ABSTRACT

Objective

Chronic suicide risk identification in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is fundamental to risk tolerant intervention. To further the clinical understanding of chronic risk in BPD, this systematic review examined studies which compared factors associated with suicidality in BPD with those in any depressive disorder (DD).

Method

Databases PsycINFO, Medline Complete, EMBASE, and Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global were systematically searched using a set of relevant search terms. Studies written in English between 1996 and 9th January 2023 meeting inclusion criteria (adult/adolescent participants; compared factors related to suicide attempts, ideation, intent, lethality or parasuicidal gestures in BPD and DD, or explored BPD traits within suicidality in DD; and used structured diagnostic assessments or expert interview based upon DSM) were reviewed and assessed for quality using Joanna Briggs Institute Checklists. Studies were grouped by how suicidality was operationalised, and organised by the constructs that were compared.

Results

Findings from 14 studies (5189 participants) indicated that interpersonal dysfunction, impulsivity, aggression, anger/hostility in adult samples, and early onset of depression and self-injury may discriminate suicidality in BPD from DD for recurrent suicide attempts only. Expressed suicidal intent is higher in BPD than DD, while lethality of attempts is the same.

Discussion

Comparison of suicidality in BPD and DD requires further investigation. Findings suggest associated factors that might support risk assessment in BPD.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is recurrent or “chronic” in nature; on average an individual will attempt suicide 3.3 times in their lifetime.

Persons with BPD presenting with chronic suicidality can regress in their capacity to take responsibility for their own safety, when clinicians employ the protective or custodial interventions that are indicated for acute risk.

Clinical risk assessment and intervention in BPD can be complicated by the occurrence of comorbid depression, which may result in an acute episode of suicidality overlaying the individual’s chronic pattern of self-injury.

What this topic adds:

Suicidality in BPD may be differentiated from acute suicidality in depression by the presence of the BPD traits of interpersonal dysfunction, impulsivity, aggression, and anger/hostility (in adults), but only when suicide attempts are recurrent across the lifetime.

Early onset of psychopathology and a pattern of higher expressed suicidal intent despite lower lethality of attempts also appear to discriminate suicidality in BPD from that in depression.

Clinical risk formulation in BPD could be benefitted by further research into discriminating chronic suicidality; however, clinical assessment should focus on particular BPD traits, the developmental trajectory of psychopathology, and potential discrepancies between expressed intent and suicidal behaviour.

There is notable agreement across theoretical paradigms that chronic suicidality in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is fundamentally different from that seen in acute disorders (Rao et al., Citation2017; Yen et al., Citation2021). However, empirical research is still striving to validate clinical experience and theoretical conceptualisations. Clinical and theoretical literature regarding self-injury in BPD use the term “chronic” to represent behaviours that are part of a long-term pattern across an individual’s history (Bateman & Krawitz, Citation2013; Beatson, Citation2010; National Health & Medical Research Council, Citation2013; Sansone, Citation2004; Wedig et al., Citation2012). Conversely, the term “acute” is used to describe risk behaviours that are not part of the person’s chronic history of self-injury, and may accompany an acute episodic presentation such as major depression (Beatson, Citation2010; Sansone & Fierros, Citation2012). These two types of risk differ in terms of whether the behaviour is new, or different from usual (acute), versus the same as usual (chronic), not whether it is imminent or lethal (Beatson, Citation2010, National Health & Medical Research Council, Citation2013).

As defined by Sansone and Fierros (Citation2012), acute suicidal behaviour is an emergent and uncharacteristic response by an individual to an acute and overwhelming psychosocial stressor associated with episodic mental health disorders such as depression. Though there may be ambivalence in the individual’s intent, the function of acute suicidal behaviour is primarily to end one’s life. Conversely, chronic suicidality in BPD, defined as a semi-chronic process of expression of suicidal intent with or without suicide attempts or gestures, may or may not indicate serious intent to end one’s life (Wedig et al., Citation2012). Rather, it has a variety of functions, most predominantly to regulate other BPD symptoms such as affective and interpersonal instability, and is usually triggered by a recent event marked by a predominantly relational theme (Beatson, Citation2010; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2021; Sansone, Citation2004). The relationship between BPD and multiple suicide attempts is well established, consistent with the construct of “chronic” suicidality, and reflected in one of the nine diagnostic criteria for BPD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). While 10% of individuals with BPD will die of suicide (Black et al., Citation2004; Sansone, Citation2004), 60 to 70% will attempt it, with an average of 3.3 attempts during their lifetime (Goodman et al., Citation2012).

In terms of societal burden, BPD is considered to be one of the most costly mental health disorders due to regular hospitalisations, crises, self-harm and suicide attempts, comorbidities, and poor socio-occupational functioning (Bourke et al., Citation2021; Hastrup et al., Citation2019). BPD is associated with high levels of carer burden including impacts upon psychological welfare, practical life issues, and financial status (Sutherland et al., Citation2020).

Management of risk is not exclusive to BPD, however most other suicidal presentations are acute in nature and the role of intervention for acute risk is protective; the clinician is usually required to take a “paternalistic” and directive approach, assuming responsibility for the person’s safety (State Government of Victoria Department of Health, Citation2010). In contrast, recurrent acts of self-injury and suicidality are a specific feature of BPD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), and discriminating between chronic and acute self-injury is an important task for clinicians, who are faced with having to respond differently to these two clinical phenomena (Krawitz & Batcheler, Citation2006).

As described by Bateman and Krawitz (Citation2013), when confronted with the long-term, ongoing risk of chronic suicidality, the professional needs to approach it as part of the presentation, and to not take active responsibility for addressing the risk. As early as the 1970s, it was recognised that chronic suicidal behaviour and self-harm in BPD has a relational complexity to it and necessitates distinctive, risk-tolerant management (Olin, Citation1976; Schwartz et al., Citation1974); the clinician is required to maintain ongoing psychological treatment, without escalating to a management response that functions to protect the individual. This involves identification of the risk as consistent with the client’s usual historical pattern of self-injurious behaviours, and short-term risk needs to be tolerated for long-term psychological growth (Beatson, Citation2010; Rao et al., Citation2017). Choosing a risk tolerant approach in this case can be crucial to the client’s wellbeing, with iatrogenic outcomes possible if chronic suicidality is treated as if it is acute (Bateman & Krawitz, Citation2013; Coyle et al., Citation2018; J. G. Gunderson & Links, Citation2008; Warrender, Citation2018); these clients will often respond to containment and withdrawal of responsibility with increased suicidal acts (Krawitz & Batcheler, Citation2006).

Current risk assessment practices with BPD recommend formulating the presenting risk as consistent or inconsistent with the individual’s historical pattern of self-injury behaviour. If comparable to the chronic pattern, even if the behaviour is imminent or potentially lethal, a risk tolerant approach is recommended in order to allow psychological growth (Beatson, Citation2010; National Health & Medical Research Council, Citation2013; Rao et al., Citation2017). Australia’s National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for working with BPD clients (NHMRC, 2013) includes a matrix tool that guides formulation and intervention for an imminent risk through establishing correspondence with one of the four quadrants (chronic high risk, chronic low risk, new low risk behaviour, acute risk), across two dimensions: (a) potential lethality and (b) newness of the behaviour/chronicity (see ). Presentations that fall within the chronic quadrants indicate risk tolerance, which when high risk, usually requires a strong team approach and consistent application of a complex case plan, often with executive psychiatrist sign-off. Presentations that show potential high lethality are only considered acute in this model if the behaviour is inconsistent with the individual’s chronic pattern of risk. Low lethality new behaviours require a combination of risk tolerance and ongoing monitoring to establish whether an acute risk is pending (Rao et al., Citation2017). Discernment of an imminent risk as either acute or chronic is of particular relevance when a client with a well-known long-term pattern of self-injury presents with behaviours that are both high risk and different from their historical pattern; this represents a shift to acute risk and necessitates risk averse practices (Beatson, Citation2010; NHMRC, 2013).

Figure 1. Matrix guide to assist clinicians in formulating self-injury risk in BPD (based on NHMRC, 2013).

Despite this clinical model that guides risk assessment with BPD, making a distinction between chronic and acute risk is complicated by the complexity of self-injury function and intent in this group of clients, as well as clinician anxiety about tolerating the risk if it is formulated as chronic (Beatson, Citation2010). There is therefore a need to better understand the nature of chronic self-injury behaviours, and how these differ from acute suicidality in terms of predictors and associated factors. Such knowledge may allow clinicians to feel more confident to tolerate chronic risk even when the potential lethality is high, especially with new clients whose history of self-injury is undocumented.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is an acute presentation which, like BPD, contains suicidality as a diagnostic criteria; it is known to be the most common mental disorder that can result in death by suicide (Hawton et al., Citation2013). MDD is defined as depressed mood and loss of interest or pleasure, present for at least two weeks, and accompanied by a number of vegetative symptoms such as loss of appetite, insomnia, motor agitation or retardation, and/or lack of concentration (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Major depressive episodes (MDE) can also occur within bipolar and other related disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Suicidality in depression is an acute presentation that is associated with a short-term increase in risk (Soloff & Chiappetta, Citation2012; Soloff & Fabio, Citation2008). Unlike chronic risk in BPD, interventions for risk in MDD respond to the acute nature of the risk, and clinicians are required to take responsibility for the client (Ho, Citation2014), whose cognitive functioning and judgement is considered temporarily impaired (Mukherjee et al., Citation2020; Sumiyoshi et al., Citation2021). BPD and MDD share high rates of comorbidity (McGlashan et al., Citation2000), which complicates the clinical task of discriminating chronic from acute risk, because an individual with BPD and a chronic risk profile can present with periodic, acute suicidality due to episodic MDD. In these cases, clinicians need to shift their approach from risk tolerance practices, to taking responsibility for the client’s safety (Beatson, Citation2010).

Despite theoretical and clinical wisdom regarding the specificity of suicidality in BPD, experimental research is still endeavouring to empirically validate theoretical opinion and clinical experiences in the field (Bateman & Krawitz, Citation2013; J. Gunderson, Citation2011; Paris, Citation2004; Sansone, Citation2004; Yen et al., Citation2021). Of the nine BPD criteria in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5-TR; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), affective instability (Ducasse et al., Citation2019; Links et al., Citation2007; Rebok et al., Citation2015; Rizk et al., Citation2019; Sher et al., Citation2016; Wedig et al., Citation2012; Yen et al., Citation2004) and impulsivity (Andrewes et al., Citation2019; Boisseau et al., Citation2013; Brodsky et al., Citation1997; Corbitt et al., Citation1996; Ducasse et al., Citation2019; Popovic et al., Citation2015; Rebok et al., Citation2015; Rodante et al., Citation2019; Rogers & Joiner, Citation2016; Sinclair et al., Citation2016; Soloff et al., Citation1994; Verkes et al., Citation1996; Wilson et al., Citation2007) have received the most interest in terms of their relationships with suicidality, possibly due to their direct association with self-injury behaviour through emotional dysregulation (Yen et al., Citation2021). Aggression, a behaviour which is linked to both affective instability and impulsivity has also garnered some attention (Corbitt et al., Citation1996; Ferraz et al., Citation2013; Giegling et al., Citation2009; MacEwan, Citation2012; Sher et al., Citation2016; Yang et al., Citation2022).

Extant research has explored the contributions to suicidality in BPD of certain BPD specific diagnostic criteria, namely interpersonal dysfunction (Brown et al., Citation2002; Chu et al., Citation2017; Muehlenkamp et al., Citation2011; Rogers & Joiner, Citation2016; Sekowski et al., Citation2022; Shafer et al., Citation2020; Soloff & Fabio, Citation2008; Yen et al., Citation2021), emptiness (Brickman et al., Citation2014; Ellison et al., Citation2016; Sekowski et al., Citation2022; Yen et al., Citation2021), and identity disturbance (Brickman et al., Citation2014; Muehlenkamp et al., Citation2011; Sekowski et al., Citation2022; Yen et al., Citation2021). In the latest reporting of the Collaborative Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders, Yen and colleagues found that these three traits were all closely associated with suicidality in BPD at a 10-year follow-up (Yen et al., Citation2021), after not having been significant at the earlier two-year time point (Yen et al., Citation2021). The implication is that interpersonal dysfunction, emptiness, and identity disturbance may be more relevant to suicidality when it is recurrent and part of a chronic presentation. These researchers linked their findings to Gunderson’s proposition that periods of dysphoria in clients with BPD are not difficult to distinguish from MDD, being marked by feelings of emptiness, shame, chronic negative self-image, and a sensitivity to rejection that are not generally present in the latter (J. Gunderson, Citation2011).

Several BPD traits have been reported to predict suicidality in not only BPD but in other diagnoses (emptiness; Ellison et al., Citation2016, identity disturbance; Muehlenkamp et al., Citation2011, interpersonal dysfunction; Muehlenkamp et al., Citation2011; Shafer et al., Citation2020 impulsivity; Rihmer & Benazzi, Citation2010), including depressive disorders (Bowen et al., Citation2015; Ducasse et al., Citation2019; Rajappa et al., Citation2012; Rihmer & Benazzi, Citation2010). However, it has been suggested that certain characteristics of suicidality common across various diagnostic groups are in fact still more prominent in BPD samples (Ducasse et al., Citation2019). Alternatively, the question has been raised as to whether, in some cases, the presence of unidentified comorbid BPD traits in other diagnostic groups moderates relationships between certain factors and suicidality. In 1996, Corbitt and colleagues undertook a small systematic review of 12 papers followed by a cross-sectional correlational study investigating suicidality in MDD. Their review indicated that concurrent depression and personality disorder diagnoses were associated with higher frequencies of suicidality, including lifetime attempts. However, their study found that even when there was no diagnosable personality disorder, the severity of BPD or Cluster B (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000) personality traits was the best predictor of the number of suicide attempts in depression. They concluded that research into the characteristics of suicidality in depression and other diagnoses may be overlooking sub-clinical, undiagnosed BPD traits in participant groups (Corbitt et al., Citation1996).

Past research suggests that though multiple suicide attempts (MSA) are a diagnostic criterion for BPD, they are also not exclusive to this disorder (Forman et al., Citation2004; Rudd et al., Citation1996); previous suicidal behaviour is the strongest predictor of future attempts independent of diagnosis (Bostwick et al., Citation2016). Conversely, Corbitt and colleagues (Corbitt et al., Citation1996) conclusion that undiagnosed BPD traits may be present within other diagnostic participant groups highlights a need for further clarification of these findings. This is congruent with research concluding that each additional BPD criterion increases the frequency of lifetime suicide attempts in depression (Galione & Zimmerman, Citation2010). Interestingly, factors reported to predict MSA in other disorders, are also commonly co-morbid with BPD, including history of trauma (Ball & Links, Citation2009; Marshall et al., Citation2013; Paris & Zweig-Frank, Citation1992; Zlotnick et al., Citation2001), psychiatric illness in the family and/or increased psychopathology and comorbidities (Bandelow et al., Citation2005; Forman et al., Citation2004; Park et al., Citation2020), attachment dysregulation (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Pennel et al., Citation2018), substance use (Beghi et al., Citation2013; Heath et al., Citation2018), poor interpersonal functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Forman et al., Citation2004) and poor global or socio-occupational functioning (Javaras et al., Citation2017; Mehlum et al., Citation1994; Perquier et al., Citation2017). Thus, there remains a lack of clarity around the relationships between characteristics associated with BPD and suicidality in depressive disorders.

In summary, research to date has identified a number of client characteristics, both diagnostic traits and other factors, that are associated with suicidal behaviours in BPD. Although many of these features are also predictive of suicidality in other diagnostic groups such as MDD, where self-injury presentations are episodic and remit with the resolution of a mental health episode, results may be inconclusive; certain BPD traits may have the potential to discriminate chronic suicidality in this group, and provide empirical evidence to support the experiences described by clinicians (Bateman & Krawitz, Citation2013; J. Gunderson, Citation2011; Paris, Citation2004; Sansone, Citation2004; Yen et al., Citation2021). An exploration of experimental studies that compare suicidality in BPD with suicidality in depressive disorders may clarify associated characteristics.

Since Corbitt’s small systematic review in 1996 (Corbitt et al., Citation1996), there has been no review of studies that compare suicidality in BPD with acute suicidality in MDD. Furthermore, incongruencies in results reported over the past 25 years indicate the need for a current review of the literature. It is, for example, unclear whether inconsistent findings relate to differences between single and recurrent suicide attempts, or whether BPD traits strengthen relationships with suicidal behaviour that already exist across other mental disorders. By further elucidating the characteristics of chronic suicidality in BPD, clinical decision-making regarding appropriate management of risk might be improved. Interventions for acute risk in disorders such as MDD prioritise risk aversion, while those for chronic self-injury in BPD recommend acceptance of short-term risk. Employing the former approach when the presentation is chronic may have iatrogenic impacts for the client (Bateman & Krawitz, Citation2013; Coyle et al., Citation2018; J. G. Gunderson & Links, Citation2008; Warrender, Citation2018). Better understanding of the differences between suicidality in BPD and in depressive disorders could reduce the threat of iatrogenesis.

The present review

The current systematic review sought to establish the status of research in this area by examining published studies and unpublished dissertations comparing suicidality in BPD and in depression, that were completed since Corbitt et al’s. (Citation1996) review that compared MDD with personality disorders. This review, however, has evaluated only those studies which compared suicidality in BPD or BPD traits with that in all depressive disorders (DD). Suicidality in DD is utilised here as a representation of acute suicidal thoughts, intent and behaviour. The primary question was: What are the characteristics and traits that distinguish suicidality in BPD from suicidality in depressive disorders? A secondary aim was to establish whether these differences are more likely to be associated with MSA or recurrent suicidal behaviours, compared to single attempts.

Materials & method

Protocol

The quality of reporting and conduct of this systematic review was based on PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews [PRSIMA-ScR] Checklist), and The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklists (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Ma et al., Citation2020).

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the current systematic review included published studies and unpublished dissertations that:

were in English;

search timeframe was from 1996 inclusive (after Corbitt et al., Citation1996) to 9th January 2023;

included adult and/or adolescent participants;

compared suicidal behaviours in BPD with that in at least one DD, with regard to relationships with at least one other factor, or explored relationships between suicidality in DD and BPD diagnostic criteria; studies reporting on samples of BPD and depression with additional comorbidities were only included where BPD and depression were separately measured and analysed.

utilised a structured diagnostic assessment or clinical interview based on DSM IV, 5, or 5-TR criteria with an expert to assess participants for diagnoses.

measured suicidality, as either suicide attempts, ideation, intent, lethality, or parasuicidal gestures.

Exclusion criteria

The current systematic review excluded studies:

that investigated non-suicidal self-injury and not suicidal self-injury behaviours only;

that only included a measure of depression severity and not depression diagnosis;

that only examined neurobiological factors in suicidality;

where suicidality was confounded with BPD or with depression, so that suicidality in BPD and depression could not be compared.

Identification and selection of studies

Studies were identified by searching four (4) databases: PsycINFO, Medline Complete, EMBASE, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. Search terms related to borderline personality disorder (i.e., borderline personality disorder, BPD, borderline), suicidality (i.e., suicid*, deliberate self-injury), depression (major depressive disorder, major depressive episode, MDD, MDE, depressi*), and comparison (contrast, difference, compar*) were combined in each database (a full list of search terms is located in the Appendix). Each article underwent an abstract and title search in order to exclude those which did not relate to the systematic review question. The initial search was undertaken between 6th and 9th July 2020, and two subsequent searches were conducted on 4th November 2021 and 9th January 2023, to identify articles that had been published after the original search.

Two reviewers then independently screened full records for inclusion/exclusion criteria. In the case of discrepancies, the reviewers discussed each article’s eligibility; this occurred for three papers. If consensus was not reached, a third reviewer was consulted; this occurred for one paper.

Data extraction

Data were uniformly extracted from studies regarding database source, authors, title, year of publication, variables on which suicidality in BPD and DD were compared, participant descriptions and exclusion criteria, study setting/s, participant recruitment, measures used, design and analyses, results, and identification of and approach to confounding factors.

Evaluation of the methodological quality of studies

Two methodological quality appraisal tools were used, depending upon study design. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2017a; Ma et al., Citation2020) consists of eight criteria to assess risk of bias; the JBI Checklist for Cohort Studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2017b; Ma et al., Citation2020) comprises 12 criteria. Both tools have Yes/No/Unclear/Not applicable scoring for each item, which was used to establish an overall rating for each study of Good, Fair or Poor quality.

A third independent reviewer undertook a scope quality review of all articles included, and then independently evaluated the quality of 20% of the articles, also using the JBI checklists (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017; Ma et al., Citation2020). In the case of discrepancies, reviewers discussed the outcomes, and a fourth reviewer was consulted.

Synthesis of results

Studies were grouped by whether they operationalised chronic suicidality through recruitment of participants with multiple attempts and/or used frequency of suicide attempts as a variable, as opposed to exploring the presence or absence of at least one suicide attempt. Papers were then organised according to the types of constructs compared between suicidality in BPD and in DD, including interpersonal dysfunction, aggression, anger/hostility, impulsivity, emptiness, identity disturbance, self-injury factors, affective instability, and trauma and life experiences.

Results

Study selection

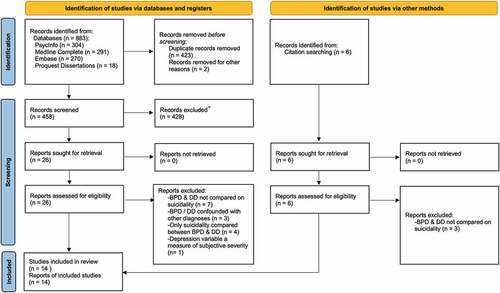

The initial electronic search provided a total of 883 papers, and an additional six were found via article reference lists. A total of 458 papers remained after duplicates and papers not written in English were removed. Title and abstract screening reduced the pool to 32 records. These were assessed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria by two independent reviewers, resulting in 14 papers being included for final review. The second search resulted in 54 additional papers being retrieved, reducing to nine after duplicates were removed; the third search retrieved another 84 papers, decreasing to 16 after duplicates were removed. No papers from the second and third searches satisfied inclusion criteria after full-text review. details the process of study selection for the first search, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (Liberati et al., Citation2009). A qualitative analysis was undertaken due to the heterogenous nature of studies included in this review.

Overview of included studies

provides an overview of the 14 studies that were reviewed, including information about how diagnoses of BPD and DD were compared with respect to suicidality variables, the nature of suicidality variables, other factors included in analyses, outcomes, and quality assessment ratings. Papers are listed according to whether or not chronic suicidality was considered in this review to be operationalised in the design. Participants across the 14 studies totalled N = 5189. Those (50%) classified as operationalising chronic suicidal behaviour either (a) utilised a lifetime frequency of suicidality variable, and/or (b) had a history of suicide attempts as an inclusion criterion for all participants. The remaining papers used an inclusion criterion of at least one suicide attempt, for all or one group of participants, which was not considered by reviewers to represent chronic or recurrent suicidality. In terms of findings relevant to this review, all studies compared BPD with MDD or MDE. One of these studies (Stringer et al., Citation2013) also compared BPD with dysthymia. Fifty percent of studies were conducted in the USA. Over 90% of studies utilised convenience sampling; one was an archival search which used stratified sampling. The majority (70%) of studies recruited adult participants only, 30% utilised adolescent sample, and one paper combined young adults and adults. Papers were evenly split in terms of inpatient and outpatient/community settings.

Table 1. Overview of studies primary analyses.

Quality of evidence assessment

Quality assessment ratings provided in (good, fair, poor) represent outcomes for each paper from The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklists (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017; Ma et al., Citation2020). Twenty-one percent of studies were rated as good, and the remaining 79% as fair quality. Of the latter, the most common inadequacies related to insufficient description of the participant pool and/or study setting (Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Carter et al., Citation2005; Soloff et al., Citation2000; Zeng et al., Citation2016), and sampling. Regarding the latter, over 90% of studies (all but Landry, Citation2011) used convenience sampling, which risks a biased sample and limits generalisability. Other prominent deficiencies comprised: insufficient utilisation of recognised psychometric measures (Amore et al., Citation2014; Carter et al., Citation2005), failure to control for gender (Horesh et al., Citation2003, Citation2009), failure to provide effect sizes (Azcurra, Citation2014), and a small sample size (Kelly et al., Citation2000).

Only one of the 14 studies was longitudinal (Landry, Citation2011) and, therefore, able to claim prediction in their reported relationships. Several used retrospective measures, particularly for lifetime suicide attempt frequency, which allowed some exploration of chronicity, but was subject to recall bias. Most measures employed across various constructs were self-report in nature. However, this is consistent with most cohort studies undertaken with clinical populations in the area of psychology (Demetriou et al., Citation2015), and those utilised in the studies reviewed possessed acceptable reliability and validity for the samples.

Factors compared between suicidality in BPD and in DD

Central to the aim of this review, it was found that across the 14 papers, several factors were reported to significantly discriminate suicidality in BPD from suicidality in DD. Those factors reported by only one paper, or failing to distinguish BPD from DD, are listed in but not discussed here. Findings that indicated a difference between suicidality in BPD and in DD that were reported by more than one paper are reviewed below.

BPD diagnostic traits

A number of BPD diagnostic criteria were investigated across the papers reviewed. Furthermore, some were reported to be more significant in discriminating suicidality in BPD when suicidality represented a chronic risk, operationalised by a measure of MSA.

Factors significant for chronic suicidality

Interpersonal dysfunction, anger/hostility, aggression, and impulsivity were all found to more often discriminate suicidality in BPD and DD when the suicidality factor operationalised chronicity by either employing MSA as a variable, and/or a history of past suicide attempts as inclusion criteria for all participants.

Interpersonal dysfunction

Four papers included some form of interpersonal dysfunction as an independent variable, though only two of these directly compared BPD and DD. Both of these studies reported that interpersonal difficulties discriminated between suicidality in BPD and DD utilising a multiple or recurrent suicide attempts (MSA) factor, and one (Brodsky et al., Citation2006) also used a past history of suicide attempts as an inclusion criterion. The latter reported that MSA and interpersonal triggers to suicide attempts each contributed to a model for BPD comorbid to MDD, but not for MDD alone (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). The second study found that poor social adjustment (measured using a valid and reliable psychometric scale) was more likely to predict MSA in BPD than in MDD (Kelly et al., Citation2000). One of the studies which did not directly compare BPD and DD for interpersonal instability (measured as the criterion on a BPD diagnostic tool) reported that this factor independently predicted the presence of past suicide attempts (versus no suicide attempts) across their whole sample of inpatients with various diagnoses including BPD and DD (Zeng et al., Citation2016). The fourth paper also used the interpersonal instability criterion of a BPD diagnostic tool but found that this variable did not contribute to a final model of MSA in DD (Stringer et al., Citation2013).

Aggression

Eight studies explored the relationship between aggression and suicidality, and 63% of these reported a significant result for this factor. All studies that reported aggression as a discriminator of suicidality in BPD from that in DD utilised a recurrent or chronic suicidality variable, except those that recruited adolescents. One utilised MSA as a regression predictor and only recruited participants with a history of suicidality (Brodsky et al., Citation2006), a second compared repeat versus no repeat suicide attempts in participants with at least one previous attempt (Amore et al., Citation2014), and a third paper used MSA as the outcome variable in regression (Soloff et al., Citation2000). Two studies which found aggression discriminated suicidality in BPD from MDD without using an operationalisation of MSA, investigated adolescents (Azcurra, Citation2014; Horesh et al., Citation2003).

The remaining two studies did not find aggression to discriminate between suicidality in the two diagnostic groups. One of these studies utilised MSA as the suicidality variable in a path analysis, employing retrospective data in participants with a history of suicidality (Chesin, Citation2013). They reported no difference between models for BPD and MDD in terms of the contribution of aggression. This may have been a consequence of their path analysis omitting impulsive aspects of aggression, after the shared variance of impulsivity and aggression was removed, or a function of a predominantly female sample. The remaining paper explored the presence or absence of a past history of suicidal behaviour and found no difference between MDD and comorbid MDD plus BPD suicide attempters on aggression (Keilp et al., Citation2006).

Anger/Hostility

Although several papers included anger and/or hostility as individual constructs, for the purposes of the current review, anger and hostility were reviewed together. Of the six papers that included this variable, two utilised an MSA factor; however, only one of these directly compared BPD and DD on anger/hostility (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). As well as employing MSA as the suicidality variable, this one study recruited only individuals with a past history of suicide attempts. Hostility independently contributed in a regression design to MSA for BPD comorbid with MDD, but not MDD alone (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). The other study that used MSA employed items relating to BPD criteria as predictors and reported that anger and “fights” were significant contributors to MSA in dysthymia (Stringer et al., Citation2013). Though BPD and DD were not directly compared in this design, anger and “fights” were measured by a BPD criterion (from Personality Disorder Questionnaire – Version 4), and every additional BPD criterion was associated with higher levels of MSA in DD. The remaining four papers investigated the relationships between anger/hostility and the presence or absence of suicidal behaviour, rather than MSA specifically. None identified this construct as discriminating BPD from DD (Azcurra, Citation2014; Horesh et al., Citation2003; Keilp et al., Citation2006), or did not compare the diagnoses of this factor (Zeng et al., Citation2016).

Impulsivity

Eight studies included an impulsivity variable, with 50% of these reporting that this factor discriminated suicidality in BPD from that in DD. Two of the latter used an MSA variable and only included adult participants with a history of suicidality, thus employing designs that strongly operationalised recurrent or chronic suicidal behaviour. One used regression with MSA and impulsivity as predictors and diagnostic groups as outcomes (Brodsky et al., Citation2006), and the other completed separate path analyses for MDD and BPD (Chesin, Citation2013). Similar to aggression, the other two papers which reported a relationship between impulsivity and suicidality in BPD but not in MDD did not operationalise MSA, and were focused on adolescents only (Azcurra, Citation2014; Horesh et al., Citation2003).

Of the remaining 50% of papers which did not find significance for impulsivity, two did not directly compare BPD and DD for this factor (Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016). The remaining two which reported that impulsivity was not a good discriminator of suicidality in the two diagnostic groups, used either an MSA variable (Soloff et al., Citation2000) or an inclusion criterion representing a history of suicidality (Keilp et al., Citation2006), but not both. Thus, the latter were not operationalising chronic or recurrent suicidality as strongly as those who obtained significant results.

Emptiness

Two papers included this factor, each utilising individual items from a psychometric assessment of personality disorder to extract BPD criterion variables. Neither study directly compared suicidality in BPD and DD on these traits. In one, emptiness was significant in both a preliminary univariable analysis and in an initial regression model for MSA in DD (MDD and dysthymia), where BPD criteria were used as predictors individually (Stringer et al., Citation2013). However, the latter regression result was obtained when using a broad measure of suicide attempts, and when analyses were repeated with a stricter definition, the number of reported attempts were reduced as a consequence; relationships between all BPD criteria and MSA were therefore lost in the final model. In the second paper, the BPD trait of emptiness was not found to be associated with the presence or absence of suicidality in the entire sample, and BPD and DD were not compared on this factor (Zeng et al., Citation2016).

Identity disturbance

For this factor, no pattern was evident across the papers reviewed relating to the type of suicidality variable used in analyses. Only one study out of three that included variables related to the construct of identity disturbance; a Latent Class analysis (Podlogar et al., Citation2018), compared BPD and DD regarding suicidality and reported a difference in relation to relevant variables. These researchers found that feelings of worthlessness and self-dislike discriminated a high-risk suicidality class, which included BPD but not MDD. Though these factors were represented by items from the Beck Depression Inventory, these authors reported that this high-risk class did not include the vegetative symptoms of MDD (such as issues with sleep, energy and appetite).

The remaining two studies, which did not compare BPD and DD directly for identity disturbance, reported that the latter was not associated with suicidality in their samples. One found that this factor did not contribute to a model of MSA for various diagnoses including MDD and dysthymia (Stringer et al., Citation2013). The second study, which employed a dichotomous presence or absence of a suicidality variable as the regression outcome, also found that identity disturbance did not contribute to a model which included their entire sample comprising BPD, DD, and various other affective and psychotic disorders (Zeng et al., Citation2016).

Self-injury factors

Nine studies claimed that the frequency of lifetime suicide attempts was significantly more associated with the presence of BPD than DD (Amore et al., Citation2014; Azcurra, Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Chesin, Citation2013; Keilp et al., Citation2006; Kelly et al., Citation2000; Soloff et al., Citation2000; Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016). Two of these also reported an increase in suicide attempts across a sample containing DD and other disorders, with each additional BPD trait (Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016). However, this relationship between BPD diagnostic criteria and frequency of attempts is well established in past research (Corbitt et al., Citation1996; Kochanski et al., Citation2018; Rogers & Joiner, Citation2016; Rudd et al., Citation1996; Sher et al., Citation2017; Soloff et al., Citation1994) and was not the primary focus of the current review.

Five other factors relating to self-injury emerged from the review of papers. Two studies examined age-related issues, with one reporting earlier onset of suicide attempts in BPD than in DD, using regression with diagnostic groups as outcomes (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). The second study found that within the group of participants who had a recent suicide attempt, those with comorbid MDD and BPD were younger than those with MDD alone (Amore et al., Citation2014). In terms of suicide attempt planning, one study reported that objective planning was higher for adults with comorbid BPD and MDD than with BPD or MDD alone (Soloff et al., Citation2000), while another found that planning was slightly higher in a group of adolescents with MDD than adolescents with BPD (Azcurra, Citation2014). A history of lethality as well as violence of a recent attempt were both found by one paper to be more closely associated with BPD than with MDD (Soloff et al., Citation2000). Relating to intent, a study of adolescents reported a stronger relationship between suicidal intent and BPD than intent and MDD (Horesh et al., Citation2003), while another paper that explored suicidality in adults found that subjective intent was greater for comorbid BPD and MDD than for BPD alone, despite medical lethality for the same attempt being equivalent (Brodsky et al., Citation2006).

Early onset of psychopathology

One study reported an earlier onset of DD in participants who had comorbid BPD, compared with those without comorbidity or those with MDD comorbid with another personality disorder (Amore et al., Citation2014). The two findings discussed above regarding age-related factors in self-injury are also relevant to the early onset of psychopathology (Amore et al., Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate research undertaken since Corbitt et al’.s review (Corbitt et al., Citation1996) comparing suicidality in BPD and in depressive disorders. The key purpose was to integrate research results that might identify factors that distinguish chronic suicidal behaviour in BPD from suicidality in depression. Papers that made this distinction also reported that recurrent suicidality is more strongly associated with BPD than with DD (Amore et al., Citation2014; Azcurra, Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Chesin, Citation2013; Keilp et al., Citation2006; Kelly et al., Citation2000; Soloff et al., Citation2000; Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016), supporting this review’s utilisation of suicidality in depression to represent an acute self-injury presentation. A primary objective of the review was to support clinical practice by contributing to the assessment and identification of chronic suicidality in BPD, with a view to reducing risk averse practices and iatrogenesis that can occur when clinicians inaccurately formulate this presentation as an acute risk.

While findings should be considered preliminary due to the small number of papers investigating some factors, results are largely consistent with clinical experience and theoretical discussion papers since the 1970s (J. Gunderson, Citation2011; Olin, Citation1976; Paris, Citation2004; Sansone, Citation2004; Schwartz et al., Citation1974), which recognised suicidal behaviour in BPD as a chronic, highly relational phenomenon, often marked by anger. In terms of recurrent suicidality, the present review unequivocally confirmed that high frequency of lifetime suicide attempts is more associated with BPD than DD (Amore et al., Citation2014; Azcurra, Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Chesin, Citation2013; Keilp et al., Citation2006; Kelly et al., Citation2000; Soloff et al., Citation2000; Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016). Though requiring further substantiation, a pattern has emerged in the current review that suggests some factors may be more likely to discriminate suicidality in BPD from other presentations when suicidality is operationalised as chronic and recurrent. Specifically, this was the case for interpersonal dysfunction, aggression, impulsivity, and anger/hostility. However, a chronic or longitudinal lens is needed to further demonstrate this. Furthermore, BPD may be linked with the earlier onset of depressive disorder, and/or earlier suicidal and self-injury behaviour (Amore et al., Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006), and more recent research has replicated these findings (Temes, Citation2021; Tong et al., Citation2021). Exposure to early risk factors, such as childhood abuse experiences and a family history of psychopathology, is also associated with suicide attempts in BPD (Temes, Citation2021).

Interpersonal dysfunction

Consistent with past literature (Brown et al., Citation2002; Sansone, Citation2004), the current findings suggest that interpersonal triggers for suicide attempts may be significantly more common in MSA in BPD than in depression (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). In addition, poor social adjustment may be more strongly associated with MSA in BPD than in depression (Kelly et al., Citation2000). The alternative dimensional model for personality disorder in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) proposed that interpersonal dysfunction is a gateway criterion for personality disorder. It has been proposed that for BPD, precipitants for underlying distress include historical factors such as childhood trauma and loss, as well as temporally proximal interpersonal and intra-personal precipitants (Brooke & Horn, Citation2010).

The current findings are compatible with past research that highlights associations in BPD between suicide attempts and issues in social problem solving (Maurex et al., Citation2010), and more recently between emotional hyper-reactivity and interpersonal triggers or threats (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2021; Sauer et al., Citation2014). Fitzpatrick et al. (Citation2021) argue that destructive behaviours are utilised in BPD as a means of regulating interpersonal needs. Though it appears that relational disturbances may be a risk factor for MSA that is unique to BPD (Zeng et al., Citation2016), a handful of studies have suggested that the relationship between interpersonal difficulties and MSA exists in other diagnostic groups even when BPD is controlled in analyses (Forman et al., Citation2004). However, as the presence of BPD is usually controlled as a full diagnosis, it is possible, as suggested by Corbitt and colleagues (Corbitt et al., Citation1996), that participants with borderline traits sub-clinical to a full diagnosis might exist within other diagnostic samples.

Anger, aggression and impulsivity

The review’s results also suggest that for adults, anger/hostility (Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Stringer et al., Citation2013), aggression (Amore et al., Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Soloff et al., Citation2000), and impulsivity (Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Chesin, Citation2013) might all be better discriminants of BPD when suicidality is chronic and recurrent. Impulsivity has long been associated with suicidal behaviour across a number of diagnostic groups (Boisseau et al., Citation2013; Ducasse et al., Citation2019; Rihmer & Benazzi, Citation2010). However, those studies reviewed here that strongly operationalised suicidality as chronic (via both participant inclusion and frequency of attempts) reported significant differences between BPD and depression for impulsivity (Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Chesin, Citation2013). For adolescents, where a chronic pattern of suicidality has not yet been established, aggression and impulsivity were both found to discriminate between suicide attempts in BPD versus depression, while anger did not (Azcurra, Citation2014; Horesh et al., Citation2003). This may relate to phenomena such as aggression and impulsivity functioning differently for this cohort than for adults (Whelan et al., Citation2012). Alternatively, these behaviours relate to explosive or impetuous acts that are more likely in BPD than in DD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), while anger is an emotional experience common to adolescents, regardless of mental health diagnosis (Lok et al., Citation2018).

Function and lethality

Consistent with clinical practice, the current results suggested that the lethality of self-injury behaviours in BPD may not always coincide with expressed intent. Methods used and lethality of attempts did not differ between BPD and depression (Amore et al., Citation2014; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Soloff et al., Citation2000) and, in a group of adult participants, this was the case despite lower expressed intent in those with BPD (Brodsky et al., Citation2006). This finding was attributed to the contention that those with BPD tend to underestimate or misperceive lethality of their attempts, or rely upon the likelihood of being rescued (Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Stanley et al., Citation2001).

Identity disturbance and emptiness

Though Yen and colleagues reported that identity disturbance and emptiness were closely associated with suicidality in BPD at 10 year follow-up (Yen et al., Citation2021), but not at a 2-year time point (Yen et al., Citation2004), the current findings were not conclusive with regard to either emptiness (Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016) or identity disturbance (Podlogar et al., Citation2018; Stringer et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2016), with only partial support for each. Further research is necessary to shed more light on whether these two traits, which are unique to BPD diagnosis, are also unique to MSA or chronic suicidal presentations in BPD.

Clinical implications

Assessing for a history of recurrent acts of self-injury is a useful means by which to establish whether a current risk presentation is chronic or acute (Rao et al., Citation2017). However, this review suggests that there are other possible indicators that might support clinicians to identify the chronically suicidal client. Suicidal presentations in depression are principally acute in nature, with the DSM 5-TR requiring symptoms, including thoughts of death or suicidality, to represent a marked change from previous functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Conversely, suicidality in BPD is predominantly chronic or recurrent (Rao et al., Citation2017; Yen et al., Citation2021), however can sometimes involve an acute episode of suicidality overlayed upon a pattern of long term, chronic risk (Rao & Broadbear, Citation2019). Risk formulation with a client who is not well known is challenging, a situation where the client with BPD is vulnerable to iatrogenesis if custodial care is implemented when the presenting behaviour is consistent with the individual’s chronic pattern. Similarly, exigent is the clinical discernment of an acute episode of risk in the presence of MDD, in a client with BPD whose pattern of suicidality is usually chronic; here, misplaced risk tolerance may result in suicide completion.

With new BPD clients, a thorough history of self-injury behaviour should be taken in order to discern whether a risk tolerant approach is indicated (Beatson, Citation2010). However, this is not always possible when the client is not well known and is in crisis. Currently, no screening tool exists that might assist with identifying chronic suicidality in BPD. Nonetheless, the current findings suggest a potential starting point for this. Beyond the diagnosis of BPD, the presence of a long term mental health trajectory beginning in adolescence, a propensity for anger, aggression or impulsivity, a history of interpersonal dysfunction, and/or a pattern of high expressed suicide intent with low lethality behaviours, may be markers to which clinicians can attend. In particular, clinical and theoretical wisdom has asserted the interpersonal nature of chronic self-injury risk in BPD (Beatson, Citation2010; J. Gunderson, Citation2011), with clients known to utilise these behaviours sometimes as a means of revenge, as appeals for increased care (McAuliffe et al., Citation2007), or to decrease their own fear and anxiety (Carmel et al., Citation2018). This review synthesises and brings clarity to extant literature, indicating a body of empirical evidence that matches practitioner experience.

The identification of factors that are often associated with chronic suicidality in BPD might increase the likelihood of clinicians discriminating a chronic self-injury pattern where risk tolerance is indicated, or alternatively identifying an episode of acute suicidality in BPD that requires assertive intervention. Improved practice in this area implies a decrease in possible iatrogenic impacts caused by risk-averse intervention around suicidality, and also a potential reduction of the risk of death by suicide in BPD. These findings go some way towards supporting clinical practice in self-injury risk formulation with this diagnostic group.

Limitations

This review has some limitations that impact the capacity to draw strong conclusions. Firstly, not all studies were conducted by independent research teams. Kelly et al. (Citation2000) and Soloff et al. (Citation2000) involved the same research team, as did Brodsky et al. (Citation2006) and Keilp et al. (Citation2006), which may have contributed to the replication of findings that indicated differences between BPD and MDD. Furthermore, Kelly et al. (Citation2000) and Soloff et al. (2002) appeared to utilise the same dataset, though reported upon different factors.

Only one of the reviewed studies utilised a longitudinal design, and so ability to draw assumptions about chronicity and how this might influence the characteristics of suicidality across the lifespan in BPD and depression is limited. Certainly, retrospective measures of lifetime suicide attempts were employed in many cases which established a long-term pattern of self-injury, and some factors were assessed based on self-report of lifetime occurrence. However, based upon Yen and colleague’s reporting of two time points in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (Yen et al., Citation2004, Citation2021), factors associated with suicidality in BPD may differ according to age, or the point in the trajectory of the disorder at which they are measured.

Another limitation is the heterogenous nature of designs used in the papers reviewed, including types of participants and settings, measures utilised, and differing aims and statistical analyses. There was some indication that factors related to suicidality may be different for adolescents than adults, however it was not possible to make strong comparisons here. Some studies recruited inpatients, who were experiencing an acute episode of their disorder, while others investigated clinical community samples. Suicide attempt variables differed in terms of whether participants had had a recent attempt, or were providing a retrospective account, and the concept of chronicity was operationalised sometimes within the participant group and other times just as a lifetime attempt frequency measure. Although most factors were measured by tools with good psychometric qualities, and suited to study design, the capacity to compare across different measures for the same trait was constrained. Furthermore, not all studies had the purpose of comparing BPD and depression on suicidality and other factors, and as such, findings related to the aim of the current review were in some cases extrapolated from designs not conceived for this objective. Another limitation was that some of the factors considered here were only investigated in a handful of studies, also limiting the reliability of conclusions. Finally and importantly, a number of studies may have confounded sub-clinical BPD traits with depression, by only comparing a full BPD diagnosis with the latter.

Future research

The indication that characteristics of suicidality in BPD and depression may especially differ when suicidality is recurrent in nature needs further investigation. It is recommended that future studies strengthen the operationalisation of chronic suicidality by, in addition to measuring lifetime frequency of attempts, targeting or comparing against participant populations that have a history of suicidal behaviour. Different age groups and levels of chronicity could also be contrasted, including looking at both early and later in the lifetime trajectory of different mental disorders. In addition, a range of diagnostic groups could be compared with BPD in regard to suicidality, comprising episodic, acute, and chronic disorders. The current review contrasted BPD with depression only, and did not compare chronic suicidality in BPD with other chronic, or persistent disorders. Furthermore, one area of particular interest that requires further extrapolation in this field of suicidality research is the identification and controlling of subclinical BPD traits within MDD samples. It is possible that samples identified as having depression but not BPD may contain unidentified, undiagnosed BPD features.

Another area for ongoing future study would be to clarify differences between suicidality in adults and adolescents, especially in relation to anger in BPD and depression, and whether this differs for inpatients versus a community sample. Finally, additional support needs to be sought for Yen and colleagues’ conclusions (Yen et al., Citation2004, Citation2021) that BPD specific criteria of frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, emptiness, and identity disturbance are distinctly related to suicidality in BPD when suicide attempts are measured prospectively over a number of years, but not at a younger age.

Summary & conclusion

This systematic scoping review offers preliminary evidence that although previous research has shown that some factors are common to suicidality in different diagnostic groups (Ducasse et al., Citation2019), it may be that these characteristics are still strongest for recurrent suicide attempts in BPD. Findings indicated that the presence of interpersonal dysfunction, impulsivity, aggression, and anger/hostility in adults may all discriminate chronic suicidality in BPD from suicidality in depression, but not when investigating only single suicide attempts in isolation.

The review has highlighted the chronic and developmental trajectory of BPD, illustrating that suicidality in this client group, and not in depression, may be associated with the early onset of depression and suicidal behaviour. The relationship between suicidal behaviour and BPD traits seem reciprocal in terms of their mutual development, with the association increasing with more suicide attempts (Boisseau et al., Citation2013; Brodsky et al., Citation2006; Soloff et al., Citation2000; Stringer et al., Citation2013). The review also suggests that lethality of suicide attempts may not differ between individuals with BPD and depression, however those with BPD may report higher levels of intent no matter what the medical risk. In order to clarify clinician experience with research outcomes, it is important that future studies expand upon the current limited evidence base regarding chronic self-injury in BPD, and on how it can be clearly elucidated and identified as a different phenomenon from acute suicidal presentations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03520100096046

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Amore, M., Innamorati, M., DiVittorio, C., Weinberg, I., Turecki, G., Sher, L., Paris, J., Girardi, P., & Pompili, M. (2014). Suicide attempts in major depressed patients with personality disorder. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour, 44(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12059

- Andrewes, H. E., Hulbert, C., Cotton, S. M., Betts, J., & Chanen, A. (2019). Relationships between the frequency and severity of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in youth with borderline personality disorder. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(2), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12461

- Azcurra, D. S. (2014). Differential role of impulsivity in adolescents’ suicidal behaviour with borderline personality disorder and major depression. In M. C. Olmstead (Ed.), Psychology of impulsivity: New research (pp. 49–60). Nova Science Publishers.

- Ball, J. S. & Links, P. S. (2009). Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports, 11(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-009-0010-4

- Bandelow, B., Krause, J., Wedeking, D., Boocks, A., Hajak, G., & Ruther, E. (2005). Early traumatic life events, parental attitudes, family history, and birth risk factors in patients with borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Psychiatry Research, 134(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2003.07.008

- Bateman, A. & Krawitz, R. (2013). Borderline personality disorder: An evidence-based guide for generalist mental health professionals. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.113.044677

- Beatson, J. (2010). Self-harm and suicidality in borderline personality disorder. In J. Beatson, S. Rao, & C. Watson (Eds.), Borderline personality disorder: Towards effective treatment (pp. 167–191). Australian Postgraduate Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2016-0043

- Beghi, M., Rosenbaum, J. F., Cerri, C., & Cornaggia, C. M. (2013). Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: A literature review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S40213

- Black, D. W., Blum, N., Pfohl, B., & Hale, N. (2004). Suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(3), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.18.3.226.35445

- Boisseau, C. L., Yen, S., Markowitz, J. C., Grilo, C. M., Sanislow, C. A., Shea, M. T., Zanarini, M. C., Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Morey, L. C., & McGlashan, T. H. (2013). Individuals with single versus multiple suicide attempts over 10 years of prospective follow-up. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(3), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.062

- Bostwick, J. M., Pabbati, C., Geske, J. R., & McKean, A. J. (2016). Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: Even more lethal than we knew. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1094–1100. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854

- Bourke, J., Murphy, A., Flynn, D., Kells, M., Joyce, M., & Hurley, J. (2021). Borderline personality disorder: Resource utilisation costs in Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(3), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2018.30

- Bowen, R., Balbuena, L., Peters, E. M., Leuschen-Mewis, C., & Baetz, M. (2015). The relationship between mood instability and suicidal thoughts. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004474

- Brickman, L. J., Ammerman, B. A., Look, A. E., Berman, M. E., & McCloskey, M. S. (2014). The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a college sample. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1(14), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-6673-1-14

- Brodsky, B. S., Groves, S. A., Oquendo, M. A., Mann, J. J., & Stanley, B. (2006). Interpersonal precipitants and suicide attempts in borderline personality disorder. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour, 36(3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.313

- Brodsky, B. S., Malone, K. M., Ellis, S. P., Dulit, R. A., & Mann, J. J. (1997). Characteristics of borderline personality disorder associated with suicidal behaviour. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(12), 1715–1719. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.12.1715

- Brooke, S. & Horn, N. (2010). The meaning of self-injury and overdosing amongst women fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for ‘borderline personality disorder’. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 83(2), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608309X468211

- Brown, M. Z., Comtois, K. A., & Linehan, M. M. (2002). Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.198

- Carmel, A., Templeton, E., Sorenson, S. M., & Logvinenko, E. (2018). Using the Linehan Assessment and Management protocol with a chronically suicidal patient: A case report. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 25(4), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.02.001

- Carter, G. L., Lewin, T. J., Stoney, C., & Whyte, I. M. (2005). Clinical management for hospital-treated deliberate self-poisoning: Comparisons between patients with major depression and borderline personality disorder. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(4), 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2005.01564.x

- Chesin. (2013) Pathways to high-lethality suicide attempts. (Publication No. 1283150245) [Doctoral dissertiation, City University of New York]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. http://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/pathways-high-lethality-suicide-attempts/docview/1283150245/se-2

- Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Tucker, R. P., Hagan, C. R., Rogers, M. L., Podlogar, M. C., Chiurliza, B., Ringer, F. B., Michaels, M. S., Patros, C. H. G., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

- Corbitt, E. M., Malone, K. M., Hass, G. L., & Mann, J. J. (1996). Suicidal behaviour in patients with major depression and comorbid personality disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 39(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00023-7

- Coyle, T. N., Shaver, J. A., & Linehan, M. M. (2018). On the potential for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric crisis services: The example of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for adult women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000275

- Demetriou, C., Ozer, B. U., & Essau, C. A. (2015). Self-report questionnaires. In The encyclopedia of clinical psychology. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp507

- Ducasse, D., Lopez-Castroman, J., Dassa, D., Brand-Arpon, V., Dupuy-Maurin, K., Lacourt, L., Guillaume, S., Courtet, P., & Olie, E. (2019). Exploring the boundaries between borderline personality disorder and suicidal behaviour disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 270(8), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-00980-8

- Ellison, W. D., Rosenstein, L., Chelminski, I., Dalrymple, K., & Zimmerman, M. (2016). The clinical significance of single features of borderline personality disorder: Anger, affective instability, impulsivity, and chronic emptiness in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_193

- Ferraz, L., Portella, M. J., Vallez, M., Gutierrez, F., Martin-Blanco, A., Martin-Santos, R., & Subira, S. (2013). Hostility and childhood sexual abuse as predictors of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 980–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.004

- Fitzpatrick, S., Liebman, R. E., & Monson, C. M. (2021). The borderline interpersonal-affective systems (BIAS) model: Extending understanding of the interpersonal context of borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 84, Article 101983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101983

- Forman, E. M., Berk, M. S., Henriques, G. R., Brown, G. K., & Beck, A. T. (2004). History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioural marker of psychopathology. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(3), 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437

- Galione, J. & Zimmerman, M. (2010). A comparison of depressed patients with and without borderline personality disorder: Implications for interpreting studies of the validitiy of the bipolar system. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(6), 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.763

- Giegling, I., Olgiati, P., Hartmann, A. M., Calati, R., Moller, H., Rujescu, D., & Serretti, A. (2009). Personality and attempted suicide: Analysis of anger, aggression and impulsivity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(16), 1262–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.04.013

- Goodman, M., Roiff, T., Oakes, A. H., & Paris, J. (2012). Suicidal risk and management in borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry, 14(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-011-0249-4

- Gunderson, J. (2011). Clinical practice: Borderline personality disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 364(21), 2037–2042. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1007358

- Gunderson, J. G. & Links, P. S. (2008). Borderline personality disorder: A clinical guide (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0790966700000562

- Hastrup, L. H., Jennum, P., Ibsen, R., Kjellbert, J., & Simonsen, E. (2019). Societal costs of borderline personality disorders: A matched-controlled nationwide study of patients and spouses. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 140(5), 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13094

- Hawton, K., Casañas i Comabella, C., Haw, C., & Saunders, K. (2013). Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

- Heath, L. M., Laporte, L., Paris, J., Hamdullahpur, K., & Gill, K. J. (2018). Substance misuse is associated with increased psychiatric severity among treatment-seeking individuals with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 32(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2017_31_307

- Ho, A. O. (2014). Suicide: Rationality and Responsibility for Life. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(3), 141–147. doi:10.1177/070674371405900305

- Horesh, N., Nachshoni, T., Wolmer, L., & Toren, P. (2009). A comparison of life events in suicial and nonsuicidal adolescents and young adults with major depression and borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(6), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.01.006

- Horesh, N., Orbach, I., Gothelf, D., Efrati, M., & Apter, A. (2003). Comparison of the suicidal behaviour of adolescent inpatients with borderline personality disorder and major depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(9), 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000087184.56009.61

- Javaras, K. N., Zanarini, M. C., Hudson, J. I., Greenfield, S. F., & Gunderson, J. G. (2017). Functional outcomes in community-based adults with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 89, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.010

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017a). Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. Joanna Briggs Institute Database. http://joannabriggs.org/

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017b). Checklist for cohort studies. Joanna Briggs Institute Database.

- Keilp, J. G., Gorlyn, M., Oquendo, M. A., Brodsky, B., Ellis, S. P., Stanley, B., & Mann, J. J. (2006). Aggressiveness, not impulsiveness or hostility, distinguishes suicide attempters with major depression. Psychological Medicine, 36(12), 1779–1788. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008725

- Kelly, T. M., Soloff, P. H., Lynch, K. G., Hass, G. L., & Mann, J. J. (2000). Recent life events, social adjustment, and suicide attempts in patients with major depression and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 14(4), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.316

- Kochanski, K. M., Lee-Tauler, S. Y., Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Perera, K. U., Novak, L., LaCroix, J. M., Lento, R. M., & Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M. (2018). Single versus multiple suicide attempts: A prospective examination of psychiatric factors and wish to die/wish to live index among military and civilian psychiatrically admitted patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders, 206(8), 657–661. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000851

- Krawitz, R. & Batcheler, M. (2006). Borderline personality disorder: A pilot survey about clinician views on defensive practice. Australasian Psychiatry, 14(3), 320–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02297.x

- Landry, E. C. (2011) Internalizing and externalizing pathways to suicidality in abused and neglected children grown up. (Publication No. 907103654) [Doctoral dissertation, City University of New York]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. http://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/internalizing-externalizing-pathways-suicidality/docview/907103654/se-2?accountid=10445

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

- Links, P. S., Eynan, R., Heisel, M. J., Barr, A., Korzekwa, M., McMain, S., & Ball, J. S. (2007). Affective instability and suicidal ideation and behaviour in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2007.21.1.72

- Lok, N., Bademli, K., & Canbaz, M. (2018). The effects of anger management education on adolescents’ manner of displaying anger and self-esteem: A randomized control trial. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2017.10.010

- Ma, L., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X. (2020). Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Military Medical Research, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8

- MacEwan, G. (2012) Borderline personality disorder and object relations: Predicting self-injurious and suicidal behaviours. (Publication No. 910886003) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Massechusetts Amherst]. ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis Global. http://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/borderline-personality-disorder-object-relations/docview/910886003/se-2?accountid=10445

- Marshall, B. D. L., Galea, S., Wood, E., & Kerr, T. (2013). Longitudinal associations between types of childhood trauma and suicidal behaviour among substance users: A cohort study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), e69–75. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301257

- Maurex, L., Lekander, M., Nilsonne, A., Anderson, E. E., Asberg, M., & Ohman, R. (2010). Social problem solving, autobiographical memory, trauma, and depression in women with borderline personality disorder and a history of suicide attempts. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X454831

- McAuliffe, C., Arensman, E., Keeley, H. S., Corcoran, P., & Fitzgerald, A. P. (2007). Motives and suicide intent underlying hospital treated deliberate self-harm and their association with repetition. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour, 37(4), 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.4.397

- McGlashan, T. H., Grilo, C. M., Skodol, A. E., Gundersen, J. G., Shea, M. T., Morey, L. C., Zanarini, M. C., & Stout, R. L. (2000). The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(4), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x

- Mehlum, L., Friis, S., Vaglum, P., & Karterud, S. (1994). The longitudinal pattern of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: A prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01567.x

- Muehlenkamp, J., Ertelt, T. W., Miller, A. L., & Claes, L. (2011). Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x