?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper presents the results of a survey carried out in 2017. The research was focused on the behaviour of Polish local and regional formal institutions (L.G.U.s) in support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship. The main aim was to determine which institutions are crucial for the support of the development of entrepreneurship, but, more importantly, to find why some L.G.U.s obeyed the rules of the entrepreneurship game even if the state monitoring and enforcement mechanisms were lacking. Statistical tools of correlation analysis and factor analysis were used in the research. The factor analysis added empirical evidence on the discussion on how L.G.U.s may affect development of entrepreneurship. Based on the statistically processed data obtained from research, the authors came to the conclusion that geographic location, political power, level of unemployment, size of the territory or level of debt had no impact on the behaviour of L.G.U.s in their support of the development of entrepreneurship. What mattered for the support of entrepreneurship by L.G.U.s was the model of management, type of L.G.U., and the number of enterprises within the territory governed by L.G.U.s. Moreover, only provinces fully succeeded in supporting the development of entrepreneurship, while rural municipalities failed.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship plays a significant role in the process of the socio-economic development of economies (Williams, Vorley, & Williams, Citation2017), especially in countries at the intermediate stage of development (such as Central and East European countries, hereinafter C.E.E.C.s) that want to narrow the distance that separates them from world leaders. Moreover, entrepreneurship has been a key force of economic growth at national level (Acs, Desai, & Hessels, Citation2008; Audretsch & Thurik, Citation2001; Baumol, Citation1990) and at the regional level (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2016). However, not all entrepreneurship leads to growth. Entrepreneurship may be productive, unproductive and destructive (Baumol, Citation1990; Sautet, Citation2013), mostly because of market failures (Akerlof & Shiller, Citation2015). To overcome these market failures the concept of ‘institutions’ may be used to understand better the nature of the entrepreneurship context (Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). Institutions matter for the development of entrepreneurship because they reduce uncertainty, information and transaction costs (Arrow, Citation1969; North, Citation1990; Williamson, Citation1979), or provide conditions for the development of economic activity and the stimulation of entrepreneurship (Baumol, Litan, & Schramm, Citation2009; North, Citation1990). Institutions also matter for regional and local development (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013), as well as for the development of regional and local entrepreneurship (Wołowiec & Skica, Citation2013). Furthermore, local government units (hereinafter L.G.U.s, understood as local and regional formal institutions) became responsible for the dynamic growth of local and regional entrepreneurial activity following the process of decentralisation that occurred in European countries (Skica, Bem, & Daszyńska-Żygadło, Citation2013).

The number of studies on the relation between institutions and entrepreneurship is growing rapidly, but scholars focus mainly on: (i) the impact of institutions on the entrepreneurship rate or type; (ii) institutional barriers; (iii) impact of entrepreneurship on institutional change; (iv) institutional asymmetry; or (v) the impact of the institutional environment on productive, unproductive or destructive entrepreneurship (see, for example, Audretsch, Keilbach, & Lehmann, Citation2006; Estrin & Mickiewicz, Citation2010; Levie, Autio, Acs, & Hart, Citation2014; Williams & Vorley, Citation2015; Williams et al., Citation2017). Moreover, scholars have proved that institutional support has a crucial influence on entrepreneurship activity (Baumol, Citation1990; Minniti & Lévesque, Citation2008; Shane, Citation2009; Williams & Shahid, Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2017). Formal institutions within a country or a region define the entrepreneurial capacity of nations (North, Citation1990). However, scholars have also highlighted that not only formal institutions such as the legal environment or L.G.U., but also informal institutions such as culture, tradition and history play a vital role for entrepreneurial success (Baumol et al., Citation2009; Huggins & Thompson, Citation2016). Williams et al. (Citation2017) argue that the most important factor for the development of entrepreneurship is the interplay between formal and informal institutions within a country or a region. Moreover, entrepreneurial activity will be fostered when formal and informal institutions complement each other and entrepreneurial activity is stymied where there is asymmetry between formal and informal institutions (Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). But is it possible that some formal institutions are able to use the mechanism of self-enforcement in order to foster ‘productive’ entrepreneurial activity, even in the asymmetrical situation between formal and informal institutions as exists in C.E.E.C.s? According to the authors’ best knowledge, there is no similar research which examines the exogenous and endogenous factors that play a crucial role in the self-enforcement mechanism of L.G.U.s that facilitate change of their behaviour towards entrepreneurship support. For policy-makers, especially from transition economies such as C.E.E.C.s, the actual challenge is to create a favourable institutional environment in which a self-enforcement mechanism is used by institutions in order to change, modify or strengthen their behaviour towards ‘productive’ entrepreneurship support.

This article advances institutional research through the development of a better understanding of institutional behaviour at local and regional levels by focusing on the endogenous and exogenous factors that matter for the self-enforcement mechanism of L.G.U.s which were externalised by support of local and regional entrepreneurship. This article, therefore, aims not only at determining which institutions are crucial for the support of the development of entrepreneurship, but, more importantly, at finding why some L.G.U.s obeyed the rules of the entrepreneurship game (regulations and government guidelines for the development of entrepreneurial activities) even if the state monitoring and enforcement mechanisms were lacking. We deliberately chose Poland as an example of a C.E.E.C. We believe that the particular pattern of the self-enforcement mechanism of institutional behaviour identified in Poland is relevant not only for C.E.E.C.s, but also for other countries at the intermediate development stage in Africa, Asia and Latin America. We look at entrepreneurship from the region-wide perspective, which allows us to focus on a range of regulations, L.G.U.s, as well as socio-economic variables.

2. Research of institutions’ behaviour in their support of local and regional entrepreneurship

Institutional theory may be an insight into understanding the influence of institutions’ behaviour on entrepreneurship. Moreover, according to theories of entrepreneurship, institutions influence: (i) the quality of entrepreneurship activities by directing them to productive, unproductive or destructive initiatives (Baumol, Citation1990); (ii) entrepreneurial attitudes to set up a new business and to become an entrepreneur (Estrin & Mickiewicz, Citation2010; North, Citation1994) driven by opportunity or necessity (Fuentelsaz, González, Maícas, & Montero, Citation2015); (iii) the type of new ventures (Minniti & Lévesque, Citation2008); (iv) the level of entrepreneurship (Acs et al., Citation2008); as well as (v) economic prosperity by facilitating entrepreneurship, or economic stagnation by hindering entrepreneurship (Holcombe, Citation2015). Furthermore, institutions should eliminate market failures and create a supportive context for the development of entrepreneurship (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2015).

Although entrepreneurship activity has often been the subject of research, until now not one definition of entrepreneurship has commonly been accepted by scholars. In the literature, entrepreneurship is defined as: (i) activity based on taking advantage of opportunities and risks (Cantillon, Citation1755); (ii) moving resources from a lower capacity area to a higher capacity area by entrepreneurs (Say, Citation1800); (iii) profits in exchange for uncertainty and risk (Knight, Citation1921); and (iv) introduction of new products, services, materials, production methods, markets or form of organisation (Schumpeter, Citation1934). In our research we understand entrepreneurship to be a process of using opportunities (created by institutions) to introduce new products, services or markets (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000, p. 219).

The importance of institutions for entrepreneurship development at national as well as regional and local levels has been widely discussed in the literature in recent years, from the theoretical (see, for example, Baumol, Citation1990; North, Citation1990; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation2000) and empirical perspectives (see, for example, Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2015; Holmes, Miller, Hitt, & Salmador, Citation2013). Not only institutions but also institutional context matter for the development of entrepreneurship (Acs et al., Citation2008; Boettke & Coyne, Citation2007; Williams & Shahid, Citation2016). Scholars have highlighted that entrepreneurship is a leading force of economic development through employment, innovation, or spillover of knowledge (Baumol, Citation2002; Schumpeter, Citation1934; Wennekers & Thurik, Citation1999). The European Commission (E.C.) as well as the European Parliament also noticed the relationship between institutional support of entrepreneurship development and economic growth (see, for example, the Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan). The support of entrepreneurship, the harmonious development of all European Union (E.U.) member states, as well as reducing disparities between the regional level of development became a priority for the E.C. (Treaty on the functioning of the European Union).

Institutions matter (Arrow, Citation1969; Coase, Citation1937, Citation1960; North, Citation1990, Citation1994; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation1979). North (Citation1990) divided institutions as: formal institutions (formal rules, law and constitutions) and informal institutions (constraints, customs, norms). Later on North (Citation1994) as well as Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (Citation2005, pp. 386–387) make a further distinction between economic institutions (‘determine the incentives of and the constraints on economic actors, and shape economic outcomes’) and political institutions (‘allocate de jure political power’). On the other hand, Hodgson (Citation2006, p. 13) added social institutions (‘social rule-system’). Meanwhile, in the literature there is a debate on which institutions (political, economic, legal, social) matter for economic development at the national level (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, Citation2001; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, Citation2008; Williamson, Citation2009). However, until now, according to the authors’ best knowledge, nobody has examined which institutions matter at local and regional levels. The enforcement mechanisms of L.G.U.s also matter, because when weak they may strengthen ‘the grey economy’ or lead to unproductive entrepreneurship (Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland, & Sirmon, Citation2009). However, there is a lack of knowledge concerning the exogenous and endogenous factors which have an influence on the self-enforcement mechanisms of institutions’ behaviour in order to support the development of entrepreneurship. We consider this paper a contribution to filling these gaps.

2.1. Model of management

The research conducted by Voigt (Citation2013) emphasises that scholars are able to observe only the behaviour of the institutions instead of their preferences. The institutions’ behaviour may depend on the adopted model of public administration. The traditional model of public administration is based on the Weberian model of bureaucracy: rule-of-law-oriented, meritocratic, unpolitical, impersonal, centralised, hierarchical, and professionalised with technical rationalisation (Sager & Rosser, Citation2009). Moreover, some scholars highlight the importance of the Weberian model of bureaucracy, especially for developing economies, in order to spur a country’s or a region’s development (Evans & Rauch, Citation2000). On the other hand, the Public Choice research of bureaucracy stresses that boreoarctic structures lead to inefficient use of resources, unnecessary expenditure, or permanent overproduction of public services (Tullock, Citation1965). Other scholars argue that the traditional Weberian model of bureaucracy is inefficient and should be replaced by the New Public Management (N.P.M.) model. The N.P.M. model improves the efficiency and quality of public services by including more participation of citizens as well as entrepreneurs in the management process, flexibility, internal deregulation, and the use of the market mechanism externally (Peters, Citation2001). Nowadays, L.G.U.s may choose between different models of management, such as: (i) model of public administration; (ii) model of N.P.M.; (iii) model of public co-management; (iv) model of new public services; (v) model of innovative management; (vi) model of relationships management; (vii) model of management by aims; or (viii) model of management by quality. In order to examine the impact of the model of management on institutions’ behaviour towards the support of entrepreneurship the following hypothesis was introduced:

H1: The behaviour of L.G.U.s towards the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship depended on the model of management of L.G.U.s.

2.2. Location and level of debt

It is generally acknowledged that institutions at the national level provide the foundation for regional and local entrepreneurship. The region is the most important context for entrepreneurship (Karlsson & Dalherg, 2003), but also for institutions (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). Location matters for entrepreneurship (see, for example, Krugman, Citation1991) and should also matter for the behaviour of L.G.U.s. Over recent years many scientific papers have examined the impact of institutions on regional or place-based development (Acemoglu et al., Citation2005; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). However, the opposite situation is also very important. Scholars have proved the impact of informal institutions such as place-based culture, customs or traditions on formal institutions’ behaviour (Holmes et al., Citation2013; Huggins & Thompson, Citation2016). Moreover, differences of location such as geography, climate or size of the territory also have an impact on institutions’ behaviour (Acemoglu et al., Citation2005).

Institutions’ behaviour towards support of entrepreneurship may also depend on the level of funding. Previous research on L.G.U. debts in transition economies has shown that debt has a positive impact on ‘the modernisation of the local economies and job creations’ (Dafflon & Beer-Toth, Citation2009, p. 305). So formal institutions with debts should be much more eager to support the development of entrepreneurship. In order to examine the impact of location and level of debt on institutions’ behaviour towards the support of entrepreneurship the following hypothesis was introduced:

H2: The behaviour of L.G.U.s in the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship depended on the location and level of debt of L.G.U.s.

2.3. Type of institution and the number of enterprises

Institutions’ behaviour towards the support of entrepreneurship may also depend on the type of institution. In 1985 the member states of the Council of Europe (C.o.E.) introduced the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The C.o.E. was convinced that the existence of local institutions with responsibilities, resources and with a close relationship with citizens would provide more effective administration, and as a consequence accelerate the development of local and regional economies. After transformation C.E.E.C.s also decided to decentralise power and reinforce local self-government units. Unfortunately, C.E.E.C.s did not introduce an effective enforcement mechanism with sanctions to guarantee that L.G.U.s would support the development of entrepreneurship in order to reduce inequalities and accelerate regional development. In the E.U., L.G.U.s include: municipalities, districts and provinces. Municipalities in the E.U. outnumber other regional institutions. We may have rural municipalities (the most numerous), urban municipalities and urban–rural municipalities, as well as cities with district rights. L.G.U.s differ between each other due to tradition, customs, history, the size of the territory, level of economic development, resources or responsibilities (Koellinger & Thurik, Citation2012). However, a certain pattern of institutional behaviour identified in Poland should be relevant for all of the C.E.E.C.s, as well as for other countries at the intermediate development stage in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

It is acknowledged that institutions influence regional variation in firm birth rates. The research conducted by Fritsch and Storey (Citation2014) on regional new business formation stressed the role of both formal institutions and informal institutions such as social capital and a culture of entrepreneurship. However, the opposite situation is also important. The number of enterprises in a territory of local government units may also stimulate institutions’ behaviour towards the support or non-support of the development of entrepreneurship. In order to examine the impact of the type of institution and the number of enterprises on institutions’ behaviour towards the support of entrepreneurship the following hypothesis was introduced:

H3: The behaviour of L.G.U.s in the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship depended on the type of local formal institution and the number of enterprises in the territory governed by L.G.U.s.

3. Research and methods

To achieve the objective of the paper empirical research on a representative sample of L.G.U.s was conducted, and data were statistically processed and interpreted. The research was carried out in summer and autumn 2017. Data were acquired using a survey with quantitative and qualitative research questions in the questionnaire, which was sent to n = 3388 formal institutions in Poland. Unfortunately, the response rate from formal institutions was only 19.24% (n = 652). Moreover, due to the very low level of response (5%) from formal institutions of central government the representative fraction could only be drawn from the L.G.U.s. The collected data covered the characteristics of L.G.U.s, such as: the number of actions that support entrepreneurial development, cooperation with informal institutions, number of actions undertaken to support fair competition, model of management, administration level, type of local government unit, region, unemployment rate, number of enterprises by 10,000 citizens, size of territory, income and expenses per capita, level of debt, and recent change in the position of the mayor, president or district governor. Furthermore, due to the problems with missing data, instead of the imputation procedure the size of the sample was reduced to n = 211 for L.G.U.s with a 5% materiality level and 6.5% maximum error (2SE). After reduction the sample was randomly distributed because 82.99% of the sample comprised municipalities (in population 85.99%), 17% of the sample were districts and cities with district rights (in population 14%), and 0.01% of the sample were provinces (in population 0.01%). The sample was considered representative for all L.G.U.s in Poland.

Second, hereafter the authors define the local and regional formal institutions as local and regional regulations which established the rules of the ‘local and regional economic activity game’ in Poland, as well as L.G.U.s who were responsible for ‘the play of local and regional economic activity game in Poland’.

Third, the behaviour of L.G.U.s was considered the dependent variable in the model (BFLI), and may have been observed by the number of actions undertaken yearly by these institutions in the support of the above-mentioned development.

The independent variables were the following: (i) model of management of L.G.U.s (MMFI); (ii) change of political power in position of mayor, president, district governor or province marshal (CPP); (iii) size of the territory (ST); (iv) type of L.G.U. (TLGU); (v) macro-regions (REG); (vi) provinces (REG II); (vii) unemployment rate (UR); (viii) number of enterprises (NE); and (ix) debt of L.G.U. per capita (LGUD) (see the Appendix).

The acquired data were statistically evaluated. Dependences among the selected data were analysed using internal and cross-correlation. Following the correlation check between dependent and independent variables, it was found that there was no correlation between institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of entrepreneurship and the change of political power in either position (CPP), no correlation with location (province, REG II), and no correlation with the unemployment rate in the governed territory (UR), as well as with size of the territory (ST) (see ). Significant statistical correlations were, however, found between institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of entrepreneurship and: the type of L.G.U. (TLGU), the number of enterprises in the territory of L.G.U. (NE), the model of management (all at the 0.01 level), macro-region (REG), and the level of debt (at the level of 0.05). The strength of the correlation were very weak for independent variables as REG, LGUD or MMFI (bellow 0.2) and weak for NE or TLGU (from 0.27 to 0.35).

Table 1. Correlation.

Furthermore, according to 84.4% of L.G.U.s, no informal institutions functioned in their environment. Moreover, all L.G.U.s that recognised and cooperated with informal institutions (11.8% of respondents) understood informal institutions as local action groups that supported the development of local and regional entrepreneurship, rather than a custom, a value, or a norm. The interplay between formal and informal institutions depends on the institutional framework (De Soto, Citation2000). Because of the weak institutional framework in Poland, according to most cited institutional indices, such as the Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017 of the World Bank Group or the Global Competitiveness Index 2017–2018 of the World Economic Forum, and the very low level of trust according to the European Social Survey Citation2014, informal institutions did not complement or substitute the weak Polish formal institutions.

Fourth, due to the correlation among independent variables, the relationship between the dependent variable with each of the independent variables was tested separately. The empirical model was synthesised in the following equation:

where:

BFLIi – behaviour of L.G.U.s for supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship in Poland;

i = L.G.U.;

Qn = TLGU (Q1), REG (Q2), NE (Q3), LGUD (Q4), MMFI (Q5);

a1; a2; a3; a4; a5 designate the factors that affect the behaviour of L.G.U.s for supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship other than Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5;

b1; b2; b3; b4; b5 measure the change in the behaviour of L.G.U.s for supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship due to changes in Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5;

Ɛni designate the error terms or the gap between the behaviour of L.G.U.s for supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship observed, and those estimated for a given values of Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5.

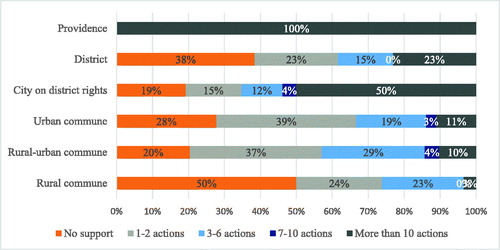

Statistical results (see ) showed that actions undertaken by L.G.U.s in the support of the development of entrepreneurship varied between no support and three to six actions, with a concentration around the median of one to two actions. These characteristics indicated that the distribution of the number of actions undertaken by L.G.U.s in the support of the development of entrepreneurship was not symmetrical.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Because the assumption of normal distribution has not been proven by Kolmogrov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, in order to analyse the data non-parametric tests were employed. Statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistic Program Version 24. Both Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon W tests were used. The selected test of significance of differences allowed us to verify the null hypothesis against the alternative hypothesis:

and against the alternative hypothesis:

where:

BFLIA – dependent variable determined by a given factor in a group supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship;

BFLIB – dependent variable determined by a given factor in a group not supporting the development of local and regional entrepreneurship.

If the significance level was greater than or equal to α = 0.05, there was no reason to reject H0. However, when the α value was less than 0.05 the null hypothesis was rejected.

Finally, we focused only on the local and regional levels of a single country, which was Poland. Our results may not be representative for regions of ‘Western’ member states of the E.U. (i.e., Germany, Sweden, Denmark, France, Spain or the United Kingdom) which, according to the European Quality of Government Index 2017, had much stronger regional institutions than those from C.E.E.C., just after the transition period and decentralisation process. For example, regions from, France (from 0.3 to 1.1), Germany (from 0.3 to more than 1.1), Sweden and Denmark (more than 1.1), and the United Kingdom (from 0.7 to more than 1.1) were all above the E.U. average. By comparison, regions from C.E.E.C.s (except Estonia and one region in the Czech Republic), as well as Greece, Cyprus and Italy were all below the E.U. average. Regions in countries such as Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary were below the E.U. average, from –0.5 to more then –1.2, and Poland, from –0.3 to –0.7. As a result, future research will be required to ensure the wider international applicability of the research.

4. Evaluation of acquired data and discussion

The results are summarised in and . Generally, the hypotheses on the relationship between the institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of entrepreneurship and the model of management, the type of L.G.U., and the number of enterprises were validated (α < 0.05). However, the hypothesis on the relationship between the institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of entrepreneurship and the location (macro-region) as well as the level of debt was not validated (α > 0.05).

Table 3. Mann–Whitney test.

Table 4. Test statistics.

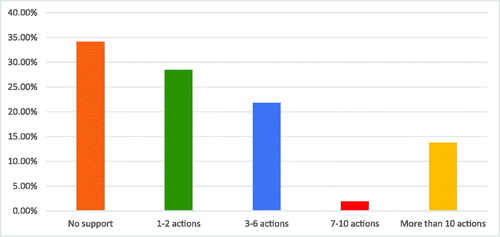

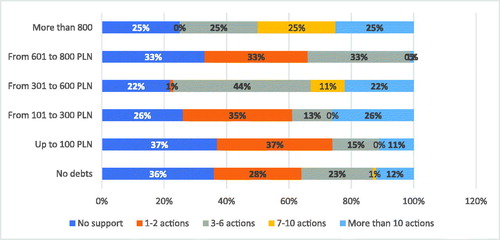

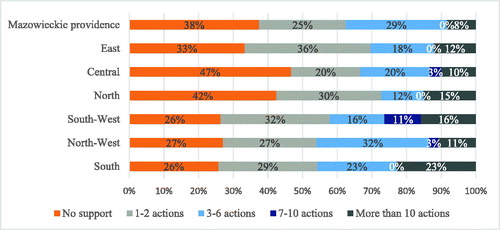

Entrepreneurship is generally acknowledged to be a key force of economic growth, and that is why formal institutions undertake action to support the development of entrepreneurship in order to stimulate growth (see, for example, Acemoglu et al. Citation2005). On the national level formal institutions may introduce different programmes and policies to stimulate entrepreneurial activities (Cumming et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, more attention, according to Wennekers and Thurik (Citation1999), should be devoted to the local and regional level. Moreover, L.G.U.s which are closest to the entrepreneur should know best which actions/instruments will be most efficient in stimulating entrepreneurship in their environment (Wołowiec & Skica, Citation2013). Furthermore, opportunities created by formal institutions allow entrepreneurs to use the potential of the local institutional regime (Bruton & Ahlstrom, Citation2003). Surprisingly, as much as 34.12% of L.G.U.s in Poland did not support the development of entrepreneurship (see ). The main reason why L.G.U.s did not support the development of entrepreneurship was, in their opinion, lack of funding (see ). However, we proved that lack of funding has no influence on a supportive/unsupportive attitude towards the development of entrepreneurship. Previous research on L.G.U. debts in transition economies have shown that debt has a positive impact on ‘the modernisation of the local economies and job creations’ (Dafflon & Beer-Toth, Citation2009, p. 305). Moreover, L.G.U.s with debts should be much more eager to support the development of entrepreneurship in order to improve their financial situation, for example by collecting taxes from new businesses. The opinion of L.G.U.s on lack of funding was simply an excuse due to the lack of a self-enforcement mechanism. Another reason why L.G.U.s did not support the development of entrepreneurship was the opinion about a lack of need on the entrepreneurs’ side. Some L.G.U.s were convinced that the less interference in the local economy there was, the better it would be for entrepreneurs (see Bjørnskov & Foss, Citation2013), and that it would be enough if they established a stable institutional environment. The third reason why L.G.U.s did not support the development of entrepreneurship was, in their opinion, the low number of enterprises in their territory. However, we proved that when the number of enterprises was ‘the smallest’, meaning fewer than 600 enterprises (registered in the Polish National Business Registry per 10,000 inhabitants of working age), L.G.U.s were very active in supporting the development of entrepreneurship when compared with L.G.U.s with a higher number of enterprises, between 600 and 2000 (see ). On the other hand, when the number of enterprises exceeded 3000, then the support of L.G.U.s ceased. The general regularity was that the higher the number of enterprises within a governed territory of L.G.U., the higher the support for the development of entrepreneurship (with the exception of the number of enterprises fewer than 600 and more than 3000). It is important to highlight the research results of Bjørnskov and Foss (Citation2013), who proved that the more support for the development of entrepreneurship by formal institutions there was, the larger the positive effect on entrepreneurship. L.G.U.s in emerging economies, in order to be able to ‘catch up with’ regions of developed economies and compensate for inequalities, need to establish stable and efficient structures which will support business interactions. Only L.G.U.s with self-enforcement mechanisms succeed and support the development of local and regional entrepreneurship.

Figure 1. Behaviour of L.G.U.s in the support of the development of entrepreneurship in Poland, yearly by number of undertaken actions.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with L.G.U. n = 211.

Figure 2. Support of the development of entrepreneurship by L.G.U.s depending on the level of debts.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with L.G.U. n = 211.

Figure 3. Support of the development of entrepreneurship by L.G.U.s depending on the number of enterprises.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with L.G.U. n = 211.

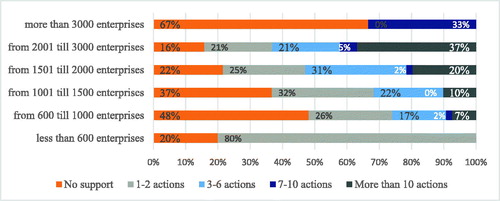

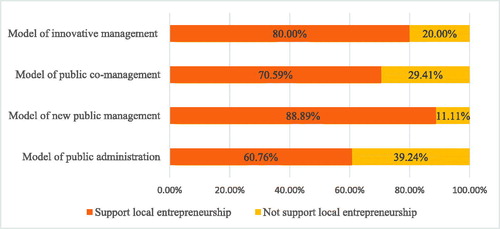

The institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship depends on the model of management. It may seem obvious that the models of management which were concentrated on citizens and entrepreneurs were more effective in the support of the development of entrepreneurship than the management model of public administration based on the Max Weber bureaucratic model of public administration. However, in Poland still as much as 74.88% of L.G.U.s have the traditional Weberian model of public administration (with obligatory changes required by Public Finance Law). Furthermore, L.G.U.s that adopted a model of N.P.M. were much more eager to support the development of entrepreneurship than L.G.U.s with a traditional management model of public administration (see ). Despite the fact that the model of N.P.M. has been criticised by many scholars, it was speculated that this model facilitated the assurance of formal institutions’ elasticity, and delivered higher regulation quality or better public services that met the requirements of citizens and entrepreneurs (Kickert, Citation1997). Moreover, the model of N.P.M. supports formal institutions’ self-enforcement mechanism towards the support of the development of entrepreneurship.

Figure 4. Support of the development of entrepreneurship by L.G.U.s with different models of management.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with L.G.U. n = 211.

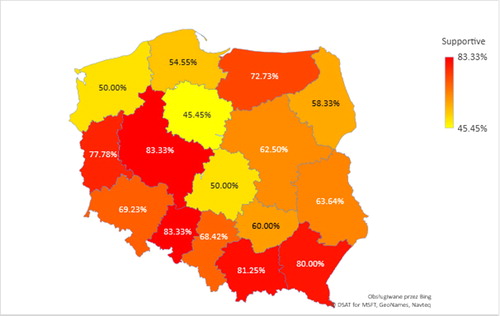

Unexpectedly, the results of this work indicated the change of institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship compared with the research done in 1995–1997 by Gorzelak et al. (Citation1999). Recently, the institutions’ behaviour towards the support of entrepreneurship has not depended on the geographic location (understood as one of seven macro-regions or as one of 16 provinces) (see ). Gorzelak et al. (Citation1999) highlighted that the behaviour of L.G.U.s is based on location in one of the four historical regions (Congress Kingdom of Poland, Galicja, Wielkopolska, West and North Lands), which after 20 years of transformation was not proven by the current study. Discrepancies may indicate the overall change in: (i) the institutions’ behaviour; (ii) the institutional environment for entrepreneurship; (iii) population drift, resulting in the more equal spread of the ‘entrepreneurship mindset’ throughout the Polish territory; or (iv) the change of informal institutions, such as the attitude of individuals towards risk, cooperation or trust that have an impact on more opportunity than necessity-driven entrepreneurship. However, even if there is no statistical correlation between location (REG II) and the L.G.U. supportive or unsupportive attitude, in 3 out of 16 provinces only 50% or even less of L.G.U.s have a supportive attitude towards the development of entrepreneurship (see ).

Figure 5. Support of the development of entrepreneurship by L.G.U.s from different macro-regions.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with L.G.U. n = 211.

Figure 6. Supportive behaviour of L.G.U.s towards the development of entrepreneurship in Poland, classified and presented at provinces level.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on survey with local formal institutions n = 211.

The institutions’ behaviour towards the support of the development of local and regional entrepreneurship depends on the type of L.G.U. However, 50% of the rural municipalities did not support the development of entrepreneurship. The most active and successful in the support of the development of entrepreneurship were provinces and cities with district rights (see ). Moreover, in rural municipalities unsupported entrepreneurship is driven by necessity (Low, Henderson, & Weiler, Citation2005). Furthermore, according to scholars, necessity entrepreneurship may be more likely to fail than opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, especially when supported by L.G.U.s (Acs, Citation2006; Shane, Citation2009). Surprisingly, 38% of the districts did not support the development of entrepreneurship. The main reason was the belief that it was not a district’s but a municipality’s task to support the development of entrepreneurship. Finally, only provinces fully succeeded in their support of the development of regional entrepreneurship. By contrast, rural municipalities failed miserably. These results partly confirmed the conclusions of the research done by Gorzelak et al. (Citation1999). These authors concluded, based just on a survey results (without measuring statistical significance), that urban municipalities were much more active in the area of the support of entrepreneurs than rural ones.

5. Conclusion

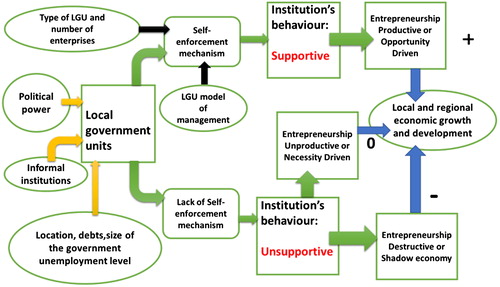

Support of L.G.U.s is very important, because it may lead to productive entrepreneurship and regional economic growth. This study has examined endogenous (such as political competition, model of management or type of L.G.U.) and exogenous (such as location, size of the territory, number of enterprises or level of unemployment) factors which have influence on supportive or unsupportive institutions’ behaviour.

Our results suggest that the institutions’ behaviour strongly depends on the model of management, type of L.G.U., and the number of enterprises in the territory governed by the L.G.U. Our contribution to filling the gap of knowledge in institutional research is proving that the self-enforcement mechanism of L.G.U.s matters for support of entrepreneurship. Because the self-enforcement mechanism of L.G.U.s seems to be crucial for the development of entrepreneurship, we also examine what explains the use of this mechanism by considering the interplay with informal institutions. We found that a greater than expected number of L.G.U.s have no knowledge about the presence of informal institutions in their surroundings. One possible implication is that the weak informal institutions do not lead to the complementing or substituting of formal institutions, but may actually be evidence of asymmetry between formal and informal institutions.

Moreover, our research has identified which institutions matter for the development of local and regional entrepreneurship by highlighting that provinces and cities with district rights were the most successful and active in the support of entrepreneurship. The agglomeration theory may also explain the success of cities with district rights. However, rural municipalities and districts failed, and this may be seen as an institutional failure which should be corrected by reinforcing the enforcement mechanisms with sanctions. Even so, we caution that central government formal institutions need to consider the costs of reinforcing the enforcement mechanism with sanctions but that supporting development of entrepreneurship appears to be promising.

One interesting result is that – despite all of the attention that academics, policy-makers, and economic development professionals have given to location, political competition or size of the territory in general – there is no evidence that these factors tend to play any role in the development of local and regional entrepreneurship. In other words, a higher number of actions undertaken by L.G.U.s to support development of entrepreneurship is possible even in municipalities with peripheral location, small territory and a lack of political competition.

Finally, this article advances institutional research through the development of a better understanding of institutional behaviour at local and regional levels by finding why some formal institutions obey the rules of the entrepreneurship game even if the state monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are lacking, and others do not (see ).

Figure 8. L.G.U. behaviour towards entrepreneurship.

Source: Authors’ own compilation based on Acemoglu et al. (Citation2005), Aidis, Estrin, and Mickiewicz (Citation2007), Baumol (Citation1990), De Soto (Citation1989), Fuentelsaz et al. (Citation2015), and North (Citation1990,Citation1994).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. London: Profile Books Limited.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401. doi:10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long run growth. In: Ph. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Acs, Z. J. (2006). How is Entrepreneurship Good for Economic Growth? Innovations, 11, 97–107. doi:10.1162/itgg.2006.1.1.97

- Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9

- Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2007). Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: a comparative perspective, Economics Working Papers No. 79, Centre for the Study of Economic and Social Change in Europe, SSEES, UCL, London.

- Akerlof, G. A., & Shiller, R. J. (2015). The Economics of Manipulation and Deception. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Arrow, K. J. (1969). The organization of economic activity: Issues pertinent to the choice of market versus nonmarket allocation. The analysis and evaluation of public expenditure: The PPB system., Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 59–73.

- Audretsch, D., Keilbach, M., & Lehmann, E. E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, A. R. (2001). What’s new about the new economy? Sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(1), 267–315. doi:10.1093/icc/10.1.267

- Baumol, W. (2002). The free-market innovation machine: Analyzing the Growth Miracle of Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 893–921. doi:10.1086/261712

- Baumol, W. J., Litan, R. E., & Schramm, C. J. (2009). Good capitalism, bad capitalism, and the economics of growth and prosperity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. J. (2013). How Strategic Entrepreneurship and the Institutional Context Drive Economic Growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 50–69. doi:10.1002/sej.1148

- Boettke, P., & Coyne, C. (2007). Context matters: Institutions and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 135–209. doi:10.1561/0300000018

- Bruton, G. D., & Ahlstrom, D. (2003). An institutional view of China’s venture capital industry: Explaining differences of China from the west. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 233–259. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00079-4

- Cantillon, R. (1755). Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en General. In: H. Higgs. (1959). Essai sur la Nature du Commerce. English Translation and other materials. London: Frank Cass and Company Ltd.

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

- Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44. doi:10.1086/466560

- Cumming, D., Johan, S., & Zhang, M. (2014). The Economic Impact of Entrepreneurship: Comparing International Datasets. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 22(2), 162–178. doi:10.1111/corg.12058

- Dafflon, B., & Beer-Toth, K. (2009). Managing local public debt in transition countries: and issue of self-control. Financial Accountability & Management, 25(3), 305–333. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0408.2009.00479.x

- De Soto, H. (2000). The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- De Soto, H. (1989). The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. New York: Harper and Row.

- Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2010). Entrepreneurship in transition economies: The role of institutions and generational change, Discussion Paper No. 4805, Germany. Bonn: IZA.

- European Commission (2013). Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan. Reigniting the entrepreneurial spirit in Europe. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0795&from=EN

- European Quality of Government Index (2017). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/maps/quality_of_governance/

- European Social Survey (2014). Retrieved from http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/download.html?file=ESS7e01&y=2014

- Evans, P. B., & Rauch, J. E. (2000). Bureaucratic Structure and Bureaucratic Performance in Less Developed Countries. Journal of Public Economics, 75, 49–71. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00044-4

- Fritsch, M., & Storey, D. J. (2014). Entrepreneurship in a regional context: historical roots, recent developments and future challenges. Regional Studies, 48(6), 939–954. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.892574

- Fuentelsaz, L., González, C., Maícas, J. P., & Montero, J. (2015). How different formal institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 18(4), 246–258. doi:10.1016/j.brq.2015.02.001

- Gorzelak, G., Jałowiecki, B., Woodward, R., Dziemianowicz, W., Herbst, M., Roszkowski, W., & Zarycki, T. (1999). Dynamics and factors of local success in Poland. Regional and local studies, 15. Warsaw: CASE - Center for Social and Economic Research and European Institute for Regional and Local Development.

- Hodgson, G. M. (2006). What Are Institutions?. Journal of Economic Issues, XL, 40(1), 1–25. doi:10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879

- Holcombe, R. G. (2015). Political Capitalism. Cato Journal, 35(1), 41–66.

- Holmes, R. M., Miller, T. J., Hitt, M. A., & Salmador, M. P. (2013). The interrelationships among informal institutions, formal institutions and inward foreign direct investment. Journal of Management, 39(2), 531–566. doi:10.1177/0149206310393503

- Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2016). Socio-spatial culture and entrepreneurship: some theoretical and empirical observations. Economic Geography, 92(3), 269–300. doi:10.1080/00130095.2016.1146075

- Karlsson, C., & Dahlberg, R. (2003). Entrepreneurship, Firm Growth and Regional Development in the New Economic Geography: Introduction. Small Business Economics, 21(2), 73–76.

- Kickert, W. J. M. (1997). Public Governance in the Netherlands: An Alternative to Anglo-American Managerialism. Public Administration, 75(4), 731–752. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00084

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. New York: Augustus M. Lelley.

- Koellinger, P. D., & Thurik, A. R. (2012). Entrepreneurship and the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1143–1156. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00224

- Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99, 484–499.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(2), 285–332. doi:10.1257/jel.46.2.285

- Levie, J., Autio, E., Acs, Z., & Hart, M. (2014). Global entrepreneurship and institutions: an introduction. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 437. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9516-6

- Low, S., Henderson, J., & Weiler, S. (2005). Gauging a Region’s Entrepreneurial Potential. Economic Review, 90, 61–89.

- Minniti, M., & Lévesque, M. (2008). Recent developments in the economics of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 603–612. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.001

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. American Economic Review, 84(3), 359–368.

- Peters, B. G. (2001). The Future of Governing, 2nd ed., Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development?. Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Sager, F., & Rosser, C. (2009). Weber, Wilson, and Hegel: Theories of Modern Bureaucracy. Public Administration Review, 69(6)November/December, 1136–1147. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02071.x

- Sautet, F. (2013). Local and systemic entrepreneurship: Solving the puzzle of entrepreneurship and economic development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(2), 387–402. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00469.x

- Say, J. B. (1800). Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/node/13565718

- Schumpeter, J. (1934). Theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–226. doi:10.5465/amr.2000.2791611

- Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5

- Skica, T., Bem, A., & Daszyńska-Żygadło, K. (2013). The role of local government in the process of entrepreneurship development. Financial Internet Quarterly e-Finanse, 9(4), 1–24.

- Treaty on the functioning of the European Union (2012). Official Journal of the European Union C 326/01.

- Tullock, G. (1965). The politics of bureaucracy. Washington D.C.: Public Affairs Press.

- Voigt, S. (2013). How (Not) to Measure Institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 9(01), 1–26. doi:10.1017/S1744137412000148

- Webb, J. W., Tihanyi, L., Ireland, R. D., & Sirmon, D. G. (2009). You say illegal, I say legitimate: entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 492–510. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.40632826

- Wennekers, S., & Thurik, A. R. (1999). Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 27–55. doi:10.1023/A:1008063200484

- Williams, C. C., & Shahid, M. S. (2016). Informal entrepreneurship and institutional theory: explaining the varying degrees of (in)formalization of entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(1-2), 1–25. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.963889

- Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2015). Institutional asymmetry: How formal and informal institutions affect entrepreneurship in Bulgaria. International Small Business Journal, 33(8), 840–861. doi:10.1177/0266242614534280

- Williams, N., Vorley, T., & Williams, C. C. (2017). Entrepreneurship and Institutions. The Causes and Consequences of Institutional Asymmetry. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Williamson, C. R. (2009). Informal institutions rule: Institutional arrangements and economic performance. Public Choice, 139(3-4), 371–387. doi:10.1007/s11127-009-9399-x

- Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233–261. doi:10.1086/466942

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. doi:10.1257/jel.38.3.595

- Wołowiec, T., & Skica, T. (20013). (2013). The Instruments Of Stimulating Entrepreneurship By Local Government Units (LGU’s). Ekonomska Istraživanja – Economic Research, 26(4), 127–146. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2013.11517635

- World Bank Group (2017). Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017. Retrieved from http://info.worldbank.org/governance/WGI/#reports

- World Economic Forum (2018). The Global Competitiveness Index 2017–2018. Retrieved from https://widgets.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2017/