ABSTRACT

In the decade following 2000, water management in the Canterbury region of Aotearoa New Zealand was characterised by irrigation expansion, agricultural intensification, and first-come-first-served water allocation. Some communities grew concerned about the impacts of intensive farming on water quality, river flows, and groundwater levels; others were concerned about a lack of meaningful reflection of Māori values in decision-making. In response, the Canterbury Water Management Strategy, published in 2009, promoted devolved collaborative governance of freshwater resources. A year later, regional councillors were dismissed by central government over concerns about water management and replaced by appointed commissioners through an Act of Parliament. The ensuing period of water management has been both praised and criticised. In this paper we examine water management in Canterbury through a case study in the Selwyn Waihora Zone. We use a causal framework to assess water management, focusing on the process that developed regulatory and non-regulatory recommendations and informed the Selwyn Waihora sub-regional section of the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan. We conclude that the collaborative process described is not a ‘quick-fix’ solution but a radical shift from previous approaches and, although it had some success, it might not be resilient to national political changes.

1. Introduction

Collaborative approaches to catchment-scale resource management have been a global theme in planning and environmental management literature over the past few decades (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Bell and Scott Citation2020; Bodin Citation2017; Sabatier et al. Citation2005; Scott, Thomas, and Magallanes Citation2019; Warner Citation2007; Weber Citation2003). This interest was mirrored, for a time, in Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu New Zealand (A-NZ) with a number of participatory and collaborative environmental decision-making processes undertaken (Cradock-Henry et al. Citation2017; Kirk et al. Citation2021; Lennox, Proctor, and Russell Citation2011), prompting a shift from consultation-based policymaking towards a more participatory and collaborative style (Eppel Citation2013; Fraussen and Halpin Citation2017; O’flynn and Wanna Citation2008). Against the tide of international experience, A-NZ is shifting away from its collaborative experiments of the 2000s (e.g. Hancock Citation2018), with no mention of collaboration in proposed resource management legislation (MFE Citation2021a). As another era in water management is heralded with increasingly directive national policies, this AJWR special issue offers the opportunity to reflect on collaborative water management.

Since 1991 freshwater use and allocation in A-NZ have been regulated by the Resource Management Act (RMA). The RMA’s purpose is to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources, ‘in a way, or at a rate, which enables people and communities to provide for their social, economic and cultural wellbeing’ (RMA Citation1991 [sec.5 (1)(2)]). This purpose was interpreted through evolving case law in the 1990s and 2000s. When this case study began the Courts had adopted an ‘overall broad judgment’ approach, whereby environmental values were balanced against economic, cultural, and social values (Skelton and Memon Citation2002). In 2014 the Supreme Court rejected the ‘overall broad judgment’ approach in favour of an ‘environmental bottom line’ approach (Kirk Citation2019). Under the RMA, A-NZ’s central government now establishes national standards and objectives for freshwater use, while regional governments set rules through regional policy statements and plans. National expectations for freshwater were established in 2011 through the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM) (MFE Citation2011), which required regional councils to set water quality and quantity limits. Subsequent versions of the NPS-FM (2014, 2017, 2020, see MFE Citation2020) have become increasingly prescriptive.

In Canterbury there were important precursors to the consideration of a collaborative approach. There was rapid intensification of land use (e.g. Forney and Stock Citation2014), facilitated by greater access to irrigation and increased water use efficiency (Cameron Citation2009; Kirk Citation2015a; Weber, Memon, and Painter Citation2011; Worrall Citation2007). The dairy herd grew by 305% between 1995 and 2009 (STatsNZ Citation1995, Citation2009). In the 2000s there were increasing concerns about declining groundwater levels and freshwater quantity and quality, typified by the (nation-wide) ‘dirty dairying’ campaign initiated by environmental non-governmental organisations and advocates (Dearnaley Citation2001). Conflict increased between farmers and environmentalists, with ‘adversarial’ and ‘lawyer-heavy’ consents and planning processes (Gorman Citation2009) leading to a hurting stalemate.

Against this backdrop was the reassertion of indigenous Māori as a partner in resource management issues. The Treaty of Waitangi 1840, as a foundation document, recognises Māori rights and enshrines ‘the expectations of iwi and hapū today’, including ‘an expectation of an equal partnership in collaborative planning and decision-making, guided by the principles of the Treaty’ (Sinner and Harmsworth Citation2015). The Treaty is therefore particularly relevant to contemporary collaborative planning and decision-making involving iwi and hapū, central and regional government. Greater recognition of Māori rights and interests hastened the introduction of co-governance arrangements, such as the Joint Management Plan 2005 between the Department of Conservation and Ngāi Tahu to jointly manage Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere, the first agreement of its kind in A-NZ (Memon and Kirk Citation2011). During the 2000s the recognition and role of Māori as partners in the development of land and water plans was still growing.

In the context of Canterbury’s water management, the ‘pride and prejudice’ era prior to changes about 2008 (Whitehouse, Pearce, and Mcfadden Citation2008) was typified by central and regional government engineers, scientists and planners determining what is important and relevant knowledge for local catchment management. During this era, adversarial science regarding groundwater zoning, water conservation orders, and freshwater conservation led to policy stalemates and antagonism between stakeholders and local government (Kirk Citation2015b; Weber, Memon, and Painter Citation2011).

The combination of these pressures with other factors such as poor or absent planning (Hughey Citation2001) and updates to the Local Government Act (Jenkins Citation2011) eventually prompted a different approach, and between 2002 and 2009 the Canterbury Water Management Strategy (CWMS) was developed (for a description of CWMS’ development, see Jenkins (Citation2018), 45–47). The CWMS attempted to mediate tensions around water management in Canterbury by, among other initiatives, adopting a collaborative approach to water management (CMF Citation2009). Across the region, zone committees were established and were guided by principles and targets of the CWMS that were devised through public consultation (Jenkins and Henley Citation2014). The CWMS proposed a balanced set of quantified outcomes in nine target areas (ten, after ‘Environmental Limits’ was added in 2010). As some outcomes would be difficult to achieve simultaneously, the CWMS also established priorities and primary principles (see ).

Table 1. Priorities and principles from the Canterbury Water Management Strategy (Canterbury Mayoral Forum 2009).

Shortly after the CWMS was released, a highly critical report reviewing the performance of the Canterbury Regional Council (otherwise known as Environment Canterbury, henceforth ECan) was published (Creech et al. Citation2010). The report advocated a complete restructuring of ECan’s freshwater management and governance functions. In response, Parliament passed the ECan (Temporary Commissioners and Improved Water Management) Act 2010. The Act replaced ECan’s councillors with appointed commissioners and granted commissioners new powers to enforce moratoria over freshwater consents, to amend or remove Water Conservation Orders in the region, and to restrict access to the Environment Court, a specialist court from 1996 for resource consent appeals and related issues, especially related to the RMA. The Temporary Act also instructed the commissioners to have regard to the Vision and Principles of the CWMS (Temporary Act, Article 63).

Between approximately 2008 and 2016 there was rapid change in the approach to water management in Canterbury. The CWMS exemplified the ‘sense and sensibility’ era whereby greater integration of community and Māori values in decision making ultimately led to the development of policies and implementation programmes which acknowledged, and endeavoured to respond to, different values and knowledge systems. In this paper we analyse one of the first zone committee-centred land and water planning processes, the Selwyn Waihora. After describing the case study area, we introduce the analytical framework that is used for the analysis, then evaluate the decision-making processes in the Selwyn Waihora using a framework of causal mechanisms that are linked to improved environmental outcomes (Jager et al. Citation2020; Newig et al. Citation2018).

In our title we intend ‘prejudice’, not so much in a pejorative sense, but in the dictionary definition of a preconceived opinion, or bias. And we intend ‘sensibility’ also in a dictionary sense of openness to a sensitive, not an emotionally detached, response to incoming information.

2. Case study description

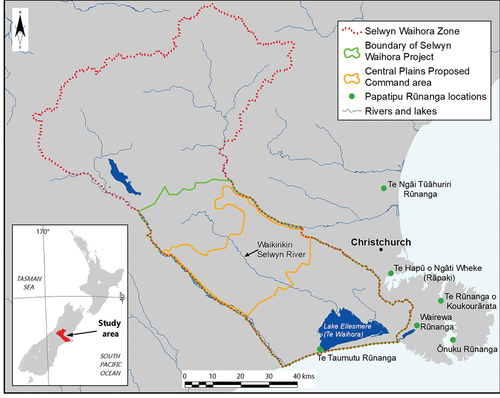

The Selwyn Waihora Zone is one of 10 devolved water management zones in Canterbury. The zone sits within the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu, with six papatipu rūnanga with interests in the zone. Rapid population growth is occurring in the zone, with 60,560 residents in 2018 compared to 46,700 in 2013 (StatsNZ Citation2021).

The case study (Selwyn Waihora Project) area covers the lower part of the zone (), covering the foothills and outwash gravel plains, and contains significant aquifers and surface water resources, such as the Waikirikiri Selwyn River and multiple lowland streams. When the SWZC formed, half the lowland streams did not meet the regulatory threshold for maximum algal cover, most streams did not meet the 80% biodiversity protection level for chronic nitrate toxicity, and the average concentration of nitrate in the groundwater was more than half of the maximum allowable value for nitrates in drinking water (ECan Citation2012; MoH Citation2018)

.The project area also contains Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere, a large (19,800 ha), shallow lake on the coast. Ngāi Tahu consider the lake a taonga for food and resource gathering, and it has very high conservation value, especially for birdlife (Waitangi Tribunal Citation1991), but it suffers from poor water quality (e.g. Hughey, Citation2007), and was classified as hypertrophic (ECan Citation2012), the highest Trophic Level Index classification.

Land-use intensification in the case study area has been enabled by freely draining soils, the climate, and access to water for irrigation. In 2010 almost a third of the district’s GDP came from agriculture, forestry, and fishing (ECan Citation2012). Canterbury has the largest irrigated land area in A-NZ (Rajanayaka, Donaggio, and McEwan Citation2010), reaching 478 000 ha in 2017. The Central Plains Water Scheme (CPW), the largest irrigation scheme in the case study area, applied for a consent to take water for an additional 30,000 ha of irrigation in 2008. The take was recommended after the hearings in 2010 (Milne et al. Citation2010) and was granted on resolution of appeals in 2012.

The Selwyn Waihora Zone Committee (SWZC) was established in 2010 to give effect to the collaborative approach to water management adopted in the CWMS. It is a joint committee of ECan, Christchurch City Council, and Selwyn District Council. Its initial Terms of Reference (CWMS Citation2013) were to:

facilitate community involvement in the development, implementation, review, and updating of a Zone Implementation Programme (ZIP) that gives effect to the Canterbury Water Management Strategy in the Selwyn-Waihora Zone; and

monitor progress of implementation of the ZIP.

When the SWZC was established in September 2010 there were six community members, two territorial authority appointees, a regional council appointee, and representatives from all six papatipu rūnanga (see ). One agency representative (ECan) was also from a rūnanga. Two community members were farmers, and two agency representatives (Selwyn District Council, Christchurch City Council) were farmers. One community member was a farm consultant; the remaining three had links to conservation groups. In total there were 15 members of the SWZC.

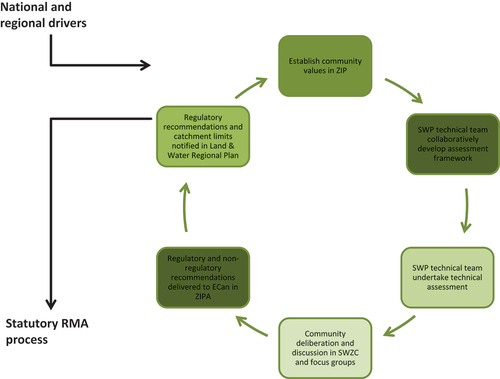

As its work programme developed the SWZC became closely involved with ECan planning staff in aligning the ZIP (SWZC Citation2012) with the preparation of the Selwyn Waihora sub-regional section of the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan (ECan Citation2016). The Selwyn Waihora Project (SWP) entailed the collaborative development of an agreed suite of regulatory outcomes and non-regulatory recommendations for a Zone Implementation Programme Addendum (ZIPA) (SWZC Citation2013). The process to develop these recommendations (see ) is the focus of this case study.

3. The analytical framework

A number of frameworks have been used to examine collaborative water management in Canterbury (Eppel Citation2015; Jenkins Citation2018; Lomax, Memon, and Painter Citation2010; Salmon Citation2012; Thomas Citation2014), although not specifically for the Selwyn Waihora Zone. In this paper, we use a recently developed analytical framework (Newig et al. Citation2018). This framework builds on previous research that helped identify some of the drivers, impacts, and adaptive responses of collaborative governance regimes (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015), as well as frameworks that describe what make collaborations ‘successful’ (Ansell and Gash Citation2008). However, the advantage of the Newig et al. (Citation2018) framework is that it causally links collaborative decision-making processes to environmental benefits. This is particularly useful where there are long environmental lag times, as in the case study area.

In 2007 Newig argued that it is ‘an open empirical question as to the extent to which participative processes actually contribute to an improved implementation of environmental policy and thus to a more sustainable usage of the environment’ (Newig Citation2007, 52). Evaluating the environmental impact of a collaborative process is rife with challenges, from methodological complexities in attributing certain outcomes to the decision-making process and the considerable temporal and spatial lags between interventions and results, to confounding factors of politics, policies or events that distort or influence the implementation (or lack thereof) of the results of the decision (e.g. Bammer Citation2013; Roux et al. Citation2010). Many of these challenges are present in the SWP.

In their 2018 paper Newig and colleagues sought to partially address these challenges through the development of a framework of causal mechanisms (Newig et al. Citation2018). They identify five clusters of causal mechanisms with concomitant features of participation and conditioning variables (). These mechanisms and their ability to achieve intermediate and ultimately environmental outcomes were tested empirically by Jager et al. (Citation2020). They analysed 305 participatory processes where particular aspects of decision-making processes were empirically linked to intermediate social or collaborative outcomes, and ultimately to environmental outcomes.

Table 2. Framework of causal mechanisms for the environmental performance of participatory and collaborative governance (source: Newig et al. Citation2018).

We consider the Newig et al. (Citation2018) framework to be suitable for an evaluation of the collaborative water management process in the SWP. However, there are caveats to this application. First, the framework refers to decision-making processes. Technically the SWZC made recommendations rather than decisions, but we consider their role commensurate with decision-making because there was an explicit, albeit unwritten, understanding on the part of the committee that, should they reach consensus, the recommendations would not be relitigated by ECan commissioners before going through RMA planning hearings (e.g. MfE Citation2017, 23). The second caveat is that, in A-NZ, relevant or appropriate environmental information must come both from science and from mātauranga Māori (A-NZ’s indigenous knowledge system) and is beyond the local and lay knowledge referred to in the framework (e.g. Broughton and McBreen, Citation2015; Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling Citation2013; Hudson and Russell Citation2009).

The analysis in the paper is structured using the five clusters of causal mechanisms proposed by Newig et al. (Citation2018). SWP is evaluated by examining the features of the participatory process (independent variables) and then reflecting on the results of the participatory process (dependent variables) and briefly examining the key internal and external conditioning variables found to be important to the decision-making process (see ). We conclude with an assessment of the implementation activities to date.

We adopted the case study approach promoted by Yin (Citation2009). Following Yin’s suggestions, we collected multiple sources of evidence to provide data triangulation and maintained a clear chain of evidence. We collected and analysed data in the form of grey and peer-reviewed documentation, archival records, previously published workshop and interview data from the SWP technical team and from next users of the technical material, including members of the SWZC, ECan policymakers and ECan planners (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021), as well as direct observations. Archival records included meeting minutes and reports published by the SWZC and the CWMS.

Direct observations were provided by two authors: one (DP) a member of the SWZC and one (MR-W) a member of the supporting technical team. Direct observations provide insights into events in real time. However, there are potential issues with the reliability, objectivity and reflexivity of observations, especially as time passes (Tellis Citation1997). These risks are mitigated by collecting direct observations from two observers and by comparing and contrasting these observations with collected documentation, interview data, and archival evidence.

4. Case study analysis

4.1. Opening up decision-making to environmental concerns

In their first cluster, Newig et al. (Citation2018) present two mechanisms by which environmental outcomes may be influenced: through providing access for environmental concerns to be heard, and through advocacy for environmental concerns. They argue that the enabling features of the process are to open up the decision-making group – in this case the SWZC – to include those people with environmental concerns, and through the representation of environmental concerns in the process. Although such access had been available through regulatory processes, e.g. the RMA since 1991, it was explicit and intentional in the CWMS/SWZC processes.

4.1.1. Access for environmental concerns

Environmental concerns were well represented in the SWZC membership, not least because the Māori world view is fundamentally environmental (Kawharu Citation2000). In addition to the six papatipu rūnanga representatives, three ‘community’ SWZC members were members (but not representatives) of environmental groups. The SWZC also elicited community aspirations for social, economic, cultural, and environmental well-being through consultation to define the priority outcomes for the area (SWZC Citation2012). Nine priority outcomes were agreed, based on targets and goals of the CWMS applicable in the SWP; of the seven used, six are partly or wholly environmental. These set the scope for the technical work and the criteria against which different future scenarios were assessed. Through this process the environmental impacts of current or future land uses were made transparent (Robson Citation2014).

All six community members were selected through a public invitation to participate, to balance geographic and skills aspects. Thus, the conditioning variables of targeted recruitment, balanced representation of stakeholders, and evidence of the environmental orientation were present in the SWZC

4.1.2. Advocacy for environmental concerns

As well as the scope of the assessment being largely environmental, the membership of the SWZC also influenced the information presented. Most often, this occurred when one or more SWZC members had insufficient understanding of the supporting technical or policy work. This happened a number of times in relation to cultural, environmental, and economic data, and in which the facilitation, a conditioning variable, had an important role in creating a safe place to collectively learn, but also to prevent simply more and more data being requested in lieu of making a decision. The facilitator was also key for bringing a range of perspectives from outside the SWZC to the table. Environmental groups such as Whitewater New Zealand expressed their concerns to the SWZC Committee meetings. The Department of Conservation also presented evidence to the committee. In addition, an 18-month- long community engagement ‘focus group’ process presented the results of SWP modelling to approximately 80 citizens, representing a range of community and commercial interests, in 11 focus groups. These focus groups allowed the SWZC to collect insights on the public acceptability of different potential scenarios prior to making recommendations.

The membership of the decision-making group, and the scope of the technical work being driven by community values, were a considerable shift from earlier ‘Pride and prejudice’ water management processes in Canterbury. These processes, such as the first two stages of the Canterbury Strategic Water Study, focused on quantifying how much irrigation could be developed in response to droughts in 1997 and 1998. The SWP illustrated a refocus from irrigation-focused policy development towards participatory, environmentally focused policy development (Kirk Citation2015a).

4.2. The incorporation of environmentally relevant knowledge

In their second cluster, Newig et al. (Citation2018) present four mechanisms: including lay and local environmental knowledge, education and empowerment of participants, providing a sound information basis for environmentally appropriate decision-making, and considering the implementability of decisions. They argue that the enabling features include the involvement of a variety of issue-related stakeholders and the provision of environmental and implementation knowledge.

4.2.1. Harnessing lay/local environmental knowledge for decision making

As previously stated, in A-NZ relevant or appropriate environmental information must come both from science and from mātauranga Māori. A year-long assessment of cultural health was conducted by local rūnanga representatives and co-ordinated by an expert in cultural health assessment, who also participated in the technical team and assessed scenarios against cultural values (Tipa Citation2014). In this way, appropriate methods were used to determine the impact on certain Māori cultural values. However, in the Māori world view, the way water is conceptualised as a treasure and intimately inter-related with people and their well-being (Durie Citation2012; Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling Citation2013) is very different from the ‘resource management’ (e.g. Wilson and Inkster Citation2018) framing that pervaded the SWP. On reflection, the design of the technical work for the SWP did not adequately reflect this world view.

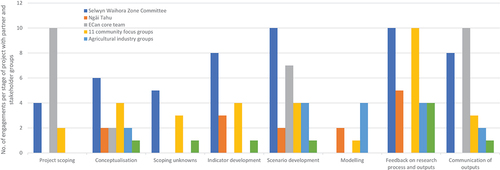

Lay and local knowledge and perspectives were also included. The technical team used the community-defined priority outcomes described in the ZIP, to determine the research scope, identify key knowledge sources, and determine indicators (Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020a; Robson Citation2014). They worked with the SWZC and the community to build ‘a conceptual understanding of how water and nutrients moved [in the case study area] which helped inform the modelling approach’ (Robson Citation2014, 9). The team also frequently sought and included input from multiple knowledge sources throughout the project (see ), satisfying the conditioning variable of structured knowledge integration and acknowledging that stakeholders and the SWZC had important expertise to contribute.

Figure 3. Number of technical team engagements (e.g. workshops, public meetings) between the SWP technical team, partners, and stakeholders for different project stages. (Reproduced from Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020a).

4.2.2. Education and empowerment of participants for more meaningful participation

In an ex-post examination of the Selwyn Waihora technical process, the next users of the technical work strongly agreed that their involvement in the process improved their knowledge of social, environmental, cultural, and economic interactions. They also indicated that the research process and outputs were ‘particularly useful for supporting them in policy or practice changes’ (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021, 13). The technical team tried to work so as to facilitate these interactions and had ‘various discussions with [SWZC] about how to best work together’. It was noted that the technical team was ‘re-structuring the way they undertook the science in explicit recognition of the need to recognise end-users’ needs and interests and values’ (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021, 13). The team paid particular attention to ensuring those providing support to the next users had ‘skills, attributes and interest in translation and communication, [were] non-defensive in their approach, had empathy with target audiences and were comfortable with uncertainty’ (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021, 13), all of which highlighted increased sensibility.

The technical team also made considerable efforts when synthesising information to minimise their own biases through collective discussion on what the science meant in relation to outcomes (Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020a) and aiming for evidence syntheses that were ‘inclusive; rigorous; transparent; and accessible’ (Donnelly et al. Citation2018). They ‘adopted a rigorous regime of getting as much information as possible in the public domain as quickly as they could’ (Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020b, 11) and delivered information at three levels of detail. These efforts were generally appreciated by the next users. also highlights the extensive community meetings including questions and answer sessions and public drop-ins to help stakeholders engage with the process and the information being produced. This suggested that the conditioning variables of clear understandable information and responding to knowledge deficits were present. Although no documentation of general trust levels in authorities was collected, trust was progressively built within the SWZC which included representatives of the regulatory agencies.

4.2.3. Sound information basis for environmentally appropriate decision making

A high degree of environmental knowledge was made available, with six out of seven priority outcomes assessed and 57 of the 83 indicators used being principally or wholly environmental (Robson Citation2014). In addition, the device of framing and displaying the modelling results in terms of likelihood of community outcomes being achieved was considered effective because it also communicated uncertainty (Duncan, Robson-Williams, and Edwards Citation2020; Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021). Other methods for managing uncertainty and creating a fit-for-purpose framework included: agreeing on a conceptual model, using best information at the time, collective interpretation of outputs, peer reviews, and the use of sensitivity analyses and scenario assessments (Robson Citation2014, 16).

There were two weaknesses in the provision of environmental information. First, climate change scenarios were not specifically included in the modelling, although the likely impacts were communicated narratively (Robson Citation2014, 5). Second, information generated from mātauranga Māori was used to populate a science-based conceptual framework, thus treating it as a source of knowledge rather than recognising it as a distinct knowledge system. We also note that the CWMS hierarchy () was not explicitly used in the technical work; in other words, results weren’t weighted to reflect priorities. That this was not done might have been construed as implicitly supporting a balancing exercise rather than reflecting the CWMS prioritisation.

The use of stakeholder values to determine the scope of the project and the support for the process of using a technical team to predict the likely impact of scenarios on values demonstrates a commitment to stakeholder interests and a recognition of the importance of knowledge as conditioning variables. In response to the conditioning variable about political will, we mentioned previously the there was an explicit, albeit unwritten, understanding that consensus recommendations would not be relitigated (MfE Citation2017, 23)

4.2.4. Knowledge fosters the implementability of decisions

The package of solutions designed and agreed by the SWZC is described in the ZIPA (SWZC Citation2013). On reflection there were some weaknesses in the way the recommendations were modelled. For some recommendations, such as lake- level control, having the interventions in place depended on further work and overcoming technical challenges. However, when these recommendations were modelled it was assumed the interventions were in place and so the difficulty of enacting some of the solutions was not explicitly considered in the technical assessment (Lilburne et al. Citation2021).

The implementation of recommendations was considered during its development and a commentary section described how the SWZC saw the recommendations working together to deliver outcomes. The recommendations involved multiple key parties regulatory and voluntary, industry and environment groups, thus fulfiling the conditioning variable of including all the important groups and charging participants with implementation activities.

Compared with previous water management approaches, the scope of what was considered relevant broadened significantly, although this also increased the uncertainties (Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020a; Robson Citation2017). Considerable effort was made to generate information that was credible, relevant, and legitimate (after Cash et al. Citation2003) for users, made uncertainties transparent and, notwithstanding the reservation about overcoming some technical challenges, embedded considerations about implementability. This contrasts with the approach taken in the ‘Pride and prejudice’ era of the early 2000s, when a ‘science impasse’ occurred after attempts to guide policy through science alone struggled to resolve the wicked problems associated with Selwyn’s water management (Weber, Memon, and Painter Citation2011). Some SWZC members, when reflecting on these past approaches, argued that ‘each group had their own facts, uncertainties, solutions and aspirations that never seemed to have been all tested together’ (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021, 11). Through the zone committee process there was significant investment in education and empowerment of members of the committee to understand the science, as well as the 18-month-long focus group engagement.

4.3. Group interaction, learning, and mutual benefits

In their third cluster, (Newig et al. Citation2018) present four mechanisms: negotiating and bargaining; group learning and innovation; deliberation; and consensus. They argue that intensive communication, open and interactive dialogue, and the use of deliberation are the enabling features for these mechanisms.

4.3.1. Negotiation and bargaining for mutual gains

Only a few SWZC members knew each other before joining the group in September 2010. There was a period when members got to know each other, which included sharing values and areas of interest and expertise. Facilitation, a conditioning variable, was important: the facilitator had to keep the group moving forward, while encouraging give-and-take and highlighting developing agreement. The chair had to ensure fair opportunity to speak, curb unproductive argument, and keep to reasonable time.

The provision of information in the SWP framed in terms of likelihood of different scenarios achieving community outcomes was a useful device for understanding trade-offs between different outcomes and as a basis for discussion and negotiation, and for highlighting situations where win-wins were possible. Another device employed was framing trade-offs as ‘gifting and gaining’ instead of winning and losing, thus giving power to the gifters as well as the gainers. Occasionally there was strong verbal disagreement between individuals or groups, but for the most part dialogue was respectful and mutually supportive. The relative stability of the group membership suggested that while challenging, the exit options of leaving were less preferable.

4.3.2. Group innovation and learning

At the beginning, very few of the non-Māori members understood mātauranga Māori and no members had specialist knowledge of economics. Across the SWZC members there was a good understanding of water management, farming, and some aspects of biophysical science. Members quickly acknowledged a deficit of relevant scientific and economic information. In September 2011 a group of scientists was invited to a workshop with SWZC members. Through key questions the workshop provided a learning opportunity for SWZC members to understand the fundamental science and state of knowledge of water issues in the zone before engaging publicly on the Zone Implementation Programme. The workshop proved useful, but insufficient. By early 2012 there was regular input to meetings by scientists, economists, and cultural experts from the technical team and beyond, responding to issues raised by SWZC members. This preparedness to learn new things and to grapple with unfamiliar concepts, especially in a complex problem space, was an important characteristic of the SWZC, as was their willingness to teach and to learn from each other. The collective learning went beyond the SWZC and was important for scientists and policymakers as well (e.g. Loucks Citation2021). The SWZC acted as mediator between scientists, researchers, and policymakers at ECan.

4.3.3. Deliberation

Newig et al. (Citation2018) favour a deliberative participatory process setting, characterised by what Emerson and Nabatchi (Citation2015, 62) call ‘candid and reasoned communication and information exchange that is structured and oriented towards problem solving’. The SWZC monthly meeting process met this criterion well. Meeting agendas were designed to: pick up threads from previous meetings, provide specific information, introduce new information for problem solving towards objectives, and encourage movement towards consensus. Guidance from both the chair and the facilitator aided these: after the initial settling-in period, exchanges were candid. Conditioning variables such as ‘protected space’, ‘trust building’, as well as ‘fair and transparent processes’ were well satisfied. Skilful facilitation, a conditioning variable in different parts of this framework, was a notable feature of SWZC meetings.

4.3.4. Consensus

With consensus strenuously pursued and facilitated, and with no interest group within the committee having an absolute majority, on the rare occasions when a contested vote was called for, the influence of ‘veto players’ (Newig et al. Citation2018) was slight. There were still ‘bottom lines’ debated (such as the protection of wāhi tapu/sacred sites for rūnanga representatives), but despite this, consensus could usually be achieved. Although there was conflict, the agreed community values as a basis widened the negotiation space for the SWZC to find an acceptable landing place.

The formation of the SWZC as a group, and the investment in learning and providing support for discussion and deliberation over a prolonged period, is a different model from those used by ECan in the ‘Pride and prejudice’ era prior to the development of collaborative governance (Jenkins Citation2017), whereby policies and rules were developed by staff relying on their existing knowledge and experience. The SWZC model introduced new knowledge into policy development. Brandt et al. (Citation2013) describe three kinds of knowledge needed for change: systems knowledge, target knowledge, and transformation knowledge. These can be broadly summarised as knowledge of the current system and the drivers of change; knowledge of what values are sought and what actions are plausible; and knowledge of how transformation can be encouraged and supported. In the SWZC there was significant investment in providing technical and planning support to committee members, meaning the members became more familiar with systems knowledge. Because community values were embedded into SWP assessment, the committee were uniquely placed to assess plausible future pathways. This contrasts with the science approach in the 1990s and 2000s, which was focused on filling knowledge gaps about the current system. The previous system was criticised for failing to consider all relevant values, something that began to be introduced through the CWMS (Kirk Citation2015a).

4.4. Acceptance and conflict resolution for implementation

In their fourth cluster, Newig et al. (Citation2018) present five mechanisms: accommodation of interest; procedural fairness; negotiation of mutual gains and conflict resolution for acceptance; waking sleeping dogs; and acceptance for implementation and compliance. They argue that the enabling features are stakeholder involvement, raised awareness, and power delegation, as well as a legitimate process that produces mutual gains, resolves conflicts, and is accepted by the community.

4.4.1. Accommodation of interest

The deliberative approach used by the SWZC and the use of community values to frame the results made the accommodation of different interests very clear. Beyond the SWZC, the SWP invested considerable time in meeting with multiple parties (), often over time to understand and consider the impacts of changes from different perspectives. This allowed important and affected groups to be involved with the process. In public and industry-facing meetings the SWZC were often the presenters, with technical and policy support, rather than the other way around. This built acceptance and ownership and recognised the participants as legitimate representatives, a conditioning variable. This mechanism also relies on the willingness of the authorities to consider the participants’ interest in the final decision. Although there was no guarantee because of the requirement to go through an RMA hearing process, as we mention previously, the commissioners had made clear early in the process that they intended to adopt the recommendations of the SWZC (MfE Citation2017). Also, ECan planning staff were developing the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan (ECan Citation2016) in parallel and in communication with the SWZC’s preparation of the Zone Implementation Programme (SWZC Citation2012) and Addendum (SWZC Citation2013).

Table 3. Record of formal engagements on policy development in the SWP.

4.4.2. Procedural fairness

In this mechanism, acceptance is built on the assumption that if participants believe that a process is fair and they trust it, they are more likely to accept it. In our case study early and meaningful engagement built this trust, and members of the SWZC interviewed largely agreed that the processes in the SWP were legitimate; however, they did note that legitimacy could have been built further by more successful engagement with the wider public (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021 unpublished data). For the public and those outside the SWZC, procedural fairness is reliant on transparency and accountability. A large amount of data was produced and made available to the general public. Paradoxically, this led to reduced perceived transparency for some stakeholders due to the sheer amount of information and insufficient information curation (Robson-Williams, Small, and Robson-Williams Citation2020b).

4.4.3. Negotiation of mutual gains and conflict resolution

In the SWP the SWZC was dealing with wicked problems that are very difficult to resolve. The conflicts that could be resolved were decisions on recommendations. The most notable example involved nitrate-nitrogen (nitrate-N) in water. Nitrate-N is a concern for both environmental and human health, and the main sources in an agriculturally intensive catchment are from cow urine patches (Monaghan et al. Citation2007). These losses increase with stocking rate, itself a function in Canterbury of the application of artificial nitrogenous fertilisers and access to reliable irrigation water.

The crux of the conflict about what restrictions to put on farm nitrate-N losses was the tension between environmental, cultural, and human health effects of excessive nitrate-N and the potential economic and social impacts from measures to reduce it. This tension was exacerbated by long lag times, with nitrates already lost from the root zone, but not yet detectable in waterways; poor public understanding of these lags; and inherent uncertainties in the estimates of losses and their transmission through the environment. The SWZC decided that good management practice on farms was insufficient as a first step, and that all farms needed to reduce nitrate losses to midway between good management practice and the maximum feasible mitigation on that land use. The social, cultural, economic, and environmental implications of this range (from good management practice to maximum feasible mitigation) were communicated and discussed, and external experts were brought in to present to the SWZC on specific elements of this debate. To resolve these conflicts, members debated whether the levels of restriction proposed would forego the possibility of achieving better future environmental outcomes. Given some constraints on decision-making, such as the presence of CPW, the SWZC pushed as far as they could, while recognising this was just a first step in addressing the long-term problems caused by diffuse nitrate pollution.

4.4.4. Waking sleeping dogs

‘Waking sleeping dogs’ often acts as a counter mechanism and suggests that raising stakeholders’ awareness of issues, and their involvement in decision-making, leads them to consider possible negative effects of decisions and increases opposition to environmentally beneficial measures.

Consideration of the full implications, positive and negative, of all scenarios was at the heart of the SWP. This approach made the decision-making harder because it was not possible to ignore the unpalatable aspects and may have enacted the mechanism of ‘waking sleeping dogs’, but it countered the conditioning variable of raising unrealistic expectations.

This mechanism also appears to have had a role in awakening the appetite of some groups to become involved. Once it became clear that the SWZC would be influential in setting policy and rules for water management in the zone, there was a sense in the SWZC that multiple new parties became keen to be involved, either directly or indirectly.

4.4.5. Acceptance for implementation and compliance

In 2013 the SWZC reached consensus and made their recommendations to ECan, the ‘policy addressee’ (Newig et al. Citation2018), in their ZIPA (SWZC Citation2013) and included insights on implementation in the commentary sections. Thus, acceptance by those involved was achieved. However, other factors such as politics, disagreements about how to implement, and changing circumstances may disrupt implementation (e.g. Beierle Citation2010). Implementation could also be affected by wider community acceptance, as well as acceptance by new members of the SWZC who were introduced in 2015.

We argue that the SWP process, through its extensive engagement, involved more stakeholders and involved them in the policy process more significantly than previous approaches, and met conditioning variables of ensuring access and early involvement of important groups. ECan’s Natural Resources Regional Plan, notified in 2004 and made operative in 2011 (ECan Citation2011), solicited public feedback in two stages, and proto-collaborative processes such as the Restorative Programme for Lowland Streams (ECan Citation2006) facilitated community engagement on stream restoration. Apart from these opportunities, the public had limited ability to contribute to water policy processes in the early 2000s. Thus, the SWP and the engagement processes represented a significant shift in Selwyn Waihora water management.

Despite greater engagement and awareness raising, there was still insufficient acceptance in some parts of the community against a backdrop of concerns over the imposition of commissioners and the ECan Act, which was viewed as having curtailed regional democracy (Sinner, Newton, and Duncan Citation2015). There is an irony here with respect to the environment. The commissioners replaced elected councillors in a distinctly ‘Pride and prejudice’, ‘top-down’ governance action, seen by many as anti-democratic. However, the ECan Act giving effect to the Vision and Principles of the CWMS resulted in a distinctly ‘Sense and sensibility’, ‘bottom-up’ decision-making process with more community participation than in previous development of policy by ECan and which, we argue, provided strong environmental outputs and discouraged significant land-use intensification beyond existing consents.

Representation has been another cause of reduced acceptance. Nissen (Citation2014) examined the representative claims of ex-ECan councillors, commissioners, and zone committee collaborators and noted how the sense of urgency that occurred after the introduction of commissioners reinforced notions that they were overriding or marginalising some interests. Zone committee members selected to represent ‘the public’ were asked to be explicitly non-representative; however, Nissen’s (Citation2014) research found they made a variety of claims to represent ‘farmers’, ‘the environment’, ‘Māori’, or ‘local communities’. Despite this contradiction, the inclusion of stakeholder interests through zone committee membership fostered perceptions of these processes being inclusive, at least to those who were directly involved (Nissen Citation2014).

4.5. Capacity building and implementation and compliance

In their fifth cluster Newig et al. (Citation2018) present two mechanisms: informing policy addresses and networks for implementation. They argue that the enabling features include early involvement of the policy addressees and collaborative deliberations.

4.5.1. Informing policy addressees

As noted above, ECan as ‘policy addressees’ was closely involved with the SWZC through: 1) representation on the committee; 2) having staff involved as the facilitator; 3) having planning staff contributing presentations to the committee concerning the parallel development of the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan (Citation2016); and 4) having science staff contributing presentations and reports to the committee, as required. Given this, there were close links between the collaboration and the agency ultimately issuing policy. This close connection also ensured that the conditioning variables of clear communications and relevance were met (Robson-Williams et al. Citation2021, 13).

4.5.2. Networks for implementation

Communication between groups and interested parties was frequent during the 2010 to 2016 period (). Networking, a conditioning variable, increased as parties recognised shared interests, new information sources, and ways of promoting their own and shared interests. Implementation and compliance under the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan (2016) was likely enhanced by the collaborative process leading to it, but made more difficult by the better understanding of the wicked problems involved.

Results of the SWP

To describe the results of the SWP, we divided Newig et al. (Citation2018) dependent variables into three types of results: the strength of the output, the acceptance of the output, and the implementation of the output.

4.5.3. Strong and innovative environmental outputs that considered implementation

The Solution Package proposed in the ZIPA is multi-faceted and more ambitious in scope, scale, and complexity than anything attempted in A-NZ previously (SWZC Citation2013). The ZIPA identified that a very significant work programme was required, along with strong leadership, to implement the recommendations. To assist with implementation, the ZIPA brought together regulatory and non-regulatory measures aimed at different issues in different parts of the catchment and different participants, as well as identifying measures that could be adopted immediately. Measures that were more contentious, or required more investment, were also included. Ultimately, the ZIPA adopted an integrated approach, recognising that all interventions and all impacts are inter-related, and that no one single action would resolve the catchment issues. The ZIPA also recognised a range of critical participants in successful implementation.

Of the 25 measures recommended in the ZIPA, 22 are aimed at environmental improvements. Given this focus, we consider the ZIPA to be a strong environmental output. However, critics might pinpoint measures regarding nitrates as a weakness (Pham, Lambie, and Taiuru Citation2019). Six measures in the ZIPA related specifically to nitrate-N, including the provision of a nitrogen load to the CPW for consented irrigation expansion. Taken together, the measures meant an overall increase in nitrate-N loads from a baseline of 2011 land use. However, the increase was approximately 50% of what it probably would have been without any constraints (see ). Given the existing water quality issues, critics may ponder why any increase was permitted at all. Under RMA case law, councils cannot place conditions on an existing consent that render it inoperable.

Table 4. Agricultural nitrate-N loads from Selwyn Waihora ZIPA.

Mindful of this, the SWZC needed to accommodate a nitrate-N load for the CPW in their considerations. However, they included multiple other recommendations that ultimately result in a predicted overall improvement in the environment in all but one area. Recommendations included a restricted amount of nitrate-N available to the CPW, an overall reduction in nitrate-N losses from all farms leaching above 15 kg N/ha, improved management for other contaminants, as well as in-stream and catchment-scale interventions such as building wetlands and in-lake measures. The SWZC also ‘piggy-backed’ several otherwise impracticable environmentally beneficial measures on to the CPW expansion, such as reducing groundwater abstraction for irrigation in the upper plains, thereby increasing lowland stream flows, and trialling targeted stream-flow augmentation (Painter Citation2018), several of which had been anticipated by the CPW hearings panel in their decision (Milne et al. Citation2010).

4.5.4. The acceptance of the output

Formal acceptance of the output occurred in three stages. Initially the SWZC achieved consensus in their recommendations (SWZC Citation2013). Then the ZIPA was formally received by ECan and Selwyn District Council in September 2013, and by the Christchurch City Council in October 2013. The councils noted that it was the basis for the Selwyn Waihora sub-regional section of the Land and Water Regional Plan and for design and realignment of work programmes. Further, the councils noted that ECan would work with Ngāi Tahu, Selwyn District Council, Christchurch City Council, government, industry, and other parties to identify and progress funding for the work programme to implement the recommendations (SWZC Citation2013). Finally, in the resource consent hearings that took place between September and November 2014 on the sub-regional section of the Land and Water Regional Plan, the hearing commissioners acknowledged the extensive collaborative process to reach the ZIPA. They noted that they made a ‘large number of amendments to the plan … nevertheless [the plan] retains a large part of the fundamental elements of the “Zone Committee Solutions Package”. Consequently, we have no reason to believe that Variation 1 does not still implement the CWMS’ (Sheppard, Solomon, and Van Voorthuysen Citation2015).

More broadly there were concerns about acceptance. The SWZC was trying to gain acceptance by accommodating the interests present in the whole community. Despite considerable efforts, there were reasons why this was not entirely successful: not all interested parties were directly represented on the SWZC; the direct engagement with stakeholders through meetings and media, although considerably more meaningful than previously, still only interacted with a fraction of the population; and some parties did not realise they were ‘interested’ until late in the process, when publicity about the possible impacts of implementation emerged.

In the absence of any comprehensive surveying of stakeholders it is difficult to establish either the variability of acceptance among groups or any bias in favour of or against the SWZC recommendations. However, individual perspectives have been published. For example, in a retrospective article, an elected ECan councillor, a former ECan commissioner, and a Māori cultural expert gave three perspectives on the successes and failures of the CWMS (Pham, Lambie, and Taiuru Citation2019). Most critical was the current ECan councillor, who argued that the CWMS process could not improve the environment because, as implemented, it is a continuation of business-as-usual practices. Most supportive was the ECan commissioner, who had a council governance role during much of the period covered by this paper. The commissioner argued that the process brought competing interests together, educated communities that there are serious problems with water quality and ecological health, and built greater understanding of what is needed and the time it would take to achieve meaningful change. Speaking specifically about the SWP, the commissioner argued that it was a ‘locally led process [which led to] very tough planning rules to significantly reduce nitrate leaching’ (Pham, Lambie, and Taiuru Citation2019, 40).

A report by the Cawthron Institute published in 2015 provided some preliminary findings on community engagement (Sinner, Newton, and Duncan Citation2015). The researchers found that in the Selwyn Waihora Zone, the general public felt that the collaborative process did not represent their concerns, that they had not received enough information about the process, and that there were insufficient opportunities to participate. Although the sample size of the Cawthron study was very limited, it highlighted concerns that some members of the public might not accept the SWP policies nor find them legitimate.

Some of these concerns were reflected in a central government review of ECan’s implementation of the NPS-FM (MfE Citation2017). They conducted panel discussions with ECan executives and appointed commissioners, senior ECan staff, members of multiple zone committees (including rūnanga and stakeholder representatives), some stakeholders who were not committee members, and representatives from national sector organisations. They found concerns from stakeholders about substituting a statutory process with a collaborative plan development process, although they acknowledged that collaboration had benefits in terms of working through issues before plan development. They also found that some representatives were concerned that communities would not understand or support decisions without having been present through the process. The report found that capacity and capability and the resources to participate in the zone committees are issues for nearly all stakeholder sectors and communities. They also noted a concern that ECan did not have enough economic information and is not accounting enough for socio-economic impacts.

On the positive side, they found that stakeholders and zone committee members and territorial authorities spoken to were largely positive about the approach that ECan had taken. Also, Ngāi Tahu representatives spoken to were supportive of the relationship and felt that the relationship with Ngāi Tahu enables the inclusion of mātauranga Māori. Learning and sharing across zone committees and members was noted, and the training in science communication was recognised and praised. ECan staff and commissioners credit the use of science as part of the collaborative process as a successful way to achieve better community engagement and understanding. The report noted that trialling the collaborative processes in the most challenging areas first thoroughly tested the process and demonstrated ECan’s commitment to its outcomes, and that ECan’s collaborative approach has empowered communities and encouraged better integration between regional and district plans (MfE Citation2017).

4.5.5. Implementation of the output

In April 2016 the SWZC set itself eight 5-year milestones, recognising that it would take a long time to see the impact of the recommendations. In December 2020 a progress report on the milestones was published (ECan Citation2020). One milestone was to reconstruct wetlands, restore macrophyte beds, and address legacy phosphorus issues in Lake Ellesmere/Te Waihora. No practical solutions to the legacy phosphorus issues have yet been identified. However, there has been some success in restoring wetlands, with the Ahuriri Lagoon wetland a highlight (MfE Citation2021b).

A second milestone was for farmers to perform at good management practice or better. All farms in the project area with greater than 15 kg N loss per hectare per year were subjected to audited farm environment plans (ECan Citation2020, 28) and required to make further reductions in nitrate-N loss beyond good management practice by 2022 (ECan Citation2020, 31–32). Over 2000 farms have been audited in Canterbury, with over 50% receiving an A grade (ECan Citation2020, 29), but in-depth information on what changes farmers have made as a result of farm environment plans is still forthcoming.

OverseerFM is a computer model widely used in New Zealand, including by ECan, to estimate nitrogen losses from farms, although it has recently faced criticism (MPI Citation2021; PCE Citation2018) over its accuracy. Given that a number of these concerns raised about the OverseerFM model are less likely to affect this catchment due to the soils and land uses, we present in some relative, indicative data (Overseer Citation2021) for modelled nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) losses across multiple farms in Canterbury for the period 2010–2020. The results show overall reduced N losses and a greater reduction in losses from dairy farms, suggesting, along with the audit results, that farm management changes are reducing environmental impacts. Modelled phosphorus losses also reduced from dairy farms.

Table 5. Overseer modelled N and P losses from farms in Canterbury 2010–2020.

Another milestone was to start stream augmentation trials, and so far these trials have shown potential to enhance the habitats of endangered Canterbury mudfish (Painter Citation2018). To respond to a milestone on the integration of Ngāi Tahu values across all outcomes, the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan established A-NZ’s first Cultural Landscape Values Management Area, encompassing Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere, its margins, and its tributaries (ECan Citation2020, 37). Beyond this, progress has been made through the establishment of the Te Waihora Co-Governance group, which incorporates Ngāi Tahu values, and through the funding of ecological restoration in the Whakaora Te Waihora programme (Te Waihora Co-Governance Citationn.d).

Work to enhance biodiversity and protect ecosystem health has been undertaken by a mix of regulatory and non-regulatory groups, confirming the SWZC’s assertion that ‘implementing the CWMS in the Selwyn Waihora Zone is a long-term commitment by many different parties’ (ECan Citation2020, 10). Examples of this work include $2.6 million of funding to plant 44 ha of wetlands (DoC Citation2021), and a farmer-led initiative that received $2.2 million of funding to plant riparian margins along 60 properties (NZ Government Citation2020).

A further milestone was that all community water supplies meet A-NZ drinking- water standards (MoH Citation2018). As of 2020, 54% of monitored drinking-water wells show increasing trends in nitrogen concentrations, with 29% showing a declining trend. One-fifth of wells show no clear trend (ECan Citation2020, 85). The SWZC also sought to increase recreation opportunities, such as swimming and fishing, at key spots. As of 2020, surface water-quality monitoring confirmed that cyanobacterial growth and E. coli concentrations continued to compromise the swimmability of several sites (ECan Citation2020, 77).

Finally, the SWZC sought to raise awareness of freshwater management goals within the community. Assessment of community awareness is difficult because no analyses have been conducted since the limited Cawthron Institute report in 2015 (Sinner, Newton, and Duncan Citation2015). Further research is required to confirm wider community awareness of freshwater management goals.

5. Conclusions

As water management in A-NZ shifts towards increasingly directive national policies, we reflect on the SWZC-centred land and water planning processes as an example of the collaborative water management experiment. To evaluate its performance, we describe the processes used in the case study through the causal mechanism framework developed by (Newig et al. Citation2018), which links aspects of decision-making processes to improved environmental outcomes.

In the title of the paper, we describe the change in approach to water management as shifting from ‘Pride and Prejudice’ towards ‘Sense and Sensibility’. We argue that compared to the previous era of water management in Canterbury, many aspects of the participatory decision-making process used in the SWP were mechanisms more likely to lead to improved environmental outcomes and have helped overcome an impasse. The decision-making process was considerably more open to environmental interests, both in the composition of the decision-making group and the greater sensitivity to different aspirations through scoping of the technical work using community values. The scoping approach also led to a greater incorporation of environmentally and locally relevant knowledge drawing on science, local knowledge, and mātauranga Māori. However it is acknowledged that, although mātauranga Māori was included as a source of knowledge, the science basis of the technical work did not reflect a Māori world view well.

The investment in group learning allowed the SWZC to be receptive to and accomodate multiple types of knowledges and, despite the challenges, the SWZC navigated conflicting views in a positive way to arrive at their consensus decision. There was general acceptance of the decision by those involved, by ECan, and through the hearings process. However, broader acceptance, especially relating to the substitution of the democratic governance process, was variable, and there was criticism that the environmental outputs did not go far enough and that insufficient attention was paid to the socio-economic impacts.

We argue that a strong environmental output was produced in the light of the pre-existing consented irrigation expansion. Implementation after 5 years indicated progress in many areas through a variety of funding mechanisms, including on-the-ground activities around biodiversity, wetlands, and stream augmentation. Although specific outcome data for the area isn’t available, farm plan auditing and modelling data indicate improvements in farm practice and reduction in on-farm nutrient losses.

Collaborative processes like the SWP cannot be regarded as a quick fix, and represent the first step rather than the final destination. However, they embody an approach that is radically different from those previously used in A-NZ for water management. They include many mechanisms likely to lead to positive environmental outcomes, suggesting that some key aspects of the collaborative planning experiment should not be forgotten in this new era of increasingly directive national water policies.

Authors’ Note

Jane Austen (1775-1817) wrote six novels about the everyday lives of the British upper class. Her first two novels were Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813). Already in 1816 Sir Walter Scott described her as a masterful exponent of the modern novel in the new realist tradition and her novels are still popular 200 years later.

In our title we intend ‘prejudice’, not so much in a pejorative sense, but in the dictionary definition of a preconceived opinion, or bias; this is sometimes evident in remote, top-down governance or management. And we intend ‘sensibility’ also in a dictionary sense of openness to a sensitive, not just an emotionally detached, response to incoming information; this is sometimes evident in collaborative, bottom-up decision-making. ‘Pride’ and (common) ‘sense’ have their usual meanings.

GLOSSARY of Acronyms and Te Reo Māori*

(* Most definitions adapted from Te Aka Māori Dictionary https://maoridictionary.co.nz/ by the authors.)

Acknowledgments

By their nature, collaborative processes involve many people working together. We acknowledge the good will and effort of many people we have worked with related to the Selwyn Waihora Project during and after the period described in this paper. The corrections and suggestions of two colleague reviewers and two journal reviewers improved the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Melissa Robson-Williams

Dr Melissa Robson-Williams works at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research as a senior researcher in environmental science and transdisciplinary research and manages the Integrated Land and Water Management research area. She specialises in managing the impacts of land use on water, science and policy interactions and the practice of integrative and transdisciplinary research.

David Painter

Dr Painter is a former research engineer, university academic and consulting engineer, now semi-retired. From 2010 to 2014 he was a community member of the Selwyn Waihora Zone Committee, and representative on the Regional Committee, of the Canterbury Water Management Strategy. He has carried out consultancy for hapū and iwi, as well as individual clients, central, regional and local government authorities, including Environment Canterbury.

Nicholas Kirk

Dr Nicholas Kirk is an Environmental Social Researcher at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. His research examines the governance of natural resources such as freshwater, fisheries, and invasive species. Dr Kirk’s research also investigates sustainability transitions in primary production as well as climate change adaptation.

References

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Bammer, G. 2013. Disciplining Interdisciplinarity: Integration and Implementation Sciences for Researching Complex Real-world Problems. Canberra: ANU E Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.22459/DI.01.2013.

- Beierle, T. C. 2010. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions. Washington DC: Routledge.

- Bell, E., and T. A. Scott. 2020. “Common Institutional Design, Divergent Results: A Comparative Case Study of Collaborative Governance Platforms for Regional Water Planning.” Environmental Science & Policy 111: 63–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.015.

- Bodin, Ö. 2017. “Collaborative Environmental Governance: Achieving Collective Action in Social-ecological Systems.” Science 357 (6352). doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan1114.

- Brandt, P., A. Ernst, F. Gralla, C. Luederitz, D. J. Lang, J. Newig, F. Reinert, D. J. Abson, and H Von Wehrden. 2013. “A Review of Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science.” Ecological Economics 92: 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.008.

- Broughton, D., K. Mcbreen, K McBreen, and (. Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu). 2015. “Matauranga Maori, tino rangatiratanga and the future of New Zealand science.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 45 (2): 83–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2015.1011171.

- Cameron, B. 2009. Liquid Gold: A Mid Canterbury Irrigation History. Canterbury: B. Cameron.

- Cash, D. W., W. C. Clark, F. Alcock, N. M. Dickson, N. Eckley, D. H. Guston, J. Jäger, and R. B. Mitchell. 2003. Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 8086–8091.

- CMF. 2009. Canterbury Water Management Strategy: Strategic framework–November 2009 with Updated Targets, Provisional July 2010. Christchurch, NZ: Canterbury Mayoral Forum.

- Cradock-Henry, N. A., S. Greenhalgh, P. Brown, and J. Sinner. 2017. “Factors Influencing Successful Collaboration for Freshwater Management in Aotearoa, New Zealand.” Ecology and Society 22 (2): 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09126-220214.

- Creech, W., M. Jenkins, G. Hill, and Low M. 2010. “Investigation of the Performance of Environment Canterbury under the Resource Management Act & Local Government Act.” Wellington: Ministry for the Environment and the Ministry of Local Government 5.

- CWMS. 2013. Selwyn Waihora Zone Water Management Committee Terms of Reference. Canterbury Water Management Strategy. Christchurch, New Zealand: Environment Canterbury.

- Dearnaley, M. 2001. “Milk versus Water: A Clash of Cultures.” NZ Herald, 11 June 2001.

- DoC. 2021. Jobs for Nature Projects Target Iconic Ecosystems. https://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2021-media-releases/jobs-for-nature-projects-target-iconic-ecosystems/. Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai. [Online]. [Accessed].

- Donnelly, C. A., I. Boyd, P. Campbell, C. Craig, P. Vallance, M. Walport, C. J. Whitty, E. Woods, and C. Wormald. 2018. Four Principles to Make Evidence Synthesis More Useful for Policy. London: Nature Publishing Group.

- Duncan, R., M. Robson-Williams, and S. Edwards. 2020. “A Close Examination of the Role and Needed Expertise of Brokers in Bridging and Building Science Policy Boundaries in Environmental Decision Making.” Palgrave Communications 6 (1): 64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0448-x.

- Durie, E. 2012. “Ancestral Laws of Māori: Continuities of Land, People and History.” In Huia histories of Māori: Ngā Tāhuhu Kōrero, edited by D. Keenan, 1–11. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia Publishers.

- ECan. 2006. Restorative Programme for Lowland Streams: Advisory Group Terms of Reference. Christchurch: Environment Canterbury.

- ECan. 2011. Natural Resources Regional Plan. In: Canterbury, E. (ed.). https://www.ecan.govt.nz/document/download?uri=2943531.

- ECan. 2012. Selwyn Waihora Limit Setting Process: An Overview of Current Status in 2012. Environment canterbury report R12/45.

- ECan. 2016. Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan. Environment Canterbury https://eplan.ecan.govt.nz/eplan/#.

- ECan. 2020. Report for the Selwyn Waihora Zone Committee: Reporting Progress in Implementing the Selwyn Waihora ZIP Addendum. Christchurch: Canterbury Regional Council, December 2020.

- Emerson, K., and T. Nabatchi. 2015. Collaborative Governance Regimes. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

- Eppel, E. 2013. Collaborative Governance Case Studies: The Land and Water Forum.

- Eppel, E. 2015. “Canterbury Water Management Strategy:‘a Better Way’?” Policy Quarterly 11(4).

- Forney, J., and P. V. Stock. 2014. “Conversion of Family Farms and Resilience in Southland, New Zealand.” The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 21: 7–29.

- Fraussen, B., and D. Halpin. 2017. “Think Tanks and Strategic Policy-making: The Contribution of Think Tanks to Policy Advisory Systems.” Policy Sciences 50 (1): 105–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9246-0.

- Gorman, P. 2009. Canterbury water. The Press, p.8. 27th April 2009.

- Government, N. 2020. Farmer-led Projects to Improve Water Health in Canterbury and Otago https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/farmer-led-projects-improve-water-health-canterbury-and-otago [Online]. [Accessed].

- Hancock, F. 2018. An Ambitious Freshwater Deadline. Newsroom [accessed 10 Jul 2020] Environment [3 screens]. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2018/10/08/269003/ambitiousfreshwater-deadline.

- Harmsworth, G., S. Awatere, and C. Pauling. 2013. “Using Matuaranga Maori to Inform Freshwater Management.” In Landcare Research Policy Brief, edited by L. Research, 7. Auckland, New Zealand: Landcare Research.

- Hudson, M. L., and K. Russell. 2009. “The Treaty of Waitangi and Research Ethics in Aotearoa.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 6 (1): 61–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9127-0.

- Hughey, K. 2001. Biggest Drought Comes in Ideas for Water Planning. Canterbury: Press.

- Hughey, K., Taylor, K, J, W, ed. 2007. Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere State of the Lake and Furure Management.

- Jager, N. W., J. Newig, E. Challies, and E. Kochskämper. 2020. “Pathways to Implementation: Evidence on How Participation in Environmental Governance Impacts on Environmental Outcomes.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (3): 383–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz034.

- Jenkins, B. 2011. Sustainability limits and governance options in Canterbury water management. In S. Russell, B. Frame, & J. Lennox(Eds.), Old Problems, New Solutions: Integrative Research Supporting Natural Resource Governance (pp. 50–58).Lincoln, Canterbury: Manaaki Whenua Press.

- Jenkins, B. Year. Evolution of Collaborative Governance in Canterbury Water Management. In: address to the XVI biennial IASC conference,‘Practicing the commons: self-governance, cooperation and institutional change’, Utrecht, 2017. 10–14.

- Jenkins, B. 2018. “Water Management in New Zealand’s Canterbury Region.” In Netherlands, 45–47. The Netherlands: Springer Publishing Company.

- Jenkins, B., and G. Henley. 2014. “Collaborative Management: Community Engagement as the Decision-making Process.” Australasian Journal of Natural Resources Law and Policy 17: 135–152.

- Kawharu, M. 2000. “Kaitiakitanga: A Maori Anthropological Perspective of the Maori Socio-environmental Ethic of Resource Management.” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 109: 349–370.

- Kirk, N. 2015a. Local Government Authority and Autonomy in Canterbury’s Freshwater Politics between 1989 and 2010. Doctoral dissertation, Lincoln University.

- Kirk, N. A. 2015b. Local Government Authority and Autonomy in Canterbury’s Freshwater Politics between 1989 and 2010. Lincoln: Lincoln University.

- Kirk, N. 2019. “Constrains on the Use of Adaptive Management in New Zealand’s Resource Management.” Case Studies in the Environment 3 (1): 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2019.002246.

- Kirk, N., M. Robson-Williams, G. Bammer, J. Foote, L. Butcher, N. Deans, G. Harmsworth, M. Hepi, L. Lilburne, and B. Nicholas. 2021. “Where to for Collaboration in Land and Water Policy Development in Aotearoa New Zealand? Guidance for Authorising Agencies.” Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online 17: 1–20.

- Lennox, J., W. Proctor, and S. Russell. 2011. “Structuring Stakeholder Participation in New Zealand’s Water Resource Governance.” Ecological Economics 70 (7): 1381–1394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.02.015.

- Lilburne, L., M. Robson-Williams, N. Norton, and P. Barbosa. 2021. “In Review. Improving Understanding and Management of Uncertainty in Science-informed Collaborative Policy Processes.” Submitted to Environmental Science and Policy 117: 25–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.12.002.

- Lomax, A., A. Memon, and B. D. Painter. 2010. The Canterbury Water Management Strategy as a Collaborative Planning Initiative: A Preliminary Assessment.

- Loucks, D. P. 2021. “Science Informed Policies for Managing Water.” Hydrology 8 (2): 66. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology8020066.

- Memon, P. A., and N. A. Kirk. 2011. “Maori 1 Commercial Fisheries Governance in Aotearoa 2/New Zealand within the Bounds of a Neoliberal Fisheries Management Regime.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 52 (1): 106–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.01437.x.

- MfE. 2011. National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

- MfE. 2017. National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management Implementation Review Canterbury – Waitaha. Report Published in August 217 by the Ministry for the Environment Manatū Mō Te Taiao.

- MfE. 2021a. Natural and Built Environments Bill: Parliamentary Paper on the Exposure Draft. https://environment.govt.nz/publications/natural-and-built-environments-bill-parliamentary-paper-on-the-exposure-draft/.

- MfE. 2021b. Restoring Ahuriri Lagoon. https://environment.govt.nz/what-you-can-do/stories/restoring-ahuriri-lagoon/ [Online]. [Accessed].