quadrant 3, the positive effects from compliance are cancelled out by broader negative effects: zero-sum litigation. In Quadrant 4, there is positive-sum litigation in which compliance is complemented by broader effects.

A strong focus on compliance occludes these latter three effects. ‘Winning by losing’, for instance, is evident in several studies of rights litigation. Litigants may lose in court but the legal action catalyses various positive effects, from changes in social policies through to the reinvigoration of social movements (McCann Citation1994). The mere process of adjudication is used, for example, to generate pressure on a defendant, highlight an injustice or gap in the law, mobilise a social movement, obtain otherwise unavailable documents, or commence negotiations.

Critical perspectives

It is not difficult, however, to find cases that have gone unenforced or have produced questionable social impact. Many have pointed out the deficiencies in implementation of various high-profile cases. It is commonplace to read that the ground-breaking Government of the Republic of South Africa and Others v Grootboom and Others (Citation2000) judgment in South Africa was poorly implemented; that the flagship Argentinean case of Viceconte (Citation1998) failed to force the government to provide quickly an urgently-needed vaccine for local variant of haemorrhagic fever; or that the eloquently-written Olga Tellis v Bombay Municipal Corporation (Citation1985) case from India simply resulted in the widespread evictions of pavement dwellers in the midst of winter as the Mumbai authorities ignored the recommendations of the Supreme Court to provide alternative accommodation.

If the problems of non-compliance and muted impact are widespread we are thus faced with the questions as to what might be the potential causes? We can identify four counter-hypotheses to those that generate expectations of social transformation.

The first is realism, and is based on the presumption that courts are weak and lack either coercive or authoritative powers. Contrary to the democratic concern that the judiciary will overstep its boundaries, the hypothesis is that the judiciary lacks the strength or means to do so in practice. In the face of resistant politicians, government officials, or deep-pocketed private defendants, judges are powerless to enforce their orders. In realist terms, judicial institutions are mere ‘epiphenomena or surface manifestations of deeper forces operating in society’, and social change only occurs when ‘the balance of these deeper forces shifts’ (Young Citation2001). Scholars such as Rosenberg (Citation1991) have also sought to puncture the causal claims of impact finding that even the ‘success stories’ melt away on closer examination. He postulates, for instance, that the leading civil rights judgment from the US Supreme Court, Brown v Board of Education (Citation1954), was not responsible for progress on school desegregation. Rather it was ‘growing civil rights pressure from the 1930s, economic changes, the Cold War, population shifts, electoral concerns, the increase in mass communication’ that prompted desegregation; the Court simply ‘reflected that pressure; it did not create it’ (Rosenberg Citation1991, 169).

A second alternative hypothesis is that courts are remedially deferential, too sensitive to the democratic objection to the use of their powers to enforce socio-economic rights. They moderate their findings and remedial orders out of deference to the government or other respondents. The result is that the potential impact of socio-economic rights claims is effectively neutered or minimalised. Pieterse (Citation2007, 812, 797) is critical of courts that focus ‘on the coherence, rationality, inclusiveness, and flexibility of legislative or policy measures’, in a way that renders the ‘material needs of socioeconomic rights’ subjects extraneous to the inquiry into constitutional compliance with socioeconomic obligations’.

A third response is that cases concerning socio-economic rights or positive obligations are more complex and costly and therefore more difficult to implement. Courts lack the levers to significantly engineer structural change, demand the reallocation of resources, or facilitate the development of new competences and technologies. Melish (Citation2008) and Courtis (Citation2008) argue respectively that compensation and individual-based orders of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and Argentinean courts (both civil and socio-economic rights) were quickly executed while wider and more structural orders often lagged in implementation. If implementation of socio-economic rights judgments requires enforcing complex or structural remedies, it is not clear that the more binary, individualistic, and time-bound nature of traditional judicial remedies is suitable to the task.

A final bundle of critiques suggests that the turn to, and faith in, courts has a disempowering effect. The problem is not the judgment per se but the entire litigation process. Alternative strategies to adjudication may have achieved a larger, sustainable, or even the same, impact at a lesser price. This may be particularly the case if those other approaches could have generated greater political attention and be perceived as part of a ‘democratic process’. A court victory may also lull relevant actors into a sense of complacency about follow-up: ‘reformers relying on a litigation strategy for reform may be misled (or content?) to celebrate the illusion of change’ (Rosenberg Citation1991, 428).

Conditional approaches

An alternative approach to both these positive and critical expectations is to identify the empirical conditions under which we might expect courts to achieve an impact. As Oran Young (Citation2001, 118) states, ‘Institutions do often emerge as a significant determinant of the course of human affairs. But the causal significance of institutions varies greatly from one setting to another’. For instance, in Goldblatt and Rosa’s (Citation2014) analysis of mobilisation on the right to social security in South Africa, they found that approaches that combine political and legal mobilisation were often more successful than those which concentrated on one strategy.

A straight-forward way of assessing relevant conditional factors is to take a largely rationalist approach and expect actors to respond to socio-economic rights judgments when it is in their interests. For instance, Brinks (Citation2017, 480) argues in the case of implementation that:

At its most basic, the problem of compliance with judicial orders can be reduced to a simple inequality: COMPLY IF Cc < Cd, where Cc is the cost of compliance and Cd is the cost of defiance. In other words, we should observe compliance only if the target of the order considers that compliance would be less costly than non-compliance.

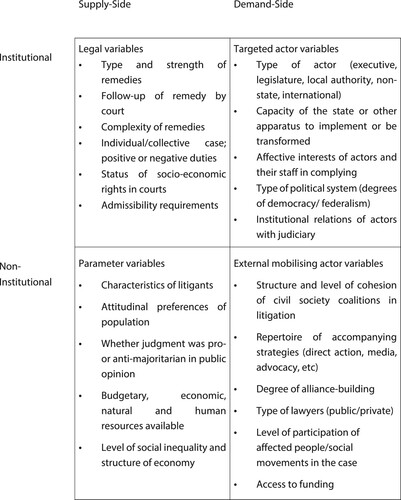

However, our question here extends beyond implementation to include broader impact. This is difficult to capture in a linear relationship of costs and benefits: causal pathways concerning positive and negative effects may be more diffuse and unexpected. Moreover, shifting some of these causal pathways—underlying conditions—may be the actual target of litigation. Nonetheless, we can group different conditional variables that deserve attention (as is done in ). They partly derive from the different hypotheses and counter-hypotheses discussed above. They are categorised firstly as to whether they are supply-side variables, which includes not only the legal system but also more fixed constraints such as resources and religion. The demand-side variables capture the different actors engaged in litigation: the ‘targeted actors’ are those institutions which are expected to respond to litigation while the bottom right-square reflects external actors who mobilise for implementation and impact. For instance, Neumayer (Citation2005) finds that the impact of the ratification of an international human rights treaty is greatest when there is a significant level of civil society activity. The horizontal axis then splits these according to whether the factors are of a more institutional nature or not.

Since the impact of judgments tends to vary considerably, these different conditions may be decisive. The variables of ‘civil society mobilisation’ and ‘bureaucratic contingency’—which are central in Epp’s (Citation2009) research on civil rights and tort law—arise often. in research on socio-economic rights judgments. Indeed, the absence of legal aid for civil rights litigation in many jurisdictions make social rights adjudication and its follow-up heavily dependent on highly organised and resourced civil society organisations and/or the voluntary efforts of lawyers, communities and social movements. As Durbach (Citation2008, 59) states, unlike criminal law, ‘State-sponsored provision of legal services has not attracted parallel application to indigent litigants in civil proceedings, despite a possible adverse result—a “substantial injustice”—due to the litigant’s inability, essentially financial, to negotiate the judicial process’.

Another common conclusion is that the strength of the remedy is decisive (Marcus and Budlender Citation2008; Epp Citation2009). However, it is possible to find many exceptions here. Cases with weaker remedies may have more effect (if they incentivise engagement by the state) while stronger remedies may be important in other types of cases (e.g. if the relevant social group facing significant societal prejudice) (Langford, Garavito-Rodriguez, and Rossi Citation2017). Furthermore, the broader political context matters—with studies finding that stronger democratic governance and rule of law facilitates the implementation of constitutional rights (Schiel, Langford, and Wilson Citation2020).

The methodology of assessing impact

We turn now from the ‘why’ to the ‘how’. How can we establish the impact of socio-economic rights litigation? Determining the impact of any intervention in complex and diachronic social settings is difficult. Measuring the consequences of rights-oriented and constitutional strategies can be even more challenging as the objectives may be value-based, multi-actoral, and multi-temporal. The aim of litigation may not be simply ensuring a single fair trial for a criminal suspect or a water pipe for an individual household but creating the long-term environment for the viable realisation of the rights. Seeking simplistic relationships between interventions and effects may overlook the more complex or intermediate problems that victims, advocates, social movements and non-governmental organisations are seeking to tackle.

Despite these concerns, the task of assessing judicial impact is arguably valid if there are a range of actions available for realising socio-economic rights. Indeed, arguments for the judicialisation of socio-economic rights often feature instrumentalist and consequentialist arguments (Arbor Citation2008). Moreover, such questions are relevant for strategic choices by actors over whether to litigate—to utilise legal opportunity or political opportunity structures (Hilson Citation2002; De Fazio Citation2012). Therefore, perhaps the most important task is to be aware of the customary pitfalls in impact assessments and exercise caution.

Defining impact

What constitutes impact is highly reliant on the particular socio-economic right or the relevant circumstances. The ‘dependent variable’ of impact can be sliced nonetheless in different ways. It is quite common to focus on material impact, judging an intervention ‘effective if it has produced an observable change in the conduct of those it directly targets’—in the desired direction (Rodríguez-Garavito Citation2011b, 1677). To this are often added indirect material effects. For example, a remedy may be restricted to compensation for a single victim but the judgment may precipitate wider accountability effects, catalysing reforms to laws, policies, and programs. The judgment itself may provide a legal precedent that is utilised in future litigation or create a shadow for ongoing policy-making and dispute resolution, filling out the ‘constitutional order’ of socio-economic rights. Alternatively, a remedial order might only require the State reform or develop a policy or law and the court may refrain from granting individual relief. Despite this, the litigants or other actors may be able to utilise the adjudicatory process to leverage more direct gains.

A growing body of literature has sought to also highlight the political and symbolic (attitudinal/recognition) effects of courtroom action, to which Durbach (Citation2018) also points. Indeed, in the context of judicial engagement with post-conflict reparations, Durbach and Chappell (Citation2014, 552) have argued that the political dimensions must be foregrounded: ‘At its most transformative, the representative dimension of any reparation framework will require a reconceptualization of political power’. Turning to courts, Scheingold (Citation1974, 9) noted almost half a century ago, ‘it is necessary to examine both the symbolic and the coercive capabilities which attach to rights’. Politically, litigation may help in mobilising a fragmented social movement or union, leveraging civil society's engagement with the state or private power, creating a confrontation with status quo power relations, or empowering other key actors such as the bureaucracy or local government (Dugard and Langford Citation2011). McCann (Citation1994) for example concludes that the political effects of US litigation for equal pay for equal work (‘rights consciousness’, mobilisation) were more important than entitlements gained—increased wages. Rodríguez-Garavito (Citation2011b, 1680) and others emphasise the symbolic dimension: Litigation can result in ‘changes in ideas, perceptions and collective social constructs relating to the litigation's subject matter’, for example perceptions of the victim group or the seriousness of a problem.

A different or complementary way of dividing up impact is to focus on spatial and temporal dimensions. Botero and Brinks (Citation2022) divide up different types of impact (ideational, discursive, organisational and material) along three spatial axes (social, political, and legal). One can also create temporal taxonomies and separate the intermediate impacts from the ultimate desired effects.Footnote2 This acknowledges that social impact and transformation often first requires affecting mediating actors, policies and discourses. Such intermediate impacts though are not just outcomes, as commonly conceived in ‘program theory’. Instead, they play an important, ongoing but also paradoxical role in rights realisation. On one hand, intermediate effects may be dynamic and not simply temporal. For example, an order may quickly lead to both a new policy and entitlement. In the Minister of Health v Treatment Action Campaign and Others (Citation2002) case in South Africa, a court order for access to neviropane medicine for women with HIV/AIDS triggered broader changes to health policy, in particular access to more costly HIV medicines and participation by health-oriented organisations in public policy-making (Heywood Citation2009).

On the other hand, some of these intermediate effects may be negative from an ultimate impact perspective. For example, a judgment may encourage resource allocation away from groups that deserve priority. It may slow down broader and existing social policy processes by imposing impractical participatory, regulatory, or access requirements. Sometimes the negative consequences may be of a political or symbolic nature. The judgment is successful in stimulating material effects (e.g. access to reproductive health care) but stimulates a political backlash that may affect the sustainability of that access or other sectors of society. In any case, one must be careful about over-emphasising these intermediate impacts if they produce little tangible gain in the long-term. The politics of recognition cannot replace that of redistribution (Fraser Citation2000; Yamin and Gloppen Citation2011).

Baselines and causation

A more difficult question is setting a standard against which such improvements (or regression) is measured. Here, there is no clear consensus in social sciences as to what type of baseline is preferable. One approach is an ideal expectations model that measures impacts against an expectation of effect. On its face, this allows a seemingly objective assessment: the promise of a rights strategy is measured against its eventual outcome (see, e.g. its application in Rosenberg Citation1991). However, the method suffers from the challenge of nailing down an acceptable expectation (Durbach and Chappell Citation2014, 556; Feeley Citation1992). Should a certain judgment or court be expected simply to foster the socio-economic transformation of a society? In particular, how does this strategy take into account constraints that would exist for any alternative approach?

A more feasible and reasonable approach to setting a baseline is examine impact ‘before and after’ the intervention—a no regime counter-factual. One looks for changes that have occurred since the regime intervention, in this case adjudication. The danger though is that this backwards-looking method ignores greater advances that might have occurred if an alternative strategy or tactic was adopted, or the changes might have occurred simply in any case due to other exogenous factors. Thus, even if we can identify post-judgment impact, can we say with certainty that the judgment was the key driver? Tushnet (Citation2008) has noted that some of the ground-breaking judgments of courts in the US have preceded changes in mainstream political opinion by only a few years.

Identifying an alternative regime for a fully-fledged counter-factual analysis would be ideal, but is challenging in practice. It is difficult to conduct a randomised controlled experiment in social policy. One can sometimes compare close-to-identical situations where litigation was not adopted as a strategy (see, e.g. Berry Citation2007) but it is difficult to account for varying initial and intervening conditions. Thus, the common way forward in ‘before and after’ analysis is to consider whether there were viable and better alternatives that promised an equal or better result, examining strategies—such as active mobilisation, policy and law reform, negotiation, media advocacy etc—which were genuinely available. This includes also examining whether a decision generated by another branch of government would have been more effectively implemented.

Since this is an exercise in ‘what-if’, it is of course difficult to identify and assess alternatives. Teasing out these factors can be done by introducing more independent variables into the frame, including the different conditions (as discussed above) that may constrain or facilitate different impacts. Two approaches are common in the literature. First, one can use multivariate regression analysis if different factors can be effectively quantitatively coded (see e.g. Helfer and Voeten Citation2014). Second, one can qualitatively assess the competing alternatives and constraints through ‘process tracing’, investigating and explaining the ‘decision process by which various initial conditions are translated into outcomes’ (George and McKeown Citation1985, 35).

However, such process tracing (or for that matter regression analysis) is rarely decisive. If litigation is truly the last resort, as it is often claimed to be, such a task is not so difficult. But it may not always be and, in such instances, there are questions over how to weigh the different alternatives. For example, some have argued that the PUCL organisation in India in 2000 should have turned to sustained street mobilisation, not litigation, to address starvation deaths and the right to food (see PUCL (People’s Union for Civil Liberties) v Union of India (Citation2001) (PUCL v India) and interview in Langford (Citation2003)); but others point out that the judgment of the Supreme Court of India has been subsequently used to inspire a movement for monitoring the decision (Muralidhar Citation2008). The difficult question in such an abstract counter-factual analysis is whether a grassroots-inspired movement would have succeeded more than the Court-inspired movement.

Benchmarks and interpretation

Finally, even if we can settle on and implement a research design that accounts for causation, the eventual results may be open to different interpretations. This is often because there is no clarity on the relevant benchmark for impact. To put it simply, we may all agree that the glass is half-filled but the debate rages over whether it is ‘half-full’ or ‘half-empty’. When there is no reasonably available benchmark, our normative preferences may guide and frame our conclusions over what is sufficient impact or not.

Interpretation is also strongly affected by one other factor, which tends to constrain or limit what data is analysed. It is the time period for the analysis. Gready (Citation2009) has remarked that one of the dark sides of impact ‘evaluation culture’ is the tendency towards short-termism. In some socio-economic rights cases, key impacts occurred 5 to 10 to 20 years after the judgment requiring making any eventual assessment dependent on what can be viewed as a reasonable period (Langford Citation2014c). Thus, considerable caution should be exercised in any impact analysis in the first few years after a case has been decided, with sufficient respect for temporality, as shall be seen in some of the examples below.

Surveying the evidence

The emerging literature on the impact of socio-economic rights adjudication, especially that which follows a social scientific research design, so far tends to come to mixed results: strong variance in expected effects (Thompson and Crampton Citation2002; Jones and Stokke Citation2005; Gauri and Brinks Citation2008; Rodríguez-Garavito Citation2011a; Yamin and Gloppen Citation2011; S. Wilson Citation2011; Langford et al. Citation2014; Willis Citation2017; K. Young Citation2019). For example, in an in-depth empirical and quantitative study of the material impacts of litigation in five developing countries (Nigeria, South Africa, India, Brazil, Indonesia), Gauri and Brinks (Citation2008) found a significant number of cases which did not shift the status quo, achieving little in practice. At the same time, they found that judicialisation of socio-economic rights might well have averted thousands of deaths and benefitted the lives of millions of others.

Some similar findings have been found in the Global North. For example, in the Hartz IV (Citation2010) decision, the German Federal Constitutional Court considered whether consolidated and significantly reduced unemployment benefits for adults and their dependents contravened the right to a subsistence minimum (see discussion in Bittner Citation2011; Winkler and Mahler Citation2013; Williams Citation2010). The Court affirmed its previous doctrine that its role was not to determine and quantify the relevant amount but rather determine whether the legislature had sought to afford sufficient weight to the constitutional right to dignity and if its calculative and evidentiary methods were justifiable (for a doctrinal discussion, see Kommers and Miller Citation2012, 67; Williams Citation2010, 181–198). The legislature was faulted by the Court on several points: the selection of expenditure categories for the benefit was partially random; the inflationary index was improperly taken from the pension scheme (which was guided by a different rationale); the rate of benefits for dependents was determined in an arbitrary fashion; and the special needs policy was structured in a rigid fashion. The Court provided the state with a year to make a fresh determination but declined to make its order retroactive on economic and fiscal grounds. After multi-stakeholder negotiations, new legislation was adopted. The principal results were a rise in children's benefits with a new calculation method and a reform to the special needs policy in substance and process. Bittner (Citation2011, 1955) notes that there was significant discretion for the state but ‘the procedural standard formulated in the Hartz IV decision substantively affect[ed] the legislature's choice as to policy’.

Others researchers focus on the political effects of socio-economic rights litigation: Muralidhar (Citation2008) notes—as discussed above—how litigation on right to food in India (PUCL v India (Citation2001)) precipitated larger social movements; Rodríguez-Garavito (Citation2011a) points to the shift in public discourse on internally displaced persons after the Constitutional Court of Colombia's T-025 (Citation2004) judgment on their civil and socio-economic rights; and Abramovich notes that even when advocates in a flagship case like Viceconte struggled through years of implementation to produce the necessary vaccine, the decision laid the ground for other cases to succeed, for example on HIV/AIDS medicines (Langford Citation2003). Even the unsuccessful Mazibuko and Others v City of Johannesburg and Others (Citation2010) litigation on the right to water in South Africa—which sought a halt in the use of pre-paid water metres and an increase in the average daily amount of free water from 25 to 50 litres—achieved a range of curious impacts. The City of Johannesburg conceded that the litigants were right to raise the issues concerning policy design (Jones, Langford, and Smith Citation2010), a concession soon reflected in policy (Dugard, Langford, and Anderson Citation2014).

We can observe these trends—and variance in in material, political and symbolic impacts—more closely in examination in two case studies from the United States and South Africa.

United States – education rights

The first country to experience socio-economic rights litigation, and in a sustained fashion, was the United States. This phenomenon provides a fascinating comparative insight—a ‘similar systems design’ (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008; Meckstroth Citation1975). In contrast to the US Federal Constitution (Citation1789), all 50 state constitutions contain rights-like provisions on education (Hickrod et al. Citation1995, 51). The provisions range from a mere ‘duty to promote this important object’ (article 8(1)(1) in the Maine Constitution (Citation1820)) through to a ‘paramount duty’ to make ‘ample provision for the education of all children’ (article 9 in the Washington Constitution (Citation1889))—for an overview, see Pauley v Kelly (Citation1979) (Appendix 1). Yet, while state legislatures had been largely resistant to reducing the heavy reliance on local taxes for school financing, and the quality of schooling remained highly dependent on average municipal income and wealth (Horowitz Citation1965-Citation1966), courts responded with extreme caution to claims based on these rights and duties. Only if legislation was clearly irrational or arbitrary, would courts feel compelled to intervene—and that was rare and limited (see People ex rel. Russell v Graham (Citation1922); Mumme v Marrs (Citation1931); Flory v Smith (Citation1926)).

However, in the 1960s, the issue was revived in the wake of the Brown v Board of Education (Citation1954). The Supreme Court had waded into the topic of education and the judgment catalysed a new turn to the courts on unequal school financing. In the so-called first wave, plaintiffs requested that statutes that authorised unequal educational expenditures violated the civil right of equal protection. The federal courts acknowledged the deep inequality in the financing and quality of education but found the claim non-justiciable (McInnes v Shapiro (Citation1968); see also Burress v Wilkerson (Citation1969)). Legal advocates then shifted strategy away from a predetermined equality formula to a justification standard, which only produced short-lived results (Andersen Citation1979-Citation1980, 146). In San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez (Citation1973), the US Supreme Court ruled that wealth could not be a suspect class in the domain of education like race; and education, at least beyond the barest minimum, was not a federal constitutional right.

This loss sparked a second wave of litigation that focused on express rights to education in state constitutions. It proved more successful. Many state courts rejected the earlier and restrictive justiciability doctrines concerning education rights, most comprehensively in Seattle School District No. 1 (Citation1978). In the landmark case for this second ‘equity wave’, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in Robinson v Cahill (Citation1973) that the school financing system was violated the education right in the constitution. While the legal standard was open-textured, it was demanding: the system must provide a ‘thorough and efficient education’ for all children (513). This meant that the state was faced with achieving a particular result but that there was considerable flexibility in the means to be applied. The Court found that the test for review was whether New Jersey could demonstrate it has ‘a plan which will fulfil the State’s continuing obligation’ (518), and the plan must define in some sufficiently the educational obligation and contain a financing mechanism for that purpose. Yet, it found neither was in place. Refusing requests for supervisory jurisdiction or specific orders, the Court granted the state nine months to develop a new plan, with the condition that equal financing would be automatically ordered in its absence.

In the next wave of litigation, there was a decisive shift from equity to adequacy: i.e. all students had a right to a threshold level of education. It was driven by the particularities of constitutional provisions (Thompson and Crampton Citation2002), the perception than adequacy claims were more justiciable (see Heise Citation1995, 1161; Olsen v State (Citation1976)), a recognition that finance inequities were only one cause of inadequate education, and that the public and courts were more attuned to measures of standardised achievement (Heise Citation1995). In the most well-known adequacy case, Rose v Council for Better Education (Citation1989), the Supreme Court of Kentucky specified that the duty to provide an efficient system of education meant providing each and every child with seven particular capacities. The Court then cited a range of evidence suggesting that the Kentucky system failed in this regard (and financial and educational efforts were wanting) and made a single order declaring the ‘entire system of common schools’ unconstitutional and remitted the matter to the legislature.

Turning to the impact of this school finance litigation, the key finding is variance. There were remarkable changes in some states and little in others. There is not room here to overview the empirical and contested literature on impact—with more than two hundred scholarly publications already by 2002 (Thompson and Crampton Citation2002) but a few headlines can be proffered. The first is that the court orders were generally successful in increasing funding for schools over time (Hickrod et al. Citation1992; Thompson and Crampton Citation2002). Berry’s (Citation2007) quantitative and multivariate analysis of all states between 1970 and 2003 indicates that the presence of a positive judgment ‘provides roughly $450 per pupil in additional revenue’ which ‘represents about 14 per cent of mean per-pupil state education revenue’. This was only partially offset by a decrease in local funding or other changes in state-local funding.

The second is that inequity had partially decreased. Initial studies in the 1970s and 1980s pointed to very modest changes or little change (see e.g. Goertz Citation1983). Yet, in a longitudinal perspective, it is possible to observe a narrowing of inequalities after the last two waves of litigation. Berry (Citation2007) demonstrates that the Gini gap decreased by about 16 per cent while the bulk of the financing gains have accrued to low-income districts with median-income districts partly benefiting.

The third is that increases in the quality of education have been more elusive. In some celebrated instances, such as the Kentucky litigation, there were dramatic adequacy gains as the state moved up subsequently the national rankings (Shanor and Albisa Citation2015). However, the aggregate effects on the quality of schooling, one of the aims of the adequacy wave, have been more difficult to achieve (Hanushek and Lindseth Citation2009).

The fourth is that the political impacts may vary. Even sceptical scholars such as Thompson and Crampton (Citation2002, 148–149) concede that ‘school finance has received heightened scrutiny as a result of litigation’, but they also point out the costs in litigation and the increased centralisation of schooling that it has brought.

South Africa – housing rights

An equally illustrative example of these varied outcomes and dynamics can be found in the housing rights cases in South Africa, beginning with the case of South Africa v Grootboom (Citation2000). This judgment is the most widely-known and celebrated judgment on socio-economic rights with its eloquent finding on justiciability—but one which has also faced criticism for lack of impact.

The Grootboom ‘community’ consisted of 390 adults and 510 children, living perilously on the eastern fringe of the Cape Metropolitan Area, in the Wallacedene informal settlement. After the settlement became waterlogged they moved onto an adjacent vacant private property. It was earmarked, however, for low-cost housing and, three months later on 8 December 1998, the community was issued with an eviction order, even though they were unrepresented in court. Despite their subsequent negotiation of agreement with the Oostenburg municipality that provided for vacation of the land by 19 May 1999, together with a municipal promise to identify alternative land, they were evicted again, their homes bulldozed and settlement burned down. Rendered homeless, they took shelter on the Wallacedene sports field.

After protests fail to move the municipality, a court claim was filed in May 1999 (Marcus and Budlender Citation2008). The community requested in their filing that the state respondents ‘provide adequate and sufficient basic temporary shelter and/or housing for the applicants and their children’ pending permanent accommodation and that ‘adequate and sufficient basic nutrition, shelter, health and care services and social services’ be provided to all of the applicants’ children in the interim. The High Court in Grootboom v Oostenberg Municipality (Citation2000) responded by only enforcing the immediate rights of children under Section 28 of the Constitution and ordered that ‘tents, portable latrines and a regular supply of water’ be provided within three months to families (295). However, no order was given for adults without children.

The community appealed to the Constitutional Court. During the subsequent process, a partial settlement was reached between the parties. The municipality was to provide immediate funding for materials and delivery of temporary toilet and sanitation facilities, as well as materials to waterproof residents’ shacks. The Court then addressed the broader obligations of the state. It found that the government authorities had failed to develop an adequate housing program which was directed towards providing emergency relief for those without access to basic shelter. This violated its duty to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of the constitutional right to have access to adequate housing, as set out in Section 26(2) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Citation1996). In language not dissimilar to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ General Comment No. 3 (Citation1990), the Court expressed the obligation in the following terms:

The measures [by government] must establish a coherent public housing program directed towards the progressive realisation of the right of access to adequate housing within the State’s available means. The program must be capable of facilitating the realisation of the right. The precise contours and content of the measures to be adopted are primarily a matter for the Legislature and the Executive. They must, however, ensure that the measures they adopt are reasonable. (South Africa v Grootboom (Citation2000), para. 41)

To be sure, the judgment can be critiqued for minimalism. It was deferential as to other aspects of government housing policy and eschewed the opportunity to set a minimal standard for the right to housing and press the state to consider equity in housing policy design (Roux Citation2002; Liebenberg Citation2008; Langford Citation2014a). Equally importantly, and of direct relevance here, the decision is used as a or the prime example for demonstrating the weak or negligible impact of courts. Pieterse (Citation2008, 808) strikes a common tone when he says that ‘there was limited compliance with the order’ and more ‘significantly, the order did not result in the alleviation of the housing needs of the successful litigants’. This critique was heightened by the death of the lead applicant. It was widely reported that in August 2008, Mrs Grootboom died ‘homeless and penniless’ in her shack in Wallacedene (Joubert Citation2008). For critics, these results revealed the lack of potency of socio-economic rights litigation (Hirschl Citation2004).

These broad empirical brushstrokes concerning the case's impact obscure though different methodological assumptions and the evidence is second-hand and out-dated: a 2005 newspaper article is the most commonly cited source (see Gauri and Brinks Citation2008; Hirschl Citation2004; Hirschl and Rosevear Citation2012; Yamin and Gloppen Citation2011; Chilton and Versteeg Citation2017). Moreover, the causal factors are often not analysed and the results are generalised without testing the conclusions against an array of cases that arose in similar circumstances. Using a range of sources, I have assessed previously the impact of the Grootboom case and the results are shown in (Langford Citation2014b), which sets out the material, political and symbolic effects.

Table 1. Impacts of the Grootboom case.

Even though the court's order was limited—endorsing a settlement order for basic material for the community and requiring only the establishment of an emergency housing program for persons in desperate need—its impacts have been much broader than acknowledged. The community avoided further eviction, improved access to basic services, gained eventually access to permanent housing, helped catalyse the development of an emergency housing policy (although poorly implemented), developed the jurisprudential foundation for socio-economic rights litigation, and helped slow a pattern of large-scale evictions.

Of key importance is that that 90 per cent of the community achieved permanent housing by 2012 (Langford Citation2014b). In the wake of the judgment, the local municipality developed a housing plan for the local area even though it was not formally required. Its implementation though was delayed until 2012 by the fact that other communities were judged to be in a needier situation and that building contractor corruption frustrated the delivery process. Politically, the judgment also helped lead to the formation of a community-wide housing forum for slumdweller groups as they engaged with municipal housing plans although the community's own self-organisation was not particularly well-sustained. However, while the judgment spawned a number of other broader material effects, its systemic political and symbolic effects were mild if not negligible; and certainly did not reach the impacts generated by the concurrent legal mobilisation by the Treatment Action Campaign on HIV/AIDS (on the latter, see Heywood Citation2009).

Even less analysed is the impact of subsequent housing rights litigation that emerged from identical circumstances, namely attempted forced evictions by public authorities. In many of these cases, a similar dynamic emerged: a negative violation triggered positive demands. Communities invoked the right to housing as they mounted counter-claims for better housing or improved alternative accommodation. These cases therefore present an opportunity to try to identify some broader trends in impact and conditions. The seven chosen cases are set out in and analysed in-depth elsewhere in Langford (Citation2014b). In drawing together what we know about the different cases—largely material and political impacts—we can plot them in binary form. lists five types of direct impacts for communities together with two broader indirect impacts.Footnote3 A score of 1 is given if there was a substantial change in these dependent variables after litigation and 0 if there was not.

Table 2. Community and systemic impacts of eight ‘evictions’ cases.

The results suggest that, in the majority of cases, litigation has helped prevent evictions, immediately improve basic services (although to varying degrees), strengthened community organisation, and forced local municipalities to innovate their policies. However, permanent housing was only achieved in some cases. The last column also gives the average score across all factors. Here again variance is clearly the only constant. Equally importantly though, these cases display some conditions for success. In resisting urban displacement, highly fragmented communities, which otherwise struggled to form nation-wide social movements, relied successfully and heavily on alliances with legal professionals and local social movements or responsive judges who were willing to develop creative remedies that leveraged greater rates of compliance.

Discussion

Drawing together the discussion of the US and South African case studies in a comparative and scholarly context, we can make several observations about the nature of the impact of socio-economic rights litigation. First, there is variation in the degree of impact across cases, strengthening the argument that court-driven social transformation is highly conditional. Some cases generated tremendous impact, others little, while longitudinal studies demonstrate modest or moderate effects on average. In the United States, education rights litigation has catalysed clearly increased school funding but effects on finance equality and educational quality are more muted. In South Africa, housing rights litigation has produced some concrete eviction protections on the ground and especially in jurisprudence (Wilson and Dugard Citation2014).

Second, the political and symbolic dimension of courts as ‘sites for struggle’ is perhaps equally important as their material role. In the case studies, courts were mobilised for agenda setting, issue framing, negotiations and rallying points for social mobilisation and political pressure. In the United States, education rights litigation became a rallying and mobilising point for movements of activists, school bureaucrats and parents while in South Africa courts created an infrastructure for reducing power asymmetries between vulnerable communities and better-resourced authorities.

Third, and finally, the research is beset by divergent interpretations over the effects of the same cases, reflecting the role and importance of methodological choices and interpretation. This indicates the seminal nature of the field in comparative perspective and the importance of scrutinising critically claims and counter-claims of compliance, impact and social transformation.

Conclusion

This essay began with Durbach’s (Citation2018) observation that courts carry a material and political potency to engender social transformation but their limitations are equally apparent. In the case of the emergent field of socio-economic rights litigation, this is arguably clearly the case. With the support of courts, individuals, communities and social movements have been able to inflect social policy, gain access to public goods, and challenge existing power relations and discursive categories. However, the research is also replete with cases that failed to move the impact needle in any substantive fashion.

What then for the role for courts and litigation? Some suggest that the way forward is to enhance the power of adjudicators through improving their remedial procedures, pushing them to make more progressive rulings, or decrease the cost of access. For instance, a review of the implementation of international and regional human rights decisions directed almost all of its proposals towards improving the ‘procedures in place in each system to monitor implementation and follow-up with states’ (OSJI Citation2010; OSJI Citation2013). However, the reasons behind impact and compliance vary too much, and the variables of ‘civil society mobilisation’ and ‘bureaucratic contingency’ arise often.Footnote4 These two variables correspond to Brink's cost inequality: civil society may be able to increase the cost of non-compliance, while bureaucratic or political resistance may deepen the cost of compliance. The importance of these two factors seems to apply regardless of whether the remedy is complex or not; and thus should occupy the minds of lawyers and movement leaders when choosing and designing litigation strategies.

These lessons are equally relevant for courts and constitution designers. Courts, for example, should consider how to make a difference to these power and interest relations, and influence either side of the equation. Can they, in particular, provide additional support for more disadvantaged applicants who cannot mobilise or face hostile public opinion (Dobrushi and Alexandridis Citation2017). This might be made manifest through stronger forms of scrutiny, remedies, procedural innovations or efforts to help applicants link with support structures. It is the latter which has been particularly the focus in the work of Andrea Durbach.

On the other side, courts may adopt stronger or more reflexive remedies that aim to lessen resistance. This is a strategic question. Stronger remedies may force compliance, but they may also trigger deeper resistance. While reflexive remedies may invite compliance given the display of trust, they may be easily ignored. Research by Rodríguez-Garavito (Citation2011b) and Çali and Wyss (Citation2011) amongst others suggests that more reflexive approaches may catalyse greater action.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Andreas Føllesdal and Geir Ulfstein for helpful comments on the first draft. The section on the United States cases partly draws on Langford (Citation2019) and the section on South African housing cases partly draws on Langford (Citation2014b).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Malcolm Langford

Malcolm Langford is a Professor of Public Law, the University of Oslo and Director of the Centre on Experiential Legal Learning (CELL), a Centre for Excellence in Education (SFU). He is also an Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Bergen, and former Co-Director of the Cente on Law and Social Transformation, University of Bergen and CMI and visiting fellow at the University of California (Berkeley), University of NSW and the University of Stellenbosch.

Notes

1 The assessment is contained in Allo (Citation2015).

2 I am indebted to discussions with Dan Brinks and Peris Jones for the temporal typology set out in this sub-section.

3 Some of the cases have publicly available judgments. These are Modderklip (President of the Republic of South Africa v Modderklip Boedery (Citation2005)); Valhalla (City of Cape Town v Rudolph and Others (Citation2004)); Olivia Rd (Occupiers of 51 Olivia Road Berea Township and 197 Main Street Johannesburg v the City of Johannesburg and others (Citation2008)) and Joe Slovo (Residents of the Joe Slovo Community, Western Cape v Thubelisha Homes and others (Citation2010)).

4 Note the study by B. Wilson and Rodríguez (Citation2017) which finds that social rights judgments directed against smaller public and private entities were more likely to be implemented than decisions against larger ones.

References

- ICJ. 2008. Courts and the Legal Enforcement of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Comparative Experiences of Justiciability. Geneva: International Commission of Jurists.

- ICJ v Portugal. 1998. Complaint No. 1/1998, Decision on the Merits (European Committee on Social Rights).

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). 1990. General Comment 3, The nature of States Parties’ Obligations (Art 2, Para 1 of the Covenant). December 14, 1990. E/1991/23.

- Viceconte Mariela v Estado nacional – Ministerio de Salud y Acción Social s/amparo ley 16.986. 1998. 2 June 1998 (Federal Administrative Court, Chamber IV, Argentina).

- T-025. 2004. (Constitutional Court of Colombia).

- Hartz IV. 2010. In 1 BVL 1/09, 1 BVL 3/09, 1 BVL 4/09. (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany).

- M.C. Mehta v Union of India. 1998. 6 SCC 63 (Supreme Court of India).

- Olga Tellis v Bombay Municipal Corporation. 1985. 3 SCC 545 (Supreme Court of India).

- PUCL (People’s Union for Civil Liberties) v Union of India. 2001. 5 SCALE 3 (Supreme Court of India).

- City of Cape Town v Rudolph and Others. 2004. (5) SA 39 (C) (High Court of Cape Town).

- Government of the Republic of South Africa and Others v Grootboom and Others. 2000. (11) BCLR 1169 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Grootboom v Oostenberg Municipality. 2000. 3 BCLR 277 (C) (High Court of South Africa, Cape of Good Hope Provincial Division).

- Mazibuko and Others v City of Johannesburg and Others. 2010. (4) SA 1 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Minister of Health and Others v Treatment Action Campaign and Others (1). 2002. (10) BCLR 1033 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Nyathi v Member of the Executive Council for the Department of Health Gauteng & Ors. 2008. (5) SA 94 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Occupiers of 51 Olivia Road Berea Township and 197 Main Street Johannesburg v the City of Johannesburg and others. 2008. (3) SA 208 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- President of the Republic of South Africa v Modderklip Boedery (Pty) Ltd. 2005. (5) SA 3 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Residents of the Joe Slovo Community, Western Cape v Thubelisha Homes and others. 2010. (3) SA 454 (CC) (Constitutional Court of South Africa).

- Burress v Wilkerson 310 F.Supp. 572. 1969. (District Court, W. D. Virginia, United States).

- Brown v Board of Education 347 U.S. 483. 1954. (Supreme Court of the United States).

- Flory v Smith 134 S.E. 360. 1926. (Supreme Court of Virginia, United States).

- McInnes v Shapiro 293 F.Supp. 327. 1968. (District Court N. D. Illinois, United States).

- Mumme v Marrs 120 Tex. 383. 1931. (Supreme Court of Texas, United States).

- Olsen v State 554 P.2d 139. 1976. (Supreme Court of Oregon, United States).

- Pauley v Kelly 225 s.E.2d 859. 1979. (Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia, United States).

- People ex rel. Russell v Graham 301 Ill. 446, 134 N.E. 57. 1922. (Supreme Court of Illinois, United States).

- Robinson v Cahill 63 N.J. 196. 1973. 306 A.2d 65 (Supreme Court of New Jersey, United States).

- Rose v Council for Better Education 790 S.W.2d 186. 1989. (Supreme Court of Kentucky, United States).

- San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez 411 U.S. 1. 1973. (Supreme Court of the United States).

- Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of. 1996.

- Constitution of the United States of America. 1789 as amended.

- Maine Constitution. 1820 as amended (including 2013 Rearrangement).

- Washington Constitution. 1889 as amended.

- Abramovich, Victor, and Christian Courtis. 2001. Los derechos sociales como derechos exigibles. Madrid: Trotta.

- Allo, Awol, ed. 2015. The Courtroom as a Space of Resistance: Reflections on the Legacy of the Rivonia Trial. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Andersen, William R. 1979-1980. “School Finance Litigation – The Styles of Judicial Intervention.” Washington Law Review 55: 137–175.

- Arbor, Louise. 2008. “Human Rights Made Whole.” Project Syndicate. June 26, 2008. http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/human-rights-made-whole.

- Bentham, Jeremy. 1833. The Works of Jeremy Bentham. Vol. II, Edinburgh: William Tait.

- Bergallo, Paula. 2011. “Argentina: Achieving Fairness Despite ‘Routinization’?” In Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health?, edited by Alicia Ely Yamin and Siri Gloppen, 43–75. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Berger, John. 2008. “Litigating for Social Justice in Post-Apartheid South Africa: A Focus on Health and Education.” In Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World, edited by Varun Gauri and Daniel Brinks, 38–99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berry, Christopher. 2007. “The Impact of School Finance Judgments on State Fiscal Policy.” In School Money Trials: The Legal Pursuit of Educational Adequacy, edited by Martin R. West and Paul E. Peterson, 213–240. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

- Bilchitz, David. 2007. Poverty and Fundamental Rights: The Justification and Enforcement of Socio-Economic Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bittner, Claudia. 2011. “Human Dignity as a Matter of Legislative Consistency in an Ideal World: The Fundamental Right to Guarantee a Subsistence Minimum in the German Federal Constitutional Court’s Judgment of 9 February 2010.” German Law Journal 12 (11): 1942–1960.

- Botero, Sandra, and Daniel Brinks. 2022, forthcoming. “A Matter of Politics: The Impact of Courts in Social and Economic Rights Cases.” In Oxford Handbook on Economic and Social Rights, edited by Malcolm Langford and Katherine Young. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brinks, Daniel. 2017. “Solving the Problem of (non)Compliance in SE Rights Litigation.” In Making it Stick: Compliance with Social Rights Judgments in Comparative Perspective, edited by Malcolm Langford, Cesar Garavito-Rodriguez, and Julietta Rossi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brinks, Daniel, and Varun Gauri. 2014. “The Law’s Majestic Equality? The Distributive Impact of Judicializing Social and Economic Rights.” Perspectives on Politics 12 (2): 375–393.

- Byrne, Iain, and Sara Hossain. 2008. “South Asia: Economic and Social Rights Case Law of Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.” In Social Rights Jurisprudence: Emerging Trends in International and Comparative Law, edited by Malcolm Langford, 125–143. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Çali, Başak, and Anne Koch. 2016. “Lessons Learnt from Implementation of Civil and Political Rights Judgments.” In Making it Stick: Compliance with Social Rights Judgments in Comparative Perspective, edited by Malcolm Langford, Cesar Garavito-Rodriguez, and Julietta Rossi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Çali, Basak, and Alica Wyss. 2011. “Why Do Democracies Comply with Human Rights Judgments? A Comparative Analysis of the UK”, Ireland and Germany. Working Paper.

- CEJIL. 2003. “Unkept Promises: The Implementation of the Decisions of the Commission and the Court.” Gazette 10.

- Chilton, Adam, and Mila Versteeg. 2017. “Rights Without Resources: The Impact of Social Rights on Social Spending.” The Journal of Law and Economics 60 (4): 713–748.

- Coomans, Fons, ed. 2006. Justiciability of Economic and Social Rights: Experiences from Domestic Systems. Antwerpen: Intersentia and Maastrict Centre for Human Rights.

- Courtis, Christian. 2008. “Argentina: Some Promising Signs.” In Social Rights Jurisprudence: Emerging Trends in International and Comparative Law, edited by Malcolm Langford, 163–181. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cox, Robert. 1981. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium - Journal of International Studies 10 (2): 126–155.

- De Fazio, G. 2012. “Legal Opportunity Structure and Social Movement Strategy in Northern Ireland and Southern United States.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 53 (3): 3–22.

- Dennis, Michael, and David Stewart. 2004. “Justiciability of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights: Should There Be an International Complaints Mechanism to Adjudicate the Rights to Food, Water, Housing, and Health?” American Journal of International Law 98: 462–515.

- Dobrushi, Andi, and Theodoros Alexandridis. 2017. “International Housing Rights and Domestic Prejudice: The Case of Roma and Travellers.” In Social Rights Judgments and the Politics of Compliance: Making it Stick, edited by Malcolm Langford, Cesar Garavito-Rodriguez, and Julietta Rossi, Ch. 13, 436–472. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dugard, Jackie, and Malcolm Langford. 2011. “Art or Science? Synthesising Lessons from Public Interest Litigation and the Dangers of Legal Determinism.” South African Journal on Human Rights 27 (3): 39–64.

- Dugard, Jackie, Malcolm Langford, and Edward Anderson. 2014. “Determining Progress on Access to Water and Sanitation: Law and Political Economy in South Africa.” In The Right to Water: Theory, Practice and Prospects, edited by Malcolm Langford and Anna Russell, 225–275. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Durbach, Andrea. 2008. “The Right to Legal Aid in Social Rights Litigation.” In Social Rights Jurisprudence: Emerging Trends in International and Comparative Law, edited by Malcolm Langford, 59–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Durbach, Andrea. 2017. “‘Between the Idea and the Reality’: Securing Access to Justice in an Environment of Declining Points of Entry.” In Law and Poverty in Australia: 40 Years after the Sackville Report, edited by Andrea Durbach, Brendan Edgeworth, and V. Sentas, 214–230. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Durbach, Andrea. 2018. “Review of ‘The Courtroom as a Space of Resistance: Reflections on the Legacy of the Rivonia Trial’.” Social & Legal Studies 27 (2): 266–269.

- Durbach, Andrea, and Louise Chappell. 2014. “Leaving Behind the Age of Impunity: Victims of Gender Violence and the Promise of Reparations.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 16 (4): 543–562.

- Durbach, Andrea, and Lucy Geddes. 2017. “‘To Shape Our Own Lives and Our Own World’: Exploring Women’s Hearings as Reparative Mechanisms for Victims of Sexual Violence Post-Conflict.” The International Journal of Human Rights 21 (9): 1261–1280.

- Epp, Charles. 2009. Making Rights Real: Activists, Bureacrats, and the Creation of the Legalist State. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fabre, Cécile. 2000. Social Rights Under the Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Feeley, Malcolm. 1992. “Hollow Hopes, Flypaper, and Metaphors, Review of ‘The Hollow Hope’: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? By Gerald N. Rosenberg.” Law & Social Inquiry 17 (4): 745–760.

- Ferraz, Octavio L. Motta. 2011. “Brazil: Health Inequalities, Rights and Courts.” In Litigating Health Rights: Can Courts Bring More Justice to Health?, edited by Alicia Ely Yamin and Siri Gloppen, 76–102. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2000. “Rethinking Recognition.” New Left Review 3: 107–120.

- Gargarella, Roberto, Pilar Domingo, and Theunis Roux. 2006. Courts and Social Transformation in New Democracies: An Institutional Voice for the Poor? Aldershot/Burlington: Ashgate.

- Gauri, Varun. 2010. “Public Interest Litigation in India: Overreaching or Underachieving?” Indian Journal of Law and Economics 1: 71–93.

- Gauri, Varun, and Daniel Brinks. 2008. Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- George, Alexander L., and Timothy J. McKeown. 1985. “Case Studies and Theories of Organizational Decision Making.” Advances in Information Processing in Organizations 2: 21–58.

- Goertz, Margaret E. 1983. “School Finance in New Jersey: A Decade after Robinson v. Cahill.” Journal of Education Finance 8 (4): 475–489.

- Goldblatt, Beth, and Solange Rosa. 2014. “Social Security Rights.” In Symbols or Substance? The Role and Impact of Socio-Economic Rights Strategies in South Africa, edited by Malcolm Langford, Ben Cousins, Jackie Dugard, and Tshepo Madlingozi, 253–274. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodman, Ryan, and Derek Jinks. 2008. “Incomplete Internalization and Compliance with Human Rights Law.” European Journal of International Law 19 (4): 725–748.

- Gready, Paul. 2009. “Reasons to Be Cautious About Evidence and Evaluation: Rights-Based Approaches to Development and the Emerging Culture of Evaluation.” Journal of Human Rights Practice 1 (3): 380–401.

- Hanushek, Eric, and Aldred A. Lindseth. 2009. Schoolhouses, Courthouses, and Statehouses: Solving the Funding-Achievement Puzzle in America’s Public Schools. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hart, H. L. A. 1961. The Concept of Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hazard, G. 1969. “Social Justice Through Civil Justice.” University of Chigaco Law Review, 36: 699–712.

- Heise, Michael. 1995. “State Constitutions, School Finance Litigation, and the Third Wave: From Equity to Adequacy, Heise, Michael.” Temple Law Review 68: 1151–1176.

- Helfer, Laurence, and Erik Voeten. 2014. “International Courts as Agents of Legal Change: Evidence from LGBT Rights in Europe.” International Organization 68 (1): 77–110.

- Heywood, Mark. 2009. “South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign: Combining Law and Social Mobilization to Realize the Right to Health.” Journal of Human Rights Practice 1 (1): 14–36.

- Hickrod, A., Ramesh Chaudhari, Gwen Pruyne, and Jin Meng. 1995. “The Effect of Constitutional Litigation on Education Finance: A Further Analysis.” In Selected Papers in School Finance 1995, edited by William Fowler, 37–57. Washington: National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

- Hickrod, A., Edward Hines, Gregory Anthony, John Dively, and Gwen Pruyne. 1992. “The Effect of Constitutional Litigation on Education Finance: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Education Finance 18 (2): 180–210.

- Hilson, C. 2002. “New Social Movements: The Role of Legal Opportunity.” Journal of European Public Policy 9 (2): 238–255.

- Hirschl, Ran. 2004. Towards Juristocracy: The Origins and Consequences of the New Constitutionalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hirschl, Ran, and Evan Rosevear. 2012. “Constitutional Law Meets Comparative Politics: Socio-Economic Rights and Political Realities.” In The Legal Protection of Human Rights — Sceptical Essays, edited by Tom Campbell, K. D. Ewing, and Adam Tomkins, 207–228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horowitz, Harold. 1965-1966. “Unseparate but Unequal – The Emerging Fourteenth Amendment Issue in Public School Education.” UCLA Law Review 13: 1147–1172.

- Jones, Peris, Malcolm Langford, and Tara Smith. 2010. The South Africa Programme: Final Report 2005-2009. Oslo: Norwegian Centre for Human Rights (Oslo).

- Jones, Peris, and Kristian Stokke, eds. 2005. Democratising Development: The Politics of Socio-Economic Rights in South Africa. Leiden: Martinus Nihjhoff.

- Joubert, Pearlie. 2008. “Grootboom Dies Homeless and Penniless.” Mail & Guardian. August 8, 2008. http://www.mg.co.za/article/2008-08-08-grootboom-dies-homeless-and-penniless.

- Kagan, Robert A., and Jerome Skolnick. 1993. “Banning Smoking: Compliance Without Coercion.” In Smoking Policy: Law, Policy and Politics, edited by Robert Rabin and Stephen Sugarman, 69–94. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- King, Jeff A. 2012. Judging Social Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kommers, Donald, and Russell Miller. 2012. The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2003. Litigating Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Achievements, Challenges and Strategies. Geneva: Centre on Housing Rights & Evictions.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2008. Social Rights Jurisprudence: Emerging Trends in International and Comparative Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2014a. “Homo Politicus or Homo Sapiens? Underlying Conceptions of Equality in Legal Rights.” Presented at the Law & Society Association, Minneapolis, 29 May-1 June 2014.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2014b. “Housing Rights Litigation: Grootboom and Beyond.” In Symbols or Substance? The Role and Impact of Socio-Economic Rights Strategies in South Africa, edited by Malcolm Langford, Ben Cousins, Jackie Dugard, and Tshepo Madlingozi, 187–225. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2014c. “Introduction: Civil Society and Rights in Context.” In Symbols or Substance? The Role and Impact of Socio-Economic Rights Strategies in South Africa, edited by Malcolm Langford, Ben Cousins, Jackie Dugard, and Tshepo Madlingozi, 1–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2019. “Judicial Politics and Social Rights.” In The Future of Economic and Social Rights, edited by Katherine Young, 66–109. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Langford, Malcolm. 2020. “Taming the Digital Leviathan: Automated Decision-Making and International Human Rights.” American Journal of International Law 114: 141–146.

- Langford, Malcolm, Ben Cousins, Jackie Dugard, and Tshepo Madlingozi, eds. 2014. Socio-Economic Rights in South Africa: Symbols or Substance? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.