?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article employs the bootstrap Granger full-sample and sub-sample rolling window estimation to explore the time-varying property between bilateral political relations and foreign direct investment based on Sino-Japanese relations. The result identifies a one-way causal nexus running from bilateral political relations to foreign direct investment. Bilateral political relations have both positive and negative influences on foreign direct investment inflows in different sub-stages, but merely negative impacts on outflows. However, the reverse causality has not been proven, which is inconsistent with the model of Polachek et al. that the increased foreign direct investment is conducive to improving bilateral political relations. We also divide the BPR into two dimensions: leader’s visits and diplomatic conflicts to examine the role of specific political actions. Leader’s visits can significantly increase FDI inflows and outflows, but diplomatic conflicts have less impact on FDI. China and Japan should increase dialogue to ensure bilateral relations’ stability and seek common ground in economic interests, ultimately providing investors with a favorable political environment.

1. Introduction

This study aims to reveal the dynamic causal mechanisms between bilateral political relations (BPR) and foreign direct investment (FDI) based on Sino-Japanese relations. It is noteworthy that Sino-Japanese relations have always been a contradictory relationship for decades and continue to be troubled by some issues, for example, the Diaoyu Islands dispute, attitude of the Nanjing Massacre, and Japanese politicians visiting the Yasukuni Shrine. At the same time, Sino-Japanese rivalry might initially have been affected by historical disputes but more and more by recent events other than BPR, such as the role of the U.S. in the Asia Pacific region. Currently, political conflicts between China and Japan may be aggravated by the Taiwan issue, island dispute and competition for marine resources.

Although there have been many controversial problems in Sino-Japanese relations since the 1980s, the economic relations remain steady and less turbulent than expected. China and Japan have forged closer economic ties with the expansion of global integration. As trade between the two countries increases, the number of foreign investments has also increased. For instance, Japan’s share of Chinese investment proliferated since economic reforms took hold in the 1990s and currently, they have become one of the foremost economic partnerships for each other. By the end of 2016, the total direct investment from Japan to China amounted to $8.63 billion, far beyond the $0.503 billion in 1990. More than 1800 Japanese listed companies owned about 6300 Chinese subsidiaries in 2010. The same period data show that 4700 Japanese non-listed companies have more than 8,400 subsidiaries in China. At the same time, with the implementation of “going out” strategy and entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), Chinese enterprises’ direct investment in Japan multiplied, increased by 20.2 times from $139 million in 2004 to $2.944 billion in 2015.

Overall, Sino-Japanese relations are often characterized by “hot economics and cold politics.” Although economic relations are increasingly close, reciprocal mistrust and unresolved historical disputes seem to continue to hinder the development of political relations. However, few pieces of research have illustrated how Sino-Japanese BPR affects the FDI and what important roles FDI plays in forcing nations not to participate in political conflict (using quantitative method). Therefore, under the background of unstable international political and economic situation, it is essential to explore how BPR affects FDI and vice versa based on Sino-Japanese relations.

We apply the bootstrap rolling window technology to test the interaction, thus providing superior identification to study the causal relationship between Sino-Japanese political relations and FDI. The bootstrap rolling window approach is distinct from most conventional mathematical methods, such as pulse impulse response methods (correlation analysis, Granger causality), which cannot identify full-sample and sub-sample relationships between time series and cannot reveal how such relationships change over time. At the same time, this approach can also assess whether BPR has a significant effect on FDI and whether that effect is temporary or permanent.

The paper is ordered as follows: in section 2, we briefly present the literature review, followed by section 3, which outlines the theoretical mechanism of BPR and FDI. Section 4 explains the methodology of our study, continuing with section 5 which describes the corresponding data and section 6 highlights our empirical results. The last section concludes our study.

2. Literature review

Because FDI relates to at least two countries, it is likely to be affected by BPR (Li and Vashchilko, Citation2010). Studying the relationship between BPR and FDI leads to a better understanding of how political relations affect the allocation of international resources (Li and Vashchilko, Citation2010). In some ways, it seems intuitive that the characteristics of BPR would exert a remarkably economic influence on FDI (Desbordes and Vicard, Citation2009). The FDI may be hindered by bilateral political conflicts and promoted by collaboration among countries (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Citation2007). At the same time, investment policies are crucial in regulating inter-state political relations. Specifically, bilateral investment agreements can improve political relations and the investment barriers may trigger political conflict. Besides, the intangible variables such as entrepreneurs’ psychological expectations and state leaders’ mutual visits are also crucial to BPR and FDI (Yang et al., Citation2016). On the one hand, although there are some conflicts between countries, entrepreneurs expect that the BPR can still be maintained in a relatively stable range, the deterioration of political relations will not cause multinational enterprises to change their investment decisions (Nigh, Citation1985; Li, Citation2008). Entrepreneurs can decide to stop investing only when the losses caused by deteriorating political relations exceed the cost of a business withdrawal (Lee Citation2008; Polachek et al., Citation2005b). On the other hand, in international relations, political and economic factors interact and influence each other. The deterioration of political relations between China and Japan has made the dialogue between governments narrow and politicized, and many economic cooperation projects have been put on hold. The short-term high-level mutual visits can be regarded as the diffusion process of the political rights of investors from home country to host country, which shows the political preference of home country, and helps to improve the enthusiasm of enterprises for foreign investment (Zhang and Jiang, Citation2012).

Several researches explore the question of causal nexus between BPR and FDI, and the findings vary widely. There are many mechanisms by which BPR affect FDI, such as the anticipation and operating cost of investment companies or correlative government supervision policies (Li, Citation2008; Nigh, Citation1985). Bilateral political conflicts expand the non-determinacy about the investment conditions in the future. Foreign investors are concerned regarding the state of BPR because its exacerbation can expand the risk of confiscation of investment in the host country (FDI recipient) (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Citation2007). Owing to foreign investors is often seen by representatives of the home country (FDI provider) that they are likely to be targets of retaliation in the event of bilateral political conflicts (Desbordes, Citation2010). The home government may prevent FDI from flowing to rivals through implementing capital regulation. Host governments can increase tax rates or confiscate assets directly to restrict foreign investors’ entry (Brewer, Citation1993). The deterioration of BPR may also trigger nationalist feelings, causing consumer boycotts and retaliatory sanctions which decrease potential profits and may even bring out the loss of FDI (Chan and Mason, Citation1992; Li and Vashchilko, Citation2010). Blanton and Apodaca (Citation2007) argue that host countries are eager to maintain stable BPR to ensure sustained FDI, which can bring employment opportunities and potential income. Guiso et al. (Citation2009) suggest that lower BPR result in less FDI between the two countries, even after excluding other factors affecting economic activity. Li and Liang (Citation2012) find that Chinese outward FDI is more likely to flow to countries with which the Chinese government has better political relations. Hajzler (Citation2014) argues that political risks, including corruption, expropriation and war, are significant impediments to FDI in developing countries. Osabutey and Okoro (Citation2015) find that political risk has a significant influence on the inflow of FDI into developing economies such as Nigeria. Irrespective of the political risk rating, a consistent improvement in composite political risk enhances FDI inflow. Shahzad et al. (Citation2016) show that long-run cointegration holds among FDI, terrorism and economic growth; they reveal that political risk has a deteriorating impact on FDI. Julio and Yook (Citation2016) find that the impact of political uncertainty on FDI flows depends on the level of institutional efficiency. Countries with higher levels of institutional efficiency experience significantly less variation in FDI around election cycles. Yang et al. (Citation2016) find that bilateral political relations not only promote the scale and the diversification degree of enterprises’ outward FDI but also increase its success probability, while there are specific differences across policy tools and industries. Kim (Citation2016) finds that political conflicts pose long-lasting risks for foreign investors, and the attractiveness of conflict-prone countries continues to decline. However, the risk of political conflict is short-lived and easy to recover in peacetime. Azzimonti (Citation2018) inspects the nexus between BPR and FDI adopting a dynamic redistribution model, his research showing a negative connection between BPR and FDI via investment risk channels. Dai and Li (Citation2018) show that China’s FDI will be significantly affected by bilateral political relationships. The closeness of the political relationship is conducive to the increase of China’s outward FDI. Sun and Liu (Citation2019) also show that the establishment or upgrade of partnerships has had a positive effect on Chinese enterprises’ decisions on outward FDI for at least the short term.

In addition, the effects of FDI on BPR have tended to receive more attention in recent years than the effects of BPR on FDI (Newland and Govella, Citation2010). Foreign investment is a key factor in easing political relations between countries. Governments might try to improve political relations to avoid damaging the interests of investors (Bussmann, Citation2010). Liberal peace theory has pointed out many benefits of FDI, claiming that increased FDI and a close economic relationship would improve the BPR (Polachek et al., Citation2007; Souva and Prins, Citation2006). FDI raises the opportunity cost of bilateral political conflicts and encourages the two governments to adopt more friendly foreign policies (Lee, Citation2008). Bussmann and Schneider (Citation2007) find that the level of inflow of FDI indeed reduces the likelihood of internal conflict. Lee and Mitchell (Citation2012) conclude that the territorial dispute is unlikely to emerge as the level of investment expands globally. The increase in FDI between the two disputing countries has dramatically reduced the possibility of escalation of disputed issues, thus improving the BPR. Knill et al. (Citation2012) find that the investment leads to improvement (deterioration) in political relations for relatively more closed (open) target nations. Kluge (Citation2017) concludes that foreign investors are initially popular, but political risk is high when the market competition with domestic elites becomes intense.

However, other studies do not confirm these findings, and Mihalache-O’Keef and Vashchilko (Citation2010) show that there is no influence of BPR on FDI flows, even though many companies suffer losses from political conflicts. They think that countries will try hard to make up for risk faced by businesses by signing bilateral investment treaties. Barry (Citation2018) finds that investors will not evacuate in response to demurrals, low-intensity conflicts or hostile political relations, even if this situation lasts for many years. Only with the deterioration of BPR, when the expenses of political conflict exceed those of exit, foreign-funded enterprises will withdraw from the host country. In summary, these findings show that the causal relationship between BPR and FDI remains a much-debated question.

Considering Sino-Japanese relations, there are relatively few researches, and the conclusions are also inconsistent. Koo (Citation2009) argues that economic interdependence is conducive to the easing of political conflicts between China and Japan on territorial and maritime disputes. Davis and Meunier (Citation2011) research the effect of frictions between China and Japan on trade and investment flows, finding that negative political relations caused by disputes have not impaired Sino-Japanese trade or investment flows. Aggregate economic flows are unaffected by the deterioration of BPR. In contrast, they show that trade and FDI keep on increasing sharply during the same period of deterioration in political relations. Gao et al. (Citation2018) find that casualties in diverse regions of China during World War II had a significant influence on the location selection of Japan’s investment. However, the previous literature using the full-sample estimate may lead to inaccurate results owing to the time-varying properties not being fully considered, involving changes in external political conflicts and bilateral investment mode. Our analysis considers structural changes by using bootstrap sub-sample rolling window estimation and attempt to interpret through what interactive mechanism does Sino-Japanese BPR affect FDI or vice versa.

3. Theoretical mechanism

FDI may bring national safety and economic benefits closer together. The increase in global FDI reduces the possibility of bilateral political conflicts, as countries can benefit more from a peaceful investment environment (Lee and Mitchell, Citation2012). From the aspect of maximizing national social welfare, Polachek et al. (Citation2007) present a one-stage model that the purpose is to explore the nexus between BPR and FDI. First, the preference of the home or host country is reflected as follow:

(1)

(1)

where U is the welfare function, C denotes consumption. The variable Z is non-negative real numbers, represents the quality of BPR (conflict or collaboration).

We suppose that multinational corporations are located only in the home country. Initially, the total capital of multinational corporations is k. k1 and k2 represent capital allocation to home and host countries, respectively. Hence: The multinational firm generates profits of R1 and R2, respectively. These returns are inversely proportional to the amount of investment due to diminishing returns. They are also inversely proportional to the degree of political conflict, as bad BPR impose more significant regulatory restrictions on foreign investors. Moreover, the return of FDI depends on variables, e.g., infrastructure, the education degree of the workforce and various types of capital, which can be express Ω.

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

with

The income of host country, y* is:

(4)

(4)

where w* denotes, the wage rate, k* and R* are defined as capital stock and return, respectively. Host countries’ wage rates also increase with the rise of the human capital (H*), as labor and capital stock are considered complementary. Hence:

(5)

(5)

with

Finally, the host country’s budget constraints are:

(6)

(6)

If we substitute equation into EquationEquation (6)

(6)

(6) , solving C and replace it with the utility function of the home country. In phase two, the problem of the home country is to maximize EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) . That is to say:

(7)

(7)

Then the first-order condition is:

(8)

(8)

This equation shows that the optimal level of political conflict is that the marginal benefit of the conflicted relationship with the host country equals the marginal cost. The host country can maximize (1) when EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) generating the first-order condition:

(9)

(9)

Hence, in case the marginal utility of political conflict has been declining, the optimal degree of Z ascertained by EquationEquations (8)(8)

(8) and Equation(9)

(9)

(9) must be smaller. Specifically, because multinational corporations create economic benefits for home and host countries. If political conflicts arise, FDI in these two countries is likely to decrease, and many of the benefits will be lost. Considering the maximization of social welfare, both governments will strive to reduce political conflicts and promote bilateral cooperation.

4. Methodology

4.1. Bootstrap full-sample causality test

We explore the causal nexus between Sino-Japanese BPR and FDI by utilizing a full-sample Granger causality test based on the bivariate vector autoregressive (VAR). Under the framework of the residual-based bootstrap (RB) modified-Likelihood Ratio (LR) method, the VAR (p) process for two variables may be expressed as follows:

(10)

(10)

where

follows a zero mean, independent, and white noise process with the nonsingular covariance matrix. By splitting yt into two sub-vectors,

thus the above equation can be rewritten as follows:

(11)

(11)

i, j = 1,2 and L is the lag operator defined as

Tax burden (TB) and labor cost (LC) are control variables.

Start with; we examine the hypothesis that BPR does not Granger cause FDI, for k = 1, 2,…, s. Similarly, the inverse causal hypothesis is tested through

for k = 1, 2,…, s. The hypothesis will be rejected if BPR has an impact on FDI and vice versa.

4.2. Parameter stability test

One of the assumptions for the Granger full-sample causality tests is that the parameters of the VAR model are constant. This assumption may be wrong if structural changes are shown in the underlying full-sample time series (Balcilar and Ozdemir, Citation2013; Su et al., Citation2020). Thus, this study tested the stability of short-term parameters by using the Sup-F, Mean-F, and Exp-F tests developed by Andrews (Citation1993). However, when the underlying variables were cointegrated, the VAR model in first differences is wrongly specified unless error-correction is allowed. Consequently, we tested the long-term relationship between cointegration and parameter stability. We applied the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FM-OLS) estimator proposed by Phillips and Hansen (Citation1990) to estimate the parameters of cointegration regressions. Then, we used the Lc test from Nyblom (Citation1989) and Hansen (Citation2002) to check the stability of the long-term parameters.

4.3. Sub-sample rolling-window causality test

In order to overcome the parameter nonconstancy and to avoid pretest bias, this study turn to account the sub-samples rolling window Granger causality test based on a modified bootstrap estimation (Balcilar et al., Citation2010; Su, Wang, et al., Citation2019). By calculating the bootstrap p-values of observed LR-statistics rolling through T-l sub-samples, the possible changes in the causal nexus between the BPR and FDI could be captured.

The impact of BPR on FDI is defined as the average of the entire bootstrap estimates derived from the formula with

representing the number of bootstrap repetitions. Similarly, the impact of FDI on BPR is obtained from the formula

Both

and

are bootstrap estimates from the VAR models in EquationEquation (11)

(11)

(11) . The 90% confidence intervals are provided, in which the lower and upper bounds are the same as the 5th and 95th quantiles of

and

respectively (Balcilar et al., Citation2010). In setting the rolling window size l, both the accuracy and the representativeness should be considered. Pesaran and Timmermann (Citation2005) confirm that to balance the accuracy and representativeness, the size of the window should not be less than 20 when there is a structural change.

5. Data

In this study, we consider monthly data from 2003:06 to 2018:05 to examine the interaction of Sino-Japanese BPR and FDI. In 2003, the Third Plenary Session of the 16th Communist Party of China Central Committee was held, proposing to fully play the role of foreign capital and enhance the capability to take part in international cooperation and competition. This paper uses Japanese companies’ investment in China as an indicator of the FDI inflows; at the same time, the FDI outflows are expressed by Chinese enterprises’ investment in Japan.Footnote1 The data are gathered from the WIND database. The issue of how to measure the degree of BPR has always been the focus of debate. In this paper, we use the database from the Institute of International Relations of Tsinghua University that provides a quantitative assessment of Sino-Japanese relations, which is called the “Tsinghua approach”Footnote2 (Zhang, Citation2012). It includes not only high-level political conflicts such as wars but also short-term disputes and collaboration between countries. This database benefit from quantitative measures to divide bilateral political relations into six levels (Rivalry, Tension, Discord, Ordinary, Good, and Friendly). The positive scale value is defined as cooperation and the negative represents conflict, while zero is a neutral BPR.

Besides, we divide the variables of political relations into the following two dimensions. The first is the leader’s visit. As a representative of the ruling party, the visit of the state leaders reflects the party’s attitude towards the political relations between the two countries. Compared with the long-term formal diplomatic relations, the short-term high-level mutual visits have a stronger promotion effect on the scale and diversification of enterprise investment, which can significantly improve the success rate of foreign investment (Yang et al., Citation2016). The leaders’ visit indicates the mutual visits of political leaders of the two countries in a specific period. This variable is represented by the weighted number of times of joint visits, meetings in third countries and greetings from the leader. The score of mutual visits at the level of head of state is two points, and that of mutual visits to other national leaders, meetings in the third parliament, and greetings to each other is one point (Zhang and Jiang, Citation2012). The second is diplomatic conflict. This variable can directly reflect the government’s attitude towards a specific diplomatic dispute. In terms of the number of diplomatic conflicts in a specific period, the score of serious conflicts is two points, and that of global conflicts is one point (Zhang and Jiang, Citation2012). The above data comes from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC.

This paper uses two control variables. The first is the tax burden (TB). The negative nexus between TB and FDI has been substantiated (Demooij and Ederveen, Citation2003). Bellak et al. (Citation2007) also find that a 1% reduction in the tax rate will promote FDI inflows about 1.45%. This paper chooses the corporate income tax burden rate (income tax payable divided by total profit) to measure the TB of foreign-funded enterprises (Hartman, Citation1984). The second is the labor cost (LC). Foreign-invested enterprises are more inclined to invest in regions with lower labor costs (Zhang and Markusen, Citation1999). This article utilizes the average wage of employed people in foreign-invested enterprises to measure LC. We can get the data of the control variables from the National Bureau of Statistics and the China Statistical Yearbook.

illustrates the relevant descriptive statistics. The means of BPR, FDI inflows and outflows suggest their series are concentrated at the −1.217, 0.395, and 0.017 levels, respectively. The average value of Sino-Japanese relations is negative, indicating that political relations between these two countries have been on average much more conflict than cooperative. The skewness is negative in BPR, FDI inflows and outflows are positive. However, the kurtosis is the opposite, which demonstrates the feature of leptokurtosis and a fat-tailand. Also, the Jarque-Bera test proves that these variables are non-normally distributed, indicating that the conventional estimation method is not appropriate for the Granger causality test. Chunhachinda et al. (Citation1997) point out that if the time series data are non-normally distributed, then the full-sample Granger causality test will lead to instability of the parameters and thus lose effectiveness. Therefore, we apply the bootstrap sub-sample rolling window test, liable to capture the time-varying causality of BPR and FDI.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for BPR, FDI inflows and outflows.

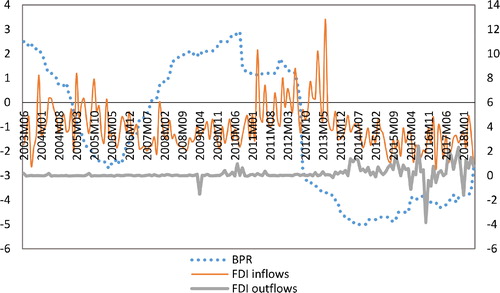

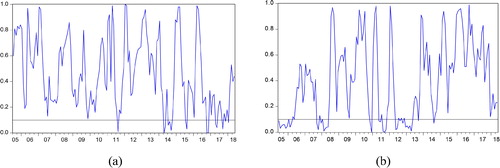

indicates the trend of BPR, FDI inflows, and outflows. Sino-Japanese political relations have been declining from 2003 to 2006. Specifically, in August 2003, mustard gas left over by the Japanese army during the Second Sino-Japanese War poisoned many Chinese citizens. Though the mustard gas incident did not receive specific attention in the media, the event certainly caused strains in Sino-Japanese relations. Because of China begins to build the natural gas drilling facilities in Chunxiao gas fields in the East China Sea. In 2004, the Japanese government investigated disputed areas and began to explore natural gas. Subsequently, a series of demonstrations broke out in China to protest against illegal oil exploitation in July 2004. On 5 April 2005, a history textbook compiled by the Society for the Reform of Textbooks has been re-authorized by the Ministry of Education, which whitewashed Japan’s aggression during World War II. Large-scale anti-Japanese activities continued for several weeks in mainland China. Besides, Chinese mass protests towards Japan repeatedly erupted and suspended the high-level diplomatic conferences owing to Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi continues to visit the Yasukuni Shrine every year. After the Koizumi government stepped down, Sino-Japanese political relations gradually improved. From 2006 to 2010, Japan frequently changed its prime minister. During this period, there was no significant political conflict. After many negotiations, China and Japan initially reached a bilateral agreement about the cooperative development of gas fields in June 2008. The agreements are expected to avoid sovereignty controversial issue by laying aside disputes. On 7 September 2010, two Japanese coastguard vessels collided with a Chinese fishing boat near Diaoyu Island. In September 2012, Japanese Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko prepared to purchase the Diaoyu Islands in the name of the central government, namely “nationalization of the Diaoyu Islands.” After these incidents, anti-Japanese nationalism is rapidly gaining popularity in China. During the reign of Shinzo Abe, China and Japan have been confronted with a hostile atmosphere resulting from historical and territorial conflicts. Sino-Japanese relations fell to the lowest level since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1972. Considering the 45th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Japan, President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe met in Vietnam on 11 November 2017. Subsequently, Shinzo Abe visited China on 26 October 2018, because of the 40th anniversary of the China-Japan Treaty of Peace and Friendship. Sino-Japanese relations have begun to improve after 2017.

As shown in , unlike the ups and downs of BPR, FDI inflows are less volatile. The one exception is that after 2013, BPR and FDI inflows have both fallen and remained at a low level. In addition, we have also found that the Sino-Japanese political conflict does not always reduce FDI inflows. The most obvious is that the political relations have deteriorated during 2010–2013, but FDI inflows have gradually increased. As for FDI outflows, we can see that Chinese enterprises’ investment in Japan has remained at a relatively low level. Influenced by territorial disputes, marine resources disputes, and historical issues, the uncertainty of Sino-Japanese political relations has also affected the growth of Chinese enterprises’ direct investment in Japan to a certain extent. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Commerce, after the financial crisis in 2008, the merger and acquisition of Chinese enterprises in Japan rose rapidly, reaching a peak of 22 pieces in 2010. Afterward, it declined sharply due to the impact of the earthquake in Japan and the conflict on the Diaoyu Islands and began to rise steadily in 2014. In General, the nexus between BPR and FDI is complex and ambiguous.

6. Empirical results

For testing for the stationarity of the data, we perform the Augmented Dickey and Fuller (1979) test, Phillips and Perron (1988) test and Kwiatkowski et al. (1992) test. reports the results of the unit root test. The statistic t-values of the ADF and PP test are all larger than the critical value and therefore accept the null hypothesis for BPR, FDI inflows and outflows at the significance level of 1%. Moreover, the KPSS statistics reject the null hypothesis at the significance level of 1%, which means that these three variables are non-stationary. However, BPR, FDI inflows and outflows are stationary after the first-order difference, which suggests that both of them are I (1) process. Therefore, we can apply the bivariate VAR model to estimate the full-sample causal nexus based on EquationEquation (11)(11)

(11) .

Table 2. Unit root test results.

Granger causality test is used to analyze the causality between economic variables. reveals the results of the full-sample causality test. According to the bootstrap p-values (0.616 and 0.713), no causality between BPR and FDI inflows. The null hypothesis that FDI outflows do not Granger cause BPR is accepted due to p-values is 0.765, but the null hypothesis that BPR do not Granger cause FDI outflows is rejected at the significant level of 1% (p-values is 0.098), which indicates that BPR can affect FDI outflows. The result is not following Polachek et al. (Citation2007), who argue that FDI is conducive to improving BPR. Furthermore, we can ascertain that TB and LC can affect FDI inflows. On the one hand, China’s abundant labor force and low cost may be the main reasons for attracting Japanese enterprises to invest in China. Swain and Wang (Citation1997) also show that there is a positive connection between China’s cheap labor force and FDI inflow. On the other hand, China has been adhering to the policy of absorbing foreign capital since its accession to the WTO. The Seventh National People’s Congress passed the “Income Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China on Foreign-invested Enterprises and Foreign Enterprises” on 9 April 1991, which gives foreign enterprises greater tax preferences. The implementation of these policies has a great role in promoting FDI inflows. In addition, also shows the impact of control variables on FDI outflows. These two variables did not pass the 10% significance level indicating that TB and LC will not affect China’s investment in Japan. Chinese firms invest in Japan mainly for access to advanced technology, not for cheap labor. At the same time, Japan has exercised strict control over the entry of foreign capital for a long time, and generally has a sense of guarding against foreign investment, resulting in a low level of appeal to foreign investment. With the progress of reform and opening, the direct investment from China to Japan has also developed rapidly; however, the scale is relatively low. Moreover, the proportion of China’s FDI to Japan in the total amount of outward direct investment in the same period is less than 0.5%, which indicates that Japan has not become the main target country of China’s FDI. In 2015, Japan’s FDI stock in China amounted to 101.82 billion U.S. dollars, accounting for 6.2% of China’s total FDI stock, ranking first among all the FDI countries in China. However, Chinese enterprises’ direct investment in Japan is still at a low level. China’s FDI stock in Japan was $2.94 billion, accounting for only 1.5% of Japan’s total FDI stock. The scale of Japan’s investment in China is 35 times that of China’s investment in Japan, and the two countries’ two-way direct investment shows significant asymmetry.

Table 3. Full-sample Granger causality tests.

The parameters in the full-sample estimate will change over time because of the structural changes. The causal link between the Sino-Japanese BPR and FDI may be unstable. To this end, the parameter stability is tested to determine whether there is a structural change. As mentioned before, four statistical methods are performed to examine the short-term stability of the above-mentioned VAR model parameters constituted by Sino-Japanese BPR, FDI inflows and outflows. The relevant results are reported in . The Mean-F and Exp-F tests conclude that models from the BPR, FDI inflows, outflows and the VAR system may gradually change over time. The Sup-F tests show that there is a sudden shift in the Sino-Japanese BPR, FDI inflows, outflows and the VAR system. The Lc test shows that the parameters obey the random walk process (Gardner, Citation1969). In summary, the parameter stability test shows that the parameters are significantly unstable among BPR, FDI inflows and outflows. The result from the bootstrap full-sample test is unreliable due to the structural changes.

Table 4. Parameter stability tests.

We turn to reexamine the nexus between BPR and FDI by using the bootstrap sub-sample rolling window causality test. The structural changes can be tested when the fixed window is allowed to scroll.Footnote3 Causality between BPR and FDI in distinct sub-samples reflects the changes of the specific relationship under certain economic backgrounds. Through this method, we can assess whether BPR has an important influence on FDI or vice versa and whether that effect is temporary or permanent. These rolling estimates move from 2005:07 to 2018:05 after trimming 24-month observations. Furthermore, we also calculated the corresponding coefficients of the VAR model to explore whether the influence of BPR on FDI (or the influence of FDI on BPR) is positive or negative.

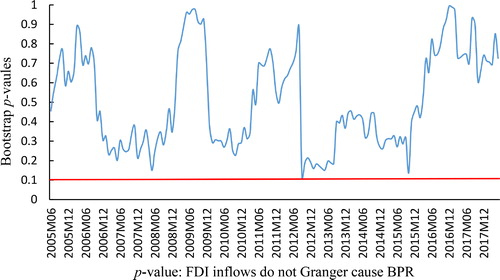

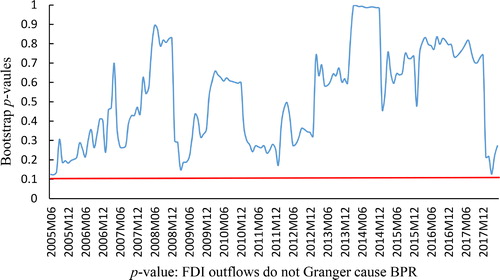

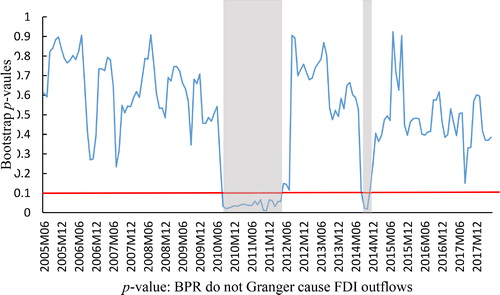

reports the rolling bootstrap p-values with the null hypothesis that FDI inflows do not affect BPR. Similarly, presents the null hypothesis that FDI outflows do not Granger cause BPR. In light of and , the null hypothesis is not rejected in all the sub-periods, indicating that both FDI inflows and outflows do not affect BPR. China is unlikely to sacrifice core interests to attract foreign investment. The basic security interests of countries outweigh the economic losses that they may suffer due to the withdrawal of FDI (Sorens and Ruger, Citation2014). At the same time, the Chinese Foreign Ministry has repeatedly repudiated the probability that Sino-Japanese economic cooperation would change its sovereignty claims. Although FDI inflows and outflows can help promote Sino-Japanese collaboration, the Chinese government cannot compromise on the issue of sovereignty. Therefore, if there is a political conflict, the two countries will still be hostile to safeguard their respective core interests. The loss of FDI offers only a weak motivation to avoid conflict (Sorens and Ruger, Citation2014). In addition, the government’s accommodation and the increasing liberalization have also led to anti-Japanese nationalism, which will not be weakened by mutual economic dependence (He, Citation2007). The result is not under the model of Polachek et al. (Citation2007), who argues that FDI is conducive to improving BPR.

Figure 2. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that FDI inflows do not Granger cause BPR.

Figure 3. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that FDI outflows do not Granger cause BPR.

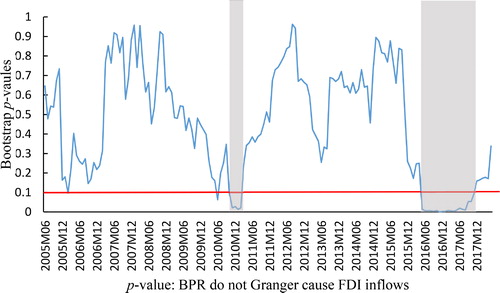

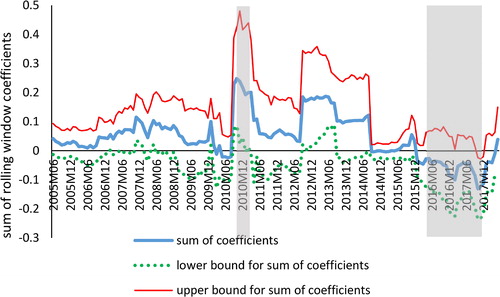

According to and , the null hypothesis that BPR do not Granger cause FDI inflows is rejected in the sub-sample periods of 2010:10–2011:02 and 2016:05–2017:11. It can be noticed in , that both positive effects (2010:10–2011:02) and negative effects (2016:05–2017:11) occur from BPR to FDI inflows. The result of 2010:10–2011:02 presents that FDI inflows will suspend or rapidly reduce once Sino-Japanese political relations deteriorate. That is, Japanese companies that depend heavily on the Chinese economy are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of the intensification of political conflicts between China and Japan. On 7 September 2010, two Japanese coastguard vessels collided with a Chinese fishing boat in disputed waters near Diaoyu Island, which cause major Sino-Japanese political conflict. As outlined by Li and Vashchilko (Citation2010), the quality of BPR affects investment flows by influencing government policies and changing investors’ expectations of political risks; hence, political conflicts reduce FDI inflows. In addition, political conflicts may influence corporate value through state intervention and consumer rebound (Fisman et al., Citation2014). The Chinese government’s intervention is likely to be an important mechanism influencing Japanese companies’ investment decisions because the government could threaten to prevent or withdraw investment inflows as a negotiating tool in the background of sovereignty disputes.

Figure 4. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that BPR do not Granger cause FDI inflows.

Figure 5. Bootstrap estimates of the sum of the rolling window coefficients for the impact of BPR on FDI inflows.

The result of 2016:05–2017:11 presents that Sino-Japanese political conflict favors the expansion of FDI inflows. This contrasts sharply with the conclusion that the political conflict described above jeopardizes FDI inflows. Since the reform and opening, the Chinese government has continuously improved the investment environment and utilized foreign capital on a large scale. The desire of developing countries to appeal to and safeguard FDI inflows may have an important influence, the high level of integration and economic interdependence may generate common interests between provided and recipient countries (Lee and Mitchell, Citation2012). On the one hand, FDI inflows are beneficial to the host country (China). Specifically, the benefits are reflected in the following aspects. First, FDI can bring advanced technology, management experience and human capital to the host country. Some of these may be non-competitive products that can be shared by local companies (Polachek et al., Citation2005a; Yahya, Citation2016). Second, FDI inflows can significantly increase the level of per capita income in the host country. Multinational companies provide training for workers in host countries, and if they switch employers, productivity gains may benefit local companies (Garland and Biglaiser Citation2009). Third, foreign capital raises the fiscal revenue of the host country by paying corporate tax. These incomes can be used to improve people’s living standards (Ali and Guo, Citation2005; Jensen, Citation2006; Markusen and Venables, Citation1999). In summary, China’s FDI inflows make a significant impact on the process of social and economic development in terms of various channels such as technology spillover, capital flows, etc. (Zhang, Citation2005). Apart from this, the Chinese government has always adhered to the policy of economic liberalization and emphasized that job creation is the goal of foreign investment. The government would be averse to harm corporations with foreign capital that generates local jobs. As pointed out by Fisman et al. (Citation2014), foreign companies that employ more workers are relatively immune to Sino-Japanese tensions. On the other hand, as long as China does not adopt a clear boycott policy, Japanese companies will still increase their investment in China. Because through investing abroad, multinational corporations can make use of local resources and evade trade barriers. Such outward investment activities can promote the socio-economic development of the home country (Polachek et al., Citation2007).

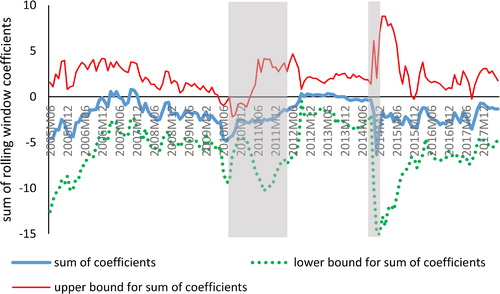

We have also examined the causality from BPR to FDI outflows, which is highlighted in and . It reveals that BPR has an important influence on FDI outflows in sub-sample 2010:08–2012:04 and 2014:09–2014:11. shows that BPR exerts negative effects on FDI outflows in these two sub-sample periods. During the same period of deterioration in BPR, the economic relationship between China and Japan became increasingly interdependent. The suspension of investment will reduce incomes in many industries and ultimately slow down economic growth (Bussmann, Citation2010). To promoting the welfare of the entire country, the Chinese government will not take economic measures even if a political conflict occurs so that FDI outflows may increase in the case of deterioration in BPR. As Koo (Citation2009) points out that the alleged ‘‘cold politics and hot economics’’ has become an essential characteristic of Sino-Japanese relations. Multinational corporations will put pressure on governments to peacefully resolve disputed issues, which will encourage further mutual investment between disputing countries (Lee and Mitchell, Citation2012). Therefore, even if there is a political conflict between China and Japan, Chinese companies will not easily give up their investment in Japan.

Figure 6. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that BPR do not Granger cause FDI outflows.

Figure 7. Bootstrap estimates of the sum of the rolling window coefficients for the impact of BPR on FDI outflows.

By the bootstrap rolling window causal test, we establish that the BPR is not the Granger cause of FDI more than half of the time. While BPR brings about temporary influence in FDI, in most cases, it does not have a permanent impact. This indicates that causal relationships are complicated and depend on whether the investor has enough determination to sacrifice its interests to serve the country’s politics. First, compared with trade and short-term capital flows, FDI has a long-term characteristic. We argue that the existence of sunk costs makes it impossible for investors to withdraw investments arbitrarily (Lee Citation2008; Polachek et al., Citation2005b). Investors lack the motivation to link political relations and economic activities in an era of globalization. Hence, aggregate FDI flows are unaffected by the deterioration of political relations. Second, although BPR can influence FDI, whether foreign capital enters depends more on the location superiority of the host country, such as market size, institutional quality, human capital stock or preferential FDI policies (Ali and Guo, Citation2005; Desbordes and Vicard, Citation2009; Sun et al., Citation2002; Swain and Wang, Citation1997; Yahya, 2018; Zhang and Markusen, Citation1999; Zhang, Citation2001; ). China has abundant labor resources and low cost, which are the unique advantage of attracting foreign capital inflows. Preferential policies for foreign investment, high purchasing power and good investment environment make China the preferred destination for global investment. Unlike in China, Japan’s location advantage lies in technology. Chinese enterprises’ investment in Japan can obtain advanced technology directly, which is exactly what China lacks. Therefore, compared with these investment location advantages, the impact of BPR on FDI is negligible. Third, prospective investors consistently predict the impact of political relations on investment returns. When companies predict a high political risk, they might decrease the ex-ante investment before conflict occurs (Li, Citation2006). Newland and Govella (Citation2010) find that investors appear to have factored the possibility of occasional Sino-Japanese tensions into their investment decisions, an incident that might be a serious shock in BPR appears to be perceived as “business as usual” for Japanese investors. Finally, the political conflict between China and Japan is overall controllable, so BPR will not have much impact on FDI. On the one hand, as an ally of Japan, the U.S. will exert pressure on Japan to prevent a long-term antagonism with China, thereby guaranteeing that Sino-Japanese political conflicts remain controllable (Blanchard Citation2000). On the other hand, both governments hope to minimize political conflicts, worrying that Sino-Japanese nationalism will evolve into a large-scale destabilizing movement which might cause the disruption of bilateral economic relations (Deans Citation2000; Downs and Saunders Citation1999; Koo, Citation2009; Suzuki, Citation2007).

In addition, we have also considered the important role of bilateral investment treaties (BITs). The signing of BITs is conducive to reducing the diplomatic risks faced by foreign investors because they can prosecute the host country via international arbitration (Elkins et al., Citation2006; Neumayer and Spess, Citation2005). On 27 August 1988, China and Japan signed the “Agreement between the People’s Republic of China and Japan Concerning the Encouragement and Reciprocal Protection of Investment.”Footnote4 In the context of the unstable Sino-Japanese political relations, BITs can minimize the adverse effects on Japanese or Chinese companies. In summary, the impact of BPR on FDI should not just be thought out from the positive and negative connection. We must also consider special events or economic backgrounds in order to assess complex Sino-Japanese relations accurately.

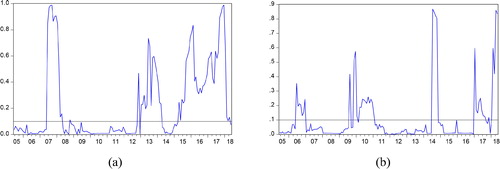

reports the rolling bootstrap p-values with the null hypothesis that the leader’s visit does not affect FDI inflows (outflows). In light of , the null hypothesis is rejected in most sub-periods, indicating that a leader’s visit can promote FDI inflows and outflows. On the one hand, high-level mutual visits can provide a series of investment contracts and agreements for home country enterprises to invest in host countries through peaceful consultations or diplomatic pressures, reducing the negotiation and transaction costs of multinational enterprises to enhance the confidence of entrepreneurs to increase investment (Zhang and Jiang, Citation2012). On the other hand, due to the instinctive principle of risk aversion, home enterprises tend to identify with and follow similar bilateral political activities, and regard high-level mutual visits as a sign of bilateral friendship. This kind of political interaction provides enterprises with relatively high property rights protection capabilities, strengthens the confidence of home-based enterprises in overseas investment, and primarily promotes the reinvestment behavior and expansion of investment scope (Yang et al., Citation2016).

Figure 8. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that leader's visit do not Granger cause FDI inflows (outflows).

reports the rolling bootstrap p-values with the null hypothesis that diplomatic conflict does not affect FDI inflows (outflows). We can see that the null hypothesis is not rejected in most sub-periods, implying that diplomatic conflicts have no significant negative effect on the expansion of FDI inflow and outflow. Due to the inconsistent interests between countries, China and Japan often have some diplomatic conflicts, such as territorial disputes, human rights issues, historical issues and so on. First of all, when the national interests of the home and host country are inconsistent and a diplomatic conflict occurs, considering the overall national interests, the host country rarely resorts to directly obtaining the property rights of investors in the home country (Blanchard Citation2000). Second, entrepreneurs will also make reasonable expectations of diplomatic relations (Li, Citation2006; Newland and Govella, Citation2010). If the expected diplomatic conflict is short-lived, they will not easily withdraw investment.

Figure 9. Bootstrap p-value of rolling test statistic testing the null that diplomatic conflict do not Granger cause FDI inflows (outflows).

At the same time, entrepreneurs will also exert pressure on the government to reduce the adverse impact of diplomatic conflicts on investment. Japanese entrepreneurs have felt that the deterioration of Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations is not conducive to the development of economic relations between the two countries (Li, Citation2006). A survey of 200 major Japanese enterprises conducted by a French bank in 2004 showed that 80% of respondents believed that diplomatic tensions are having a negative impact on Sino-Japanese economic and trade relations. Under these circumstances, Japanese entrepreneurs have exerted pressure on the Prime Minister to protect their economic interests. On August 31, 2004, the chairman of the Japan Federation of Economic Organizations, Okuda Shuo, said that there is no high-level dialogue in Sino-Japanese relations and hoped that the Prime Minister will take necessary measures to ease the diplomatic conflict. Facing the pressure of the business circles, the Prime Minister of Japan has held many meetings with Chinese leaders.

7. Conclusions

This study tests the causality between BPR and FDI to highlight whether BPR can affect FDI inflows or outflows, using the case of Sino-Japanese relations. The full-sample causality test suggests that there is no causal relationship between BPR and FDI inflows, FDI outflows do not Granger cause BPR either, but BPR do Granger cause FDI outflows. Considering that the parameters are unstable, we then adopt a time-varying rolling window estimate to reexamine the dynamic causality. Our result confirms that BPR has both positive and negative influences on FDI inflows in different sub-stages, but only negative impacts on FDI outflows. It indicates that we ought to integrate it with the actual situation of Sino-Japanese relations. Meanwhile, we have not find the impact of both FDI inflows and outflows on BPR. The finding is not aligned with the model of Polachek et al. (Citation2007) who think that the influence of FDI on BPR is stable and negative. We also divide the BPR into two dimensions: leader’s visits and diplomatic conflicts to examine the role of specific political actions. Leader’s visits can significantly increase FDI inflows and outflows, but diplomatic conflicts have less impact on FDI. Given this, we suggest that the Chinese government should increase investment by establishing closer political relations with key FDI partners (Desbordes, Citation2010). Both China and Japan need to view each other objectively and strengthen bilateral cooperation (e.g., sign cooperation documents and eliminate investment barriers) to promote the common development of the two economies. Enhancing mutual visits and dialogue among national leaders is an effective way to promote foreign investment, realize the rational allocation of global resources and the sustainable development of the Sino-Japanese economy.

There are several contributions to this study. First, this paper is a pioneering effort to probe the causal nexus between BPR and FDI based on Sino-Japanese relations. Results indicate that there is a significant one-way causal nexus from the BPR to FDI in some sub-periods. However, the role of FDI in BPR is not significant. These findings are inconsistent with the model of Polachek et al. (Citation2007), showing that the increased FDI is conducive to encouraging the government to improve BPR. In the event of a severe world economic situation, Chinese and Japanese governments should seek the common ground of economic interests in order to promote the sound development of political relations. Policymakers should also actively consider the role of political relations in promoting FDI and resolve economic disputes through political means. Second, the existing literature exclusively turns to account the full-sample causality estimation. The result may not be accurate because the time-varying property is not considered. Structural changes can make the dynamic causality of time series unstable between different sub-stages (Su et al., Citation2017; Su, Khan, et al., Citation2019). We apply the bootstrap rolling window technology to revisit the dynamic causal nexus, this method providing more plausible causal inferences about the relationship between BPR and FDI and drawing a more realistic conclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article, FDI inflows refers to Japanese enterprises' investment in China, FDI outflows refers to Chinese enterprises' investment in Japan, FDI refers to both FDI inflows and FDI outflows.

2 The Institute of International Relations of Tsinghua University has quantified the Sino-Japanese bilateral relationship since January 1950. The database has been updated to May 2018. The database can be obtained from http://www.imir.tsinghua.edu.cn/publish/iis/7522/index.html

3 To prove the result of this study is robust, we also use the window widths of 20-, 30- and 36- months to explore the causality, and the results are similar with the 24 month window.

4 For details of the treaty, refer to the Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China, Department of Treaty and Law.

References

- Ali, S., & Guo, W. (2005). Determinants of FDI in China. Journal of Global Business and Technology, 1, 21–33.

- Andrews, D. W. K. (1993). Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica, 61(4), 821–856. doi:10.2307/2951764

- Azzimonti, M. (2018). The politics of FDI expropriation. International Economic Review, 59(2), 479–510. doi:10.1111/iere.12277

- Balcilar, M., Ozdemir, Z. A., & Arslanturk, Y. (2010). Economic growth and energy consumption causal nexus viewed through a bootstrap rolling window. Energy Economics, 32(6), 1398–1410. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2010.05.015

- Balcilar, M., & Ozdemir, Z. A. (2013). The export-output growth nexus in Japan: A bootstrap rolling window approach. Empirical Economics, 44(2), 639–660. doi:10.1007/s00181-012-0562-8

- Barry, C. M. (2018). Peace and conflict at different stages of the FDI lifecycle. Review of International Political Economy, 25(2), 270–292. doi:10.1080/09692290.2018.1434083

- Bellak, C., Leibrecht, M., & Romisch, R. (2007). On the appropriate measure of tax burden on Foreign Direct Investment to the CEECs. Applied Economics Letters, 14(8), 603–606. doi:10.1080/13504850500474202

- Blanchard, J. M. F. (2000). The U.S. role in the Sino-Japanese dispute over the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands 1945-1971. The China Quarterly, 161, 95–123. doi:10.1017/S0305741000003957

- Blanton, R. G., & Apodaca, C. (2007). Economic globalization and violent civil conflict: Is openness a pathway to peace? The Social Science Journal, 44(4), 599–619. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2007.10.001

- Brewer, T. L. (1993). Government policies, market imperfections, and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(1), 101–120. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490227

- Bussmann, M. (2010). Foreign direct investment and militarized international conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 47(2), 143–153. doi:10.1177/0022343309354143

- Bussmann, M., & Schneider, G. (2007). When globalization discontent turns violent: Foreign economic liberalization and internal war. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 79–97. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00440.x

- Chunhachinda, P., Dandapani, K., Hamid, S., & Prakash, A. J. (1997). Portfolio selection and skewness: Evidence from international stock markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(2), 143–167. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(96)00032-5

- Chan, S., & Mason, M. (1992). Foreign direct investment and host country conditions: Looking from the other side now. International Interactions, 17(3), 215–232. doi:10.1080/03050629208434780

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Maloney, M. M., & Manrakhan, S. (2007). Causes of the difficulties in internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5), 709–725. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400295

- Dai, L. Y., & Li, Z. (2018). Bilateral political relationship, institutional quality, and China’s OFDI. Economic Theory and Business Management, 11, 94–109.

- Davis, C. L., & Meunier, S. (2011). Business as usual? Economic responses to political tensions. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 628–646. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x

- Deans, P. (2000). Contending nationalisms and the Diaoyutai/Senkaku dispute. Security Dialogue, 31(1), 119–131. doi:10.1177/0967010600031001010

- Demooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2003). Taxation and foreign direct investment: A synthesis of empirical research. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 673–693.

- Desbordes, R., & Vicard, V. (2009). Foreign direct investment and bilateral investment treaties: An international political perspective. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(3), 372–386. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2009.05.001

- Desbordes, R. (2010). Global and diplomatic political risks and foreign direct investment. Economics & Politics, 22(1), 92–125. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.2009.00353.x

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366a), 427–431. doi:10.1080/01621459.1979.10482531

- Downs, E. S., & Saunders, P. C. (1999). Legitimacy and the limits of nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands. International Security, 23(3), 114–146. doi:10.1162/isec.23.3.114

- Elkins, Z., Guzman, A., & Simmons, B. (2006). Competing for capital: The diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960-2000. International Organization, 60(04), 811–846. doi:10.1017/S0020818306060279

- Fisman, R., Hamao, Y., & Wang, Y. (2014). Nationalism and economic exchange: Evidence from shocks to Sino-Japanese relations. Review of Financial Studies, 27(9), 2626–2660. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhu017

- Gao, G. Y., Wang, D. T., & Che, Y. (2018). Impact of historical conflict on FDI location and performance: Japanese investment in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(8), 1060–1080. doi:10.1057/s41267-016-0048-6

- Gardner, L. A. (1969). On detecting changes in the mean of normal variables. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 40(1), 116–126. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177697808

- Garland, M., & Biglaiser, G. (2009). Do electoral rules matter? Political institutions and foreign direct investment in Latin America. Comparative Political Studies, 42(2), 224–251. doi:10.1177/0010414008325434

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2009). Cultural biases in economic exchange? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1095–1131. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1095

- Hajzler, C. (2014). Resource-based FDI and expropriation in developing economies. Journal of International Economics, 92(1), 124–146. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.10.004

- Hansen, B. E. (2002). Tests for parameter instability in regressions with I(1) processes. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 20, 45–59.

- Hartman, D. G. (1984). Tax policy and foreign direct investment in the United States. National Tax Journal, 37, 475–488. .

- He, Y. (2007). History, Chinese nationalism and the emerging Sino-Japanese conflict. Journal of Contemporary China, 16(50), 1–24. doi:10.1080/10670560601026710

- Jensen, N. M. (2006). Nation-states and the multinational corporation: A political economy of foreign direct investment. Princeton University Press.

- Julio, B., & Yook, Y. (2016). Policy uncertainty, irreversibility, and cross-border flows of capital. Journal of International Economics, 103, 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.08.004

- Kim, D. (2016). The effects of inter-state conflicts on foreign investment flows to the developing world: Enduring vs ephemeral risk of conflicts. International Political Science Review, 37(4), 422–416. doi:10.1177/0192512115582278

- Kluge, J. N. (2017). Foreign direct investment, political risk and the limited access order. New Political Economy, 22(1), 109–127. doi:10.1080/13563467.2016.1201802

- Knill, A., Lee, B. S., & Mauck, N. (2012). Bilateral political relations and sovereign wealth fund investment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(1), 108–123. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.11.002

- Koo, M. G. (2009). The Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute and Sino-Japanese political economic relations: cold politics and hot economics? The Pacific Review, 22(2), 205–232. doi:10.1080/09512740902815342

- Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P. C., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationary against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? Journal of Econometrics, 54(1-3), 159–178. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(92)90104-Y

- Lee, H. (2008). Political disputes and investment: The effect of militarized interstate disputes on foreign direct investment. The University of Iowa, Iowa City.

- Lee, H., & Mitchell, S. M. L. (2012). Foreign direct investment and territorial disputes. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(4), 675–703. doi:10.1177/0022002712438348

- Li, Q. (2006). Democracy, autocracy, and tax incentives to foreign investors: A cross-national analysis. The Journal of Politics, 68(1), 62–74. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00370.x

- Li, Q. (2008). Foreign direct investment and interstate military conflict. Journal of International Affairs, 62, 53–66.

- Li, Q., & Liang, G. (2012). Political relations and Chinese outbound direct investment: Evidence from firm-and dyadic-level tests. [Research Center for Chinese Politics and Business Working Paper No. 19.]. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University.

- Li, Q., & Vashchilko, T. (2010). Dyadic military conflict, security alliances, and bilateral FDI flows. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5), 765–782. doi:10.1057/jibs.2009.91

- Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (1999). Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. European Economic Review, 43(2), 335–356. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00048-8

- Mihalache-O'keef, A., & Vashchilko, T. (2010). Foreign direct investors in conflict zones. Adelphi Series, 50(412-413), 137–156. doi:10.1080/19445571.2010.515153

- Neumayer, E., & Spess, L. (2005). Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? World Development, 33(10), 1567–1585. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.001

- Newland, S., & Govella, K. (2010). Hot economics, cold politics? Re-examining Economic Linkages and Political Tensions in Sino-Japanese Relations [Paper presentation]. Social Science Research Network, APSA Annual Meeting Paper.,

- Nigh, D. (1985). The effect of political events on United States Direct foreign investment: A pooled time-series cross-sectional analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 16(1), 1–17. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490439

- Nyblom, J. (1989). Testing for the constancy of parameters over time. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(405), 223–230. doi:10.1080/01621459.1989.10478759

- Osabutey, E. L., & Okoro, C. (2015). Political risk and foreign direct investment in Africa: The case of the Nigerian telecommunications industry. Thunderbird International Business Review, 57(6), 417–429. doi:10.1002/tie.21672

- Pesaran, M. H., & Timmermann, A. (2005). Small sample properties of forecasts from autoregressive models under structural breaks. Journal of Econometrics, 129(1-2), 183–217. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.09.007

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Hansen, B. E. (1990). Statistical inference in instrumental variables regression with I (1) processes. The Review of Economic Studies, 57(1), 99–125. doi:10.2307/2297545

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. doi:10.1093/biomet/75.2.335

- Polachek, S., Seiglie, C., & Xiang, J. (2005a). Globalization and international conflict: Can FDI increase peace? Working Paper Rutgers University, 1–35.

- Polachek, S., Seiglie, C., & Xiang, J. (2005b). Globalization and international conflict: Can FDI increase peace as Trade Does? American Economic Association.

- Polachek, S., Seiglie, C., & Xiang, J. (2007). The impact of foreign direct investment on international conflict. Defence and Peace Economics, 18(5), 415–429. doi:10.1080/10242690701455474

- Shahzad, S. J. H., Zakaria, M., Rehman, M. U., Ahmed, T., & Fida, B. A. (2016). Relationship between FDI, terrorism and economic growth in Pakistan: Pre and post 9/11 analysis. Social Indicators Research, 127(1), 179–194. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0950-5

- Sorens, J., & Ruger, W. (2014). Globalisation and intrastate conflict: An empirical analysis. Civil Wars, 16(4), 381–401. doi:10.1080/13698249.2014.980529

- Souva, M., & Prins, B. (2006). The liberal peace revisited: The role of democracy, dependence, and development in militarized interstate dispute initiation, 1950-1999. International Interactions, 32(2), 183–200. doi:10.1080/03050620600719361

- Su, C. W., Khan, K., Tao, R., & Nicoleta-Claudia, M. (2019). Does geopolitical risk strengthen or depress oil prices and financial liquidity? Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Energy, 187, 116003. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116003

- Su, C. W., Wang, X. Q., Tao, R., & Oana-Ramona, L. (2019). Do oil prices drive agricultural commodity prices? Further evidence in a global bio-energy context. Energy, 172, 691–701. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.02.028

- Su, C. W., Li, Z. Z., Chang, H. L., & Oana-Ramona, L. (2017). When Will Occur the Crude Oil Bubbles?. Energy Policy, 102, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.12.006

- Su, C.-W., Qin, M., Tao, R., Moldovan, N.-C., & Lobonţ, O.-R. (2020). Factors driving oil price dd from the perspective of United States. Energy, 197, 117219–117210.

- Sun, C., & Liu, Y. (2019). Can China’s diplomatic partnership strategy benefit outward foreign direct investment? China & World Economy, 27(5), 108–134. doi:10.1111/cwe.12289

- Sun, Q., Tong, W., & Yu, Q. (2002). Determinants of foreign direct investment across China. Journal of International Money and Finance, 21(1), 79–113. doi:10.1016/S0261-5606(01)00032-8

- Suzuki, S. (2007). The importance of ‘Othering’ in China’s national identity: Sino-Japanese relations as a stage of identity conflicts. The Pacific Review, 20(1), 23–47. doi:10.1080/09512740601133195

- Swain, N. J., & Wang, Z. (1997). Determinants of inflow of foreign direct investment in Hungary and China: Time-series approach. Journal of International Development, 9(5), 695–726. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(199707)9:5<695::AID-JID294>3.0.CO;2-N

- Yahya, A. (2016). Location determinants of foreign direct investment in Indonesia. Proceeding of International Conference on Economics and Business, 4, 322–345.

- Yahya, A. (2018). Foreign direct investment inflow into aceh province of Indonesia after peace agreement. Proceedings of MICoMS, 2017(1), 429–435.

- Yang, L. X., Liu, X. G., & Zhang, J. (2016). How do bilateral political relations affect outward direct investment—Based on a perspective of binary margins and investment failure. China Industrial Economics, 11, 56–72.

- Zhang, F. (2012). The Tsinghua approach and the inception of Chinese theories of international relations. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 5(1), 73–102. doi:10.1093/cjip/por015

- Zhang, K. H., & Markusen, J. (1999). Vertical multinationals and host-country characteristics. Journal of Development Economics, 59(2), 233–252. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(99)00011-5

- Zhang, K. H. (2001). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth in China? The Economics of Transition, 9(3), 679–693. doi:10.1111/1468-0351.00095

- Zhang, J. H. (2005). An explanatory study of bilateral FDI relations: The case of China. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 3(2), 133–150. doi:10.1080/14765280500120054

- Zhang, J. H., & Jiang, J. G. (2012). The impact of bilateral political relationship on China’s outward foreign direct investment. World Economics and Politics, 12, 133–155.