?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Education in entrepreneurship is a key factor in intentions to create companies. Given that adolescence is an ideal stage to acquire knowledge, secondary schools and universities are tasked with the challenge of offering educational programs. This study identifies potential entrepreneurs from among 897 secondary school’s students and analyzes their entrepreneurial skills in motivation, risk, dedication, empathetic and communication. Results indicate that there is a high percentage of potential entrepreneurs among secondary school and that entrepreneurship is not limited to a specific field, but rather it is recognized as a future employment option regardless of the studies students want to pursue.

1. Introduction

Secondary and higher education institutions play an important role in creating environments, activities, and education courses that enable the activation and consolidation of an entrepreneurial spirit in society. Since the beginning of the century, European institutions have stated their concern over the lack of entrepreneurial initiatives, as can be gathered from the ‘BEST Procedure’ report (2002) on education and training in enterprise spirit or the Green Paper on Entrepreneurship in Europe (2003). Measures to promote entrepreneurship include the ‘Guide to Building Entrepreneurial Mindsets and Skills in the European Union’ (2013) and the European Parliament Resolution on promoting youth entrepreneurship through education and training in 2015.

In fact, in the last few years, there have been a growing interest in the education system in offering education and training in entrepreneurial competences from the first stage of school to university, to educate citizens being know how to capture the opportunities of the need and social utility of new goods and services. Highlights, also, the interest in knowing the progress achieved and the impact of entrepreneurship education overall upon the education system and particular into the higher education (Edelman, Manolova, & Brush, Citation2008; European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, Citation2016; Nabi, Liñán, Fayolle, Krueger, & Walmsley, Citation2017; Rodríguez & Serrano, Citation2015).

Given that adolescence is an ideal stage to acquire knowledge about how to open a business and to develop a favorable attitude towards entrepreneurship (Peterman & Kennedy, Citation2003), secondary schools are tasked with the challenge of offering educational programs on entrepreneurship.

As the specialized literature points out, there are few research evidences about youth entrepreneurial activities, although there is a great demand from some economic sectors. This work aims to shed light on the attributes, skills and motivations of young people to start a successful business. It offers the possibilities to analyze the attributes and main trait of personalities of youthfulness influencing the entrepreneurial behavior.

According to conceptual framework of entrepreneurial readiness proposed by Olugbola (Citation2017), that considers four stage to business success, with several factors related to the ideas and markets; the motivation and determination; the resources and the abilities in a context of university student, this study is focus in one of the stage—motivation and determination-; which is the early stage in entrepreneurial competences generating from the first stage of school.

The main objective of this study is to identify potential entrepreneurs from among secondary school students and analyze their entrepreneurial skills in five relevant areas, such as motivation, attitude towards risk, dedication, empathetic thought, and communication.

It is significant to know these skills, to promote and develop them from the university or from other higher education centers, in case of continue with the learning and training beyond secondary school.

Research questions to be answered include: a) What is the proportion of secondary school students who state a clear entrepreneurial intention? b) Are there differences according to gender? According to field of study? c) What types of skills and capacities determine entrepreneurial intentions among secondary school students?

To try to assess the entrepreneurial capacities and skills of secondary school students (from 16 to 19 years old), a questionnaire was created with 31 questions. Using this method, the variables studied in this research include the field of knowledge the students would like to pursue when they finish their current studies; their assessment of entrepreneurship as a career opportunity; their attitude towards problems and decision making; their degree of commitment to tasks; their capacity for empathetic thought; their capacity to communicate with and relate to others. Given the profile of the survey takers, the majority of the questions were written taking the students’ academic environment into consideration. The survey was completed by secondary school students who attended the ‘International Student and Educational Opportunities Exhibit’ from March 2 to 6, 2016 in Madrid. A total of 897 valid questionnaires were obtained.

The results indicate that there is a high percentage of potential entrepreneurs among secondary school students, and that women have a greater predisposition to be entrepreneurs than men. Additionally, certain entrepreneurial attitudes related to motivation, dedication, and empathetic thought are more highly developed in women. Students who are planning to pursue university studies in health sciences, social and legal sciences, and engineering and architecture see the possibility of opening their own business as a future employment option. In terms of skills, empathetic thought is one of the most significant in terms of entrepreneurship.

This paper is divided into five sections. After the introduction, section two offers a brief review of the literature on education in entrepreneurship, focusing on the integration of entrepreneurship into the educational stages of the Spanish education system. Section three presents the methodology and source of the study. Finally, section four summarizes the main results found in the research.

2. Education in entrepreneurship: Background and literature review

There is no doubt that education and training are key elements for promoting people's entrepreneurial vocation, as they provide independence, autonomy, and self-confidence; they make people aware of professional opportunities; they allow them to expand their horizons, making them more capable of perceiving opportunities; and, finally, they provide knowledge that can be used to open new businesses and improve existing ones (Edelman et al., Citation2008, Do Paço, Matos, Raposo, Gouveia, & Dinis, Citation2015). Even more so in hostile and turbulent economic environments (McCarthy, Puffer, & Lamin, Citation2018).

Specialized education in entrepreneurship has a positive relationship with a person’s predisposition to establish a business in the future (Dutta, Li, & Merenda, Citation2011). Moreover, participation in entrepreneurship education programs increases the perception of the viability of establishing a new business, which further increases among those who had positive learning experiences (Sánchez-Escobedo, Díaz-Casero, Hernández-Mogollón, & Postigo-Jiménez, Citation2011).

The discussion, rather, is focused on what type of education is most suitable. There are problems related to linking entrepreneurial training exclusively to the creation of new companies and the management of said company, rather than relating training to ‘learning to be an entrepreneur.’ The focus is usually put on tangible and quantifiable results, like a business plan (Honig, Citation2004), rather than on aspects related to entrepreneurial skills, attributes, and behaviors, such as thinking linearly instead of thinking in a more complex, non-linear manner.

Thus, education in entrepreneurship should be conceived from a broader perspective and should include aspects that encourage flexibility, creativity, innovation for creating smart future and a predisposition to think conceptually and view changes as opportunities (Byabashaija & Katono, Citation2011; Lee & Trimi, Citation2018). It should also include general competences such as communication skills, teamwork, and ‘learning to learn’. In short, entrepreneurship education should offer knowledge and skills for employability and personal development.

The Nussbaum’s capabilities approach, a powerful political philosophy, sheds light about the current dilemma of centers of higher education, analyzing if their objective is to educate for profits or in contrast to educate for democracy (Sanz Ponce, Peris Cancio, & Escámez Sánchez, Citation2018).

Furthermore, the outcomes of entrepreneurial education are unclear. On the one hand, positive results are obtained from said education in terms of entrepreneurial intention and student perception of the success of creating a new business or their current business. Entrepreneurial potential emerges or is strengthened in students in contact with entrepreneurial activities; moreover, education focused on entrepreneurial activities facilitates the development of positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship as a professional option, improving the perception of students’ competences; even if they are not planning on opening a business, they benefit from entrepreneurial knowledge and skills (Cooper & Lucas, Citation2007; Souitaris, Zerbinati, & Al-Laham, Citation2007; Athayde, Citation2009; Kassean, Vanevenhoven, Liguori, & Winkel, Citation2015; Lima, Lopes, Nassif, & da Silva, Citation2015).

On the other hand, there are studies that find that entrepreneurship education programs have little or no impact on entrepreneurial intention and the perception of competences to open a business (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2009; Lima et al., Citation2015; Oosterbeek, van Praag, & Ijsselstein, Citation2010; Von Graevenitz, Harhoff, & Weber, Citation2010). Therefore, it has been suggested that entrepreneurship education is not necessarily a precondition for more entrepreneurs deciding to open businesses. The traditional way in which universities offer said entrepreneurship programs and the fact that they do not promote skills such as creativity, the recognition of opportunities, and problem solving could explain these results (Edelman et al., Citation2008; Lima et al., Citation2015; Pejic Bach, Aleksic, & Merkac-Skok, Citation2018).

2.1. Determining factors of entrepreneurship

In general, the entrepreneurship is determined by a three set of diverse factors: 1) personal characteristics of individual including socio demographics and personal trait; 2) economic environment including macroeconomic variables; and, 3) functioning of institutions and sociological variables including formal and informal institutions, including cultural values and social networks (Pejic Bach et al., Citation2018).

In general, personal attributes are the main cause of why some individuals decide to become actively involved in creating a business while others do not. Some authors indicate that talent and temperament are vital for entrepreneurs, and that talent can be improved through training programs (Harris & Gibson, Citation2008). Behavioral and psychological perspectives also allow for an analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intention (Do Paço et al., Citation2015). The behavioral perspective emphasizes that entrepreneurs are people who display entrepreneurial behavior regardless of their personal characteristics; furthermore, said behavior can be learned through formal and informal social processes (Dutta et al., Citation2011). Thus, the virtue of training and education programs in entrepreneurship is that they may influence capacities for entrepreneurship—and not personality traits—insofar as said programs are built around experienced-based learning.

Some psychological aspects are likely to influence the behavior of an entrepreneur of a future professional. These are, choice made under uncertainty and risk; decision-making; emotional score; incentives and decisions; creativity, choices and decisions (Bogdan, Meșter, & Matica, Citation2018).

2.1.1. Entrepreneurial intentions by gender

Beginning with the premise that environments provide different resources, opportunities, and support to women and men, it would follow that there are gender differences in how said environment affects men and women's entrepreneurial intention (Ud Din, Cheng, & Nazneen, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2009). Studies are divergent on this point; some show that women have high or low participation in entrepreneurial activity depending on the specific context of each country (Bosma, Citation2011). Other studies do not find significant differences in terms of personal factors, but do find significant differences in terms of motivation (De Martino & Barbato, Citation2003), underlining that women’s motivation to become entrepreneurs is linked to dissatisfaction with their current occupation and with the fact that they are looking to find a lifestyle that allows them to balance work and family life; they are less motivated by the factors of wealth creation and economic improvement (Brush, Citation1992; De Martino & Barbato, Citation2003; Ud Din et al., Citation2018).

It seems that men are more likely to think about creating a new company (Díaz-García & Jiménez-Moreno, Citation2010; Sánchez-Escobedo et al., Citation2011), although both genders recognize that to be successful, they must have certain qualities that are more typical of women. Men may have a greater propensity for entrepreneurial activities compared to women due to the development of attitudes towards entrepreneurship; and because said attitudes are formed as a result of past experiences and behaviors, and given that certain groups such as women have historically been less exposed to these activities, it is logical to think that they may not have developed these attitudes as much as men and may have a pessimistic outlook on the success of their business (Harris & Gibson, Citation2008).

2.1.2. Education in entrepreneurship for young people

If the data associated with behaviors are considered, such as those provided by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report (2017), the rate of entrepreneurial activity among young people (18 to 24 years old) is lower than among adults. In Spain, the percentage of entrepreneurs under 24 years old is barely 2.6%, while 6.1% of entrepreneurs are 35–44 years old. Therefore, age is a significant factor when explaining differences in behavior regarding entrepreneurial intention (Schott, Kew, & Cheraghi, Citation2015), whether it be due to the availability of financial resources or access to credit, social attitudes, or personal motivation.

Education focused on entrepreneurial skills from a young age (primary and secondary school) promotes the development of the personal and social skills needed for professional life, such as the ability to detect opportunities in the environment or to outline strategies. Moreover, the best period for encouraging a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship is adolescence (Peterman & Kennedy, Citation2003).

Analyzing the phenomenon of entrepreneurship among secondary school students implies focusing attention on entrepreneurial intention and not on entrepreneurial behavior. One of the first research projects that took this approach was that of Fayolle and Klandt (Citation2006). These authors employed the so-called theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) to explain entrepreneurial intention based on three concepts: attitude towards the behavior, subjective norms, and the perception of control over the behavior. Attitude is the degree to which an individual has an assessment (positive or negative) of a behavior or approach. Subjective norms refer to social influences (opinion of family, friends) and environmental factors perceived by the individual with regard to undertaking a certain behavior or not. The perception of control over the behavior means that the individual is capable of controlling a situation, conditioned by the presence of factors that can facilitate (or not) the implementation of a behavior.

Among young people, there have been different studies performed on different educational levels, such as primary, secondary, and higher education. In the case of some Latin American countries, there is a positive relationship between the creation of companies and the increase in enrollment in secondary studies and negative with respect to higher education (Jimenez, Matos, Palmero-Camara, & Ragland, Citation2017). The studies that analyze the entrepreneurial behavior of university students come to different conclusions about entrepreneurial intention, but with a common denominator: the fear of failure (Balaraman, Khan, Fleming, Nowicki, & Dan Lacey, Citation1996; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, Citation2000; Fayolle & Klandt, Citation2006; Guerrero et al., Citation2016; Harms, Citation2015). The data from the GUESS report demonstrates a positive relationship between the participation of university students in curricular programs associated with entrepreneurship and the development of new business initiatives (Morris, Shirokova, & Tsukasanova, Citation2017). For secondary school students, some studies have analyzed the effect of demographic and psychological variables on entrepreneurial intention, such as risk aversion or the need to display personal achievements (Dinis, Do Paço, Ferreira, Raposo, & Gouveia, Citation2013; Ferreira, Raposo, Gouveia Rodrigues, Dinis, & do Paço, Citation2012; Iglesias, Jambrino, Velasco, & Kokash, Citation2016; Marques, Ferreira, Gomes, & Gouveia, Citation2012). However, the various actions of the educational system over time aim to develop positive motivation towards the business person figure and entrepreneurial activity, modifying individual beliefs (Anderson & Jack, Citation2008).

Additionally, the literature on entrepreneurship analyzes the influence of the individual's field of study as a determining factor of being more or less prone to entrepreneurship. There is evidence suggesting that education influences entrepreneurial vocation, and therefore it could be expected that those fields of study in which, due to their nature, more emphasis is placed on entrepreneurship education programs would have higher rates of entrepreneurial intention. At the same time there are studies that question these findings; contrary to what was expected, male students from a sports school showed greater intentions of opening a business compared to the female students from a business school, thereby underlining that there are other factors in addition to education that can influence entrepreneurial intention (Do Paço et al., Citation2015).

Business students, who are involved in entrepreneurship training programs, generally have positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship (Harris & Gibson, Citation2008). Self-confidence and competency are likely strongly influenced by past positive experiences in the field of entrepreneurship. Male business students achieve higher scores in terms of personal control over the business and in the use of innovative methods in business activities.

2.2. Including entrepreneurship values in the Spanish education system

Given that the results analyzed in the empirical section have been applied in Spain, below is an outline of the process followed by institutions to include entrepreneurship values in the education system. In Spain, the legislature has recognized the importance of an entrepreneurial spirit as a necessary skill to meet future employment demands. In this case, entrepreneurship values were a part of the curriculum in all primary and secondary school courses and, more specifically, in elective courses.

The Organic Law on Improving Education Quality (LOMCE) 8/2013 of 9 December and Order ECD 65/2015 of 21 January, which describe the competences and contents of primary and secondary school education, maintain this cross-curricular nature, but introduce clear references to entrepreneurship in its competences. Thus, the competency autonomy and personal initiative is now called sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit.

This competency requires knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Therefore, in the different courses that comprise compulsory secondary education and bachillerato (the last two years of high school in Spain, for students intending to go to university), five basic capacities must be instilled: the capacity for creativity and innovation; the proactive capacity to manage projects; the capacity to assume and manage risks and uncertainty; the capacity to work independently and as part of a team; critical thinking and responsibility.

presents the way in which entrepreneurship values have been introduced in the different educational stages, according to the recommendations of Law 14/2013 of 27 September on support for entrepreneurs and their internationalization. Article 4 of this law establishes that the curricula for Primary Education, Compulsory Secondary Education, Bachillerato, and Vocational Training must incorporate objectives, competences, content, and evaluation criteria for education aimed at developing and strengthening entrepreneurial spirit, acquiring competences for creating and developing different types of companies, and for promoting equality of opportunities and respect for entrepreneurs and businesspeople, as well as business ethnics.

Table 1. Integrating entrepreneurship into the stages of the Spanish education system.

In Spain, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport analyze, continuously in depth, relevant data on policies, curriculum, results and impact of education for entrepreneurship, as well as gather information on training and support measures for teachers and good practices in this domain (Rodríguez & Serrano, Citation2015).

In the empirical study presented in this paper, the independent variable used is the perception of control over the behavior associated with the creation of a business project, which appears to be conditioned by a series of demographic and psychological variables and attitudes, which are necessary for entrepreneurship.

After reviewing the empirical evidence this work proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: The gender of the students is not a determining variable to explain the predisposition to the entrepreneurial activity.

H2: Students with preference to study engineering are more likely to start a business for reasons of opportunity.

H3: Communication and creativity skills are those that most characterize of the high school students with a clear entrepreneurial intention.

3. Methodology and data

To try to assess the entrepreneurial capacities and skills of secondary school students (from 16 to 19 years old), a questionnaire was created with 31 questions divided into thematic blocks, among personal skills, classroom skills, motivation, aptitude in facing risks, dedication, empathetic thought, and communication. Using this method, the variables studied in this research include the field of knowledge the students would like to pursue when they finish their current studies (arts and humanities, sciences, social and legal sciences, health sciences, and engineering and architecture); their assessment of entrepreneurship as a career opportunity; their attitude towards problems and decision making; their degree of commitment to tasks; their capacity for empathetic thought; and their capacity to communicate with and relate to others. To measure each of the skills associated with entrepreneurship, individuals answered a series of statements measured on a Likert scale of five values, from total disagreement to full agreement. For example, for the measurement of communication skills they answered aspects such as: they have ease and security to make presentations, they considerate themselves outgoing people or they have preference to work in teams. These statements have become dichotomous variables. Those statements in which the individuals have answered strongly or totally agree have been assigned the value 1, while the rest of the values of the scale have been assigned the value 0.

Given the profile of the survey takers, the majority of the questions were written taking the students’ academic environment into consideration. Thus, for example, to measure their capacity to communicate, they are asked if it is difficult for them to do presentations in class or to manage the group work in which they have participated. presents the thematic blocks and variables to be analyzed.

Table 2. Definition of dummy variables.

The survey was completed by secondary school students who attended the International Student and Educational Opportunities Exhibit from March 2 to 6, 2016 in Madrid. This exhibit offers information and guidance to students regarding different higher education opportunities in Spain, whether at universities or vocational training schools. A total of 897 valid questionnaire responses were obtained.

After performing a descriptive analysis, an estimation of the determinants for entrepreneurial intention was carried out. The model estimated is a discrete choice logit model, whose specification is as follows:

And given the values of the independent variables the probabilities that the dependent variable has the values 1 and 0 are:

where

represents entrepreneurial intention, which adopts the value of 1 in cases where the participant indicates the possibility of opening a business either because of opportunity or need and 0 if the opposite is true. The independent variables are represented by a set of aspects related to personal characteristics of individual including personal traits in areas like motivation, aptitude in facing risks, dedication, empathetic thought, communication, other personal skills, and classroom skills ().

The selection of the variables was made from the literature review, identifying those attributes that best characterized the areas referred to above that can influence entrepreneurial behavior. However, some of the variables may have limitations by not correctly capture the dimension or aspect considered. As for example the recognition of success and consistency in work as proxis of motivation, cannot reflect completely all facets or drivers of entrepreneurial motivation.

4. Results and discussion

With regard to the gender of the survey takers, the majority of the sample are women; 72.6% are women, with 27.3% men. In terms of the field of study they would like to pursue when they finish their current studies, 31.2% of the students want to study health sciences, 27.6% want to study social and legal sciences, 17.6% are interested in sciences, 12% choose arts and humanities, and 11.4% choose engineering and architecture.

In other words, the sample includes answers from all of the main areas of learning that students can pursue once they have completed their secondary education. Furthermore, 97.1% are currently studying Bachillerato, 1.8% are in Compulsory Secondary Education and the remaining 1.1% are studying a university degree.

The results show that between 53% and 56% of the secondary school students surveyed are potential entrepreneurs (), if we include both motivation due to need (economic motivation), in the first case, or opportunity (personal development), in the second case.

Table 3. Entrepreneurial intention (EI) by gender.

The motivation of a potential entrepreneur based on opportunity is defined by affirmative answers to the statement that ‘Creating a company would be a great personal challenge since they would get to put all of their skills into practice,’ while motivation based on need is defined by the group that said they agreed with the statement that ‘entrepreneurship would be a good option if employment opportunities were lacking.’ However, entrepreneurship as a solution to unemployment or as a way to facilitate balance between family and work life are motives that result in failure (Crecente, Garrido, & Ramón, Citation2014).

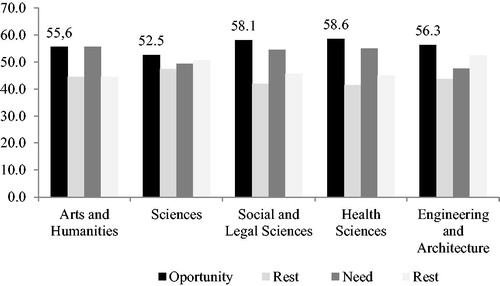

In the analyses, both indicators of entrepreneurial intention were considered; these two types of intention have been called ‘Potential entrepreneur for opportunity’ (PEO) and ‘Potential entrepreneur out of need’ (PEN). By gender, the results show that entrepreneurial intention—both for opportunity and need—is higher among women than men (). Additionally, by fields of knowledge, entrepreneurial potential—for opportunity and need—is distributed as follows: health sciences, social and legal sciences, engineering and architecture, arts and humanities, and, lastly, sciences ().

Analyzing the characteristics of PEOs and PENs compared to the rest of participants with regard to seven key aspects of entrepreneurship (), it can be noted that, within the aspects related to motivation, the advantages of potential entrepreneurs compared to the rest are minor; both groups like to receive recognition for their work when they've been successful and to share their achievements with others, because this pushes them to set new goals. Where the PEOs and PENs do have large advantages is in their consistency in work.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics, by entrepreneurial potential.

With regard to aptitude in facing risks, divergent results are obtained; on the one hand, planning out the most important things and adapting as the situation develops is the most highly valued statement by PEOs, as well as always trying to look at the positive side of things when facing problems. For PEOs, there is room for improvement in two key aspects for entrepreneurship: first, not being afraid of taking risks, and recognizing that making decisions means always facing uncontrollable aspects that must be accepted; and secondly, when faced with an unexpected problem, finding someone who knows about the topic to ask for advice and help in solving it. The PEN group also presents greater advantages with regard to having a positive outlook when facing problems; this group has room for improvement on three key aspects: planning and adaptation, risk tolerance, and looking for advice.

The field of dedication is an aspect in which the position of PEOs and PENs is clearly above the rest. Both their degree of commitment when they undertake a task that requires them to dedicate as much time as possible to it until they’ve reached their goals; as well as aspiring to be as much of a perfectionist as possible, using all of the time required to complete all of their obligations, are fields in which said group has a relative advantage.

Empathetic thought is another important skill for entrepreneurs. It can be seen that students classified as PEOs have more skills in this aspect compared to the rest of the sample. Given the possibility of starting a company or launching an improvement initiative, the most important aspect for them is detecting the needs of potential customers and finding out how to meet them. Moreover, once a new project has been launched, the most important thing is to make an effort every day to improve the product and attract new customers. This last aspect is also highly valued among students classified as PENs.

In the field of communication abilities, both PEOs and PENs perform better, as they believe that they are capable of clearly and confidently conveying their ideas in presentations; and, furthermore, that they are extroverted, charismatic people with communication skills and they like to relate to and openly communicate with others. However, when it comes to teamwork, it can be seen that said skill is not sufficiently developed in these two groups compared to the others and the mean, as a lower proportion of these groups say they feel comfortable working with people they don’t know and that they have the ability to lead the group.

With regard to other personal skills that influence entrepreneurial capacities, such as a) taking the initiative and getting to work quickly without waiting to be asked to do so; b) considering themselves to be very competitive people, in any environment (work, personal, social) and c) being curious and liking to learn new things; it can be seen that the PEOs have higher scores compared to the rest in terms of initiative and openness to learning; while PENs have greater advantages in the three skills described compared to the rest of the sample.

Lastly, with regard to classroom skills, it can be seen that PEOs have greater advantages in terms of communication with their classmates and creativity (measured through the ability to create an attractive CV), while there is room for improvement in terms of the ability to make public presentations. PENs receive lower scores compared to the other groups on the three aspects measured related to classroom skills.

Moreover, upon analyzing the aptitudes of both PEO and PEN female students, it can be seen that certain attitudes towards entrepreneurship are more highly developed in women as compared to men. In the case of PEOs, women have greater skills in the areas related to motivation due to social recognition of success, to aptitude in facing risks with regard to planning to undertake an initiative, in the area of dedication in the sense of perfectionism, and in the area of empathetic thought in terms of communication skills.

In the case of PENs, women stand out for having greater skills compared to the male PEN group than the female PEOs do compared to their male counterparts. They obtain higher scores in the area of aptitude in facing risks in terms of having a positive outlook when facing problems, and in the areas of dedication and empathetic thought. Furthermore, in communication skills, they stand out for clearly and confidently conveying their ideas, and in the area of personal skills, competitiveness and openness to learning are areas where they do particularly well. Lastly, it should be noted that they have greater competences in terms of classroom skills compared to the male PEN group.

5. Analysis of determinants of the intention to create a business

The results from the logit models to determine entrepreneurial potential for each of the two types of entrepreneurs (PEO and PEN), considering the entire sample (men and women) and including a gender dummy variable, are presented in . The results from the logit models to determine entrepreneurial potential according to the type of entrepreneur and gender are shown in .

Table 5. Determinants of entrepreneurial potential by type of entrepreneur.

Table 6. Determinants of entrepreneurial potential (type of entrepreneur and gender).

With regard to the gender variable, it is observed that it is statistically significant and has a negative impact on the entrepreneurial potential of PEOs (), which indicates that being a man does not necessarily determine the entrepreneurial intention of secondary and bachillerato students considered to be PEOs. The characteristics of having a positive outlook when facing problems, identifying customer needs, and being open to learning positively and significantly contribute to the entrepreneurial intention of PEOs. In the case of PENs, the traits consistency in work, initiative, and openness to learning have a positive influence on the probability of being an entrepreneur.

The odds ratios of becoming a male entrepreneur vary depending on the definition of potential entrepreneur and are only significant for the definition of PEO (0.73). A positive outlook when facing problems, empathy, and being open to learning increase the odds ratios of becoming an entrepreneur in accordance with the definition of PEO (1.4, 1.6, and 1.5 respectively). Moreover, consistency in work, initiative, and openness to learning increase the odds ratios of becoming an entrepreneur in accordance with the definition of PEN (1.7, 1.4, and 1.8 respectively).

It is noteworthy that the variables related to the area of classroom skills such as relationships with classmates, creativity and public speaking do not exert influence on either of them. measures of entrepreneurial intention.

The results of the logit models to determine entrepreneurial potential according to type of entrepreneur and gender (female PEO and male PEO, female PEN and male PEN) are presented in . The characteristics of identifying customer needs and being open to learning contribute positively and significantly to the entrepreneurial intention of female PEOs, while having a positive outlook when facing problems has a positive and significant influence on the probability of becoming a male PEO.

For female PENs, consistency in work, initiative, and openness to learning have a positive and significant influence on the probability of being entrepreneurs. In the case of male PENs, consistency in work and openness to learning also contribute to the likelihood of becoming an entrepreneur.

Furthermore, the odds ratios for identifying customer needs and being open to learning increase the probability of becoming entrepreneurs in the case of female PEOs (1.7 and 1.6), while just the odds ratio related to having a positive outlook when facing problems increases the probability of being a male PEO (with a value of 2.3). Finally, the odds ratios for consistency in work, initiative, and openness to learning (1.5, 1.5, and 1.7 respectively) increase the probability of becoming a female PEN; while consistency in work, a positive outlook when facing problems, and openness to learning increase the probability of being a male PEN (2.5, 0.6, and 2.2 respectively).

Again, the limitations in selected variables in certain ambits as communication and classroom skills, could explain the absence of statistical significance of the parameters of the estimations.

6. Implications and conclusion

The introduction of values associated with entrepreneurship in the education system has fostered the existence of a high percentage of potential entrepreneurs among secondary students. By gender, female students have a greater predisposition than male students to be entrepreneurs and they have further developed certain aptitudes involved in entrepreneurship, such as motivation, dedication, and empathetic thought. By field of knowledge, entrepreneurship is not limited to just the social sciences, but rather students recognize it as a future employment option regardless of the field they are interested in studying.

In terms of the most significant skills in potential entrepreneurs, of note are empathetic thought and communication skills, with confidence to convey their ideas in presentations. The most significant attitudes include the predisposition to act creatively, as well as the capacity for effort. However, deficiencies are detected with regard to the ability to work in a team, which reveals a large area for improvement in the learning process.

This awareness-raising process should be extended to the following phases of the education system, whether university or vocational training programs. Additionally, this entire awareness-raising process must be accompanied by greater participation of companies, entrepreneurs, and educators. The former should be included because they can provide an up-close view of what is happening in the real world; and the latter because they can transmit these values to students. Educators, regardless of their area of specialization, must be trained in entrepreneurship and how to teach it. If we want to respond to new social demands, we must make changes to teaching methodologies that promote solving complex tasks with innovation and creativity, such as project-based learning and service-learning.

Despite the methodological limitations, such as the selection of the variables and the analysis of a cross-section, the work provides elements to analyze those characteristics and personal traits that most influence the entrepreneurial intention of young people.

The future research lines that include deepening in determinants of youthfulness entrepreneurial behavior for example by area of study or sector of activity and the possibilities that high education institutions have to widen the entrepreneurial potential increasing the competences the entrepreneurs need to undertake a business.

It is particularly interesting to analyze the evolution (improvement or worsening) of perceptions of entrepreneurship with the transition from secondary education to university studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Anderson, A., & Jack, S. (2008). Role typologies for entrepreneurship education: The professional artisan? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(2), 259–273. doi:10.1108/14626000810871664

- Athayde, R. (2009). Measuring enterprise potential in young people. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 481–500. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00300.x

- Balaraman, P., Khan, M., Fleming, M., Nowicki, D., & Dan Lacey, J. (1996). Strategies for effective teaching: A handbook for teaching assistants. Madison: College of Engineering. www.teknologi pendidikan.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/strategies.pdf

- Bogdan, C., Meșter, I. T., & Matica, D. (2018). Insights into some psychological triggers that affect judgements, decision-making and accounting choices. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1289–1306. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1476169

- Bosma, N. (2011). Entrepreneurship, urbanization economies, and productivity of European regions. In Handbook of research on entrepreneurship and regional development: National and regional perspectives (pp. 107–132). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). Learning and transfer. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Brush, C. D. (1992). Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective, and future directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(4), 5–30. doi:10.1177/104225879201600401

- Byabashaija, W., & Katono, I. (2011). The impact of college entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention to start a business in Uganda. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 16(01), 127–144. doi:10.1142/S1084946711001768

- Cooper, S. Y., & Lucas, W. A. (2007). Developing entrepreneurial self-efficay and intentions: Lessons from two programmes. Paper Presented at ICSBWorld Conference, Turku.

- Crecente, F., Garrido, R., & Ramón, S. (2014). Educate and undertake. A methodology for emerging entrepreneurship at the university. In EDULEARN14 Proceedings (pp. 2744–2752). IATED.

- De Martino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 815–832. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00003-X

- Díaz-García, M. C., & Jiménez-Moreno, J. (2010). Entrepreneurial intention: The role of gender. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(3), 261–283. doi:10.1007/s11365-008-0103-2

- Dinis, A., Do Paço, A., Ferreira, J., Raposo, M., & Gouveia, R. (2013). Psychological characteristics and entrepreneurial intention among secondary students. Education + Training, 55(8/9), 763–780. doi:10.1108/ET-06-2013-0085

- Do Paço, A., Matos, J., Raposo, M., Gouveia, R., & Dinis, A. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions: Is education enough? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 57–75. doi:10.1007/s11365-013-0280-5

- Dutta, D. K., Li, J., & Merenda, M. (2011). Fostering entrepreneurship: Impact of specialization and diversity in education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 163–179. doi:10.1007/s11365-010-0151-2

- Edelman, L., Manolova, T., & Brush, C. (2008). Entrepreneurship education: Correspondence between practices of nascent entrepreneurs and textbook prescriptions for success. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7 (1), 56–70. doi:10.5465/amle.2008.31413862

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2016). La educación para el emprendimiento en los centros educativos en Europa. Informe de Eurydice. Luxemburgo: Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea.

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2009). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education: A methodology and three experiments from French engineering schools. In Gatewood, E.J. and Shaver, K.G. (Eds.), Handbook of university-wide entrepreneurship education (pp. 203–214). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Fayolle, A., & Klandt, H. (2006). Issues and newness in the field of entrepreneurship education: New lenses for new practical and academic questions. In Fayolle, A. (Ed.) International entrepreneurship education (pp. 1–17). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ferreira, J. J., Raposo, M. L., Gouveia Rodrigues, R., Dinis, A., & do Paço, A. (2012). A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioural approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 424–440. doi:10.1108/14626001211250144

- Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Ramos, A., Ruiz-Navarro, J., Neira, I., & Fernández-Laviada, A. (2016). Observatorio de Emprendimiento Universitario en España. Edición 2015–2016. Madrid: Crue Universidades Españolas-RedEmprendia-CISE.

- Harms, R. (2015). Self-regulated learning, team learning and project performance in entrepreneurship education: Learning in a lean startup environment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 100, 21–28. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.02.007

- Harris, M., & Gibson, S. (2008). Examining the entrepreneurial attitudes of US business students. Education + Training, 50 (7), 568–581. doi:10.1108/00400910810909036

- Honig, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: Toward a model of contingency-based business planning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3 (3), 258–273. doi:10.5465/amle.2004.14242112

- Iglesias, P., Jambrino, C., Velasco, A., & Kokash, H. (2016). Impact of entrepreneurship programmes on university srudents. Education + Training, 58 (2), 209–228. doi:10.1108/ET-01-2015-0004

- Jimenez, A., Matos, R., Palmero-Camara, C., & Ragland, D. (2017). Enrolment in education and entrepreneurship in Latin America: A multi-country study. European Journal of International Management, 11(3), 347–364. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2017.10004237

- Kassean, H., Vanevenhoven, J., Liguori, E., & Winkel, D. (2015). Entrepreneurship education: A need for reflection, real-world experience and action. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 21(5), 690–708. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-07-2014-0123

- Lee, S. M., & Trimi, S. (2018). Innovation for creating a smart future. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2016.11.001

- Lima, E., Lopes, R. M., Nassif, V., & da Silva, D. (2015). Opportunities to improve entrepreneurship education: Contributions considering Brazilian challenges. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 1033–1051. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12110

- Marques, C., Ferreira, J., Gomes, D., & Gouveia, R. (2012). Entrepreneurship education: How psychological, demographic and behavioural factors predict the entrepreneurial intention. Education + Training, 54(8/9), 657–672. doi:10.1108/00400911211274819

- McCarthy, D., Puffer, S., & Lamin, A. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation in a hostile and turbulent environment: Risk and innovativeness among successful Russian entrepreneurs. European Journal of International Management, 12(1–2), 191–221. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2018.089033

- Morris, M., Shirokova, G., & Tsukasanova, T. (2017). Student entrepreneurship and the university ecosystem: A multi-country empirical exploration. European Journal of International Management, 11 (1), 65–85. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2017.081251

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16 (2), 277–299. doi:10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- Olugbola, S. A. (2017). Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(3), 155–171. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2016.12.004

- Oosterbeek, H., van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54(3), 442–454. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002

- Pejic Bach, M., Aleksic, A., & Merkac-Skok, M. (2018). Examining determinants of entrepreneurial intentions in Slovenia: Applying the theory of planned behavior and an innovative cognitive style. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1453–1471. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1478321

- Peterman, N. E., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise education influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(2), 129–144. doi:10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00035.x

- Rodríguez, I. D., & Serrano, J. A. V. (2015). La educación para el emprendimiento en el Sistema educativo español. Año 2015. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Colección Eurydice España-Red.

- Sánchez-Escobedo, M. C., Díaz-Casero, J. C., Hernández-Mogollón, R., & Postigo-Jiménez, M. V. (2011). Perceptions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship. An analysis of gender among university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(4), 443–463. doi:10.1007/s11365-011-0200-5

- Sanz Ponce, R., Peris Cancio, J. A., & Escámez Sánchez, J. (2018). The capabilities approach and values of sustainability: Towards an inclusive pedagogy. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3, 76–81. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2017.12.008

- Schott, T., Kew, P., & Cheraghi, M. (2015). Future potential: A GEM Perspective on Youth Entrepreneurship 2015. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22 (4), 566–591. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

- Ud Din, N., Cheng, N., & Nazneen, S. (2018). Women’s skills and career advancement: A review of gender (in)equality in an accounting workplace. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1512–1525. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1496845

- Von Graevenitz, G., Harhoff, D., & Weber, R. (2010). The effects of entrepreneurship education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(1), 90–112. doi:10.1016/j.je

- Zhang, Z., Zyphur, M. J., Narayanan, J., Arvey, R. D., Chaturvedi, S., Avolio, B. J., … Larsson, G. (2009). The genetic basis of entrepreneurship: Effects of gender and personality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(2), 93–107. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.07.002