?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

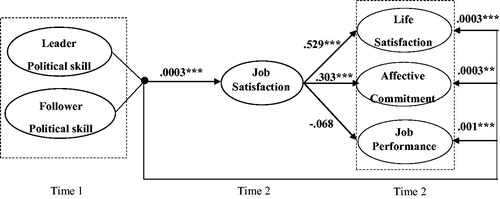

Based on existing research addressing political skill and social networks, this study explores the congruence effects of the political skills of leaders and followers on workers’ job satisfaction, and the resulting effect on followers’ life satisfaction and affective commitment. Using cross-level polynomial regressions and 3 D response surface analysis on 305 leader and follower dyads, the results supported the congruence and effect hypothesis. Furthermore, this study has also discovered incongruence effects: when leaders’ political skills are higher than those of their followers, the degree of decline in job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and affective commitment is greater than the size of difference between the political skills of leaders and followers. This study also reveals the importance of leaders and followers possessing political skills, especially considering its important effect on work attitude and performance.

1. Introduction

Political skill between followers and leaders has already received extensive empirical research attention (Dahling & Whitaker, Citation2016). Political skill is a kind of skill for conducting interpersonal interaction, and lies at the base of organisational operations. Organisation members use these kinds of skills to identify different opportunities in their work environment, and to make their work more efficient (Frederickson, Citation2006). Because of this, political skills can also cause positive work outcomes. Political skill refers to: ‘The ability to effectively understand others at work, and to use such knowledge to influence others to act in ways that enhance one’s personal and/or organisational objectives’ (Ferris et al. Citation2005, p. 127). Thus, interaction between people form linkages between social networks of different scales, and these kinds of linkages also become a kind of network relationship in their own right. According to the social network concept, human beings’ emotions and behaviour will influence organisation members’ commitment, work outcomes, and life satisfaction. As a result, whether organisation members are leaders or subordinates, they both display different levels of political skill at achieving objectives; furthermore, the organisational effects of the political skill inherent in the reactions of organisation members are subject to the increasing attention of many academics (Munyon, Summers, Thompson, & Ferris, Citation2015). Although there are many studies about political skill that explore one side’s effects on organisational performance, almost no attempt has been made to examine the dyadic interactive relationship of political skill between leaders and followers. As a result, scholars suggest that political skill is an important issue in strategic management.

Followers’ political skill predicts various individual and work outcomes, including subjective career success (e.g., Munyon et al., Citation2015), job performance (Dahling & Whitaker, Citation2016; Munyon et al., Citation2015), job satisfaction (Banister & Meriac, Citation2015), and leader effectiveness (Ewen et al., Citation2013). Leaders have an effect on employees’ job-related resources and evaluations. Thus, they can play a critical role in affecting employees’ psychology, as well as its outcomes. Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska, and Shaw (Citation2007) point out that individuals’ political skills in relationships will not only influence their tactics and performance, but perceptions will also influence their psychology. Hoch (Citation2013) contended that leaders might act differently according to followers’ behaviour, which can result in either positive or negative affective and performance evaluations. Therefore, in predicting work outcomes it is important to examine the interaction between employees’ and leaders’ political skills, rather than looking at leaders’ or followers’ political skills alone. Dyadic interaction in relationships and personality characteristics between leaders and followers has been shown to result in good work outcomes (Fang et al. Citation2015).

Leader and followers interact dynamically every day and the quality of interaction is related to the different degrees of influence for the followers' psychology. There are different emotional responses depending on followers’ cognition and awareness during their interactions with one another (Shi, Johnson, Liu, & Wang, Citation2013), which have a decisive influence on the management and development of an organisation (Dong, Seo, & Bartol, Citation2014). Organisation members often use political behaviours to achieve personal goals but this can also lead to negative responses of the follower.

There are several researches which have shown that job satisfaction has an effect on life satisfaction or on job performance and commitment (Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, Citation2001; Near, Citation1984; Yousef, Citation2000). However, research on job satisfaction antecedents and job satisfaction effects on work attitude and job performance has been an important issue (Judge & Larsen Citation2001). As a result, this study considers job satisfaction as a mediator variable, and explores the effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between political skill and work outcomes.

In this study, we examine the joint effects of leader and followers’ political skills on followers’ work outcomes (i.e., life satisfaction, affective commitment, and job performance). Drawing upon the literature on interpersonal social networks and dyadic goal interactions, we examine the effects of interaction on leader-follower practical skills concerning followers’ work outcomes that are mediated via job satisfaction. By hypothesising and testing the mediating effects of these relationships, we make three contributions.

First, based on the social network theory, we contribute to work on political skill by conceptualising the phenomenon of leaders matching followers in political skill to enhance work outcomes.

Secondly, we contribute to the theory and research on social network by explicitly examining a relationship that links leader-follower dyadic relationships (i.e., dyadic interaction in leader-follower political skill) to work outcomes. Prior research has typically examined the direct relationship between leader and follower work outcomes without delineating the underlying mechanisms. Here, we propose job satisfaction as the mediator and try to explicitly link the differing effects of interaction in leader and follower political skill to followers’ attitudes towards their job and their organisation, and their levels of job performance via this relationship-based mechanism. By exploring this mediating model, we provide a direct test that links leader-follower social networks to followers’ job satisfaction and work outcomes.

Thirdly, the study extends the job satisfaction literature by examining political skill interaction between follower and leader as antecedents of job satisfaction. Previous research in this area has ignored the effects of behaviour interaction between leader and follower (e.g., Ewen et al., Citation2013). Therefore, the effects on job satisfaction of interaction between leader and follower in traits related to workplace attitude, such as political skill (Banister & Meriac, Citation2015), remain to be examined. It is important to study traits related to individuals’ workplace attitude, because they are closely related to followers’ psychology and behaviours at work. We formulated dyadic goal interaction as the explanatory mechanism to hypothesise and test political skill interaction effects on job satisfaction. By doing so, we also enrich the theoretical mechanisms for job satisfaction development.

Overall, this study explores the effect of leader-follower political skill interaction on job satisfaction and work outcomes from a social network theory perspective. Examining the extent of political skill has both theoretical and practical importance. From a theoretical standpoint, the simultaneous interplay of political skill extends the dynamics of leader-follower relationships. Consequently, we suggested and tested the mediating model illustrated in and described below.

Table 1. The four different scenarios of congruence and incongruence in leader-follower political skill.

2. Leader–follower congruence and incongruence in political skill

Social networks are like galaxies formed by invisible lines of mutual attraction; furthermore, the network relationships that exists between people have different interactive modes that vary according to different nodes and distances; for this reason, distant relationships are formed slowly. Social networks refer to interactive social relationships formed between different individual units. The rapid development of online social media has caused the social networks to develop rapidly and dynamically, causing the relative importance of leaders and subordinates in networks to affect their relationships with one another. From a social network view, when an individual in a network develops influence, their network relationships become an important resource (Ferris, Perrewé, Anthony, & Gilmore, Citation2000).

Members of organisations interact with one another at different levels every day to conduct or complete responsibilities. This ability to influence others’ achievements of personal or organisational objectives is called political skill. Ferris, Treadway, Perrewé, Brouer, Douglas, and Lux (Citation2007) propose three levels of political skill: ) effect of political skill on oneself including internal psychological processes (personal resource development, personal objectives); 2) effect of political skill on others including interpersonal processes (effect on strategy, interpersonal networks, position, establishment of alliances), and 3) the effect of political skill on groups and organisations including group processes (establishing vision, team atmosphere, promoting team-mate interaction). Political skills are a manifestation of the construct of social effectiveness achieved through interpersonal patterns. In the workplace, organisational members understand social cues and contexts to influence the behavioural motivations of others, and thereby influence others’ ability to achieve individual or organisational objectives (Ferris et al., Citation2005; Treadway, Ferris, Duke, Adams, & Thatcher, Citation2007). Members of organisations use political skills as a means of achieving goals. They include four elements: networking ability (alliances, negotiations); apparent sincerity (e.g., displaying a friendly, honest, and positive image); interpersonal influence (the ability to influence or change others); and social astuteness (the ability to perceive and react to environmental changes) (Ferris et al., Citation2007). The ability of individuals to use these abilities related to political skills is manifested in interpersonal interactions within networks; we can see development and changes in interpersonal relationships through these kinds of interaction. Thus, we can see that political skill is a way of displaying abilities, and that the strength of this kind of skill will vary within organisations. This study will address different levels of political skills possessed by leaders and followers, and will present four different scenarios, as shown in : low-low; high-high; low-high; high-low. The former two scenarios are congruent, while the second two are incongruent. To explore the effect of political skill congruence on job satisfaction, we will address the following: first, whether job satisfaction is higher in the congruent than the incongruent scenario; secondly, whether, for the two congruent scenarios, job satisfaction is higher in the high-high scenario than the low-low scenario; next, we consider whether job satisfaction is higher in the two incongruent scenarios.

Political skill can be used to help individuals obtain better interpersonal interactions and network linkages within organisations, and to allow each individual to achieve psychological and physiological satisfaction. However, within organisational structures, the importance of leaders’ network relationships varies in importance from those of followers. This is because leaders play the role of resource allocators, and followers will use political skills to obtain resources. In addition to being able to respond to different social situations, individuals with political skills are also able to cleverly conceal self-serving intentions while being perceived as honest, and display a sense of self-confidence and attractiveness, thereby giving people a sense of security and trust. In other words, political skills provide positive influences for organisational members (Munyon et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, Meurs, Gallagher, and Perrewé (Citation2010) have conducted empirical research from the perspective of executives and employees, and have found that for both executives and employees, high levels of political skills result in lower interpersonal conflict and emotional exhaustion. Banister and Meriac (Citation2015) state that individuals with high political skill levels can adjust their performance of appropriate behaviour according to their environment. In other words, political skill can improve organisational climate, and thereby improve employees’ job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction not only relies on well-designed institutions but also involves employees with proactive personalities succeeding in work (Zhang, Wang, & Shi, Citation2012), just as Northouse (Citation2004, p. 151) said: ‘When leaders and followers have good exchanges, they feel better, accomplish more, and the organisation prospers’. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 1: Job satisfaction is higher when leaders and followers are congruent at a high level of political skill than when they are at a low, or incongruent, level.

There are two different situations in which the political skills of leaders and followers are incongruent: the first is when leaders have low levels of political skill and followers have high levels; the other is when leaders have high levels of political skill and followers have low levels. In organisations, when leaders have low levels of political skill and followers have high levels, leaders are not good at operating interpersonal networks. This will cause a decline in the influence of leaders over followers. However, followers with high levels of political skill can use network linkages to expand their own organisational or interpersonal influence, and thereby achieve their own objectives or organisational duties. Comparatively, when leaders have high levels of political skill and followers have low levels, leaders are good at establishing interpersonal network relationships to accelerate their accumulation of interpersonal social network and increase their organisational influence. However, followers with low political skill levels may be poor at or dislike interpersonal interaction as a result of personal qualities (introversion) or cognition (unrelated to work or interpersonal factors); if leaders overemphasise interpersonal interaction and network linkages, this may produce negative psychological or physical reactions for followers with low levels of political skill (for example, decreased job satisfaction) (Munyon et al., Citation2015). Thus, not all social networks are positive, and negative behaviours or resource deprivation may result from interaction between organisational members (Lin, Citation2005).

Individuals with political skills can bring positive development to organisational networks, but conversely, for comparatively sensitive organisation members, they may perceive the political skills of other organisation members and therefore have incongruent psychological levels (Marin & Miller, Citation2013). Treadway et al. (Citation2007) suggest that people with high political skills not only gain recognition from leaders but also improve their interpersonal relationships. Individuals with high political skills do not display selfishness or only care about themselves in social situations; instead, they do the right thing and people perceive their sincerity (Ferris et al., Citation2005). Conversely, members with low political skills may experience symptoms of unhappiness (Ferris et al., Citation2007). Individuals with high political skills acquire or maintain resources through a good network of relationships, and even benefit in business discussions and negotiations or when controlling and managing conflicts (Ferris et al., Citation2007). In other words, in order to effectively promote the organisation's policies, a leader uses different political skills to influence followers. However, followers may experience the most intense negative emotional responses if they disagree with such policies or are highly averse to the leader's high level of political skills, while not being able to apply political skills to gain the support of peers. It will be seen from this that followers’ political skill level plays a critical role to influence personal emotions and attitudes. In summary, we proffer Hypothesis 2: Job satisfaction is higher when followers have a higher level of political skill than leaders.

3. The mediating role of job satisfaction

Work is an important component of peoples’ lives, and job satisfaction is important to individuals’ attitudes and behaviours (Judge & Klinger, Citation2008). Many previous studies have noted that there is a positive correlation between job satisfaction and employees’ work outcomes; this is important for the success of employees in the workplace (e.g., life satisfaction, affective commitment, and job performance). Job satisfaction is a subjective conception and reaction to the work environment; this was first suggested by Hoppock, who defined job satisfaction as ‘any combination of psychological, physiological, and environmental circumstances that causes a person truthfully to say, ‘I am satisfied with my job’ (Hoppock, Citation1935, p. 47). We can learn from this that employees’ psychological and physiological satisfaction can improve their attitudes and organisational performance. Affective commitment refers to the emotional dependence of employees on the organisation, and their identification with and investment in it regarding both emotions and psychology; it also indicates their hard work, and willingness to continue to belong to the organisation. Affective commitment is primarily a result of employees’ deep emotional connection to the organisation, and not material benefits. Furthermore, employees’ affective commitment has the greatest effect on emotional linkages, investment, and identification with the organisation (Meyer and Allen, Citation1997). The relationship between job satisfaction and commitment has been a subject of interest and research because of its effect in the workplace and its impact on employee behaviour and attitudes. Shan (1998) stated that job satisfaction is a determinant of organisational commitment. Elangovan (Citation2001) found that lower job satisfaction leads to lower organisational commitment. Moreover, some research has indicated that there was more support for a causal link from job satisfaction to organisational commitment than for a path in the reverse direction (Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière, & Raymond, Citation2016; Williams & Hazer, Citation1986). In addition, empirical research suggested that job satisfaction is an important antecedent of affective commitment, i.e., job satisfaction has a significant positive impact on affective commitment (Chordiya, Sabharwal, & Goodman, Citation2017). Consequently, employees' job satisfaction has an impact on organisational commitment. In other words, when members of organisations become good partners, members will have happier moods (job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and affective commitment). This kind of invisible relationship network formed by psychological processes becomes a social resource that benefits the organisation (Lin, Citation2005). When members have good interaction in interpersonal networks, and are also able to easily complete their work, this produces a satisfying psychological effect and job satisfaction. Furthermore, this kind of satisfaction continues to drive members towards participation and investment, and brings them life satisfaction (Judge & Klinger, Citation2008; Yuan, Citation2016). Interpersonal networks also affect organisational performance and development (Ferris et al., Citation2007). To achieve their objectives, fulfil duties, or meet individual goals, leaders and followers will use different levels of social or political skills to once again attain influence or important advantages within interpersonal networks. When there is congruence in the organisational objectives of leaders and followers, this reduces disagreement and increases mutual understanding and attitude, thereby contributing to organisational performance. Considering previous empirical research, we see that when leaders and followers have similar objectives, this is positively correlated with life satisfaction (Yuan, Citation2016), affective commitment (Chordiya et al., Citation2017), and performance (Munyon et al., Citation2015).

In Hypothesis 1, we propose that the congruence of leaders’ and followers’ political skills affects workers’ job satisfaction, and establishes a positive correlation between job satisfaction and work outcomes. We also predict that at the level of job satisfaction, congruence affects followers’ life satisfaction, emotional commitment, and job performance. Thus, we establish that job satisfaction plays a mediating role. This mediating role is to magnify the importance of political skill congruence for organisational development and operation; this is because job satisfaction can strengthen the relationship of leaders and followers, and affect the work attitude and job performance of employees.

Furthermore, we propose that job satisfaction has a partial mediator effect because there may be other mechanisms at play affecting the direct effect of the congruence or incongruence of leader and followers’ political skill on work outcomes. For example, when leaders and followers have low and congruent levels of political skill, followers may enjoy their work, and have organisational commitment; this may not be due to job satisfaction, but rather a result of relatively low job requirements, and a relaxed work atmosphere. Furthermore, the congruence of political skill may result in direct benefits for followers’ job performance; this is because when leaders and followers have the same conception of objectives and responsibilities, conflict and consumption of organisational resources may be reduced (Meurs et al., Citation2010). Thus, the study uses job satisfaction as a mediator variable, and explores the effect of job satisfaction on political skills and work outcomes.

In summary, this study holds that political skill affects employee work outcomes (life satisfaction, affective commitment, and job performance) through the mediator of job satisfaction. Thus, we propose Hypothesis 3: The congruence/incongruence of leaders’ and followers’ political skill indirectly affects life satisfaction (H3a), affective commitment (H3b), and job performance (H3c) through the partial mediator effect of job satisfaction.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data and sample

This study used anonymous survey questionnaires to collect data and a convenience sampling strategy was employed. The participants were managers and full-time employees at Taiwanese chain tea-drinking stores. They are still working in the chain tea-drinking stores and they have had three months work together at least. The eligible member was identified by the human resources department. There were two reasons for choosing these subjects: first, Taiwan’s chain tea-drinking stores are a unique and developed industry, and its dense network of chain stores forms a unique social network, with each store being located directly opposite to a competitor, and facing diverse customer demands. The interaction behaviours or network relationships of store managers (i.e., leaders) and employees are therefore relatively dense. Secondly, because the work of chain tea-drinking stores is relatively particular about efficiency and performance, especially when facing a large number of orders, it is necessary to support one another, and so store managers and employees have relatively high levels of interaction, which reveals the importance of the effect of management behaviours on employees’ work attitudes.

To avoid the issue of common method variance, this study uses two points in time and corresponding questionnaires to conduct sampling. To collect data from store managers and employees at Time 1, we collected data on leaders’ political skill and followers’ political skill, and after three months, at Time 2, we collected data on job satisfaction, affective commitment, and life satisfaction. We also asked management to provide information on job performance at Time 2. Furthermore, because the objective was to explore the relationship of the political skill of store managers and employees, with job satisfaction, work attitude (life satisfaction and affective commitment), and performance, the study was limited to studying employees and managers with at least a three-month relationship, so that managers and employees more fully understand each other’s work behaviours.

The survey data was collected from five Taiwanese chain tea-drinking stores and these stores have more than 100 franchise outlets. We asked the store managers to agree with our research to reduce the difficulty of leader and follower match and increases the recovery rate of the questionnaires. Therefore, in this study, there are four people in each group (i.e., one leader and three followers) which satisfies the Carron and Spink (Citation1995) suggestion that each group needs three people at least. By contacting the management of each store, we collected 120 participants from the stores, and distributed 360 sets of surveys (each containing employee and management questionnaires). The questionnaire method used involves researchers explaining the objective and questionnaire process to staff, and guaranteeing the confidentiality of the questionnaire information. At Time 1, we distributed 360 management and employee questionnaires of which 324 were collected, to collect data related to political skills measurements. At Time 2, we provided the second questionnaires to the same employees surveyed at Time 1 to collect data on management assessment of employees. After eliminating questionnaires containing incomplete or blank responses, we collected 305 valid questionnaires, for a valid questionnaire retrieval rate of 84.72%. Within our sample, 183 employees were female (60%), and 122 were male (40%); 222 employees were aged 30 years or younger (72.8%); 179 were university graduates (58.7%), followed by 86 (28.2%) with high school. Most (200, 65.6%) had held their positions for one year or less, and most had spent time working with their manager for one year or less (199, 65.2%). Considering management, 39 managers were female (53.4%), most were under 30 years of age (42, 57.5%), and most had a university education (49, 67.1%). Forty had held their position for one year or less (54.8%), and 26 had been managers for 1–2 years (26, 35.6%).

4.2. Measures

All surveys used data collection points in Taiwan. Translation/back-translation procedures were followed to translate the English-based measures into Chinese. We used a 7-point response scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree = 1’ to ‘strongly agree = 7’ for all items.

Political skill. Political skill was measured with the Chinese version (see Chen & Lin, Citation2010) of the 15-item political skill inventory (PSI). Because the 18-point PSI scale proposed by Ferris et al. (Citation2005) was used to measure the relationships and interactions between part-time workers and students in the classrooms of a southern state-founded university in the United States, the subjects of this study are very different. Therefore, this study uses a Chinese version of the scale to avoid cross-cultural errors. We used a 7-point response scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree = 1’ to ‘strongly agree = 7’ for all items. This self-reported measure assessed respondents' perceptions of their own political skills. The 15 items in this scale were designed to reflect four dimensions of political skills. The four dimensions are networking ability (e.g., 'I have always prided myself in having good savvy, street smarts, or political skill at work'), apparent sincerity (e.g., 'I try to see others’ points of view'), social astuteness (e.g., 'In social situations, it is clear to me just what to say and do'), and interpersonal influence (e.g., 'I am able to make most people feel comfortable and at ease around me'). The reliability coefficient α for this scale was 0.94 for leaders and 0.92 for followers.

Job satisfaction. To measure job satisfaction, we adopted the 3-item Overall Job Satisfaction scale from Dubinsky and Hartley (Citation1986). A sample item is ‘I am generally satisfied with the kind of work I do in this job’ (reverse-coded) (α = .86).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale. To measure life satisfaction, we adopted the 5-item scale from Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin (Citation1985). A sample item is ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’ and ‘So far I have gotten the important things I want in life’ (α = .86).

Affective commitment. To measure this, we adopted the 8-item scale from Allen and Meyer (Citation1990). A sample item is ‘I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organisation’ and ‘I enjoy discussing my organisation with people outside it’ (α = .83).

Follower task performance. Leaders’ ratings of follower task performance were on a 7-item in-role behaviour scale (Williams and Anderson, Citation1991). A sample item is ‘My employee adequately completes assigned duties’ (α = .93).

Control variables. According to researcher recommendations, political skill and job satisfaction may be related to demographic characteristics. Thus, we controlled for age and gender using dummy variables (0 = male, 1 = female), in addition to using variables for education, and years working with manager (e.g., Ferris & Kacmar, Citation1992).

5. Analyses

Cross-level polynomial regression. In order to test congruence and incongruence effects (Hypotheses 1–3), we used cross-level polynomial regressions and response surface modelling (Edwards & Cable, Citation2009; Edwards & Parry, Citation1993). We used STATISTICA to analyse the data and plotted response surface graphs to present the polynomial regression results. This means that we use polynomial regression to test the effect of congruence and incongruence of leaders’ and followers’ political skill on job satisfaction. We also interpret the slope and curvature of the response surface to more accurately judge the results and patterns of these effects. We use EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) to estimate this:

(1)

(1)

where M stands for the mediator variable (i.e., job satisfaction), L is leader political skill, and F is follower political skill. Next, we use the regression coefficient results of this equation to plot a three-dimensional response surface (L and F are plotted on the X and Y-axes, and M is plotted on the vertical Z-axis). The response surface is determined using the results of multivariate regression, and represents the curvature and slope formed by congruence (i.e., L = F), and the curvature and slope formed by incongruence (i.e., L = –F).

The degree of congruence indicates that when the political skills of leaders and followers are equal, there is congruence (L = F), and when the political skills of leaders are higher or lower than those of followers, there is incongruence (L > F or L < F). Multivariate regression is used as an analytical tool to verify the effect of leader-follower political skill congruence or incongruence on job satisfaction, to understand the combined use of different predictive factors on outcome variables (Edwards & Parry, Citation1993). To avoid collinearity and improve the explanatory power of results, we centralise the political skills of leaders (L) and followers (F) before calculating second-order terms (L2, F2, L × F).

Furthermore, because this study’s hypotheses are related to mediator model verification (Hypotheses 4a–4c), and to more accurately determine the overall mediating effect of congruence and incongruence, block variable analysis (Edwards & Cable, Citation2009) is employed to combine the five variables in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) (L, F, L2, L × F, F2) into a single variable. We combine predictive regression variables and use bootstrapping to determine the significance and confidence interval of the mediating effect.

6. Results

presents descriptive statistics such as variables’ average value, standard deviation, correlation coefficients, and confidence interval. Gender and life satisfaction (r = −0.158, p < 0.01) are significantly correlated, while age, education, and dyadic tenure are significantly correlated with affective commitment (r = −.23, p < .001; r = .15, p < .01; r = .20, p < .001), but there are no significant correlations with either job satisfaction or the outcome variables. Follower political skill and job satisfaction(r = .362, p < .001), life satisfaction (r = .524, p < .001), and affective commitment (r = .305, p < .001) are all significantly and positively correlated, but are not significantly correlated with follower job performance (r = −0.02, p > .05). Apart from being significantly and positively correlated with follower job performance (r = 0.66, p < 0.001), leader political skill is not significantly correlated with other variables. Despite not being significantly correlated with follower job performance (r = 0.07, p > .05), job satisfaction is significantly and positively correlated with life satisfaction (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) and affective commitment (r = 0.33, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there is no significant correlation between leader political skill and follower political skill (r = −0.07, p > .05). From the above results, we find that job satisfaction is not significantly correlated with job performance, which varies from this study’s initial inferences.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables.

The measurement model’s reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity are displayed in . shows that the Composite Reliability (CR) is greater than .7 and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeds .5, which suggests good convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2010). In addition, also presents that the Maximum Shared Squared Variance (MSV) and Average Squared Variance (ASV) are lower than the AVE values, suggesting good discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Table 3. Reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity.

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses to examine the distinctiveness of the four follower self-reported variables (i.e., political skill, job satisfaction, affective commitment, and life satisfaction). To achieve the best ratio between sample size and number of estimated parameters, we use different factor models for different variable sets (six models in total), with different factor loads and different variable distributions, to compare model indicators, such as the statistical benchmarks and goodness of fit of Model 1 (hypothesised four-factor model), with other models. The comparative fit index (CFI) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) values are greater than or equal to .90 considered indicative of good fit (Hair et al., Citation2010). Moreover, the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) is less than 0.10 (Kline, Citation2011) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value less than or equal to 0.10 is considered ‘fair’ (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1989). presents the results of model fit comparison. The results of comparing the hypothesised four-factor model with alternative models shows that the hypothesised four-factor model has satisfactory fit (χ2 = 58.93, df = 15, p < .001, CFI = .96, GFI = .95, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .09). Furthermore, the hypothesised four-factor model is superior to the other five models, showing that the four variables chosen by this study have distinctiveness. Next, we used the results of confirmatory factor analysis to test relevant hypotheses.

Table 4. Model fit results for confirmatory factor analyses.

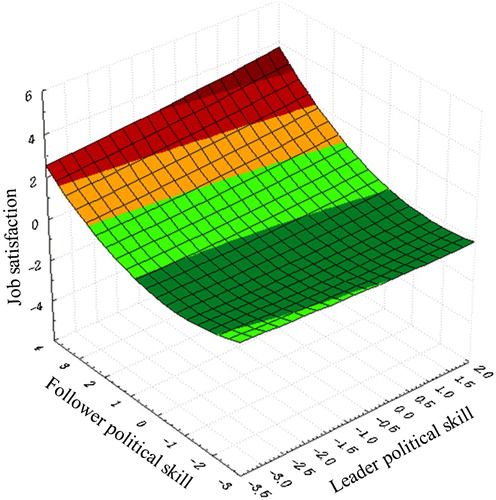

Hypothesis 1 suggests that job satisfaction is higher when leader-followers are congruent at the high level of political skill than they are at the low level or incongruent. The first column in shows estimations of job satisfaction and estimated coefficients according to cross-level polynomial regressions, in addition to slopes and curvatures for situations of congruence and incongruence. shows the mapping of the response surface according to these coefficients. As shown in , the surface along the incongruence line is significant and positive (curvature = .007, p < .10), and the three second-order polynomial terms are jointly significant in predicting job satisfaction (F = 6.818, p < .001). suggests that along the incongruence line, a U-shape is apparent (slope = 0.14, p < .001, Curvature = .007, p < .10). The incongruence line (F = –L) moves from the upper left to the bottom right corner, whereas the congruence line (F = L) moves from the front to the rear corner. The concave curvature along the F = –L line indicates that job satisfaction is higher when a follower’s political skill is aligned with his/her leader’s. However, when the congruence line is low and congruent, the level of employee job satisfaction is lower than the upper left corner of the incongruence line (i.e., when follower political skill is higher than leader), thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Figure 1. Congruence effect and incongruence effect of leader-follower political skill on job satisfaction.

Table 5. Cross-level polynomial regressions of job satisfaction and work outcomes on political skill congruence/incongruence.

We use a lateral shift to assess the incongruence effect of Hypothesis 2 (Edwards & Parry, Citation1993). The quantity showing the lateral shift is negative (−10), indicating a shift towards the region where L is greater than F. Thus, when the political skills of leaders are higher than those of followers, the degree of decline in job satisfaction is higher than when leaders’ political skills are lower than those of followers (slope = .140, p < .001; see ). Consequently, when a follower’s political skill is higher than his/her leader’s, job satisfaction decreases more sharply than it does when the follower’s political skill is lower than the leader’s; job satisfaction is higher when followers are at a higher level of political skill than leaders. We can see from the response surface in that job satisfaction at the left corner (F = 4 and L = −3.5) is higher than that in the right corner (F = −3 and L = 2). also shows that the slope is significant and positive (.140, p < .001), thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypotheses 4a–4c explains the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between leader-follower political skill congruence/incongruence and work outcomes. Therefore, we tested two models for each outcome variable (see ). In Model 1, first we control four various control variables (i.e., gender, age, education, and dyadic tenure), and predict the dependent variable by using five polynomial terms. In Model 2, we control the congruence and incongruence effects and add the job satisfaction variable to the regression to examine the effect of job satisfaction. Concerning the first path linking political skill, congruence and job satisfaction (see ), we used the block variable approach (Edwards & Cable, Citation2009) to obtain a single coefficient that represented the combined effect of leader and follower political skill on job satisfaction. We can see from Model 2 in that job satisfaction is a positive predictor of life satisfaction (β = .398, p < .001) and affective commitment (β = .230, p < .01), but that job satisfaction is insignificant for job performance. This means that when considering the effect of the block variable on work performance using the mediator of job satisfaction, there is no significant difference; thus, job satisfaction has no mediating effect on the relationship between the block variable and job performance.

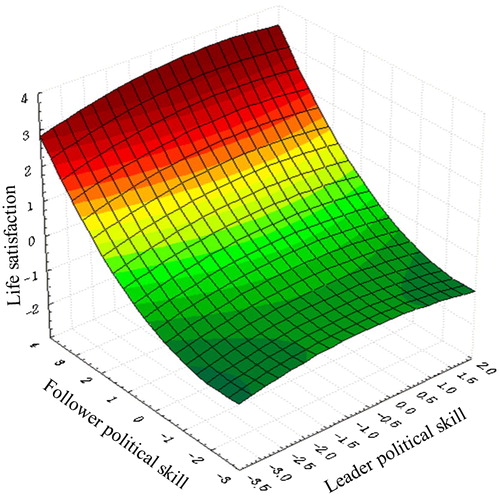

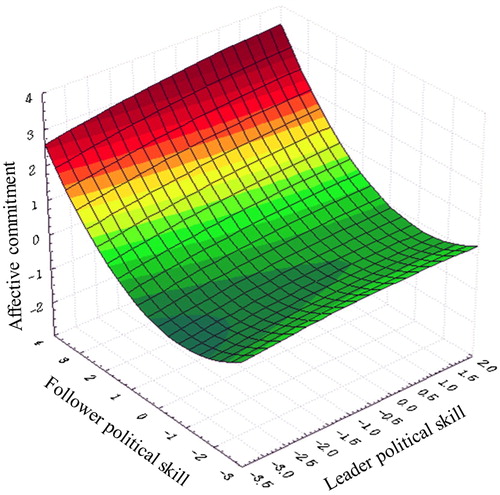

The unstandardised path coefficient of this combined effect on job satisfaction is .0003 (p < .001; see ). As shows, the regression coefficient for the effect of job satisfaction on life satisfaction is .529 (p < .001), the regression coefficient for affective commitment is .303 (p < .001), and the coefficient of the block variable (i.e., direct effect of congruence) in political skill on the outcome variables are all significant. The indirect effects of congruence via job satisfaction are significant for life satisfaction (.0002, p < .001, 95% CI = [.0001 .0003]), and affective commitment (.0001, p < .01, 95% CI = [.0000 .0000]). Taking both the direct and indirect effects into consideration, these results show that job satisfaction partially mediated the combined effects of leader–-follower political skill on followers’ life satisfaction (supporting Hypothesis 3a), affective commitment (supporting Hypothesis 3b), but not job performance (rejecting Hypothesis 3c). The related mediator models of congruence and incongruence are shown in and . Results are summarised in .

Figure 3. Congruence effect and incongruence effect of leader-follower political skill on life satisfaction.

Figure 4. Congruence effect and incongruence effect of leader-follower political skill on affective commitment.

Table 6. Results from Tests of Direct and Indirect Effect of Congruence/Incongruence in Political Skill on Work Outcomes.

In , we present the congruence and incongruence effect of leader and follower political skill on the response outcome of life satisfaction. The response outcome for the congruence effect follows the incongruence line as it slopes downwards, although this is insignificant (curvature = 0.005, n.s.). For the scenario of high/high congruence, life satisfaction is higher in the low/low congruence scenario; furthermore, this is significant (slope = .29, p < .001; see ). Concerning the incongruence effect, life satisfaction in the upper left corner (F = 4, L = −3.5) is higher than that of the bottom right corner (F = −3, L = 2). Furthermore, the later shift quantity is –30.3, showing that L shifts towards F. Thus, when the political skills of leaders are higher than those of followers, the degree of decline in life satisfaction is higher than when the leaders’ political skills are lower than those of followers (slope = .303, p < .001; see ).

In , we show the response outcome for congruence and incongruence effects of leader and follower political skill on affective commitment. In the surface of the congruence effect, the incongruence line is curved upward (curvature = .011, p < .05), showing a U-shape. In the high/high congruence scenario, affective commitment is higher than for the low/low scenario; this is significant (slope = .156, p < .001; see ). For the incongruence effect, life satisfaction in the upper left corner (F = 4 and L = −3.5) is higher than in the bottom right corner (F = −3 and L = 2). Furthermore, the lateral shift quantity is −5.6, showing that L shifts towards F; when the political skills of leaders are higher than those of followers, the degree of decline in affective commitment is larger than when the political skills of leaders are lower than those of followers (slope = .124, p < .01; see ). Overall, the pattern of effect on job satisfaction for the congruence and incongruence effects of leader-follower political skill on work outcomes (except job performance) is similar.

7. Discussion

From earlier literature and related empirical studies, we see that political skill has a positive effect on organisation members. However, researchers have yet to investigate the effect of political skills on the work outcomes of employees from the perspective of leader-follower political skill congruence. This study investigates the relationship between the political skills and work outcomes of organisation members. After surveying 305 employees and managers of chain tea-drinking stores, our empirical results show that when leaders’ and followers' political skills are high-high, life satisfaction and affective commitment are also higher. Furthermore, we find that job satisfaction also plays a mediator role in affecting life satisfaction and affective commitment. Thus, overall, political skill indirectly promotes employees’ work outcomes through its effect on job satisfaction.

Next, to understand the complexity of the effect of leaders’ and followers’ political skills on job satisfaction and work outcomes, we apply social network theory and propose the importance of levels of congruence and incongruence to understand the overall effect of political skill on work outcome. In this study, we integrate our two lines of research for congruence and incongruence, and expand theories and research related to political skill and interpersonal networks. Consistent with Banister and Meriac’s (Citation2015) research, we find that the political skills of leaders and followers have a positive effect on job satisfaction and a part of employees’ work outcomes. We also find that the effects of congruence on work outcomes are the indirect result of job satisfaction as a mediator; thus, congruence is correlated with high job satisfaction, and this in turn is correlated with high levels of life satisfaction and affective commitment. Furthermore, the different models for leader-follower political skill congruence and incongruence result in different degrees of positive and negative influence on job satisfaction. Specifically, the congruence of dyads at higher levels of political skill results in higher job satisfaction than congruence at lower levels. In view of the incongruence line, when leaders have higher levels of political skill than followers, the degree of decline in job satisfaction is larger than when leaders have lower levels of political skills than followers.

7.1. Theoretical implications

This study uses multivariate regression and response surface analysis methods (Edwards & Parry, Citation1993) and analyses the overall effects of the congruence of leader-follower political skill using a three-dimensional response outcome. Subsequently, we discuss possible interpretations that provide greater significance or detail. Several important theoretical points result. First, using social network perspectives, we see that there are dyadic relationships and interactions between the political skills of leaders and followers in organisations. Previous theoretical and empirical research (Banister & Meriac, Citation2015; Munyon et al., Citation2015) suggests that employees’ political skill improves their personal work attitudes or organisational performance, although these studies did not explore the dyadic relationship between leaders’ and employees’ political skills. This study’s results show that there are important effects resulting from followers’ political skills and work attitudes. This is similar to the argument of Harris et al. (Citation2007), which states that when leaders cannot demonstrate political skills or when these skills are poor, followers with high levels of political skills are more likely to receive performance affirmation from managers than followers with low levels of political skill; these followers also have better work attitudes (i.e., job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and affective commitment).

Secondly, we expand social network theory. Using the social network formed by the political skill existing between leaders and followers, we study the congruence and incongruence effects and their influence over work outcomes. Leaders control an organisation’s tangible and intangible resources, and can allocate these resources; thus, the political skills of leaders are a key factor affecting followers. However, if followers have high political skills, they can also create networking for themselves. Previous studies emphasise that high political skill levels have a positive effect on personal efficacy, job satisfaction, job performance, and organisational commitment (Munyon et al., Citation2015). This study supplements existing theory using congruence and incongruence mechanisms, and proposes that the effect on job satisfaction is based on a dyadic relationship, rather than the simple effects of independent influences. The primary contribution of this study is to use the simplest method for understanding the varying relationship of leaders’ and followers’ political skills and the effect of this relationship on work outcomes. The study can provide more specific support for related arguments.

Thirdly, we demonstrate that job satisfaction plays a partial mediator role between leader-follower political skill congruence and work outcomes. This confirmation allows us to use the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers as a mechanism for understanding the effects of social network on organisations. However, the study finds that job satisfaction does not play a mediator role between leader-follower political skill congruence and job performance, meaning that job satisfaction does not significantly affect job performance. Bakotić (Citation2016) argues that the link between job satisfaction and job performance is very weak, although many empirical studies have found that whether there is a significant correlation between employee work attitude and job performance remains a matter of academic debate (Judge et al., Citation2001). Herman (Citation1973) suggested that job satisfaction could be related to job performance only when employees are less in control of their workplace. However, there are many provisions and standard operation procedures in the industry of chain tea-drinking stores and the employees must comply with the rules. Therefore, employees’ freedom of autonomy and independence will be limited. On the other hand, the main effect of political skill is the influence of others’ tactics and performance (Frederickson, Citation2006; Harris et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, the congruence of political skill may result in direct benefits for follower job performance (Meurs et al., Citation2010). In addition, the job performance data here is provided by store managers; although the congruence of leaders’ and followers’ political skill (block variable) and the direct effect on job performance is significant (0.001, p < 0.001), the indirect effect on job performance of the block variable via job satisfaction is not significant, and its value is negative (−0.068, p > 0.05). Although job satisfaction has no mediating effect between political skills and job performance in this study, because of this, it is found that leaders and followers have different cognitive views of the organisation. shows that the mean of job performance (evaluation by leader), job satisfaction (follower self-report), and life satisfaction (follower self-report) was 2.06, 5.02, and 4.45, respectively. Thus, it is known that there is a gap in cognition about job performance and working atmosphere between leaders and followers. This shows that balancing high employee performance with employee satisfaction is an important issue on which leaders should focus. In summary, the relationships between leader-follower political skill and job performance are not mediated by job satisfaction. Considering organisational development, the objectives of leaders and followers using political skills are congruent. Leaders can also use political skills to prevent followers’ social networks from impeding organisational development.

7.2. Practical implications

We can see from the results of this study that the possession of political skill by leaders and followers brings positive development to organisations, and that whether leaders have political skills has a considerable effect on followers’ work attitudes. Thus, the behaviour of leaders affects the psychology of followers, and can affect their internal harmony. When leaders express confidence in followers and demonstrate good communication and interaction, this creates better emotions in followers; this psychologically emotive effect is directly reflected in work attitudes. In order to avoid leaders emphasising only job performance while overlooking employee satisfaction, leaders can move to improve employee job performance by increasing job satisfaction, through improving work characteristics, communication, and incentives (Ewen et al., Citation2013). This means that by providing a safe work environment, one can promote employee job satisfaction, and cause employees to feel that their well-being has improved; this is a management responsibility of leaders, as well as a moral responsibility.

From the results of this study, we find that when both leaders and followers have high levels of political skills, followers will display maximum job satisfaction and positive work attitude. Political skills can also be used in online social media (Ferris et al., Citation2000). The good use of social media by leaders, and the establishment of informal relationships with subordinates can reduce the distance between employees and strengthen their relationships; this is helpful for improving employee attitudes and investment in work, and promoting organisational development. Thus, shaping corporate culture and core values can strengthen employee confidence and promote mutual interaction and understanding among the organisation’s members. This also promotes cohesion of members’ common objectives, improves self-perception of the environment, increases members’ satisfaction, and helps to jointly improve organisational performance. Thus, when leaders actively develop their employees’ political skills and reduce the use of politics in decision-making, they can improve employees’ work efficiency, job satisfaction, and interpersonal and organisational development.

It is true that leaders often do not choose followers with political skills that are as advanced as their own. Comparatively, from the perspective of social network, they can play the role of lubricant inside and outside of the organisation; internally, they are often given the task of communicating or lobbying to complete a task. Externally, they establish good customer relationships and improve corporate image and reputation (Ferris et al., Citation2007). When leaders with high political skill levels lead employees with low political skill levels, we suggest that leaders communicate and interact with employees more, and allow employees to understand organisational objectives and visions, thereby reducing negative psychological pressure felt by employees, and improving the congruence of dyad objectives.

On the one hand, the industry of chain tea-drinking stores emphasises the organisation's standard operating procedures, but increases employees’ freedom of autonomy and independence, or formulates that merit pay is contingent on employees' performance, and this should enhance their job satisfaction and job performance (Herman, Citation1973). On the other hand, the industry has the characteristics of high interactivity with customers. Therefore, it is important to keep employees in a healthy state of mind so that theycan provide customers with good consumption experience and create good job performance. Thus, leaders should pay attention to the interaction with employees and observe their psychological or emotional changes, and provide appropriate assistance so that employees are willing to make more efforts for the organisation. Moreover, leaders help to establish positive interpersonal relationships that will not only bring positive behaviours and attitudes to individuals, but also enhance team cooperation and the degree of various tasks (Yuan, Citation2016). Therefore, it is an important role for leaders to motivate employees to achieve job performance according to their different characteristics in a pleasant working atmosphere (Vlacseková & Mura, Citation2017).

7.3. Limitations and future research

Taiwan’s chain tea-drinking stores are a unique industry globally, and have expanded to become international companies. Sampling was conducted using a stratified purposeful sampling method, and was limited by time and manpower. We utilised a time-lagged design (measuring the mediator variable and work outcome variable three months after the initial survey), derived research designs and empirical data from different sources, used multivariate regression and response surface methods for analysis, and explored topics related to political skill in organisations. Despite this study's contributions, there are some limitations.

First, among organisational tasks, in addition to the dyadic relationship of leaders and followers, management levels existing between managers and employees are very important, and many managers will use these middle management tasks to carry out their duties; in turn, the performance of employees will also reflect on managers through this middle management level. This means that the rank of employees is positively correlated with their performance (Zhang & Lin, Citation2016). Thus, we recommend future research to be conducted considering middle management tiers, and to be supplemented with discussions related to member network relationships.

Secondly, in addition to the mediating mechanism of job satisfaction, other mediating mechanisms also exist, such as the reward mechanism. Because some studies argue that the political skills of managers can be positively correlated with employee rewards (Dahling & Whitaker, Citation2016), and that rewards are an important factor for job satisfaction and performance (e.g., Ewen et al., Citation2013), we believe that deeper discussion will be generated if future studies explore other mediating mechanisms.

Thirdly, there are various ways in which members of organisations interact with one another as interaction can cause different changes according to different environments. The sample industry of this study belongs to the younger generation, and the combination of organisational networks therein is not conducted through traditional person-to-person interaction, but by interaction through virtual social networks. This interaction forms another kind of value and power within organisations; future studies can explore the effect of using political skills in virtual social networks on organisational atmosphere, job satisfaction, and work outcomes.

Fourthly, we suggest a ‘contact diary’ to be used directly to observe and record interactions and behaviours of organisation members on a microcosmic scale; this will reveal the state of political skill in network interaction and contact. Future studies can also use the four elements of political skill (Ferris et al., Citation2007) to directly assess the congruence and incongruence effects of leader-follower political skill, and reinforce the conclusions of this study.

Finally, the phenomenon investigated by this study exists in chain tea-drinking stores, which have the demographic characteristic of being relatively young. Although we can eliminate the possibility of being affected by age-difference factors, the cluster around a certain age bracket may still endanger the external validity of the findings. Thus, future studies may use a different industry, or a sample with different demographic characteristics to conduct verifications, and thereby confirm the degree of generalisation of this study’s conclusions.

8. Conclusions

In the literature, political skill can be helpful to employee psychology and employee outcomes. The results of this study confirm that leaders’ political skills are important for the effect of followers’ political skills on work attitude. With regard to the positive predictive power of high job satisfaction towards positive work outcomes, we observe that the congruence of leader and follower political skill is extremely important, rather than a simple observation of one party’s political skills.

Moreover, improving the political skills of employees can bring a variety of benefits to organisations. When the political skills of leaders and followers are congruent, this is an important factor in creating a good organisational atmosphere, and generating competitive advantages.

References

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Bakotić, D. (2016). Relationship between job satisfaction and organisational performance. Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 118–130. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2016.1163946

- Banister, C. M., & Meriac, J. P. (2015). Political skill and work attitudes: A comparison of multiple social effectiveness constructs. The Journal of Psychology, 149(8), 775–795. doi:10.1080/00223980.2014.979127

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1989). Single sample cross-validation indices for covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(4), 445–455. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2404_4

- Carron, A. V., & Spink, K. S. (1995). The group size-cohesion relationship in minimal groups. Small Group Research, 26(1), 86–105. doi:10.1177/1046496495261005

- Chen, T. L., & Lin, C. Y. (2010). Verification and analysis of political skill scale in organizations. Chung Hua Journal of Management, 11(1), 59–77.

- Chordiya, R., Sabharwal, M., & Goodman, D. (2017). Affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction: A cross-national comparative study. Public Administration, 95(1), 178–195. doi:10.1111/padm.12306

- Dahling, J. J., & Whitaker, B. G. (2016). When can feedback-seeking behavior result in a better performance rating? Investigating the moderating role of political skill. Human Performance, 29(2), 73–88. doi:10.1080/08959285.2016.1148037

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dong, Y., Seo, M. G., & Bartol, K. M. (2014). No pain, no gain: An affect-based model of developmental job experience and the buffering effects of emotional intelligence. Academy of Management Journal, 57(4), 1056–1077. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0687

- Dubinsky, A. J., & Hartley, S. W. (1986). A path-analytic study of a model of salesperson performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 14(1), 36–46. doi:10.1177/009207038601400106

- Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 654–677. doi:10.1037/a0014891

- Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. doi:10.2307/256822

- Elangovan, A. R. (2001). Causal ordering of stress, satisfaction and commitment, and intention to quit: a structural equations analysis. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(4), 159–165. doi:10.1108/01437730110395051

- Ewen, C., Wihler, A., Blickle, G., Oerder, K., Ellen, B. P., Douglas, C., & Ferris, G. R. (2013). Further specification of the leader political skill–leadership effectiveness relationships: Transformational and transactional leader behavior as mediators. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(4), 516–533. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.03.006

- Fang, R., Landis, B., Zhang, Z., Anderson, M. H., Shaw, J. D., & Kilduff, M. (2015). Integrating personality and social networks: A meta-analysis of personality, network position, and work outcomes in organizations. Organization Science, 26(4), 1243–1260. doi:10.1287/orsc.2015.0972

- Ferris, G. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (1992). Perceptions of organizational politics. Journal of Management, 18(1), 93–116. doi:10.1177/014920639201800107

- Ferris, G. R., Perrewé, P. L., Anthony, W. P., & Gilmore, D. C. (2000). Political skill at work. Organizational Dynamics, 28(4), 25–37. doi:10.1016/S0090-2616(00)00007-3

- Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Kolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C. J., Douglas, C., & Frink, D. D. (2005). Development and validation of the political skill inventory. Journal of Management, 31(1), 126–152. doi:10.1177/0149206304271386

- Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Perrewé, P. L., Brouer, R. L., Douglas, C., & Lux, S. (2007). Political skill in organizations. Journal of Management, 33(3), 290–320. doi:10.1177/0149206307300813

- Frederickson, P. J. (2006). Political skill at work. Academy of management perspectives, 20(2), 95–96. doi:10.5465/amp.2006.20591018

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., Zivnuska, S., & Shaw, J. D. (2007). The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 278–285. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.278

- Herman, J. B. (1973). Are situational contingencies limiting job attitude—job performance relationships?. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 10(2), 208–224. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(73)90014-7

- Hoch, J. E. (2013). Shared leadership and innovation: The role of vertical leadership and employee integrity. Journal of Business and Psychology, 28(2), 159–174. doi:10.1007/s10869-012-9273-6

- Hoppock, R. (1935). Job Satisfaction. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Judge, T. A., & Klinger, R. (2008). Job satisfaction: Subjective well-being at work. In M. Eid & R. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 393–413). New York: Guilford Publications.

- Judge, T. A., & Larsen, R. J. (2001). Dispositional affect and job satisfaction: A review and theoretical extension. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 67–98. doi:10.1006/obhd.2001.2973

- Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.127.3.376

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3th ed.). New York & London: The Guilford Press.

- Lin, N. (2005). A network theory of social capital. In D. Castiglione, J. Van Derth & G. Wolleb (Eds.), Handbook of Social Capital. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Marin, T. J., & Miller, G. E. (2013). The interpersonally sensitive disposition and health: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(5), 941–984. doi:10.1037/a0030800

- Mathieu, C., Fabi, B., Lacoursière, R., & Raymond, L. (2016). The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. Journal of Management & Organization, 22(1), 113–129. doi:10.1017/jmo.2015.25

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Meurs, J. A., Gallagher, V. C., & Perrewé, P. L. (2010). The role of political skill in the stressor–outcome relationship: Differential predictions for self- and other-reports of political skill. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 520–533. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.01.005

- Munyon, T. P., Summers, J. K., Thompson, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (2015). Political skill and work outcomes: A theoretical extension, meta‐analytic investigation, and agenda for the future. Personnel Psychology, 68(1), 143–184. doi:10.1111/peps.12066

- Near, J. P. (1984). Relationships between job satisfaction and life satisfaction: Test of a causal model. Social Indicators Research, 15(4), 351–367. doi:10.1007/BF00351444

- Northouse, P. G. (2004). Leadership: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Shi, J., Johnson, R. E., Liu, Y., & Wang, M. (2013). Linking subordinate political skill to supervisor dependence and reward recommendations: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 374. doi:10.1037/a0031129

- Treadway, D. C., Ferris, G. R., Duke, A. B., Adams, G. L., & Thatcher, J. B. (2007). The moderating role of subordinate political skill on supervisors’ impressions of subordinate ingratiation and ratings of subordinate interpersonal facilitation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 848–855. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.848

- Vlacseková, D., & Mura, L. (2017). Effect of motivational tools on employee satisfaction in small and medium enterprises. Oeconomia Copernicana, 8(1), 111–130. doi:10.24136/oc.v8i1.8

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. doi:10.1177/014920639101700305

- Williams, L. J., & Hazer, J. T. (1986). Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: A reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 219. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.71.2.219

- Yousef, D. A. (2000). Organizational commitment: A mediator of the relationships of leadership behavior with job satisfaction and performance in a non-western country. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(1), 6–24. doi:10.1108/02683940010305270

- Yuan, H. (2016). Structural social capital, household income and life satisfaction: The evidence from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong-Province, China. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 569–586. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9622-z

- Zhang, Y., & Lin, N. (2016). Hiring for networks: Social capital and staffing practices in transitional China. Human Resource Management, 55(4), 615–635. doi:10.1002/hrm.21738

- Zhang, Z., Wang, M. O., & Shi, J. (2012). Leader–follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 111–130. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0865