Abstract

The aim of the article is to assess changes in the perception of the state by students in the context of research concerning social capital. The paper studies whether the knowledge and the social competences gained during the three years of study are reflected in the perception of the state by young people. The paper uses the results of a survey analysis conducted at the universities in Poland and Lithuania. The theoretical part of the article presents chosen issues concerning social capital in relation to the state. The article presents conclusions regarding the assessment of changes in the perception of the state by young people in Poland and Lithuania in the context of democracy, social participation, trust and social norms. This research enables us to make a comparison of the results between the two countries and from two research periods and is an original contribution to the discussion about the role of the young generation in society. The results of the research indicate that the knowledge and the social competencies acquired during three years of study in most cases were not reflected in the change of perception of the state by Polish and Lithuanian young people.

1. Introduction

The main aim of the paper is an assessment of changes in perception of the state by students (young people) in Poland and Lithuania in context of research on social capital. Several aspects have been taken into account. First, the student-to-democracy ratio, as a political institution of the state and basis for civil society. This allows citizens governance and oversight of state institutions. Second, the trust of the surveyed young people towards state authorities (public/political trust). If it exists at the local and central level, the effects of the institutions' actions are more effective and more predictable. Third, the respecting social norms by administration and government. It raises the level of trust in the governing institutions. If society recognises that in public administration, workers are ethical, then institutions function better and society is more willing to do things for the common good; and fourth, the creation of social solidarity, where the role of state institutions is leading, the individual interest is subordinate to the social interest. So when analysing perception of the state authors treats state as a society (citizens, democration) and as the authority (local and central government).

Literature shows that there are some correlations between the state and social capital, and civil engagement is associated with the level of social capital (Dowley & Silver, Citation2002; Hooghe & Marien, Citation2013; Maloney & van Deth, 2010; Newton, Citation2001; Stolle, Hooghe, & Micheletti, Citation2005). There are also some relationships between social capital and education (Anderson, Citation2008; Leeves, Citation2014; Pishghadam & Zabihi, Citation2011). Social capital positively affects educational achievement and, consequently, students’ behaviour and development among others (Acar Citation2011; Ho, Citation2003; Israel, Beaulieu, & Hartless, Citation2001). On the other hand, education makes young people aware of the possibility of social participation and provides opportunities to build a network of relationships outside the immediate environment based on common standards and trust (Balatti & Falk, Citation2002). An interesting research question arises here whether the period of educational study influences the perception of the state (the society and the authority) by the respondents. For this reason, the authors decided to check this research problem at work.

In this paper, the study was conducted amongst young people of two countries, i.e., Poland and Lithuania. The choice of countries for the study was due to several reasons. The first argument is history, the understanding being that both countries are from the group of previous socialist states. In the 1990s, Central and Eastern Europe countries experienced institutional and economic changes, democration formation. It renewed the interest in the power of civic engagement Stolle and Howard (Citation2008), besides institutional change and democratic politics may foster the creation of social capital to a certain degree (Torcal & Montero, Citation1998, p. 5) and lead to changes in trust, particularly political trust (Maloney & Van Deth, 2010). On the other side, the literature shows that in last few decades in Western societies there was observed a decline in political trust and democracy (Armingeon & Guthmann, Citation2014; Norris Citation2001), and similar tendencies are also observed in postcommunist states (Nikolayenko, Citation2005). It is assumed that the approach to social cohesion and public institutions by young people in both countries may be similar. The second are the political and economic changes that have taken place in both countries in the last 25 years, and especially since 2004 when the EU accession took place. The European Union, its bodies, encourages citizens of the Member States to be active and involved in citizenship with the EU institutions. Another reason is that both countries are from the same geographical area. The fourth argument was the desire by the authors to compare young people with similar study profiles.

The last is the fact that the results of research conducted in both countries for the general population indicate that the perception of the state by people is generally negative and people have low social participation. Polish people have little civic experience, which is gained through activities in organisations, participation in civic initiatives, public meetings or volunteering. For example, only 13.4% of Polish people are members of ‘organizations, associations, political parties, committees, councils, religious groups, unions or circles’ (among young people aged up to 24, 10.7%) (Czapiński, Citation2015, p. 342). Besides only one in five Polish people (19.4%) actively participates in public meetings outside the workplace (Czapiński, Citation2015, p. 345). Less than two-fifths of Polish people express their confidence in the government (38.0%), the Sejm and the Senate (30.0%), and one fifth (20.0%) in political parties (CBOS, Citation2016, p. 13). However the trust into public institutions (political institutions, charities, religious institutions, international organisations, mass media) is the highest among young people (trust indicator in the public sphere among people aged 18–24 is 13.5 but in whole population is 12.8, in scale 0–24). Over one-third of the respondents (35.0%) do not find any political group that would express their views, care about their interests or meet expectations, but among young people this share is 44.0% (CBOS, Citation2014, p. 4, 6). The lack of public trust in public institutions is also observed in Lithuania. In Lithuania, only 24.5% of the population trust the government, 11.6% Parliament and 6.3% political parties. The vast majority of the population do not trust these institutions (respectively 34.1%, 58.3% and 64.9%) (Vilmorus, Citation2017). It is worth adding that both countries surveyed are characterised by a similar level of trust in central and local government as in other European countries, what is confirmed by survey data of Eurofound (Citation2016). For Poland, Lithuania, Germany, France and Spain, trust in central government among young people (aged 18–24) is respectively (in %): 3.9, 5.8, 5.6, 4.0, 3.6, and average for whole population, respectively: 4.3, 4.6, 5.4, 3.9, 3.5. Trust in the local authorities among young people is respectively (in %): 5.2, 6.8, 6.1, 5.5, 5.3, and average for whole population, respectively: 5.3, 5.8, 6.2, 5.9, 5.1. However, in Poland trust in government and local authorities among young people is lower than average in whole society. In other European countries political trust among the young generation is higher than the average.

The article consists of several parts. The first is the introduction, where the main assumptions of the article are presented. Next is the theoretical part, where the issues of social capital and trust, especially in the aspect of the role of the state, are discussed. Another part is the methodology. The work was based on the survey tool, statistical methods of time changes and statistical verification of the results by the help of U Mann-Whitney test and difference between two population proportions test. Next is the empirical part where the research results were presented. The research was conducted on a group of students studying economics at two universities: in Szczecin (Poland) and in Vilnius (Lithuania). The data used in the paper is part of the research on the students’ social capital made by employees of the Department of Macroeconomics at the Faculty of Economics and Management University of Szczecin. The target selection of respondents was to assess changes among young people during the academic study, therefore for the purpose of the research, students of the first and the last year of Bachelor’s degree study were selected. The authors would also like to underline that the formulated proposals concern only the studied groups of young people and not the whole population.

The authors are aware of the limitations of this survey. The fact that it involved a selective group of students at universities implies that these findings cannot be generalised. In addition, the results of the research are limited due to the fact that in studied period there have been presidential, parliamentary and local elections in the countries in which the research was done.

The limitation is also the lack of data that would allow to directly determining the level of students’ knowledge of first and third-year study. However, it was assumed that the level of knowledge of students of the third year of study is higher than students of the first year of study. This results from the need to implement learning outcomes consistent with the Bologna system.

Previous literature has been primarily concerned with the study of the relationship between education and social capital, factors influencing social capital, on the trust level, including political trust, on democracy and on political behaviour, such as participation, civil engagement. The authors of the article, in the context of research on social capital, examine how young people in Poland and Lithuania perceive the state (as a society and as the authority). The attention of the authors is focused on the evaluation of democracy by the surveyed young people, the importance of their voice in society, social participation, trust in the authorities, honesty of the employees of public institutions and its activities. In addition, it is examined whether the economic knowledge and the social competences gained during three years of study in economic sciences are reflected in the perception of the state by young people. These elements have not been studied in the literature so far. This research, enables us to make a comparison of the results between the two countries and from two research periods and is an original contribution to the discussion about the role of the young generation in society. This way, an interesting research question is verified here whether the period of economic academic education affects their perception of the state (the society and the authority) among the respondents.

In contrast to other authors the article does not recognise the relationship between social capital and the perception of the state by students. However, the article is an important voice in the discussion about changes in the perception of the state by young people in the context of research concerning social capital because it enables us to make a comparison of the results between two countries and from two research periods.

2. Social capital, state – selected theoretical issues

In literature there are many approaches to the concept of social capital (Hawkins & Maurer, Citation2010). From the point of view of the purpose of the article and the research interests of the authors, the sociological-social and economic approaches deserve special mention. The first of them emphasises the role of social norms and the sources of human motivation, emphasising the importance of features such as trust and networks of civic engagement. A strand in the political science literature emphasises the role of institutions, political and social norms in shaping human behaviour (OECD, Citation2001, p. 40). The economic approach assumes people striving to maximise their welfare by interacting with others and drawing on social capital resources to conduct various types of group activities ( Glaeser, Citation2001, In: OECD, Citation2001, p. 40 ).

The approaches outlined above shows that the essence of social capital, its existence, is important in assessing how the state is perceived by the public. It is therefore necessary to explain what social capital is. The first concept of social capital was presented by Hanifan (Citation1916), which defined it as ‘those tangible assets [that] count for most in the daily lives of people: namely goodwill, fellowship, sympathy, and social intercourse among the individuals and families who make up a social unit’.

In literature there is much more to the definition of social capital, which is to some extent the result of the existence of a lot of empirical evidence about the role of networks and norms of mutual support in contributing to higher-quality community governance as well as economic, social and personal development (Healy, Citation2002, pp. 2–3). The best known are those presented by Bourdieu, Coleman, Fukuyama and Putnam.

According to Bourdieu (Citation1985, p. 248) social capital is “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition’. He believes that social networks could be used to exclude non-members and to prevent social mobility (Scrivens & Smith, Citation2013, p. 13). Bourdieu believes that social capital along with other forms of associated capitals (economic and cultural) explains the structure and dynamics of differentiated societies (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 119). Social capital does not have to be useful at all, but can be also exclusionary.

Coleman's social capital is different. According to him, social capital is one of the potential resources. Social capital ‘is not seen only as stock held by powerful elites, but notes its value for all kinds of communities, including the powerless and marginalized’ (Gauntlett, Citation2011). Coleman (Citation1988, p. 98) considers that ‘social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity, but a variety of different entities, having two characteristics in common: they all consist of some aspect of a social structure, and they facilitate certain actions of individuals who are within the structure’. Coleman (Citation1990) highlights that social capital is a public good that depends on the willingness of the members of the community to avoid free riding. For this purpose, norms, trust, sanctions and values become important in sustaining this collective asset (Andriani, Citation2013, p. 4).

Fukuyama defined social capital as ‘a set of informal values and ethical norms (e.g., charity) common to members of a particular group that enable them to cooperate effectively’ ( Fukuyama, Citation1997, In: Klimczuk, Citation2012, p. 70 ). He believes that social capital allows relationships between people to be created, to set up groups, associations and institutions of civil society. Social capital is created and transmitted through cultural mechanisms: religion, tradition, historical habit (Fukuyama, Citation1997, p. 39). According to Fukuyama the level of trust inherent in a given society determines its prosperity and degree of democracy, as well as its ability to compete economically (Passey, Citation2000, p. 8).

Another well-known definition of social capital is Putnam’s conception. According to him social capital is the networks of civic engagement, trust and norms of reciprocity, which can increase the efficiency of society (Putnam, Citation1995, p. 258). According to Putnam social capital is a public good and „life is easier in a community blessed with a substantial stock of social capital. In the first place, networks of civic engagement foster sturdy norms of generalised reciprocity and encourage the emergence of social trust. Such networks facilitate coordination and communication, amplify reputations’ (Putnam, Citation1995, p. 2). It should be remembered that dependencies also exist in the other direction. As noted by Carpenter, Daniere and Takahashi (Citation2004), people with higher levels of social capital are more confident. The strength of Putnam’s approach lies in the way in which it seeks to combine different aspects of the ‘social capital’ concept (Newton, Citation1999, p. 3).

Having discussed in detail successive definitions as well as the ways social capital has been formulated one can easily notice its’ diversity: to begin with macro approach (Putnam, Fukuyama), throughout mezzo (Coleman) right up to micro approach (Bourdieu). Vast differences are also perceptible in defining of social capital components although all of them derive from one source which is social relations. Aforementioned Coleman has paid attention not only to social norms but also to credibility of social structures and efficiency of communication channels. What is more, he has been concentrating on individual exploitation of social capital at the same time pointing up at the fact that social capital particularly increases combined operation of relatively small groups. On the other hand, Bourdieu has been concentrating on more or less institutionalised relations based on trust as a fundamental attribute of social capital. He has described individual’s social capital as her/his resource whereas group’s social capital as a total amount of it’s members resources. According to Bourdieu, social capital is crucial both in emerging social classes and igniting social conflicts. Moreover, it is not always used by individuals in accordance with collective interests or interests of other individuals. By contrast, Putnam draws attention to three components of social capital: moral obligations and norms, social values (especially trust) and social networks (especially voluntary associations). According to Putnam social capital is a public resource. Bottom-up indicators of social activities are the evidence of high level of social capital that reinforces not only social values but also human solidarity. Fukuyama representing the same approach as Putnam underlines the significance of informal values, norms, but first and foremost trust as the key attribute of social capital. According to him, one of the most important benefits of high social capital is the reduction of transaction costs in the economy as well as the higher level of commitment in civic groups that fill up a gap between a state and a family.

The authors of the article treat social capital as a resource that is a value for all kinds of community and serves a common purpose. On the other hand, trust, including trust in public institutions (among others, on which the authors focus), strengthens cooperation, and cooperation strengthens further trust in the positive spiral of cooperation and engagement (Rymsza, Citation2007, p. 31). In addition, relationships formed in groups such as acquaintances, colleagues, neighbours are necessary for ‘making progress’ in the community (Nagaj & Žuromskaitė, Citation2016).

Taking into account the objective of the paper and adopting the definition of the state by G. Jellinek (Kostrubiec, Citation2002, pp. 375–382) as a system of three components: the society (citizens), the territory and the authority, in the empirical analysis undertaken in this paper various dimensions of social capital are used referring to the state as a society (citizens) and the state as the authority. Analysing the perception of the state as the society, the attention of the authors is focused on the evaluation of democracy by the surveyed young people, the importance of their voice in society and social participation. On the other hand, in the dimension of the state as the authority, the analysis is subjected to: trust in the authorities, honesty of the employees of central and local administration, the state attitudes aimed at helping others and evaluation of the general activity of public institutions.

There is a large literature on democracy, its definitions, components and methods of measurement ( Mayo Citation1960, Cunningham Citation2002, Saradamov Citation2005, Goodhart Citation2005, Held Citation2006, Bühlmann, Wolfgang, & Bernhard, Citation2008, Kekic, Citation2007, Schmidt, Citation2006 ). President of the USA Abraham Lincoln on November 19, 1863) stated that democracy is ‘the government of the people, by people and for people’ (Sodaro, Citation2004, p. 168). Sodaro (Citation2004, p. 31) emphasises that ‘The basic idea of democracy is that people have the right to decide who governs them, and at the same time it guarantees the rights and freedom of citizens’. In turn, Bühlmann points out three principles of democracy: freedom, equality and control’ (Bühlmann et al., Citation2008, p. 15). Democracy is inseparably connected with social activity understood as the activity of an individual determined by the role that it plays in society (Mularska-Kucharek & Świątek, p. 69; Tyszkowska, Citation1990, p. 188). Social activity is analyzed in three dimensions. The first of these is informal social interactions with people who are known: with family, friends, neighbours, for example during meetings. The second is formal activity, manifested through participation in groups or formal organisations, for example in associations. The third is individual activity for the benefit of society, for example by helping others (Adams, Leibbrandt, & Moon, Citation2011, p. 684).

Social activity is very often associated with social participation in the political area in the process of creating a civil society. Social participation is a complicity or inclusion of various people and organisations in activities for the benefit of the community. A citizen is not a passive individual who is waiting for change. In such a situation, he/she takes part in these changes and shapes them (Antoszewski, Citation2000, p. 9).

Democracy allows citizens, including young people, to co-decide on the issues that concern them and not just be passive recipients of what is happening to the state and their social activity. Undoubtedly, when unless citizens participate in the deliberation of public policy, and their choices of government structure, then democratic processes are meaningless (Dalton, Citation2008, p. 78). So, it's very important that citizens must be aware of the importance of their vote in the public debate. People who are socially engaged are willing to sacrifice time for the common good, and that this affects their tendency to civic behaviour. As emphasised by Stolle (Citation2007), empirical research results (Howard, Citation2003; Inglehart, Citation1997) show that social engagement is significantly lower in countries that have experienced periods of non-democratic governments like in Poland and Lithuania.

The attitude of young people to democracy is dependent on trust in the state. As Putnam pointed out, active citizens are necessary for the existence of civil society, as well as political and social relations based, on the basis of equality and cooperation, on trust. (Putnam, Citation1995, pp. 31–32). Coleman (Citation1990) and Hardin (2002) believe that trust can be understood as a ‘rationalised calculation’ (Growiec, Citation2009, p. 55). In turn, Sztompka notes that trust is ‘the most precious type of social capital’ (Sztompka, Citation2007, p. 71). Trust offers a feeling of predictability of partners’ behaviours. When creating the social capital through trust as its key component we can raise the efficiency of the society as trust strengthens the existing bonds and encourages development of new ones.

The principle of trusting citizens as organs of the state is considered to be a brace that breaks the whole of the general rules of conduct (Skrenty, Citation2013, p. 98). Increasing citizens' trust in the state (public trust), which eliminates the uncertainty of joint action undoubtedly results from the conviction of individuals about the state's compliance with social norms, such as honesty. Political trust is positively correlated with institutionalised participation, but at the same time it has a negative impact on noninstitutionalised participation (Hooghe & Marien, 2012). It is worth emphasising that if citizens cannot trust the institutional effectiveness and fairness of the judicial system and the police because of corruption, then their view of others is compromised; conversely, fair and impartial practices facilitate trust and social interactions (Stolle, Citation2007).

Social capital as networks, norm and trust is associated with a number of political outcomes, especially well-performing democratic institutions (Newton, Citation1999; Park & Shin, Citation2003; Putnam, Citation1993; Woolcook, Citation2001) and democratic stability (Inglehart, Citation1999). According to Putnam (Citation1993) when society is rich in social capital then society is engaged in democracy, dense networks of civic engagement produce a capacity for trust, reciprocity and co-operation (‘social capital’), which in turn produces a healthy democracy. Lowndes and Wilson (Citation2001) argue that Robert Putnam’s social capital thesis is too society-centred and undervalues state agency and associated political factors. Governments can shape the development of social capital and its potential influence upon democratic performance. A lot of problems facing contemporary democracies (low voter turnout, distrust of politicians, low membership of political parties) may be ameliorated if the stock of social capital can be increased by state action (Meadowcroft & Pennington, Citation2007, p. 65). Newton has similar doubts. He challenges Putnam’s ‘bottom-up’ bias, arguing that social capital ‘may also be strongly affected by the policy of governments and by the structure of government itself – a top-down process’ (Newton Citation1999, p. 17). Government should support civil society, fund voluntary organisations, make social capital wherever it is lacking (Dowley & Silver, Citation2002). Equally important for the building of social capital is also the creation of social solidarity by the state institutions, for example by helping others (Szkudlarek, Citation2017). Feeling solidarity with other people pulls the individual from the circle of privacy and allows oneself to cross selfishness (Kochman, Citation2009, p. 1). Brehn and Rahn add that 'social capital may be as much a consequence of confidence in institutions as the reverse’ (Brehn & Rahn, Citation1997, p. 1018). Decline of social capital is likely to cause a loss of trust in political leadership and a loss of confidence in the institutions of government (see for example, Norris, Citation1999; Nye, Zelikow, & King, Citation1997; Pharr et al., Citation2000).

The factor that can also impact on the trust level, including political trust, is the generational replacement. Generational replacement is generally considered to be a key process driving social and political change with respect to attitudes toward political institutions (Hooghe, Citation2004, p. 331). The decline in trust is especially visible among young people. These differences are with regard to political behaviour, such as participation, civil engagement, attitudes or norms and values. Young people are less likely to cast a vote during elections (Blais, Gidengil, Nevitte, & Nadeau, Citation2004; Franklin, Lyons, & Marsh, Citation2004; Plutzer, Citation2002), tend to eschew traditional party politics (Dalton, Citation2002, p. 31) and they are more distrusting toward political institutions (Hooghe, Citation2004, p. 332). However among students at least it is true, they are more or equally active in other forms of participation and group involvement and they are frustrated mainly with political institutions (Stolle et al., Citation2005, p. 263).

3. Methodology

The result of the research was based on the survey tool, statistical methods of time changes and statistical verification of the results using U Mann-Whitney test and difference between two population proportions test. The basis for the conclusions about the perception of the state by the students was the data from the survey research on social capital. The survey was conducted by employees of the Department of Macroeconomics at the Faculty of Economics and Management University of Szczecin within statutory research funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.1 Statistical research aiming to assess the attitude of young people to the state was conducted using a questionnaire survey was carried out among students of the first and third year of the bachelor’s degree studies at the Faculty of Economics and Management University of Szczecin (1st year: n = 267, 3rd year: n = 229) and at the Faculty of Politics and Management Mykolo Romeris University in Vilnius (1st year: n = 113, 3rd year: 73). Of the total number of students enrolled at the indicated universities, the proportions of the surveyed students were as follows: 58.0% and 49.8% (Poland), and 51.4% and 63.5% (Lithuania). The aim of the research imposed employment of purposive sampling: students of first and third year of first degree of study (the bachelor’s degree of study). The aim of the research was also to conduct a survey questionnaire on social capital. The survey was based on a paper questionnaire consisting of two parts: demographics and a set of questions concerning social capital. The questions about social capital were developed according to a logical model proposed by the World Bank (Grootaert, Narayan, Jones, & Woolcock, Citation2004). This part of the questionnaire consisted of 36 closed- and open-ended questions regarding social capital (Milczarek, Miłaszewicz, Nagaj, Szkudlarek, & Zakrzewska, Citation2015, p. 95). For the purpose of the analysis, the authors selected eight questions concerning the young people's attitude toward to the state, state institutions at central and local government level and their activities and to democracy. This perception of young people was examined by assessing the activity of state institutions, trust in those institutions, the honesty of the employees of these institutions, the perception of democracy as a form of governance, and the state’s support of the respondents’ activity in the participation in social activities and elections. Statistical methods of time changes are used in statistical analysis.

Comparing the data of students of first year of study and of third year of study will also allow to examine whether the acquired knowledge and social competencies during the 3 years of study determine the perception of the state by students.

Due to the lack of measurable data on the level of education for the first and third year of study, the assumption was made that the level of knowledge of students of the third year of study is higher than among students of the first year. It results from the necessity to implement the effects of education and is the essence of the education process.

To make a statistical verification of the hypothesis resulting from this research the U Mann-Whitney test and the difference between two population proportions test were used.

For each question in the given country is:

null hypothesis H0: there is no statistically significant difference between students of first and of third year of study regarding social capital,

alternative hypothesis H1: there is statistically significant difference between students of first and of third year of study regarding social capital,

All of foregoing tests allowed only to determine whether there exist significant differences in perception of the state by first and third year students in the context of research on social capital. However, one cannot see them as an opportunity to identify the causes of contingent disparities. It is necessary to underline, that taking into account accessible data it was impossible to use the chi-square independence test used to verify the hypothesis on the importance of connection between two variables (in case of this paper between the level of education – knowledge of first and third year students and their perception of the state).

The results of the study does not indicate a change in perception among the same individuals, but differences in perception among groups of students with varying levels of academic knowledge. However it should be noted that both studied groups of students (1st and 3rd year) are relatively similar in terms of the characteristics of the respondents ().

Table 1. Description of the research sample.

4. Research results

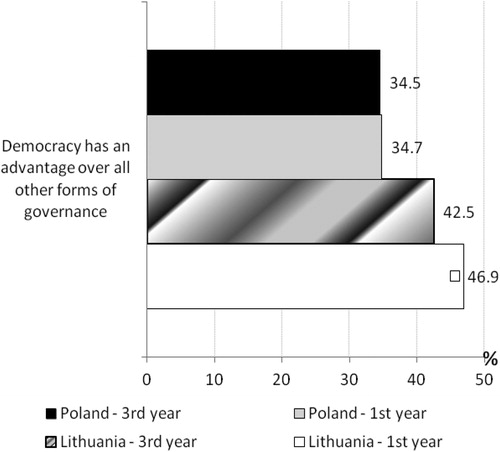

The first key element of the state is civic engagement in society, which is measured by the attitude of people to democracy. The significance of democracy stems from the fact that it allows the citizens to co-decide on the state and its activities, including social activities. shows the changing perception of democracy as a form of a political system by the surveyed students.

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents who agreed with statement that the democracy is good or a very good form of political system (answers “rather yes” and ‘definitely yes’).

The research results in Lithuania show that young people are more likely to accept democracy as a form of government, regardless of the year of study. However, it is worth pointing out some differences in the understanding of democracy between young people. In the first year of study, most of the students think that democracy rather has or surely has an advantage over other forms of governance (46.9% of the respondents confirm this, while 8.8% have a different opinion, and 19.2% are undecided). On the other hand, students in the third year of studies in most cases have difficulties in addressing this issue (44.2% of the respondents are undecided). It should be stressed, however, that a small percentage of students, regardless of their year of study, disagree with the statement that democracy has no advantage over other forms of governance. In turn, students in Poland, regardless of their year of study, in most cases have difficulties in assessing democracy (48.9% first year students and 48.0% third year students). However, it should be pointed out, that there is a far greater proportion of those young people who believe that democracy has an advantage over other forms of governance than those who claim that such advantage does not exist. On the first year 34.7% agrees with this statement and 16.4% of the students have a different opinion. In the third year, those percentages are 34.5% and 17.5%, respectively.

The analysis of the data using U Mann-Whitney test shows that in both examined countries there is no statistical difference in the answers provided between students on the first and the third year. In Poland p = 0.770197 (Z = 0.292117), while in Lithuania p = 0.384187 (Z = 0.870209).

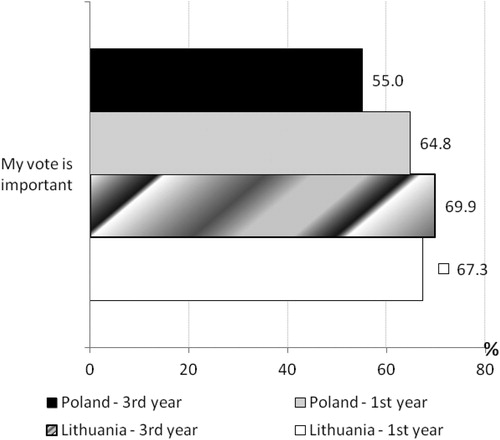

The indecisiveness of the students in the assessment of democracy as a form of governance was not reflected in the students' assessment of the importance of their voice in society (). In Lithuania, most of the surveyed students, regardless of their year of study, think that their voice is rather, or definitely, important in the communities in which they live (67.3% the first year and 69.9% the third-year students). Only about a quarter of students on the first and third year of studies do not have an opinion on this issue. In the case of Polish students, also the majority is aware of the importance of their voice in society (the first-year students 64.8% and the third-year students 55.0%).2 However, it is worth noting that the share of students who express such opinion is by almost 10 percentage points lower among students of the third year than the first-year study.

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents who agreed with statement that their vote is important (answers: ‘rather yes’ and ‘definitely yes’).

The analysis of the data using U Mann-Whitney test showed that in Poland, there is a statistically significant difference between students from the first-year study and the third-year study in the answers given, p = 0.038875 (Z = 2.065520). However, there is no statistically significant difference in the answers given between the first and third-year students in Lithuania, p = 0.975524 (Z = 0.030680).

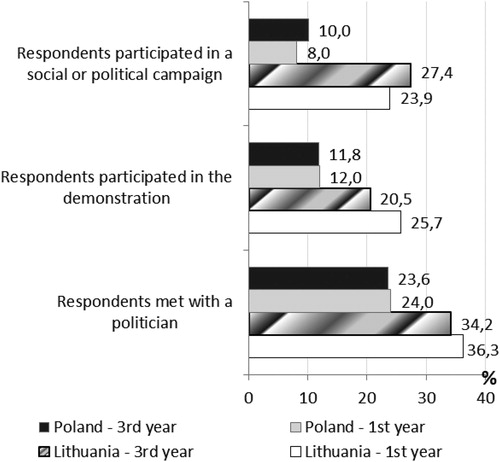

By doing the research it was also possible to determine the social activity of young people, considered in the context of social participation in the political sphere and the creating of civil society ().

Figure 3. Percentage of respondents participating in certain social activities during the year (answer ‘yes’).

Research results show that most of the Lithuanian students of the first year of studies show social activity in terms of meetings with politicians (36.3% of respondents) or of participation in demonstrations (25.7% of the respondents). Such a scale of social participation is no longer valid for students in the third year of study (34.2% and 20.5%, respectively). In turn, students in Poland, regardless of their year of study, do not show any of the forms of social activity indicated in the questionnaire survey: meetings with politicians, participation in demonstrations or participation in political and social campaigns. The share of active students of the first year of study varies between 8.0% and 24.0%, and for students in the third year between 10.0% and 23.6%.

Data analysis using the difference between two population proportions test showed that between students of the first and third year in Poland and between students of the first and third year in Lithuania, there is no statistically significant difference in the answers given for social participation ().

Table 2. Social participation of surveyed students – results of difference between two population proportions test.

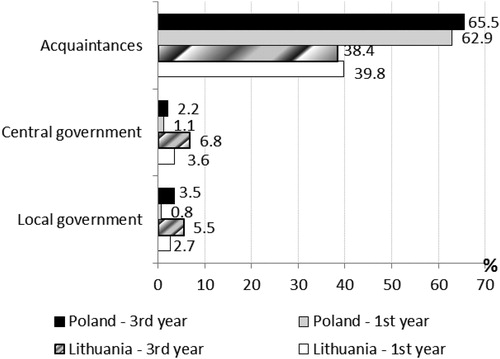

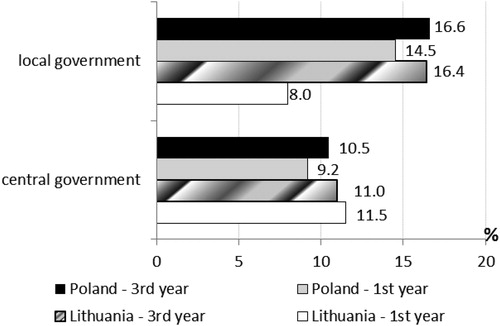

Literature indicates that the attitude of society towards democracy depends on the trust in the state. For this reason, afterwards, the authors investigated how does the young people's trust in public institutions change. The data from the analysis in this area are presented in the .

Figure 4. Students' trust to the public authorities and acquaintances (answers: ‘I trust strong’ and ‘I trust very strong’).

Generally, it has been stated that young people in both countries do not trust public institutions. This is particularly visible comparing to the level of trust to friends. In Lithuania, regardless of the year of study, the level of strong or very strong trust in the central government or the local government does not exceed 6.8%. However, it should be pointed out that fewer students in the third year than in the first year express their lack of trust in the authority, regardless of its level. In Lithuania, however, it can be presumed that this is a result of a generally low level of trust, since less than 40% of the respondents trust their friends. In Poland the level of trust in public institutions among students is even lower. To compare, as many as 2/3 of students trust their friends.

The analysis of the data using U Mann-Whitney test showed that in the case of Polish students, there are statistically significant differences in trust in the local authority between students on the first and third year of study, p = 0.006801 (Z= −2.70647). There is no such difference of trust in relation to the central authority, p = 0.283154 (Z= −1.073262). In the case of students in Lithuania, there was no significant difference in the answers given. The result of the U Mann-Whitney test relating to trust in local authority is p = 0.330352, (Z= −0.973407), and for the central authority is p = 0.875002 (Z= −0.157308).

For individuals in civil society, it is important to be convinced about the compatibility of state actions with social norms, as it deepens trust, builds social capital and encourages joint action. Therefore, the authors examined the change in student's perception of the honesty of local and central government employees and in their creation of an attitude aimed at helping others ().

Figure 5. Students’ assessment of the honesty of employees of public institutions at local and central level (answers: ‘rather honest’ and ‘very honest’).

Research results show that in Lithuania, for first and third-year students, it is often difficult to assess the honesty of employees of central and local government institutions (about a half of the respondents has no opinion on this subject). However, it should be added that a very large proportion of students, regardless of their year of study, indicate that they are rather dishonest or very dishonest. The same situation occurs among young people in Poland. Similarly to their peers in Lithuania, they also, regardless of their year of studies, have difficulties in assessing the honesty of central and local government institutions employees (more than a half of the respondents). It is notable that there is a high proportion of those young people who negatively evaluate the honesty of employees of public institutions. It should be noted, however, that in Poland both the first and the third-year students have better opinion about the honesty of local government employees rather than the central ones, while in Lithuania such situation occurs only among students of the third year. An addition to the above analysis could be the data on barriers to helping others. In Poland, regardless of the year of study, nearly the half of students (41.2% of the respondents of the first-year students and 40.6% of the third-year students) are convinced that it is the corruption in public institutions. The same situation occurs among young people in Lithuania, where the proportions are 36.3% and 42.5%, respectively.3

The analysis of the data regarding the honesty of public institutions employees using the U Mann-Whitney test showed that in both countries, there was no statistically significant difference between the responses of first and third-year students. In Poland, in relation to the honesty of the central authority, the test result is p = 0.153237 (Z = 1.428196), and of the local authority it is p = 0.545688 (Z= −0.604234). In turn, in Lithuania, the test result regarding the central authority is p = 0.539474 (Z= −0.613609), and for the local authority p = 0.203429 (Z= −1.271844).

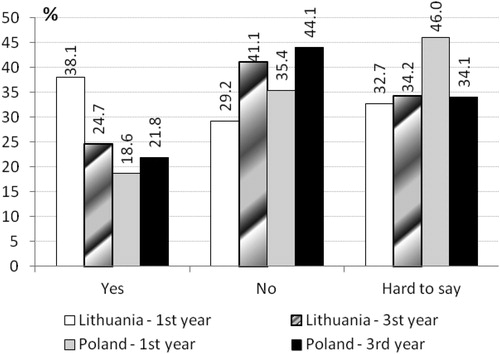

In the context of civil society and the building of social capital, it is important for state institutions to create social solidarity, for example by helping others. For this reason, the authors examined the change in the young people’s opinion about the participation of the public institutions in the creation of attitudes aimed at helping others ().

Figure 6. The opinion of the respondents, in their opinion, that state institutions by their actions create attitudes aimed at helping others.

It should be stated that the respondents are not so unanimous in the assessment of state institutions' attempts to help others as a norm of social capital. In Lithuania there are some differences between the first and third-year students (although the percentage of the answers is similar) in evaluating the state's actions aimed at helping others. Students of the first year of study in most cases (38.1%) confirm that state institutions, by their actions, create attitudes aimed at helping others. Students of the third year have most often (41.1%) a contrary opinion. Regardless of the year of study, about one-third of the students say that it is difficult to get a clear view of the matter. In Poland there are more differences in the opinions about the actions of public institutions aimed at creating attitudes directed at helping others between the first and third-year students. Young people in Poland, even more than students in Lithuania, have problems when dealing with this issue (46.0% of first-year students and 34.1% of third-year students). It is worth emphasising, however, that the respondents in Poland, more than those from Lithuania, consider that public institutions do not create attitudes aimed at helping others. In addition, this percentage increases by 8.7 percentage points between the first and third year of study.

The analysis using the difference between two population proportions test showed that in Lithuania there is a statistically significant difference between the students of first and third year of study, p = 0.028704 (u = 1.900195). Such a difference was not found among the students in Poland p = 0,188374 (u = 0.883904).

5. Conclusions

The results of the research indicate that the knowledge and the social competencies acquired during the three years of study in most cases were not reflected in the change of perception of the state by Polish and Lithuanian young people in the context of key dimensions of social capital. Therefore, it cannot be confirmed that there is a positive relationship between education and social capital ( Huang, van den Brink, and Groot, Citation2009; Leeves, Citation2014; Anderson, Citation2008 ) in terms of relationship citizen-state. Statistically significant changes did not occur in the perception of democracy by surveyed young people in Poland and Lithuania as a form of exercising power, social participation of students in the politics and creation of civil society, students' perception of the honesty of the employees of public institutions and state institutions’ activities aimed at creating attitude directed at helping others. The lack of statistically significant changes in the perception of their opinion’s significance in the society and trust towards the central and local government was noted only among Lithuanian young people. In the case of Polish young people, there were no statistically significant changes in trust towards the central government, although statistically significant differences occurred in their trust towards local government. In addition, among the young people from Poland, there occurred statistically significant differences in the perception of their opinion’s significance in society and the perception of the governmental institutions’ actions aimed at creating attitude directed at helping others.

It should be emphasised that the lack of statistically significant changes in the perception of the state by young people in Poland and in Lithuania also means that their general assessment of the state is low. Unfortunately, students do not usually consider public authorities trustworthy entitles who follow social norms such as honesty or who manage to create activities directed at helping others. This was reflected in the overall low assessment of the activity of governmental institutions and their low participation in the process of creation of a civil society. However, it should be noted that young people in Poland and Lithuania do not express their negative views on democracy as a system of governance and admit the significance of their opinion in society. The research results are in this area consistent with the results of research presented in the literature on the attitude of young people to public institutions and democracy in Western Democracies (Hooghe, Citation2004; Inglehart, Citation2003; Norris, Citation1999) and different from those for countries from Central Europe presented by Newton (Citation2001).

The results of the research presented in this article correspond to the results presented by the research institutions in Poland or Lithuania concerning the perception of the state by the general public. They point out i.e., the low civil activity of Polish and their general distrust in the government. A lack of trust in government is also observed in Lithuania. It can, therefore, be assumed that such a picture of the state in the eyes of the young people surveyed in Poland and Lithuania is a manifestation of the general crisis of confidence, values and norms which are supposed to contribute to the public good. These are the important barriers to building social capital in the citizen-state dimension, which can limit the social participation of young people. At the same time, it can be assumed that their networks of relationships with others, trust and acting in accordance with norms are rather bottom-up building of social capital.

Thus, the improvement of the perception of the state by the young generation of Poland and Lithuania should be a challenge for the authorities in both countries. It is proposed that public authorities increase knowledge among young people about the need for the existence of the state and ensure greater transparency of the activities of public institutions. It is postulated to provide young people a direct impact on the functioning of the state and involve them in public activities. It is also necessary to discuss problems concerning young people in the public debate and to use such communication tools that young people use. Undoubtedly, there is a need for an active role of educational institutions, including academic institutions, in increasing the participation of young people in public life/activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The research among students of 1st year of study was conducted in 2014 (at the beginning of the year in Poland and at the end of the year in Lithuania) within statutory research entitled Knowledge and social capital. Part I. Bridging type of social capital (research no. 503-2000-230-342). At the end of 2016 the research was conducted among students of 3rd year of study in Poland within statutory research entitled: Knowledge and social capital, part III. Analysis of survey results of students’ social capital (research no. 503-2000-230-499); and at the beginning of 2017 the research was conducted among students of 3rd year of study in Lithuania within statutory research entitled: Knowledge and social capital, part IV. International survey of students’ social capital (research no. 503-2000-230-499).

2 Data based on survey results.

3 Data based on survey results.

References

- Acar, E. (2011). Effects of social capital on academic success: A narrative synthesis. Educational Research and Reviews, 6(6), 456–461.

- Adams, K. B., Leibbrandt, S., & Moon, H. (2011). A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing and Society, 31(4), 683–712. doi:10.1017/S0144686X10001091

- Anderson, J. B. (2008). Social capital and student learning: Empirical results from Latin American primary schools. Economics of Education Review, 27(4), 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.05.002

- Andriani, L. (2013). Social Capital: A Road Map of Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical Limitations. Working Papers in Management, Birkbeck, University of London, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, pp. 1–26. Retrieved from http://www.bbk.ac.uk/management/docs/workingpapers/WP1.pdf

- Antoszewski, A. (2000). Społeczeństwo obywatelskie a proces konsolidacji demokracji [Civil society and the democracy consolidation process]. In A. Czajkowski, & L. Sobkowiak (Eds.), Studia z teorii polityki (vol. 3, pp. 7–21). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiegot.

- Armingeon, K., & Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis: The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. European Journal of Political Research, 53(3), 423–442. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12046

- Balatti, J., & Falk, I. (2002). Socioeconomic contributions of adult learning to community: A social capital perspective. Adult Education Quarterly, 52(4), 281–298. doi:10.1177/074171302400448618

- Blais, A., Gidengil, E., Nevitte, N., & Nadeau, R. (2004). Where does turnout decline come from. European Journal of Political Research, 43(2), 221–236. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00152.x

- Bourdieu, P. (1985). The forms of capital. In J.G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved May 21, 2018, from: http://www.academia.edu/5543729/Bourdieu_and_Wacquant_An_Invitation_to_Reflexive_Sociology_1992

- Brehn, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41 (3), 999–1023. doi:10.2307/2111684

- Bühlmann, M., Wolfgang, M., & Bernhard, W. (2008). The Quality of Democracy. Democracy Barometer for Established Democracies. National Center of Competence in Research: Challenges to Democracy in the 21s t Century. Working Paper No. 10a. Retrieved October 15, 2018, from http://www.nccr-democracy.uzh.ch/nccr/publications/workingpaper/10.

- Carpenter, J., Daniere, A., & Takahashi, L. (2004). Social capital and trust in South-East Asian cities. Urban Studies, 41(4), 853–874. doi:10.1080/0042098042000194142

- CBOS. (2014). Stosunek do instytucji państwa oraz partii politycznych po 25 latach [Relations with state institutions and political parties after 25 years]. Komunikat z badań, 68, 1–9. Retrieved from: http://okragly-stol.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/CBOS_Stosunek_do_panstwa.pdf [25.11.2017].

- CBOS. (2016). Zaufanie społeczne [Social trust]. Komunikat z badań, 18, 1–20. Retrieved from: http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2016/K_018_16.PDF [21.05.2018].

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harward University Press.

- Cunningham, F. (2002). Theories of democracy: A critical introduction. New York: Routledge.

- Czapiński, J. (2015). Stan społeczeństwa obywatelskiego. Diagnoza Społeczna 2015, Warunki i Jakość Życia Polaków – Raport [Social Diagnosis 2015, objective and subjective quality of life In Poland]. Contemporary Economics, 9(4), 332–372. doi:10.5709/ce.1897-9254.191

- Dalton, R. (2002). The decline of party identifications. In R. Dalton, & M. Wattenberg (Eds.), Parties without partisans (pp. 19–36). Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

- Dowley, K. M., & Silver, B. D. (2002). Social capital, ethnicity and support for democracy in post-communist states. Europe Asia Studies, 54(4), 505–527. doi:10.1080/09668130220139145

- Eurofound. (2016). European Quality of Life Survey 2016 [Data set]. Retrieved August 2, 2018, from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/european-quality-of-life-survey

- Franklin, M., Lyons, P., & Marsh, M. (2004). Generational basis of turnout decline in established democracies. Acta Politica, 39(2), 115–151. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500060

- Fukuyama, F. (1997). Zaufanie. Kapitał społeczny a droga do dobrobytu [Trust. Social capital and the path to prosperity]. Warszawa-Wrocław: PWN.

- Fukuyama, F. (2001). Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Quarterly, 22(1), 7–20. ), doi:10.1080/713701144

- Gauntlett, D. (2011). Making is Connecting, The social meaning of creativity, from DIY and knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Cambridge: Polity Press. Retrieved June 30, 2015, from http://www.makingisconnecting.org/gauntlett2011-extract-sc.pdf

- Glaeser, E. L. (2001). The Formation of Social Capital, pp. 1–57. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/innovation/research/1824983.pdf

- Goodhart, M. (2005). Civil society and the problem of global democracy. Democratization, 12(1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/1351034052000331072

- Grootaert, C., Narayan, D., Jones, V. N., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Measuring social capital: An integrated questionnaire. World Bank Working Paper, 18. Washington DC: The World Bank. Retrieved August 20, 2013, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/15033/281100PAPER0Measuring0social0capital.pdf?sequence=1

- Growiec, K. (2009). Związek między sieciami społecznymi a zaufaniem - mechanizm wzajemnego wzmacniania? [The relationship between social networks and trust - the mechanism of mutual reinforcement?]. Psychologia Społeczna, Tom 4, 1–2 (10), 55–60.

- Hanifan, L. J. (1916). The rural school community center. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 67(1), 130–138. doi:10.1177/000271621606700118

- Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hawkins, R. L., & Maurer, K. (2010). Bonding, bridging and linking: How social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. British Journal of Social Work, 40(6), 1777–1793. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp087

- Healy, T. (2002). The measurement of social capital at international level. National Economic and Social Forum, National Statistics, OECD. Ireland, (pp. 2–3). Retrieved May 21, 2018, from http://www.oecd.org/innovation/research/2380281.pdf

- Held, D. (2006). Models of democracy (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Ho, S. C. (2003). Home school collaboration and creation of social capital. Hong Kong Journal of Sociology, 4(1), 57–85.

- Hooghe, M. (2004). Political socialization and the future of politics. Acta Politica, 39(4), 331–341. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500082

- Hooghe, M., & Marien, S. (2013). A comparative analysis of the relation between political trust and forms of political participation in Europe. European Societes, 15(1), 131–152. doi:10.1080/14616696.2012.692807

- Howard, M. (2003). The weakness of civil society in post-communist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Huang, J., van den Brink, H. M., & Groot, W. (2009). A meta-analysis of the effect of education on social capital. Economics of Education Review, 28(4), 454–464. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.03.004

- Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. (1999). Trust, well-being and democracy. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy & trust. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, R. (Ed.) (2003). Human values and social change. Findings from the values survey. Leiden: Brill.

- Israel, G. D., Beaulieu, L. J., & Hartless, G. (2001). The influence of family and community social capital on educational achievements. Rural Sociology, 66(1), 43–68. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2001.tb00054.x

- Kekic, L. (2007). The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy. The Economist, London. Retrieved October 10, 2018, from http://www.economist.com/media/pdf/DEMOCRACY_INDEX_2007_v3.pdf.

- Klimczuk, A. (2012). Kapitał społeczny ludzi starych [Social capital of old people]. Lublin: Wiedza i Edukacja.

- Kochman, I. (2009). Solidarność społeczna [Social solidarity]. Wokół Debat Tischnerowskich, pp. 1–7. Retrieved from: http://erazm.uw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Solidarnosc-spoleczna.pdf [26.06.2017].

- Kostrubiec, J. (2002). Próba współczesnej interpretacji klasycznej definicji państwa Georga Jellinka [An attempt at contemporary interpretation of the classical definition of Georg Jellink's state]. In M. Maciejewski, & M. Marszał, (Eds.), Doktryny polityczne i prawne u progu XXI wieku (pp. 375–382). Wrocław: Kolonia Limited.

- Leeves, G. D. (2014). Increasing returns to education and the impact on social capital. Education Economics, 22(5), 449–470. Retrieved from [18.05.2018]. doi:10.1080/09645292.2012.660133

- Lowndes, V., & Wilson, D. (2001). Social capital and local governance: Exploring the institutional design variable. Political Studies, 49(4), 629–647. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00334

- Maloney, W.A. & Van Deth (Eds.), (2010). Civil society and activism in Europe. Contextualizing engagement and political orientations. London: Routledge.

- Mayo, H. (1960). An introduction to democratic theory. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1086/ahr/66.1.132

- Meadowcroft, J., & Pennington, M. (2007). Rescuing social capital from social democracy. London: The Institute of Economic Affairs.

- Milczarek, A., Miłaszewicz, D., Nagaj, R., Szkudlarek, P., & Zakrzewska, M. (2015). Social networks as a determinant of the socialisation of human capital. Human Resources Management & Ergonomics, 2, 89–103.

- Mularska-Kucharek, M., & Świątek, A. (2011). Aktywność społeczna mieszkańców Łodzi. Analiza Wybranych Wymiarów [Social Activity of the Inhabitants of Łódź. Analysis of Selected Dimensions]. Studia Regionalne i Lokalne, 4(46), 68–83.

- Nagaj, R., & Žuromskaitė, B. (2016). Incomes and the willingness of students in Poland and Lithuania to participate in charitable activities. Journal of International Studies, 9(2), 127–138. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2016/9-2/9

- Newton, K. (1999). Social capital and democracy in modern Europe. In J. W. Van Deth, M. Marafii, K. Newton., & P. F. Whiteley (Eds.), Social capital and European democracy (pp. 3–22). London: Routledge.

- Newton, K. (2001). Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Science Review, 22(2), 201–214. doi:10.1177/0192512101222004

- Nikolayenko, O. (2005). Social capital in post-communist societies: Running deficits?=Retrieved August 3, 2018, from: https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2005/Nikolayenko.pdf

- Norris, P. (Eds.), (1999). Political citizens, global support for democratic governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, P. (2001). Making Democracies Work: Social Capital and Civic Engagement in 47 Societies. John F. Cambridge: Kennedy School of Government Working Paper Series. Retrieved from: https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Acrobat/ESFSocialCapital.pdf

- Nye, J., Zelikow, P. D. & King D. C. (Eds.). (1997). Why people don’t trust government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- OECD. (2001). The Well-being of Nations. The role of human and social capital (pp. 1–120). OECD: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from http://www.oecd.org/site/worldforum/33703702.pdf.

- Park, C. M., & Shin, D. C. (2003). Social Capital and Democratic Citizenship: The Case of South Korea. Working Paper Series, 12, Taipei: Asian Barometer. Retrieved August 4, 2018, from http://www.asianbarometer.org/publications/53f02109fd2504fb3a279dbd19d394c6.pdf.

- Passey, A. (2000). Social capital: Embeddedness and autonomy. Conference Paper presented at ISTR, Dublin.

- Pharr, S. J., Putnam, R. D., & Dalton, R. J. (2000). Introduction: What’s troubling the trilateral democracies? In S. J. Pharr, & R. D. Putnam (Eds.). What's ailing the trilateral democracies? (pp. 3–27). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pishghadam, R., & Zabihi, R. (2011). Parental education and social and cultural capital in academic achievements. International Journal of English Linguistics, 1(2), 50–57.

- Plutzer, E. (2002). Becoming a habitual voter, Inertia, resources, and growth in young adulthood. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 41–56. doi:10.1017/S0003055402004227

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling Alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. doi:10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Demokracja w działaniu [Democracy in action]. Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak.

- Rymsza, A. (2007). Klasyczne koncepcje kapitału społecznego [Classic concepts of social capital]. In T. Kaźmierczak, & M. Rymsza (Eds.), Kapitał społeczny: Ekonomia społeczna (pp. 23–40). Warszawa: Fundacja Instytut Spraw publicznych.

- Saradamov, I. (2005). Civil Society’ and the limits of democratic assistance. Government and Opposition, 40(3), 379–402.

- Scrivens, K., & Smith, C. (2013). Four Interpretations of Social Capital. OECD Statistics Working Papers, 06. Retrieved April 20, 2018, from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=STD/DOC(2013)6&docLanguage=En.

- Skrenty, Ż. (2013). Zaufanie obywateli do organów władzy publicznej w świetle orzecznictwa sądowego i poglądów doktryny [Confidence of citizens to public authorities in the light of judicial decisions and doctrinal views]. Studia Lubuskie, IX, 97–112.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2006). Democracy in Europe. Oxford: OUP.

- Sodaro, M. J. (2004). Comparative politics. A global introduction. New York: Mc Graw Hill.

- Stolle, D., Hooghe, M., & Micheletti, M. (2005). Politics in the supermarket: Political consumerism as a form of political participation. International Political Science Review, 26(3), 245–269. doi:10.1177/0192512105053784

- Stolle, D. (2007). Social capital. In R. J. Dalton, & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (pp. 655–674). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stolle, D., & Howard, M. M. (2008). Civic engagement and civic attitudes in cross-national perspective: Introduction to the symposium. Political Studies, 56(1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00714.x

- Szkudlarek, P. (2017). State in the assessment of students in Poland, Lithuania and Slovakia in the light of research on social capital. Public Policy and Administration, 16(4), 644–656.

- Sztompka, P. (2007). Zaufanie. Fundament społeczeństwa [Trust. The foundation of society]. Kraków: Znak.

- Torcal, M., & Montero, J. R. (1998). Facets of social capital in new democraties. The Formation and Consequences of Social Capital in Spain, Working Paper, 259, 1–34.

- Tyszkowska, M. (1990). Aktywność i działalność dzieci i młodzieży [Activity and action of children and youth]. Warszawa: WSiP.

- Vilmorus. (2017). Do you trust or distrust in these Lithuania's institutions? Retrieved from: http://www.vilmorus.lt/index.php?mact=News,cntnt01,detail,0&cntnt01articleid=7&cntnt01returnid=32 [25.05.2018].

- Woolcook, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. ISUMA - Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 11–17.