?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The tendency to leave and the actual number of people leaving Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has been increasing in the last few years. We investigate the main determinants of people leaving BiH, with special focus on youth. Using the newest available data from USAID’s National Survey of Citizens Perceptions from 2017, we investigate this issue by using probit regressions. Attitudes and perceptions related to emigration from BiH are compared between two groups – youth up to the age of 30 and the rest of respondents. The analysis includes socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, their sentiment and satisfaction with life conditions, public services and government. The results imply that young respondents (under the age of 30) are more likely to consider leaving the country than older ones (above the age of 30). The results also show a significant positive effect of dissatisfaction with public services and high level of corruption on tendency to leave the country. The estimation of interaction effects imply that corruption is more prominent reason for emigration among youth than older respondents. Hence, the main issues which should be addressed to stop the trend of emigration are the improvement in the quality of public services and reduction in corruption.

1. Introduction

Research and discussions related to migration and especially migration of youth in Europe has been put in the spotlight in the last decade with the outbreak of global financial crisis (GFC) and hence economic crisis of 2008. Previous research related to migration in the European Union (EU) analysed the effects that EU enlargement and GFC had on migration (Fassmann & Hintermann, Citation1998; Kahanec & Zimmermann, Citation2010; Otrachshenko & Popova, Citation2014). The outcome of GFC was the growth in unemployment rates and especially youth unemployment rates since 2008 which in turn increased academic interest in the topic related to youth and migration in the EU. In the Western Balkan (WB) region, which BiH belongs to, the situation is somewhat different. Even though youth migration and migration of the working population in the WB countries have been identified as a serious issue and therefore put in media spotlight especially in the last few years, to the best of our knowledge, little academic research has been conducted. There is no reliable estimate of BiH citizens living abroad since this estimate varies depending on data sources. The World Bank estimates that 44.5 per cent of BiH citizens live abroad whereas Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Citation2018) estimate that 56.6 per cent of BiH citizens live abroad. High numbers of BiH citizens living abroad could be explained by migration from BiH during and right after the end of the war in BiH (1992–1995), but latest available data indicates that this percentage is not stagnant since people (and especially young people) are continuously leaving the country. According to the most recent Balkan Barometer (Citation2017) survey which is conducted annually, about half of current BiH residents would like to leave the country and work abroad. Balkan Barometer (across time) also reveals that the number of young people (ages 18–29) who wish to leave BiH (and South and Eastern European region) has been increasing over time.

In this paper we examine the main determinants of emigration from BiH, with a special focus on youth, by using USAID’s National Citizens Perceptions Survey of 2017. After brief literature review, an official emigration data for BiH is analysed with some alarming results. The probit analysis includes socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, their sentiment and satisfaction with their life conditions, public services and government. After developing the model, the empirical analysis is conducted, and results discussed. Based on the results in the final section policy recommendations of what could be done to prevent young people leaving BiH are given.

2. Literature review

Literature that investigates migration and youth migration has become intensified in the last decade with the outbreak of GFC. However, academic research on economics of migration and interest in reasons to why people emigrate is more than century old and can be found in works of Ravenstein (Citation1876, Citation1885) and Lee (Citation1966). In the analysis of economics of migration, both Ravenstein (Citation1876, Citation1885) and Lee (Citation1966) define a set of incentives and obstacles to migrate defining them as a set of push (‘unbearable or threatening conditions in the home country’) and pull (incentives in the host countries) factors (Kowalska & Strielkowski, Citation2013, p. 344). In the works of Hagen-Zanker (Citation2008) or Williams et al. (Citation2018), migration theories and factors affecting migration are grouped depending on the level they focus on: macro, meso and micro factors. Based on the work of Massey (Citation1990, Citation1999), Hagen-Zanker (Citation2008) focuses on macro, meso and micro-level theories of migration providing a summary of migration causes and perpetuation. Williams et al. (Citation2018) also analyse factors affecting migration grouped as macro, meso and micro-level factors. Most recent research on macro-level factors affecting migration reveals a set of economic (for example data on aggregate migration trends or financial reasons) and non-economic factors (for example health, crime, corruption, etc). In meso-level theories of migration and factors affecting migration, a set of social networks or social ties (Hagen-Zanker, Citation2008; Williams et al., Citation2018) are analysed. This is especially important in the examination of youth propensity to migrate since works of Cairns and Smyth (Citation2011) conclude that young people with intentions to migrate are significantly more likely to have siblings or friends who live abroad. However, analysis of Van Dalen and Henkens (Citation2012) or Cairns (Citation2014) indicate that the social ties such as family relationships can act as both stimulating and discouraging factors to migration. The analysis of micro theories of migration (Hagen-Zanker, Citation2008) and micro factors (Williams et al., Citation2018) affecting migration reveal that out of macro, meso and micro factors, the most numerous group of factors are micro factors. Williams et al. (Citation2018) group micro factors into three groups: socio-economic, demographic and psychosocial or personality (for example, sex, educational background, marital status, self-efficacy, sensation-seeking traits, etc.). Van Mol (Citation2016) provides similar grouping of micro level factors. Academic research also indicates that all macro, meso and micro factors are inter-correlated and very complex. Hence, factors affecting migration are multi-dimensional and include social, psychological, structural and educational factors regardless of the grouping methodology.

Previous literature also reviews other means and methods of approaching the issues related to youth and migration. In terms of comprehensiveness of academic research, migration and youth migration has mostly been assessed by using various survey methods. Williams et al. (Citation2018) state that up to date, there is no comprehensive single migration survey conducted. Research is mostly survey-based and includes analysis of single countries (for example Van Dalen and Henkens (Citation2012) for the Netherlands) or a group of countries (for example Otrachshenko & Popova, Citation2014 for Central and Eastern European countries and Western-European countries or Van Mol (Citation2016) for all EU member states). In a single country or cross-country surveys, different groups of population have been targeted and include entire working population (Van Dalen & Henkens, Citation2012), focus solely on youth (up to age of 30,Footnote1 Agadjanian et al., Citation2008; Van Mol, Citation2016) or only among students (for example Cairns, Citation2014; Mahmood & Schömann, Citation2009; Van Mol, Citation2016; Williams et al., Citation2018).

The topic of youth migration and migration of the working population in the WB countries has been identified as a serious issue but so far, little academic research has been conducted. In fact, most research in WB countries focuses on the labour markets, youth and unemployment and factors affecting these three inter-connected terms (for example Savković & Gajić, Citation2016 for Serbia or Cvecic & Sokolic, Citation2018 for Croatia). However, research related to youth and migration has not yet been conducted for the case of BiH.

Atoyan et al. (Citation2016) assessed the effect of emigration in different groups of countries from Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe (CESEE), including Western Balkan countries as a separate (Southeastern) group, and note that emigration in these countries has been dominated by educated and young people. According to their results in CESEE emigration has exacerbated shortage of high-skilled labour and has lowered potential growth in CESEE. Moreover, they note that emigration appears to have reduced competitiveness and increased the size of government, by pushing up social spending in relation to GDP. They note that these effects are particularly strong in SEE and Baltic countries. Sanfey and Milatovic (Citation2018) note that aging population, which is partially result of youth emigration, is considered as a significant challenge to long-term growth and the sustainability of social security systems in Western Balkan countries.

3. BiH emigration and the characteristics of BiH emigrants

Most Western Balkan (WB) countries (except Albania) come from the same historical background, namely Yugoslavia and therefore share similar characteristics. Even though differences between former Yugoslav countries in terms of macroeconomic indicators existed in times of Yugoslavia (Statistical Yearbook of Yugoslavia, Citation1991), they became more obvious in the late 1990s and in the new millennium. WB countries entered transition process (transition shock, Onaran, Citation2011) at different times, so in case of BiH, it entered this process war-torn, with significant human, capital and infrastructural losses (the fall in GDP/GMP in just one year 1991–1992 amounted to 80 percent, Hadžiahmetović, Citation2005; Ding & Sherif, Citation1997; EBRD, Citation1999) and with a new constitution organised as an asymmetric (con)federation. More than twenty years after entering the transition process, differences in macroeconomic indicators among former Yugoslav members still exist and are summarised in .

Table 1. Main macroeconomic indicators for BiH and Western Balkan countries, 2018.

Other indicators confirm a gloomy situation for BiH but also for the entire WB region which could be seen in some progress indicators such as EBRD transition indicators, world governance indicators, World Bank’s ease of doing business indicator and global competitiveness indicators.Footnote2

When it comes to migration issues, all WB countries are faced with similar issues. These countries are often assessed as a group and compared with other groups of countries and similarities (among them) which are usually pointed out are: unemployment, corruption, frequent political disputes, slow progress, as well as deteriorating living conditions which lead to dissatisfaction of the population (Malaj & de Rubertis, Citation2017). Among the identified reasons for emigration from WB countries Vračić (Citation2018) states hopelessness and despair. Consequently, as identified by a recently published study on brain grain by Gallup (Živković, Citation2018), WB countries ranked worst in Europe. High percentage of citizen would also like to leave the countries, especially in Kosovo, Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina as the worst in the group (42%, 32% and 32%, respectively).

Since the focus in this paper is on BiH case, before assessing the state and reasons behind emigration from BiH in more details, in we summarise main BiH demographic characteristics.

Table 2. BiH demographic characteristics, 2013.

Data provided from the last census of 2013 indicates a fall of population in BiH since the last census was conducted in 1991. Apart from the data presented in , Census data also provide information on migration dynamics in BiH. Around 38 per cent of BiH population live in a place where they were born, whereas the remaining 62 per cent have changed the municipality where they were born, moved to another BiH entity (Federation of BiH or Republika Srpska), have come from one of the former Yugoslav countries or other countries in the world. Even though the results were presented for only one year since there are no reliable long-term migration dynamics data, these results could indicate that migration is present in BiH.

BiH is an upper middle-income country. Since the mid-1990s, this war-devastated country has faced numerous macroeconomic challenges which include the imbalance of the internal account, poor coverage of imports by exports, unfavourable structure of the public spending and the lack of investment. A particularly difficult problem is the high rate of unemployment, especially among young people. According to the latest data of the Agency for statistics of BiH, unemployment in 2017 was 20.7 per cent (BiH Agency of Statistics, Citation2018), while youth unemployment is even more alarming, and according to the World Bank data, it amounts to 46.7 per cent (World Bank, Citation2018).

The somewhat grey macroeconomic picture of BiH would be worse without remittances amounting to 1.9 billion USD or 12.5 per cent of BiH GDP (Mundial, Citation2017). That is also the only bright side linked to the issue of emigration, which in BiH increasingly comes in the focus of the public interest. BiH is a country characterized by a high rate of emigration. Apart from two large emigration waves, labour migrations of the 1960s and 1970s and forced migrations caused by the 1990s war, BiH is still confronted with the continued emigration of the population (Ministry of Security of Bosnia & Herzegovina, Citation2018). Although there is no exact statistical data on the number of persons who left BiH, partial data provided by the international and BiH institutions confirm the number and continuity of emigration of the population.

According to the records and censuses of the receiving countries, the total number of emigrants born in BiH, regardless of their current citizenship in 51 countries, is 1,691,350, out of which 60 per cent live in 30 European countries (EU 28, Switzerland and Norway, Ministry of Security of Bosnia & Herzegovina, Citation2018). Estimates of the World Bank which include only the first generation of migrants for the year 2013 were 44.5 per cent of the total population (Ratha, Citation2016). According to the data of the Sector for Immigration of the Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina, this number is estimated to be at least 2 million, representing 56.6 per cent of the total population (Ministry of Security, Citation2016). This number includes people born in BiH and an estimate of the number of their descendants.

Despite the presence of the awareness in the public discourse about the rising trend of the emigration of population in recent years, it is important to note that there are no official statistics in BiH to show the exact number and structure of emigrants in the last wave of emigration of the population. In the absence of this data, the data of the Agency for Identification of the Documents, Registers and Data Exchange of Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereafter: Agency) is often used to estimate the number of BiH citizens who have cancelled their residence in BiH. Agency’s data are used in publications of Ministry of security of BiH (which are publicly available) and include all BiH citizens regardless of age. Hence, we use the data only as an indicator of a trend, since there is no official data of emigration from BiH. Official data has yet another limitation related to the fact that BiH citizens are not obliged by law to cancel their permanent or temporary residence in BiH once they leave BiH. Hence, according to the Agency, 4.270 BiH citizens have cancelled their residence in BiH in 2017. BiH citizens who have cancelled their residence in BiH have mostly moved to Germany (1.339 BiH cizitens in 2017), Austria (994 BiH citizens in 2017) and former Yugoslav republics (842, 512 and 429 in 2017 to Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia respectively, ).

Table 3. Number of persons who cancelled their residence in BiH in 2017 by leading host countries.

For a specific case of BiH, high levels of unemployment among youth (ages 15–24) are often perceived as the main reason to emigrate from BiH. According to the long-term data from the World Bank (Citation2018) an increasing youth unemployment has been a long-term problem for the BiH case. However, in the last few years there is a falling trend in youth unemployment in BiH. Factors that might have contributed to this situation might relate to increased youth employment, migration from BiH as well as numerous internationally supported projects related to youth employment in BiH. Therefore, we also focus on investigating other potential socio-demographic and subjective determinants in our empirical analysis.

4. Model specification

The survey data used for this study includes the latest USAID’s National Survey of Citizens Perceptions (NSCP) for 2017. The 2017 survey is a third of such kind (previous two were conducted in 2015 and 2016) and in this paper, we are using the results from 2017 survey. Surveys from 2015 and 2016 applied different survey methodology as compared to the 2017 survey. Namely, in 2015 and 2016 surveys, only young people (ages 18–30) were asked the question related to migration intentions, whereas in the 2017 survey, all respondents were asked this question. Additionally, in 2015 and 2016 survey, nine possible reasons to why respondents were considering leaving the country were stated and respondents could only choose one. In the 2017 survey, all respondents were asked the migration questions with ten possible reasons to why they were considering leaving the country. Furthermore, in the 2017 survey, respondents were asked to rank up to three answers. In this paper, we wish to evaluate whether there is a difference in youth propensity to leave in comparison to those older than 30 years of age, so could not use the results from two previous USAID surveys (2015 and 2016).

The NSCP 2017 survey is comprehensive and divided into fourteen areas (excluding introduction and socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents) which are consolidated into eight areas. Eight areas vary from government/public policy questions, corruption, propensity to migrate, rule of law, political parties/participation, gender issues, etc. The survey data of NSCP for 2017 includes 3,084 respondents over the age of 18. The survey was conducted in November 2017 in partnership with IPSOS Adria. ‘The survey was administered through face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviewing. Interviewers followed specific guidelines and employed a random route technique to interview randomly selected household members over 18 years old using the Kish scheme’ (USAID, Citation2017, p. 12). Only one household member was interviewed. USAID (Citation2017) provides detailed information to how sampling design was created and how the sampling plan was designed to ensure a nationally representative sample large enough to allow for the planned analyses. Three-stage stratified random sampling approach was applied, where stage 1 included stratification of BiH by 13 geographic regions, stage 2 included stratification by type of settlement (urban vs. rural) and the third stage included number of sampling points determined by polling station territories drawn within the strata (USAID, Citation2017). The response rate to 2017 survey was relatively high and amounted to 64 per cent (USAID, Citation2017).

Following the literature and the data available from the survey, the model is specified in EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) . After estimating the model without interaction terms (EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) ) we estimated the model with interactions in other to examine the effects of youth on propensity to migrate conditional on the level of satisfaction with public sector and corruption (EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) ).

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

For the dependent variable the answers to the question ‘Are you considering leaving the country?’ are used (Prop_mig). Possible answers were yes, no and do not know. To interpret the results, we excluded ‘do not know’ answers (these amounted to only 4.5 per cent of total answers).

One of the independent variables we use is variable youth which is formed based on the date of birth variable for the survey, being 1 for those born after 1988 and 0 otherwise. This is our variable of interest since we want to examine whether there is a difference between youth and older inhabitants regarding their propensity to leave the country. We further include the answers to the question regarding the life satisfaction ‘To what degree are you satisfied with your standard of living, all the things you can buy and do?’ to estimate whether people who are less satisfied with their life situation tend to have higher propensity to leave the country (Life_satis). We grouped the answers so that group 1 are those who are satisfied (completely, mostly, somewhat) and 0 (zero) are the rest (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied and those completely, moderately and somewhat dissatisfied). To test whether the respondents tend to be more inclined to leave the country if they believe the corruption is present in BiH we included the answers to the question: ‘To what extent do you believe the systemic corruptionFootnote3 is present in BiH?’ (Corruption). Answers are ranked in four categories: not at all, somewhat, moderately and extremely. Additionally, the answers to the question regarding the satisfaction with public services is included (Pub_sector) (answers ranked from 1 to 7 from completely satisfied to completely dissatisfied). Since we wanted to preserve as much information as possible, we did not group (reclassify) the categories: these provide additional information about the effect of different (ranks of) responses. Since we want to test whether the effect of age (youth) differs with the different perceptions regarding corruption and satisfaction with public services we also include interaction terms between youth variable and variables for perceptions regarding the corruption and satisfaction with public services. Finally, we control for socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, namely gender, level of education and employment. Since 70 per cent of respondents did not provide information regarding their income, this variable is not included in the estimation. Macroeconomic variables are not included since all respondents come from the same country. In the survey, there is a question which asks for the reason behind willingness to emigrate, but there is a high level of unanswered questions (72.5 per cent), so this variable was omitted from the model. Within those who answered positively, most respondents identified inability to find work at home as a main reason for leaving the country (namely, 9.13%). The percentages of each answer to this question are presented in .

Table 4. Reasons for leaving the country.

Below we present descriptive statistics. Correlation matrix indicated that there is no multicollinearity (the highest correlation index being 0.388, please see the appendix).

Data in shows that 27.5 per cent of respondents answered that they consider leaving the country. However, this number is considerably higher between the youth as approximately half of young respondents consider leaving the country. However, to estimate whether young people are more likely to consider leaving the country than older people and whether this potential difference between the two groups is significant we estimate the equation and control for other variables identified in EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) .

Table 5. Descriptive statistics.

5. Estimation results and discussion

Since the dependent variable is categorical (and is transformed to binary for easier interpretation) probit will be used for estimating the above specified equations. As noted above, the question used for the dependent variable is: ‘Are you considering leaving the country?’ and the answer yes is coded 1 (one) and no as 0 (zero). presents marginal effects of the estimation of EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) . In , marginal effects of the model without interaction terms (EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) ) are presented, as comparison and robustness check, however EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) that includes the interaction terms is the preferred model.

Table 6. Marginal effects after estimation of EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) .

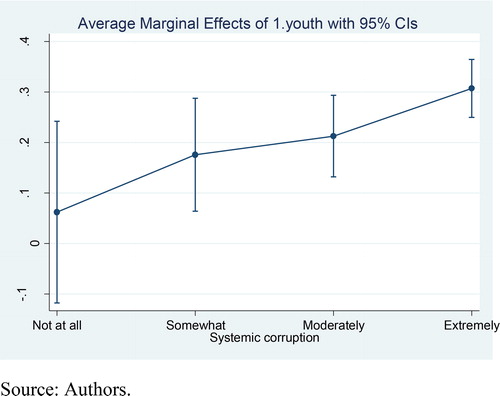

In only marginal effects are reported, since the sign, magnitude and significance of coefficients reported in the probit results may be misleading when interaction terms are included (Ai & Norton, Citation2003; Williams, Citation2012). The marginal effects consider that the youth is part of the interaction terms (since these are included in the regression prior to the calculation of the marginal effects), even though the marginal effect of the interaction term cannot be observed separately from the ‘margins’ results.Footnote4 However, in order to observe the marginal effect of youth conditional on other variables we observe marginsplot ().

Figure 1. Average marginal effect of youth on the probability of considering to leave the country at different perceptions about the existence of corruption in the country. Source: Authors.

From , we can determine that marginal effects show that young respondents are 26 percentage points more likely to consider leaving the country than the older respondents and this effect is significant at 1 percent level of significance. Regarding the effect of the satisfaction with public services variable on its own, the results imply that, as expected, the lower the satisfaction with public services the respondent is more likely to consider leaving the country. Those who are somewhat dissatisfied are 12 per cent and those mostly dissatisfied are 15 per cent more likely to consider leaving the country than those who are completely satisfied with public services. Furthermore, those who perceive that a systemic corruption is somewhat present in BiH are 8 per cent more likely to tend to leave the country than those who believe that there is no system corruption in a country, while those who believe that a systemic corruption is moderately and extremely present are 14 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively, more likely to consider leaving the country than those who think that there is no systemic corruption in the country. Interestingly, the response about the emigration is not affected by the level of satisfaction with life of the respondents in this database. The results for socio-demographic variables imply insignificant effect of gender and level of education. Finally, as expected, unemployed are 13 per cent more likely to consider leaving the country than those who are fully employment, while those who are temporally employed, students and retired people (retired having the highest share in this group) are 12 per cent less likely to consider leaving the country than those who are fully employed.

Since we are also interested in the effect of youth conditional on their satisfaction with public services and their perception of the existence of corruption, we estimated the effect of youth at different levels of these satisfactions and perceptions. The level of satisfaction with public services does not have significantly different effect between young and older respondents (therefore, we do not present these results). However, the marginal effect of youth on tendency to migrate differs with different perceptions about the existence of corruption. The marginsplot () implies that the higher perceptions about systemic corruption (as we go from those who believe that there is no corruption to these that believe that there is an extreme corruption) the higher is tendency/probability of young people to answer positively to question about leaving the country (Pr(Mig)). Namely, as implied by marginsplot, an average marginal effect of the variable youth (when young is equal to one) with 95 per cent of confidence intervals (CIs) on probability of positive answer to the question about emigration (Pr(Mig)) is higher the higher the perception about the existence of systemic corruption. These differences are estimated to be significant.

If we observe differences in responses between two BiH entities – namely Federation of BiH (FBiH) and Republika Srpska (RS), we found that, when observing all respondents, those from FBiH are more likely to respond that they would like to migrate than those from RS (). If we focus on young respondents only, the findings indicate that young people from RS are more likely to respond that they are willing to emigrate from BiH compared to youth in FBiH ().

Table 7. Marginal effects when differences between respondents from FBiH and RS are observed.

Table 8. Differences between entities among young respondents.

6. Conclusion

The number of people leaving BiH is extremely high, especially among youth and it has an upward trend. One of the most severe consequence is a brain drain, which deprives countries of origin of economic and social contributions of their educated and skilled people (UN, Citation2013). The consequences of brain drain for the state are the costs of investing in people (their education) who are leaving, staff shortage in all sectors and deficits in pension funds (due to aging population). It has been noted that in Bosnia and Herzegovina there has been a high number of doctors leaving a country whose education is a high cost for the country (Vračić, Citation2018). When highly skilled workers leave economic growth and productivity are likely to decline. WEF (Citation2017) points out that migrants are also a source of ideas and innovation who can contribute to businesses, governments and other entities in the city. Markova (Citation2007) identified change in family composition, family separations and the abandonment of old people, child outcomes in terms of labour, health and education as important social effects of migration. As noted previously, possible severe long-term effects relate to BiH ability to combat ageing population, youth migration and providing long-term growth and the sustainability of social security systems (Sanfey & Milatovic, Citation2018). Therefore, it is important to determine whether there is a higher tendency to leave the country among young people compared to older ones and which are the main determinants of emigration. By using the most recent data, provided by USAID NSCP 2017, based on 3,084 respondents from BiH, this paper investigates the most significant factors that affect respondents’ tendency to leave the country.

The estimation of probit model indicate that young people are more likely to consider leaving the country than older people. Also, those who are less satisfied with public services and who perceive that there is a high level of corruption in the country are more likely to consider leaving the country than those who are more satisfied with public services and who perceive lower level of corruption. Additionally, the effect of corruption is significantly higher among younger people.

Our findings suggest that the number one priority of government should be increasing the quality of public services and fighting corruption to curb the trend towards leaving the country, especially among youth. However, these results are only indicative since we observed only one year and since the data on reasons for leaving the country and the period of desired absence of respondents were mostly missing. It might be the case that some of respondents want to leave the country because of education or specialization which should not be considered as long-term (‘problematic’) emigration.

The importance of this research is highlighted in the fact that BiH has no official data on BiH citizens’ emigration or youth emigration, but the data about the people who cancelled their residence is often used in political public discourse, even though it is not representative factors. Further research and future NSCP surveys could, similar to research conducted by Van Dalen and Henkens (Citation2012) or Otrachshenko and Popova (Citation2014), include questions related to migration intention duration or the timescale of migration (mid-term to permanently).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank independent reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Kahanec and Fabo (Citation2013) consider youth up to the age of 34.

2 According to Ease of doing business Macedonia is the best performer on 10th, while Bosnia and Herzegovina is the worst performer, on 89th place (out of 190 assessed countries); according to global competitiveness index Serbia is on 65th and Bosnia and Herzegovina on 91st place (out of 140 countries). Croatia and Montenegro have all world governance indices (rule of law, political stability, control of corruption, government effectiveness) positive, while in BiH these are all negative. For differences in EBRD transition indicators see: Sanfey and Milatovic (Citation2018).

3 Systemic corruption, defined as corruption that is integrated and essential aspect of the economic, social and political system, in which most people have no alternatives to dealing with corrupt officials.

4 The command ‘margins’ (introduced in STATA11) does not report the marginal effects of the interaction terms, since, as stated in Williams (Citation2012, p.329): 'The value of the interaction term cannot change independently of the values of the component terms, so you cannot estimate a separate effect for the interaction.'

References

- Agadjanian, V., Nedoluzhko, L., & Kumskov, G. (2008). Eager to leave? Intentions to migrate abroad among young people in Kyrgyzstan. International Migration Review, 42(3), 620–651. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00140.x

- Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6

- Atoyan, R., Christiansen, L. E., Dizioli, A., Ebeke, C., Ilahi, N., Ilyina, A., Mehrez, G., Qu, H., Raei, F., Rhee, A., & Zakharova, D. (2016). Emigration and its economic impact on Eastern Europe. International Monetary Fund. Staff Discussion Notes, 16(7), 1. doi:10.5089/9781475576368.006

- Barometer, B. (2017). Public Opinion Survey (2017). Regional Cooperation Council.

- BiH Agency of Statistics. (2018). Pregled knjiga (Overview of books). BiH Agency of Statistics. Retrieved September 25, 2019, from http://www.popis.gov.ba/popis2013/knjige.php?id=1.

- Cairns, D. (2014). “I wouldn’t stay here”: economic crisis and youth mobility in Ireland. International Migration, 52(3), 236–249. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00776.x

- Cairns, D., & Smyth, J. (2011). I wouldn’t mind moving actually: Exploring Student Mobility in Northern Ireland. International Migration, 49(2), 135–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00533.x

- Cvecic, I., & Sokolic, D. (2018). Impact of public expenditure in labour market policies and other selected factors on youth unemployment. Economic research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 2060–2080. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2018.1480970

- Ding, W., & Sherif, K. (1997). Bosnia and Herzegovina: From recovery to sustainable growth. The World Bank.

- EBRD. (1999). Transition Report 1999: Ten years of transition.

- Fassmann, H., & Hintermann, C. (1998). Potential East-West migration: Demographic structure, motives and intentions. Czech Sociological Review, 6(1), 59–72.

- Hadžiahmetović, A. (2005). Ekonomija Evrope. Ekonomski Fakultet.

- Hagen-Zanker, J. (2008). Why do people migrate? A review of the theoretical literature (January 2008). Maastrcht Graduate School of Governance Working Paper.

- IMF. (2019). World Economic Outlook Database. Retrieved September 25, 2019, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/index.aspx.

- Kahanec, M., & Fabo, B. (2013). Migration strategies of crisis-stricken youth in an enlarged European Union. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, SAGE journal, 19(3), 365–380. doi:10.1177/1024258913493701

- Kahanec, M. & Zimmermann, K. F. (2010). EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Springer.

- Kowalska, K., & Strielkowski, W. (2013). Propensity to migration in the CEECs: Comparison of migration potential in the Czech Republic and Poland. Prague Economic Papers, 22(3), 343–357. doi:10.18267/j.pep.456

- Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47–57. doi:10.2307/2060063

- Mahmood, T., & Schömann, K. (2009). The decision to migrate: A simultaneous decision making approach. WZB Discussion Paper (No. SP II 2009-17).

- Malaj, V., & de Rubertis, S. (2017). Determinants of migration and the gravity model of migration-application on Western Balkan emigration flows. Migration Letters, 13(1), 204–220. doi:10.33182/ml.v14i2.327

- Markova, E. (2007). Economic and social effects of migration on sending countries: The cases of Albania and Bulgaria. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Working Paper. https://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/34/4/38528396.pdf.

- Massey, D. (1990). 1990: Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index, 56(1), 3–26. doi:10.2307/3644186

- Massey, D. S. (1999). Why does immigration occur? A theoretical synthesis (pp. 34–52). Russel Sage Foundation.

- Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina. (2018). Bosnia and Herzegovina migration profile for year 2017. Sector for migration. Ministry of Security of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Ministry of Security. (2016). Strategy in the area of migrations and asylum and action plan for the period 2016–2020. Ministry of Security.

- Mundial, B. (2017). Migration and remittances. Recent developments and outlook. Special topic: Global compact on migration. Banco Mundial.

- Onaran, Ö. (2011). From transition crisis to the global crisis: Twenty years of capitalism and labour in the Central and Eastern EU new member states. Capital & Class, 35(2), 213–231. doi:10.1177/0309816811402648

- Otrachshenko, V., & Popova, O. (2014). Life (dis) satisfaction and the intention to migrate: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 48, 40–49.

- Ratha, D. (2016). Migration and remittances Factbook 2016. The World Bank.

- Ravenstein, E. G. (1876). The birthplaces of the people and the laws of migration. Trübner.

- Ravenstein, E. G. (1885). The laws of migration. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 48(2), 167–235. doi:10.2307/2979181

- Sanfey, P., & Milatovic, J. (2018). The Western Balkans in transition: diagnosing the constraints on the path to a sustainable market economy. Background Paper for the Western Balkans Investment Summit Hosted by the EBRD, 26. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

- Savković, M., & Gajić, J. (2016). Youth in the contemporary labour markets: A comparison of European Union and Serbia. Sociologija, 58(3), 450–466.

- UN. (2013). Department of economic and social affairs. Youth and migration: United Nations world youth report. United Nations.

- USAID. (2017). National citizens perceptions survey 2017 – Findings report (May 2018). USAID.

- Van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2012). Explaining low international labour mobility: the role of networks, personality, and perceived labour market opportunities. Population, Space and Place, 18(1), 31–44. doi:10.1002/psp.642

- Van Mol, C. (2016). Migration aspirations of European youth in times of crisis. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(10), 1303–1320. doi:10.1080/13676261.2016.1166192

- Vračić, A. (2018). The way back: Brain drain and prosperity in the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations.

- WEF. (2017). Migration and its impact on cities. Retrieved September 25, 2019, from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Migration_Impact_Cities_report_2017_low.pdf.

- Williams, A. M., Jephcote, C., Janta, H., & Li, G. (2018). The migration intentions of young adults in Europe: A comparative, multilevel analysis. Population, Space and Place, 24(1), e2123. doi:10.1002/psp.2123

- Williams, R. (2012). Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 12(2), 308–331. doi:10.1177/1536867X1201200209

- World Bank. (2018). Youth unemployment indicator. Retrieved September 30, 2019, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS.

- Yugoslavia. (1991). Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia. Federal Agency of Statistics.

- Živković, V. (2018). Brain drain: The most important migration issue of the Western Balkans. Retrieved September 30, 2019, from https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2018/12/25/brain-drain-important-migration-issue-western-balkans/.

Appendix.

Correlation matrix

. corr mig d2 youth gender univ emplyment p3 p9c p1d

(obs = 2663)

| mig d2 youth gender univ emplym∼t p3 p9c p1d

—————————————————————————————————————————

mig | 1.0000

d2 | 0.3835 1.0000

youth | 0.2855 0.7061 1.0000

gender | 0.0463 −0.0186 0.0203 1.0000

univ | 0.0704 0.1781 0.0990 −0.0017 1.0000

emplyment | 0.1098 0.0230 0.1247 −0.1097 −0.1398 1.0000

p3 | 0.0564 0.0337 −0.0180 −0.0024 0.0147 0.0193 1.0000

p9c | 0.1218 −0.0292 −0.0627 0.0394 −0.0225 0.0225 0.1004 1.0000

p1d | 0.0258 −0.1047 −0.1020 −0.0100 −0.0815 0.0996 0.3885 0.0685 1.0000

—————————————————————————————————————————

Source: Authors.