Abstract

Enhancing intercultural effectiveness through the development of intercultural skills and competencies substantially contributes to establishing a more peaceful and tolerant society, which explains a considerable research interest it excites. The present study aims at investigating how study field, grade-point average (GPA), nationality, gender, university status, and grade level impact intercultural effectiveness of Bosnian university-level students. The research sample consisted of 184 students studying at the Departments of English Language and Literature and Psychology at three different universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A 2 × 4 ANCOVA indicated that intercultural effectiveness varied significantly by study field and GPA, with small effect size in both cases. The interaction effect of study field x GPA was also significant, with an almost moderate effect size. Similarly, a two-way MANOVA revealed that nationality and gender had a significant effect on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness and their interaction effect was also significant, with a small effect size. On the other hand, a two-way MANOVA revealed an insignificant impact of grade level and university status on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness. The interaction effect of grade level x university status was also insignificant, with a small effect size. The present study shows that intercultural effectiveness can be further developed and increased in the university milieu and is thus expected to contribute to recognising the importance of its enhancement through curricula and teaching content in particular.

1. Introduction

Bosnia and Herzegovina is imbued with cultural diversity, as different ethnic groups, namely Bosniaks (50, 11%), Croats (15, 43%) and Serbs (30, 78%), as well as adherents to various religions, Islam, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Judaism, reside in unique togetherness and intersect at different levels. Thus, due to its religious diversity, Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is often referred to as European Jerusalem. However, in the course of history, in particular in the nineties of the last century, this immense diversity was a major source of bigotry and intolerance leading to massive destruction, whose repercussions are felt even today. Thus, the country is still considered to be an intriguing case (Tiplic & Welle-Strand, Citation2006) due to the fact that it is deeply divided, either geographically, as it is composed of two entities, the Republic of Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with 10 cantons and one district, or ideologically, as the impact of the unfortunate events on the youth of different ethnic backgrounds is felt even today and its impact seems to be profound (Kasumagic, 2008).

1This geographical, and to some extent, ideological disunity has contributed to the fact that there are currently three educational systems implemented in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which are based on different curricula and textbooks adjusted to the preferences of dominant ethnic groups. Thus, young generations are nourished within a largely monoethnic environment. The education policy is framed on the cantonal level in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and on the entity level in the Republic of Srpska, with a separate education policy adopted in the Brčko District. However, the law on education enacted at all levels explicitly requires that the rights of different others be respected and that tolerance be promoted and segregation and discrimination entirely eliminated. As changes and improvements in education may lead a country into ensuring social cohesion and development (Kasumagic, Citation2008), acquiring specific intercultural skills, competencies and attitudes may significantly impact the process of reconciliation and may encourage tolerance and acceptance of culturally different others (Bećirović, Citation2012; Bećirović, S. & Brdarević Čeljo, A. Citation2018).

Thus, this paper aims to explore intercultural effectiveness among university-level students in Bosnia and Herzegovina, randomly selected from different strata. Since intercultural effectiveness is considered to be one of the three inextricably related dimensions of intercultural communication competence (Portalla & Chen, Citation2010), it, together with the other two dimensions, namely, intercultural awareness and intercultural sensitivity, substantially contributes to the establishment of a more effective communication in culturally diverse societies in particular, and thus helps to establish a more tolerant and peaceful environment. Hence, the results of this study will offer a profound insight into intercultural effectiveness in Bosnian tertiary-level education and provide a broader perspective by recommending further actions to be taken to enhance intercultural effectiveness, and, consequently, to facilitate intercultural communication.

Thus, in the Literature Review Section a conceptual definition of our research problem as well as an overview of similar research studies are presented and in the Methodology section a detailed description of the participants, measures, procedure and data analysis are provided. Afterwards, the results are presented, followed by discussion which includes limitations and suggestions for further research. At the end, concluding remarks are presented.

2. Literature review

Cultural as well as other types of diversity exist in today’s world and cultural mixing has intensified in the last few decades with the increase in population movements often caused by disasters and conflicts, economic and other reasons. With the rapid development of information technologies, a need arose to establish different ways of communication and cooperation with people from diverse cultural backgrounds and the world has become a global village. In order for communication and cooperation to be effective and productive, people need to have higher levels of intercultural intelligence and intercultural competencies.

According to Brislin (Citation1993), culture is developed by people and it includes mutual values, beliefs and assumptions about life and serves as a guiding force affecting people’s behaviour. Culture is transmitted across generations and people are mutually connected by means of encoding and decoding messages (Ulrey & Amason, Citation2001) and through different types of verbal and non-verbal communication (Kim, Citation1988). While defining intercultural effectiveness, many scholars tend to focus on intercultural competence or ability (Mamman, Citation1995a,Citationb). According to Chen and Starosta (Citation1996), intercultural effectiveness and intercultural communication competence are very frequently used incoherently by scholars whereby intercultural effectiveness refers to the behavioural aspect of intercultural communication competence and to intercultural adroitness which corresponds to intercultural communication skills that may help individuals to achieve their goals in interactions with culturally diverse others (Portalla & Chen, Citation2010). This definition is in line with Brislin, Cushner, Cherrie, and Yong (Citation1986), who believe that the effectiveness of interactions is a function of meeting needs and goals through communication. To meet needs and achieve goals in rather diverse societies, one must foster intercultural awareness, sensitivity and competencies. Brislin et al. (Citation1986) claimed that being interculturally effective means being at ease about communication and collaboration with culturally diverse people (Gudykunst, Citation1995). Hammer, Gudykunst, and Wiseman (Citation1978) pointed out that intercultural effectiveness is composed of three abilities: (1) the ability to deal with psychological stress, (2) the ability to communicate effectively, and (3) the ability to establish interpersonal relationships, while Stone (Citation2006) identified eight essential elements of intercultural effectiveness: emotional intelligence, knowledge, motivation, openness, resilience, reflectiveness, sensitivity, and skills.

With the world becoming the“global village”, it is necessary to establish close contacts and effective cooperation with culturally diverse people and develop intercultural competencies that will contribute to increasing intercultural effectiveness which may trigger a more active and effective participation in social activities. Young people need to be prepared to actively and effectively participate in increasingly culturally diverse societies in the twenty-first century and educational systems play a crucial role in that respect (Nussbaum, Citation2002). University-level students in particular have to acquire intercultural skills and competencies needed for effective interactions in a markedly plural society. Thus, a need exists to encourage the development of such competencies through education as the collaboration with people from different cultures has become a necessity (Deardorff, Citation2004). Labruffe (Citation2005) believes that intercultural competence has vital importance in today’s globalised world due to the fact that it is a crucial factor for establishing successful communication and it is the ability to understand, analyse and adapt to cultural differences. Some scholars (Le Boterf, Citation1994) emphasise the role intercultural competencies have in an international environment. However, due to the fact that communication through modern technology is widespread, people constantly experience an intercultural environment, and thus acquiring intercultural competencies is vital for effective interactions.

Research on intercultural education is largely focused on teaching practice and conditions that contribute to intercultural competencies such as the inclusion of specific courses and the student and teaching staff exchange. Research results mainly suggest that the educational practice has crucial importance in decreasing prejudices and increasing intercultural sensitivity as well as knowledge about other cultures and capacity for successful communication (King, Perez, & Shim, Citation2013). Educational systems need to provide opportunities for the development of intercultural awareness and sensitivity among students. Besides enabling and fostering an intercultural environment, teaching practice must focus on the development of intercultural skills and competencies, which implies moving from intercultural awareness and sensitivity to intercultural effectiveness (Salo-Lee, Citation2006). Thus, developing intercultural competencies and effectiveness through higher education is particularly important. Apart from its contribution to social harmony and establishing a better cooperation with the different others, it will also enable and improve the mobility of teachers and students, which is strongly encouraged through ERASMUS programmes. Besides, one of the most crucial tasks of university is research, which cannot be successfully conducted without effective international cooperation. Today's universities are acquiring an international dimension by implementing teaching in English with the underlying goal of attracting international students. Due to the fact that student mobility has been facilitated in the last few decades, a large number of students from different parts of the world attend universities across Europe and the United States. The efficacy and productivity of those universities will be significantly limited if they do not provide intercultural environment and do not encourage the development of intercultural competencies, as intercultural competencies play a crucial role in learning and teaching English, the global lingua franca (Demircioğlu & Çakir, Citation2016). Thus, the curricula and syllabuses need to be enriched by elements developing intercultural competencies and students’ international-mindedness. Moreover, Penbek, Yurdakul, and Cerit (Citation2009) also showed that students’ respect towards other cultures increases with the increase in the number of their intercultural interactions and numerous research studies have also indicated that different factors such as gender, age, studying abroad etc., impact intercultural competencies. Moreover, research results of Spencer-Oatey and Xiong (Citation2006) on Chinese students’ experience in Great Britain revealed that intercultural interaction was the most challenging factor in the students’ efforts to cope in a new social environment. In this respect, research has also shown that local students may be very helpful to international students in their sociocultural and psychological adjustments to a new culture and in the development of intercultural communication and at the same time in reducing stress and overcoming difficulties they encounter in a foreign country (Redmond & Bunyi, Citation1993). Jung (Citation2002) and Hismanoglu (Citation2011) pointed out that studying abroad has a positive effect on the development of intercultural competencies; however, an international student must acculturate in order to perform properly and efficiently and to achieve notable success (Yamaguchi & Wiseman, Citation2003). According to Jayasuriya, Sang, and Fielding (Citation1992), students’ educational level and their effort to learn the language of the country they want to adapt to are two significant factors contributing to their sociocultural and psychological adjustment during their stay in a foreign country and might contribute to intercultural effectiveness. Wilson (Citation2011) revealed that international students “struggle and strive” in a foreign country and try to overcome those problems by increasing flexibility and adaptability (Bodycott & Lai, Citation2012). Other scholars like Bochner, McLeod, and Lin (Citation1977) also pointed out that international students establish wide networks and collaborate with various groups at university, which helps them in their sociocultural and psychological adjustments, e.g., they mingle with local students to develop their language ability and at the same time they communicate and collaborate with their conationals to receive emotional support, strengthen their cultural identity and increase their self-esteem (Al-Sharideh & Goe, Citation1998; Maundeni, Citation2001). Even though conational groups provide solid support in foreign countries, research shows that such social enclaves might have a negative impact on developing intercultural effectiveness as they reduce the person’s need to socialise and tie with host nationals (Kim, Citation2001). Thus, Ward and Searle (Citation1991) pointed out that fostering strong relationships with conationals strengthens the person’s cultural identity but negatively impacts their intercultural communication and ability to adapt to a new environment.

Bosnia and Herzegovina attracts a lot of international students from different parts of the world, mostly from Turkey, Arabic countries and other countries of the Balkan region. Most of these students study at recently established private universities together with Bosnian students of different ethnicity. Studying in such a culturally diverse educational milieu creates unique opportunity for communication and interaction with persons of different cultural backgrounds. Due to the determining role intercultural effectiveness has in achieving effective intercultural communication, exploring its levels as well as the impacting factors is of vital importance. Thus, the main purpose of this research was to examine how study field, GPA, nationality, gender, university status and grade level are related to intercultural effectiveness in tertiary education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Using participants’ university status, nationality, gender, grade level and GPA as independent variables, students’ intercultural effectiveness was explored. Therefore, the following hypotheses were tested:

Intercultural effectiveness will differ significantly by the participants’ study field and GPA when the influence of age is controlled. For the same reason, we hypothesise that there will be a significant interaction effect of study field × GPA on intercultural effectiveness when the influence of age is controlled.

Combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness will differ significantly by gender and nationality. Likewise, we hypothesise there will be a significant interaction effect of gender × nationality on combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness.

Combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness will differ significantly by grade level and university status. Furthermore, we expect a significant interaction of grade level x university status on combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The stratified random sampling method was employed in the process of participants’ selection and 184 students were selected as participants from three universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina: 57 participants from a public university, 69 students from a private university and an additional 58 participants from another private university. The public university participants come from Bosnia and Herzegovina and belong to different ethnic and religious groups described above. The participants studying at two private universities mainly come from Bosnia and Herzegovina and other countries from the Balkan region as well as from Turkey. The research sample consists of 123 female and 61 male students with a mean of age M = 21.6 and standard deviation SD = 3, among whom 109 participants are of Bosnian nationality and 75 participants are of Turkish nationality. Students of Turkish nationality study at two private universities. The participants are students at different grade levels at the Departments of English Language and Literature (127) and Psychology (57) and the sample comprises four groups of participants based on their GPA, namely group 1 with GPA 5.00–6.9, group 2 with GPA 7.0–7.9, group 3 with GPA 8.0–8.9, and group 4 with GPA 9.0–10. A full description of the research sample is provided in .

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of participants.

3.2. Measures and procedures

The Intercultural Effectiveness Scale (IES), developed and validated by Portalla and Chen (Citation2010) was employed in this study. Thus, the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale (IES) used in this study includes the following subscales: Behavioural Flexibility (four items), Interaction Relaxation (five items), Interactant Respect (three items), Message Skills (three items), Identity Maintenance (three items) and Interaction Management (two items). An example item of Behavioural Flexibility is “I am afraid to express myself when interacting with people from different cultures” and an example item for the Interaction Relaxation scale is: “I find it is easy to talk with people from different cultures”. Moreover, an example item for the Message Skills scale is: “I often miss parts of what is going on when interacting with people from different cultures”, whereas an example item for the Interactant Respect scale is “I always show respect for the opinions of my culturally different counterparts during our interaction”. The example items for the Interaction Management scale and the Identity Maintenance scale are “I am able to answer questions effectively when interacting with people from different cultures” and “I always feel a sense of distance with my culturally different counterparts during our interaction” respectively.

The Inventory consists of 20 statements and a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The instrument showed the internal consistency reliability (α = ‒0.78) as well as its subscales, namely Behavioural Flexibility (α = ‒0.73), Interaction Relaxation (α = ‒0.82), Interactant Respect (α = ‒0.76), Message Skills (α = ‒0.89), Identity Maintenance (α = 0.69) and Interaction Management (α = ‒0.78). The instrument contains two sections. Section A contains items related to demographic variables and Section B contains items related to intercultural effectiveness. The data about participants’ GPA was collected through students’ self-report statements. Based on the grading system used in Bosnian higher education, the minimum possible grade is 5 and the maximum 10.

After obtaining informed consent, the inventory was administered to the students in classrooms, and the researchers clearly explained to the students how to complete the inventory. The average time spent on completing the inventory was about 15 minutes.

3.3. Data analysis

In order to analyse the data gathered from the participants, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23.0, was used. Descriptive statistics in terms of means, standard deviations, and frequencies were employed. The hypotheses were tested by applying inferential tests. Since all the assumptions were met, the Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) and the two-way multivariate analysis of variance (two-way MANOVA) were employed. In order to measure an effect size, Eta squared was performed.

4. Results

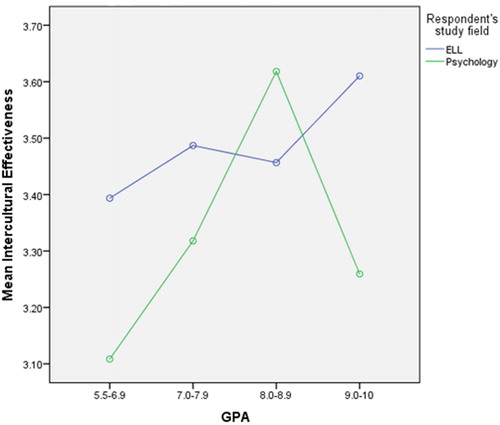

A 4 × 2 analysis of covariance was conducted to determine the effect of study field and GPA on intercultural effectiveness with the influence of age controlled. Independent variables were study field (English language and literature and Psychology) and GPA (four levels). The covariate was age. Intercultural effectiveness varied significantly by study field F (1, 162) = 4.99, p = .027, η2 = .030, however, with a small effect size. presents the summary of ANCOVA results. The comparison of adjusted group means, as displayed in , reveals that students from the study field of English language and literature demonstrate a significantly higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the students from the study field of psychology. Likewise, intercultural effectiveness varied significantly by GPA F (3, 162) = 2.70, p = .048, η2 = .048. The multivariate effect size is also small, tending to be moderate. A comparison of adjusted group means, as displayed in , reveals that intercultural effectiveness increases with the increase of GPA. However, the students from GPA-based group 3 demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the students from three other GPA-based groups as displayed in . The interaction effect of study field x GPA was also significant F (3, 162) = 2.84, p = .040, η2 = .050, with an almost moderate effect size. The covariate of age did not significantly influence the dependent variable of intercultural effectiveness F (1, 162) = .007, p = .936, η2 = .000.

Table 2. ANCOVA Summary Table.

Table 3. Adjusted and Unadjusted Group Means for Intercultural Effectiveness.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of variance of intercultural effectiveness between gender-based groups.

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of variance of intercultural effectiveness between nationality-based groups.

Table 6. Multivariate analysis of variance of intercultural effectiveness between public and private university students.

A two-way MANOVA was conducted to determine the influence of nationality and gender on intercultural effectiveness (overall) and its subscales, namely the Behavioural Flexibility, Interaction Relaxation, Interactant Respect, Message Skills, Identity Maintenance and Interaction Management subscales. Nationality included two levels (Bosnian and Turkish students) as did gender well (female and male participants). A two-way MANOVA revealed that nationality, Wilks’ Lambda λ = ‒0.765, F (24, 594) = 1.97, p = .002, η2 = .065, and gender Wilks’ Lambda λ = 0.918, F (6, 170) = 2.55, p = .022, η2 = .082 had a significant effect on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness. The interaction effect of nationality x gender was also significant Wilks’ Lambda λ = ‒0.828, F (18, 481) = 1.89, p = .018, η2 = .061 with a small effect size.

Univariate ANOVA tests were conducted as follow-up tests. Gender was shown to have a significant effect only on the Interactant Respect subscale F (1, 175) = 9.17, p = .003, η2 = .050 and an insignificant effect on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (1, 175) = 3.05, p = .083, η2 = .017, the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (1, 175) = 0.940, p = .334, η2 = .005, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (1, 175) = 1.88, p = .173, η2 = .011, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (1, 175) = 0.694, p = .406, η2 = .004 and the Interaction Management subscale F (1, 175) = 0.167, p = .683, η2 = .001 as displayed in .

There was a significant main effect of nationality only on the message skills subscale F (4, 175) = 3.55, p = .008, η2 = .075. However, there was no significant main effect of nationality on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (4, 175) = 0.871, p = .483, η2 = .020, the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (4, 175) = 0.827, p = .510, η2 = .005, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (4, 175) = 1.12, p = .348, η2 = .025, the Interactant Respect subscale F (4, 175) = 1.89, p = .116, η2 = .041, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (4, 175) = 1.55, p = .191, η2 = .034 or the Interaction Management subscale F (4, 175) = 0.725, p = .576, η2 = .016 as displayed in .

The interaction effect of gender × nationality was significant on the Message Skills subscale F (3, 175) = 5.27, p = .002, η2 = .083, the Interactant Respect subscale F (3, 175) = 2.75, p = .045, η2 = .045, and the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (3, 175) = 2.66, p = .050, η2 = .044, while there was no significant interaction effect of gender x nationality on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (3, 175) = 2.21, p = .089, η2 = .036, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (3, 175) = 0.32, p = .812, η2 = .005, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (3, 175) = 0.602, p = .614, η2 = .010 and the Interaction Management subscale F (3, 175) = 0.068, p = .977, η2 = .001.

A two-way MANOVA was also conducted to determine the influence of grade level and university status on intercultural effectiveness (overall) and its subscales, namely the Behavioural Flexibility, Interaction Relaxation, Interactant Respect, Message Skills, Identity Maintenance and Interaction Management subscales. Grade level included four study years (first, second, third, and fourth), and university status two types (private and public university). A two-way MANOVA revealed an insignificant influence of grade level Wilks’ Lambda λ = ‒0.925, F (18, 484.146) = 0.754, p = .754, η2 = .026, and university status Wilks’ Lambda λ = ‒0.986, F (6, 171.000) = 0.400, p = .878, η2 = .014 on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness. The interaction effect of grade level x university status was also insignificant Wilks’ Lambda λ = ‒0.947, F (18, 484.146) = 0.519, p = .949, η2 = .018 with a small effect size.

Univariate ANOVA tests were conducted as follow-up tests. There was no significant main effect of grade level on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (3, 176) = 0.665, p = .575, η2 = .011, as well as on any of the subscales of intercultural effectiveness, namely the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (3, 176) = 1.747, p = .159, η2 = .029, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (3, 176) = 0.197, p = .898, η2 = .003, the Interactant Respect subscale F (3, 176) = 0.241, p = .868, η2 = .004, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (3, 176) = 0.844, p = .472, η2 = .014, the Interaction Management subscale F (3, 176) = 0.887, p = .449, η2 = .016, and the Message Skills subscale F (3, 176) = 0.567, p = .638, η2 = .010. Likewise, there was no significant main effect of university status on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (1, 176) = 1.080, p = .300, η2 = .006, the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (1, 176) = 0.755, p = .386, η2 = .004, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (1, 176) = 0.090, p = .765, η2 = .001, the Interactant Respect subscale F (1, 176) = 0.068, p = .794, η2 = .000, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (1, 176) = 1.046, p = .308, η2 = .006, the Interaction Management subscale F (1, 176) = 0.24, p = .878, η2 = .000, and the Message Skills subscale F (1, 176) = 1.641, p = .202, η2 = .009 as displayed in . The interaction effect of university status × grade level was insignificant on intercultural effectiveness (overall) F (3, 176) = 0.128, p = .944, η2 = .002, as well as the Behavioural Flexibility subscale F (3, 176) = 0.648, p = .585, η2 = .011, the Interaction Relaxation subscale F (3, 176) = 0.384, p = .764, η2 = .007, the Interactant Respect subscale F (3, 176) = 0.425, p = .735, η2 = .007, the Identity Maintenance subscale F (3, 176) = 0.226, p = .878, η2 = .004, the Interaction Management subscale F (3, 176) = 0.158, p = .924, η2 = .003, and the Message Skills subscale F (3, 176) = 0.304, p = .822, η2 = .005.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The first hypothesis stating that intercultural effectiveness will differ significantly by study field and GPA with the age influence controlled and that there will be a significant interaction effect of study field and GPA on intercultural effectiveness when the influence of age is controlled was supported. Study field was shown to have a significant impact on intercultural effectiveness and the students at the Department of English Language and Literature demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the students studying at the Department of Psychology. One of the reasons for such research results might be found in the curriculum itself, as the curriculum followed at the Department of English Language and Literature incorporates the courses which develop students’ competences and skills facilitating communication with the culturally different and thus contribute to increasing intercultural effectiveness. In addition to that, the students at the Department of English Language and Literature, among other things, learn how to communicate effectively and how to develop communication skills and competences. Students are believed to have fully developed those skills when enabled to communicate with culturally different people, which is directly reflected on their communication competence and efficiency as well as on their intercultural effectiveness. Despite the fact that studying in the field of psychology also enables students to recognise others’ psychological states and emotions, which might be directly reflected on their communication efficiency and might facilitate their communication with the culturally different others, still the students at the Department of English Language and Literature were shown to acquire significantly more intercultural effectiveness skills than the students at the Department of Psychology.

The results also indicated that GPA had a significant impact on intercultural effectiveness, as it increased with the increase in the students’ GPA. The students with the lowest GPA (Group 1 and 2) had the lowest level of intercultural effectiveness, while the students with a higher GPA had a higher level of intercultural effectiveness. However, the students with the highest GPA (group 4) had a slightly lower level of intercultural effectiveness than the students with a lower GPA, i.e., the students from Group 3. These results are in line with the aforementioned claim that the existing curricula do include content which can contribute to increasing intercultural effectiveness. They also indicate that curricula and the related teaching content play an essential role in the development of intercultural effectiveness. The ANCOVA results showed that GPA and study field interacted and contributed to the development of intercultural effectiveness, whereas the covariate of age did not significantly affect the dependent variable of intercultural effectiveness. Moreover, the results also indicated that study field and GPA, individually or in interaction, had a significant impact on intercultural effectiveness.

The second hypothesis assuming that the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness will significantly differ by gender and nationality and that there will be a significant interaction effect of gender x nationality on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness was also supported as the impact of gender and nationality on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness as well as the interaction effect of nationality and gender on those combined variables was significant. The results of our research are in line with the research conducted by Collier (Citation1989), which indicated that nationality impacts the outcome of intercultural interaction. Moreover, they are partially consistent with the results of the research conducted by Morales (Citation2017), which also revealed that nationality has a significant effect on intercultural effectiveness. However, our results differ slightly from those of Morales (Citation2017), since the international student participating in that study demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the local Korean student participants. Likewise, when gender differences are observed, our research results do not seem to corroborate Morales’ (2017) results which suggest that gender does not significantly impact intercultural sensitivity, but they are in line with Mamman (Citation1995a,Citationb) and Demircioğlu and Çakir (Citation2016), who maintain that gender is a relevant variable with a significant impact on intercultural sensitivity. Besides, the findings of the current study do not seem to confirm the results presented in Demircioğlu and Çakir (Citation2016), who measured the level of intercultural sensitivity of the participants from the UK, Turkey, Spain, and Mexico and found no significant differences among the participants in that respect.

Furthermore, gender had a significant main effect only on two subscales, namely the Interactant Respect and Message Skills subscales and in both cases the female participants demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the male participants. Likewise, the female participants exhibited a higher level of intercultural effectiveness on the Behavioural Flexibility, Identity Maintenance and the Interaction Relaxation subscales, but those differences were not significant. Such results could be explained by the widely accepted theory suggesting that females are more sensitive than males (Bećirović, Citation2017) and this could be one of the reasons why they display greater sensitivity in their interactions with culturally different others and consequently score higher on the intercultural effectiveness scale than male students. On the other hand, the male participants demonstrated an insignificantly higher level of intercultural effectiveness only on the Interaction Maintenance subscale, which indicates that they maintain slightly better interactions with persons of different cultural backgrounds than the female participants. Our results partially corroborate the results of Matveev (Citation2002) and Mirzaei and Forouzandeh (Citation2013), which did not find any relationship between gender and intercultural sensitivity.

Nationality was shown to have a significant impact only on the Message Skills subscale, with Bosnian students demonstrating a significantly higher level of intercultural effectiveness than Turkish students. Bosnian students demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness on the Behavioural Flexibility, Interactant Respect, Identity Maintenance and Interaction Relaxation subscales, whereas Turkish students exhibited an insignificantly higher level of intercultural effectiveness only on the Interaction Management subscale. Such results point to an interesting finding that, overall, Bosnian students demonstrate a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than Turkish students, despite the fact that Turkish students in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the research was conducted, have the status of international students and have more international experience than Bosnian students and were thus expected to demonstrate a higher level of intercultural effectiveness. One of the reasons for such results might be found in the fact that Bosnia and Herzegovina is a very culturally diverse country, the area of Sarajevo in particular. Thus, young people living in this area have come to the realisation that respect for the culturally different brings many benefits while discrimination and segregation might lead to unfortunate events caused by cultural differences which have unfolded in this area at different times through history. Furthermore, gender and nationality interacted and significantly impacted the Message Skills, Interactant Respect and Behavioural Flexibility subscales.

The third hypothesis suggesting that the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness will significantly differ by grade level and university status and that grade level x university status will have a significant interaction effect on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness was rejected as the grade level and university status were not shown to have a significant impact on the combined dependent variables of intercultural effectiveness, individually or in interaction. Grade level and university status did not have a significant main effect on any of the intercultural effectiveness subscales. Although students at higher grade levels demonstrated a higher level of intercultural effectiveness than the students at lower grade levels, grade level had no significant impact on intercultural effectiveness. It is particularly interesting that the university status did not impact intercultural effectiveness, as the sample included students from two international universities, who were expected to demonstrate a higher level of intercultural effectiveness. However, the public university students demonstrated a higher mean on all the subscales except for the Interaction Management subscale where the mean was identical. If these results are linked and compared with the results measuring the impact of nationality on intercultural effectiveness then they seem rather compelling as private universities host a large number of Turkish students, who demonstrated a lower level of intercultural effectiveness than local Bosnian students. This is in line with the Demircioğlu and Çakir’s (Citation2016) study, which also revealed that there existed no significant difference in intercultural sensitivity between students from public and private schools as well as between students at different grade levels.

The results of this research seem to indicate that higher education curricula in different scientific disciplines and at different levels ought to incorporate the content promoting intercultural effectiveness as well as peace, tolerance, understanding and the acceptance of the culturally different. Kasumagić (Citation2008) offers a rather similar suggestion and maintains that young people can be assisted in developing intercultural effectiveness through specifically designed curricula promoting peace and civic engagement and through the use of appropriate teaching methods aiming to treat post-traumatic stress disorders and encourage multicultural understanding and dialogue. Unfortunately, cultural differences existing in this area have often led to numerous social problems, wars, territorial divisions, and other means of destruction. Thus, incorporating the content encouraging the development of intercultural effectiveness into the existing curricula in the Balkan region, in Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular, is a need and necessity, as young people have to be prepared to live in peace and harmony and to accept cultural differences as an asset and not as a problem. Hence, cultural and other differences will not pose obstacles for their scientific, cultural, technical and economic progress, the ultimate goal of all the inhabitants of this country irrespective of their ethnicity, religion, nationality, gender, age etc.

This research includes few limitations and these limitations should be taken into account as suggestions for further research into this matter. The first limitation is the number of universities selected for the conduction of research. Since three universities that are located in two out of ten cantons are included in participants’ selection and since the unfortunate happenings at the end of the twentieth century in this area caused population mobility and created highly monoethnic areas dominated by one of the three major ethnic groups, namely Bosniaks, Croats or Serbs, it would be very useful to include a larger number of universities from different parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina in further research and get a broader insight into intercultural effectiveness in Bosnian university-level education.

Furthermore, despite the fact that the research sample comprising students from two different fields, namely the fields of English Language and Literature and Psychology, provides a considerable insight into the level of intercultural effectiveness of those students, the inclusion of participants from other fields in any further research would provide broader perspectives and a broader and more profound understanding of intercultural effectiveness in Bosnian tertiary education. An additional suggestion for future research is the inclusion of university professors in the research sample. Due to the fact that their beliefs and attitudes might have a substantial impact on research into intercultural effectiveness, future studies ought to focus on measuring the level of intercultural effectiveness among university professors as well as the relationship between the professors’ and their students’ intercultural effectiveness.

References

- Al-Sharideh, K. A., & Goe, W. R. (1998). Ethnic communities within the university: An examination of factors influencing the personal adjustment of international students. Research in Higher Education, 39(6), 699–725.

- Bećirović, S. (2012). The role of intercultural education in fostering cross-cultural understanding. Epiphany Journal of Transdisciplinary Studies, 5(1), 138–156.

- Bećirović, S. (2017). The relationship between gender, motivation and achievement in learning english as a foreign language. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 6(2), 210–220. doi:10.13187/ejced.2017.2.210

- Bećirović, S. & Brdarević Čeljo, A. (2018). Exploring and assessing cross-cultural sensitivity in Bosnian Tertiary education: Is there a real promise of harmonious coexistence? European Journal of Contemporary Education, 7(2), 244–256.

- Bochner, S., McLeod, B. M., & Lin, A. (1977). Friendship patterns of overseas students: A functional model. International Journal of Psychology, 12(4), 277–294. doi:10.1080/00207597708247396

- Bodycott, P., & Lai, A. (2012). The influence and implications of Chinese culture in the decision to undertake cross-border higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(3), 252–270. doi:10.1177/1028315311418517

- Brislin, R. (1993). Understanding culture’s influence on behavior. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace.

- Brislin, R. W., Cushner, K., Cherrie, C., & Yong, M. (1986). Intercultural interactions: A practical guide. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1996). Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis. Communication Yearbook, 19, 353–384. doi:10.1080/23808985.1996.11678935

- Collier, M. J. (1989). Cultural and intercultural communication competence: Current approaches and directions for future research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 13(3), 287–302. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(89)90014-X

- Deardorff, D. K. (2004). In search of intercultural competence. International Educator, 14, 1–3.

- Demircioğlu, S., & Çakir, C. (2016). Intercultural competence of students in International Baccalaureate world schools in Turkey and Abroad. International Education Studies, 9(9), 1–14.

- Gudykunst, W. B. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8–58). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hammer, M. R., Gudykunst, W. B., & Wiseman, R. L. (1978). Dimensions of intercultural effectiveness: An exploratory study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2(4), 382–393. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(78)90036-6

- Hismanoglu, M. (2011). An investigation of ELT students’ intercultural communicative competence in relation to linguistic proficiency, overseas experience and formal instruction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 805–817. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.09.001

- Jayasuriya, L., Sang, D., & Fielding, A. (1992). Ethnicity, immigration and mental illness: A critical review of Australian research. South Carlton, Australia: Bureau of Immigration Research.

- Jung, J. Y. (2002). Issues in acquisitional pragmatics. Working Papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics, 2, 1–34.

- Kasumagic, L. (2008). Engaging youth in community development: Post-war healing and recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Review of Education, 54(3-4), 375–392. doi:10.1007/s11159-008-9095-y

- Kim, Y. Y. (1988). Communication and cross-cultural adaptation: An integrative theory. Philadelphia, PA: Multilingual Matters.

- Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781452233253

- King, P., M., Perez, R., J., & Shim, W. (2013). How college students experience intercultural learning: Key features and approaches. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6(2), 69–83. doi:10.1037/a0033243

- Labruffe, A. (2005). Management_des_compétences: Construire votre référentiel. Saint Denis La Plaine, France: AFNOR.

- Le Boterf, G. (1994). De la compétence. Essai sur un attracteur étrange. Paris: Les Editions d’Organisation.

- Mamman, A. (1995a). Expatriates’ intercultural effectiveness: Relevant variables and implications. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 33(1), 40–59. doi:10.1177/103841119503300103

- Mamman, A. (1995b). Socio-biographical Antecedent of Intercultural Effectiveness: The neglected Factors. British Journal of Management, 6, 79–114.

- Matveev, A. V. (2002). The perception of intercultural communication competence by American and Russian managers with experience on multicultural teams (Unpublished PhD thesis). Athens, OH: Ohio University.

- Maundeni, T. (2001). The role of social networks in the adjustment of African students to British society: Students’ perceptions. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 4(3), 253–276. doi:10.1080/13613320120073576

- Mirzaei, A., & Forouzandeh, F. (2013). Relationship between intercultural communicative competence and L2-learning motivation of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 42(3), 300–318. doi:10.1080/17475759.2013.816867

- Morales, A. (2017). Intercultural sensitivity, gender, and nationality of third culture kids attending an international high school. Journal of International Education Research, 13(1), 35–44. doi:10.19030/jier.v13i1.9969

- Nussbaum, M. (2002). Education for citizenship in an era of global connection. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 21(4/5), 289–303. doi:10.1023/A:1019837105053

- Penbek, D., Yurdakul, D., & Cerit, A. G. (2009). Intercultural communication competence: A study about the intercultural sensitivity of university students based on their education and international experiences. Paper presented at the European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems, in Izmir, Turkey, July 13 to 14, 2009.

- Portalla, T., & Chen, G. M. (2010). The development and validation of the intercultural effectiveness scale. Intercultural Communication Studies, XIX(3), 21–37.

- Redmond, M. V., & Bunyi, J. M. (1993). The relationship of intercultural communication competence with stress and the handling of stress as reported by international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17(2), 235–254. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(93)90027-6

- Salo-Lee, L. (2006). Intercultural competence in research and practice. Challenges of globalization for intercultural leadership and team work. In N. Aalto, & E. Reuter (Eds.), Aspects of intercultural dialogue. Theory, research, teaching (pp. 79–92). Köln. Saxa-Verlag.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., & Xiong, Y. (2006). Chinese students’ psychological and sociocultural adjustments to Britain: An empirical study. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(1), 37–53. doi:10.1080/07908310608668753

- Stone, N. (2006). Conceptualising intercultural effectiveness for university teaching. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(4), 334–356. doi:10.1177/1028315306287634

- Tiplic, D., & Welle-Strand, A. (2006). Bosnia-Herzegovina’s higher education system. European Education, 38(1), 16–29. doi:10.2753/EUE1056-4934380101

- Ulrey, K. L., & Amason, P. (2001). Intercultural communication between patients and health care providers: An exploration of intercultural communication effectiveness, cultural sensitivity, stress, and anxiety. Health Communication, 13(4), 449–463. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1304_06

- Ward, C., & Searle, W. (1991). The impact of value discrepancies and cultural identity on psychological and sociocultural adjustment of sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 15(2), 209–224. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(91)90030-K

- Wilson, H. F. (2011). Passing propinquities in the multicultural city: The everyday encounters of bus passengering. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(3), 634–649. doi:10.1068/a43354

- Yamaguchi, Y., & Wiseman, R. L. (2003). Locus of control, self-construals, intercultural communication effectiveness, and the psychological health of international students in the United States. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 32, 227–245.