Abstract

Teaching is among other things an emotional endeavour. Being emotionally competent has tacitly become a prerequisite for the teaching profession, thus raising the question of teachers’ actual emotional competence as well as manners of acquiring these skills. This paper aims to discuss how emotions relate to the teaching profession and also provides results of a small scale study conducted on a sample of 144 teachers from secondary schools in the City of Rijeka regarding the teachers’ assessment of their emotional competence. The results of the study point to overall high assessments of teachers’ emotional competence which is an encouraging result but could also point to the idea Hargreaves (Citation2000) introduced, which entails the notion that expressing positive emotions and being emotionally competent has become a moral commitment and a professional standard for the teachers which makes them feel obliged to live up to those standards.

1. Introduction

Teachers’ work seems to get more and more complex. Apart from having to comply with the formal aspects of their everyday work within and outside of their classrooms, their values and perceptions of what it means to be a good teacher as well as emotions influence their judgement during the process of teaching (Van Kan et al., Citation2013). Indeed, teaching encompasses more than just instruction, it entails creating relationships with students which presupposes both parties getting emotionally involved (Bahia et al., Citation2013; Madalinska-Michalak, Citation2015; Șoitu et al., 2011). When pondering over the subject of what construes an efficient and expert teacher, one needs to consider their professional skills but also their personal characteristics. Arnon and Reichel (Citation2007) in their research on the perceptions of what makes an ideal teacher from the perspective of students of educational sciences and the beginning teachers, revealed that the perception of an ideal teacher entails someone with academic knowledge, who has a social mission, focuses on individual development and whose personality is in the centre of their teaching. The results also show that among the aforementioned characteristics, teachers’ personality traits are considered very important with regard to ideal teaching, especially in the context of being emphatic and attentive. Personality traits, as is visible from the aforementioned example, are often connected with emotions and emotional intelligence (Vesely et al., Citation2013).

When it comes to emotions in the educational practice, there has recently been an increase in the body of research present in different cultural and social contexts (Arnon & Reichel, Citation2007; Fried, Citation2011; Hargreaves, Citation2000; Sutton, Citation2004; Triliva & Poulou, Citation2006; Vesely et al., Citation2013; Yin, Citation2015). Researchers also dealt with and presented concepts such as emotional intelligence (Salovey & Mayer, Citation1990), emotional competence (Saarni, Citation1999), emotional literacy (Goleman, Citation1997), emotional labour (Hochschild, Citation1983) and emotional regulation (Sutton, Citation2004). In the national context there is also a slight increase in the research related to emotional competence of educators in pre-school institutions and schools (Frančešević & Sindik, Citation2014; Karalić & Sindik, Citation2016; Sindik, Citation2010). However, the focus of the research seems to be mostly on teachers in the lower levels of education while there is a visible lack of research in this area in terms of secondary school teachers. Therefore, this paper aims to discuss about how emotions relate to the teaching profession and will also provide results of a small scale study conducted on a sample of 144 teachers in Croatian secondary schools in the City of Rijeka regarding the teachers’ assessment of their emotional competence.

2. Review of theory and existing literature

Although the concept of emotional intelligence was first introduced almost thirty years ago (Salovey & Mayer, Citation1990), there is still no consensus on the term nor is it clear whether we are talking about an ability or a group of competencies. Salovey and Mayer (Citation1990, p. 189) asserted that ‘emotional intelligence is the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action’. The term was then popularized by Goleman (Citation1997, p. 34) in his book Emotional Intelligence – Why is it more important than IQ? He stated that emotional intelligence entails ‘the ability to recognize our feelings and those of others, to motivate ourselves and to manage our inner emotions as well as those regarding others.’ In 1997 (p. 22) Mayer and Salovey revisited the former definition of emotional intelligence and offered a more comprehensive one by stating that ‘emotional intelligence involves the ability to perceive accurately, appraise and express emotion; the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth’.

In this paper we opted for operationalisation of the concept of emotional intelligence proposed by Chabot and Chabot (Citation2004). The authors state that emotional intelligence is a collection of competencies which allow an individual to: identify one’s own emotions and those of others; accurately express one’s own emotions and help others express theirs; understand one’s own emotions and those of others; manage one’s own emotions and adapt to those of others; use one’s own emotions and skills peculiar to emotional intelligence in various areas of one’s life to be able to better communicate, make good decisions, maintain good interpersonal relations etc. (Chabot & Chabot, Citation2004, p. 68) Specifically, when it comes to the competency of identifying one’s own emotions and those of others, the authors state that the focus is on identifying nonverbal expressions and physiological changes but also on being able to discern the real from the mimicked emotions, which may pose a particular challenge. Expressing emotions and helping others to express theirs, entails the ability to verbalize one’s emotions and empathize with others in order to help them verbalize their own emotions. The authors go on to say that understanding one’s own and others’ emotions includes the former competencies (recognizing and expressing emotions), but also goes beyond them. This competency entails a person being able to understand the subtleties of emotionally charged words as well as to establish links between an emotion and its trigger. This allows a person to understand complex emotions and the transition between emotions (for instance how sadness can transit into aggressiveness). The authors conclude that managing emotions and adapting to those of others means being able to intervene on each of the emotional components (nonverbal expressions, physiological reactions, behavioural reactions, cognition and feelings) while using emotions and emotional competencies entails acting in accordance with all the previously mentioned competencies in order to nurture and improve all the relationships we have (Chabot & Chabot, Citation2004). Possessing all the mentioned competencies makes a person emotionally intelligent. However, in this paper, we opted to use the term emotionally competent because we took into account two important notions. The first one is Mayer and Salovey (Citation1997) assertion that emotional competence is focused on knowledge and skills one can achieve in order to adequately function in different situations and that they tend to be more focused on the educational process and not on psychological abilities. In this context, it is visible that Chabot and Chabot (Citation2004) propose that educators can learn and develop the mentioned competencies in order to enhance their teaching. The second notion is Saarni’s (Citation1999) idea that emotional competence entails the role of the self and individual values, the role of moral disposition and personal integrity but also the role of developmental history, that is, ‘our culture’s beliefs, attitudes and assumptions’. This is important because being a teacher means abiding by rules, norms and values which arise from the idea of what it means to be a good teacher in a particular cultural and social context. In line with that, the idea of a good teacher in the national but also wider (European) cultural and social context, as has been mentioned earlier, involves being focused on academic success of the pupils as well as their emotional wellbeing.

Teachers realize and acknowledge the importance of pupils acquiring and developing social and emotional competencies in terms of forming relationships in general but also in the context of academic success (Bahia et al., Citation2013; Triliva & Poulou, Citation2006). In addition, teachers also perceive their role in teaching social and emotional competencies as a ‘prerequisite to reinforcing and enhancing the skills and competencies of their students’ (Triliva & Poulou, Citation2006, p. 328). However, Hargreaves (Citation2000, p. 813) asserts that the negative aspect of emphasizing emotions in teaching is the possibility of ‘indulgence and diversion’ as well as creating a welfarist culture where achievements and goals become peripheral. Another important issue that Hargreaves (Citation2000) puts forward is that positive emotions such as caring and enthusiasm are considered to be a moral commitment and a professional standard which can then lead to teachers masking their emotions in order to sustain that idea. In this context it is important to introduce the concept of emotional labour which was first noted by Hochschild (Citation1983) in service jobs. The author presented the terms surface acting (faking emotions to display professionally acceptable emotions), deep acting (trying to change real emotions by using cognitive techniques in order for them to comply with the professionally acceptable emotions) and emotional consonance (naturally expressing emotions that are appropriate for a certain situation). It seems that there is a significant inclination among teachers to hide negative emotions and display positive emotions because the profession requires it. Hochschild (Citation1983), as well as more recently, Näring et al. (Citation2006) noted that expressing emotions which are not in accordance with the experienced emotions can lead to stress and burnout. Specifically, using surface acting can in long term lead to emotional depletion and exhaustion (Näring et al., 2006; Ghanizadeh & Royaei, Citation2015). On the other hand, the increase in the use of deep acting and naturally felt emotions causes a decrease in emotional depletion and teacher burnout (Ghanizadeh & Royaei, Citation2015; Näring et al., Citation2006; Yin, Citation2015). When it comes to a connection between emotional competence and emotional labour, Yin (Citation2015) in the study on the effect of teachers’ emotional labour has on teacher satisfaction indicated that emotionally competent teachers are more likely to perceive emotional demands of teaching and are therefore inclined to resort to deep acting and expression of the naturally felt emotions. Näring et al. (Citation2006) however, in their research also showed that the emotionally competent teachers may also resort to masking their real emotions, that is, surface acting. This could lead to a conclusion that although emotional competence decreases teacher burnout, even emotionally competent teachers are not entirely devoid of experiencing emotional depletion.

It is evident that emotional labour strategies serve as a potential protection system for teachers in terms of teacher burnout, however, the above review also shows that the aim should be to develop teachers’ emotional competencies as well as educate them to harmonize their authentic feelings as much as possible with the professional demands and standards so as not to experience demotivation, emotional depletion and exhaustion. The small scale study conducted for the purpose of this paper is the first step in examining the level of secondary school teachers’ emotional competence in the national context and determining what it actually means to be an emotionally competent teacher.

3. Research aim and hypotheses

The aim of this study was to examine secondary school teachers’ self-perceptions regarding the indicators of emotional competence.

The research is based on the assumption that there are no significant differences in self-perception of emotional competence between secondary teachers in grammar schools and vocational schools as well as regarding the variables of sex and age of the teachers.

4. Research sample

The research was conducted using a survey questionnaire on a convenience sample of 144 teachers from six secondary schools in Rijeka, three of which are grammar schools, while the other three are vocational schools. The sample did not include teachers from Art Schools since there are only two of such schools in Rijeka. Out of a total of 144 teachers, 98 are from vocational schools (N = 98) and 46 from grammar schools (N = 46) and 121 of the teachers are female (N = 121) while 22 teachers are male (N = 22).

5. Research methodology

The questionnaire used was retrieved from Chabot and Chabot (Citation2004, p. 28) and adapted for a survey research by adding independent variables of sex, age and type of school. The questionnaire contains 36 items i.e. positive statements in 4 categories: 1. Communication, 2. Motivation, 3. Adaptability and 4. Self- management. Each category has 9 positive statements. The Communication scale consists of 9 items (α = 0.818), the motivation scale consists of 9 items (α = 0.885), the Adaptability scale consists of 9 items (α = 0.849) and the Self-management scale consists of 9 items (α = 0.851).

The teachers assessed the degree of frequency for each situation described by a statement on the Likert scale. The degree of frequency was assessed from 1 – completely disagree to 6 – strongly agree.

Data analysis was conducted via a statistical program for Social Sciences SPSS (v.24.0). The methods used were: univariate analysis: frequency, percentages, measures of central tendency, measures of variability and bivariate analysis: t-test for independent samples with the Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances and analysis of variance for independent samples. Statistical significance was tested on the risk level of p < 0,05.

In order to conduct the survey, the researchers obtained a written consent from the ethical board of the Faculty for Humanities and Social Sciences. A written consent was also given by the school principals in order to be able to conduct the survey in school. The survey was anonymous.

6. Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics shows that the overall results cluster around the upper values of the Likert scale which indicates that all teachers perceive themselves to be highly emotionally competent (). A potential reason for that occurrence is that the study was conducted on a voluntary basis, and all the teachers were informed on the subject of the study, which may have motivated the teachers who are already confident with their emotional skills to participate in the study. Another possible reason for such high assessments is the dilemma Hargreaves (Citation2000) introduced, which entails the notion that expressing positive emotions and being emotionally competent has become a moral commitment and a professional standard for the teachers, so consequently the teachers deem it necessary to present themselves in a light which satisfies those standards and use the earlier described emotional labour strategies. Bearing in mind that emotional labour can cause burnout in the teaching profession, there is a need to express concern regarding the possibility that the participants were inclined to highly assess their emotional competence so as not to be portrayed unprofessional.

Table 1. Overall descriptive statistics.

An independent sample t-test was conducted to determine the differences in self-assessments between grammar school teachers and vocational school teachers as well as the differences related to the independent variable of sex. The t-test was conducted for each category which entails 9 positive statements. The statistically significant items are presented in the order of appearance in the questionnaire.

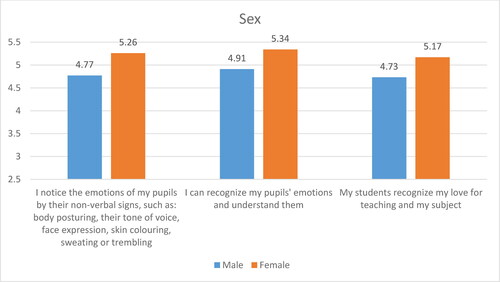

In the first category Communication there are no statistically significant differences between the teachers from different schools. However, there are two statistically significant items related to the independent variable of sex. As is visible from and , there is a statistically significant difference regarding the item I notice the emotions of my pupils by their non-verbal signs, such as: body posturing, their tone of voice, face expressions, skin colouring, sweating or trembling between male (M = 4,77, DS = 0,922) and female teachers (M = 5,26, DS = 0,680); t(141)=-2,941, p = 0,004. These results indicate that the female teachers perceive themselves as better at noticing their pupils’ emotions through non-verbal communication then men. The effect size is small (η2 = 0,057) and indicates that only 5,7% of the variance of noticing emotions by non- verbal signs can be related to the variable of sex. Another statistically significant item in this category is I can recognize my pupils’ emotions and understand them. The results regarding this item indicate that female teachers perceive themselves to be more competent in recognizing and understanding their pupils’ emotions (M = 5,34, SD = 0,653) then male teachers (M = 4,91, SD = 0,868); t(141) =-2,691, p = 0,008. The effect size is small (η2 = 0,048) and indicates that only 4,8% of the variance of recognizing and understanding the pupils’ emotions can be related to the variable of sex. The research on male and female aptitude to decipher emotions on the basis of non-verbal signs is inconsistent, however these results are in line with the findings that females have greater aptitude in recognizing emotions of others by non-verbal signs (Gregorić et al., Citation2014; Simão et al., Citation2008).

Table 2. Statistically significant items in all categories.

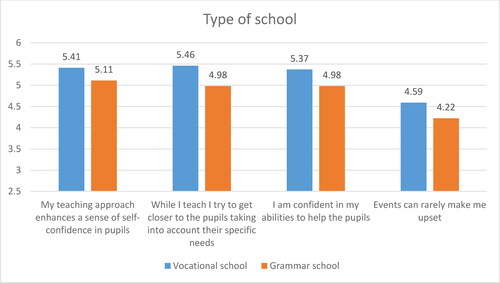

By observing the statistically significant items in the category Motivation ( and and ) it is visible that there is a statistically significant difference regarding the item My approach in teaching enhances a sense of self-confidence in pupils between the teachers from vocational schools (M = 5,41, SD = 0,671) and teachers from grammar schools (M = 5,11, SD = 0,767); t(142)=2,384, p = 0,018. The effect size is small (η2 = 0,037) and indicates that only 3,7% of the variance of the assessment on using an approach which enhances a sense of self-confidence can be related to the variable type of school. These results suggest that the teachers from vocational schools perceive their approach in teaching enhances a sense of self-confidence in pupils more than the teachers from grammar schools. Even though both the assessments made by vocational teachers and grammar school teachers are fairly high, vocational teachers have a stronger sense of enhancing self-confidence in their pupils. The aim of vocational education is to qualify pupils for their future work, therefore, the practical segment of their classes is emphasized which creates a strong sense of vocational identity in pupils (Bruijn, Citation2012). This could be connected to the vocational teachers’ notion of building self-confidence in their pupils. Nonetheless, the results also point to a small effect size and even though there is a statistically significant difference between the variables, only 3, 7% of the variance can be accounted for by the independent variable of type of school. When turning to the independent variable of sex in the same category, there is a statistically significant difference regarding the item My students recognize my love for teaching and my subject between male (M = 4,73, SD = 0,935) and female teachers (M = 5,17, SD = 0,771), t(141)=-2,414, p = 0,017. The effect size is small (η2 = 0,035) and indicates that only 3,5% of the variance of the assessment on pupils’ recognition of teachers’ love for teaching and subject can be related to the variable of sex. The results show that the female teachers feel their pupils recognize their love for teaching and subject more that male teachers do. According to Gregorić et al. (2012) women tend to be more emotionally expressive then men, which could be one of the reasons for their aptitude in deciphering emotions of others. Therefore, one could infer that the female teachers, being prone to emotional expressions regarding teaching and their subject as well as having an aptitude for recognizing their pupils’ emotions, perceive that their students notice their love for teaching and the subject.

Graph 2. Results of the independent samples t-tests regarding the independent variable type of school.

In the category Adaptibility ( and ) there is a statistically significant difference regarding the item While I teach I try to get closer to the pupils taking into account their specific needs between vocational teachers (M = 5,46, SD = 0,629) and grammar school teachers (M = 4,98, SD = 1,105); t(142)=3,319, p = 0,01. The effect size is medium (η2 = 0,071) and indicates that 7,1% of the variance of the assessment regarding getting closer to students and taking into account their specific needs can be related to the variable type of school. The results indicate that the teachers from vocational schools seem to be more prone to considering pupils’ special needs when teaching than the teachers in grammar schools. When referring to specific needs in the aforementioned statement it is possible that the teachers from vocational schools take into account the pupils with special needs or disabilities. This is explained by the fact that according to the data from the Bureau of Statistics from 2014 there is a total of 35 pupils with special needs who are integrated in grammar schools, while 387 pupils with special needs are integrated in technical and related schools and 1634 of them in industrial and crafts schools. In line with the above stated, it can be concluded that vocational teachers seem to associate ‘specific needs’ with ‘special needs and disabilities’ and could therefore be more prone to have higher assessments of this item. There are no statistically significant items in this category regarding the independent variable of sex.

In the last category Self-management ( and ) there is a statistically significant difference regarding the item I am confident in my abilities to help the pupils between the vocational school teachers (M = 5,37, SD = 0,632) and the grammar school teachers (M = 4,98, SD = 0,802); t(142)=3,152, p = 0,002. The effect size is medium (η2 = 0,065) and indicates that 6,5% of the variance of the assessment regarding teachers’ confidence in their abilities to help students can be related to the variable type of school. The vocational school teachers perceive themselves as being more confident in their abilities to help their students than their colleagues in grammar schools. This result can once more be related the fact that vocational teachers could be more susceptible to have higher assessments of items related to helping pupils due to their common involvement and interaction with the students with special needs and disabilities. Additionally, Köpsén (Citation2014) found that vocational teachers, due to lesser motivation and engagement of their students, feel they need to help the students in terms of their academic achievements as well as life in general. In that context, the vocational teachers emphasized their parent like role in the relationship with their students which could explain their higher assessment of this item.

Another item with a statistically significant difference in this category is Events can rarely make me upset. Vocational school teachers perceive that they are less prone to be upset by different events (M = 4,59, SD = 0,906) than the grammar school teachers (M = 4,22, SD = 1,009); t(142)=2,229, p = 0,027. The effect size is small (η2 = 0,033) and indicates that 3,3% of the variance of the assessment regarding getting upset by events can be related to the variable type of school. This result is also consistent with the aforementioned notion that it is more challenging to motivate and engage students in vocational schools, and that vocational teachers deal with a lot of diversity when it comes to their pupils’ competencies. This could lead to vocational teachers being more used to extraordinary situations with their students, as well as them being less prone to get upset by different events. However, it should also be noted that the effect size is small and even though there is a statistically significant difference, only 3.3% of the variance of the mentioned variable can be accounted for by the independent variable of type of school. There are no statistically significant items in this category regarding the independent variable of sex.

7. Conclusion

Taking into consideration both the theoretical discussion and the empirical data it should be stated that recognizing, expressing and understanding one’s own and others’ emotions are indispensable skills for the teaching profession today. Teachers are required to manage their students’ challenges in terms of motivation, abilities, personal backgrounds, which presupposes emotional activity (Bahia et al., Citation2013) and it is therefore important to equip them with the skills which will facilitate their day to day practice. It is also important to mention that the cultural context as well as the subject teachers teach should be taken into account due to the fact that they can play an important role when considering teachers ‘emotions (Sutton & Wheatley, Citation2003). Research shows that teachers acknowledge the importance of emotions in terms of transferring knowledge because they feel students are more motivated if teachers use positive emotions in their teaching. They also emphasize the importance of regulating emotions in the context of creating good emotional climate in the classroom (Bahia et al., Citation2013; Fried, Citation2011; Nizielski et al., Citation2012). Emotional regulation is a significant part of emotional competence, however, using some of the mentioned emotional labour strategies can be a possible pitfall for teachers who have not acquired emotional skills to deal with the various challenges they experience in their work, but still have the awareness of the professional standards expected of them.

Although the conclusions drawn from this empirical study cannot be generalized (a representative sample on a national level is required for that), the results can be indicative for reflexion on the topic of teachers’ emotional competence as well as the differences noted between vocational school and grammar school teachers and female and male teachers. We are hence inclined to note some of the significant results of this study. The results indicate that the vocational teachers assessed themselves to be more competent in terms of enhancing their pupils’ self-confidence when they teach, that they try to get closer to their pupils by taking into account their specific needs as well as being more confident in their abilities to help students. They also ascertain that they are not inclined to get upset by different events in comparison with their colleagues from grammar school. These results may point to the difference in circumstances in which these teachers work, both in terms of integration of students with special needs and disabilities (which is a far more common occurrence in vocational schools in Croatia), as well as the notion of the parent like behaviour of vocational teachers which Köpsén (Citation2014) noted in her research. The results in terms of the differences among the participants in the context of their sex are in line with some of the mentioned studies conducted on that topic (Gregorić et al., Citation2014; Kret & de Gelder, Citation2012; Simão et al., Citation2008), that is, the results revealed that the female teachers perceive themselves as more competent in terms of recognizing and understanding their pupils’ emotions and deciphering their non-verbal signs then men. The female teachers also assessed that their pupils recognize their love for teaching and their subject more than their male colleagues. These results raise additional questions and point to a need for further research in terms of the contextual differences between vocational schools and grammar schools but also among different vocational schools. For instance, if the context of vocational schools (especially industrial and craft schools) is more demanding in terms of pupils needs, should teacher training programmes for teachers who work there be more focused on acquiring and developing emotional competencies (bearing also in mind the varieties in the profile of teachers working in vocational schools)? Additionally, further research is needed in terms of the implications of the perceived differences between female and male teachers in terms of their emotional competence. Lastly, there is the issue of the prevailing high self-assessments visible in this study, which could, as has been said, point to socially desirable answers due to the notion that being emotionally competent has become a professional standard for teachers. These and other issues are closely connected with the question of teacher education in terms of emotional competence. There are no formal lifelong programmes that deal with acquiring emotional competencies, and professional development courses on the topic are scarce. In the international context Madalinska-Michalak (Citation2015) reported teachers’ experiences on the usefulness of The Teacher Emotional Competence pilot training program and indicated that teachers are aware of the necessity to develop emotional competencies but also emphasize the lack of such education in their initial training as well as in professional development possibilities.

Whether schools should focus on emotional development within the curricula of different subjects or within teachers’ pedagogical approach, without specific programmes (which calls for a certain change in the educational paradigm) or should training programmes for teachers be established, remains another open question. This topic can therefore no longer be neglected, especially when taking into account the growing dissatisfaction among teachers in the national and international context regarding their workload, challenges in dealing with the pupils, parents as well as other significant stakeholders within and outside the school context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arnon, S., & Reichel, N. (2007). Who is the ideal teacher? am i? Similarity and difference in perception of students of education regarding the qualities of a good teacher and of their own qualities as teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 13(5), 441–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600701561653

- Bahia, S., Freire, I., Amaral, A., & Estrela, M. T. (2013). The emotional dimension of teaching in a group of portuguese teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 19(3), 275–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.754160

- Bruijn, E. (2012). Teaching in innovative vocational education in the netherlands. Teachers and Teaching, 18(6), 637–653.

- Chabot, D., & Chabot, M. (2004). Emocionalna pedagogija. Osjećati kako bi se učilo - Kako uključiti emocionalnu inteligenciju u vaše poučavanje. [Emotional Pedagogy: To feel in order to learn – Incorporating Emotional Intelligence in your teaching strategies]. Educa.

- Frančešević, D., & Sindik, J. (2014). Odnos doživljaja sagorijevanja u radu, emocionalne kompetencije i obilježja posla odgajateljica predškolske djece [Relationship of burnout experience, emotional competences and job characteristics of preschool educators.]. Acta Iadertina, 11(1), 21. doi:https://doi.org/10.15291/ai.1272

- Fried, L. (2011). Teaching teachers about emotion regulation in the classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n3.1

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Royaei, N. (2015). Emotional facet of language teaching: Emotion regulation and emotional labour strategies as predictors of teacher burnout. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(2), 139–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/22040552.2015.1113847

- Goleman, D. (1997). Emocionalna inteligencija. Zašto može biti važnija od kvocijenta inteligencije [Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ]. Mozaik knjiga.

- Gregorić, B., Barbir, L., Ćelić,., Ilakovac, V., Hercigonja-Szekeres, M., Perković Kovačević, M., Frencl, M., & Heffer, M. (2014). Recognition of facial expressions in men and women. Medicina Fluminensis, 50(4), 454–461.

- Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed Emotions: Teachers’ Perceptions on Their Interactions with Students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(8), 811–826. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California Press.

- Karalić, Z., & Sindik, J. (2016). Razlike u socijalnim vještinama i kompetenciji prosvjetnih radnika u školama i dječjim vrtićima u odnosu na odabrane socio-demografske varijable [Differences in social skills and competences of educators in schools and kindergartens in relation to selected socio-demographic variables]. Acta Iadertina, 13(1), 19–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.15291/ai.1284

- Köpsén, S. (2014). How vocational teachers describe their vocational teacher identity. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 66(2), 194–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2014.894554

- Kret, M. E, & de Gelder, B. (2012). A review on sex differences in processing emotions. Neuropsychologia, 50(7), 1211–1221.

- Madalinska-Michalak, J. (2015). Developing emotional competence for teaching. Croatian Journal of Education - Hrvatski Časopis za Odgoj i Obrazovanje, 17(0), 71–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v17i0.1581

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. (pp. 3–34). Harper Collins.

- Näring, G., Briët, M., & Brouwers, A. (2006). Beyond Demand-control: Emotional Labour and Symptoms of Burnout in Teachers. Work & Stress, 20(4), 303–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601065182

- Nizielski, S., Hallum, S., Lopes, P. N., & Schütz, A. (2012). Attention to student needs mediates the relationship between teacher emotional intelligence and student misconduct in the classroom. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(4), 320–329. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912449439

- Saarni, C. (1999). A skill-based model of emotional competence: A developmental perspective. Paper Presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Albuquerque, 15–18 April. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED430678.pdf

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211.

- Simão, C., Justo, M. G., Martins, A. T. (2008). Recognizing Facial Expressions of Social Emotions: Do Males and Females Differ? ResearchGate on 2 October 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235705531

- Sindik, J. (2010). Povezanost emocionalne kompetencije te mašte i empatije odgojitelja sa stavovima o darovitoj djeci [Relation between educator’s emotional competence, imagination and empathy with attitudes about gifted children]. Život i Škola, 24(2), 65–90.

- Şoitu, L., Rusu, C., & Panaite, O. (2011). Emotional competences of educational practices. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology, 2(2011), 25–34.

- Sutton, R. E. (2004). Emotional regulation goals and strategies of teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 7(4), 379–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-004-4229-y

- Sutton, R. E., & Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers’ emotions and teaching: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4), 327–358.

- Triliva, S., & Poulou, M. (2006). Greek teachers’ understandings and constructions of what constitutes social and emotional learning. School Psychology International, 27(3), 315–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306067303

- Van Kan, C., Ponte, P., & Verloop, N. (2013). How do teachers legitimize their classroom interactions in terms of educational values and ideals?. Teachers and Teaching, 19(6), 610–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.827452

- Vesely, A. K., Saklofske, D. H., & Leschied, A. D. W. (2013). Teachers-the vital resource:the contribution of emotional intelligence to teacher efficacy and well-being. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 71–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468855

- Yin, H. (2015). The effect of teachers’ emotional labour on teaching satisfaction: moderation of emotional intelligence. Teachers and Teaching, 21(7), 789–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995482