Abstract

This paper analyses the relationships between the socioemotional wealth, entrepreneurial orientation and international performance of family firms. This research is pioneering in that it seeks to explain the international performance of family firms from the non-economic perspective of entrepreneurial orientation determined by socioemotional wealth. Second generation structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.2.8 software was applied to data from 106 Spanish family firms. The study shows that considering socioemotional wealth substantially improves the capacity of entrepreneurial orientation to explain variation in the international performance of family firms. When only entrepreneurial orientation is included in the model, the explained variance of international performance is 34.2%. However, when socioemotional wealth is included in the model as an antecedent of international performance, the explained variance increases to 42.6%.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in the number of publications that study family businesses to learn more about their behaviour (Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, Citation2005; López-Fernández, Serrano-Bedia, & Pérez-Pérez, Citation2016; Nordqvist & Melin, Citation2010; Sharma, Chrisman, & Gersick, Citation2012; Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, Citation2004). There are three reasons for this interest. First, family firms are the most common form of enterprise worldwide (Gedajlovic, Carney, Chrisman, & Kellermanns, Citation2012; Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Nunez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, Citation2007; Hiebl, Quinn, Craig, & Moores, Citation2018; Masulis, Pham, & Zein, Citation2011; Poza & Daugherty, Citation2013). Second, family firms are responsible for a large part of the economic growth and well-being of many countries (Astrachan & Shanker, Citation2003; Jaskiewicz, Combs, & Rau, Citation2015; Pejic Bach, Aleksic, & Merkac-Skok, Citation2018). Third, the family firm is the form of enterprise that creates most employment (Chang, Memili, Chrisman, Kellermanns, & Chua, Citation2009; Fan, Wei, & Xu, Citation2011; Matthews, Hechavarria, & Schenkel, Citation2012). Spain is no exception, and the importance of family firms in Spain is reflected by various indicators. According to Corona and Del Sol (Citation2016) family enterprises represent 89% of companies, 57% of GDP and 67% of private employment in Spain.

The family firm has numerous definitions. It is therefore difficult to reach a consensus on how best to provide a generally accepted definition. Nevertheless, two features are common to most definitions of the family firm (Franco & Prata, Citation2019). The first is ownership of capital. In family firms, most shares belong to one or more family members. The second is management. In family firms, several members of the family participate in the management of the business (Kallmuenzer, Hora, & Peters, Citation2018). Analysing family firms is a challenge because of the wide variety of family firms that exist ( Cennamo, Berrone, Cruz, & Gomez-Mejia, Citation2012; Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012; Llanos-Contreras, & Santos, 2018 ) as a result of varying levels of family involvement in the business (Samara & Berbegal-Mirabent, Citation2018).

Many companies, including family firms, maintain or even improve their competitiveness by seeking to expand their activity beyond home borders (Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida, Citation2000; Sapienza, Autio, George, & Zahra, Citation2006), thereby reducing their dependence on domestic or national markets (Ciravegna, Majano, & Zhan, Citation2014). Therefore, this study examines which factors influence the international performance of family firms. When addressing this question, it is of special interest to consider the role of aspects such as entrepreneurial orientation (Hernández‐Perlines, Moreno‐García, & Yáñez-Araque, Citation2017; Schepers, Voordeckers, Steijvers, & Laveren, Citation2014) and socioemotional wealth (Berrone et al., Citation2012; Gómez-Mejía, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, Citation2011).

In this study, our goal is to link the aspects mentioned earlier, namely international performance, entrepreneurial orientation and socioemotional wealth. The choice of these variables owes to their strong correlation, which has been explored in previous studies. For example, Hernández-Perlines (Citation2018) analysed the positive influence of entrepreneurial orientation on the international performance of family firms. Similarly, Hernández-Perlines, Moreno-García, and Yáñez-Araque (Citation2019) analysed the positive effect of socioemotional wealth on entrepreneurial orientation. The opportunity in this study is provided by the analysis of how socioemotional wealth is capable of explaining the international performance of family firms through its effect on entrepreneurial orientation. The research question addressed by this study is whether the effect of entrepreneurial orientation on the international performance of family firms differs when socioemotional wealth is considered as an antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation. This question can be broken down into three parts.

First, why consider international performance? The answer is that although research on internationalisation has advanced considerably in recent years, there are still unanswered questions that arise as a result of the increasingly global and competitive environment where companies operate (Werner, Citation2002).

Second, why study entrepreneurial orientation? Scholars such as Eddleston, Kellermanns, and Zellweger (Citation2012) have reported that one of the main problems with family firms is their survival rate. The question is, how can their survival rate be improved? Kellermanns and Eddleston (Citation2006) claimed that the survival of family firms could be improved through entrepreneurship. There are different proposals to analyse entrepreneurship in family firms, although the most common one is to study entrepreneurship through entrepreneurial orientation (Cruz & Nordqvist, Citation2012; Kellermanns, Eddleston, & Zellweger, Citation2012; Lumpkin, Brigham, & Moss, Citation2010; Naldi, Nordqvist, Sjöberg, & Wiklund, Citation2007; Zahra, Citation2005). In addition, family firms provide a context that can help us develop a better understanding of entrepreneurial orientation (Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, Citation2018). Accordingly, the number of studies that analyse entrepreneurial orientation in the family business is increasing (Lee & Chu, Citation2017).

Third, why analyse socioemotional wealth? The justification for considering socioemotional wealth is that it is a key factor in family firm entrepreneurship (Kellermanns & Eddleston, Citation2006), where it is necessary to consider the interaction between the business and the family (Franco & Prata, Citation2019). Socioemotional wealth offers a new research perspective on non-economic aspects of family firms (Gómez-Mejía, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, Citation2011), and, in recent years, it has become a relevant factor in explaining the behaviour of family firms (Berrone et al., Citation2012; Chua, Chrisman, & De Massis, Citation2015; Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2007; Martínez-Romero & Rojo-Ramírez, Citation2016; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Citation2014). The socioemotional wealth approach suggests that family firms have non-economic objectives (Berrone et al., Citation2012; Martínez-Romero & Rojo-Ramírez, Citation2017) that affect their purely economic objectives (Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012). From a socioemotional wealth perspective, it is suggested that family firms make decisions to protect their socioemotional wealth, even if these decisions entail financial losses (Berrone et al., Citation2012). Therefore, socioemotional wealth offers a comprehensive theoretical framework that enables analysis of different aspects of the family firm (Kabbach de Castro, Crespi-Cladera, & Aguilera, Citation2016). Socioemotional wealth also influences the entrepreneurial orientation of the family firm by helping the family achieve its non-economic goals of improving its reputation, guaranteeing the employment of family members and securing family control through generational renewal (Alonso-Dos-Santos & Llanos-Contreras, Citation2019; Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2011). This study helps close the gap in the literature left by a lack of research that uses the non-economic perspective to explain the entrepreneurial orientation of family firms.

2. Theory and hypotheses

The increasing globalisation and competitiveness of the market make organisational performance a key concern for firms (Ferreira, Fernandes, & Ortiz, Citation2018). In the case of family firms, performance, in its different forms, is still a key research area (Franco & Prata, Citation2019). The primary goal of this study is to determine how best to explain the international performance of family firms. To pursue this goal, we use two concepts that are strongly correlated with this performance, namely entrepreneurial orientation and socioemotional wealth.

Two theoretical frameworks support this study. The first is the theory of dynamic capabilities (Makadok, Citation2001; Prahalad & Hamel, Citation1990; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Citation1997). This framework is relevant because entrepreneurial orientation is a capability that helps companies adapt to changes to remain competitive (Hernández-Perlines et al., Citation2017; Jaskiewicz et al., Citation2015). The second framework that supports this study is that of socioemotional wealth, which entails the consideration of non-economic aspects in relation to the family firm (Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2011). According to this theoretical approach, the decision-adoption process in the family firm revolves around protecting its socioemotional wealth (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia, & Larraza-Kintana, Citation2010; Cennamo, Berrone, Cruz, & Gomez-Mejia, Citation2012; Glover & Reay, Citation2015; Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2007), even if doing so incurs certain financial risks (Berrone et al., Citation2012). In this study, we adopt a non-economic view of entrepreneurial orientation. We consider that socioemotional wealth determines entrepreneurship in the family firm by helping the family to achieve its non-economic objectives such as improving its reputation, guaranteeing the employment of family members and ensuring family control of the firm through generational renewal (Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2011). This perspective helps us understand the process of strategic management of family firms, which is characterised by the interaction between the business and the family (Kallmuenzer, Hora, et al., Citation2018).

2.1. Socioemotional wealth as an antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation

The number of studies that examine the role of emotions in business performance is growing (Rizvi & Oney, Citation2018). In family firms, the family, ownership and management must live side by side, which makes for a unique decision-making process (Kallmuenzer, Hora, et al., Citation2018). The behaviour of the family firm is determined by non-economic family goals that create socioemotional wealth (Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012) and emotional value when focused on the family (Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, & Chua, Citation2012). In family firms, the members of the family feel emotional attachment to other family members, strongly identifying with the family firm, which is often seen as an extension of the family (Kallmuenzer, Hora, et al., Citation2018).

The approach of socioemotional wealth offers a way of analysing non-economic family goals. This theoretical alternative is based on the model of behavioural agency (Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012) and is suited to the study of the family firm because it integrates family, personal and organisational goals (Llanos-Contreras & Santos, Citation2018), which occasionally clash with one another (Franco & Prata, Citation2019).

The concept of socioemotional wealth was coined by Gómez-Mejía et al. (Citation2007), who defined socioemotional wealth as ‘the group of non-financial aspects from the company that satisfy affective needs of the family, such as identity, capacity of exerting family influence and perpetuation of the family dynasty’. The concept of socioemotional wealth has been widely analysed in research on family firms (e.g. Cruz, Justo, & De Castro, Citation2012; Goel, Voordeckers, van Gils, & van den Heuvel, Citation2013; Gómez‐Mejía, Makri, & Kintana, Citation2010; Naldi, Cennamo, Corbetta, & Gomez‐Mejia, Citation2013; Schepers et al., Citation2014; Sciascia, Mazzola, & Kellermanns, Citation2014; Vandemaele & Vancauteren, Citation2015). Socioemotional wealth relates to the decisions that the family firm adopts to protect its socioeconomic wealth, even if these decisions come at a cost (Berrone et al., Citation2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., Citation2007; Naldi et al., Citation2013). Kellermanns et al. (Citation2012) broadened the concept of socioemotional wealth by considering two perspectives (one positive and one negative) that are essential when analysing socioemotional wealth in family firms (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Citation2014).

From the first perspective, Cennamo et al. (Citation2012) proposed that socioemotional wealth allows family firms to adopt a policy of proactive participation of the interested parties, given that the decision-adoption process is determined by identification of the dimensions of socioemotional wealth. From the second perspective, Schepers et al. (Citation2014) analysed the moderating effect of socioemotional wealth on the relationship between the performance and entrepreneurial orientation of family firms, concluding that socioemotional wealth limits this relationship. However, family relationships and innovative capacity provide a strong competitive advantage (Eddleston, Kellermanns, & Sarathy, Citation2008).

The academic literature offers intense debate over how to measure socioemotional wealth. In early studies, socioemotional wealth was measured as a proxy of ownership and family management (e.g. Berrone et al., Citation2010; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; Vandemaele & Vancauteren, Citation2015; Zellweger, Nason, & Nordqvist, Citation2012). Other studies have tried to capture socioemotional wealth in terms of the strategic orientation of small and medium-sized enterprises (e.g. Goel et al., Citation2013; Schepers et al., Citation2014). However, the review of socioemotional wealth by Berrone et al. (Citation2012) is the most widely cited because of its links with other theoretical approaches. Berrone et al. (Citation2012) proposed five dimensions to measure socioemotional wealth: family control and influence, identification of family members with the company, binding social ties, emotional attachment of family members and renewal of family bonds with the company through dynastic succession. These five dimensions are known as FIBER. This socioemotional wealth measurement model was used by Cennamo et al. (Citation2012) to analyse how socioemotional wealth allows family companies to adopt actions for the proactive participation of interested parties. Debicki, Kellermanns, Chrisman, Pearson, and Spencer (Citation2016) reformulated this socioemotional wealth measurement model by evaluating the importance that the owners and managers of family firms attach to the elements of the model. Recent studies have scrutinised the FIBER model, incorporating three aspects of great importance for the family business: the importance of the family in decision making, family continuity and family enrichment (Alonso-Dos-Santos & Llanos-Contreras, Citation2019).

Control and influence by the family allows family firms to implement proactive strategic decisions that entail innovation and even some risk (Habbershon & Pistrui, Citation2002; Kellermanns et al., Citation2012). In this sense, family participation enhances the positive effect of innovative capacity on growth (Casillas & Moreno, Citation2010) and promotion of the entrepreneurial spirit (Zahra, Citation2005). Family members tend to seek company behaviour that is prone to improving the social status of the family firm (Davis, Pitts, & Cormier, Citation2000), and their identification with the company improves performance (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003; Zellweger & Nason, Citation2008). The strong ties between family members affect the acknowledgment of entrepreneurial opportunities (Jack, Citation2005) and resource accumulation (Khayesi, George, & Antonakis, Citation2014).

Emotions are another distinctive attribute of family firms (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, Citation2008; Berrone et al., Citation2012; Zellweger & Astrachan, Citation2008) that could play an important role in company behaviour (Goss, Citation2005) because of their impact on decision making (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, Citation2008). Baron (Citation2008) reported that affect (feelings and emotions) could increase creativity and opportunity recognition in risky environments. Succession is one of the biggest challenges facing family firms (Le Breton‐Miller, Miller, & Steier, Citation2004) because, in these companies, strategic decisions are long-term oriented (Kallmuenzer, Hora, et al., Citation2018; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Citation2005; Miller, Le Breton‐Miller, & Scholnick, Citation2008). Succession in family firms is determined by the degree of involvement of descendants and the way they perceive the rewards obtained by their predecessors (Wang, Wang, & Chen, Citation2018). Eddleston et al. (Citation2012) showed that long-term orientation is positively related to entrepreneurial spirit. Delmas and Gergaud (Citation2014) reported that family companies with transgenerational intent tend to adopt innovative practices, improving entrepreneurship (Zahra et al., Citation2004). Martínez-Alonso, Martínez-Romero, and Rojo-Ramírez (Citation2018) reported that socioemotional wealth positively affects the ability of family businesses to innovate. Finally, entrepreneurial orientation is affected by economic and non-economic factors ( Pejic Bach et al., Citation2018) , including socioemotional wealth (Hernández-Perlines et al., Citation2019). Jaskiewicz et al. (Citation2015) affirmed that socioemotional wealth is one of the most relevant factors to explain entrepreneurship in family firms. Based on these findings, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

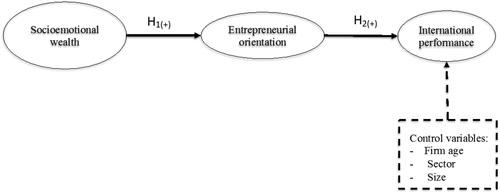

H1: Socioemotional wealth positively affects the entrepreneurial orientation of family firms.

2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation as an antecedent of international performance in family firms

Although research on internationalisation has advanced considerably in recent years, answering the question that arises as a result of the increasingly global and competitive environment where companies operate remains a challenge (Werner, Citation2002). Internationalisation allows companies to grow and survive in the long term (Alayo, Maseda, Iturralde, & Arzubiaga, Citation2019). Accordingly, entrepreneurial orientation can be conceived as a powerful construct that explains how companies face an ever-changing environment (Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, Citation2018), representing a key element of their internationalisation process (Alayo et al., Citation2019; Javalgi & Todd, Citation2011) and a pre-requisite for survival in highly competitive environments (Jaskiewicz et al., Citation2015). Entrepreneurial orientation is a recurring, cross-cutting concept that can explain internationalisation (Baier-Fuentes, Hormiga, Miravitlles, & Blanco-Mesa, Citation2019).

The entrepreneurial orientation and internationalisation of family firms is determined by the interaction between the firm and the family (Kallmuenzer, Hora, et al., Citation2018). Entrepreneurial orientation enables identification, evaluation and exploitation of different market opportunities (Banalieva, Puffer, McCarthy, & Vaiman, Citation2018; Ferreira et al., Citation2018), even if the outcome is uncertain (Banalieva et al., Citation2018).

Studies have shown the existence of a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance (Barringer & Bluedorn, Citation1999; Covin & Slevin, Citation1989; Ferreira et al., Citation2018; Miller, Citation1983; Wiklund, Citation1999; Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2005; Zahra, Citation1991; Zahra & Covin, Citation1995). Therefore, entrepreneurial orientation is a valuable predictor of business success (Krauss, Frese, Friedrich, & Unger, Citation2005). The management literature offers different approaches to studying internationalisation. In recent years, the entrepreneurship approach has been an emerging force with a high explanatory power regarding the value creation processes of companies that do business beyond their domestic borders (Joardar & Wu, Citation2011; Jones & Coviello, Citation2005; Weerawardena, Mort, Liesch, & Knight, Citation2007). This focus gives rise to the concept of international entrepreneurial orientation, which offers a fresh, dynamic way to explain why companies internationalise (e.g. Freeman & Cavusgil, Citation2007; Sundqvist, Kyläheiko, Kuivalainen, & Cadogan, Citation2012). From this approach, many authors have analysed the influence of entrepreneurial orientation on the international performance of the company by considering that this internationalisation is in itself an act of entrepreneurship (Baier-Fuentes et al., Citation2019). Almost all of the authors who have conducted such research have reported that entrepreneurial orientation positively influences internationalisation (e.g. Balabanis & Katsikea, Citation2003; Dimitratos, Lioukas, & Carter, Citation2004; Etchebarne, Geldres, & García-Cruz, Citation2010; Godwin Ahimbisibwe & Abaho, Citation2013). Studies have highlighted the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and family firm internationalisation (Brouthers, Nakos, & Dimitratos, Citation2015; Calabrò, Campopiano, Basco, & Pukkal, Citation2017; Hernández-Perlines, Citation2018; Huang, Lo, Liu, & Tung, Citation2014; Liu, Citation2014; Tung, Lo, Chung, & Huang, Citation2014) by acquiring skills in an international setting (Ferreira et al., Citation2018). Based on these theoretical considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Entrepreneurial orientation positively influences the international performance of family companies.

The proposed conceptual model appears in .

3. Method

Following the literature review and the presentation of the corresponding hypotheses, we now present the research method.

3.1. Data

Data were obtained from a questionnaire sent by e-mail using Limesurvey v.2.5 to the highest-ranking executives of a sample of firms drawn from the records of the Spanish Family Firm Institute. The chosen firms were selected randomly. The questionnaire consisted of Likert-type items rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 5. The sample comprised 1,045 companies associated with the Spanish Family Firm Institute. In total, 106 responses were obtained, representing a response rate of 10.14%. The field work was performed between April and June 2017. gives details of the sample.

Table 1. Field work technical sheet.

We also performed retrospective analysis of the statistical power of the sample using Cohen’s (Citation1992) test in G*Power 3.1.9.2 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, Citation2009). The sample of family firms for this study had a statistical power of 0.9348, which was above the limit of 0.80 established by Cohen (Citation1992). This value means that significant relationships may be identified in the data (Sarstedt & Mooi, Citation2019).

3.2. Measurement of variables

3.2.1. Entrepreneurial orientation

To measure entrepreneurial orientation, we followed Miller’s (Citation1983) approach, which was later modified by Covin and Slevin (Citation1989) and Covin and Miller (Citation2014). This way of measuring entrepreneurial orientation allowed us to understand its theoretical nature (Covin & Wales, Citation2012). Specifically, we measured entrepreneurial orientation using three first-order composites of type a: innovation (three items), proactiveness (three items) and risk-taking (three items). Entrepreneurial orientation was conceived as a multidimensional composite (Covin, Green, & Slevin, Citation2006; Kallmuenzer, Strobl, & Peters, Citation2018; Lumpkin & Dess, Citation1996). This choice is justified because it has been the most widely used in the literature (Arzubiaga, Iturralde, Maseda, & Kotlar, Citation2018, Sciascia, Mazzola, & Chirico, Citation2013). Entrepreneurial orientation has been operationalised in different ways: as a second-order composite of type a (Arzubiaga et al., Citation2018; Covin & Wales, Citation2012) or as a second-order composite of type b (Hansen, Deitz, Tokman, Marino, & Weaver, Citation2011; Hernández-Perlines & Rung-Hoch, Citation2017). This way of measuring entrepreneurial orientation has already been used and validated in previous studies such as those by Kreiser, Marino, Kuratko, and Weaver (Citation2013), Wales, Gupta, and Mousa (Citation2013) and Yusuf (Citation2002).

3.2.2. Socioemotional wealth

In this study, socioemotional wealth was measured using 27 items divided into the following dimensions as per the indications of Berrone et al. (Citation2012): family control and influence (six items), identification of family members with the company (six items), binding social ties (five items), emotional attachment of family members (six items) and renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession (four items). Socioemotional wealth was conceived using a multidimensional approach, in line with the studies by Filser, De Massis, Gast, Kraus, and Niemand (Citation2018) and Gast et al. (Citation2018), bringing together these multiple dimensions to present socioemotional wealth as a whole (Fitz-Koch & Nordqvist, Citation2017; Li & Daspit, Citation2016). Thus, socioemotional wealth was operationalised as a second-order composite of type b.

3.2.3. International performance

We measured international performance using a multi-item scale based on export intensity, which has been used as a measure of international performance by authors such as Zahra, Neubaum, and Huse (Citation1997) and Morgan, Kaleka, and Katsikeas (Citation2004). We also considered perceived satisfaction with export performance, which has been used by authors such as Balabanis and Katsikea (Citation2003), Cavusgil and Zou (Citation1994), Dimitratos et al. (Citation2004) and Zahra et al. (Citation1997). Both variables were measured on 5-point Likert scales. The third item used to measure international performance referred to export performance and has been used by authors such as and Ibeh (Citation2003), Morgan et al. (Citation2004) and Zahra et al. (Citation1997).

3.2.4. Control variables

Size (number of employees), age (number of years since establishment) and the main sector of the family firm were used as control variables. These control variables have appeared on a recurring basis in studies of family businesses (Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, Citation2005).

4. Results

To analyse the results and test the hypotheses, we performed partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.2.8 software (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, Citation2015). We used PLS-SEM because it enabled estimation of a complex model with second-order composites (Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, & Ringle, Citation2018). We were therefore able to deduce certain managerial implications (Hair, Sarstedt, & Ringle, Citation2019), which, in this case, relate to family firm internationalisation (Richter, Sinkovics, Ringle, & Schlägel, Citation2016). Data were obtained from a questionnaire sent by e-mail to the CEOs of family firms associated with the Spanish Family Firm Institute. The questionnaire was completed between April and June 2017. The process yielded useable data from 106 family companies.

To secure that the proposed measurement scales were valid and reliable, the two steps proposed by Barclay, Higgins, and Thompson (Citation1995) and Hair Jr, Sarstedt, Ringle, and Gudergan (Citation2017) were followed. The first consisted of assessing the measurement model, and the second consisted of assessing the structural model.

4.1. Assessment of the measurement model

Following recommendations by Roldán and Sánchez-Franco (Citation2012) and Hair Jr et al. (Citation2017), the first step was to analyse the values of composite reliability. Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommend values greater than 0.7 for composite reliability (see ). The values observed in this analysis may be described as good, according to Hair et al. (Citation2018), because they were between 0.7 and 0.9. In addition, they did not present problems of redundancy because in no case did they exceed 0.95 (Diamantopoulos, Sarstedt, Fuchs, Wilczynski, & Kaiser, Citation2012; Drolet & Morrison, Citation2001).

Table 2. Correlation matrix, composite reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, ratio Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) and descriptive statistics.

The second step was to calculate Cronbach’s alpha. Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommend Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.7. As shows, the Cronbach’s alpha values for this study exceeded this recommended value. Additionally, we calculated a reliability measure that lies between the two previous extreme values (composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha). This measure is rho A, proposed by Dijkstra and Henseler (Citation2015), which should be greater than 0.7 (Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015) and should lie between the values of composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha (Hair et al., Citation2018). The values for this study met these criteria (see ).

The third step, to assess convergent validity, was to calculate the average variance extracted (AVE). Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) recommend a value greater than 0.5 for the AVE. In our case, this condition was met (see ).

The fourth step was to check discriminant validity by confirming that the correlations between each pair of constructs did not exceed the value of the square root of the AVE of each construct and by examining the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) for composites of type a (see ). For discriminant validity to hold, HTMT values must be less than 0.85 (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Citation2015). As shows, the conditions for discriminant validity were met because the values did not exceed the established threshold.

4.2. Structural model analysis

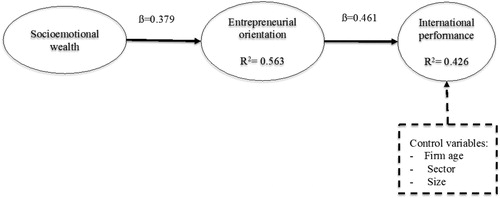

After confirming the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model, the hypotheses were tested by observing the path coefficient values and their significance (applying the bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 sub-samples). The results confirm that socioemotional wealth is a positive antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation, with socioemotional wealth explaining 56.3% of the variance of entrepreneurial orientation. Therefore, the results show that the explanatory power of socioemotional wealth to explain entrepreneurial orientation is moderate (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Citation2011). This finding implies that if family firms want to improve their entrepreneurial orientation, they must enhance their socioemotional wealth (see and ). Entrepreneurial orientation in turn exerts a positive influence on the international performance of family firms, explaining 42.6% of the variance. This result implies that family firms that wish to improve their international performance should consider their entrepreneurial orientation.

Table 3. Structural model.

No control variable had a significant influence on international performance. All path coefficients were less than 0.2 and were non-significant (see ).

Table 4. Control variable.

To complete the structural model analysis, we calculated the goodness of fit using the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). The proposed model had an SRMR value of 0.071, which is lower than the maximum recommended by Henseler et al. (Citation2015) of 0.085. Therefore, the model had a good fit to the data (Henseler, Hubona, & Ray, Citation2016).

5. Conclusions

The first conclusion relates to the composites used in the study and is therefore methodological. The use of PLS-SEM showed that socioemotional wealth, entrepreneurial orientation and international performance have suitable reliability and validity values (Henseler et al., Citation2016). Thus, all three composites used in this research were correctly measured as second-order composites. These results are consistent with previous studies (Hernández-Perlines, Citation2018; Hernández-Perlines et al., Citation2019; Llanos-Contreras & Santos, Citation2018).

The second conclusion is that entrepreneurial orientation has a positive significant effect on the international performance of family firms. The results show that entrepreneurial orientation explains 42.6% of the variance of international performance. Therefore, family firm internationalisation is determined by innovation, proactiveness and risk-taking. The results indicate that these three aspects together encourage family firms to internationalise (Hernández-Perlines, Citation2018).

The third conclusion is that socioemotional wealth positively and significantly affects the entrepreneurial orientation of family firms, explaining 56.3% of its variance. The results thereby corroborate Berrone et al. (Citation2012) FIBER model and its influence on the multidimensional composite of entrepreneurial orientation (Hernández-Perlines et al., Citation2019).

These findings indicate that socioemotional wealth is an antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation and that this entrepreneurial orientation in turn influences the international performance of family firms. If the effect of socioemotional wealth were not considered, then entrepreneurial orientation would explain only 34.2% of the international performance of family firms. In short, for family firms to improve their internationalisation through entrepreneurial orientation, they need socioemotional wealth. This study shows the indirect effect of socioemotional wealth on the international performance of family firms.

The first major limitation of this study is the use of a single informant for data collection. We tried to overcome this limitation by following the recommendations by Rong and Wilkinson (Citation2011), Woodside (Citation2013) and Woodside, Prentice, and Larsen (Citation2015). Accordingly, we contacted the highest-ranking executive of each firm (Dal Zotto & Van Kranenburg, Citation2008). Also, following Torchiano, Tomassetti, Ricca, Tiso, and Reggio’s (Citation2013) suggestions, a computerised process was used to send the surveys. In the e-mail sent to respondents, a cover letter was included explaining the study’s aims, soliciting participation and providing a contact e-mail address. Also, a reminder was sent to recipients who had not completed the questionnaire. The second limitation relates to the sample, which comprised companies associated with the Spanish Family Firm Institute. To overcome this limitation, we recommend using other databases such as SABI (Iberian Balance Sheets Analysis).

Regarding future research, we would underscore the need to perform longitudinal studies to analyse these effects over time (Cennamo et al., Citation2012). We encourage studies that compare results across countries using the same measurement scales to check whether differences arise depending on the context of the analysis. Another line of research in the future is to analyse the influence of human capital as a long-term generator of competitive advantage (Vargas, Lloria, & Roig-Dobón, Citation2016). It would also be of interest to analyse the effect of the interaction of different structures of goals and corporate governance (Chrisman & Patel, Citation2012).

From a methodological perspective, we propose conducting studies that combine qualitative and quantitative techniques to improve our understanding of the proposed models (Llanos-Contreras & Santos, Citation2018). It would also be of interest to perform studies in the future that consider the individual characteristics and personality traits of the family entrepreneurs (Franco & Prata, Citation2019) or the characteristics of the family firms themselves (Baier-Fuentes et al., Citation2019). Finally, we encourage scholars to examine the effects of gender, generation and non-family board members (Ferreira et al., Citation2018; Samara & Berbegal-Mirabent, Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alayo, M., Maseda, A., Iturralde, T., & Arzubiaga, U. (2019). Internationalization and entrepreneurial orientation of family SMEs: The influence of the family character. International Business Review, 28(1), 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.06.003

- Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., & Llanos-Contreras, O. (2019). Family business performance in a post-disaster scenario: The influence of socioemotional wealth importance and entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Research, 101, 492–498. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.057

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding‐family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1327.

- Arzubiaga, U., Iturralde, T., Maseda, M., & Kotlar, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in family SMEs: The moderating effects of family, women, and strategic involvement in the board of directors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 217–244. doi:10.1007/s11365-017-0473-4

- Astrachan, J. H., & Jaskiewicz, P. (2008). Emotional returns and emotional costs in privately held family businesses: Advancing traditional business valuation. Family Business Review, 21(2), 139–149. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00115.x

- Astrachan, J. H., & Shanker, M. C. (2003). Family businesses’ contribution to the US economy: A closer look. Family Business Review, 16(3), 211–219. doi:10.1177/08944865030160030601

- Autio, E., Sapienza, H. J., & Almeida, J. G. (2000). Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 909–924. doi:10.2307/1556419

- Baier-Fuentes, H., Hormiga, E., Miravitlles, P., & Blanco-Mesa, F. (2019). International entrepreneurship: A critical review of the research field. European Journal of International Management, 13(3), 381–412. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2019.10018148

- Balabanis, G. I., & Katsikea, E. S. (2003). Being an entrepreneurial exporter: Does it pay? International Business Review, 12(2), 233–252. doi:10.1016/S0969-5931(02)00098-7

- Banalieva, E. R., Puffer, S. M., McCarthy, D. J., & Vaiman, V. (2018). The impact of communist imprint prevalence on the risk-taking propensity of successful Russian entrepreneurs. European Journal of International Management, 12(1/2), 158–190. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2018.089032

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2, 285–309.

- Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. doi:10.5465/amr.2008.31193166

- Barringer, B. R., & Bluedorn, A. C. (1999). The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 421–444. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199905)20:5<421::AID-SMJ30>3.0.CO;2-O

- Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279. doi:10.1177/0894486511435355

- Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113. doi:10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82

- Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance, and the moderating role of strategic alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1161–1187. doi:10.1111/etap.12101

- Calabrò, A., Campopiano, G., Basco, R., & Pukall, T. (2017). Governance structure and internationalization of family-controlled firms: The mediating role of international entrepreneurial orientation. European Management Journal, 35(2), 238–248. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2016.04.007

- Casillas, J. C., & Moreno, A. M. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth: The moderating role of family involvement. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22(3–4), 265–291. doi:10.1080/08985621003726135

- Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy-performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 1–21. doi:10.2307/1252247

- Cennamo, C., Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family-controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1153–1173. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00543.x

- Chang, E. P., Memili, E., Chrisman, J. J., Kellermanns, F. W., & Chua, J. H. (2009). Family social capital, venture preparedness, and start-up decisions: A study of Hispanic entrepreneurs in New England. Family Business Review, 22(3), 279–292. doi:10.1177/0894486509332327

- Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Sharma, P. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 555–576. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00098.x

- Chrisman, J. J., & Patel, P. (2012). Variations in R&D investment in family and non-family firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 976–997.

- Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & De Massis, A. (2015). A closer look at socioemotional wealth: Its flows, stocks, and prospects for moving forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 173–182. doi:10.1111/etap.12155

- Ciravegna, L., Majano, S. B., & Zhan, G. (2014). The inception of internationalization of small and medium enterprises: The role of activeness and networks. Journal of Business Research, 67(6), 1081–1089. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.06.002

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Corona, J., & Del Sol, I. (2016). La Empresa Familiar en España (2015). Barcelona: Instituto de la Empresa Familiar. Retrieved from https://www.iefamiliar.com/upload/documentos/ubhiccx9o8nnzc7i.Pdf.

- Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. doi:10.1002/smj.4250100107

- Covin, J. G., & Miller, D. (2014). International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 11–44. doi:10.1111/etap.12027

- Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00432.x

- Covin, J. G., Green, K. M., & Slevin, D. P. (2006). Strategic process effects on the entrepreneurial orientation: Sales growth rate relationships. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 57–81. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00110.x

- Cruz, C., & Nordqvist, M. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: A generational perspective. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 33–49. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9265-8

- Cruz, C., Justo, R., & De Castro, J. O. (2012). Does family employment enhance MSEs performance? Integrating socioemotional wealth and family embeddedness perspectives. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 62–76. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.002

- Dal Zotto, C., & Van Kranenburg, H. (2008). Management and innovation in the media industry. Cheltenhan, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Davis, J. A., Pitts, E. L., & Cormier, K. (2000). Challenges facing family companies in the Gulf Region. Family Business Review, 13(3), 217–238. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00217.x

- Debicki, B. J., Kellermanns, F. W., Chrisman, J. J., Pearson, A. W., & Spencer, B. A. (2016). Development of a socioemotional wealth importance (SEWi) scale for family firm research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(1), 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.01.002

- Delmas, M. A., & Gergaud, O. (2014). Sustainable certification for future generations: The case of family business. Family Business Review, 27(3), 228–243. doi:10.1177/0894486514538651

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multiitem and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. doi:10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Dimitratos, P., Lioukas, S., & Carter, S. (2004). The relationship between entrepreneurship and international performance: The importance of domestic environment. International Business Review, 13(1), 19–41. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2003.08.001

- Drolet, A. L., & Morrison, D. G. (2001). Do we really need multiple-item measures in service research? Journal of Service Research, 3(3), 196–204. doi:10.1177/109467050133001

- Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Sarathy, R. (2008). Resource configuration in family firms: Linking resources, strategic planning and technological opportunities to performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 26–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00717.x

- Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Zellweger, T. M. (2012). Exploring the entrepreneurial behaviour of family firms: Does the stewardship perspective explain differences? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 347–367. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00402.x

- Etchebarne, M. S., Geldres, V. V., & García-Cruz, R. (2010). El impacto de la orientación emprendedora en el desempeño exportador de la firma. ESIC Market Economic and Business Journal, 137, 165–220.

- Fan, J. P., Wei, K. C., & Xu, X. (2011). Corporate finance and governance in emerging markets: A selective review and an agenda for future research. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(2), 207–214. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.12.001

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Ortiz, M. P. (2018). How agents, resources and capabilities mediate the effect of corporate entrepreneurship on multinational firms’ performance. European J. of International Management, 12(3), 255–277.

- Filser, M., De Massis, A., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Niemand, T. (2018). Tracing the roots of innovativeness in family SMEs: The effect of family functionality and socioemotional wealth. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(4), 609–628. doi:10.1111/jpim.12433

- Fitz-Koch, S., & Nordqvist, M. (2017). The reciprocal relationship of innovation capabilities and socioemotional wealth in a family firm. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(4), 547–570. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12343

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312

- Franco, M., & Prata, M. (2019). Influence of the individual characteristics and personality traits of the founder on the performance of family SMEs. European Journal of International Management, 13(1), 41–68. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2019.096498

- Freeman, S., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2007). Toward a typology of commitment states among managers of born-global firms: A study of accelerated internationalization. Journal of International Marketing, 15(4), 1–40. doi:10.1509/jimk.15.4.1

- Gast, J., Filser, M., Rigtering, J. P. C., Harms, R., Kraus, S., & Chang, M. (2018). Socioemotional wealth and innovativeness in small- and medium-sized family enterprises: A configuration approach. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 53–67. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12389

- Gedajlovic, E., Carney, M., Chrisman, J. J., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2012). The adolescence of family firm research taking stock and planning for the future. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1010–1037. doi:10.1177/0149206311429990

- Glover, J. L., & Reay, T. (2015). Sustaining the family business with minimal financial rewards: How do family farms continue? Family Business Review, 28(2), 163–177. doi:10.1177/0894486513511814

- Godwin Ahimbisibwe, M., & Abaho, E. (2013). Export entrepreneurial orientation and export performance of SMEs in Uganda. Global Advanced Research Journal of Management and Business Studies, 2(1), 056–062.

- Goel, S., Voordeckers, W., van Gils, A., & van den Heuvel, J. (2013). CEO’s empathy and salience of socioemotional wealth in family SMEs-The moderating role of external directors. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3–4), 111–134. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.710262

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653–707. doi:10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Nunez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137. doi:10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

- Gómez‐Mejía, L. R., Makri, M., & Kintana, M. L. (2010). Diversification decisions in family‐controlled firms. Journal of Management Studies, 47(2), 223–252. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00889.x

- Goss, D. (2005). Schumpeter’s legacy? Interaction and emotions in the sociology of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(2), 205–218. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00077.x

- Habbershon, T. G., & Pistrui, J. (2002). Enterprising families domain: Family-influenced ownership groups in pursuit of intergenerational wealth. Family Business Review, 15(3), 223–237. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00223.x

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–151. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2018). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(2), 2–24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018–0203

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. doi:10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. London: Sage Publications.

- Hansen, J. D., Deitz, G. D., Tokman, M., Marino, L. D., & Weaver, K. M. (2011). Cross-national invariance of the entrepreneurial orientation scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 61–78. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.05.003

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. doi:10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hernández-Linares, R., & López-Fernández, M. C. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and the family firm: Mapping the field and tracing a path for future research. Family Business Review, 31(3), 318–351. doi:10.1177/0894486518781940

- Hernández-Perlines, F. (2018). Moderating effect of absorptive capacity on the entrepreneurial orientation of international performance of family businesses. Journal of Family Business Management, 8(1), 58–74. doi:10.1108/JFBM-10-2017-0035

- Hernández-Perlines, F., & Rung-Hoch, N. (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Sustainability, 9(7), 1212. doi:10.3390/su9071212

- Hernández‐Perlines, F., Moreno‐García, J., & Yáñez‐Araque, B. (2017). Family firm performance: The influence of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity. Psychology & Marketing, 34(11), 1057–1068.

- Hernández-Perlines, F., Moreno-García, J., & Yáñez-Araque, B. (2019). The influence of socioemotional wealth in the entrepreneurial orientation of family businesses. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 523–544. doi:10.1007/s11365-019-00561-0

- Hiebl, M. R. W., Quinn, M., Craig, J. B., & Moores, K. (2018). Management control in family firms: A guest editorial. Journal of Management Control, 28(4), 377–381. doi:10.1007/s00187-018-0260-6

- Huang, K. P., Lo, S. C., Liu, C. M., & Tung, J. (2014). Internationalization of family business: The effect of ownership and generation involvement. The Anthropologist, 17(3), 757–767. doi:10.1080/09720073.2014.11891490

- Ibeh, K. I. (2003). Toward a contingency framework of export entrepreneurship: Conceptualisations and empirical evidence. Small Business Economics, 20(1), 49–68.

- Jack, S. L. (2005). The role use and activation of strong and weak network ties: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 42(6), 1233–1259. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00540.x

- Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 29–49. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.001

- Javalgi, R. G., & Todd, P. R. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation, management commitment, and human capital: The internationalization of SMEs in India. Journal of Business Research, 64(9), 1004–1010. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.024

- Joardar, A., & Wu, S. (2011). Examining the dual forces of individual entrepreneurial orientation and liability of foreignness on international entrepreneurs. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L'administration, 28(3), 328–340. doi:10.1002/cjas.203

- Jones, M. V., & Coviello, N. E. (2005). Internationalization: Conceptualizing an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 284–303. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400138

- Kabbach de Castro, L. R., Crespi-Cladera, R., & Aguilera, R. V. (2016). An organizational economics approach on the pursuit of socioemotional and financial wealth in family firms: Are these competing or complementary objectives? Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 14(3), 267–278. doi:10.1108/MRJIAM-07-2016-0677

- Kallmuenzer, A., Hora, W., & Peters, M. (2018). Strategic decision-making in family firms: An explorative study. European J. Of International Management, 12(5), 6), 655–675. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2018.10014765

- Kallmuenzer, A., Strobl, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Tweaking the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in family firms: The effect of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Review of Managerial Science, 12(4), 855–883. doi:10.1007/s11846-017-0231-6

- Kellermanns, F. W., & Eddleston, K. A. (2006). Corporate entrepreneurship in family firms: A family perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(6), 809–830. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00153.x

- Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, K. A., & Zellweger, T. M. (2012). Extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: A look at the dark side. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1175–1182. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00544.x

- Khayesi, J. N., George, G., & Antonakis, J. (2014). Kinship in entrepreneur networks: Performance effects of resource assembly in Africa. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(6), 1323–1342. doi:10.1111/etap.12127

- Krauss, S. I., Frese, M., Friedrich, C., & Unger, J. M. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation: A psychological model of success among southern African small business owners. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14(3), 315–344. doi:10.1080/13594320500170227

- Kreiser, P. M., Marino, L. D., Kuratko, D. F., & Weaver, K. M. (2013). Disaggregating entrepreneurial orientation: the non-linear impact of innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking on SME performance. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 273–291. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9460-x

- Le Breton‐Miller, I., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 305–328. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00047.x

- Lee, T., & Chu, W. (2017). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: Influence of family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(4), 213–223. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.09.002

- Li, Z., & Daspit, J. J. (2016). Understanding family firm innovation heterogeneity: a typology of family governance and socioemotional wealth intentions. Journal of Family Business Management, 6 (2), 103–121. doi:10.1108/JFBM-02-2015-0010

- Liu, C. M. (2014). Internationalization of family firm: The role of entrepreneurial orientation, ownership and generational involvement. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 47, 180–191.

- Llanos-Contreras, O., A.-D., & Santos, M. A. (2018). Exploring the asymmetric influence of socioemotional wealth priorities on entrepreneurial behaviour in family businesses. European Journal of International Management, 12(5/6), 576–595.

- López-Fernández, M. C., Serrano-Bedia, A. M., & Pérez-Pérez, M. (2016). Entrepreneurship and family firm research: A bibliometric analysis of an emerging field. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), 622–639.

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21, 135–1172.

- Lumpkin, G. T., Brigham, K. H., & Moss, T. W. (2010). Long-term orientation: Implications for the entrepreneurial orientation and performance of family businesses. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22, 241–264.

- Makadok, R. (2001). Toward a synthesis of the resource‐based and dynamic‐capability views of rent creation. Strategic Management Journal, 22(5), 387–401. doi:10.1002/smj.158

- Martínez-Alonso, R., Martínez-Romero, M. J., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. A. (2018). Technological innovation and socioemotional wealth in family firm research: Literature review and proposal of a conceptual framework. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 16(3), 270–301.

- Martínez-Romero, M. J., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. A. (2016). SEW: Temporal trajectory and controversial issues. European Journal of Family Business, 6(1), 1–9.

- Martínez-Romero, M. J., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. A. (2017). Socioemotional wealth’s implications in the calculus of the minimum rate of return required by family businesses’ owners. Review of Managerial Science, 11(1), 95–118.

- Masulis, R. W., Pham, P. K., & Zein, J. (2011). Family business groups around the world: Financing advantages, control motivations, and organizational choices. Review of Financial Studies, 24(11), 3556–3600.

- Matthews, C. H., Hechavarria, D., & Schenkel, M. T. (2012). Family business: A global perspective from the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. In A. L. Carsrud & M. Brännback (Eds.), Understanding Family Businesses (pp. 9–26). New York, NY: Springer.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2014). Deconstructing socioemotional wealth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(4), 713–720.

- Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

- Miller, D., Le Breton‐Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non‐family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 51–78.

- Morgan, N. A., Kaleka, A., & Katsikeas, C. S. (2004). Antecedents of export venture performance: A theoretical model and empirical assessment. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 90–108.

- Naldi, L., Cennamo, C., Corbetta, G., & Gomez‐Mejia, L. (2013). Preserving socioemotional wealth in family firms: Asset or liability? The moderating role of business context. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1341–1360.

- Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 33–47.

- Nordqvist, M., & Melin, L. (2010). Entrepreneurial families and family firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22, 211–239.

- Pejic Bach, M., Aleksic, A., & Merkac-Skok, M. (2018). Examining determinants of entrepreneurial intentions in Slovenia: applying the theory of planned behaviour and an innovative cognitive style. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1453–1471.

- Poza, E. J., & Daugherty, M. S. (2013). Family business (4th ed.). Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.

- Prahalad, C., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 5(6), 79–91.

- Richter, N. F., Sinkovics, R. R., Ringle, C. M., & Schlägel, C. (2016). A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 376–404. doi:10.1108/IMR-04-2014-0148

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). Smart PLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Retrieved from https://www.smartpls.com

- Rizvi, W. H., & Oney, E. (2018). The influence of emotional confidence on brand attitude: Using brand belief as mediating variable. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 158–170.

- Roldán, J. L., & Sánchez-Franco, M. J. (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In M. Mora, O. Gelman, A. Steenkamp, & M. Raisinghani (Eds.), Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Rong, B., & Wilkinson, I. F. (2011). What do managers’ survey responses mean and what affects them? The case of market orientation and firm performance. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 19(3), 137–147. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.04.001

- Samara, G., & Berbegal-Mirabent, J. (2018). Independent Directors and Family Firm Performance: Does One Size Fit All? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 149–172. doi:10.1007/s11365-017-0455-6

- Sapienza, H. J., Autio, E., George, G., & Zahra, S. A. (2006). A capabilities perspective on the effects of early internationalization on firm survival and growth. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 914–933. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.22527465

- Sarstedt, M., & Mooi, E. A. (2019). A concise guide to market research: The process, data, and methods using IBM SPSS statistics. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Schepers, J., Voordeckers, W., Steijvers, T., & Laveren, E. (2014). The entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship in private family firms: The moderating role of socioemotional wealth. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 39–55. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9533-5

- Sciascia, S., Mazzola, P., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2014). Family management and profitability in private family-owned firms: Introducing generational stage and the socioemotional wealth perspective. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), 131–137. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2014.03.001

- Sciascia, S., Mazzola, P., & Chirico, F. (2013). Generational involvement in the top management team of family firms: Exploring nonlinear effects on entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(1), 69–85. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00528.x

- Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Gersick, K. E. (2012). 25 years of family business review: Reflections on the past and perspectives for the future. Family Business Review, 25(1), 5–15. doi:10.1177/0894486512437626

- Sundqvist, S., Kyläheiko, K., Kuivalainen, O., & Cadogan, J. W. (2012). Kirznerian and Schumpeterian entrepreneurial-oriented behavior in turbulent export markets. International Marketing Review, 29(2), 203–219. doi:10.1108/02651331211216989

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Torchiano, M., Tomassetti, F., Ricca, F., Tiso, A., & Reggio, G. (2013). Relevance, benefits, and problems of software modelling and model driven techniques: A survey in the Italian industry. Journal of Systems and Software, 86(8), 2110–2126. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.084

- Tung, J., Lo, S. C., Chung, T., & Huang, K. P. (2014). Family business internationalisation: The role of entrepreneurship and generation involvement. The Anthropologist, 17(3), 811–822. doi:10.1080/09720073.2014.11891495

- Vargas, N., Lloria, M. B., & Roig-Dobón, S. (2016). Main drivers of human capital, learning and performance. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(5), 961–978. doi:10.1007/s10961-016-9483-6

- Vandemaele, S., & Vancauteren, M. (2015). Nonfinancial goals, governance, and dividend payout in private family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 166–182. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12063

- Wales, W. J., Gupta, V. K., & Mousa, F. T. (2013). Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 31(4), 357–383. doi:10.1177/0266242611418261

- Wang, D., Wang, L., & Chen, L. (2018). Unlocking the influence of family business exposure on entrepreneurial intentions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(4), 951–974. doi:10.1007/s11365-017-0475-2

- Weerawardena, J., Mort, G. S., Liesch, P. W., & Knight, G. (2007). Conceptualizing accelerated internationalization in the born global firm: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 294–306. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2007.04.004

- Werner, S. (2002). Recent developments in international management research: A review of 20 top management journals. Journal of Management, 28(3), 277–305. doi:10.1177/014920630202800303

- Wiklund, J. (1999). The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation—Performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(1), 37–48. doi:10.1177/104225879902400103

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001

- Woodside, A. G. (2013). Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. Journal of Business Research, 66(4), 463–472. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.12.021

- Woodside, A. G., Prentice, C., & Larsen, A. (2015). Revisiting problem gamblers’ harsh gaze on casino services: Applying complexity theory to identify exceptional customers. Psychology & Marketing, 32(1), 65–77. doi:10.1002/mar.20763

- Yusuf, A. (2002). Environmental uncertainty, the entrepreneurial orientation of business ventures and performance. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 12(3/4), 83–103. doi:10.1108/eb047454

- Zahra, S. A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(4), 259–285. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(91)90019-A

- Zahra, S. A. (2005). Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Family Business Review, 18(1), 23–40. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00028.x

- Zahra, S. A., & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 43–58. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(94)00004-E

- Zahra, S. A., Hayton, J. C., & Salvato, C. (2004). Entrepreneurship in family vs. non-family firms: A resource-based analysis of the effect of organizational culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 363–381. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00051.x

- Zahra, S. A., Neubaum, D. O., & Huse, M. (1997). The effect of the environment on export performance among telecommunications new ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(1), 25–46. doi:10.1177/104225879702200102

- Zellweger, T. M., & Astrachan, J. H. (2008). On the emotional value of owning a firm. Family Business Review, 21(4), 347–363.

- Zellweger, T. M., Kellermanns, F. W., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. H. (2012). Family control and family firm valuation by family CEOs: The importance of intentions for transgenerational control. Organization Science, 23(3), 851–868. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0665

- Zellweger, T. M., & Nason, R. S. (2008). A stakeholder perspective on family firm performance. Family Business Review, 21(3), 203–216. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00123.x

- Zellweger, T. M., Nason, R. S., & Nordqvist, M. (2012). From longevity of firms to intergenerational entrepreneurship of families introducing family entrepreneurial orientation. Family Business Review, 25(2), 136–155. doi:10.1177/0894486511423531