Abstract

This study determines the influence of the main Spanish think tanks in the national and international media during the period from 2004 to 2018. We use quantitative analysis on the published contents (from Factiva®) of the main Spanish think tanks between 1st January 2004 and 31st December 2018 in national and international media. The results suggest that the impact of think tanks has increased since the crisis period and has remained constant thereafter, thereby confirming the relevant role of think tanks in public opinion. Moreover, during the process of economic policy design, there has been a significant increase in the hegemony of a few think tanks’ influence in media debates.

1. Introduction

Think tanks, also known as factory of ideas, (Abelson, Citation2009), are political actors who, based on research and analysis, aim to influence and advise the political elite and society in general (Mac Gann & Weaver, Citation2000; Misztal, Citation2012; Stone, Citation2004). Moreover, their role is to transform political debates (McGann, Citation2007), which is why they stand out as essential actors in the political environment (Barani & Sciortino, Citation2011), and their importance has been growing steadily in recent decades (Pautz, Citation2010). Based on the different contexts and the heterogeneous nature of these organisations, various terms have been used to refer to them, such as research centres, idea laboratories (Castillo-Esparcia, Guerra-Heredia, & Almansa-Martínez, Citation2017), or even defence coalitions (Sherrington, Citation2000).

The term ‘think tank’ (TT) was coined after the World War II, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon countries and in the United States (Mac Gann & Weaver, Citation2000; Xifra, Citation2005). TTs became relevant in the 1970s in the United States when they decided to support political parties with a conservative ideology to control academic debates and the media that were influenced by other trends at that time (Saura, Citation2015). The role of TTs as political figures is based on ‘the formulation and promotion of ideas as a dominant paradigm’ (Montobbio, Citation2013, p. 18), since they are also prominent interlocutors, and mediators of ideas and thus, introducers of debates in the public agenda (McGann, Viden, & Rafferty, Citation2014).

The areas of research currently covered by TTs include policies such as economic, educational, and energy, as well as, health, science and technology, social, defence and national security, environment, and international relations, among others (McGann, Citation2018).

TTs play an essential role in the United States, and their expansion in Europe has been very significant in recent years (Lalueza & Girona, Citation2016). Since the end of the 20th century, the number of TTs has increased in Spain due to the country's growing participation in international affairs (Parrilla, Almiron, & Xifra, Citation2016). They have consolidated themselves as new political actors for advice, effective control, and influence in political decision-making (Saura, Citation2015), with a greater social, political, and communicative presence (Castillo-Esparcia et al., Citation2017). According to McGann (Citation2018), Spain had a total of 63 TTs registered in 2017, ranking 21st in the list of countries with the largest number of such organisations. Out of the 63 TTs, eight are among the most influential in Western Europe and three stand out as the most relevant in the field of national economic policy (McGann, Citation2018).

The results of the research indicate that there are very few TTs with impact in the media because direct contact with relevant political actors prevails in most cases (Lalueza & Girona, Citation2016). This is due to the fact that, in certain situations—like an economic crisis— the need to hastily implement certain policies means TTs are driven to measures with more immediate results, such as lobbying strategies (Leeson, Ryan, & Williamson, Citation2012). Nevertheless, empirical investigations that analyse the real influence of TTs in media discourse are scarce (Rich & Weaver, Citation2000) and practically non-existent in Spain (Almiron, Citation2016; Lalueza & Girona, Citation2016).

Therefore, this study determines the influence of the main Spanish TTs from a quantitative viewpoint, in national and international media, during the period from 2004 to 2018. Their influence should be understood in terms of the visibility, coverage, or presence achieved by these organisations in the media. Their appearance in the media is linked to published studies, reports, and recommendations, as well as to the many experts who disseminate their studies. The media gathers the conclusions of the TT reports, as well as the interventions and articles of analysis and opinion signed by their affiliated experts.

In the analysed period, the following stages related to the economic cycle are distinguished as follows: growth stage (2004 to 2006), which coexisted with the appearance of the Spanish real estate bubble; stage of crisis (2007 to 2009), which includes the bursting of the housing bubble and the beginning of the economic crisis; adjustment and reform stage (2010 to 2012), which covers the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis and the associated adjustments and reforms; recovery stage (2013 to 2015), which includes the consolidation of the financial rescue process; and growth stage (2016 to 2018), which implies the return of the Spanish economy to the path of growth from its stable situation before the crisis.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. TTs and the mass media

There are several definitions of TTs, depending on the perspective used. The most well-known definition is the one put forward by Mac Gann and Weaver (Citation2000), where they interpret that TTs are ‘non-governmental, not-for-profit research organisations with substantial organisational autonomy from government and from societal interests such as firms, interest groups, and political parties’. For Rich (Citation2004), they are independent, non-profit organisations that—based on experience and ideas—try to influence the policy-making process. Meanwhile, Chuliá (Citation2018, p. 333) states that TTs are ‘private, non-profit organisations committed to transfer data and analysis on matters of public interest to society, in order to improve the conditions of information and knowledge through which politicians and citizens make their decisions’.

Although many TTs depend on one or several institutions (Arshed, Citation2017), the previous definitions reflect an idealised vision of these organisations as independent institutions that provide objective and neutral information to favour public debate (Shaw, Russell, Parsons, & Greenhalgh, Citation2015). However, the dependence of TTs rests on three causal pillars: political access in order to influence public debate, access to economic actors to obtain financial support, and access to the media to achieve visibility (Medvetz, Citation2008). Some authors add the academic factor to these pillars as a reputational element that sinks its roots into the prestige of research, although the commitment to academic rigor is subordinated to conflicts of political interest and funding (Parrilla et al., Citation2016).

Arshed (Citation2017) has evaluated the way in which the funding of TTs affects the ideology that they represent, as well as their research. Authors such as Mulgan (Citation2006, p. 149) point out that the ‘big business has come to see funding for think tanks as a more acceptable way to establish links with political parties than direct funding, while also using them to promote particular causes such as European integration and public-private partnerships’. Both the connection between research and politics, and the ability of TTs to produce knowledge are the origin of their public power (Wiarda, Citation2008). Moreover, TTs develop research and promote their findings as milestones worthy of widespread dissemination by the media (Posner, Citation2001). Thus, a fundamental function of TTs is to achieve broad coverage and to influence media discourse, which is their main strategy to leverage a political decision (Lalueza & Girona, Citation2016; Rich & Weaver, Citation2000) and to measure its effectiveness (Abelson, Citation2012).

According to Lalueza and Girona (Citation2016), one of the strategies used by Spanish TTs to expand their coverage in the media is by specialising in a specific topic to become a reference source in that field. In the context of the Spanish economy, this strategy is used by the Foundation for Applied Economics Studies (FEDEA) and the Savings Banks Foundation (FUNCAS). Moreover, in this same context, another strategy meant to obtain great visibility in the media is the proposal of a wide range of solutions to overcome the consequences of the economic crisis in the areas of employment, taxes, or pensions, among others; this is the strategy embraced by the Entrepreneurs Circle. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. TTs increased their presence in the media during the analysed period.

However, the influence of TTs on media discourse is also determined by the perception that the media might have of a dependent relationship between TTs and a political party, where the greater the dependence, the more likely it is for media influence to be lost (Lalueza & Girona, Citation2016).

Thus, several studies suggest that TTs have a potential influence on the climate of opinion, especially in the initial stages of the development of public policies (Castaño, Méndez, & Galindo, Citation2015) since they provide relevant information to advise governmental decision makers (Denham, Citation2005; Misztal, Citation2012). Nevertheless, although there are studies in which the real influence of TTs in the creation of public policies has not been demonstrated (Abelson, Citation2009), more recent analyses corroborate the essential role of TTs in the creation of consensus to favour financial deregulation and to create narratives that encourage austerity policies (Parrilla et al., Citation2016). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a. The presence of TTs in the media is inversely related to the economic cycle: the worse the performance of macroeconomic indicators is, the greater the presence of TTs in the media will be, and vice versa.

H2b. The evolution of the presence of TTs in the media is constant across phases and homogeneous among TTs.

There are also networks of relationships between TTs that determine the way they act (Sánchez & Miranda, Citation2014). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. The media publications of TTs that show greater impact capacity are correlated.

2.2. TTs and the economic crisis

The latest global economic crisis has motivated intense debates regarding its origin and the soundest solutions to overcome it. This type of recession—characterised by decreased GDP and high unemployment rates persistent in time—is common in the history of capitalism (Keynes, Citation1936; Kindleberger, Citation1986).

The origin of this serious economic crisis began in the mortgage sector in the United States. The tension that followed in the public debt markets of European countries caused problems of stability and solvency in the Spanish banking system (Bernardino & Carrasco, Citation2014).

The fact that this type of recession has a financial origin means that monetary policy responses have limited capacity beforehand and therefore, open a wider path for the recovery of the different components of aggregate demand which, in consequence, allows to increase staff recruitment and at the same time decrease unemployment rate (Christiano, Eichenbaum, & Rebelo, Citation2011; Eggertsson & Krugman, Citation2012). In any case, it is essential to determine the most appropriate combination of fiscal and monetary policies to better deal with these kinds of crises.

On the one hand, there are the supporters of positions based on ‘expansive austerity’, who point out that adjusting public budgets to control a country's finances can boost its economy (Alesina & Ardagna, Citation2010). On the other hand, there are the supporters of more Keynesian positions, who maintain that budget restriction policies can even be counterproductive (Blanchard & Leigh, Citation2013), especially in a monetary union environment such as the European Union (De Grauwe & Ji, Citation2013).

The situation can become even more complex when the deficit level reached by each bailed-out country brings about a new crisis, that of each country’s public debt (Laeven & Valencia, Citation2008; Reinhart & Rogoff, Citation2009), thus seriously hindering the implementation of fiscal stimulus policies. In these new recession scenarios, austerity policies can further aggravate the economic situation and further increase the countries' debt (Auerbach & Gorodnichenko, Citation2012).

Such is the complexity in adopting certain types of policies which international organisations of an economic and financial nature—like the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—have significantly advanced in their approaches. Specifically, for a long period of time prior to the financial crisis in the United States, the IMF believed that fiscal policies were not very effective in certain countries and situations (Heller, Citation2003).

The United States responded not only with fiscal but also with urgent and aggressive monetary measures to the crisis. The Federal Reserve decreased the interest rate by more than five per cent and, together with the adoption of fiscal stimulus policies, managed to return to the path of economic growth, meeting the objectives of increasing the employment rate and improving the country’s overall demand in a short period of time (Romer & Bernstein, Citation2009).

Meanwhile, the leaders responsible for community finances in the European Union chose structural reforms and strict austerity measures, out of the different types of policies they had in view, to overcome the economic crisis, consequently leading to the euro crisis (Parrilla et al., Citation2016). Policies began to order massive cuts in public spending in the countries at the periphery of the Eurozone, along with politically difficult reforms intended to make markets more efficient for future business and investment (Matthijs & McNamara, Citation2015). The most common reason for the implementation of these policies based on fiscal discipline and the flexibility of the labour market was that they were expected to considerably improve the economic situation (Matthijs, Citation2014). Thus, although the austerity policies proved not only inefficient from a financial perspective but also socially damaging ( Stiglitz, Citation2013a, Citation2013b ), several TTs of the centre-right political spectrum —spread in the European Union and especially in Germany—encouraged such policies (Plehwe, Neujeffski, & Krämer, Citation2018).

With the exception of Greece, the high public debt in the peripheral economies of the Eurozone was not due to out-of-control state spending, but rather due to the absorption of private losses by the countries themselves (Blyth, Citation2013). It was surprising that more effective alternative solutions to the problems of the euro were not adopted then, such as the implementation and joint issuance of a community debt instrument or Eurobonds, a proposal that was not very well-accepted in any case (Matthijs & McNamara, Citation2015). The cuts in public spending of the States were considered, in turn, as the best ‘medicine’ for the problems of the private sector (Blyth, Citation2013).

In the European Union, ‘the dominant analysis of the crisis was shaped by academics, think tanks, private and public sector actors, specifically German economists and powerful business and financial interests, whose ideas had long underwritten the euro’s institutional design at Maastricht and Amsterdam during the euro’s formative decade. Berlin, Frankfurt, and Brussels early on fashioned the crisis into a “normative” morality tale of Southern profligacy vs. Northern thrift’ (Matthijs & McNamara, Citation2015). Similarly, these approaches are in line with those of Plehwe et al. (Citation2018) and Parrilla et al. (Citation2016) that highlight the way in which ‘the elites, a coalition composed of governments, financial authorities, auditors, advisers and large corporations, basically managed to impose measures against the crisis worldwide that turned a problem of the private sector promoted by the elites into a public problem borne by the common citizen’. All these measures did not have the expected success and will likely never end up having it (Hall, Citation2014).

The effects of the crisis in Spain were felt intensely in 2008 (Bernardino & Carrasco, Citation2014). Despite being an important and strong economy in the European Union, characterised then by a low level of public debt, the very serious banking crisis affected Spain to a great extent due to the exposure of its financial system to the real estate bubble that had been generated years ago due to the European Union’s monetary policy of keeping interest rates very low for a long period of time.

This banking crisis caused major problems for the financing of the Spanish national debt in international financial markets in 2009. Being a Eurozone country, it did not have the autonomy to make monetary policy decisions and therefore, the Spanish government only had the option of adopting fiscal measures mainly through cuts in public spending and increases in tax collection. In this context, the European Central Bank (ECB) decided to intervene in the purchase of Spanish public debt in exchange for severe fiscal adjustments from the government (Romero, Citation2010). Finally, in June 2012, the Spanish government formally requested financial assistance (through a memorandum of understanding (MoU)) to recapitalise its banking sector, assuming a set of commitments regarding adjustment policies and reforms (Bernardino & Carrasco, Citation2014).

There are studies that show that the Spanish economic and financial TTs lacked autonomy to face the challenges posed during the 2008 to 2015 period (Parrilla et al., Citation2016). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a. The presence of TTs in international media increased over the analysed period.

H4b. The increase of the presence of TTs in international media was homogeneous among the different TTs throughout the analysed period.

In the same way, the presence of a close cooperation between political actors and financial leaders at an international level has been observed, proving that their arguments are coherent worldwide, which is usually the case when austerity policies have been agreed upon (Blyth, Citation2013). Meanwhile, as long as discourses are solid, they get greater coverage in the media, which fosters the creation and development of opinion states in the public debate (Davis, Citation2012). As such, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5. TTs with greater presence in national media achieved greater presence in international media throughout the analysed period.

H6. TTs with greater presence in the media increased the weight of their hegemony throughout the analysed period.

H7. TTs with a greater presence in media increased the weight of their national hegemony more than their international hegemony across the analysed period.

The variable used to accept or reject the hypotheses is the number of publications of the main Spanish TTs with media coverage during the analysed period (2004 to 2018).

3. Methodology

3.1. Stages of the analysed period

Our methodology considers several temporary milestones over a period of fifteen years from 2004 to 2018 and identifies the following stages.

(P1) Growth stage: this period includes the years between 2004 and 2006, and also the last years of the economic growth phase that coexisted with the appearance of the Spanish real estate bubble.

(P2) Crisis stage: this period lasts between 2007 and 2009 and represents the bursting of the real estate bubble and the beginning of the economic crisis.

(P3) Adjustment and reforms stage: this period covers the years between 2010 and 2012 and includes critical events such as the beginning of the sovereign debt crisis and also the associated adjustments and reforms in the Spanish economy. In this stage, the problems of the Spanish deficit and public debt continue, giving rise to the reform of Article 135 of the Spanish Constitution (Citation1978). Its new text guarantees absolute priority in public debt payment.

(P4) Recovery stage: this period includes the years between 2013 and 2015 and some critical incidents such as the consolidation of the financial rescue process, with the conversion of practically all the savings banks into banks and their absorption in the Spanish banking system through the intervention of the Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring (FROB). It also includes the subscription of the MoU, under the supervision of the troika formed by the ECB, the European Commission, and the IMF, and the beginning of the recovery of the Spanish economy taking place at this stage.

(P5) Growth stage: this period includes the years between 2016 and 2018 and is characterised by the consolidation of the effects of the reforms, as well as the return of the Spanish economy to the growth path of its stable situation before the crisis (2016 to 2018).

3.2. TTs analysed

To determine the TTs for this study, the ranking of the University of Pennsylvania that categorises this type of organisations, specifically, the 2017 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report (McGann, Citation2018), was used for the classification of TTs by geographical and research areas.

There are eight Spanish TTs that appear in the Top Think Tanks in Western Europe (TTT-WE), half of which are ranked in the first or second quartile. Besides this, three Spanish TTs are also included in the Top Think Tanks in Domestic economic Policy (TTT-DEP).

In addition, and based on Tello's study (2013) that includes 61 Spanish TTs, two organisations have been identified whose main field of activity is economics and finance, their presence in the media being similar or greater than in the case of the media indexed in the rankings based on McGann (Citation2018). Thus, the set of Spanish TTs analysed in this study is supplemented by the Savings Banks Foundation (FUNCAS) and the Entrepreneurs Circle.

The FUNCAS should be mentioned here as a special case as it is a TT managed by savings banks whose role in the studied period has important implications. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that savings banks played a major role in the restructuring of the financial system whose concentration was particularly drastic when savings banks underwent the process of conversion into banks (). On the other hand, the FUNCAS is a relevant TT due to the qualitative relevance of its reports and studies in the public sphere of the media, especially with regard to the financial impact that the bailout process represented for the FROB and ultimately, for the Spanish state. This case is confirmed by both the subscription of the MoU and the effects of the process of adjustment and reforms on the Spanish public debt.

Table 1. Structure of the Spanish banking system (number of entities).

shows the ten Spanish TTs included in this study, the acronym chosen to refer to them when a TT does not have one, and their absolute position and quartile in the TTT-DEP and TTT-WE rankings, based on McGann's formulation (2018).

Table 2. Spanish think tanks under study and their position in the ranking.

3.3. Data collection and measurement of variables

Factiva®—a search tool for information published in the media—was used to determine the media coverage of TTs. Factiva® belongs to Dow Jones & Company© and provides access to more than 33,000 premium and reputable sources worldwide (Factiva, Citation2019). In the case of Spain, Factiva® allows online access to 264 media outlets, including all national and regional newspapers in their paper and digital versions. Moreover, it tracks the information published by EFE and Europa Press agencies, among others.

Factiva® has extensive temporary coverage and advanced consultation systems and offers support to academic researchers and information management professionals. The Factiva® data search is based on personalisation, allowing source preselection. Previous studies in the areas of economic and financial information show the rigor of the results provided by Factiva (Griffin, Hirschey, & Kelly, Citation2011; Tetlock, Citation2007).

To objectify the impact of each of the 10 TTs analysed, the following Factiva® search protocol was followed:

The search was made with reference to title, summary, or news, using the full name of TTs with quotation marks, regardless of their acronyms, to avoid false positives. Most of the analysed TTs’ acronyms represent other terms that identify business associations, other types of organisations, or elements randomly involved in news, both in Spain and the rest of the world.

The search was carried out in all Spanish media, in any language, between 2004 and 2018, separating the results obtained in each of the stages (P1), (P2), (P3), (P4), and (P5).

The search was conducted following the same criteria specified in step (1) but in the case of the media worldwide, excluding the Spanish media, also separating the results obtained for each of the stages (P1) to (P5).

The results obtained in steps (2) and (3) for each of the TTs help determine the extent of internationalisation of the discourse in the case of the analysed TTs.

4. Results

The hypotheses were verified or rejected depending on the results obtained.

H1. TTs increased their coverage in the media during the analysed period.

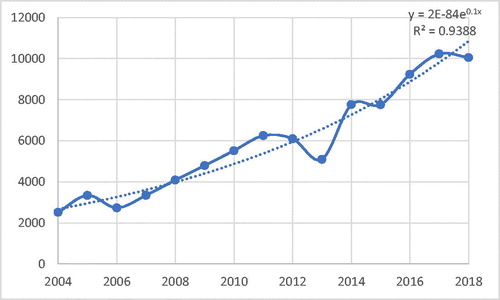

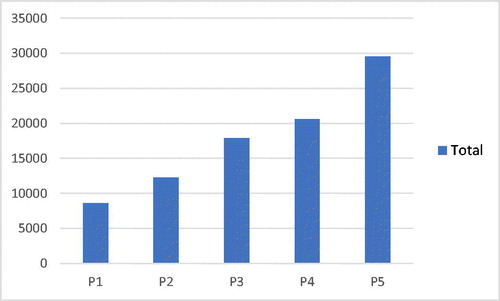

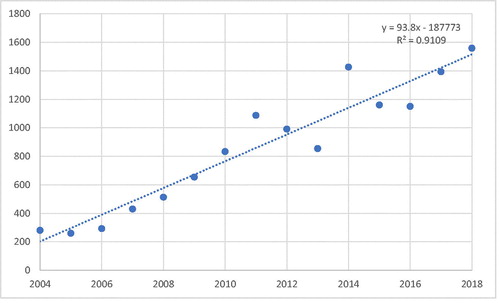

The analysis of the news published in the media shows an upward trend for the overall number of TTs under study during the considered period (R2 = 0.9388).Footnote1 In comparative dynamics, TTs have managed to increase their coverage in mass media over the 15 years analysed here, progressing from an overall number of 8,588 news in which they had been mentioned—titles, summary and/or news—during the stage of economic growth between 2004 and 2006 (P1), up to 29,521 news in the new phase of economic growth between 2015 and 2018 (P5). The phases of crisis (P2), adjustments-reforms (P3), and economic recovery (P4) were decisive for this trend growth.

Despite a setback registered in 2013, which was the first year of the economic recovery phase (P4), the aggregate behaviour for all TTs () confirms the steadily growing trend in time; hence, H1 is accepted.

This result suggests that the TTs took advantage of the crisis situation and the debate related to austerity and adjustment measures to increase their presence in the media.

H2a. Media coverage of TTs is inversely related to the economic cycle: the worse the performance of macroeconomic indicators is, the greater the media coverage of TTs will be, and vice versa.

In the analysis of the phases of economic growth (P1), crisis (P2), adjustment-reforms (P3), recovery (P4), and economic growth (P5), the increased coverage of the studied TTs in the media is constant () and not inversely related to the economic cycle. Thus, H2a is rejected.

Empirical evidence shows that the TTs articulated their long-term media representation strategy without being influenced by the evolution of macroeconomic variables.

H2b. The evolution of the media coverage is constant across phases and homogeneous among TTs.

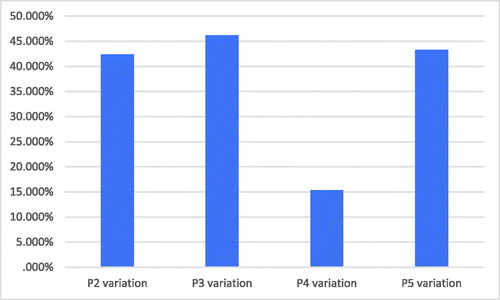

The variation rate of the media coverage of TTs was irregular (). The overall coverage went up to 42.33% during the crisis phase (P2), compared to the previous one, being similar to the increases in the phases of adjustment-reforms (P3) and growth (P5), specifically, 46.16% and 43.26%, respectively. However, even though the coverage continued to grow throughout the recovery period (P4), its increase rate was much lower, 15.34%, compared to the phase that immediately preceded.

Figure 3. Variation rates in the evolution of media coverage of Spanish TTs across phases. Source: Own elaboration.

The coverage of the messages of TTs during both the crisis (P2) and the adjustment-reform phase (P3) was greater, which means that public opinion was induced to begin suggestive debates on the solutions and measures against the crisis during these two periods. In this case, an attempt was made to model consensus for the approval of the austerity policies applied by the government.

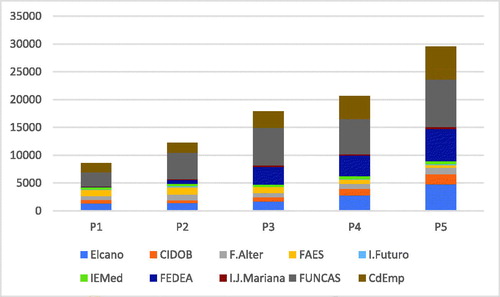

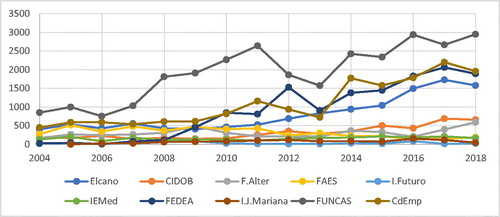

The increase in media coverage was uneven for the different TTs and phases (). The FEDEA’s growth and leading role from the adjustment-reforms phase (P3) onward was significant, as well as the constant evolution of the FUNCAS from the crisis phase (P2) to the growth period phase (P5). Meanwhile, the two TTs that were more oriented towards international relations—the CIDOB and the Elcano Royal Institute—significantly increased their coverage in the adjustment and reform phases (P3), showing a clear upward trend since the recovery (P4).

The increase of media coverage during the crisis stage (P2) was transversal in the case of all TTs (), except for the CIDOB, which fell back. In the adjustment-reforms phase (P3), the TTs that contributed the most to the overall increase of media coverage were the FEDEA, the Entrepreneurs Circle, the FUNCAS, and the Elcano Royal Institute, while those that fell back were the Fundación Alternativas, the FAES, and the Instituto Futuro. In the phases of recovery (P4) and growth (P5), a generalised increase is observed.

Table 3. Media coverage of TTs across stages.

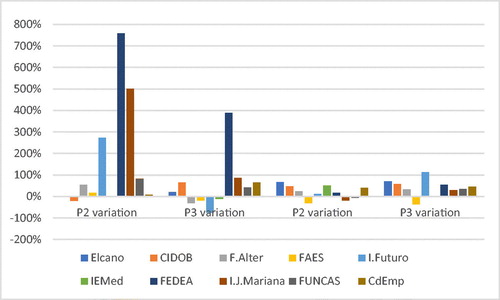

The behaviour of the relative variation rates across phases can be seen in the detailed analysis (), where the Fundación Alternativas, the FAES, the Instituto Futuro, and the IEMed fell back in the adjustment-reforms stage (P3), compared to the crisis phase (P2), while the FEDEA, the Juan de Mariana Institute, the FUNCAS, the Entrepreneurs Circle, and the CIDOB increased their coverage in the same period. The latter decreased its media coverage during the crisis phase (P2), in comparison with the previous period of growth (P1). The significant evolution of the variation rate must be emphasised in the case of the FEDEA. In both the crisis (P2) and the adjustment-reforms phases (P3), it grew from a minimum activity in the crisis phase (P2) to a marked activity, which placed this TT among the four with the greatest media coverage in the adjustment-reforms phase (P3). Meanwhile, there was a considerable and constant decline in the media coverage of the FAES, which continued to fall along the analysed period. This trend matches what was observed by Parrilla et al. (Citation2016), namely that the media tend to resort to those TTs with no obvious link to a specific political party.

Figure 5. Variation rates of media coverage across phases, detailed by TTs. Source: Own elaboration.

For all the above reasons, H2b must be rejected, since the evolution of the media coverage of TTs was not constant but variable, specific to each TT throughout the five analysed phases.

H3. The media publications of TTs that show greater impact capacity are correlated.

The growing trend of contents was maintained in the long-term due to the great amount of publications in the media with reference to the Elcano Royal Institute, the CIDOB, the FEDEA, the FUNCAS, and the Entrepreneurs Circle ().

The coverage of these TTs is related to their greater overall capacity for the generation of news and debates in the media. The evidence () shows a correlation between publications with references to the Elcano Royal Institute, the CIDOB, and the Entrepreneurs Circle. The publications of the FEDEA are correlated with those that refer to the Entrepreneurs Circle, and vice versa. Similarly, the contents that refer to the FUNCAS are correlated with those that include references to the Juan de Mariana Institute, and vice versa. The latter is a TT with less influence on the media compared to the Elcano Royal Institute, the CIDOB, the FEDEA, the FUNCAS, and the Entrepreneurs Circle.

Table 4. Evolution of reputation across phases, detailed by TTs.

Despite this, H3 must be accepted, since there is no correlation between the contents related to TTs with greater coverage in the media and those related to TTs with less coverage.

The debate in the media about the effects of public policies shows a coordinated action among the most relevant TTs, which act as an anchor for the rest of the TTs. The scheme of TT networks detected is consistent with the studies by Sánchez and Miranda (Citation2014).

H4a. The international media coverage of TTs increased over the analysed period.

The analysis of the news published in the international media shows an upward trend for the overall number of TTs under study, during the researched period (R2 = 0.9109).Footnote2 In the comparative dynamics of the 15 years under study, TTs managed to increase their international media coverage, climbing from a total volume of 831 news during the economic growth phase between 2004 and 2006 (P1), which represented 9.6% of the total of publications, up to an overall volume of 4,102 news in the economic growth stage from 2015 to 2018 (P5). These figures represented 13.89% of publications, where the phases of crisis (P2), adjustment-reforms (P3), and economic recovery (P4) played a crucial role.

As observed in the total analysis of publications (H1), there was a slight decline in the international media coverage of TTs in 2013, a decrease that was balanced by the increase of the international coverage registered in 2014, the year after which the series returned to its trend path. Therefore, H4a is accepted ().

H4b. The increase of international media coverage of TTs was homogeneous among the different TTs throughout the analysed period.

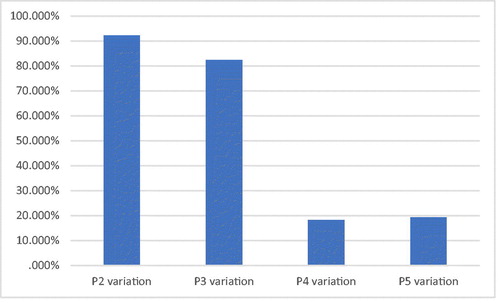

The upward trend of international media coverage of TTs was not constant. The variation rates across phases were higher during the phases of crisis (P2) and adjustment-reforms (P3) than during recovery (P4) and economic growth (P1, P5). While the variation rate of international media coverage reached 92.18% during the crisis phase (P2) compared to the immediately preceding period, it declined to 82.28% in the adjustment-reforms stage (P3). The international reputation of TTs continued to grow in the phases of recovery (P4) and growth (P5). However, its intensity was more moderate, showing variation rates of 18.74% (P4) and 19.24% (P5) compared to previous phases. Thus, H4b is rejected ().

H5. TTs with greater national media coverage achieved greater international media coverage throughout the analysed period.

The international media coverage of TTs was correlated to acceptable levels of significance during the phases of crisis (P2), adjustment-reforms (P3), and recovery (P4). However, the stages of economic growth (P1 and P5) did not show a correlation between national and international media coverage. H5 must be rejected because the correlation was not consistent throughout all periods. These results clearly show that a homogeneous discourse favours its wider coverage (Davis, Citation2012) ().

Table 5. Local news and international news.

H6. TTs with greater media coverage increased the weight of their hegemony throughout the analysed period.

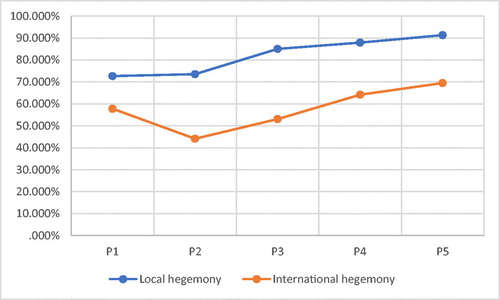

TTs with greater coverage represented 72.94% of media coverage in the growth stage (P1), increasing their influence in public discourse throughout the different stages (P2, P3 and P4), until they reached 90.93% in the growth stage (P5). They increased their impact capacity, getting to an average of 85.1% of publications during the 15 years under study. In addition, there is evidence of enhanced concentration of the message impact coming from a few TTs; hence, H6 is accepted ().

Table 6. Hegemony of TTs during the period from 2004 to 2018.

The main TTs reinforced their ability to influence, consolidating their media coverage after the crisis, and reinforcing their hegemony and the authority of their messages in public debate.

H7. TTs with greater media coverage increased the weight of their national hegemony more than their international hegemony, across the analysed period.

The hegemony of the discourse of the TTs that had greater media coverage () was always greater from a national versus an international perspective in the periods under study. Comparatively, these TTs with greater coverage were less able to leverage the overall weight of the debate generated by the TTs analysed within the international discourse during the crisis stage (P2), compared to the rest of the stages. In other words, the concentration of the message impact of a few TTs was greater in the national than in the international media; therefore, H7 is accepted.

Spain had characteristics that made the TTs increase their national hegemony more than their international hegemony. Spanish public opinion was much more worried than international public opinion because of the severe economic contraction, high unemployment rates, the great structural deficit, and the rapid increase in public debt. The evidence found shows that the debate on structural reforms and economic adjustment was increasing, helping citizens to understand these changes, contributing to the debate on structural reforms and economic adjustment, and finally to the acceptance of the austerity measures that were being approved.

The following table summarises the hypotheses that were accepted or rejected, according to the results obtained ().

Table 7. Hypotheses verified or rejected.

5. Conclusions

The 2007 to 2008 economic crisis is a subject of great importance that facilitates the analysis of the impact capacity of Spanish TTs in media discourse. Despite the fact that this research focuses on the Spanish case, the evidence found suggests important elements that can be extended to other regions in similar economic contexts.

The media coverage of TTs showed its greatest momentum in the context of the adjustment-reforms stage (P3), introducing persistent elements that served to influence public opinion on austerity policies. These results are in line with the contributions of Parrilla et al. (Citation2016). In this way, TTs managed to increase their visibility in the media, taking advantage of the context of crisis and the generation of debates on the design of public policies. A consequence of this was that the consistency of the message impact of TTs in the media was four times greater in 2018 than in 2004.

The implications of this finding assume that the TTs take advantage of the crisis and the timing of the design of adjustment measures to increase their ‘medical’ representation, provoking debates about the effect of austerity public policies.

A limitation of this study is the sample size of the TT analysed. Future historical studies may expand the analysis to include other Spanish TTs.

Another limitation of the study is that its approach is strictly quantitative. Upcoming lines of research could expand this work with a semantic and content analysis of the discourse that each TT introduces in the public debate.

Future lines of research should analyse whether the crisis produced a polarisation of the public policy debate. In this way it would be possible to assess whether the diversity of views was reduced from the economic recovery. Another future contribution involves linking these points of view with the different lines of political thought on economic austerity and control of the public deficit.

In future studies, it would be interesting to determine to what extent this fact may limit the freedom of the leaders responsible for the design of public policies, there being a certain tradition of political clientelism in the Spanish media (Hallin & Mancini, Citation2004).

Future studies should assess the effect of Spanish TTs on foreign ones and especially, the effect of foreign TTs on Spanish TTs, particularly during the phases of crisis and adjustment-reform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Exponential regression was used due to its better statistical adherence to the available data.

2 Linear regression was used based on its best statistical adherence to the set of available data.

References

- Abelson, D. E. (2009). Do think tanks matter? Assessing the impact of public policy institutes. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Abelson, D. E. (2012). Think-tanks, social democracy and social policy. Parliamentary Affairs, 66(4), 894–902. doi:10.1093/pa/gss051

- Alesina, A., & Ardagna, S. (2010). Large changes in fiscal policy: Taxes versus spending. Tax Policy and the Economy, 24(1), 35–68. doi:10.1086/649828

- Almiron, N. (2016). Think tanks y neoliberalismo. Capitalismo Financiero y Comunicación, 8, 195.

- Arshed, N. (2017). The origins of policy ideas: The importance of think tanks in the enterprise policy process in the UK. Journal of Business Research, 71, 74–83. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.015

- Auerbach, A. J., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2012). Measuring the output responses to fiscal policy. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(2), 1–27. doi:10.1257/pol.4.2.1

- Barani, L., & Sciortino, G. (2011). The role of think tanks in the articulation of the European public sphere. Eurosphere: Comparative studies. Work package 5.1 report.

- Bernardino, A. C., & Carrasco, I. M. D. V. (2014). Crisis y cambios estructurales en el sector bancario español: Una comparación con otros sistemas financieros. Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 32(2), 4–32.

- Blanchard, O. J., & Leigh, D. (2013). Growth forecast errors and fiscal multipliers. American Economic Review, 103(3), 117–120. doi:10.1257/aer.103.3.117

- Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity. The history of a dangerous idea. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Castaño, M. S., Méndez, M. T., & Galindo, M. Á. (2015). The effect of social, cultural, and economic factors on entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1496–1500. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.040

- Castillo-Esparcia, A., Guerra-Heredia, S., & Almansa-Martínez, A. (2017). Political communication and think tanks in Spain. Strategies with the media. El Profesional de la Información, 26(4), 706–2407. doi:10.3145/epi.2017.jul.14

- Chuliá, E. (2018). Una aproximación a los think tanks como organizaciones proveedoras de información y análisis a la sociedad. Revista Española de Sociología, 27(2), 333–340. doi:10.22325/fes/res.2018.27

- Christiano, L., Eichenbaum, M., & Rebelo, S. (2011). When is the government spending multiplier large? Journal of Political Economy, 119(1), 78–121. doi:10.1086/659312

- Davis, A. (2012). Mediation, financialization and the global financial crises: An inverted politi- cal economy perspective. In D. Winseck & D. Y. Yin (Eds.), The political economies of media: The transformation of the global media industries (pp. 241–254). London, England: Bloomsbury Academic.

- De Grauwe, P., & Ji, Y. (2013). Self-fulfilling crises in the eurozone: An empirical test. Journal of International Money and Finance, 34, 15–36.

- Denham, A. (2005). British think-tanks and the climate of opinion. London: Routledge.

- Eggertsson, G. B., & Krugman, P. (2012). Debt, deleveraging, and the liquidity trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), 1469–1513.

- Factiva. (2019). Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved from https://www.dowjones.com/products/factiva/.

- Griffin, J. M., Hirschey, N. H., & Kelly, P. J. (2011). How important is the financial media in global markets? Review of Financial Studies, 24(12), 3941–3992.

- Hall, P. A. (2014). Varieties of capitalism and the euro crisis. West European Politics, 37(6), 1223–1243. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.929352

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Heller, P. S. (2003). Considering the IMF's perspective on a “sound fiscal policy”. FinanzArchiv, 59(1), 141–161. doi:10.1628/0015221032906108

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. New York: Prometheus Books.

- Kindleberger, C. P. (1986). The world in depression, 1929–1939 (Vol. 4). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2008). Systemic banking crises: A new database. Working Paper WP/08/224. International Monetary Fund.

- Lalueza, F., & Girona, R. (2016). The impact of think tanks on mass media discourse regarding the economic crisis in Spain. Public Relations Review, 42(2), 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.09.006

- Leeson, P. T., Ryan, M. E., & Williamson, C. R. (2012). Think tanks. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(1), 62–77. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2011.07.004

- McGann, J. G. (2018). 2017 global go to think tank index report. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania.

- McGann, J., Viden, A., & Rafferty, J. (2014). How think tanks shape social development policies. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press.

- McGann, J. G. (2007). Think tanks and policy advice in the United States. Academics, advisors and advocates. New York: Routledge.

- Mac Gann, J. G., & Weaver, R. K. (Eds.). (2000). Think tanks & civil societies: Catalysts for ideas and action. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Matthijs, M., & McNamara, K. (2015). The euro crisis’ theory effect: Northern saints, southern sinners, and the demise of the eurobond. Journal of European Integration, 37(2), 229–245. doi:10.1080/07036337.2014.990137

- Matthijs, M. (2014). The eurozone crisis: growing pains or doomed from the start? In Handbook of global economic governance (pp. 201–217). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Medvetz, T. (2008). Think tanks as an emergent field. New York: The Social Science Research Council.

- Misztal, B. A. (2012). Public intellectuals and think tanks: A free market in ideas? International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 25(4), 127–141. doi:10.1007/s10767-012-9126-3

- Montobbio, M. (2013). La geopolítica del pensamiento: think tanks y política exterior. Madrid: Real Instituto Elcano.

- Mulgan, G. (2006). Thinking in tanks: The changing ecology of political ideas. The Political Quarterly, 77(2), 147–155. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2006.00757.x

- Parrilla, R., Almiron, N., & Xifra, J. (2016). Crisis and interest: The political economy of think tanks during the great recession. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(3), 340–359. doi:10.1177/0002764215613404

- Pautz, H. (2010). Think tanks in the United Kingdom and Germany: Actors in the modernisation of social democracy. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 12(2), 274–294. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00402.x

- Plehwe, D., Neujeffski, M., & Krämer, W. (2018). Saving the dangerous idea: Austerity think tank networks in the European Union. Policy and Society, 37(2), 188. doi:10.1080/14494035.2018.1427602

- Posner, R. A. (2001). Public intellectuals. A study of decline. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2009). The aftermath of financial crises. American Economic Review, 99(2), 466–472. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.466

- Rich, A. (2004). Think tanks, public policy and the politics of expertise. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rich, A., & Weaver, R. K. (2000). Think tanks in the U.S. media. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 5(4), 81–103. doi:10.1177/1081180X00005004006

- Romer, C., & Bernstein, J. (2009). The job impact of the American recovery and reinvestment plan. Washington, DC: Obama Transition Team.

- Romero, J. M. (2010). Dos minutos que cambiaron a España. EL PAÍS. http://bit.ly/12i2Fty.

- Sánchez, J. A., & Miranda, J. P. (2014). Ideas locales que viajan en inglés: análisis de redes de think-tanks en Twitter, 1–24. doi:10.13140/2.1.2455.9048

- Saura, G. (2015). Think tanks y educación. Neoliberalismo de FAES en la LOMCE. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(107), 1–19. doi:10.14507/epaa.v23.2106

- Shaw, S. E., Russell, J., Parsons, W., & Greenhalgh, T. (2015). The view from nowhere? How think tanks work to shape health policy. Critical Policy Studies, 9(1), 58–77. doi:10.1080/19460171.2014.964278

- Sherrington, P. (2000). British think tanks: Advancing the intellectual debate? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 2(2), 256–263. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.00036

- Spanish Constitution. (1978). Official state gazette, December 29, 311, 29313–29424.

- Stiglitz, J. (2013a). Five years in limbo. Social Europe Journal. Retrieved from http://www.socialeurope.eu/2013/10/five-years-in-limbo/.

- Stiglitz, J. (2013b). The lessons of the North Atlantic crisis for economic theory and policy. IMF Direct. Retrieved from http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2013/05/03/the-lessons-of-the-north-atlantic-crisis-for-economic-theory-and-policy/.

- Stone, D. (2004). Introduction: Think tanks, policy advice and governance. In D. Stone & A. Denham (Eds.), Think tank traditions. Policy research and the politics of ideas (pp. 35–50). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Tetlock, P. C. (2007). Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. The Journal of Finance, 62(3), 1139–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01232.x

- Wiarda, H. (2008). The new powerhouses: Think tanks and foreign policy. American Foreign Policy Interests, 30(2), 96–117. doi:10.1080/10803920802022704

- Xifra, J. (2005). Los think tank y advocacy tank como actores de la comunicación política. Anàlisi, 32, 73–91.