?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We analyse the effects of fiscal and monetary policies in Croatia and Macedonia estimated by a Bayesian vector autoregression (VAR). The main results of the study are as follows. Fiscal tightening leads to economic expansion in Macedonia and a decline in economic activity in Croatia. In both countries fiscal tightening leads to a decline in inflation and money market rates. Monetary tightening leads to output contraction and a decline in inflation in both countries. We find an opposite reaction of the fiscal authorities to a monetary shock, i.e., monetary contraction is accompanied by fiscal tightening in Croatia and by loose fiscal policy in Macedonia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Since the seminal work of Mundell (Citation1963) and Fleming (Citation1962) a large body of literature has analysed the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policies under a fixed exchange rate regime (for instance, see Bahmani-Oskooee and Pourheydarian, Citation1990; Gali and Monacelli, Citation2005; Lane and Perotti, Citation2003; Niehans, Citation1968; Shambaugh, Citation2004). Recently, the global financial crisis has revived the emphasis on fiscal policy as the effectiveness of monetary policy has been constrained by the lower-zero bound of interest rates (Blanchard et al., Citation2010). Hence, at the outset of the economic recession in 2009, these economies were faced with pressures on the foreign exchange market. Accordingly, despite the decline in economic activity, the monetary policy makers were forced to tighten in order to restore the balance on the foreign exchange market by reducing the liquidity of the banking system. Thus, examining the interaction between monetary and fiscal policies during the recent economic downturn may provide additional useful policy implications for these economies.

Most of the empirical research on the effects of monetary and/or fiscal policy has been conducted within the VAR methodology. We employ the recently developed Bayesian VAR in order to investigate the macroeconomic policies in two South East European countries with fixed exchange rate regime (Croatia and Macedonia). The primary focus of our study is twofold: first, what the effects of monetary and fiscal policies are and, second, how these policies react to each other as well as to other macroeconomic shocks. Since we deal with small open economies, our VARs explicitly incorporate the effects of foreign macroeconomic shocks on these economies.

We provide evidence for a countercyclical response of fiscal policy and procyclical reaction of the central banks during the business cycle. As for the effects of macroeconomic policies, the main results are as follows: fiscal tightening leads to economic expansion in Macedonia and a decline in economic activity in Croatia. At the same time, in both countries fiscal tightening leads to a short-lived decline in both inflation and money market rates. Monetary tightening leads to output contraction and a decline in inflation in both countries. Yet, we find an opposite reaction from the fiscal authorities to a monetary shock: in Croatia, monetary contraction is accompanied by fiscal tightening in Croatia and by a loose fiscal policy in Macedonia.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the empirical literature on the effects of monetary and fiscal policy. The data description and the estimation methods are presented in Section 3. The findings of the empirical study are presented in Section 4, which is followed by the main conclusions.

2. Review of the empirical literature

Following the seminal paper by Sims (Citation1980), a large body of empirical literature has investigated the effects of monetary policy based on the VAR methodology. For a non-exclusive list, see Bagliano and Favero (Citation1998), Beranke and Blinder (1992), Bernanke and Mihov (Citation1998), Christiano et al. (Citation1996), Gordon and Leeper (Citation1994), Hoover and Jordá (Citation2001), Leeper et al. (Citation1996), Rudebusch (Citation1998), Sims (Citation1992), and Uhlig (Citation2005).

Blanchard and Perotti (Citation2002) introduced the structural VAR (SVAR) in the identification of fiscal policy shocks while Ramey and Shapiro (Citation1998) and Romer and Romer (Citation2010) implemented the alternative narrative approach. Burnside et al (Citation2004), Edelberg et al. (Citation1999), and Ramey (Citation2011) are examples of VAR studies with shocks identified by the approach of Ramey and Shapiro (Citation1998). Perotti (Citation2007) modifies the event-study approach and compares it with the Blanchard-Perotti approach. Favero and Giavazzi (Citation2012) argue that structural shocks in the VARs can be identified by the narrative approach, which are orthogonal to the information set included within the VAR. Along these lines, Mertens and Ravn (Citation2012) employ the narrative approach of Romer and Romer (Citation2010) within the SVAR. Recently, a number of studies have employed different combinations of the main policy shocks identification approaches. For example, Dungey and Fry (Citation2007) deal with the identification of fiscal and monetary shocks by using the sign restrictions and permanent and temporary shock methodology of Pagan and Pesaran (Citation2007). Caldara and Kamps (Citation2008) employ the recursive approach, the Blanchard-Perotti approach, the sign restrictions approach and the event-study approach.

The empirical research has provided divergent results with respect to both the direction and magnitude of the effects of fiscal policy shocks on macroeconomic variables. Specifically, some of the studies find that fiscal policy shocks have clear positive effects on output, consumption and/or employment in line with the traditional Keynesian view (Fatas and Mihov, Citation2001; Galí et al., Citation2007; Giordano et al., Citation2008; Romer and Romer, Citation2010). In addition, some studies confirm that, typically, fiscal policy has had a stabilising role in the business cycles by running countercyclical primary deficits (Fatas and Mihov, Citation2001; Mélitz, Citation1997; Taylor, Citation2000; Galí and Perotti, Citation2003). On the other hand, some papers provide mixed evidence regarding the debate on the Keynesian vs. non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy, revealing that expansionary fiscal policy may produce adverse effects on some macroeconomic variables as suggested by neoclassical theoretical predictions (Ramey and Shapiro, Citation1998; Edelberg et al., Citation1999; Blanchard and Perotti, Citation2002; van Aarle et al., Citation2003; Burnside et al., Citation2004; Mountford and Uhlig, Citation2005; Perotti, Citation2004, Citation2007; Caldara and Camps, 2008; Afonso and Sousa, Citation2009; Cogan et al., Citation2010; Barro and Redlick, Citation2011; Ramey, Citation2011).

The global crisis has provoked a growing interest in the effects of fiscal policy and the interactions with monetary policy in the former transition economies, too. As shown below, even empirical studies supporting the traditional Keynesian effects of fiscal policy fail to produce quantitatively important fiscal multipliers. Moreover, some papers indicate that expansionary fiscal policy may have adverse effects on output, investment and employment in line with the neoclassical models. Overall, one may conclude that the potential of fiscal policy to stimulate economic activity in CEE countries is very limited, which is in line with the findings in Ilzetzki et al. (Citation2013). In the following paragraphs we briefly review the empirical evidence for this area.

Crespo-Cuaresma et al. (Citation2011) find that monetary policy in CEE economies usually offsets domestic fiscal expansion, while on the other hand fiscal authorities usually accommodate the interest rate shocks. Baxa (Citation2010) and Franta (Citation2012) provide evidence that fiscal policy in the Czech Republic produces the traditional Keynesian effects. The latter also shows that the expansionary fiscal policy leads to higher inflation, while the central bank reacts as a substitute by increasing short-term interest rates. In Caraiani (Citation2010), too, both output and inflation rise following an expansionary fiscal policy, while monetary policy behaves in a counteracting manner. Similarly, Jemec et al. (Citation2011) show that fiscal policy shocks in Slovenia produce the Keynesian effects, but they are short-lived and of small magnitude.

Baksa et al. (Citation2010) show that the effectiveness of fiscal policy in Hungary is very limited, i.e. fiscal multipliers are low and short-lived. As for the interactions between fiscal and monetary policies, they conclude that the effects of fiscal policy are not dependent on the stance of monetary policy (accommodative or aggressive). Lendvai (Citation2007) provides mixed evidence on the effectiveness of fiscal policy in Hungary, i.e. the increase in government expenditure has positive effects on household consumption and negative effects on the corporate sector. Due to this strong crowding-out effect, total output and employment decline. Mirdala (Citation2009) analyses the effects of fiscal policy shocks in several CEE and SEE economies during 2000–2008 and finds mixed results about the output effects of government expenditure shocks in different countries. Benčík (Citation2009) provides evidence in favour of neoclassical predictions about fiscal policy effects. Specifically, he finds that fiscal consolidation (a cut in the budget deficit to GDP ratio) leads to an increase in output, though the effects are short-term. Similarly, Rzonca and Cizkowicz (Citation2005) provide evidence that fiscal consolidation has strong favourable effects on output growth. Serbanoiu (Citation2012) shows that in Romania positive government expenditure shocks lead to an increase in output, a decline in private consumption and investment (crowding-out effect), an initial rise in inflation and a temporary decline in interest rates. Bobaşu (Citation2015) and Boiciuc (Citation2015) also show that the effects of fiscal policy are rather limited.

There are a few studies on the effects of fiscal and monetary policies and their interactions in the SEE economies. Muir and Weber (Citation2013) investigate the effects of fiscal policy in Bulgaria during 2003–2011 and provide the following main results: fiscal multipliers are very low, especially for government expenditure; recently, fiscal multipliers have increased, suggesting that the impact of fiscal policy on economic activity is larger in recessions; and the size of fiscal multipliers depends on the composition of expenditure and revenues. Mirdala (Citation2009) shows that in Bulgaria fiscal expansion has strong positive effects on output (which dies out very quickly), but it leads to increased inflation and higher short-term interest rates. For Albania, Mançellari (Citation2011) shows that fiscal multipliers are very low, and positive government spending shocks lead to slightly higher inflation.

Rukelj (Citation2009) investigates the interactions of fiscal policy, monetary policy and economic activity in Croatia. His study shows that fiscal and monetary policy move in opposite directions, i.e. they have been used as substitutes: fiscal shocks have a predominantly negative impact on narrow money, while monetary shocks produce negative effects on government expenditure. Ravnik and Žilić (Citation2011) find that both government expenditure and tax revenues shocks have negative effects on output in Croatia. Also, they show that the interest rates show the strongest response to fiscal shocks, while fiscal shocks have minor and short-lived effects on inflation. Hinić and Miletić (Citation2013) analyse the effects of fiscal and monetary policies in Serbia and show that both government expenditure and tax revenue shocks produce positive impacts on output in Serbia, but the fiscal multipliers are much smaller than in the short run. As for the interactions between the two policies, they find that monetary policy accommodates fiscal policy shocks and vice versa, i.e. they act as complements. Deskar Škrbić and Šimović (Citation2015) show that the fiscal multipliers in Croatia are larger as compared with Serbia and Slovenia.

3. Data and methodology

We work with quarterly data from 2000 to 2011, providing 48 observations for Macedonia and 47 observations for Croatia. Specifically, for Macedonia, the sample starts from the first quarter of 2000, when, following a comprehensive reform of monetary policy instruments, central bank bills were introduced. Similarly, for Croatia, the sample starts from the second quarter of 2000 for two reasons: first, money market rate data are available only from this quarter onward, and second, we want to avoid the effects of the banking crisis from 1998–1999.

The VARs include four domestic macroeconomic variables, which are chosen as indicators of fiscal policy, monetary policy, inflation and economic activity in each country, respectively. Specifically, we work with the primary cyclically adjusted government balance/GDP ratio (Fd), the money market interest rate (id), the CPI-based inflation rate (πd), and the output gap (yd). All the data for these countries were collected from their central bank and ministry of finance websites. For consistency, the data related to fiscal revenues and expenditures throughout the whole sample period are adjusted according the Governmental Financial Statistics (GFS) 2001 methodology set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Though we are primarily interested in domestic policies, our empirical model also comprises a set of foreign variables, such as the euro-zone output gap (yf), the 3-month Euribor (if), and the euro-zone inflation (πf). We estimate the VARs separately for the three economies.

Domestic money market interest rates are used as indicators of monetary policy in Croatia and Macedonia. In spite of the fixed exchange rate regime, we believe that there is a room for autonomous monetary policy in these two countries due to the following reasons: first, interest rate parity holds only if there is perfect capital mobility, where domestic and foreign assets are perfect substitutes. Obviously, these assumptions are too strong for Croatia and Macedonia; second, both the Macedonian and Croatian central banks have relied on a series of non-interest rate policy tools, thus, being able to affect domestic money market rates (see Lang and Krznar (Citation2004)).

As for the primary government balance, we use central government due to data availability. The output gap is calculated as the percentage difference between actual and potential GDP. In estimating potential GDP and output gap we rely on the one-sided Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter with the default lambda of 1600 (λ = 1600). We do not apply the commonly used two-sided HP filter estimated from the whole sample because this approach introduces trends that were not known at the time of shocks, which can substantially confound the estimated effects of shocks. Also, some necessary transformations have been performed on the original data, such as seasonal adjustment and differencing. For instance, the series of real GDP, inflation, and fiscal data (government revenues and expenditures) have been seasonally adjusted by the “CENSUS X-12”. We have performed a battery of unit root tests (the Augmented Dickey-Fuller, Phillips-Perron, and Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin tests), showing that all the series, except for the money market rates, are stationary in levels (). Consequently, both domestic and foreign money market rates have been first differenced in order to obtain stationarity. The complete set of the unit root tests are given in .

The VAR methodology is a standard framework for assessing the effects of monetary and/or fiscal policy (seminal papers include Bernanke and Blinder, Citation1992; Bernanke and Mihov, Citation1998; and Blanchard and Perotti, Citation2002). Given the problems related with the fully fledged structural models of fiscal and monetary reaction functions, which often incorporate more or less arbitrary identifying restrictions, especially for fiscal policy rules, Muscatelli et al. (Citation2002), we apply recursive VARs for modelling the interactions between domestic macroeconomic variables.

The general specification of the recursive VAR model can be written as follows:

(1)

(1)

where y is a K×1 vector of endogenous variables, A* is a K×K coefficient matrix, µ is a vector of constants, L is the lag operator, ε is the structural form orthogonal errors, t is a time operator. A is a lower triangular matrix (A = Ik) that specifies instantaneous relations between the variables in the model and B is a KxK is an identity matrix.

In order for model (1) to be estimated, we first need to estimate its reduced form version, presented as follows:

(2)

(2)

where the same symbols of Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) apply to Equationequation (2)

(2)

(2) , with the major difference of u which are reduced form disturbances to the structural shocks ε from Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) . The relationship between u and ε is as follows:

(3)

(3)

Model (1) is known in the literature as AB model and it is used to estimate the short-run relationship among the variables (the short-run model). In order for models (1) and (3) to be identified and the structural disturbances ε to be orthogonal, certain restrictions of the parameter matrices A and B have to be placed. More precisely, in order models (1) and (3) to be exactly identified, at least K(K-1)/2 restrictions need to be imposed on A and B matrices respectively, or in total K(3 K-1)/2 restrictions, where K is the number of endogenous variables in the model Lutkepohl and Kratzig (Citation2004). In our case, B being identity matrix, the restrictions are imposed on matrix A alone.

The specification of the recursive VAR model expressed in a matrix form is as follows:

Specifically, we impose the following restrictions in the VARs: (a) foreign variables have a contemporaneous impact on each of the domestic variables; (b) policy variables do not have a contemporaneous impact on economic activity because they affect the “real” sector with a certain time lag (see Blanchard and Quah, Citation1989). As can be seen, we build our empirical model on the assumption that foreign variables are exogenous to the SEE economies so that the VARs incorporate explicitly foreign shocks. This assumption arises quite naturally given that we focus on small open economies which are integrated with the EU. In addition, in order to fully incorporate the small open economy assumption, we follow Cushman and Zha (Citation1997) by imposing the block-exogeneity restrictions in the model. Specifically, in the baseline unrestricted VARs, the lags of foreign variables are included in the equations of domestic variables, while the lags of domestic variables are excluded from the equations of foreign variables. In a matrix notation, in a simplified form (by omitting the constant and other deterministic regressors), this can be presented as follows:

where Y(t) is a Kx1 vector of observations, A(L) is an KxK matrix polynomal in the lag operator L with non-negative powers and ε(t) is an Kx1 vector of structural disturbances. The dimension of A11(L) is K1xK1, A12(L) is K1xK2, A13(L) is K1xK3 and so on. The dimension of εtyf is K1x1, of εtif is K2x1 and so on. The restrictions A14(L) = A15(L) = A16(L) = A17(L) = A24(L) = A25(L) = A26(L) = A27(L) = A34(L) = A35(L) = A36(L) = A37(L) = 0 imply that the first block of foreign three variables are exogenous to the model whereas the lags of the domestic variables do not enter in their equations (they are restricted to zero).

We employ the Bayesian procedure for estimating the VARs in order to overcome the short sample problem. Recently Bayesian VAR methodology has become a relevant tool for evaluation of the effects of macroeconomic shocks (for instance, see Doan et al., Citation1984; Litterman, Citation1986; Ritschl and Woitek, Citation2000; Caldara and Kamps, Citation2008; Afonso and Sousa, Citation2009). The Bayesian approach offers a solution to the curse of dimensionality problem by shrinking the parameters via the imposition of priors. Koop and Potter (Citation2003), Wright (Citation2003), Stock and Watson (Citation2005, Citation2006) explore the performance of the Bayesian approach in relatively small systems, while De Mol et al. (Citation2008) and Banbura et al. (Citation2010) confirm its validity even in systems with a large number of predictors compared to the small sample sizes that are typical in macroeconomic analysis. We use the independent normal-inverse-Wishart prior, which is frequently used in the literature; see e.g. Kadiyala and Karlsson (Citation1997), and Banbura et al. (Citation2010), while the set of prior hyperparameters are also taken from the latter paper. The lag length of one quarter is used in the VARs, based on the Bayesian information criteria.

4. Discussion

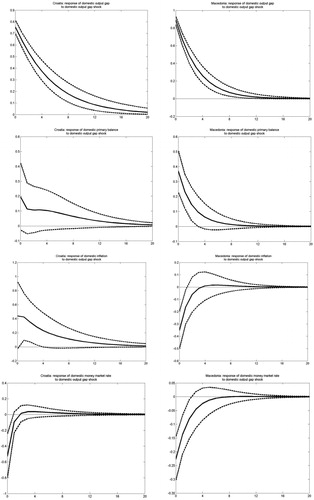

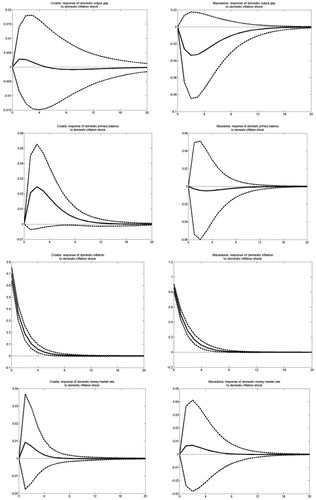

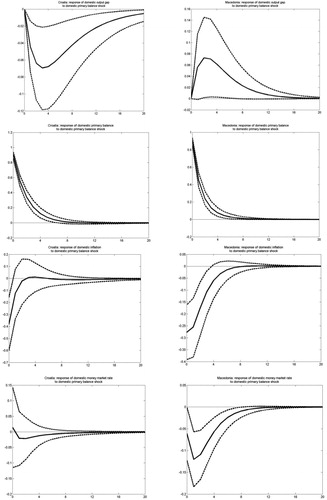

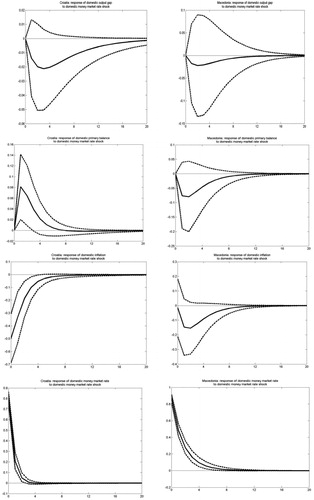

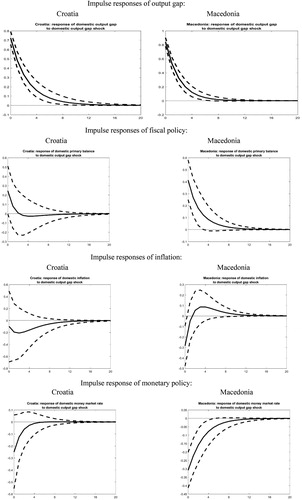

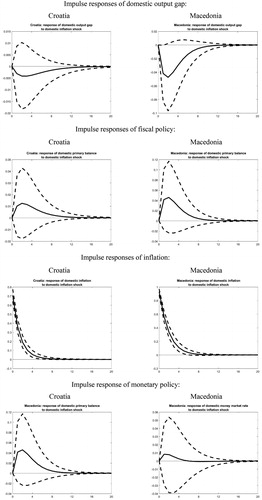

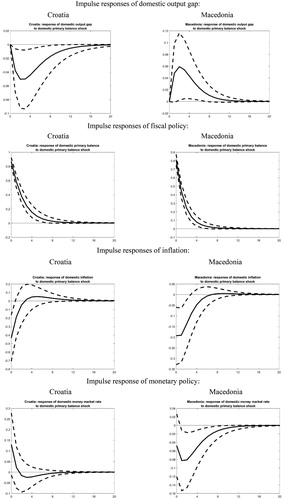

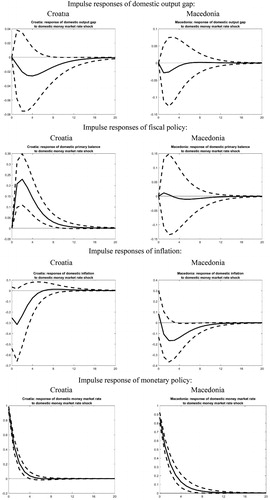

In this section we provide a discussion on the cumulative impulse responses from the VARs. In assessing the impulse response functions (IRFs) we calculate the 95% Bayesian highest posterior density sets, which are analogous to the confidence bands in classical statistics. The impulse IRFs of the variables from the VARs are provided in Appendix 2 and are ordered according to the variable from which the impulses are generated.

The reaction of monetary and fiscal policies to a shock in the output gap is shown in Figure 1 of Appendix 2. Here, in both countries, an increase in the domestic economic activity leads to higher cyclically adjusted budget surpluses. This suggests that fiscal policy behaviour in these economies is countercyclical, i.e. fiscal authorities adjust budget revenues and expenditures according to the changes in the economic cycle. Specifically, it seems that the fiscal policy authorities take advantage of the economic expansion by increasing the budget surplus or reducing the deficit. In Croatia, the countercyclical reaction of fiscal authorities is lower as compared to Macedonia as well as statistically insignificant. In Macedonia, the reaction is short-lived, i.e. the impulses decay within a year reflecting the lower degree of persistence of output shocks. Overall, these findings confirm that, typically, fiscal policy has a stabilising role in the business cycles (Fatas and Mihov, Citation2001; Mélitz, Citation1997; Galí and Perotti, Citation2003). Also, they are consistent with Crespo-Cuaresma et al. (Citation2011) who provide evidence for a countercyclical behaviour of fiscal policy in Central European economies. As for the monetary policy makers, Figure 1 reveals that they seem to react in an opposite manner: following a positive output shock, money market rates decline, thus, suggesting procyclical behaviour of central banks. This type of reaction on the part of the central bank may be explained by the efforts to offset the potential adverse effects of the fiscal tightening. Yet, the reaction of monetary policy is short-lived, especially in Croatia.

Figure 2 of Appendix 2 shows the response of macroeconomic policies to an inflation shock. Once again, one can observe a countercyclical reaction of fiscal authorities in the two countries, which is closely related to the differences in the response of the output gap. In Croatia, higher inflation is accompanied by a positive output gap and, thus, fiscal authorities run budget surpluses. On the other hand, in Macedonia, higher inflation leads to a negative output gap and small budget deficits. The response of monetary policy is in line with the a priori expectations, i.e. money market rates increase in both countries though the central banks’ reaction is too small and short-lived. Finally, one should note that not all the impulses are statistically significant.

The next two figures in Appendix 2 show the effects of macroeconomic policies. As shown in Figure 3, a positive shock in the cyclically adjusted budget balance leads to economic expansion in Macedonia, probably reflecting the favourable effects of fiscal tightening on inflation expectations. In Croatia, we obtain a mirror-shaped response, i.e. the fiscal tightening is accompanied by a decline in economic activity. At the same time, in both countries fiscal tightening leads to a short-lived decline in inflation. However, the impulses are statistically significant only in Macedonia. As for the reaction of monetary policy one can observe a short-lived decline in money market rates in Croatia and Macedonia, but, once again, the impulses are statistically significant only in Macedonia where the central bank attempts to offset the effects of fiscal shocks. This result may be related to the countercyclical behaviour of fiscal policy: the attempts of fiscal authorities to counteract the positive output gap have favourable effects on inflationary expectations, leading to monetary easing.

Figure 4 of Appendix 2 reveals the IRFs to a shock in the money market rates. Here, the effects of monetary tightening are as expected, i.e. it leads to output contraction and a decline in inflation. Yet, we find an opposite reaction of the fiscal authorities: in Croatia, monetary contraction is accompanied by tight fiscal policy whereas in Macedonia fiscal authorities run budget deficits in response to higher money market rates.

Robustness check

One possible objection to the results obtained from our empirical model is that they could be potentially affected by the global financial and economic crisis (the crisis). Therefore, as a robustness check, we have re-estimated the VARs on a restricted sample that ends by the fourth quarter of 2008. Note that we are not able to re-estimate the empirical model for the period after the crisis due to the very short sample. The IRFs for the pre-crisis sub-sample are provided in the Appendix 3. Generally, we find a striking resemblance in the response of macroeconomic variables to various shocks. In what follows, we provide a brief discussion of the most important findings from this exercise, focusing only on the cases where considerable difference occurs.

As for the IRFs generated from an output shock (Figure 5 of Appendix 3), the results are virtually the same compared to the whole sample, i.e. during the pre-crisis period, too, fiscal authorities respond in a countercyclical manner by increasing the primary budget surpluses. Once again, the reaction is short lived, especially in Croatia where the impulses are not statistically significant. Similar to the whole sample, the central banks in the two countries lower their policy rates in an attempt to offset the negative effects of fiscal tightening. Hence, we provide evidence that monetary and policy makers in the two countries act as strategic substitutes in the presence of output shocks.

Following an inflation shock (Figure 6 of Appendix 3), the reaction of the central banks in the two countries is as expected: they raise their interest rates in line with their focus on price stability as the primary objective. Yet, note that the IRFs are statistically insignificant, which is probably due to the short sample. As for the reaction of fiscal authorities, the only difference can be observed in Macedonia. Specifically, in the whole sample, the budget balance in Macedonia worsens in the presence of an inflation shock while there is an opposite response during the pre-crisis period when fiscal policy tightens. This difference could be explained by the difference in the preferences of fiscal authorities: faced with favourable macroeconomic environment in the pre-crisis period, it seems that fiscal authorities were more concerned with fighting inflation pressures.

The effects of fiscal shocks during the pre-crisis period are shown in Figure 7 of Appendix 3. Here, the response of output and inflation is the same as in the whole sample. However, there is a slight difference in the reaction of monetary policy: unlike the whole sample when the central banks in both countries respond by lowering their policy rates, before the crisis we observe an opposite reaction by the central bank of Croatia though the impulses are not statistically significant.

Finally, Figure 8 of Appendix 3 reveals the similarity of the results for the two samples: following an increase in the monetary policy rate, both in the whole sample and in the pre-crisis period, output and inflation decline in Croatia as well as in Macedonia. The only difference refers to the response of the budget balance in Macedonia, which declines in the whole sample while fiscal policy remains neutral in the pre-crisis period. This finding suggests that after the crisis fiscal authorities in Macedonia act as strategic substitutes with respect to monetary policy by offsetting the potential contractionary effects of monetary tightening. Again, this difference in the response of fiscal authorities may reflect their greater preference to output stabilization during the post-crisis period.

In sum, the comparison of the IRFs from the whole sample with those from pre-crisis sub-sample suggests that the crisis did not lead to considerable differences in the response of macroeconomic variables to fiscal and monetary policy shocks. This finding may be rationalized by the rigid exchange rate regimes prevailing in Croatia and Macedonia, which impose severe constraints on the behaviour of policy makers.

5. Conclusion

This paper examines the reaction functions as well as the effects of monetary and fiscal policies in two SEE economies with fixed exchange rates: Croatia and Macedonia. Specifically, we conduct an empirical investigation in the linkages between several macroeconomic and policy variables (output, inflation, interest rates and budget surpluses) based on the impulse response functions estimated with Bayesian VAR.

We find that domestic economic expansion leads to positive fiscal balances in both countries. This implies that fiscal policy behavior in these economies is countercyclical, suggesting that fiscal policy makers are actively adjusting the fiscal revenues and expenditures according to the changes in the economic cycle. On the other hand, we find a short-lived procyclical reaction by the central banks, possibly reflecting their efforts to offset the potential adverse effects of the fiscal tightening.

Fiscal tightening leads to economic expansion in Macedonia, probably reflecting the favourable effects on inflation expectations, while in Croatia fiscal tightening is accompanied by a decline in economic activity. At the same time, in both countries fiscal tightening leads to a short-lived decline in both inflation and money market rates.

The effects of monetary tightening are as expected, i.e. it leads to output contraction and a decline in inflation. Yet, we find an opposite reaction by the fiscal authorities: in Croatia, monetary contraction is accompanied by fiscal tightening in Croatia and loose fiscal policy in Macedonia.

The comparison of the results for the whole sample with those for the pre-crisis sub-sample suggests that the crisis did not lead to considerable differences in the response of macroeconomic variables to fiscal and monetary policy shocks. This finding may be rationalized by the rigid exchange rate regimes prevailing in Croatia and Macedonia, which impose severe constraints on the behaviour of policy makers. Yet, some additional issues remain open for further research. For example, it will be interesting to investigate the macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy and monetary–fiscal interactions by considering budget revenues and budget expenditure separately. This will enable us to estimate the fiscal multipliers on both the revenue and expenditure side and, thus, to compare the effects of these two fiscal policy instruments for stabilization purposes. In addition, working with budget revenues and expenditure separately will give us further insights into the fiscal–monetary interactions because fiscal policy might respond differently from monetary policy shocks on the revenue and the expenditure side.

References

- Afonso, A., & Sousa, R. M. (2009). The Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Policy, ECB Working Paper No. 991, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Pourheydarian, M. (1990). Exchange rate sensitivity of demand for money and effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policies. Applied Economics, 22(7), 917–925. doi: 10.1080/00036849000000029

- Bagliano, F. C., & Favero, C. A. (1998). Measuring Monetary Policy with VAR Models: an Evaluation. European Economic Review, 42(6), 1069–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00005-1

- Baksa, D., Benk, S., & Jakab, Z. M. (2010). Does “The” Fiscal Multiplier Exist?”, in Fiscal and Monetary Reactions, Credibility and Fiscal Multipliers in Hungary. Office of the Fiscal Council.

- Banbura, M., Giannone, D., & Reichlin, L. (2010). Large Bayesian vector autoregressions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 25, 71–92. doi: 10.1002/jae.1137

- Barro, R. J., & Redlick, C. J. (2011). Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 51–102. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjq002

- Baxa, J. (2010). What the data say about the effects of fiscal policy in the Czech Republic?. In M. Houda, & J. Friebelova (eds.), Mathematical Methods in Economics 2010, Bohemia, Ceske Budejovice: University of South, pp. 24–29.

- Benčík, M. (2009). The Analysis of the Effects of Fiscal Policy on Business Cycle—A SVAR Application”, National Bank of Slovakia, Working Paper 2/2009.

- Bernanke, B., & Blinder, A. (1992). The Federal funds rate and the channels of monetary transmission. American Economic Review, 82(4), 901–921.

- Bernanke, B., & Mihov, I. (1998). Measuring Monetary Policy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 869–902. doi: 10.1162/003355398555775

- Blanchard, O., Dell’Ariccia, G., & Mauro, P. (2010). Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy In Blanchard, O., and SaKong, I., eds., Reconstructing World Economy, Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund and Korea Development Institute, 25–40.

- Blanchard, O., & Quah, D. (1989). The dynamic effects of aggregate demand and aggregate supply disturbances. American Economic Review, 79(4), 655–673.

- Blanchard, O. J., & Perotti, R. (2002). An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1329–1368. doi: 10.1162/003355302320935043

- Bobaşu, A. (2015). Fiscal policy in emerging economies. A Bayesian approach. Procedia Economics and Finance, 27, 612–620. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01041-2

- Boiciuc, I. (2015). The effects of fiscal policy shocks in Romania. A SVAR Approach. Procedia Economics and Finance, 32, 1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01578-6

- Burnside, C., Eichenbaum, M., & Fisher, J. D. M. (2004). Fiscal shocks and their consequences. Journal of Economic Theory, 115(1), 89–117. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0531(03)00252-7

- Caldara, D., & Kamps, C. (2008). “What are the Effects of Fiscal Policy Shocks? A VAR Based Comparative Analysis”, ECB Working Paper No. 877, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

- Caraiani, P. (2010). Fiscal Policy in CEE Countries: Evidence from Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania. Poland: CERGE-EI Foundation.

- Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M., & Evans, C. L. (1996). The effects of monetary policy shocks: Evidence from the flow of funds. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1), 16–34. doi: 10.2307/2109845

- Cogan, J. F., Cwik, T., Taylor, J. B., & Wieland, V. (2010). New Keynesian versus old Keynesian government spending multipliers. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 34(3), 281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jedc.2010.01.010

- Crespo-Cuaresma, J., Eller, M., & Mehrota, A. (2011). The Economic Transmission of Fiscal Policy Shocks from Western to Eastern Europe”, BOFIT Discussion Papers, No. 12. Helsinki: Bank of Finland.

- Cushman, D. O., & Zha, T. (1997). Identifying monetary policy in a small open economy under flexible exchange rates. Journal of Monetary Economics, 39(3), 433–448. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3932(97)00029-9

- De Mol, C., Giannone, D., & Reichlin, L. (2008). Forecasting using a large number of predictors: Is Bayesian shrinkage a valid alternative to principal components?. Journal of Econometrics, 146(2), 318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.08.011

- Deskar Škrbić, M., & Šimović, H. (2015). The size and determinants of fiscal multipliers in Western Balkans: comparing Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia. EFZG Working Paper Series/EFZG Serija Članaka u Nastajanju, 10, 1–21.

- Doan, T., Litterman, R., & Sims, C. (1984). Forecasting and conditional projection using realistic prior distributions”. Econometric Reviews, 3(1), 1–100. doi: 10.1080/07474938408800053

- Dungey, M., & Fry, R. (2007). The Identification of Fiscal and Monetary Policy in a Structural VAR”, CAMA Working Paper No. 29, Canberra: The Australian National University.

- Edelberg, W., Eichenbaum, M., & Fisher, J. D. M. (1999). Understanding the Effects of a Shock to Government Purchases. Review of Economic Dynamics, 2(1), 166–206. doi: 10.1006/redy.1998.0036

- Fatas, A., & Mihov, I. (2001). Government Size and Automatic Stabilizers: International and Intranational Evidence. Journal of International Economics, 55(1), 3–28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00093-9

- Favero, C., & Giavazzi, F. (2012). Measuring Tax Multipliers: The Narrative Method in Fiscal VARs. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(2), 69–94. doi: 10.1257/pol.4.2.69

- Fleming, J. M. (1962). Domestic Financial Policies Under Fixed and Floating Exchange Rates. International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, 9(3), 369–379. doi: 10.2307/3866091

- Franta, M. (2012). Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Policy in the Czech Republic: Evidence Based on Various Identification Approaches in a VAR Framework. Czech National Bank, Working Paper Series, 13/2012

- Galí, J., López-Salido, D., & Vallés, J. (2007). Understanding the Effects of Government Spending on Consumption. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(1), 227–270. doi: 10.1162/JEEA.2007.5.1.227

- Galí, J., & Perotti, R. (2003). Fiscal Policy and Monetary Integration in Europe, NBER Working Paper 9773, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Gali, J., & Monacelli, T. (2005). Monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(3), 707–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2005.00349.x

- Giordano, R., Momigliano, S., Neri, S., & Perotti, R. (2008). The effects of fiscal policy in Italy: Evidence from a VAR model, Bank of Italy Working Paper No. 656, Roma: Banca D'Italia.

- Gordon, D. B., & Leeper, E. M. (1994). The Dynamic Impacts of Monetary Policy: An Exercise in Tentative Identification. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1228–1247. doi: 10.1086/261969

- Hinić, B., & Miletić, M. (2013). Efficiency of the fiscal and monetary stimuli: the case of Serbia. (mimeo),

- Hoover, K. D., & Jordá, O. (2001). Measuring Systematic Monetary Policy. Review, 83(4), 113–138. doi: 10.20955/r.83.113-138

- Ilzetzki, E., Mendoza, E. G., & Végh, C. A. (2013). How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers?”. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(2), 239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2012.10.011

- Jemec, N., Strojan Kastelec, A., & Delakorda, A. (2011). “How do fiscal shocks affect the macroeconomic dynamics in the Slovenian economy”. Bank of Slovenia, Prikazi in Analize, 2 /, 2011.

- Kadiyala, K. R., & Karlsson, S. (1997). “Numerical methods for estimation and inference in Bayesian VAR-models”. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 12(2), 99–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199703)12:2<99::AID-JAE429>3.0.CO;2-A

- Koop, G., & Potter, S. (2003). “Forecasting in large macroeconomic panels using Bayesian Model Averaging”, Staff Reports 163, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Lane, P. R., & Perotti, R. (2003). The importance of composition of fiscal policy: evidence from different exchange rate regimes. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9-10), 2253–2279. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00194-3

- Lang, M., & Krznar, I. (2004). Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Croatia Paper presented at the Tenth Dubrovnik Economic Conference, Dubrovnik, 23–26 June.

- Leeper, E. M., Sims, C. A., Zha, T., Hall, R. E., & Bernanke, B. S. (1996). “What Does Monetary Policy Do?”. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1996(2), 1–78. doi: 10.2307/2534619

- Lendvai, J. (2007). The Impact of Fiscal Policy in Hungary. European Commission, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Country Focus, IV(11).

- Litterman, R. (1986). Forecasting with Bayesian vector autoregressions - five years of experience. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 4, 25–38. doi: 10.1080/07350015.1986.10509491

- Lutkepohl, H., & Kratzig, M. (2004). Applied Time Series Econometrics. Cambridge University Press.

- Mançellari, A. (2011). Macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy in Albania: a SVAR approach”. Bank of Albania, Working Paper, 5/2011

- Mélitz, J. (1997). Some Cross-Country Evidence about Debt, Deficits and the Behavior of Monetary and Fiscal Authorities CEPR Discussion Paper No. 1653. London: Center for Economic Policy Research.

- Mertens, K., & Ravn, M. O. (2012). Empirical Evidence on the Aggregate Effects of Anticipated and Unanticipated US Tax Policy Shocks. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(2), 145–181. doi: 10.1257/pol.4.2.145

- Mirdala, R. (2009). Effects of fiscal policy shocks in the European transition economies. Journal of Applied Research in Finance, 1(2), 141–155.

- Mountford, A., & Uhlig, H. (2005). What Are the Effects of Fiscal Policy Shocks?, SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2005-039, Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- Muir, D., & Weber, A. (2013). Fiscal Multipliers in Bulgaria: Low But Still Relevant, IMF Working Paper WP/13/49. doi: 10.5089/9781475560473.001

- Mundell, R. A. (1963). Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Sciences, 29(4), 475–485. doi: 10.2307/139336

- Muscatelli, V. A., Tirelli, P., & Trecroci, C. (2002). “Monetary and Fiscal Policy Interactions over the Cycle: Some Empirical Evidence”, CESifo Working Paper Series, No. 817. Munich: CESifo Group.

- NBRM (2015). Quarterly report – November 2015, Skopje: National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia.

- Niehans, J. (1968). Monetary and fiscal policies in open economies under fixed exchange rates: An optimizing approach. The Journal of Political Economy, 76(4, Part 2), 893–920. doi: 10.1086/259457

- Pagan, A. R., & Pesaran, H. M. (2007). Econometric analysis of structural systems with permanent and transitory shock. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 32(10), 3376–3395. doi: 10.1016/j.jedc.2008.01.006

- Perotti, R. (2004). “Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries”, IGIER Working Paper 276, Milano: Universita Bocconi.

- Perotti, R. (2007). In search of the transmission mechanism of fiscal policy. In Acemoglu, D., Rogoff, K., and Woodford, M. (Eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2007. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ramey, V. A. (2011). Identifying government spending shocks: It's all in the timing. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 1–50. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjq008

- Ramey, V. A., & Shapiro, M. D. (1998). “Costly Capital Reallocation and the Effects of Government Spending”. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 48, 145–194. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2231(98)00020-7

- Ravnik, R., & Žilić, I. (2011). The use of SVAR analysis in determining the effects of fiscal shocks in Croatia. Financial Theory and Practice, 35(1), 25–58.

- Ritschl, A., & Woitek, U. (2000). Did monetary forces cause the Great Depression? A Bayesian VAR analysis for the U.S. economy, Working paper No. 50, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich.

- Romer, C. D., & Romer, D. H. (2010). The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: Estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. American Economic Review, 100(3), 763–801. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.3.763

- Rzonca, A., & Cizkowicz, P. (2005). Non-Keynesian Effects of Fiscal Contraction in New Member States. ECB Working Paper Series No, 519

- Rudebusch, G. D. (1998). Do measures of monetary policy in a var make sense?. International Economic Review, 39(4), 907–931. doi: 10.2307/2527344

- Rukelj, D. (2009). Modelling Fiscal and monetary policy interactions in croatia using structural vector error correction model. Economic Trends and Economic Policy, 121, 27–59.

- Serbanoiu, G. V. (2012). Transmission of fiscal policy shocks into Romania's economy. RePEc Archive, No. 4094, Munich Personal.

- Shambaugh, J. C. (2004). “The effect of fixed exchange rates on monetary policy”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 301–352. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839605

- Sims, C. A. (1980). “Macroeconomics and reality”. Econometrica, 48(1), 1. doi: 10.2307/1912017

- Sims, C. A. (1992). Interpreting the macroeconomic series facts: The effects of monetary policy. European Economic Review, 36(5), 975–1000. doi: 10.1016/0014-2921(92)90041-T

- Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2005). Implications of dynamic factor models for VAR analysis. NBER Working Paper No, 11467

- Stock, J., & Watson, M. (2006). Forecasting with many predictors. Handbook of Economic Forecasting, 1, 515–554. in Vol.

- Taylor, J. B. (2000). Reassessing discretionary fiscal policy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 21–36. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.3.21

- Uhlig, H. (2005). What Are the Effects of Monetary Policy on Output? Results from an Agnostic Identification Procedure. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52 (2), 381–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.05.007

- van Aarle, B., Garretsen, H., & Gobbin, N. (2003). Monetary and fiscal policy transmission in the Euro-area: evidence from a structural VAR analysis. Journal of Economics and Business, 55(5-6), 609–638. doi: 10.1016/S0148-6195(03)00056-0

- Wright, J. (2003). Forecasting U.S. Inflation by Bayesian Model Averaging, International Finance Discussion Papers 780, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Appendix 1: Unit root test results

Appendix 1: Unit root test results Table 1A. Unit root test results.