?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Female labour force participation (FLFP) stands among main gender equality issues in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Although making up about half of the total working-age population, less than one third of women is active. High female economic inactivity is argued to relate to the pertaining traditional views on gender roles in the society. This article investigates whether such views impact the activity of women. Furthermore, the article investigates whether perceptions of the existence of gender stereotypes on the labour market influences women’s economic activity. Finally, the article investigates whether differences of such an impact exist between young and adult women and how they are being manifested. The research model is based on a log-log regression analysis performed on a sample of 1,213 interviewed women through the 2017 wave of the National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions (NSCP-BiH). Our findings indicate that traditional views on women’s role in society act as an important moderator of woman’s economic activity, and hence, shape the overall labour environment and economic development in BiH. Although perceiving that the BiH labour market is biased towards men, women in BiH are not discouraged by such a stance when their labour market participation is considered.

1. Introduction

Gender equality leads towards growth in investments, productivity, human capital and income per capita, and decreases the level of violence during international disputes and crisis whereby leading towards more democratic and peaceful state of international behaviour (Lagerlof, Citation2003; Braunstein, Citation2011; Caprioli, Citation2003; Wu & Cheng, Citation2016). The importance of this evidence is stressed through placing gender equality as fifth sustainable development goal set by the United Nations (UN) in 2016 to transform our world. However, progress in its achievement cannot be accomplished overnight.

Although labour force participation may not be a matter of choice (Elson, Citation1999) or may even be desirable (Clark & Anker, Citation1993; Van Klaveren & Tijdens, Citation2012), women’s economic activity status pertains discouraging statistics in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). According to the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 2017, 51.1% of the total working age population in BiH are women, whereas less than one third of them are economically active. The remaining two thirds of the female population belong to the inactive group, defined as ‘all persons of 15 years of age or older who are not employed or did not take any actions to look for employment, including: pupils/students, pensioners, disabled for work, persons who perform only housework in their household and discouraged inactive persons’ (Agency for Statistics of BiH, Citation2017a). According to the statistics presented by the World Bank and International Labour Organization (ILO), BiH is ranked as the 165th country in the world when it comes to its women’s labour force participation rates in 2017 (35.2% as per ILO estimate). BiH’s neighbouring countries record better statistics, including Montenegro, North Macedonia, Croatia, Serbia and Slovenia. In particular, BiH has a lower women labour force participation rate than the European Union (EU) average (51.1%), Europe and Central Asia average (50.8%), or world average (48.7%) (ILO, 2018). Furthermore, Global Gender Gap Index for 2017, developed by the World Economic Forum, places BiH as 66th ranked country in the world according to the gender equality attainment (World Economic Forum, Citation2017). However, when comparing index sub-categories, BiH is the 116th country in the world out of 144 included in the analysis where economic participation and opportunities for women are considered (World Economic Forum, Citation2017). Due to such disappointing evidences, women in BiH are pushed towards marginalisation and an unenviable position within the society, which is, by many, characterised as patriarchal and traditional. A gender analysis of BiH conducted in 2016 confirmed that gender stereotypes, especially those nurtured by traditionally suitable roles of men and women in the society, continue to play an important moderator in undermining gender equality in politics, economics, culture, social and private life (USAID MEASURE-BiH, 2016). Moreover, the Analysis stresses that, although there is an increasing number of legislation addressing women’s subordinate roles, the implementation of these documents is lagging behind. However, at this point, there is no law governing nor fostering greater labour market participation of women, which is seen as one of the main gender equality issues in the country (USAID MEASURE-BiH, 2016).

This article investigates whether traditional views on gender roles in society impact the economic activity of women. Furthermore, the article investigates whether perception of the existence of gender stereotypes on the labour market influences women’s economic activity. Finally, the article investigates whether the differences of such an impact exist between young and adult women in BiH and how they are being manifested. As a result, the ollowing research hypotheses are defined:

H1: Women who believe men are responsible for earning are more likely to be economically inactive.

H2: There is a negative relationship between women’s economic activity status and perception that labour market in BiH is biased towards men.

We use data collected through 2017 National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions (NSCP-BiH)Footnote1 for the purpose of testing defined research hypotheses. Our research model is based on a log-log regression analysis performed on a sample of 1,213 interviewed women.

1.1. Women and men on the labour market

Many previous studies have been conducted so as to investigate the nature, influencing factors, motives, as well as consequences of women in labour force. Godlin (Citation1995) argues that female labour force participation (FLFP) is significantly influenced by their education level and social customs. In particular, women whose education improves, experience a decrease in routine housework and moved to paid work instead (Godlin, Citation1995; Ferrant & Thim, Citation2019). On the other hand however, cultural norms and societal prejudice against working women mediate the motivation and acceptability of their economic activity (Godlin, Citation1995; Hakim, Citation2000). Cultural norms and practices are widely identified as driving factors of the gender inequality that lead towards a subordinating role for women (Marcus & Haprer, 2015), sometimes also associated with religious beliefs that identify women’s roles through motherhood (Besamusca et al., Citation2015). Women living in religious groups that foster such restrictive gender roles are discouraged and consequently less likely to join the labour force (Psacharopoulos & Tzannatos, Citation1989; Clark et al., Citation1991; Besamusca et al., Citation2015). Generally, traditional family roles are associated with lower female economic activity since shaping an environment in which women tend to reduce the paid work in order to take care of their family and household. For example, 19.3% of women aged 20–64 in the EU27 region stressed that looking after children or being incapacitated were the main reasons for them staying outside the labour market in 2016. In addition, 12.3% of female respondents (20–64) declared the reason was other family or personal responsibilities (Matuszewska-Janica, Citation2018). Although the relation between the female economic activity rate and economic growth is considered to be U-shaped (Durant, 975; Psacharopoulos & Tzannatos, Citation1989; Godlin, Citation1995; Luci, Citation2009; Olivetti & Petrongolo, Citation2014; Lechman & Kaur, Citation2015; Besamusca et al., Citation2015), which generally means that low- and high-income countries record high FLFP, whereas middle-income countries, a group to which BiHFootnote2 belongs, have on average lower female economic activity rate; research conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) highlights that economic development does not automatically lead to gender equality in distributing unpaid work since restrictive gender norms still burden women with majority of household-related responsibilities (Ferrant & Thim, Citation2019). The report on Voices of Women Entrepreneurs in BiH (2008) highlights that demanding household and childcare responsibilities stand as one of the main factors forcing women to invest less in their economic activities (International Finance Corporation & MI-BOSPO, Citation2008). This refers equally to both formal and informal employment, highlighting again the subordinate role of women in the overall productive economy. The common agreement between men and women about the traditionally suitable and acceptable roles they should play within the society cultivates a gender gap in labour force participation, especially when stereotypical masculine roles are considered. Even today, the perception of men being the central role in protecting the family, faith, social or ethnic groups, and/or the country are persistent in BiH (USAID MEASURE-BiH, 2016).

However, cultural norms and societal beliefs are considered to only be part of the complicated puzzle that reflects women’s economic inactivity. In addition to these, discouraging labour market conditions are identified as one of the main factors driving women to stay/become inactive, either by delaying their entry into the labour market, increasing the time spent on education, or simply stepping out of the workforce (Mathew, Citation2015). Gender-based discrimination on the labour market, either positive or negative, refers to the unequal treatment, opportunities or outcomes of economically active men and women (ILO, 2017). Turturean et al. (Citation2013) discuss that gender-based discrimination on the labour market usually manifests itself through professional or wage discrimination. The former relates to difference in the accessibility to certain job position, while the latter reflects the gender wage gap (Turturean et al., Citation2013). One of the main drivers of these gaps was education, which is why countries all over the world invested their efforts in eliminating the education gap in order to provide a strong basis for reaching labour market equality (Ganguli et al., Citation2014). Even though most of these efforts were successful, highly-educated women still tend to leave the labour market, usually because they are discouraged by the wage gaps when compared to their male counterparts (Mathew, Citation2015). Saure and Zoabi (Citation2014) highlight that female labour supply increases as the gender wage gap closes. However, it is broadly discussed that lower pay provided to working mothers stands as one of the main pillars of the wage gaps (ILO, 2018). In particular, mother are paid less than non-mothers, either because of the reduced working time, labour market interruptions, employment in a more family-friendly jobs which are usually paid less, stereotypical hiring, or firm-related procedures for promoting employees that negatively affect careers of mothers.

BiH’s Gender Action Plans (GAP) covering the periods from 2006 to 2011 and 2013 to 2017 emphasised that the main causes behind women’s inability to achieve equality in the labour market include the prevalence of traditional notions of women’s role in society; leaving a job to care for children; a higher demand for a younger workforce; earlier retirement age for women compared to men; lack of special vocational guidance programmes for women; men tend to be preferred during hiring; and widespread low education levels and access to information among women from rural areas (GAP for BiH, 2006–Citation2011, 2013–2017).

2. Methodology

2.1. Data source and sample

This article is based on the data obtained from the 2017 NSCP-BiHFootnote3 The NSCP-BiH is conducted by USAID Monitoring and Evaluation Support Activity (MEASURE-BiH) on an annual basis for the purpose of collecting information on BiH citizens’ general experience of and perceptions towards a broad range of topics, including governance, corruption, civic participation, rule of law, interethnic trust, and social inclusion.

The 2017 NSCP-BiH was conducted in October and November 2017 using a nationally representative sample of civilian, noninstitutionalized (18+) BiH residents. The survey was administered by professional data collection company through face-to-face computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). As a result, interviews with 3,084 individuals were completed. Out of those, 56.1% are women. This article focuses solely on the female sample. Since addressing FLFP, women with disabilities whose disability is the main reason for not working; pupils/students/in specialisation; retired women; and those who refused to provide an answer on questions related to their status in employment are excluded from the analysis. As a result, the research is based on a sample of total 1,213 women interviewed through the NSCP-BiH.

2.2. Research model and variables

The research model is based on the activity status on the labour market as the dependent variable and investigates which factors affect this dependent variable and how. Independent variables are grouped as following:

Age

Level of education obtained

Perception of gender-based discrimination on the labour market

Traditional views on role of women in household and labour market

Settlement

Entity

Ethnicity

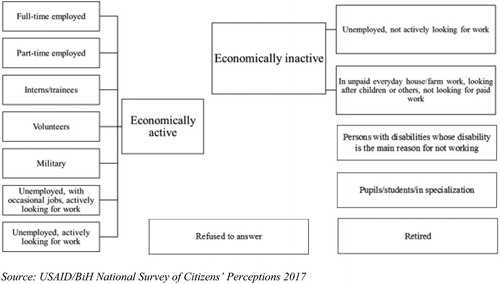

Activity status on the labour market divides the survey respondents in two groups, those who are economically active and those who are not. Economically active respondents are defined as those who reported to be in full-time employment; in part-time employment; interns/trainees; volunteers; unemployed, with occasional jobs, actively looking for work; unemployed, actively looking for work; and military (recruit). Economically inactive respondents, as per definition, include those who reported to be: unemployed, not actively looking for work; in unpaid everyday house/farm work, looking after children or others, not looking for paid work; persons with disabilities whose disability is the main reason for not working; pupils/students/in specialisation; and the retired. However, in order to obtain valid responses on defined research questions, several categories were dropped from the economically inactive category during the data analysis, namely: persons with disabilities whose disability is the main reason for not working; pupils/students/in specialisation; and retired persons. The reason for dropping these categories from the analysis is that corresponding citizens are forced to be inactive rather than being excluded from the labour market by choice. Respondents who refused to provide an answer on their activity status were also dropped from the analysis. illustrates the disaggregation of respondents per activity status used in the analysis:

Figure 1. Disaggregation of respondents per activity status.

Source: USAID/BiH National Survey of Citizens’ Perceptions 2017.

Age is the first independent variable used in the analysis. According to the Article 4 of the Youth Law of the FBiH (Official Gazette of the FBiH, No. 35/10), and Article 2 of the Law on Organization of the Youth of RS (Official Gazette of the RS, No. 98/04 and 119/08), young people refer to people aged 15 to 30 years. As the NSCP-BiH sample of respondents includes only those older than 18, this article considers youth as population aged 18 to 30. All respondents older than 30 are regarded as adults in the analysis.

Level of education obtained refers to the highest level of schooling respondents received, and is divided into three groups: (1) below secondary school; (2) secondary school; and (3) above secondary school. Below secondary school category includes the respondents who chose following answers: no education, uncompleted primary education, and primary school. Secondary school category includes the respondents who said to have completed secondary school. Finally, above secondary school category includes respondents who chose post-secondary school specialisation, high school and first grade of faculty, or advanced school/faculty/academy/university as their answer to the question on highest level of completed education.

Perception of BiH labour market being biased towards men (existence of gender-based discrimination on the labour market) is the third independent variable used in the analysis. The aim of the variable is to identify women that are discouraged to work or look for a job as men are given better opportunities on the labour market, including better jobs, higher salaries, etc. The variable is created based on two questions from the NSCP-BiH 2017 – ‘In your experience, are BiH employers more likely to hire men or women?’ and ‘Who do you think has more positions of power in business?’ The variable identifies respondents who chose men on at least one of the above questions.

Traditional views on role of women in household and labour market is the fourth independent variable used in the analysis. Variable is based on respondents’ agreement or disagreement with the following statement ‘It is a man’s responsibility to make earnings, a woman’s responsibility is to look after the home and the family’. The range of possible agreement with the statement spread on a 7-point Likert scale from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’. Strongly agree, Agree, and Somewhat agree responses were counted as holding the traditional view on gender roles in the society. As a result, we differentiate respondents who agree that women should work and those who disagree with such a statement.

In addition to the described independent variables, several demographic characteristics are also used in the analysis, including type of settlement in which the respondent lives, entity in which the respondent resides, and ethnicity to which respondent belongs. These variables are added to the model under the assumption that there might be differences in findings across different groups of respondents they represent, and specifically, due to BiH’s political background that surfaced as an important determinant in similar analyses and research:

Type of settlement disaggregates survey respondents, as per those living in rural areas and those living in urban areas of the country.

In accordance with the General Framework Agreement for Peace, BiH’s territory is divided into two entities and the Brcko District. Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) holds 51% of country’s territory, while Republika Srpska (RS) holds 49%. All respondents from the NSCP-BiH included in this research are disaggregated as per the entity or district in which they reside.

While responding to the NSCP-BiH, BiH citizens declared the ethnicity they belong to. In this research we distinguish five ethnic groups: Bosniaks, Croats, Serbs, Other ethnicity and Does not declare.

3. Data analysis and results

An overview of selected research model variables is provided in . The probability of differences in means between adult and young women are tested by using the t-test analysis whereby the following levels of statistical significance are used: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Table 1. Overview of research model variables.

According to , 44% of women interviewed through the NSCP-BiH are inactive. In particular, the analysis shows that every second adult and every fifth young woman in BiH are excluded from the labour market and are not seeking paid work. In addition, about one third of females think that women should not work since their responsibility is to take care of the household while men should make money. Such a stance is more likely to be held by adult women than by their young counterparts, 36.9% and 30.3%, respectively. Additionally, most women believe BiH employers are more likely to hire a man compared to a woman and that men hold more positions of power in the business in BiH When disaggregated by age, young women in BiH are less likely to believe that the BiH labour market is biased towards men, however no statistically significant difference between the perception of adult and young women could be confirmed.

The analysis also shows that most women in BiH have a secondary school diploma. However, only 17.2% of them are highly-educated citizens. Young women are more likely to finish university studies, specifically 31.6%, compared to 12.3% of adult women.

isolates the inactive women from the overall sample and presents their education attainment, household income, perception about women’s role in the society and gender stereotypes on the labour market, and selected demography features.

Table 2. Overview of research model variables across inactive respondents.

According to the t-tests results presented in the , most inactive women are those with below secondary education and living in households whose net monthly income does not exceed 1,000 BAM. Although most inactive adult women are those with primary school only, more than one third of inactive young women obtained a secondary school diploma. This is not surprising considering the statistics on secondary school enrolment reported by the Agency for Statistics of BiH (Citation2017b). Furthermore, only one fourth of inactive women in BiH believes that BiH labour marked is not biased towards men, while more than one third hold the opinion that a woman’s responsibility is to take care of the household while men should earn. These opinions are almost equally held by both young and adult women.

presents log-log regression analysis results when women’s inactivity in the labour market is investigated. A list of independent variables is provided in the first column. The statistically significant impact of those variables on the women activity status is marked with asterisks (*), whereby the following levels of statistical significance are used: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. P values that record 100% statistical significance are marked in grey.

Table 3. Results of the log-log regression analysis.

The strongest determinants of women’s likelihood for being active/inactive on the labour market include: age, education level obtained, type of settlement in which she lives in, and her perception about the gender roles in the household/labour market.

In particular, the results of the regression analysis show that women’s likelihood of being inactive rises with age and decreases with education, whereby having a secondary school diploma decreases woman’s probability of being inactive by 136 percentage points, and obtaining above secondary school education by 340 percentage points. A strong relationship is found to exist between women’s activity status and type of settlement in which they live in. More precisely, women living in urban parts of the country are less likely to be inactive on the labour market when compared to women in the rural areas.

As shown by the regression analysis conducted, an important predictor of woman’s inactivity is also her view on gender roles within the household and on the labour market. In particular, the NSCP-BiH respondents were asked whether they agree or disagree with the statement that ‘it is a man’s responsibility to make earnings, a woman’s responsibility is to look after the home and the family.’ Referring to strongly agree, agree, and somewhat agree response options to their views on gender roles within the household and on the labour market, we found that women holding this stance are 37 percentage points more likely to be inactive compared to women not sharing their traditional views. Hence, we can confirm the first research hypothesis stating that ‘Women who believe men are responsible for making money are more likely to be economically inactive regardless of their age or obtained education level.’

However, we found no evidence that the perception of the BiH labour market being biased towards men affects women’s activity status. As a result, we reject the second research hypothesis which states that ‘there is a negative relationship between women’s economic activity status and perception that the labour market in BiH is biased towards men regardless of women’s age or obtained education level’.

In order to provide a deeper insight into the women’s labour force participation and factors influencing women’s economic activity, we further tested the research hypothesis for young and adult women separately. The aim of such analysis is to investigate whether traditional views on women’s role in the society, as well as the perception that the BiH labour market favours men, has the same impact on the economic activity of women less and women above 30 years of age. Again, a statistically significant impact of independent variables on women’s activity status is marked with asterisks (*), whereby the following levels of statistical significance are used: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. P values that record 100% statistical significance are also marked in grey.

As shown in , young women from 21 to 24 years of age are more likely to be inactive compared to women aged 18 to 20 (omitted category). However, no statistical significance has been found with regard to such a statement. On the other hand, it is statistically confirmed that young women from 25 to 30 years of age are 104.1 percentage points more likely to be inactive compared to young women from 18 to 20 years of age. Furthermore, young woman’s likelihood of being inactive decreases with education, whereby having a secondary school diploma and above secondary school education decrease the probability of being inactive by 187.6 and 400.6 percentage points, respectively. As for the overall women category, young women living in urban areas are less likely to be inactive compared to those living in rural settlements. More precisely, young women living in urban settlements are 87.6 percentage points less likely to be inactive. Moreover, residing in RS decreases the likelihood of young women being inactive by 223.2 percentage points compared to young women residing in FBiH (the omitted category).

Table 4. Results of log-log regression analysis when young women are observed.

Even though our analysis showed that traditional views on gender roles in the household and on the labour market lead towards higher inactive rate of women in BiH, we could not confirm this statement when only young women are taken into account. Finally, although every second young women believes that men are given more positions of power in business and BiH employers are more likely to hire a man compared to a woman, there is no evidence that such perception affects young woman’s likelihood of being inactive.

The below presented results () of the regression analysis show that adult women’s likelihood of being inactive increases with age. In particular, women 41 to 50 years of age are 52.3 percentage points more likely to be economically inactive when compared to women 31 to 40 years of age (omitted category). The same findings apply to women aged 51 to 60, and above 60 years of age (68.3 and 140.2 percentage points, respectively). The same as for the young women, their level of education is the strongest determinant of activity status among adult women. Higher education decreases the likelihood of women being economically inactive by 105.2 and 304.3 percentage points in case of obtaining secondary and above secondary school education, respectively.

Table 5. Results of log-log regression analysis when adult women are observed.

Finally, women’s stance on traditional role they should play within the society in terms of being responsible for the household and not for making earnings increases their likelihood for being inactive by 49.6 percentage points compared to women who disagree with such statement. This relationship has proven to be strongly significant.

4. Discussion

This article confirms the severity of the women’s economic inactivity in BiH Every second women older than 30 and every fifth women younger than 30 are excluded from the labour market and do not seek paid employment. Although labour force participation may be desirable (Clark & Anker, Citation1993; Van Klaveren & Tijdens, Citation2012), such a rationale is hardly likely to justify BiH labour market participation statistics since half of women who have reported to be inactive through the 2017 wave of the NSCP-BiH live in households whose net monthly income does not exceed average net salary recorded in BiH in 2017 (Agency for Statistics of BiH, Citation2017a) while the average consumer basket in the same period amounted to 1,850 BAM (Agency for Statistics of BiH, Citation2017b).

The performed analysis shows that the strongest determinants of women’s activity status on the labour market in BiH include their age, education level obtained, type of settlement in which they live in, but also perception about whether women should work or stay at home and take care of the household. In particular, women are more likely to be economically inactive if they are more than 30 years of age, less educated, and living in rural areas. Such findings coincide with previous research focused on the impact of education on a decrease in routine housework and shifting to paid work (Godlin, Citation1995; Ferrant & Thim, Citation2019). The structure of unemployed women in BiH, which shows that more than half of inactive women are those with primary school diploma while 1.69% of them are those with university education, further supports the conclusion of education being a strong weapon in fight against women’s economic inactivity. Hence, investing in women’s education should be recognised and further fostered by BiH authorities in addressing country’s labour market issues and economic development.

Traditional views on the role of women in society, both in household and on the labour market, persist among the female population in BiH The article confirms that social patterns, such as men should earn and women should take care of the household (Godlin, Citation1995; Hakim, Citation2000), stand as one of the main drivers of women’s economic inactivity in BiH Specifically, women holding traditional views on family roles are by 37.4 percentage points more likely to stay out of the labour market compared to women disagreeing with such a view. Moreover, almost every second inactive women thinks that she should not work. Having in mind the tendency to reduce the paid work for the sake of family responsibilities, many researchers investigated the nature of men and women being employed on a part-time basis. Elias (1990), Gash and Cooke (Citation2010) confirm that part-time employment is much more common for women, while Jaumotte (2003) discusses the potential of part-time work to increase women’s participation in the labour market while leaving more space to take care of the household work. Part-time employment, however, is not that common in BiH – at least according to the data obtained from the 2017 NSCP-BiH which shows that only 7.6% of employed women interviewed are part-time employees. Hence, considering the arrangement of part-time working hours might be a good starting point for BiH government officials when considering steps towards decreasing women’s economic inactivity.

Although women do perceive that gender-based stereotypes exist on the BiH labour market, these neither encourage nor discourage their active participation – regardless of their age. Even though no evidence on negative impact of the unequal treatment of men and women on the labour market was found, both professional and wage discrimination patterns (Turturean et al., Citation2013) should be further investigated in the BiH context to enable shaping an effective approach that will address the issue and contribute to increasing the overall state of gender equity in the country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Retrieved from http://measurebih.com/national-survey-of-citizens-perceptions

2 According to the World Bank definition, upper-middle income economies are those who’s GNI per capita ranges between $3,956 and $12,235. In 2018, BiH’s GNI amounted $5,690 per capita. More information retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=BA

3 Retrieved from http://measurebih.com/national-survey-of-citizens-perceptions

References

- Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2017a). Labour force survey. Retrieved June 29, 2018 http://www.bhas.ba/tematskibilteni/TB_ARS%202017_BS_ENG.pdf

- Agency for Statistics of BiH. (2017b). Women and Men in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved August 20, 2018 from http://www.bhas.ba/tematskibilteni/FAM_00_2017_TB_0_BS.pdf

- Besamusca, J., Tijdens, K., Keune, M., & Steinmetz, S. (2015). Working women worldwide. Age effects in female labor force participation in 117 countries. World Development, 74, 123–141. Voldoi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.015

- Braunstein, E. (2011). Gender equality and economic growth. Fe Dergi, 3(2), 54–67.

- Caprioli, M. (2003). Gender equality and state aggression: The impact of domestic gender equality on state first use of force. International Interactions, 29(3), 195–214. doi:10.1080/03050620304595

- Clark, R. L., & Anker, R. (1993). Cross-national analysis of labor force participation of older men and women. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 41(3), 489–512.

- Clark, F. A., Parham, D., Carlson, M. E., Frank, G., Jackson, J., Pierce, D., Wolfe, R. J., & Zemke, R. (1991). Occupational science: Academic innovation in the service of occupational therapy’s future. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(4), 300–310. doi:10.5014/ajot.45.4.300

- Elson, D. (1999). Labor Markets as Gendered Institutions: Equality, Efficiency and Empowerment Issues. World Development, 27(3), 611–627.

- Ferrant, G., & Thim, A. (2019, February). Measuring women’s economic empowerment: Time use data and gender inequality. OECD Development Policy Papers No. 16.

- Ganguli, I., Viarengo, M., & Hausmann, R. (2014). Closing the gender gap in education: What is the state of gaps in labor force participation for women, wives and mothers? International Labour Review, 153(2), 173–207. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2014.00007.x

- Gash, V., & Cooke, L. P. (2010). Wives’ part-time employment and marital stability in Great Britain, West Germany and the United States. Sociology, 44(6), 1091–1108.

- Gender Action Plan for BiH (GAP for BiH). (2006–2011). Official Gazette of BiH no. 41/09.

- Gender Action Plan for BiH (GAP for BiH). (2013–2017). Official Gazette of BiH no. 98/13.

- Godlin, C. (1995). The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. Shultz TP investment in women’s human capital and economic development. University of Chicago Press. pp. 61–90.

- Hakim, C. (2000). Research design: Successful designs for social and economic research. Social Research Today (2nd Rev.). Routledge.

- International Finance Corporation, MI-BOSPO. (2008, May). Voices of women entrepreneurs in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved August 20, 2018 http://policycafe.rs/documents/financial/research-and-publications/A2F-for-women/Voices%20of%20Women%20Entrepreneurs%20in%20BiH.pdf

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2018). ILOSTAT database. Labour force participation rate, female (& of female population ages 15+). Modeled ILO estimate. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS

- Jaumotte, F. (2003). Female Labour Force Participation: Past Trends and Main Determinants in OECD Countries. OECD Working Paper No. 376.

- Lagerlof, N. P. (2003). Gender equality and long-run growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(4), 403–426.

- Lechman, E., & Kaur, H. (2015). Economic growth and female labor force participation: Verifying the U-feminization hypothesis. New evidence for 162 countries over the period 1990–2012. Economics & Sociology, 8(1), 246–257. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-1/19

- Luci, A. (2009). Female labour market participation and economic growth. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 4(2/3), 97. doi:10.1504/IJISD.2009.028065

- Marcus, R., & Harper, C. (2015). How do gender norms change. Overseas Development Institute.

- Mathew, S. S. (2015). Falling female labour force participation in Kerala: Empirical evidence of discouragement? International Labour Review, 154(4), 497–518. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2015.00251.x

- Matuszewska-Janica, A. (2018). Women’s economic inactivity and age. Analysis of the situation in Poland and the EU. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis Folia Oeconomica, 5(338), 57–80. doi:10.18778/0208-6018.338.04

- Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2014). Gender gaps across countries and skills: Demand, supply and the industry structure. Review of Economic Dynamics, 17(4), 842–859. doi:10.1016/j.red.2014.03.001

- Psacharopoulos, G., & Tzannatos, Z. (1989). Female labor force participation: An international perspective. The World Bank Research Observer, 4(2), 187–201. doi:10.1093/wbro/4.2.187

- Saure, P., & Zoabi, H. (2014). International trade, the gender wage gap and female labor force participation. Journal of Development Economics, 111, 17–33. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.07.003

- Turturean, C. I., Chirila, C., & Chirila, V. (2013). Gender discrimination on the Romanian labor market: Myth or reality? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 92, 960–967. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.784

- Van Klaveren, M., & Tijdens, K. (2012). Empowering Women in Work in Developing Countries (Ist Ed.). UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- World Economic Forum. (2017). The global gender gap report. Retrieved August 24, 2018 from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2017.pdf

- Wu, R., & Cheng, X. (2016). Gender equality in the workplace: The effect of gender equality on productivity growth among the Chilean manufacturers. The Journal of Developing Areas, 50(1), 257–274. doi:10.1353/jda.2016.0001