?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the impacts of institutional quality and business environment on Chinese foreign direct investment (F.D.I.) flow to Africa. We derive aggregate indicators of institutional quality and business environment using economic and governance institutions, doing business, transport efficiency indicators conducting a principal component analysis. We employ Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (P.P.M.L.) procedure to estimate the gravity model of F.D.I. flow as it can solve zero-valued observations and heterogeneity problems. Our findings disclose that institutional quality and business environment indicators are significant motivators of Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa. Our findings are robust and similar after we account for endogeneity concerns using an I.V. estimator. Based on our results, we conclude that improvement in the business environment and the institutional quality of African countries is key to spurring Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa.

1. Introduction

Chinese engagement in African countries is not a recent phenomenon. However, their economic relation has experienced the fastest growth after the forum on the China–Africa cooperation conference in Beijing in 2000. This Africa–China economic tie has been mainly manifested by trade openness, Chinese foreign direct investment (F.D.I.) flow and financial assistance for African countries. Chinese F.D.I. into African countries has grown rapidly in recent years since the conference. For example, Chinese F.D.I. stock in sub-Saharan African countries reached nearly US$24 billion in 2013, reflecting an annual growth rate of more than 50% between 2004 and 2013 (Copley, Maret-Rakotondrazaka & Sy Citation2014).

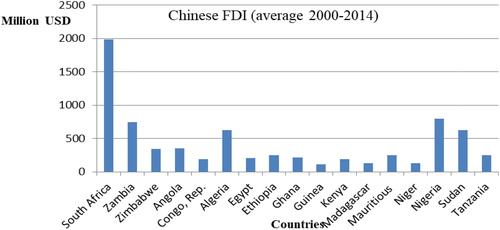

Furthermore, Chinese F.D.I. into Africa increased dramatically in 2016, registering a 106% jump in projects (EY Africa, 2017). This rapid growth of Chinese F.D.I. in Africa is considered as one of the indicators of Africa's development potential and investment appeal and also points to the mutually beneficial nature of China–Africa cooperation. The interesting thing about Chinese F.D.I. is its composition. It is more diversified than the composition of other major countries that are investing in Africa. It consists 19.5% in financial services sector, 16.4% in construction sector, 15.3% in manufacturing, and the remaining 18.2% in business and tech services, geological prospecting, wholesale retail, agriculture and real estate (Copley et al., Citation2014) and it is also distributed in almost all African countries ( in Appendix).

However, according to the existing empirical studies this diversified Chinese F.D.I. inflow to African countries is claimed to be driven by natural resources, infrastructure sectors for export of natural resources and market size. For example, studies by Adisu, Sharkey and Okoroafo (Citation2010) reveal that Chinese F.D.I. inflow to African countries is claimed to follow the state-driven strategy of giving infrastructure and taking natural resources. In addition, a study by Cheung et al. (Citation2011) suggests that China’s investment in Africa is driven by the common traditional determinants considered in the literature on Chinese foreign investment to African countries. Hence markets and resources seeking motives and economic risk factors are significant determinants of China’s F.D.I. to Africa. Similarly, a study by Sanfilippo (Citation2010) implies that Chinese F.D.I. to Africa is pushed by the need to satisfy a growing internal demand for natural resources and good market potential to place its low-cost production. To our knowledge, no previous research studies have examined the domestic investment environment and institutional quality as determinants of Chinese F.D.I. to African countries.

Several pieces of empirical literature (Kapuria-Foreman, Citation2008; Anyanwu, Citation2012; Buchanan, Le and Rishi, Citation2012; William, Agyapong and Abass, Citation2013) argue that institutional factors such as good governance, economic freedom, and a business-friendly regulatory environment are the most important in investors' decision-making are becoming highly popular determinants of F.D.I. flow, indicating a shift from market and resource seeking to efficiency-seeking motives to F.D.I. That is traditional F.D.I. promoters such as natural resources and market size are relatively becoming less important, while less traditional factors, such as business environment, institutional quality and governance, and economic freedom are becoming major promoters of F.D.I. flow. In addition, a study by Ali, Feiss and MacDonald (Citation2010) shows that institutional quality more specifically economic institutions such as property right and contract enforcement are robust factors to attract F.D.I. Similarly, an improvement in doing business indicators (ease of doing business) is becoming one of the important factors to attract more F.D.I. to developing countries (Bayraktar, Citation2015; Moran et al., Citation2018). Therefore, empirical assessment of the drivers of Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries should take into account the business environment and institutional quality on the top of the traditional determinants of F.D.I. flow.

Hence, the major aim of this article is to examine the impact of the domestic business environment and institutional quality on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. We match aggregate indicators of business environment and institutional quality indicators (doing business, border and transport efficiency, economic freedom and governance) of African countries with Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa. In addition, we examine the impact of major economic freedom indicators on Chinese F.D.I. flow separately. Our results provide evidence that Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries is significantly affected by the business environment and institutional quality.

This study is significant for a few reasons. First, it examines the role of business environment and institutional quality on Chinese F.D.I. flow which is an under-researched topic. Second, we employ Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (P.P.M.L.) estimator that helps include zero-valued observations in the sample and robust method of estimation in the presence of heteroscedasticity. Finally, our results are robust and have no evidence of endogeneity problem.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Part two discusses the literature review. Part three explains the data and methodology of the study. Part four presents the results and findings of the study. Part five provides results of robustness check for endogeneity, and part six gives conclusions.

2. Literature review

Economic literature examining the drivers of F.D.I. flow have arisen aiming primarily to pinpoint which factors F.D.I. recipients have to provide. Over the last several decades, a consensus has emerged that donor interests and the recipient needs to shape the F.D.I. flow among countries. Using the Heckscher–Ohlin (H–O) trade model to explain the motives behind investors who operate production chains abroad in 1960s and internalization theory, which was introduced by Buckley and Casson in 1976, Dunning developed O.L.I. paradigm. The O.L.I. paradigm consists of three sub-paradigms from which one can analyse the reasons why firms engage in F.D.I.: Ownership (O), Location (L), and Internalization (I). These determinants have categorised into three types: market-seeking, resource-seeking, and efficiency-seeking (Dunning, Citation2000). Furthermore, Helpman, Melitz and Yeaple (Citation2004) developed a theory that relates F.D.I. to international trade. On the other hand, Nocke and Yeaple (Citation2008) developed an assignment theory to analyse the volume and composition of F.D.I.

Based on the above theories and motives of F.D.I. flow a number of empirical studies have been conducted so far regarding the determinants of F.D.I. flow to different countries. For example, using Bayesian statistical techniques, Blonigen and Piger (Citation2011) selects from a large set of candidates from those variables most likely to be determinants of F.D.I. find that cultural distance, per capita G.D.P., labour endowments and trade are the major determinants of F.D.I. flow to developing countries. However, the little support is found for trade openness, host-country business costs, host-country infrastructure and institutions. Similarly, Abbas and Mosallamy (Citation2016) using a panel data model found that resources, market openness, human capital, infrastructure and political stability are significant determinants of F.D.I. Likewise, Richet (Citation2019) reveals that countries with smaller market opportunities receive less direct investment.

Most of F.D.I. literature emphasis on tradition determinants of F.D.I flow. However, recently, some empirical studies have been conducted on the impact of institutional quality on cross countries F.D.I. flow. Kapuria-Foreman (Citation2008) employs cross-country growth regressions for a sample of developing countries to examine the effects of institutional quality more specifically the effect of economic institutions such as enforcement of property rights, corruption and policy orientation factors (openness) find that F.D.I. positively responds to changes in levels of economic freedom. Similarly, Ali et al. (Citation2010) and Buchanan et al. (Citation2012) examine the effect of institutional quality on F.D.I. based on a panel data analysis found that the governance infrastructure has a positive effect on F.D.I. flows. Using corruption control, the rule of law and regulatory quality Anyanwu (Citation2012) reveals the prevalence of the rule of law increases F.D.I. inflows to African countries. Bayraktar (Citation2015) examines the link between F.D.I. and business environment using ease of doing business indicators shows that countries which have better records of doing business tend to attract more F.D.I. In addition, Moussa, Çaha and Karagöz (Citation2016) investigate the impact of economic freedom on F.D.I. inflows in both global and regional panel analysis concerning 156 countries, including fragile and conflict-affected states, sub-Saharan countries. Their results show a positive impact of economic freedom on F.D.I.

Most of the earlier studies on Chinese F.D.I. have been emphasising market size and natural resources motives. Studies examining the association between Chinese F.D.I. and the business environment and institutional quality of African countries are limited. A study by Sanfilippo (Citation2010) and Cheung et al. (Citation2011) suggests that China’s investment in Africa is driven by the common traditional determinants considered in the literature on Chinese foreign investment to African countries. Thus, this study aims to examine the impact of the business environment and institutional quality on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. The data

Our study covers Chinese F.D.I. flow to 44 African countries for the periods 2003–2014 based on data availability. The list and definition of variables and data sources are given in the Appendix (). The countries included in the sample are also listed in the Appendix (). Chinese F.D.I. to Africa used in this study is compiled from U.N.C.T.A.D. bilateral F.D.I. statistics and China statistical yearbook by Johns Hopkins S.A.I.S. China–Africa Research Institute from the year 2003 (China Africa Research Initiative, 2017). Facts of the explanatory variables controlled in this study are spelled out in the following part.

3.1.1. Political and governance index

The empirical analysis for this article utilises a political and governance institution data set of governance indicators of worldwide governance indicators (W.G.I.), namely: the rule of law, the absence of violence and instability, regulatory quality, government effectiveness, voice and accountability and control of corruption. The rule of law shows contract and property right protection and abilities of police and court to enhance private rights. Political stability and absence of violence represents the capacity of government in avoiding internal and external conflicts and ethnic tensions and control of corruption indicates the position of countries in fighting against corruption. Regulatory quality captures perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that promote private sector development. Government effectiveness captures perceptions of the quality of public and civil services, and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation. Voice and accountability catches view of the degree to which citizens can take an interest in selecting their government, the opportunity of free expression and association, and a free media. Their values range from –2.5 to 2.5 with higher values corresponding to better institutions.

Using these indicators of institutional quality of African countries, we derive a single composite index using principal component analysis. The eigenvalue of the first principal component of institutional quality is greater than 1 (4.565 > 1). However, none of the other components have eigenvalues more than 1. Since the first component explains 76% of the variation in the original variables, the study uses the eigenvectors of the first principal component (see in Appendix). Furthermore, we employ the polity variable to proxy the democracy level of African countries.

3.1.2. Border and transport efficiency indices

We add border and transport efficiency indicators into our analysis using six soft transport and border efficiency indicators. These are the cost of export, cost of import, time to export, time to import, documents to export and documents to import. The cost of export and import measures the fees imposed on a 20-foot container in U.S. dollars. It includes charges associated with completing the processes to export or import the goods. Time to export and to import is measured by the time recorded in calendar days. The time calculation for an export or import process starts from the moment it is started and runs until it is completed. All documents required per shipment to export or import goods are captured.

Using principal component analysis, we find two aggregate indicators of border and transport efficiency index. The eigenvalues of the first two components of the border and transport efficiency are 1.749, 3.799 and 1.369, explaining 63.3% and 22.8% of the total variance, respectively. Hence we include the first two principal components of border and transport efficiency as the sum of the variances of the individual components 87.1% (see in Appendix). We hypothesise that there should be a negative relationship between border and transport efficiency indicators and Chinese F.D.I. flow because of the ease of cross border trading activities promotes F.D.I. inflow (William et al., Citation2013).

3.1.3. Doing business index

We control for doing business index using four ease of doing business indicators of world development indicators (W.D.I.) such as cost to start the business, cost to enforce the contract, cost to register property right and minimum capital required to start the business. The eigenvalues of the first two components of these indicators are greater than 1 (1.749 and 1.058 > 1). The first two principal components of doing business have variance 1.749 and 1.058, explaining 44% and 26.5% of the total variance, respectively explaining 70% of the total variance (see in Appendix). We hypothesise that a better business environment promotes Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa because countries with better records of doing business environment attract more F.D.I. (Bayraktar, Citation2015).

3.1.4. Economic freedom indicators

Economic freedom indicator is used to proxy economic institutions of African countries (Pearson, Nyonna & Kim, Citation2012). We add property right, legal protection, regulation, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, government size and investment freedom. In all cases, the values of these indicators vary from 0 to 10, with higher values corresponding to a better status. Our hypothesis is that there should be a positive association between economic freedom and Chinese F.D.I. flow because a higher degree of economic freedom results in higher F.D.I. inflow (Pearson et al., Citation2012).

3.1.5. Other traditional determinants

Real G.D.P. per capita and population size: They are used to proxy market size. Countries with a high level of per capita G.D.P. might attract less F.D.I. inflows because it indicates a lower marginal product of capital (Arbatli, Citation2011). A country with a big population size attracts more F.D.I. inflow (Peres, Ameer & Xu, Citation2018).

Distance: Is represented by the physical distance between African countries and China. Chinese F.D.I. in Africa tends to be more concentrated in the East and South African regions. Some of the reasons why East Africa stands out as a popular destination for these private Chinese investments maybe because of its relative closeness to China (Chen, Dollar & Tang, Citation2015).

Real G.D.P. per capita of China: We include real G.D.P. per capita of China based on the work of Blonigen and Piger (Citation2011) that shows 99% inclusion probability of origin countries’ real G.D.P. per capita.

Natural resources depletion: It is used to proxy the natural resources motives of Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries based on Foster, William, Chuan and Nataliya (Citation2009) which associate Chinese F.D.I. flow to natural resources extraction.

Diplomatic relationship: it is represented by China’s voting alignment with African countries in the U.N. General Assembly and a dummy of African countries on the recognition of one-China policy (Zhang, Jiang & Zhou, Citation2014).

China–Africa trade: It is used to measure African countries’ trade intensity with China following the works of Cheung et al. (Citation2011) that used to proxy economic links of China with African countries.

Inflation rate: It is used to represent the macroeconomic stability. Furthermore, domestic credit is used as a proxy to access credit and financial market.

Debt to G.D.P. ratio: It is used to proxy creditworthiness. External debt will have a negative effect on F.D.I., and increasing foreign debt will destroy foreign investors' vision and create negative expectations of the future economy (Ostadi & Ashja, Citation2014).

3.2. Methods of analysis

The empirical analysis of this article is based on the gravity specification of panel data. The estimation of the gravity model in the recent empirical literature is mostly based on panel data (Bussière, Fidrmuc & Schnatz, Citation2008; Westerlund & Wilhelmsson, Citation2011). The gravity specification developed by Tinbergen (Citation1962) to analyse international trade flow is shown in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . Trade flow between countries is a function of the mass of the country of origin, the mass of the country of destination and the physical distance between the two countries.

(1)

(1)

where Tij is international flow from reporter i country to partner j country (trade, F.D.I. and migration), Mi and Mj are the mass of the origin and destination countries (G.D.P. per capita of countries, population and so on), Dij is a physical distance between origin and destination countries. β and χ represent parameters and constant, respectively.

In gravity models, the issues of heteroscedasticity are significantly important. If the error term is heteroskedastic, which is highly probable in practice, then the expected value of the error term depends on one or more of the explanatory variables because it includes the variance term. This violates the first assumption of O.L.S. and suggests that the estimator may be biased and inconsistent. The presence of heteroscedasticity under the assumption of a multiplicative error term in the original nonlinear gravity model specification requires the adoption of P.P.M.L. (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006). Furthermore, if there are zero-valued observations, using the log-linear method to estimate the gravity model results in loss of information because transforming data to logarithm form drops zero-valued observations potentially leading to sample selection bias, which has become an important issue in recent empirical work. The approach followed by the large majority of empirical studies is to drop the pairs with zero-valued observations from the data set and estimate the log-linear form by O.L.S. In turn, dropping zero-valued observations reduces the efficiency of data and lead to biased estimates (Gómez-Herrera, Citation2013). However, this procedure will lead to inconsistent estimators of the parameters of interest.

The best alternative method for estimating the gravity model to accommodate zero-valued observation is the P.P.M.L. estimator. Thus, the ability of Poisson to include zero observations naturally and without any additions to the basic model is highly desirable. This estimator is generally well behaved even when the proportion of zeros in the sample is considerable (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2011). Alternatively, Prehn, Brümmer and Glauben (Citation2016) developed a random intercept P.P.M.L. model to allow for the estimation of exporter and importer invariant variables in the estimation. It is an ideal estimator for the gravity model if the sample size is large enough and the sample has many origin and destination countries. However, this method is ruled out in this study because the sample size is not large enough as that of trade flow and we have only one origin and many destination countries in the sample which do not allow us to estimate the effects of time-invariant characteristics of the pair.

We extend the P.P.M.L. estimator to estimate the gravity model of F.D.I. flow because there are some zero-valued observations and heterogeneity issues (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006; Westerlund & Wilhelmsson, Citation2011; Jacimovic, Mitrović, Bjelić, Tianping & Rajkovic, Citation2018). Thus, EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) can be augmented to include traditional gravity variables, institutional quality and business environment indicators in this study.

(2)

(2)

where FDIcit denotes F.D.I. from China to Africa, gdpca is real G.D.P. per capita, U.N.V. is China’s voting alignment with African countries in the U.N. General Assembly, exdept is debt G.D.P. ratio of African countries, natural is natural resources depletion rate of African countries, distw is distance between African countries and China, gdpc is real G.D.P. per capita of China, dip is dummy variable 1 if African country support one-China policy and 0 otherwise, chinatrade represents trade openness between China and African countries, pop is the population size of African countries, inf represents the inflation rate of African countries, cred is credit to the private sector, BE represents the level of democracy, business environment and institutional quality indicators of African countries and εijt is stochastic term.

Multilateral resistance term (M.R.T.), which is a function of exogenous variables, is taken into account by employing the Baier and Bergstrand (Citation2009) methodFootnote1. STATA 13 is used to exercise the model.

The log-linear transformation of EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) is:

(3)

(3)

4. Results and findings

In this section, we discuss the main findings of the study. presents P.P.M.L. estimation results for the impacts of the aggregate business environment and institutional quality on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

Table 1. The impacts of institutional quality and business environment on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

The results in reveal that the economic magnitude of African countries represented by their real G.D.P. per capita has a positive effect on F.D.I. flow from China to African countries. However, its effect is statistically insignificant except in column (ii). Additionally, population size has a significantly positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. This result indicates that an increase in population size provides a large market for products and services produced by Chinese F.D.I. in local markets. It also provides the economy with a large labour force. Hence, it suggests that Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa is associated with population size. The geographical distance between African countries and China has a significant negative effect on F.D.I. flow indicating that physical distance discourages flow of F.D.I. However, bilateral trade openness between China and Africa has a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Therefore, trade openness between China and African countries is one of the major drivers of Chinese F.D.I. to African countries. Besides, the G.D.P. per capita of China has a significantly positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. This indicates that one of the drivers of F.D.I. flow from China to African countries is an increase in the economic potential and magnitude of the Chinese economy.

The effect of diplomacy between China and African countries represented by China’s voting alignment with African countries in the U.N. General Assembly and recognition of the One-China policy has a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Therefore, the diplomatic relationship between China and African countries plays a significant role in attracting Chinese F.D.I. because it increases F.D.I. inflow by reducing barriers that may face Chinese investors in African countries.

Chinese F.D.I., however, is not significantly affected by natural resources extraction. This is because of Chinese F.D.I. presents in a broad range of countries, including non-resource-rich countries in East Africa such as Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania. On top of that, sizable F.D.I. inflows from China to Africa are going into the services sector, constituting more than 60%. This justification is true even in some oil-rich African countries. The remaining part goes to the manufacturing, construction, and natural resources sectors. Thus, against popular perception, most of the Chinese F.D.I. inflow is not focusing on natural resources motives.

Turning to our explanatory variables of main interest, all institutional quality and business environment indicators have expected signs and their effect is statistically significant but the first indicators of border and transport efficiency and political institution index. The coefficient of the business environment is negative and statistically significant, indicating that African countries with a conducive doing business environment attract more F.D.I. from China. Similarly, there is a significant negative association between border and transport efficiency indicator and Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries, indicating improvements in border and transport efficiency promotes Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

Furthermore, the economic freedom indicator has a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Furthermore, the coefficient of polity variable is significant at the conventional level, implying an improvement in democratic institutions promotes Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

Since economic freedom indicators are significantly important, we aim to examine the effect of each economic freedom indicator on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. We are interested in these indicators because it is believed that institutional quality, more specifically economic institutions such as property right and contract enforcement, profoundly matters for the attraction of F.D.I. Thus, compared to political and democratic indicators, economic institutions are more relevant to affect F.D.I. flow, more specifically, Chinese F.D.I. as China follows a noninterference policy. Hence in this part, we examine the effect of property right, legal enforcement, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, investment freedom, business regulation and government size on F.D.I. flow separately ().

Table 2. The impacts of separate economic freedom indicators on Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa.

The coefficients of property right and legal system are also positive and significant, indicating that improvement in security of property rights and legal systems affects Chinese F.D.I. flow positively. Hence Chinese F.D.I. is attracted to African countries where the rule of law, security of property rights, an independent and unbiased judiciary, and impartial and effective enforcement of the law are secured. Furthermore, the effect of regulation and sound money is significantly positive. This reveals that regulatory restraints that limit the freedom of exchange in credit, labour, and product markets discourage F.D.I. inflow to African countries. Similarly, the absence of sound money negatively affects Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Therefore, a secured property right and legal enforcement and noble regulatory environment drive Chinese F.D.I. to African countries.

5. Robustness check

According to some literature, there will be potential reverse causality between the business environment and institutional quality indicators and F.D.I. Hence business environment and institutional quality may not be determined exogenously; however, it may depend on the type of law that rules the country, the legal origins, and the level of economic development (Buchanan et al., Citation2012; Peres et al., Citation2018). If the business environment and institutional indicators are potentially endogenous, it is essential to look for alternative methods that do not suffer from the same problem. Therefore, to address the endogeneity concern we estimate instrumental variable (I.V.) using legal origin and the lagged values of independent variables as instruments for each institutional quality and business environment variables because these variables are controlled separately to proxy institutional quality and business environment of African countries (Buchanan et al., Citation2012; Peres et al., Citation2018). Countries with a lighter regulatory environment will have a better institutional quality and business environment. In our analysis we consider countries with French legal origin have lower institutional quality and highly regulated business environment because it is highly correlated with an excessive regulatory environment and may lead to lower quality institutions, mainly when the French legal system was implemented in developing countries (Djankov, La Porta, López-de-Silanes & Shleifer, Citation2002). However, common law (English origin) provides the next highest quality of law enforcement and also the highest protection (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1998).

We find almost the same results. The signs of coefficients and their level of significance are almost the same except minor differences in the coefficients and significance of real G.D.P. per capita, one-China recognition and credit to the private sector. This may happen because of exogeneity for the business environment and institutional quality indicators.

All indicators of business environment and institutional quality in are hardly affected, suggesting our findings are unlikely to suffer from serious reverse causality problems. The signs of coefficients of our interest variables and their significance are almost similar to our results in , proofing that there is no evidence of the endogeneity problem. Furthermore, the Wu–Hausman test for endogeneity indicates that there is no evidence of endogeneity as we fail to reject the null hypothesis that specifies no existence of endogeneity, proving the existence of exogeneity.

Table 3. The impacts of institutional quality and business environment on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

Furthermore, we test the endogeneity issue for each economic freedom indicators using the same instruments. The Wu–Hausman test of endogeneity in shows that there is no endogeneity problem.

Table 4. The impacts of separate economic freedom indicators on Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa.

The signs of coefficients of property right, legal enforcement, sound money, government size, investment freedom are consistent with the results in . Their effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow is robust positive. However, the coefficient of international trade freedom turns to negative and significant. Hence I.V. results are almost similar to our results in , confirming that there is no endogeneity problem.

6. Conclusion

This article examines the impact of institutional quality and business environment indicators on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Aggregate institutional quality and business environment indicators are derived employing principal component analysis using different institutional quality and business environment indicators. These aggregate indicators are economic and political institutions, doing business, border and transport efficiency of African countries. We employ the P.P.M.L. gravity model estimator which is robust to accommodate zero-valued observations and heteroscedasticity concerns. Furthermore, we conduct robustness check for endogeneity problem using I.V. controlling the legal origin and lagged values of the variables as instruments for institutional quality and business environment indicators. As these tests disclose our results are proven to be robust and do not suffer from reverse causality problem.

Controlling for different explanatory variables, our findings indicate that improvement in institutional quality and business environment of African countries have a significant positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. The coefficient of doing business environment is negative and statistically significant, indicating African countries with a conducive doing business environment attract more F.D.I. from China. Similarly, there is a significant negative association between border and transport efficiency and Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries, demonstrating improvements in border and transport efficiency promotes Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Additionally, economic institutional indicators have a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Besides, the coefficient of polity variable is significant at the conventional level indicating improvement in political and democratic institutions promotes Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries.

Furthermore, we examine the impact of separate indicators of economic freedom on Chinese F.D.I. flow because of economic freedom indicators such as property right and contract enforcement, sound money and investment freedom. Our estimates show that legal enforcement and property right have a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. Hence Chinese F.D.I. is more attracted to African countries where legal enforcement, security of property rights, an independent and unbiased judiciary are promoted. Also, business regulation and sound money have a significant positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa. Therefore, regulatory restraints that limit the freedom of exchange in credit, labour, and product markets and the absence of sound money obstruct Chinese F.D.I. inflow to African countries.

Our results also reveal that population size has a robust positive effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. This implies that Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries is motivated by market size as it delivers a large labour force and potential consumer that can promote production. Besides, there is a strongly significant positive association between Africa–China trade openness and Chinese F.D.I. flow to African countries. However, the coefficients of natural resources are insignificant revealing that Chinese F.D.I. flow is not tied with resources motives. Thus, against popular perception, most of the Chinese F.D.I. inflow is not primarily motivated by natural resources. Moreover, internal economic growth of the Chinese economy and the diplomatic relationship between China and African countries significantly affect F.D.I. flow from China to African countries. The debt per G.D.P. has a robust negative effect on Chinese F.D.I. flow revealing African countries with higher debt-G.D.P. ratio likely receive less Chinese F.D.I. compared to countries with lower debt per G.D.P.

To conclude, our results provide evidence that the business environment and institutional quality of African countries significantly matter for Chinese F.D.I. flow to Africa. Hence to promote F.D.I. flow from China to Africa, it is significantly essential to improve the quality of the domestic business environment and institutions of African countries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and referees for their insightful suggestions that significantly improved the article.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We replace the bilateral variable that accounts for F.D.I. flow cost (distance) by M.R.T. in the model following Baier and Bergstrand (Citation2009) methods BY indexing (i,b,c) for reporters countries and (j,e,f) for partner country (China).

MRTlnXijt = lnXijt-{ +

-

}

Where, X is bilateral variables accounting for bilateral F.D.I. flow costs, θi=Yi/YT and θj=Yj/YT, Yi=G.D.P.cit, YT=G.D.P.cworld

References

- Abbas, S., & Mosallamy, D. (2016). Determinants of FDI flows to developing countries: An empirical study on the MENA region. Journal of Finance and Economics, 4(1), 30–38. doi:10.12691/jfe-4-1-4

- Adisu, K., Sharkey, T., & Okoroafo, S. C. (2010). The impact of Chinese investment in Africa. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(9), 3–9. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v5n9p3

- Ali, F. A., Fiess, N., & MacDonald, R. (2010). Do institutions matter for foreign direct investment? Open Economies Review, 21(2), 201–219. doi:10.1007/s11079-010-9170-4

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2012). Why does foreign direct investment go where it goes?: New evidence from African countries. Annals of Economics and Finance, 13(2), 425–462. http://aeconf.com/Articles/Nov2012/aef130207.pdf

- Arbatli, E. (2011). Middle East and Central Asia department economic policies and FDI inflows to emerging market economies (IMF Working Paper No. 11/192). Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp11192.pdf.

- Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2009). Bonus vetus OLS: A simple method for approximating international trade-cost effects using the gravity equation. Journal of International Economics, 77(1), 77–85. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2008.10.004

- Bayraktar, N. (2015). Importance of investment climates for inflows of foreign direct invest to developing countries. Business and Economic Research, 5(1), 24–50. doi:10.5296/ber.v5i1.6762

- Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. (2011). Determinants of foreign direct investment (NBER Working Paper No. 16704 Issued in January 2011). Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w16704.

- Buchanan, B. G., Le, Q. V., & Rishi, M. (2012). Foreign direct investment and institutional quality: Some empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 21, 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2011.10.001

- Bussière, M., Fidrmuc, J., & Schnatz, B. (2008). EU Enlargement and Trade Integration: Lessons from a Gravity Model. Review of Development Economics, 12(3), 562–576. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9361.2008.00472.x

- CEPII (2015). Gravity CEPII. Retrieved from http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/en/bdd_modele/download.asp?id=8.

- Chen, W., Dollar, D., & Tang, H. (2015). Why is China investing in Africa? Evidence from the firm level. Brookings. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/why-is-china-investing-in-africa-evidence-from-the-firm-level/.

- Cheung, Y.-W., de Haan, J., Qian, X. W., & Yu, S. (2011). China’s outward direct investment in Africa (HKIMR Working Paper No.13/2011 Issued in April 2011). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1824167

- China Africa Research Initiative (2017). Data: China-Africa Trade 2017. Retrieved from http://www.sais-cari.org/data-china-africa-trade.

- China Africa Research Initiative (2017). Data: Chinese investment in Africa 2017. Retrieved from http://www.sais-cari.org/chinese-investment-in-africa.

- Copley, A., Maret-Rakotondrazaka, F., & Sy, A. (2014). The U.S.-Africa leaders summit: A focus on foreign direct investment. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/07/11/the-u-s-africa-leaders-summit-a-focus-on-foreign-direct-investment/.

- Djankov, S., La Porta, R., López-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 1–37. doi:10.1162/003355302753399436

- Dunning, J. H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review, 9 (2)000), 163–190. doi:10.1016/S0969-5931(99)00035-9

- EY_Africa (2017). EY’s attractiveness program Africa, connectivity redefined. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/za/en/home/article.

- Foster, V., William, B., Chuan, C., & Nataliya, P. (2009). Building bridges: China's growing role as infrastructure financier for sub-Saharan Africa (Report No. 05).Washington D.C., World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2614

- Fraser Institute (2017). Economic freedom. Retrieved from https://www.fraserinstitute.org/economic-freedom/dataset?geozone=world&page=dataset.

- Gómez-Herrera, E. (2013). Comparing alternative methods to estimate gravity models of bilateral trade. Empirical Economics, 44(3), 1087–1111. doi:10.1007/s00181-012-0576-2

- Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94 (1), 300–316. doi:10.1257/000282804322970814

- Heritage Foundation (2017). Index of economic freedom 2017. Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org/index/.

- Jacimovic, D., Mitrović, R. D., Bjelić, P., Tianping, K., & Rajkovic, M. (2018). The role of Chinese investments in the bilateral exports of new E.U. member states and Western Balkan countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1185–1197. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1456357

- Kapuria-Foreman, V. (2008). Economic freedom and foreign direct investment in developing countries. The Journal of Developing Areas, 41(1), 143–154. doi:10.1353/jda.2008.0024

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155. doi:10.1086/250042

- Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2017). Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800-2016. Center for Systemic Peace. Retrieved from http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

- Moran, T., Görg, H., Serič, A., & Krieger-Boden, C. (2018). Attracting FDI in middle-skilled supply chains. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 12(2018-26), 1–9. doi:10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2018-26

- Moussa, M., Çaha, H., & Karagöz, M. (2016). Review of economic freedom impact on FDI: New evidence from fragile and conflict countries. Procedia Economics and Finance, 38 (2016), 163–173. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30187-3

- Nocke, V., & Yeaple, S. (2008). An assignment theory of foreign direct investment. Review of Economic Studies, 75(2), 529–557. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00480.x

- Ostadi, H., & Ashja, S. (2014). The relationship between external debt and foreign direct investment in D8 member countries (1995-2011. ). WALIA Journal, 30(S3), 18–22. http://waliaj.com/archive/2014-2/special-issue-3-2014/

- Pearson, D., Nyonna, D., & Kim, K.-J. (2012). The relationship between economic freedom, state growth and foreign direct investment in US states. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(10), 140–146. doi:10.5539/ijef.v4n10p140

- Peres, M., Ameer, W., & Xu, H. (2018). The impact of institutional quality on foreign direct investment inflows: evidence for developed and developing countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 626–644. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1438906

- Prehn, S., Brümmer, B., & Glauben, T. (2016). Gravity model estimation: fixed effects vs. random intercept Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood. Applied Economics Letters, 23(11), 761–764. doi:10.1080/13504851.2015.1105916

- Richet, X. (2019). Geographical and Strategic Factors in Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Europe. Asian Economic Papers, 18(2), 102–119. doi:10.1162/asep_a_00700

- Sanfilippo, M. (2010). Chinese FDI to Africa: What is the nexus with foreign economic cooperation?. African Development Review, 22(S1), 599–614. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8268.2010.00261.x

- Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658. doi:10.1162/rest.88.4.641

- Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2011). Further simulation evidence on the performance of the poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Economics Letters, 112(2), 220–222. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2011.05.008

- Tinbergen, J. (1962). Shaping the World Economy: Suggestions for an International Economic Policy. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund.

- Voeten, E., Strezhnev, A., & Bailey, M. (2009). United Nations General Assembly voting data. Harvard Dataverse, V18. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/12379.

- Westerlund, J., & Wilhelmsson, F. (2011). Estimating the gravity model without gravity using panel data. Applied Economics, 43(6), 641–649. doi:10.1080/00036840802599784

- William, C. G., Agyapong, W. E., & Abass, A. (2013). Foreign direct investment and trade policy openness in sub-Saharan Africa (MPRA Working Paper No. 58074 Issued in October 2013). Retrived from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/58074/.

- World Bank (2017). World Development Indicators 2017. Washington, DC. © World Bank. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26447

- World Bank (2017). Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017 © World Bank Group. Retrieved from https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/worldwide-governance-indicators.

- Zhang, J., Jiang, J., & Zhou, C. (2014). Diplomacy and investment - the case of China. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 9(2), 216–235. doi:10.1108/IJoEM-09-2012-010

Appendix

The aggregate indicators in are derived from 16 single variables using principal component analysis that aim to reduce the dimensionality in data. It changes the data into new aggregate variables. Each principal component is essentially the weighted average of the variables included. The eigenvalues are the variances of the principal components. The first principal component has the maximum variance for any of the combinations. Similarly, in all cases, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (K.M.O.) of sampling adequacy is used to check for the appropriateness of the P.C.A.

Table A1. Sources and definition of variables.

Table A2. Principal component analysis.

(a) Doing business index

(b) Border and transport efficiency

(c) Political and governance index

Table A3. African countries included in the sample.