Abstract

This article examines how the architecture of international exhibitions stimulated sensations of moving through space and time. It conducts a detailed study of the principal structures of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888, the first in a series of highly successful events mounted in the so-called “second city of the empire.” Through analysing pictorial representations and textual descriptions, it reconstructs the exhibition’s physical environment and atmosphere, which were perceived as “oriental” in character by contemporary commentators, in order to probe how the architecture of international exhibitions helped render these events sites of imperial meaning-making. Following an interdisciplinary approach informed by architectural and design history, postcolonial analyses of the relationship between nation and empire, and critical museology, it frames the international exhibition as a ritual site and argues that exhibition architecture played a key role in producing a liminal experience for visitors.

An article published in The Times in February 1850 predicted that the Great Exhibition, which was billed as an exhibition of the works of industry of all nations, would transform London into “the hospitable rendezvous of the world.”1 Revealing a determination to showcase the world in miniature, this comment points to an elemental feature of international exhibitions, one that differentiated these spectacles from other nineteenth-century spaces of display. As Bennett explains, international exhibitions “sought to make the whole world, past and present, metonymically available in the assemblages of objects and peoples they brought together.”2 These events were places where successive generations of spectators observed, compared and surveyed cultures and societies they were otherwise unlikely to have a direct encounter with. Displays of natural resources, foodstuffs, manufactured goods, cultural artefacts, and human participants from all over the world coalesced to advance notions of travel and escape, making the international exhibition a form of virtual tourism.3 The constructed worlds that were on show, however, were not necessarily as unfamiliar as they were framed as being, because they both drew from and reinforced imperial images, stereotypes and tropes that became increasingly embedded in British metropolitan popular culture over the course of the nineteenth century. As Hall and Rose explain in the opening chapter of their edited volume At Home with Empire, an imperial presence infused the everyday lives of ordinary Britons to such an extent that “empire mattered to British metropolitan life and history in both very ordinary and supremely significant ways: it was simply a part of life.”4

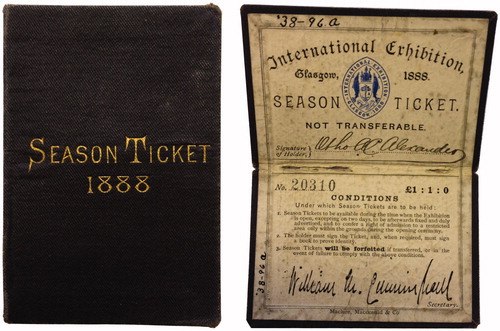

The notion that international exhibitions fostered narratives of travel and thus functioned as sites of virtual tourism is perhaps best captured in what at first glance seems an unremarkable piece of ephemera. Entry tickets like the season pass reproduced here () are what gave spectators access to the other-worldly environment of the international exhibition. While each event had its own unique design, there were recurring formal and aesthetic characteristics. Smaller than pocket-sized, season tickets were folded pieces of card covered in dark-coloured cloth, frequently blue or red, that bore the title of the exhibition in gold lettering on the front cover. On the inside were the rules and regulations that conditioned the ticket’s use alongside the name, signature and address of its holder.5 Such objects bear a strong resemblance to a miniature passport, highly appropriate given they embodied a freedom of movement and passage and enabled the crossing of thresholds, both real and imagined.6 The particular example shown in was produced for use at the first Glasgow International Exhibition, which inaugurated a series of highly successful spectacles mounted in the city between 1888 and 1938. Subsequently adapted for each iteration, the season ticket became a quintessential memento of a day-out spent enjoying the sights, smells and sounds of Glasgow’s exhibitions. Facilitating entry into another world, the season ticket is an element of the material culture of international exhibitions that helped construct the illusion that a visit was akin to an act of travel.

Figure 1. Season ticket for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888, A.1938.96.a. Reproduced courtesy of Glasgow Museums.

If the season ticket secured the visitor’s passage, what did the individual encounter on the other side of the turnstile? In what environment did spectators find themselves immersed? This article considers these questions through a detailed study of the architecture and built environment of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888, which was held in a large landscaped public park in an area of the city known as the West End. Through examining pictorial representations and textual descriptions, the environment and atmosphere of this event will be reconstructed in order to probe how the architecture of international exhibitions engendered imaginings of travel set against an imperial backdrop. Drawing on architectural and design history, postcolonial analyses of the relationship between nation and empire, and critical museology, it frames the international exhibition as a ritual site and argues that exhibition architecture played an essential role in effecting a liminal experience among audiences.7

As exemplified by the quotation from Bennett’s essay on the exhibitionary complex cited above, much of the existing scholarship on the liminal, touristic and voyeuristic nature of international exhibitions attends primarily to the presence of foreign objects and people.8 Moving away from the contents of international exhibitions this article focuses instead on the container, the physical structures that formed and manipulated exhibitionary space.9 This approach is not only a response to the lay of the current scholarly landscape, but also takes its cue from contemporary sources which reveal that the principal buildings of an international exhibition, as well as the planned surroundings and wider setting, were recognised as items of fascination in their own right and as deserving of audience attention as the objects they contained. Before an architectural plan for the Great Exhibition had been decided upon, for instance, the Illustrated London News advocated that the custom-built structure ought to be “the most singular and peculiar feature of the Exhibition.”10 This set an important precedent, whereby the buildings of an exhibition were more than cavernous spaces ready to be filled with countless objects. In its construction methods and materials, size and proportions, style and ornamentation, the architecture of an international exhibition was used to convey meaning. Captivating, fanciful and yet more often than not purely temporary, exhibition architecture organised space in deliberate ways and was evidently an attraction in and of itself.

Glasgow figures here as a significant producer of exhibitions. This subject has received minimal critical attention despite the fact that within a fifty-year period the city hosted four of the largest, best-attended and most profitable exhibitions ever mounted in Britain, making it a conspicuous lacuna within the extant literature.11 A description of Glasgow penned on the occasion of its second International Exhibition, held in 1901, advocated that life in the “Second City of the Empire … move[d] to the resonance of a clanging rhythm, and fire and steam appear[ed] in almost elemental power.”12 This account not only encapsulates the hand-in-glove relationship that existed between industry and empire in the Victorian period, but crucially also situates Glasgow as a city where the links between these two endeavours were especially palpable. Indeed, the city’s economy, which was bound up in imperial networks, supplied the funds that built its first international exhibition, the opening of which saw Glasgow “invite her neighbours from far and near to inspect the net product of Scottish brains and Scottish hands, the finished result of capital, labour, patience, skill and ‘canniness’ in combination.”13 Glasgow’s record of exhibition-making therefore exemplifies Greenhalgh’s assertion that international exhibitions were the “extraordinary cultural spawn of industry and empire.”14 Furthermore, exploring Glasgow’s contribution to the international exhibition movement signals not only a shift beyond well-known, canonical examples of this exhibition type, but also a response to MacKenzie and Devine’s invitation to consider a British imperial history attentive to the empire’s constituent parts, including British regions beyond England (and London in particular).15

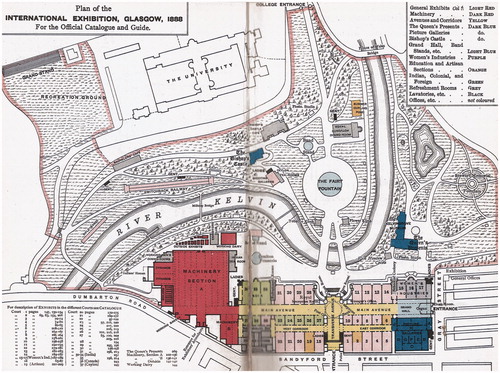

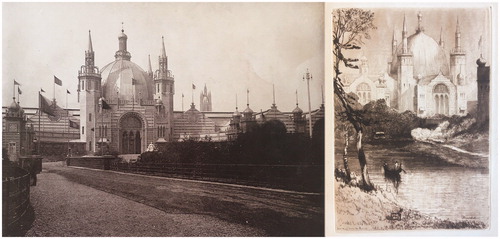

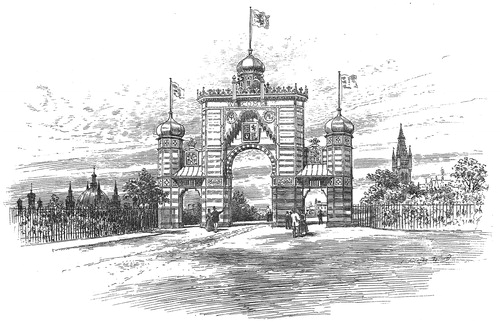

The Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 was erected in the southern portion of Kelvingrove Park, a large public park that had been laid out by municipal authorities some 30 years earlier. In March 1887, the Scottish architect James Sellars, partner in the Glasgow-based practice Campbell Douglas & Sellars, was awarded the commission to design the exhibition’s site and principal buildings. Titled “The Bishop’s Palace,” Sellars’ scheme centred on a large wood, brick and plaster building accompanied by various ancillary structures and attractions. As shows, the exhibition’s Main Building was rectangular in plan, its longitudinal elevations facing Sandyford Street in the south and Kelvingrove Park in the north. Contemporary accounts claimed the simplicity of the building’s footprint created a clear and logical internal space that allowed visitors to see the array of exhibits contained within to the best advantage, “not chaos-like together crushed and bruis’d.”16 Laid out on a single level, the internal volume was divided longitudinally by the Main Avenue, which created two unequal portions, the larger of which was to the south and the smaller to the north. The comparatively shorter Transverse Avenue bisected the Main Avenue at its mid-point and linked the entrance on Sandyford Street to the so-called Grand Entrance that opened into Kelvingrove Park. As can be seen in , this entrance took the form of a triple-headed doorway recessed into a large horseshoe-shaped arch of “Moorish design.”17 Sellars’ Main Building and its adjoining Machinery Annexe was the exhibition’s focal point. This structure sat within 14.5 acres of designated parkland, making the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 the largest exhibition held in Britain since the London International Exhibition of 1862.18

Figure 2. Plan of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 printed in the official guide to the exhibition. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

Figure 3. Left: Exterior of the Main Building (north-facing) of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888, designed by James Sellars. Right: An etching by Munro Bell of the Grand Entrance to the Main Building of the Glasgow International Exhibition. Both by permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

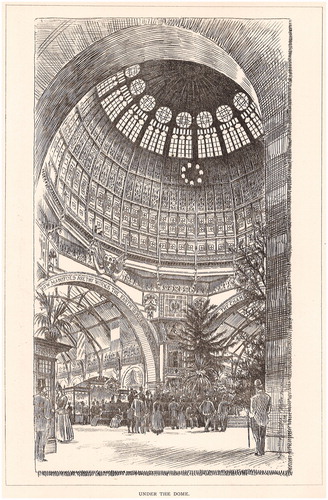

Published guides encouraged visitors to enter the exhibition through the gates on Gray Street, which served as the “starting point from which the most systematic inspection [could] be made.”19 This would have channelled exhibition-goers into the Grand Hall, a large open space inside the Main Building that was used for musical performances. On the left was the entrance to the Picture Galleries and on the right were three courts showcasing “women’s industries,” principally lace-making, weaving and needlework. Proceeding down the Main Avenue, visitors would have observed displays of British manufacturing. The 14 arched courts that opened onto this 60-foot-wide thoroughfare and a narrower east-west corridor contained exhibits primarily from Glasgow-based firms, such as displays of textiles and leatherwork, printing, chemical production, and mining and metallurgy. Having made their way through the eastern section of the Main Building, visitors would have reached the colossal concave space underneath the Grand Central Dome, which marked the intersection between the Main and Transverse Avenues.

Supported by four substantial octagonal towers made of brick and topped by a lantern, the Grand Central Dome dominated the building and didactic sources like guides and catalogues highlighted its technical and aesthetic significance.20 It measured 80 feet in diameter and was formed by 16 ribs covered in sheet iron, with the exception of glazing near its apex. Internally, the four pendentives that stretched up to cornice level contained small curtained balconies supported on “Moresque trusses,”21 and coves were painted with allegorical figures representing Industry, Science, Art and Agriculture by George Henry, John Lavery, James Guthrie and E.A. Walton, four of The Glasgow Boys.22 Above this were the coats of arms of Britain, France, Germany and the United States, and scriptural texts stretched across the four semi-circular arches that formed the approaches to the Main and Transverse Avenues. This heavily decorated space was further enriched by potted palms, floral decorations and ornamental trees, as can be seen in . Occasioning a moment’s pause, the area underneath the Grand Central Dome was a “place of great resort for visitors.”23 After taking in its sights, exhibition-goers were expected to enter the western wing of the Main Building, which housed the five courts dedicated to foreign exhibitors and the colonial courts of Canada, Ceylon and India. Continuing along the Main Avenue, visitors would eventually have reached the entrance of the Machinery Annexe, which displayed large-scale industrial objects such as working engines and drills.

Figure 4. An illustration of the interior of the Grand Central Dome from Pen-and-Ink Notes at the Glasgow Exhibition. By permission of University of Glasgow Library.

While his proposal was titled “The Bishop’s Palace,” according to Sellars the architectural treatment of the exhibition was “Oriental in character.”24 The official guide to the exhibition explained to readers that this accounted for the Main Building’s “Moorish” appearance, which was exemplified by the architect’s reproduction of “effects which are to be seen … in the ecclesiastical edifices of Cordova.”25 This reading was likely informed by the semi-circular shape and decorative patterning of the arches of the exhibition’s main gates (), which betrayed a strong similarity to the double arches of the prayer hall inside Córdoba’s Great Mosque-Cathedral. Another interpretation, proffered by the lavish souvenir publication Pen-and-Ink Notes of the Glasgow Exhibition, was that Kelvingrove Park had been transformed into “Bagdad [sic] by the Kelvin,” and yet the author also advocated that Sellars’ scheme was inspired by the “best examples of Moresque work” and drew particular influence from “the Mosques at Cairo.”26 Lastly, a popular guide to the exhibition proposed that Sellars’ design referenced the general building type of “Eastern mosques,” as well as the specific structures of the Alhambra, the Kremlin and the Hagia Sophia.27

Figure 5. An illustration of the Prince of Wales gates at the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 from Pen-and-Ink Notes at the Glasgow Exhibition. By permission of University of Glasgow Library.

In Culture and Imperialism, Said argues that metropolitan representations of places beyond the borders of the metropole evidence the propensity of imperial societies to re-form and re-shape the extra-European world in accordance with familiar conventions.28 The diversity of attributions made to Sellars’ vision, recounted above, evidences this tendency and underlines that the exhibition’s overall aesthetic aligned with nineteenth-century notions of “oriental” architecture. Contemporary understandings and interpretations of the “Orient” frequently overlooked regional differences and collapsed distinct styles found across a multifarious geographic area that extended from India to southern Spain, taking in the Middle East and North Africa along the way, into a single unit.29 Looking at specific formal elements, the repeating horseshoe-shaped windows that ran the length of the Main Building’s façade for instance were quintessential elements of what European designers, artists and art historians understood as “Islamic” or “oriental” architecture.30 Other characteristics associated with this supposedly homogeneous and timeless genre included the towers and minarets topped with spires, onion domes and flags, which encircled the Grand Central Dome and were commanding features of the building’s external appearance.

The “oriental” character of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 was also expressed through the internal architecture and interior design and decoration of its Main Building. Colonnades topped by wooden multifoil and horseshoe arches, the placement of palms in coloured pots and stands, and a bold palette of primary colours applied to the building’s interior and exterior surfaces helped signal to visitors that they were in an “exotic” environment. Palms for example were common features within nineteenth-century interiors that sought to express an “oriental” theme, because they were seen as highly exotic natural objects. As Sparke contends, these plants were a key element of orientalist iconography and in Britain not only evoked the sumptuousness, warmth and relaxation of a tropical environment, but also, given many of their countries of origin, the authority of the British Empire.31 At the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 these plants were set within a colourful and ornate interior space. This comes through very clearly in the following description of the interior of the Grand Central Dome:

[The frieze] is formed by an elaborate and elegant arabesque stencilled in red on a gold ground, and enriched by points of a blue-green colour. … The iron-work is painted a gold colour, and the wood infilling is enriched by a quaint arabesque design stencilled on in strong red, blue, yellow, and green. The colours employed may be regarded as impossible to harmonise, but the influence of the one colour on the others by juxtaposition has been fully appreciated, and a pleasing and varied effect is the result.32

Figure 6. View of the interior architecture and decoration of the Main Building, Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

The colourful nature of Sellars’ design attracted mixed reactions. For some, it was successfully realised and added to the exhibition’s sensory delight. While recognising that the Main Building may have appeared “somewhat bizarre” at first sight, a special issue of The Art Journal was positive about its affective power. In particular, the reviewer praised the architect for designing an environment that diverged from the familiar and the quotidian:

[Sellars] has started evidently with the conviction that such a building should be indeed ‘a pleasure house,’ suggestive in both line and colour something far removed from the dull routine of daily life. He has aimed at a contrast to the grey monotony of Glasgow streets, and he has been successful in attaining it. The effect produced upon both the eye and mind is one of pleasant exhilaration.34

Hall’s assessment that the plan and style of the Main Building complemented the function of an international exhibition echoes Sellars’ explanation that an “oriental” aesthetic was adopted because of its “suitability for the purpose.”38 A belief in the superficial beauty of art and architecture of the so-called ‘Islamic world’, a tenet of the industrial imperial worldview that Jones and other design reformers adhered to, is a potential rationale for this claim, since its ostensible frivolity could have been perceived as appropriate to a building type that was temporary and used for amusement and spectacle. Moreover, constructing an environment that contrasted visitors’ routine environs, a sentiment that abounds in the assessment published in The Art Journal, was integral to fostering the notion that these events constituted a form of travel and offered a touristic experience. In the case of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 therefore, Sellars’ design may have sprung from the premise that an “oriental” locale, which evoked notions of the exotic and conjured feelings of warmth and relaxation, was the form best suited to the exhibition’s function. Further nuancing this line of analysis, it is contended that the “oriental” character of the exhibition sought to replicate an experience not only of geographic travel, but also of temporal travel due to the supposedly a-historical nature of art and architecture produced in Muslim-majority countries and societies. Lastly, Sellars’ scheme may have fostered a feeling among visitors of moving through not simply a distant, faraway locale, but a syncretic colonial periphery. This is because Sellars utilised an architectural language popularly associated with an imagined “Orient,” a fabrication that was one element within a wider pantheon of images, ideas and perceptions that constituted British imperial culture and characterised understandings of the relationship between metropole and periphery in the late-nineteenth century. Such a reading hastens the conclusion that time spent within the physical space of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 constituted a momentary step out of place and time, thereby stimulating a liminal experience for exhibition-goers.

Having considered the plan, architectural forms, style and interior design of Sellars’ Main Building, the discussion now shifts focus and looks at the wider site of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. A number of supplemental and outdoor attractions throughout Kelvingrove Park complemented Sellars’ Main Building (see ). It was out in the grounds of the park that visitors moved away from the purely educational elements of the exhibition and gained access to its amusements. It has previously been suggested that in Britain interest in international exhibitions waned between the 1870s and the turn of the twentieth century because organisers were slow to acknowledge that key to the ongoing success of these events was blending high and popular culture.39 Notably bucking this trend, the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 very clearly combined education and entertainment. This fusion is especially apparent when one considers the attractions that featured across Kelvingrove Park. On the one hand, the Bishop’s Palace and Kelvingrove Mansion, the structures themselves as well as the exhibits they contained, were predominantly educational. In contrast, custom-installed ornamental fountains, a switchback railway, cafés and restaurants, bandstands, and kiosks selling souvenirs, tobacco and flowers were diversions designed to amuse and entertain. An article published in The Glasgow Herald the day the exhibition opened provides an astute observation about the relationship between these two components or genres of attraction, noting that the latter “constitute the sauce which makes the more serious fare provided in other parts of the Exhibition go down.”40

The Bishop’s Palace, from which the name of Sellars’ overall plan derived, was a facsimile of the medieval castle that had been the residence of the Bishops of Glasgow. The original had been built adjacent to Glasgow Cathedral sometime prior to 1258, but by the mid-eighteenth century was in ruins, a state that precipitated its eventual removal in 1789. Made of wood, plaster and canvas, the replica that temporarily popped up in Kelvingrove Park during the summer and autumn of 1888 was erected to house materials that evoked Scotland’s past, namely archaeological artefacts, portraits, medals, coins, books, and letters. The loaned objects were grouped together to form three main sections: prehistoric Scotland, Scotland during the reign of Mary Queen of Scots and her descendants, and Glasgow in past times. As a popular guide to the exhibition explained, “age is the attractive feature here, both outside and inside.”41 In Pen-and-Ink Notes of the Glasgow Exhibition, Robert Walker acknowledged that the objects exhibited inside the Bishop’s Palace were of national import, but also drew readers’ attentions to the local significance of the enclosing structure. He praised Sellars for incorporating “an ancient building around which clung historic associations” and advocated that its “restoration … is a reminder to us of the forces that gave birth to Glasgow.”42

Like the Bishop’s Palace, both the objects exhibited inside Kelvingrove Mansion and the enclosing physical structure conveyed meaning and fulfilled a largely educational and didactic purpose. Kelvingrove Mansion () was a handsome neo-classical building designed by Robert Adam in the late-eighteenth century and built by the merchant and politician Patrick Colquhoun, one of Glasgow’s “Tobacco Lords.”43 The exhibition’s only permanent structure, Kelvingrove Mansion pre-dated the creation of Kelvingrove Park and since 1870 had been the premises of Glasgow’s main municipal museum. On the occasion of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 it was used to display Queen Victoria’s Jubilee presents. According to guides and other contemporary sources, securing permission to ship these items to Scotland was a coup and their presentation in Glasgow marked the last time that the full collection—some 800 pieces gifted to the monarch by the British Empire’s dominions, colonies and territories, as well as foreign countries—was to be publicly exhibited.44 From a postcolonial standpoint, much can be read into the politics of display at work when objects from Britain’s colonies were presented before metropolitan audiences.45 There is a potency to exhibiting materials that were amassed to commemorate Queen Victoria’s reign, a gesture that renders the objects newly in the monarch’s direct possession material signifiers of the physical territories over which she ruled. Pushing this line of analysis, it can be argued that the action of transferring the collection to Glasgow temporarily transformed the city into the imperial nexus around which this deeply symbolic collection of colonial objects revolved.

Figure 7. Kelvingrove Mansion, Glasgow. Photograph by Thomas Annan published in The Old Country Houses of the Old Glasgow Gentry (1870). By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

In the context of the present discussion, however, it is pertinent to reflect on the significance of the building itself and how it functioned as a site of meaning-making for the duration of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. Kelvingrove Mansion arguably possessed different affective qualities compared to its ordinary function as a municipal museum when encountered within the space of an international exhibition, a planned environment that, as has been established, fostered notions of geographic and temporal travel. By the late 1880s Kelvingrove Mansion was one of the few remaining private homes built by members of the city’s Georgian mercantile elite, making it a relic from a period in Glasgow’s past associated with pronounced material affluence and growing imperial and global connections. A sense of how Kelvingrove Mansion was regarded around the time of Glasgow’s first international exhibition can be gleaned from newspaper articles and other contemporary writings. Opposing plans for the mansion’s demolition, an article published in The Glasgow Herald in 1898, for example, made a clear case for its historical import and rarity:

Without overstating the value of Kelvingrove House, it may fairly be said that it is a good example of the charming, original, and graceful style of Robert Adam. It is nearly 120 years old, and has become the memorial of an age which is rapidly fading from us to live only as history. It is the symbol of the thought, the habit, the aspiration of the class which called it into being.46

These accounts suggest that Kelvingrove Mansion was understood as significant because of its connections to notable personages. Additionally, it was recognised as an important piece of built heritage due to its status as one of the few remaining visible traces of a crucial period in Glasgow’s economic and social development. It seemingly encapsulated a time when the site of the exhibition and its surrounding districts were “rural in all its features” and “lay remote from the clatter of the streets.”48 Thus constituting a foil to the contemporary city, Kelvingrove Mansion spoke to a time before Glasgow’s rapid urbanisation during the nineteenth century. Moreover, its association with the city’s Georgian mercantile elite rendered it a testament to the wealth accrued during the period that paved the way for Glasgow’s later industrial expansion, the results of which were on show inside the exhibition’s Main Building. Consequently, like the Bishop’s Palace a short walk away, Kelvingrove Mansion acted as an emblem of municipal pride, evoking a bygone age and a foundational period in Glasgow’s history. In the context of the exhibition, both buildings were evidently perceived as objects of nostalgia. But whereas the former transported visitors to the city’s medieval past, the latter invoked the moment of Glasgow’s transformation into a major port city entrenched in imperial networks.

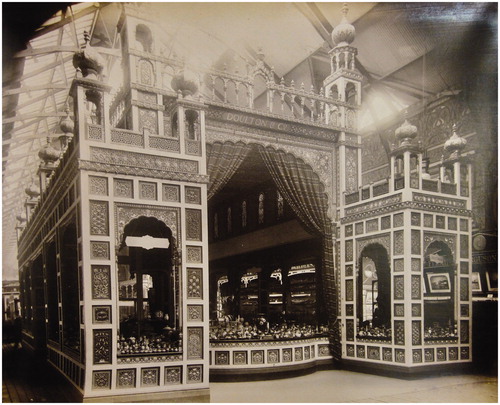

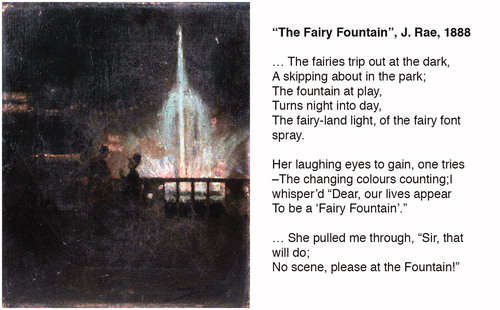

Neighbouring the Bishop’s Palace and Kelvingrove Mansion was a collection of additional attractions and amusements that further enriched the built environment of the exhibition and rounded out its offering to visitors. This included a switchback railway, shooting ranges, Venetian gondolas plying the River Kelvin, and two large ornamental fountains. The Fairy Fountain designed by the Manchester-based iron founders W. & J. Galloway attracted particular attention, the appeal of its coloured lights and cascading waters captured in paint and verse (). Fabricated entirely out of terracotta, the Doulton Fountain functioned not only as a technical demonstration of the work of Doulton & Co., but also as a celebratory piece of statuary. Containing four figurative groups representing Australia, Canada, India and South Africa, various military personnel, and a statue of Queen Victoria at its apex, the fountain was clearly intended to symbolise and project Britain’s imperial might ().

Figure 8. Left: John Lavery, The Fairy Fountain, Glasgow International Exhibition (1888). Wikipedia Commons. Right: Lyrics to “The Fairy Fountain,” a song written about the International Exhibition of 1888 by J. Rae and published by W. Hicks in 1888.

Figure 9. The Doulton Fountain was originally erected in Kelvingrove Park for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. It was moved to Glasgow Green, where it remains, in 1890. Photograph courtesy of Paul Twynam.

There were also specially erected kiosks that were architecturally in keeping with the style of the exhibition’s Main Building (), and a variety of restaurants and cafés. In addition to the Royal Bungalow Dining Room, which was also “oriental” in character, there was the Ceylon Tea House, the Bachelors’ Café and Van Houten’s Cocoa House. As a contemporary observer explained, these varied “picturesque features” were useful “houses of call” since “at the Glasgow Exhibition, just as at other Exhibitions, there is always a number of people who are faint and weary.”49 The same source noted how the “costumes of the dusky-faced waiters from the Bungalow and the Ceylon Tea House give variety and unexpected notes of colour to the ever-shifting masses of the crowd.”50 Exoticising the individuals who worked at these establishments, this statement makes clear that international exhibitions were understood as sites of intercultural encounters and that people-watching was part of the experience.51 If Lavery’s painting and Rae’s lyrics capture a sense of carefree amusement, of sweet-nothings exchanged in colourful, dream-like surroundings, Walker’s account likewise references a novel environment, although one that engendered a sense of voyeuristic excitement and exhaustion in equal measure. Although these reflections are different in tone, they similarly evoke the sensation of exploring somewhere new and unfamiliar, of travelling to an otherworldly, at times overwhelming, land.

Figure 10. Tobacco kiosk erected in Kelvingrove Park for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

Constructing a vision of the “Orient” through an architectural language and iconography many visitors would have been able to read and decipher, the built environment of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 aimed to conjure a foreign land in the minds of exhibition-goers. Spectators were encouraged to inhabit another world upon entering the exhibition, one that looked and felt very different from the one to which they were accustomed. This assessment aligns with van Wesemael’s claim that international exhibitions had a mesmerising effect on visitors and that the capability of architecture to transform the exhibition into a secluded universe accounted for much of this sensation.52 This line of investigation, however, can be further developed. Constructing the illusion of a journey through space and time, the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 offered visitors a liminal experience. The architecture and built environment of the exhibition was the vehicle that transported exhibition-goers to places new and unknown, an experience that chimes with Stewart’s notion of an “excursion.” For Stewart, this fictive concept marks a holiday from the “world of mechanized labor and mechanical reproduction” and sees the traveller inhabit “a carnival mode.”53 This adds weight to the argument that the built environment of the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 provided the crowds that swelled its halls and avenues with a momentary fictional escape from industrialised urban life. The exhibition’s architectural scheme sought to effect in the viewer the experience of leaving behind the grime and soot of Glasgow for the “grace and glow” of the “Orient,” an imagined realm that existed only in the imperial mind.54

The structures that made up the built environment of Glasgow’s first international exhibition—structures that exhibition-goers beheld from afar, observed up close, moved through, perhaps touched, and stood in the shadows of—worked together to render the exhibition a site of imperial meaning-making. First and foremost, there was the overt orientalism not only of Sellars’ Main Building, the contents of which were intended to be educational and edifying, but also of ancillary structures erected across Kelvingrove Park, which served a more recreational purpose. Evoking a syncretic colonial periphery, these buildings effected a sensation of traversing geographic thresholds. Complementing these “exotic” forms, the architecture of the Bishop’s Palace and Kelvingrove Mansion, which were representative of domestic historical styles, aroused the feeling of crossing temporal thresholds. These buildings took exhibition-goers back in time to notable periods in Glasgow’s past, the physical remains of which were becoming scarce amid the city’s increasingly industrial landscape. When experienced all at once the effect was a day trip through space and time that made a claim to Glasgow being a metropolis at the centre of the British Empire. Therefore, if a primary function of international exhibitions was to present the world in microcosm, the realm audiences encountered during the summer and autumn of 1888 was a decidedly imperial one with the “second city of the empire” occupying a pivotal place within it. This is a pointed demonstration of how empire wove itself, both materially and imaginatively, into the everyday. Returning to Duncan’s definition of a liminal experience, this was the new larger perspective that exhibition-goers were intended to gain from a day out at the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. The exhibition’s architecture and built environment carried spectators to a fanciful setting that contrasted their habitual urban environment. It was this brief excursion marked by the experience of imaginatively stepping outside of the city that enabled exhibition-goers to see it anew; to perceive Glasgow not simply as a municipality “shocked and choked” by industry, but as an imperial metropolis capable of collecting together the arts and manufactures of the world.55

Notes on contributor

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Dr Sabine Wieber, Professor Michael Wayne and Dr Robyne Calvert who generously read iterations of this text and thus contributed to its evolution and development. I thank them for their incisive feedback and encouragement.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rosemary Spooner

Rosemary Spooner is a Lecturer in the School of Humanities at the University of Glasgow where she teaches on the Museum Studies MSc programme, and was previously a Lecturer in Design History and Theory at the Glasgow School of Art. Sitting at the intersection of art, design and architectural history, museum studies and postcolonial theory, her work examines the visual and material culture of empire. She is interested in how objects and images moved across different spheres of the British Empire, frequently finding their way into museums and other spaces of exhibition and display, as well as the postcolonial legacies of these itinerant processes.

Notes

1 “The Prince Consort Can Claim the Credit,” Times [London], February 23, 1850, 4.

2 Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London: Routledge, 1995), 66.

3 Kylie Message and Ewan Johnston, “The World Within the City: The Great Exhibition, Race, Class and Social Reform,” in Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851, ed. Jeffrey A. Auerbach and Peter H. Hoffenberg (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), 32.

4 Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose, eds., At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 30.

5 See for example International Exhibition season tickets in the collections of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford (London, 1851), Museums Victoria (Melbourne, 1861/London, 1862), State Library of South Australia (Adelaide, 1887), National Museum of Ireland (Cork, 1902), and Owaka Museum Wahi Kahuika (Dunedin, 1925–26).

6 For an analysis of how the passport constructs and defines the nation-state see Radhika Viyas Mongia, “Race, Nationality, Mobility: A History of the Passport,” in After the Imperial Turn: Thinking With and Through the Nation, ed. Antoinette Burton (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 196–214.

7 Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums (London: Routledge, 1995).

8 See for example Auerbach and Hoffenberg, eds., Britain, the Empire, and the World at the Great Exhibition of 1851; Peter H. Hoffenberg, An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); and John M. MacKenzie and John McAleer, eds., Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015). A crucial exception is Zeynep Çelik, Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-century World’s Fairs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

9 For a discussion of the complex interplay between contents and container with respect to museum architecture see Michaela Giebelhausen, “The Architecture Is the Museum,” in New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction, ed. Janet Marstine (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 41–63.

10 “Design by Joseph Paxton, F.L.S., for a Building for The Great Exhibition of 1851,” Illustrated London News, July 6, 1850.

11 While Perilla and Juliet Kinchin’s book, Glasgow’s Great Exhibitions: 1888, 1901, 1911, 1938, 1988 (Edinburgh: White Cockade, 1988) provides a comprehensive summary of the city’s four international exhibitions and the Garden Festival of 1988, it is largely descriptive and contains minimal critical analysis and evaluation. Bob Crampsey’s The Empire Exhibition of 1938: The Last Durbar (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing Company Ltd, 1988) focuses almost exclusively on the Empire Exhibition, Scotland of 1938 and is largely a personal reminiscence. Shorter pieces by John M. Mackenzie (1999) and Sarah Britton (2010) address International Exhibitions held in Glasgow, but they are only one element within the authors’ broader discussions.

12 James Hamilton Muir, Glasgow in 1901 (Glasgow: William Hodge & Company, 1901, reprinted Oxford: White Cockade Publishing, 2001), 11. All citations from 2001 edition.

13 “The Prince and Princess of Wales left London Yesterday Morning on their Journey to Scotland,” Glasgow Herald, May 8, 1888.

14 Paul Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851–1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), 2.

15 Marta Filipová, ed., Cultures of International Exhibitions 1840–1940: Great Exhibitions on the Margins (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015); John M. MacKenzie and T.M. Devine, eds., Scotland and the British Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 27.

16 Glasgow International Exhibition of Industry, Science and Art 1888: Elliot’s Popular Guide to Glasgow and the Exhibition with Excursion Notes (Glasgow: A. & W. Elliot, 1888), 17.

17 International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888: Official Guide (Glasgow: T. & A. Constable, 1888), 29.

18 Robert Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes at the Glasgow Exhibition: A Series of Illustrations by T. Raffles Davison, F.S.I.A. with an Account of the Exhibition by Robert Walker, Secretary to the Fine Art Section (London: J.S. Virtue & Co. Ltd., 1888), 3–5.

19 Elliot’s Popular Guide, 47.

20 The Glasgow Exhibition, 1888: Special Number of the Art Journal (London: J.S. Virtue and Co., 1888), 3.

21 International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 47.

22 For further information about this group of painters, see Roger Billcliffe, The Glasgow Boys (London: Frances Lincoln, 2008); and Hugh Stevenson and Jean Walsh, Pioneering Painters: The Glasgow Boys (Glasgow: Glasgow Museums Publishing, 2010).

23 International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 47.

24 James Sellars, as quoted in International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 27.

25 International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 27.

26 Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes, 8.

27 International Exhibition of Industry, Science and Art: Pen & Pencil Exhibition Number (Glasgow: MacLure, MacDonald & Co., 1888), 2.

28 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (London: Chatto & Windus, 1993), 119.

29 Mark Crinson, Empire Building: Orientalism and Victorian Architecture (London: Routledge, 1996); and Zeynep Çelik, “Colonialism, Orientalism, and the Canon,” Art Bulletin 78, no. 2 (1996): 202–05.

30 Solmaz Mohammadzadeh Kive, “The Exhibitionary Construction of the ‘Islamic Interior’,” in Oriental Interiors: Design, Identity, Space, ed. John Potvin (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 39–57.

31 Penny Sparke, “Paradise in the Parlor: Cozy Corners and Potted Palms in Western Interiors, 1880–1900,” in Oriental Interiors, ed. Potvin, 209–13.

32 International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 49.

33 Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (London: Day and Son, 1856). For a critical analysis of Jones’ treatise see for example Stacey Sloboda, “‘The Grammar of Ornament’: Cosmopolitanism and Reform in British Design,” Journal of Design History 21, no. 3 (2008): 223–36; and Toshio Watanabe, “Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament: ‘Orientalism’ Subverted?” Aachener Kunstblätter 60 (1994): 439–42.

34 The Glasgow Exhibition, 1888, 3.

35 Andrew Hall, “Architecture of the Glasgow Exhibition Buildings, Scottish Art Review 1, no. 3 (1888): 60.

36 Hall, “Architecture of the Glasgow Exhibition Buildings,” 61.

37 Hall, “Architecture of the Glasgow Exhibition Buildings,” 59.

38 James Sellars, as quoted in International Exhibition Glasgow, 1888, 27.

39 Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas, 32.

40 “The Prince and Princess of Wales left London Yesterday Morning,” Glasgow Herald, May 8, 1888.

41 Elliot’s Popular Guide, 81.

42 Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes, 102–03.

43 A colonial merchant who traded in North America and the Caribbean, Patrick Colquhoun was founder and Chairman of Glasgow’s Chamber of Commerce, the oldest institution of its kind in Britain, and was Lord Provost from 1782–1784. For discussion of Glasgow’s “Tobacco Lords” and their involvement in the trans-Atlantic imperial economy see, for example, Stephen Mullen, “A Glasgow-West India Merchant House and the Imperial Dividend, 1779–1867,” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies 33, no. 2 (2013): 196–233; and T. M. Devine, Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past: The Caribbean Connection (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015).

44 Elliot’s Popular Guide, 83.

45 Henrietta Lidchi, “The Poetics and the Politics of Exhibiting Other Cultures,” in Representation, 2nd ed., ed. Stuart Hall (London: The Open University, 2013), 120–91.

46 “The Retention of Kelvingrove House,” Glasgow Herald, December 10, 1898.

47 The Old Country Houses of the Old Glasgow Gentry (Glasgow: James Maclehouse, 1870).

48 Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes, 1.

49 Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes, 118.

50 Walker, Pen-and-Ink Notes, 120.

51 For a comprehensive and trenchant analysis of metropolitan preoccupations with human exhibitions and how such spectacles bolstered notions of racial difference, see Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

52 Pieter van Wesemael, Architecture of Instruction and Delight: A Socio-historical Analysis of World Exhibitions as a Didactic Phenomenon (1798–1851–1970) (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2001), 17.

53 Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 60.

54 Martin Quern, “A Ballade of Kelvin Fair,” Scottish Art Review 1, no. 7 (1888): 181.

55 Alexander Thomson, Art and Architecture: A Course in Four Lectures, 1874, as quoted in James Schmiechen, “Glasgow of the Imagination: Architecture, Townscape and Society,” in Glasgow, vol. 2, 1830–1912, ed. W. Hamish Fraser and Irene Maver (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), 496.