ABSTRACT

The gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, beyond infection and fatality rates, can be seen across a range of broader social and economic issues including care overload, domestic violence, unemployment and job loss, and housing insecurity. On the whole, government public policy in response to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has not adequately addressed or prevented the inevitable gender impacts that have emerged. To what extent did governments have ‘early warning’ of these impacts? Using a matrix methodology to shine a light on a range of COVID-related gender impacts in Australia, this article indicates how the impact of the pandemic was exacerbated by already existing unequal gendered power relations. Our findings, identifiable in real time through news media reports, reveal that these debilitating effects extended to other social identifier groups (for instance, elderly, ethnic minorities, disabled) who were similarly caught up in underlying uneven power relations and structures.

Introduction

Ever since COVID-19 became public knowledge in early 2020, the lives of millions of people have been affected. However, there is strong evidence suggesting that the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 are different for different groups of people. In this paper we seek to place the spotlight on the disproportionate socio-economic impacts the first year of the pandemic had on women in Australia. It is most important to do so given that rapid research into the gendered impacts of pandemics and other health emergencies has historically been largely overlooked, often with detrimental effects on response and recovery, as shown by a multitude of studies examining gender inequality in the context of disasters and emergencies.Footnote1

The COVID-19 viral disease was first reported in January 2020 and was declared a pandemic by March 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO). It has spread across the world in successive waves leading to millions of deaths, long-term disability due to the disease, severe economic disruption, and the deepening of social crises. Men are over-represented in terms of fatality rates,Footnote2 however research on the impacts of COVID-19 reveals the negative social, economic and security impacts experienced by women as well as a number of other groups identified by their inter/intra group differences: LGBTQA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning), elderly people, people with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, homeless people, and ethnic minorities.Footnote3

Beyond illness and death, regionalFootnote4 and global comparative studies have provided a clearer picture of the generational impact that COVID-19 will have on progress in gender equality. Dang and Nguyen’s findings, based on research in six countries across three continents, reveal that women are 24% more likely to suffer permanent job losses.Footnote5 De Paz et al. have found that, overall, more women are exposed to the virus due to their presence in the health sectors and occupational sex-segregation.Footnote6 The long-term implications of this are unclear, but in the short term, Miyamoto discusses the impact of the disease on the predominantly female global healthcare workforce as including higher rates of stress, exhaustion and illness combined with additional caretaking responsibilities due to lockdowns.Footnote7

In addition to the financial and emotional effects,Footnote8 there have been documented increases in domestic violence levels and compromised access to sexual and reproductive health care.Footnote9 In Australia, research has revealed women are reportedly at higher risk of poorer mental health as a result of the pandemicFootnote10 and the pandemic has increased women’s vulnerability to all forms of gender-based violence.Footnote11 In Australia, childcare obligations have created a disproportionate effect on women.Footnote12 Internationally, based on an online cross-sectional study on the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain, Ausín et al. argue that women show more symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD than men.Footnote13 Similarly, García-Fernández et al. conducted a study that shows women experience higher levels of anxiety, stress and depression exacerbated by increasing levels of violence and loneliness.Footnote14 This resonates with a similar study conducted in China by Liu et al. and another study located in the UK.Footnote15

On the whole, the public policy of governments around the world in response to the crisis has not adequately prevented or addressed the gender gaps that have emerged in poverty, food security, safety, education, race, disability and reproductive health.Footnote16 Global research on gender and COVID-19 has suggested the need to critically examine what gendered, and other social group identifier impacts, were known at the earliest stages of the COVID-19 response.Footnote17 In the Australian case, to know what information was available to inform both federal and state governments’ responses in ‘real time’ we need to understand whose experiences were being documented and reported in the early stages of the pandemic. To investigate this further, we adopt a gender matrix analytical tool to examine real time knowledge about the gendered relations and environments affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and response within Australia.

This paper asks: ‘What was known, in real time, about the gendered impacts of COVID-19 in Australia?’ In the paper we apply a rapid gender matrix analysis during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia to collect, collate, analyse, and identify gender differences being reported in ‘real time’ in relation to the same experience.Footnote18 In this instance, due to the rapidity and unpredictability of the pandemic in the first year, the primary source material consists of open access news reports that analyse the gendered effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. The matrix methodology is reliant, primarily, on the news media content to identify the then-emerging conversations about who was most affected in the first year of the pandemic.

Our rapid gender matrix analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia confirms the collective global experience: that gender regression was being documented in real time. In Australia, due to the federal and state level public health responses to COVID-19, we identified more stories of women than men experiencing economic, social and security harm due to the lockdown. We also found that, as tempting as it might be to blame the pandemic for the unequal situations, the reports tend to identify intersecting inequalities that were present in most affected groups before the outbreak of COVID-19. In the reports, the populations identified most at risk of health care, economic, and security deprivations are those already identified as ‘vulnerable’ or ‘marginal’. This included not only women but also First Nations people, ethnic minorities, the elderly, and disabled. Our study of gendered impacts of COVID-related public health measures uncovers daily forms of discrimination, hence enabling us to gain more nuanced (and complete) understanding of the impacts of the pandemic, which included increased labour market inequality, escalating risks to women who are over-represented in the frontline healthcare workforce, social care systems breakdown, and heightened physical insecurity and safety risks. The pandemic did not cause but exacerbated well-entrenched gender and other social inequalities. In Australia, as elsewhere, the gender analysis matrix reveals that it was possible to identify harms to multiple populations in real time. Crucially, the matrix recorded little evidence of federal or state government intervention to prevent these harms during the same period. In this paper we first detail the logic and design of the gender analysis matrix methodology, then the data collection method, followed by the results of the matrix study. We then conclude with a discussion on the implications of our findings.

Matrix methodology: gender power relations in real time

Gender matrices are an analytical tool primarily used within international development studies and health systems analysis to rapidly inform and evaluate interventions.Footnote19 The gender matrix framework offers a structure for systematic gender analysis of the effects of any given event and/or intervention, including analysis of how gendered power relations manifest as inequalities or inequities, and the institutional structures that determine differential health, social, and economic outcomes.Footnote20

The gender matrix was originally designed as a practical tool to help identify and integrate gender impacts into policy.Footnote21 The value of the matrix is that it focuses on the interaction between social groups (gender but also ethnicity, homelessness, disability, elderly, etc.), impact areas (economic, health, social, cultural and political), and institutional location of impact—resources in finance, labour in the workplace, norms in the family, authorities such as police, laws in legislation. A crisis, a change of policy, or a new health service, requires understanding of the interaction between social group(s), impact area(s), and institutions(s).Footnote22 In the case of COVID-19, the pandemic is having different economic, social, political and security impacts on different social groups that require different institutional responses. Traditionally, the matrix data collection has been sourced from interview or survey respondents.Footnote23 However, prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, data collection was already evolving to accommodate digital harvest methods, conversation analysis, and open access reports in situations where it was too difficult or dangerous to conduct individual respondent surveys or interviews.Footnote24 In this paper, we used the gender analysis matrix to assess open access media sources reporting the real-world effects of political responses and government policy during COVID-19 response.

As noted above, the gender matrix recommends data collection on social groups beyond cisgender women and men categories. As such, we collected data on groups who identify or are identified by their intragroup differences to highlight the discreet but also intersecting ways in which inequality was experienced during the first wave of the pandemic, i.e. Asian women, elderly men, LGBTQA+ youth. The intersectional concept itself emerged from concern that focus on single inequalities, i.e. sex, would exclude other types of inequalities, i.e. race, as attested by the seminal 1989 work of Kimberlé Crenshaw.Footnote25 In feminist studies, as Carastathis notes, intersectionality ‘has become the predominant way of conceptualizing the relation between systems of oppression which construct our multiple identities and our social locations in hierarchies of power and privilege’.Footnote26

Our research paper investigates the public discussion of impacts (economic, social, political and security) identified as gendered (descriptions of behaviours, roles, concerns, and identities of individuals associated with sex, i.e. women and childcare) during the pandemic. To identify what was ‘known in real time’ we selected a source where there was public discussion (discourse) that was open access (public). Discourse, or ‘language in use’, needed to be a form of conversation. Media reports, editorials, and advocacy media briefing reports on voice, experiences, and situations in ‘real time’ are useful sources for matrix analysis in real time. We note that there is a need to be aware of the stereotypical gender representation and gender framing in such reports.Footnote27 Feminist discourse analysis suggests that awareness of these stereotypes actually requires the study of ‘conversations’ about gender from institutions like the media in order to analyse the ‘plural and competing discourses constituting power relations’.Footnote28 In this case, the pandemic was an inescapable impact. How the public was collectively experiencing and understanding its impact required access to an institutional source of public discourse that was rapidly reporting the impact of the pandemic on gender and intersecting social groups. In this paper we selected the media for our matrix data source.

Public discussion and representation of how different social groups were most affected, and the concerns they were expressing, was continually reconstructed during the first year of the crisis. The social relations and impact phenomena reported in the media and ‘grey literature’ is data that we could safely collect, in the place of interviews, surveys and focus group discussions.Footnote29 In a situation where there was uncertainty about the lockdown duration and understanding of the degree of intrusion it would have on different social groups, we turned to an open access news aggregate site as the most appropriate open data source to capture discussion about the impact of the pandemic on different social groups, with a particular focus on gender representation and experience. We selected Google News archive as our data source for two reasons. First, we wanted our search to be transparent and replicable; with the sources we use accessible to readers of this article.Footnote30 This is not possible for a subscriber-only news aggregate site such as Dow Jones Factiva. Second, we wanted a site that would capture how journalists, civil society, think tanks, advocacy groups, and public commentators were reporting lived experience during the pandemic. Google News aggregates articles from thousands of publishers and magazines, and was therefore a more suitable choice than alternative aggregate sites, for example LexisNexis Australia, to capture community level discourse and experiences.

Data collection

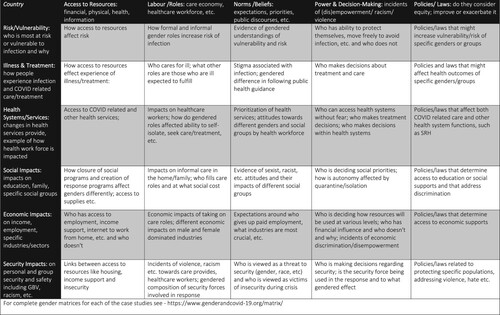

To identify and document the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic during Australia’s first year of the pandemic, we adopted the Smith et al.Footnote31 Gender and COVID-19 matrix used to compare gender power relations being reported in real time during their respective outbreaks in Canada, China, Hong Kong and United Kingdom (see ).

Table 1. Matrix search strategy.

In a similar way to that study, we sought to examine real time media reports in a single case (Australia) of gendered experiences (men, women, non-binary, and additional social stratifiers, i.e. race, homeless, elderly, disabled) documented during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, from 27 February 2020 (first recorded case) to 27 February 2021. A Google News Archive online search was conducted for the time period using keyword searches (see ).Footnote32 Each report was recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. The recording method required the two authors to independently review the reports and enter the data in the matrix. Then the matrices were compared and differences in recording were discussed iteratively and with reference to the JHPIEGO codebook.Footnote33

The first vertical column of the Gender and COVID-19 matrix provides six impact options (risk, illness, health service, social, economic and security). The first horizontal row provides five institutional locations of where impact is felt/occurring (access to resources, labour roles, norms and beliefs, power, institutions/laws [legislation]). The matrix provides 30 cells for entry—that is 30 different types of impacts and effects to study. Each report is entered in a cell that intersects, or corresponds, with both the gendered impact of the crisis (vertical) and location of impact (horizontal).Footnote34 The frequency of report entries in a cell, as well as the intersections of impact and location allow us to identify, for example, who is reported to be carrying out the majority of essential labour tasks in the community and how this is impacting on risk and vulnerability of infection. The matrix recorded 451 reports. All 30 cells were populated with reports and we provide a link to the matrix for readers to view.Footnote35 The average number of reports per cell was 11 with the highest being 25 reports under security (impact)/power. Each cell showcases a mix of cohorts. For example, the reports in the economic (impact)/institutions (laws) cell discussed the economic impact of the pandemic on women (20 reports), migrants (2 reports), the homeless (1 report) and (overall) the lack of government (federal or state) legislative response. Of the 23 reports, only 2 reports note legislation change in response to the pandemic (both reports were on the federal government JobKeeper social welfare scheme) ().

Table 2. Matrix search reports numbers.

Similar to the Smith et al. experience, our research question focused on real time knowledge of group experiences, but our findings revealed multiple intersecting factors shaping experiences of COVID-19. Using a multistep, iterative thematic analysis approach,Footnote36 the two authors reviewed the combined data to identify common themes. Thematic identification was a two-step process. First, the highest volume of entries was in the risk, economic, and security impacts, and these impacts most often intersected with resources, power, and institutions/laws. The second step was to map the conversation emerging between impact, institution, and gender. The two authors noted and compared the conversation themes they individually identified, then reviewed and refined through further discussion. Below, we present four primary themes most discussed in the matrix to illustrate the degree to which inequalities were being identified at the onset of the pandemic: labour market inequality between men and women (economic impact); an immediate care system breakdown for elderly and disabled populations during the COVID-19 pandemic which placed a disproportionate burden on carers (often women) (social impact); high representation of women in the healthcare sector which meant that they faced disproportionate risk and work-care imbalance (health impact); and highly gendered experiences of physical insecurity and safety for women but also ethnic minority groups (security impact).

Results: COVID-19 and gender in Australia

The matrix identifies and reveals patterns of wage, health, safety, care, and racial inequalities that existed prior to COVID-19, but the combination of public health measures that required people to stay in their homes of residence and socially distance resulted in mass loss of casual employment, and reduced access to health and social services. Despite the general occurrence of socio-economic harms due to the (necessary) public health measures to contain the spread of the virus, reports reveal that women were being disproportionately affected.

In this section, we discuss the content of some of the reports across the four primary themes that we have identified in our matrix as most commonly appearing at the intersection of impact and location: economic, social, health, and security. These four themes, and the stories reported within these themes, illustrate the degree to which it was possible to identify group vulnerabilities at the immediate onset of the pandemic.

Economic: labour market inequality

The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated already existing skewed power relations and gender-related dynamics that are fundamentally unjust. While Australia is an economically rich and democratically stable country, and it has largely escaped the mass casualties of COVID-19 that other countries have experienced, the public health response (a combination of containment measures or ‘lockdown’ restrictions and closures with testing and contact tracing) created unequal gendered stressors on the Australian population.Footnote37 Our research reveals that while women lost more jobs than men (5.3% to 3.9%),Footnote38 due to the gender pay gap—reportedly at just under 14%—the total wages paid to men have decreased more than those paid to females.Footnote39

According to Ryan Batchelor, ‘women entered this pandemic facing more precarious employment with higher rates of casual employment, lower pay, and higher levels of underemployment. Women across the labour market are being affected, and few appear to be immune’.Footnote40 Women are over-represented in part-time (and casual) employment, as well as dominant (56%) in those sectors hit hardest by the pandemic such as hospitality, travel, and entertainment,Footnote41 however by July 2020 there were reports of losses in the white-collar professional sector as well.Footnote42 The data confirms that young people in general are the group most devasted by the pandemic in terms of employment prospects, especially young females.Footnote43

Pandemic-heightened poverty was not restricted to women as the challenge of ‘putting food on the table’ extended to other social groups including people with disability, young people, elderly, and Indigenous Australians.Footnote44 Foodbank reported that demand for food relief was 47% higher in September 2020 than it was in pre-COVID times and in a separate report, the organisation noted the impact of panic buying on the elderly, the disabled and any other individual who was unable to go shopping on a regular basis.Footnote45

Construction and infrastructure projects dominated the recovery efforts, while little policy leverage was used to assist the many women who lost their jobs in other industries.Footnote46 Growing talk by the end of the data collection (end of 2020) pointed to Australia experiencing a ‘Pink Collar recession’ with figures showing consistency in displaying the gendered disadvantage to women in Australia’s economic recovery.Footnote47

As some reports noted, women lost more jobs than men and yet more men were receiving the JobKeeper subsidy due to eligibility rules: this reflects structural inequalities as well as an emphasis on supporting building and construction-related industries in the federal government-stimulated recovery effort.Footnote48 Data also reveals that refugees, asylum seekers, international students, temporary visa holders and casual workers without jobs or access to either JobKeeper or JobSeeker were negatively impacted by the pandemic.Footnote49 Federal government policy was also criticised in reports in relation to the ‘lagging’ paid parental leave scheme: a scheme that had not kept up with the affordability and wage standards of high-income countries and also one that the government did not adapt to pandemic circumstances, for example, with guaranteed funded placements in childcare during lockdown to assist with return to work after public health measures were lifted.Footnote50 Childcare itself is an industry dominated by female workers that could have collapsed at lockdown time, and even in post-lockdown times childcare workers might lose their jobs.Footnote51

Overall, the pandemic exacerbated problems that were already present for women and other social groups: financial insecurity, precarious employment, and depleted or no superannuation.Footnote52

Social: gendered norms and impacts

While women (especially those in low-income families) have always been burdened with more unpaid domestic work, since the occurrence of the pandemic this workload increased with the same or more household chores and added caring responsibilities including home schooling as schools and childcare centres were closed during various lockdowns.Footnote53 According to Cheng, ‘women are performing the majority of household duties, despite men and women both spending more time at home as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic’.Footnote54

The pandemic had little effect on the sharing of housework and childcare, with women still doing the lion’s share even by global standards: according to a report, Australian women do 311 min per day compared to the OECD female average of 263.4.Footnote55 Nevertheless, it seems that Australian fathers did increase their contribution to housework and childcare since the pandemic, reported as a possible window of opportunity to change established gendered practices.Footnote56 The provision of free childcare by the federal government during the first wave lockdown was reported as a welcome but temporary (three months) measure then replaced by a subsidy scheme contingent upon income levels, activities, and childcare cost, with reports that many women will have to reduce their hours or stop working altogether. Some reports focused on the lack of government action in addressing this issue. Ziwica noted that

It is not enough for Australia’s Minister for Women to very occasionally … acknowledge the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 on women, yet pursue, or endorse by way of complicit silence … a recovery agenda that either ignores or disadvantages women.Footnote57

The matrix revealed a number of negative effects of the pandemic within the LGBTQA+ community. A study undertaken at Melbourne University that found 61% of transgender people experienced clinically significant symptoms of depression and more than 11% reported feeling unsafe at home during the early days of the pandemic.Footnote58 It was also noted that there was a lack of adequate access to health services and specialised LGBTQA+ services, with the comment that the federal government’s mental health funding often overlooks this cohort.Footnote59 Other groups such as prisoners may not readily come to mind, but prisons in general were also deemed ‘the perfect breeding ground for COVID-19’, and specific more vulnerable groups inside those walls were at even higher risk, for example prisoners with disabilities and chronic health conditions.Footnote60

Health: gendered labour and access to care

As in many other countries women also constitute the majority of the healthcare workforceFootnote61 in Australia, which means that they are more exposed to disease and risk of transmission to their own families.

Reports tended to focus on healthcare workers’ risk of exposure, home care sacrifice, and abuse. Many healthcare workers temporarily removed themselves from their families to avoid infecting them with the virus, with at least one worker sleeping in her own garage.Footnote62 The risks to healthcare workers (including disability care workers) in the early stages of the pandemic were exacerbated by shortages of protective equipment, medical equipment like syringes, and medication.Footnote63

Medical staff, especially nurses, have been at continuous and even heightened risk of physical and verbal abuse since the pandemic began. Nurses and other medical staff were at one point in April 2020 told not to wear their scrubs outside the hospitals.Footnote64 Healthcare workers’ experience of racism featured strongly in our findings, where, for instance, a medical staff member of Asian appearance was told to stay away from a child she was treating by the child’s parents.Footnote65

The pressure and abuse took its toll on healthcare workers. According to a study by Mental Health Australia,

74% of healthcare professionals said restrictions resulting from COVID-19 outbreaks have had a negative impact on their mental health and wellbeing. Of the respondents, 86% said that working in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the amount of stress and pressure they experience in the workplace.Footnote66

Moreover, despite more women taking up careers as pharmacists, medical practitioners, midwives, nurses and laboratory workers, news reports revealed that they are still underrepresented in leadership roles and senior positions in these industries.Footnote68 This type of inequality was in turn reported as the underrepresentation of women in the COVID-19 response of governments at all levels of government as well as other sectors including academia and business.Footnote69 The lack of representation of women first response health care workers in the health industry—at the decision-making level and especially in various COVID-19 response leadership teams at federal and state governments’ levels—has clearly affected the flow of information to decision makers as well as individual safety.Footnote70

The pandemic also had a gendered effect on sexual and reproductive health care. Access to sexual and reproductive services was negatively impacted, due to the reallocation of resources in response to the current health crisis, thereby affecting services like safe abortions, contraceptives services, and clinical management of rape.Footnote71 The data from our matrix shows that organisations like Marie Stopes had to make a number of changes—for example, increasing the delivery of medical termination via telehealth and the closure of regional clinics in favour of a centralised model—in order to continue to deliver essential reproductive and sexual services.Footnote72 This organisation called on the federal government to commit more funds to sexual and reproductive care, in particular to make abortion an essential service and to increase access to virtual services in these areas.Footnote73

The COVID-19 pandemic also limited access to care for different social groups. Throughout the first year of reporting on the pandemic’s impacts, there were articles about the health risks faced by First Nation Indigenous peoples. Historically, the Indigenous populations are subject to a higher rate of infectious diseases and unequal health outcomes.Footnote74 In June 2020, the peak body for Aboriginal-controlled health services in the Northern Territory contested the Northern Territory government’s decision to reopen its borders to other states.Footnote75 Given the remoteness of some of the communities, the delivery of medical services in the event of a pandemic was reported as a serious challenge.Footnote76 The risk that COVID-19 especially posed to Indigenous populations revealed prior inequity of their health care determinants compared to the wider Australian population.

People with disabilities, already highly susceptible to contagious diseases, faced a number of social and economic discrimination issues related to lockdown: for instance, access to personal protective equipment (PPE), medication and health services, availability of healthcare workers and food shopping. Furthermore, figures suggest that by April 2021 only 6% of this cohort had been vaccinated.Footnote77 The federal government was criticised in a statement by the Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health as not doing enough to ensure disabled people are protected and considered.Footnote78 These health researchers also made a number of recommendations for disabled people and the healthcare workforce including access to testing and treatment for clients, setting up a committee of experts, protective equipment for healthcare workers, and paid time off for families and carers.Footnote79

Similar problems were reported in the already precarious aged care sector where, in a number of facilities, several deaths occurred within the first nine months of the pandemic.Footnote80 Our research found reports of elderly patients with COVID-19 being turned away from hospitals and being kept sedated in nursing homes.Footnote81 At one of the hearings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, Peter Rozen QC stated that: ‘68 per cent of all COVID-19 deaths in Australia relate to people in residential aged care; one of the highest rates of deaths in residential aged care as a percentage of total deaths in the world’.Footnote82 Finally, there were reports of elderly patients and carers feeling they had been discriminated against by healthcare professionals as well as individual experiences of the elderly being ‘written off like an old car’.Footnote83

Security: gendered experiences of safety

Physical safety was strongly associated with gender and other social identifiers (race, disability, and age) in the matrix reports.

First, the effect of COVID-19 discussed in real time pertains to an increase in domestic violence, due to heightened financial stress, increased consumption of alcohol, lockdown measures, and the ensuing social isolation.Footnote84 1800 RESPECT reported a 20% increase in the use of the online chat reporting tool between April 2019 and April 2020.Footnote85 Reports indicate that since the pandemic began, new and more complex forms of violence have been emerging with a corresponding increased complexity in women’s needs, as well as the reduced ability to seek and access help.Footnote86 Moreover, a larger proportion of women have been experiencing violence, both physical and sexual, for the first time.Footnote87

Another area related to domestic violence that was impacted by the pandemic was the relative lack of secure housing for women at risk.Footnote88 Precariousness for the homeless and other financially insecure people also increased, including renters on low wages who had been struggling despite some landlords reducing rents and a moratorium on evictions until September 2020 that was mandated by the federal government in March.Footnote89 Those living in overcrowded, inadequate and informal living arrangements faced a higher risk of exposure to the virus.Footnote90

Finally, existing group stratifiers like disability and race had further implications for women facing violence at home during lockdown. The Royal Commission into Disability (established prior to the pandemic) reportedly heard there was no federal government COVID-19 plan for the disability sector in April 2020, as well as a lack of consultation during the early stages of the pandemic.Footnote91 It came to light during a Commission hearing in 2020 that there had been an increase in violence against women with a disability during the pandemic, but no federal government response to address this harm.Footnote92 Another example of knowledge but no action involved reports of Aboriginal women being at risk of increased violence during lockdown measures, given the remoteness of some of the communities and the harmful impact of social distancing limits on the protective kinship relationships between women.Footnote93

Increases in racist behaviour were also reported as a social consequence of the pandemic. A survey conducted by Per Capita and the Asian Australian Alliance between April and June 2020 revealed that 35% of respondents with Asian appearance had been either physically or verbally abused; Footnote94 a survey of more than 3,000 people by ANUFootnote95 between January and October 2020 suggested the real figure was 84.5%.Footnote96

Discussion

The matrix included a column for the collection of reports that demonstrated how and when policy and legislation were adapting to the findings of negative impacts on the social groups studied in the matrix. Similar to the O’Keefe, Johnson and DaleyFootnote97 study, a striking feature of the matrix is that the affected groups’ experiences documented above are frequently ‘invisible’ in government policies, at both federal and state levels. Despite the reports of harm that people were experiencing there were few reports, with the exception of the Disability and Aged Care Royal Commissions, on the follow up response to news reports of these gendered and social impacts. The research also revealed little evidence of any level of government proactively seeking to consult with and include the experiences of marginalised or discriminated groups in the design of COVID-19 related policies to mitigate the economic, social, and security impact of these policies.

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were consistent and early reports of the economic, social, health, and security impacts on groups most affected. Often the impact on these groups was connected to their prior experience of discrimination, marginalisation or vulnerability. For example, women’s high representation in Australia’s health care workforce meant that they, and the health care sector, would experience high levels of work-care balance stress during the pandemic. In sum, this was predictable. Another example is women’s high representation in casual contract employment before the pandemic, which meant that they would be more likely to lose employment and income due to lockdowns and care obligations. These impacts were documented by government agencies like the Workplace Gender Equality Agency between May and June 2020.Footnote98 However, a gender informed analysis of the health emergency in March 2020, for example, might have predicted these impacts given the high representation of women in most affected workplace sectors and casual labour.

The matrix also revealed impacts specific to this pandemic that created new risks for social groups that required rapid response. Race and physical insecurity overlapped, for example, with Asian ethnic populations experiencing heightened racial attacks due to association of COVID-19 infection with Asian ethnicity. Persons with a disability and the elderly experienced immediate loss of access to social services due to the health risks faced by these populations, which limited their access to care, shops and services. The LGBTQA+ population were particularly affected by the lockdown measures which heightened some groups’ experiences of isolation and marginalisation.Footnote99 Despite these impacts being recorded in real time, public policy responses to these reports were muted at best and silent at worst.

Conclusion

What was known, in real time, about the gendered impacts of COVID-19 in Australia? The gender analysis matrix reveals it was possible to identify very early and throughout 2020 reports of inequalities being exacerbated by COVID-19. The pandemic escalated existing labour market inequality between men and women, a high representation of women in the healthcare sector meant that they faced disproportionate risk and work-care imbalance, there was an immediate care system breakdown for elderly and disabled populations during the COVID-19 pandemic which placed a disproportionate on carers (often women), and there were highly gendered experiences of physical insecurity and safety for women but also ethnic minority groups.

The recommendations from this study are twofold. First, there is a need to include the gender and social experiences of health emergencies in health emergency preparedness and response.Footnote100 Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, and in the early stages of this pandemic, there was little guidance on the prioritisation of collecting intersectional data and including gender expertise in the design of pandemic response.Footnote101 Group representation in infections and fatalities may not be the same as group representation in economic, social and security vulnerability during the emergency. A gender matrix analysis, in real time, affords those interested in public health compliance to identify the economic, health, social and security drivers that may determine which populations are able to adhere to public health directives.

In the Australian case, the second recommendation is to promote the design of intersectional response frameworks to emergencies that accommodate differentiated social risk and impact. Feminist and gender expertise is a form of knowledge and power that can improve emergency response.Footnote102 This knowledge needs to be recognised at the federal and state government level as expertise. When we look carefully at what was known in real time, a rapid gender matrix analysis points to uneven power relations and structures underpinned by discriminatory practices on the basis of factors including gender, race, age, sexuality and physical ability. This research reveals that it is possible for policy makers to rapidly identify—and address—the unequal and discriminatory political, social and economic impacts of this health emergency and other emergencies in the future.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the feedback and advice received from the project lead investigators Julia Smith, Simon Fraser University, Clare Wenham, London School of Economics and Rosemary Morgan, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sara E. Davies

Sara E. Davies is a Professor of International Relations, School of Government and International Relations, Griffith University, Australia. Sara’s research focuses on Global Health Governance and the Women, Peace and Security agenda. She is the author of Containing Contagion: Politics of Disease Surveillance in Southeast Asia (2019), Disease Diplomacy (2014, with Adam Kamradt-Scott and Simon Rushton), Global Politics of Health (2010), and Legitimising Rejection: International Refugee Law in Southeast Asia (2007).

Daniela di Piramo

Daniela di Piramo is a research assistant at the School of Government and International Relations, Griffith University, Australia. Her areas of expertise include gender studies, political philosophy and charismatic leadership. She is the author of Political Leadership in Zapatista Mexico: Marcos, Celebrity, and Charismatic Authority (2010).

Notes

1 Elaine Enarson and PG Dhar Chakraba (eds), Women, Gender and Disaster: Global Issues and Initiatives (Sage Publications 2009); Clare Wenham and Sara E Davies, ‘WHO Runs the World–(Not) Girls: Gender Neglect During Global Health Emergencies’ (2021) International Feminist Journal of Politics <https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2021.1921601>.

2 Carmen de Paz and others, ‘Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Policy Note, World Bank Group, 16 April 2020) <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33622/Gender-Dimensions-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y> accessed 8 July 2021; Catherine Gebhard and others, ‘Impact of Sex and Gender on COVID-19 Outcomes in Europe’ (2020) 11(1) Biology of Sex Differences 29; Inez Miyamoto, ‘Covid-19 Healthcare Workers: 70% Are Women’ (2020) 21 Security Nexus <https://apcss.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Security-nexus-COVID-19-Healthcare-Workers-miyamoto.pdf> accessed 8 July 2021; Paola Profeta, ‘Gender Equality and Public Policy during COVID-19’ (2020) 66(4) CESifo Economic Studies 365, 365; Clare Wenham, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan, ‘COVID-19: The Gendered Impacts of the Outbreak’ (2020) 395(10227) The Lancet 846, 846; Liam Mannix, ‘Men Are More Likely to Die from COVID-19 than Women. Why?’ The Sydney Morning Herald (22 April 2020) <www.smh.com.au/national/men-are-more-likely-to-die-from-covid-19-than-women-why-20200422-p54m8b.html> accessed 12 August 2021; Jenny Graves, ‘Coronavirus Kills Up to Twice as Many Men as Women and the Reason Is in Our Genes’ ABC News (21 April 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-21/coronavirus-kills-twice-as-many-men-as-women-chromosome-genes/12165794> accessed 8 July 2021.

3 Tali Kristal and Meir Yaish, ‘Does the Coronavirus Pandemic Level the Gender Inequality Curve? (It Doesn’t)’ (2020) 68 Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 100520; Sabine Oertelt-Prigione, ‘The Impact of Sex and Gender in the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Report, Brussels, European Commission May 2020) <https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4f419ffb-a0ca-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1/language-en> accessed 19 August 2021; Sonia Oreffice and Climent Quintana-Domeque, ‘Gender Inequality in COVID-19 Times: Evidence from UK Prolific Participants’ (GLO Discussion Paper No. 738, Global Labor Organization (GLO) 2020); Kristen D Krause, ‘Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBTQ Communities’ (2021) 27(1) Journal of Public Health Management and Practice S69; Francis Markham, Diane Smith and Frances Morphy (eds), ‘Indigenous Australians and the COVID-19 Crisis: Perspectives on Public Policy’ (2020) (Topical Issue 1) Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research <https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/202733/1/CAEPR_TI_no1_2020_Markham_Smith_Morphy.pdf> accessed 13 August 2021; Melissa McLeod and others, ‘COVID-19: We Must Not Forget About Indigenous Health and Equity’ (2020) 44(4) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 253; John P Salerno, Natasha D Williams, and Karina A Gattamorta, ‘LGBTQ Populations: Psychologically Vulnerable Communities in the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (2020) 12(S1) Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy S239; Aryati Yashadhana and others, ‘Indigenous Australians at Increased Risk of COVID-19 Due to Existing Health and Socioeconomic Inequities’ (2020) 1(10007) The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific 1.

4 Oertelt-Prigione (n 3); European Commission, ‘2021 Report on Gender Equality in the EU’ (Report, Brussels, European Union 2021) <https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/aid_development_cooperation_fundamental_rights/annual_report_ge_2021_en.pdf> accessed 19 August 2021.

5 Hai-Ahn H Dang and Cuong Viet Nguyen, ‘Gender Inequality During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Income, Expenditure, Savings, and Job Loss’ (2021) 140 World Development 1.

6 de Paz and others (n 2). See also Malte Reichelt, Kinga Makovi, and Anahit Sargsyan, ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Inequality in the Labor Market and Gender-Role Attitudes’ (2020) 23(S1) European Societies S228.

7 Miyamoto (n 2).

8 Sana Malik and Khansa Naeem, ‘Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women: Health, Livelihoods & Domestic Violence’ (Policy Review, Sustainable Development Policy Institute 8 May 2020); Richard Blundell and others, ‘COVID-19 and Inequalities’ (2020) 41(2) Fiscal Studies 291.

9 See Clare Wenham and others, ‘Women Are Most Affected by Pandemics—Lessons from Past Outbreaks’ (2020) 583 Nature 194; Amber Peterman and others, ‘Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children’ (April 2020) Working Paper 528, Center for Global Development <www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/pandemics-and-vawg-april2.pdf> accessed 28 August 2021.

10 Amy Dawel and others, ‘The Effect of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Representative Sample of Australian Adults’ (2020) 11 Frontiers in Psychiatry 1; Jane RW Fisher and others, ‘Mental Health of People in Australia in the First Month of COVID-19 Restrictions: A National Survey’ (2020) 213(10) Medical Journal of Australia 458, 462.

11 Naomi Pfitzner, Kate Fitz-Gibbon and Jacqui True, ‘Responding to the “Shadow Pandemic”: Practitioner Views on the Nature of and Responses to Violence Against Women in Victoria, Australia During the COVID-19 Restrictions’ (Report, Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre 2020).

12 Regan M Johnston, Anwar Mohammed, and Clifton Van der Linden, ‘Evidence of Exacerbated Gender Inequality in Child Care Obligations in Canada and Australia During the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (2020) 16(4) Politics & Gender 1131.

13 Berta Ausín and others, ‘Gender-Related Differences in the Psychological Impact of Confinement as a Consequence of COVID-19 in Spain’ (2021) 30(1) Journal of Gender Studies 29.

14 Lorena García-Fernández and others, ‘Gender Differences in Emotional Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Spain’ (2020) 11(1) Brain and Behavior 1.

15 Nianqi Liu and others, ‘Prevalence and Predictors of PTSS During COVID-19 Outbreak in China Hardest-Hit Areas: Gender Differences Matter’ (2020) 287 Psychiatry Research 112921; Oreffice and Quintana-Domeque (n 3).

16 See Ginette Azcona and others, ‘Will the Pandemic Derail Hard-Won Progress on Gender Equality?’ (UN Women 2020) <www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2020/Spotlight-on-gender-COVID-19-and-the-SDGs-en.pdf.> accessed 28 August 2021; Paola Profeta (n 3); United Nations Population Fund, ‘Covid-19: A Gender Lens. Protecting Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, and Promoting Gender Equality’ (Report, New York, March 2020) <www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_A_Gender_Lens_Guidance_Note.pdf> accessed 5 September 2021; United Nations, ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Women’ (Policy Brief, 9 April 2020) <www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf> accessed 28 August 2021; Wenham, Smith and Morgan (n 2); World Health Organization, ‘Gender and Covid-19’ (Advocacy Brief, 14 May 2020); de Paz and others (n 2).

17 ‘COVID-19: Emerging Gender Data and Why It Matters’ (UN Women, 26 June 2020); Lotus McDougal and others, ‘Strengthening Gender Measures and Data in the COVID-19 Era: An Urgent Need for Change’ (Report, 2020) <https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/Documents/COVID-19_Gender_Data_and_Measures_Evidence_Review.pdf> accessed 2 October 2021.

18 JHPIEGO (Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics), ‘Seven Steps to a Gender Analysis’ (John Hopkins University Affiliate, 21 March 2016) <https://gender.jhpiego.org/analysistoolkit/seven-steps-to-a-gender-analysis/> accessed 15 June 2021.

19 Rosemary Morgan and others, ‘How to Do (or Not to Do) … Gender Analysis in Health Systems Research’ (2016) 31(8) Health Policy and Planning 1069.

20 JHPIEGO (n 18).

21 Candida March, Ines Smyth, and Maitrayee Mukhopadhyay, A Guide to Gender-Analysis Frameworks (Oxfam February 1999) 22.

22 Morgan and others (n 19).

23 ibid.

24 Isadora Quay, ‘Rapid Gender Analysis and Its Use in Crises: From Zero to Fifty in Five Years’ (2019) 27(2) Gender and Development 221; Peterman and others (n 9).

25 Kimberlé Crenshaw, ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Anti-Discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics’ (1989) (1) University of Chicago Legal Forum 139.

26 Anna Carastathis, ‘The Concept of Intersectionality in Feminist Theory’ (2020) 9(5) Philosophy Compass 304, 304.

27 Karen Ross and Margie Comrie, ‘The Rules of the (Leadership) Game: Gender, Politics and News’ (2012) 13(8) Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 969; GK Sahu and Shah Alam, ‘Media Agenda on Gender Issues: Content Analysis of Two National Dailies’ (2013) 11(1) Pragyaan: Journal of Mass Communication 14.

28 Judith Baxter, Positioning Gender in Discourse: A Feminist Methodology (Palgrave Macmillan 2003) 8, 40.

29 Ian Hutchby, Media Talk: Conversation Analysis and the Study of Broadcasting (Open University Press 2005) 20.

30 Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F Klein, Data Feminism (MIT Press 2020) 125.

31 Jacqui Smith and others, ‘More Than a Public Health Crisis: A Feminist Political Economic Analysis of COVID-19’ (2021) 16(8–9) Global Public Health 1364.

32 On the use of Google News please note that it is a ‘news aggregator service developed by Google. It presents a continuous flow of links to articles organised from thousands of publishers and magazines’.

33 JHPIEGO (n 18).

34 See ; Morgan and others (n 19).

35 ‘Gender Matrix’ (Gender & COVID-19, 13 July 2020) <www.genderandcovid-19.org/matrix/> accessed 7 August 2021; Smith and others (n 31) 1368–70, 1380.

36 Greg Guest, Kathleen M MacQueen, and Emily E Namey, Applied Thematic Analysis (Sage 2012).

37 Giovanni Sotgiu and Claudia C Dobler, ‘Social Stigma in the Time of Coronavirus Disease 2019’ (2020) 56(2) The European Respiratory Journal <https://research.bond.edu.au/en/publications/social-stigma-in-the-time-of-coronavirus-disease-2019> accessed 23 October 2021.

38 David Richardson and Richard Dennis, ‘Gender Experiences during the COVID-19 Lockdown Women Lose from COVID-19, Men to Gain from Stimulus’ (Report, The Australian Institute, June 2020) 2.

39 Workplace Gender Equality Agency, ‘Gendered Impacts of COVID-19’ (Report, May 2020) 4; PAEC (Public Accounts and Estimates Committee), ‘Inquiry into the Victorian Government’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Interim Report, Parliament of Victoria, July 2020) 68.

40 Ryan Batchelor, ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Women and Work in Victoria’ (The McKell Institute, August 2020) <https://mckellinstitute.org.au/research/articles/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-and-work-in-victoria/> accessed 6 July 2021.

41 WGEA (n 39).

42 Batchelor (n 40); Workplace Gender Equality Agency, ‘COVID-19 and the Australian Workforce’ (Factsheet, August 2020); WGEA (n 39); Daniel Ziffer, ‘Coronavirus Pandemic Job Losses Shift from Youth in Hospitality to White-Collar Professionals’ ABC News (28 July 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-28/coronavirus-job-losses-shift-to-white-collar-professionals/12496724> accessed 7 July 2021.

43 Sarah Hill, ‘Lost Jobs and Missed Opportunities: How Young Women’s Financial Security and Careers Will Take a COVID-19 Hit’ Women’s Agenda (5 May 2020) <https://womensagenda.com.au/latest/lost-jobs-and-missed-opportunities-how-young-womens-financial-security-and-careers-will-take-a-covid-19-hit/> accessed 3 May 2021; Tom Stayner, ‘Young Australians Forced Out of Work by Coronavirus Face “Devastating” Long-Term Impacts’ SBS News (26 May 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/young-australians-forced-out-of-work-by-coronavirus-face-devastating-long-term-impacts/772f99b6-5e45-4752-bbdb-bed8012a7afd> accessed 4 May 2021; SBS News, ‘Coronavirus Pandemic Highlights “Stark” Inequalities Between Australian Workers, Think Tank Says’ SBS News (30 December 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/coronavirus-pandemic-highlights-stark-inequalities-between-australian-workers-think-tank-says/a5fb6190-6d53-4b01-8f4b-508b8207cc0c> accessed 4 May 2021.

44 Katherine Kent and others, ‘One in Four Tasmanians Experienced Food Shortages During the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Report No 15, The Tasmania Project, Institute for Social Change, 15 June 2020); The Catholic Leader, ‘Almost a Third of Australians Experience Food Insecurity in 2020’ The Catholic Leader (16 October 2020) <https://catholicleader.com.au/news/australia/almost-a-third-of-australians-experience-food-insecurity-in-2020/> accessed 22 June 2021.

45 Julia Kanapathippillai, ‘Foodbank Expects More Australians Will Face Food Insecurity’ Canberra Times (12 October 2020) <www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6965317/covid-19-worsens-food-insecurity/> accessed 21 June 2021; Emily Olle and Alex Chapman, ‘Coronavirus Toilet Paper Panic Buying Leaves Elderly Shopper Looking for the Basic Product’ 7 News (6 March 2020) <https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/coronavirus-toilet-paper-panic-buying-leaves-elderly-shopper-looking-for-the-basic-product-c-733092> accessed 21 June 2021; Jason Om, ‘Panic Buying Causing Serious Problems for Some of Australia’s Most Vulnerable People’ (7.30 Report, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 10 March 2020).

46 Richardson and Dennis (n 38).

47 Celina Ribeiro, ‘“Pink-collar Recession”: How the Covid-19 Crisis Could Set Back a Generation of Women’ The Guardian (24 May 2020) <www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/24/pink-collar-recession-how-the-covid-19-crisis-is-eroding-womens-economic-power> accessed 30 June 2021; Euan Black, ‘Pink-Collar Recession: Data Reveals Women Have Borne Brunt of Pandemic’ The New Daily (16 July 2020) <https://thenewdaily.com.au/finance/work/2020/07/16/pink-collar-recession-coronavirus/> accessed 30 June 2021; WGEA (n 39).

48 Greg Jericho, ‘Jobkeeper Has Failed, and It’s Hitting Women and Young People the Hardest’ The Guardian (21 June 2020) <www.theguardian.com/business/commentisfree/2020/jun/20/jobkeeper-has-failed-and-its-hitting-women-and-young-people-the-hardest> accessed 3 October 2021; Jessica Yun, ‘“Barely Any Jobs for Women”: The Gender Inequality of Morrison’s Stimulus Packages’ Yahoo Finance (10 June 2020) <https://au.finance.yahoo.com/news/coronavirus-women-retirement-225642479.html> accessed 7 October 2021; Richardson and Dennis (n 38).

49 Norman Herman, ‘COVID-19 to Impact Australian Refugees Without Access to Welfare’ (ABC Radio, 8 April 2020) <www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/am/covid-19-to-impact-australian-refugees-without-access-to-welfare/12131794> accessed 3 October 2021; Bethan Smoleniec and Maani Truu, ‘“No Excuse” not to Extend Jobkeeper to Temporary Migrants, Casuals after $60 Billion Bungle: Advocacy Groups’ SBS News (23 May 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/no-excuse-not-to-extend-jobkeeper-to-temporary-migrants-casuals-after-60-billion-bungle-advocacy-groups/0919712a-9f1b-4471-8a6e-8156350c150b> accessed 3 October 2021; Alice Moldovan and Erica Vowles, ‘Migrant Workers Call for Coronavirus Support amid Fears of “Crisis Situation”’ (ABC Radio National, 5 June 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-05/australia-migrant-workers-temporary-visa-holders-coronavirus/12301394> accessed 10 October 2021; Carrington Clarke, ‘Meet the Non-Residents and Casuals Who Can’t Get the Coronavirus Jobkeeper Wage Subsidy’ ABC News (2 April 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-02/coronavirus-wage-subsidy-jobkeeper-workers-who-cant-get-it/12114728> accessed 12 October 2021.

50 Emma Walsh, ‘Government Must Enable Pregnant Women to Access Extended & Flexible Parental Leave Provisions during this Crisis’ (Women’s Agenda, 1 April 2020) <https://womensagenda.com.au/life/jugglehood/government-must-enable-pregnant-women-to-access-extended-flexible-parental-leave-provisions-during-this-crisis/> accessed 2 October 2021.

51 See WGEA (n 39) 4; Claudia Farhart, ‘Women Fear They Will Have to Stop Working When Childcare Fees Return’ SBS News (9 June 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/women-fear-they-will-have-to-stop-working-when-childcare-fees-return/47240e70-5451-4288-bec6-0e242c2573e7> accessed 2 October 2021; Zoe McClure, ‘Universal Childcare a Key Pillar for Australia’s COVID-19 Recession Recovery’ (Women’s Electoral Lobby, 22 June 2020) <www.wel.org.au/universal_childcare_a_key_pillar_for_australia_s_covid_19_recession_recovery> accessed 12 October 2021; Lucy Dean, ‘“Double Whammy”: Jobkeeper Policy Tripping Up Women Twice’ Yahoo Finance (11 June 2020) <https://au.news.yahoo.com/childcare-decision-effect-on-aussie-women-013409639.html> accessed 23 September 2021.

52 WGEA (n 39); Trish Bergin, ‘Covid’s Toll on Women—Why Australia Needs a Gender Impact Statement’ (BroadAgenda, 4 August 2020) <www.broadagenda.com.au/2020/we-need-a-gender-lens-on-public-policy-more-than-ever/> accessed 23 September 2021.

53 Amy Cheng, ‘Women Shoulder Brunt of Household Work During Covid-19’ The South Sydney Herald (4 August 2020) <https://southsydneyherald.com.au/women-shoulder-brunt-of-household-work-during-covid-19/> accessed 2 October 2021; Emma Macdonald, ‘Gender Wars in the Time of COVID’ Her Canberra (26 June 2020) <https://hercanberra.com.au/life/family/gender-wars-in-the-time-of-covid/> accessed 2 October 2021; Kristine Ziwica, ‘Our Minister for Women is Missing on How the COVID-19 Crisis Is Disproportionately Impacting Women’ (Women’s Agenda, 11 August 2020) <https://womensagenda.com.au/latest/our-minister-for-women-is-missing-on-how-the-covid-19-crisis-is-disproportionately-impacting-women/> accessed 23 September 2021.

54 Cheng (n 53).

55 ‘Employment: Time Spent in Paid and Unpaid Work, by Sex’ (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development) <https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54757> accessed 5 January 2022; see also Lyn Craig, ‘COVID-19 Has Laid Bare How Much We Value Women’s Work, and How Little We Pay for It’ The Conversation (21 April 2020) <https://theconversation.com/covid-19-has-laid-bare-how-much-we-value-womens-work-and-how-little-we-pay-for-it-136042> accessed 22 October 2021.

56 WGEA (n 39) 3.

57 Ziwica (n 53).

58 Sav Zwickl and others, ‘The Impact of the First Three Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Australian Trans Community’ (2021) International Journal of Transgender Health <www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26895269.2021.1890659> accessed 22 November 2021.

59 Ben Nielsen, ‘LGBT Australians at Higher Risk of Depression, Suicide and Poor Access to Health Services During Coronavirus Pandemic’ ABC News (10 October 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-10/suicide-and-depression-among-lgbt-community-during-covid19/12743538> accessed 2 October 2021.

60 Luke Michael, ‘Prison is the “Perfect Breeding Ground” for COVID-19, Human Rights Groups Warn’ (Pro Bono Australia, 3 April 2020) <https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2020/04/prison-is-the-perfect-breeding-ground-for-covid-19-human-rights-groups-warn/> accessed 15 September 2021.

61 75.4%; see WGEA (n 39) 2.

62 Evelyn Lewin, ‘Risk of Infecting Others with COVID-19 Key Concern for Healthcare Workers’ RACGP (3 April 2020) <www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/risk-of-infecting-others-with-covid-19-a-key-conce> accessed 2 October 2021; Angus Thompson, ‘Healthcare Worker Sleeping in Her Garage to Avoid Family Contact’ The Sydney Morning Herald (31 March 2020) <www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/health-care-worker-sleeping-in-her-garage-to-avoid-family-contact-20200330-p54fei.html> accessed 2 October 2021.

63 Jessica Longbottom, Richard Willingham, and Rachel Clayton, ‘Victorian Coronavirus Healthcare Workers Not Getting Best PPE or More N95 Masks amid Shortage Fears’ ABC News (20 September 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-20/victorian-coronavirus-second-wave-fuelled-by-ppe-n95-shortages/12670226> accessed 5 October 2021; Anna Patty, ‘One in Five Doctors and Nurses Has Limited Access to Face Masks’ The Sydney Morning Herald (10 August 2020) <www.smh.com.au/national/one-in-five-doctors-and-nurses-have-limited-access-to-face-masks-20200809-p55jxx.html> accessed 7 October 2021.

64 Sarah-Jane Jones and Robert Cook, ‘Doctors and Nurses Already Face Routine Violence and Abuse—Coronavirus Could Make this Worse’ The Conversation (23 June 2020) <https://theconversation.com/doctors-and-nurses-already-face-routine-violence-and-abuse-coronavirus-could-make-this-worse-139167> accessed 9 November 2021; Kevin Nguyen, ‘NSW Nurses Told not Wear Scrubs Outside of Hospital Due to Abuse over Coronavirus Fears’ ABC News (5 April 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-05/nsw-nurses-midwives-abused-during-coronavirus-pandemic/12123216> accessed 9 November 2021.

65 ‘Coronavirus: Melbourne Health Workers of “Asian Appearance” Report Racial Abuse’ SBS News (27 February 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/coronavirus-melbourne-health-workers-of-asian-appearance-report-racial-abuse/1b1c524b-ec3f-44a5-a330-3891e91245a8> accessed 7 October 2021; ‘Coronavirus Fears Spark Racism Towards Hospital’s Doctors’ The New Daily (27 February 2020) <https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/state/vic/2020/02/27/coronavirus-racism-doctors/> accessed 8 October 2021.

66 ‘Happiness on the Horizon: Mental Health and Wellbeing of Healthcare Professionals Revealed’ (Media Release, Mental Health Australia 7 October 2021) <https://mhaustralia.org/sites/default/files/docs/mental_health_australia_media_release_-_7_oct_2021_-_mental_health_and_wellbeing_of_healthcare_professionals_revealed.pdf> accessed 9 January 2022.

67 ibid.

68 WGEA (n 39) 2.

69 ‘Women’s Leadership’ (Data Summary, Chief Executive Women 2020) <https://cew.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/CEW_Position-Policies_WomeninLeadership.pdf> accessed 5 January 2022.

70 Patty (n 63); Longbottom, Willingham, and Clayton (n 63); Jane L Whitelaw and Alicia Dennis, ‘PPE Unmasked: Why Health-Care Workers in Australia Are Inadequately Protected Against Coronavirus’ (University of Wollongong, 4 August 2020) <www.uow.edu.au/media/2020/ppe-unmasked-why-health-care-workers-in-australia-are-inadequately-protected-against-coronavirus.php> accessed 2 October 2021; Rachel Clayton, ‘Victorian Healthcare Workers Continue to Face Shortages of PPE as Coronavirus Cases Ramp Up’ ABC News (11 July 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-11/victorian-hospitals-and-aged-care-still-cannot-access-ppe/12445318> accessed 2 October 2021; Hannah Sinclair and Laura Francis, ‘Nurses and Other Healthcare Workers Open up About “Terror” of Catching Coronavirus’ ABC News (27 July 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-27/more-than-700-victorian-healthcare-workers-with-covid19/12494330> accessed 5 November 2021; Clay Lucas, Aisha Dow, and Melissa Cunningham, ‘Health Staff Want Automatic Workcover Rights, as New Mask Concerns Emerge’ The Age (18 August 2020) <www.theage.com.au/politics/victoria/health-staff-want-automatic-workcover-rights-as-new-mask-concerns-emerge-20200818-p55mvt.html> accessed 5 November 2021.

71 Erica Millar, ‘COVID Hurting Abortion Access Nationwide’ (La Trobe University, 12 May 2020) <www.latrobe.edu.au/news/articles/2020/opinion/covid-hurting-abortion-access-nationwide> accessed 10 October 2021; Dilvin Yasa, ‘From Abortion to Birth Control: How Coronavirus Is Affecting Your Reproductive Rights’ MSN (20 April 2020) <www.msn.com/en-au/health/medical/from-abortion-to-birth-control-how-coronavirus-is-affecting-your-reproductive-rights/ar-BB12T15V> accessed 10 October 2021.

72 ‘Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights in Australia’ (Situational Report, Marie Stopes Australia 16 August 2020) <https://resources.mariestopes.org.au/SRHRinAustralia.pdf> accessed 22 November 2021.

73 Ruby Prosser Scully, ‘Telehealth Restrictions “Jeopardise Sexual and Reproductive Health”’ (Medical Republic, 16 July 2020) <https://medicalrepublic.com.au/telehealth-restrictions-jeopardise-sexual-and-reproductive-health/31649> accessed 10 October 2021; See also Millar (n 71).

74 Yashadhana and others (n 3) 1; Jai McAllister, ‘Indigenous Leaders Warn “If Coronavirus Gets into Our Communities, We Are Gone”’ ABC News (20 March 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-20/dire-warning-on-coronavirus-for-indigenous-communities/12076420> accessed 5 January 2022.

75 Henry Zwartz, ‘Aboriginal Health Groups Fear New Coronavirus Outbreak as NT Government Plans to Reopen Borders’ ABC News (19 June 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-19/nt-borders-opening-indigenous-groups-coronavirus-concerns/12370018> accessed 10 October 2021.

76 Jessie Thompson, ‘COVID-19 Vaccinations for Remote and Vulnerable Indigenous Populations a “Massive Challenge” of Logistics’ ABC News (12 January 2021) <www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-12/covid-19-vaccinations-remote-vulnerable-indigenous-populations/13040334> accessed 22 November 2021.

77 Josh Butler, ‘“Unforgivable”: Only 6 Per Cent of Disability Residents Have Received Vaccines So Far’ The New Daily (21 April 2021) <https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/2021/04/21/vaccine-rollout-disability/> accessed 2 September 2021. See also Nicolas Perpitch, ‘The Coronavirus COVID-19 Outbreak Leaves People with Disabilities Among the Most at Risk’ ABC News (20 March 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-20/disability-sector-particularly-at-risk-of-coronavirus-impact/12068090> accessed 2 September 2021; Joel Magarey, ‘People with Disabilities Refused Exercise, Healthcare as Homes Take Coronavirus Rules Too Far’ The New Daily (18 May 2020) <https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/coronavirus/2020/05/18/coronavirus-care-home-rules-go-too-far/> accessed 10 October 2021; Ben Gauntlett, ‘Bringing a Disability Lens to the COVID-19 Health Policy Response’ (Australian Human Rights Commission, 5 May 2020) <https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/bringing-disability-lens-covid-19-health-policy-response> accessed 11 October 2021; Nas Campanella and Celina Edmonds, ‘COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout for Australians Living with Disability Needs Clarity, Experts Say’ ABC News (22 January 2021) <www.abc.net.au/news/2021-01-22/covid19-vaccine-rollout-people-living-with-disability/13078064> accessed 28 January 2022.

78 Anne Kavanagh and others, ‘COVID-19: Policy Action to Protect People with Disability in Australia’ (Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health, 24 March 2020) <https://credh.org.au/disability-and-health-sectors-need-a-coordinated-response-during-covid-19/> accessed 10 November 2021.

79 See also Helen Dickinson and Anne Kavanagh, ‘People with a Disability Are More Likely to Die from Coronavirus—But We Can Reduce This Risk’ (UNSW Newsroom, 27 March 2020) <https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/health/people-disability-are-more-likely-die-coronavirus-%E2%80%93-we-can-reduce-risk> accessed 10 November 2021.

80 Raina MacIntyre, ‘The Impact of PPE Shortages on Health Workers During the Covid19 Pandemic’ (UNSW Centre for Research Excellence Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response, 24 March 2020) <https://iser.med.unsw.edu.au/blog/impact-ppe-shortages-health-workers-during-covid19-pandemic> accessed 12 November 2021; SBS News, ‘Calls for Australia’s Disability Carers to Get the Same Coronavirus Protections as Aged Care Workers’ SBS News (8 April 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/calls-for-australia-s-disability-carers-to-get-the-same-coronavirus-protections-as-aged-care-workers/eb30cdd3-e010-4c2e-84ca-a56c25c95f95> accessed 10 November 2021; Caroline Egan, ‘PPE Shortages Aged Care’s Number One Concern’ (Hellocare, 3 April 2020) <https://hellocare.com.au/government-restricts-access-amid-ppe-shortages/> accessed 12 November 2021; Caroline Egan, ‘Australia Has One of the World’s Highest Rates of COVID Death in Nursing Homes, Royal Commission Hears’ (Hellocare, 10 August 2020) <https://hellocare.com.au/australia-one-worlds-highest-rates-covid-death-nursing-homes-royal-commission-hears/> accessed 8 October 2021; Jewel Topsfield, ‘Duty of Care: COVID-19’s Deadly Progress Through our Aged Homes’ The Age (1 August 2020) <www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/duty-of-care-covid-19-s-deadly-progress-through-our-aged-homes-20200731-p55h8i.html> accessed 10 November 2021; Sarah Russell, ‘Aged Care COVID Tragedy Was Years in the Making’ The Sydney Morning Herald (6 October 2020) <www.smh.com.au/national/aged-care-covid-tragedy-was-years-in-the-making-20201006-p562du.html> accessed 12 November 2021.

81 Neil Mitchell, ‘Victoria’s “Disposable People”: Aged Care Residents with COVID-19 Turned Away from Hospital’ (3AW, 12 August 2020) <www.3aw.com.au/victorias-disposable-people-aged-care-residents-with-covid-19-turned-away-from-hospitals/> accessed 12 November 2021; SBS News, ‘Aged Care Residents with Coronavirus Turned Away from Hospital, Providers Say’ SBS News (24 July 2020) <www.sbs.com.au/news/aged-care-residents-with-coronavirus-turned-away-from-hospital-providers-say/162160c5-f2a7-4b9e-88bd-706306f0ae85> accessed 12 November 2021.

82 Egan (n 80).

83 Jessie Davies, ‘Elderly Patients and Carers Say Age Discrimination in NSW Hospitals Is Real and Heartbreaking’ ABC News (16 August 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-16/ageism-in-health-doctors-biased-best-hospitals-for-the-elderly/12395292?nw=0&r=HtmlFragment> accessed 14 November 2021.

84 Hayley Boxall, Anthony Morgan, and Rick Brown, ‘The Prevalence of Domestic Violence among Women During the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Statistical Bulletin 28, Institute of Criminology, Australian Government July 2020); Luke Michael, ‘Fears COVID-19 Could Have a Long-Lasting Impact on Women’s Safety’ (Pro Bono Australia, 12 May 2020) <https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2020/05/fears-covid-19-could-have-a-long-lasting-impact-on-womens-safety/> accessed 10 October 2021.

85 Henry Zwartz, ‘Amid Coronavirus Lockdowns, Use of Online Domestic Violence Reporting Tool Spikes’ ABC News (23 May 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-23/coronavirus-lockdown-domestic-violence-spikes-in-australia/12238962> accessed 13 October 2021.

86 Pfitzner, Fitz-Gibbon and True (n 11); Michele Robinson, ‘Survey of Australian Women Shows Domestic Violence Has Escalated During Coronavirus Pandemic’ (ANROWS, 13 July 2020) <www.anrows.org.au/media-releases/survey-of-australian-women-shows-domestic-violence-has-escalated-during-coronavirus-pandemic/#:~:text=Two%20thirds%20(65.4%25)%20of,to%20the%20May%202020%20survey> accessed 20 October 2021.

87 Robinson (n 86); Safe and Equal, ‘COVID-19 and Family Violence’ (Safe and Equal, 29 April 2020) <https://safeandequal.org.au/working-in-family-violence/> accessed 20 October 2021.

88 Brad Cooper, ‘Housing Crisis Deepens for Women in Regional Queensland’ In QLD (21 May 2020) <https://inqld.com.au/news/2020/05/21/housing-crisis-deepens-for-women-in-regional-queensland/> accessed 26 September 2021.

89 Fergus Hunter, ‘Coronavirus Recession Risks Homelessness on a “Scale Unseen” Before’ The Sydney Morning Herald (31 August 2020) <www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/coronavirus-recession-risks-homelessness-on-a-scale-unseen-before-20200830-p55qmb.html> accessed 26 September 2021; Grace Tobin, ‘Renters in Arrears Fear an Eviction Backlash When Government Coronavirus Protections End’ ABC News (18 June 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-18/renters-facing-evictions-financial-squeeze-landlords/12370100> accessed 27 September 2021.

90 Nicole Gurran, Peter Phibbs, and Tess Lea, ‘Homelessness and Overcrowding Expose Us All to Coronavirus. Here’s What We Can Do to Stop the Spread’ The Conversation (24 March 2020) <https://theconversation.com/homelessness-and-overcrowding-expose-us-all-to-coronavirus-heres-what-we-can-do-to-stop-the-spread-134378> accessed 26 September 2021.

91 Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of Peoples with Disability, ‘Public Hearing 5: Experiences of People with Disability During the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic’ (Report, 26 November 2020) <https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-11/Report%20-%20Public%20hearing%205%20-%20Experiences%20of%20people%20with%20disability%20during%20the%20ongoing%20COVID-19%20pandemic.pdf> accessed 5 November 2021, 5.

92 Ursula Malone, ‘Government Coronavirus Plan Did Not Include People Living with Disability, Royal Commission Told’ ABC News (18 August 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-18/disability-royal-commission-to-shed-light-coronavirus-pandemic/12568436> accessed 5 November 2021.

93 Shawana Andrews, ‘At-Risk Aboriginal Women and Children Forgotten in Crisis’ (Pursuit, University of Melbourne, 21 April 2020) <https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/at-risk-aboriginal-women-and-children-forgotten-in-crisis> accessed 20 October 2021.

94 Asian Australian Alliance and Osmond Chiu, ‘COVID-19 Coronavirus Racism Incident Report: Reporting Racism Against Asians in Australia Arising Due to the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic’ (Report, Asian Australian Alliance 2020) <https://asianaustralianalliance.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COVID-19-racism-incident-report-preliminary.pdf> accessed 5 November 2021.

95 ‘Asian-Australians Hit Hard by the COVID-19 Pandemic’ (ANU Newsroom, 2 November 2020) <www.anu.edu.au/news/all-news/asian-australians-hit-hard-by-the-covid-19-pandemic> accessed 7 November 2021.

96 Jason Om, ‘Report Reveals Racist Abuse Experienced by Asian Australians During Coronavirus Pandemic’ ABC News (24 July 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-24/coronavirus-racism-report-reveals-asian-australians-abuse/12485734>; Max Walden, ‘More Than Eight in 10 Asian Australians Report Discrimination During Coronavirus Pandemic’ ABC News (2 November 2020) <www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-02/asian-australians-suffer-covid-19-discrimination-anu-survey/12834324> accessed 7 November 2021.

97 Patrick O’Keeffe, Belinda Johnson, and Kathryn Daley, ‘Continuing the Precedent: Financially Disadvantaging Young People in “Unprecedented” COVID-19 Times’ (2021) Australian Journal of Social Issues <https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.152>.

98 WGEA (n 42); WGEA (n 39).

99 Nielsen (n 59); Krause (n 3); Salerno and others (n 3).

100 Wenham and Davies (n 1).

101 ibid; see also World Health Organization (n 16) 1.

102 Johanna Bond, ‘Zika, Feminism, and the Failures of Health Policy’ (2016) 73 Washington and Lee Law Review Online 841.