?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the causal relationships between tourism, physical capital, human capital, household consumption expenditure and economic growth for the period 1981–2014 using Structural Breaks tests, Autoregressive Lag (Distributed A.R.D.L.) approach and Granger causality test. There is one cointegrating relationship between these variables, while the V.E.C.M. comprises both a short- and long-run relation. Tourism has a negative impact on Iranian's economic growth both in the short- and long-run. The results showed there is unidirectional causality running from international tourism to economic growth. Our findings have also empirically verified the presence of the Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis (T.L.G.H.) in Iran. Tourism could be an effective substance for the growth of the Iranian economy. They showed that tourism is in part an endogenous growth process, requiring a systematic allocation of resources to sustain its development for local and regional economies.

JEL:

1. Introduction

It is more than a decade that tourism has been converted into the biggest industry in the world and it is constantly developing. Today this industry is a great income resource for many countries and most governments support tourism industry actively.

Over the past few decades, the expansion and diversification in tourism sector has remarked. When we compare the tourism sector to other economic sectors we observe the fastest growth rate in the tourism sector. This growth is continuous by occasional shocks. According to the World Tourism Organization (Citation2015), international tourist arrivals in the world have surged from 278 million in 1980 to 1133 million in 2014. Moreover, international tourist arrivals have grown by 4.4% and reached 1200 million in 2015 (UNWTO, Citation2016). The international tourist arrivals are expected to grow by 3.3% in a year over the period 2010–2030 and are expected to reach 1.8 billion by 2030.

The major factor of economic growth in many parts of the world has been tourism, since all sectors are related with this industry, both directly and indirectly. Tourism is very important for many countries, due to revenues generated from tourism consumption of products and services, from taxes collected by the tourism industry, as well as opportunities for employment in the tourism service industry. Over the past several decades, the relationship between tourism spending expenditure and economic growth for both developing and developed countries has been extensively researched. Knowledge of the causal relationship between tourism expenditure spending and economic growth is of particular importance to policymakers, as tourism policies are becoming major concerns for these countries.

Tourism, despite the ongoing debates about its definition over the past decades, is commonly recognised as a human activity that defines the demand for and supply of its products and the usage of resources that may result in either positive or negative socio-economic consequences at both national and international level. The significance of the economic approach and perspective to understanding this human activity is widely known. As far as both its demand and supply are concerned, tourism has distinct characteristics which set it apart from other economic activities (Stabler, Papatheodorou, & Sinclair, Citation2010).

Iran has great attractions, so this potential should be exploited in a rational way to have some valuable economic benefits. The tourism and growth nexus can be justified through various channels. How it is admitted fact on the all the hands that increase in tourism leads to balance of payments progress through reduction in current account deficit and increase G.D.P. growth. Various studies validate the long-run relationship between tourism and growth (Brida & Risso, Citation2009).

Therefore, given the importance of the tourism industry, the objective of this research is to study the causal relationship between the tourism industry and economic growth in Iran during the years 1980–2014 using a vector auto-correction model and the Granger causality test. The G.D.P. variable has been applied as economic growth index tourism receipts as the replacement variable of tourism industry.

The rest of this article is organised as follows: The next section surveys the literature. Section 3 explains the theoretical model and the data used in this study is explained. Section 4 discusses the econometric procedures followed. The empirical findings will then be presented in Section 5 followed by concluding remarks and policy implications in Section 6.

2. Literature survey

The relationship between tourism and economic growth can be analysed by testing three hypotheses:

the Tourism-Led Economic Growth hypothesis

the Economic-Driven Tourism Development hypothesis

reciprocal causality hypothesis (Oh, Citation2005).

The first hypothesis states that tourism leads economic growth and the causal relationship should be unidirectional running from tourism to economic growth for this. The second hypothesis describes how economic growth drives tourism and that there must be unidirectional causality going from economic growth to tourism. Hypothesis 3 combines both hypotheses 1 and 2, and predicts bidirectional causality between economic growth and tourism.

Because of the potential economic benefits of tourism, such as increases in foreign exchange earnings, income, employment and taxes (Balaguer & Cantavella-Jorda, Citation2002; Dritsakis, Citation2004; Durbarry, Citation2002). It is generally believed that tourism has contributed positively to economic growth. Over recent decades, the relationship between tourism expenditure and economic growth for both developing and developed countries has been widely researched. Researchers showed that the trickledown effect of tourism development not only enhances tourism sector but also generates overall economic growth (Lee and Chang, Citation2008).

The relationship between economic growth and international tourism has long been of interest and empirically investigated in the tourism-led growth literature. The effects of international tourism in developing countries have also long been of interest to both scholars and policymakers (Clancy, Citation1999).

Chen and Devereux (Citation1999) argued that tourism may reduce welfare for trade regimes dominated by export taxes, or import subsidies. Using a theoretical framework, they demonstrated that foreign direct investment in the form of tourism is, for the most part, beneficial while tourist immiserisation is also possible in sub-Saharan Africa.

A bidirectional relationship has also been discovered by some researchers, Dritsakis (Citation2004) using time-series data for the period 1960–2000 in Greece and a V.E.C.M., he found that tourism and economic growth mutually Granger-cause each other. The tourism-led growth hypothesis (T.L.G.H.) is confirmed through cointegration and causality testing. Similarity Gunduz and Hatemi (Citation2005) empirically confirmed the T.L.G.H. for Turkey using the leveraged bootstrap causality tests. They found unidirectional causality running from international tourist arrivals to economic growth of Turkey. On the other hand, Oh (Citation2005) examined the casual relation between tourism development and economic growth over the period 1975–2001 in Korea. The results suggested that growth-led tourism hypothesis is confirmed through cointegration and causality tests in Korea.

Using structural break tests, Lee (Citation2008) studied the changes affecting the consistency and stability of long-run relationship between tourism development and G.D.P. for the period 1959–2003 in Taiwan. The experimental causal relationship between real G.D.P. (R.G.D.P.), tourism expenditure and the real exchange rate has been investigated in a multivariate model and tested the unit root and cointegration tests used to evaluate the structural break. Empirical evidence clearly showed a bidirectional causal relationship between tourism and economic growth. Finally, changes in the political and economic shocks and inertia control the tourism sector and some policies.

With the annual data from 1980 to 2007, Nanthakumar, Ibrahim and Harun (Citation2008) examined the hypothesis of economic-driven tourism growth in Malaysia using a trivariate model with R.G.D.P., total tourist arrivals and C.P.I.. The findings showed that bidirectional relationship between C.P.I. and tourist arrivals and between C.P.I. and G.D.P., whilst suggested economic factors drive Malaysia’s tourism sector.

Brida and Risso (Citation2009) explored T.L.G.H. by applying Granger causality and impulse response function for period 1988–2008. They applied tourism expenditure as a proxy of tourism development and empirics discovered unidirectional causality running from tourism expenditure and exchange rate to economic growth for Chile. The same findings have been derived for Singapore by Katircioǧlu (2011), using annual data series from 1960–2007.

In South Africa, Akinboade and Braimoh (Citation2010) investigated multivariate V.A.R. model and Sims Granger causality for the tourism-led economic growth and concluded the existence of tourism-led economic growth. For Malaysia from January 1995 to February 2009, Tang (Citation2011) studied the casual relation between tourism development and economic growth based on a dataset of 12 different tourism markets using the Error Correction Model (E.C.M.) in Malaysia. The empirical results showed that only five out of 12 tourism markets contribute to economic growth in the long-run, and six out of 12 tourism markets in the short-run.

Further, Savaş, Beşkaya, and Şamiloğlu (Citation2012) used two proxies for tourism development (tourism arrivals and tourism expenditure) and analysed the T.L.G.H. for the period 1984Q1–2008Q3 for Turkey. They indicated that tourism causes economic growth.

A recent study by Georgantopoulos (Citation2012) found a unidirectional causal relationship between tourism expenditure and real gross domestic product (R.G.D.P.) in Greece for the period 1988–2001, running from the tourism expenditure to the R.G.D.P. This finding was made on the basis of annual time-series data on Greece’s tourism receipts, R.G.D.P. and the real effective exchange rate. In case of Romania, Surugiu and Surugiu (Citation2013) applied V.E.C.M. Granger causality and Impulse response function for 1988–2009. The evidence confirmed the existence of T.L.G.H.

Further, Tang and Tan (Citation2013) took 12 different tourism markets and applied combine cointegration Granger causality approach to analyse the T.L.G.H. They used monthly time period form 1995m1–2009 m2 and confirmed the existence of T.L.G.H. Similarly, Tang and Abosedra (Citation2014) confirmed the T.L.G.H. using a multivariate model derived by Solow for the period 1975–2011 in Malaysia. After that, Tang and Abosedra (Citation2015) provided evidence for existence of T.L.G.H. using tourism arrivals as a proxy of tourism development for Malaysia.

3. Data, specification models

3.1. Data

The data used in this article was collected over the period 1980–2014. The variables of this study are real per capita G.D.P. (constant 2010 US$), the per capita international tourists receipts in Iran. Physical capital is ratio of fixed capital formation a percent of R.G.D.P. G.P.I. is of secondary and tertiary school enrollment used as measure of investment in human capital. H.H.C. shows household consumption expenditure is obtained from World Bank. The data are obtained from World Development Bank (World Bank, Citation2015).

3.2. Model

To determine the sensitivity of income growth rate to tourism we used investment in physical and human capital The following equation is:

(1)

(1)

The short- and long-run relationship between R.G.D.P. and tourism receipts are examined in natural logarithms. the following linear logarithm form is proposed:

(2)

(2)

Where GDP is the real per capita G.D.P. and TOUR is per capita tourist receipts in US$; GCF is the gross fixed capital formation as a percent of R.G.D.P. used as a proxy for investment in physical capital, G.P.I. is proxy of human capital. The impact of household consumption expenditures (H.H.C.it) on economic growth is controversial. Neoclassical economic theory posits (Solow, Citation1956;) that higher household consumption expenditures tend to lower economic growth by lowering investment because of reduced savings.

4. Econometric methods

4.1. Unit root test

The Phillips and Perron (P.P.) (1988) Unit Root Tests are used (Dickey & Fuller, Citation1981). The P.P. procedures, which compute a residual variance that is robust to auto-correlation, are applied to test for unit roots as an alternative to Augmented Dickey-Fuller (A.D.F.) unit root test.

Having tested for the stationarity of each time series and found that all of them are I (1), the next step is to examine whether there exists a long-run relationship between the variables in our model. The cointegrating relationship has been tested, using the tests proposed by Johansen (Citation1988) and Johansen and Juselius (Citation2009). Johansen’s (Citation1991) tests are based on reduced rank regression in which the maximum likelihood estimates are computed in the multivariate cointegration model with Gaussian errors. One of the advantages of this technique is that it allows one to draw a conclusion about the number of cointegrating relationships among observed variables. Another advantage is not requiring a priori assumptions of endogeneity or exogeneity of the variables.

Cheung and Lai (Citation1993) mentioned that the trace test is more robust than the maximum Eigen value test for cointegration. The Johansen trace test tries to determine the number of cointegrating vectors among variables. There should be at least one cointegrating vector for a possible cointegration.

To investigate a long-run relationship between the variables under consideration, the bounds test for cointegration within the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (A.R.D.L.) modelling approach is applied in this study. The A.R.D.L. modelling approach involves estimating the following E.C.M.s. The null hypothesis of the series has a unit root against the alternative of stationary. The A.R.D.L. framework is as follows:

(3)

(3)

Where ECMt–1 is is gained from the following equation:

(4)

(4)

The Error Correction Term (ECMt−1) indicates how quickly the variables return to the long-run equilibrium and it should have a negative sign. The diagnostic tests and stability are also conducted. Granger (Citation1988) used the V.E.C.M.

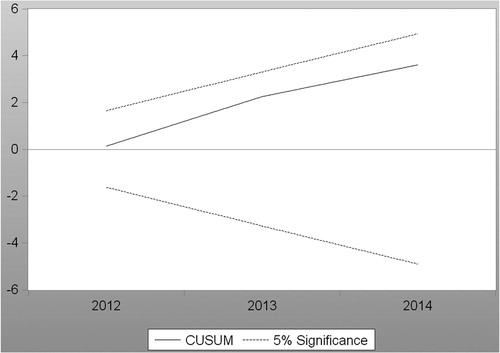

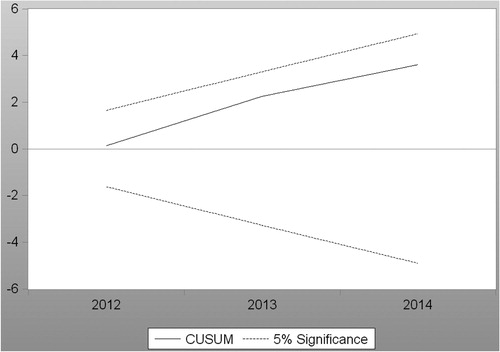

In addition, the stability of the E.C.M. was checked by the Cumulative sum (C.U.S.U.M.) and cumulative sum of squares (C.U.S.U.M.S.Q.) tests.

5. Empirical results

shows some descriptive statistics and pair-wise correlations of the variables for the period 1980–2014 in Iran.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for variables.

The N.G.-Perron unit root test results are reported in . The all variables are stationary after taking first difference, I(1).

Table 2. N.G.–Perron unit root test results.

We apply the Perron structural break unit root test (Perron, Citation1989). This test analysis the unit root problem in the existence of single unknown structural break. shows that the Perron structural break unit root test results.

Table 3. Perron structural unit root test.

The results show that all series are stationary at 1st difference in the structural breaks method. The structural breaks in 2006, 2011 and 2012 are found for economic growth, tourism receipts, physical capital, human capital and household consumption expenditures, respectively.

Since both unit root tests consistently suggest that all variables are I (1), we can proceed to test for the presence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between economic growth and its determinants using in Iran the Johansen-Juselius cointegration approach. The results are presented in and .

Table 4. Unrestricted cointegration rank test (trace).

Table 5. Unrestricted cointegration rank test (trace).

The null hypothesis of no cointegration against alternative relationship of at one cointegrating relationship and cannot be released to any model at a significance level of 5%. There are three cointegration relationships between the variables. Thus, there is a significant long-run relationship between economic growth and its determinants in Iran.

We found that the variables are cointegrated; we estimate the long-run relationship between growth and tourism using the V.E.C.M. and estimate the short- and long-run coefficients.

Table 6. Error correction model (E.C.M.) for short-run elasticity Selected Model: A.R.D.L. (2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0).

Table 7. Estimated long-run coefficients using the A.R.D.L. approach selected model: A.R.D.L. (2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0).

In and all coefficients can be interpreted as short-run and long-run elasticity. We applied D.U.M. 2011 for the model. Variables are statistically significant at the 5% and 10% level in the short- and long-run.

The important short-run dynamics outcome is the coefficient of E.C.M. The ECMt−1 is correct sign, and significant.

The coefficient of ECMt−1 is nearly −0.21% of the speed of adjustment from short-run back to the long-run equilibrium. The ECMt−1 shows 4.75 periods to equilibrium.

Tourism has a negative impact on economic growth in both short- and long-run. However, a 1% increase in international tourism, a decrease in R.G.D.P. of 0.01 %, 0.08 % in both the short- and long-run remain constant. These findings showed that tourism could not encourage Iran’s economic growth, thus supporting the T.L.G.H. The results of our study are consistent, for example Oh (Citation2005) and Katircioglu (2009), which have a stance of growth led-tourism hypothesis.

Moreover, physical capital has a positive and significant impact of on economic growth. Hence, 1% increases physical capital increases 0.15%, 0.12% in economic growth in the short- and long-run. While, the human capital has negative and significant on economic growth. It presented that a 1% increase in human capital causes a decrease of 0.14%, −0.12% economic growth in the short- and long-run, respectively.

In addition, a positive relationship between household consumption expenditures and economic growth is noticed. A 1% increase in household consumption expenditures increase by 0.47%, 0.39% economic growth in the short- and long-run.

The diagnostic statistics such as the L.M. test, A.R.C.H. test, Ramsey R.E.S.E.T. test and white heteroskedasticity test clarify that there is no serial correlation; residual terms are normal distributed, no autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity, white Heteroscedasticity. Further, the stability of parameters is tested by C.U.S.U.M. and C.U.S.U.M.S.Q. suggested by Brown, Durbin, and Evans (Citation1975). The plot of both C.U.S.U.M. and C.U.S.U.M.S.Q. are presented in and . The parameters are stable in the model.

Figure 1. Plot of cumulative sum of recursive residuals.

Note: The straight line represents critical bounds around 5% significance level.

Figure 2. Plot of cumulative sum squares of recursive residuals.

Note: The straight line represents critical bounds around 5% significance level.

Engle-Granger (Citation1987) show that the relationship can be unidirectional and/or bidirectional. Moreover, this causality relationship is for short- and long-run causality. There is Granger causality between these variables in .

Table 8. Granger causality test.

We applied the Granger causality approach. The results of Granger causality show the causality relationship between tourism receipts, physical capital, human capita and household consumption expenditure and economic growth.

In long-run, the unidirectional causality is running from tourism receipts and household consumption expenditure to economic growth. We found bidirectional causality between physical capital and human capital and economic growth in long- run in Iran. Tourism could be an effective facilitator for Iran’s economic growth. This is in contrast to the findings of Nanthakumar et al. (Citation2008), but consistent with Tang (Citation2011). Tourism development is of great importance to Iran’s economic growth.

6. Conclusion

This article empirically examines the Johansen technique for cointegration, the A.R.D.L. test and Granger causality test between tourism receipts, physical capital, human capital, household consumption expenditure and economic growth for the period 1980–2014 in Iran. As we found that all the variables are I (1), we applied the Johansen-Juselius cointegration test to determine the presence of cointegration and structural break tests. The findings of the test suggested that economic growth and tourism receipts are cointegrated. Therefore, we estimate the short- and long-run relationships between economic growth and its variables.

The key finding is that the T.L.G.H. can be established for Iran. The results indicate that is unidirectional causality running from tourism to economic growth in Iran. The more the country prospers the more stable and sounds are the economic, social and political situations. The prospective tourists will have more confidence to visit Iran. It is therefore imperative that government institutions, tourism planners and investors recognise the implications of their actions in the interest of long-run economic viability of the tourism sector. Also, the growth of tourism-based investments and tourism capacity could stimulate further economic growth. However, this potential remains largely untapped. In addition, the conventional sources of growth such as investment in physical and human capital and the ability of households to have the wherewithal of spending on health, housing, nutrition, and other household items can enhance their productivity and spur their economic growth.

Government should develop tourism sector by providing basic facilities such as, roads, infrastructural development, communication sources and good transport system. Tourism contributes to a reduction of poverty by generating employment. The government should provide subsidies to the tourism industry by a reduction in the tax ratio and travelling expenses. Law and order and security are other points that government should focus on to improve economic growth via tourism development.

This potential is realised if the basics exist. We recommend it is important to pay special attention to the tourism industry in order to reach higher economic growth in Iran. The tourism development programme of the country should be compiled in the field of economic development. We also recommend that authorities should pay attention to the growth of the tourism industry through planning, thus attracting foreign tourists' attention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Akinboade, O. A., & Braimoh, L. (2010). International tourism and economic development in South Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(2), 149–163. doi: 10.1002/jtr.743

- Balaguer, J., & Cantavella-Jorda, M. (2002). Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: The Spanish case. Applied Economics, 34(7), 877–884. doi: 10.1080/00036840110058923

- Brida, J. G., & Risso, W. A. (2009). Tourism as a factor of long-run economic growth: An empirical analysis for Chile. European Journal of Tourism Research, 2(2), 178.

- Brown, R. L., Durbin, J., & Evans, J. M. (1975). Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relations over time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 37, 149–163. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1975.tb01532.x

- Chen, L. L., & Devereux, J. (1999). Tourism and welfare in sub-Saharan Africa: A theoretical analysis. Journal of African Economics, 8(2), 209–227. doi: 10.1093/jae/8.2.209

- Cheung, Y. W., & Lai, K. S. (1993). Finite-sample sizes of Johansen's likelihood ratio tests for cointegration. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 55(3), 313–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.1993.mp55003003.x

- Clancy, M. J. (1999). Tourism and development: Evidence from Mexico. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00046-2

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1981). Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica, 49(4), 1057–1079. doi: 10.2307/1912517

- Dritsakis, N. (2004). Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: An empirical investigation for Greece using causality analysis. Tourism Economics, 10(3), 305–316. doi: 10.5367/0000000041895094

- Durbarry, R. (2002). The economic contribution of tourism in Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research, 29, 862–865.

- Engle, R., & Granger, C. (1987). Cointegration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55, 257–276.

- Georgantopoulos, A. G. (2012). ‘Forecasting tourism expenditure and growth: A VAR/VECM analysis for Greece at both aggregated and disaggregated levels. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 96, 155–167.

- Granger, C. W. J. (1988). Some recent development in a concept of causality. Journal of Econometrics, 39(1–2), 199–211. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(88)90045-0

- Gunduz, L., & Hatemi, J. A. (2005). Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid for Turkey? Applied Economics Letters, 12, 499–504.

- Johansen, S. (1988). Statistical Analysis of cointegration vectors. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12, 231–254.

- Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrics, 59(6), 1551–1580. doi: 10.2307/2938278

- Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (2009). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with application to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–221.

- Katircioglu, S. (2009). Tourism, trade, and growth: The case of Cyprus. Applied Economics, 41(21), 2741–2751. doi: 10.1080/00036840701335512

- Lee, C. G. (2008). Tourism and economic growth: The case of Singapore. Regional and Pectoral Economic Studies, 8(1), 89–98.

- Lee, C. C., & Chang, C. P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tourism Management, 29, 180–192.

- MacKinnon, J., Haug, A. & Michelis, L. (1999). Numerical distribution functions of likelihood ratio tests for cointegration. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 14, 563.

- Nanthakumar, L., Ibrahim, Y., & Harun, M. (2008). Tourism development policy, strategic alliances and impact of consumer price index on tourist arrivals: The case of Malaysia. An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 3(1), 83–98.

- Oh, C. O. (2005). The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Manage, 26 (1), 39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.014

- Perron, P. (1989). The great crash, the oil price shock, and the unit root hypothesis. Econometrica, 57 (6), 1361–1401. doi: 10.2307/1913712

- Phillips, P. C., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.2.335

- Savaş, B., Beşkaya, A. and Şamiloğlu, F. (2012). Analyzing the impact of international tourism on economic growth in Turkey. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisatve İşletme Dergisi, 6(12), 121–136.

- Solow, R. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94.

- Stabler, M. J., Papatheodorou, A., & Sinclair, M. T. (2010). The economics of tourism (2nd ed.), Abingdon: Routledge.

- Surugiu, C., & Surugiu, M. R. (2013). Is the tourism sector supportive of economic growth? Empirical evidence on Romanian tourism. Tourism Economics, 19(1), 115–132. doi: 10.5367/te.2013.0196

- Tang, C. F. (2011). Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid for Malaysia? A view from disaggregated tourism markets. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(1), 97–101. doi: 10.1002/jtr.807

- Tang, C. F., & Abosedra, S. (2014). Small sample evidence on the tourism-led growth hypothesis in Lebanon. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(3), 234–246. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2012.732044

- Tang, C. F., & Abosedra, S. (2015). Does tourism expansion effectively spur economic growth in Morocco and Tunisia? Evidence from time series and panel data. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 8(2), 127–145. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2015.1113980

- Tang, C. F., & Tan, E. C. (2013). How stable is the tourism-led growth hypothesis in Malaysia? Evidence from disaggregated tourism markets. Tourism Manage, 37, 52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.014

- World Tourism Organization. (UNWTO). (2015).

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2016). Annual report.

- World Bank. (2015). World development indicators, available online at: http://data.worldbank.org/